Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 22

June 30, 2019

Whitman and Music: A Fresh Discovery

It’s said that Walt Whitman has been set to music more than any other poet save Shakespeare.

Oddly, the most memorable of these settings may be by an Englishman: Frederic Delius’s Sea Drift (1904) and Songs of Farewell (1930). There are also notably affecting Whitman settings by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Kurt Weill.

What about settings by American-born composers? An unlikely candidate may be the best of the bunch. It’s a 1944 radio play, just revived by PostClassical Ensemble at the Washington National Cathedral. You can hear it here: https://www.wwfm.org/post/postclassical-presents-music-bernard-herrmann

The makers of this 30-minute Walt Whitman were the titans of the genre: Norman Corwin and Bernard Herrmann. Beginning in 1939, they collaborated on original radio dramas 21 times. Corwin scripted and directed; Herrmann composed the music. Corwin’s distinctive free-verse style derived from Whitman (and also, he testified, Carl Sandburg and Thomas Wolfe — lesser writers). Herrmann’s radio work at CBS was the fundament for his unforgettable film scores, the first of which – Citizen Kane (1941) – was composed for Orson Welles, himself a radio-drama legend.

Amazingly, Corwin, Herrmann, and Welles were all in their twenties when they first made their mark on live radio. By the time Corwin and Herrmann converged on Whitman, American radio drama peaked as an eloquent mass-strategy to rally the home front. And so Walt Whitman was invoked as a champion of American democracy in time of war.

Herrmann was a composer whose versatility is still not acknowledged. His film scores, his radio scores, his cantata Moby Dick, his big 1941 symphony, his opera Wuthering Heights all speak the same moody Romantic language. And Herrmann at 33, composing Whitman, already sounds like the composer of Vertigo (1958). The most hypnotically Romantic passage, magically scored for strings, harp, and celesta, supports Whitman’s sublime imagery of grass:

I guess

the grass is the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

Tenderly

will I use you, curling grass.

It may

be you transpire from the breasts of young men.

You can hear it by scrolling to 31:35 of Part Two here: https://www.wwfm.org/post/postclassical-presents-music-bernard-herrmann

Re-encountering this 30-minute radio poem today (our performance was the professional concert premiere), I marvel at the listening habits of Americans 75 years ago. But then, Americans once listened raptly to the high-pitched (and frequently obscure) rhetoric of Ralph Waldo Emerson. As listeners, as readers and speakers, our stamina has sharply diminished in the age of social media.

The film-historian Neil

Lerner, one of the commentators at the National Cathedral performance, pointed

out that Corwin’s script actually acknowledges the challenge of sharing

aspirational poetry with a mass audience. He interpolates a “Voice” whose

interruptions include:

“I don’t follow you. You’re

over my head. Anyway, why don’t you calm down? There’s nothin’ to get excited

about. Take it easy.”

Corwin here segues seamlessly

to Whitman:

Did you

ask dulcet rhymes from me?

Did you

seek the civilian’s peaceful and languishing rhymes?

Did you

find what I sang so hard to follow?

Why I

was not singing for you to follow, to understand – nor am I now;

What to

such as you anyhow such a poet as I? therefore leave my works,

And go

lull yourself with what you can understand, and with piano-tunes,

For I

lull nobody, and you will never understand me.

At the National Cathedral

performance, William Sharp’s delivery of Whitman’s words gripped and held.

The program – a June 1 Bernard Herrmann tribute coinciding with the Whitman Bicentennial – also included music from Psycho and Herrmann’s 1967 clarinet quintet Souvenirs de voyage. The Psycho music – a terrific performance led by Angel Gil-Ordonez — wasn’t the usual suite of film excerpts, but a persuasive “narrative” for string orchestra created by the composer himself. The quintet – which I have several times extolled in this space – seems to me the most beautiful chamber music by any American. Our principal clarinetist, David Jones, is an inspired advocate.

The Cathedral concert continued PostClassical Ensemble’s advocacy of Bernard Herrmann as “the most under-rated twentieth century American composer” – a claim we pursued for weeks during a 2016 Herrmann festival.

A forthcoming PCE Herrmann

recording, on Naxos, will feature the world premiere recording of Whitman, along with the Psycho narrative and clarinet quintet.

Herrmann deserves to be as well-known to American concert audiences as Copland

or Gershwin.

The WWFM Network live broadcast of our June 1 concert is now on the web: https://www.wwfm.org/post/postclassic...

It begins with the Psycho narrative, followed by:

–Dorothy Herrmann describing her crusty father (Part One: 29:59)

–The clarinet quintet (Part One: 31:15)

–An intermission feature including the Whitman scholar Steven Herrmann and Murray Horwitz of WAMU’s The Big Broadcast (Part Two: 00:00)

—Whitman (Part Two: 17:35)

April 30, 2019

Why “Porgy and Bess” Is More than a “Period Piece”

However popular it may be, Porgy and Bess remains an object of rampant controversy and confusion.

An odd item in the New York Times the other day reported that the white cast of the Hungarian State Opera’s Porgy and Bess (above) had been instructed to declare themselves “African-Americans.” “The singers were asked to sign a declaration stating that ‘African-American origins and spirit form an inseparable part’ of their identity.” Commenting on the Gershwin Estate’s insistence that Porgy and Bess be cast with black singers, Szilveszter Okovacs, the State Opera’s general director, said he was opposed to allowing “the presence of people in a production to be determined by skin color or ethnicity.”

That seems like the makings of a reasonable or at least interesting sentiment — the Gershwin Estate’s restriction on casting is increasingly anachronistic. And yet the Budapest production itself, which situates Gershwin’s opera in a refugee camp, is probably nuts.

Meanwhile, a review in The Guardian of the new English National Opera Porgy and Bess – a traditional staging that opens the Met’s new season next September – opines that it’s a “period piece”: a snapshot of another time and place, stuck one hundred years in the past when race relations were vastly different than today.

Is the fundamental topic of Porgy and Bess a black Carolina subculture ca. 1920? If so, does that validate the Gershwin Estate’s insistence that only blacks sing it?

Having written a book about the genesis of Porgy and Bess, I would say: certainly not. The basis of Gershwin’s opera is a 1925 novella by a Southern regionalist: DuBose Heyward’s Porgy. That is a book about a black Carolina subculture – the Lowcountry Gullahs — ca. 1920. But if Porgy and Bess retains the story of Porgy, Gershwin’s Porgy is not Porgy’s Porgy (not even close) – and neither is his fate remotely that of Porgy in the novel.

Conrad L. Osborne, in his indispensable mega-book Opera as Opera, extrapolates a “meta-narrative” governing virtually all nineteenth century grand opera plots. An outcast male protagonist falls obsessively in love with a forbidden woman who returns his love; the fated couple encounters inflamed opposition; it all ends badly for the lovers. And this, truly, is the story of Carmen, of La traviata, of Tristan, of you-name-it. Osborne cites only two post-Beethoven exceptions: the original version of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, in which there is no love story, and Wagner’s Parsifal, in which Parsifal spurns Kundry’s advances and proceeds to redeem himself and everyone else.

Porgy and Bess, in Osborne’s account, hews to the basic nineteenth-century template: an outcast male, a forbidden woman, a doomed love relationship. But that’s at most one-half of what Porgy and Bess is about. That Gershwin’s opera is in fact an exception to the ingenious Osborne taxonomy is a useful starting point in figuring out whether it’s a black “period piece” or not.

The essential observation here is that Porgy and Bess tells two overlapping stories. The first is doomed love, a la Carmen (which it resembles in all sorts of ways). The second is a saga of redemption, a la Parsifal. The first story comes from DuBose Heyward, who ends his novel with Porgy, by Bess abandoned, sinking into a fog of oblivion. The second story comes not from Heyward, not from George or Ira Gershwin, but from Rouben Mamoulian, who staged both the 1927 play Porgy and the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess. Mamoulian (drawing inspiration from Yevgeny Vakhtangov, with whom he studied in Moscow) had fixed ideas about stage dramas, including a basic story template: not doomed love, but the miracle play. He therefore changed Heyward’s ending to Porgy Redeemed. And in order to do that, he invented a different Porgy.

What Heyward made of

all this may be gleaned from his advice to Gershwin when it came time to stage

the opera: don’t hire Mamoulian. What Gershwin thought may be gleaned from his

insistence that Mamoulian direct.

And so in the opera

Porgy is not the sorry outcast Heyward had crafted. Rather, he is popular,

respected, even esteemed. In scene one, he is greeted with an outburst of affection.

A cripple, he has never had a woman. He then proceeds to fall in love and is

loved in return. When his love is threatened by a source of evil, feared by

all, he single-handedly murders Crown. At the opera’s close, he declares

himself on his way “to a Heav’nly Lan’” – an ecstatic song (originating with

Mamoulian in the 1927 play, with a tune different from Gershwin’s) in which

everyone joins. As in Parsifal, this

culminating tableau of redemption is both personal and communal. Porgy, moral

compass of Catfish Row, is a cripple made whole.

Heyward’s ending to Porgy is intended to seem real. When the Theatre Guild advertised Porgy the play as an “authentic” representation of Gullah life, Mamoulian was apoplectic. He disavowed verisimilitude. His ending, including Porgy’s resolve to drive his goat-cart from South Carolina to Manhattan, is archetypal, metaphoric, symbolic – anything but a real-life event.

The two endings of Porgy and Bess arrive almost on top of

one another. First we have Porgy discovering that Bess is gone. He sings a

magnificent lament: “Oh Bess, oh where’s my Bess? Won’t somebody tell me

where?” Then he picks himself up and sings an equally magnificent paean of

self-actualization: “Oh Lawd, I’m on my way.” How did Mamoulian and Gershwin

weight these two endings? Mamoulian trimmed “Oh Bess” by half – a courtesy to

Todd Duncan, who had to sing Porgy six times a week, but also a signal that the

more important finish was yet to come. Gershwin’s score features a pregnant E

minor “Porgy” theme: the primal interval of a fifth girds a minor third (G

natural) crippled by a mashed grace note. Only in the final measure of the

opera – the culmination of “On my way” — does he raise the G natural of

Porgy’s theme to G-sharp and secure an E major close. Porgy’s saga of doomed

love is transcended by Porgy’s life-odyssey. Gershwin’s redoubles this message

by having his orchestra, a la Wagner, recall key stages in Porgy’s story – “I

got plenty o’ nuttin’,” “What you want with Bess?” “Bess you is my woman” —

underneath the singing.

There is a linchpin in this double ending. It is the opera’s most famous line, a line called by Stephen Sondheim “one of the most moving moments in musical theater history”: “Bring my goat!” Mamoulian directs that Porgy issue this command twice: first as a directive — “Mingo, Jim, bring my goat!” — and then ”commandingly”: “No! I’m going! Bring my goat!” He is initially disbelieved, but his exalted resolve to pick himself up proves irresistible. The goat is brought. The uplift begins.

The author of the words “Bring my goat!” was Rouben Mamoulian – in the working typescript for Porgy the play, you can see him delete Heyward’s “Porgy turns his goat and drives slowly with bowed head toward the gate” and hand-write something wholly different. In Porgy and Bess, Mamoulian’s 1927 rewrite of the story’s ending is retained almost verbatim.

And that is why staging Porgy and Bess without a goat-cart for Porgy – now common practice — becomes a problem. Doubtless there are multiple reasons to do without a goat onstage. And yet: the Porgy of Heyward, Mamoulian, and Gershwin cannot at all use his legs; he walks on his knees. If Porgy is merely a cripple on crutches, his infirmity is diminished, and so therefore is his victory. And what to do with “Bring my goat!”?

As it happens, I’m teaching a graduate seminar at SUNY Purchase this Spring with an inquisitive group of music students, and we’re studying Porgy and Bess. In class over the past several weeks, we’ve sampled two DVDs – a San Francisco Opera production, and the rather famous Trevor Nunn Glyndebourne production conducted by Simon Rattle. Neither uses a goat. In the San Francisco Porgy and Bess, Eric Owen (who will be the Met’s goat-less Porgy this Fall) exclaims “Bring my crutch!” But a crutch is the last thing Porgy would ask for in the throes of his redemptive ecstasy. And Owen’s anguished delivery is also wrong. The ending fails because it contradicts the sense of the opera’s words and music.

Nunn’s solution is better:

Willard White exclaims: “I’ve got to go!” And Nunn understands redemption. His

Porgy discards his crutches, and to

the stupefaction of all proceeds to stagger on his own two feet into a glare of

sunshine. That is not the ending to a period piece.

April 9, 2019

Music from Paradise

Claude Debussy wrote:

“But my poor friend! Do you remember the Javanese music, able to express every shade of meaning, even unmentionable shades which make our tonic and dominant seem like ghosts? . . . Their school consists of the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind in the leaves, and a thousand other tiny noises . . . that force one to admit that our own music is not much more than a barbarous kind of noise more fit for a traveling circus.”

Debussy heard a Javanese gamelan at the Paris Exposition of 1889 – an epiphany.

Another such encounter was Olivier Messiaen’s first exposure to a Balinese gamelan – in Paris in 1931.

It is remarkably little known that the non-Western genre that has most influenced Western composers is not African or Chinese or Indian – it’s Indonesian. Or that this is actually a double influence: separated by a strait of water less than 400 miles side, Java and Bali fostered remarkably different gamelan genres — the first mellow, the second brazen and metallic.

The most recent “PostClassical” podcast on WWFM explores these differences in the context of religious belief and Dutch colonial history, as expounded by the gamelan scholar Bill Alves.

Hosted by the inimitable Bill McGlaughlin, our podcast also includes musical highlights from PostClassical Ensemble’s three-hour “Cultural Fusion” concert at the Washington National Cathedral last January. The centerpiece of both the concert and the podcast is a terrific performance of the pre-eminent American concerto – Lou Harrison Piano Concerto of 1985.

You can hear it all here.

LISTENING GUIDE:

PART ONE:

00:00 – Javanese gamelan; Debussy: “Pagodas” (Wan-Chi Su)

12:02 – Bill Alves on the Hindu roots of Balinese gamelan

14:05 – Balinese gamelan

18:50 – Introducing Colin McPhee

21:07 – McPhee: Two Ceremonial Dances (Benjamin Pasternack and Wan-Chi Su)

33:42 – McPhee: Nocturne for chamber orchestra (Dennis Russell Davis conducts Brooklyn Philharmonic)

44:53 – Messiaen: “Visions de L’amen,” movement one (Benjamin Pasternack and Wan-Chi Su)

52:22 – Alves: “Black Toccata” (Benjamin Pasternack and Wan-Chi Su)

PART TWO:

11:37 – Bill Alves demonstrates how the layered textures of gamelan embody a “cosmic hierarchy in sound”

00:00 – “Stampede” from Lou Harrison’s Piano Concerto (excerpt – Pasternack and PCE)

17:41 – Harrison Piano Concerto, movement one (Pasternack and PCE conducted by Gil-Ordonez)

33:28 – Harrison Piano Concerto, movement two (Pasternack/PCE)

45:04 – Harrison Piano Concerto, movements three and four (Pasternack/PCE)

1:00:24 – Harrison Suite (excerpts—Wan-Chi Su, Netanel Draiblate/PCE/Gil-Ordonez)

1:07:14 – Statement by Indonesian Ambassador Budi Bowoleksono

April 3, 2019

Mark Twain, Charles Ives, and Race

In the current issue the quarterly review Raritan, I write that Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Charles Ives’s Symphony No. 2 “are twin

American cultural landmarks, comparable in method and achievement.” They both transform a hallowed Old World genre

– the novel, the symphony — through recourse to New World vernacular speech.

To read the whole piece, click here.

It bears mentioning that Ives and Mark Twain knew one

another via the Reverend Joseph Twitchell. Twitchell was for forty years Samuel

Clemens’s closest friend. His daughter Harmony married Charlie Ives in 1908.

Crucially, both Twain’s novel and Ives’s symphony deal with the inescapable American self-affliction: slavery. At the heart of Huck’s story is his moral epiphany on the raft with Jim: Huck’s precocious early manhood is confirmed by a dawning realization that laws of the heart trump human laws such as those dictating that black men may be enslaved, and that slaves who escape be returned to their “masters.”

As for Ives: we know from a 1943 letter to the conductor Artur

Rodzinski that he linked his symphony with the “fret and storm and stress of liberty”

of the Civil War. Its movement two sonata form adapts for its main theme an

Abolitionist song: “Wake Nicodemus.” Where the marches and dances of the finale

abate for a plaintive horn tune citing Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe,” Ives (as

he told Rodzinski) finds inspiration in Foster’s “sadness for the slaves.” The

passage in question is the symphony’s lyric pinnacle.

Like Mark Twain’s America, Ives’s America embraced the tragedy and turmoil of slavery and race.

March 5, 2019

Did Wagner Exploit King Ludwig?

Did Wagner exploit King Ludwig?

In Luchino Visconti’s magnificent four-hour film Ludwig, the king is ingeniously cast as an

embodiment of the Wagnerian pariah; Visconti has transformed Ludwig’s story

into a veritable homage to Richard Wagner.

Is Visconti’s Ludwig a credible re-enactment of history? Doubtless it could be considered a whitewash job. But not be me. Wagner remains an object of excessive condemnation and mistrust — witness Simon Callow’s recent cheap shot, Being Wagner. In writing about Visconti’s mega bio-pic for the current Wagner Journal, I felt the need to narrate my own version of events.

I contend:

“As his letters confirm, Ludwig was eccentric, but certainly

no simpleton. His instantaneous agenda was to rescue Wagner materially, and to

collaborate with Wagner in the project of redeeming German culture. These

aspirations were no more deranged than was Ludwig himself. . . . Ultimately,

the king and his composer served one another royally. Every other factor bearing

on their friendship of two decades shrinks to insignificance.”

My article, “Ludwig Revisited,” greatly expands a capsule review

I wrote for The Wall Street Journal last year. The Wagner Journal itself, edited by Barry Millington, remains a

remarkable platform for spirited and informed discussion and debate. It’s also

beautifully produced. Would that we had a few more English-language classical-music

publications of such caliber.

Here’s what I wrote, adorned with a sampling of Visconti’s breathtaking mise-en-scene:

Ludwig revisitedDownload

February 24, 2019

Dvorak, Harry Burleigh, and Cultural Appropriation — a “PostClassical” Podcast

Could Harry Burleigh — Antonin Dvorak’s African-American assistant — be considered an Uncle Tom?

These days, the question comes up whenever

Burleigh comes up: it’s a symptom of the times, and of our crazy obsession with

“cultural appropriation.”

And it is addressed head-on over the course of the most recent PostClassical Ensemble WWFM podcast, featuring a supreme exponent of the spiritual in concert: the African-American bass baritone Kevin Deas. (To see what he and others have to say, hang on for a dozen paragraphs — or simply access the podcast at https://www.wwfm.org/post/postclassical-feb-15-deep-river)

I would call Harry Burleigh (1866-1949) a

forgotten hero of American music. It was mainly Burleigh who turned spirituals

into concert songs to be sung alongside the Lieder of Schubert and Brahms. The

project became controversial during the Harlem Renaissance – Carl Van Vechten,

Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston were among those who worried or

asserted that Burleigh vitiated the music he adapted. And today Burleigh is

controversial all over again.

Because I have long celebrated Burleigh in public performance, because I often have occasion to lecture on American music, I can cite many examples from personal experience. There was, for instance, the impressively poised African-American freshman at a Midwestern college who opined that “just because Burleigh was black, he didn’t necessarily have the right to do that.” As she had never heard of Marian Anderson, I played for the class a recording of Anderson singing Burleigh’s iconic “Deep River” arrangement. After that, I shared with them Anderson’s historic Lincoln Memorial concert of 1939, when – having been denied access to Constitution Hall because of the color of her skin — she sang Burleigh for more than 75,000 listeners.

It must be acknowledged and pondered that

Burleigh frequently inhabited a white milieu. His arrangements were initially

sung by famous white recitalists – because in 1917 famous vocal recitalists

were white. He himself sang in synagogue and church choirs that were mainly

white. His friends included J. P. Morgan, at whose funeral he sang.

By way of background: Not so very long after

Dvorak and W.E.B. Du Bois extolled the sorrow songs as the likely fundament for

a future American music, artists and

intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance scoured the African-American musical

past. One starting point was the cottonfield. One outcome was a now legendary

debate over the uses of a past known and acknowledged, wracked with pain and

yet protean with possibility.

It is little remembered that, like Dvorak, Du

Bois was a Wagnerite. As a graduate student in Berlin, he came to know and

embrace The Ring of the Nibelung. In the tradition of Wagner, Herder, and other

German theorists of race, he linked collective purpose and moral instruction to

“folk” wisdom: the soul of a people. To

Du Bois it was merely obvious that for black Americans the sorrow songs comprised

a usable past that, subjected to evolutionary development, would yield a

desired native concert idiom — the same trajectory anticipated by Dvorak and

Burleigh. Formal training and performance, for Du Bois, did not impugn the

authenticity of folk sources; rather, a dialectical reconciliation of authority

and cosmopolitan finesse would result. Concomitantly, ragtime, the blues, and

jazz threatened Du Bois’s cultural/political agenda. A child of the Gilded Age,

born in tolerant Massachusetts in 1868, he endorsed uplift.

Alain Locke, sole offspring of a well-to-do

Philadelphia family in 1885, was like Du Bois a distinguished black Harvard

graduate. His philosophy of the New Negro, a signature of the Harlem

Renaissance, aligned with Du Bois’s high-cultural predilections. “Negro

spirituals,” Locke wrote in 1925, could undergo “intimate and original

development in directions already the line of advance in modernistic music. . .

. Negro folk song is not midway in its artistic career yet, and while the preservation

of the original folk forms is for the moment the most pressing necessity, an

inevitable art development awaits them, as in the past it has awaited all other

great folk music.” Like Du Bois, Locke championed the tenor Roland Hayes, who

succeeded Burleigh as the pre-eminent exponent of the spiritual in concert.

Like Du Bois, he mistrusted the popular musical marketplace in favor of elite

realms of art.

The opposing camp included Harlem’s loudest

white cheerleader: Carl Van Vechten, who deplored Hayes’ refinements in favor

of Paul Robeson’s “traditional, evangelical renderings” of the Burleigh

arrangements. This – and Van Vechten’s celebration of the blues and jazz –

ignited a furious rebuttal from Du Bois, who discerned a decadent voyeur in

love with black exoticism. But Van Vechten’s revisionism was supported by the

black writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Many of Hughes’s poems

key on the dialect and structure of the blues. He heard in jazz “the eternal

tom-tom beating of the Negro soul.” He deplored the “race toward whiteness” in

the uses of black music. Hurston deplored a “flight from blackness.” She heard

concert spirituals “squeezing all of the rich black juice out of the songs,” a

“sort of musical octoroon.” If to Hurston the sorrowful spirituals Du Bois

espoused sounded submissive, to Locke the blues sounded “dominated” by

“self-pity.” Pitting authenticity against assimilation, the debate identified

conflicting vernacular resources, old and new, rural and urban.

If certain black Americans rejected American

classical music, American classical music rejected them. Even though Hayes and Robeson

enjoyed phenomenal success in recital, opera companies and orchestras resisted

singers and instrumentalists of color. Notoriously, Marian Anderson had to wait

until 1955 to sing at the Metropolitan Opera – an invitation engineered not by

native-born Americans, but by the immigrants Sol Hurok, Rudolf Bing, Max

Rudolf, and Dmitri Mitropoulos.

All of which came up in the course of our two-hour “PostClassical” podcast: “Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual,” celebrating Burleigh and his legacy. Here is what Kevin Deas sounds like singing Burleigh’s fervently inspired transformation of “Steal Away,” a performance at the Washington National Cathedral that I was privileged to accompany at the piano:

“Steal Away” (arr. Burleigh) sung by Kevin Deas (Horowitz, piano)

And here, from the same podcast, is what Kevin

Deas had to say about cultural appropriation:

“I am from a different generation. I grew up in

the sixties and the seventies when the message was ‘everyone can do

everything.’ I felt I was blessed because my dad was in the military – so I

grew up in a melting pot. I grew up among people of all ethnicities. It never

occurred to me that as a black person and a budding artist I needed to take a

specific direction. I wanted to see what my instrument was inclined to do and

to follow that. And my sound wasn’t really right for gospel. I was drawn to

classical music. To think that I was ‘appropriating’ German Lieder as an

African-American would never have occurred to me. No disrespect to other

genres, but that’s where my voice took me. I never questioned the authenticity

of my expression. And I was very happy to come back to the spiritual relatively

late in my career and have a new and different approach. My only expectation

was to improve my art, and to evolve with it.”

In the ensuing conversation – you can listen to

it – I cited the disapproving views of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston.

Reacting to that, Kevin said: “I couldn’t disagree more.” To which Bill

McGlaughlin, who inimitably hosts “PostClassical,” added: “Neither Langston

Hughes nor Zora Heale Hurston were musicians. When real musicians get ahold of [music

they embrace], they’re going to go where they’re going to go – no matter what

the philosophies are. Your gonna follow what’s in your ear and in your heart.”

Following this exchange, we listened to Harry Burleigh sing his own arrangement of “Go Down Moses” (a 1919 recording), followed by “Go Down Moses” as arranged in 1941 by Sir Michael Tippett – i.e., a white British composer. Bill likened Tippett’s stirring appropriation to “Picasso looking at a work of Velazquez and making it into a brand new piece.” Angel Gil-Ordonez called it “a beautiful appropriation of extraordinary material.” And I remarked that Tippett’s “Go Down, Moses” precisely fulfills Alain Locke’s aspiration that African-American spirituals undergo “original development” in “the line of advance in modernistic music.” You can hear it all here:

Burleigh sings “Go Down, Moses” (1919); Sir Michael Tippett’s choral arrangement of “Go Down, Moses” (Deas, Gil-Ordonez, Cathedral Choir)

Our podcast, featuring live PostClassical

Ensemble performances with Angel Gil-Ordonez and the Washington National

Cathedral Chorus, also includes music by Nathaniel Dett, William Dawson, and –

to close – Johann Sebastian Bach: “Ich habe genug,” unforgettably sung by Kevin

Deas.

The podcast mainly samples PostClassical Ensemble’s

multi-media production, “Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual” (with a visual

track by Peter Bogdanoff), as performed at the Washington National Cathedral.

The same production, in various iterations, has been mounted on three other

occasions. It travels to Virginia Tech next month as part of a Deas/Horowitz/Gil-Ordonez

residency in which “cultural appropriation” will be explored in a separate

event. A fifth version, with an expanded presence for Nathaniel Dett, will be

seen at the Phillips Collection (DC) on August 22, retitled “The Spiritual in

White America.”

Here’s a Listening Guide:

PART ONE:

00:16: “Steal Away” (arr. Burleigh) sung by

Kevin Deas (Horowitz, piano)

14:41: “Sometimes I Feel” (arr. Burleigh) sung

by Deas (Horowitz, piano)

20:40: “Deep River” (arr. Burleigh) sung by

Marian Anderson

25:25: The history of “Deep River,” an obscure

upbeat spiritual first slowed down by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1905)

29:37: The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ recording of “Swing

Low” (1909)

34:08: The Fisk upbeat “Deep River” (1876), as reconstructed

by Gil-Ordonez

37:30: Maud Powell’s recording of the Coleridge-Taylor

“Deep River” (1911)

42:00: In sequence, Burleigh’s “Deep River”

(SATB), Burleigh’s “Deep River” (TTBB) with “Dvorak” introduction;

Dvorak/Fisher “Goin’ Home” (all with Washington National Cathedral Choir,

Gil-Ordonez conducting)

57:48: “The elephant in the room”: cultural appropriation

1:07:00: Burleigh sings “Go Down, Moses”

(1919); Sir Michael Tippett’s choral arrangement of “Go Down, Moses” (Deas,

Gil-Ordonez, Cathedral Choir)

1:15:30: “My Lord, What a Morning” (arr.

Burleigh) sung by Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez conducting

PART TWO:

00:00: Nathaniel Dett: “Oh Holy God” (National

Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez)

02:55: How classical music in America “stayed white,”

penalizing black composers

15:26: Dett’s The Ordering of Moses (conclusion) with James Conlon conducting the

Cincinnati Symphony

20:49: Dett: “Listen to the Lambs” sung by

Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez conducting

31:08: William Dawson: “There is a Balm in

Gilead” with Deas, Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez

37:10: “Where You There” (arr. Burleigh); Bach:

“Mache dich” from St. Matthew Passion with Deas, Cathedral Choir,

PostClassical Ensemble, Gil-Ordonez conducting

51:28: Bach: “Ich habe genug” (movement 1) with

Deas, PCE, Gil-Ordonez

(Igor Leschishin, oboe)

1:01:29: Bach: Air from Third Orchestral Suite

with PCE, Gil-Ordonez

February 8, 2019

Lou Harrison and The Great American Piano Concerto — Reprised

Eight years ago, on the occasion of PostClassical Ensemble’s first performance of Lou Harrison’s Piano Concerto with Benjamin Pasternack as soloist, I wrote in this space: “The music of Lou Harrison represents a rare opportunity for advocacy. To begin with, he is unquestionably a major late 20th-century composer, and yet little-known. Also, he is both highly accessible and stupendously original. And he is the composer of a Piano Concerto as formidable as any ever composed by an American.”

Two weeks ago, PostClassical Ensemble reprised the Harrison concerto, again with Ben Pasternack, again with Angel Gil-Ordóñez conducting. The venue, this time, was the great nave of the Washington National Cathedral, where it’s our good fortune to be Ensemble-in-Residence. The spiritual ambience, the resonant church acoustic redoubled the impact of this landmark American achievement. It is original, surprising, exalted. You don’t have to take my word for it. Here’s part of a review by Sudip Bose, the superb music critic (and managing editor) of The American Scholar:

“It was the piece I as most eager to hear, its opening movement as vast as a canyon . . . How could so magnificent a concerto be so woefully neglected? It’s a question that could be asked of all of Harrison’s music, which is in need of just this kind of evangelism.”

I here offer some further thoughts on this 1985 work, which should be standard repertoire for every American orchestra of consequence.

The first movement is indeed a sonorous canyon, as vast as the American West. Compositionally, it’s a technical tour de force: a terrific sonata form whose trajectory does not depend on directional harmony. Instead, Harrison uses rising scales and intensifying textures to drive toward a refulgent recapitulation. In our Pasternack/Gil-Ordóñez performance, that passage sounded like this:

Lou Harrison Piano Concerto, mvmt 1, PostClassical Ensemble with Benjamen Pasternack,

Angel Gil-Ordóñez Conducting

The second movement is one of Harrison’s “Stampede” scherzos — a tremendous moto perpetuo for the soloist, whose part includes a wooden “octave bar” for rapid-fire octave clusters on the black of white keys. Here’san excerpt from our PCE performance (with percussionist Bill Richards):

Lou Harrison Piano Concerto, mvmt 2, PostClassical Ensemble with Benjamen Pasternack,

Angel Gil-Ordóñez Conducting

The big third movement follows like a balm – it seals the concerto’s majestic amplitude. This Largo is a hymn sung with such gravitas that the Adagio of Brahms’ D minor Piano Concerto becomes a plausible point of reference. Here are Pasternack and Gil-Ordóñez:

Lou Harrison Piano Concerto, mvmt 3, PostClassical Ensemble with Benjamen Pasternack,

Angel Gil-Ordóñez Conducting

And yet Harrison’s finale is not a big Brahmsian rondo but — another original touch — a mere codetta: an ending perfectly gauged.

The Harrison Piano Concerto was composed for Keith Jarrett, who made the best-known recording. Jarrett’s keyboard command is miraculous, but his impersonality is an obstacle. No less than Pasternack, the Italian pianist Emanuele Arcuili (who plays more American piano music than any American ever has) is an inspired exponent of the Harrison concerto. It tells you some more about the piece that these readings – Jarrett, Arciuli, Pasternack – are utterly different from one another. In fact, the piano writing itself is so singular, so original, and yet so idiomatic as to invite a wide variety of voicings, pedaling, and rubatos.

I discovered this for myself when we undertook a five-minute filmed exegesis of the concerto’s Javanese roots, with the Harrison scholar Bill Alves in charge. With the help of the Indonesian Embassy Javanese Gamelan, Bill showed how layered gamelan textures generate Harrison’s layered keyboard textures – and I was the participating pianist. Here’s the film clip, which we screened as an introduction to the Harrison concerto while the stage was being re-set.

And so this is yet another dimension of Lou Harrison’s protean concerto – like so much of Harrison, it derives from his immersion in non-Western musical genres, Javanese gamelan in particular. This influence is profound: both atmospheric and compositional.

How to program such music? As PostClassical Ensemble is an “experimental orchestral laboratory,” the Cathedral’s great nave was reconfigured, with the orchestra in the center and (thanks to our indispensable partnership with the Indonesian Embassy) Javanese and Balinese gamelans at either end. Our three-hour concert told a story: how it is that, of all non-Western genres, Indonesian music has most influenced the Western tradition. The story begins with Debussy. It separately embraces Javanese and Balinese strands. It includes Ravel, Britten, Poulenc, Messiaen, Bartok, Reich – and also lesser known but vitally original composers like the Canadian Colin McPhee.

We began with Javanese music and dance, already playing as the audience entered the nave. Three dancers proceeded down the central aisle and froze in front of a piano – at which point Wan-Chi Su commenced Debussy’s Pagodas. The remainder of the first half comprised piano and two-piano music by Ravel, McPhee, Messiaen, Poulenc, and Bill Alves. The intermission featured Balinese music and dance.

