Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 12

April 8, 2023

George Shirley — a Week-long Tribute

Thanks to John Spencer and Chamber Music Cincinnati, “George Shirley: A Life in Music” will be celebrated for an entire week in that city.

Sunday, April 9: George Shirley sings Easter Sunday spirituals at three Cincinnati churches.

Monday, April 10 (7 pm): George Shirley and I reprise “George Shirley: A Life in Music,” the program we presented last summer at the Brevard Festival, with video clips and live performances.

Tuesday, April 11 (7 pm): “Dvorak’s Prophecy.” A program based on my book, with more performances by George Shirley and myself, plus pianist Meishan Lin. (Dvorak American Suite; Harry Burleigh spirituals; Harry Burleigh “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” – a magnificent concert song, Burleigh’s valedictory, still barely known.)

Friday, April 14: George Shirley is soloist at the Cincinnati Symphony’s “Classical Roots” concert.

The Monday and Tuesday performances, at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, are free but require registration.

Further information here.

March 26, 2023

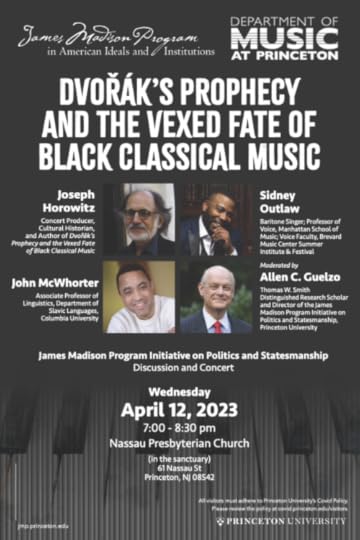

“Dvorak’s Prophecy” at Princeton April 12 with John McWhorter, Allen Guelzo, and Sidney Outlaw

“Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music” is the topic of an April 12 concert/lecture at Princeton University. I’ll be joined by cultural critic John McWhorter of the New York Times, Princeton historian Allen Guelzo, and baritone Sidney Outlaw – with whom I’ll perform spirituals and songs by Harry Burleigh. It’s free of charge and you don’t have to register. The venue is Nassau Presbyterian Church. The presenters are the Department of Music and the James Madison Program. We start at 7 pm.

McWhorter – who knows music and is a regular contributor to my “More than Music” programs on NPR – will address the significance of George Gershwin and the place of Black classical music. Guelzo – who knows music and is an occasional contributor to “More than Music” – will address the significance of Charles Ives, both with reference to the Civil War and the American cultural pantheon generally. Outlaw – a magnificent concert singer with roots in the Black church – will address African-American vocal composers now being rediscovered.

A special focus of attention will be Harry Burleigh’s “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” (1935), setting Langston Hughes. it’s one of the most memorable concert songs ever composed by an American. Turning Hughes’ poem upside down, it counsels faith and forebearance. Burleigh’s valedictory, it places him in a lineage with Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson, both of whom he mentored.

I will also have a piece on Burleigh in the April 1 Wall Street Journal, in which I write:

“Burleigh intended ‘Lovely Dark and Lonely One’ for Marian Anderson, whose renditions of Burleigh’s ‘Deep River’were indelibly her own. But Anderson chose not to sing ‘Lovely Dark and Lonely One.’ It is in fact a song personal to Harry Burleigh. It also happens to be Burleigh’s final concert song. If he therefore quit at the peak of his creative powers, his truncated odyssey bears comparison to other, more famous casualties of modernism: Charles Ives, Edward Elgar, Manuel de Falla, and Jean Sibelius, all of whom stopped composing when they discovered themselves aesthetically estranged after World War I.”

March 23, 2023

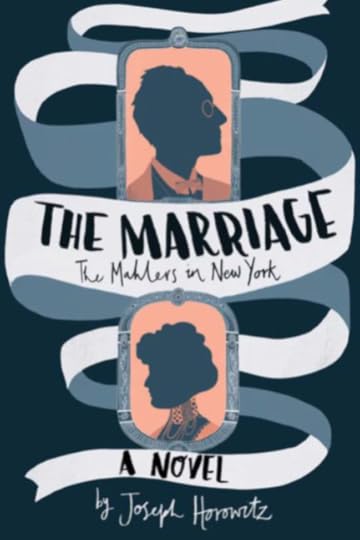

“Mahler in New York” (April 4) — Tickets Now on Sale

One of Gustav Mahler’s most powerful New York experiences was a funeral procession he watched from a hotel window. A fireman had drowned in a burning building. It is often surmised that the stark military drum commencing the finale of Mahler’s unfinished Tenth Symphony was a result.

Tickets are now on sale for “Mahler in New York” – an April 4 program combining music, film, and a foretaste of my new novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York. I’ll be reading my rendering of the fireman’s funeral – as it played out inside Gustav Mahler’s head.

The room – at the Dimenna Center on W. 37th Street — is small and may sell out quickly.

This singular event is the brainchild of Michel Galante, whose Argento New Music Project has long been a fixture on New York’s new-music scene. Alongside my reading, Michel will lead the premiere of his new chamber-ensemble orchestration of the second half of Mahler’s Tenth. And Hilan Warshaw will share an excerpt from his film-in-progress on Mahler in New York.

Michel writes that the manuscripts for the fourth and fifth movements of Mahler’s Tenth (both left unfinished) contain texts that “function posthumously as a diary into Mahler’s thoughts and feelings, expressing rank desperation and devastation at the series of crises and renewals he experienced during the last chapters of his life. What makes this music special is that he musically captures complex emotions previously unexplored in his other music and in the music that came before him.”

Here’s a taste of my reading, lifted from my new book:

He was working in bed, in pajamas, his correspondence propped on a board, when he heard from afar Chopin’s funeral march per- formed by parading winds. The impersonality of this familiar cere- monial rendition, with its thudding bass drum, its droning trumpets and lockstep clarinets, redoubled the music’s sad finality. He stepped to the window. Looking down to the right, he could see a massive cortege a dozen blocks away flanked by bare-headed throngs. His features lost their rigor and tears coursed down his creased and pallid cheeks.

The precise nature of this processional was at that moment of scant interest to him. Of course, he shuddered with memories of Putzi. But public rituals of mourning had all his life stirred him strangely. They were in fact written into the dirges of his symphonies. They resonated with the synagogue sobs and wails and with the folksong sadnesses that laced with the quotidian his layered musical language. He had even composed, to Alma’s dismay, a singular series of Kindertotenlieder, which she believed presaged Putzi’s fate. The sources of this morbid susceptibility were known and unknown to him. It was a topic that he had never meticulously pursued, broaching realms of unease that he resisted analyzing. Rather – in his mind, in his music – he preferred to submit to streams of thought and feeling half-conscious, half-subliminal.

He could now identify the horse-drawn casket. Red-uniformed firemen comprised the massive core of the processional, fronted by mounted policemen. The band uniforms were also police blue. It was the deputy fire chief who had drowned in the flooded basement of a burning furniture store. Alma had read about it in the Staats-Zeitung.

March 21, 2023

Re-Thinking the Concert Experience in South Dakota and Minnesota

Leningrad under Nazi siege, 1941-42

Leningrad under Nazi siege, 1941-42There was a time – the 1990s, when I was running the Brooklyn Philharmonic at BAM – when the practice of speaking from the stage at symphonic concerts was controversial, both among audiences and orchestra leaders. And people debated whether or not thematic programing was a good thing.

Those days are finally over. But the next step – fundamentally re-thinking the concert experience – lies largely dormant ahead.

I’m not referring to screens and new technologies, but to something more fundamental: programming. Every concert I’ve produced, beginning with those heady Brooklyn Philharmonic seasons, has been thematic. It works. The musical impact is strengthened. There is more to think about. Education and collaboration are facilitated. Museums curate thematic exhibits for these reasons.

One step beyond that is the narrative concert that tells a story – as with programs in which I recently participated in South Dakota and Minnesota. The South Dakota Symphony presented Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony linked to activities at two universities. “Dvorak’s Prophecy” at St. Olaf College linked to a second public event on cultural appropriation, a classroom visit, and meetings with individual students.

I also encountered a counter-example – a standard-format concert by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra that went nowhere.

I have often written about the South Dakota Symphony in this space. So far as I am aware, it’s our most genuinely innovative, most inspirationally forward-looking professional orchestra. It is also the happiest professional orchestra I know, and the most engaged. Its mission is defined and driven by its Music Director of twenty years: Delta David Gier, who in 2004 moved to Sioux Falls and proceeded to raise a family there. Gier’s signature initiative is the Lakota Music Project, which links SDSO to Indian reservations across the state. He also regularly showcases new American music. And he regularly tackles big repertoire: a Mahler cycle, the St. Matthew Passion (unabridged), Redes with Revueltas’s great score performed live — and now Shostakovich 7. More than a century ago, Theodore Thomas – whose touring Thomas Orchestra made the concert orchestra an American specialty – preached: “A symphony orchestra shows the culture of a community.” Gier’s South Dakota Symphony does that and more. It should become a national model.

Gier’s galvanizing reading of the Leningrad Symphony, three weeks ago, was preceded by a forty-minute “dramatic interlude” commencing with the lascivious trombone slides, from the opera Lady Macbeth, that got Shostakovich in big trouble with Stalin in 1936. The infamous Pravda editorial was recited. We moved on from there to the Fifth Symphony and its ostensible Socialist Realist contrition, thence to the horrific 872-day Nazi siege of Leningrad and Shostakovich’s legendary musical response. All this, with interpolated music, was co-scripted by Gier and myself. The Seventh Symphony followed after intermission.

The performance was attended by dozens of Music, History, and Political Science students bussed to Sioux Falls from South Dakota State University an hour away; they also took part in an hour-long post-concert discussion. In the days before and after that, I visited four SDSU classrooms. And the Dakota String Quartet (comprising principal players of the SDSO) visited with Shostakovich’s autobiographical Eighth String Quartet – which they contextualized, and also brought to the University of South Dakota an hour from Sioux Falls in the opposite direction.

For Mark Bertrand, the pastor of Sioux Falls’ Grace Presbyterian Church since 2017, the testimony of a German soldier, cited by Gier, underlined his experience of the long, inexorable crescendo climaxing the Leningrad Symphony. Using loudspeakers, the Soviets had broadcast Shostakovich’s symphony to the Nazi troops enveloping the city. A German soldier wrote afterward: ““It had a slow but powerful effect on us. The realization began to dawn that we would never take Leningrad. We began to see that there was something stronger than starvation, fear and weather – the will to remain human.”

Bertrand also told me: “I think that by the end of the evening – the forty-minute preamble about Shostakovich, Stalin, and the siege of Leningrad, the eighty-minute symphony itself – all of us felt a combination of elation and exhaustion. We had gone through something important together. Of course, the symphony crescendos to a point of elation. But you also feel the sheer duration of it all. I sensed a kind of joyful weariness. You know, I’m a cynical person by nature – and David and the South Dakota Symphony are constantly challenging that cynicism. They renew my confidence in the meaning of art.” Like many others, Bertrand found himself reflecting, as well, on Ukrainian resistance to Russian troops today.

I spoke with David Reynolds, Director of Performing Arts and Professor of Music at South Dakota State University, about the ongoing collaboration with the South Dakota Symphony. He said: “Finding a way to use the performing arts to bring these important stories to life – in this case, stories about World War II, about the siege of Leningrad — is a wonderful way to touch students who are growing up with social medica and other non-traditional means of communication. I’ve always been passionate about arts in general education. I know that the students in our Music Appreciation course are the folks that one of these days are going to be bank presidents, school board members – jobs that will decide the role of the arts in public and private schools, and funding for the arts, twenty years from now. It’s vital to open their eyes to experiences just like these contextualized Shostakovich concerts. To leave them thinking, ‘my life would be incomplete without the arts being a part of it.’ ’’

Magda Modzelewska, the SDSO principal second violist since 1998, is also a member of the Dakota String Quartet. She told me: “This is a very special orchestra and I have felt that from the beginning. I remember there was once a survey of job satisfaction in different professions. And [orchestral] musicians – their job satisfaction was the lowest. I have been very lucky – we don’t appear to have this attitude problem. There’s a sense of gratitude for what we do, of friendship and common purpose.“ She called Delta David Gier “a rare conductor with a big heart and a set of really solid values.” She called her work as a core participant in the Lakota Music Project “humbling . . . in Indian culture we’ve found such peace and good will.”

(My next NPR “More than Music” documentary, for the newsmagazine 1A, will be “Shostakovich in South Dakota” on April 24.)

* * *

Not long after my two weeks in South Dakota, I took part in a series of events at St. Olaf College based on Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. St. Olaf is famous for its choral program. It also boasts an exceptional student orchestra (that tours). The superb conductor, Chung Park, is new this school year; his predecessor for forty-one years, Steven Amundson, is a local legend.

I was invited to narrate a St. Olaf orchestral concert telling a story. The second half comprised Dvorak’s New World Symphony. The first half freshly contextualized that familiar work.

We began with Dvorak’s Slavonic Dance Op. 46, No. 3, composed in Prague, in direct juxtaposition with an excerpt from his American Suite, composed in New York City. Whereas the New World Symphony is a European symphony with an American accent, the American Suite, a year later, doesn’t “sound like Dvorak”; rather incredibly, it is bona fide American music. I introduced the suite’s third movement by correlating its three themes with minstrel dances, plantation song, and Dvorak’s desolate “Indian” mode – not an attempt to adapt Native American song, but a personal and compassionate evocation of the tragedy of Native America.

After that came William Arms Fisher’s “Goin’ Home” – his famous 1922 adaptation of Dvorak’s Largo, sung with orchestra by Emery Stephens of the St. Olaf faculty. Without a pause, Chung Park then launched “Hope in the Night” – the middle movement of William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1932). This work is a huge find, in which Dvorak’s 1893 prophecy – that “Negro melodies” would foster a “great and noble school of music” – discovers searing fruition. And I introduced the New World Symphony, on the second half, by citing four passages in which Dvorak found inspiration in Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.

Many in the audience, many in the orchestra, afterward said that their listening experience was transformed by this exercise in informed engagement.

While I was at St. Olaf’s, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra turned up with a mixed program including Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony alongside shorter works by Fanny Mendelssohn and Hummel. Comparisons were inescapable. Mendelssohn’s symphony was inspired by a visit to Scotland. The canopy of sorrow that magically distinguishes this work are captured in a letter home reading in part: “In the deep twilight we went today to the palace where Queen Mary lived and loved. . . . The chapel below is now roofless. Grass and ivy thrive there and at the broken altar where Mary was crowned Queen of Scotland. Everything is ruined, decayed, and the clear heavens pour in. I think I have found there the beginning of my ‘Scottish’ Symphony.” Much can be done with this information — especially for an audience of college students.

The online program note (there was no printed program) comprised two sentences. Nothing was said from the stage. The performance itself (sans conductor) was featureless. Both the South Dakota Symphony’s Shostakovich, and the St. Olaf Orchestra’s Dvorak, if less polished, were more energized, more distinctive. Chung Park’s smashing reading of the Slavonic Dance sang with trumpet vibratos and string portamentos. In the Leningrad Symphony, Gier masterfully shaped the long slow movement, challenging his players (in rehearsal) to give everything they could to the culminating reprise of the opening chorale theme. I have rarely heard such massed sonic intensity from a string choir.

Both the SDSO concert and the St. Olaf concert were livestreamed. My 26-year-old daughter watched the SDSO’s Shostakovich concert from New York City. She phoned me afterward. Were her friends to encounter “concerts like that,” she said, they would be converted to classical music.

The stakes are that high.

I take part in “Mahler and New York” via the Argento New Music Project April 4 in New York City. Then I’m with George Shirley and Chamber Music Cincinnati, April 10-11. Then April 12 at Princeton University: “Dvorak’s Prophecy,” with John McWhorter, Sidney Outlaw, and Allen Guelzo via the university’s James Madison Program.

To read Alex Ross in The New Yorker on the South Dakota Symphony, click here.

March 10, 2023

Bruckner and the Cellphone PS

Norman Lebrecht has picked up my blog on Bruckner and the Cellphone and posted it on Slippedisc.

You will find a torrent of responses. But the most interesting response I have received was from Norman himself, who wrote to say that cellphones do not intrude at symphonic concerts in Europe.

Something to think about.

March 9, 2023

Bruckner and the Cellphone

Last Sunday’s performance of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony by Christian Thielemann and the Vienna Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall was very possibly the peak concert experience of the New York season. And yet when it ended I discovered myself screaming.

Here is what happened:

Bruckner’s Eighth lasts eighty minutes and is exhaled in a single breath. It invites – it demands – a pact with the audience. It is communal. It cannot be fairly experienced in a living room.

On this occasion, Carnegie had been sold out for weeks. The audience was a marvel – if not fully inter-generational (not enough listeners under the age of thirty), it was remarkably international. It took Thielemann barely a moment to secure perfect quiet: 3,670 souls in thrall. He navigated the great structure with monumental assurance.

The last movement ends with a famous passage: the apocalyptic “coda.” Bruckner pauses for a long, capacious breath. Then he restarts his engines quietly, gradually – and with the unmistakable promise of a culminating event. In a compositional tour de force both ingenious and inevitable, he proceeds to pile all the symphony’s themes atop one another. This achieved, he drives a refulgent final thrust. Thereafter, Thielemann and the musicians froze. And so did everyone else save a jackass in the left balcony who felt entitled to bellow “BRAVO!!!” The moment was shattered. Thielemann reacted with visible consternation..

But there was worse: the curse of the cellphone.

Not long after the performance began, the little lights began appearing, raised high. The hall’s ushers dutifully raced hither and yon, up and down aisles, gesturing frantically. And the phones were put away.

Some clever listeners, however, realized that they could film the end of the performance – the famous coda – with impunity. There would be no time for intervening ushers.

With the pregnant beginning of the coda, I moved to the edge of my seat. I was sitting in my preferred location – center Balcony. (The sound is cleaner than downstairs and the sightlines are impeccable.) As it happened, one of the offenders was seated directly in front of me. Because the rake is steep, she held her phone high – blocking my field of vision with her bright miniature screen.

The ovation was deafening. To get her attention I touched her shoulder and screamed: “DO YOU REALIZE HOW DISTRACTING IT IS TO WHIP OUT YOUR CELLPHONE AND START FILMING?!”

This surprising distraction enfurIated her. She whipped around and yelled: “HOW DARE YOU TOUCH ME!!! HOW DARE YOU TOUCH ME!!!”

Mercifully, she was packing up and leaving. As she continued to shriek her displeasure, I advised her: “YOU SHOULD BE BARRED FROM THIS HALL!!! SCRAM! GET OUT!”

Reflecting on this experience, I discover that her behavior was less discourteous than it was selfish. As far as she was concerned, she was the only listener who mattered.

A recent book by Bill McKibbin is accurately titled The Flag, the Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at his Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened. McKibben has an answer. In the world of cellphones it is both a cause and an effect. He calls it “hyper-individualism.”

I cannot think of a purer example than the woman who filmed Bruckner’s coda and took it home as a memento.

(I will have more to say — much more — about 21st-century Bruckner in The American Scholar next Fall.)

March 7, 2023

You can now pre-order my new Mahler novel (and get 20 % off)

My forthcoming Mahler novel is now available for pre-order with a 20 per cent discount.

Related events:

April 4: “Mahler in New York.” A concert with film and readings (I’m reading from my book): Argento New Music Project, Dimenna Center, 7:30 pm

April 23: Colorado Mahlerfest webcast, 6 pm ET – I’ll be talking about why I have fictionalized the story of the Mahlers in New York, and what I’ve learned as a result.

April 29: Mahler Foundation webcast, 10 am ET – a Youtube conversation with the Mahler scholar Morten Solveg

May 20: Colorado Mahlerfest symposium, 3 pm Mountain time (Boulder, Colo.) – A talk on Mahler’s failure in New York: why it happened and what it meant.

June 17: “Einsamkeit,” presented by Peridance Contemporary Dance Company (NYC). – The premiere of a new music/dance piece by Igal Perry, setting Mahler and Schubert performances by JH and the bass trombonist David Taylor.

July 5 : Brevard (NC) Music Festival. A concert including “Mahlerei,” my adaptation of the Scherzo of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony as a concertino for bass trombone and chamber ensemble. With bass trombonist David Taylor.

TBA – American Purpose “Bookstack” podcast, with Richard Aldous

February 22, 2023

Shostakovich in South Dakota

I’m in Sioux Falls, where the South Dakota Symphony – to my knowledge, the most genuinely innovative American orchestra – is performing Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony Saturday night at 7:30 pm Central Time. A 30-minute preamble (which I’ve scripted) explores the extraordinary context of this work. It’s all being livestreamed via http://www.sd.net or http://www.facebook.com/sdsymphony

The performance links to two weeks of activity at South Dakota State University and the University of South Dakota – an educational experiment I cannot imagine implementing anywhere else.

“My Symphonies are Tombstones,” the “dramatic interlude with music” that begins the concert, starts with some really lascivious music from Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth – and the notorious Pravda editorial that resulted. Delta David Gier – the orchestra’s music director since 2004, and a Sioux Falls resident since 2005 – also samples the ending of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony in the course of exploring the ways in which this singular composer bears witness to history.

Composed during the terrible siege of Leningrad, Shostakovich’s Seventh rallied a nation. It was broadcast throughout the Soviet Union – and also to the front. A German soldier later testified: “It had a slow but powerful effect on us. The realization began to dawn that we would never take Leningrad. We began to see that there was something stronger than starvation, fear and weather – the will to remain human.”

I will be turning the entire “Shostakovich in South Dakota” exercise into my next NPR “More than Music” documentary, with commentary by the participating students and musicians – including members of the Dakota String Quartet, which performs Shostakovich’s autobiographical Eighth String Quartet on both campuses.

(This is the same Dakota String Quartet, comprising SDSO principal players, that made the world premiere recording of Arthur Farwell’s Hako Quartet, a landmark achievement in the Indianists movement Dvorak inspired and Farwell spearheaded; and it’s not kitsch.)

How I wish other orchestras could link to universities in this fashion, or so creatively strategize to maximize the impact of music in live performance.

(Next season, Gier and Emanuele Arciuli perform Lou Harrison’s Piano Concerto, a work frequently extolled in this space. The same program will incorporate a gamelan demonstration, exploring Harrison’s ingenious techniques of cultural fusion.)

To read a related blog on the South Dakota Symphony, click here

To read Alex Ross on the South Dakota Symphony in The New Yorker, click here.

February 13, 2023

“The Gershwin Moment” on NPR

To close my recent National Public Radio documentary “The Gershwin Moment,” I pose the following hypothetical: What if George Gershwin, a contemporary of Aaron Copland, had lived as long as Copland did – and died in 1988 at the age of 90 rather than in 1937 at the age of 38? I then turn to the music historian Mark Clague, who heads the Gershwin Initiative at the University of Michigan. Mark memorably responds:

“One of the most powerful experiences I had researching Gershwin’s music was at the Library of Congress looking through his letters – and I found one in which he was speculating about the projects he would undertake after Porgy and Bess. One of them was a symphony. It was like a punch to the heart to read about what George Gershwin might have done had he not died at the age of 38. It would have completely changed what we think of as American music. I was struck just the other day reading that the Metropolitan Opera had discovered that tickets for operas by living composers were selling better than the [European] classics. Had George Gershwin lived we wouldn’t just be discovering that in 2023. We would have obtained a vibrant living tradition of American composers being the main voices [in the US] for symphonic music and opera. We would have had an unbroken tradition going back to Rhapsody in Blue in 1924.”

I close by remarking:

“In the history of Western classical music, two composers famously died in their thirties: Mozart at thirty-five; Schubert at thirty-one. Had either lived a few decades longer, our musical inheritance would be immeasurably richer – but the fundamental trajectory of German music would have stayed much the same. Gershwin, in comparison, was a divine interruption, a comet from another planet. He was foraging in a New World musical wilderness whose distant borders were inhabited by figures as far-flung as Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, Irving Berlin, and Jelly Roll Morton. The poet Franz Grillparzer wrote a famous epitaph for Schubert’s grave: ‘The art of music here entombed a rich possession; but even far fairer hopes.’ Grillparzer, however, was misled: most of Franz Schubert’s most profound music was unknown at the time of his death, unpublished and unheard. With its anticipation of ‘far fairer hopes,’ Grillparzer’s German epitaph better suits America’s George Gershwin.”

You can hear “The Gershwin Moment” here. The other participants are John McWhorter, pianist Kirill Gerstein, and cultural historian Traci Lombre. The musical clips include three of my favorite historic Gershwin recordings: Ruby Elzy singing “My Man’s Gone Now” at the Hollywood Bowl Gershwin Memorial concert, Nina Simone singing “I Love You Porgy,” and the 1960 Soviet Rhapsody in Blue with Alexander Tsfasman and Gennady Rozhdestvensky. We also hear a rather rare clip of Gershwin talking and playing, Kirill Gerstein improvising a sublime cadenza in the Concerto in F, and Kenneth Kiesler leading the orchestra of the University of Michigan School of Music in a couple of excerpts from the original An American in Paris – music you’ve probably never heard before (including a different set of taxi horns).

As always, my thanks to my technical producer Peter Bogdanoff, and to Rupert Allman and Jenn White of “1A.”

A pertinent blog: “The Gershwin Threat”

LISTENING GUIDE:

00:00 Rhapsody in Blue, as recorded in Soviet Russia in 1960

4:12 — John McWhorter on resituating Gershwin in the story of American music.

8:55 — Ruby Elzy sings “My Man’s Gone Now” for the departed coposer

13:40 –Kirill Gerstein plays “I Got Rhythm”

14:30 — Gerstein performs and discusses his improvised cadenza in the Gershwin Piano Concerto in F

23:33 — Traci Lombre on Gershwin and Black America

26:20 — Gershwin plays “I Got Rhythm”

27:40 — Nina Simone sings “I Love You Porgy”

29:50 — “Music by Gershwin” on the radio (1934)

35:10 — Mark Clague on An American in Paris — taxi horns and sonata structure (with the University of Michigan Orchestra conducted by Kenneth Kiesler)

40:40 — What if Gershwin had lived as long as Copland (with comments by Mark Clague)

January 29, 2023

Michael Morgan, the Oakland Symphony, and William Dawson

Michael Morgan 1957-2021

Michael Morgan 1957-2021The death of Michael Morgan, last August 20, was a heartbreaking loss to American music. As music director of the Oakland Symphony since 1991, he was a singularly impactful conductor.

The evidence, as I discovered Friday night at an Oakland Symphony concert that in many respects invoked his memory, is a symphonic audience unique in my experience. “Diversity” is a term so over-used today as to lose all meaning. The dictionary says: “including or involving people from a range of difference social and ethnic backgrounds.” So variegated is the Oakland Symphony audience – in age, ethnicity, attire, and attitude – that it resists generalization. The resulting ambience, in the impeccably restored downtown Paramount Theatre, was casual, alert, appreciative, demonstrative. The downtown itself is funky, surprising, quiet, and beautiful – and devastated, economically, by the pandemic.

The program at Friday’s subscription concert was worthy of the audience at hand. The main offering was William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony – music I have extolled in this space and in Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. Triumphantly premiered by Leopold Stokowski in 1934 and subsequently forgotten, this 35-minute symphony is the real deal. It is certainly one of the most formidable ever composed by an American. As I’ve written: “If the symphony’s governing mold is European, Dawson retains proximity to the vernacular: he seizes the humor, pathos, and tragedy of the sorrow songs with an oracular vehemence.”

The conductor of the Oakland performance was Andrew Grams – new to me, and also new to the Dawson. The Negro Folk Symphony is easy for audiences – its emotional fortitude and depth register unmistakably. But it’s hard for orchestras. The textures are thick with incident. The trajectory is not straightforward but pliable, eventfully plotted. The rhythms are sharp, physical, lightning quick. Grams’ careful rehearsals resulted in a go-for-broke reading. The symphony’s most striking, most original moment – the second movement coda, with its threefold seismic throb of chimes and timpani – was bravely distended, even slower than on Leopold Stokowski’s wonderful 1963 recording. The impact stunned the eager audience.

Last summer I heard an equally memorable performance of the Dawson, quicker and more brilliant, led by Mei-Ann Chen at Houston’s Texas Music Festival. I see that the Philadelphia Orchestra, which gave the 1934 premiere (also with Stokowski), is at long last returning to the Negro Folk Symphony on February 2 and 3 under Yannick Nezet-Seguin. Performances will surely proliferate in seasons to come. We should quickly approach a moment when it will become possible to compare different understandings of Dawson’s complexly poised “portrait of a race.” Also: for young American composers aspiring to fuse the Black vernacular with concert genres, Dawson’s score could become a textbook. My Dvorak’s Prophecy mantra is: use the past. That’s how lasting results are obtained.

The first half of the Oakland program featured Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody for piano and orchestra – terrifically ignited by Sarah Davis Buechner. Like Dawson’s symphony, which feeds on spirituals, this jazzy confection fulfills the prophecies of Dvorak and W. E. B. Du Bois that “Negro melodies” would foster a vital and original American classical music.

During the Harlem Renaissance, however, Langston Hughes and Nora Zeale Hurston expressed misgivings about the prospect of a Black classical music. They worried that turning the African-American motherlode into symphonies and operas could prove “sanitizing,” “whitening.” The Oakland concert began with selections from Florence Price’s Folksongs in Counterpoint for string quartet, revisited by a string orchestra. Price’s polyphonic elaboration of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is the kind of Black classical music that recalls the apprehensions of Hughes and Hurston. It was my pleasure, in Oakland, to undertake a series of presentations in middle and high schools – schools musically enriched by a series of initiatives undertaken by the Oakland Symphony under Michael Morgan. I was partnered by a wonderful African-American soprano, Shawnette Sulker. Our program included Harry Burleigh’s arrangement for voice and piano of “Swing Low.” For Sulker, this and other historic Burleigh spirituals created opportunities for a selfless expression of sorrow and exaltation. They do not register as “sanitized.”

I am sure some will find my reservations about Florence Price gratuitous. Without a doubt, she is an important part of the story of American music. As I urge in Dvorak’s Prophecy, this is a story that impatiently awaits a genuine curatorial initiative by our major orchestras. The symphonies of John Knowles Paine, likewise, are an essential component of a narrative we need to know. They are not “masterworks.” But they lead, indispensably, to George Chadwick (whose witty symphonic scherzos already “sound American”), thence to the symphonies of Charles Ives and William Levi Dawson, in which native variants of a European genre discover fruition.

Daniel Weiss, in his up-to-date meditation Why the Museum Matters, documents the movement toward thematic exhibits some half a century ago – explorations necessarily infused with “new scholarship and didactic materials.” In the 1990s, I was the lucky beneficiary of Harvey Lichtenstein’s state-of-the-art Brooklyn Academy of Music, where innovation was a ceaseless priority. Curating “The Russian Stravinsky” for the Brooklyn Philharmonic, I engaged Moscow’s Pokrovsky Folk Ensemble, the late Stravinsky scholar Richard Taruskin, the art historians John Bowlt and Elizabeth Valkenier, the ethnomusicologists Dmitri Pokrovsky and Theodore Levin, and the conductors Dennis Russell Davies and Lukas Foss. There were two symphonic programs and a six-hour cross-disciplinary “Interplay.” Brutal folk rituals and pungent concert works were directly juxtaposed. The talks and discussions were heated, informed, and productive. The essays within the copiously illustrated program companion totalled 38 pages. The principal funder was the National Endowment for the Humanities. In short: it was, all of it, what museums do. This is the type of curatorial initiative that Black classical music deserves – and that Florence Price deserves, alongside Burleigh, Gershwin, and Dawson, among many others. There is a story here as yet unglimpsed.

As I have previously reported, George Shirley has precisely observed of Dawson’s symphony that it is a work that surprises at every turn – and that every surprise “sounds right.” Put another way: Dawson’s compositional skill and originality enable him to sustain an illusion of improvisation. And I would say the same of Gershwin. It is crucial.

But I digress. My memories of Friday’s concert are all of Gershwin and Dawson, and of an enthralling and empowering ambience inculcated over three decades by a musical leader who was equally a community leader. The Oakland Symphony has experienced a great loss. It faces a great challenge. Thanks to Michael Morgan, that challenge is at the same time ripe with opportunity.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers