Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 21

November 4, 2019

America’s Forbidden Composer

— I —

“Arthur Farwell is probably the most neglected composer in our history. . . . At the turn of the century no one wrote music with greater seriousness of purpose or fought harder for American music. . . . He was an intellectual and spiritual giant.”

This assessment, by the late

composer/critic A. Walter Kramer in 1973, rings ever louder today; Farwell has

been deemed untouchable. Hounded by the watchdogs

of “cultural appropriation,” he has fallen prey to dictates of political

rectitude, a victim of our escalating culture wars.

He was (among many other

things) the leader of the “Indianists” movement in American music – a huge and yet

forgotten swath of cultural history, amassing many hundreds of operas,

symphonies, chamber works, and songs until petering out in the 1930s. I first

discovered Arthur Farwell via a New World Records “Indianists” LP about twenty

years ago. The Farwell pieces on that recording weren’t very good, but they

were original. I was curious to know more about a composer who, inspired by

Dvorak, thought Americans would one day become sufficiently enlightened to

embrace Native America as an essential component of our national identity. I

soon discovered, in score, Farwell compositions far more challenging both for

performer and listener – forgotten music, once esteemed, and yet never

recorded. Ever since, I’ve seized every opportunity to present it in concert.

Not long after my Farwell

discovery, I encountered a prominent Native-American ethnomusicologist who told

me that she did not listen to Arthur Farwell’s music as a matter of principle.

This is the kind of challenge Farwell poses.

PostClassical Ensemble – the “experimental” DC chamber orchestra I co-founded in 2003 with the remarkable Spanish conductor Angel Gil-Ordonez – is dedicated to curating the musical past. As readers of this blog know, we champion composers whose time will come. Silvestre Revueltas, Bernard Herrmann, Lou Harrison are the top of our list. Whether Farwell’s time will come is another question – it will, alas, depend on political, not musical winds of change.

The 2014 PCE Naxos CD “Dvorak and America” was a start. It includes three top-drawer Farwell cameos in terrific performances: the piano pieces Pawnee Horses and Navajo War Dance No. 2 played by Benjamin Pasternack, and a 16-part a cappella version of Pawnee Horses sung (in Navajo) by the University of Texas Chamber Singers under James Morrow – one of half a dozen distinguished choral conductors who I’ve observed discovering Farwell with incredulity. You can hear the UT performance by clicking here and scrolling down.

A week ago, PCE produced a

week-long festival, “Native American Inspirations,” surveying 125 years of

music inspired by Native America. That is – we linked Dvorak, Farwell, and the

Indianists to contemporary composers, Native and non-Native, who mine Native

American songs and ceremony. In a few weeks’ time, that festival will generate

a four-hour “PostClassical” podcast. After that will come a PCE-produced

Farwell release, on Naxos, with world premiere recordings.

The DC festival, headquartered at the Washington National Cathedral, provoked divergent reviews from Anne Midgette in the Washington Post and Sudip Bose in The American Scholar. Midgette gave short shrift to Farwell; she wanted to hear more music composed by Native Americans. Her review was buttressed by a flood of supportive tweets condemning Farwell as an appropriator. Bose mounted a considered rebuttal (see below).

The festival itself included

a Saturday night public conversation, at the Center for Contemporary Political

Art, that attempted to unpack the controversy clouding Farwell and his

movement. I will return to that event below. But first: the music.

–II–

Charles Martin Loeffler called Arthur Farwell’s Pawnee Horses for solo piano (1905) “the best composition yet written by an American.” As Loeffler was for a time the most highly regarded American composer, a schooled aristocratic musical personality, a man who also grasped the importance of George Gershwin when others dismissed Gershwin as a gifted dilettante, his opinion means something. The piece itself, setting an Omaha song, is not even two minutes long. A downward cascading chant is framed by galloping figurations. The pianistic lay-out, with multiple hand-crossings, is idiomatic and ingenious. Most memorably, Farwell deploys harmony and texture to create a fragrant aura of mystery; at the close, the gallop dissipates in the treble. Considered as a musical composition, without reference to source or inspiration, Pawnee Horses is indisputably top-notch. In 1937, Farwell created a second version for a cappella chorus; the closing ascent touches a pianissimo high C. Musically considered, Pawnee Horses is a choral tour de force. Again: you can access this piece here.

Another early Farwell piano solo – Navajo War Dance No. 2 – was championed by John Kirkpatrick. He is the pianist who premiered Charles Ives’s Concord Sonata. This 1904 Farwell miniature is notably astringent, rhythmically and harmonically complex. It is also hard to play. It more resembles Bartok than any other American composition I know. But Farwell could not possibly have known pertinent Bartok keyboard music in 1904.

In the hidden world of Arthur

Farwell, the two piano pieces I have just mentioned are relatively known. But

his biggest Indianist composition, the Hako

String Quartet of 1923, is certainly not. I had occasion to present it with

student performers at the New England Conservatory in 1999. The late David MacAllester,

an eminent authority on Native American music, was at hand to react. McAllister

was greatly impressed by the Hako

Quartet.

One of the challenges of presenting Farwell in concert is enlisting Native American participants. For our DC festival, I unsuccessfully attempted to engage Native American scholars and musicians from as far away as Texas, New Mexico, and California. My greatest disappointment was the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, which declined to partner the festival even though it presented in concert the South Dakota Symphony’s Lakota Music Project, brought to DC at the invitation of PostClassical Ensemble. A staff member explained that Farwell lacked “authenticity.” But the Hako claims no authenticity. Though its inspiration is a Great Plains ritual celebrating a symbolic union of Father and Son, though it incorporates passages evoking a processional, or an owl, or a lighting storm, it does not chart a programmatic narrative. Rather, it is a 20-minute sonata-form that documents the composer’s enthralled subjective response to a gripping Native American ritual. At our festival, a sensational performance of the Hako by the Dakota String Quartet (comprising the principal strings of the South Dakota Symphony) ignited a thunderous ovation. This is a work that skillfully builds to an enraptured close, marked “with breadth and exaltation.” It is Arthur Farwell’s rapture that is here “authentic.”

Sudip Bose did not attend our Monday night concert, with the Hako. In Anne Midgette’s view, the Hako “did little with its musical ideas.” A third critic, Emily Wright for Strings Magazine, was more sympathetic but could not resist terming Farwell “perhaps naive” — meaning what? Unlike Bose’s, in The American Scholar, her summary of the Farwell story was vague and inaccurate. Her mild approbation was unconsciously patronizing.

Other Farwell compositions

are differently conceived. They more resemble transcriptions or adaptations of

Native American song. Pawnee Horses

attempts to evoke the complexity of Indian rhythms and tunes. But it would be

glib to infer that he here aspires to “authenticity.”

So what was Farwell trying to

do? He believed it was a democratic obligation of Americans of European descent

to try to understand the indigenous Americans they displaced and oppressed – to

preserve something of their civilization; to find a path toward reconciliation.

His Indianist compositions attempt to mediate between Native American ritual

and the Western concert tradition. Like Bartok in Transylvania, like Stravinsky

in rural Russia, he endeavored to fashion a concert idiom that would paradoxically

project the integrity of unvarnished vernacular dance and song. He aspired to

capture specific musical characteristics – but also something additional,

something ineffable and elemental, “religious and legendary.” He called it – a

phrase belonging to another time and place – “race spirit.”

As a young man, Farwell visited

with Indians on Lake Superior. He hunted with Indian guides. He had out-of-body

experiences. Later, in the Southwest, he collaborated with the charismatic

Charles Lummis, a pioneer ethnographer. For Lummis, Farwell transcribed hundreds

of Indian and Hispanic melodies, using either a phonograph or local Indian

singers. Even so, our present-day

criterion of “authenticity” is a later construct, unknown in Farwell’s day. If

he was subject to criticism during his lifetime, it was for being naïve and

irrelevant, not disrespectful or false. The music historian Beth Levy – a rare

contemporary student of the Indianists movement in music – pithily summarizes

that Farwell embodies a state of tension intermingling “a scientific emphasis

on anthropological fact” with “a subjective identification bordering on

rapture.”

Other writings perpetuate misleading assumptions. John Troutman’s Indian Blues (2009), a valuable treatment of “American Indians and the Politics of Music, 1879-1934,” groups Farwell with other Indianists “dedicated to the production of Indian themes palatable to non-Indian ears . . . they seemed in the end to share much more in common with the imagery found in Tin Pan Alley numbers than with the performances as originally observed and recorded by the ethnologists.” This verdict may fit Charles Wakefield Cadman, also mentioned by Troutman. But Farwell cannot credibly be dismissed in the same breath; Troutman has not done the homework. Neither does the distinguished Native-American ethnomusicologist Tara Browner, in a 1997 American Music article, undertake any concerted effort to assess the varied style and caliber of Farwell’s Indianist output. Though she prefers him to Edward MacDowell (who lacked Farwell’s passion for ethnology), Brower expresses regret that Farwell failed to “seek permission” to “incorporate” Native American music in his own. But in 1905, when Pawnee Horses was conceived, no composer, writer, or painter adapting Native American music and ritual would have thought to do that. The only present-day Native-American Farwell authority of whom I am aware is the pianist Lisa Cheryl Thomas, who admires and performs him.

Here is Sudip Bose, in his American Scholar review:

“To be sure, we can look back at Farwell’s interactions with Native American cultures, and find him lacking in certain areas. . . . Beth Levy writes that the composer’s attitudes toward Native Americans ‘never completely slough[ed] off their skin of exoticism.’ . . . Yet it cannot be denied that Farwell’s reverence for Native American music was genuine. . . . It’s a tricky thing—trying to come to terms with Farwell in our time. His perceived flaws provide detractors with enough justification to reject him out of hand. To them, it doesn’t matter what his music sounds like, or what part it played in the evolution of classical music in the United States. To them, Farwell is simply a white man who made a living at the expense of marginalized peoples. This, I believe, not only misrepresents the composer and his intentions, but it also uses the politics of our current moment to form loose judgments about a very distant time. . . . I would also like to assert that Farwell, despite his keenest ethnographic instincts, was not an ethnographer. His principal aim was not to document Native music, and certainly not to compose it. Rather, he was writing classical music—an anti-modernist classical music, rooted in diatonic harmony and sonata form, that he felt best represented America.”

–III–

Classical music lives in the

concert hall and the opera house. But classical composers – many of them –

crave the primal. It impels them to compose, no questions asked. Bartok in

rural Transylvania, Falla in the gypsy caves of Granada were galvanized by

elemental songs and dances they proceeded to diligently research. Harry

Burleigh – a frequent topic of this blog – was impelled to turn the sorrow

songs once sung by his grandfather into tuxedoed concert songs. These

transformations will always be genuinely controversial. Flamenco purists find El amor brujo denatured. Zora Neale

Hurston found concert spirituals sanitized. But these are aesthetic, not moral

judgments.

At our Saturday night conclave, pondering “cultural appropriation,” an audience member suggested a bell curve, with respectful appropriation at one end and cultural theft at the other. But an aesthetic bell curve makes more sense to me. When appropriation makes us cringe, it becomes kitsch – dictionary-defined as “in poor taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality.” The most popular Indianist song was “From the Land of the Sky-Blue Waters,” composed by Charles Wakefield Cadman in 1909. I would call that a specimen of tuneful kitsch. Though Cadman adapted an actual Native American tune, the relationship to source material is merely expedient, self-evidently casual. Cadman’s song is as remote from Pawnee Horses as a balalaika orchestra playing “Dark Eyes” is remote from Stravinsky’s Les noces.

Farwell explicitly declared himself an enemy of kitsch. He did not always succeed. To my ears, his Navajo War Dance No. 1 in its piano and choral versions – pieces on that New World LP I encountered decades ago – are “in poor taste.” They sound tacky, superficially exotic. My daughter would call them “cheesy.” Removed from the context of Farwell’s better efforts, they suggest a nonchalant submission to cliche.

In

any event: Farwell is an essential component of the American musical odyssey.

As I have too many times had occasion to observe, the appropriation critique

suppresses historical inquiry. It also cancels opportunities to engage with artworks

of high consequence. Charles Ives’s Second Symphony is one of the supreme

American achievements in symphonic music. Its Civil War finale quotes “Old

Black Joe,” a blackface minstrel song by Stephen Foster, by way of expressing

sympathy for the slave. When there are students in the classroom who cannot get

past that, it is their loss.

Even

worse is the chilling effect of the war cry. If Farwell is today off limits, it

is partly because of fear – of castigation by a neighbor. I know because I have

seen it.

Opinions

will differ about the caliber of his music. But it must be heard.

Stay tuned for a December blog linking to “PostClassical” webcasts featuring the “Hako” Quartet and five more Farwell piano and vocal compositions recorded in live performance at our DC festival.

October 20, 2019

Solomon Volkov on Stalin and Shostakovich

Of Joseph Stalin the culture-czar, Solomon Volkov comments:

“People underestimate the level

of control that Stalin maintained. I once tried to count the number of people in

the arts that Stalin controlled personally – listened to their music and read

their books. It was close to one thousand. This was Stalin’s habit. So Shostakovich

knew very well he was under the constant surveillance of the most powerful

person in the country. Stalin’s involvement in the world of culture was

extraordinary. It was something unprecedented. There is evidence that he read

every day 300 to 400 pages of fiction and non-fiction.

“When describing Stalin I use two words. He was an ‘evil genius’. People writing about Stalin sometimes judge him like a dean of the faculty or something like that. They don’t understand that he was extraordinarily gifted – in terms of things like memory and energy. People like that are born maybe once in a century. To be sure, he was a totally evil person. No one in their right mind would argue with that. But, for example, he would never raise his voice, especially when talking to artists. He was always very polite. And he was often more informed than they were. The famous Stalin Prize committee would submit works for his approval. ‘Did you actually read this book?’ he would ask the committee. And they knew that before Stalin you couldn’t lie. ‘No, comrade Stalin, I did not read this book.’ And Stalin might answer: ‘And I unfortunately did.’ He considered himself a kind of father figure. A father would punish his child – and then he might reward him.”

As author of Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, Volkov speaks with special authority. (Never mind the “Shostakovich Wars” – Testimony is a record of Shostakovich as understood by Volkov. Others have a different picture. Human beings have no fixed identity.) The Volkov commentary I here quote derives from our latest “PostClassical” podcast: “Shostakovich and the Cold War.” You can audition the entire three hours of music and conversation here.

Bill McGlaughlin asked Solomon Volkov to describe his first meeting with Dmitri Shostakovich.

“I started to write about music

at a very early age. I was fifteen. I moved to Leningrad to study there, and I was

still a pupil when I went to the premiere of Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet.

I had already published several pieces in Riga and Leningrad. After listening

to the Eighth Quartet I was extremely impressed. I went to the local newspaper

and suggested that I write a review. The accepted it. And it happened that my

small piece was the first review of this very important Shostakovich piece that

appeared in print.

“Shostakovich, to his credit or not, read every review. He was never this type of genius who says ‘I am not interested.’ He never pretended to be. So sometime later I went to a Shostakovich concert in Leningrad and somebody introduced me to him. And he remembered. ‘Oh yes, I read your review.’ He said a few nice words. I of course was elated. And that was the start of our relationship.

“I wouldn’t dare to record

him. He was mortally afraid of a microphone. When he was not talking in his

official capacity he could be very eloquent. But the moment he was obliged to

say something official he was a different person.”

And Shostakovich was a different person, as well, to President John F. Kennedy, Nicolas Nabokov, and other practitioners of the cultural Cold War – the first topic of our podcast. It begins with the voice of JFK, denying that the Soviet Union could possibly produce great art. Commensurately, Shostakovich was long denigrated in the West as a Soviet stooge. Around the time Leonard Bernstein spoke up for Shostakovich in, 1966, the culture winds began to change. Testimony, published in 1979, marked a turning point; Shostakovich was never again dismissed as a purported tool of the Communist Party. I asked Volkov if Shostakovich’s “messages in a bottle” – the dissident subtexts we now discern – were acknowledged in Soviet Russia. He said: “In the West they were not

interested, and in the Soviet Union they were afraid.”

A second topic of our podcast is music and World War II – we compare Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements (1945), Prokofiev’s Seventh Piano Sonata (1942), and Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 2 (1944). I’ve previously written a lot about Stravinsky’s musical picture of World War II, a California product inspired by newsreels of goose-stepping soldiers and falling bombs. Prokofiev, too, records the tumult of battle – as does the amazing live performance by Alexander Toradze (from a PostClassical Ensemble concert of 2017) that we audition. Shostakovich’s wartime response in his Second Trio is, by comparison, markedly interior. It does not document the war; it extrapolates a message for humanity.

How did Shostakovich so

manage to transcend the personal – to “bear witness”? Angel Gil-Ordonez, on our

podcast, pertinently remarks: “Shostakovich is always on the side of those who

suffer. This is what touches us.”

LISTENING GUIDE:

PART ONE:

00:17 – JFK speaking about

the “place of the artist” in “free societies” – and denying the possibility of

distinguished Soviet art

10:15 – Nicolas Nabokov, the

source of Kennedy’s doctrine, denounces Shostakovich

11:18 – Shostakovich: Prelude

and Fugue in D minor (Benjamin Pasternack, piano)

26:15 – Leonard Bernstein

speaks up for Shostakovich (1966)

27:33 – How Solomon Volkov

met Shostakovich; the String Quartet No. 8

29:00—Volkov on Stalin as

culture-czar

39:07 – Shostakovich/Barshai:

String Symphony (PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordonez)

PART TWO:

00:00 – Waltz from The New Babylon, Shostakovich’s first

film score (PCE/Gil-Ordonez)

3:44 – Volkov on Shostakovich

and film

9:07 – The New Babylon: finale (PCE/Gil-Ordonez)

18:00 – JFK notwithstanding:

propaganda as high art — The New Babylon

20:30 – Volkov on Stalin and

film; “he read 300 to 400 pages a day”

24:00 – Musical responses to

WW II: Stravinsky vs. Prokofiev vs. Shostakovich

31:45 – Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 7: finale (Alexander Toradze, as filmed/recorded by Behrouz Jamali for PCE)

44:00 – Shostakovich “bears

witness” to his times

PART THREE

00:00 – Shostakovich Trio No. 2 (Netanel Draiblate/Benjamin Capps/Alexander Shtarkman, as filmed/recorded by Behrouz Jamali for PCE)

30:00 – Volkov on

Shostakovich and Jewish music

October 13, 2019

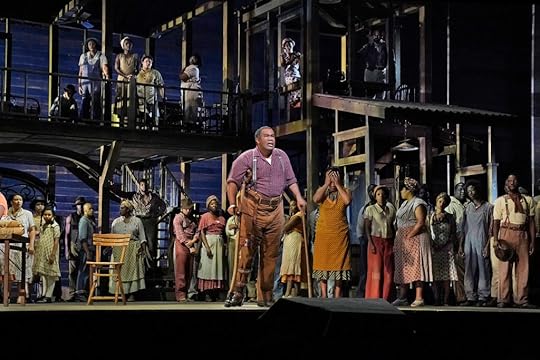

Is Porgy a “Stereotype”? — Take Three

Kevin Deas

Kevin DeasKevin Deas, the exceptional bass-baritone who is the anonymous “Porgy” of my previous blog, has written to me at greater length about singing the part – and the importance of the view “from below.” He says:

“Being on my knees for my first staged Porgy was revelatory. Not only was it the first time that I’d sung the complete role, it was that perspective that was, in particular, very profound.

“I’d sung the concert version (comfortably erect) 10s of times. I didn’t fully appreciate the character. Now when I sing extended concert versions, I try to incorporate that perspective. I often ask to sing the duet sitting. Bess standing, passionate, baffled, next to the cripple (not someone merely indisposed). That positioning alone portends the unlikely success of this pairing. When she kneels towards the end (as in the production I was in) she acquiesces and inhabits his low-lying, sweaty (probably smelly) existence. It makes the desperate nature of their circumstance more sympathetic.

“Being on his knees also makes Porgy’s plight that much more compelling for the audience. The interpretation necessarily becomes more nuanced.

“As the performance starts, the daunting prospect of being on one’s knees for nearly three hours puts one in a specific emotional space. Hearing the beauty of Gershwin’s musical adoration (as the orchestra plays the ‘Porgy motif’) as I enter on the cart gives me comfort.

“Before I discovered inline knee braces, with gel padding, I could peel a layer of skin off of my knees from the constant burn after an extended tour. The most difficult scene was kneeing my way across the stage to bring down Crown.”

Kevin – with whom I have been privileged to perform the spirituals of Harry Burleigh for a dozen years – is the most mellifluous Porgy I know. How I wish he had an opportunity to record it. You can see and hear him sing “I got plenty o’ nuttin’” and “Bess you is my woman” (with Angela Brown) in concert (in Moscow) here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GBRd_oHxFSc

It occurs to me to add that no opera of comparable stature (with the possible exception of Wagner’s Siegfried) has been so disserved in performance.

Last Spring, teaching a graduate seminar on music and race at SUNY Purchase, I spent a full month exploring Porgy and Bess with my students. Every one of them preferred DuBose Heyward’s novel to Gershwin’s opera. The reason is that they were new to the opera (except for some songs) – and there does not exist an adequate recording or film. We made do with Simon Rattle’s studio-bound Porgy and Bess and the disappointing San Francisco Opera DVD. There are recordings with various points of excellence, but none in which the casting, conducting, playing, and trims (this is an opera that must be abridged) add up. I could not convey to my students a full, true impression.

PS — Another memorable email, from the prominent American historian Allen Guelzo, in response to my American Scholar review of Porgy at the Met: “In my mind, I step back and see Gershwin against what Thomson and Copland were writing then, and suddenly it comes to life, and makes them look like over-dressed primas.”

October 11, 2019

Is Porgy a “Stereotype”? — Take Two

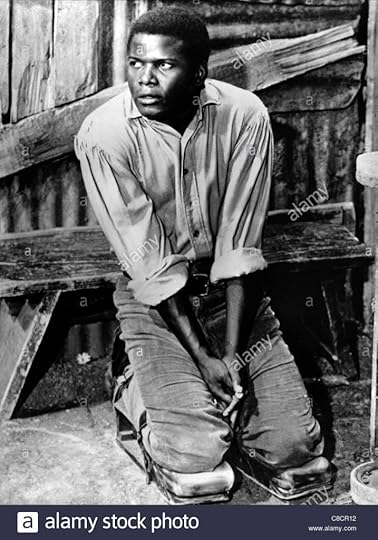

Sidney Poitier as Porgy

Sidney Poitier as PorgyOf the interesting emails I received in response to my American Scholar review of Porgy and Bess, the most informative was from a singer with considerable experience doing Porgy on stage. He wrote:

“As challenging as it was for me to

sing most of Porgy on a cart (the rest of the time I was on my knees), there is

no substitute for singing and viewing the world from that perspective.”

Gershwin intended Porgy to be pulled by a goat while sitting on a cart. He is a man who cannot stand up. Today Porgy is typically ambulatory on crutches: mobilized. I now realize this is one of the reasons that Eric Owens’s portrayal, at the Met, “starts too strong.” It is because he is erect.

Early on, Porgy sings: ““When Gawd make cripple, He mean him to be lonely. He got to trabble dat lonesome road.” This crucial self-observation only really registers when Porgy “views the world” from below. And the goat reinforces his distance from normal human company.

Also — as John Mauceri just pointed out in another email to me — if Porgy can walk on crutches, he can go to that picnic.

Additionally, re-reading my review, I wish I had been more explicit about the regrettable impact of Sidney Poitier’s performance in the 1959 Otto Preminger film version of Gershwin’s magnificent opera. Poitier is so manifestly uncomfortable in this role that his portrayal reads as a critique. However subliminally, we are made to believe that Gershwin has created an objectionable “stereotype.” So far as I can ascertain, this is a claim mainly originating in the fifties: long after the opera’s premiere and initial reception.

It was my privilege to speak with Poitier on the phone when I wrote “On My Way” – The Untold Story of Rouben Mamoulian, George Gershwin, and “Porgy and Bess.” He was perfectly candid. He never sought to play Porgy. Rather, Lillian Schary Small, a sometime associate of Poitier’s agent Martin Baum, sought and acquired it for him. Samuel Goldwyn, who initiated and produced the film, was too star-struck to realize what he was doing (his equally risible first choice had been Harry Belafonte). Ultimately, Poitier agreed only on condition that he also be cast in a film he coveted – The Defiant Ones. Of Porgy and Bess he said to me: “I don’t talk about it. I’ve dismissed it. I did it, I didn’t want to do it. I did not want to be stopped in my tracks.’

I also had occasion to discuss Preminger’s

film at length with the late Andre Previn, who as music director both conducted

and arranged Gershwin’s score. What Previn had to say (a lot) is recounted in detail

in my book. Of Poitier he commented: “Sidney told me he was ‘tone-deaf.’ I said

‘C’mon.’ So I sat down at the piano and played two notes, one at the top of the

keyboard, one at the bottom. ‘Now which note is higher?’ I asked Poitier. ‘It’s

your job to tell me,’ he answered.”

The gruesome tale of how Samuel Goldwyn hired and fired Rouben Mamoulian, then replaced him with the martinet Preminger — also in my book, ,thanks to Mamoulian’s copious documentation — itself deserves to be a movie, with secondary parts for Poitier, Previn, and Dorothy Dandridge (Preminger’s ex-girlfriend, whom he verbally abused on the set). It could more productively engage with Porgy and Bess – and its attendant issues of race and American identity — than have any number of stage productions. (I have a five-page treatment in my pocket).

October 9, 2019

Why “Porgy and Bess” and the Met Need One Another

To read my review of the Met’s new “Porgy and Bess,” just posted online by “The American Scholar,” click here. It begins:

That the

Metropolitan Opera has opened its season with a fresh production of George

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess is cause

for celebration.

The Met came late to black America when in 1955 it engaged Marian Anderson to sing Verdi—she was already 57 years old. It came late to Porgy when in 1985 it mounted an earlier production—half a century after the opera’s premiere. More than its predecessor, the Met’s vigorous new staging manages to vindicate a controversial cultural landmark and seal its stature as the highest creative achievement in American classical music. New York’s new Porgy is also cause for reflection and self-scrutiny. It must mean something that the most widely known American opera is a white composer’s version of black American life. It has no finished form. Its reputation remains unsettled. It feeds on the fraught racial sensitivities of the current moment.

When Porgy and Bess was introduced in 1935, a

prevalent response was: “What is it?” A second production, in 1941, reconceived

the opera as musical theater with dialogue. It subsequently became best known for

its songs. In the 1950s, the NAACP urged black artists to stay away from it.

More recently, a boldly revisionist version, with Audra McDonald as Bess,

aspired to add “dignity” to the main characters. At every stage in this saga,

the accompanying discourse has been charged and ill-informed.

Several

years ago, I found myself addressing

a graduate seminar on 20th-century opera. I asked the students what Porgy and Bess was about. A black

student volunteered: “It’s about black Americans.” Wrong, I said. Several

months ago, when the Met’s new production (shared with the English National

Opera and the Dutch National Opera) was given in London, a prominent local

critic called it a “period piece.” Wrong again, I say.

My review ends:

Edward Johnson [the Met’s General Manager in the thirties] found Porgy and Bess too black. James Baldwin considered it too white. Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, even Leonard Bernstein patronized Gershwin as something less than a “real composer.” Today that tide has turned. The modernist view of Gershwin the gifted dilettante is no longer heard. A burgeoning interest in the interwar fate of black classical music will surely promote new understandings of Gershwin as a necessary interloper between “classical” and “popular” genres severed by 20th-century aesthetic currents. If a whiff of opprobrium remains—if Porgy and Bess is resisted for “stereotypes” that do and do not inhabit Catfish Row—Gershwin’s opera will ever remain an inexhaustible American topic.

In retrospect, Porgy and Bess and the Metropolitan Opera have long needed one another. In 1935, Gershwin spurned Otto Kahn’s invitation to stage Porgy at the Met. In 1938 Johnson declared the Met uninterested in George Gershwin. In the seventies, Schuyler Chapin envisioned a Porgy and Bess conducted by Leonard Bernstein. In 1985, James Levine finally brought Porgy into the big house, but the production floundered. This time the marriage seems real.

RELATED LINKS:

I audition my favorite Porgy and Bess recordings: https://www.wwfm.org/post/postclassic...

My Times Literary Supplement review of the American Repertoire Theatre’s 2012 misproduction of Porgy and Bess: https://www.artsjournal.com/uq/2012/0...

September 21, 2019

Why Did American Classical Music “Stay White” — Take Two

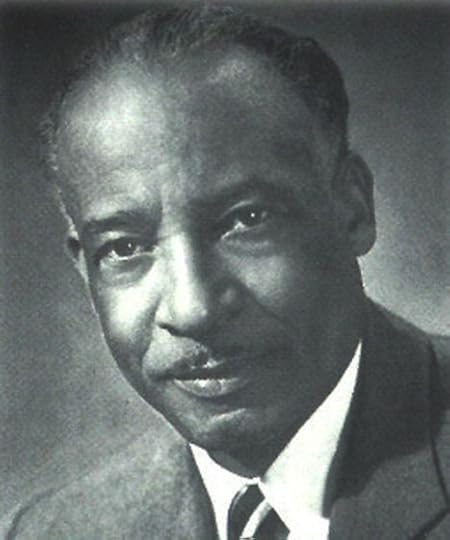

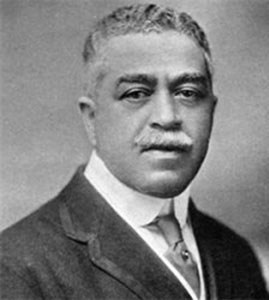

William Dawson

William DawsonPicking up on my American Scholar piece, Tom Huizenga of National Public Radio interviewed me about the fate of black classical music – and here is his interview.

Our conversation was

wide-reaching, and ultimately led to this exchange:

Huizenga: Near the

end of your essay, you write: “Might American classical music have

canonized, in parallel with jazz, an ‘American school’ privileging the black

vernacular?”

Horowitz: I don’t want to sound grandiose, but really it’s a question that all of us should be asking today — all of us who care about the fate of classical music in America. What we’re looking at right now, this extreme marginalization of classical music, is really the chickens coming home to roost. When I wrote Understanding Toscanini in 1987 and said, “This is a classical music culture built on sand, because it’s European sand,” most people beat me up for that and thought that I was out of my mind. But I was right. And we’re now suffering those consequences. We don’t have deep roots for our American classical music culture.

Here’s another exchange from the interview:

Huizenga: I love this quote from Dawson that you include in your essay. When he talks about his symphony, even before Stokowski premiered it, he says: “I’ve tried not to imitate Beethoven or Brahms, Franck or Ravel — but to be just myself, a Negro. To me the finest compliment that could be paid to my symphony when it has its premiere is that it unmistakably is not the work of a white man. I want the audience to say: ‘Only a Negro could have written that.’ ” But it seems Dvořák was suggesting that white composers should be writing symphonies that sound like Dawson’s. Are you also arguing for that?

Horowitz: Well, Morton Gould wrote a piece called Spirituals, and of course Gershwin wrote Porgy and Bess, contains some spirituals of his own. More generally, we’ve had innumerable examples of white composers drawing on the African American vernacular. The problem has been the quality of that work and its marginality. I’ll say explicitly I don’t believe you have to be black in order to write a great symphony or opera galvanized by great black vernacular music. That’s my personal opinion. I happen to think Porgy and Bess is a great opera. The guy who wrote it happened to be white. And you have this quote from Dawson that would seem to suggest otherwise. And it’s a compelling quote. It has actually been suggested that the Negro Folk Symphony is “black” not only for its sources but for its very style, which evokes improvisation. But that’s a dangerous topic to speculate about — what is “essentially” black or white. You’ve asked an uncomfortable question, right? And I’m giving you an uncomfortable answer.

And another:

Huizenga: Sometimes it takes an outsider [like Dvorak] to point out the true and valuable characteristics of a culture.

Horowitz: The Europeans tried. They actually would come

and lecture the Americans: They would say, “You don’t realize the

importance of your own African American music.” Ravel said that; Arthur

Honegger said that. And the

Americans — especially in the case of Olin Downes, the chief music critic of The New York Times —

said shut up, you’re wrong, don’t tell us what to do. If you read Olin Downes’ New York Times obituary for

George Gershwin, your skin will crawl. There is a feeling of contempt there,

that Gershwin was overrated and not the real thing.

September 12, 2019

Why Did American Classical Music “Stay White”?

William Dawson

William DawsonIn 1893 Antonin Dvorak, teaching in New York City, predicted that a “great and noble school” of American classical music would arise from America’s “Negro melodies.” Dvorak’s prophecy was instantly controversial and influential.

But the black musical motherlode migrated to popular genres known throughout the world. American classical music stayed white. The reasons are both obvious and not.

This is the topic of my book-in-progress Dvorak’s Prophecy. In the current issue of The American Scholar, I encapsulate my findings. I identify two factors: institutional racism (obvious) and modernism (not so obvious).

What’s the pertinence of Aaron Copland’s poor opinion of “Mr. Gershwin’s jazz”? Of Virgil Thomson’s view that American folk music was fundamentally white? Of Leopold Stokowski’s credible assertion that William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1934) marked “a wonderful development in American music”? And whatever happened to that formidable symphony, greeted by one eminent critic as “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved”?

Here’s a taste of my article:

“The reigning paradigm for a modernist ‘American school’ had no more use for sorrow songs than for Gershwin or Ives, not to mention the ‘black’ symphonies of Still, Price, or Dawson. The same fate would have befallen the most popular, most iconic American concert work – Rhapsody in Blue– if Paul Rosenfeld had held sway. Writing in The New Republic, the high priest of American musical modernism detected in Gershwin the Russian Jew a ‘weakness of spirit, possibly as a consequence of the circumstance that the new world attracted the less stable types.’ Rosenfeld vastly preferred the ersatz Piano Concerto that Copland produced two years after Gershwin’s ‘hash derivative’ Rhapsody. Elevated by Copland, jazz had at last ‘borne music.’

I conclude:

“Does William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony signify an ephemeral footnote or a crucial squandered opportunity? In the history of twentieth century American music, the black musical motherlode migrated to popular genres with magnificent results – in part through natural affinity; in part because it was pushed. Might American classical music have canonized, in parallel, an ‘American school’ based in the black vernacular? I believe we may be about to find out.”

Read the entire article here. To hear a related podcast (with musical examples), click here.

August 31, 2019

What Happened Between Vladimir Horowitz and George Szell?

George Szell

George Szell“As admirers of Horowitz’s musicianship and resilience, we must face these realities remembering that, in the end, he loaded his baggage onto his back and jogged across the finish line, smiling from ear to ear. Today, the weight of Horowitz’s baggage serves mainly to accentuate the magnitude of his ultimate triumph.”

Thus Bernard Horowitz on Vladimir Horowitz. These two are unrelated. Bernard, however, happens to be my son Bernie – whose obsession with Vladimir has been the topic of numerous filings in this space.

It has been many years since Bernie began plying me with

rare Horowitz recordings in an attempt to bludgeon me toward a more favorable

opinion. As I have conceded, he’s met with some success.

The most recent Sony Classics Horowitz re-issue – “The Great Comeback: Horowitz at Carnegie Hall” – comprises 15 CDs and an eleganty illustrated 200-page booklet. In a formidable review the other day in Spain’s El Pais, Pablo Rodriguez cited Bernie’s Sony essay at length. Truly, as Rodriguez writes, it more clarifies Horowitz’s epic 12-year retirement (1953-65) than anything previously written. The details are remarkable.

For one thing, there was an incident with George Szell, whom Horowitz (Bernie writes) resented for his “ingratitude and nastiness towards artists – including Toscanini and Rubinstein – who had helped him financially and professionally after he escaped Nazi Germany.” When Dmitri Mitropoulos suffered a heart attack, Szell was (inexplicably) chosen by the New York Philharmonic to partner Horowitz in Tchaikovsky’s B-flat minor Piano Concerto (which Szell loathed) for the Horowitz Silver Jubilee on January 12, 1953. The broadcast recording of that performance documents a singular feat of symphonic accompaniment: to my ears, a conductor caustically intent on driving every bit as fast as his hurtling soloist.

Afterward there was a party at Horowitz’s apartment. As

Bernie writes (quoting a private tape of Horowitz in bitter reminiscence): “Szell

and his wife . . . walked into the Horowitz’s living and room and beheld

Horowitz’s favorite painting: ‘The Acrobat in Repose’ by Pablo Picasso. Mr. and

Mrs. Szell exclaimed, ‘Aha! You see what painting they have here? You see what

painting they have here?! It’s just like the pianist!’”

This vituperative outburst coincided with self-doubts Bernie

also documents: opting for Prokofiev, Barber, Kabalevsky and other moderns,

Horowitz had shifted his attention away from Classical and Romantic repertoire;

he had opted for a more brilliant instrument; he was experiencing qualms about

“the trajectory of his career.” He retired from the stage six weeks later.

Some four years after that, Horowitz’s daughter Sonia attempted

suicide on a motor scooter in Italy. Horowitz’s apparently callous response has

never made any sense. But Bernie connects this to the tragedy of his brother,

Jacob, a hospitalized World War I veteran whom Vladimir had visited daily before

Jacob hung himself. Bernie has additionally uncovered poignant documents

showing that Horowitz, “an absentee father during Sonia’s adolescence,” bonded

with his daughter in New York shortly before she departed for Italy and her

near-fatal accident.

These revelations in Bernie’s Sony essay hint at a larger

portrait he has unearthed of a young artist unmoored by the Russian Revolution

(which decimated his family), then coping for decades with demons of every

description – and yet ultimately renewed upon returning to Russia, and to his

personal and artistic roots, at the age of 82.

August 28, 2019

Busoni, Kandinsky, Schoenberg — Instinct at the Cusp

It’s a truism that, as aesthetic movements go, the visual arts get there first. Think of Impressionism, which didn’t begin to inflect music until Debussy and Ravel – decades after Monet.

Expressionism is another matter: the synchrony is amazing. I am thinking of 1910: the year of Wassily Kandinsky’s first non-representational painting. Non-tonal music was simultaneously conceived by Arnold Schoenberg and with the same goal: capturing instinct at the cusp. What is more, Kandinsky and Schoenberg recognized their kinship. And they corresponded about it: an imperishable sequence of letters. (Schoenberg singled out Kandinsky’s “Romantic Landscape” [1911], reproduced above, as a personal favorite.)

There is also a third participant: Ferruccio Busoni, one of the most magical figures in the history of Western music. Busoni and Schoenberg also corresponded: an even more amazing written exchange. The moment I discovered it I knew it had to be animated in performance. The opportunity materialized two weeks ago in the form of a PostClassical Ensemble Concert at The Phillips Collection in DC: “The Re-Invention of Arnold Schoenberg.”

The Busoni/Schoenberg correspondence is not only acute; it

is hilarious – and at our concert William Sharp, enacting both parts, had the

audience in stitches. Schoenberg’s impassioned self-exhortations to “express

myself directly,” to renounce

acquired knowledge in favor of “that which is inborn, instinctive” can sound like a tangled Monty Python script:

“This is my vision which I am unable to force upon myself:

to wait until a piece comes out of its

own accord in the way I have

envisaged. My only intention is to have no intentions!”

Busoni is the adult in this exchange. But he is also a

serene provocateur. When Schoenberg sends him a pair of non-tonal piano pieces

(Op. 11 – composed in 1909), he is full of admiration. He then imperturbably

adds:

“My impression as a pianist,

which I cannot overlook, is otherwise. My first qualification of your music ‘as

a piano piece’ is the limited range of the textures. As I fear I might be

misunderstood, I am taking the liberty, in my own defense, of appending a small

illustration.”

Busoni here takes a measure of Schoenbeg’s piano writing,

and “enhances” it. He continues:

“But this is neither intended as judgment nor as criticism –

to neither of which I would presume, but simply a record of the impression made

and of my opinion as a pianist.”

Schoenberg:

“I have considered your reservations about my piano style at

length. It seems to me that particularly these two pieces, whose somber,

compressed colors are a constituent feature, would not stand a texture whose

effect on one’s tonal palate was all too flattering.”

Busoni:

“I have occupied myself further with your pieces, and the one in 12/8 time [No. 2] appealed to me more and more. I believe I have grasped it completely — although the form of expressing it on the piano has remained inadequate to me. To complete my confession, let me tell you that I have (with total lack of modesty) rescored your piece. Although this remains my own business, I should not fail to inform you, even at the risk of your being annoyed with me.”

Schoenberg was a connoisseur at taking offense. My favorite

Schoenberg sentence was written to the conductor Otto Klemperer. They were

colleagues in Los Angeles. Klemperer performed Schoenberg with his LA

Philharmonic – but would not broach his non-tonal works. Schoenberg wrote: “The

fact that you have become estranged from my music has not caused me to feel

insulted, though it has certainly estranged me.”

And here is Schoenberg’s response to Busoni in 1909:

“Above all, you are certainly doing me an injustice. But my

trust absolutely cannot be shaken by this divergence. On the contrary, it has

increased since I personally came in contact with you. The intuition I already

had about the nature of your personality has been confirmed. And now I have

formed a fairly clear picture. I can perceive a facet of your personality that

is infinitely valuable to me: the endeavor to be just! And I value this

endeavor higher than justice itself. Therefore, even if you are in fact doing

me an injustice, nothing in the world could give me greater pleasure than the

way in which you do so. But, as I said: I believe in actual fact that you are wrong.”

Busoni:

“Your last letter is an interesting document, which I value very highly. . . . Happily we have

struck an attitude of frankness to one another, and I would ask: to what extent

to you realize these intentions? And how much is instinctive, and how much is

deliberate?”

Busoni thereupon proposed that both versions of Op. 11, No.

2, be published in tandem.

Schoenberg:

“You must consider the following : it is impossible for me

to publish my piece together with a transcription which shows how I could have

done it better. Which thus indicates

that my piece is imperfect. And it is impossible to try to make the public

believe that my piece is good, if I

simultaneously indicate that it is not

good.”

Busoni closed the exchange:

“For various reasons, I am unable to give my formal assent

to play your pieces, but I shall always be on your side.”

At our concert, Alexander Shtarkman illustrated at the piano

how Busoni made Schoenberg’s keyboard writing more “pianistic.” And he

performed Op. 11, No. 2 (as Schoenberg composed it). We also sampled the

Schoenberg/Kandinsky exchange accompanied by paintings by both Kandinsky and . . . Schoenberg (“Perhaps you

do not know that I also paint”). But the evening’s main events were a pair of

torrential musical compositions.

In 1907 – one year before Schoenberg’s first non-tonal compositions; two years before his Op. 11; three years before Kandinsky’s canvases turned wholly abstract – Busoni published a prophetic manifesto: Sketch for a New Aesthetic of Music. Schoenberg read it with admiration. He also recommended it to Kandinsky. A key passage explicates the notion of “Ur-Musik” – a primal “absolute music” or “infinite music” privileging spontaneity and instinct:

“Is it not singular, to demand of a composer originality in

all things, and to forbid it as regards form? No wonder that, once he becomes

original, he is accused of “formlessness.’ . . . Such lust for liberation

filled Beethoven that he ascended one

short step on the way leading music back to its loftier self – He did not quite

reach absolute music; but in certain moments he divined it, as in the

introduction to the fugue of the Hammerklavier

Sonata. Indeed all composers have drawn nearest the true nature of music in

preparatory and intermediary passages, where they felt at liberty to disregard

symmetrical proportions, and unconsciously drew free breath.

The famous notes-in-a-void Hammerklavier passage — which Shtarkman performed for us at our concert – says it all. Next to Beethoven, Busoni continues, Bach comes closest to “infinite music.” He also cites examples in Brahms and Schumann. In Busoni’s own solo piano output, a prime specimen of Ur-Musik is his Sonatina seconda from 1912. This ten-minute, one-movement musical tornado, in which motivic shards ride the storm or recede into ghostly clouds, is known (if at all) by reputation rather than experience. So I asked Alexander Shtarkman to learn it and play it for us. He magnificently obliged; here it is.

After the horrors of World War I, the moment for unrestrained Expressionism was over. Busoni opted for a “New Classicism.” Schoenberg opted for an insane 12-tone theory that would organize his non-tonal onslaughts. He also fled Hitler’s Germany for – an incongruous destination – Los Angeles (he liked the weather). There his output included a twentieth century patriotic masterpiece: the Ode to Napoleon – a work I have long presented and written about. It closed our concert in a blaze of exaltation.

In William Sharp’s electrifying performance, with Angel Gil-Ordonez conducting and Alexander Shtarkman at the piano, Schoenberg’s closing apostrophe to Franklin Delano Roosevelt (here symbolized by Lord Byron’s George Washington) sounded like this.

Kandinsky, Busoni, and Schoenberg followed a demanding muse.

Schoenberg even said: “I do not think about the pubic.” But the Ode to Napoleon invariably ignites an

ovation – and so it did at the Phillips Collection.

August 26, 2019

Harry Burleigh and Cultural Appropriation – Take Two

The annals of the Harlem Renaissance include heated debate over the practice of turning African-American spirituals into concert songs.

Zora Neale Hurston Hurston heard

concert spirituals “squeezing all of the rich black juice out of the songs,” a “flight

from blackness,” a “musical octoroon.” She listed Harry Burleigh among the

offenders.

But without Burleigh there

would be no “Deep River” as sung by Marian Anderson.

Angel Gil-Ordonez, the inspirational music director of PostClassical Ensemble, calls Burleigh one of our “lost causes,” along with Bernard Herrmann, Lou Harrison, and Silvestre Revueltas — with Arthur Farwell coming up in October.

What Angel means, really,

that these are delayed causes – that Burleigh

will ultimately become known as an American musical hero, that Herrmann will

remembered for more than his supreme film scores, that Harrison will be widely

performed east of California, that Revueltas (notwithstanding being Mexican) will

take his place as a twentieth century master – and that Arthur Farwell’s “Indianist”

compositions, in parallel with Bartok abroad, will transcend their stigma of “appropriation.”

I am not sure what, exactly, “rich

black juice” might be, but there is a lot of it when Kevin Deas sings Burleigh’s

“Steal Away” – as he did last Thursday night in a PostClassical Ensemble

program we called “The Spiritual in White America.” It sounded like this.

That was at the Phillips Collection

– which in addition to its landmark collection of twentieth century American

paintings boasts a venerable music series situated in an intimate, wood-paneled

music room enhanced by a rotating selection of great visual art.

In such a space, the impact

of Burleigh’s settings – both solo and choral – was immense. On the same

program, we heard readings by Hurston, W. E. B. Du Bois and Antonin Dvorak

(whose assistant Burleigh was in New York’s National Conservatory). That is: we

sampled a debate over appropriation. In the ensuing discussion, a member of the

audience called this the most memorable music-education experience he had

encountered since the days of Leonard Bernstein.

Burleigh’s spiritual arrangements

(some of which deserve to be called “compositions”) were juxtaposed with remarkable

arrangements by composers black and white, including William Dawson and Michael

Tippett.

Hurston is correct: none of

these concert versions of plantation song evoke the wild grief and ecstasy of

enslaved human beings laboring under the lash of white America. She rightly misses

the “jagged harmony,” the dissonance and spontaneity of singing in the field,

where “each piece is a new creation.” Nor – as the African-American composer/impresario

Nolan Williams pointed out in an acute post-concert discussion – does the

spiritual in concert truly evoke the sheer devastation of stolen lives.

And yet, in live performance,

Burleigh’s relative simplicity and directness of expression impart a timeless

dimension. More than subsequent concert renditions, they manage to convey the immediacy

of the vernacular.

Take “Deep River.” It was first set down (in an 1877 Fisk Jubilee Songbook) as a “church militant” spiritual. So far as I am aware, the once famous black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was the first to capture “Deep River” for the concert hall. He slowed it down and “dignified” it as a 1904 solo piano piece. To my ears, the eight-minute Coleridge-Taylor “Deep River” is diffuse. And its decorum registers what Hurston called “a flight from blackness.” Burleigh’s final setting for voice and piano (1915) is by comparison singularly concentrated: thirty-one measures lasting less than three minutes. But everything is there. Even the chromatic harmonies, even the keyboard counter-melodies are radically concentrated. It attains an elemental force.

Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River” (Kevin Deas with Joseph Horowitz), preceded by Maud Powell’s 1911 recording of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s arrangement

Here is

Kevin Deas singing Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River” three days ago at the Phillips

Collection. It has been my privilege to accompany him in concert for some dozen

years.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers