Ronald H. Clark's Blog, page 9

February 8, 2023

VISUAL LITIGATION AND TODAY’S TECHNOLOGY-- REMOTE LEARNING

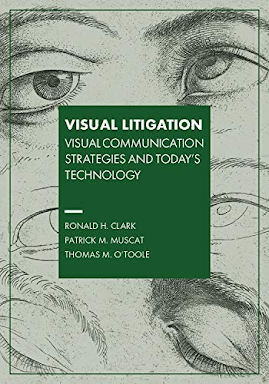

I teach Visual Litigation and Today’s Technology at Seattle University Law School. This is a remote-learning course. I teach one course that is scheduled for the summer semester and another that is a short course (four-days long) scheduled during the intersession break between fall and spring semester.

The courses are perfectly suited for remote learning because students can not only listen to presentations by veteran trial lawyers and engage in class discussions but also actively perform with software and hardware.

The subject matter is ideal for an online course, where students can receive guidance in leveraging litigation software, such as Sanction, TrialPad, and SmartDraw. Also, students can be involved role-play assignments for both a criminal and a civil case using downloadable case files via the book’s website.

Here are some of the students’ activities:

• Designing a crime scene diagram and a timeline utilizing the software SmartDraw;• Creating opening statement and closing argument PowerPoints in civil and criminal cases; • Developing a mediation slideshow;• Working with nonlinear software, such as Sanction; and• Touring professional technician and designer sites and discussing the pros and cons of the software and technical support that is offered.

The text for the course is Visual Litigation: Visual Communication Strategies and Today’s Technology, published by Full Court Press, which is the publishing arm of Fastcase. As you can tell from the title, the book focuses on visual presentations in the pretrial venue and in trial and technology.

My co-authors of the book are Thomas O’Toole, President of Sound Jury Consulting, and Patrick M. Muscat, former Assistant Prosecuting Attorney, Deputy Chief/Special Prosecution Divisions, Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office (Detroit, MI) and currently on the faculty for Vera Causa Group.

Should you or someone you know be interested in setting up a course similar to the one described above, please contact me (206-930-6601 or clarkrh@comcast.net) because I have a Canvas site that you could modify to use for your course.

January 31, 2023

Palsgraf and Improving Your Legal Writing

This is another article about a book I edited, titled The Appellate Prosecutor: A Practical and Inspirational Guide to Appellate Advocacy. The prior blog article was on the 3 Cardinal Rules of a Persuasive Appellate Brief. The Honorable Paul Turner wrote a chapter in the book, and at the time the book was published was Presiding Justice of the California Court of Appeals Second Appellate District of Los Angeles, California, contributed a chapter. Judge Turner’s chapter focuses on the art of writing, specifically on crafting the short declarative sentence, which he referred to as “The Key to Good Legal Writing”.

Here is an excerpt from Judge Turner’s chapter:

The most important way to improve your legal writing is to develop the skill of writing the short declarative sentence. Some people do not need to use short declarative sentences. In 1995, the Houston Chronicle reported that Alan Greenspan, the Chair of the Federal Reserve Board, said, “I spend a substantial amount of my time endeavoring to fend off questions and worry terribly that I might end up being too clear.” In 1992, the Wall Street Journal reported that one wag suggested that Alan Greenspan’s tombstone should read, “I am guardedly optimistic about the next world but remain cognizant of the downside risk.”

But as an appellate advocate, your job is to be clear; not to be uncertain like Mr. Greenspan. Your task is to develop the skill of writing the short declarative sentence so that words march promptly in proper order towards a logical conclusion. That statement of your mission warrants repeating. Your task is to develop the skill of writing the short declarative sentence so that words march promptly in proper order towards a logical conclusion.

Here is an example of this important way of communicating, and it is from the famous case of Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad Company 248 N.Y.339, 340–341 (1928). It is the first paragraph of Chief Judge Benjamin Cardozo’s famous opinion. In law school, professors use the Palsgraf opinion to discuss proximate cause and negligence. More importantly, it is the example of great legal writing utilizing the short declarative sentence as a way to communicate. Here, with minor bracketed interruptions, is the first paragraph of Palsgraf:

“Plaintiff was standing on a platform of defendant’s railroad after buying a ticket to go to Rockaway Beach. [Stop reading now. How many words were the in the first sentence? 18. Now keep reading.] A train stopped at the station, bound for another place. Two men ran forward to catch it. [Stop reading again—how many words in this sentence that describes the hurried conduct of two different human beings in relation to a train leaving a station? Seven words—that is all; now start reading again.] One of the men reached the platform of the car without mishap, though the train was already moving. The other man, carrying a package, jumped aboard the car, but seemed unsteady as if about to fall. A guard on the car, who had held the door open, reached forward to help him in, and another guard on the platform pushed him from behind. In this act, the package was dislodged, and fell upon the rails. It was a package of small size, about fifteen inches long, and was covered by a newspaper. In fact it contained fireworks, but there was nothing in its appearance to give notice of its contents. The fireworks when they fell exploded. The shock of the explosion threw down some scales at the other end of the platform many feet away. The scales struck the plaintiff, causing injuries for which she sues.”

The longest sentence in this first paragraph of Palsgraf is 27 words, the one that begins, “A guard on the car...” That sentence consists of a series of short phrases strung together. Look at them: “A guard on the car, [5 words and a comma] who had held the door open, [6 words and a comma] reached forward to help him in, [another 6 words and a comma] and another guard on the platform pushed him from behind” [10 words and a period].

The most important thing about this whole passage is a reader knows exactly, yes, exactly what happened. This accident happened on August 24, 1924, at the East New York Station in Brooklyn and everybody who reads the first paragraph of Palsgraf knows what happened 80 years later. That is communication, that is the power of the written word.

For the remainder of Judge Turner’s chapter and more on effective appellate advocacy, consider acquiring The Appellate Prosecutor: A Practical and Inspirational Guide to Appellate Advocacy. And by the way, it’s not just for prosecutors who are appellate advocates.

January 23, 2023

NEW BOOK: TRIAL ADVOCACY GOES TO THE MOVIES: Go to the Movies for Lessons in Trial Strategies, Techniques and Skills

What do My Cousin Vinny and Atticus Finch have in common? A lot more than you might think. While Atticus Finch’s closing argument in To Kill a Mockingbird continues to inspire viewers to attend law school, the cross-examinations in My Cousin Vinny—while hilariously funny—offers equally compelling examples of excellent lawyering. With the aid of movies, this book Trial Advocacy Goes to the Movies explores advocacy from pretrial preparation through closing argument.

Why go to the movies to learn trial advocacy strategies, techniques, and skills? First, trial work is theater; movies show trial advocates how to effectively deliver a message to an audience. Second, movies illustrate successful advocacy principles and techniques. Third, movies are a visual medium, showing how to impart to a jury the trial lawyer’s message with visuals. Fourth, movie clips can be used to illustrate ethical and legal boundaries that trial lawyers should not cross. Fifth, some movies are based on actual cases and show how to be successful in trial with a real-life examples. Sixth and lastly, movies are entertaining and that helps the viewer learn winning trial techniques.

This volume, like a play and most movies, has three acts. Act 1 focuses on the screen play and how to incorporate the elements of a five-star screenplay into your trial story. Act 2 is devoted to casting, rehearsal—how to prepare the actors in the movie—the witnesses. Act 3 deals with the performances—how to perform like a star at each stage of the trial.

Your role changes as you move from Act to Act. For Act 1—Screen Writer, you are the screen writer and cinematographer. For Act 2—Director, you are the director who casts the parts, rehearses the actors and so on, and you work for the movie studio. And, for Act 3—Actor, you are the principal actor who performs during each phase of the trial.

Because this is an e-book, you can watch movie clips of trial advocacy (yes, My Cousin Vinny is included) – each clip is just one click away.

This book is an outgrowth of a presentation titled by the same name—Advocacy Goes to the Movies”—that I have had the pleasure of delivering at continuing legal education seminars across the country. Yes, the lawyers got CLE credit for attending. The presentation usually lasted a half-day. Advocacy Goes to the Movies was always a lecture that I enjoyed giving and was received with smiles and engagement by the audience. Hope you enjoy it too.

January 18, 2023

3 CARDINAL RULES OF A PERSUASIVE APPELLATE BRIEF

In a book I edited, titled The Appellate Prosecutor: A Practical and Inspirational Guide to Appellate Advocacy, J. Frederic Voros, Jr., who when the book was published was the Chief of the Appeals Division of the Utah Attorney General’s Office, contributed a chapter—“Writing the Brief.” Mr. Voros’s chapter focuses on how to write an appellate brief. Here is a favorite excerpt from his chapter, which is valuable for any advocate whether are a prosecutor, criminal defense counsel or have a civil practice.

An appellate brief should be brief. It should also be clear and accurate. These qualities are not the end; the end is of course to persuade the court. But they are the means, and they are a necessary means. They are the ABC’s of briefing: be accurate, be brief, and be clear. No brief will persuade that violates these cardinal rules.

THE THREE CARDINAL RULES FOR WRITING A PERSUASIVE APPELLATE BRIEF

Firs t C a r d i n a l Ru l e : B e A c c u r a t e

An appellate brief must be scrupulously accurate. When a factual assertion is followed by a citation to a page in the record—and each one should be—that page, fairly read, must support the assertion. Likewise, when a case is cited in support of a legal assertion, the case, fairly read,

must support the assertion. Statements of what a case means or holds must withstand a fair reading of the case. To cheat in citing to the record or to legal authority is both wrong and foolish: wrong because it is an attempt to deceive the court, foolish because any inaccuracy in the brief will be discovered either by opposing counsel or by a law clerk. Neither prospect is a happy one. If opposing counsel discovers the inaccuracy, she has an additional weapon to attack your argument and, inferentially, your credibility.

If a judge’s law clerk discovers the inaccuracy, you may never know it, but the judge will. Most clerks begin life assuming that attorneys are thorough and conscientious, and are deeply impressed with evidence to the contrary. When they find it, they will feel they have found a pearl of great price that must be shared with their judge, or even included in a written opinion. You do not want your professional legacy to include this kind of reference: “In presenting this issue, defendant has not accurately represented the trial court’s decision.”1

Most crucial from the point of view of advocacy, an attorney who fails to be candid with the court will also fail to persuade the court. Of course, inaccuracy may result from sloppy as well as sharp practice. Unfortunately, from the judge’s vantage point, the two are often indistinguishable.

Ensuring accurate citation is not difficult; all that is required is a thorough cite-check. The cite check should at minimum confirm or correct every record cite; confirm or correct every legal cite, including pin cites; and update all cited cases. Ideally, these tasks should be performed by someone other than the brief-writer; we all tend to miss our own lapses.

Second Cardinal Rule: Be Brief

A short brief is a favor to your reader. Judges are required to read a huge volume of written material. Part of this is our fault. Most briefs are written in haste, and, as a consequence, they are far longer than necessary. When we file a bloated brief, we cast upon the judges the burden of doing the final edit mentally as they read, and they like to edit our writing even less than we do. On the other hand, when we edit our briefs before filing them, judges appreciate it. Our editing makes their lives easier. Good editing is good advocacy.

There is truth in the German proverb, “Loquacity and lying are cousins.” Generally, the more straight-forward the argument, the fewer words needed to make it. You need few words to say that the law and the facts are on your side. You need many to explain why a statute or case that seems to doom your argument really does not. Therefore, all else being equal, length and strength are inversely related. Judges know this, and it makes them suspicious of long briefs. For example, the California Supreme Court once stated that they were “inclined to doubt the correctness of the ruling of the court below, on account of the extreme length of the brief of the learned counsel for respondent in its support.”2 “Knowing the abilities of counsel,” the court continued, “and their accurate knowledge of the law, a brief of 85 pages, coming from them in support of a single ruling of the court below, casts great doubt upon such ruling.”3 The court’s pique was thinly veiled: “However, the learned counsel may not have had time to prepare a short brief, and for that reason have cast upon us the unnecessary labor of reading and extracting therefrom the points made. If we overlook any of them, counsel will readily understand the reason.”4

Not only do shorter briefs look more persuasive, they are more

persuasive. Usually, long briefs are long because they waste words. They digress or repeat or argue uncontested matters or make their point circuitously rather than linearly. They are difficult to follow, and their salient points are often lost in a clutter of words.

Therefore, after you finish writing, start cutting. Strike interesting but sidelight arguments. Strike empty fillers such as “Clearly,” “The State asserts that” and “It is apparent that.” In addition to adding needless bulk, these expressions convey tentativeness rather than confidence. Unless dates are critical, such as where defendant asserts a statute of limitations claim, include only one or two. Also, follow Mark Twain’s advice: “When you catch an adjective, kill it.” The same is true of adverbs. Nouns and verbs are strong; make them do the heavy lifting. Scrutinize long footnotes: irrelevancies lurk there. Shorten sentences and paragraphs. Tighten up.

Third Cardinal Rule: Be Clear

Clarity precedes persuasion. A judge who does not understand your argument cannot be persuaded by it. Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, “I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.” We are responsible for wringing simplicity from the complexity of the appellate record. The court is “not a depository into which the parties dump the burden of research and analysis.”5 We must sift through and present the relevant material in logical order. Your brief is sufficiently clear if an intelligent lay person can comprehend it in one reading. Keep it simple.

But how? For starters, put your main point up front. Do not bury it in the middle of a paragraph or in a parenthetical following a case citation. “Judges are not like pigs, hunting for truffles buried in briefs.”6 Do not hide the ball or unravel your argument gradually. You are not writing a suspense novel. A reader who knows your point up front can assimilate what follows, because he has a general framework into which to fit the detail. The opposite is not true: a reader faced with a mass of detail will understand none of it, because it lacks shape. Your readers should never have to wonder why you are telling them something. Transparency, not subtlety, is your goal.

To say that defense lawyers win by obfuscating would be an exaggeration, but it is not much of one to say that appellate prosecutors win by clarifying. In fact, if we cannot win by clarifying, we should not win.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, please consider getting The Appellate Prosecutor.

January 10, 2023

What is Your Trial Theme? To Kill a Mockingbird

A PERSUASIVE STORY for trial has all of the same ELEMENTS of a MOVIE SCRIPT

We are going to the movies for lessons about trial advocacy.

We are exploring how a persuasive story for trial will have the elements of a good movie script. A good movie has a good theme, and the same goes for your trial story.

A good theme is one that sums up what the case is about—This “case is about ____” Ten years after their jury service if asked what the case was about, they will recite your theme. A good theme crystallizes the human values and needs of your trial story. It is a hook the jurors remember

The following are common trial themes:

• Power and control

• Accountability

• A uniform is only as good as the man or woman who wears it

• Innocents don’t conspire

• Trust and betrayal of trust

Themes are essential to storytelling. Movie advertising tag lines can provide excellent jumping off points for coming up with trial themes:

• “With great power comes great responsibility.” (Spiderman)

• “It was the Deltas against the rules… the rules lost!” (Animal House)

• “Somewhere, somehow, someone’s going to pay.” (Commando)

• “The truth is out there.” (The X-Files)

• “There are degrees of truth.” (Basic)

• “He was never in time for his classes… He wasn’t in time for his dinner… Then one day he wasn’t in his time at all.”

(Back to the Future)

• “He’s out to prove he’s got nothing to prove.” (Napoleon Dynamite)

• “The truth can be adjusted.” (Michael Clayton)

• “In the heart of the nation’s capital, in a courthouse of the U.S. government, one man will stop at nothing to keep his honor, and one will stop at nothing to find the truth.” (A Few Good Men)

• “Some people would kill for love.” (Presumed Innocent)

• “Some people will do anything for money.” (The Fortune Cookie)

• “The first scream was for help. The second is for justice.” (The Accused)

To Kill a Mockingbird was published in 1960. the Library Journal named it the best novel of the century. Seldom does the movie match up to the book upon which it is based, – but, in this case, it does. The 25th in the American Film Institute named it the greatest movie of all time and named Atticus Finch the greatest movie hero of the 20th century.

The phrase “to kill a mockingbird serves as a great example of a theme because it encapsulates what the story—the movie is all about.

Watch how the theme is introduced early on in the movie.

December 28, 2022

New Book Launch - Addressing the Jury: Opening Statement and Closing Argument

Just launched a new book Addressing the Jury: Opening Statement and Closing Argument. Addressing the Jury offers an in-depth explanation of how to craft a winning opening statement and summation and how to persuasively deliver them to a jury. The paperback is $9.29 and the ebook is $6.99.

December 20, 2022

Trial Advocacy Goes to the Movies: The Screenplay

This is the first in a series of articles that takes trial advocacy to the movies. These articles, like a play has three acts.

ACT 1. THE SCREENPLAY

How to incorporate the elements of four-star screenplays into your story.

ACT 2. THE REHEARSALS

How to prepare the actors.

ACT 3. THE PERFORMANCES

How to perform like a star at each stage of trial.

Your role changes as we move from Act to Act. For the Screenplay, you are the screen writer and cinematographer. For the Casting and Rehearsal, you become the DIRECTOR. For Act 3 – the Performances, you become the ACTOR.

Here we concentrate on ACT 1. THE SCREENPLAY

How do you incorporate the elements of four-star screenplays into your story. It all starts with the SCRIPT—THE STORY. We call our trial story, the “CASE THEORY” As the trial advocacy guru and author James W. McElhaney says in his book McElhaney’s Trial Notebook: “The theory of the case is a product of the advocate. It is the basic concept around which everything revolves."

The CASE THEORY has TWO COMPONENTS—LEGAL THEORY and FACTUAL THEORY. The legal theory is what’s charged in a criminal case, robbery, murder, whatever crime and what’s alleged in a civil case, negligence, breach of contract. Or from a defense perspective in a criminal case, self-defense or in a civil case, contributory negligence, and so on.

The FACTUAL THEORY has two subparts—the factual theory must be both sufficient and persuasive. Sufficient—every lawyer understands need to prove enough facts to support the legal theory. But, for the actual story to prevail, more is needed. It must b a persuasive story.

A persuasive story for trial has all of the same elements of a good movie script.

ELEMENT NUMBER 1 Above all else, both a good movie script and a good story for trial needs to be a HUMAN STORY.

Now, we are going to watch the prosecution tell a HUMAN STORY in the movie THE STAIRCASE. The movie was directed by Academy Award®-winning French filmmaker Jean-Xavier de Lestrade.

Now, let’s the prosecutor tell the story of the case.

December 14, 2022

How to Conclude Your Closing Argument

When you reach the end of your closing argument, you want a powerful conclusion, and here is how you can accomplish that end. First, you can return to your case theme—“as I told you in opening, this case is about “trust and betrayal of trust”. This symmetry brings power to your closing.

You can wave the flag—bring emotion and evoke a desire to what you are asking. Here is how Vincent Bugliosi concluded his initial closing argument in the Charlie Manson murder case, “Under the law of this state and nation these defendants are entitled to have their day in court. They got that.

“They are also entitled to have a fair trial by an impartial jury. They also got that.

“That is all that they are entitled to!

“Since they committed these seven senseless murders, the People of the state of California are entitled to a guilty verdict.”

Then in his rebuttal closing argument, Bugliosi finished in this fashion:

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” I quietly began, “Sharon Tate . . .Abigail Fulger. . . Voytek Frykowski . . .Jay Sebring . . . Steven Parent . . . Leno LaBianca . . . Rosemary LaBianca. . . are not here with us now in this courtroom, but from their graves they cry out for justice. Justice can only be served by coming back to this courtroom with a verdict of guilty.”

Watch the prosecutor in the murder trial of Michael Peterson that was made into a documentary titled “The Staircase” conclude his closing argument.

December 6, 2022

Bring Your Closing Argument Alive with Visuals

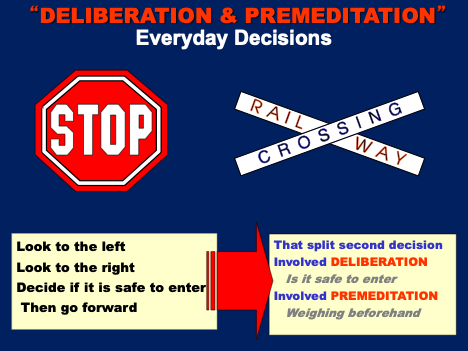

During closing argument, inevitably counsel will want to discuss the law and apply the law to the facts, and this is where visuals can prove to be most valuable. For example, in a first-degree murder case, a prosecutor will want to explain what premeditation and deliberation means, and the prosecutor will read the relevant portion of the court’s instructions to the jury. To explain what the instruction means in terms jurors can understand and relate to, the prosecutor could utilize this visual.

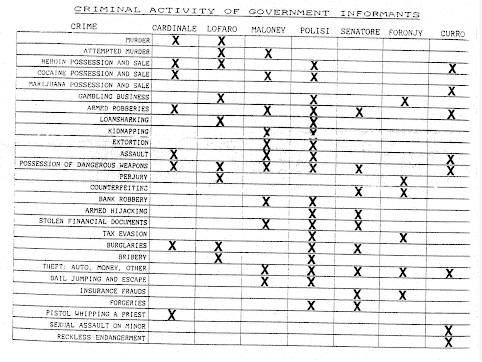

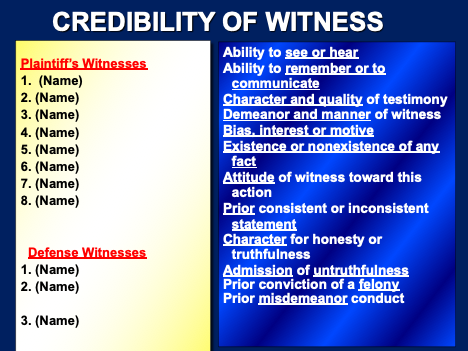

During closing argument, inevitably counsel will want to discuss the law and apply the law to the facts, and this is where visuals can prove to be most valuable. For example, in a first-degree murder case, a prosecutor will want to explain what premeditation and deliberation means, and the prosecutor will read the relevant portion of the court’s instructions to the jury. To explain what the instruction means in terms jurors can understand and relate to, the prosecutor could utilize this visual.The lawyers will discuss the credibility of the witnesses during in closing. If the prosecution’s witnesses have prior convictions, the defense could create and display a visual like this to the jury.

Pistol whipping a priest is pretty bad.

Here is a chart that you could adapt to your case as a visual aid to discuss the credibility of the witnesses. In the left column are the parties witnesses names and on the right the factors stated in the court’s jury instructions that the jury may consider in determining the credibility of the witnesses.

When discussing circumstantial evidence, you will decide what analogy you wish to use. Common ones are the cookie jar with cookies missing and the child with cookie crumbs on the face. Although no one saw the child take the cookie, the circumstantial evidence is clear.

Or you may like the snow analogy. There was no snow on the ground when you went to sleep, but the ground is covered with it when you wake up. You conclude based on the circumstantial evidence that it snowed during the night.

Or, you may like the Robinson Caruso foot prints in the sand one. You choose. A visual will drive the point home that circumstantial evidence can be powerful proof.

Now, watch defense counsel in the documentary Murder on a Sunday Morning use three visuals to argue that the circumstantial evidence proves that the defendant did not commit the murder. Defense counsel used the defendant's appearance, a diagram of the area and a Nautica t-shirt as visual aids.

November 29, 2022

How to Discuss the Law in Closing Argument – The George Zimmerman Trial

Mark O’Mara

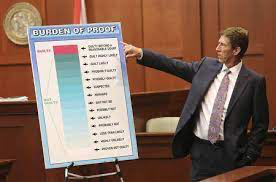

During closing argument, you're going to discuss the law. During instructions are the source of the law for the jury. Inevitably the trial lawyers will discuss the law regarding the burden of proof. The trial of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin provides an excellent example of how counsel can explain the law regarding the burden of proof to the jury.

Watch defense counsel Mark O’Mara discuss the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Despite the best efforts of pattern jury instruction committees, jury instructions may be difficult for jurors to understand and therefore apply the case apply to the case before them. To aid the jurors, counsel can explain the law in understandable terms. Also, trial lawyers can use visuals to explain the law.

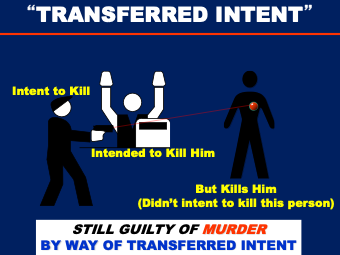

For example, this visual could be used to explain the concept of transferred intent.