Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 29

December 14, 2016

Trifonov Plays Shostakovich

No other music so instantly evokes a sense of place as that of Dmitri Shostakovich. When Daniil Trifonov launched Shostakovich’s E minor Prelude at Carnegie Hall last week, the bleakness and exigency of Stalin’s Russia at once chilled the huge space. The Shostakovich affect can seem exotic or native, according to circumstance. I would say it today complements that part of the national mood concentrated in the Northeastern United States and 3,000 miles away on the West Coast.

Trifonov offered a substantial Shostakovich set: five of the 24 Preludes and Fugues composed in homage to Bach in 1950-51. This experience proved doubly revelatory. Comprising the Preludes and Fugues in E minor, A major, A minor, D major, and D minor, the sequence registered as a compositional achievement unsurpassed by other post-World War II composers for solo piano. And Trifonov’s readings were boldly individual. Shostakovich – a considerable pianist – favored a plain style. Trifonov’s style, with its emphasis on color and refined tonal liquidity, is remote from the composer’s.

The D major Fugue, in particular, was barely recognizable. Shostakovich composed a sharp, acerbic Allegretto. Trifonov here produced a Prestissimo blur, an arresting, elusive impressionistic cameo.

The D minor Prelude and Fugue is the titanic capstone to Shostakovich’s 24. Shostakovich’s recording is dry and imperious. Trifonov’s reading is Lisztian: Romantically plastic, generously pedaled. It was the charged high point of the evening.

The remainder of the program was standard: a Schumann first half; Stravinky’s Petrushka to close. I know Carnegie has to sell tickets – but this young pianist may have acquired a following ready for anything. It has been years since I encountered a New York audience – the hall was packed – as absorbed in a purely musical experience. There is nothing exceptional about Trifonov’s hair or attire. He is neither glamorous nor notorious. At the age of 25 he is already embodies a species become rare: a major concert pianist. He also composes.

What comes next for this young man? Aside from my son, I noticed no listeners approximately the pianist’s own age. A decade hence, will Daniil Trifonov fill Carnegie Hall? And what will be be playing? The marginalization of classical music accelerates apace.

PS: PostClassical Ensemble’s Shostakovich-Weinberg festival this March includes another boldly individual pianist: Alexander Toradze, in Shostakovich’s First Piano Concerto. Edward Gero of the Washington Shakespeare Theatre will play Shostakovich. We will have occasion to compare Shostakovich’s official pronouncements of the 1930s and ‘40s with what he later had to say about his Fifth and Seventh Symphonies. To see Ed Gero as the younger Shostakovich, and find further information on the concerts, click here.

October 2, 2016

Brendel and Schubert

This weekend’s “Wall Street Journal” includes my review of Alfred Brendel’s new essay collection, “Music, Sense, and Nonsense,” as follows:

It is axiomatic, to some, that music speaks for itself. But there are musicians who both perform and speak for music. In this country, Leonard Bernstein was surely the most influential exemplar. Bernstein’s landmark campaign for the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, which he greatly helped to canonize beginning in 1959, included popular sermons on television and in print. But Bernstein’s 1960 Young Peoples’ Concert titled “Who Is Gustav Mahler?” and his 1973 Norton Lecture extolling Mahler’s Ninth as an iconic 20th-century masterpiece were ephemeral acts of advocacy: By themselves, they do not endure as important statements.

Across the water, the champion double advocate was Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924). A musician singular in temperament and personality, Busoni was the supreme concert pianist of his generation as well as a composer whose wizardry will always attract a dedicated minority of listeners. His essays and letters, vivid embodiments of a spirit infused with paradox and humanity, will be read as long as there are people who care about musical meaning and aesthetics.

Alfred Brendel, whose collected essays and conversations in “Music, Sense and Nonsense” total more than 400 pages, is a prominent retired pianist (he departed the stage in 2008) who enjoys continued prominence as a writer. He also happens to be notably influenced by Busoni—by the “peculiar serenity” of his music and the ironic acuity of his intellect. But Mr. Brendel the writer does not command Busoni’s fullness of idiosyncrasy and worldliness. Rather, his achievement echoes that of Bernstein, whom he otherwise does not resemble. Like Bernstein, Mr. Brendel, speaking for music, has powerfully espoused a neglected repertoire: the piano sonatas of Franz Schubert.

Schubert, to be sure, has not been neglected at any point in Mr. Brendel’s lifetime. But his piano sonatas, with a few exceptions, were and are. From Mr. Brendel’s 2015 essay “A Lifetime of Recordings,” one learns with incredulity that Otto Erich Deutsch, who cataloged Schubert’s oeuvre, first heard the C minor Sonata—today esteemed as part one of a valedictory 1828 trilogy—when Mr. Brendel himself played it in Vienna in the 1960s. Rachmaninoff, it is said, did not even know that piano sonatas by Schubert existed. Though I was myself once a habitué of piano recitals, I have never heard in concert the Schubert sonata I would most like to command at the keyboard: the 40-minute A minor Sonata, D. 845, of 1825. It simply is not played.

As Mr. Brendel stresses, the late discovery of these works is a function of their perplexing originality: Compared with the Classical sonatas of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, or the Romantic sonatas of Chopin, Schumann and Brahms, they are uncategorizable. Charles Rosen (another noted pianist-author) nails this point in his dazzling “The Classical Style” (1971), whose penultimate paragraph concludes that Schubert “stands as an example of the resistance of the material of history to the most necessary generalizations.”

Mr. Brendel’s indispensable project has been to promote the eight Schubert piano sonatas composed in 1823 and after as a canon worthy to set beside Beethoven’s 32. He has recorded and re-recorded these works. He has tirelessly purveyed them in concert. What is more, what he has had to say about them may prove more memorable than his recordings and performances.

In the Schubert essays here collected, Mr. Brendel hones a metaphor that ceaselessly illuminates this protean composer: the “sleepwalker.” Using Beethoven’s decisiveness of form and sentiment as a foil, he showcases Schubert’s waywardness—a defining feature long misread as weakness. As opposed to Beethoven’s “inexorable forward drive,” Schubert can convey “a passive state, a series of episodes communicating mysteriously with one another.” As opposed to Beethoven the “architect,” Schubert “strides across harmonic abysses as though by compulsion, and we cannot help remembering that sleepwalkers never lose their step.” Next to Beethoven’s “concentration,” Schubert ”lets himself be transported, just a hair’s breadth from the abyss, not so much mastering life as being at its mercy.”

These observations will strike home to anyone who has listened closely to the Schubert sonatas or whose fingers have grappled with them and experienced at close quarters their chronic resistance to definitive formulation. Their ambiguities of sentiment and interpretation excite feelings of vulnerability. The A major Sonata, D. 959—for some, Schubert’s supreme achievement for the keyboard—begins at least three times. Only with the dreamy second subject, a Lied, does the first movement attain a recognizable expressive state. The second movement shatters into atonal chaos. An endless finale gradually establishes the first movement’s song mode as an anchoring poetic ingredient. Translating this music into words, Mr. Brendel finds “desolate grace behind which madness hides.”

One corollary, as with Mahler, is a musical state of existential duress unknown to Beethoven, a condition of unease or terror prescient of world horrors to come. Mr. Brendel: “In such moments the music exposes neither passions nor thunderstorms, neither the heat of combat nor the vehemence of heroic exertion, but assaults of fever and delusion.” Schubert presents “an energy that is nervous and unsettled . . . ; his pathos is steeped in fear.” An “impression of manic energy” points to “the depressive core of [Schubert’s] personality.”

Mahler himself wrote of Schubert’s “freedom below the surface of convention.” Mr. Brendel: “The music of these two composers does not set self-sufficient order against chaos. Events do not unfold with graceful or grim logic; they could have taken another turn at many points. We feel not masters but victims of the situation.”

The antithesis of Schubert’s delirium is the dream-finale, a child’s paradise with which the Sonatas in D major, D. 850, and G major, D. 894, conclude. The dream finale of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony is explicitly Schubertian: It quotes the D. 850 finale. The American composer-critic Arthur Farwell, documenting the intense Mahlerian vagaries of Schubert’s Ninth Symphony as conducted by Mahler in New York in 1910, proposed a mutuality of identity binding these twin Austrian pariah personalities nearly a century apart.

A surprise disclosure of “Music, Sense and Nonsense” is that Mr. Brendel’s collected Beethoven writings (110 pages) substantially exceed in length his Schubert writings (77 pages). But Beethoven requires no special advocacy. Busoni does—and I would have happily discovered more than the 17 pages here collected in appreciation of one of music’s most elusive geniuses: “There was the Faustian side of his intellect, which made him familiar with the melancholy of loneliness. As its counterbalance we find serene confidence, rarefied irony and ready surrender to grace.”

Finally, Mr. Brendel has long made a cause of Franz Liszt—after Schubert, his most productive topic, challenging incomprehension and neglect. If Liszt today is not really in need of a champion[ok? (“less needy” didn’t quite track w/the rest of the sentence)], that was not the case in 1961, when Mr. Brendel wrote the essay “Liszt Misunderstood”: “I know I am compromising myself by speaking up for Liszt. Audiences in Central Europe, Holland and Scandinavia tend to be irritated by the sight of Liszt’s name on a concert bill. . . . [They] project onto that performance all the prejudices they have against Liszt: his alleged bombast, superficiality, cheap sentimentality, formlessness, his striving after effect for effect’s sake.”

Understanding Liszt, for Mr. Brendel, is understanding the probity and nobility of the B minor Piano Sonata, not the inspired showmanship and ingenious panache of the “Don Juan” Fantasy. For him, Liszt’s is “the most satisfying sonata written after Beethoven and Schubert.” He takes issue with Charles Rosen, for whom the “Don Juan” Fantasy testifies to Liszt’s “profound originality,” including “almost every facet of his invention as a composer for the piano.” Busoni, in the preface to his edition of this demonic paraphrase of themes from “Don Giovanni,” accorded it “an almost symbolic significance as the highest point of pianism.”

“It is a peculiarity of Liszt’s music,” Mr. Brendel writes, “that it faithfully and fatally mirrors the character of its interpreter.” Applying this shrewd aphorism to Mr. Brendel himself: Performing Liszt, he was no swashbuckling Don Juan; nor did he seek to become one. Applying it to Mr. Brendel performing Schubert: He was the demented Wanderer of “Winterreise,” never the sweetly hapless lad of “Die schöne Müllerin.”

Mr. Brendel’s essays on the art of piano performance – that is, on his own art – prickle with assertions inviting prickly response. Many pianists will vehemently disagree with his vehement objection to the explosive first ending of the first-movement exposition of Schubert’s B-flat major piano sonata. Is this “jerky outburst” really “unconnected to the entire movement’s logic and atmosphere?” Well, that depends on how one reads the movement’s simmering left-hand trills. Given today’s free fall in musical literacy, this advisory component of “Music, Sense and Nonsense” will in any case speak to a small minority of music lovers.

Mr. Brendel himself is a man of wide-ranging interests. He is a published poet. As a young man he composed and painted. His personal history, growing up in Nazi Austria (he was born in Wiesenberg, now part of the Czech Republic, in 1931), shadows his distaste for musical dogma and also, one supposes, his susceptibility to Schubertian terror. Fantasizing another life story in a 2015 interview, he wished for “no wars, no memories of Nazis and fascists, no Hitler or Goebbels on the wireless, no soldiers, party members and bombs.”

The collected essays and lectures of Alfred Brendel occupy a classical-music bubble—and register no awareness that the bubble is shrinking fast. If this failure to deal with the fate of Schubert, Beethoven, and Liszt in the twenty-first century is a disappointment, it equally reassures us that an audience endures for musical ruminations that are learned but not esoteric, studious but not academic. Will Schubert’s sonatas be justly appreciated while a wide appetite for Schubert still exists? How long will it take for the D. 845 Sonata to take its rightful place in the piano pantheon—or will it remain forever off-stage?

August 27, 2016

The Future of Orchestras Part IV: Attention-Span

A colleague in Music History at a major American university reports that it has become difficult to teach sonata form because sonata forms transpire over 15 minutes and more. This topic – shrinking attention-span — is obviously not irrelevant to the future of orchestras.

My most memorable TV interview took place half a dozen years ago in a Southern city of moderate size. I was producing “Dvorak and America” for the local orchestra, assisted by Kevin Deas. We were roused from our hotel in the wee hours of the morning and conveyed to a studio complex. We found ourselves sitting on a pair of stools in a glare of light, idly watching someone forecast the weather. Quite suddenly I was asked a question by a twenty-something-year-old wearing a frozen smile, a lot of make-up, and a headset. I began to talk about Dvorak and watched her smile fracture. Her stressed features told me that she was being instructed to halt my stream of words – but I was not letting her intervene. I was actually on the verge of saying, “I know you would like me to stop talking now, but there are a few more things about Dvorak that I’d like your audience to know.” I had been speaking for fewer than two minutes.

Another such story: when I produce concerts I invariably ask that there be a post-concert discussion. This is often treated as a kind of concession. The frequent time-limit is thirty minutes. On one occasion, the presenter sat at a desk facing me. He had before him a series of large cards which he displayed for my benefit, one per minute: 30, 29, 28, 27 . . . The time-limit was paramount.

This fear of inducing boredom, pressing for simple thoughts and short sentences, is of course fatal to thoughtful verbal expression. But it is pervasive, and never more than today.

Imagine my surprise, several months ago, when an interviewer arrived at my apartment, sat alongside me on a couch with a small tape recorder, and invited me to speak as much as I pleased. Naturally, such a person – predisposed to actual conversation — asked penetrating questions without obvious answers. And then he turned our conversation into an hour-long radio show with interpolated musical excerpts.

The gentleman in question is David Osenberg and his award-winning radio show, on the WWFM classical network, is “Cadenza.”

Our conversation – which you can listen to here – pursued the question that has long preoccupied my professional life: what is the future of what used to be “classical music,” and what can be done to make it matter?

So David and I talked about my recent series of blogs about the fate of orchestras. I opined that fundamental change is both necessary and unlikely, at least as far as the “major” orchestras are concerned. I talked about better things happening in El Paso (at 15:00) and South Dakota (16:00), and at the Brevard Music Center (19:00) and DePauw University (21:30). Ultimately, I talked about the three DVDs PostClassical Ensemble has produced for Naxos, taking classic films from the 1930s and freshly recording the soundtracks. And David expressed the hope that WWFM could feature PostClassical Ensemble concerts on a regular basis, by way of exploring new ways of doing things.

Meanwhile, I continue to draw inspiration from the subversions of Ivan Fischer and his Budapest Festival Orchestra. Here is Stephen Moss, interviewing Fischer for The Guardian (Aug. 12):

“What Fischer wants to avoid above all is a sense of routine. ‘We work with intensity and in a very personal way. It is more like the way a string quartet works. I don’t say to the principal cellist: “Please a little softer.” I would say: “Come on Peter, what the hell are you doing?” It’s a different communication, much more personal. I immediately notice when their level of focus or concentration is not what it should be. I work much more like a theatre director would work with actors.’ . . .

“The orchestra [Fischer] founded is his lifelong passion; he also sees it as a ‘laboratory’ for orchestras of the future, offering flexibility, openness and a group of players that he encourages to develop as portfolio musicians rather than spending their lives as fixtures with the orchestra.

“’If you are a member of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, the great thing is that you are allowed a much more versatile musician’s life,’ he explains. He wants ‘individualists’ rather than ‘obedient, uniform soldiers.’ ‘For the future of music, it is better to develop the symphony orchestra as a more flexible organization that can embrace other musical styles. Now, we have a symphony orchestra that looks more or less like the one in Richard Strauss’s time. It’s already 100 years old. I don’t really think it will stay the same 100 years from now. The idea of a symphony orchestra must develop over time or it will become a museum.’

“He wants his ensemble to be able to play everything. ‘The conventional symphony orchestra leaves baroque repertoire to the period instrument orchestras and contemporary music to the specialized groups,’ he says. ‘Because we encourage the individual interests of musicians, we have a period instrument part of the orchestra, we have a chorus, we have a group playing Transylvanian folk music, another group working on jazz improvisations.’

“The aim is to keep both musicians and audience on their toes. He is known for his innovations: concerts where the audience chooses the pieces, which means they are played without rehearsal; encores in which the orchestra abandon their instruments and sing instead; operas where he does the staging himself . . . Every convention must be challenged.”

Amen to that.

It was my privilege to know Felix Galimir, a peerless chamber musician raised in the Vienna of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. When he came to the United States in the 1940s, Felix was confounded to discover that there was never enough time. In Vienna, there had been plenty of time.

Another distinguished musicians of my acquaintance, Lazar Gosman, played in Yevgeny Mravinsky’s Leningrad Philharmonic before emigrating to the US. He was amazed that, post-concert, symphonic musicians would hop in their cars and drive home. In Leningrad, they would congregate over vodka and talk.

As I previously reported, Ivan Fischer’s Budapest orchestra rehearses without a clock.

August 21, 2016

Virgil Thomson: Guerilla Tactics and Slapdash Judgments

In today’ s Wall Street Journal I review the new Library of America Virgil Thomson compendium. Here’s what I had to say:

The heyday of American classical music occurred around the turn of the 20th century, when most everyone involved assumed that American composers would create a native canon and that American orchestras in 2016 would play mainly American music. This vibrant fin de siècle moment also marked the apex of classical-music journalism in the United States. In New York, the most estimable critics were W.J. Henderson of the Times, Henry Edward Krehbiel of the Tribune, and the ubiquitous James Gibbons Huneker. All were active participants, not sideline observers.

One reason that music journalism declined after World War I was the criterion of “objectivity,” which removed critics from a world of composers, performers and institutional leaders that Henderson, Krehbiel and Huneker had knowingly inhabited. The grand exception, proving the rule, was Virgil Thomson of the New York Herald Tribune, who was a composer of consequence and an active conductor and who maintained close and significant working relationships with artists in other fields. Thomson’s 1967 autobiography, “Virgil Thomson,” reprinted in the Library of America’s new Thomson anthology, records theatrical enterprises alongside Orson Welles and John Houseman and interactions with a Parisian cohort that included James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. Edited by Tim Page, the new Thomson collection incorporates two additional books—“The State of Music” (1939) and “American Music Since 1910” (1971)—as well as an assortment of essays for the New York Review of Books and other periodicals.

Not included, because they were republished in a previous Library of America volume, are the hit-and-run Tribune reviews that made Thomson a notorious and influential guerrilla warrior from 1940 to 1954. These brilliantly informal inside jobs bore witness to the commercialized celebrity culture that classical music had become. It was Thomson who fingered Arthur Judson, a national musical power broker (running two orchestras and the leading New York concert bureau) who put business first and art second, and it was Thomson again who reduced the “educational” efforts of David Sarnoff’s NBC and RCA to “the music appreciation racket.” He called the violinist Jascha Heifetz “essentially frivolous” and considered the Philharmonic “not part of New York’s intellectual life.”

In his autobiography, Thomson explains: “The New York Herald Tribune was a gentleman’s paper, more like a chancellery than a business. During the fourteen years I worked there I was never told to do or not to do anything.” Notably, Thomson was not told not to continue composing and conducting. His favorable reviews of Eugene Ormandy, who programmed lots of Thomson’s music with the Philadelphia Orchestra, were part of the package. And he pursued an insouciant personal style that would never have been tolerated at the Times. His principles, he wrote, “engaged me to expose the philanthropic persons in control of our musical institutions for the amateurs they are [and] to reveal the manipulators of our musical distribution for the culturally retarded profit makers that indeed they are.” Another sally in his autobiography records that the Times’s “chronic fear of any take-off toward style came back to mind only the other day, when Howard Taubman, its drama critic, dismissed a play by the poet Robert Lowell as ‘a pretentious, arty trifle.’ ”

If re-reading Thomson’s feuilletons today remains a bracing experience, it must be emphasized that his larger efforts are compromised by know-it-all slapdash judgments and contentious aesthetic biases that are more forgivable and delectable in a daily newspaper, where they may be balanced by others’ accounts. The longer pieces collected here are studded with howlers, of which I will cite two bearing on a Thomson specialty: American opera.

Recalling the inception of the Metropolitan Opera on page one of “American Music Since 1910,” Thomson records that “for its first seven years, from 1882 to ’89, [it] gave everything, including Bizet’s Carmen, in German.” In fact, the Met began in 1883 as an Italian house and was ambushed by Germans from 1884 to 1891 before the box holders took it back. This issue of opera and language, as Henry Krehbiel (miscalled “Edward” by Thomson in a paragraph extolling fact-checking at the Herald Tribune) acutely appreciated, would prove crucial to the failure of American opera in the decades to come.

A second example: Writing in 1962, Thomson called George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” an “opéra comique, like Carmen, consisting of musical numbers separated by spoken dialogue.” But Gershwin wrote sung recitatives. The dialogue one sometimes encounters in “Porgy” was added after Gershwin’s death. Thomson himself loudly reviewed “Porgy” at its 1935 premiere. He denigrated Gershwin as a gifted dilettante—the same judgment he had applied to Charles Ives. A chronic Francophile, Thomson keyed on the professionalism instilled by his Paris-based teacher Nadia Boulanger, who also taught Aaron Copland and countless other Americans whose music was more kindred to Thomson than “Porgy” or Ives’s “Concord” Sonata. A 1962 encomium to Boulanger is the warmest and tenderest thing in the Library of America collection; the usual temperature of Thomson’s prose approximates that of an ice-cold shower.

Thomson’s assessment of Ives, in a chapter from “American Music Since 1910” called “The Ives Case,” makes strange reading today. A breathtaking Thomsonian generalization—“an artist’s life is never accidental, least of all its tragic aspects”—predicates a breathtakingly severe verdict: that all of Ives is compromised by “a divided allegiance.” By dividing himself between composition and the life-insurance work he pursued to earn a living, Thomson argues, Ives never mastered a musical calling. From Thomson’s essay one would never glean that, even as a student, Ives could craft an exemplary German Lied (“Feldeinsamkeit”). Rather, a “homespun Yankee tinkerer,” Ives wrote songs that “will not, as we say, come off.” His exemplification of “ethical principles and transcendental concepts,” Thomson opines, seems “self-conscious,” “not quite first-class.”

Whatever one may make of such judgments, what seemed Germanic hot air to Thomson is what for many today most gauges Ives’s greatness. Those “ethical principles” and “transcendental concepts” are what convey a moral afflatus equally found in Bruckner, Mahler, Sibelius and Shostakovich—also on Thomson’s list of windbag composers. With Germanic “Innerlichkeit” (or inwardness) he will have nothing to do: Only Thomson could have likened its most famous podium practitioner, Wilhelm Furtwängler, to Arturo Toscanini, who “streamlined” music in favor of surface affect.

Thomson believed that the German influence on such American composers as Ives, Edward MacDowell and George Chadwick was toxic. Are Chadwick’s symphonic works merely “a pale copy of . . . continental models”? I would not say that of Chadwick’s effervescent “Jubilee” (1897), with its whiff of “Camptown Races.” Did Thomson even know much of Chadwick’s music? It is doubtful. But his assumptions were echoed in the American-music narratives popularized by Copland and Leonard Bernstein, both of whom also dismissed Chadwick and questioned the professionalism of Ives and Gershwin.

Among the most substantial occasional pieces in the present collection is a 1965 assessment of books about Debussy, Bizet, Berg and Webern for the New York Review; it provides a concise exegesis of Thomson’s aesthetic predilections. Debussy was, he wrote, the “most original” 20th-century composer, and French literature was his inspirational fount. His “most vibrant pages are those in which a literary transcript of some visual or other sensuous experience has released in him a need to inundate the whole with music. This music, though wrought from a vast vocabulary of existing idiom, is profoundly independent and original. . . . None of it really sounds like anything else. It had its musical origins, of course; but it never got stuck with them; it took off.”

Debussy’s highest flight is the opera “Pelléas et Mélisande” (1898), in which “for the first time in over a century (or maybe ever) a composer gave full rights to subtleties below the surface of a play. . . . The sensitivity with which the whole is knit . . . never again produced so fine a fabric.” The only “runners-up” to “Pelléas” among 20th-century operas are Berg’s “Wozzeck” and “Lulu.” Berg depended on his German musical forebears “to guide him through the dark forests of abnormal psychology.” Owing, Thomson confides, to a “perverse fascination with the Germanic view of music as something strictly for scholastic temperaments,” he undertakes a review of Willi Reich’s then-newly translated Berg biography. Both the book and its subject, he says, embody “Germanic types” who “think in simplified alternatives—black or white, right or wrong, our team against all the others in the world.”

A slightly earlier New York Review piece, “How Dead Is Arnold Schoenberg?,” supplements these views. Schoenberg’s letters are said to distill the self-portrait of “a consecrated artist, cunning, companionable, loyal, indefatigable, generous, persistent, affectionate, comical, easily wounded, and demanding.” Schoenberg is the characteristic German “for whom a certain degree of introversion was esteemed man’s highest expressive state.” It is good to lay the cards on the table.

And what of Thomson’s own place in music history? The readings at hand amass a shrewd self-assessment, becomingly modest yet laced with piercing insinuations of self-regard. It is only appropriate that Thomson lavishes attention on his two operatic collaborations with Gertrude Stein. “Four Saints in Three Acts” (1934) and “The Mother of Us All” (1947) embellish the tiny American operatic canon. For those who love the artful innocence of Erik Satie, they are a sublime achievement; for the rest of us, they embody a taste rarefied yet readily accessible.

Thomson was also one of the best American composers for film (a topic somewhat skirted in his autobiography). His scores for the classic documentaries “The Plow That Broke the Plains” (1936), “The River” (1938) and “Louisiana Story” (1948) are outstandingly fresh, organic in unexpected ways. For a cavalcade of cars fleeing drought-infested farms—the climax of “The Plow”—Thomson furnishes a divine habanera. Elsewhere his patchwork of hymns and popular song strikes an American note both authentic and original. When Thomson claimed to have preceded Copland in concocting an American idiom combining “simplification” and “folk-style tunes,” he was merely telling the truth.

Finally, Thomson embodies an iconic American life story. Born in Kansas City in 1896, seasoned in Paris, ultimately a legendary denizen of Manhattan’s Chelsea Hotel, he combined vernacular New World whimsy with the refinements of Old World high art. He traced his obstreperousness to “the Booth Tarkington-George Ade-Mark Twain connection.” In his lifetime, this gadfly spirit made Thomson a necessary voice. Posthumously, he utters fearless but fallible understandings based on formidable knowledge and experience and equally formidable eccentricities of feeling and opinion. He is more a guide to his own time and place than a sage analyst or observer of timeless truths.

One can feel grateful for this Library of America volume and yet believe that a greater service could be rendered by anthologizing American musical journalists from an earlier era. Henderson’s 2,500-word Times review of the premiere of Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony remains a masterpiece of probing approbation, with one of the subtlest descriptions of the central Largo ever conceived. Krehbiel’s 4,000-word Tribune review of the American premiere of Strauss’s “Salome” remains a masterpiece of moral opprobrium, as plausible today as the day it was written. Huneker’s account, in his autobiography, of an inebriated evening with Dvorak (“Such a man is as dangerous to a moderate drinker as a false beacon is to a shipwrecked sailor”) remains among the most colorful portraits of any composer ever penned. A full dose of such writings would open wide a window on an American past not sufficiently remembered—not least by Virgil Thomson.

August 20, 2016

Virgil Thomson: Guerilla Tactics and Slapdash Judgments

In today’ s Wall Street Journal I review the new Library of America Virgil Thomson compendium:

July 17, 2016

The Future of Orchestras, Part III: Bruckner, Palestrina, and the Rolling Stones

“Would the New York Philharmonic sing Palestrina?” – the question posed by my previous blog – arose from a recent performance of Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony in which the musicians did precisely that. The conductor was James Ross, whose University of Maryland Orchestra breaks the mold. Jim writes: #

“’Sense of occasion’ is absolutely the goal; that there are unique reasons why a certain program is taking place with this orchestra in this community on this particular day . . . Concerts should be singularly memorable and unrepeatable. No performance of the Rolling Stones on tour fell short of that goal despite their getting up the next day and doing ostensibly the same concert again each night. That’s why they had groupies! . . . If the only reason some people still come to classical concerts is to hear a specific piece or pieces played live rather than at home, I suspect that specialty audience is now officially well on the way towards extinction. The ones we need to curate are those who come because they expect that something is about to happen, that something about the live experience will offer up ‘a sense of moment’ that will allow unexpected connections and recognitions to unfold for each listener. Those seeking the ‘moment’ are sorely and sadly disappointed at most of our concerts, I fear. This is on us conductors to change by unleashing and challenging those in front of us first, and then helping those behind us to understand why we’re doing what we do, what motivates us. Addressed well, I think just about any audience will give just about any piece a fighting chance of being heard and appreciated.” #

So for his Bruckner Fifth – a work little known to his musicians or his College Park audience — Jim began with a little talk about what he was doing: #

http://www.artsjournal.com/uq/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/1-Audio-Track.mp3

Then the orchestra sang Palestrina: #

http://www.artsjournal.com/uq/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2-Audio-Track.mp3

The University of Maryland Concert Choir furnished further Palestrina excerpts before each of the symphony’s movements “to give a musical and visceral sense of the fountain from which Bruckner’s sacred symphony springs.” Finally, for the refulgent closing reprise of the chorale theme, Jim had the Concert Choir (in a balcony) sing along to the text of Kyrie Eleison. It sounded like this: #

http://www.artsjournal.com/uq/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/04-Track-04-1.mp3

This enthralling experiment ignites memories of another – Bruckner’s Ninth as rendered by the Pacific Symphony (I’m the Artistic Advisor) five years ago. Carl. St. Clair, the orchestra’s remarkable conductor, is a devout Catholic. The composer with whom he bonds completely is Bruckner. Carl’s humility, and also a deficit in opportunity, have long deferred experiences with this composer that Carl was born to undertake. #

Carl’s Bruckner 9 was his first. The work and the composer were virtually unknown to his Orange County audience. Carl reads this final Bruckner opus as a gripping religious narrative of trial and redemption. For him, the pounding Scherzo signifies a crucible of carnal temptation which the dying composer must endure. The Adagio’s three cataclysms signify a further rite of passage recalling the agonies of Christ. The coda’s beatitude is a leavetaking literally envisioned: the apocalyptic visions sited, the radiant halo of divinity towards which the humble believer ascends and into which he is absorbed. #

Carl wanted to begin the evening by imparting this narrative, but without giving the work away or diminishing the orchestra as an audio-clip tool. So he engaged Paul Jacobs to play the necessary excerpts on the organ. The first half ended with Paul performing Bach’s St Anne Fugue (gloriously). It began with a sung processional by a chorus of Norbertine Fathers. #

Carl’s reading of Bruckner 9 was intensely transporting. He lived the piece. Segerstrom Hall has a choral loft; the listeners there face the conductor. In two of our three performances, there was a medical incident during the Adagio – someone there passed out and needed professional attention. On the second such occasion, Carl had to stop the symphony and ask the audience to pray. I am certain that these events were not coincidental. #

Not every Bruckner performance requires an act of contextualization. I vividly remember, at Carnegie Hall, No. 4 with Sergiu Celibidache and the Munich Philharmonic, and No. 8 with Eugen Jochum and the Bamberg Symphony at the very end of Jochum’s life. Both these conductors established a sense of occasion the moment they set foot on the stage. Celibidache was an acquired taste; you had to listen on his own terms. I knew I would be hearing a slow-motion Bruckner 4 (it lasted 80 minutes) and prepared by getting stoned. The Jochum Bruckner 8 was wholesome, purged of the demonic. In the opening of the Adagio, he conjured colors never before heard. None of the Bruckner Jochum recordings I’ve come across are anything like what I encountered on this magical occasion. #

Celibidache and Jochum were great Bruckner conductors galvanizing an audience predominantly familiar with Bruckner. Those days are mainly gone. What will ultimately impel orchestras to finally rethink the concert experience? Jim Ross writes: #

“Can anything more be expected of the orchestra as an institution if the job description of its players stays the same? The human force of 100 players either encouraged or denied the opportunity to have the orchestra be a place of personal growth, experimentation, and creativity is just too strong to fight. It will come from them and with them, or it won’t come at all, in my opinion.” #

My friend Mark Clague at the University of Michigan, an exceptional educator, said the same thing in his June 30 response to my initial mega-blog: #

“It’d be best, I think, if the real driver of change will be the imaginative career goals of music students (and by extension future musicians). If students come to school or develop a broader definition of what success could mean, they will demand an education that leads toward this success — say as experts in community engagement. At this point, we’re in something of a vicious circle where success (say at a traditional orchestral audition) is defined by performance skill alone and thus schools are caught between narrow and broader paradigms. Because auditions are inhumanly competitive, schools focus all educational activities prior to winning an audition on such singular success. This leads to the collegiate orchestra, indeed the whole music school on some level, focusing only on teaching traditional repertoire that will appear on such auditions. The collegiate orchestra as a broad, flexible educational tool that you envision would be a powerful innovation . . . Short of a traumatic crisis, it’s hard for me to see change here coming from the top, however. It needs to come from our students. They vote with their applications, their enrollments, and the classes that they choose to take. I hope their courage and openness will allow us all — from professors to professional musicians — to embrace these opportunities.” #

I agree – the more the musicians know about the cultural institution of which they’re part, the more they participate, the better for everyone. Returning from my three weekends of music conferences, I rebuked myself for never having thought to invite any PostClassical Ensemble musicians onto our board. So beginning next season the PCE board of directors will include our principal trumpet, Chris Gekker, and our principal percussionist, Bill Richards. #

Bill anchored last season’s percussion program featuring Lou Harrison’s sui generis Concerto for Violin and Percussion (which we both performed an recorded with Tim Fain). Chris (known to all brass players) has lent distinction to countless PCE performances. I am thinking especially of the Gershwin Concerto in F (the second movement’s divine blues) and of our new Naxos DVD of Redes. Next spring, he takes part (with Alexander Toradze) in Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 1 (which began life as a trumpet concerto). #

The same Shostakovich program features Edward Gero (a leading DC actor) as Shostakovich in a 20-minute Theatrical Interlude. We’ll also explore the relationship between Shostakovich and Mieczyslaw Weinberg. The larger topic is “Music Under Stalin.” #

The season begins with “Mozart, Amadeus, and the Gran Partita” – our way of contextualizing the most famous of all wind serenades. The concert will be hosted by Antonio Salieri. The participants include the Washington Ballet Studio Company. We’ll explore how Mozart transformed a genre previously associated with gossiping, flirting, and courtly minuets. The idea is to create a sense of occasion. #

PS – in 2017-18 we undertake an immersion experience – “The Russian Experiment 1917-2017” – featuring the pianist Vladimir Feltsman and the composer Victor Kissine. The repertoire includes Alexandr Raskatov’s The Seasons Digest – which asks the musicians of the orchestra to sing. #

July 4, 2016

The Future of Orchestras (Cont’d): Would the Philharmonic Sing Palestrina?

When Doug McClennan persuaded me to start blogging in 2006, I was a newcomer to electronic media and also a skeptic. I read books. It write long. I do not tweet and rarely check Facebook. #

Frankly, the consolidated thread of considered comments elicited by my mega-blog on the future of orchestras has taken me by surprise. These are informed comments from inside the orchestra world. (I trashed a few that were not.) I have also been deluged with emails whose content must remain private. They, too, register the thoughts, frustrations, and anxieties of musicians, educators, and administrators. #

I would like to particularly draw attention to the latest posting – the one from Chris Gekker, who happens to be principal trumpet of my PostClassical Ensemble in Washington, D.C. All brass players know his name. Chris is a trumpeter with lyric bent all his own. He is also the beneficiary of decades of orchestral experience, often with colleagues and conductors of the highest distinction. (It is he who plays the ravishing trumpet solos on PostClassical Ensemble’s new Redes DVD.) #

I was already familiar with the memorized and choreographed Debussy performance, referenced by Chris, of Jim Ross’s remarkable University of Maryland Orchestra. But I had no idea that Jim had his players sing Palestrina as a preface to Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony – a subversive inspiration kindred to Ivan Fischer’s singing Budapest Festival Orchestra (cf my mega-blog). #

As is well-known, when Leonard Bernstein attempted some Cage with the New York Philharmonic in the 1960s, the players collectively misbehaved when invited to collectively improvise. But six seasons ago, the same New York Philharmonic plainly enjoyed doing the unexpected during a terrific performance of Ligeti’s Grand Macabre. #

Would the Philharmonic sing Palestrina? I ask this question in all seriousness. Try to imagine the impact – on the players; on the public. #

As I have countless times observed, our orchestras have failed to innovate. The first permanent, full-time American orchestra to reside in one place (Theodore Thomas’s orchestra travelled) was Henry Higginson’s Boston Symphony, invented in 1881. In terms of format, ritual, and purpose, today’s BSO concerts are no different from Higginson’s more than a century ago. Meanwhile, the world has changed. I would call this evidence of institutional stagnation. #

By the way, Ivan Fischer is guest-conducting the New York Philharmonic this coming season. #

June 21, 2016

STORM WARNINGS: THE FUTURE OF ORCHESTRAS

— I — #

I recently spent the three consecutive weekends speaking at conferences pertinent to the fate of America’s orchestras. #

The first, at Grinnell College, was sponsored by the American Association of Liberal Arts Colleges. The topic was reforming music curricula. The second, at the University of South Carolina, was a “summit” sponsored by the College Music Society. The topic was the same. The third, in Baltimore, was the annual conference of the League of American Orchestras. #

As the only person to attend even two of these events, let alone all three (a fact in itself significant), I find I have a lot to think about. I foresee a perfect storm moving at high velocity. #

Both academic conferences endorsed the same new template. Its advocates are progressive educators – the ones ready for change. I have no doubt that something resembling the changes they endorse will happen. It’s just a question of how soon. #

One feature of the new template is removing “Orchestra” from the center of things and repositioning it to the side as an ancillary activity, possibly optional. Instead, students will be encouraged to form their own smaller ensembles. Or they will perform in ensembles practicing non-Western genres. Or they will find other opportunities to perform. #

In general, there is a feeling that students today have creative propensities that must be respected and welcomed. The orchestra experience falls outside this purview. Also, Western classical music will no longer be privileged in the teaching and practice of Music. And there is a pervasive move to require improvisation and composition as aspects of instrumental instruction. #

Another new area of primary emphasis is music as an agent of social responsibility. #

In other words: the young musicians orchestras most need will not gravitate to orchestras. Instead, orchestras will get the blinkered conservatory graduates who don’t care about the institutional life of an orchestra – who will dutifully rehearse and perform. It therefore becomes more than ever incumbent upon orchestras to empower musicians to more fully participate in an expansive institutional mission. #

An interesting question is whether orchestral reform can occur at music schools and conservatories. My impression is that “Orchestra” is perceived as a bastion of conservatism and that campus conductors are perceived as unlikely partners in progressive curricular change. They cling to “professional training” – traditional repertoire and formats – for non-existent jobs. Could not the campus orchestra be rethought as a timely experimental laboratory? “Orchestra” could impart the history of conducting, the history of performance practice, the institutional history of the orchestra. It could generate cross-curricular study of a symphony or composer. It could be all kinds of things that it is not. #

— II – #

These were the thoughts I brought to the League conference in Baltimore. What I discovered there was the same impressive sense of urgency I had encountered among the educators. But here it was channeled toward a single, focused goal: creating a “pipeline” that would send gifted African-American and Hispanic instrumentalists into scarce and coveted orchestral jobs. The ethnic composition of orchestras – to date, overwhelmingly white – would begin (if barely) to mirror that of the communities they serve. Because this effort is mightily supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (an invaluable and influential bulwark for innovation in the symphonic field), it seems likely to bring results. The urgent question on the table becomes: will there be further change? #

The conductor Theodore Thomas, who more than anyone propagated the “symphony orchestra” as an American specialty, prophetically preached: “A symphony orchestra shows the culture of the community, not opera.” By the 1920s, in American cities large and small, the local orchestra had become the bellwether of civic cultural identity. After that, the world changed and orchestras did not; a Boston Symphony concert, ca. 1890 (before radio, before recordings, before tidal social and demographic upheavals), was more or less the same as the symphonic concerts we hear and see today. (I have told this story in detail in my Classical Music in America: A History.) That orchestras no longer “show the culture of the community” rightly preoccupies the League. #

There is a schizoid elephant in the room. As everyone in the orchestra business knows, musicians and administrators do not adequately experience joint ownership of the enterprise at hand. The players rehearse and perform at arm’s length from the front office. They submit to the authority of the music director. They guard work rules written to protect their interests; they strive for higher pay and more services. They little participate in the crucial activities that keep any orchestra alive: fund-raising and marketing. Their artistic input is usually negligible at best. Their purview is dangerously skewed. #

The tensions between the players and the staff may be strident or subtle, but they are pervasive. Changing the racial composition of a law school makes immediate sense; it will impact the field. Changing the racial composition of an orchestra won’t critically impact unless other changes are ignited. This point circles back to the educators at Grinnell and the University of South Carolina: the most talented young musicians tend to be the most creative. They will not aspire to sit obediently in orchestra seats. #

— III – #

Nothing is more informative about the caliber of an orchestra than the listening behavior of the musicians when others are playing and they are not. Are they keenly attuned or staring into space? #

In my experience, the keenest listeners are to be found in certain European orchestras – such as the Berlin Philharmonic (which picks its conductors; whose principal players rotate). And then there is the Budapest Festival Orchestra, the members of which are picked by its conductor: Ivan Fischer. I have never encountered an orchestra that manifests a more meddlesome active intelligence (unless they are conductorless chamber orchestras like Gidon Kremer’s peerless Kremerata Baltica). Fischer’s players may burst into song in the midst of a Dvorak symphony (I am not making this up). For Beethoven’s Pastorale Symphony, Fischer may situate the solo winds around a potted tree. He may choose to begin a rehearsal by having everyone play some Bach for fifteen or twenty minutes. Or the orchestra may learn an Argentine song for use as an encore in Buenos Aires. In fact, Budapest Festival Orchestra encores are often sung. (I cannot imagine a more democratic bonding experience.) The communal intensity of the Budapest Festival Orchestra is instantly tangible. #

Fischer’s hiring practices and work rules would be unthinkable in America: the musicians hold two-year contracts and rehearse without a clock. And yet I do not doubt that there are young Americans who would sooner play with Fischer than win a seat in Franz Welser-Most’s Cleveland Orchestra. #

I do not know if Ivan Fischer has ever been discussed at League of American Orchestras conference. But a Youth Orchestras session, at the League’s Baltimore conference, brought Fischer’s practices instantly to mind. The discourse was electrifying – here, serving inner-city pre-collegiate instrumentalists, were American orchestras fully in ferment. What I heard connected directly to what progressive music educators are saying: the creative impulse must be seized. A new repertoire, a new sound, a new disposition of instruments, a new concert experience must be countenanced. #

I left that room with many questions. What about our nation’s summer orchestral camps? Will they, too, take a lead? Or will they continue to replicate a dying model at odds with present-day realities? #

And there is the nagging question of “excellence.” Museums can maintain the canon by simply keeping Rembrandt on the walls. But inspired readings of Brahms symphonies are increasingly hard to come by. Skill is a prerequisite. So is engagement. These are priorities that must be squared with “showing the culture of the community.” #

Our orchestras are facing a perfect storm moving at high velocity. How fast can they adapt? The most adaptive orchestra I know is the South Dakota Symphony. Its music director, Delta David Gier, began his tenure by initiating a Lakota Music Project linking to nine Indian reservations; most recently, he took Dvorak’s New World Symphony to Native American audiences in remote Sisseton. With its enterprising nine-member “core,” the South Dakota Symphony is positioned to maximize personal interaction with Sioux Falls residents and institutions. #

The Detroit Symphony, energized by a crippling strike, is another orchestra making strides toward showing the culture of the community. That Detroit is the host orchestra for the League’s 2017 conference, next June, is auspicious. The League’s sense of urgency will likely be sustained. Will the conference again identify a single focused goal? How about expanding the role of individual musicians in every facet of orchestral life? #

— IV – #

The historian in me cannot resist a brief postscript. Here are four vignettes from the early history of the American orchestra: #

1.Henry Higginson, who invented, owned, and operated the Boston Symphony, and also built Symphony Hall, was a colossal visionary. After service in the Civil War, he ran a plantation for freedmen in Georgia. Upon inaugurating the BSO in 1881, he insisted that there be twenty-five cent tickets available for all concerts. Even in 1881, this was a sum so small that other Boston orchestras complained that Higginson’s ticket prices (personally subsidized by Higginson, who also paid all salaries) would drive them out of business. Breaking with Brahmin Boston, Higginson was a philo-Semite, ready to hire a Jewish music director (Mahler and Bruno Walter were seriously considered) decades before the trustees of the New York Philharmonic rejected the possibility of a Jewish conductor post-Toscanini (for this incredible story, see my Classical Music in America, pp. 423-424), and the trustees of the Boston Symphony looked askance at Leonard Bernstein’s Jewishness post-Koussevitzky. #

2.In Brooklyn, the major presenter of symphonic concerts was a woman: Laura Langford, president of the Seidl Society. There were many more Seidl Society concerts than there were New York Philharmonic concerts across the river. The conductor was the same: Anton Seidl, Richard Wagner’s most intimate protégé. Langford charged as little as fifteen cents for Seidl Society concerts, most of which took place fourteen times a week at Coney Island. She prioritized bringing working women and African-American orphans to the seaside Music Pavilion. Seidl himself loudly championed access for working men and women. Langford and Seidl also prioritized hiring leading female pianists and violinists. And, over the objections of the Seidl Orchestra, they hired a female harpist (whose engagement was made a public cause). #

3.In Manhattan, Antonin Dvorak chose an African-American, Harry Burleigh, to be his personal assistant at the National Conservatory of Music. Dvorak conducted his own transcription of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” at Madison Square Garden in 1894 with an African-American chorus, a racially mixed orchestra, and two African-American soloists: Burleigh and the “Black Patti,” Sissieretta Jones. Burleigh went on to become the person most responsible for turning spirituals into art songs. #

4.Henry Krehbiel, the dean of New York music critics and Dvorak’s most important champion in the press, endorsed Dvorak’s conviction that “Negro melodies” would be the fundament of a future American music. He wrote the first book-length study of plantation song. At the 1893 World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago, he did not gawk at the African “Dahomians,” as others did, but admired the rhythmic sophistication of their songs and dances. He also eagerly promoted study of Native American song. #

Higginson, Langford, Seidl, Dvorak, and Krehbiel tirelessly extolled the moral properties of music. They understood art as an instrument for social reform both timely and timeless. The early history of the American orchestra is a history of ceaseless innovation. #

June 16, 2016

Musical Films

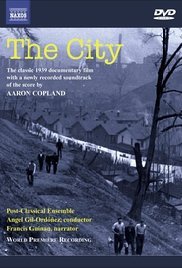

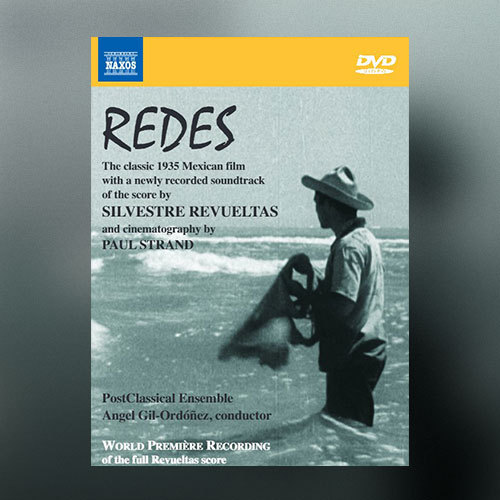

With our newly released Redes DVD, PostClassical Ensemble completes its Naxos quartet of classic 1930s films with freshly recorded soundtracks. #

The scores for these four films – the others are The Plow that Broke the Plains, The River, and The City – are among the most distinguished ever composed for film. The composers are Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, and Silvestre Revueltas. What is more remarkable, all four films are music-driven to a degree rarely approachable today. #

While sound films, The Plow, The River, and The City are famous documentaries shot without sound. This is because in the thirties sound equipment was not readily portable in the field. No ambient sound was added. Rather, the three soundtracks comprise formidably original symphonic music and sonorous blank verse narration, sans dialogue. The result is a unique but short-lived high-art genre. #

Redes was mainly shot without sound. Most of the ambient sound and dialogue were added later. But the film’s iconic sequences were without exception shot without sound, and no dialogue or ambient sound were ever added. #

All four films feature powerful and powerfully autonomous music tracks. The music does not merely mimic the action. Nor does it merely drive the narrative trajectory. Rather, it acquires a rare degree of autonomy. #

When at the end of The Plow a sad parade of cars escapes failed farms victimized by a legendary drought, Thomson supplies an ironic habanera. Copland’s “Sunday Traffic” sequence, in The City, juxtaposes a massive traffic jam with an ebullient accelerating march. #

For the child’s funeral in Redes, Revueltas composes a self-sufficient dirge based on a minor-key leitmotif he triumphantly reprises in the major at the film’s close – a signature of redemption for the oppressed fishermen whose plight the film exposes. #

Significantly, these are not films to which music was added after they were shot and edited. Pare Lorentz recut The Plow upon receiving Thomson’s startlingly original score. For The River, Thomson was part of the creative team from the start. The same was true of Copland with regard to The City. #

In the case of Redes, Revueltas began work on his music before seeing any rushes. It’s not surprising that this unsettled Paul Strand, the film’s legendary cinematographer. Revueltas also had the final say after Strand and the film’s directors – Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gomez Muriel – were no longer around. It would be hard to imagine a film project that more empowered its composer. #

It bears mentioning that the four films influenced one another. Pare Lorentz directed both The Plow and The River, and wrote a script outline for The City. Paul Strand shot Redes and was one of four cinematographers for The Plow. Willard Van Dyke took part in The River and The City both. #

Aaron Copland reviewed Redes for The New York Times – and we can infer that both Redes and the two Lorentz films inspired his work on The City. Copland was then off to Hollywood, where he scored five films and won an Academy Award. But none of those film scores nearly attains the caliber or impact of his music for The City. #

In fact, after 1940 — with the full advent of sound and of more mobile outdoor sound equipment – little comparable to The Plow, The River, The City, or Redes was ever again likely to materialize. I can think of rare exceptions, such as Ken Russell’s amazing 1983 film version of Holst’s The Planets, in which not a single image is planetary. But that, too, is a silent film with music – an anomaly. #

Naxos plans eventually to package PostClassical Ensemble’s DVDs as a single boxed set – memorializing a landmark effort in the history of music and the moving image. #

June 8, 2016

Bach on the Piano

I have a good friend who’s a magnificent pianist, maybe sixty years old. #

Some years ago, my friend remarked: #

“You know, when we were young, there were a lot of major pianists. Everyone knew who they were: Horowitz, Serkin, Arrau, Michelangeli, Richter, Gilels, Pollini, Kempff, Rubinstein [I cannot replicate his full list]. They were all different, of course. But in every case you could understand why they were major pianists.” #

“Except for Pollini,” I said. #

“Except for Pollini,” he agreed. #

“Nowadays,” my friend continued, “anyone can be a ‘great pianist.’” #

“It’s a complete crap-shoot,” I said. #

“A complete crap-shoot,” he agreed. #

Well, not completely. It helps a lot to be very, very young. Whereas in general older pianists are better pianists. #

I found myself remembering this exchange a few weeks ago when I received an email from Sergei Schepkin inviting me to his New York recital on June 7. I remembered Schepkin from a Rachmaninoff festival I helped to curate in Pittsburgh in 2009. I knew he was a mature civilized pianist. These days, that’s saying a lot. I instantly wrote back accepting his invitation. #

It turned out that Schepkin’s program was all-Bach: three partitas. The venue was the new Steinway Hall on Sixth Avenue. It houses a basement recital hall that’s elegant and intimate, excellent in every way. #

My first exposure to the Bach partitas was a recording by William Kapell of the D major Partita. This would have been around 1960, when I was in high school. In retrospect, Kapell’s faceless, unpianistic Bach marks a nadir. But it wasn’t his fault. That was a time – in the US, at least — when the Bach keyboard standard was set by Wanda Landowska, playing her harpsichord. Pianists mainly shunned Bach, or approached him tentatively, on tiptoe. #

Then came Glenn Gould and a new kind of piano Bach, galvanizing in its way, but still remote from exercising the full resources of the instrument. #

Wilhelm Kempff’s DG recording of Bach’s G major French Suite was my Bach epiphany, ca. 1980. Kempff pedaled the G major cadence of the Loure right into the opening measures of the Gigue, producing the musical equivalent of a shower of stars (at 13:22). My notion of Bach on the keyboard was changed forever. #

Next I came to Edwin Fischer’s titanic Bach and discovered that Kempff was part of a performance tradition simply unknown in America – call it Bach with pedal. Like Kempff, Fischer’s Bach was a sonic kaleidoscope. Unlike Kempff, Fischer was heroic. His version of the Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue is one of the most justly famous Bach recordings ever made by a pianist. #

Richard Wagner, in his indispensable treatise “On Conducting” (1869), describes how his frustrations with “serenely” featureless Bach keyboard performances, innocent of “somber German Gothicism,” were relieved when his friend Franz Liszt assayed the Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp minor from Book I of the Well-Tempered Klavier. “Now, I knew what to expect from Liszt at the piano; but I had not expected anything like what I came to hear from Bach, though I had studied him well; I saw how study is eclipsed by genius.” If you’d like some idea what Liszt’s performance might have sounded like, listen to Fischer’s recording and pay particular attention to the climax of the fugue. #

Another classic Bach piano performance that’s miraculously pedaled is Ferruccio Busoni’s pealing 1922 version of the C major Prelude and Fugue from Book I. Listen (with headphones) to the mystic pedal point he creates (at 3:42) in the final measures. #

Today, at last, all performance options are open. Typewriter Bach is a thing of the past. Two pianists I especially admire in the Partitas are Vladimir Feltsman and Jeremy Denk. Both go their own way. And so does Sergei Schepkin. I would say his keyboard Bach is mutually influenced by the agogics of the harpsichord and the resources of the piano (dynamics and voicing more than pedal). And he is an acute, active listener who attends equally to the melodic and the contrapuntal. I have no idea if the ornaments he adds – sometimes liberally, sometimes not – are rehearsed or spontaneous. What matters is that they sound improvised on the spot. #

And so Bach today affords a rare opportunity for performers of composed music. The choice of style, even the choice of instruments, is completely open-ended (or should be). Bach interpretation may never be standardized again. All we need is another Edwin Fischer. #

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers