Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 25

June 19, 2018

El Paso, Kurt Weill, and Tornillo’s Tent City

Readers of this blog may remember my last filing from El Paso – a “Kurt Weill’s America” festival, part of the NEH-supported “Music Unwound” consortium I direct, that ignited a week of discussion and debate about immigration past and present.

My most memorable experience that week was visiting Eastlake High School, in a semi-rural colonia, and telling 3,000 students about Weill, Walt Whitman, and Pearl Harbor. Weill’s immigrant’s response to FDR’s declaration of war on Japan, setting three Whitman Civil War poems, transfixed these remarkable young people. Mainly Mexican-American, they evince no sense of entitlement. When I was finished, the school chorus asked to sing for me. They chose “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

As I previously wrote:

“The quarterback for the El Paso Weill festival was Frank Candelaria, who as Associate Provost at the University of Texas/El Paso [UTEP] has the vision and persistence to make big things happen. Frank is an El Paso native, the first member of his family to obtain what is called ‘higher education’ — Oberlin and Yale. He left a tenured position at UT/Austin to return to El Paso five years ago. He expected the Weill festival to catch fire in El Paso, but the intimacy with which it penetrated personal lives took him by surprise. On the final day he said to me: ‘I learned a lot about my own city and how strongly people identify as Americans.’”

About a week ago, my issue of the Kurt Weill Newsletter arrived in the mail. It may well be the only classical-music magazine of quality we have left in the US. My blog about Weill in El Paso was there reprinted, with a full page of comments by students and participants. A UTEP student named Toni Torres wrote: “These projects on Kurt Weill gave me a new perspective on my citizenship. I need to be doing way more for my country and its music.”

No sooner did I read those words than I learned that Tornillo – one of the three colonias to which Candelaria has been bringing “Music Unwound” programs featuring UTEP faculty members and visiting artists — is to be the site of a tent city for children separated from their parents as a punishment for crossing the border illegally. Temperatures in Tornillo were predicted to shortly reach 105 degrees.

UTEP is a kind of miracle, an embodiment of the American Dream. More than 80 per cent of the students are Hispanic. More than 90 per cent are local. Any person with a high school diploma is accepted for admission. It inculcates high values that used to be termed American. It is about to neighbor a holding facility for boys and girls, detained and corralled by our United States Government.

June 16, 2018

VISCONTI’S FOUR-HOUR “LUDWIG” — A Momentous Wagnerian Film

Today’s “Wall Street Journal” includes my mini-review of a remarkable film. It’s appended, along with a chunk of my book-in-progress about Wagner the man.

The Film Society of Lincoln Center’s current Luchino Visconti retrospective climaxes with more than a week of screenings (June 16 and 22-28) featuring the restored, four-hour version of Ludwig (1973)—a rare opportunity to properly encounter a magnificent Wagnerian film.

The story is familiar as a cartoon. Insane King Ludwig II of Bavaria built expensive fairy-tale castles no one wanted. And he squandered a fortune supporting Richard Wagner, who opportunistically played him for the fool he was. He grew fat and ugly, crazier and crazier, and finally drowned himself in a lake.

I saw Ludwig when it was first released in the U.S. Helmut Berger’s Ludwig II seemed over the top. Trevor Howard, in a brief cameo, at least looked like Wagner. As with any Visconti film, the mise-en-scène was memorably luxurious—it was the film’s most notable attribute.

In fact, Visconti made a 264-minute film that was trimmed for distribution. What I saw was 137 minutes—barely half the movie. In 1980 (four years after Visconti’s death), the original negative was purchased at an auction, then restored under the supervision of the original script supervisor. This version had its premiere later the same year at the Venice Film Festival. Whether the resulting mega-film is precisely what Visconti had in mind, I have no idea. But I am certain that it is a memorable achievement.

Not only is the story that it tells no cartoon, it reasonably conforms to my own impressions of the dramatis personae, acquired over the course of a lifetime obsession with Wagner. Ludwig is an idealist, an aesthete, unsuited to reign. He is made to suppress his homosexuality. His appreciation of Wagner’s greatness is ridiculed and misunderstood. He detests the pomp of the court and resists military entanglements others regard as noble and patriotic.

Ludwig was 18 when in 1864 he ascended the throne. His instantaneous agenda was to rescue the financially strapped Wagner, and to collaborate with him in a project redeeming German culture. These aspirations were no more deranged than was Ludwig himself. As his letters confirm, he was eccentric, but certainly no simpleton. He made bequeathing a permanent Wagnerian legacy his top priority. This fairy-tale reversal stunned the ever-beleaguered composer. Ultimately, Ludwig and Wagner served one another royally. Every other factor bearing on their complex friendship of two decades shrinks to insignificance.

In Visconti’s portrayal the question of whether Ludwig was mad—debated in his lifetime and ever after—becomes moot. Chapter by relentless chapter, Ludwig ever so gradually descends into a condition of dissolute nihilism as a necessary consequence of passions and convictions he will not and cannot subdue.

The triumph of this reading is that it’s not predicated on unwanted royal duties; Visconti is reflecting on contradictions inherent in the human condition: Wagner’s incessant theme. He has discovered in Ludwig a true embodiment of the Wagnerian pariah. He has transformed Ludwig’s story into a veritable Wagner homage. The charged psychological/existential topic, the glacial pacing (the opening coronation sequence lasts fully 15 minutes), the luxuriance and amplitude—all this is what makes Ludwig a Wagnerian film, the most remarkable of its species I have ever encountered.

Ludwig becomes a solitary figure of numbing pathos. Concomitantly, Trevor Howard’s Wagner, in this full-length cut, is not the usual cartoon cad. There is nothing monstrous about him. Things Wagner said and did are (for once) plausibly enacted. He cavorts on the floor with his big dog. He honestly adores and admires the king—and also shrewdly critiques him behind his back. He paternally grasps the young man’s predicament. And he knows when he must dissimulate.

Even Ludwig’s enemies—the courtiers for whom Wagner’s genius was a pernicious myth; the doctors and diplomats who conspired to declare Ludwig mad—are quite believably depicted. They are mere mortals, confronting factors they cannot glean.

Too much critical commentary about Ludwig fastens on the scenery. But it is magnificent. Visconti so poetically renders one of Ludwig’s iconic nighttime sleigh rides—the white horses, the pristine snow, the lanterns and footmen in livery—that it nearly stops the show. The film’s visual peak is (of course) the Venus grotto at Schloss Linderhof. It is a measure of Visconti’s empathy that Ludwig’s entrance in his swan boat, and his feeding of the royal swans, heartbreakingly transcends any hint of camp. (You’ll find a pertinent clip here.)

Both these vignettes are accompanied by “The Song to the Evening Star” (sans voice) from Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Visconti’s musical masterstroke is to interpolate Wagner’s then little-known A-Flat Major Elegy for piano as a theme song; it strikes a searing intimate note.

I almost forgot. There’s a star-turn—Romy Schneider as Ludwig’s cousin, Elisabeth of Austria. Visconti treats her rejection of Ludwig’s early affections as a key to his travails. Near the end, she attempts to see him and is maniacally rebuffed. This nonencounter, played to strains of Tristan, is nearly a gloss on the opera’s ending, but with a different outcome. It works.

And here — as a P. S. — is a pertinent chunk from my book-in-progress “Understanding Wagner”:

Wagner’s written salutations to Ludwig characteristically read “my most beautiful, supreme, and only consolation,” “most merciful font of grace,” “my adored and angelic friend.” The notoriously florid effusions of these letters were both sincere and consciously hyperbolic. Looking back, Wagner would say to Bulow: “Oh, those don’t sound very good, but it wasn’t I who set the tone” [July 10, 1878]. For his part, Ludwig (whose own letters indeed “set the tone”) supported Wagner faithfully, but not without discrimination or reservation. Meanwhile Bulow was installed as conductor in Munich, and there led the premieres of Tristan und Isolde (1865) and Die Meistersinger (1868). . . .

In the midst of [the never-ending subterfuge concealing the Wagner/Cosima/von Bulow menage], Wagner whispers to Bulow: “Though we berate the ‘fool,’ he nonetheless belongs to us, and will never be able to break free of us. All we need now is a little patience. If we can obtain from him all that he has promised me – intelligible to my innermost self –, just think what an unprecedented and unhoped-for miracle that will be!” (April 8, 1866). Wagner had earlier written to Bulow: “There is something god-like about him . . . He is my genius incarnate whom I see beside me and whom I can love” (June 1, 1864). And this was by no means Wagner’s only such expression of a platonic love liaison with the king.

The relationship was further complicated by promises unkept or kept incompletely. Wagner underestimated his financial needs. He changed his mind about assigning his operas to a new Munich festival theater. But it must be said that the 562,914 marks Wagner received from Ludwig over a period of nineteen years was substantially less than what Meyerbeer received for 100 performances of Le Prophete in Berlin. As for choosing Bayreuth over Ludwig’s Munich – Wagner was surely correct to situate his Festspielhaus offsite. . . .

Ludwig got his way with Das Rheingold and Die Walkure both, premiered in Munich in 1869 and 1870. In 1876 he travelled to Bayreuth, twice, to twice attend the complete Ring of the Nibelung. In the aftermath of this first Bayreuth Festival, Wagner’s efforts to cope with the deficit in concert with Ludwig are exhausting merely to read about. He was simultaneously composing Parsifal, premiered at Bayreuth in 1882 under Ludwig’s court conductor Hermann Levi. Ludwig could not countenance attending a public performance of the sacred play; in 1884, a year after Wagner’s death, the Bayreuth production was mounted for the king, and the king alone, in Munich.

These early installments of the Bayreuth Festival, so instantly historic, vindicating Wagner’s genius to the world, were also a vindication of Ludwig, without whose patronage they could never have occurred. Ultimately, the king and his composer served one another royally. Every other factor bearing on their friendship of two decades shrinks to insignificance.

June 1, 2018

Shostakovich and the Cold War

Design Credit: Mimi McNamara

“It is difficult to detect any significant difference between one piece and another. Nor is there any relief from the dominant tone of ‘uplift.’ The musical products of different parts of the Socialist Fatherland all sound as though they had been turned out by Ford or General Motors.”

This October 1953 assessment of contemporary Soviet music, by Nicolas Nabokov in the premiere issue of Encounter Magazine, is fascinating for three reasons. The first is that Encounter, which became a prestigious organ of the American left, was covertly founded and funded by the CIA via the Congress for Cultural Freedom, itself a CIA front. The second is that Nabokov, a minor composer closely associated with Stravinsky, was the CCF music specialist. The third is that his article “No Cantatas for Stalin?” imparts blatant misinformation. And yet Nabokov was shrewd. charming, worldly, never obtuse. He was also laden by baggage of a kind that was bound to skew his every musical observation.

Nabokov’s verdict came weeks before Evgeny Mravinsky premiered Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10 with his peerless Leningrad Philharmonic. Some two years before that, Shostakovich completed a cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues for solo piano. Neither work sustains a dominant tone of uplift. In fact, both are imperishable monuments to the complexity of the human spirit, arguably unsurpassed by any subsequent twentieth-century symphonic or keyboard composition.

A cousin of the famous novelist, Nabokov was born in 1903 near Minsk to a family of landed gentry subsequently dispossessed by the Revolution. He wound up a US citizen in 1936. In 1949, he conspicuously humiliated Shostakovich at the “Peace Conference” at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel – an adventure in Soviet cultural propaganda that provoked counter-measures; the CCF came one year later.

A decade after that, JFK joined the cultural counter-offensive with a series of speeches claiming that art could only flourish in “free societies” and casting aspersion on all political art. Here is some of what he had to say:

“We must never forget that art is not a form of propaganda; it is a form of truth. In free society art is not a weapon and it does not belong to the spheres of polemic and ideology. Artists are not [as Lenin put it] ‘engineers of the soul.’ It may be different elsewhere. But democratic society — in it, the highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may. . . .”

“We know that a totalitarian society can promote the arts in its own way — that it can arrange for splendid productions of opera and ballet, as it can arrange for the restoration of ancient and historic buildings. But art means more than the resuscitation of the past: it means the free and unconfined search for new ways of expressing the experience of the present and the vision of the future. When the creative impulse cannot flourish freely, when it cannot freely select its methods and objects, when it is deprived of spontaneity, then society severs the root of art.”

It all came to an end when in 1966 Ramparts Magazine outed the CCF as a CIA operation. A firestorm of controversy and consternation erupted. Scores of prominent publications and writers suddenly discovered that they had in effect been secretly employed as American intelligence agents. The best-known book about the CCF – Frances Stonor Saunders’ The Cultural Cold War (1999) – impugns the CIA for compromising the intellectual freedoms it sought to promote. But the ironies of the campaign against Shostakovich elude her and other writers on the CCF.

The penultimate event of the PostClassical Ensemble season at the Washington National Cathedral last week – “Secret Music Skirmishes of the Cold War: The Shostakovich Case” — attempted to make some sense of it all. We assembled a former US Ambassador to Russia, a former CIA staff historian, and Vladimir Feltsman, who as the most famous Soviet “refusenik” was beginning in 1979 notoriously banned from performing in public until escaping to the West in 1987. A formidable American pianist – Benjamin Pasternack — performed four Shostakovich Preludes and Fugues, as well as his still too little-known Second Piano Sonata of 1943. We also had an actor, Ashley Smith, delivering extracts from three of Kennedy’s culture-war speeches.

The Kennedy orations made a great impression. Their sheer eloquence nearly masked their indefensible content.

But Shostakovich’s Olympian D minor Prelude and Fugue — in which the legacy of the Well-Tempered Klavier is fused with the Slavic pathos and grandeur of Mussorgsky (a more “original” creative feat, I would say, then turning Schoenberg’s 12-tone method into a comprehensive compositional prescription)– silenced all debate. Pasternack’s riveting performance was amplified by the ambience of the Cathedral’s great nave. It sounded like this (use headphones and turn up the volume).

How could Kennedy, his speech-writers and diplomatic aides, have so dismissed the caliber of such titanic music? The answer becomes obvious once the Cold War climate is recalled. A much-quoted review of Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony by Virgil Thomson in the New York Herald-Tribune (October 18, 1942) ended:

“That he has so deliberately diluted his matter, adapted it, by both excessive simplification and excessive repetition, to the comprehension of a child of eight, indicates that he is willing to write down to a real or fictitious psychology of mass consumption in a way that may eventually disqualify him for consideration as a serious composer.”

Three years later in the same publication, another composer/critic, Paul Bowles, assessed the American premiere of one of Shostakovich’s peak achievements: the Second Piano Trio. It was, Bowles wrote, “by no means one of this most compelling works. Some of its melodic material gives the impression of having been made up of unused odds and ends left over from more inspired pieces.”

As these and countless other samplings of the American musical press from the forties and fifties testify, Shostakovich (notwithstanding a flurry of high acclaim, pace Thomson, for the timely Leningrad Symphony) was viewed as a Soviet stooge – a composer whose great promise had been snuffed out by repressive ideologues. As important, the West had a musical orthodoxy of its own at least as potently repressive as anything the Soviets imposed: serial music, commanded by the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez. In fact, the criterion of worth adduced by Nabokov in his diatribe was not emotional veracity or elegance of form, but “novel tendencies” of which Soviet composers had at best displayed “faint indications.”

It took some courage to speak up for Shostakovich. One who did was Leonard Bernstein, in a 1966 Young People’s Concert titled “A Birthday Tribute to Shostakovich.” Bernstein had performed Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony in the USSR. He had met the composer. Addressing a national audience on American TV, he said:

“In these days of musical experimentation, with new fads chasing each other in and out of the concert halls, a composer like Shostakovich can be easily put down. After all he’s basically a traditional Russian composer, a true son of Tchaikovsky—and no matter how modern he ever gets, he never loses that tradition. So the music is always in some way old-fashioned—or at least what critics and musical intellectuals like to call old-fashioned. But they’re forgetting the most important thing—he’s a genius: a real authentic genius, and there aren’t too many of those around any more.”

At our National Cathedral event, both Nicolas Dujmovic, formerly of the CIA, and John Beyrle, a distinguished former US Ambassador to Russia and Bulgaria, defended the Congress for Cultural Freedom as an appropriate response to Russian disinformation. In fact, as even the Saunders book makes clear, the CCF was a sophisticated operation carried out by intellectuals on the left. One of the most fascinating episodes in her account is the CIA response to Joseph McCarthy’s loutish red-baiting, which the agency feared would undermine its nuanced propaganda efforts. And if Nabokov’s attacks on Shostakovich weren’t nuanced, if Kennedy’s speeches weren’t credible, the charged musical climate of opinion was such that nobody noticed.

Vladimir Feltsman, speaking at the Cathedral, stressed the compatibility of great art and hard times. He also praised Soviet musical training at the Moscow Conservatory as the best in the world (a verdict Pasternack challenged, having studied with Rudolf Serkin and Mieczyslaw Horszowski at the Curtis Institute). In a follow-up email, Feltsman added: “No great art is ever produced by happy and healthy folks content with their lives, no matter where.” He also wrote: “The main difference between musical education in the USSR and the US was a lack of special training for musically gifted kids in the US. For the Soviets, starting in the 1930s with Stalin, the culture as a whole was a propaganda tool foremost and they wanted to prove to the world that their musicians, dancers, and athletes were the best in the world. That was the real reason for creating these special schools that were breeding future ambassadors for Soviet empire and proved the superiority of the most ‘just and humane’ system of governance the world had ever seen.”

I would add one more irony to this complicated picture: the iron curtain. It paradoxically preserved musical traditions shattered or diffused in the West. Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues are an explicit homage to Bach. His symphonies build directly on the examples of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Mahler. A fascinating new window on the contradictions of Soviet musical life is Marina Frolova Walker’s Stalin’s Music Prize (2016), which excavates previously inaccessible Soviet archives documenting how recipients of state musical honors were chosen. Ideologues promoting Socialist Realism did not always prevail over Shostakovich and other musicians of consequence for whom the ideals of a morally charged people’s art embedded in tradition were not merely cant.

Here’s an addendum from my ongoing email exchange with Vladimir Feltsman: “What is particularly sad in the Shostakovich case (Feltsman writes) is that the mischaracterizations of his music and personality in the US were intentional and planned. Music critics are known to miss their targets time and again, but their mistakes were their own, not commissioned and paid for.”

The de facto State Department expert on Soviet music, Nicolas Nabokov was in retrospect a music analyst deafened by the opinions, assumptions, and loyalties of a dispossessed expatriate who deemed Stravinsky’s neo-classicism a supreme affirmation of artistic and aesthetic “freedom.” His writings on this topic fed the risible claims of Kennedy’s Cold War cultural orations.

What lessons, if any, can be extrapolated from this Shostakovich Case? Mainly, perhaps, that ideology and distance can greatly cripple our perceptions and assumptions. Is this finding, incriminating Cold War cultural propagandists on both sides, pertinent to the prosecution of the Cold War generally? To Cold War diplomacy as practiced under eight American Presidents? To our present-day understandings of Vladimir Putin’s Russia?

It’s something to think about.

May 1, 2018

“The Great Composer You’ve Never Heard Of” — and how he was suppressed by Carlos Chavez

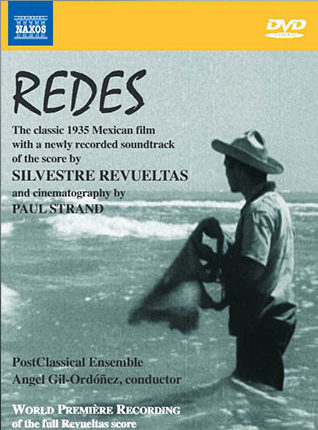

“The Great Composer You’ve Never Heard Of” – the most recent “PostClassical” broadcast via the WWFM Classical Network – spends two hours exploring the astounding achievements of Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940). The show also reveals how Revueltas’s colleague Carlos Chavez – a lesser composer, but with more institutional clout – suppressed Revueltas’s music. It’s all here.

“The Great Composer You’ve Never Heard Of” – the most recent “PostClassical” broadcast via the WWFM Classical Network – spends two hours exploring the astounding achievements of Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940). The show also reveals how Revueltas’s colleague Carlos Chavez – a lesser composer, but with more institutional clout – suppressed Revueltas’s music. It’s all here.

As readers of this blog know, Revueltas is the composer most championed by my PostClassical Ensemble in DC. He’s also the main topic of “Copland and Mexico,” the NEH-funded “Music Unwound” program I produce around the US.

In many respects, Revueltas bears comparison with George Gershwin: a self-invented composer of genius who mines the vernacular without apology or discomfort. And just as Gershwin was the victim of a “Gershwin threat” that pigeon-holed him as a dilettante interloper, so it was with Revueltas. Gershwin’s influential detractors included Aaron Copland. Revueltas was dismissed as a gifted amateur by his one-time colleague Chavez.

Copland’s view of Revueltas was comparable: he expressed wary admiration for Revueltas’s native gift: “Unfortunately, he was never able to break away from a certain dilettantism that makes even his best compositions suffer from sketchy workmanship.” Chavez chose to patronize Revueltas as a fallen disciple. If Copland mainly neglected Gershwin, he increasingly appreciated ingredients of incipient greatness. Chavez, by comparison, actively excluded Revueltas from the many Mexican programs he influentially curated in Mexico and the United States.

The writer/editor Herbert Weinstock, a Chavez friend and supporter, felt impelled to write to him on November 25, 1940, to beg an explanation: “Time and again, [I find] myself in the position of having to defend you against the charge of being jealous of Revueltas, of deliberately trying to smother his reputation by ignoring him.” Revueltas, who had just died, seemed to Weinstock “a musician of something approaching genius.” Citing Goddard Lieberson, for decades a key American advocate of twentieth-century composers, Weinstock reported that “many musical people here” struggled with the perception that Chavez “spitefully failed to do justice to his most important compatriot.”

Thirty-one years later, on October 8, 1971, Chavez delivered a lecture on Revueltas at a Mexico City conference on “La Musica en Mexico.” He complained that the “construction” of Revueltas’s compositions, “instead of showing development, was repetitive.” He continued:

“Although he showed great talent in the beginning, abrupt and impressive, his creative capacities never managed to mature, his metier was not perfected, and his style did not evolve. All his compositions are essentially similar in procedure, in expression and in style. Once or twice, after he started composing, I warned him, in conversation, about the issue of renewing oneself — renew yourself or die — and he understood this in theory. But it was easier for him to repeat his early works, the unending ostinati, the explosive contrasts, the piangendo melodies, etc, etc.”

The Revueltas scholar Roberto Kolb (to whom I am indebted for the Weinstock letter and Chavez lecture) comments: “I find a number of prejudices here. The first is the implicit definition of a ‘mature’ composition, one that incorporates evolutionary ideals such as development and organicity. This is something that Revueltas rejected, because he openly declared his intention to seek a different concept of time and agency — one inspired, for instance, by vernacular sources such as street cries. . . . Revueltas tends to base his compositions on the principle of montage and collage, dialectic or symbolic. This is linked to semantic goals, politically motivated. I find it extraordinary that this did not even occur to Chávez. He only evaluates Revueltas’s music from a formal point of view.”

Revueltas’s reputation is lately on the upswing – his music will be far longer remembered than that of Chavez. Among his peak achievements is the score for the 1935 film Redes, an uneasy partnership with Paul Strand and Fred Zinnemann. The former – like Copland, like John Steinbeck and Langston Hughes – sought inspiration from Mexico’s artists on the left. The latter – later the Hollywood director of High Noon — was in flight from Hitler’s Europe. The “nets” of the title ensnare both fish and poor fishermen. The resulting film is as epic and iconic, flawed and unfinished as the Mexican Revolution itself.

Aaron Copland wrote of Redes: “Revueltas is the type of inspired composer in the sense that Schubert was the inspired composer. That is to say, his music is a spontaneous outpouring, a strong expression of his inner emotions. There is nothing premeditated . . . about him. . . . His music is above all vibrant and colorful. . . . the score that Revueltas has written for [Redes] has very many of the qualities characteristic of Revueltas’s art.” When these words wound up in the New York Times, Copand felt the need to explain to Chavez: “I suppose you must have wondered how I happened to write that piece for the N. Y. Times on Silvestre. As a matter of fact I had no idea the Times would use it . . . I did it rather hastily . . . “

Redes — with Revueltas’s galvanizing score performed live — is one of three PostClassical Ensemble Naxos DVDs featuring classic 1930s films with “restored” soundtracks. On “PostClassical,” we audition Redes with commentary. We also sample a wide variety of other astonishing Revueltas scores, as recorded in terrific live performance by Angel Gil-Ordonez and PostClassical Ensemble. You can judge for yourself whether “all his compositions are essentially similar in procedure, in expression and in style.” And as usual I have occasion to mercilessly harangue Bill McGlaughlin with my opinions and enthusiasms. Here’s an overview of the broadcast:

PART ONE:

Music from the film Redes (1935), beginning at 19:20

PART TWO:

3:50: Son

10:10: Baile

17:11: Duelo

28:40: Sensemaya (in the original chamber version)

34:56: Carlos Chavez suppresses Revueltas

38:30: Two political songs, setting Langston Hughes and Nicolas Guillen

49:34: Planos

59:00: Revueltas as an “unfinished” composer, in parallel with Ives and Gershwin

By the way, Noche de los mayas — the “Revueltas” score championed by Gustavo Dudamel and so many others — wasn’t composed by Revueltas. It’s a kitsch confection created by Jose Limantour after Revueltas’s death, cannibalizing Revueltas’s score for a film of no distinction. Stick with Redes.

April 28, 2018

Leonard Bernstein at 100: An American Archetype

My 5,000-word piece on the Leonard Bernstein Centenary, in The Weekly Standard this week, begins with a story you’ve never heard before:

“In 1980, at the age of 62, Leonard Bernstein undertook the composition of a formidable full-scale opera, commissioned jointly by La Scala, the Kennedy Center, and Houston Grand Opera. He called it A Quiet Place. It’s the story of an unquiet family, the same one that Bernstein had depicted in Trouble in Tahiti in 1952, when he was just 34. Trouble in Tahiti is a romp, deftly dispatched. But Bernstein had not composed an opera since, and A Quiet Place did not come easily—so much so that he decided to incorporate Trouble in Tahiti as a flashback. As he worked on the score, he confided to an associate that Trouble in Tahiti was ‘a better piece.’ And so it is. The Bernstein trajectory of promises fulfilled and not is anything but simple.

“This August will mark Leonard Bernstein’s 100th birthday. The centenary celebrations started last August and are worldwide. The Bernstein estate counts more than 2,000 events on six continents. And there is plenty to celebrate. But if Bernstein remains a figure of limitless fascination, it is also because his story is archetypal. He embodied a tangled nexus of American challenges, aspirations, and contradictions. And if he in some ways unraveled, so did the America he once courted and extolled.

“Like the United States, Bernstein came late to classical music. . . .

To read the whole piece, click here.

April 18, 2018

THE FUTURE OF ORCHESTRAS — Part Five: Kurt Weill, El Paso, and the National Mood

“Wherever I found decency and humanity in the world, it reminded me of America.”

Kurt Weill wrote those words after returning from a visit to Germany in 1947. I read them aloud at least a dozen times during the Kurt Weill festival in El Paso last week. Every time I invited my listeners to consider whether or not they still apply.

Because Weill was an exemplary immigrant, he furnishes a singularly timely topic for the NEH-funded Music Unwound consortium I am fortunate to direct. “Kurt Weill’s America” has so far been produced at DePauw University and the Brevard Festival. It will travel to Chapel Hill and to Buffalo. But El Paso – a Mexican-American city on the Mexican border – is where we always knew it would most hit home.

Thanks to Music Unwound, El Paso hosts the closest collaboration between an orchestra, a university, and a community anywhere in the US. The orchestra is the El Paso Symphony and the university is the purest embodiment of the American Dream I know: the University of Texas/El Paso, known as UTEP. The vast majority of the students are local. Most are the first in their families to go to college. All high school graduates who apply are admitted. UTEP anchors El Paso.

The festival lasted seven days and included five concerts, three master classes, seven classroom presentations, and a visit to a semi-rural high school. Lots of questions are being asked these days about the relevance of orchestras to American communities. Those questions have been silenced in El Paso.

The first undergraduate UTEP class I visited was Selfa Chew’s “Afro-Mexican History.” She is herself Mexican/Chinese/Japanese, an authority on the fate of Japanese Mexicans during World War II. I told Weill’s story: a Jewish cantor’s son, born in 1900, he was the foremost German operatic composer of his generation. He fled Hitler and wound up in New York, where he re-invented himself as a leading Broadway composer before dying young in 1950. Weill considered himself an American from day one. He did not wish to consort with other German immigrants. He told Time Magazine: “Americans seem to be ashamed to appreciate things here. I’m not.”

The immediacy with which Professor Chew’s students engaged with this story was electrifying. One student asked with a trembling voice: how was Weill able to do it? She missed Mexico. Another wanted to know if Weill in America ever composed music that alluded to his German past. Not that I know of, I said. The students had me thinking about Weill in new ways.

On Friday afternoon a UTEP Music “convocation” featured the El Paso Symphony’s exceptional guest soloists – William Sharp and Lisa Vroman – singing Weill. Bill sang “The Dirge for Two Veterans,” a patriotic setting of Walt Whitman in response to Pearl Harbor. I introduced this performance by screening FDR’s “day of infamy” speech, declaring war on Japan. Brian Yothers, from UTEP’s English faculty, gave a 10-minute talk on Whitman and why Weill would have found this iconic American a kindred spirit. Two UTEP vocalists sang “How Can You Tell an American?,” composed by Weill three years into his American period. The students keenly appreciated the song’s answer: you can’t tell Americans what to do.

I would call this presentation an exemplary humanities public program in miniature. When our 80 minutes expired, no one got up to leave. I am now accustomed to this kind of response in El Paso. The students are the hungriest I know. There is no sense of entitlement to get in the way.

Bill and Lisa sang and coached at UTEP throughout the week. Brian addressed three Music classes.

The central event was an EPSO subscription concert, given twice. The first half explored Weill in Europe; the main work was the Weill/Brecht Seven Deadly Sins (1933) with Lisa as both Annas. Part two was Weill in America: the four Whitman songs sung by Bill as a potent cycle; a Broadway medley to close. This was music as sanguine as Weill/Brecht is cheeky.

What was Weill about? We posed the question with a scripted exegesis and a continuous visual track. Here’s an excerpt, including Weill’s own voice and his 1938 song “Nowhere To Go But Up.” Our host and screen also allowed us to ambitiously contextualize the Whitman songs as an immigrant’s charged response to the bombing of the American fleet, and situate the sui generis Seven Deadly Sins – a work that can easily confound – within Weimar culture: its barbed aesthetics and politics; the assaultive paintings of Otto Dix and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

After that came “I’m a Stranger Here Myself” – a joint presentation of UTEP’s Opera and Theatre programs. Cherry Duke, director of Opera UTEP, wrote in a program note: “With the prevalence of division, xenophobia and fear in today’s news, I was struck by similar themes in many of Weill’s works. He seems to ask the question: Who exactly is the stranger, the outsider, the exile?” Weill’s songs, and a chunk of his 1946 Broadway opera Street Scene, were interspersed with excerpts from Brecht’s Mother Courage, and from the 1929 Elmer Rice play upon which Street Scene the opera was based. These juxtapositions registered powerfully. Even more powerful was a recitation of “Let America be America Again” (1935) by Langston Hughes, who collaborated with Weill on Street Scene. It reads in part:

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be. . . .

(America never was America to me.)

. . .

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek—

And finding only the same old stupid plan

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak.

The show began hypnotically, with a student clarinetist, Aaron Gomez, performing his own solo version of “Speak Low,” a rendition that eloquently discovered Jewish/Yiddish roots.

The entire week was saturated by a density of discourse and inquiry about the American experience that relentlessly targeted the present moment.

I will never forget the testimony of a Jewish El Paso resident who remembered her childhood in Sioux Falls, where her father sold automobiles and supported the local NAACP. Her family had to house Harry Belafonte because no hotel would take him. Black workers were resented as outsiders. Anti-semitism was virulent. Her father’s favorite recordings included Weill’s anti-apartheid Lost in the Stars. He himself used to sing “September Song.” Only now, she told us, did she understand why.

I had my own “September Song” epiphany during my week in El Paso. It was and is one of Kurt Weill’s two most popular Broadway songs, the other being “Speak Low.” We heard Bill Sharp sing it – unforgettably – with the El Paso Symphony. The Hudson Shad – a one-of-a-kind male vocal quartet long associated with Weill – offered a doo-wop a cappella version of “Speak Low.” When a student named Jose, in Selfa Chew’s class, brought home to me the riddle that Weill in his American music never looked back, I recalled a conversation I once had with Lotte Lenya when I had the opportunity to interview her for the New York Times. She speculated that for Weill “never look back” was not only a strategy of renewal, but a way of suppressing intrusive memories, both good and bad. It cannot be a coincidence that both “September Song” and “Speak Low” course with a commanding nostalgia.

But it’s a long, long while from May to December

And the days grow short when you reach September

Weill was still a young man when he set those lyrics. Do not those signature Weill songs sublimate personal retrospection?

The quarterback for the El Paso Weill festival was Frank Candelaria, who as Associate Provost at UTEP has the vision and persistence to make big things happen. (Next fall, he becomes Dean of the Arts at SUNY Purchase.). Frank is an El Paso native, the first member of his family to obtain what is called “higher education” — Oberlin and Yale. He left a tenured position at UT/Austin to return to El Paso five years ago. He expected the Weill festival to catch fire in El Paso, but the intimacy with which it penetrated personal lives took him by surprise. On the final day he said to me: “I learned a lot about my own city and how strongly people identify as Americans.”

Which brings me to my final vignette. Once again a visit to Eastlake High School proved a humbling experience. It serves a semi-rural “colonia.” Of the school’s 2,200 predominantly Hispanic students, 69 per cent are “economically disadvantaged.” Frank and I visited Eastlake last year for “Copland and Mexico.” I described that visit in this space.

Again some 300 students were taken out of their classes for an hour-long assembly. When I entered the auditorium I was applauded – I was remembered. I spoke about Kurt Weill and immigration, I shared my clip of FDR declaring war, I played a recording of “Dirge for Two Veterans.” A girl raised her hand to tell us that she had wept twice during the song – the parts where Whitman and Weill describe moonlight overlooking the twin graves of the two Civil War soldiers, a father and son. Then I played a Frank Sinatra recording of “September Song,” after which the students requested another one. So I played Sinatra singing “Speak Low.”

Afterward, the East Lake Chorus asked to sing for me. They chose the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

April 8, 2018

“The Art and Alchemy of Conducting” — and Mahler’s Fourth

As all Mahlerites know, the opening of the Fourth Symphony is both magical and mutable. A preamble of chiming sleigh bells and flutes dissipates to a cheerful violin ditty that coyly retards as it ascends to the tonic G. Mahler writes “etwas zuruckhaltend” (“somewhat held back”). But really anything goes.

As all Mahlerites know, the opening of the Fourth Symphony is both magical and mutable. A preamble of chiming sleigh bells and flutes dissipates to a cheerful violin ditty that coyly retards as it ascends to the tonic G. Mahler writes “etwas zuruckhaltend” (“somewhat held back”). But really anything goes.

The champion retarder is Willem Mengelberg, in a famous 1939 recording with his Concertgebouw Orchestra. It sounds like this.

Since this passage is inherently playful, conductors can get away with that and we gratefully smile. Since Mengelberg was a Mahler disciple whose performances Mahler liked, since Mahler was well-known to change his mind about such details, since Mahler’s other disciples (e.g., Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer) take a much smaller retard, there is no official version.

Mahler himself last conducted the Fourth Symphony in New York – with his New York Philharmonic in 1911. We know two pertinent details about that performance, which came a decade after the symphony was composed. The first – barely believable — is from a member of the orchestra interviewed by William Malloch in 1964. He testified that Mahler had the violins swoop up to the G with a glissando starting perhaps an octave lower. The second detail is something I just learned from John Mauceri’s recent Maestros and Their Music: The Art and Alchemy of Conducting.

Mauceri – a conductor teeming with ideas about how music should be performed – discovered that Mahler’s New York score bears a notation in the conductor’s hand that insists that the sleigh bells and flutes not retard along with the violins – a startling instruction, because if followed literally it demands that for one and half beats the sleigh bells and flutes are out of synch with the first violins (and also the clarinets, by the way).

Mauceri recounts sharing this discovery with his mentor Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein, it turned out, was aware of it already. Then why didn’t you do it? Mauceri asked. “Because I chickened out,” Bernstein said. And then Bernstein changed his mind. As Mauceri notes, it’s all documented in sound.

Here is Bernstein’s New York Philharmonic recording.

And here is Bernstein’s subsequent Vienna Philharmonic recording, in which the sleigh bells and flutes don’t slow down.

The difference is so subtle you might call it insignificant but it is not. What Mahler is suggesting, in 1911, is that he has composed a kind of musical mosaic in which the two components, rather than blending, are wholly distinct. (Mauceri likens the effect to “a musical cross-fade . . . the aural equivalance of what happens in a movie when one scene dissolves into another.”) And indeed this was a direction Mahler pursued in his later symphonic style. Personally, I now prefer the passage without the “traditional” retard in the sleigh bells and flutes. It would be interesting to hear it juxtaposed with a Mengelberg retard in the violins.

Mauceri’s book shares other such details. It remarkably succeeds, it seems to me, in combining a fluent narrative for neophytes – what does a conductor do? – with detailed examples felicitously described.

In Porgy and Bess, for instance, Mauceri observes that both “Summertime” and “A Woman is a Sometime Thing” bear the same metronome marking. And yet today we always hear the first sung slower than the second. Both, Mauceri points out, are lullabies – and Gershwin, he believes, is making a point of that. Mauceri follows suit in his own Porgy and Bess recording.

The composer whose intentions most interest me is Antonin Dvorak. I feel I know a few things others do not. There is no question in my mind, for instance, that the violin tremolos in the C-sharp minor section of the New World Symphony’s famous Largo were inspired by the chill of winter. We know from Michael Beckerman’s pathbreaking research that Dvorak was here inspired by the death of Minnehaha, in Longfellow’s famous Hiawatha poem of 1855. If you read that passage, it’s partly about the weather:

Oh the long and dreary Winter!

Ever thicker, thicker, thicker

Froze the ice on lake and river,

Ever deeper, deeper, deeper

Fell the snow o’er all the landscape,

The opening of the Scherzo of the New World Symphony was inspired by the Dance of Pau-Puk-Keewis at Hiawatha’s wedding. That, I am sure, is why Dvorak introduces a triangle – it’s inspired by the bells on his moccasins. The reason I am sure is that there is also an Indian dance in Dvorak’s American Suite – and it, too, uses a triangle.

And what difference does that make? Dvorak did not write a programmatic symphony. He did not expect us to hear the tremolos and think: “winter.” We are not intended to know that the triangle has anything to do with footwear. Rather, these are private associations that guided Dvorak toward delicious instrumental touches.

On the other hand, it seems to me that knowing that the G minor theme of the first movement of the New World Symphony is an elegiac “Indian” theme does tangibly bear on musical interpretation. As with the C-sharp minor “Indian” theme in the third movement of the American Suite, we have here a plaintive tune for unison oboes and flutes, a flatted seventh, a drone accompaniment, and a pianissimo reprise. I like the conceit that the hushed reprise (which in the case of the symphony is assigned to second violins, not firsts) evokes the fated extinction of the Native American. All of which suggests to me that this little theme deserves a slower tempo than the main Allegro molto. And everything I know about the symphony’s first conductor, Anton Seidl (the hero of my book Wagner Nights: An American History), tells me that he would have slowed down here.

Bernstein was a conductor who happened to insist that there was nothing “American” about the New World Symphony. When he recorded it with the New York Philharmonic, he would not have known about its close relationship with The Song of Hiawatha, because Beckerman hadn’t yet discovered all that. In his Philharmonic recording, he takes the G minor theme briskly – at 3:03 here. See if you think it conveys Dvorak’s empathy for the Native American.

How important are a composer’s intentions, whether implicit or explicit? My thinking is more lenient than Mauceri’s. I prefer “Summertime” at a slower tempo than “A Woman is a Sometime Thing.” We know that Gershwin told John Bubbles, the original Sportin’ Life, to pick his own tempos. Was he equally lenient with Abbie Mitchell and Edward Matthews? Based on other reports, I would say: very probably.

My favorite performance of any Porgy and Bess number is Ruby Elzy’s version of “My Man’s Gone Now” at the Gershwin Memorial Concert at the Hollywood Bowl. It combines the pathos of a Billie Holiday with the high notes of a Leontyne Price. It also is shaped by an un-notated range of tempo and nuance no singer would attempt today.

Stravinsky is the antipode who insisted that there was only one correct way to interpret his music. But Stravinsky’s own Stravinsky recordings don’t back that up. He also insisted that his music was only about itself. And yet there can be no doubt that the finale of his Symphony in Three Movements was inspired by specific newsreel images of World War II. This is a topic I have addressed at length in this space. Here is the evidence.

A lot of the music we hear – a lot more of it than we realize – was inspired by stories, characters, and pictures. The opening of Mahler’s Fourth is a likely example. The New World Symphony is an example. The Symphony in Three Movements is an example. For the most part, the evidence is unrecoverable. But the attempt can matter. Wagner, in one of his essays, said the highest goal of musical interpretation is to extrapolate such meanings (he offered as an example a story for Beethoven’s Op. 131 String Quartet).

Anyone conducting the New World Symphony needs a story for the idiosyncratic ending – why is there a dirge, and a final chord diminishing to silence? In this instance, we can plausibly infer that Dvorak is thinking of the ending of his source poem – Hiawatha departing into “the purple mists of evening.” And what about that funeral march in the slow movement of his G major Symphony? The entire movement is obviously story-based. But we have no clues at hand. So conductors have to invent a story and run with it. Many don’t bother.

I remember once asking this question of Gerhardt Zimmermann, a wonderful Dvorak interpreter who now teaches at the University of Texas, Austin. “What’s the slow movement of the Dvorak G major Symphony about?” His story tumbled right out. I no longer remember what it was, and it isn’t important. It doesn’t matter if it happens to conform with Dvorak’s story, whatever that might be. What matters is that the story works for Gerhardt.

(For much more on Dvorak’s extra-musical meanings, here is the pertinent “PostClassical” broadcast. And here is a pertinent article for the Times Literary Supplement.)

April 4, 2018

Can Orchestras Be Re-Invented?

David Skinner, in his article in the current Humanities Magazine about the NEH-funded Music Unwound consortium that I direct, describes Delta David Gier, the exemplary music director of the South Dakota Symphony, addressing a room of university students and faculty:

“He starts by asking everyone to reimagine an orchestra as a humanities institution – one that brings together symphonic music and the immersive intellectual context you get from a museum. That, he says, is what is going on here, in this room, and tomorrow on stage in the program called ‘Music Unwound: Aaron Copland and Mexico.’“

Later in the piece — “Can Orchestras Be Reinvented as Humanities Institutions? Joseph Horowitz is Asking” – Skinner writes of me:

“Horowitz complains a lot, and one of his bigger, more enveloping criticisms is what brings him to the humanities. ‘Orchestras are not interested in their own history,’ he says. ‘They are not curators of the past.’ This is the moment when Horowitz is most likely to smile his brokenhearted, I-can’t-help-it, I-have-to-tell-the-truth smile. As smiles go it is remarkably sad.

“Theater companies, he points out, have dramaturges. Museums are staffed by scholars. But orchestras, despite their reverence for great music of the past, don’t even care about their own backstories, says Horowitz.”

I also read in Skinner’s piece that in front of a room of people I bring “a very different energy” than others might, “hangdog, brainy, and a little hard to predict.” In fact, he thinks “Horowitz should make a one-man show of his thoughts on classical music and life. He’s an inspired monologist – or, as he puts it, ‘I have a big mouth’ – and it would be very interesting and not a little bit shocking to have him airing his many opinions in a stand-up format.”

Any takers?

Related news: I went to the Metroplitan Museum of Art the other day to see “Thomas’ Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings,” which is up January 30 to May 13. Cole was the teacher of the most prominent, most influential American painter ca. 1860: Frederic Church. You can’t talk about Gilded Age America without referencing Church – but it’s done all the time. The same is true of The Song of Hiawatha and Dvorak’s New World Symphony: essential reference points for understanding how Americans viewed themselves before the turn of the twentieth century.

In a splendid video presentation that introduces the Met exhibit, Cole is called “a torchbearer who created a defining aesthetic” for the New World. Thanks to Cole and Church, landscape became the defining American genre for visual art.

Including major works by Turner and Constable, the exhibit dramatizes how the European landscape masters that Cole revered inspired epic canvases of mountains and plains inhabited not by peasants and farmers, but — a transformational ingredient – by ceremonial Native Americans. This achievement, clinched by Church, parallels the achievements of Mark Twain and Charles Ives, who likewise transformed hallowed Old World genres – the novel, the symphony — into something New.

Created by Elizabeth Kornhauser, the museum’s Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, the exhibit links to nine Exhibition Tours, two concerts, and various other presentations – in addition to a major publication: Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings, which “breaks new ground by presenting British-born American painter Thomas Cole as an international figure in direct dialogue with the major landscape painters of the age.”

Personally, I would never call Cole a “great painter.” (Church is another matter; and he’s the painter who most evokes Dvorak’s majestic, elegiac renderings of the American open space.) But he is a great and necessary figure in the history of American painting.

Were an orchestra to do something similar, it might be a contextualized presentation of the symphonies of John Knowles Paine (1875, 1879) – crucial progenitors of the American-sounding Second and Third Symphonies of George Chadwick en route to Ives. Paine was the first American to compose superbly finished symphonies in the Germanic mold. I would not call him a “great composer.” But he is a great and necessary figure in the history of American classical music.

American orchestras do not even know him. (An excellent recording of Paine’s Second may be heard on Naxos – with JoAnn Falletta and the Ulster Orchestra. Avoid the Mehta/NY Phil recording.)

David Skinner’s article was originally published as “Roots Music: Joseph Horowitz Looks to Reinvent Orchestras” in the Spring 2018 issues of Humanities magazine, a publication of the National Endowment for the Humanities

April 2, 2018

Shostakovich and Film — Take Two

I spent the last two days repeatedly viewing – and (as the orchestra’s pianist) participating in – screenings of the 1929 Soviet silent film The New Babylon, with Dmitri Shostakovich’s score performed by PostClassical Ensemble led by Angel Gil-Ordóñez.

I spent the last two days repeatedly viewing – and (as the orchestra’s pianist) participating in – screenings of the 1929 Soviet silent film The New Babylon, with Dmitri Shostakovich’s score performed by PostClassical Ensemble led by Angel Gil-Ordóñez.

Every aspect of this astonishing movie has surged in my comprehension and estimation – to the point, for instance, that I have no doubt that Shostakovich’s score, however little known (there is no suite by the composer), is one of the most formidable ever composed for film.

Anton Fedyashin, who took part in an eventful hour-long post-screening conversation Friday night, began with a comment I found instantly revelatory – that The New Babylon differs from other Russian silent films, also products of the feverish experimentalism of the Soviet 1920s, for combining social context and ideology with individualized human drama. That is: this polemical celebration of the Paris Commune of 1871 is infiltrated by a gritty love story, mating a fiery Communard with a hapless, placeless soldier. This is no sentimental diversion (like, say, the gratuitous love story inflicted on James Cameron’s Titanic). Rather, its shattering hopelessness meshes brilliantly with the film’s fierce depiction of class warfare and political betrayal.

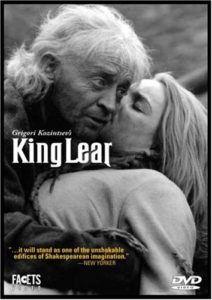

The New Babylon marks the first collaboration of Shostakovich and the master director Grigory Kozintsev – initiating a historic forty-year relationship ending with the greatest of all cinematic Shakespeare adaptations: their epic King Lear. The latter 1971 film is enriched by the same double aspect: added to Shakespeare’s human drama is a social dimension inspired, in part, by the oppressed multitudes inhabiting Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov (cf my previous blog: Shostakovich and the Fool).

As with Mussorgsky, as with the Soviet King Lear, The New Babylon miraculously intermingles the personal and with the epic. In fact, the lead actors – Yelena Kuzmina as the shopgirl and Andrei Kostrichkin as the soldier – deliver two of the most riveting cinematic performances I have ever encountered. The seething discontent and confusion of Kostrichkin’s soldier contradict the stylized “eccentricity” of the film’s general aesthetic. I should also mention, as one of the film’s many seductions, the poetic homages to Daumier and Degas – which, however, co-exist with biting lampoons whenever “bourgeois” Paris is on display. How Kozintsev and Shostakovich get away with such a plethora of stylistic and thematic ingredients I do not know.

As I learned from Anna Lawton, who guided our post-screening discussion Saturday afternoon, the Factory of the Eccentric Actor created by Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg (who co-directed The New Babylon) promulgated a manic aesthetic predilection for the circus, Charlie Chaplin, and other antidotes to pompous high culture; Eccentric antipathy to linear narrative was compatible with the signature montage effects of Soviet silent film.

The young Shostakovich feasts on cinematic montage. In 1929, he was all of 23 years old. Five years previous, he completed a First Symphony more impressive than anything by the young Mozart; it already encapsulates the irony and (incredibly enough) the pathos of his mature voice. In The New Babylon, his debut film score, he flaunts his enfant terrible energies. But as the film moves from satire to tragedy, Shostakovich’s emotional range proves limitless. And he is already a master of shaping a cinematic trajectory. Check out, for instance, the crescendo of imagery and music – of dissolute revelry — in the sequence directly preceding the percussive tramp of the invading Prussian army that lays siege to Paris and precipitates the Commune: the pertinent musical coda begins at 15:50 of this youtube link. (The frisson of this passage last weekend, in the 400-seat AFI Silver Spring Theater with a 17-member pit orchestra including a hard-driving string quintet, was electrifying; the invaluable DVD version of this film, with a larger band, is not comparably impactful.)

Montage is omnipresent in The New Babylon, typically juxtaposing decadence with travail. Shostakovich adds a third plane of expression. E.g.: here is “Preparations,” a sequence shifting between preparations for a musicale and for a bloody military encounter, at 33:00 of the film.

Such jolting contradictions in content and tone engender an active response. The film jostles feeling and thought. Notwithstanding its ideological message, it doesn’t spoon-feed the masses as would Steven Spielberg and John Williams decades later. Here are a couple of further examples:

The Commune has been toppled. The revolutionary shopgirl has been arrested. The soldier is trying to find her. Paris is now repopulated by the bourgeoisie. Shostakovich (for once) ignores this decadent spectacle and scores the Soldier: 1:18:00 of the film.

Earlier on, the bourgeoisie sing the Marseilles while French soldiers prepare to attack French citizens. Shostakovich responds with feigned relish, then decomposes their song via the intervention of an Offenbach can-can: 54:40 of the film. This compositional tour de force subverts a visceral response with a political critique. Our shifting perspective on the goings-on keeps us alert. Meanwhile, the soldier himself can’t decide which side he’s on.

The New Babylon is art, it is propaganda, it’s a political tract, it’s an aesthetic anthem. For the young Shostakovich, it was doubtless a heady learning experience. Its impact on his future development is more than ponderable.

March 25, 2018

Shostakovich and the Fool: Boris Godunov and King Lear

The most galvanizing Shakespeare experience I know is the 1971 Soviet film version of King Lear directed by Grigory Kozintsev with music by Dmitri Shostakovich. Its dimensions are such that it fails on a home screen; it demands a big theater and big sound.

The most galvanizing Shakespeare experience I know is the 1971 Soviet film version of King Lear directed by Grigory Kozintsev with music by Dmitri Shostakovich. Its dimensions are such that it fails on a home screen; it demands a big theater and big sound.

The profound Russianness of the Kozintsev/Shostakovich Lear transcends language. Re-encountering this great film in the context of PostClassical Ensemble’s ongoing two-season Russian Revolution immersion experience, I realized its Russian lineage connects to the most famous of all Russian operas: Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. It would hardly be an exaggeration to suggest that Shakespeare’s iconic seventheenth century play is here conflated with Mussorgsky’s iconic nineteenth century opera.

Obviously, both play and opera deal with a ruler who sins, and who dies consumed by crazed guilt. (Boris was complicit in the murder of the Tsarevich, and so ascended the throne.) But there is a more literal resemblance, a character common to Lear and Boris, and of special importance to Shostakovich. And that is the Fool.

The Fool can say what others cannot. In Boris Godunov, he alone can tell the Tsar to his face that he’s a murderer – and not be punished.

In Boris, the Fool comes last: one of the most original finales in opera. A conventional ending would have been the Tsar’s agonized death. He empties the throne room of all but the Tsarevich, sings “Farewell, my son, I am dying,” and expires. And that in fact is how the first version of Boris Godunov ends. But in Mussorgsky’s final version of 1872, Boris’s death, however affecting, is penultimate. Mussorgsky trumps it with a culminating vignette in the Kromy Forest. The People – a pervasive presence – acclaim a false pretender to the throne. They march with him on Moscow, emptying the stage. And – the culminating stroke – the Fool sings:

Cry, cry Russian land

Russian people

Cry

(Here is the peerless Ivan Kozlovsky, as Mussorgsky’s Fool, from a Soviet film version of the opera.)

In the Kozintsev/Shostakovich Lear, Lear’s death is witnessed by the People – an oppressed ubiquitous presence, as in Mussorgsky’s opera. The funeral cortege exits. And the Fool plays his plaintive song. It is Mussorgsky’s ending, transplanted to King Lear.

(You won’t find the Soviet Lear on youtube, but there is a video of excerpts with live accompaniment conducted by Claudio Abbado; the pertinent ending begins at 1:08.)

Mussorgsky’s sad, suffering Fool embodies a mass of sad, suffering humanity. So, too, does the Kozintsev/Shostakovich Fool. His centrality is such that his song begins the movie, accompanying the credits. Then comes a trudging horde of placeless people. Shostakovich’s scoring of this procession practically mimics Mussorgsky. The beginning of Shakespeare’s play is delayed fully five minutes.

The People even turn up in Edgar’s hut – it becomes a homeless shelter. And they elicit some of Shostakovich’s most potent and characteristic music. Their effect is to explicitly amplify and ramify the tragedy. Doubtless, Shakespeare’s dysfunctional royal family implicitly embodies a larger malaise. In the Kozintsev/Shostakovich King Lear, this malaise is explicit. We see it. It is epic, as vast as Russia itself.

Kozintsev wrote of the ending of Shakespeare’s King Lear: “Lear has no end – at least there is no finale in the play: none of the usual solemn trumpets of tragedy, or magnificent burials. The bodies, even of kings, are carried out under conditions of war; nobody even says a few elevated words. The time for words is over.”

This dire view of the human condition was also Shostakovich’s view, numbed by decades of Stalinist fear and oppression.

Reinforcing these linkages of Lear with Boris is Shostakovich’s reverence for Mussorgsky. He undertook a new orchestration of Boris Godunov. He orchestrated Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death. For Shostakovich, as for Mussorgsky, art was never for art’s sake. It possessed an ethical dimension. It commented on human affairs. Shostakovich said of Mussorgsky:

“Mussorgsky’s concept is profoundly democratic. The people are the base of everything. The people are here and the rulers are there. The rule forced on the people is immoral and fundamentally anti-people. The best intentions of individuals don’t count. That’s Mussorgky’s position and I dare hope that it is also mine.

“Meaning in music – that must sound very strange for most people. Particularly in the West. It’s here in Russia that the question is usually posed: What was the composer trying to say, after all? The questions are naïve, of course, but despite their naivete and crudity, they definitely merit being asked. Can music make man stop and think? Can it cry out and thereby draw man’s attention to various vile acts? All these questions began for me with Mussorgsky.”

The official Soviet view of Mussorgsky, as propagated under Stalin, is not irrelevant: he was an “artist of the masses,” an enemy of art for art’s sake. He projected a social conscience.

Stalin of course would never have endorsed Shostakovich’s Mussorgsky encomium, with its repudiation of the “rule forced on the people.” But as surely as Mussorgsky, as surely as Shostakovich, he rejected art for art’s sake. It was an instrument of patriotism, of propaganda, of Socialist Realist uplift.

A remarkable recent book — Stalin’s Music Prize by Marina Frolova-Walker – opens a window on Shostakovich the cultural bureaucrat. Culling Soviet archives previously shut, she documents the deliberations deciding the Stalin Prizes awarded to Soviet composers and musical performers. One discovers that Shostakovich took his role seriously. He embraced the criterion of popular appeal. His predilection that art “make man stop and think” resonates with Mussorgsky, with (an inescapable example) Tolstoy.

It bears mentioning, in this context, that Shostakovich evidently didn’t care for the United States. Also, that he said of his great expatriate contemporary Igor Stravinsky that he detected “a flaw in his personality, a loss of some important moral principles. . . . Maybe he was the most brilliant composer of the twentieth century. But he always spoke only for himself, while Mussorgsky spoke for himself and for his country.”

I am not suggesting that Shostakovich was an ideologue; there is no Socialist Realist uplift at the conclusion Kozintsev/Shostakovich King Lear. But it aligns with ideals of Russian art that endured into Soviet times. It insists upon a social context. It make us ponder people other than ourselves.

The Shostakovich quotes I cite above are from Solomon Volkov’s Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. This invaluable book is today widely reviled as fraudulent. But there is no “objective” reading of Shostakovich the man. I am certain that Testimony records a true picture of Shostakovich as experienced by Solomon Volkov. (The same could be said of my own Conversations with Arrau, which Claudio Arrau’s cousin – a Pinochet supporter — repudiated as a false portrait.) Today, no one can deny that Shostakovich’s scores are packed with encoded meanings subverting the Stalinist status quo.

In his Introduction to Testimony, Volkov calls Shostakovich “the second great yurodivy composer,” Mussorgsky having been the first. “The yurodivy is a Russian religious phenomenon, which even the cautious Soviet scholars call a national trait. . . . The yurodivy has the gift to see and hear what others know nothing about. But he tells the world about his insight in an intentionally paradoxical sway, in code. The plays the fool, which actually being a persistent exposer of evil and injustice. The yurodivy is an anarchist and individualist, who in his public role breaks the commonly held ‘moral’ laws of behavior and flouts conventions. But he sets strict limitations, rules, and taboos for himself.”

I would say that the King Lear adaptation of Grigori Kozintsev and Dmitiri Shostakovich suggests that Shostakovich identified with Shakespeare’s Fool. And that is why the Fool, not Shakespeare’s Albany, has the last word.

A final observation: during the Cold War, Shostakovich was widely perceived in the West as a composer whose early genius had been snuffed out by ideology and politics: a Soviet stooge. The notion of Shostakovich the yurodivy was as yet unglimpsed. The Congress for Cultural Freedom, funded by the CIA, extolled Stravinsky and other artists of the Free World. And JFK delivered eloquent speeches denying that art could flourish in totalitarian states. In retrospect, many delicious paradoxes complicate these decades of cultural propaganda, during which the most enduring concert music was being composed in the Soviet Union, not Europe or the US. PostClassical Ensemble ends its two-year commemoration of the Russian Revolution on May 23 at Washington National Cathedral with “Secret Music Skirmishes of the Cold War: The Shostakovich Case” – an evening including former US Ambassador to Russia John Beyrle, former CIA Staff Historian Nicholas Dujmovic, and former Soviet refusenik Vladimir Feltsman.

And next weekend we present the first Kozintsev-Shostakovich collaboration – the classic avant-garde Soviet silent film The New Babylon (1929) – with Shostakovich’s enfant terrible score performed live by PostClassical Ensemble and Angel Gil-Ordonez. That’s at the American Film Institute (Silver Spring, Md.). Information: http://postclassical.com/performances...

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers