Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 7

April 22, 2024

Are the Arts Inimical to our Democratic Ethos?

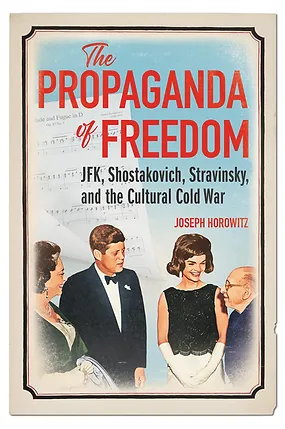

The starting point of my new book The Propaganda of Freedom is the core tenet of the cultural Cold War as prosecuted by the CIA and the Kennedy White House: that only “free artists” in “free societies” can produce great art. And yet this is a risible claim, self-evidently counter-empirical; I’ve dubbed it the “propaganda of freedom.”

An exceptionally thoughtful review has just materialized in the online magazine Fusion. The author is Robert Bellafiore, who writes:

“In The Propaganda of Freedom, Joseph Horowitz considers the history and influence of Kennedy’s argument and finds it harmful to freedom and culture alike, revealing an uneasy relationship between art and politics that any free society must grapple with. . . .

“Through his musical analysis and a broader history of the [Congress for Cultural Freedom] and cultural exchange during the Cold War, Horowitz seeks to protect both art and freedom from their cheapening . . .

“The tensions between artist and audience, and between artist and government, didn’t resolve themselves when the Cold War ended. What makes The Propaganda of Freedom more than just a compelling history is its illustration that these tensions will mark every free society, including ours today. For any American who is discouraged by the vulgarity and frivolity of contemporary culture and wishes for something better, the book raises difficult questions.”

Is our ethos of democracy and freedom somehow inimical to the life of the arts? Arts skeptics will argue that certain impediments are deeply rooted in the American experience. Certainly there is an impressive lineage of writings analyzing an American aversion to artists and intellectuals. Alexis de Tocqueville, nearly two centuries ago, observed among the citizens of the United States “a distaste for all that is old.” Assessing an expanded “circle of readers,” he discerned “a taste for the useful over the love of the beautiful,” for the “mass produced and mediocre.”

No less than ascetic Calvinism, Republican rationalism could spurn creative achievement. If popular government demanded a virtuous and pious citizenry, monarchies linked to sensuality and decadence. Were the arts an aristocratic luxury? Even the likes of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson – cosmopolites of humbling intellectual attainment – expressed ambivalence toward the cultivation of painting and sculpture. “Too expensive for the state of wealth among us,” opined Jefferson. Conducive to “luxury, effeminacy, corruption, prostitution,” wrote Adams. Both men well knew pre-revolutionary Paris.

Many decades later, American politicians of note included no Adamses or Jeffersons. Edward Shils, a widely influential sociologist, in 1964 regretted that in the US “the political elite gives a preponderant impression of indifference toward works of superior culture.” Two years before that, the historian Richard Hofstadter produced a Pulitzer-Prize winning study of Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. He adduced an enduring New World stereotype of the effete intellectual: impractical, artificial, arrogant, seduced by European manners. A related American stereotype, Hofstadter reported, holds the “genius” to be lazy, undisciplined, neurotic, imprudent, and awkward. He blamed democratization, utilitarianism, and evangelical Protestantism. These critiques registered aversion to the Red Scare and also to the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower, who once told Leonard Bernstein “I like music with a theme, not all them arias and barcarolles.”

An enduring philosophical argument against the American arts was launched by Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School. This was a tirade against the “atomized” premises of Anglo-American empiricists who in separating the individual from society spurned a vigorously “holistic” dialectic. “Affirmative” American culture was bland and homogenized – rather than bristling with “negative” attributes igniting an engaged interactive response. Packaged and merchandized for mass consumption, affirmative culture was a feature of twentieth century capitalism. Concomitantly, capitalist society embraced a mistaken notion of the artist as a distant actor, unfettered and autonomous. The very DNA of American democracy – its notion of “freedom” – was in the Frankfurt view a naïve myth.

The contemporary pertinence of all this philosophizing is everywhere around us: increasingly, our democratic world of social media and mounting, ever multiplying gadgetry swims in bits and pieces, in disconnected dots, in superficia and ephemera – an ontology of fragmentation.

For more of the same, see my current “American Scholar” essay “Ripeness Is All.”

For more on the Frankfurt School with reference to American classical music, see my notorious “Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American Culture-God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music” (1987)

April 18, 2024

Mahler on Solo Trombone — Coming Up at Colorado Mahlerfest This May

Writing in The American Scholar, Sudip Bose said of David Taylor playing Schubert’s “Der Doppelgänger”: “Not in my wildest imaginings could I have envisioned such revelatory and shocking interpretations. . . . The pathos was unrelenting, almost too much to bear. . . . Taylor’s Schubert performances have been haunting me ever since. I cannot get them out of my mind.”

It was I who introduced David Taylor to “Doppelgänger.” I have often partnered his unpredictable renditions of this and other late Schubert songs. Our Mahler/Schubert concoction, “Einsamkeit,” has been heard in New York and at the Brevard Music Festival. We’re now working up a version of Schubert’s ruthlessly despondent song cycle Winterreise.

The trek from late Schubert to Mahler is short and turbulent. Hence: Mahlerei, my concertino for bass trombone and chamber orchestra, created for Taylor and premiered at the Kennedy Center in 2022. A revised version, abetted by Daniel Schnyder, will be performed at Boulder’s ever- ambitious Colorado Mahlerfest on May 15.

I’ve taken the Scherzo from Mahler’s Fourth Symphony and turned it into a kind of Yiddish chant, with the melodic line – which Mahler shares generously – piled onto Taylor’s horn as a bumptious moto perpetuo. There are sundry surprises along the way. And I must say: it works. (The Washington Post called it “a strange and strangely satisfying experiment.”)

This year’s 37th annual Colorado Mahlerfest explores two relationships: Mahler and Schubert; Mahler and Richard Strauss. There are six concerts, a symposium, and a mountain hike. The repertoire includes Schubert’s Death and the Maiden Quartet (adapted by Mahler), Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, and Strauss’s Alpine Symphony. Mahlerei kicks off the festival on a program otherwise mainly exploring childhood, with music by Schubert, Wagner, Humperdinck, Mahler, and Richard Strauss.

I call my symposium talk, on Schubert and Mahler, “Taverns in Heaven” – a reference to the intrusion of a Bierhaus zither midway through the sublime Andante of Schubert’s E-flat minor Klavierstuck (which I am eager to perform). I’ll also be examining Mahler’s annotated Vienna and New York scores for Schubert’s Ninth, which (on the podium) he turned into something utterly and provocatively Mahlerian.

Many essays in this space have griped that today’s conductors are seldom bona fide “music directors.” Colorado Mahlerfest is curated by a gifted conductor who is also a writer, a thinker, and an artistic administrator: Kenneth Woods, who (though American) serves as principal conductor and music director of the English Symphony Orchestra in Worcester, UK.

In 2026, the Mahlerfest topic will be “Mahler the Man” and the festival events will include a professional staging of my play The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (a spin-off from my recent novel with the same title).

You can read more about Colorado Mahlerfest here.

You will find the complete 2024 festival schedule for this May here.

April 12, 2024

Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River” of Common Humanity on NPR

If you’ve ever heard Marian Anderson sing “Deep River,” you’ve heard an immortal concert spiritual by Harry Burleigh. His name won’t appear on the youtube captions – and yet Burleigh’s “Deep River” isn’t a mere arrangement.

I unpack the genesis of “Deep River” – its surprising origins as an obscure “church militant” spiritual, its indebtedness to Antonin Dvorak, its subsidiary theme composed by Burleigh himself – on the most recent “More than Music” feature on NPR: “’Deep River’: The Art of Harry Burleigh.” The performances (other than Marian Anderson’s) were recorded in concert by the exceptional African-American baritone Sidney Outlaw. It was my pleasure to be the pianist.

The show argues that Burleigh was a major creative force – more than the pivotal transcriber of spirituals as concert songs. In particular, we present his final art song – “Lovely, Dark, and Lonely One”(1935) – as his valedictory: not merely one of the supreme concert songs by an American, but an encapsulation of Burleigh’s life philosophy. It takes an eloquently impatient Langston Hughes poem, and turns it into an expression of hope and faith. “Burleigh consistently refused to participate in movements he considered separatist or chauvinistic,” writes Jean Snyder in her Burleigh biography. He believed that artists, not politicians, would most effect progressive change. “They are the true physicians who heal the ills of mankind,” he wrote. “They are the trailblazers. They find new worlds.” Our performance of this song, at Princeton University last year, is a little slower than other versions; its interior life (the climax is a pregnant silence) felt deep and true.

Burleigh’s own life story is a parable of faith: his patience was rewarded. As I remark on NPR: “When Harry Burleigh arrived in New York, its leading classical music institutions were segregated. Eight years later, in 1900, a ‘race riot’ erupted in the Tenderloin District. But New York was at the same time a city of opportunity for Harry Burleigh. And the opportunities did not merely arise in spite of his skin color; sometimes, they materialized because – dignified and composed — he was self-evidently a young Black American unusual in talent, character, and promise.”

In New York, Antonin Dvorak made 26-year-old Harry Burleigh his assistant. Jeannette Thurber, the visionary music educator who invited Dvorak to lead her National Conservatory, was part of a community of cultural leaders who – like Dvorak and W. E. B. Du Bois — looked to Black America for direction. Not long after Dvorak arrived, she added a department “for the instruction of colored pupils of merit” with free tuition. The conservatory soon acquired 150 Black students – out of a student body totaling 750. Meanwhile, Henry Krehbiel, the most influential New York music critic, turned himself into what would later be called an ethnomusicologist, studying vernacular music from all over the world – including the music of Native America, and of Africa. In the New York Tribune, Krehbiel wrote: “That which is most characteristic, most beautiful and most vital in our folk-song has come from the negro slaves of the South.” Krehbiel and Burleigh would become friends and allies.

When we observe that, beginning with “Deep River” in 1913, Burleigh’s spirituals were instantaneously popular among vocal recitalists – that means they were being sung by famous white recitalists. But over the course of the 1920s, Burleigh himself became an immensely popular black recitalist.

In the long view, Burleigh commences a high lineage of Black vocalists whose renderings of the songs of Black America are buoyed by a courageous optimism. His first two great successors, both of whom he knew and admired, were Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson. Closing the NPR show, I ask: “Is Burleigh’s ‘deep river’ of common humanity a thing of the past? Let’s hope not. Here’s a Dutch student chorus singing Harry Burleigh.”

LISTENING GUIDE:

Performances by Sidney Outlaw and JH recorded in concert at the Newark School of the Arts (with thanks to Larry Tamburri), and at Princeton University (presented by the James Madison Program, with thanks to Allen Guelzo):

6:00: “Deep River”

10:10: “Sometimes I Feel like a Lonely Child”

22:45: “Lovely, Dark, and Lonely One”

25:31: “Steal Away” —

April 11, 2024

“Ripeness is All” – What May Be the Fate of Classical Music’s New Superstars?

Yunchan Lin

Yunchan Lin

Today’s biggest controversy in classical music is the Chicago Symphony’s appointment of Klaus Makela, who will become music director in 2027-2028. He will concurrently take over Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra – one of the half dozen most eminent European ensembles. He will be all of 32 years old.

No one can reasonably dispute Makela’s precocious talent. The attendant outcry takes various forms, of which the trickiest and most momentous is that his interpretations will lack “ripeness.” What, exactly, does musical “ripeness” connote? How is it manifest in performance? And is it imperiled by our ever accelerating world of social media and AI?

My ruminations — today published online by The American Scholar – lead me to Wilhelm Furtwangler and Claudio Arrau (who once remarked to me: “I’ve always been told I’m a ‘late developer.’”). I write of Arrau’s 1976 recording of Liszt’s “Chasse-neige” that “it jars open a bygone world of feeling and experience both conscious and subliminal. It exudes a veritable elixir of memory. Could any young pianist or conductor accomplish such a feat?”

Thence to Van Cliburn, who peaked at the age of 23, and to the winner of the most recent Cliburn competition: Yunchan Lin, now twenty years old. I write: “He has catapulted into a major international career. As it happens, one of his acclaimed competition performances was of Liszt’s ‘Chasse-neige.’ . . . His rendition is riveting — never glib, never superficial. But it would be vain to look for anything like the scope of Claudio Arrau’s reading. Arrau’s Liszt echoes and re-echoes through corridors of time, a performance for the ages.”

I also have occasion to recollect the Cliburn Competition’s most esteemed gold medalist: Radu Lupu – in 1966, when Lupu was 21 years old. “To the surprise and consternation of the Cliburn Foundation, he had pocketed his first prize and returned to Russia, refusing to undertake the high-profile concert tour prepared for him. Suppose that Klaus Makela had told his manager Jasper Parrott: Thank you very much, but I am not prepared to take over two of the world’s most prominent orchestras. That was Radu Lupu.”

My ultimate topic is the erosion of cultural memory:

“Socially accelerating atoms of human experience today undermine all previous understandings that art is necessarily appropriative; chaotically askew, they support the illusion that, locked in our disparate identities, we cannot know or speak for one another. What is more, a privatized, atomized lifestyle promotes neither arts patronage nor production. Rather, its diversion mode is the soundbite: particulate cultural matter; stranded arts particles. . . .

“Commensurately, cultural memory – for untold centuries, a precondition for creativity and appreciation of the creative act – risks becoming a stack of flashcards processed as media clips. Will sustained immersion in lineage and tradition remain an organic prerequisite for composition, interpretation, and reception?

“Gloucester, in King Lear, counsels: ‘Ripeness is all.’ Never has Shakespeare’s observation more resounded as an admonition.“

You can read the whole thing here.

To read Alex Ross in The New Yorker on the Makela appontment, click here.

April 2, 2024

The Chicago Symphony Lands Klaus Makela

It’s now official: Klaus Makela will become the next music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, beginning in 2027-2028. He’ll conduct fourteen weeks of CSO concerts of which four will be on tour. He’ll concurrently become music director of Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra. He’ll retain relationships with the Oslo Philharmonic and the Orchestre de Paris. He’ll be thirty-one years old.

Makela is a big catch, the hottest young conductor around. But the initial response has been predictably mixed. An influential music critic of my acquaintance calls the Makela appointment the “most hairbrained” development he has yet witnessed in American classical music. Norman Lebrecht, on his ever-popular slippedisc blog, writes that Chicago has entered into “a raw deal.” An email that arrived this morning from a leading European artists’ manager reads: “[Chicago’s] mediocre management is unable to produce any vision for the future, so they are entrusting the ‘golden boy’ who’s supposed to rescue the entire music industry. Makela perfectly serves a music institution without a purpose. Until the next sensation comes along.”

Many blame this new norm on Ronald Wilford, who at Columbia Artists Management created the “jet-set conductor” as a signature of career status. That’s become such a ubiquitous template that it’s worth a moment of reflection.

Arthur Nikisch is widely regarded as the leading symphonic conductor of his generation, based in Germany. Earlier in his career, however, Nikisch was conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for four seasons (1889-1893). That meant that he led 388 of the orchestra’s 398 nonsummer concerts, including 196 on tour to 32 American cities. There were no airplanes. There were no “guest conductors,”

The Chicago Symphony had two music directors during its first half-century: Theodore Thomas (1891-1905) and then Thomas’s assistant Frederick Stock (1905-1942). That they were both German-born conferred identity – and a Germanic fundament remained long in place, governing repertoire and sonority. Thomas and Stock were Chicago fixtures. As I remarked in an earlier blog: “Stock’s commitment to the Midwest (which he toured extensively) was absolute, his popularity immense. Touting (from the stage) the ‘I-will spirit of Chicago,’ he spurned prestigious offers to relocate northeast. He implemented concerts targeting ethnic neighborhoods with seats costing fifteen to fifty cents. He led his own children’s concerts. He inaugurated outdoor summer concerts at Grant Park. (And I could go on.)”

Theodore Thomas’s credo — “An orchestra show the culture of the community” – loudly re-echoes today when American orchestras are quite suddenly cognizant that they lack local roots. I have often extolled the South Dakota Symphony in this space because its Lakota Music Project, and kindred initiatives, define it as South Dakota’s orchestra. Its music director, Delta David Gier, moved to Sioux Falls and raised a family there.

Makela’s appointment self-evidently has nothing to do with Thomas’s credo. Rather, it was largely driven by the enthusiasm of the Chicago Symphony musicians. And doubtless there is a feeling that a young conductor will entice young audiences.

That Makela is an exceptional baton-wielder is unquestionable. I heard him conduct Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony with the New York Philharmonic in December 2022 and wrote: “Makela’s Tchaikovsky, while not profound, proved terrific. This fellow must have been born with a baton in his crib. His style of leadership is both commanding and spontaneous. His imprint is personal. I concede that his Pathetique is (alas) more about drama than about pain; but the drama – its nuanced ferocity – carried the day. He has the confidence and authority to listen and respond in the moment to the musicians, both individually and collectively; to the vicissitudes of musical argument and expression. His is a bewildering talent.”

But – as I later added – none of that speaks to Makela’s capacity for institutional leadership. It’s demonstrably risky to entrust musicians to choose their own “music director.” A notorious instance: the New York Philharmonic players wanted Loren Maazel and they got him, in 2002. But Maazel, a famously virtuosic conductor, projected no institutional vision. And he left no legacy.

Assessing that Makela Pathetique in New York, I further wrote: “If he were fifty years older . . . he would probably be capable of extracting a more tragic reading of the Pathetique Symphony. For me, the supreme recording of this work was made by Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Berlin Philharmonic in 1951, courtesy of Radio Cairo. . . . It has little in common with Makela’s thrilling rendition the other day in New York.” Conductors ripen no more rapidly than other human beings do.

Another thing: conductors with a gift for grasping and leading “the culture of the community” are not likely to be young conductors; they’re people like Gier and the late Michael Morgan, in Oakland, with a certain amount of life experience behind them. It took Gier more than a decade of patient negotiation to clinch his orchestra’s charmed relationship to half a dozen Indian reservations.

Chicago’s decision to hire Klaus Makela will now inescapably be juxtaposed with Esa-Pekka Salonen’s resignation in San Francisco – because Salonen is a bona fide music director. The Makela appointment, whatever else one makes of it, rejects fundamental change. It will come sooner or later. It has to.

P.S. — My “More than Music” NPR feature on music directorships, citing South Dakota, is here. The commentators include the New Yorker‘s Alex Ross, who says: “There’s just a tremendous amount of caution, a tremendous amount of groupthink, in the orchestra world.. . . For a music director to carry off an ambitious project, you have to be there. You have to be on the scene, persuading people, interacting with them, listening to their ideas. Not just communicating your own. Building a sense of cooperation. You cannot do that as effectively if you’re flying in for two or three weeks, and another couple of weeks in the winter, and another two weeks in the spring. I find it a bit outrageous that music directors are so highly paid to begin with for one job – and then you find them holding a second or even a third position with exorbitant salaries in those places as well. This, of all things, is something the orchestra world should really be thinking about: drastically revising our idea of who a music director is, what their job entails.”

For more on Thomas, Stock, and Chicago, see my Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall (2005).

March 29, 2024

Mulling Salonen’s Resignation — Take Three: Harvey Lichtenstein and BAM

Harvey LIchtenstein (1929-2017)

Harvey LIchtenstein (1929-2017)Here are a couple of responses to my latest blog, mulling Esa-Pekka Salonen’s resignation as music director of the San Francisco Symphony:

–From a major European artists’ manager of long experience: “Over a period of decades, I have witnessed a progressive decline in the quality of leadership in the music business. Cultural institutions today prefer to attribute failure to excessive costs — not lack of purpose.”

–From Karen Hopkins, Harvey Lichtenstein’s indispensable aide-de-camp during the glory days of BAM: “Alas, there was but one Harvey. The key was not only his unlimited love for artists, it was his courage — something in short supply at this moment.”

A few days ago I told a Harvey Lichteinstein story about artistic vision — how in half an hour he resolved to take the entire Mariinski opera company to BAM for four performances. Here’s another Harvey story: one day the fire alarm went off and the building emptied. As we were the last to leave, I ran into Harvey in the BAM lobby. He said to me: “I hope the place burns down.”

The critic Winthrop Sargeant once summarized the force of Arturo Toscanini’s leadership of the New York Philharmonic as a “psychology of crisis” and likened the members of Toscanini’s orchestra to persons trapped in a sinking ship, pursuing a prodigious course of action out of desperation. At BAM, the Thursday morning meeting of department heads in Harvey’s office was a weekly ritual. The main event was invariably the BAM budget: a page of numbers, of which the ones that mattered showed updated income and expenses versus projections for the season. The hot seats were occupied by the marketing director and director of finance. A self-conscious congeniality failed to mask a mood of exigency.

Today, the American arts are ever more in crisis – the building is actually burning. On the fund-raising side of things, the wealthiest Americans are less likely to care about the arts. Our major charitable foundations remain in thrall to an equation likening the arts to instruments of social justice – a naïve disorientation. Two years ago, I interviewed some of the major players in this drama, among whom the wisest counselled patience: the pendulum will swing back. It hasn’t yet. I previously referenced the resulting article, in The American Purpose; here it is again, freshly pertinent.

Whatever I was able to achieve running the Brooklyn Philharmonic was abetted by major grants from the Mellon, Knight, Hearst, and Rockefeller Foundations – not one of which retains much interest in saving classical music. (We were also the first orchestra ever to be supported by the NEH – which remains an invaluable resource for orchestras ambitious to become mission-driven.) The frustrations of the foundation community (which I had occasion to witness first-hand) were entirely understandable: American orchestras have chronically resisted innovation. But an enlightened policy of selective support is more urgently needed than ever.

And of course audiences are dwindling. Here is another set of issues even more vexing: the impact of social media and shrinking attention spans, of what the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls “social acceleration,” of what I call the erasure of cultural memory. In my most recent book, The Propaganda of Freedom, I address the relationship between the artist and the state — and make a case for vastly increased federal support. There is at present no political will for that – indeed there are no national spokespersons of prominence for the arts. As I ponder in The Propaganda of Freedom, it’s a little known fact that the day John F. Kennedy died, the morning edition of the New York Times announced that he would be appointing a member of his inner circle, Richard Goodwin, to lead a new council on the arts. Nothing like that ever happened. It greatly matters now.

And all of this makes arts leadership the more challenging – and, arguably, visionary leadership the more elusive.

What, finally, is one to make of the ongoing SFSO controversy? Is it some form of incipient scandal that titillates a crowd? Or might the avalanche of responses I’m getting signal a constructive moment? Here’s a weathervane: according to rumor, the Chicago Symphony is about to announce its next “music director,” succeeding Ricardo Muti. This is an orchestra which, during its first half century, had only two presiding conductors: Theodore Thomas (1891-1905) was succeeded by his assistant Fredrick Stock (1905-1942). Both became fixtures in the cultural life of the city. Neither had conflicting commitments elsewhere. Thomas began as a legendary barnstorming educator; his Chicago initiatives included “workingman’s concerts.” Stock’s commitment to the Midwest (which he toured extensively) was absolute, his popularity immense. Touting (from the stage) the “I-will spirit of Chicago,” he spurned prestigious offers to relocate northeast. He implemented concerts targeting ethnic neighborhoods with seats costing fifteen to fifty cents. He led his own children’s concerts. He inaugurated outdoor summer concerts at Grant Park. (And I could go on.)

Will today’s Chicago Symphony opt for an institutional leader? Or will I follow today’s pack and choose a young conductor already spread thin? And if the latter, where will leadership reside?

March 27, 2024

Mulling Salonen’s Resignation — Take Two

In response to the resignation of Esa-Pekka Salonen, the San Franciso Symphony has now issued a statement denying disagreement over artistic goals – Salonen’s cited reason for quitting. Rather, according to the board, cutbacks in Salonen’s distinctive programing initiatives were mandated “solely by a lack of immediate financial resources.”

Mulling Salonen’s resignation in this space a day ago, I stressed that I know next to nothing about what actually happened in San Francisco. But I know enough to offer some context – which I did, reflecting on the rarity of full-service music directors like Salonen. Conductors possessing institutional vision are bound to incur “extra” costs and, in the short run, seem riskier in every way.

I cannot help recalling my experiences a couple of decades ago working for Harvey Lichtenstein, who made the Brooklyn Academy of Music the pre-eminent performing arts venue in the Western hemisphere. He was a man who, so far as I could tell, not once discovered that he lacked “financial resources.” Rather, Harvey would excitedly decide what he wanted to do and instruct his legendary development director, Karen Hopkins, to find money for it.

Harvey’s signature initiative, the Next Wave Festival, became a prototype for arts programming across the nation. But there was only one BAM. Certain lessons can be learned from that – not merely about the purposes of art, but about the means of production.

The first, and most obvious, is the importance of individual vision and initiative. That Lichtensein was known to all as “Harvey” was less a sign of affection than of familiarity – with Harvey’s easy charm, his volcanic temper, and above all, his unrelenting intensity. It was Harvey who had beginning in 1967 single-handedly transformed a moribund facility in an obscure neighborhood. His formula was to draw audiences from Manhattan by offering what Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center did not. His first BAM season included the long delayed New York premiere of Alban Berg’s Lulu, conducted and directed by Sarah Caldwell; the first New York season ever afforded Merce Cunningham, the maverick choreographer long associated with John Cage; the return from European exile of the Living Theatre of Julian Beck and Judith Malina; and Robert Wilson’s state-of-the-art epic The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud. Lichtenstein, in short, was America’s last great performing arts impresario. (Unless it was Joe Papp.)

Here is a Harvey Lichtenstein story: we went to St. Petersburg for Valery Gergiev’s 1994 Rimsky-Korsakov festival at the Mariinsky Theater. This was years before Gergiev was a household name in classical music. Our first night was an opera wholly new to both of us: The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh. After the first scene, Harvey slapped my knee and announced, “I’m bringing this to BAM.” And he did – conductor, orchestra, soloists, chorus, sets and costumes for four performances in 1995. This was New York’s introduction to the Mariinsky company, and to an opera sometimes called “the Russian Parsifal.” The New York Times panned it and the run sold poorly. Harvey had a guarantor to make up the deficit.

In the years I worked at BAM, Harvey also fell in love with France’s Zingaro Equestrian Theater, which required bringing a company of twenty-six horses across the Atlantic and constructing a circus tent in lower Manhattan. He was enamored of Arianna Mnuchkin’s Les Atrides, a series of Greek dramas so elaborately re-imagined that he had to refit a Brooklyn armory to house it. A favorite book of Harvey’s was Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King, whose protagonist is plagued by an interior voice repeating the words “I want!”

My job was running the Brooklyn Philharmonic – then the “resident orchestra” of BAM. Prior to my arrival, the BPO had lost over two-thirds of its subscribers over the course of two seasons. As there was nothing more left to lose, Harvey gave me a free hand. My most expensive undertaking was a “Russian Stravinsky” festival including two symphonic concerts (different programs a day apart) and a six-hour Sunday “Interplay.” I brought the Pokrovsky Folk Ensemble from Moscow to perform source rituals for The Rite of Spring and Les noces. I assembled a coterie of feuding scholars including the late Richard Taruskin, whose insistence that Stravinsky was “the most Russian” of all composers, and also “an inveterate liar” who falsified his artistic past, anchored these and other events thematically. We also produced a 60-page illustrated program book (which won an ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award). I did not think to inquire where I would find the money – but I did.

During my tenure the BPO audience more than tripled and funding-raising increased exponentially (in those days, major American philanthropies supported bona fide classical music initiatives — that’s over now, a crucial story in itself). With the exception of Gidon Kremer, I engaged no celebrity soloists. I hugely benefited from access to BAM’s audience and reputation. But good things happened in great part because the BPO was self-evidently mission-driven. It was different from other orchestras.

And that’s the first thing I noticed about the San Francisco Symphony when a few months ago my daughter moved to the Bay Area and I had a look at the subscription season online. You could delete every performer’s name – every conductor, every soloist — in that 2023-2024 brochure and the San Francisco Symphony would still retain its own brave identity. Try doing that with another big American orchestra and see what you come up with.

March 26, 2024

What’s an Orchestra For? — Mulling Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Resignation from the San Francisco Symphony

The resignation of Esa-Pekka Salonen as Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony is dominating classical-music news because Salonen made no secret why he quit: a falling out with the board over his elaborate artistic plans and their cost. I have no first-hand knowledge of any of this. What I do know is that Salonen is not merely a conductor; rather, he is – a rare species today – a full-service music director with a vision and the means to realize it.

That’s what he showed in Los Angeles, where he shaped the Philharmonic as a cultural institution distinctive to southern California and in synch with contemporary cultural mores. He looked for Americans he could champion and came up with two first-rate West Coast composers – John Adams and Bernard Herrmann – and a magnificent Mexican: Silvestre Revueltas. He inquired into the LA sojourns of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Theodore Thomas, the founding father of the American orchestra a century and a half ago, said “a symphony orchestra shows the culture of the community.” That’s what Salonen was about.

Music directors who are more than conductors are ever in short supply, and never more than today when a hyperactive international career seems to certify a conductor’s importance. In this space, I have often extolled Delta David Gier, whose Lakota Music Project makes his South Dakota Symphony matter to South Dakota. Gier moved to Sioux Falls and raised a family there.

Salonen’s departure from San Francisco – assuming that loud protests from his own musicians, among many others, have no effect – resonates with a 1950 Boston Symphony debacle, and also controversial board decisions in New York and Baltimore: stories that may be currently instructive.

If ever there was an exemplary music director of an American orchestra it was Serge Koussevitzky, who not only made the Boston Symphony his own but defined its mission for Boston and America. His long tenure (1924-49) coincided with a surging modernist moment – led by Aaron Copland – supporting a fresh identity for American concert music. Koussevitzky not only declared that “the next Beethoven vill from Colorado come” – he in effect created the Tanglewood Festival as an American music laboratory. You may well think: What a legacy! But Tanglewood today is nothing like the Tanglewood Koussevitzky envisioned and realized. That Tanglewood ended the day the BSO board named Charles Munch his successor. Koussevitzky had urged the board to appoint his protégé Leonard Bernstein. Leaving aside the question of whether Bernstein at 31 was ready for such an assignment, he was in all other respects the ideal choice: securing an American classical music was his raison d’etre. He was even a Harvard graduate, a Massachusetts native.

The late Robert Freeman, whom I was privileged to know, was the son of the BSO’s longtime principal double bass. Henry Freeman served under Koussevitzky, then Munch, then Erich Leinsdorf. With each appointment, he told his son, the orchestra declined. Freeman was probably mainly reflecting on the standard of performance. (In a recent blog about the BSO, I had occasion to embed Koussevitzky’s peerless world premiere broadcast of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra.) Commensurately, the Boston Symphony lost its way. In truth, it has never recovered from the board’s 1950 decision.

And so Bernstein instead wound up in as music director of an orchestra for which he was less suited. The New York Philharmonic had never been mission-driven. Rather, it was misruled for more than three decades by a powerbroker – Arthur Judson — who frankly believed that “the audience sets taste.” Here was a case where a symphonic board itself stepped up in quest of an institutional mission. It fired Judson and, in the same salvo, ousted its music director: Dimitri Mitropoulos, who happened to be a conductor of genius. And Mitropoulos had earlier pursued a brave vision in Minneapolis – a prerogative denied him in New York by Judson’s stranglehold on artistic policy. In any event, when Bernstein took over and declared that he wished to begin with a historic survey of American music, the Philharmonic board passionately approved.

An initiative like that would have resonated in Boston. In New York, it was too late in the day and Bernstein left after a mere ten seasons. His preferred successor, one understands, was another conductor/composer/pianist: Lukas Foss. Foss was an astounding musician (I worked with him at the Brooklyn Philharmonic). It is little recognized that, however incidentally, he was one of the supreme American pianists of his generation. On the podium, his unconventional methods inspired many instrumentalists and alienated others. In any event, the Philharmonic opted instead for Pierre Boulez, who had nothing in common with Leonard Bernstein or Bernstein’s American vision. After that came Zubin Mehta, Kurt Masur, Lorin Maazel, Alan Gilbert, Jaap van Zweden, and now Gustavo Dudamel – an eclectic list resistant to lineage or tradition.

But the most startling conductor appointment in recent American decades came in Baltimore in 1998. David Zinman, a bona fide music director, had turned the orchestra into an important platform for American music. He also had a radically fresh take on Beethoven. And he was a gifted advocate whose singular “Casual Concerts” revealed a zany comedic gift. Zinman was succeded by a major Russian conductor: Yuri Temirkanov. That was a startling coup. At least as startling, it was a rebuff to David Zinman and everything he had achieved. Zinman renounced his “Conductor Laureate” status in 2001.

Beset by conductors, lacking music directors, our major American orchestras today struggle to define what they’re for and how they connect to the changing cities they serve. Perhaps the most distinguished exception, proving the rule, was the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Mark Swed, the Los Angeles Times’ longtime chief music critic, chimes in valuably here.

I deal in detail with Koussevitzky, Mitropouos, Judson, and Bernstein in Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall (2005).

March 22, 2024

Making Alma Mahler “actually seem like a real person”

The new German edition of “The Marriage,” from Wolke Verlag — with an ingenious cover

The new German edition of “The Marriage,” from Wolke Verlag — with an ingenious coverWhen I embarked on my novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, I felt I possessed a pretty good understanding of Gustav, and none at all of Alma. Nor are the various biographical treatments of Alma adequate – she escapes portraiture, and the basis of her legendary allure remains inscrutable. My only way forward was to endeavor to experience Mahler’s glamorous spouse, and her bewilderingly new surroundings, as best I could. As I have earlier testified in this space, I learned the most when juxtaposing her with women of high professional achievement – in particular, with the Wagnerian soprano Olive Fremstad (the Callas of her time) and the young Natalie Curtis, who documented the music of Native America. In these encounters, as I re-imagined them, Alma clarified her insecurities. And of course in narrating the volatility and vulnerability of her husband (my book is not hagiography), I incidentally rendered Alma’s vicissitudes more understandable.

But it has come as a complete surprise that all reviews of The Marriage discover something like a breakthrough account of Gustav Mahler’s wife. The latest, by Kenneth Woods (a gifted Mahler conductor and scholar) in The American Purpose, reads in part:

“In a novel of so much value, the central triumph is not Horowitz’s ability to humanize Mahler, but to have provided readers—for the first time in my experience—with a nuanced, believable, balanced, and compelling portrait of Alma Mahler. Like her husband, Alma’s was a complex and contradictory personality, and this has made it easy for writers to appropriate her for their own ends.

“To some, Alma remains the villain in Mahler’s life story—the woman who broke his heart and his health, and whose writings were so full of misleading and dishonest details about the man that she damaged his posthumous reputation far more than any critic. Her antisemitism and alcoholism have not made her a particularly sympathetic figure, either. To others, she was the innocent victim of Mahler’s misogyny, a woman denied the opportunity to exist on her own terms and forced instead to be “wife and mother” to the great man, to serve the cause of his genius. Neither of these extremes is credible.

“Horowitz’s Alma is the first incarnation of her this author has encountered that actually seems like a real person. And, fittingly for a book entitled The Marriage, the novel is as much, if not more, hers as her husband’s. There are so many questions about Alma and her marriage to Mahler, and most of them begin with “Why?” This was the first book in which I felt like I was getting believable answers.”

Lower down, Woods writes of my portrayal of Mahler’s crucial New York predecessor, the conductor Anton Seidl, that his “shadow looms over the tragic events Horowitz captures so poignantly. As such, he emerges as perhaps the figure one most looks forwards to learning more about.” A protégé of Richard Wagner, in effect Wagner’s surrogate son, Seidl is in fact the central character of my next book – another historical fiction that’s a prequel to The Marriage: The Disciple: A Tale of New York in the Gilded Age.

You can read the rest of Kenneth Woods’ review here.

Related news: a handsome German edition of The Marriage has just been published by Wolke Verlag (the ingenious cover sits atop this blog). A Korean version is forthcoming. I will offer a talk on Mahler and Schubert (“Taverns in Paradise”) at the Colorado Mahlerfest this May 18. And Mahlerei – my bass trombone concertino adapting the Scherzo of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony for David Taylor – will receive a Mahlerfest performance three days ahead of that.

March 19, 2024

What If Porgy Happens to be White? — Celebrating the Art of Lawrence Tibbett

Lawrence Tibbett as Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra

Lawrence Tibbett as Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra

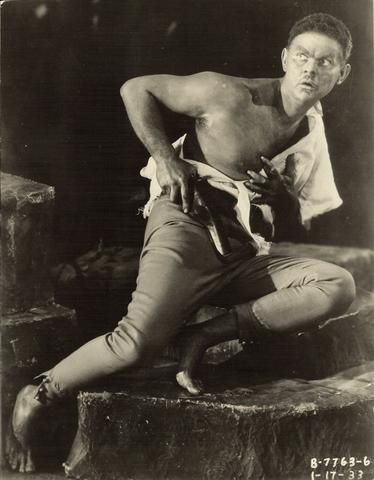

Lawrence Tibbett as Gruenberg’s Emperor Jones

Lawrence Tibbett as Gruenberg’s Emperor JonesGeorge Gershwin chose Lawrence Tibbett to make the first recordings of Porgy’s songs from his opera Porgy and Bess. But Tibbett did not sing them at the Alvin Theatre – Todd Duncan (called by Gershwin “the Black Tibbett”) did. Gershwin wanted a Black Porgy onstage, and Tibbett was white. He was also the supreme American operatic baritone of his (or any other) time.

An extraordinary new 10-CD set issued by Marston Records celebrates the art of Lawrence Tibbett – and so does my most recent “More than Music” feature on NPR. The diversity of his achievement is staggering. And his many recordings in Black dialect are something to think about. In the opinion of John McWhorter, on my NPR show: Given Tibbett’s pre-eminence as an American baritone, given his capacity to inhabit a role and excavate feeling, given his dedication to opera in English, the role of Porgy “was almost written for him.”

McWhorter’s recent New York Times columns include one on “Black English Doesn’t Have to Be Just for Black People.” He takes issue with critics of the comedian Matt Rife, who’s always “dipping into Black English.” McWhorter writes: “Rife is not posing or ridiculing; he’s connecting. Linguists call it accommodation.” The subtlety of McWhorter’s argument resists summary here. But it’s pertinent that Tibbett, too, is “not posing or ridiculing.” Just have a listen to his 1935 version of “Oh, Bess Oh Where’s My Bess?”

McWhorter’s NPR commentary continues: Though the notion that “white people should be allowed to sing like Black people” was “once OK,” today a white baritone singing and acting “Black” would “be hunted to a different planet.” This type of thinking, McWhorter argues, should be “reconsidered” – Tibbett singing Porgy embodies “an American artform evaluable in itself [that] need not be seen as mocking.”

As McWhorter happens to be a professional linguist, I asked him the most obvious question. He answered that, in the context of linguistic practice in 1935, Tibbett “sounds authentic to me. . . . He sounds to me like an educated Black person singing in a sincere ‘dialect idiom,’ . . . adopting a dialect in the same way an opera singer is trained to sing with a proper German accent. . . . If we told a modern skeptical Black critic to listen to one of those [Tibbett] cuts, and we told him it was a Black person, I doubt if one out of one hundred of them would be able to smoke out that they were actually listening to a white man.” Nearly half a century after the premiere of Gershwin’s opera, it’s come time “to just listen to Tibbett as a human being,” opines John McWhorter.

I’ve called my show “’Wanting You’: The Art of Lawrence Tibbett,” referencing an American operetta chestnut, a baritone blast today mainly associated with the likes of Nelson Eddy: hearty and synthetic. Tibbett’s rendering of this Sigmund Romberg number – which he frequently sang on the radio and in recital coast to coast — attains a startling emotional veracity. I invited Thomas Hampson – today’s most famous American baritone – to have a listen. Hampson said: “Quite frankly, this may be some of the most perfect singing I’ve ever heard in my life. It’s just breath-taking. I know the song, I’ve sung it, it’s no walk in the park . . . And the way he negotiates, just technically, this expansive expression, but also with the beauty of tone . . . I mean, my goodness me, what a sound! And to think that this is what was cherished.”

Tibbett craved the role of Porgy. But it was Gershwin’s preference that Porgy be sung onstage by a Black cast – and the Gershwin Estate has maintained this prohibition, at least in the US. Late in his career, in 1953, Tibbett was signed to sing Porgy in Europe. But by then his voice was shot and he had to withdraw. He did, however, sing two roles at the Met made up as an African-American: the Black fiddler Jonny in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf, and – a signature part – Brutus Jones in Louis Gruenberg’s operatic adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones. Fleeing through a jungle, pursued by rebels, Jones sings “Standin’ in the Need of Prayer.” Tibbett left an overwhelming 1934 studio recording of this number. Harry Burleigh, for a time the leading African-American concert baritone, heard Gruenberg’s opera and wrote appreciatively to Tibbett. Tibbett wrote back: “Of all the letters of praise I received, yours means most to me, you who stand so high in the esteem of the Colored race, as well as in the esteem of my own race. You saw the inner significance of the work, and that was lacking in most everyone else’s analysis.”

On Marston’s Tibbett set, and on my radio show, you can also hear Tibbett singing “Scottish” and singing Cockney, singing in French, German, and Italian, inhabiting a bewildering range of personalities and genres. “He had a chameleon-like ability, almost at a genius level, to take on . . . major identity changes,” says Conrad L. Osborne, for more than half a century the pre-eminent English-language authority on opera in performance. On part three of my show, Osborne (who contributes a terrific 60-page booklet to the Marston box) ponders at length what makes Tibbett’s story quintessentially “American.” His training was ad hoc and sui generis; he never studied abroad. Born in Bakersfield, California, he was the son of sheriff killed in a shoot-out when he was seven. His very vocal timbre, Osborne suggests, conveyed an American “call” kindred in spirit to the “lonesome cowboy.” In fact, not only did Tibbett sing cowboy songs; he worked as a ranch hand. This range of experience mattered.

Among the big finds in the Marston set, calibrating the range of Tibbett’s genius, is a 1937 Chesterfield Hour performance of Cole Porter’s “In the Still of the Night.” He’s not just a big voice vacationing from opera. This rendition is as personal as Frank Sinatra’s or Ella Fitzgerald’s. It’s unique to Tibbett – his way with words, his vocal opulence, his huge dynamic range. The song was brand new in 1937, by the way – Tibbett is pitching it.

As memorable, in Marston’s set, is a 1937 Chesterfield Hour performance of Jerome Kern’s “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” Tibbett also frequently sang on the Packard Hour, the Ford Sunday Evening Hour, the Telephone Hour, the General Motors Hour, the Voice of Firestone. That is: on national commercial radio programs hawking cars, cigarettes, and automobile tires, he regaled a mass audience with opera, operetta, and the Great American Songbook.

To my ears, Tibbett is unexcelled in what may be the quintessential Italian lyric baritone aria: “Di provenza” from Verdi’s La traviata. In the Marston set, you can hear him sing it on the Chesterfield Hour. You can also hear him sing it in live performance at the Met in 1935: the cradling legato of his dark baritone, its freedom of phrase and of cadential punctuation, are galvanizing. Singing in German, he’s also the most compelling exponent I know of Wolfram, in Wagner’s Tannhauser. That’s opposite Lauritz Melchior at the Met in 1936. If you happen to be familiar with this opera, check out the third act’s linchpin moment, when Wolfram’s unexpected compassion ignites Tannhauser’s confessional Rome Narrative; Tibbett’s expression of empathy – at 2:36:00 here — is so believable that the incredulity of Tannhauser’s gratitude seems wholly unrehearsed.

I close my radio commentary on the art of Lawrence Tibbett with a “final thought” that “feels so presumptuous that I’m almost reluctant to confide it” —

“We tend to think of human nature as a constant – generation to generation, the same or similar thoughts and feelings. But in recent decades – decades of laptops and cellphones and social media – changes in human predilection are kicking in at exponential speed. When you consider Lawrence Tibbett’s exceptional popularity – on radio, in Hollywood, in opera, in recitals in halls large and small across the United States — re-encountered, he bears witness to another time. Sure, we’ve always expressed, or cloaked, our feelings differently, from one moment, or from one epoch to another. But some of those feelings may actually wither away. Listening to Tibbett sing Cole Porter or Jerome Kern, or Gershwin or Verdi, makes me wonder how much we’ve changed and what those changes may mean.

“I don’t doubt that for many young people today, the opulence of the Tibbett baritone, and its operatic connotations, are insuperable obstacles. I think of how much they’re missing.”

LISTENING GUIDE (tune in here):

00:00: “Oh Bess, Oh Where’s My Bess?”

2:42: “Wanting You”

4:18: Commentary by Thomas Hampson on “Wanting You”

6:40: “In the Still of the Night”

9:33: “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”

15:16: Commentary by John McWhorter on “singing Black”

21:02: George Shirley on Porgy and Bess

24:08: “Standin’ in the Need of Prayer” (from The Emperor Jones)

26:02: George Shirley on The Emperor Jones

30:15: “Di provenza” (from La traviata)

34:40: Jago’s Credo (from Otello)

37:35: Conrad Osborne on what makes Tibbett “American”

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers