Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 30

May 31, 2016

Instead of Alexander Nevsky

For every screening with live orchestra of Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (music by Prokofiev), there should be at least a dozen screenings with live orchestra of Paul Strand’s Redes (music by Silvestre Revueltas). #

I supply three reasons: #

1.Revueltas’s score is as great an achievement as Prokofiev’s, yet remains virtually unknown. #

2.Unlike Nevsky, which Prokofiev turned into a terrific cantata, Redes does not readily yield a concert work; it requires pictures to make sense. #

3.Alexander Nevsky is a galvanizing cinematic experience. Redes is only a galvanizing cinematic experience when the music is live. The original soundtrack, recorded in haste, is execrable. #

All this comprises the rationale for PostClassical Ensemble’s latest in its series of Naxos DVDs featuring classic 1930s films with the soundtracks newly recorded. In fact, this same DVD is the world premiere recording of the complete Redes score. #

A full-page article in last weekend’s El Pais (Madrid), by the eminent Spanish novelist Antonio Munoz Molina, takes it all in as follows: #

“Revueltas is one of those composers who for various accidental reasons — his disorderly life and premature death, the fact of his being Mexican – does not occupy the place that he should in a present-day musical culture that clings so tenaciously to the sclerotic. . . . His music, so powerful in itself, highlights the rich artistic crossroads of the thirties, the tensions between modernity and mass culture, between formal innovation and political activism. #

“PostClassical Ensemble’s . . . latest great effort of rediscovery is the premiere recording of the complete score composed by Silvestre Revueltas for a legendary 1935 Mexican film, Redes, in collaboration with the photographer Paul Strand and exiled Austrian filmmaker Fred Zinnemann. It is hard to imagine a more complete conjunction of talent. . . . #

“In 1935 the best films still preserved the purity and expressive visual sophistication of silent cinema. In Redes, imagery and music combine so powerfully that the few spoken words are rather irrelevant. Revueltas’s love of Stravinsky and of the folk music of Mexico inspire a fiercely corporeal rhythmic sensibility applied to the collective choreography of fishermen. Almost twenty years later, in Hollywood, Fred Zinnemann would direct High Noon, in which we find a bedazzled white clarity of inflexible sunlight identical to Redes. Now, with a restored print of Redes and Revueltas’ soundtrack newly recorded by PostClassical Ensemble, the beauty of image and of sound register as never before. As Joseph Horowitz says, it is like experiencing a masterpiece of painting cleaned of centuries of grime. The exhausted and disillusioned Silvestre Revueltas of his final years would never have imagined such posterity.” #

My English translation, abetted by google, does scant justice to this stellar example of what Americans call “arts journalism.” Especially pregnant is Munoz Molina’s observation of the “artistic crossroads of the thirties” – of the “tensions between modernity and mass culture, between formal innovation and political activism.” This perspective nails Revueltas’s high achievement. Prokofiev and Shostakovich excepted, has any other 1930s political composer – think of Hanns Eisler or Marc Blitzstein — so succeeded at mating originality, innovation, and popular appeal? #

May 8, 2016

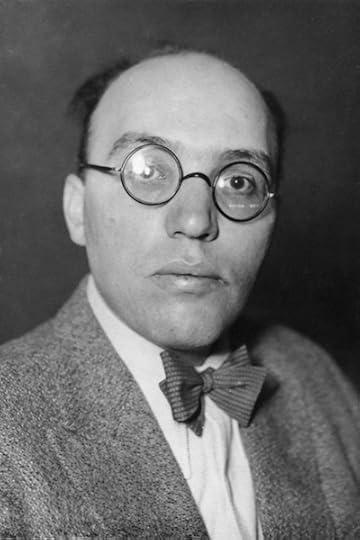

Kurt Weill’s “Note Concerning Jazz”

In Berlin 1929 Kurt Weil wrote a “Note Concerning Jazz” which today reads as both a prediction and a warning. #

Weill wrote in part: #

“Today it appears to me that the manner of performance of jazz is finally breaking through the rigid system of musical practice in our concerts and theaters and that this is more important than its influence on musical composition. Anyone who has ever worked with a good jazz band has been pleasantly surprised by an eagerness, a devotion, a desire for work that one seeks in vain in many concert and theater orchestras.” #

Eighty-seven years later, amen to that. Weill continues: #

“A good jazz musician completely masters three or four instruments; he plays from memory; he is accustomed to the art of ensemble playing. But above all, he can improvise; he cultivates a free, unrestrained style of playing in which the interpreter achieves to the highest degree a productive performance.” #

As I was recently on the West Coast, I had occasion to rent a car for two weeks – and therefore to listen to “classical radio.” Every day I was subjected to recent recordings of familiar music. I quickly discovered a basic similarity in performance style. Never was it “unrestrained.” Never did it achieve “to the highest degree a productive performance.” One rare occasions I encountered a degree of individuality – as in a fresh recording of Beethoven’s E major Sonata, Op. 14, No. 1, rendered by a young pianist of some reputation. But even here there was not a whiff of spontaneity. #

Anyone familiar with how recordings are made the studio should be unsurprised. That note-perfect Beethoven E major Sonata had doubtless been spliced. And you can’t splice a performance credibly unless it’s rendered with some regularity, both internally and sequentially via multiple takes. #

When I returned to my hotel I resorted to youtube for an antidote and listened to Artur Schnabel’s 1930s version of the same sonata. This, too, is a studio recording – but it predates magnetic tape and was not susceptible to splicing. The first thing I noticed was that Schnabel does not maintain anything like a steady pulse. The tempo of the first movement quickens (often in response to harmonic density) and retards (as does a human pulse). This is not a spliceable performance. #

Mainly, however, I noticed the depth and variety of this pianist’s emotional vocabulary – in particular, the unexpected gravitas of the little Allegretto movement. Schnabel’s interpretation here begins with an idea – a state of being. (Wagner once wrote that a conductor’s chief and most elusive responsibility is to extrapolate the “idea” of a piece.) I did not sense anything like that in any of the pristine broadcast recordings I sampled in my rented car. #

Here’s a criterion for an “unrestrained” performance – it cannot be spliced. Many piano performances by Edwin Fischer or Albert Cortot are of this kind. There are even pianists who can sound “unrestrained” in magnetic-tape times – say (to cite opposites), Wilhelm Kempff or Vladimir Horowitz. #

I was subsequently reminded of Weill’s essay, as predictive rather than admonitory, last weekend in Washington, D.C. PostClassical Ensemble (I’m the Executive Director) presented two days of music performed by David Taylor (bass trombone), Daniel Schnyder (saxophones), Matt Herskowitz (piano), and Min Xiao-fen (pipa). The centerpiece was the world premiere of a jazzy Schnyder Pipa Concerto that deserves the widest possible exposure. Like Schnyder’s music generally, it seamlessly transgresses boundaries of style and genre. It also happens to be a fabulous vehicle for a demonic virtuoso – Xiao-fen – who has mastered a variety of plucked instruments; who improvises; who sings; who cultivates an “unrestrained style of playing.” #

Taylor (the world’s most famous bass trombonist) equally exemplifies the “unrestrained.” Last week I twice heard him play the Zuhälterballade from Weill’s Dreigroschenoper. The two performances were so different that you can forget about studios and splicing. The late Gunther Schuller (who crossed over between classical and jazz) (as does Taylor) once called David Taylor “one of the three greatest instrumentalists in the world.” He didn’t say who the other two were. Taylor is great in the ways Weill extolled in 1929. #

Schubert’s “Doppelgänger” is a Taylor specialty. I have heard him do it half a dozen times, all different. Here he is with PostClassical Ensemble at the Kennedy Center. #

Whenever I visit music schools I make a practice of sharing this youtube performance. The range of reaction is very wide. I must confess that emotional reticence is a frequent keynote – an inability to enter into an uncomfortable realm of feeling. There is too often a predilection to attempt to “classify” Taylor – a fruitless endeavor. I even encounter complaints about his attire. #

I discover cheerful versatility and spectacular facility among the young instrumentalists I encounter. What I miss is emotional “unrestraint.” I turn to David Taylor, pushing age 70, for “the highest degree of productive performance.” #

May 4, 2016

The Most Under-Rated Composer?

Who is the most under-rated 20th century American composer? In the wake of the month-long Bernard Herrmann festival curated by DC’s PostClassical Ensemble, I have to believe Herrmann is the most likely candidate. #

The festival, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Georgetown University, and the AFI Silver Theatre, featured three world premieres and a DC premiere. A special focus was a genre now forgotten: the radio dramas of the thirties and forties, which during World War II were a bulwark for home-front morale. The twin creative geniuses were Orson Welles and Norman Corwin – and Herrmann, the supreme radio-drama composer, worked with both of them. #

Thanks to the Herrmann scholar Christopher Husted, we were able to revisit two classic 1944 Corwin/Herrmann radio dramas in live performance: “Untitled” (about a dead American serviceman) and “Whitman” (in which a celebration of the iconic American poet morphs into a patriotic paean). #

“Whitman” proved the revelation of the festival. It unforgettably mates words and music. It peaks where it turns interior. “I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of grass,” writes Whitman. The grass may be “the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven.” Or “the handkerchief of the Lord.” Or “the beautiful uncut hair of graves” – a memorial to dead young men. “Tenderly will I use you, curling grass.” This exceptional passage, combining the transcendental with the erotic, inspires a musical epiphany for strings and harp surpassing many a comparable work mating poetry with words sung. The Herrmann/Corwin “Whitman,” 25 minutes long, deserves wide concert performance as what in music is termed “melodrama” – music underscoring speech. (Cf. PostClassical Ensemble’s own Hiawatha Melodrama. Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon is a masterpiece of melodrama.) PostClassical Ensemble plans to revisit “Whitman” and to record it. #

In short: Herrmann’s radio melodramas were a crucial step towards the melodramas he composed for Vertigo and Psycho – underscoring dialogue, sealing transitions, defining mood. #

Psycho occupied us for two days. The film-music historian Neil Lerner explored Herrmann’s debt to Bartok – who knew how to use strings alone to inspire terror and suspense. We performed – in its previously unheard original version – Herrmann’s atonal Sinfonietta for Strings of 1935 – in some ways, a trial run for Psycho. We watched Psycho and talked about it. But most memorably we performed Herrmann’s 1968 Psycho “Narrative for string orchestra.” Orchestras that continue to perform the “Psycho Suite” (as recorded, e.g., by Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic) should shelve that collection of film cues in favor of Herrmann’s own integrated Psycho synthesis, invaluably recovered by John Mauceri in 1999. As conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez, this 15-minute composition (featured by Simon Rattle on his opening concert of the current Berlin Philharmonic season) built ineluctably to a closing, climactic reprise the three-note motif that anchors Herrmann’s famous film score. #

The festival also featured my favorite chamber work by any American: Herrmann’s sublimely nostalgic 1967 clarinet quintet Souvenirs de Voyage. In a program note, I wrote of the quintet’s long, masterfully woven first movement: “We feel we have journeyed somewhere, even if that makes no ultimate difference in a world of sadness and remembrance.” #

“Bernard Herrmann: Screen, Stage, and Radio” was part of an all-American PostClassical Ensemble season, exploring an “alternative narrative” for American music outside the over-exposed Copland/Boulanger axis. #

We are very far from taking the full measure of Bernard Herrmann. #

April 13, 2016

$1 for Music Unwound

The NEH Music Unwound consortium, which most recently brought Dvorak’s New World Symphony to an Indian reservation, has been re-funded by the Endowment with a $400,000 grant, bringing the total NEH investment to $1 million since the inception of Music Unwound in 2010. #

The consortium has quickly evolved into a major opportunity and challenge for American orchestras to rethink themselves as “humanities institutions.” It funds thematic, cross-disciplinary concerts linked to high schools, colleges and universities, and museums. The premise is that such programming (which more resembles what museums do) supports audience engagement and development, and also outreach and institutional collaboration. #

Three protean topics have been in play: “Dvorak and America,” “Copland and Mexico,” and “Charles Ives’s America.” A fourth topic – “Kurt Weill’s America” – has now been added. The themes include immigration, World War II, American identity, and the Mexican cultural efflorescence of the 1930s. All the main concerts include visual tracks and scripts. There have also been film, dance, and theater ingredients. #

As director of Music Unwound, I have been delighted and surprised by the alacrity with which new relationships have been formed and sustained. Music Unwound has helped to create a permanent bond between the Pacific Symphony and Orange County’s Chapman University, and also between the El Paso Symphony and the University of Texas/El Paso. By an incredible coincidence, the visionary educators driving these relationships in the two universities have both just been promoted: Daniele Struppa (a mathematician) will shortly become President of Chapman, and Frank Candelaria (a music historian) is now Associate Provost of UTEP. Both of these educational leaders are driven to infuse the arts and humanities across the curriculum. #

Another surprise has been the increasing inclusion of student musicians. The Brevard Music Festival, which joined the consortium this year, is a major summer training camp for orchestral musicians. Under Music Unwound, it will supplement such training with humanities instruction – so that all the collegiate instrumentalists taking part in “Dvorak and America” this summer will read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha and ponder its pertinence to Dvorak’s American style. #

DePauw University, also new to Music Unwound this year, will produce a Kurt Weill festival including Street Scene – Weill’s “Broadway opera” about immigration. The participating students will read Elmer Rice’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Street Scene, and explore the process by which it was turned into an opera by Weill, Rice, and Langston Hughes. The same exercise will subsequently take place at Brevard and UTEP. As Mark McCoy, the exceptional Dean of the DePauw Music School, is about to become President of the university, he will – like Struppa and Candelaria – be commanding a comprehensive humanities exercise from the top. #

The other consortium members are the Buffalo Philharmonic (lead partner), the North Carolina Symphony, the New Hampshire Music Festival, the Las Vegas Philharmonic, and the South Dakota Symphony. #

In Las Vegas and El Paso, “Copland and Mexico” will connect to large Hispanic populations – including both high school and college students. #

Donato Cabrera, Music Director of the Las Vegas Philharmonic, and Delta David Gier, Music Director of the South Dakota Symphony, will join me in Baltimore June 11 at the annual conference of the League of American Orchestras to discuss Music Unwound and present our experiences to date. #

March 9, 2016

Dvorak on the Reservation

Sisseton, in the northeastern corner of South Dakota, sits within a Dakota Indian reservation called Sisseton Wahpeton. The population – 2,500 – is half Native American, half non-Native. #

Last Monday night, Sisseton hosted the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra in a program, “Dvorak and America,” at the local high school auditorium. This multi-media production, which includes a “visual presentation” extrapolating the American accent of the New World Symphony, has been seen throughout the United States for a decade. Unique to South Dakota, however, was the participation of the Creekside Singers of the Pine Ridge Reservation (pictured above) in a symphonic composition by the Native-American composer Brent Michael Davids. Sisseton also produced the most eclectic audience I have ever seen at a symphonic concert. Both the very young and the very old were well represented, as was the local Dakota population. #

Part of the NEH’s “Music Unwound” orchestral consortium, this singular adventure in cultural outreach was the latest installment in the South Dakota Symphony’s Lakota Music Project, which makes music for and with Native Americans. The Project’s touring program, comprising back-and-forth musical exchanges, has since 2009 been given nearly thirty times on six reservations. It has also commissioned new works from both Native and non-Native composers. Crucially, it is mutually conceived and implemented by the Symphony and its Native American partners. #

As I have many times observed on this blog, the Dvorak topic is protean. His espousal of a future American concert idiom based on “Negro melodies” and Native American lore remains provocative and timely. The “Dvorak and America” program plays with particular pertinence in New York City, where it has been produced by both the New York Philharmonic and the late Brooklyn Philharmonic; a city of immigrants, New York took Dvorak to heart. If it ever makes it to Boston, “Dvorak and America” will powerfully recall a historic moment when New Englanders denounced Dvorak as a “negrophile” and shunned his influence and advice. In Fayetteville, presented by the North Carolina Symphony, “Dvorak and America” memorably connected with an African-American audience. #

In Sisseton, “Dvorak and America” was doubly resonant. Dvorak’s sadness of the prairie, enshrined in the Largo of his great American symphony, instantly evoked the wide horizons directly at hand. The symphony’s many allusions to Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha, highlighted by visual renderings including the Dance of Pau-Puk Keewis with its moccasin bells (Dvorak’s triangle), served to introduce an Indian reservation to the long-ago Indianists movement of which Dvorak was part. #

How did the Native Americans in the room process the whirling, spinning dance at Hiawatha’s wedding feast? As Dvorak’s “Indian” mode makes no attempt to evoke actual Native American music, we undertook a necessary consideration of what anthropologists call “cultural appropriation.” Our resident anthropologist, Ronnie Theisz, has participated in the Lakota Music Project since its inception. He is an Austrian who upon earning a Ph. D. at NYU took a job on a South Dakota reservation and never looked back. On this occasion, Ronnie contributed a mini-tutorial on the structure and vocal techniques of Lakota song. He also contrasted the nineteenth century’s celebration of the “noble savage,” as in Longfellow and Dvorak, with such twentieth century Indianist kitsch as Victor Herbert’s “Dagger Dance” – as performed by the South Dakota Symphony; as appropriated by the Hamms Beer cartoon commercials I remember from my childhood. That beer commercial drew laughter – but no such depiction of “injun country” could conceivably be purveyed today. #

Another participant was Chris Eagle Hawk, an honored elder of the Oglala Lakota Tribe, who eloquently described the role of music in Lakota culture, and the sanctity of the Black Hills. #

The same South Dakota Symphony Dvorak program was given on subscription Saturday and Sunday in Sioux Falls (population 170,000). Not the least remarkable aspect of these three concerts was the caliber of the orchestra itself and of its conductor, Delta David Gier. He has led the South Dakota Symphony since 2004. For many years an assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic, he has since raised two children in Sioux Falls. It was he who initiated the Lakota Music Project. #

Gier’s reading of Dvorak’s Largo was the most affecting I have ever encountered. It was also the slowest, and in places the softest. His splendid English horn soloist, Jeffrey Paul, is South Dakota’s principal oboist. He also composes, conducts one of two South Dakota Symphony youth orchestras, and plays the electric guitar. #

The current South Dakota Symphony season puts to shame a major American orchestra that resides in eastern Pennsylvania. There are no celebrity soloists, no Rachmaninoff or Tchaikovsky concertos. The season began with Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, part of an ongoing Mahler cycle that now only lacks Nos. 8 and 10. Next season opens with John Luther Adams’ Become Ocean, winner of the 2014 Pulitzer Prize. In fact, there is contemporary music on every Classics program save the annual semi-staged opera – Don Giovanni. Last season, it was Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman. #

These enterprising repertoire choices are doubtless one reason the musicians of the South Dakota Symphony seem as motivated and engaged as any I have encountered among professional American orchestras. I had occasion to chat backstage with the principal double bass, Mario Chiarello. Mario is also the conductor of one of three Sioux Falls high school orchestras. He told me that after 9/11, his Lincoln High orchestra prepared Mozart’s Requiem in eleven days. He also said that Sioux Falls’ “Harmony” program, modeled on Venezuela’s El Sistema, in conjunction with a separate Suzuki-based program, is producing skilled young instrumentalists in such profusion that they will burst the seams of the city’s existing student symphonic ensembles. He counts 2,631 string players in the Sioux Falls public schools. Many are not native speakers of English. #

My most memorable backstage exchange, however, was with Chris Eagle Hawk. He is a man whose very presence commands attention. He shared an axiom about listening. One should listen with one’s heart, he said, and only later process that with one’s brain. In the meantime, one’s mouth should remain shut. This is a lesson I have never learned. Onstage, during one of three post-concert discussions, I asked Chris what he thought of the New World Symphony. “Awesome,” he replied. Was he hearing it for the first time? I innocently inquired. Well, no – he first encountered Dvorak’s symphony in college long ago. This from a man who grew up in a tent and first spoke English at the age of seven. #

At Sisseton we were greeted by David Flutes, chairman of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Mayor Terry Jaspers, and Jane and John Rasmussen. Jane is director of the Sisseton Arts Council. She and her husband asked me to inscribe their copy of my book Classical Music in America: a History – which, moreover, they had evidently read. John said that racial tension in Sisseton had considerably abated over the past decade. One reason, he added, was the South Dakota Symphony’s Lakota Music Project. #

March 1, 2016

Gergiev and the Vienna Philharmonic

Last Sunday afternoon’s Vienna Philharmonic concert at Carnegie Hall began with a Valery Gergiev moment. Mounting the podium, he turned to the concertmaster and shrugged his shoulders to acknowledge that (as sometimes happens to Gergiev in particular) he had arrived a little late and kept the musicians waiting. He then took a deep breath and launched an unforgettable reading of the Prelude and Good Friday Spell from Wagner’s Parsifal. #

The second half of the concert, with Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony, was incendiary – a rare musical phenomenon that bears some scrutiny and analysis. #

Wilhelm Furtwangler was famous or notorious for his indistinct baton gestures. He did not wish to over-instruct his players. He invited an initiative that was partly theirs. #

With his ever fluttering hands and arms, Gergiev insists that his performances, no matter how much or little rehearsed, not be over-prepared. The pay-off is an intense synergy unknown among conductors who impose submission to pre-calibrated rubatos, sharply drawing attention to themselves. A Furtwangler or Gergiev, by comparison, can unleash a primal musical force that is wholly impersonal. They can ignite a Dionysian intensity that can only be leaderless, can only be communal. #

Vienna’s magnificent orchestra is different from Gergiev’s magnificent Mariinsky Orchestra. Its sounds are sweeter. Its synergy with Gergiev is dynamic. The fullness and depth of sonority, the regal low strings informing Sunday’s performances were Gergiev signatures. But there was more daylight than in the St. Petersburg sound. (I am not choosing, just comparing.) #

The resulting performance of the Parsifal music doubtless displeased the precision-police. But Gergiev’s reading wasn’t about precision. It feasted on color and texture. It also majestically sustained a musical line stretching to infinity. #

The Manfred Symphony, after intermission, isn’t much heard for a reason. A 50-minute essay in Faustian striving and redemption, it sags in places. I read in Jack Sullivan’s Carnegie program note that Leonard Bernstein called it “trash.” Certainly Tchaikovsky’s Manfred, estranged from humankind, at home with dark despair, requires inspired advocacy. As with Shostakovich’s kindred confessional symphonies, Manfred turns banal absent maximum emotional and physical commitment. As with so much of Liszt, it needs to be “made” – molded, interpreted. #

The Gergiev/Vienna Manfred Symphony was a performance for the ages. The first movement coda – an avalanche of grief – was titanic. Even more remarkably, the symphony’s apotheosis told. I still cannot believe that this problematic note of triumph — laced with harp arpeggios, punctuated by stentorian organ chords — is an emotional state Tchaikovsky earned. But I will never hear a Manfred performance more momentarily persuasive. #

The first encore was the act two “Panorama” from The Sleeping Beauty – so airborne, so trembling with beauty that only levitating ballerinas could have danced to it. In fact, a complete Sleeping Beauty delivered by this orchestra and conductor, in this hall, would surely surpass any possible performance by the American Ballet Theatre or New York City Ballet. Those companies do not nearly possess the musical or acoustic resources to do justice to Tchaikovsky (or Prokofiev). This is a topic

I have belabored before. #

The second and final encore was the “Thunder and Lightning” Polka by Johann Strauss, Jr. Here Gergiev let the orchestra play by itself (with plenty of thunder). The unlikely sequence of Wagner-Tchaikovsky-Tchaikovsky-Strauss proved magically cathartic. #

Musicians I know complain they cannot follow Gergiev’s beat. I know orchestra managers who consider him unreliable and under-prepared. I cannot imagine what priorities they pursue. #

February 23, 2016

What Texas City is a National Cultural Showcase?

For the past decade I have enjoyed the privilege of regularly collaborating in “Dvorak and America” festivals with Kevin Deas, one of the supreme African-American concert artists of our day. His performances of “Goin’ Home” and the “Hiawatha Melodrama” invariably make a great impression. #

Kevin’s self-evident generosity of spirit is as vital to his appeal as his luscious bass-baritone. But he has his foibles, one of which is a chronic reluctance to sign CDs. #

For the recent El Paso “Dvorak and America” festival, I instructed both the El Paso Symphony and the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) to purchase hundreds of CDs for signature and sale. The CD in question is “Dvorak and America” (Naxos), featuring Kevin Deas singing “Goin’ Home” and the “Hiawatha Melodrama,” plus a number of startling Dvorak-related novelties. #

Kevin invariably predicts that no one will purchase “Dvorak and America.” Knowing El Paso, I knew otherwise. I managed to goad him into venturing into the lobby of the Plaza Theatre at intermission, where a table stacked with CDs awaited his attention. He discovered a line of customers so long that it disappeared around a corner. They were young and old. Many were Hispanic. Some were first-time concertgoers. They all had something they wanted to tell him. And they wanted to buy signed CDs. #

In fact, El Paso is the perfect place for a Dvorak festival. Serendipitously, the El Paso Symphony is the only American orchestra with a Czech conductor. His name is Bohuslav Rattay and he is terrific. The orchestra enjoys a following both hungry and diverse. The orchestra roster includes 18 Hispanic musicians. #

As for UTEP, I have never encountered more eager or absorbent students. Of UTEP’s 22,800 students, 78 per cent are Hispanic. More than 60 per cent of UTEP graduates are the first in their family to earn a B.A. One-third of all UTEP students report a family income of $20,000 or less. They disclose no sense of entitlement. The faculty is distinguished – pedagogues who savor the opportunity at hand. The school is a launching pad. Its purposes and effectiveness are inspirational and obvious. #

El Paso itself, with a population of 650,000 (80 per cent Hispanic), is a perfect size for communal cultural endeavor. The orchestra, the university, the public schools partner easily. The various departments of the university are seamlessly collaborative. For the Dvorak festival, a fabulous scholar of nineteenth century American literature, the Melville specialist Brians Yothers, boned up on Longfellow and vitally participated in our explorations of the impact of The Song of Hiawatha on the New World Symphony. #

The Dvorak topic is protean, actually inexhaustible. His ecumenical conviction that African-Americans and Native Americans were emblematic Americans, crucial to any valid notion of American identity, remains provocative and timely. #

The El Paso festival began with a presentation at Chapin High School that was streamed to other public schools. I lectured for three large UTEP classes, connecting with a mixture music and non-music undergraduates and graduate students. Kevin and I performed our “Harry Burleigh Show” for a gathering of all UTEP music majors and grad students. The multi-media El Paso Symphony concerts featured the Hiawatha Melodrama and a visual presentation for the New World Symphony. The pre-concert speaker was Brian Yothers on Longfellow – his range of influence, his shifting reputation. #

Finally, there were two concerts on the UTEP campus. Lowell Graham led the UTEP Orchestra in an arresting program of music from Dvorak’s America by George Chadwick, Edward MacDowell and Dudley Buck. The UTEP Chorale offered spirituals and rare “Indianist” works. Here, the main event was Arthur Farwell’s 16-part a cappella “Pawnee Horses,” an American choral masterpiece that remains virtually unknown, brilliantly prepared by UTEP’s Elisa Wilson. #

More than 300 UTEP students attended the El Paso Symphony concerts. Many had never before heard an orchestra. #

Two indispensable factors were Frank Candelaria, a visionary music historian who also serves as UTEPs Associate Provost, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, which supported the festival as part of its Music Unwound orchestral consortium. #

Next February I return to El Paso for “Copland and Mexico,” which will use Aaron Copland’s Mexican epiphany as a starting point for exploring the Mexican cultural efflorescence of the 1930s. In that decade, it was not only Berlin and Paris that lured American artists and intellectuals abroad. Copland, Paul Strand, John Steinbeck, and Langston Hughes were among those flocking south of the border. Mexican’s own cultural vanguard included a composer of genius still insufficiently recognized: Silvestre Revueltas. The iconic Mexican film Redes, scored by Revueltas with cinematography by Strand, will be the centerpiece of “Copland and Mexico.” UTEP, the El Paso Symphony, the El Paso Film Festival, and the El Paso Museum are already on board. There is a strong push to include events across the Rio Grande in Juarez. The opportunities at hand are inexhaustible. #

More than any other American city I know, El Paso deserves to be recognized as a national showcase for the ways in which cultural and educational institutions can work together to instruct, inspire, and unite. #

February 12, 2016

Celebrating Bernard Herrmann

A towering figure in twentieth century American music, Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975) has long been pigeon-holed as a “Hollywood composer.” Though he is widely acknowledged the supreme American composer for film (Citizen Kane, Vertigo, North by Northwest, etc.), his concert output remains virtually unknown. Working with the young Orson Welles and later with the legendary radio and screenwriter Norman Corwin, he was also America’s foremost radio composer, and conductor of a radio orchestra – William Paley’s visionary CBS Symphony – that boldly promoted new and unfamiliar music. #

The forthcoming Bernard Herrmann festival in Washington, D.C. – a collaboration of PostClassical Ensemble, the National Gallery of Art, the AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center, and Georgetown University — is the first ever to celebrate Herrmann “in the round” as one of the most important and influential American musical personalities of his generation. It includes world-premiere recreations of two classic Corwin/Herrmann radio dramas with live actors and orchestra, the DC premiere of Herrmann’s “Psycho: A Narrative for String Orchestra,” a one-hour exploration of “The Music of Psycho” with live orchestra, screenings of 21 films, and much more. In addition to myself and PostClassical Ensemble Music Director Angel Gil-Ordonez, the participants include the conductor/scholar John Mauceri, the Herrmann scholar Christopher Husted, the Corwin scholar Dan Gediman, the film-music scholar Neil Lerner, the composer’s daughter Dorothy Herrmann, and Norman Corwin’s daughter Diane Corwin Okarski.

The festival has been undertaken in the conviction that Simon Rattle’s performance of Herrmann’s Psycho Symphonic Narrative, opening the present Berlin Phiharmonic season, is a harbinger – that Herrmann is a major twentieth century musical personality whose time will come, and relatively soon. He has never lacked admirers, even venerators, for his incomparable film scores. But no musician capable of inventing the brilliant faux French Romantic opera aria of Citizen Kane, or the immortal shower screeches of Psycho, or the daring Liebestod of The Ghost and Mrs. Muir could possibly have failed to matter beyond Hollywood. That Herrmann’s pioneering radio work, as composer and conductor, is a necessarily ingredient in appreciating Herrmann’s film genius is in fact one starting point of our festival.

Of the festival’s participants, John Mauceri was responsible for rescuing the Psycho narrative from undeserved oblivion. Christopher Husted was responsible for creating the performance materials for the radio plays “Untitled” (1944), about a dead American soldier, and “Whitman” (1944), which pays tribute to Walt Whitman. During World War II, these and other Norman Corwin radio dramas, scored and conducted by Herrmann, were a vital part of the “home front” effort. The radio-drama genre, of which Corwin was the acknowledged master, became a forgotten art with the advent of television. Dan Gediman, a peerless authority on Corwin and the golden age of radio drama, will use audio clips to illustrate the Corwin/Herrmann collaboration and how it fostered Herrmann’s film work to come.

The festival screenings (April 1 to 24) will take place at National Gallery of Art and at the AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center. The National Gallery of Art screenings are free of charge. Tickets for screenings at AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center can be purchased at AFI.com/Silver or in person at the box office. Select screenings will be accompanied by commentary. The other festival events (all free of charge) are: #

Friday, April 15, 2016: Bernard Herrmann “Interplay” at Georgetown University (McNeir Auditorium) #

PART ONE: 1:15 to 2:45 pm–Dan Gediman on radio drama (with audio clips)

— Corwin/Herrmann: “Untitled” (1944) – radio play with live actors and GU Orchestra; directed by Anna Harwell Celenza

–Dorothy Herrmann on her father’s magnum opus, the opera Wuthering Heights (with audio clips and a film clip from the film The Ghost and Mrs. Muir)

–Discussion: Gediman, Herrmann, Christopher Husted, Neil Lerner, etc.

PART TWO: 7:30 –Dan Gediman on the legendary Norman Corwin/Bernard Herrmann collaboration, illustrating an organic interpenetration of script and music (with live excerpts from “Untitled” with the GU Orchestra)

INTERMISSION

— 8:45: Christopher Husted on the CBS Symphony, created by William Paley and conducted by Herrmann as a showcase for new and unfamiliar music (the antithesis of David Sarnoff’s NBC Symphony, with Toscanini). (with audio clips)

–9:15: Neil Lerner on Herrmann the film composer – how his collaborations with Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock built on his radio work with Corwin (with film clips)

–9:45: Discussion

Saturday, April 16, 1 to 6 pm: “The Music of Psycho” at National Gallery of Art Film Auditorium

PostClassical Ensemble conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez #

1pm – Dan Gediman introduces “Whitman” (with audio clip)

1:15 pm – The classic Norman Corwin/Bernard Herrmann radio play “Whitman” (1944) with live actors and PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez (world premiere of the reconstruction by Christopher Husted). With Sean Craig as Walt Whitman; directed by Anna Harwell Celenza.

1:45 pm – “The Music of Psycho” – a presentation by Neil Lerner and Christopher Husted, with live musical excerpts (Herrmann and Bartok) performed by PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez (60 min)

2:45 pm — Intermission

3 pm – Psycho (1960) – (110 min)

5 pm – Discussion (Dorothy Herrmann, Gediman, Lerner, Husted, Horowitz, Gil-Ordonez, etc.) – with additional audio and film clips

Sunday April 17, 2016 at 3:30 pm: Concert at National Gallery of Art West Garden Court #

PostClassical Ensemble conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez; commentary by John Mauceri #

David Jones, clarinet #

Natenal Draiblate and Eva Cappelletti-Chao, violins #

Phillipe Chao, viola #

Benjamin Capps, cello #

Bernard Herrmann: Souvenir de Voyage (Quintet for Clarinet and Strings (1967)

Lento; Allegro moderato #

Andante (Berceuse) #

Andantino (canto amoroso) #

Intermission #

Bernard Herrmann: Sinfonietta for Strings (1935-36) #

Prelude: Slowly #

Scherzo: Presto #

Adagio #

Interlude: Allegro #

Variations #

Bernard Herrmann: Psycho: A Narrative for String Orchestra (1968, restored and edited by John Mauceri in 1999) #

DC Premiere

Discussion: Festival Wrap-Up with John Mauceri, Christopher Husted, Angel Gil-Ordonez, and Joseph Horowitz

#

November 3, 2015

American Music — An Alternative Narrative

Bernard Herrmann, whose film credits include Psycho, Citizen Kane, Vertigo, and (his most Romantically charged score) The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, is one of eight featured composers on PostClassical Ensemble’s all-American 2015-16 season. The others are Harry Burleigh, Charles Ives, George Gershwin, Kurt Weill, Lou Harrison, and Daniel Schnyder. #

The season begins this Saturday night in DC with “Deep River – The Art of the Spiritual” – a multi-media exploration of how Harry Burleigh transferred spirituals into the concert hall. (To see the entire schedule, click here.) #

Binding these eight composers is an “Alternative Narrative” based on my Classical Music: A History (2005). #

The Standard Narrative for American concert music starts with Aaron Copland after World War I. It presumes that Copland and others of his generation were the first to create an “American style” based on American songs, American rhythms, American energies. Such populist Copland scores as Billy the Kid (1938) and Appalachian Spring (1944) are seen as seminal. At the same time, these composers are observed engaged in the project of creating an American symphonic canon, hot in pursuit of the Great American Symphony. #

Part two of the same narrative, post-World War II, observes a mass migration to non-tonal styles, Copland included. This music (a product of Cold War times) was not remotely “populist.” In fact, it drove a schism between composer and audience. #

In Classical Music in America, I propose that in fact there are multiple American musical narratives, none of which takes precedence over the others. I call these “musical streams, all of which achieved substantial results and none of which reached fruition.” In particular, I dispute the assumption that there was no American, American-sounding concert music of great merit before Copland. #

The biggest flaw in the Standard Narrative is that, having been constructed beginning in the thirties, it fails to account for the genius of Charles Ives – whose music was not yet generally known. It is now evident that Ives composed Great American Symphonies some time before the interwar composers took up that cause: both his Symphony No. 2 (1907-1909) and Symphony No. 4 (1912-1925) are supreme achievements, mating American vernacular sounds and images with a hallowed European template. #

And there are others. Louis Moreau Gottschalk, back in the 1850s, used black Creole tunes from his native New Orleans to fashion a captivating American idiom – music that didn’t re-enter the repertoire until the 1950s. In Boston, George Chadwick (dismissed by Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Leonard Bernstein in their influential versions of the Standard Narrative) created Jubilee (1895) and other salty American cameos that our orchestras have yet to discover. In New York, Antonin Dvorak turned himself into an American, creating an 1890s New World style inspired by “Negro melodies.” #

And there is a “maverick” American tradition defined by such idiosyncratic, self-made Americans as Henry Cowell, John Cage, and Lou Harrison. Beginning with stray car parts, they collaboratively created the percussion ensemble as a musical genre. They also prophetically merged Western and Eastern musical styles. Harrison (1917-2003), in particular, was an American master who had no use for the Standard Narrative. He heralded today’s pervasive “postclassical” music, a post-modern phenomenon that chucks every assumption that “classical music” on the European model retains priority as the highest possible realm of musical experience. #

Finally, there is a tradition of “interlopers” who have blended American popular and classical styles. Here the seminal figure is George Gershwin – once widely dismissed (as was Ives) as a dilettante. If we can admit film music to this “musical stream,” the towering figure is Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975), best-remembered for his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock on such films as Psycho, Vertigo, and North by Northwest. Herrmann was ignored by the established non-tonal composers of his day. Now is the time to discover his concert works – of which the Clarinet Quintet (1967) is an American masterpiece somewhat in the style of Vertigo. As a leading radio conductor, Herrmann was an early champion of Charles Ives (as was Lou Harrison). #

PostClassical Ensemble’s season explores alternatives to the Standard Narrative. From the fecund pre-World War I period, we celebrate Dvorak’s assistant Harry Burleigh (1866-1949), who was instrumental in transplanting spirituals into the concert hall. In fact, such pivotal Burleigh arrangements as “Deep River” are as much compositions as transcriptions – an observation we’ll explore in “Deep River” – The Art of the Spiritual. #

Coming next, chronologically, is Charles Ives, whose Second Symphony (belatedly premiered by Leonard Bernstein in 1951) has yet to attain the canonic status it obviously deserves. PCE’s Angel Gil-Ordonez conducts the Georgetown University in this American masterpiece – part of a PCE-produced Ives weekend also including two peerless Ives advocates: baritone William Sharp and pianist Steven Mayer. #

Bernard Herrmann – Screen, Stage, and Radio is a multi-week immersion experience advocating the versatility and ingenuity of a leading American musician still incompletely known. Our series of screenings and concerts includes world-premiere restorations of two classic Norman Corwin radio dramas (music by Herrmann) in live performance, as well as a one-hour exploration of The Music of Psycho. #

Lou Harrison – The Indonesian Connection illuminates Harrison’s groundbreaking percussion compositions, alongside Cowell and Cage, as well as his mature gamelan-inspired idiom. (PCE will also record a Harrison CD for Naxos.) #

Finally, our “Schnyderfest” explores the musical world of the Swiss-American composer Daniel Schnyder (b. 1961) – an emblematic postclassical musician who delves deeply into jazz (he is a gifted saxophonist), and also mines the musics of Africa and Asia. With California’s Pacific Symphony, PCE has commissioned a Schnyder Pipa Concerto for the pipa genius Min Xiao-fen – to be premiered at the National Gallery of Art May 1. Our Schnyder weekend also includes Schnyder’s takes on George Gershwin and on Kurt Weill (a key post-Gershwin “interloper”), as well as F.W. Murnau’s silent cinema classic Faust (1926) with Schnyder’s film-score performed live. #

I write in Classical Music in America: “In 1965 Elliott Carter lamented ‘the tendency for each generation in America to wipe away the memory of the previous one, and the general neglect of our own recent past, which we treat as a curiosity useful for young scholars in exercising their research techniques – so characteristic of American treatment of the work of its important artists.’ Carter’s plaint applies to . . . the streams of American classical music, each of which so little interacted with any other. It points to a pervasive fragmentation, to an absence of lineage and continuity complicated by a late start and a heterogeneous population, by two world wars and the confusing influx of powerful refugees. But this same fragmentation may be read as a protean variety: of composers who imitated Europe or rejected it; who preferred German music or French; who viewed the popular arts as a threat or as a point of departure. To a surprising degree – surprising because American institutions of performance have understood so little – American composers have partaken in the diversity of American music as a whole. It is, in the aggregate, a defining attribute.” #

October 29, 2015

The Real Vladimir Horowitz

Sony’s new 50-CD compilation, “Vladimir Horowitz: The Unreleased Live Recordings 1966-1983,” is a startling exercise in candor three times over. #

1.It argues that a series of “live” Horowitz recitals, released on RCA between 1975 and 1983 and edited by RCA’s Jack Pfeiffer, misrepresent and diminish those concerts by fixing wrong notes. #

2.It frankly documents Horowitz’s artistic nadir: the disastrous 1983 concerts he played while heavily medicated. #

3.It blames this debacle on the publication of Glenn Plaskin’s unnervingly unsympathetic Horowitz biography of 1983. #

The first of these claims, fingering a company absorbed by Sony, is made explicit by an essay, “Horowitz: The Penultimate Chapter,” by another Horowitz: my son Bernie, who (as “Bernard Horowitz”) contributes an essay reading in part: “We can now see clearly that the RCA versions were so heavily spliced and edited as to project a Madame Tussaud version of Vladimir Horowitz.” Bernie singles out a 1979 Chicago performance of Schumann’s Humoreske: “[It] documents an artist with an original reading of a complex work, executing it down to the minutest detail and bringing the audience along every step of the way. It strikes a fatal blow against those who denigrate Horowitz’s musicianship or question his depth.” #

This invitation to compare RCA’s “live” products with the new, unretouched Sony releases is worth taking seriously, and not only because Horowitz’s unedited Chicago Humoreske is (unlike Pfeiffer’s synthetic recreation) one of his most artistically compelling performances. The practice of recording music in a studio, sans audience, begot the practice of combining multiple “takes” in pursuit of perfection. All this started understandably enough: long ago, studio recordings were sonically superior to anything that could be captured in a concert hall or opera house. Even so, my favorite recordings, of whatever vintage, are rarely studio-made. (Try comparing Feodor Chaliapin’s famous Boris Godunov studio excerpts of 1922 with his less famous but more truthful Covent Garden performance of July 4, 1928, now readily available on youtube.) #

The second claim inherent to “The Unreleased Live Recordings” is also made explicit by Bernie’s essay when he writes that in 1983 Horowitz “reached a point of collapse.” The most glaring evidence in the new Sony set is a Boston recital on April 24, 1983. To see what Horowitz looked like – bloated, dazed – at this sad juncture, there is the evidence of his notorious Tokyo recital of June 11. #

Had Horowitz disappeared from view in the wake of his Tokyo debacle, the trajectory of his career would have terminated with a descent into obscurity. That he was able to put all this behind him – that he in fact enjoyed what Bernie calls an Indian Summer – required absorbing the shock of the Plaskin biography. Bernie reveals: #

“As the ‘70s drew to a close, Glenn Plaskin began collecting information for an unauthorized biography. In 1979, he wrote to Caine Alder, a longtime Horowitz devotee who had provided Plaskin access to a lifetime of Horowitz research: ‘To get a substantial advance . . . and good commercial response to the book we cannot make a white-washed tribute that ignors ]sic] facts and figures about Horowitz’s life that may be painful to him . . . The tensions of performance and emotional turmoil at times sent him into depressions and evidently into institutions at various times in his life. The suicide of his daughter and what the means, ETC., ETC.., ETC.’” #

The resulting book, which reached Horowitz in stages during its period of gestation, began its sordid life-narrative by claiming (erroneously) that Horowitz fabricated his place of birth. It portrayed an artist without a core. #

Horowitz, to be sure, was a man with troubles. His family was decimated by the Russian Revolution. He wound up in the US, age 24, unworldly and unmoored. As with so many artists, he was the beneficiary or victim of a nervous intensity so powerful it could have destroyed him. Sony’s “Unreleased Live Recordings” newly discloses what he could accomplish when, in late mid-career, he channeled his demons without taming them. #

(For more Horowitz on Horowitz on Horowitz, click here and here.) #

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers