Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 27

December 13, 2017

Aida at the Met

When I was a teenager, my mentor in all things operatic was Conrad L. Osborne. I read him religiously in High Fidelity Magazine. I thrilled to his encyclopedic erudition, to his impassioned advocacy, and (not least) to the ruthless thoroughness with which he documented and assessed a devastating decline-and-fall in standards of performance. I never met him, never glimpsed him. I envisioned an eminence gris.

When I was a teenager, my mentor in all things operatic was Conrad L. Osborne. I read him religiously in High Fidelity Magazine. I thrilled to his encyclopedic erudition, to his impassioned advocacy, and (not least) to the ruthless thoroughness with which he documented and assessed a devastating decline-and-fall in standards of performance. I never met him, never glimpsed him. I envisioned an eminence gris.

Low and behold, C. L. O., age 83, now has his own blog. The omniscient graybeard I had envisioned was at the time a young adult in his thirties. After a long silence (he is also the author of a sensationally stylish, hilarious, and acute 1987 opera novel, O Paradiso), he may be read regularly at http://conradlosborne.com/blog/. And he’s about to publish his magnum opus, a mega-book on a topic he rigorously pursued in High Fidelity decades ago, when classical-musical conditions were somewhat less dire than today: the transformation of operatic art into a generic anodyne performance product. He will also have something to say about what to do next.

Osborne’s coruscating take on the new Met Norma begins by dissecting defects in the pit. He writes:

“It is crucial, even in the presence of fine singing, that urgent sounds, sounds that insist on the music’s dramatic significance, emerge from the alliance of pit and podium. The Met’s maestro, Carlo Rizzi, did for this score what he has done for all I’ve heard him conduct—turned it down from a boil to a simmer, and thence to Superlow. There was little sonic presence, except at the biggest moments. The slow accompaniments died, the quicker ones chattered harmlessly along. There was no suspense, no tension, no sense of dramatic construction, not a trace of grandeur.”

My own most recent Metropolitan Opera experience with the standard Italian repertoire was a dormant Aida. I can remember a time when the Met could capably double-cast this grand opera. The cast I encountered was provincial top to bottom. The glamourous trappings – the world-class orchestra and chorus; the fulsome production (live animals) – created a surreal self-contradiction. Without a viable Aida or Radames or Amneris or Amonosro, Aida is reduced to unbearable pomp.

Though I’m old enough, I never heard Leontyne Price or Franco Corelli (my obsession was Wagner). So my point of reference, for Verdi at the Met, is the broadcast recordings of the thirties and forties led by Ettore Panizza. It was once possible to access all these performances on youtube (including La traviata with Rosa Ponselle and Lawrence Tibbett, Tibbett’s Rigoletto and Boccanegra, Jussi Bjoerling and Zinka Milanov in Masked Ball, and – the peak achievement – Giovanni Martinelli’s Otello), but they’re frequently removed. (The Panizza Aida is up right now, as of four months ago; you can listen here. Panizza’s Otello is permanently lodged on the audio site accompanying my Classical Music in America – right here.)

Some months ago, no longer finding my favorite Aida online, I purchased it via amazon. That is: I now own on CD the Feb. 6, 1937, performance conducted by Panizza, with a cast comprising Gina Cigna, Giovanni Martinelli, Bruna Castagna, Carlo Morelli, and Ezio Pinza. I just listened to the whole thing, beginning to end.

Every singer is vocally and dramatically commanding. But the binding imprint of this singular performance resides in the pit. I cannot improve on what I wrote in Classical Music in America. Panizza’s orchestra is an Italian powderkeg surpassing any opera band to be heard today.

“The membership was overwhelmingly Italian, including a few, such as principal oboist Giacomo Del Campo, who had played under Toscanini [at the Met] before World War I. . . . With Toscanini’s departure, the Met’s Italian wing was entrusted to superior leaders: first Tullio Serafin, then Ettore Panizza. The latter (today not even a name), born in Buenos Aires and trained in Milan, from 1921 to 1931 conducted a La Scala, where Toscanini esteemed him (as did Richard Strauss, who arranged for him to conduct Elektra in Vienna). His Met years were 1934-43. Given his extensive European career, which also included Covent Garden, it bears emphasis that he considered that Met’s ‘as fine a theater orchestra as I have seen in the world.’ . . . Compared to Toscanini, he favors a broader play of tempo. But the velocity and precision, the taut filaments of tone, the keen timbres, the clipped, attenuated phrasings are all Toscanini trademarks. Like Toscanini, Panizza will bolt suddenly to the end of a scorching musical sentence; like Toscanini’s, his musicians are lightning respondents. And Panizza is a master of controlling the show while showcasing his cast; calibrating Martinelli’s titanic climaxes and magisterial breadth of phrase, he achieves a unity. Encountering this memento of times past is a humbling experience.”

The live recordings of Maria Callas singing Aida in Mexico City are famous for a reason; no subsequent soprano has made such a wrenching impression in the Nile Scene. But for a complete rendering of this episode – the human heart of Verdi’s opera – Panizza is irreplaceable. No other conductor in my experience deploys such a range of tempo or secures so vital an interpretive template. His wicked accelerandos and lavish cadential ritards are always at the service of the singers and of the drama at hand (no other Radames conveys such confusion and shame as Martinelli does here). Panizza’s razor’s edge balance of abandon and control, vital to Verdi, is actually a lost art.

This recording should be inflicted on all present-day singers, conductors, and (god help us) stage directors attempting Aida. Many would find it revelatory. Too many others simply wouldn’t get it.

December 10, 2017

Music and WW II: Eisler, Schoenberg, Shostakovich, Stravinsky

PostClassical Ensemble inaugurated its new residency at Washington National Cathedral with a World War II program – “Music in Wartime” – juxtaposing works by Hanns Eisler, Arnold Schoenberg, and Dmitri Shostakovich. The results were startling.

Eisler’s strange odyssey is ripe for exploration. In Weimar Germany his workers’ songs linked to a Workers-Singers Union with 400,000 members. Partnering Bertolt Brecht, he became a reckonable political force in support of the Communist Party. Then Hitler chased Eisler and Brecht abroad. Both, incongruously, landed in Los Angeles. Both were expelled and wound up in Communist East Germany, where Eisler wrote the national anthem but nevertheless proved an ideological outcast.

Through it all, Eisler (schooled by Schoenberg) figured out a way to marry leftist politics with a sophisticated musical style. And in LA, with Brecht, he produced a Hollywood Songbook that exquisitely ponders the condition of exile that was his perpetual fate.

At the same moment that Eisler and Brecht finished their Songbook, with its bemused Los Angeles imagery of swimming pools and celluloid spools, Schoenberg in LA composed a furious response to Pearl Harbor: the Ode to Napoleon, whose closing paean to George Washington is Schoenberg’s way of showering gratitude on FDR.

Meanwhile, in Soviet Russia, Shostakovich was processing the Nazi invasion and Siege of Leningrad. PostClassical Ensemble’s “Music in Wartime” program here offered the shattering Piano Trio No. 2 of 1944.

There was a time, not so long ago, when Schoenberg and Shostakovich were positioned as antipodes by Cold War advocates and enemies; you couldn’t endorse them both. But mountains of dust have settled since the sixties – and Schoenberg and Shostakovich are still standing. The Ode to Napoleon and Shostakovich Second Piano Trio are timeless expressions of moral commitment by composers of heroic temperament – artists big enough to calibrate the most momentous world events.

Consider, in contrast, the case of Igor Stravinsky – also in Los Angeles along with Eisler, Brecht, and Schoenberg. His Symphony in Three Movements assays World War II from afar. It is an artistic act of detachment. Privately keying on newsreel images, it absorbs world events with calculated indirection (a topic I have previously explored in this space). A famous anecdote: when apprised that the war might invade the US, Stravinsky’s first reaction was to ask where he could next remove himself in order to get away from it.

Our PCE Pearl Harbor Day concert, then, began with a half-hour Eisler set combining choral political songs from 1928 with solo songs from the Hollywood Songbook. Next came the Shostakovich trio. After intermission, we listened to FDR declare war on Japan (“a day that will live in infamy”). This led, attacca, to Schoenberg’s Ode. More than one hundred people stayed on to talk about it.

Our new home — the National Cathedral — served this music magnificently. The Eisler workers’ choruses were sung in street clothes; the workers marched off, singing, down the aisle of the great nave. The Shostakovich was framed by the towering severity of the vaulted crossing.

The performance of the Trio was the most formidable in my experience. The pianist was Alexander Shtarkman, whose clarion sonorities possess a thrusting edge worthy of Sviatoslav Richter (I write about this astonishing artist in The Ivory Trade). The violinist and cellist were Netanel Draiblate and Benjamin Capps – PCE’s soloistic concertmaster and principal cellist. Michael McCarthy’s Cathedral Choir is a magnificently maintained professional chorus. William Sharp, who sang seven Hollywood songs and was narrator in the Schoenberg, owns these assignments. Angel Gil-Ordonez conducted the Ode to Napoleon with fastidious care and impassioned advocacy. That he considers this work a twentieth century masterpiece was wholly self-evident.

November 18, 2017

Arnold Schoenberg’s Musical Response to FDR

[image error]

What kind of American was Arnold Schoenberg?

In Los Angeles, a Jewish refugee from Hitler’s Germany, he adopted English as his primary language. He watched The Lone Ranger on TV. For his children, he prepared peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches cut into animal shapes.

Then Pearl Harbor was bombed. Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon, in reaction to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s declaration of war on Japan, is one of the most stirring musical responses to a world event ever conceived. It’s the closing work on PostClassical Ensemble’s “Music and Wartime” concert on December 7 – Pearl Harbor Day — at the Washington National Cathedral:

The same PostClassical Ensemble program of music composed during World War II includes Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 2 (1944) and a selection of the Hollywood Songs composed by Hanns Eisler, setting unhappy poems by his fellow Los Angeles refugee Bertolt Brecht.

Eisler had studied with Schoenberg in Vienna after front-line service in World War I. He made his name in Berlin during the 1920s and ‘30s as the preferred composer for workers’ songs – Kampflieder (“songs of struggle”) – linked to a Workers-Singers Union with 400,000 members.

With the coming of Hitler, Eisler fled to the US, where he attempted to help New York City’s Composers’ Collective foster a comparable proletarian song movement enlisting Aaron Copland, among others. This went nowhere and Eisler wound up in Los Angeles. Though he found employment as a film composer, another musical outcome – an expression of estrangement to set beside Schoenberg’s Pearl Harbor patriotism — was the Hollywood Songbook.

Of his American exile, Schoenberg wrote that he “came from one country into another . . . where my head can be erect, where kindness and cheerfulness is dominating, and where to live is a joy and to be an expatriate of another country is the grace of God. . . . I was driven into paradise.”

Meanwhile Eisler was blacklisted and interrogated as the “Karl Marx of Music.” He was conspicuously deported in 1948. His response, also widely reported, read: “I leave this country not without bitterness and infuriation. I could well understand it when in 1933 the Hitler bandits put a price on my head and drove me out. They were the evil of the period; I was proud at being driven out. But I feel heartbroken over being driven out of this beautiful country in this ridiculous way.”

In East Berlin, Eisler composed the national anthem for the German Democratic Republic. Though re-united with Brecht, he discovered himself ideologically suspect all over again. In effect, he is a composer who endured a condition of exile for most of his professional life.

Schoenberg died in Los Angeles in 1951, Eisler in East Berlin in 1962.

October 22, 2017

The Most Under-Rated 20th Century American Composer — Take Two

Back in the thirties and forties, there were no American music historians to tell the story of American classical music. So the task fell to a couple of composers: Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. According to the official Copland/Thomson narrative, noting much of consequence was composed by Americans before World War I. Their focus was on themselves and kindred composers, many of them tutored – like Copland and Thomson – by Nadia Boulanger in France.

This Oedipal view, appointing modernists the inventors of a distinctly American classical music, remains potent today. How I wish it could be retired. Copland and Thomson viewed the two most consequential concert composers ever produced in the US – Charles Ives and George Gershwin – as dilettantes. They were ignorant of the American Dvorak. And even though they both composed for the cinema, they paid no attention to Bernard Herrmann, whom I have previously anointed in this space “the most under-rated 20th century American composer.”

It is about time that the magnitude of Herrmann’s contribution be acknowledged. Working with Orson Welles, Norman Corwin, and Alfred Hitchcock, he was a peerless composer for radio and film. As a radio conductor on CBS, he was a vital advocate of new and unfamiliar works and composers – the antipode to NBC’s Arturo Toscanini. And, notwithstanding advocacy in New York by John Barbirolli and Leopold Stokowski, his measure as a concert composer remains a well-kept secret.

Two years ago PostClassical Ensemble produced the first festival exploring Herrmann “in the round.” We’ve now turned it into a two-hour “PostClassical” WWFM radio feature, archived here at http://wwfm.org/post/postclassical-ce...

Composing for radio dramas (a forgotten genre of high consequence), Herrmann mastered “melodrama” — the art of composing for music and the spoken voice. Our radio show samples “Whitman” (1944), a Corwin/Herrmann radio drama so potent it deserves to be revived by orchestras and actors. It originated as a patriotic wartime vehicle for Charles Laughton. Thanks to a reconstruction by Christopher Husted, PostClassical Ensemble gave the concert premiere as part of our 2015 festival.

Of Herrmann the film composer, PCE presented the DC premiere of his Psycho “symphonic narrative” – an integrated concert work lovingly reconstructed by John Mauceri, and far preferable to the Psycho Suite orchestras still perform by mistake.

Of Herrmann the concert composer, PCE presented the American premiere of the original version of the non-tonal 1936 Sinfonietta for Strings that Herrmann cannibalized for Psycho.

And we performed Herrmann’s chamber music masterpiece: the intoxicating 1967 clarinet quintet Souvenirs de voyage – on our radio show, preceded by pertinent excerpts from his two most intoxicatingly Romantic film scores: Vertigo and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir.

Finally, our “PostClassical” show closes with the sailor’s chorus from Herrmann’s Moby Dick – a spellbinding excerpt that also allows us to sample Herrmann the conductor. Why this 1938 cantata is not performed is an unanswerable question. It would be a stirring vehicle for any Wagnerian bass-baritone interested in adding the towering role of Ahab to Wotan and Amfortas. It would be easy to market. It would ignite a standing ovation.

As ever, our broadcast features unrehearsed needling and jostling between Bill McGlaughlin, Angel Gil-Ordonez, and myself. We listen to the music in real time. We respond spontaneously. It is a fresh adventure every time.

I append a summary with time-code

PART ONE:

5:08: Bernard Herrmann speaks — irascibly

6:33: His daughter Dorothy describes accompanying “Daddy” to Psycho

12:02: Herrmann’s Psycho Symphonic Narrative performed by PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez (DC premiere)

28:30: An influence on Psycho? Bartok’s Divertimento, movement 2

41:10: Herrmann’s Sinfonietta for Strings performed by PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez (American premiere of the original version)

PART TWO:

4:14: Herrmann and radio: the Norman Corwin radio drama “Whitman” (1944) – an excerpt from the original broadcast, with Charles Laughton

14:09: Herrmann and Hollywood: the Love Scene from Vertigo

21:11: The “Liebestod” from The Ghost and Mrs. Muir

26:10: Herrmann’s Clarinet Quintet (Souvenirs de voyage) performed by PCE members

54:33: The Sailors’ Chorus from Herrmann’s cantata Moby Dick, conducted by the composer

September 17, 2017

“The Difference Between Quality Art and Crap” Take Four

Processing my exchange with Vladimir Feltsman, I find myself distracted by something I have long more or less ignored: the art of the piano as manifest by the young artists who today dominate the scene — what Feltsman calls “a new artform.” I am sure my limited purview is unfair. But it’s a sea-change; no previous piano pantheon has so recklessly privileged youth.

So I’ve been binging on the recordings of Rachmaninoff. Re-encountering his 1924 version of Chopin’s Scherzo in C-sharp minor (i.e., a performance recorded when he was 51 and in the throes of a complex exile that compelled him to reinvent himself as a touring concert artist), I am reminded what ripe keyboard artistry sounds like. Instantly, I’m arrested by the second theme: a chorale. Because this pianist has subtly trained his ten fingers as independent operators, he can shade and differentiate the voices at will. This may sound like an esoteric feat, but use your ears from 1:15 to 2:19: the chorale lives and breathes.

As some readers of this blog may dimly remember, I long ago wrote a book titled Conversations with Arrau. I will never forget Claudio Arrau’s sublime performances of Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata – not least for the full textures of the first movement’s chordal second theme. “He voices everything,” a Juilliard piano pedagogue once complained to me. Precisely.

Arrau left a singular 1953 recording of that Chopin C-sharp minor Scherzo. Like Rachmaninoff’s it is not an interpretation for everyone. Rather, it is distinctive in approach, distinctive in sound. It is “quality art.”

I just revisited it on the web – right here. In Conversations with Arrau, I wrote about the passage at 26:55:

“Arrau’s Chopin lacked both the heartiness of [Arthur] Rubinstein and the complex display of [Vladimir] Horowitz. Without inquisitive listening, not only was the scope of Arrau’s interpretations not likely to be received as a virtue, but the detailing—so different from Horowitz’s – was likely to pass unnoticed.

“A case in point is the piu lento section of the C-sharp minor Scherzo, which Arrau charges with mystery. Rather than dramatizing the modulation to the minor with pathetic inflections and smeared pedaling showing the dejection of the filigree, the meaning of the passage is uncovered at a depth. The muted chords are weighted to retain their majesty. The filigree is softened without diluting its poise. The smorzando is underlined by an imperturbably steady ritardando. The effect is of tragedy dissolving, just before the healing surge of the coda, to a searching calm rarely found in Chopin.”

Probably these observations sound terribly recondite (this blog posting feels like an act of recidivism). There used to be an audience for written observations of this kind – and for the commensurate artistry of the deservedly famous pianists so described.

Are there great young pianists? In North America, the irrefutable examples are Glenn Gould and Van Cliburn. If these were instances of the ardor of youth trumping the wisdom of maturity, both satisfied the highest criteria for “quality art.” Gould’s Goldberg Variations recording of 1955, when he was 23, is the singular emanation of a distinctive artistic personality. The same was true of Cliburn’s Rachmaninoff in Moscow, in 1958, when he was 24. And each pianist already commanded a sonic imprint all his own. Notwithstanding the pertinence of the Cold War, Gould and Cliburn were famous for self-sufficient musical reasons, reasons intrinsic to artistry.

September 14, 2017

“The Difference Between Quality Art and Crap” Take Three

Though as usual most of the feedback to my recent blogs comes via private emails rather than public responses, a flurry of interesting posted responses here and via Facebook spurs me to rant some more.

Re: “quality art” versus “crap,” Joe Patrych – someone who knows what pianism once was — writes:

“Part of the problem is the audience – in order for a sophisticated musician such as Moiseiwitsch to be fully understood requires that the audience is properly educated in what constitutes art – the importance of that in Soviet (and post-Soviet) Russia vs. the dismissive approach to arts education in the US is certainly part of the problem, and it takes a lot of work to self-educate; it is clear that most people don’t have the impetus to do so.”

A new book that’s a necessary read is Stalin’s Music Prize: Soviet Culture and Politics by Marina Frolova-Walker. Excavating Soviet archives, she documents the intense private deliberations that considered which Soviet composers, singers, and instrumentalists would be awarded substantial monetary prizes, with their attendant prestige. We eavesdrop on what the composers Shostakovich and Myaskovsky had to say. We also eavesdrop on craven ideologues.

The book begins with some testimony by the actress Vera Maretskaya. She writes:

“In ’46, when I was a delegate to the Congress of Antifascist Women, I happened to speak with an English actress, who had been forbidden to approach our delegation. But she boldly made her way over to us regardless and struck up a conversation with the Soviet women. While she was talking to me about the arts, she couldn’t keep herself from looking downwards, at my chest, and eventually she asked me: ‘What did you get that medal for?’ I told her that it was a medal given to Stalin Prize laureates. ‘For what?’ she asked. ‘For my work in the role of Nadezhkda Durova,’ I replied. . . . ‘What did they give you?’ I asked her. After a moment’s hesitation, she dipped into her handbag and pulled out something drab-looking, small and flat, a kind of powder box. ‘That’s how they reward us performers.’”

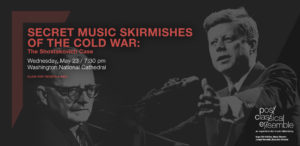

Much could be said about this vignette. Stalin’s Music Prize is certain to be a galvanizing topic when PostClassical Ensemble presents “Secret Music Skirmishes of the Cultural Cold War: The Shostakovich Case” at the Washington National Cathedral on May 23.

P.S.: The most impressive New York audience I’ve encountered in recent seasons was at Town Hall last June for a Russian-language Uncle Vanya presented by Moscow’s Vakhtangov Theatre. That audience was hungry, engaged, and generationally diverse (parents with children). It was also (of course) overwhelmingly Russian.

September 12, 2017

“The Difference Between Quality Art and Crap” Take Two

My exchange with Vladimir Feltsman about “quality art” versus “crap” was posted on youtube and elicited this response:

“Two oldies bemoaning that they have had their day and are confined to the dust bin of history. It is always the no talents that wave their own banner of knowledge as to what is true art.”

Feltsman referenced a performance of Rachmaninoff’s transcription of “The Flight of the Bumblebee” with millions of hits on youtube.

The Romantic piano transcription, as practiced by Rachmaninoff, is a refined art.

Only a worldly performer can do full justice to these pieces. They make their greatest impression when the affect transcends showmanship. This actually requires a higher level of virtuosity.

Here (click) is Yuja Wang performing Rachmaninoff’s transcription of the Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. I am not condemning this highly accomplished rendition as “crap.”

But compare it to Benno Moiseiwitsch – a performance (click) Rachmaninoff himself admired.

Rachmaninoff considered Moiseiwitsch the supreme exponent of his Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. To my ears, Moiseiwitsch’s 1938 recording (click) is unsurpassed. Check out the eighteenth variation (the famous one) at 13:55. I would call that “quality art.”

September 10, 2017

“The Difference Between Quality Art and Crap”

I was chatting with Vladimir Feltsman last Spring about PostClassical Ensemble’s 2017-18 immersion experience, “The Russian Experiment,” when the conversation took an unexpected turn.

I had broached the topic of “cultural community,” and invited Feltsman to compare musical life in the US with the policed Soviet musical milieu he fled in 1987.

We agreed that Western musical life, whatever its virtues, embraced no musical community of culture comparable to what Soviet Russians enjoyed in adversity.

“I’m trying to do what I can to help my younger colleagues,” Feltsman said, referring to the “Piano Summer at New Paltz” festival he founded more than twenty years ago. “In order to be successful, they try to copy the most successful people at the moment in the music business” – people who were not “inspirational characters. . . . We all know their names.”

I recalled a conversation I once had with the pianist Benjamin Pasternack, who is of the same generation as Feltsman and myself. Pasternack and I agreed that there was a time when pianists of international consequence were famous for a reason – but that today it’s become a “crapshoot.”

“It is,” Feltsman agreed. “Absolutely. It’s a different artform. It’s a different market, and we know that the market dictates whatever it needs.”

I requested that our conversation end on a more optimistic note.

So Feltsman added that he hoped “that people, after being satiated with youtube snippets of ‘The Bumblebee’ [millions of hits and counting], would eventually come to understand the difference between quality art and crap.”

This exchange was filmed by Behrouz Jamali, who expertly documents many PostClassical Ensemble events. Behrouz produced a film, “The Russian Experiment: A Different Perspective On Soviet Musical Culture.” “The Difference Between Quality Art and Crap” is an excerpt.

To watch Vladimir Feltsman extol the forgotten Soviet composers of the 1920s, click here. To watch Behrouz’s entire film: here.

Part two of PCE’s “The Russian Experiment” comprises (1) an Oct. 16 concert featuring Vladimir Feltsman and PCE members performing works by Roslavets, Mosolov, and Protopopov (whose Second Piano Sonata is a major find); (2) the Soviet silent film classic The New Babylon with Dmitri Shostakovich’s score performed live on March 30 and 31; and (3) pertinent film screenings at the National Gallery of Art.

For information: postclassical.com

September 8, 2017

The Arts in the Age of Trump (continued)

The Age of Trump has rapidly changed the American cultural landscape in many ways.

In the silo of classical music, there is suddenly a felt need to ask: What’s it for? Why are we doing this?

How can the arts affect social or political change?

How can concerts help us understand who we are as a nation? What we’ve been or want to become?

These questions are newer than they should be. So long as orchestras cling to traditional templates – the generic mixture of concerto and symphony; the mandatory soloist ; the deferent audience – they will rarely be satisfyingly addressed.

Because we program thematically and across the disciplines; because we regularly interface with schools, universities, and museums; because we invariably invite our audience to speak, PostClassical Ensemble has been tackling such questions for some time. And now that we’re Ensemble-in-Residence at the Washington National Cathedral, this exercise will become more concentrated and (we hope) more impactful.

Our new season, for instance, closes with “Secret Music Skirmishes of the Cold War: The Shostakovich Case.” We’ll take a close look at the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom, and how it waged war with Soviet propagandists to capture the hearts and minds of intellectuals on the left in Europe and Latin America. The participants will include Nicholas Dujmovic, former Staff Historian of the CIA, and an actor impersonating President John F. Kennedy. Kennedy’s claim that the arts can only flourish in “free societies” will be juxtaposed with the evidence of piano works composed by Dmitri Shostakovich as performed by a formidable American pianist. We’ll also invite our audience to read a couple of pertinent books: Frances Stonor Saunders’ The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters and Marina Frolova-Walker’s new and revelatory Stalin’s Music Prize. That’s May 23 at the Cathedral.

Our annual PCE “immersion experience” is “The Russian Experiment” — a look at experimental Soviet culture before Stalin. The pertinent events include Vladimir Feltsman performing Mosolov, Roslavets, and Protopopov (whose visionary Piano Sonata No. 2 from 1924 is a major find); and the 1929 classic silent film The New Babylon with Shostakovich’s symphonic score performed live. We’ll want to inquire what this idealistic adventure in political music and cinema amounted to, and why Stalin put an end to it.

Our ongoing “American Roots” initiative explores little-known chapters in the history of African-American music (without which there would be no American music). This season, we focus on Harry Burleigh, who turned spirituals into art songs, and the once famous black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, whose historic visits to the US (facilitated by Burleigh) immersed him in plantation song and its potential for the concert hall. A major theme of these events will be the subsequent bifurcation of American music into classical and popular – white vs. black. How did that happen? What did it cost us?

I append an overview of our 2017-2018 season. For more detail, click here.

Oct. 19 – “The Russian Experiment” with Vladimir Feltsman

Dec. 7 – “Music in Wartime: A Pearl Harbor Day Commemoration”

Feb. 28 – “Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual”

March 30-31 – “The New Babylon” – The Soviet silent film classic with Shostakovich’s score performed live

April 21 – “The Star of Ethiopia”: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Historic Visits to DC (1904-1910)

May 28 – “Secret Musical Skirmishes of the Cold War: The Shostakovich Case”

September 6, 2017

Copland and the Cold War

PostClassical Ensemble’s most recent WWFM “PostClassical” radio show is “Copland and the Cold War” – aired last Friday and now archived.

Our two-hour program includes Aaron Copland’s prize-winning New Masses workers’ song “Into the Streets, May First” as well as a re-enactment of Copland’s 1953 grilling by Senator Joseph McCarthy starring myself and Bill McGlaughlin.

And – sampling one of PostClassical Ensemble’s three Naxos DVDs presenting classic 1930s films with newly recorded soundtracks — we audition and discuss Copland’s least-known important score: his music for the classical 1939 documentary The City. Scripted by Lewis Mumford, this film – far better known to film-makers than to musicians – advocates government-built “new towns.” Its images of happy workers remind my wife – a native of Communist Hungary – of the propaganda films she knew as a child.

How far did Copland migrate to the left in the 1930s? Citing Howard Pollack’s biography, I read a couple of 1934 letters in which Copland excitedly described his participation in Communist Party functions among Minnesota farmers:

“It’s one thing to talk revolution . . . but to preach it from the streets out loud — well, I made my speech and now I’ll never be the same. Now when we go to town, there are friendly nobs from sympathizers. Farmers come up and talk as one red to another. One feels very much at home, not at all like a mere summer boarder.”

This Cold War chapter concludes a fascinating and at times chilling three-part compositional odyssey charted by “the dean of American composers.” He began as a high modernist in 1930 with his lean, hard, and dissonant Piano Variations – a breakthrough in American music. Then, spurred by Mexico and the Depression, he turned himself into a populist and composed the ballets by which we know him best. It was during the beginning of this period that he addressed Communist farmers, scored The City, and won a New Masses contest for the best workers’ song.

These political adventures returned to haunt Copland in the fifties – during which decade he was bluntly interrogated by McCarthy and observed by the FBI (we now know that the switchboard agent at Tanglewood Festival was an informant). His Lincoln Portrait was dropped by from the Eisenhower inauguration following protests from Republicans in Congress who marked him as a former fellow traveler or worse. Copland now turned his back on the “new audience” he had once wooed, returning to his modernist roots in a series of non-tonal compositions beginning with the bleak Piano Quartet of 1950.

The result is a veritable American fable – suggesting, among other things, that the US is less hospitable to political artists than was the Mexico of Diego Rivera, from which Copland drew instruction. Copland’s Mexican colleague Carlos Chavez at various times conducted Mexico’s first permanent orchestra, ran the National Conservatory of Music, and directed the National Institute of Fine Arts.

Looking back at his Mexican visits of the 1930s, and doubtless reflecting upon the American prominence and influence of such outsiders as Arturo Toscanini, Copland said: “I was a little envious of the opportunity composers have to serve their country in a musical way. When one has done that, one can compose with real joy. Here in the U.S. A. we composers have no possibility of directing the musical affairs of the nation – on the contrary, I have the impression that more and more we are working in a vacuum.”

At the close of our two-hour WWFM radio show, the three co-hosts had (as usual) different perspectives on the topic at hand. Quoting Roger Sessions’ quip that “Aaron is a better composer than he thinks he is,” I opined that the Piano Variations were Copland’s highest achievement and that his populism was “synthetic.”

PCE Music Director Angel Gil-Ordonez expressed admiration for Copland’s non-tonal valedictory, the Piano Fantasy (1957). Of the populist Copland, the best Angel could do was “He really tried.”

Bill McGlaughlin was aroused by our remarks to passionately defend the entirety of Copland’s oeuvre. From his perspective, Angel and I fail to appreciate the social and political forces impinging on Aaron Copland’s aesthetic vicissitudes — “So you better get over it, Jack.”

The broadcast draws on two PostClassical Ensemble programs: “Copland and the Cold War” (including “Into the Streets,” the McCarthy re-enactment, and Copland piano works in masterly performances by Benjamin Pasternack); and “The City,” presenting the 1939 film with live orchestra. The musical content of both these concerts are preserved on the Naxos recordings we sampled.

Our previous “PostClassical” broadcasts – all archived – are “Are Orchestras Really ‘Better than Ever?'”, a Lou Harrison Centenary celebration, and “Dvorak and Hiawatha.” Coming up next, on 20: “The Most Under-Rated Twentieth Century American Composer” – a tribute to Bernard Herrmann.

COPLAND AND THE COLD WAR

LISTENING GUIDE

PART I – Copland the modernist turns populist

6:30 – Copland the wild man: Piano Variations (1930), performed by Benjamin Pasternack on Naxos

22:00 – Copland speaks at a Communist picnic in Minnesota (1934)

28:00 – “Into the Streets” (1934), Copland’s prize-winning workers’ song for The New Masses

32:00 – Copland becomes a film composer: The City (1939), espousing government-funded “new towns” with happy workers. From PCE’s Naxos DVD.

52:00 – The famous lunch counter scene from The City, in which Copland prefigures Philip Glass

59:00 — “Sunday Traffic” from The City

PART II – Copland the populist returns to modernism

3:00 – Copland in Hollywood: The Red Pony

11:30 – Copland is interrogated by Senator Joseph McCarthy (1953)

18:00 – Giving up on the “new audience” he once courted, Copland composes a non-tonal valedictory: The Piano Fantasy (1957), performed by Benjamin Pasternack on Naxos

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers