Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 24

September 18, 2018

Rachmaninoff Uncorked

Today’s “Wall Street Journal” includes my review of “one of the most searing listening experiences in the history of recorded sound” — the new Marston Records 3-CD set: “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances” — which you can sample here. My review reads:

One of the saddest and most paradoxical artistic exiles of the 20th century was Sergei Rachmaninoff, who fled the Russian Revolution and wound up in New York and Los Angeles, in equal measure celebrated and obscure.

Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) left Moscow a composer and conductor of high consequence who also played the piano. Yet in America he barely conducted and his compositional output plummeted. To earn a living, he turned himself into a keyboard virtuoso of singular fame and attainment—a late embodiment of the heroic Romantic piano lineage beginning with Franz Liszt. Offstage, he retained a lonely Russian home and Russian customs. His severe crewcut and gimlet eyes disclosed little to the world at large. His personal poise was awesome and implacable.

Rachmaninoff’s privacy took other forms. He refused permission to have his concerts broadcast, effectively preventing any documentation of what he sounded like in live performance. Instead, he recorded extensively for RCA. But, absent the oxygen a body of listeners can activate, those readings are as celebrated for their emotional control as for their sovereign interpretive mastery. They enshrine kaleidoscopic miracles of color and texture wedded to a vice-like command of musical structure. But the cap remains on the bottle.

No longer. A decade ago, a researcher was browsing a collection left by the conductor Eugene Ormandy to the University of Pennsylvania—and read: “33 1/3:12/21/40: Symphonic Dances…Rachmaninoff in person playing the piano.” That is: Ormandy had privately recorded Rachmaninoff playing through his “Symphonic Dances” prior to Ormandy’s premiere performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra in January 1941. This turned out to be no morsel, but 26 minutes of a 35-minute composition. And it’s now embedded in a three-CD Marston set titled “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances.” The result is one of the most searing listening experiences in the history of recorded sound.

Most of the best piano recordings are made in concert. They’re not as perfect as studio products, but by and large they’re more spontaneous, more intense, more creative. Vladimir Horowitz, an intimate friend, claimed that only one of Rachmaninoff’s commercial recordings—that of the second movement of his own First Concerto, recorded in 1939-40—gave a fair impression. If you listen to that recording, you’ll easily ascertain what Horowitz was talking about—the opening solo is untethered.

As privately imparted to Ormandy, Rachmaninoff’s impromptu solo-piano rendering of his “Symphonic Dances” documents roaring cataracts of sound, massive chording, and pounding accents powered by a demonic thrust the likes of which no studio environment has ever fostered. Rachmaninoff’s humbling presence, re-encountered, is gigantic, cyclopean.

And there is more: the piece itself; it is Rachmaninoff’s valedictory. Summoning his waning creative energies in this last major work, he fashioned his musical testament. The dances originally bore titles: “Midday,” Twilight,” “Midnight.” These are stations of life. The finale ends in a blaze of glory; near the close, Rachmaninoff inscribed: “Alliluya.”

But the work’s most poignant moment comes in the first movement coda, which cites and pacifies the “vengeance” motto of the confessional First Symphony, a youthful effusion Rachmaninoff discarded following its disastrous 1897 premiere. It is music as naked as the nostalgic Rachmaninoff of the Second Piano Concerto is decorous: a baring of the soul. The First Symphony was completely unknown in 1940 (only in 1944 was a set of parts discovered). And so Rachmaninoff’s allusion in the “Symphonic Dances” is a soul-baring even more private than his piano-rehearsal with Ormandy. In terms of his creative odyssey—his exile and accommodation in a strange land—it is nothing less than a closing of the circle.

How does Rachmaninoff himself perform this secret passage, the meaning of which was his alone? Very slowly, lingeringly. Even more affecting is his treatment of the movement’s second subject, a long saxophone melody he invests with a heaving surge and ebb of feeling, imparting a trembling undertow of anguish, of memories faraway and yet unresolved. The second movement waltz, under Rachmaninoff’s fingers, is an essay in macabre shadow-play. The final dance is primal. The work emerges as an iconic leavetaking as bittersweet as any Mahler Abschied.

I own a 10-volume 1954 edition of “Grove’s Dictionary of Music” that allots to “Rakhmaninov” less than a page. It contains the sentence: “The enormous popular success some few of [his] works had in his lifetime is not likely to last, and musicians never regarded it with much favour.” Today that sentiment is as forgettable as Rachmaninoff is imperishable.

The little box containing these Rachmaninoff memories within memories includes other rarities. I cannot imagine a better introduction to this artist at his true worth. It stands as a rebuke to the slickness that often passes for Rachmaninoff interpretation nowadays. More than a lost art, it documents a lost world.

September 13, 2018

What Are Orchestral Musicians For?

Years ago, before I was shown the door, I briefly taught at the Manhattan School of Music within their graduate program for aspirant orchestral musicians. My intention was to impart some knowledge about the history of the orchestra in order to shed light on the decline of orchestras and of orchestral performance – and to suggest that young musicians might be able contribute constructively.

Years ago, before I was shown the door, I briefly taught at the Manhattan School of Music within their graduate program for aspirant orchestral musicians. My intention was to impart some knowledge about the history of the orchestra in order to shed light on the decline of orchestras and of orchestral performance – and to suggest that young musicians might be able contribute constructively.

I boldly inflicted both reading and writing assignments.

The class was large (it was in fact required) – more than 50 instrumentalists. The majority tolerated my course. A vocal minority found it revelatory. And equally vocal minority found it an imposition; they refused to read or write. (The administration backed the dissidents.)

One day I brought my friend Larry Tamburri to address the class. At the time, he was CEO of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, where he had succeeded in creating a unique institutional culture. The NJSO musicians were partners. Some sat on the board. Some had artistic input. Astoundingly, Larry’s strategy enabled him to negotiate contracts with the players without the participation of attorneys.

(Subsequently, as CEO of the Pittsburgh Symphony, Larry discovered himself unable to achieve what he had accomplished in New Jersey. I noticed, sometime later, that when the Pittsburgh Symphony players went on strike in 2016, they insisted on distinguishing themselves from the institutional identity of the PSO. This us-versus-them mentality, pitting musicians against “management,” remains pervasive.)

In my class, Larry drew two circles on the blackboard, a big one and a little one. The little one, he explained, signified the traditional institutional role of orchestral musicians. The big one showed what orchestral musicians needed to become: full institutional participants. Larry said that he was having trouble finding young big-circle instrumentalists for his orchestra.

In my various orchestral adventures and misadventures, I had occasion to take part in the ritual of contract negotiations as CEO of the Brooklyn Philharmonic in the 1990s. I discovered that members of the orchestra with whom I thought I had a decent personal relationship became different people when seated on the opposite side of a table. A counter-example is the South Dakota Symphony, about which I have often written in this space. That is an orchestra full of big-circle musicians.

In PostClassical Ensemble – the renegade DC chamber orchestra I co-founded fifteen years ago with the conductor Angel Gil-Ordóñez – our big-circle contingent includes our principal trumpet, Chris Gekker. Now in a late phase of his career, Chris is one of the best-known brass players in the US. No other member of PCE is more keenly engaged by the intellectual content of our programing. Chris is also one of two PCE players who sits on our board of directors (the other being Bill Richards, our splendid principal percussionist).

Chris’s big-circle attitude, I am certain, has something to do with a decision he made at the age of 25. Even though he had access to membership in major orchestras, he decided that he would pursue a different career trajectory and restrict his orchestral playing to part-time positions. So he became principal trumpet of both Orpheus and of the Orchestra of St. Luke’s in New York. He occasionally subbed as principal trumpet with the New York Philharmonic, or the San Francisco Symphony, or the Santa Fe Opera. And he simultaneously pursued a free-lance solo career including jazz and recording gigs. So he retained independence.

Chris grew up outside DC. He’s recalled: “My parents were both European immigrants; my sister and I are the first Americans in our family. In addition to hearing various languages spoken at home, there was music; they both knew a good deal, and my father was a fine amateur pianist, playing Brahms, Schumann, Schubert, and his beloved Russian music. Outside the house, in the 1960s, the sounds of soul and rock bands were everywhere, and I began playing in bands very early, so I had exposure to a lot of music.”

Chris’s unusual qualities as a person correlate with his eclectic background. I also believe that his professional independence correlates with his unusual qualities as a trumpeter. His style of playing is utterly personal – but subtly so. The clarion swagger many associate with the trumpet is not for him. Rather, he has developed a lyric vein of his own.

I cherish many memories of Chris Gekker in performance with PostClassical Ensemble – e.g., the cantabile solos in the second movements of both Gershwin’s Concerto in F and of Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 1 (our soloist, Alexander Toradze, called Chris “free as a bird – he creates on the fly”). But mainly I remember his contribution to Silvestre Revueltas’s fabulous score for the film Redes – music we have both performed and recorded. With the Mexican bandas of his childhood always in his ear, Revueltas is a creative and demanding composer for brass. His tuba parts are unique. In Redes, he creates a work-out for solo trumpet that is grueling and rewarding in equal measure.

Near the end of this hour-long film, there is an exquisite muted trumpet solo marked “piano.” I have produced Redes performances (the film with live music, plus exegesis) with more than half a dozen American orchestras. Chris is the only player who has so much as attempted to play this solo really softly, let alone pulled it off memorably. Our Redes recording documents his first take, at the tail end of four days of rehearsal and performance. Accompanying a funeral procession (one of this film’s many indelible episodes, with cinematography by Paul Strand), it sounds like this, with PostClassical Ensemble conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez:

http://www.artsjournal.com/uq/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Gekker-Excerpt.mp3

Chris once shared with me his sublime second movement solo in Gunther Schuller’s recording of Gershwin’s Concerto in F, with Russell Sherman at the piano. It sounds like this

http://www.artsjournal.com/uq/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Gershwin-Concerto.mp3

Typically, Chris had something interesting to say about it:

“Gunther used the original Paul Whiteman Band scoring – which you didn’t hear in those days. The Gershwin estate actually tried to stop him. They only wanted the symphonic version to be known. The trumpet solo in that standard orchestral version is marked ‘with felt crown’ — so it’s usually played with a soft hat mute, often literally a cloth hat or beret. In the Whiteman version, it’s marked ‘megaphone mute.’ No one knows exactly what that means — no such mute exists nowadays. Gunther brought one for me to use. In the original Whiteman performances, the solo was played by Charlie Margolis, who was the premier free-lance trumpeter in NYC during the ‘20s, commanding triple scale wherever he played, and in constant employment by radio company orchestras. The original parts, which Gunther used, just had people’s names on them, not ‘trumpet 1,’ ‘trumpet 2,’ etc. Bix Beiderbecke was in the band, he was a notoriously bad reader, so there is a trumpet part for him but it is mostly blank; according to Gunther he was expected to be onstage but was not given much to do during the Concerto.”

Chris’s most recent CD is titled “Ghost Dialogues.” The music is intimate. It ranges in style from classical to jazz. I was especially stirred by the title number, composed by Lance Hulme; Chris is here joined by the terrific saxophonist Chris Vedala. In an interview in Fanfare Magazine, pegged to “Ghost Dialogues,” Chris renders his high school impressions of Miles Davis and Maurice Andre, of Bobby Hackett and Ray Nance, of John Ware’s posthorn solo in the Bernstein/NY Phil Mahler Third and says “I loved the sound of the trumpet played softly.”

Chris Gekker is also a teacher – and has been a member of the faculty of the School of Music at the University of Maryland (College Park) since 1998. I have no doubt that his special qualities as a person make him a special pedagogue.

In fact, this past summer he became the first member of the School of Music faculty to be named a Distinguished University Professor.

For a filmed interview with Chris Gekker, by PCE’s resident film-maker Behrouz Jamali, click here.

September 11, 2018

THE FUTURE OF ORCHESTRAS — Part Six: What’s an Orchestra For?

Back in the 1990s, Harvey Lichtenstein – who recreated the Brooklyn Academy of Music – invited me to lunch and asked me if I wanted to run an orchestra.

Back in the 1990s, Harvey Lichtenstein – who recreated the Brooklyn Academy of Music – invited me to lunch and asked me if I wanted to run an orchestra.

Harvey had just read my notorious Jeremiad Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American Culture-God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music. That was published by Knopf when a book about classical music might generate four or five dozen major reviews, including Newsweek and Time.

Understanding Toscanini ends with a diatribe about Lincoln Center. I speculate that if an audience exists for a refreshed, reconsidered presentation of classical music in live performance, it would be the inquisitive and diversified audience Harvey had cultivated at BAM.

BAM had its own orchestra: the Brooklyn Philharmonic. Harvey had some years before decided to jettison traditional programing. He had also jettisoned the orchestra’s remarkable music director, Lukas Foss, in favor of Dennis Russell Davies – a gifted conductor of world stature who better fit BAM’s “Next Wave” identity. In response, audience members flung their subscription renewal forms at the musicians’ feet backstage and the Brooklyn Philharmonic lost over two-thirds of its subscribers. So in offering me the Brooklyn Philharmonic, Harvey had nothing to lose.

I took him up on it on condition that I could experimentally implement thematic, cross-disciplinary programing – and nothing else — in place of the traditional overture/concerto/symphony template. Harvey liked that idea and a wild ride ensued.

The biggest Brooklyn Philharmonic festival, in 1994, was “The Russian Stravinsky,” based on Richard Taruskin’s ground-breaking research into Stravinsky’s Russian roots. Richard came, and so did (at his suggestion) Dmitri Pokrovsky’s revelatory Pokrovsky Folk Ensemble from Moscow. We also had half a dozen interesting scholars at hand. There were three concerts, all exploring new formats. The festival was reviewed all over the place, including scholarly journals. It felt important – it made the orchestra matter.

Some years later, BAM discovered itself deeply in debt and the financial relationship between BAM and the Brooklyn Phil collapsed – which precipitated my departure and foredoomed the orchestra itself (which no longer exists). Nevertheless, the new artistic template worked (we rebuilt an audience) – and I have ever since pursued humanities-infused thematic programing. That’s the nub of the NEH-funded Music Unwound consortium I direct.

The humanities template flourishes in its purest form, however, in DC, where fifteen years ago I co-founded PostClassical Ensemble with the wonderful Spanish conductor Angel Gil-Ordóñez. We just announced our Fifteenth Anniversary Season. The big events are at the Washington National Cathedral, where we’re Ensemble-in-Residence. You won’t find anything like them anywhere else. They furnish an original answer to the question: What’s an orchestra for?

In a recent blog about Leonard Bernstein, I wrote about “curating the past.” That’s something conductors and orchestras should do – and don’t. Next January 23, PCE is curating the past with a program called “Cultural Fusion: The Gamelan Experience.” Its starting point is the observation that gamelan is the non-Western musical genre that (by far) has most influenced the Western classical tradition. This story (which, amazingly, has yet to generate a book) begins with Debussy’s discovery of Javanese musicians and dancers at the 1889 Paris Exposition — the one with the Eiffel Tower. He later wrote:

“But my poor friend! Do you remember the Javanese music, able to express every shade of meaning, even unmentionable shades which make our tonic and dominant seem like ghosts? . . . Their school consists of the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind in the leaves, and a thousand other tiny noises . . . what force one to admit that our own music is not much more than a barbarous kind of noise more fit for a traveling circus.”

The story continues with Ravel, Poulenc, Messiaen, Britten, and Harrison – as well as lesser known composers of consequence like Colin McPhee. Both Javanese and Balinese gamelan – the first fragrant, the second metallic — cast their spell. For our concert, we’ll transform the cathedral’s Great Nave into an exotic cultural kaleidoscope, with Javanese and Balinese gamelan and dancers, archival film, two pianists, and a chamber orchestra.

The entire exercise is a sequel to the 1996 Brooklyn Philharmonic festival “Orientalism,” which featured two gamelan and a roster of distinguished participants including Steve Reich. It was also at BAM that (thanks to Dennis Russell Davies) I met and fell under the spell of Lou Harrison.

Harrison’s synthesis of Javanese gamelan sounds and techniques with the Western tradition is a profound achievement – and has been a longstanding PCE cause. (Our Harrison Centenary CD has been widely acclaimed abroad [and mainly ignored in the US]; we also produced a Harrison Centennial radio special.) In fact, Lou Harrison is one of three composers PCE has most championed – the other two being Silvestre Revueltas and Bernard Herrmann. With the waning of modernism (whose canons they did not endorse), these are twentieth-century masters whose time will come. And one of the things that orchestras are for is to support missionary work for composers who need and deserve it (cf. Bernstein and Mahler; Bernstein and Ives; Bernstein and Nielsen).

PCE’s month-long Bernard Herrmann festival in 2016 celebrated his versatility as “the most under-rated twentieth century American composer.” Herrmann’s justly famous film scores (Psycho, Vertigo, etc.) were juxtaposed with the inspirational war-time radio dramas he scored for Norman Corwin, and with his neglected concert music (of which his bewitching clarinet quintet is my favorite chamber music by any American).

In the course of all that, we struck gold: the 1944 Corwin/Herrmann radio drama “Whitman”; revisited in live performance, it turned out to be a major American concert work. That was with a student actor as Whitman, at the National Gallery of Art. And so on June 1, at the National Cathedral, our next Herrmann tribute will include “Whitman” with the distinguished American baritone William Sharp in the title role. The performance – celebrating Walt’s 200th birthday — will be broadcast live over the WWFM Classical Network. And we’ll record “Whitman” and two other Herrmann works for Naxos.

Our goal: to instate Bernard Herrmann’s “Whitman” as a concert melodrama (in musical parlance: a work mating music with the spoken word) of high consequence, a significant addition to the American symphonic repertoire.

And we have one more National Cathedral concert, on Nov. 5: “I Sing the Body Electoral.” Another Whitman celebration, it attempts to engage Whitman’s democratic ethos to ignite a musical town meeting on the eve of the crucial mid-term elections. Is that also something orchestras are for? We will find out.

For more on PCE and Bernard Herrmann, click here. For PCE’s two-hour Bernard Herrmann radio special, click here. To access the original 1944 “Whitman” radio play (with Charles Laughton – and terrible sound) click here. To survey PCE’s four 2018-19 events at the Washington National Cathedral, go to postclassical.com

vonicfic, and also the orchestra’s gifted music director, Lukas Fosssic abrcherchrbucaHarvey rea

August 29, 2018

On Rescuing a “Dead Art Form” — Take Two

It seems to me pretty obvious that nowadays it’s far easier to stage a successful Hamlet or Three Sisters than a successful Aida or Siegfried. And one reason is equally obvious: finding an actor to play Hamlet or Masha is no problem; finding a dramatic soprano for Aida or a Heldentenor for Siegfried is difficult to impossible.

At the heart of Conrad L. Osborne’s Opera as Opera – the new, self-published mega-book that (as I wrote in The Wall Street Journal) surpasses all previous English-language treatments of opera in performance – is a complex argument exploring the less obvious reasons that theater lives and opera dies. Osborne encapsulates the differences in a single unforgettable sentence: “For a shining moment, opera seized the torch of orality’s failing hand.” That is: grand opera, a nineteenth century genre that flourished for something like a hundred years, grandly retained the rhetoric and gesture of poetry and drama – a grandiloquence of delivery otherwise discarded as artificial.

An actor orating “To be or not to be” has a range of choices: tempo, stress, pitch, articulation are all up for grabs. He can be declamatory or intimate. Not so the tenor singing “Celeste Aida” – it’s all composed into Verdi’s score.

And there is more. Osborne shows that operatic plots cling to a “metanarrative” based on conventions of courtly love that are today as anachronistic as Radames’ outsized way of celebrating his beloved’s attributes “heavenly” and “divine.”

Osborne’s historical perspective drives many of his book’s insights and arguments – including an absolute condemnation of operatic Regietheater. That is: the present-day predilection to re-date or resituate or otherwise alter operatic stories, not to mention the further predilection to deconstruct, casting doubt on composers and characters, in Osborne’s opinion signifies a failure to reckon with the nature of the beast. As theater and opera are not the same thing, he insists, neither is Regietheater in theater and opera one and the same: opera’s distinctive pedigree yields distinctive challenges. He builds his case with such tenacious patience and detail that it at the very least strikes an urgent cautionary note.

If my own perspective on Regietheater is less jaundiced, it’s because my first experience was exemplary. In the summer of 1977, the New York Times sent me to the Bayreuth Festival. It proved a charmed Bayreuth season. I experienced Patrice Chereau’s seminal Ring in its second year – when the irreplaceable Zoltan Kelemen was still singing Alberich (he died in 1979 at the age of 53). I attended Gotz Friedrich’s landmark Tannhauser, noisily premiered in 1972. And I attended the first performance of Harry Kupfer’s still remembered Flying Dutchman. The fourth Bayreuth production that summer, Wolfgang Wagner’s Parsifal, was a bland sequel to the famous abstract stagings of his late brother Wieland; it left no impression whatsoever.

The first thing that amazed me about the work of Chereau, Friedrich, and Kupfer was the acting – better than any I had ever encountered attending opera in New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, or Munich. As for the directorial interpretations and re-interpretations of story and text – they felt wonderfully provocative, thoroughly refreshing. They were also, I would say, a natural emanation of twentieth century European trauma, which dictated new readings of the past. Though the US experienced no such twentieth century debacle as the Great War or Adolf Hitler, Regietheater eventually made the Atlantic crossing, as had serial composition – a comparable case of Old World aesthetic upheaval – some time before.

I remember spending many hours debating the astonishing ways in which Patrice Chereau second-guessed Richard Wagner. He scaled down or contradicted the cycle’s heroic speeches and deeds –beginning with those of Wotan, whose scowling face, stalking gait, and grasping gestures layered his “noblest” utterances with duplicity. Among other things, Chereau’s critique suggested an expose of the Ring itself, of the alleged arrogance and fulsome rhetoric of its creator; he even dressed Wotan as Wagner.

Looking back, however, what I most cherish about that 1977 Ring is not its deconstructive panache. Rather, I most remember Chereau’s human empathy for Loge, Mime, and Alberich – readings precisely comparable to Frank Corsaro’s ingeniously compassionate treatment of Violetta in Verdi’s La traviata at the New York City Opera. Osborne, in Opera as Opera, lovingly recalls “Violetta’s pause”: how in act one Corsaro daringly instructed Patricia Brooks to interpolate an unaccompanied pantomime preceding the expostulation “E strano!” (“How strange!”) and, thereafter, “the most intimate confessions of [Violetta’s] soul.”

If Violetta’s pause permanently transformed Conrad Osborne’s experience of “Ah, fors’e lui,” so it was for me with Mime’s shrug, as interpolated by Chereau and realized by the tenor Heinz Zednik. The Zednik/Chereau Mime was a quick-tempered little Jew, fussy and devious, but never grotesque. Mime’s brief act one narrative of Siegfried’s birth and Sieglinde’s death ends with the words “Sie starb (“she died”). Zednik punctuated this information with a palms’s up shrug – a sudden expression of civilized irony that stabbed the heart. (Go to 22:50 here.)

I will never again encounter anything like Kelemen’s hapless Alberich, in the same Chereau production: a grimy, potbellied opportunist, too weak-headed to keep the ring but abused and angry enough to curse it effectively. In Gotterdammerung, act two, Alberich instructs his son Hagen in evil. Chereau had him bow sheepishly before inquiring “Schafst du [are you asleep?], Hagen, mein Sohn?” Rather than hissing demands, he pled, “Sei Treu!” [be true!] with the anguish of one who knows the game is up, then shuffled slowly and confusedly offstage. Dominated by his futile greed and false hopes, Alberich departed the drama a poignant victim; he acquired tragic stature. (Go to 10:36 here — but this is Hermann Becht, not Kelemen)

Both these moments, I might add, were complemented by Regietheater redatings: Mime’s wire-rim glasses and Alberich’s floppy coat resituated these characters in a drama tracking the sins of Wagner’s own industrial age.

As for the Kupfer Dutchman that Bayreuth summer: he staged it as if fantasized by Senta. (It’s on youtube here.) This hallucination anchored a case study in schizophrenia, replacing Wagner’s legend of redemption through love. Theatrically, the main beneficiaries were Wagner’s blandly sketched secondary characters. Believably portrayed as unwitting perpetrators of Senta’s insanity, Daland and the sailors’ wives took on added significance. As for Erik – rather than a dull-witted plea, his pathetic cavatina became an act of compassion. “Don’t you remember the day we met in the valley, and saw your father leave the shore?” he sang, desperate to yank Senta back to reality. But the narrow expectations of Erik and her father were the problem, not the cure; in panic, she visualized the Dutchman as a defense. The subsequent trio, tugging equally in three directions, was transformed.

Kupfer’s reconception did no favors for the Dutchman himself – I cannot imagine Hans Hotter submitting to enacting this opera’s title role as the figment of a deranged imagination. But Kupfer’s handling of musical content was an astounding coup. The opera’s riper, more chromatic stretches were linked to the vigorously depicted fantasy world of Senta’s mind; the squarer, more diatonic parts were framed by the dull walls of Daland’s house, which collapsed outward whenever Senta lost touch. In the big Senta-Dutchman duet, where Wagner’s stylistic lapses are particularly obvious, Kupfer achieved the same effect by alternating between Senta’s fantasy of the Dutchman and the stolid real-life suitor (not in Wagner’s libretto) that her father provided. Never before had I encountered an operatic staging in which the director’s musical literacy was as apparent or pertinent.

Back in New York, the following season, the Met premiered its first adventure in Wagnerian Regietheater: a Dutchman piloted by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. Ponnelle’s conceit was to recast the story as a nightmare dreamt by Wagner’s slumbering Steersman – a gratuitous revision which led, scenically, to something resembling a high school Halloween party. Even though the Met had Jose van Dam – a far better Dutchman than Bayreuth’s – I remember not a single detail of this mis-production. And the same is true of the Robert Wilson Lohengrin that Osborn skewers for eternity.

Did Ponnelle read music? Does Wilson? I have no idea – but I gleaned no supportive evidence from their Wagner efforts at the Met. And this is one problem with Peter Gelb’s regime. When Rudolf Bing took over in 1950, he imported notable stage directors – Alfred Lunt, Margaret Webster, Peter Brook, Garson Kanin – rather than engaging directors trained in opera. The idea was to blow some fresh air into an old house. How that worked out I do not know. But the results of engaging Robert Lepage to direct the Met Ring on the strength of his prowess for special effects are by now notorious. In act three of Siegfried, Wagner furnishes what may be the most psychologically complex love duet in all opera. In terms of stage action, nothing happens. To choreograph this duet – to block the singers – requires, I would say, detailed comprehension both of text and of musical structure. Lepage simply has Siegfried and Brunnhilde stand and sing. At a loss, he embellishes the duet with the Magic Fire that Wagner has specifically and poetically extinguished in order to create a magical stillness that Lepage cancels.

I’ve had the pleasure of watching Dean Anthony rehearse young singers every summer at the Brevard Music Festival. All four Anthony stagings I’ve encountered there – Sweeney Todd, Rigoletto, Street Scene (cf this blog), Britten’s Midsummer Night’s Dream – have more than worked. The productions were packed with brave directorial details – but they took the form of Violetta’s pause and Mime’s shrug. And they were musically informed.

Dean Anthony came to opera-directing after a distinguished operatic career as a character tenor, assaying a wide variety of repertoire in several languages. He also trained as an actor, dancer, acrobat, and tumbler. (Kupfer and Friedrich were trained to direct opera by Walter Felsenstein — whose influentially revisionist Komische Oper receives a detailed report card from Conrad L. Osborne). That’s a more promising cv, I would say, than directing Broadway musicals or Las Vegas circus spectaculars, however successful.

August 26, 2018

On Rescuing a “Dead Art Form” — A Landmark Book on Opera in Performance

This weekend’s “Wall Street Journal” includes my review of Conrad L. Osborne’s new mega-book “Opera as Opera” — the most important English-language treatment of opera in performance ever written:

During the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, when classical music was a lot more robust than nowadays, High Fidelity was the American magazine of choice for lay connoisseurs and not a few professionals. Its opera expert, Conrad L. Osborne, stood apart. “C.L.O.” was self-evidently a polymath. His knowledge of singing was encyclopedic. He wrote about operas and their socio-cultural underpinnings with a comprehensive authority. As a prose stylist, he challenged comparisons to such quotable American music journalists as James Huneker and Virgil Thomson—yet was a more responsible, more sagacious adjudicator. In fact, his capacity to marry caustic dissidence with an inspiring capacity for empathy and high passion was a rare achievement.

Over the course of the 1980s, High Fidelity gradually disappeared, and so did C.L.O. He devoted his professional life to singing, acting and teaching. He also, in 1987, produced a prodigious comic novel, “O Paradiso,” dissecting the world of operatic performance from the inside out.

Then, a year ago, he suddenly resurfaced as a blogger, at conradlosborne.com—a voice from the past. Incredibly, the seeming éminence grise of High Fidelity was revealed to have been a lad in his 30s. And now, in his 80s, he has produced his magnum opus, Opera as Opera: The State of the Art—788 large, densely printed pages, festooned with footnotes and endnotes. It is, without question, the most important book ever written in English about opera in performance. It is also a cri de coeur, documenting the devastation of a single precinct of Western high culture in modern and postmodern times.

This Olympian judgment takes the form not of a diatribe but of a closely reasoned exegesis. It impugns philistines less than intellectual trend-setters, notably including operatic stage directors (with Robert Wilson’s catatonic Wagner the “last straw”). They are, in Mr. Osborne’s opinion, recklessly intolerant of earlier aesthetic norms, not to mention norms of gender, politics and society. His conviction, painstakingly expounded, is that the past is better served by understanding than by such remedial tinkering as (to cite one recent staging) empowering Carmen to survive the end of Bizet’s opera rather than submitting to José’s knife blade.

That Mr. Osborne has chosen to self-publish Opera as Opera is not really surprising. To begin with, it is several books, complexly intertwined. The subject matter ranges from philosophy and aesthetics to theater and theater history, to the mechanics of the human voice—and some of this material is addressed exclusively to specialists. The pace of exegesis is at all times unhurried; Mr. Osborne is intent on telling us everything. In fact, large chunks of Opera as Opera take the form of a copious diary that most editors would instantly scissor (and, if skilled, better organize).

Mainly, however, Opera as Opera is self-published because the audience for which the author continues to write does not itself continue. Let me offer a sample of what the Osborne perspective on things looks and sounds like: “Over these past five decades, continuing a process already underway, the operatic world has grown more tightly integrated. . . . During this time, the aesthetic ground has also shifted, and has now come set sufficiently to clarify its contours. The hostile takeover is on the books and the stealth candidates are out in the open. Still, nobody who is anybody will quite say so. Performance criticism . . . has been reduced, marginalized, and stuck in a lineup of popcult perpetrators, where it suffers the same woes as the artform on which it fastens. It is by far not enough for devotees to express exasperation and bafflement, or chuck everything into the Eurotrash bin. The dismemberment of opera is being undertaken by some of its most sophisticated, well-educated, and talented practitioners, and while their tongues are often in their cheeks, they don’t seem to know it. . . . Operatic true believers must show not that they don’t understand, but that they understand all too well, and that they have reasons beyond the lazy pleasures of nostalgia for their dismay.”

A useful starting point for absorbing the many-tentacled Osborne argument is the “metanarrative” he extrapolates from the operatic canon. It turns out that nearly all operas coming after Mozart and before Richard Strauss may be said to hew to a single basic story. An outcast male protagonist falls obsessively in love with a forbidden woman who returns his love. The fated couple encounters inflamed opposition. A clash of male claimants ends badly for the lovers. Mr. Osborne is hardly the first to notice that this template, or something like it, encodes dated notions of virile masculinity and divine femininity, but his treatment transcends cant, jargon and ideology more than any other known to me; it is adult. The challenges here posed for 21st-century preservation and revivification in the realm of opera are tackled vehemently, pragmatically and resourcefully.

The challenges ramify, multiply. Appended to the metanarrative is an even more original, more powerful insight. Here Mr. Osborne delves into the history of rhetoric and “orality”—the stuff of the Odyssey and its distant progeny. Relying on other writers, he limns the 19th-century novel as a watershed departure, displacing poetry and drama as the dominant literary mode, “with its tightly controlled narrative, its . . . increasingly antiheroic characters leading increasingly important inner lives, and its cultural saturation via print.” And then—an intellectual coup—he positions 19th-century opera as the apotheosis of the older movement: “For a shining moment,” he writes, opera “seized the torch from orality’s failing hand.” That is: For a century, grand opera rebuffed mistrust of venerable rhetorical traditions otherwise discarded as “artifice.”

With high-toned orality and rhetoric in retreat, a crisis in “great-voiced” singing was self-evidently foreordained. Here Mr. Osborne has a formidable precursor: W.J. Henderson (1855-1937), the most prominent American vocal authority for nearly half a century. Because he started so young and ended so old, Henderson commanded a lofty view of vocal decline. In the Wagner world, he could remember the prodigious Albert Niemann, whom Wagner himself chose to create the role of Siegmund; he reviewed the bewildering advent of Jean de Reszke, legendary in his own time as Tristan and Siegfried; he heard Lauritz Melchior, the Met’s reigning Heldentenor for two decades. Mr. Osborne picks up the thread—he, too, heard Melchior. He also frequently heard Jon Vickers, the last great-voiced Tristan.

Henderson wrote wonderfully about the singing voice. Mr. Osborne is more wonderful still. He can instantly evoke the frisson of Vickers’s idiosyncratic instrument. Why are there no great-voiced Tristans today? Mr. Osborne’s answer, incorporating early recordings not just of singers but of actors in several languages, references microphones and recording studios, changing styles of oratory and everyday speech, an unrefreshed repertoire, and newfangled performance priorities privileging directors’ prerogatives over those of singing actors.

Mr. Osborne dedicates some 34 pages to the decline of operatic conducting and orchestral playing, highlighting James Levine’s recently terminated Metropolitan Opera tenure. How Mr. Levine and his orchestra acquired such a commanding reputation is a question that deserves a book of its own. That Mr. Levine inherited an erratic pit ensemble, and fixed it, is undeniable. But the gifted Met orchestra of today lacks presence, depth of tone, kinetic energy. As Mr. Osborne observes, to encounter Valery Gergiev’s Mariinsky orchestra in the same Metropolitan Opera pit is really all you need to know. I also retain dazzling memories of the throbbing and mellifluous Bolshoi orchestra from its 1975 visit to New York. As for Mr. Levine, the Osborne account cites chapter and verse: He was an opera conductor of high energy and competence who nonetheless failed adequately to articulate musical drama. I would add that the dynamics of harmonic tension-and-release never sufficiently shaped structure, or clinched a Wagner climax, with Mr. Levine in the pit. But never mind.

It must be stressed that Opera as Opera is not a sour pedantic exercise. Mr. Osborne craves emotional surrender. And he lovingly documents exceptions that prove the rule. His fondest memories include a famous New York City Opera production from the 1960s: La Traviata as directed by Frank Corsaro (with whom Mr. Osborne subsequently studied). Corsaro and the soprano Patricia Brooks collaborated on a portrait of Verdi’s Violetta saturated with fresh empathetic detail, including a daringly prolonged pause—dreamy, sinking into reverie—before the expostulation “È strano!” (“How strange!”) just after the party ends in Act One. “This activity took a little over a minute . . . very long for an unaccompanied pantomime inserted between the numbers of a middle-period Verdi opera,” Mr. Osborne writes. “More important than the mundane household activities [receiving a shawl, sitting down on a couch] . . . was the fact that we watched Violetta make a necessary but previously unremarked transition from her social persona to the private, emotionally charged state that generates her long, conflicted solo scene. How could we ever have tolerated the absurdity of Violetta showing out the last of the guests, turning around, taking a breath, and launching into the most intimate confessions of her soul?”

Mr. Osborne finds similar virtues in the singing and acting of the late mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson and of the tenors Neil Shicoff and Jonas Kaufmann. None of these is a great-voiced singer (Mr. Osborne counter-offers Renata Tebaldi and Giovanni Martinelli). Rather, they are singing actors who ingeniously combine a “modern acting sensibility” derived from Konstantin Stanislavski and his legacy, with voices that are balanced, versatile and personal, if never galvanizingly voluminous.

The penultimate chapter of Opera as Opera is a 25-page set piece reviewing one of the Met’s most admired productions of recent seasons: Borodin’s Prince Igor as reconstituted in 2014 by the director Dmitri Tcherniakov. Mr. Osborne: “[It] sold out the house and generated an astoundingly acquiescent critical . . . response of a sort you’d expect from collaborationists greeting an occupying force. . . . That this takedown of a production and sadsack performance should stir not a whiff of dissent, not a scrap of controversy, is a mark of a dead artform.”

Finally, there is an epilogue—“Dream On”—imagining a corrective opera company of the future. It is run by singers after the fashion of certain theatrical cooperatives, of which Chicago’s Steppenwolf is the best-known American example.

Some people will dismiss Opera as Opera (without reading it) as an exercise in deluded nostalgia. Don’t listen to them. Listen instead to the Metropolitan Opera broadcast of Verdi’s Otello on Feb. 12, 1938. The cast includes Giovanni Martinelli, Lawrence Tibbett and Elisabeth Rethberg. The conductor is Ettore Panizza (to my ears, as great as Toscanini). If you prefer Wagner, Exhibit A is Siegfried on Jan. 30, 1937, with Melchior, Friedrich Schorr and Kirsten Flagstad, conducted by Artur Bodanzky. These imperishable readings document standards of singing and operatic orchestral performance unattainable today.

Conrad Osborne flings the gauntlet, relentlessly inquiring: What happened? What to do? It is hardly an exaggeration to suggest that the fate of 21st-century opera partly hinges on the fate of the bristling insights delineated and pondered in this singular mega-book.

[To sample those phenomenal 1937-38 Met broadcasts, go to the “historic recordings” linked to my book Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall: here. For more on Artur Bodanzky’s Wagner, go here. For more on Ettore Panizza, go here and here. For more on James Levine: here. To purchase Opera as Opera, go to conradlosborne.com]

August 17, 2018

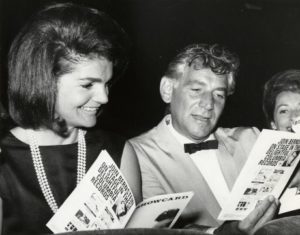

Bernstein at Brevard — Take Two: The Artist and Politics

The Bernstein Centenary celebration at the Brevard Music Festival last month was multi-faceted. I was invited to explore the Bernstein story for a week with Brevard’s exceptional high school orchestra (the festival also hosts college and professional ensembles). The result was the multi-media “Bernstein the Educator” program that I described in my previous blog.

I was also asked to lecture on “Bernstein and Social Justice.” This proved a lot more interesting (and timely) than I had anticipated.

After a few hours’ homework I realized that my topic would be the furious backlash Bernstein endured as a consequence of embracing political and humanitarian causes on the left. His activities became an insane obsession of J. Edgar Hoover. The resulting FBI file of some 800 pages included at least one allegation that Bernstein was a Soviet agent. There was also a trail of dirty tricks, including phony letters delivered to the Bernstein home. In the midst of it all, Bernstein was denied a passport by the US State Department. Two decades after that, he turned up on the Nixon/Haldeman tapes, and on Nixon’s enemies’ list (the antipathy was mutual).

Bernstein’s elder daughter Jamie, in the indispensable memoir just published by HarperCollins (the most vivid and affecting portrait of Leonard Bernstein I’ve ever encountered), cites as a peak Bernstein moment the Beethoven Ninth he led in Berlin when the wall came down in 1989; conducting instrumentalists from two continents, he changed Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” to celebrate “Freiheit” (freedom) rather than “Freude.”

Certainly social justice was a Bernstein leitmotif. Another famous Bernstein performance was of Haydn’s Mass in Time of War at the Washington National Cathedral – an anti-war protest timed to coincide with the Nixon inaugural concert across town. And it’s well-known that his early Broadway work was politically tinged – that On the Town was the first musical to cast a Japanese-American (Sono Osato) as an “all-American girl”; that West Side Story was a compassionate response to gang warfare; that the auto-da-fe in Candide lampooned the Red Scare.

This activity was rooted in the company Bernstein kept as a young musician. His close friends included Marc Blitzstein, arguably America’s foremost political composer, and a member of the Communist Party. Bernstein’s mentor Aaron Copland, as is now increasingly well-known, migrated far to the left in the thirties, addressing a Communist picnic in Minnesota and composing a prize-winning workers’ song espousing revolution.

When his passport was held up in 1953, Bernstein feared being asked under oath if he knew any Communists. His response was an excruciating seven-page affidavit, the whole of which is reprinted in The Leonard Bernstein Letters (2013). He testified:

“Although I have never, to my knowledge, been accused of being a member of the Communist Part, I wish to take advantage of this opportunity to affirm under oath that I am not now nor at any time have ever been a member of the Communist Party. . . I wish to state generally as to all the organizations involved that my connection, if any, with them has been of a most casual and nebulous character. . . . Needless to say I never knew their real character as they were later denominated by the Attorney General of the United States.”

The most chilling sentence is a mea culpa: “I did not possess the requisite suspicion and caution to probe the devious and subversive objectives of those by whom I and too many others were innocently exploited.” Bernstein’s associate Jerome Robbins notoriously named names when subpoenaed in 1953. Bernstein himself was never called.

As for the Nixon tapes: When Bernstein conducted the premiere of his Mass to inaugurate the Kennedy Center in 1971, the FBI surmised “plans of antiwar elements to embarrass the United States Government.” A memo described “a plot by Leonard Bernstein, conductor and composer, to embarrass the President and other Government officials through an antiwar and anti-Government musical composition.” The year before, a Nixon memorandum to Haldeman opined: “As you, of course, know those who are on the modern art and music kick are 95 percent against us anyway. I refer to the recent addicts of Leonard Bernstein and the whole New York crowd. When I compare the horrible monstrosity of Lincoln Center with the Academy of Music in Philadelphia I realize how decadent the modern art and architecture have become. His is what the Kennedy-Shriver crowd believed in and they had every right to encourage this kind of stuff when they were in. But I have no intention whatever of continuing to encourage it now.’’

This fascinating document isn’t paranoid – “95 percent” sounds about right. And I happen to agree with Nixon about the Academy of Music vs. Lincoln Center. But sample this, from Jamie Bernstein’s Famous Father Girl: “On Nixon’s tapes, the president’s voice can be heard reacting to H.R. Haldeman’s description of Bernstein at the curtain call of Mass, kissing the male members of the cast: ‘Absolutely sickening.’ But Daddy was rather proud to have been referred to by President Nixon as ‘a son of a bitch.’”

The elephant in the room, as many readers of this blog will remember, is “radical chic” – the 1970 Black Panther fundraiser at the Bernstein’s Park Avenue apartment. Its hostile misrepresentations in the New York Times and New York Magazine long defined (and lampooned) “Bernstein and social justice.” Charlotte Curtis, the Times’ editor “for women’s and family/style news,” turned up uninvited, as did the late Tom Wolfe. Curtis’s reportage in the Times confrontationally construed a titillating entertainment: “Leonard Bernstein and a Black Panther leader argued the merits of the Black Panther Party’s philosophy before nearly 90 guests at a cocktail party last night in the Bernsteins’ elegant Park Avenue duplex.“

A subsequent Times editorial (!) read in part: “Emergence of the Black Panthers as the romanticized darlings of the politico-cultural jet set is an affront to the majority of . . . those blacks and whites seriously working for complete equality and social justice. It mocked the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr.”

And here’s a tasty morsel from Wolf’s “Radical Chic”:

“Felicia is remarkable. She is beautiful, with that rare burnished beauty that lasts through the years. Her hair is pale blond and set just so. She has a voice that is ‘theatrical,’ to use a term from her youth. She greets the Black panthers with the same blend of the wrist, the same tilt of the head, the same perfect Mary Astor voice with which she greets people like Jason, Adolph, Betty, Gian Carlo, Schuyler, and Goddard . . .

“The very idea of them, these real revolutionaries, who actually put their lives on the line, runs through Lenny’s duplex like a rogue hormone. Everyone casts a glance, or stares, or tries a smile, and then sizes up the house for the somehow delicious counterpoint . . . Deny it if you want to! but one does end up making such sweet furtive comparisons in this season of Radical Chic . . . “

As Jamie Bernstein writes: Felicia Bernstein, through her work with the ACLU, had “agreed to organize and host a fund-raising event to assist the families of twenty-one men in the Black Panther Party who were in jail, with unfairly inflated bail amounts, awaiting trial for what turned out to be trumped-up accusations involving absurd bomb plots around New York City. My mother’s dual purpose was to raise money for a legal defense fund and to help the men’s families stay fed and sheltered until the trial came around. (And when the trial finally did come around, the judge threw the whole case out for being unsubstantiated and patently ridiculous.).” Nearly $10,000 was raised – a substantial sum in 1970 dollars.

Two years after Felicia Bernstein’s death, her husband was quoted as follows in the New York Times (Oct. 22, 1980):

“I have substantial evidence now available to all that the F.B.I. conspired to foment hatred and violent dissension among blacks, among Jews and between blacks and Jews. My late wife and I were among many foils used for his purse, in the context of a so-called “party” for the Panthers in 1970 which was . . . a civil liberties meeting for which my wife had generously offered our apartment. The ensuing FBI-inspired harassment ranged from floods of hate letters sent to me over what are now clearly fictitious signatures, thin-veiled threats couched in anonymous letters to magazines and newspapers, editorial and reportorial diatribes in The New York Times, attempts to injure my long-standing relationship with the people of the state of Israel, plus innumerable other dirty tricks.”

This testimony is nothing compared to that of Jamie, when she writes:

“It’s likely that to this day, Tom Wolfe may not understand the degree to which his snide little piece of neo-journalism rendered him a veritable stooge for the FBI. J. Edgar Hoover himself may well have shed a tear of gratitude that this callow journalist had done so much of the bureau’s work by discrediting left-wing New York Jewish liberals while simultaneously pitting them against the black activist movement . . . Nor may Wolfe truly comprehend the depth of the damage he wreaked on my family. Maybe not so much on my father, who suffered embarrassment but could immerse himself in his various musical activities . . . No, it was my mother who bore the brunt . . .

“After that year, Mummy grew increasingly dejected and discouraged. . . . Four years later, [she] was diagnosed with cancer. Four years after that, she was dead of the disease, at fifty-six. Even now, my rage and disgust can rise up in me like an old fever – and in those nearly deranged moments, it doesn’t seem like such a stretch to lay Mummy’s precipitous decline, and even demise, at the feet of Mr. Wolfe.”

So all of this, and more, punctuated my Brevard talk. I delivered it twice, the first time at the public library. Brevard in the summer is a community, rather like Asheville down the road, packed with retirees from the northeast. I was initially astonished that my revelations were quietly received by a large and attentive audience. When I asked what was going on, I was informed that nothing I reported was in any way surprising. And that is where we are as a nation today.

Next summer’s Brevard theme will be Aaron Copland. Among the programs I will produce will be “Copland and the Cold War” – which I’ve presented elsewhere on many occasions. In addition to music, we’ll see and hear a re-enactment of Copland’s inept grilling by Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn. And we’ll all sing “Into the Streets May First!” – Copland’s workers’ song for The New Masses. Copland, too, was closely watched by the FBI (the switchboard operator at Tanglewood was a hilariously ignorant informant). His backlash experience was as richly embroidered as Bernstein’s – as when vigilant Republicans pulled A Lincoln Portrait from the Eisenhower inaugural.

The back story is that Copland began visiting Mexico in the 1930s, and there enviously discovered a nation in which artists and intellectuals powered social change. His own attempt to become a political artist generated a parable of sorts. It ultimately provoked disapproval and mistrust.

In twentieth century America, artists pursued political causes at their peril. Even JFK, speaking in praise of the artist’s vocation, excoriated political art with scant understanding (I recently wrote a blog about this).

What about today? Very likely we shall have occasion to find out.

August 12, 2018

Bernstein the Educator

Museums curate the past. They help us to shape and populate our impressions of history.

Orchestras do not curate the past. A typical symphonic program (alas) begins with the selection of a soloist. The resulting programs are eclectic: a potpourri.

During his historic music directorship of the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein was the rare conductor for whom curating the past was an urgent priority. During his first season – 1957-58 – he undertook a survey of American music “from its earliest generations to the present.” The resulting programs, sans soloists, started with George Chadwick, Arthur Foote, and Edward MacDowell.

Ever the educator, he turned all that into his second Young People’s Concert: “What Makes Music America?” (Feb. 1, 1958). It’s an essential Bernstein document. You can revisit it on youtube here.

For the Brevard Music Festival’s Bernstein Centenary festival-within-a festival this summer, it was my pleasure to create a young people’s concert about Bernstein’s Feb. 1, 1958, young people’s concert. The musicians were gifted high school students (comprising one of four Brevard orchestras). The conductor and host (also gifted) was Kenneth Lam. I created the script. Peter Bogdanoff created a visual track. You can see and hear what it looked and sounded like here. To sample the gist of it, start at 20:31, where we ask what made Bernstein’s young people’s concerts utterly different from all those that had gone before (the Philharmonic had been doing them since 1924) and answer: “personal need.”

The music for our “Bernstein The Educator” concert derived from the works sampled by Bernstein on “What Makes Music American?” – pieces by Chadwick, George Gershwin, Roy Harris, and Aaron Copland. In Bernstein’s exegesis, they charted an evolutionary ladder from “kindergarten” to “college” and beyond. We added a fifth composer who Bernstein memorably championed – but who doesn’t fit the ladder: Charles Ives.

Hearing the finale of Ives’s Second Symphony (composed long before World War I) alongside An American in Paris, the finale to Harris’s Third, and “Night on the Prairie” from Copland’s Billy the Kid was a terrific experience. I am sure I am far from the only listener who found Ives fresher and more original than the Harris or the Copland. And yet in its day, Roy Harris’s Third (premiered by Serge Koussevitzky’s Boston Symphony in 1939 – a dozen years before Bernstein discovered the Ives Second) was widely considered the foremost contender for “Great American Symphony.”

As for An American in Paris – though Gershwin was once widely perceived as a gifted dilettante, this irresistible tone poem sounds to me exceptionally well put together. As in Rhapsody in Blue and the second movement of his Concerto in F, Gershwin reserves his Big Tune (the languorous song for solo trumpet) for late in the game. And how cunningly he uses it – varying its mood and velocity — to drive his piece to a climax. I would call Harris’s fugal finale clumsy by comparison.

My script ended:

“What are we to make of Bernstein’s ‘evolutionary ladder’ today – more than half a century later? This question is not so simple to answer. The main challenger to Bernstein’s 1958 narrative is Charles Edward Ives, born in Connecticut in 1874. Many would today call Ives the greatest American symphonist. And yet – and this is a problem — Ives’s symphonies did not become well known until long after he composed them.

“Ironically, Charles Ives’s most important advocate among conductors was . . . Leonard Bernstein, who in 1951 introduced the world to a Great American Symphony: Ives’s Symphony No. 2, completed in . . . 1909. Packed with fiddle tunes and hymns, Stephen Foster songs and Civil War marches, Ives’s symphony is a grand American tapestry containing not a single original melody. It’s an act of visionary genius that Serge Koussevitzky didn’t know existed during those interwar decades when he predicted ‘the next Beethoven’ would show up in Colorado.

“Like Koussevitzky, Copland, and countless others, Leonard Bernstein believed that the 1920s and thirties constituted a new dawn for American music – a brave New World without real ancestors. This conviction, and the narrative behind it, was a catalyst. Never mind whether Chadwick was actually a ‘kindergarten’ composer. Never mind that Ives came first. The storied new beginning was energizing, invigorating. It empowered Bernstein to compose, to advocate – and to educate a new generation of American concertgoers.

“But what happens next? We still mainly hear European works in American concert halls. Audiences are aging and dwindling. And when in 1992 Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts were offered to American public television, nothing happened. There was far stronger interest in revisiting these historic shows in Germany and Japan.

“This is a cultural challenge that must matter to all of us. It requires the kind of creative response to a pressing need that once impelled Leonard Bernstein to re-invent the New York Philharmonic.”

I was invited to spend five days with Brevard’s young musicians exploring these questions. Ten of them took part in a vigorous post-concert discussion lasting the better part of an hour. I felt we had managed to concoct a learning exercise worthy of Leonard Bernstein’s high example.

Next summer Brevard will present a Copland festival. I’m working with Jason Posnock, Brevard’s far-sighted artistic administrator, to implement another such young people’s concert — in which the musicians themselves will serve as hosts and commentators. Stay tuned.

August 8, 2018

Furtwangler and the Nazis — Take Two

I am returning to the topic of Furtwangler because my previous blog produced a minor miracle – a thread of responses that yielded heightened understanding of a complex topic.

I wrote to William Osborne and Stephen Stockwell:

“Thanks so much for this engrossing feedback. Maybe we could summarize that the truth about Furtwangler falls within these two polarities:

“1.He stressed the communal experience of music, felt he couldnt access that outside Germanic lands (I find this credible), so he accommodated the Third Reich insofar as he had to, so long as he didnt have to join the Party and otherwise publicly endorse Nazi ideology, ethnic cleansing, book-burning. At the same time, his conservative cultural/political mindset created some degree of common ground with the Nazis. Think of Mann’s superiority posture in Reflections of a Non-Political Man (worth reading if you don’t know it). I cannot envision WF feeling personally kindred to a Hitler or Gobbels; his breeding was aristocratic.

“2.All of the above – but add to that some degree of actual enthusiasm for what the Third Reich stood for – eg concerts that were patriotic occasions, flaunting German exceptionalism/Kunst. Especially given the passions/exigencies of wartime. In other words: crossing the line Mann refused to cross, and doing so with some degree of fervor.”

Both Osborne and Stockwell seem to think this is a useful perspective on an elusive reality.

(Meanwhile, thanks to Norman Lebrecht, a second thread of responses on slippedisc.com tackled another aspect of the Furtwangler phenomenon: his rejection of non-tonal music and its implications for musical interpretation.)

I now feel impelled to revisit Topic A – not Furtwangler the man (B), but Furtwangler the conductor – and see what A and B put together look like today. So I’ve just re-read some of my own Furtwangler writings – from the 1979 New York Times (when I was a Times music critic) and from my most notorious book: Understanding Toscanini (1987).

The basic text for Topic A will always be Wagner’s indispensable booklet “On Conducting” (1869). It may be read as a Furtwangler bible. Everything Wagner here espouses may be found in Furtwangler’s art (and also that of Wagner’s disciple Anton Seidl, the subject of my best book: Wagner Nights: An American History [1994]). I refer to plasticity of tempo, extremes of tempo and dynamics, and other activist strategies rejecting mere adherence to the score. There is also in Wagner, as in Seidl or Furtwangler, an insistence on interiority in the experience and performance of symphonic music.

Whence this interiority? Most obviously: harmonic subcurrents felt, explored, and shaped. This “hidden” foundational content is what the music theorist Heinrich Schenker – paramount for Furtwangler – extrapolated in new ways.

The occasion of my 1979 New York Times piece was the release of a live 1943 performance of Furtwangler conducting Schubert’s C major Symphony. I decided to compare it with his famous studio recording of 1951 to see whether these readings, which seem so impulsive and personal, shared a fundamental groundplan. Here’s what I found:

“The fearless absorption Furtwängler stood for found its most obvious expression in interpolated changes of pulse, both as momentary rubatos and sustained alterations of a basic tempo. . . . In his book, ‘Concerning Music,’ he defined rubato as ‘a temporary relaxation of rhythm under the stress of emotion,’ and went on to say that, without ‘inward veracity,’ any rubato would wind up sounding calculated and exaggerated.

“Though the difference between good rubatos and bad is partly a matter of taste, the mastery of rubato evident in Furtwangler’s best recordings is impressive by any reasonable standard. His Wagner performances, in particular, handle fluctuating tempos in manner that never seems to draw attention to itself. If in his Schubert’s Ninth the tempo changes are more debatable, their clear intention, and frequent result, is to capitalize on the expressive potential of individual moments without losing sight of the whole.

“A couple of comparisons may help clarify the point. If one wishes to investigate the consequences of unbridled subjectivity in this music, there is 1939‐40 recording by Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra that moves in Dionysian fits. . . .

“Toscanini’s 1941 recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, a wonderful performance about as famous as Furtwangler’s, is an entirely different affair from Mengelberg’s. In the outer movements, the steadily pounding rhythms accumulate tremendous force. At the very end of the finale, however, where Schubert has the orchestra hammer out four repeated C’s, Toscanini adopts a much slower speed in order to weight the strokes. With the pulse so rock‐solid everywhere else, such a conspicuous shift sounds doubly conspicuous.

“It so happens that the four‐note figure Toscanini stresses is the same figure that is elongated by Mengelberg’s big ritard at the beginning of the second movement — it is one of the score’s basic ingredients. Furtwangler slows down in both places, but more subtly . . . In fact, the gear‐changes are so slight that, unless you listen for them, only their effects will be apparent: the lyric breadth of the oboe phrase, the extra intensity of the hammer blows. It is not merely that Furtwangler reduces speed less than Mengelberg or Toscanini; by establishing an overall pulse that is firmer than Mengelberg’s, but more plastic than Toscanini’s, he establishes a foil for his rubatos — they are absorbed into the rhythmic flow without disrupting it.

“Not all of Furtwangler’s rubatos are so moderate. In fact, there are places where the change of speed is far more drastic than anything Mengelberg attempts. One example stands out, a spot in the Andante just before the main reprise of the oboe melody. Robert Schumann’s description is nearly as famous as the passage itself: “A horn is calling as from a distance. . . . everything else is hushed, as though listening to some heavenly visitant hovering around the orchestra.”

“It would be impossible to imagine a more rarefied affirmation of Schumann’s imagery than the music Furtwangler conjures up [go to 20:50 here]. . . . the horn, shrouded and remote, speaks as from a void.

“The chief catalyst here is a huge rubato: For a full minute, Furtwangler cuts the pulse by about 90 percent, folding open the space out of which the horn‐call materializes. Such an interpolation would derail any normal performance of a Schubert symphony, yet Furtwangler manages to integrate it. How?

“Partly, he relies on transitions: A massive ritard prepares the horn entry; afterwards, when the horn finishes, the oboe returns with the principle theme slightly under tempo, as if recuperating from a trance. More important, the entire movement is shaped with an ear toward accommodating the interruption. Not only does Furtwangler introduce grand ritards at comparable structural junctures, he anticipates the serenity of the horn‐call passage in the manner he phrases and articulates the second subject, dovetailing its four‐measure phrases into long, lofty spans of 13 and 19 measures. This may not satisfy everybody’s notion of how the movement should go — to most conductors, it is a steadier, more propulsive Andante con moto — but it is a unified approach, and it incorporates breathtaking stretches of repose.

“Throughout the symphony, in fact, Furtwangler’s approach is unified by feats of planning based on long‐range structural divisions and harmonic tensions. It is one of the trademarks of his art that the interpretation sounds spontaneous, even impulsive. To a certain degree, of course, it is. But anyone who doubts the existence of an encompassing master plan might compare the present Schubert’s Ninth with Furtwangler’s 1943 in‐concert recording with the Vienna Philharmonic — though the range of tempos is wider in the 1943 performance, the overall scheme of tempo relationships is the same.”

So that’s what I wrote in 1979 (when such things could be written for a newspaper readership).

And here’s part of what I wrote in 1987 in Understanding Toscanini, undertaking a detailed comparison of Furtwangler and Toscanini in Wagner’s Prelude to Lohengrin:

“From the start, Toscanini has his [NBC Symphony] vocalize the melodic lines. Furtwangler, in his 1954 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, prefers a shimmery, incorporeal sound, with less string vibrato. Toscanini’s tempo, while not hasty, is always distinctly mobile. Furtwangler is much slower (his performance takes 9’50” to Toscanini’s 7’35”) and initially much more relaxed: he makes little of swells Toscanini italicizes, preferring to let the music build cumulatively. Toscanini’s pacing is steadier, with many downbeats perceptibly marked. Furtwangler’s fluid pacing erases Wagner’s bar lines. The downbeats he marks are long-range stresspoints: unlike Toscanini, for instance, he articulates a series of eight-bar phrases beginning with measures 20, 28, and 36. Toscanini accelerates into the prelude’s climax, the whole of which moves at a new, faster tempo. His shiny trumpets, which enter only at this point, dominate the sound [5:20 here]. Furtwangler retards into the climax, the whole of which moves at a new, slower tempo. His trumpets are darker, making the prelude’s crest less sonically distinct [5:58 here]. Postclimax, Toscanini resumes his earlier, slower tempo; Furtwangler, his earlier, faster one. Toscanini retards for the full cadence eight measures from the end. So does Furtwangler, but more drastically – rather than a local event, this unprecedented punctuation point registers the harmonic resolution of the prelude’s entire, arcing span. . . .

“No difference between the two performances is more crucial than the contradictory tempo changes at the climax. Toscanini, sensing one-bar units and relying on surface tension to keep the music whole, holds the line with a relatively tight rein. At moments of peak arousal, he grips harder and speeds up. Furtwangler’s reliance on four-bar units (or multiples thereof) and sustained harmonic tension allows for more play in the line. At moments of peak arousal, he slows down to give the harmonic tensions space in which to expand and resolve. He can also let the line go slack without stopping longterm musical flow; unlike Toscanini’s, Furtwangler’s climaxes pre-empt repose and lead to exhaustion. Their slow, weighted pulse might be likened to that of a pendulum swinging with greater force as it spans ever longer arcs. Their visceral impact bears some relation to the Hollywood convention of shooting moments of crisis or ecstasy in slow motion. Inner turmoil produces a sensation of temporal dislocation. Time ‘slows down,’ even ‘stands still.’ In the Prelude to Lohengrin, Furtwangler’s slow-motion climax seems to exist outside time.” (pp. 364-365)

It’s been a long time since I listened to Furtwangler’s Schubert 9 and I have no particular desire to revisit it in any detail. Beyond a doubt, I would today regard it more as an acquired taste than I did in 1979. In this work, Furtwangler’s antipode is not Toscanini. For me, it is Josef Krips (1902-1974). Krips’ name is today mainly forgotten – but back in the days of High Fidelity LP reviews, his Schubert 9 with the London Symphony was a basic frame of reference. (I remember in 1979 receiving a note from a Times reader advising me to listen to Krips.)

Krips was born in Vienna and I would summarize his art as “Viennese.” He cherished moderation, clarity, and song. His Strauss waltzes are the best I know. His Schubert is gemutlich – Schubertian. The demons Furtwangler discovers in Schubert – I am thinking especially of the astounding Cyclopean intensity of the central climax in the Schubert 9 Andante a la Furtwangler [24:20 here]– are not for Krips. Schubert, assuredly, can be demonic. Furtwangler’s Schubert demons, however, are massive Wagnerian demons.

I would also call Furtwangler an acquired taste in Beethoven’s Ninth (a Bruckner/Wagner reading, unforgettable in the first movement coda). He even has a live recording of Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements wholly un-Stravinskian but (for me) readily acquirable. What I find I cannot acquire a taste for is Furtwangler in Bach, Mozart, or Haydn. And I cannot imagine liking his approach in my favorite Beethoven symphony: No. 8, with its Olympian coda (another intoxicating Krips recording with the London Symphony, once a benchmark).

One thing that’s missing in those Furtwangler readings, and tangible in Krips, is a quality of wholesomeness. Furtwangler’s art – and here we circle back to Topic B – is dangerous. The subcurrents he exhumes are unknowable, inchoate – and uncontrollable. This is the “barbaric” dimension of Romantic art that Thomas Mann extolled and worried about. In the world of conductors, Wilhelm Furtwangler was its last great embodiment.

August 4, 2018

Furtwangler and the Nazis

This weekend’s Wall Street Journal includes my review of Roger Allen’s “Wilhelm Furtwangler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical.” As some readers of this blog may remember, my most controversial and notorious book – “Understanding Toscanini” (1987) – deals rather extensively with the American career of Furtwangler. I also use Wagner’s “Lohengrin” Prelude to illustrate fundamental differences between Furtwangler and Toscanini, showing how Furtwangler uses harmonic structure to shape an “inward” interpretation. Here’s my review:

One of the most thrilling documents of symphonic music in performance—readily accessible on YouTube—is a clip of Wilhelm Furtwängler leading the Berlin Philharmonic in the closing five minutes of Brahms’s Symphony No. 4. Furtwängler is not commanding a performing army. Rather he is channeling a trembling state of heightened emotional awareness so irresistible as to obliterate, in the moment, all previous encounters with the music at hand. This experience is both empowering and—upon reflection—a little scary. And it occurred some three years after the implosion of Hitler’s Third Reich—a regime for which Furtwängler, though not exactly an advocate, was a potent cultural symbol.

In 20th-century classical music, the iconic embodiment of the fight for democratic freedoms was the Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, who fled Europe and galvanized opposition to Hitler and Mussolini. Furtwängler (1886-1954), who remained behind, was Toscanini’s iconic antipode, eschewing the objective clarity of Toscanini’s literalism in favor of Teutonic ideals of lofty subjective spirituality.

Furtwängler was inaccurately denounced in America as a Nazi. His de-Nazification proceedings were misreported in the New York Times. Afterward, he was prevented by a blacklist from conducting the Chicago Symphony or the Metropolitan Opera, both of which wanted him.

Furtwängler was no Nazi. Behind the scenes, he helped Jewish musicians. Before the war ended, he fled Germany for Switzerland. Even so, his insistence on being “nonpolitical” was naive and self-deluded. As a tool of Hitler and Goebbels, he potently abetted the German war effort. In effect, he lent his prestige to the Third Reich whenever he performed, whether in Berlin or abroad. He was also famously photographed shaking hands with Goebbels from the stage.

In “Wilhelm Furtwängler: Art and the Politics of the Unpolitical,” Roger Allen, a fellow at St. Peter’s College, Oxford, doesn’t dwell on any of this. Rather he undertakes a deeper inquiry and asks: Did Furtwängler espouse a characteristically German cultural-philosophical mind-set that in effect embedded Hitler? He answers yes. But the answer is glib.

Mr. Allen’s method is to cull a mountain of Furtwängler writings. That Furtwängler at all times embodied what Thomas Mann in 1945 called “the German-Romantic counter-revolution in intellectual history” is documented beyond question. He was an apostle of Germanic inwardness. He endorsed the philosophical precepts of Hegel and the musical analyses of Heinrich Schenker, for whom German composers mattered most. All this, Mr. Allen shows, propagated notions of “organic” authenticity recapitulated by Nazi ideologues.