Joseph Horowitz's Blog, page 5

September 22, 2024

“The Housatonic at Stockbridge” — Ives’s Four-Minute Masterpiece Extolling the Sublime

This weekend’s “Wall Street Journal” includes a piece of mine reading Charles Ives’s four-minute masterpiece “The Housatonic at Stockbridge.” Composed in the 1910s, it’s both an orchestral work and a song. No other American composition known to me so bears comparison with the famous Nature reveries of Beethoven, Berlioz, Liszt, and Wagner. My essay reads in part:

Ives was a reader, a thinker, a writer philosophic yet unpretentious. Evoking a personal memory [of his courtship, strolling the meadowland along the Housatonic River], he would not have consciously set out to evoke the sublime in Nature. He well knew Beethoven and called him “in this youthful world the best product that human beings can boast of.” Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, the “Pastorale,” famously evokes the sublime in Nature in both its guises: the crashing thunder and lightning of the fourth movement “storm,” the sun-kissed vales of the finale’s “thanksgiving.” Later composers — Romantics like Berlioz in his Invocation to Nature from “The Damnation of Faust,” or Liszt in “Les préludes,” or Wagner in his Good Friday Spell from “Parsifal”– magnificently embellish this trope of existential Nature amplifying the human experience. . . .

Beginning with an unprepossessing New England stream, culminating with an oceanic surge, “The Housatonic at Stockbridge” supremely embodies the sublime in Nature in all of four minutes. In American visual art, the gigantic Hudson River School canvases of Frederic Edwin Church furnish its closest equivalent. But Ives is the more capacious, more protean painter. . . . The result is a shifting, incorporeal landscape, grounded in the bass, trembling and oscillating atop. . . . Then – an ecstatic moment . . . — the quivering ether feeds upon itself in a rush toward the majestic Atlantic; or toward the heavens and hereafter. . . .

Though some writers have compared this sonic feat with the iridescent water-music of Debussy and Ravel, Ives eschews Gallic clarity. In “The Housatonic at Stockbridge,” the culminating oceanic surge is suddenly and densely cacophonous. A frame of reference surer than Debussy’s “La Mer” is the painter Ives seems most to have admired: J. M. W. Turner, whose visionary canvases translate a lifetime of close observation into impressions sublimely imprecise and suggestive. . . .

The mastery of this exercise in concise musical portraiture confutes enduring stereotypes of Ives as a hit-and-miss experimentalist. . . .

Charles Ives deserves to sit atop the American cultural pantheon alongside such kindred self-made originals as Herman Melville and Walt Whitman. Under-performed, insufficiently understood, he retains a double taint – that he was a gifted amateur; that his music is “difficult.” Might the present Ives Sesquicentenary Year make a difference? If so, “The Houstatonic at Stockbridge” would be an ideal point of departure.

The upcoming Ives Sesquicentenary festival at Indiana University includes the premiere of a visual rendering, by Peter Bogdanoff, of “The Housatonic at Stockbridge” and its two neighboring movements in “Three Places in New England.”

September 15, 2024

Charles Ives and National Understanding

Charles Ives, 150 years old, is immensely important right now. Why is that? What’s changed?

For the Ives Bicentenary festivals currently sponsored by the NEH Music Unwound consortium, The American Scholar has published an extraordinary online Program Companion. In addition to my essay on Ives and Mahler, it features contributions by a leading American art historian, a leading American Civil War historian, a prominent magazine editor, and the eminence gris among contemporary Ives scholars. These fresh perspectives not only transport Ives far beyond the modernist decades in which he was once incongruously confined; they propose his music as a vital source of national understanding and hope for the future.

Tim Barringer is Yale art historian who really knows music. His studies of Frederic Church, the Hudson River School, and the “American Sublime” have transformed our understanding of nineteenth century American visual art. Tackling Ives for the first time, Tim has come up with a array of landmark insights. “By examining the key American visual media of Ives’s formative years,” he writes, “we might begin to identify suggestive parallels with his idiosyncratic, vernacular creative practice.” Ives’ “deep sense of local belonging” was “increasingly unusual in a country scarred by Indigenous dispossession and political schism, one in the throes of rapid economic and social change.” His music “revisited the scenes of his youth as if searching the pages of a Victorian album, whose sepia photographic prints and stiff . . . portraits could offer a shockingly direct link with lost times and people, with the faces of the dead. Indeed, the very lifeblood of Ives’s works is a vividly immediate affect that we might think of as photographic.”

Tim cites an 1892 photograph of the Ives house (reproduced above) and comments: “The photograph marked a radical divergence from earlier forms of popular representation seen on the walls of Victorian American – like this 1869 Currier & Lives lithographic print:

[image error]“Images of this kind hover in Ives’s pictorial imagination in the way that Stephen Foster’s songs are ever-present in his musical vocabulary as fondly remembered half-truths of an earlier era. . . But unlike the print’s sugary idyll, the photograph of the homestead at Danbury (much like Ives’s later scores) incorporates a multitude of incidental, miscellaneous, quotidian details. The lens registered the undulations of worn brick pavement and the soil in the road. . . . the uncanny smack of truthfulness that also marks out Ives’s compositions.”

And Barringer explores what drew Ives to the paintings of J. M. W. Turner – paintings “though apparently unfinished, inchoate and hazy” were “rooted in a lifetime of close observation.”

Allen Guelzo, again, is a historian who happens to know music – like Barringer, a rarity. His essay “Battle Hymns” stresses the continued ubiquity of the Civil War in American memory during Ives’s formative Connecticut years. “Overall, Connecticut sent some 55,000 men into the Union ranks . . . almost a quarter of its white male population.” In the years following, “Connecticut veterans organized Grand Army of the Republic posts with no color line, ‘as colored and white are united.’” For Ives the Civil War became “a shining moment of moral truth” – and “the compositions he wrote to remember it are all lavish demonstrations of a determination to use the American past to understand the present.” Specifically, Ives read the war as “the Won Cause”:

“The Civil War was for Ives a living cause, the cause of emancipation. This at a time when American writers were either glamorizing the Confederacy and Jim Crow (from Augusta Jane Evans to Thomas Dixon), politely accommodating Southern sensibilities (the American Winston Churchill in The Crisis), or feeling sorrowful for the price northerners had paid (in William Dean Howells’s The Rise of Silas Lapham) and pretending that the Civil War had been about something other than slavery. In Ives’s use of Civil War songs and marching music, the war served . . . as a symbol of certain eternal verities—about freedom, about race, about the American experience itself. . . . His uses of Civil War music are not meant to entertain or impress, but to draw the listener into the ideals of the conflict itself, the world of Danbury in the full bloom of abolitionist energy, a world that, through his music, he could ensure would never be lost.”

Sudip Bose, the editor of The American Scholar, has undertaken this extraordinary initiative, publishing the Ives Sesquicentenary Program Companion in recognition both of Ives’s importance and of his neglect. Sudip’s essay “A Boy’s Fourth: Listening to Ives in an Age of Political Division” ponders his own experience of Ives’s The Fourth of July. He writes: “In the past several years, with our nation divided, with whispers of civil conflict growing louder and more insistent, with a general anxiety that seems never to relent, I have been hearing in The Fourth of July something far more harrowing, menacing even, than I ever have before. That great cacophonous cloud at the center of the movement seems less like an outpouring of joy than a vision of a nightmare, all those quotations of Americana suddenly sounding like snarling, angry taunts, each fragment crying out to be heard above the others, brash and brutal and bullying. I can’t help imagining this terrifying chaos as an apt metaphor for today’s America, one in which the distorted lines of ‘Columbia’ or the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’ suggest not nostalgia but something far more sinister. Even the work’s final two measures—which once seemed to me like America’s answer to the Mahlerian ewig, a statement on earth everlasting and our place on it— have been transformed in my ears. Those phrases in the strings, hesitant, unresolved, enigmatic, conjuring up a last trail of dying light in the evening sky—they seem to ask an unsettling, unanswerable question: Where do we go from here?”

Finally, J. Peter Burkholder, the most indispensable of present-day Ives scholars, contributes “The Power of the Common Soul.” Ives, Peter writes, shows us “how to listen to every voice and see the good in everyone.” A core message “is his celebration of the music and music-making of common people . . . He upends the [traditional] hierarchy of taste. . . . Hope is one of the great themes of Ives’s music: a celebration of the past, not as a place to return to, or to feel nostalgia for, but as inspiration for the future . . . Music has always been a kind of social glue . . . When Ives incorporates into a composition a hymn tune . . . , it comes with some of that ‘social glue’ attached.”

Peter’s essay closes: “In his words for the song ‘Down East’ (1919), a rumination on ‘songs from mother’s heart’ that culminates in ‘Nearer, My God, to Thee,’ he says it plainly: ‘With those strains a stronger hope comes nearer to me.’ We need that hope today.”

September 10, 2024

Ives and Schoenberg Turn 150 — and the Road Not Taken

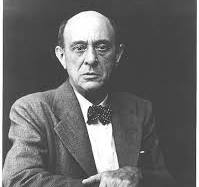

Charles Ives and Arnold Schoenberg, both of whom turn 150 years old this year, are the most important composers of their generation produced by Austro/Germany and the US.

Though Ives was said by some to “know his Schoenberg,” he plausibly denied it. Schoenberg, however, paid sufficient attention to Ives to have written a magnificent encomium: “There is a great man living in this country – a composer. He has solved the problem of how to preserve one’s self and to learn. He responds to negligence by contempt. He is not forced to accept praise of blame. His name is Ives.”

Ives shared with Schoenberg a condition of neglect. He did not share the 12-tone method of composition which Schoenberg anticipated would insure a robust musical future. But Schoenberg admired him anyway – at least for his pride and self-assurance.

Both composers responded to an acute twentieth century challenge with a radical innovation. For Schoenberg, the challenge was spent tradition: the seeming exhaustion of tonal harmony, and a trajectory that anticipated its extirpation. For Ives, the challenge was the absence of tradition: he lacked New World forebears of sufficient consequence to fashion a distinctive American idiom. He invented a strategy deploying American memory shards complexly intermingling with one another and with the Germanic template.

Schoenberg’s innovation – composition with 12 tones – proved a wrong move, but fatally popular. Ives’s innovation was a right move, but fatefully ignored.

I posed an obvious “what if” in my book Dvorak’s Prophecy:

“It is believed that during his New York Philharmonic tenure Gustav Mahler encountered Ives’s Third Symphony in score, took an interest, and might have premiered it with the Philharmonic had he not died in 1911 at the age of 50. Imagine that the score Mahler found was instead Ives’s Second and that he led the premiere performances at Carnegie Hall sometime before the Great War. The discovery of Ives’ songs and Concord Sonata would have been accelerated. American classical music would have acquired a past linking to the vernacular, and to writers and painters of consequence. No interwar commentator – not even Virgil Thomson – could have claimed that all pre-1910 American composers were faceless European clones. The spasmodic odyssey of American classical music could have acquired a pertinent ongoing shape.”

Instead of Ives, it was Aaron Copland who created an American style: sleek, streamlined, Francophile – and not nearly as protean, not nearly as resonant. It is Ives, not the interwar modernists, who connects to the American past, to the Civil War, to the Transcendentalists, to the quintessentially American self-made “unfinished” genius: Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, William Faulkner.

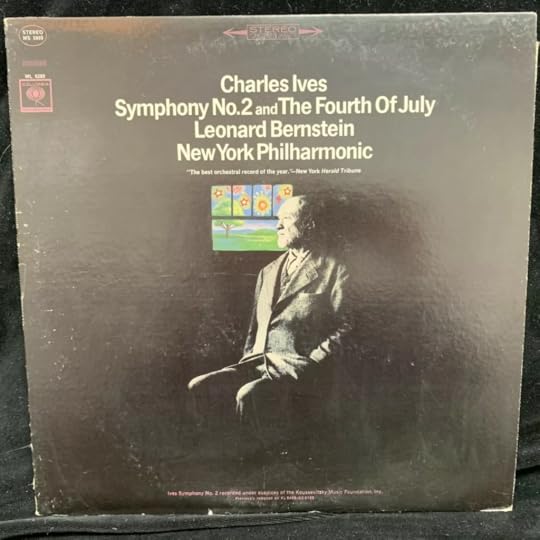

A few weeks ago, scripting my NPR show on Leonard Bernstein, I revisited William Schuman’s American Festival Overture (1939), which Bernstein programed alongside Ives’s Second on his first subscription concert as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Re-encountered today, it’s already a relic, almost a caricature of the wrong road taken.

To read a blog about the one Schoenberg 12-tone piece I still adore, click here.

September 9, 2024

Mahler, Ives, and Today’s Cultural Memory Crisis

In celebration of the Charles Ives Sesquicentenary, I’ve written a long piece on Ives and Gustav Mahler for The American Scholar. The topic is not new: these composers quite obviously have in common a radical propensity to juxtapose the quotidian with the sublime – parade bands and tuneful ditties with the most rarefied metaphysical strivings. But my perspective is, I think, new – and pertinent to the fraught times in which we live.

The American experience is today ever more crippled by a condition of pastlessness. More than any previous composers, Ives and Mahler are obsessed with the act of memory. Mahler’s memories typically stem from his childhood years in Iglau, Ives’s from his Danbury childhood. What is more: Ives virtually curates the American past — the Revolutionary and Civil Wars; the Transcendentalists. No less than Mark Twain, no less than Herman Melville, he is an American icon — and yet remains mistrusted and misunderstood. That at the same time he is for many the supreme American creative genius among concert composers must say something about America and Ives both: as ever, we’re not sure who we are.

Not so long ago, Ives was misclassified as a prophetic modernist. An obsession with “who got there first?” pigeonholed him as an intriguing historical oddity rather than an expressive genius. It placed him firmly in play, but proved essentially patronizing. Once the modernist criterion of originality dissipated, however, it became possible to resituate Ives as a complex product of a dynamic period of American growth itself undergoing revision.

Hence the sesquicentenary opportunity at hand, celebrating the 150th birthday of this most volatile cultural bellwether. With Ives ensconced in a pervasive fin-de-siecle moment, we can at last thrust him onto the international stage he deserves and inquire: what about Charles Ives resonates with musical developments abroad – not as a possible harbinger of Arnold Schoenberg or Bela Bartok, but as a precise contemporary of the European composer he most striking resembles?

The creative act, however understood, is therapeutic: a conversation with the self. For Mahler, for Ives, shards of memory proved an exigent mooring ingredient. Their occurrence is made to seem involuntary, unpremeditated, unwilled. In Mahler, a signature memory swath is public rituals of mourning written into the dirges of his symphonies. The funeral mode may intrude at any moment — as when the clarion fortissimo opening of the sanguine Third instantly dissipates to the wailing winds and searing trumps cries of a pianissimo processional. In Ives, a distinctive memory swath is of sounds heard over water, which may (as in the song “Remembrance”) evoke his father, or (as in the song “The Housatonic at Stockbridge”) his courtship. In Ives’ “The St. Gaudens on Boston Commons,” the memory of Civil War songs is spectral: a haunting of the present.

My American Scholar essay concludes: If Nietzsche, processing decades of bewildering flux, diagnosed a condition of “weightlessness,” today’s affliction is pastlessness. Our world of social media and mounting, ever multiplying gadgetry swims in bits and pieces, in disconnected dots, in superficia and ephemera. Processing the lapse in cultural memory evident all around us, we should fear losing touch with the arts – with civilization – as a renewable reservoir.

Leonard Bernstein’s recovery of Ives’ Second Symphony in the 1950s — widely reported and acclaimed – should have secured Ives a firm foothold in the American symphonic repertoire. Bernstein broadcast and recorded Ives. He espoused Ives on national television. He took Ives abroad. He laid the groundwork – but it never happened. Incredibly – tellingly — the present Ives Sesquicentenary is mainly being celebrated abroad. In the United States, it will be commemorated most ambitiously not by any orchestra or music director, but by the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University/Bloomington, which in October hosts nine days of cross-disciplinary exploration supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Who else — what institutions of education and performance – will remember Charles Ives in years to come? It is not an idle question. It is now 78 years since Lou Harrison unforgettably wrote:

“I suspect that the works of Ives are a great city, with public and private places for all, and myriad sights in all directions . . . . In the not-too-distant future it may be that we will enter this city and find each in his own way his proper home address, letters from the neighbors, and indeed all of a life, for who else has built a place big enough for us, or seen to it that all were equally and just represented? Such is the work of Ives And if we here, in the United States, are still really homeless of the mind, it is not because men have not spent their hearts and spirit building that home . . . but simply because we refuse to move in.”

A side topic in my American Scholar essay: No other American composer connects more explicitly with the ragged New World arts species epitomized by Herman Melville. Both Melville and Ives eschewed finishing school in Europe – the treasures and literary traditions of Italy and France; the conservatories of Vienna and Berlin. Concomitantly, both embraced a democratic ethos. Melville’s schooling was obtained on the South Seas among sailors of every race and stripe. Ives insisted that his second vocation – selling life insurance – enhanced his musical vocation; “Get into the lives of the people!” he thundered. Melville’s masterpieces are proudly unkempt. So it is with Ives: a frontier trait. If Moby-Dick and Benito Cereno are peak American achievements in large and smaller forms, so are Ives’ fifty-minute Concord Piano Sonata and four-minute “Housatonic at Stockbridge.” And an early Ives composition, his Second Symphony, parallels Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: fearlessly mining American vernacular speech and song, they are kindred landmarks in appropriating the European novel and symphony. In short, the pantheon of the self-created, “unfinished” American genius – the high canon of Emerson, Melville, and Twain, also of Walt Whitman, George Gershwin, and William Faulkner – is Ives’ rightful home. And yet he remains less known, less widely appreciated.

The forthcoming Ives festival at Indiana University – possibly the most ambitious Ives celebration ever mounted — devotes an afternoon to “Ives and American Literature.” Other topics in play include Ives the man, Ives and the American band, Ives in performance, Ives and Nature, Ives and the Gilded Age, Ives and hymnody, and Ives and the Civil War. All the concerts and talks will be free of charge, and they’ll all be live-streamed. For further information, click here.

The newest online edition ofThe American Scholar (whose editor, Sudip Bose, deserves an Ives Medal) includes my Ives/Mahler piece alongside four additional Ives Sesquicentenary essays — by Peter Burkholder, Allen Guelzo, Tim Barringer, and Sudip himself — that comprise a 50-page Ives Sesquicentenary Program Companion. I’ll shortly be posting a blog pondering the significance of these fresh musical and extra-musical perspectives.

August 30, 2024

The Bernstein Story Not Told in “Maestro” — Take Four: What Happened to Charles Ives?

In 1951, Leonard Bernstein, age 32, led the New York Philharmonic in the belated world premiere of Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 2 – music composed half a century earlier. The performance was nationally broadcast and widely noticed. Seven years after that, Bernstein began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s music director with Ives’ Second Symphony. In all, he performed Ives’ Second twenty times during his Philharmonic decade. He also recorded it. He devoted a nationally televised Young People’s Concert to Ives. For the Ives Centenary, in 1974, he led Ives’ Second on July 4 in Danbury, Connecticut – Ives’ hometown. In short: he rescued from oblivion a great American symphony and followed that up with a sustained act of advocacy.

I remember the Ives Centenary. It included a major conference which resulted in an important book. The notion that Ives was the supreme creative genius in the history of American classical music gained a lot of traction. The Ives cause had in fact steadily mounted since the discovery of his Concord Sonata – the summit of the American keyboard literature – in 1939. It was widely assumed that the Ives crescendo would continue. But it didn’t. So far as I can tell, this year’s Ives Sesquicentenary is being ignored by American orchestras. It is in fact far more noticed abroad. And, what’s more – what’s worse – none of this is very surprising.

I subtitled my 2005 tome Classical Music in America “A History of Its Rise and Fall.” At a noisy session of the American Symphony Orchestra League conference that year, a longtime orchestra CEO ridiculed my premise that classical music in the US was rapidly fading to the margins; I did not cite a single statistic, he smugly observed. Seventeen years previous to that, I published a book even more reviled: Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American Culture-God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music.

The basic premise of both books was that classical music in the US was and is incurably Eurocentric. I had attempted to figure out how that happened. In the process, I discovered that things were very different before World War I. It was once widely assumed that the US could acquire a symphonic and operatic canon of its own, that American orchestras and opera companies would eventually mainly give American works. As of 1900, no one of consequence imagined that the umbilical cord would remain intact.

The core topic here is the popularization of the arts during the interwar decades. A “new audience,” populated by the “new middle classes,” was born. It represented both an opportunity and a challenge. Both were botched. A key factor was a commercial strategy pursued via radio and recordings by NBC and RCA. They marketed what they could best sell: masterworks by dead Europeans. They extolled (I am not making this up) passive consumption by amateurs – let the professionals do the work. Virgil Thomson dubbed it all the “music appreciation racket.” I use the term “the culture of performance,” sidelining the composer. (In my cultural Cold War book The Propaganda of Freedom, I glance at the Soviet Union and discover an interwar popularization strategy emphasizing making music in homes and factories, and privileging native repertoire new and old.)

Was it inevitable? I mull the role of leadership. David Sarnoff, masterminding NBC and RCA, was a visionary with a parochial musical vision. Arthur Judson, the Robert Moses of American classical music, was a powerbroker, a music-businessman. Running Columbia Artists Management and the New York Philharmonic, he decreed (explicitly): the audience sets taste. Concurrently, Sarnoff and other broadcasters defeated proposals for an “American BBC” (which would have made a difference).

If you’re looking for leaders in American classical music, look before World War I. They were omnipresent. The two most formidable were Theodore Thomas, whose itinerant Thomas Orchestra toured the hinterlands, and Henry Higginson, who invented, owned, and operated the Boston Symphony. They set taste. And so did Anton Seidl and Oscar Hammerstein in New York, and Laura Langford in Brooklyn. In later decades, Serge Koussevitzky, Leopold Stokowski, and Dmitri Mitropoulos, in Boston, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis, were exceptions proving the rule outside the Judson orbit. Then Judson hired Mitropoulos to lead the New York Philharmonic, whose pedigree was sinking. My favorite Judson story: when Mitropoulos conducted the Philharmonic in the American premiere of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, Judson insisted that it be replaced with the Gershwin Piano Concerto for the Sunday broadcast – Gershwin, Judson maintained, would be more suitable radio fare and also sell more tickets at home. In response, Mitropoulos wrote Judson “to beg you, almost on my knees” to change his mind. “It would be a crime not to give this New World [broadcast] premiere of this great and exciting symphony . . . It would be a great event from which we have nothing to fear and from which to expect no less than the highest gratitude of all the musical artistic world in the United States.” He added that he awaited Judson’s response “with anxiety.” Judson said no.

And this is why Leonard Bernstein mattered and matters still. Of the dozens of blogs I’ve posted in recent years, the most read, by a wide margin, deal with institutional leadership – at the San Francisco Symphony, the Boston Symphony, and the Metropolitan Opera. And they cite a couple of inspired institutional leaders I knew: Harvey Lichtenstein at BAM and Speight Jenkins at the Seattle Opera. Imagine, if you can, a leader of Bernstein’s stature today at the helm of an American orchestra or opera company.

As for Charles Ives: the NEH-funded “Music Unwound” initiative I’ve directed for a dozen years mounts cross-disciplinary festivals dedicated to signature topics in American music. The most necessary of those, I would say, is “Charles Ives’ America.” The humanities-infused strategy is to contextualize the Second Symphony, the Concord Sonata, and Ives’s songs and chamber works. We challenge the misimpression that Ives is esoteric.

“Ives’s America” has been produced by the Buffalo Philharmonic, the South Dakota Symphony, and the Brevard Music Festival, with three more coming up: the Chicago Sinfonietta in collaboration with Illinois State University, Bard’s The Orchestra Now (including a Carnegie Hall performance), and – very possibly the biggest Ives festival ever mounted – Indiana University at Bloomington. I pitched NEH-subsidized “Music Unwound” Ives festivals to two major orchestras and got nowhere. An Artistic Administrator asked rhetorically: “How would I sell it?” This is not a question I heard from JoAnn Falletta in Buffalo, Delta David Gier in Sioux Falls, Jason Posnock in Brevard, Blake Anthony Johnson in Chicago, or Leon Botstein at Bard. (At Bloomington, the concerts will be free.)

Back in the day, when I undertook projects for the New York Philharmonic (where “Music Unwound” was actually born, thanks to Matias Tarnopolsky), there was a photograph of Leonard Bernstein directly over the elevator exiting the administrative offices. Perhaps it’s still there. I never passed under it – not once – without experiencing piercing sadness and incredulity that the Philharmonic was no longer his.

For a schedule of upcoming NEH-supported Ives Sesquicentenary festivals, click here.

To read previous blogs in this Bernstein series, click here, here, and here.

To listen to an NPR “More than Music” exploration of “The Bernstein Odyssey,” click here.

August 27, 2024

The Bernstein Story Not Told in “Maestro” — Take Three: Bernstein, Furtwängler, and Saying What You Think

According to a well-worn anecdote, Johannes Brahms was heard to say: “I’ll never write a symphony, you have no idea what it feels like to hear the footsteps of a giant behind one” – the giant being Beethoven. And Brahms was all of 43 years old when he finished his First Symphony, whose finale alludes to Beethoven’s Ninth. If Brahms in fact felt intimidated by his mighty precursors, he was assuredly fortified as well: there would be no Brahms symphonies, as we know them, without the forebears he knew and studied.

In the case of Leonard Bernstein – the topic of a previous blog and NPR feature – the weight of the past was a constant topic. It imposed expectations and Olympian standards. But mainly Bernstein worried that cultural memory was a resource that risked being squandered or diminished over the course of the twentieth century. And I believe Bernstein’s anxiety was all too prophetic.

Scripting my NPR show, I returned to Bernstein’s 1973 Norton Lectures, and differently reacted to his discomfort with the course of music in his time. He was a musician whose purview was always unusually broad. Not only because it embraced a variety of genres, but because – as a diehard pedagogue – his explorations of past achievement fed never-ending questions and concerns about the fate and purpose of the arts. His discomfort with the state of music once seemed to me anachronistic. I would now call it courageous.

Another discovery I made, scanning the web, was a one-hour interview with Bernstein about conductors he had known. He expressed pride that “all these conductors were my friends.” In relation to his contemporaries, he was typically inquisitive and acquisitive. He studied – simultaneously — with Serge Koussevitzky and Fritz Reiner, who had virtually nothing in common as technicians or interpreters. He was also influenced by Dmitri Mitropoulos, who was remote from Koussevitzky and Reiner both. And, in the interview (with Paul Hume), one learns that he valued his personal relationships with Arturo Toscanini, George Szell, and Karl Bohm. Bernstein was famously eclectic – and this is nothing if not an eclectic list.

But the most riveting moment in the interview, by far, is a story about Wilhelm Furtwängler. (Go to 35:00.) In the late forties, Bernstein conducted a Mahler symphony at the Concertgebouw, in Amsterdam. He arrived to discover that, the night before his concert, Furtwängler would lead Brahms’ First with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. It was Bernstein’s first (and only) opportunity to hear Furtwängler in concert – he had to go. But his European manager told him this was out of the question. The hall would be picketed by demonstrators denouncing Furtwängler as a Nazi (which he was not). And Bernstein, being Jewish, would attract attention.

Bernstein managed to enter the hall via backstage and sit in a stage box unobserved. “I’d never seen anything like it, I’d never heard anything like it,” he remembers. “I was in tears. I thought, ‘I’ve got to go back to meet him.’ But I was told – ‘you can’t do that. It would be embarrassing for him; it would be embarrassing for you.’’”

Many years later, Furtwängler’s secretary mailed Bernstein a page from his diary. “It said: ‘Tonight I heard the greatest conductor in the world, and I was prevented from meeting him.’ Furtwängler had done the same thing. He had been in that same stage box for my concert. And he asked to go backstage to meet me. We were not allowed to shake hands with one another on two successive nights because of public opinion.”

(Of my older blogs, the ones dealing with Furtwängler continue to be accessed, the most popular being “Furtwangler in Wartime”.)

Among the responses to my first Bernstein blog, one in particular, from the horn player Christopher Caudill, bears pondering. It reads:

“Western Culture has been demonized by the Social Justice Bolsheviks as irredeemably racist and genocidal. Our contemporary St. Justs and Robespierres do not feel the need to learn about Tradition, because they have identified it as a mere catalogue of injustice and oppression. Young people are being robbed of their own heritage; this fall at UNC Chapel Hill the music history requirement for students has been done away with, after being taught for generations. It’s time for sincere artists to speak up for the integrity of Western Culture without fear; as Heather MacDonald pointed out in her City Journal article (https://www.city-journal.org/article/classical-musics-suicide-pact-part-1) the vast majority of arts leaders and educators have remained shamefully silent in the face of this decay and disintegration. Bernstein would have boldly spoken out, cigarette lit, whiskey in hand. Bless him and his crazy genius, and may his memory inspire American artists to “feel the fear’ and do it anyway.

“Your Bernstein article, and the comments of Thomas Hampson in particular, hit me hard with a feeling that we are losing ground as human beings through the ‘calamitous failure of American cultural memory.’ I spent two years with Michael Tilson Thomas at the New World Symphony, and through him I perceived the tremendous artistic power that Bernstein wielded; a kind of uncompromising sincerity and commitment to the beauty of music. Understanding the incredible musical vitality of post World War II America is impossible without including Lenny — the idea that his legacy might be ignored through basic ignorance is horrible to contemplate.'”

As I have repeatedly observed, Bernstein’s tenacious advocacy of Dmitri Shostakovich, in the midst of Cold War propaganda portraying Shostakovich as a Soviet stooge (not to mention Western cultural propaganda espousing 12-tone orthodoxy), says a lot. We do not much encounter this kind of fearlessness today. Have a look at our political arena. A conductor of my acquaintance adds:

“One sure way to stay unemployed as a conductor is to get known for your political views. “

To read my previous blog on Bernstein and the FBI, click here.

August 25, 2024

The Bernstein Story Not Told in “Maestro” – Take Two

J. Edgar Hoover

When Jamie Bernstein told me about her father’s FBI file – and its disclosure of hate mail and picketers generated by the FBI in 1970, in the wake of the Bernsteins’ Black Panthers fundraiser — I was impressed but unsurprised. A year before, J. Edgar Hoover had called the Black Panther Party “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” The FBI responded with a covert counter-intelligrance program (COINTELPRO) of surveillance and infiltration.

I claim no expertise about the Black Panthers. But I did live through the sixties and seventies, including momentous years in Berkeley and Oakland. Before that, in 1970, I graduated from Swarthmore College, where my last two years were tumultuous. One day a gentleman in his thirties turned up and participated in a meeting at which he ludicrously suggested that our student demonstrations were insufficiently violent. Nobody paid any attention to him or thought twice about it. Some time later a nearby FBI office was raided in Media, Pennsylvania. Those files disclosed FBI agents infiltrating Swarthmore student meetings both on and off campus. We also learned that the campus switchboard operator was an FBI informant.

Someone should write a book about the relationship between the intelligence community and the American arts during the Cold War. At Tanglewood, an informant — another switchboard operator — fingered Aaron Copland with no idea who he was. The same was true of Joe McCarthy, when he interrogated Copland in 1953; his ignorance was risible.

My book on the cultural Cold War, The Propaganda of Freedom, is a study in mutual incomprehension. The White House, the CIA, and the State Department relied upon Nicolas Nabokov as their in-house expert on the state of the arts in Soviet Russia. As General Secretary of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, Nabokov enjoyed access to limitless funding, covertly furnished by the CIA. He also wrote widely about Soviet music. He was a minor composer of consequence, a cosmopolite, a charming and well intentioned raconteur. He was also a man disinherited by the Russian Revolution and traumatized by exile. He could only view the Soviet Union as a cultural and intellectual wasteland. He particularly demonized Dmitri Shostakovich, whom he considered a lesser composer than his friend Vittorio Rieti. And — notwithstanding the achievements of Shostakovich or Tarkovsky or Solzhenitsyn — this became the counter-factual American propaganda line: that absent “freedom,” creativity was inconceivable. Any reasonably informed observer of Soviet music in those years (I even include myself) could have told the CIA that Nabokov’s Orwellian USSR was a fantasy. Soviet Russia was no North Korea.

Relying on Nicolas Nabokov for insight into Soviet culture was kindred to relying on Cuban exiles for advice on the Bay of Pigs invasion. Or thinking that the Bernsteins were a threat to American wellbeing.

August 22, 2024

The Bernstein Story Not Told in “Maestro” – His Prophetic Disenchantment with What America Had Become

Leonard Bernstein’s musical odyssey – in some ways, not unlike the marital odyssey dramatized in the film Maestro – was ignited by ecstatic expectations that proved unsustainable.

He eagerly anticipated a Great American Symphony, a new American species of musical theater, and a New World version of the New York Philharmonic. An iconic American journey, it yielded bitterness and disappointment, relieved by an unanticipated second musical home abroad: in Vienna.

Bernstein’s alienation proved prophetic: he all too well perceived the unravelling of the America in which he had once placed enthralled hopes.

“I don’t think anyone should doubt for a second the weight on Lennie’s soul,” comments Thomas Hampson in my latest “More than Music” installment on NPR: The Bernstein Odyssey. Having sung with Bernstein more than any other baritone, Hampson bears witness that “when Lennie was in Vienna, the city stopped.” And he minces no words about what Bernstein increasingly encountered at home: “I think we are in dangerous times for people seeking enrichment to live. That may sound glorious and grand — but I’m a student of Leonard Bernstein. . . . And I think to understand Lennie’s reaction in the sixties . . . would be terribly illuminating for people today.”

Bernstein’s elder daughter Jamie remembers her father’s response to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, whose White House he visited, then to the deaths of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King. “My parents started to feel really pessimistic about the United States. And then we were in the Nixon Administration, and we had the Vietnam War. . . . My father got very discouraged about the state of the union – and that sense of despair did not leave him for the rest of his life.”

A singular chapter in Bernstein’s American odyssey was a once very famous article by Tom Wolfe in New York Magazine. Coining the withering term “radical chic,” it savagely ridiculed the Bernsteins for hosting a fundraiser for the Black Panthers. Charlotte Curtis, the society editor of the New York Times, chimed in with a caustic piece of her own. Jamie Bernstein remembers:

“And then, after that, there was an editorial! In the New York Times! An editorial, lambasting Leonard Bernstein and his wife for hosting that event. And the subtext was that the Black Panthers were considered by Jewish people to be ‘anti-Zionist.’. . . Friends of my parents and relations of my family were furious at my mother . . . The blowback went on and on. The hate mail started to arrive. The Jewish Defense League was picketing outside our building. . . . And it was only decades later, in the 1980s, that through the Freedom of Information Act my father was able to view his own FBI file, which turned out to be 800 pages long. . . . It was in those pages that we discovered that all that hate mail had been generated by the FBI, and all those JDL protests outside our building were bristling with FBI plants. And this all came sstraight out of J. Edgar Hoover’s playbook – it was his dream come true to pit Jews against Blacks. . . . My mother and father were just sitting ducks.”

Another facet of Bernstein’s despair – which I don’t explore on the NPR show – was the fate of music, both popular and “serious.” He felt it had lost its way. This was the topic of his 1973 Norton Lectures, “The Unanswered Question,” the question being: Whither music in our time? When I first encountered these six talks I was impatient with Bernstein’s discomfort with non-tonal music; having been well indoctrinated in 12-tone compositional practice, my reaction was: Get over it. No longer. Bernstein was, again, prescient. His essential premise, I now realize, was that musical creativity – that any creativity – must not cancel the past, that to start wholly anew is a fool’s errand. He was equally skeptical of Stravinsky’s denial that music can express something other than itself.

It took some nerve, in 1973, to confront Schoenberg and Stravinsky as Bernstein did. He also, in 1966, celebrated the birthday of Dmitri Shostakovich on a nationally televised Young People’s Concert, fearlessly commenting: “In these days of musical experimentation, with new fads chasing each other in and out of the concert halls, a composer like Shostakovich can be easily put down. After all he’s basically a traditional Russian composer, a true son of Tchaikovsky—and no matter how modern he ever gets, he never loses that tradition. So the music is always in some way old-fashioned—or at least what critics and musical intellectuals like to call old-fashioned. But they’re forgetting the most important thing—he’s a genius: a real authentic genius, and there aren’t too many of those around any more.”

Bernstein concluded his Norton lectures with an obligatory blast of optimism – not least because he believed his own compositional magnum opus lay ahead. “There is a general bubbling and rejoicing and brotherliness among composers that would have been unthinkable ten years go. It’s like the beginning of a new period of fresh air and fun.” It never happened. And Bernstein’s own 1983 opera A Quiet Place proved a dark place. The dialectical tension between present and past, long the mainspring for musical creativity, had long gone slack. In Stravinsky and Schoenberg, this conundrum, differently manifest, ran its fatal course. Today’s makeshift music — I am thinking of a variety of temporarily popular operas and concert works — is a further consequence.

To close my NPR program, I asked Thomas Hampson and Jamie Bernstein, and also the conductor JoAnn Falletta: “What is the significance, today, of the Bernstein odyssey?”

“I feel for people of my time, he will always be a hero, there’s no one who will ever replace him,” said Falletta. “For younger people I’m less sure – and I feel badly about that. I mention Leonard Bernstein and I see a kind of blank look from teenagers. And that is such a pain to me, a pain in my heart.”

Jamie Bernstein has created “a dog and pony show” – an hour-long presentation, which she hosts, titled “Leonard Bernstein: Citizen Artist”: “And in this presentation I explain to young musicians why Leonard Bernstein still matters. And that it was because he used his musicmaking in every way he could think of to try to make the world a better place.”

For Hampson, forgetting who Leonard Bernstein was symptomizes a calamitous failure of American cultural memory. I can only agree. Sampling Bernstein’s 1959 televised concert from Moscow, I observe – referencing a story explored in my book The Propaganda of Freedom — that Bernstein’s New York Philharmonic tour to Soviet Russia became a turning point in American foreign policy.

“Some at the State Department were anxious about this initiative. And in fact, Bernstein proved wholly irrepressible, completely unpredictable. He also proved an exemplary cultural ambassador, extolling American and Russian music both. He shook the hand of Dmitri Shostakovich, the leading Soviet composer, who was at the time a target of CIA-sponsored defamation. He befriended invited Boris Pasternack, the eminent Soviet novelist, who was a target of Russian defamation. And, in an inimitable televised Moscow concert, he insisted that, through music, Russians and Americans could discover a common bond.

“In a matter of days, Bernstein superseded a decade of American cultural propaganda, funded by the CIA, demonizing the Soviet Union as a cultural backwater. Beginning with Bernstein, a new policy of cultural exchange with Soviet Russia, applying the arts as an instrument of mutual understanding, became an indispensable diplomatic tool.

“If you think back to what Bernstein achieved in the Soviet Union in 1959, and ask yourself who could do something like that today – really no one comes to mind. We lack national spokespersons in the arts. We lack ‘citizen artists.’ We increasingly live in an arts vacuum.”

Challenged to end the show on a positive note, I add:

“All his life, Leonard Bernstein would ricochet between elation and distress. It’s in his music, it’s in his conducting. It’s in his letters, which document ecstasies of fulfillment in alternation with ‘big, soggy depressions.’ It’s a Mahlerian duality. And here’s a Mahlerian remedy: Bernstein’s signature moment from his signature performance of his signature Mahler symphony — the symphony he led as a 29-year-old Wunderkind with the Boston Symphony, that he led on national television in response to President Kennedy’s assassination, that I heard him lead in April 1987 at Lincoln Center with the New York Philharmonic – a legendary performance of the Resurrection Symphony.

“The moment in question is an apocalyptic fanfare, heralding a pageant of redemption. At Lincoln Center, in 1987, it was unforgettable. And unforgettably slow. So slow as to demand maximum emotional investment – from Bernstein, from the orchestra, from the audience.

“You really had to be there.”

That 1987 Mahler/Bernstein fanfare ensues. It still sounds apocalyptic.

LISTENING GUIDE:

To hear “The Bernstein Odyssey,” click here.

00:00 — JH shamelessly imitates Leonard Bernstein

3:50 — Thomas Hampson sings a Mahler song and recalls learning it with LB

8:30 — JoAnn Falletta remembers LB teaching at Juilliard

14:20 — Hampson sings “Lonely Town” and explains why it’s “very Lenny”

17::00 — Bernstein in Moscow

21:00 — Bernstein attempts to Americanize the New York Philharmonic

23:45 — Hampson on Bernstein in Vienna: “The city stopped.”

27:00 — Hampson sings and discusses Bernstein’s Yiddish wedding song

29:55 — Bernstein and Mahler’s Ninth

36:00 — Jamie Bernstein on her father’s estrangement from the US

38:30 — JoAnn Falletta, Jamie Bernstein, and Thomas Hampson on the significance of Bernstein today

42::00 — To end on a high note: the signature moment from Bernstein’s signature performance of Mahler 2

For more on the Bernstein odyssey, click here.

For a “More than Music” broadcast remembering Bernstein the cultural diplomat, click here.

For an archive of “More than Music” programs, click here.

August 11, 2024

“Mahlerei” — As Inspired by Zero Mostel

For a period of three decades, I have made music with the renegade bass trombonist David Taylor. These sessions began with sight-reading Beethoven cello sonatas in my living room. They accelerated with our mutual discovery that certain Schubert songs – especially Doppelganger — potently inflamed Taylor’s instrument. A few years ago, I threw caution to winds and turned the Scherzo of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony — a whirling waltz/scherzo — into a sui generis concertino for bass trombone and chamber ensemble: Mahlerei.

Mahlerei was premiered at the Kennedy Center and praised in the Washington Post. I subsequently invited Daniel Schnyder to revise the accompanying parts. The resulting final version (the video above) was brilliantly realized at last May’s Colorado Mahlerfest, with a conductor (Kenneth Woods) and instrumentalists steeped in Mahler style.

My initial inspiration was an insane performance in my head of Zero Mostel singing Mahler’s scherzo in Yiddish. What I wound up with, I would say, is more “Jewish” than the original, and also funnier. But it purports to additionally capture the radiance and pathos of its source.

In a nutshell: I have stitched together the various tunes Mahler distributes among his players and fashioned a relentless trombone excursion. Mahler’s movement tracks an unusual trajectory. A bustling perpetual-motion waltz in C minor somehow yields a celestial D major vision. In Mahlerei, the bass trombone is an irritant whose intrusions are magically subdued by D major angels. I have fashioned the solo part accordingly – including a choreographed exit near the end.

In a New York Sun review of Mahler conducting the New York Philharmonic, W. J. Henderson – one of the great names in American musical journalism – memorably wrote: ”We used to think that Beethoven’s scoring was tolerably simple and that most of it was purely harmonic. . . . But we are rapidly learning that it is quite as contrapuntal as Bach’s and that what we foolishly supposed were mere thirds or sixths in chord formations are in reality individual melodic voices which must be brought out by exploring conductors.”

And so it is in Mahler’s scherzo. Fashioning my concertino, I became acutely aware that Mahler foregrounds a concatenation of individual voices – including differentiated first and second violin parts that had never before registered in my ear. Using single strings accentuates this barnyard dimension – especially when realized by instrumentalists and a conductor who understand Mahler’s intent.

David Taylor and I are currently preparing a version of Schubert’s Winterreise. You can sample our Schubert here. And for trombonists or conductors interested in Mahlerei, I possess scores and parts at hand. Have at it.

David and I gratefully acknowledge Ken Woods’ exemplary advocacy, and his Colorado Mahlerfest band:

Caroline Eva Chin and Sophia Ann Szokolay, violins

Lauren Spaulding, viola

Parry Karp, cello

Michael Geib, bass

Hannah Porter Occena, flute

Jordan Pyle, oboe

Gleyton Pinto, clarinet

Sarah Fish, bassoon

Lydia Van Dreel, horn

Jack Barry, Matthew Dupree, Adam Vera, percussion

Brian du Fresne, harmonium

Michael Karcher-Young, piano

August 8, 2024

Mahler, New York, and Cultural Memory

“It is always instructive to read European newspapers on American affairs. It gives us the much needed opportunity to see ourselves as others see us – with their eyes shut. . . Do we not all reek with malodorous lucre? Are we not a nation of tradesmen?”?

Thus W. J. Henderson, in the New York Sun (March 8, 1908), on the arrival of Gustav Mahler in New York to conduct at the Metropolitan Opera. Henderson – for half a century, a great name in music journalism — was commenting on exaggerated Viennese accounts of Mahler’s financial terms of engagement at the Met. He added:

“The coming of the new interpreter of German operas was awaited with interest and received with pleasure, but there was no public excitement. The stock market was not affected.”

Henderson was merely correct. New York critics knew far more about musical Vienna than Vienna – including Mahler himself – knew of musical New York. When Mahler reported “absolute incompetence” at the Met, he did not realize that Heinrich Conried, the impresario who hired him, was a clownish successor to the Met regimes of Anton Seidl and Maurice Grau, during which New York boasted ensembles of German and Italian vocal artists that no European house could match. And when Mahler called his New York Philharmonic “a real American orchestra – talented and phlegmatic,” he had no idea what he was talking about. The premiere American orchestra was the Boston Symphony, whose conductors had already included Arthur Nikisch. Mahler’s Philharmonic was a shaky aggregation, a pathetic sequel to the concert orchestra Seidl had led.

My novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (also published in German as Die Mahlers in New York) attempts to set the record straight. The most recent (full-page) German review, in the Frankfurter Rundschau, calls it “an important addition to the European Mahler literature. In contrast to Mahler, Joseph Horowitz paints an extremely positive picture of the American musical scene.”

In fact, I would not be at all surprised if my revisionist take on Mahler in America more impacts abroad, where cultural history doubtless retains some degree of vigor. In the US, the institutional history of classical music in America has never excited much interest among scholars. Even our orchestras and opera companies – including the Met, the New York Philharmonic, and the Boston Symphony – show little awareness of their own past achievements.

I am reminded that the current Sesquicentenary of Charles Ives is, at this moment, more celebrated in Europe than in the US. Fifty years ago, when Ives turned 100, Leonard Bernstein and Michael Tilson Thomas were prominent celebrants, and a major Ives Centenary conference was mounted by H. Wiley Hitchcock and Vivian Perlis. Nothing like that is transpiring in 2024 – excepting four Ives festivals initiated via the NEH Music Unwound consortium which I am fortunate to direct.

My next NPR “More than Music” feature, scheduled for August 22, will exlore the musical odyssey (rather than the marital travails) of Leonard Bernstein. Even Bernstein is little remembered; young American musicians don’t know his name. And Bernstein himself was increasingly alienated by what had become of the America in which he had once placed enthralled hopes. The baritone Thomas Hampson, who sang with Bernstein as much as anyone did, comments on my upcoming broadcast:

“I think we [in the US] are in this phase, we are in this time, when things of worth and value that we treasure are easily forgotten, and not learned from. There seems to be this maniacal preoccupation with forward and future, and in the business world steady growth and steady profit. And you kind of have to wonder where the common good sits, and where the collective good sits. And the arts – they’re about the pursuit of happiness in our beautiful Declaration of Independence, they’re about the contented life, about the realization of being human. I think we are in dangerous times for people seeking enrichment to live. That may sound glorious and grand — but I’m a student of Leonard Bernstein. I don’t think anyone should doubt for a second the weight on Lennie’s soul. And I think to understand Lennie’s reaction in the sixties to all of that would be terribly illuminating for people today.”

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers