Ronald H. Clark's Blog, page 8

April 18, 2023

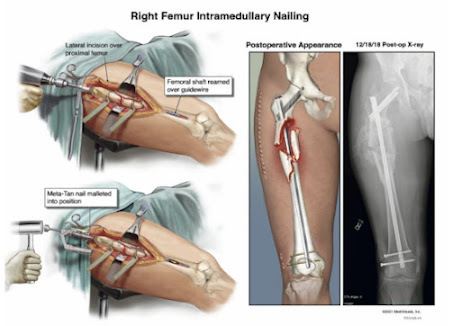

If You Need Professional Medical Illustrations for Trial

MediVisuals is a professional designer that we spotlight in our Visual Litigation: Visual Communication Strategies and Today's Technology book because it produces exceptional exhibits that can serve as visual aids for experts to use in teaching the jurors. This month, the Daudy Law Firm got a $7 million jury verdict in an auto collision case and MediVisuals, the vendor who created their trial visuals, quoted their clients as follows:

“Will McBride and I would like to thank MediVisuals for the half-dozen medical illustrations they provided for us on our most recent case. When settlement offers were originally being discussed the insurer would not increase their offer above $250,000 before trial. The color medical illustrations with companion imaging films enabled the medical experts to engage with the jury to teach them about the nature and extent of the injuries and surgeries needed from the trauma. The Medivisual exhibits enabled the experts to simplify the complex and complicated injury issues confronting the jury, which returned a $7 million verdict a bit more than the defense pre-trial offers of $250,000. With us being in the “show” not “tell” business, the illustrations from MediVisuals enabled us to abbreviate the trial from 7 to 3 days of jury time. The jury returned our respect for their time with their verdict.”

If your client can afford to employ a professional designer, MediVisuals is the type of vendor that you might consider.

April 12, 2023

CRITICAL IMPORTANCE OF TRIAL AND PRETRIAL ADVOCACY CHECKLISTS

Checklists are critical to pretrial and trial work. To illustrate the importance of checklists, Dr. Atul Gawande tells the true story of an October 30, 1935 airplane flight competition that the U.S. Army Air Corps held at Wright Air Field in Dayton Ohio to determine which military-long range bomber to purchase. Boeing’s “flying fortress” was the likely winner. But, after the plane reached three hundred feet, it stalled, turned on its one wing and crashed, killing its pilot and another of its five crew members. The pilot had forgotten to release a new locking mechanism on the elevator and rudder controls. The plane was dubbed “too much airplane for one man to fly.”

Nevertheless, a few of the Boeing planes were purchased, and a group of test considered what to do. They decided that the solution was a simple pilot’s checklist. With the checklist in use, pilots flew the B-17 1.8 million miles without an accident. Dr. Gawande in his book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right (p. 34) concludes, “Much of our work today has entered its own B-17 phase. Substantial parts of what software designers, financial managers, firefighters, police officers, lawyers, and most certainly clinicians do are now too complex for them to carry out reliably from memory alone. Multiple fields, in other words, have become too much airplane for one person to fly.”

Dr. Gawande who heads the World Health Organization’s Safe Surgery Saves Lives program recounts that after the World Health Organization introduced the use of checklists for surgeons, research of nearly 4000 patients showed the following: major complications fell 36 percent; deaths fell 45 percent; infections fell almost 50 percent. Rather than the expected 435 patients expected to develop complications, only 277 did. The checklist spared 150 patients from harm and they spared 27 of those 150 from death. (The Checklist Manifesto, p. 154)

Just as checklists are critical for pilots and doctors, they are necessary for trial lawyers as well. At the end of almost every chapter in both of our new Pretrial Advocacy, 6th Edition and Trial Advocacy 5th Edition is a checklist of matters that are essential to effective pretrial and trial advocacy. The following is an example of a checklist that follows the Closing Argument chapter in Trial Advocacy

CLOSING ARGUMENT CHECKLIST

Preparation

Preparation begins soon after entry into the case. Counsel should keep notes of ideas for closing.

Prior to trial, write the closing argument, with final editing during trial. Reduce closing to outline notes.

Rehearse closing argument. Just like opening statement, commit concluding remarks to memory so they will flow smoothly.

Content

Case theories should serve as guides for planning closing.

Regarding the legal theories, jury instructions, among others, serve as the core around which to craft closing argument:

Elements of the claim or defense,

Burden of proof,

Issues in dispute, and

The other side’s case theory.

In arguing the factual theory, counsel should use jury instructions that pertain to crucial facts, as well as a story embodying those facts.

The case theme should be incorporated into the closing.

Closing should meet the other side’s case theory and attacks.

Juror beliefs and expectations that could be detrimental to the case should be identified, met, or distinguished from your case.

Length

Length of closing should be suitable to the complexity of the case, and should not run overly long.

Aristotelian Appeals

Closing should make all three appeals: logical, emotional, and ethical.

Persuasive language should include:

Words with connotations, and

Rhetorical devices, such as postponement, concession, anti¬thesis, metaphors, similes, analogies, and rhetorical questions.

Structure

The closing should begin by seizing the jury’s attention.

The body of the closing should be well organized, emphasizing the strengths of the case before dealing with case weaknesses or the other side’s attack.

The closing should conclude by referring to the theme and reasons for the requested verdict, thus motivating the jury to make the right decision.

Rebuttal should refute the other side’s arguments and finish strong.

Bench Trial

Counsel should:

Be prepared to answer the judge’s questions during closing.

Not spend an inordinate amount of time explaining the basic law in the case.

Assist the court in making findings of fact and conclusions of law.

Make logical and ethical arguments. Do not seek to appeal the judge’s emotions, except as telling of the facts evokes emotion.

Be concise and to the point.

Be candid, accurately stating the facts and law, and conceding what should be conceded.

Delivery

Counsel should:

Project sincerity;

Avoid distracting behavior, such as pacing back and forth;

Maintain eye contact with jurors or judge;

Deliver the closing with a minimal outline;

Position her body to hold the fact finder’s attention; and

Make purposeful movements.

Counsel should use trial visuals effectively:

Ensure use is permissible,

Make visuals persuasive,

Position equipment and visuals appropriately, and

Have a backup plan if equipment malfunctions.

Ethical Boundaries

Counsel should not state a personal opinion.

Counsel should not venture outside the record.

Counsel should not introduce irrelevant matter.

Counsel should not invoke the golden rule.

April 5, 2023

Humor: "How to Write Good"

I've often written here that law schools train lawyers to be bad communicators. This post again bears repeating again. Sally Bulford, a Utah prosecutor, provided these humorous writing pointers under the title “How to Write Good”. Enjoy!

1. Avoid alliteration. Always.

2. Prepositions are not words to end sentences with.

3. Avoid cliches like the plague. (They're old hat.)

4. Employ the vernacular.

5. Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.

6. Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary.

7. It is wrong to ever split an infinitive.

8. Contractions aren't necessary.

9. Foreign words and phrases are not apropos.

10. One should never generalize.

11. Eliminate quotations. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "I hate quotations. Tell me what you know."

12. Comparisons are as bad as clichés.

13. Don't be redundant; don't use more words than necessary; it's highly superfluous.

14. Be more or less specific.

15. Understatement is always best.

16. One-word sentences? Eliminate.

17. Analogies in writing are like feathers on a snake.

18. The passive voice is to be avoided.

19. Go around the barn at high noon to avoid colloquialisms.

20. Even if a mixed metaphor sings, it should be derailed.

21. Who needs rhetorical questions?

22. Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

April 2, 2023

FIVE STORYTELLING TIPS FOR A WINNING OPENING STATEMENT

Storytellers have techniques that they use to bring the story to life and make it persuasive, engaging, and interesting. These are techniques you can employ when crafting and delivering an opening statement. Here are five tips:

1. ViewpointTo be effective, a story should be told from a viewpoint. When the story is told from a viewpoint it is more likely that jurors will connect with it. There are at least three viewpoints to select from: (1) Your client’s viewpoint or the victim’s viewpoint if you are a government lawyer; (2) the third person’s or reporter’s viewpoint - like the Greek Chorus looking down on the play’s action, and (3) the omniscient viewpoint – the shifts from one viewpoint to another.

2. Language

The language you use in opening should be clear, simple, and devoid of any legalspeak. Don’t do this: • “The decedent walked into the room.”• “Let’s consider the points of impact between my client’s vehicle and the adverse vehicle.”• “The aforementioned party subsequently was wrongfully terminated.”

3. Details

Give the jurors too many details and the story gets lost. Give them and too few details, and the story isn’t real. Eliminate unnecessary details that clutter the story. Include details that make the story come alive and become real.

4. Word Pictures

If you want to evoke emotion, paint word pictures. Look at this paragraph and read it as fast as you can: Aocdcrnig to a rsereearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it dse-no’t mtaetr in what oerdr the ltteres in a word are, the olny iproamtnt thing is that the frsit and lsat ltteer be in the rghit pclae. This is bcuseae the human mind deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the word as a wlohe. Olny 57% of plepoe can do it.Interesting—isn’t it? Our brains don’t think in words or numbers—we convert them into pictures. We convert words into pictures and emotions. Language does this. We see words. Go right to it – paint pictures and create emotions.

5. Word Choice

The words you select can be ones that y reach the mind and move the heart. There is a big difference between “she said” and “she begged.” When the story calls for it, pick the right words to express emotion.

If you found these storytelling tips useful, you could get a copy of my new book Addressing the Jury: Opening Statement and Closing Argument. This short book is reasonably priced at $8.99 for the Kindle ebook and $9.29 for the paperback. Click here to get your copy.

March 21, 2023

WRITING BRIEFS AND MOTIONS: 10 DOS AND DON'TS

What do judges want in briefs and motions? After interviewing over 1,000 federal and appellate judges about dos and don'ts for writing motions and briefs, Ross Guberman, president of Legal Writing Pro and the author of “Point Made: How to Write Like the Nation’s Top Advocates”, wrote the article “Judges Speaking Softly: What They Long for When They Read”.

It's worth repeating here the dos and don’ts that Guberman settled on after he conducted his survey as they were summarized in the Around the ABA (for sharing):

1. Do a name check. The judges prefer words to acronyms, and one wrote, “I absolutely detest party labels (plaintiff, debtor, creditor, etc.). Name names, for God’s sake!” Another likes to see names so as not to forget who’s who.

2. Stay classy. The judges agree briefs should show, not tell. “Avoid phrases and sentences that reflect a lack of civility. Don’t belittle the other side’s arguments but rather focus on your own strengths,” wrote one judge. Another warned that “words such as ‘clearly,’ ‘plainly,’ ‘obviously,’ ‘absurd,’… are crutches intended to prop up weak arguments that lack logical force.”

3. “Slash windups and throat clearing.” The judges do not look fondly on long introductions, and words that “waste space” such as, “it should be noted that…” and “it is beyond doubt that….”

4. Use graphics effectively. Timelines, maps, graphs, diagrams, tables, headings and generous margins all get a thumbs-up from the judges on the basis of clarity and as a counterweight to “dry legal analysis.”

5. Avoid clunky legalese. The judges agreed phrases such as “for the foregoing reasons…,” “heretofore,” “aforesaid” and “to wit” “should go the way of the dodo bird.”

6. Don’t be cloying. As much as phrases such as “defendant respectfully submits” sound respectful, the judges would rather just see “defendant contends.”

7. Assume the judge understands the finer points of usage and write accordingly. The judges unloaded on their pet peeves, including using “impact” as a verb, improper use of “that” and “which” and misuse of the subjunctive.

8. Explain why you should win in the introduction. The judges want to read a first page that says something like “The Court should deny Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment for the following three reasons.”

9. Be succinct when citing cases. One exasperated judge opined, “Skip the long description. Just state the damn proposition, cite the damn case and be done with it.”

10. Put citations in the text, not in the footnotes. Judges are reading your work on an iPad, and most would rather not scroll to the end to read a footnote. “This is a show-your-work gig, and I need to see your work there – not go hunting for it,” one wrote.

March 16, 2023

Podcast about Learning by Watching: New Pretrial and Trial Advocacy Books

Recently, Marilyn Berger & I were on the Aspen Leading Edge podcast with Dean Patty Roberts to discuss the future of law schools and our new Pretrial and Trial Advocacy books. Click here to listen to the broadcast now.

March 7, 2023

New: Trial Advocacy: Planning, Analysis, and Strategy 5th Edition

The new edition of Trial Advocacy has just been launched and Aspen Publishing's announcement is as follows:

Click on this link to go to the publisher's website and Professors can get a review copy there

Trial Advocacy, Fifth Edition equips trial lawyers, students, and professors with a complete set of tools for practicing the art of trial advocacy, including explicit instructions on planning, strategy, and performance for each phase of a trial from jury selection to closing argument with illustrations of both criminal and civil trial activity. An accompanying movie features trial demonstrations by veteran trial lawyers; a regularly updated website provides articles, supplemental materials, downloads, and links to additional resources.

New to the Fifth Edition:

• Case law and rules of procedure, evidence, and professional responsibility are updated to reflect the latest changes.

• The COVID pandemic has had a big impact on litigation practice. The Fifth Edition tracks these developments in trial advocacy today:

o Jury selection procedures and strategies for online trials.

o Preparing witnesses to testify online.

o Direct and cross-examination of witnesses online.

o Introducing and displaying exhibits online.

o Advancements in technology for creating persuasive visuals in the courtroom or online.

• This new edition is now available in print and on the popular Casebook Connect online platform.

• This new edition keeps pace with the advancements in technology, particularly electronic visuals.

• Foundations for testimony have been added, giving the new edition comprehensive coverage of evidentiary foundations for admissibility along with illustrative transcripts of predicate questions.

• Chapter 15 “The Cases and Assignments” containing 79 trial advocacy performance assignments is added to the book.

Teaching Materials:

• Checklists for each chapter for easy teachability

• Both civil and criminal case files for the performance assignments

• Actors’ Guide for the performance exercises

• Teacher’s Manual with course syllabus

• Videos of jury trial demonstrations

• Companion website: CasebookConnect.com

To learn more about this title or view the detailed table of contents,

please visit our website.

To access teaching materials for this title once they are available, you will need a validated professor account on AspenPublishing.com. If you do not yet have a validated professor account, you may register at AspenPublishing.com/my-account/register. Account validation may take 1-2 business days. Once validated, you may log into your account using your own personal login, go to the product page for this title or any Aspen Publishing title, and scroll down to access the Professor Resources once they have been made available on the site.

February 28, 2023

NEW BOOK: Eradicating American "Prosecutor Misconduct"

Just published is Eradicating American Prosecutor Misconduct”: A Handbook for Prosecutors, Criminal Defense Attorneys and Others Interested in Criminal Justice. This short yet comprehensive Handbook is designed for both prosecutors and defense counsel alike. Its modest goal is to eradicate what is called “prosecutor misconduct”. While this Handbook may serve as a guidebook for prosecutors, it also arms defense counsel with information that can be used to ensure that their clients receive a fair trial.

An example of how the Handbook simultaneously guides prosecutors and arms defense counsel is that it spells out what a prosecutor is prohibited by law and ethical rules from saying in trial. By identifying what a prosecutor is not permitted to say in trial, it not only tells prosecutors what not to do but also provides defense counsel with grounds and legal authority for either an objection, a motion for mistrial, or an appeal if the trial judge overrules the objection or denies the motion.

This Handbook is also intended for anyone who wants to understand the real roles and functions of the American prosecutor. There is a wide-spread public misunderstanding (even among lawyers, law professors, and law students) of the prosecutor’s roles and functions. These misconceptions are to a significant degree caused by movies, television shows, and books that cast prosecutors as antagonists in their narratives.

Eradicating American "Prosecutor Misconduct" traces the unique character of the American prosecutor from its origins to today because only by understanding that history can the roles and functions of a modern prosecutor be fully appreciated.

This Handbook is an outgrowth of Continuing Legal Education presentations on prosecutor professionalism that I delivered across the nation. It offers engaging and educational examples of prosecutor error along with the words from a cross-section of state and federal appellate courts describing both what and why certain prosecutorial conduct is prohibited. In sum, it offers learn-by-example lessons of what a prosecutor should not do in pretrial and trial.

February 22, 2023

PRACTICING JURY SELECTION

The Critical Importance of Practicing Your Voir Dire

This article by Thomas M. O’Toole, Ph.D. is worth a reread:

Despite what Allen Iverson might say (search “Allen Iverson” and “practice” on YouTube if you do not get this reference), practice is essential to the successful development of any skillset. In competition, competitors get better by practicing. This is why it is surprising to me that most attorneys do not practice their voir dire before the day of jury selection, particularly when so many also preach about primacy theory and the need to make a good impression right off the bat.

Statistics indicate that fewer and fewer cases make it to trial, which means most attorneys have had few opportunities to conduct voir dire. Even for experienced attorneys, it may have been years since the last time they picked a jury. Additionally, jury selection is not something that comes natural to most attorneys as it is the opposite of what most attorneys are used to doing – arguing as opposed to listening. Many attorneys admit that they do not like voir dire and that it is the one thing about trial that makes them nervous. The anecdote to all of this is PRACTICE. Practice will make you better.

Some of the best attorneys at voir dire that I have seen are former prosecutors. These are attorneys who have spent a lot of time in the courtroom picking juries, meaning they have more practice than most. They have done it so many times that they have honed their skillset and can conduct an effective and efficient voir dire. Despite this experience, some former prosecutors will still tell you that they still practice their voir dire.

This article addresses the importance of practicing voir dire and how to effectively do so.

Let’s start with some clarity on what constitutes practice. I’ve often had attorneys tell me they practiced their opening statement when the reality is that they just sat in their office and silently read through it to themselves. That is not practice. Like opening, true practice requires that you stand up and deliver the voir dire. How something reads on paper and how it sounds when it comes out can be very different. You may find that a voir dire question you have scripted for yourself does not sound right, or is too choppy, when delivered. This is something that should be discovered during practice, not during the actual voir dire. The latter has the potential of making you look disorganized, nervous, inarticulate, and ill-prepared, which is not the ideal first impression. When these mistakes happen in live voir dire, it is not unusual for an attorney to just scratch the question and move on, which means a potentially important issue has been skipped over.

If you are in federal court, practice becomes even more important since you will likely only receive ten to fifteen minutes for your voir dire, which means you must be incredibly organized and efficient. Every error takes away from your precious time to learn important information about your jury pool.

While practicing the delivery of your voir dire by yourself is a step in the right direction, it is even more valuable to practice in front of a group of people. This will create a more “real-world” feel to the practice. It also creates an opportunity to get feedback on your questions. Sometimes, a question makes perfect sense to you, but the potential jurors do not understand what you are trying to ask. Maybe it is because you know the issues in your case too well and certain questions make sense to you, but not too someone totally unfamiliar with the case. Practicing with a group of people will get you that feedback. An easy way to get a group of people is to ask folks from your office to volunteer to meet for thirty minutes or so and play the role of prospective jurors. If you work in a small office, consider getting a group of friends together at your house. Another option is to recruit some mock jurors in order to create a more real-world environment of unfamiliar faces.

As you practice your questions with office members, friends, or mock jurors, track the information that you are learning from their answers. This will help you determine whether the questions you are asking are getting you the desired – that is meaningful – information. Sometimes, the idea of a particular question might seem brilliant, but when you ask it, you find that you do not learn what you thought you might learn.

I have had some attorneys express concerns about some voir dire questions, noting that they will probably only result in a few raised hands. However, this is exactly the point. You only have a few peremptory strikes, so you want to ask questions that identify those ideal candidates for a strike. A question that results in nearly everyone raising their hand does little to help you differentiate genuine strike candidates from the rest of the venire.

This process will also help you plan for how you are going to track the answers during voir dire. Ideally, you will have a colleague, paralegal, assistant, or someone else in court during jury selection who will track jurors’ answers for you. It is incredibly difficult to both conduct voir dire and track all the information at the same time. However, if you have no other choice than to do both, practicing ahead of time will help you figure out the best process for effectively completing both tasks. There are also a variety of jury selection software programs for iPads and PCs out there, such as iJuror or JuryLens, that you may want to consider.

Practice sessions help you hone your questions as well. In many respects, voir dire is an art. Knowing what information you need to get does not guarantee you will get it. The “art” is in crafting questions that make jurors feel comfortable disclosing this information, which involves not only the language, but the delivery as well. This may not be a big deal with simple issues, such as whether a potential juror has ever ridden on a train, but it becomes much more difficult on sensitive issues, such as political beliefs, demographic issues (e.g., financial situation), and other personal issues. Research has shown that people will often answer these kinds of questions based on what they believe the questioner wants to hear or what the socially-acceptable or appropriate answer is rather than providing the honest answer. Consequently, it is important to craft and deliver questions that make jurors feel comfortable being honest.

One type of question that is very effective is the forced-choice question. A forced-choice question presents two sides to an issue and asks who tends to agree with one particular side (i.e. the opinions that are a problem for you and your client). This kind of question is effective because, as you present the two sides, you are presenting them as reasonable, but divergent views. You are not casting any kind of judgment. For example, consider the following question: “I want to ask you about guns. I have some friends who hunt regularly and own quite a few guns. Consequently, they are very comfortable around guns. I have other friends who do not hunt and do not own any guns. Some of them openly tell me that being around guns makes them very nervous and uncomfortable. By a show of hands, how many of you are more like that second group of friends and, for whatever reason, are just very uncomfortable around guns?” In this example, I am presenting both sides as perfectly reasonable. Indicating that I have friends on both sides helps accomplish this. I conclude by asking very innocently, who tends to be like that second group of friends. This simple technique can help diffuse some of the issues that might prevent prospective jurors from fully disclosing their views.

Even after practicing, it is important that you not be afraid to make mistakes when you conduct your actual voir dire. Everyone makes mistakes and jurors understand this. How you cope with that mistake impacts your credibility. If a question comes out the wrong way or you misspeak, back up and start over. Some light-hearted self-deprecation works wonders here. I have seen attorneys make simple comments (after they make a mistake) along the lines of, “Wow, I really botched that one up. Let me try again.” It is okay to do this. It humanizes you and can contribute to your overall likability in the jurors’ eyes.

In summary, one of the most accurate claims about jury selection is that, while you cannot win your case during jury selection, you can certainly lose it there. Voir dire is a critical moment in any case. It creates first impressions about you as an attorney and about the case. Consequently, it is critically important to practice and refine your strategy so that you can perform at your best. The actual voir dire at trial should never be the first time you “practice” your questions.

Thomas M. O’Toole, Ph.D. is the president of Sound Jury Consulting. You can learn more at www.soundjuryconsulting.com.

Republished with author Thomas M. O’Toole’s permission. Originally published in the January 2019 issue of the King County Bar Association Bar Bulletin and displayed on its website with this notice: All rights reserved. All content of this website is copyrighted and may be reproduced in any form including digital and print for any non-commercial purpose so long as this notice remains visible and attached thereto.

February 15, 2023

Criminal Justice Reform: Stop History from Repeating Itself

“Oregon liquor agency head resigns amid bourbon scandal” reads the headline in this week’s newspaper. The director of Oregon’s liquor regulatory agency announced his resignation from Oregon’s Liquor and Cannabis Commission. The article states, “The funneling of the top-end whiskey to leaders of the state agency deprived well-heeled whisky aficionados of the bourbons and violated several Oregon state statutes, including one that prohibits public officials from using confidential information for personal gain, according to the commission’s investigation.”

“Oregon liquor agency head resigns amid bourbon scandal” reads the headline in this week’s newspaper. The director of Oregon’s liquor regulatory agency announced his resignation from Oregon’s Liquor and Cannabis Commission. The article states, “The funneling of the top-end whiskey to leaders of the state agency deprived well-heeled whisky aficionados of the bourbons and violated several Oregon state statutes, including one that prohibits public officials from using confidential information for personal gain, according to the commission’s investigation.”It’s a familiar story coming from a neighboring state. I prosecuted an almost mirror-image case that resulted in the stoppage of a similar corrupt practice by the Washington State Liquor Control Board. Oregon officials could have learned from what happened in Washington by reading Roadways to Justice: Reforming the Criminal Justice System . Here’s an excerpt from the book:

“The crusade to end public corruption wasn’t restricted to the police payoff system. In July 1971, the county grand jury, besides charging public officials involved in the payoff system also indicted the Washington State Liquor Control Board members—Chairman Jack C. Hood, Leroy Hittle, Donald D. Eldridge, and Garland Sponburgh—with grand larceny. Specifically, they were charged with appropriating state liquor and liquor decanters for their own use and with fraudulent appropriation of liquor and decanters. The Liquor Board members treated the state liquor like it was their own property, distributing it for political favors and events, including the governor’s Christmas party. All but Sponburgh were also charged with using their official positions to secure special privileges—obtaining liquor “without cost to themselves.” These two offenses were alleged to have been committed between January 1, 1968, and September 28, 1971.”

The account of what happened in the Washington case can be found in Roadways to Justice. As it is put in the introduction to Roadways, “This retrospective is intended to provide inspiration and guidance on how to achieve meaningful reform of the criminal justice system, and, equally important, how to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.