Part two was the Harrison concerto, preceded by an earlier Harrison composition: the Suite for violin, piano, and chamber orchestra. Here again, the Cathedral setting told. As I learned from Bill Alves, this 1951 Harrison composition coincided with his immersion in Christian mysticism. As the gamelan influence is already apparent, the Suite is sui generis. In their invaluable Lou Harrison: American Musical Maverick (2017), Bill and Brett Campbell call it “one of the most surpassingly beautiful American musical creations of the 1950s . . . [it] closes with a softly swaying, melancholy chorale that reaches as deep into the heart as anything Harrison ever wrote.”

At our performance, the chorale was consecrated by stained-glass windows. Angel Gil-Ordóñez is a sovereign conductor of all and any slow-motion music. Our exceptional concertmaster, Nati Draiblate, was the violin soloist. It sounded like this:

Lou Harrison Suite for Violin, Piano and Orchestra, PostClassical Ensemble with Netanel Draiblate and Wan-Chi Su, Angel Gil-Ordóñez Conducting

Sudip Bose, in his American Scholarreview, memorably summarized: “These days, the word fusion . . . has become a cliché. But here was a vivid, persuasive argument in favor of embracing a fluid world culture. Works of the imagination should not be limited by borders, or by walls, and when art is born out of reverence, we the public should not be impeded by questions of ownership and accusations of appropriation. Not when the artworks in question move and enrich us all.”

To which Bill Alves adds: “Lou’s attitude was something he inherited from Henry Cowell – that everything in the world should be considered a legitimate influence. And Lou’s idea was also part of his universalistic orientation. His advocacy of Esperanto is another example. In his book The Music Primer, Lou points out that drawing musical borders is an artificial process – that really music changes by degree as one crosses geographical borders around the world.”

PostClassical music increasingly demands its own venues and formats. Its master prophet was Lou Harrison: an elusive yet iconic American original.

His time will come.

(Stay tuned for a “PostClassical” podcast on the WWFM Network with the complete Harrison Piano Concerto, as performed by PCE on January 23 at the Washington National Cathedral. For filmed excerpts from the concert, here is a vivid feature by Indonesian Voice of America.)

December 19, 2018

Falla and Flamenco — “The Birth of Spanish Music”

According to my friend the remarkably loquacious Spanish pianist Pedro Carboné, the “birth of Spanish music” occurs during the third of Manuel de Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain. Pedro made this argument at length on our most recent “PostClassical” broadcast: “Falla and Flamenco.” And he clinched it by citing his distinctive live performance of this piece with PostClassical Ensemble.

You can hear what Pedro’s talking about by gong to 1:03:00 here. Bill McGlaughlin, who hosts “PostClassical,” was duly impressed. He called the birth-moment in question “heart-stopping.”

Like so much of Spanish culture, Falla (1876-1946) embodied a confluence of Moorish, North African, and Catholic ingredients. As Pedro experiences Nights in the Gardens of Spain, movement one – a fragrant tone poem evoking the Alhambra’s iconic Generalife gardens – shows “what Spain was”: Moorish. In movement two, “the gypsies arrive” with an exotic song juxtaposed with a Moorish dance. And movement three is a fusion: the music “never heard before.” The work’s exalted coda tracks the departure of the Moors. It’s an inspired reading – and so is Pedro’s actual performance.

Pedro’s gift for descriptive aplomb peaks with his detailed explication of another, more rarified Falla composition: the Concerto for harpsichord or piano. This is “late Falla,” meticulously and painstakingly composed in 1923-26 — by which time Falla had discarded the flamenco influence that previously impelled his ceaseless search for the Spanish soul. Here is a composition that usually makes no sense in performance. The reason, as Pedro shows, is that Falla is in fact undertaking an “encapsulation of the history of Spanish music.”

The concerto’s first movement fractures –almost as Stravinsky might – a famous medieval Spanish song: “De los alamos vengo, madre.” The second movement, called by Ravel the greatest chamber music of the twentieth century, is an austere religious epiphany – an homage to the stark Catholic grandeur of the siglo de oro. The finale celebrates the Spanish harpsichord school of the eighteenth century: Scarlatti and Soler. And of all of this, Pedro adds, is couched “in the language of the twentieth century.” Falla skips the nineteenth century – the century of zarzuela – because he disdains it.

PostClassical Ensemble has many times presented the Falla concerto with Pedro, conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez. We quickly discovered that audiences were clueless unless we contextualized this dense fifteen-minute identity quest precisely as Pedro does. So to introduce movement one we of course perform “De los alamos.” For movement two Angel conducts motets by Tomas Luis d Victoria. And we combine the finale with some Soler.

It’s all on our “PostClassical” broadcast.“ And you can hear Bill McGlaughlin discover the originality of this rarely performed masterpiece; responding to movement two, he exclaims: “I have to admit, that piece is really hard for me to understand. I hear about seven different directions in it” — ranging, Bill continues, from music resembling a Lutheran chorale, to mellifluous cascades he likens to Saint-Saens, to “some really cold, acerbic modern stuff.”

Pedro makes an even more revelatory statement, to my ears, in Falla’s Fantasia Betica, composed in 1919. It’s the last of his flamenco-inspired creations, and the most radically harsh in its quest for authenticity. As Pedro explains, Falla conceived it as a corrective to his “Ritual Fire Dance,” which he heard Artur Rubinstein perform as a flashy encore. He decided to give Rubinstein a virtuoso solo keyboard piece with more pianistic and musical substance. Rubinstein played the Betica once and never again – it’s not intended for popularity. Pedro’s rendition is weighty and hard; it treats flamenco with the same gravitas as Falla did. You can hear it on part two of our broadcast, at 12:41. If you’re interested in sampling an antithetical reading, swifter and wondrously refined, here is Alicia de Larrocha. But Pedro will have none of that: “Don’t rush!” he explodes.

The overall argument is that austerity defines Spain. For Pedro and Angel, the aestheticization of “Spain” by such French composers as Bizet, Debussy, Ravel, and Chabrier is precisely “French,” not “Spanish.” And their Falla performances follow suit. I have written about this before, in my 2010 blog, “The Problem with De Larrocha.”

Angel therefore regards Victoria, not Falla, as Spain’s greatest composer: a musician as austere as the Escorial itself. Assessing the reinvention of Spanish music undertaken by Falla at the turn of the twentieth century, he references Spain’s loss of its colonial empire and the birth of “modernismo” – for Spanish artists and intellectuals, a striving to reconnect with mainstream European aesthetic innovation after a century of insular provincialism.

This topic is owned by the pre-eminent contemporary Spanish novelist: Antonio Munoz Molina, who happens to be a frequent participant in PostClassical’s ongoing “Search for Spain in Music.” Antonio emphasizes the initial energy of Spanish modernism, reminding us that Berg’s Violin Concerto was premiered in Spain and that Schoenberg composed some of Moses und Aron in Barcelona. Then came the elephant in the room – Francisco Franco. Modernismo was prematurely terminated. And Falla emigrated to Argentina, where his creative gift lapsed. He belongs in the company of Ives, Elgar, and Sibelius – all composers who stopped composing long before they stopped living. All of them, I would say, were estranged by twentieth century aesthetics. In Falla’s case, the impact of Stravinsky seems to have shattered his stylistic base. The Concerto was one result. His two final decades of relative silence were another.

Our broadcast ends with another Spanish composer Pedro Carboné re-understands: Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909). Like Falla, Albeniz undertook a renewed search for Spain. Like Falla, he embodies a confluence privileging flamenco. Like Falla, he is both popular and little understood, at least in theUS.

A central problem is Enrique Arbos – the eminent Spanish conductor who transcribed five movements from Albeniz’s solo piano masterpiece: Iberia (1905-1909). When I was young, the Arbos versions of Iberia were more heard than the Albeniz versions. And they are radically different: so simplified in texture and affect as to approximate a Hollywood reductionism.

The real Iberia is monumentally dense. Olivier Messiaen called it “the wonder of the piano, the masterpiece of Spanish music which takes its place – and perhaps the highest – among the stars of first magnitude of the king of instruments.”

And that’s the Iberia Pedro champions. No one makes this music sound more knotted or unrelenting. Again, the antithesis is de Larrocha. On our “PostClassical” broadcast, you can sample Arbos’s technicolored rendering of “Triana,” from Iberia book two. And you can hear Pedro’s “Triana.”

In the WWFM studio, Pedro collapsed in pain during our audition of Arbos’s Albeniz. He recuperated to introduce “Rondena,” also from Iberia book two. It is my favorite Carboné performance. Whether or not it captures the soul of Spain I cannot say. That it is authentically soulful I have no doubt.

Albeniz studied with Liszt. Falla was an appreciable keyboardist; you can hear his premiere recording of his Concerto on our radio show. They both wrote for the piano as only a pianist could. In the lineage of notable pianist/composers, Albeniz and Falla belong right up there with Mozart and Beethoven, with Liszt and Busoni, with Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich. To my ears, their most singular – and most voluble — advocate is Pedro Carboné.

The “Falla and Flamenco” installment of“PostClassical,” lovingly produced by Dave Osenberg for the WWFM ClassicalNetwork, is here.

Listening Guide:

PART ONE:

00:00: Flamenco as a source for Spanish cultural identity

7:30: “Austerity” as the “essence” of Spanish music, distinguishing it from the French “Spanish” style.

10:48: Falla’s El Amor Brujo (excerpts) with PCE and flamenco cantaora Esperanza Fernandez

21:20: Commentary on Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain and “the birth of Spanish music”

26:32: Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain, movement one, with Pedro Carbone and PCE

44:45: Commentary on Nights, movements 2 and 3

49:44: Nights, movements 2 and 3, with Pedro Carbone and PCE

1:03:00: “The first Spanish tune”

PART TWO:

00:00: Falla’s Fantasia Betica and the “quest for authenticity”

12:41: Fantasia Betica, performed by Pedro Carbone

27:24: Artur Rubinstein and the Fantasia Betica

33:44: Falla and the challenge of modernism; cf Ives, Elgar, Sibelius; the Falla keyboard concerto as the “encapsulation of the history of Spanish music”

35:41: Discussion of the Falla concerto, movement 2 as a religious epiphany

38:59: Falla concerto, movement 2, performed by Pedro Carbone and PCE

49:50: Spanish religious austerity — Tomas Luis de Victoria: “Caligaverunt oculi mei” conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez

55:40: “De los alamos vengo, madre” and the Falla concerto

56:40: Falla concerto, movement 1, performed by the composer

1:01:53: Falla concerto, movement 1, performed by Pedro Carbone and PCE

1:07:53: Soler and the Falla concerto

1:10:50: Falla concerto, movement 3, performed by Pedro Carbone and PCE

PART THREE:

4:24: “Triana” by Abeniz, transcribed/performed

by Enrique Arbos

15:26: “Triana” performed by Pedro Carbone

25:46: Francisco Franco as “the elephant in the room”

32:07: “Rondena” by Albeniz, performed by Pedro Carbone

December 8, 2018

High Culture Without Apologies — What Orchestras Can Do

The current Weekly Standard has a long piece by me about the future of American orchestras. I write that orchestras can help us to heal our shredded national fabric and regain a lost “sense of place” – a shared American identity via our history and culture. And yes, I mean high culture.

I continue in part:

“Our colleges don’t teach much history any longer. Many cultural institutions seem increasingly adrift. And yet I have stumbled upon an unlikely alliance that works: orchestras in partnership with universities. . . .

“If orchestras are ever to regain their role as agents of national unity, they will need to undertake a larger mission and curate the American past. . . . It must be understood that orchestras in the US have evolved very differently from museums. There are no scholarly curators on staff. The American musical past is little known or exhumed, nor is any cultural context outside of classical music. . . .”

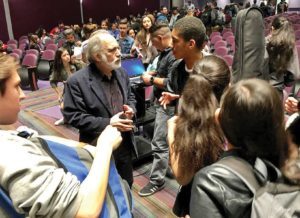

The picture above, from my Weekly Standard article, shows me interacting with students in an El Paso colonia as part of an NEH-supported Music Unwound festival binding the El Paso Symphony to the University of Texas/El Paso, and to the El Paso public schools.

To read the whole piece, click here.

November 26, 2018

How South Dakota Shows What Orchestras Are For

Beginning in the 1860s, the conductor Theodore Thomas – a symphonic Johnny Appleseed – began touring the entire United States with his Thomas Orchestra. His credo was: “A symphony orchestra shows the culture of the community.” And in cities large and small, it did.

Today, the American orchestra is no longer the civic bulwark it once was. There are exceptions. I would say that the Chicago Symphony is one. That’s partly because Thomas himself was the founding music director, in 1891; and because he was succeeded by his assistant, Frederick Stock, through 1942. That is: For half a century, the Chicago Symphony had only two primary conductors, both German-born. It also happens to be the only American orchestra whose founding music director was a major conductor. And so it retains a central place in Chicago’s identity. It also retains an anchoring Germanic identity, Riccardo Muti notwithstanding.

But the American orchestra that most shows the culture of the community can only be the South Dakota Symphony. As I have previously written in this space, it is our most exceptional orchestra. I am just back from a week in South Dakota, and my impressions have only deepened.

The occasion was a third Music Unwound festival, funded by the NEH. Previously, we undertook “Dvorak and America” (bringing the New World Symphony to an Indian reservation) and “Copland and Mexico” (for which the musicians lustily sang Copland’s Communist workers’ song “Into the Streets May First!” – even though several had scurrilously threatened to “take a knee”). This season’s Music Unwound immersion experience was “American Roots.” It comprised two subscription concerts, three young people’s concerts (filmed by South Dakota public TV), ancillary concerts and a master class at two universities, and the participation of two middle school Social Studies classes (with sixty seventh graders reading my young readers book Dvorak and America). The total attendance was something like 6,000, and covered a geographic radius of 150 miles.

The SDSO subscription audience is by far the most diversified in age I have ever encountered at a professional symphonic concert (and I have been around). And yet the programing is bold. The main work on “American Roots” was Charles Ives’s Symphony No. 2. The current season also includes Mahler’s Eighth (completing a Mahler symphony cycle), Sibelius’s Seventh, concertos by Nielsen and Lalo, and new music by Jeffrey Paul (the orchestra’s superb principal oboe) and Erik Larsson.

Alongside all that, the orchestra pursues its signature Lakota Music Project, producing side-by-side concerts at Indian reservations that juxtapose classical music with Native American works.

But the most remarkable aspect of the South Dakota Symphony, for any observer as venerable as myself, is the attitude of the musicians. They are engaged. They are mission-driven. As I had occasion to tell them at an Ives rehearsal: “This orchestra is so friendly it’s disorienting.”

Many factors are in play. Sioux Falls is full of orchestras. The middle school I visited has three of them. The SDSO itself maintains three youth orchestras (I heard a rousing youth-orchestra rendition of the Mussorgsky/Rimsky Night on Bald Mountain). With 250,000 people, the metropolitan area is small enough to facilitate community. A recent influx of immigrants from North Africa and Southeast Asia seems assimilated with forethought and good will. But the singular vision of the SDSO music director, Delta David Gier, is paramount. He moved to Sioux Falls and raised a family there. He concocted the Lakota Music Project. He has initiated programing featuring Ghanaian, Persian, and Chinese instrumentalists and composers. He has elevated the standard of performance to a startling height of conviction and finesse. He is a thinker and a leader.

The point of “American Roots” (which like all Music Unwound programs migrates around the US, adapted to local needs and desires) is to introduce audiences to Charles Ives. He is arguably the most important American composer of classical music. He is little performed. His eccentricities are considered forbidding. He was long viewed with suspicion by lesser Americans like Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. (I do not know of a subsequent American symphony as cannily assembled as are the five movements of the Ives 2, completed around 1909; such works as the Third Symphonies of Copland and Roy Harris seem lopsided and uneven by comparison.)

And yet Ives is easy to humanize, because he was a great man. One Music Unwound presentation, “Charles Ives: A Life in Music,” intermingles Ives songs (peerlessly – and I mean peerlessly – sung by William Sharp) with letters. One of those, from his daughter Edith, began:

“Dear Daddy,

“You are so very modest and sweet Daddy, that I don’t think you realize the full import of the words people use about you, ‘a great man.’

“Daddy, I have had a chance to see so many men lately – fine fellows, and no doubt the cream of our generation. But I have never in all my life come across one who could measure up to the fine standard of life and living that you believe in, and that I have always seen you put into action no matter how many counts were against you. You have fire and imagination that is truly a divine spark, but to me the great thing is that never once have you tried to turn your gift to your own ends. Instead you have continually given to humanity right from your heart, asking nothing in return; — and all too often getting nothing. The thing that makes me happiest about your recognition today is to see the bread you have so generously cast upon most ungrateful waters, finally beginning to return to you. All that great love is flowing back to you at last. Don’t refuse it because it comes so late, Daddy.”

Once contextualized, the often cantankerous Second Symphony is infectious. By “contextualized,” I mean that the Music Unwound program precedes the symphony with a half dozen tunes that Ives quotes, beginning with “Camptown Races” (sung by Bill Sharp with banjo accompaniment). We demonstrate how Ives uses another Stephen Foster tune, “Old Black Joe,” as the second subject of his Civil War finale, and thereby (as he once explained in a futile attempt to interest the New York Philharmonic) expresses sympathy for the slave.

All that comprised the second half of the SDSO subscription program. The first half began with a minstrel song played by banjo and spoons (SDSO principal percussionist John Pennington proved an electrifying spoon virtuoso). Gier then revealed that the tune just heard was composed by . . . Antonin Dvorak. It’s the A major second theme in the finale of his American Suite, transforming an A minor Indian dance. This 1894 Dvorak composition, still scandalously little-known, comprises a stack of American postcards. The Music Unwound performance of Dvorak’s suite incorporates a visual presentation created by my longtime colleague Peter Bogdanoff; adapted for Sioux Falls, it features the South Dakota artists Oscar Howe and Harvey Dunn depicting the Dakota flatland in juxtaposition with Dvorak’s evocation of the Iowa prairie he knew as of 1894. The result looked like this:

Another South Dakota ingredient was the participating pianist: Paul Sanchez, a Sioux Falls native. Sanchez’s account of Rhapsody in Blue was original – the most bewitchingly lyric I have ever encountered. This beloved work is what sold the concert, but was no sell-out: a straight line runs from the American Dvorak to Gershwin, and we clinched it with Dvorak’s G-flat Humoresque – the bluesy music that inspired Gershwin to become a composer.

The scripted, multi-media program I have just partly described ran 70 minutes on the first half and another 65 on part two. Gier likes long programs. Many in the audience stayed put to talk. The topic, framed by my script, was “What is America?” Inescapably, our discussion fixed on issues of race.

Next October, the SDSO Lakota Music Project travels to DC for a festival – tentatively titled “Native American: From Spillville to Pine Ridge” – that my PostClassical Ensemble will produce at the Washington National Cathedral. The National Museum of the American Indian will also take part. The South Dakota contingent will include Gier, nine SDSO members, two distinguished Native American musicians, and an ethnomusicologist. One of the participating players will be the orchestra’s principal clarinetist, Chris Hill – a 32-year SDSO veteran. Over lunch, I asked Chris if he were aware of the DC project. He answered that, as a member of the SDSO board, he had insisted on casting the first vote in favor.

I was with Bill Sharp (whose impressions of the SDSO echo my own, as do those of David Hyslop, who managed the St. Louis Symphony and Minnesota Orchestra and is currently the SDSO interim CEO). Bill remarked to Chris that the orchestra’s Sommervold Hall is one of the most acoustically impressive in which he has had occasion to perform. (Bill has performed in many halls.) Chris said: “I helped to design it.” Sommervold may in fact be the best orchestral auditorium to be found among the countless multi-purpose halls constructed around the turn of the twentieth century. The idea was to accommodate the local orchestra and lucrative itinerant musicals in one and the same space. It failed elsewhere because the resulting space was too big; the builders were intent on maximizing box office revenue. Sommervold has only 1,800 seats; it prioritizes the South Dakota Symphony.

Chris added that he conducts the Sioux Falls Municipal Band, now celebrating its centenary. There are 24 bandshell concerts every summer. Any Ives? we asked. Of course, he answered.

*. *. *

To sample the South Dakota Symphony’s Music Unwound “Copland and Mexico” production, click here.

Sioux Falls has a public radio station that broadcasts extensive arts interviews. To hear Joe Horowitz in conversation with SDSO Music Director Delta David Gier, click here.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers