Ronald H. Clark's Blog, page 6

October 31, 2023

October 26, 2023

Critical Pretrial and Trial Advocacy Checklists

Checklists are critical to pretrial and trial work. To illustrate the importance of checklists, Dr. Atul Gawande tells the true story of an October 30, 1935 airplane flight competition that the U.S. Army Air Corps held at Wright Air Field in Dayton Ohio to determine which military-long range bomber to purchase. Boeing’s “flying fortress” was the likely winner. But, after the plane reached three hundred feet, it stalled, turned on its one wing and crashed, killing its pilot and another of its five crew members. The pilot had forgotten to release a new locking mechanism on the elevator and rudder controls. The plane was dubbed “too much airplane for one man to fly.”

Nevertheless, a few of the Boeing planes were purchased, and a group of test considered what to do. They decided that the solution was a simple pilot’s checklist. With the checklist in use, pilots flew the B-17 1.8 million miles without an accident. Dr. Gawande in his book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right (p. 34) concludes, “Much of our work today has entered its own B-17 phase. Substantial parts of what software designers, financial managers, firefighters, police officers, lawyers, and most certainly clinicians do are now too complex for them to carry out reliably from memory alone. Multiple fields, in other words, have become too much airplane for one person to fly.”

Dr. Gawande who heads the World Health Organization’s Safe Surgery Saves Lives program recounts that after the World Health Organization introduced the use of checklists for surgeons, research of nearly 4000 patients showed the following: major complications fell 36 percent; deaths fell 45 percent; infections fell almost 50 percent. Rather than the expected 435 patients expected to develop complications, only 277 did. The checklist spared 150 patients from harm and they spared 27 of those 150 from death. (The Checklist Manifesto, p. 154)

Just as checklists are critical for pilots and doctors, they are necessary for trial lawyers as well. At the end of almost every chapter in both Pretrial Advocacy, 6th Edition and Trial Advocacy 5th Edition is a checklist of matters that are essential to effective pretrial and trial advocacy. The following is an example of a checklist that follows the Closing Argument chapter in Trial Advocacy

CLOSING ARGUMENT CHECKLIST

Preparation

Preparation begins soon after entry into the case. Counsel should keep notes of ideas for closing.

Prior to trial, write the closing argument, with final editing during trial. Reduce closing to outline notes.

Rehearse closing argument. Just like opening statement, commit concluding remarks to memory so they will flow smoothly.

Content

Case theories should serve as guides for planning closing.

Regarding the legal theories, jury instructions, among others, serve as the core around which to craft closing argument:

Elements of the claim or defense,

Burden of proof,

Issues in dispute, and

The other side’s case theory.

In arguing the factual theory, counsel should use jury instructions that pertain to crucial facts, as well as a story embodying those facts.

The case theme should be incorporated into the closing.

Closing should meet the other side’s case theory and attacks.

Juror beliefs and expectations that could be detrimental to the case should be identified, met, or distinguished from your case.

Length

Length of closing should be suitable to the complexity of the case, and should not run overly long.

Aristotelian Appeals

Closing should make all three appeals: logical, emotional, and ethical.

Persuasive language should include:

Words with connotations, and

Rhetorical devices, such as postponement, concession, anti¬thesis, metaphors, similes, analogies, and rhetorical questions.

Structure

The closing should begin by seizing the jury’s attention.

The body of the closing should be well organized, emphasizing the strengths of the case before dealing with case weaknesses or the other side’s attack.

The closing should conclude by referring to the theme and reasons for the requested verdict, thus motivating the jury to make the right decision.

Rebuttal should refute the other side’s arguments and finish strong.

Bench Trial

Counsel should:

Be prepared to answer the judge’s questions during closing.

Not spend an inordinate amount of time explaining the basic law in the case.

Assist the court in making findings of fact and conclusions of law.

Make logical and ethical arguments. Do not seek to appeal the judge’s emotions, except as telling of the facts evokes emotion.

Be concise and to the point.

Be candid, accurately stating the facts and law, and conceding what should be conceded.

Delivery

Counsel should:

Project sincerity;

Avoid distracting behavior, such as pacing back and forth;

Maintain eye contact with jurors or judge;

Deliver the closing with a minimal outline;

Position her body to hold the fact finder’s attention; and

Make purposeful movements.

Counsel should use trial visuals effectively:

Ensure use is permissible,

Make visuals persuasive,

Position equipment and visuals appropriately, and

Have a backup plan if equipment malfunctions.

Ethical Boundaries

Counsel should not state a personal opinion.

Counsel should not venture outside the record.

Counsel should not introduce irrelevant matter.

Counsel should not invoke the golden rule.

October 16, 2023

DON’TS OF MEDIATION

Charles Burdell

Charles BurdellIt’s worth repeating--the DON'TS OF MEDIATION. They were written by Charles Burdell and published in the King County Bar Association Bar Bulletin. Charlie Burdell had a career it private practice, and he later became a King County Superior Court Judge before becoming a full-time arbitrator and mediator. His Bar Bulletin list of mediation mistakes to avoid reads as follows:

Don’t oversell the client’s case to the client: No case gets better than the first day it walks into your office. Be sure to temper your early assessment of the value of your client’s case until you get an idea of the facts from the other side’s perspective. Many times in mediation, especially of personal injury cases, the clients are frustrated when they are confronted with settlement which is far less than they were advised when their attorney was retained.

Don’t represent multiple plaintiffs in personal injury actions without providing “informed consent”: RPC 1.8 (g) provides that a lawyer “who represents two or more clients shall not participate in making an aggregate settlement of the claims” unless each client gives informed consent in writing. It is surprising how many lawyers come to mediation representing multiple clients injured in the same tort without any objective way to allocate a settlement and without obtaining the clients’ prior informed consent. The best practice is to either obtain the clients’ informed consent prior to accepting the representation or just represent the client with the best case and refer the other injured party to your law school classmate!!

Don’t participate in mediation without all the stakeholders present: Obviously, your client should be in attendance along with all decision makers. However, don’t forget to at least inform lien holders of the mediation and invite their participation either in person or on the phone.

Don’t miss an opportunity to explain your case to the other side in a business like, professional manner. If your mediator suggests an initial joint session, this is a golden opportunity for you to explain your case to the decision makers on the other side, without the filter of the opposing attorney. You should direct your comments to the decision maker and in a calm, professional and business like fashion, thank them for participating in the mediation, tell them why you are right and why they should agree with you.

Don’t participate in a mediation without providing the other side with a copy of your submission: A copy of your submission will create a professional duty in your opponent to provide your version of the case to her client. If you need to inform the mediator of something confidentially, send a second, private letter. This is especially important for the defendant in a personal injury case. Having your letter laying around the plaintiff’s home, gives family members a chance to understand there are two sides to the story. Also, and most important from the standpoint of closing settlement, giving your submittal to the plaintiff’s attorney, allows her to send it to the lien holders so they can understand the validity of the suggestion that they reduce their liens to enable settlement.

Don’t arrive at the mediation without an up-to-date summary of costs to be charged to your client’s recovery: Uncertainty regarding the costs expended is a frequent mistake. This is a very important calculation, because it directly affects the net recovery for a plaintiff in a personal injury case.

Don’t make unreasonable settlement proposals: In criminal law, a “reasonable” doubt is a doubt for which a reason exists. Similarly, a reasonable settlement offer is one for which a reason exists. When faced with an unreasonable proposal from the other side, keep the “white hat” on your head by instructing the mediator to tell the other side that you believe the proposal unreasonable and are ignoring it. You are making what you believe to be a reasonable offer, one which is not in response to the other sides’ unreasonable proposal.

Don’t wait until midnight, when a settlement number has finally been reached, to propose non-financial issues like confidentiality: If confidentiality is important to your client, raise it in the materials you submit to the mediator and to the other side and make sure the mediator communicates it with your first offer. Nothing derails an arduous negotiation more than raising new issues late in the discussion.

Don’t be a stick in the mud: Be open to creative solutions to reach settlement. When Supreme Court Justice Bobbi Bridge began her legal career on the King County Superior Court, she observed a morning judicial settlement conference I conducted. The parties were involved in a dissolution and the value of a diamond ring was in dispute. The parties agreed on the cut, color and clarity of the diamond, but disagreed on the value. Justice Bridge’s husband, John, was President of Ben Bridge Jewelers. At my suggestion and with the concurrence of Justice Bridge, the parties agreed that we could call Mr. Bridge, give him the characteristics of the diamond and obtain his opinion as to its value. We did, he gave us a value and the case settled!

Don’t come unprepared to any mediation, especially an early mediation: Since most civil litigation settles, and since many settlements occur at mediation, it is extremely important to be well prepared and able to empower your mediator with the necessary information to convince the other side to agree with you. Further, especially in early mediations, it may well be the first time your client sees you in action. Early mediations are usually conducted before anyone has been deposed. Remember, your mediator is only as powerful as you make her. Be sure to have all the important facts marshalled and ready to assist the solution. Also, don’t miss a settlement opportunity because an important witness has not been deposed. Have the witness available by telephone and conduct a conference call to ask the witness on an informal basis what happened.

Don’t ask for or agree to non-disparagement clauses: These clauses simply provide litigants who have just finalized a dispute with yet another cause of action. Especially in business dissolutions, you can be sure the parties have disparaged each other for the entire life the lawsuit and probably before. It is very easy for rumors of this conduct to be repeated after the settlement by third parties, which, when overheard by one of the parties, may cause another lawsuit. The best advice to give your client who worries about being disparaged after settling the case is for the client to “consider the source”.

Don’t settle your case on a handshake: Always prepare and sign an agreement memorializing the settlement you reach at the mediation. If more formal documents are necessary, write something like “The parties contemplate the preparation and execution of more formal documentation memorializing this settlement agreement.” This will prevent your settlement from becoming the proverbial “agreement to agree” and if you are not able to agree on the “more formal documentation”, your mediation settlement agreement will remain in force and prevail.

Don’t confuse the mediator: Be sure to state in the first paragraph of your mediation submittal which party you represent. Many lawyers, having lived a case for its entire life, forget that the mediator is new to the problem and has no idea which party the lawyer represents. If not informed early in the submittal, the mediator has to try to figure it out. Also, it’s a good idea in the second paragraph of your submittal to explain why you will win.

Reprinted by permission of the author Charles Burdell. Originally published in the February 2015 issue of the King County Bar Association Bar Bulletin. Reprinted with permission of the King County Bar Association.

October 11, 2023

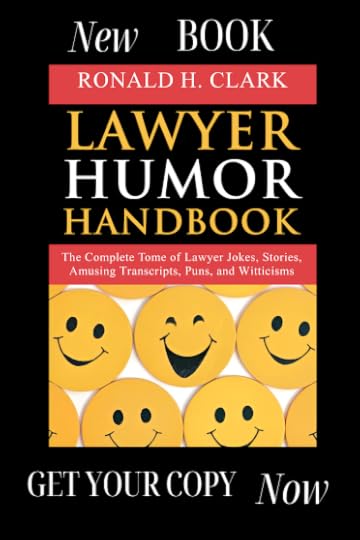

New Book: Lawyer Humor Handbook

I’ve spent my adult life as a lawyer and law professor, and I believe that practicing law is engaging in a noble profession. Nonetheless, I do enjoy and laugh at lawyer jokes, humorous stories about lawyers’ faux pas, law puns, and other such witticisms, and I want to pass them on to you.

Humor can be an invaluable way to break the ice when giving a presentation. Amusing anecdotes can enliven any speech. Lawyer gaffes can serve as illustrations of mistakes to avoid when practicing law, such as suffering the backfire from asking a “Why” question on cross-examination. Lawyer jokes also show the human side of lawyers.

Consequently, I have with diligence and arduous, exhaustive research compiled this brand-new authoritative LAWYER HUMOR HANDBOOK: The Complete Tome of Lawyer Jokes, Stories, Amusing Transcripts, Puns, and Witticisms.

The Handbook is chockfull of witticisms, including: 210 humorous lawyer stories, 62 courtroom transcripts with lawyer gaffes, 83 question and answer lawyer jokes, 19 law school amusements, 38 punchy puns and word-play bits, 2 Legal writing funny pieces, and 26 hilarious one-liners.

I hope that you get some chuckles from this Lawyer Humor Handbook and pass the jests you like on to others (the Handbook is a great gift for a lawyer) unless they can’t take a lawyer joke.

October 6, 2023

Book Review: Eradicating American "Prosecutor Misconduct"

September 29, 2023

Time to Go to the Movies to Learn Trial Advocacy

For more reviews and more about the book click on the following: Trial Advocacy Goes to the Movies: Go to the Movies for Lessons in Trial Strategies, Techniques and Skills

September 27, 2023

How to Prepare a Witness for Trial--Especially Cross-Examination

Even when opposing counsel is equipped with the skills and strategies covered in Cross-Examination Handbook, they will not have enough to do damage to the credibility of a tough witness. A tough witness is one who is armed with the truth and has been thoroughly prepared to testify at trial.

What is entailed in the thorough preparation of a witness for cross-examination? The following is an indispensable checklist along with notes for thorough and effective witness preparation that you can use when you prepare your witness. And, when you come up against the tough witness, you know that opposing counsel has relied upon a similar checklist.

Preparation for the courthouse and courtroom:

– Courthouse – where is it? Note: It is not unheard of that a witness will go to the wrong courthouse or courtroom. Tell your witness not only where the courthouse is but also where the courtroom is located.

– Courtroom Layout. Notes: Much of your witness preparation is designed to familiarize the witness with everything. Most people have a fear of the unknown, and this preparation can alleviate some of that fear. Either show the witness a diagram of the courtroom or take the witness to the courtroom. If you have a child witness, definitely take the child to the courtroom, have the child sit in the witness chair and otherwise learn about the courtroom. Tell the witness who the courtroom players are and where they will be positioned in the courtroom, such as where the clerk, bailiff and court reporter are situated (except for the defendant in a criminal case which could result in a mistrial).

– Don’ts: Notes: Tell the witness not to discuss case in or around the courthouse. because jurors may be on the street around the courthouse or in the halls or on the elevator. Instruct the witness to not enter the courtroom until summoned because witnesses are excluded. This does not apply to the client(s) and to the detective in a criminal case.

Preparation on the witness’s role and substance:

– Witness’s Role. Notes: Tell your witness to tell the truth. If it hurts, tell the truth. Tell your witness that the only instruction that you have given them regarding what to say is—tell the truth. Ask the witness, “What damaging information is out there?” You need to know because only if you know what it is, can you deal with it.

– Review Prior Witness Statements. Notes: Have the witness review all prior witness statements that the witness has given. Tell the witness before the witness goes over the statement that the witness should not feel wed to what is in the statement. If there is something erroneous, the witness should let you know.

– Cover the Witness’s Story. Notes: Go over the witness’s story in detail and probe for any weaknesses. If there is a weakness, have the witness explain. Witnesses are commonly not good at estimating things like time and distance. Go over this. For example, if the witness says that the two individuals were five feet apart, have the witness show you how far they were apart using objects in the room.

– Practice Direct Examination. Notes: Walk through it. Practice with exhibits and demonstrations

– Practice Cross-Examination. Notes: Explain to the witness that you are going to step into opposing counsel’s shoes and conduct a cross-examination (you may have another colleague do it). Ask tough questions that you expect from the other side. Tell your witness not to worry about cross-examination because the witness is telling the truth.

Preparing the Witness on How to Testify:

– MRPC 3.4(b) prohibits coaching to testify falsify. Notes: However, you can help the witness be a good communicator. Help the witness be Confident, Clear and Credible.

– 1. Have a Good Appearance. Notes: Tell the witness to dress appropriately for court. When sitting in the witness chair, the witness should have good posture—sit up straight. Speak clearly, and here you can explain the role of the court reporter and the need to speak clearly and not to rapidly. The witness should avoid distracting habits, such as chewing gum or fiddling with a pen.

– 2. Courtroom Rules. Notes: Tell the witness that if there is an objection, stop talking and listen for directions regarding what is to be done next. Tell the witness that if they can’t remember something, say so. And, explain how you may seek to refresh recollection if the witness can’t recall and the procedure for refreshing recollection.

– 3. Communication on Direct. Notes: Tell your witness that only the jury counts, and that the witness should talk to them. If court procedures permit, explain that you will stand at the end of the jury box so that the witness will be looking down the jury box towards you. Tell the witness that this courtroom positioning is intended to remind the witness both to speak up so the furthest away jurors can hear and to look the jurors in the eyes and talk to them as though they were having coffee together. Tell the witness that the jurors have no axe to grind with the witness and they are just trying to learn the truth, which the witness will deliver.

– 4. Communication on Cross. Notes: Discuss keeping composure on cross. You can explain that the witness should never get cute or argue with the questioner. To assist the witness with that endeavor, you can explain that while the witness will not be able to address the jury after testifying, counsel may and in doing so, counsel can comment on the witness’s lack of composure and how the witness’s demeanor showed the witness was not credible. Explain that contrary to direct examination when the witness should look at the jurors, during cross, the witness should look directly at counsel. Instruct the witness listen carefully to the question that is asked and answer it directly. Don’t volunteer information.

September 20, 2023

HUMOR: LAUGHABLE LEGAL WRITING

I'm currently working on a new book on Lawyer Humor and this is a piece of it.

Law schools should focus on producing professional communicators—lawyers—who are effective writers. However, Bryan A. Garner in his column for the ABA Journal titled, “Why Lawyers Can’t Write” with the subtitle: “Science has something to do with it, and law schools are partly to blame.” stated:

While lawyers are the most highly paid rhetoricians in the world, we’re among the most inept wielders of words. Stop and think about that. The blame goes primarily to law schools. They inundate students with poorly written, legalese-riddled opinions that read like over-the-top Marx Brothers parodies of stiffness and hyperformality. And they offer law students little if any feedback (on substance, much less style) from professors on exams and writing assignments. (ABA Journal, March 2013, p. 24)

Garner was echoing the theme of Jim McElhaney, advocacy instructor and ABA Journal contributor for 25 years, who wrote this in a September 2012 ABA Journal article:

Law school is as much obscure vocabulary training as it is legal reasoning. At its best, it can teach close thought and precise expression. But too often law school is reverse Hogwarts – where Harry Potter trained to be a wizard – that secretly implants into its students the power to confuse other people instead of sowing the magic seeds of clarity and simplicity. So we lard our speech and writing with words and phrases of awkward obscurity and rarely have anything to do with legal precision but that unmistakably say, ‘This was written – or said – by a lawyer.’

Because we are professional communicators, it is our obligation to be plain and simple. It’s not our readers’ and listeners’ jobs to try to understand us. It’s our job to make certain that everything we write and say commands instant comprehension.

And because we weren’t turned out that way by our law school training, we have to reprogram ourselves if we want to be effective communicators.

One day in contract law class, the professor asked one of his better students, "Now if you were to give someone an orange, how would you go about it?"The student replied, "I’d write a contract that says, ‘Here's an orange.’"The professor was livid. "No! No! Think like a lawyer!"The student then responded, "Okay, I'd write, ‘I hereby give and convey to you all and singular, my estate and interests, rights, claim, title, claim and advantages of and in, said orange, together with all its rind, juice, pulp, and seeds, and all rights and advantages with full power to bite, cut, freeze and otherwise eat, the same, or give the same away with and without the pulp, juice, rind and seeds, anything herein before or hereinafter or in any deed, or deeds, instruments of whatever nature or kind whatsoever to the contrary in anywise notwithstanding...’"Here is another example—in a pretrial ruling on a motion for a more definite statement in a complaint, the Honorable Ronald B. Leighton, United States District Judge, Western District of Washington at Tacoma, Washington provided gems of judicial humor when discussing a pleading. In Presidio Group, LLC, vs. GMAC Mortgage, LLC. Judge Leighton's order granting the motion began with William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2, Line 90: “Brevity is the soul of wit.”

The good Judge then went on to point out that “(b)revity is also the soul of a pleading. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(a). The Federal Rules envision a “short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief.” He then described portions of the 465-page Complaint:

Not before page 30 does the Complaint address the facts alleged. Plaintiff’s allegations continue for 87 pages – including a 37-page pit-stop to quote e-mails. (Compl. 39-76). The Court notes, with some irony, that in his response opposing Defendants’ motions for a more definite statement, the Plaintiff successfully states his allegations in two pages.

Then, in granting the motion, Judge Leighton added a bit of his own poetry:

Plaintiff has a great deal to sayBut it seems he skipped Rule 8(a),His Complaint is too long,Which renders it wrong,Please re-write and re-file today.To assist lawyers, Sally Bulford, a Utah prosecutor, provided these witty writing pointers for lawyers under the title “How to Write Good”:1. Avoid alliteration. Always.2. Prepositions are not words to end sentences with.3. Avoid cliches like the plague. (They're old hat.)4. Employ the vernacular.5. Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.6. Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary.7. It is wrong to ever split an infinitive.8. Contractions aren't necessary.9. Foreign words and phrases are not apropos.10. One should never generalize.11. Eliminate quotations. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "I hate quotations. Tell me what you know."12. Comparisons are as bad as clichés.13. Don't be redundant; don't use more words than necessary; it's highly superfluous.14. Be more or less specific.15. Understatement is always best.16. One-word sentences? Eliminate.17. Analogies in writing are like feathers on a snake.18. The passive voice is to be avoided.19. Go around the barn at high noon to avoid colloquialisms.20. Even if a mixed metaphor sings, it should be derailed.21. Who needs rhetorical questions?22. Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

September 10, 2023

New: Handbook for Public Speaking at Trial and Beyond

New handy Handbook for public speaking at trial and on other occasions. Click here for the book on Amazon

September 4, 2023

Humor: How to Bungle Trial Visuals

Chapter 15 of my book Visual Litigation and Today’s Technology focuses on the six prerequisites for an effective courtroom presentation. Those requirements are described as follows:

Six prerequisites must be fulfilled before you can effectively display visuals in a courtroom. First, if the courtroom is not fully technologically equipped, counsel will need to provide the required hardware, such as a computer, tablet, screen, projector, cords and so on. Second, counsel will need to adhere to the court’s rules and procedures. Third, counsel will need backups in case of a technological failure. Fourth, the person who is going to operate the technology needs to test the equipment and practice using it. Fifth, the courtroom must be staged properly so the audience can see and hear what is being shown. Sixth, courtroom communication between the trial lawyer and operator of the equipment must produce a smooth presentation of the visual.

The video clip from Jury Duty, which is a truly hilarious movie, is a perfect illustration of a violation of the fourth and fifth prerequisites. Watch it and enjoy