Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 31

August 4, 2015

“Music Unwound” — The NEH and the Music Education Crisis

Processing a terrific performance of Sir Edward Elgar’s Piano Quintet at this summer’s Brevard Music Festival, I found myself pondering both musical and extra-musical paths of engagement. #

Elgar, born in 1857, became Britain’s most famous concert composer, an iconic embodiment of the fin-de-siecle Edwardian moment. From its retrospective relationship to Imperial England, his music derives its singular affect of majesty intermingled with anguished nostalgia. Added to that, the Great War shrouds the Quintet with a poetic veil of mourning. (Elgar’s much performed Cello Concerto, also completed in 1919, is even more elegiacally veiled.) #

The audience at Brevard – one of the nation’s leading summer training-camps for pre-professional classical musicians, in the foothills of North Carolina – mainly comprised young adults new to this piece, probably even to this composer. They were ardently attentive, effusively appreciative. I asked myself how many of them knew “Edwardian England” – or the Great War, or Queen Victoria. What cultural content, outside music, could they bring to a first hearing of Elgar’s quintet? I would venture to guess: little or none. #

There are many manifestations of the current crisis in music education. Some derive from accelerated cultural change, which makes canonized symphonies, plays, novels, and paintings ever more remote. In classical music, the crisis is acute because the canon is closed — the mainstream repertoire for orchestras and opera companies ends well over half a century ago with Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Britten. #

Among America’s music schools and festivals, Brevard is unusual for crafting a targeted response. With the support of the National Endowment of the Humanities, next summer’s festival will incorporate a cross-disciplinary festival-within-a-festival: “Dvorak and America.” All the collegiate musicians performing Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony will read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha – which happens to be a pertinent point of reference for this most popular symphony ever composed on American soil. Even conductors who assay “From the New World” do not realize that – as Dvorak testified – the middle movements are inspired by episodes from Longfellow’s once-famous narrative poem – that the Scherzo sets “Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast,” and the Largo re-experiences Minnehaha’s death in shivering winter. #

At Brevard’s performance of the “New World” Symphony next July, these movements will be accompanied by a “visual presentation” incorporating excerpts from Longfellow’s poem (a core specimen of the American experience) and paintings by nineteenth century Americans, including the important “Indianists” George Catlin and Karl Bodmer. And a “Hiawatha Melodrama” combining verses by Longfellow with music by Dvorak will be performed in tandem with the symphony. #

The purpose of this exercise is to launch an inquiry into the question: “What does music mean?” It is the same question I asked myself about Elgar’s quintet. It has no correct answer. But the question is invaluable, I believe, if fledgling classical musicians, reconnecting with masterworks of centuries past, are to maintain a living relationship with the legacy they inherit. #

When “Music Unwound” was initiated in 2010 with a $300,000 NEH grant, it was a consortium of professional orchestras — the Pacific Symphony, the North Carolina Symphony, the Louisville Orchestra, and the Buffalo Philharmonic — committed to undertaking thematic festivals on two topics: “Dvorak and America” and “Copland and Mexico.” A secondary component was institutional collaboration: the four recipients were challenged to link with high schools, museums, and – especially – colleges and universities. As director of “Music Unwound,” I frankly imagined that these relationships would at best materialize slowly and fitfully. I did not foresee that the project would rapidly evolve to target students. #

In addition to five professional orchestras, the current “Music Unwound” participants include the Brevard Festival, Chapman University, and the University of Texas in El Paso. It has unexpectedly become an experiment in infusing Humanities instruction. #

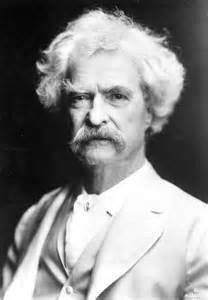

At Chapman – a small liberal arts college in Orange County, California – “Music Unwound” is driven by a visionary chancellor — Daniele Struppa — who believes that allying with a major professional orchestra is a necessary strategy for introducing undergraduates to symphonic music. When next February the Pacific Symphony produces a “Music Unwound” celebration of Charles Ives, Chapman students will be invited to explore what Ives and Mark Twain have in common. The premise of his exercise will be that what Huckleberry Finn is to the American novel, Ives Symphony No. 2 (1909) is to the American symphony: a landmark achievement in transforming a hallowed Old World genre through recourse to New World vernacular speech and song. #

At the University of Texas, “Music Unwound” is driven by a visionary Mexican-American music historian — Frank Candelaria — to whom collaboration with the El Paso Symphony seems a necessary opportunity to introduce high school and college students to the Mexican Revolution and its formidable composers and painters. #

If “Music Unwound” is renewed for a third funding cycle, the consortium will expand to include the DePauw University School of Music, where a visionary dean — Mark McCoy — is attempting to re-invent conservatory education. One part of this new template is a new way of teaching Music History – not as a sequence of Great Composers, but as a Sociology of Music privileging institutional history and cultural circumstance. #

Dvorak would open a window on Longfellow and Catlin. Ives would connect to Mark Twain, to Emerson and Thoreau. Elgar would register the passing of Empire and the trauma of unprecedented “world war.” These topics need one another. Their binding synergies can no longer be assumed. #

(For more on “Music Unwound,” see my postings of March 31, 2011; Feb. 23, March 20, May 20, and June, 11, 2012; and May 1, 2015.) #

May 1, 2015

Charles Ives and Huck Finn

“Music Unwound” is an orchestral consortium supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. It funds contextualized symphonic programs in collaboration with colleges and universities. To date, two topics have been in play. “Dvorak and America” explores the quest for American cultural identity ca. 1900; the central work is Dvorak’s New World Symphony, supplemented by a “visual presentation” aligning the music with Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha and the canvases of Frederick Church, George Catlin, and Frederic Remington. “Copland and Mexico” explores Aaron Copland’s Mexican epiphany of the 1930s; the central work is the iconic Mexican film Redes (1935), with Silvestre Revueltas’s terrific score performed live. #

Music Unwound” is now commencing a second funding cycle with the addition of “Charles Ives’s America” — which debuted in Buffalo three weeks ago and included two Buffalo Philharmonic subscription concerts plus half a dozen ancillary events at a museum, a library, and a university. The central work was Ives’s Symphony No. 2 (1900-1909) – an irresistible Great American Symphony only premiered in 1951 when Leonard Bernstein rescued it from oblivion for a national New York Philharmonic radio audience. #

That notwithstanding Bernstein’s impassioned launch, Ives’s Second Symphony never entered the mainstream symphonic repertoire records a discouraging lack of advocacy. It has simply not been performed sufficiently to acquire the audience it deserves. As a result, orchestras resist programming Ives’ Second because it doesn’t sell tickets – a vicious circle perpetuating the stereotype of Ives as a cranky composer of “difficult” music. The “Music Unwound” program – which tells the Ives story with a 30-minute visual track – is a necessary attempt to win audiences over to our most important symphonist. #

Central to the presentation was a performance by baritone William Sharp (a peerless singer of Ives) of the hymns and songs that generate Ives’s symphonic motifs. These range from the inane college song “Where Oh Where Are the Verdant Freshmen?”, which Ives whimsically appropriates as a lovely sonata-form second subject, to Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe,” which in Ives’s Civil War finale signifies compassion for the slave. #

These twin aspects of Ives’s Second Symphony – the exuberance with which it subverts a hallowed European genre with American vernacular strains; the poignancy with which it connects to slavery and race – resonate mightily with Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, which Ernest Hemingway famously called the starting point of American literature. What Huck Finn is to the American novel, Ives’s Second is to the American symphony. And the moral epiphany of Twain’s novel – the scene on the raft in which Huck humbles himself before the human being in Jim – parallels Ives’s compassion for the African-American, a legacy inherited from his Abolitionist grandparents. #

Twain’s rambunctious sense of humor, thumbing his nose at European cultural parents with pretended innocence, is also Ivesian – as when in the Second Symphony a Bach fugue must contend with “Camptown Races,” and Stephen Foster comes out on top. (I write about Ives and Mark Twain in the least-known, least-read of my ten books: Moral Fire: Musical Portraits from America’s Fin-de-Siecle.) #

The “Music Unwound” Ives program will next be presented by the Pacific Symphony in Spring 2016. William Sharp will again participate. The central university partner will be Chapman University. The possibilities for cross-disciplinary inquiry are limitless. #

Some day, Charles Ives – who knew Mark Twain; who identified with the Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau — will take his rightful place in the American cultural pantheon alongside such equally self-made Americans as Twain, Emerson, and Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Hermann Melville. Were Ives a writer or painter, this would have happened long ago. But American cultural historians ignore classical music, and American orchestras remain chronically Eurocentric. #

April 22, 2015

Prokofiev’s Happy Ending, and Further Thoughts on Conducting Ballet

In 1936 Sergei Prokofiev decided to move with his family to Stalin’s Soviet Union. He had first returned to Russia in 1927 and had written in his diary: “It’s a shame to part from the USSR. The goal of the trip was obtained: I have certainly, definitely become stronger.” Subsequent visits were also fortifying. In Europe, he had felt his creative gift atrophy. He discovered that he needed to compose on Russian soil. #

Though the Soviets had coaxed him with prospective commissions and performances, and with promises that he could continue to travel abroad, in 1936 they issued an ultimatum: unless Prokofiev relocated to Russia, he would no longer be permitted in Russia at all. So Prokofiev took up residence in Moscow knowing a thing or two about Soviet conditions. He also knew that he would never be allowed to leave with his wife and children. As it happened, he last left Soviet Russia in 1938. He died there in 1953, the same day as Stalin, at the age of 61. #

In the West, Prokofiev had competed with Stravinsky as a modernist. Works like the Fifth Piano Concerto (1932) attempted a complex, non-traditional idiom. In the Soviet Union, he embraced a “new simplicity” connecting to “the people.” It was the same conscious reorientation that Aaron Copland undertook in the US, a move from modernism to populism, a response to changing social and political conditions. #

An early product of Prokofiev’s “new simplicity” was the ballet Romeo and Juliet. He finished composing it in 1935. But in Soviet Russia composers were subject to aesthetic dictates and to peer-review committees. Not until 1940 was Romeo and Juliet as know it premiered in Leningrad. In the intervening four years, the head of the Bolshoi Theater had been executed as an “enemy of the people.” This delayed production of Prokofiev’s ballet, as did various objections to the scenario and to the music. #

The most intriguing of these objections was to Prokofiev’s “happy ending.” Prokofiev did not wish the lovers to die. Publicly, he explained that “the dead cannot dance.” Also, the director Sergey Radlov argued for a Socialist Realist ending updating the story as “a play about the struggle for the right to love by young, strong, and progressive people battling against feudal traditions and feudal outlooks on marriage and family.” But there can be little doubt that Prokofiev’s adherence to Christian Science was a crucial factor. #

He had become a Christian Scientist in France. For him, the body was illusory, the spirit (transcending death) eternally real. And so Prokofiev’s Romeo witnessed Juliet awakening from the effects of Friar Laurence’s potion. The ballet was to end with Romeo bearing Juliet “into a grove,” where she slowly revived. Meanwhile, a gathering of people observed the lovers. Romeo and Juliet “express their feelings of relief and joy in a final dance.” A quiet apotheosis came last. #

Prokofiev’s own account of what next happened to his ballet reads: “Curiously enough whereas the report that Prokofiev was writing a ballet on the theme of Romeo and Juliet with a happy ending was received quite calmly in London, our own Shakespeare scholars proved more papal than the pope and rushed to the defense of Shakespeare. . . . After several conferences with the choreographers it was found tat the tragic ending could be expressed in dance and in due course the music for that ending was written.” #

Whatever one makes of the changes imposed on Prokofiev’s ballet (including bravura moments for the dancers), the result was an international triumph – and an ending quite literally recapitulating Shakespeare. #

Not until decades later did the music historian Simon Morrison (whose 2009 book The People’s Artist: Prokofiev’s Soviet Years discloses the story I here recount) discover that Prokofiev’s initial “happy ending” survived. It has since been performed several times in the US, most recently by the Pacific Symphony last week in Orange County, California. It has not (to my knowledge) been recorded. #

The discarded happy ending is fully 15 minutes long – substantially longer than the revised ending we know. Some of the music is the same. But unique to the happy ending is the passage of public excitement – an Allegro moderato that years later became the scherzo of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony. The apotheosis (Andantino), beginning with a sublime pizzicato passage, is also much different from anything in the Romeo and Juliet we normally see and hear. Prokofiev’s discarded happy ending is not a mere novelty – it remains a beautiful and viable alternative. #

The Pacific Symphony’s performances – of a one-hour mini-production of Prokofiev’s ballet — incorporated two dancers and two actors. The actors were Romeo and Juliet in old age, reminiscing. The dancers (compassionately choreographed by Lorin Johnson) were their younger selves. This ingenious concept was the brainchild of Carl St. Clair, the orchestra’s music director. It fell to me to write the script, combining Shakespeare with such faux Shakespeare as: #

ROMEO:

But family feuds are not so readily ’scaped

As by mere lovers wishéd dreams.

Tybalt, thy fiery distempered cous’,

Did my bosom mate Mercutio slay

When I would forestall their bloody duel.

So I in turn my rash weapon drew

And in my own anger raging Tybalt slew. #

St. Clair’s affinity for this Prokofiev score is distinctive – he reads it with maximum emotional and musical weight. The addition of the happy ending was seamless. A fade to black silhouetted the paired Romeos and Juliets. This presentation deserves future performances – as does the happy ending itself. #

A footnote: No less than Valery Gergiev’s recent performances of Prokofiev’s Cinderella with his Mariinsky Ballet at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, St. Clair’s Romeo – with its portentous tempos and massive rallentandos — illustrates what can happen when a conductor leads rather than follows the dancers. Like the happy ending, this is a trade-off worth pondering, a risk worth attempting. #

When I shared this blog in draft with Lorin Johnson, he wrote back: #

“You ask about the dancers. Since we had rehearsed the choreography to recorded music that was faster, they needed to completely reevaluate how to use the space. They never became frustrated with the challenge, but instead found ways to ‘fill out’ moments in time that had been of shorter duration in rehearsal. Actually, when I came to Sunday’s final performance, I was amazed at the level of nuance they portrayed on stage. The choreography had taken on new life, and they had very much ‘found themselves’ within both movements and music. I feel I saw the chemistry of Carl/orchestra/dance come together in this final show.” #

Surely a dynamic, dialectic interaction of music and dance is what best serves the big ballets of Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev. #

January 22, 2015

What Are Ballet Conductors For?

What is the function of the conductor in ballet performance? Never in my (limited) experience has this question been more provocatively posed than during the Mariinsky Ballet’s recent residency at BAM. This is because two of ballet’s most stirring symphonic scores – Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake and Prokofiev’s Cinderella – were purveyed in the pit by a world-class orchestra under the leadership of a master conductor. The orchestra was the same great Mariinsky band that next performs Prokofiev and Shostakovich at Carnegie Hall. The conductor was Valery Gergiev, who now presides over the big Mariinsky ballets as he does when the Mariinsky gives the operas of Mussorgsky or the concertos of Rachmaninoff or the symphonies of Mahler. #

Gergiev’s Swan Lake is a distinguished musical achievement, but his Cinderella is something else: unique and unforgettable. His St. Petersburg orchestra has the most distinctive symphonic sonority to be heard today. Its dark textures and fullness of tone are what the Prokofiev ballets crave; a disturbing claustrophobic intensity – surely Stalinist in provenance – is composed into these scores (think of how Cinderella begins). And Gergiev secures, as well, an unflagging tidal impetus. The big waltz, the clock scene (progeny of Boris Godunov) are propelled with an elemental energy. #

Over at American Ballet Theatre, the Prokofiev ballets sound thinner and more generic. They aren’t as quick, the tempos are steadier, the colors and dynamics are everywhere more neutral. Above all, they defer to the dancers. Gergiev commandeers the stage as he would conducting opera. It bears mentioning, as well, that the Mariinsky supplied some 75 players in the BAM pit, whereas ABT fields a substantially smaller instrumental complement in a house (that of the Metropolitan Opera) twice as large. Another thing: there is no stopping for applause during the Gergiev Cinderella: the musical statement preserves its integrity. #

I am aware of the complaints that Gergiev’s tempos are inconsiderately quick, that he tramples the dancers’ prerogatives. And what about the music’s prerogatives? When Hans Knappertsbusch conducted the Ring at Bayreuth in the 1950s and ‘60s, his slow tempos made the singers audibly uncomfortable. But Knappertsbusch remained a popular and undeflectable fixture, because those tempos secured a magisterial template that fed the whole. I cannot believe that the Mariinsky dancers don’t benefit from the potency of a significant musical reading, whatever the rigors it imposes. #

In any event, hearing such a Cinderella emanating from a theater pit is a new experience – and not only in New York. In Russia too (I am reliably told), there is no precedent for concert conductors of international stature regularly leading ballet. #

When Prokofiev endowed Cinderella with a score of the highest distinction, he surely intended a Gesamtkunstwerk, not another Paquita or Don Quixote. I am no informed judge of the dancing and choreography (by Alexei Ratmansky) of the Mariinsky Cinderella performances at BAM. But it seemed to me on January 20 that the dancers held their own with the music, and that the result was bigger than the sum of its parts. #

November 9, 2014

Can a Music School Be Re-Invented?

There is a powerful consensus that music schools and conservatories have to rethink the education of 21st century musicians, but no one, so far as I know, has implemented a new template. This is what Mark McCoy is up to at the DePauw University School of Music. He calls it the “21st-Century Musician Initiative” and it isn’t window dressing. #

My own harangues on this topic have long focused on two necessary educational opportunities: #

1.It is high time that Music History be reconfigured to include the history of musical institutions and of music in performance (as in my own Classical Music in America: A History, which I shamelessly recommend as a state-of-the-art textbook). That way, the basic questions are front and center: What is a concert for? What is music for? Why be a musician? #

2.Conservatories and schools of music should regularly self-present cross-disciplinary festivals with resonant themes. That way, some more basic questions are pushed into play: What is a concert? What does it have to do with anything outside music? #

DePauw’s two-week “Dvorak and America” festival, which concluded last weekend, incorporated four concerts, each of which found its own idiosyncratic format. All were hosted by students who created their own commentary. Three included visual elements. One was fully scripted. The DePauw orchestra, wind ensemble, chorus, chamber musicians, and pianists all took part. So did a members of the English and Athletic Departments. The topics included “Dvorak and the Indianists Movement,” “Dvorak and ‘Negro Melodies,’” and the New World Symphony. The composers, additional to Dvorak, included Gottschalk, Joplin, Harry Burleigh, Arthur Farwell (his amazing eight-part a cappella Indianist choruses), Charles Wakefield Cadman, and Art Tatum. #

Meanwhile, in the classroom and concert hall, there were related master classes, coachings, workshops, lecture-performances, and visitors. Because McCoy has the entire student body (totaling 160) meet en masse every Wednesday morning, I was able to inflict myself on everyone at once (week one), and to partner Kevin Deas (a peerless exponent of spirituals) in a “Harry Burleigh show” (week two) exploring how Dvorak’s African-American assistant took plantation songs into the concert hall. Many students (including every member of the orchestra) read The Song of Hiawatha (because it inspired Dvorak). Quite a few read Classical Music in America. #

The festival worked because DePauw is small enough to implement a consolidated learning/teaching experience, and because Mark McCoy is strong enough to inspire and cajole maximum participation. The inspirational lessons Dvorak once taught us seemed powerfully absorbed. Dvorak’s three-year American sojourn, during which he pursued a mandate to help Americans find their own voice in the concert hall, illuminates what music is about. Even more important, it illuminates what music is for: how it can help people and nations perceive and understand themselves. #

About three-quarters of the way through, Mark began to wonder out loud what might have happened had Dvorak not returned to Prague in 1895. This departure was not preordained. It resulted from the Panic of 1893, which decimated the resources of Jeannette Thurber. She was the educational visionary who had enticed Dvorak to preside over her National Conservatory of Music in New York. Dvorak died at 62 in Prague in 1904. He had talked of retiring to Spillville, Iowa, where he had composed his American Quartet, American Quintet, and Violin Sonatina in the wake of composing the New World Symphony in Manhattan. His prodigious American output also included the Cello Concerto, the G-flat Humoresque (the one we all know), and American Suite (the topic of my most recent Wall Street Journal article). #

That the American Suite sounds “American” is something I regularly demonstrate as part of my standard rant about the history of classical music in America, how it ran off the rails, and what to do about it. Dvorak would doubtless have continued to explore his American style had he remained in America. Also, he was keen to compose a Hiawatha opera or cantata. So that, too, would have happened but for the 1893 Wall Street collapse. Even his short stay fundamentally influenced Burleigh, Amy Beach, and George Chadwick (whose Jubilee is prime Americana – every American orchestra should perform it). #

Here are three more what-ifs:

1.What if Mahler hadn’t died in 1911 at the age of 50 and had instead remained at the helm of the New York Philharmonic? It is said he had taken an interest in Charles Ives’s Symphony No. 3.

2.What if Charles Griffes hadn’t died at the age of 35 in 1919 – just after composing his scorching and original Piano Sonata?

3.What if Gershwin hadn’t died at the age of 38 in 1936? What might have been the progeny of Porgy and Bess? #

The way things transpired instead, a too-heavy burden was placed on the shoulders of Aaron Copland, a gifted second-tier composer who undertook in the twenties and thirties to jump-start an American classical music infused with a French modernist aesthetic. So far as Copland was concerned (and also Thomson, Bernstein, and many others), there was nothing much in place to work with. Gottschalk, Dvorak, Ives, Joplin, Chadwick, Griffes were all invisible to them. But these pre-1920 composers would have become unignorable if Dvorak had stuck around another half dozen years. #

If this is a pipe-dream, Mark McCoy’s reinvention of the DePauw School of Music may be the real deal. Beginning next fall, “State of the Art” will become mandatory for all sophomores. This course – as I discovered – takes a hard and informed look at classical music in America and how it got that way (the instructor, the cellist Eric Edberg, has long espoused and taught Improvisation at DePauw). “Entrepreneurship” will become mandatory for all juniors. (Yes, I know that is now a music-education buzzword and in itself means nothing.) Every senior will have to invent a “project” — something less generic than a recital or thesis. The sequence will be supported by an agenda of composer and ensemble residencies crafted to push everyone beyond the traditional boundaries of classical music. #

That this is a genuine experiment I have no doubt. #

October 4, 2014

“The Chasm Between Doing Music and Thinking About It”

The most resonant sentence in Robert Freeman’s highly quotable new book The Crisis of Classical Music in America reads: “It is my own strong conviction that, in the years ahead, music will need all the help we can give her. To my way of thinking, that means the development of collegiate musicians who are dedicated at least as much to the future of music as they as are to the unfolding of their own careers.” #

Freeman’s own career – presiding over the Eastman School, the New England Conservatory, and the Butler School of Music at the University of Texas/Austin – has at all times targeted the “future of music.” His book – subtitled “Lessons from a Life in the Education of Musicians” — is unignorable for anyone invested in the musical education of young Americans. #

Another resonant Freeman formulation is “the chasm between doing music and thinking about it.” I have myself been pondering that chasm, and trying to do something about it, for as long as I have been producing concerts and writing books. But I had to think twice when I read, in Freeman’s book, what Archibald Davison, long the chairman of Music at Harvard, had to say about it in 1926: #

“It is sometimes urged that there is an analogy between the type of ability required in the manipulation of apparatus used in the physical lab in preparation of entrance examinations, and the merely mechanical business of playing the pianoforte, for example. This is hardly true, for the ability to handle skillfully laboratory instruments presupposes the use of logic or original thinking in the experiments that are to follow, whereas playing the pianoforte may be a purely physical matte in which the intellect plays a relatively small part.” #

Freeman comments: “However misguided such a philosophy may be from the perspective of any thoughtful modern musician, the original design for the study of music in the United States perpetuated the European split between doing music and thinking about it. . . . Theory and practice, isolated from one another, needlessly fracture not only music’s integrity as a discipline but the possibility of its broader influence in America.” #

When I entered Swarthmore College in 1965, the Davison distinction was firmly in place: no credit was offered for playing a musical instrument – or for acting in a play, or for creating a painting or a poem. Then the college inched forward under the guidance of a committee charged with rethinking the curriculum. I remember being asked by a distinguished member of the English faculty why musical performance should become curricular. His governing assumption was that only an “intellectual” component of this activity would validate it as credit-bearing. My answer was weak – something about the cerebral dimension of translating notes into sounds. #

I now recognize what seems obvious: that making music importantly hones a range of human capacities – intellectual, emotional, experiential. In any event, Swarthmore proceeded to grudgingly offer a quarter-credit per semester for preparing and performing chamber music under professional supervision. As a participating pianist, I was assigned Copland’s Sextet for piano, clarinet, and string quartet. The coach was Paul Zukofsky, who told us that we were tackling one of the most difficult pieces in the chamber repertoire. I remember learning and performing it (not very well). I equally remember that, beyond listening to Copland’s own recording, I failed utterly to “think about it.” Notwithstanding our motivating quarter-credit, the fascinating history of this piece (which began as a symphony), and the composer’s complex odyssey as a modernist turned populist, remained equally unknown to me and my fellow chamber musicians. #

How much has changed? I could cite many experiences with gifted young instrumentalists who learn the notes of a symphony or sonata without “thinking about it.” #

At today’s music conservatories, the need for formidable change is pervasive, but formidable change is not. It is, however, coming. An experiment of which I am aware – and which Freeman mentions in his book – is taking place at DePauw University, where Mark McCoy is intent upon re-inventing the School of Music. At DePauw’s upcoming “Dvorak and America” festival, the participating orchestra musicians will be required to read a book. (I wonder if there is a precedent.) The symphony in question is Dvorak’s “New World” and the book is Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha, which as followers of this blog know figures fundamentally in the Largo and Scherzo. There will also be a rehearsal at which the pertinence of this information in pondered. #

Does the knowledge that Dvorak was inspired by the Dance of Pau-Puk-Keewis change the way we perform or hear the opening of the Scherzo? There is no right answer. But the question itself is a pertinent one if the chasm Freeman documents is to be broached. Nor is this question irrelevant to the concert experience and “the future of music.” More than before, more than ever, musicians must not only ask themselves what it’s about, but what it’s for. #

September 21, 2014

On the Future of the Metropolitan Opera (continued)

Reviewing a new history of the Metropolitan Opera in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, I write: “The Met has never enjoyed the services of a shrewd and practical visionary. There is no one in the company’s annals to set beside Henry Higginson, who created the Boston Symphony in 1881; or Oscar Hammerstein, whose Manhattan Opera combined integrated musical theater, new repertoire and stellar artists before being bought out by the Met in 1910; or George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein, who invented the New York City Ballet in 1948; or Harvey Lichtenstein, who reinvented the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the 1980s.” #

To read the review, google: wall street journal affron metropolitan opera book review #

Also, if you were not able to access my recent Wall Street Journal Op-Ed on the Met, in which I opined that the 4,000-seat Metropolitan Opera House is “already a relic,” google: wall street journal joseph horowitz metropolitan opera union trouble #

Common to both pieces is the notion that “grand opera” as a defining variant of the operatic experience is increasingly a thing of the past. Like the “culture of performance” and the “performance specialist,” it will ultimately be viewed as a twentieth century anomaly. Opera in America will increasingly transpire in smaller spaces, prioritizing an intimate theatrical experience. #

August 8, 2014

The Elephant in the Room at the Met Opera Negotiations

According to my Op-Ed in today’s Wall Street Journal, the Metropolitan Opera House — physically and metaphorically — signifies a notion of “grand opera” that is increasingly unsustainable. #

To read the rest: http://online.wsj.com/articles/joseph... #

August 5, 2014

Dvorak’s America

The current Times Literary Supplement (UK) features my latest rant on Dvorak as an American composer, as follows: #

Earlier this summer, Ivan Fischer came to New York with his Budapest Festival Orchestra to offer two memorable concerts of music by Antonin Dvorak. The repertoire included Dvorak’s last two symphonies: no. 8 in G major, and no. 9 in E minor (“From the New World”). On the web, Fischer commented in a filmed English-language interview: “[Dvorak] came out of the nineteenth century patriotic emotional group of composers. And at that time, one has to stress, being in love with your country had nothing negative — it wasn’t like the nationalism of a later period. Dvorak the absolute lover of Bohemia gives us an insight into East European culture – the feeling people had at the time – like nobody else.” #

To a New Yorker, Fischer’s statement seemed chiefly notable for two omissions. The first, conveyed loudly but implicitly, was of something Hungarian: that Dvorak, the benign nationalist, rebukes the combative nationalism of Hungary’s governing Fidesz party, which Fischer opposes. The second omission was of something American. Fischer overlooks an understanding I take for granted: that Dvorak’s Ninth has more to say about New World than Old World identity – an understanding that bears on the nature of patriotic sentiment in music generally. #

When Fischer mentions “the nationalism of a later period,” he could of course equally have had in mind Hitler or Mussolini or Stalin: all music-lovers. Also relevant, from a much earlier period, is Plato’s anxiety about the capacity of music to stir mass sentiment. Certainly in Dvorak’s time – the late nineteenth century – musical nationalism was not invariably wholesome. #

In late nineteenth century America, the central authority on music and race was the New York music critic Henry Edward Krehbiel. Krehbiel wrote about American music, Czech music, Hungarian music, all kinds of music. And he admired it all – including Jewish music. He also wrote (in 1914) the first book-length treatment of African-American folk song, in which he chastised “one class of critics” for “their ungenerous and illiberal attitude” toward black Americans. Krehbiel’s allies in New York included a visionary music educator: Jeannette Thurber, who in 1892 lured Dvorak from Prague to head her National Conservatory of Music. Thurber’s conservatory admitted all black students on full scholarship. She wanted them around because she was convinced of the power of “plantation song” to stir constructive national feeling. When Thurber handed Dvorak a mandate to help found an “American school” of composition, Dvorak fixed on the African-American and Native-American as representative embodiments of “America.” Krehbiel supported and championed this endeavor. One result was the “New World” Symphony. #

From the moment of its premiere at Carnegie Hall on December 16, 1893, Dvorak’s symphony was both influential and controversial in America. The question asked and re-asked was: “Is it American?” New York said yes. But the music critic Philips Hale, a central arbiter of Boston taste, denounced Dvorak as a “negrophile.” For Boston, “America” meant the Mayflower. New York, by comparison, was a melting pot. New York critics admired in the “New World” Symphony a plethora of “black” and “red” allusions. The third theme of the first movement and the Largo’s English horn tune seemed self-evidently inspired by African-American song. (The former practically quotes “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The latter was transformed after Dvorak’s death into “Goin’ Home” – an ersatz spiritual so pervasive that to this day many Americans assume it is a slave song quoted by Dvorak.) Dvorak’s absorption of Native American music and lore was also noted – not least because Dvorak himself told members of the New York press that the middle movements of his new symphony were inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855), in 1893 still the best-known, most-read work of American literature. #

In a tour de force of musical journalism, the New York Times’ W. J. Henderson – a close colleague of Krehbiel – filed a 2,000-word review that remains one of the most eloquent descriptions of the “New World” Symphony ever written, one which clinches the twin pathos of the Indian and the slave as polyvalently conveyed by Dvorak. Henderson called the Largo “an idealized slave song made to fit the impressive quiet of night on the prairie. When the star of empire took its way over those mighty Western plains blood and sweat and agony and bleaching human bones marked its course. Something of this awful buried sorrow of the prairie must have forced itself upon Dr. Dvorak’s mind.” Of “the plantation songs of the negro” — songs which inspired Dvorak as they had “struck an answering note in the American heart” – Henderson had clarion words: “If those songs are not national, then there is no such thing as national music.” #

But in decades to follow, this first reception of the “New World” Symphony was forgotten. The symphony was canonized as a Slavic masterpiece whose sadness conveyed “Heimweh” – homesickness for Bohemia. In 1966, Leonard Bernstein (for whom an “American school” began only with Copland) preposterously claimed that Dvorak’s Largo “with Chinese words could sound Chinese.” A program note by Michael Beckerman for Ivan Fischer’s “New World” Symphony performance concluded differently: “Some have argued that there is nothing American about the work, that Dvorak could have just as easily written the work at home. They are wrong.” #

And they are. America’ s leading Dvorak scholar, Beckerman has tirelessly excavated the intimate relationship binding the “New World” Symphony with “The Song of Hiawatha.” Dvorak testified that the beginning of his Scherzo – the symphony’s third movement – was inspired by the scene “in which the Indians dance” in Longfellow’s narrative poem. There is only one such scene: it is “Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast.” The wedding dancer, Pau-Puk-Keewis, begins by “treading softly like a panther,” then whirls, stomps, and spins “eddying round and round the wigwam,/till the leaves went whirling with him,/like great snowdrifts o’er the landscape.” This idealized, mythic mega-dance is the hurtling main theme of Dvorak’s scherzo, with its incessant tom tom and exotic drone, and the “primitive” five-note compass of its skittish tune. Never mind that real Indian dances don’t sound like this. Dvorak saw and heard dancing Indians in Manhattan and in Iowa. He knew Krehbiel’s specimens of Indian song. He was not attempting to retain the flavor of indigenous music – as Bartok would, and as would Arthur Farwell in the wake of Dvorak (about which more in a moment). The other main events of the Wedding Feast are the gentle song of Chibiabos and a legend told by Iagoo. As Beckerman as incontrovertibly demonstrated, Dvorak builds these episodes, too, into his Scherzo. It is a de facto Hiawatha tone poem. #

Beckerman has also tracked down evidence that Dvorak’s Largo – in addition to evoking prairie desolation, which Dvorak found “sad to despair”; in addition to evoking the sorrow songs of the plantation – drew inspiration from the death in winter of Hiawatha’s wife, Minnehaha. This is the funereal passage with pizzicato double basses and piercing violin tremolos, shuddering with the chill of Longfellow’s “long and dreary winter” – a threnody of the most exquisite poignancy. The very end of the symphony comprises another dirge (with timpani taps), then an apotheosis, then – a conductor’s nightmare – a dying final chord requiring the winds to diminish to triple-piano. Although Beckerman does not here propose a Hiawatha correlation, this coda is plainly extra-musical: it requires a story. The story at hand fits: it is Hiawatha’s leavetaking, sailing “into the fiery sunset,” into “the purple mists of evening.” #

Last spring, Beckerman and I completed a 35-minute “Hiawatha Melodrama” for narrator and orchestra (in musical parlance, a “melodrama” mates music with the spoken word). It can be heard on a new “Dvorak and America” Naxos CD. Combining passages from “The Song of Hiawatha” with excerpts from the “New World” Symphony, it maximizes the symphony’s programmatic content. It glimpses the unrealized “Hiawatha” opera or cantata that was Dvorak’s crowning ambition during his American sojourn. “From the New World” was a step in this direction. It is not itself a “Hiawatha” program symphony: the Hiawatha episodes are not in proper sequence. And “Hiawatha” is a sporadic presence, not ubiquitous. Rather, this last Dvorak symphony transitions to the folkloric tone poems he would compose upon returning to Prague: pieces in which every detail tells a story as well-known to his Bohemian audience as “The Song of Hiawatha” was known to Americans. #

Though listening to such late Dvorak tone poems as “The Wood Dove” or “The Golden Spinning Wheel” without reference to the Karel Erben ballads that they set (in some passages, word for word) would be a perverse experience, the knowledge that Dvorak’s Scherzo was inspired by the Dance of Pau-Puk-Keewis does not require that we hear it as an Indian dance. That said, the “Hiawatha” elements of Dvorak’s symphony remain an essential point of reference. They support the epic, elegiac splendor of the work, which begins with a sorrow song in the low strings and ends with an apotheosis of pain. Obviously, Dvorak’s sadness of the prairie and sadness of the Indian and sadness of the slave resonate with homeward longings (and with who knows that other personal sadnesses). My own experience of “From the New World” is of a reading of America drawn taut, emotionally, by the pull of the Czech fatherland.

And there are other reasons to attend to Dvorak’s “Hiawatha” references. They tell us something important about Dvorak the man, and about musical meaning. #

The most startling confession in Igor Stravinsky’s many conversations with Robert Craft is that his Symphony in Three Movements (1945) aligns with pictorial imagery. Although commissioned by the New York Philharmonic as a World War II victory opus, the Symphony is widely considered a prototypically abstract neo-classical exercise affirming Stravinsky’s notorious credo that music can only be about itself. “Certain specific events excited my musical imagination,” Stravinsky told Craft. “Each episode is linked in my mind with a concrete impression of the war, almost always cinematographic in origin. For instance, the beginning of the third movement is partly a musical reaction to newsreels I had seen of goose-stepping soldiers. The square march beat, the brass-band instrumentation, the grotesque crescendo in the tuba – all these are related to those repellant pictures.” Stravinsky went on to furnish a scenario for the entire six-minute finale. But he concluded: “In spite of what I have admitted, the symphony is not programmatic. Composers combine notes. That is all.” #

Though his most recent biographer, Stephen Walsh, dismisses the pertinence of Stravinsky’s “supposed” testimony to Craft concerning the martial imagery informing the Symphony’s outer movements, Stravinsky’s pictorial narrative for the finale works splendidly – I happen to know, because (with the video artist Peter Bogdanoff, for California’s Pacific Symphony) I’ve tried it out, with actual World War II newsreel clips. And though Stravinsky’s distinction between “programmatic” music and music inspired by “specific events” may sound sophistic, it is not: he was sharing workshop secrets with Craft. #

If even Stravinsky, the modernist scourge of extra-musical meanings, privately resorted to extra-musical inspiration, what about the composers who came before? Their workshops were crammed with pictures – even for symphonies. Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s amanuensis, testified that Beethoven typically relied upon scenery and events to – we can use Stravinsky’s phrase – “excite his musical imagination.” Dvorak is an extreme case. His ten Legends – three of which Ivan Fischer conducted in New York with exemplary creative flair – are plainly miniature tone poems. The slow movement of the G major Symphony – which Fischer delivered with a revelatory precision of narrative detail – obviously tells a story. I have no idea what characters and plots Fischer may adduce in these pieces – because Dvorak, characteristically, left no clues That he conceded that “Hiawatha” impregnated the “From the New World” may well have been a begrudging response to New York’s importunate critics, who were at the same time – unlike their European brethren – proactive daily journalists. Krehbiel, in particular, was granted a “New World” Symphony audience in Dvorak’s study that he later recalled as one of the supreme satisfactions of his professional career. Dvorak was coy, and said different things to different New York interrogators. But the net confessional was substantial. We are not left in the dark, as with the Legends, the G major Symphony, and countless other Dvorak essays in musical description. We can actually identify the Hiawaha stories he used as a creative spur. Even the pay-off is extra-musical. #

Dvorak was a village butcher’s son. He drank beer. He loved birds and kept some, uncaged, in his Manhattan apartment. He wrote to the New York Herald: “It is to the poor that I turn for musical greatness. The poor work hard; they study seriously. . . . If in my own career I have achieved a measure of success and reward it is to some extent due to the fact I was the son of poor parents and was reared in any atmosphere of struggle and endeavour.” As a Bohemian, Dvorak proudly belonged to a Hapsburg minority experienced in the rigors of marginalization. He refused to move to Vienna or to change his first name to “Anton.” The resisted polishing his German. In America, Dvorak identified with the disenfranchised. The 1890s were not remote from the memory of slavery. The extinction of the red man was a living reality; turn-of-the-century Americans widely believed that he would vanish completely. Dvorak’s African-American assistant, Harry Burleigh, was the grandson of a slave who bought his freedom, who learned to read, who sent his daughter to college; Dvorak knew this saga intimately. Though not a gregarious type, Dvorak in Iowa daily conversed with the members of the Kickapoo Medicine Show. If the “New World” remains the most beloved symphony composed on American soil, it is partly because as listeners we sense, however subliminally, Dvorak’s compassionate experience of black and “red” Americans. He was not an easy or uncomplicated man. His National Conservatory students often found him daunting and irascible. But the artist in Dvorak was defined by personal humility, sympathetic understanding, and democratic instinct – qualities that set him apart from such contemporaneous symphonists as Tchaikovsky, Brahms, and Bruckner. What the “New World” Symphony ultimately imparts is that its composer was a great humanitarian. #

Dvorak’s American legacy remains ponderable. The twin sources for an “American school” that he proposed yielded twin prophecies. He told the New York Herald that “Negro melodies” would foster “a great and noble school of music.” He also espoused a future American music inspired by the Native American. If the second of these predictions proved false, Dvorak was nonetheless a central promulgator of a four-decade “Indianist” movement in American music. And if hundreds of Indianist songs, symphonies, and operas amassed a mountain of kitsch, there is as well some buried treasure. Arthur Farwell, who declared himself the first American composer to “take up Dvorak’s challenge,” was impelled by the “New World” Symphony to found a Wa-Wan Press for himself and fellow Indianists. At his best – in the Navajo War Dance No. 2 for solo piano (1904); in “Pawnee Horses” for eight-part a cappella chorus in Navajo (1937) — Farwell is the closest thing to an American Bartok, honoring the astringency of indigenous sources. This is a truncated Dvorak legacy that deserves to be remembered. #

The “Negro melodies” Dvorak championed of course more than endure: he correctly foresaw a black American musical future. Though it has taken many directions, one is specific to Dvorak and to Harry Burleigh. It was Burleigh, after Dvorak’s death, who transformed plantation song into a genre of art song. Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson sang Burleigh’s version of “Deep River.” It is sung even now. In Burleigh’s lifetime, “Deep River” (not “Swing Low”) was the iconic spiritual, a grave hymn of inspiration and hope. This was a compositional achievement: an earlier “Deep River,” sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, was relatively upbeat. #

What inspired Burleigh to recast “Deep River”? Could it have been Dvorak’s Largo, so similar in tone and tempo? Among the versions of “Deep River” that Burleigh crafted, there is one for a cappella male chorus. Its chordal preamble cites the brass chorale with which Dvorak prefaces his English horn tune. We can actually say that this great American folk-song, as known today, would not exist without the influence of a symphony composed by a visiting Bohemian. I cannot imagine a purer example of musical nationalism as a wholesome force. #

July 17, 2014

Remembering Artur Bodanzky

Sony’s 25-CD set “Wagner at the Met: Legendary Performances” reminds us that when the Metropolitan Opera was a great Wagner house — how times have changed! — it was also a permanent home to great conductors. My “Remembering Artur Bodanzky,” in the current issue of Barry Millington’s excellent Wagner Journal, expounds: #

An abundance of evidence – written and recorded – suggests that from 1885 to 1939 the world’s foremost Wagner house, judged solely by the caliber of musical performance, was the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. In Europe, there were companies that staged Wagner more painstakingly or progressively. But none could compete with the Met with regard to singing, conducting, and orchestral support. #

The caliber of Wagner singing in New York during the half century in question is a phenomenon well known and much described. Initially, the resident German ensemble included Marianne Brandt, Lilli Lehmann, and Albert Niemann – great singing actors stolen from German companies. Later, Jean de Rezske – who proved that Tristan could be beautifully vocalized — and Olive Fremstad – the closest equivalent to a Wagnerian Callas – reigned at the Met. After that came Friedrich Schorr, Lauritz Melchior, Kirsten Flagstad. This was before the advent of air travel; these artists stayed put in New York. #

But even more crucial – and far less acknowledged – is that the Met was a conductor’s house with a Wagner lineage comprising Anton Seidl, Gustav Mahler, Arturo Toscanini, and Artur Bodanzky. That Bodanzky is not normally grouped in such company is the reason for this article. His Wagner broadcast recordings were once sidelined by commercial studio products. No longer: you can readily hear Bodanzky’s Wagner on youtube, on Naxos, and on a new 25-CD Sony box of “Wagner at the Met: Legendary Performances from The Metropolitan Opera” including New York Bodanzky performances of Siegfried (Jan. 30, 1937), Tristan und Isolde (April 16, 1938), and Götterdämmerung (Jan. 11, 1936). All you have to do is listen. #

But first, backing up: it must be remembered that, following an inaugural season of Italian and French opera that broke the bank, the Met began as a German-language house. The seven seasons from 1884 to 1891 were wholly German; it was the only language sung, and the vast majority of the singing was of Wagner. As of 1885, the presiding conductor, Anton Seidl, was a Wagner protégé of genius. That from 1872 to 1878 Seidl lived at Wahnfried – in his own room, as a virtual member of the family — has somehow escaped Wagner biographers. He was Wagner’s boy, and when Wagner sent him out into the world he testified that Seidl was a young man he wholly trusted to do justice to the Ring, Tristan, and Die Meistersinger. All accounts of Seidl conducting Wagner register his close allegiance to Wagner’s own precepts – and his overwhelming impact in the pit. #

When Mahler became the Met’s chief purveyer of Wagner in 1908, that he was found worthy of comparison with Seidl was the highest possible praise. Compared to Seidl, Mahler seemed more analytical, less prone to the weight and Innigkeit later associated with Furtwängler. Mahler and his wife were amazed by the lustrous voices at the Met, compared what Mahler had in Vienna. That Mahler did not complain about the Met orchestra (as he did about the New York Philharmonic and New York Symphony) speaks volumes. #

Toscanini’s Wagner at the Met, from 1908 to 1915, was at first less highly regarded – but his intense mastery and advocacy were never in doubt. Toscanini’s Wagner sound was found more Italianate than that of his predecessors, and his lyric predilection – for “singing” sonic surfaces – was experienced as something new in the Wagner repertoire. #

And so to Bodanzky. He was born in Vienna in 1877. He studied composition with Alexander von Zemlinsky. He was an assistant to Mahler at the Vienna Opera, and was also closely associated with Busoni (who recommended him to Toscanini when Toscanini left New York in 1915). He was head of the German wing at the Met from 1915 until his death in 1939. The Mahler and Busoni links are suggestive. Bodanzky’s Met broadcasts do not disclose a “Germanic” Wagner conductor in the Wagner-Seidl-Furtwängler mold. The massive elemental groundswell is not his interpretive medium. Rather, he favors the highest possible surface intensity. He likes brisk tempos, subito dynamics, and sharp attacks. More than responsive, his orchestra is indescribably hot. James Huneker – a legendary name among early twentieth century New York critics — wrote: “No living conductor has the fiery temperament of Bodanzky save Arturo Toscanini.” #

It bears stressing that Bodanzky’s Met orchestra was predominantly Italian – a Toscanini legacy. The house’s other principal conductor, presiding over the Italian wing, was Ettore Panizza – a name as forgotten as Bodanzky’s, and as important. Panizza was a conductor in the Toscanini mold, albeit predisposed to a more flexible pulse. To hear his Met broadcasts of Verdi is to hear both Panizza and the Met orchestra in their element. There is no greater recorded operatic performance than Panizza’s New York Otello of Feb. 12, 1938, with Giovanni Martinelli, Elisabeth Rethberg, and Lawrence Tibbett. Martinelli and Tibbett are iconic in their roles. And the orchestra is a powderkeg of inflammatory virtuosity, an instrument unlike any to be heard today. (Panizza, who had conducted in Milan and Vienna, called his Met orchestra “as fine a theater orchestra as I have seen in the world.”) The same orchestra, in the 1938 Tristan under Bodanzky’s baton, delivers the most gripping act one Prelude I have ever experienced (I am not alone in this opinion). The sound is Italian: keenly focused singing from the strings, laced with portamento; forward timpani and brass (bright trumpets). Bodanzky begins very slowly (the total timing is 11:38 – slow), with huge allargandos and agogics, but there is no languor in his reading. It begins burning hot, and in an iron grip grows hotter still. The gradual acceleration is masterfully gauged. The climax is titanic – even a good performance of the opera could only be anti-climactic after such a draining preamble. #

But the Bodanzky performance to hear first is Siegfried. This is not only the most fulfilling recorded performance of this opera that I know; it is the only musically fulfilling Siegfried I have ever encountered. To begin with, the scherzando métier of acts one and two suits Bodanzky to perfection. And, of course, there is Melchior – he can sing the title role, first to last. The young Flagstad makes her own the sunburst of Brünnhilde’s awakening. Schorr has always seemed to me a somewhat stolid singer – but where today can one find a Wanderer of comparable vocal heft and stability? The others – Mime (Karl Laufkötter), Alberich (Eduard Habich), Erda (Kerstin Thorborg), even the Forest Bird (Stella Andreva) – are uniformly potent. The diction throughout is exemplary; words are sung, not swallowed. #

Bodanzky’s act one is predominantly fleet. Mime and Siegfried scamper in time, prodded by hairtrigger accents and sforzatos in the pit. Where Siegfried assimilates his mother’s death, Bodanzky drops his reins and Melchior trims his big tenor to a whisper, shading the words with pangs of incredulous grief. When the last scene is attained, the pacing of the act acquires an unanticipated breadth. Buttressed by the incredible rasp and bite of Bodanzky’s low strings, Melchior just pours it on. I cannot imagine a more exultant rendition of the forging song. In act two, Bodanzky’s intermittent climaxes – the crest of the Wanderer/Alberich confrontation; the Wanderer’s apocalyptic exit – are so tremendous they risk pre-empting the act’s closing surge. But when this comes, Bodanzky’s velocity (the passage cannot be taken any faster or more brilliantly) and Melchior’s vocal refulgence clinch Siegfried’s delight and excitement. The surpassing moment of this performance, however, is unquestionably Brünnhilde’s Awakening. Here, the surging melos of Bodanzky’s strings drives a climax made uncanny by the knife-thrust of the epochal chords preceding “Heil dir, Sonne!” – chords typically delivered via “soft” attacks from the bottom up. Then Flagstad: a lava flow. And then Melchior. Bodanzky accelerates their duet toward a torrential cadence. #

If Bodanzky is mainly remembered for anything these days, it is for inflicting cuts on Wagner. It must be recalled that Wagner was abridged in New York even by Seidl – or, rather, especially by Seidl, because he was a sensitive, sensible man: the works were new and most in the audience knew no German. (Mahler, by comparison, aspired to give Wagner uncut in New York – thinking of himself and the composer, but not of his audience.) Bodanzky trimmed Wagner not because he was lazy or obtuse; he was being considerate to others. That said, the Bodanzky’s cuts are far less extensive than Seidl’s had been. His Siegfried is uncut through acts one and two. The third act is missing part of the Siegfried-Wanderer scene, and part of the final duet – cuts that truncate the psychological trajectory of the latter scene especially. #

With regard to cuts, the Bodanzky Tristan is another case; the score is jettisoned by 13 per cent. Act one is complete. But the second act duet is snipped twice – so that it builds too soon. Marke’s speech is abridged – so that it becomes more eruptive, less depressive. Act three, with four cuts, feels compressed – and so does the opera as a whole. And yet this broadcast recording is an essential point of reference in the history of Wagner in performance. Others will disagree, but to my ears Flagstad is not a complete Isolde. The richness, evenness, and stamina of her Ur-soprano are unsurpassable; and the part has been assiduously studied. But she cannot really inhabit Isolde’s act one rage, scorn, and hopelessness. It falls to Bodanzky to supply the music’s whipping fury; the temper and virtuosity of his big orchestra, its agility at the swiftest speeds, are beyond praise. #

The performance congeals in act two, with Flagstad partnered by Melchior. Here the sheer amplitude of the two voices, the rapturous range and acute control of phrasing and dynamics (impressively captured on Sony’s transfer) beggar description. The singing portamentos of the orchestra’s strings seamlessly bind the vocal episodes. Bondanzky finds the long line of the love duet and makes it wondrously supple and strong. For Brangäne’s warning, he furnishes a sonic carpet whose slow-motion tension-and-release trajectory grips Karin Branzell as surely as it does the afternoon’s enthralled auditors. The duet’s climax takes possession of every participant; I have never heard a more desperate delivery of Kurwenal’s “Rette dich, Tristan!” than that of Julius Huehn on this charged occasion. In short: this Tristan act two documents an ideal toward which present-day performances cannot plausibly aspire. If I were to cite a single, peak passage, it would be Tristan’s “O König.” Melchior’s uncanny rendering of this great address – first to Marke, then Isolde – persuades that he has glimpsed what we cannot. It would take a Fremstad or Lilli Lehmann to craft a suitably visionary rejoinder; Flagstad isn’t up to it. But, miraculously, the Met has supplied a Melot – Arnold Gabor – who can stand his ground with Melchior, and also, in Emanuel List, a superior Marke. Bodanzky’s band drops the curtain with a staccato fury that knows no answer. #

Wagner once instructed Albert Niemann – the supreme Tristan of another era – to sound more fatigued singing Tannhäuser’s Rome Narrative. As the comatose Tristan in act three of our 1938 broadcast, Melchior evinces an elemental weariness. Equally convincing are the shouted, curdled tones with which he curses the lovers’ fatal drink; or the heartbreak of his hallucinatory yearning; or the manic ecstasy yielding the manic dissolution with which Tristan expires. In the Liebestod, Flagstad’s super-human instrument, piloted by Bodanzky’s heaving orchestra, impacts with primordial force. #

Bodanzky’ 1936 Götterdämmerung is chiefly notable for Melchior’s piercing interpretation of Siegfried’s Death and for his prodigious high C earlier in the third act; the performance as a whole feels hyper-active (but then so is this opera). More remarkable – but not in Sony’s box – are Bodanzky Met broadcasts of Das Rheingold and Die Meistersinger. Sadly, there exists no readily available Bodanzky broadcast of Die Walküre. Sony here supplies a performance (with Flagstad and Melchior) led by Erich Leinsdorf, whose emergence as Bodanzky’s successor at the head of the Met’s German wing marked the collapse of the Seidl-Mahler-Toscanini-Bodanzky lineage. Leindorf’s Wagner, of which this Feb. 17, 1940, Die Walküre is a fair example, was ever frigid and meticulous; it possessed nothing like the originality and passion of Bodanzky’s readings. Leinsdorf remained on and off the Met’s conducting roster for more than four decades. After Bodanzsky’s death in 1939, and Panizza’s 1942 departure, the company enjoyed no sustained musical leadership, whether German or Italian, until the 1970s advent of James Levin as principal conductor and then music direcor. Though Levine has his fervent admirers, to my ears he is no Bodanzky and no Panizza. And his orchestra, while much better than what he inherited, is a less special instrument than the virtuoso Italian ensemble Bodanzky and Panizza once commanded and maintained. #

My own first in-person experience of Wagner at the Met was a 1962 Die Meistersinger led by Joseph Rosenstock. I was 13 and knew the Prelude from my stirring Toscanini recording. To my surprise, a lumpy sonic pastiche emanated from the pit. This was during the reign of Rudolph Bing (1950-1972), who frankly disliked Wagner. Except for a few Rheingold and Die Walküre performances led by Herbert von Karajan, the Met orchestra in these years could not be expected to produce the Wagner sounds I knew from LPs. It more than bears mentioning that it was Rosenstock who was slated to replace Bodanzky in 1929, when the latter decided to leave the Met after 13 busy seasons. Rosenstock conducted six times, after which Bodanzky was reinstated. It is tempting to speculate what new turn his career might otherwise have taken. He was for instance a known Mahlerite whose New York concert performances included Das Lied von der Erde. But Rosenstock’s ascent had to await another, less momentous era of Wagner at the Met. #

P.S. – After writing this piece, I shared with my wife the 1938 Bodanzky Tristan, act two. When the music ended, her first comment was to ask: “What orchestra was that?” When I told her, she was properly incredulous. #

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers