R. Scot Johns's Blog, page 19

December 12, 2011

The Cost Of A Kindle

Click to Visit iSuppli and Read More

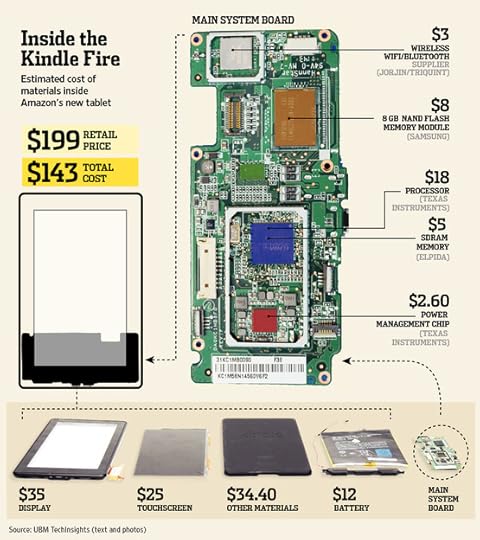

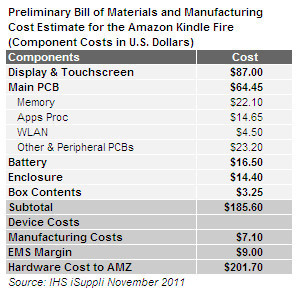

Here are a couple of breakdowns I've come across recently, showing the estimated production cost of the Kindle Fire. The one above is from the Wall Street Journal and pegs the total internal device cost at $143, but doesn't take into account a number of factors that the iSuppli chart at right does, namely labor and packaging, which increases the figure to a few bucks over their retail price of $199. In addition, neither factor in such additional expenses as software, licensing fees, or marketing, all of which would normally come out of the final retail price if the seller were only trying to make a profit on the product. But Amazon intends to make its money selling content for the device, not on the device itself, making the Kindle Fire more like a little portable storefront with an infinitely variable window display in which to show their wares. The Kindle Fire is, in fact, the Amazonian equivalent of a brick-and-mortar store, with a personalized bookshop in every house. Plus they sell other stuff too.

Published on December 12, 2011 06:00

December 11, 2011

Ebook Publishing Infographic Analysis

Here's another nice infographic put together by The Content Wrangler sizing up the current state of the ebook industry, based on the latest detailed survey of publishing professionals done by Aptara. This is the third annual survey, and it points out a number of enormous changes that have occurred over the past few years.

Foremost among them is the statistic given in the upper right of the infographic, showing that 62% of all publishers are now producing ebooks. Among trade publishers (i.e. non-corporate or educational), that number is 76%, with another 19% saying they have plans in place to begin ebook production. In the first Aptara survey of 2009 just 50% of trade publishers were producing digital editions. Only 6% now say they have no plans to do so.

Question 4: What is your organization's current involvement with eBooks?

Other highlights of the latest survey are that nearly one in five (18%) of eBook publishers generate more than 10% of their revenue from digital editions, although three times that many (57%) pull in less than 3% from eBooks, with 14% of publishers producing eBooks making nothing from their efforts thus far. This is a "strong statistic for an early-stage market" according to the survey findings, and shows that there is still a lot of room for growth.

Another interesting tidbit is that 10% of publishers intend to produce eBooks instead of print, while 85% plan to do both. Meanwhile, 37% now produce more than three-fourths of their titles as eBooks, with 32% converting less than one fourth of their output to digital. One stat not shown on the infographic is that two out of three publishers have yet to convert the majority of their backlist into eBooks, meaning there are a lot of older titles out there still waiting to be released as eBooks.

Amazon still holds the lion's share of the eBook market, but that share is shrinking as publishers begin to sell from their own e-commerce sites.

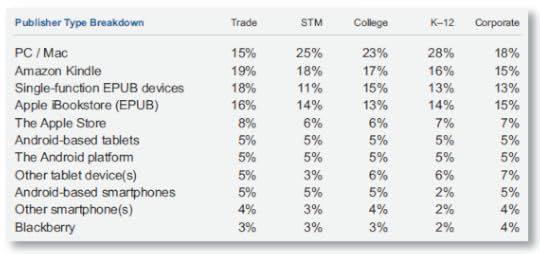

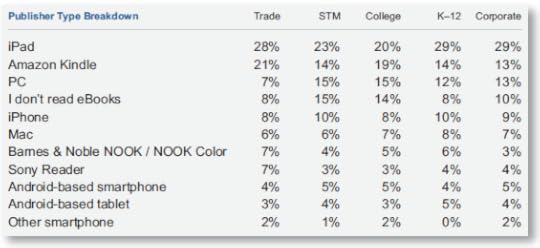

Question 8: What devices/platforms are you targeting with your eBooks?

Another interesting factoid is the battle between the Kindle format and ePub, with the latter emerging rapidly as a dominant target for eBook producers in the very near future. The chart above shows the devices and platforms eBook publishers are targeting, with the Kindle getting only 19% of the Trade market's focus while ePub makes up 34% (between the combined iBookstore and single-function devices capable of reading that format), making ePub the most heavily targeted platform. In other words, eBook publishers are looking to separate themselves from Amazon's proprietary platform, even though current sales don't justify it (see next chart below), and few (only 25%) have any strategy for moving to the ePub format. Meanwhile, the Android platform is too highly fragmented to be effective, and Blackberry has lost more ground than it is ever likely to make up, being all but out of the race at this point.

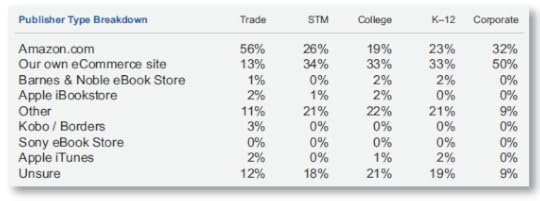

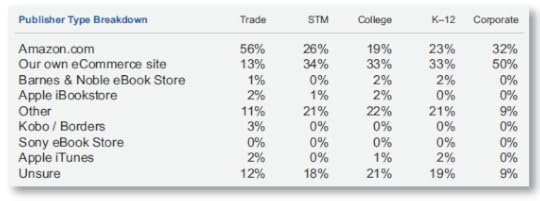

Question 10: Which channel produces the largest percentage of your eBook sales?

Overall Amazon produces 38% of eBook sales, but as you can see in the chart above, they account for 56% of Trade sales, compared to the next closest at 13% (a 43% margin), that second place being taken by a combined total of all individual publisher eCommerce sites as compared to Amazon alone (that's why they're called "Amazon"). Internal corporate sales are what have skewed the figure away from Amazon in the overall picture, which is why I'm posting up this additional breakdown, since Trade sales are what are really relevant to the average consumer and independent author. The educational and professional categories also cause a lot of wobble in the figures, since STM (Science, Technical & Medical) and College/K-12 text sales are generally derived from direct distribution via sales reps and conferences, as shown in the considerably higher percentages allotted to the "Other" and "Unsure" categories in these markets.

The big shocker here is how poorly Barnes & Noble are faring in the eBook battle, with a mere 1% of digital sales both overall and in Trade books alone. Given the fact that they have both brick-and-mortar outlets as well as a line of dedicated eReaders with their own integrated online bookstore, this is an appallingly bad showing. Even Apple have done better with a combined 3% share overall and 4% in Trade between iTunes and the iBookstore. Meanwhile, Sony has lost all traction as a source of digital literature whatsoever, with no reported sales at all!

However, I have to say that I'm a bit surprised at the number of publishers who are "Unsure" as to the source of their revenue. This is either a function of the somewhat poorly reported eBook sales stats, and/or the publishers' own uncertainty as to where their digital sales are coming from due to the lack of a well-developed internal eBook accounting infrastructure. This has been a problem for some time, although there is improvement in reporting, with Amazon in particular being fairly transparent to publishers about their eBook sales. 11% for "Other" is also a pretty substantial segment, since there aren't very many significant "others" at play aside from Google, who continue to surprise me by not meriting their own breakdown (are they really faring that poorly?). Most of the "Other" category is likely made up of aggregators such as Smashwords who have their own storefronts as well as distributing to other channels.

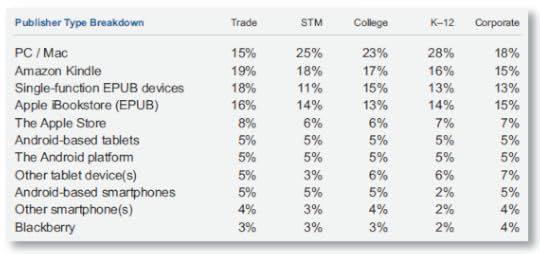

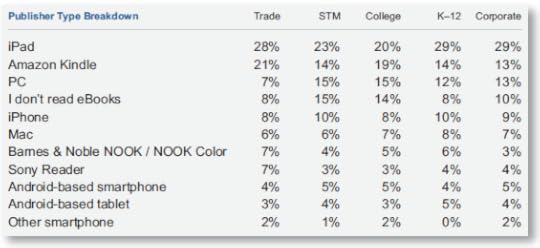

Question 20: Which of the following devices do you personally use to read eBooks?

Finally, while the views of traditional publishers as to their favored eReading device are far less relevant that that of actual eBook consumers, it is telling that the multimedia iPad is the preferred eReader over the dedicated Kindle device, even though most consumers say just the opposite, and as sales of the two eBook formats clearly show (mind you, the Kindle Fire was not yet out when the survey was taken). That an equal number of publishers prefer to read on a PC/Mac as they do a Kindle is highly questionable, and goes more to show their reluctance to support Amazon by claiming to like their device (even though there would be no eBook market without it). The breakdown above again shows that it is the non-Trade segments who are skewing these figures the most, which makes sense as a lot of professional and academic research is still done on personal computers rather than on personal reading devices.

However, the most relevant statistic is in the number of respondents who don't read eBooks at all. In the first Aptara survey of 2009 22% said they had never read an eBook, while two years later that number is down by half to 11% overall, and just 8% among Trade professionals, showing how fully the digital revolution has been embraced (or at least accepted). The final summation of the survey states the case quite clearly:

Click the image below for a high-rez version.

Foremost among them is the statistic given in the upper right of the infographic, showing that 62% of all publishers are now producing ebooks. Among trade publishers (i.e. non-corporate or educational), that number is 76%, with another 19% saying they have plans in place to begin ebook production. In the first Aptara survey of 2009 just 50% of trade publishers were producing digital editions. Only 6% now say they have no plans to do so.

Question 4: What is your organization's current involvement with eBooks?

Other highlights of the latest survey are that nearly one in five (18%) of eBook publishers generate more than 10% of their revenue from digital editions, although three times that many (57%) pull in less than 3% from eBooks, with 14% of publishers producing eBooks making nothing from their efforts thus far. This is a "strong statistic for an early-stage market" according to the survey findings, and shows that there is still a lot of room for growth.

Another interesting tidbit is that 10% of publishers intend to produce eBooks instead of print, while 85% plan to do both. Meanwhile, 37% now produce more than three-fourths of their titles as eBooks, with 32% converting less than one fourth of their output to digital. One stat not shown on the infographic is that two out of three publishers have yet to convert the majority of their backlist into eBooks, meaning there are a lot of older titles out there still waiting to be released as eBooks.

Amazon still holds the lion's share of the eBook market, but that share is shrinking as publishers begin to sell from their own e-commerce sites.

Question 8: What devices/platforms are you targeting with your eBooks?

Another interesting factoid is the battle between the Kindle format and ePub, with the latter emerging rapidly as a dominant target for eBook producers in the very near future. The chart above shows the devices and platforms eBook publishers are targeting, with the Kindle getting only 19% of the Trade market's focus while ePub makes up 34% (between the combined iBookstore and single-function devices capable of reading that format), making ePub the most heavily targeted platform. In other words, eBook publishers are looking to separate themselves from Amazon's proprietary platform, even though current sales don't justify it (see next chart below), and few (only 25%) have any strategy for moving to the ePub format. Meanwhile, the Android platform is too highly fragmented to be effective, and Blackberry has lost more ground than it is ever likely to make up, being all but out of the race at this point.

Question 10: Which channel produces the largest percentage of your eBook sales?

Overall Amazon produces 38% of eBook sales, but as you can see in the chart above, they account for 56% of Trade sales, compared to the next closest at 13% (a 43% margin), that second place being taken by a combined total of all individual publisher eCommerce sites as compared to Amazon alone (that's why they're called "Amazon"). Internal corporate sales are what have skewed the figure away from Amazon in the overall picture, which is why I'm posting up this additional breakdown, since Trade sales are what are really relevant to the average consumer and independent author. The educational and professional categories also cause a lot of wobble in the figures, since STM (Science, Technical & Medical) and College/K-12 text sales are generally derived from direct distribution via sales reps and conferences, as shown in the considerably higher percentages allotted to the "Other" and "Unsure" categories in these markets.

The big shocker here is how poorly Barnes & Noble are faring in the eBook battle, with a mere 1% of digital sales both overall and in Trade books alone. Given the fact that they have both brick-and-mortar outlets as well as a line of dedicated eReaders with their own integrated online bookstore, this is an appallingly bad showing. Even Apple have done better with a combined 3% share overall and 4% in Trade between iTunes and the iBookstore. Meanwhile, Sony has lost all traction as a source of digital literature whatsoever, with no reported sales at all!

However, I have to say that I'm a bit surprised at the number of publishers who are "Unsure" as to the source of their revenue. This is either a function of the somewhat poorly reported eBook sales stats, and/or the publishers' own uncertainty as to where their digital sales are coming from due to the lack of a well-developed internal eBook accounting infrastructure. This has been a problem for some time, although there is improvement in reporting, with Amazon in particular being fairly transparent to publishers about their eBook sales. 11% for "Other" is also a pretty substantial segment, since there aren't very many significant "others" at play aside from Google, who continue to surprise me by not meriting their own breakdown (are they really faring that poorly?). Most of the "Other" category is likely made up of aggregators such as Smashwords who have their own storefronts as well as distributing to other channels.

Question 20: Which of the following devices do you personally use to read eBooks?

Finally, while the views of traditional publishers as to their favored eReading device are far less relevant that that of actual eBook consumers, it is telling that the multimedia iPad is the preferred eReader over the dedicated Kindle device, even though most consumers say just the opposite, and as sales of the two eBook formats clearly show (mind you, the Kindle Fire was not yet out when the survey was taken). That an equal number of publishers prefer to read on a PC/Mac as they do a Kindle is highly questionable, and goes more to show their reluctance to support Amazon by claiming to like their device (even though there would be no eBook market without it). The breakdown above again shows that it is the non-Trade segments who are skewing these figures the most, which makes sense as a lot of professional and academic research is still done on personal computers rather than on personal reading devices.

However, the most relevant statistic is in the number of respondents who don't read eBooks at all. In the first Aptara survey of 2009 22% said they had never read an eBook, while two years later that number is down by half to 11% overall, and just 8% among Trade professionals, showing how fully the digital revolution has been embraced (or at least accepted). The final summation of the survey states the case quite clearly:

Publishers couldn't ask for a better position: the ground floor of an early-stage market experiencing exponential sales growth. The downside to being at the starting gate is the growing pains; the upside is the untapped revenue potential that lies ahead. Publishers still face distribution channel, quality, pricing, and DRM issues, but these concerns have gradually diminished over the past two years—a sign of an eBook market that is starting to mature.

Click the image below for a high-rez version.

Published on December 11, 2011 12:28

December 10, 2011

SOB On Kindle Lending Library

Ever since Amazon began lending ebooks as part of the Kindle Prime program there's been a lot of talk on the web (much of it negative) as to how - and if - authors would be compensated for these new library loans. Never mind that a large percentage of Kindle titles were already available for free library lending through Overdrive (a choice that publishers make for themselves when uploading titles to the Kindle platform), the fact that Amazon charges $79 per year for its Prime membership meant that authors (rightly) felt deserving of a share of that pie by way of royalties for the use of their product in what amounts to promotion of Amazon's Kindle line and a major offensive in Amazon's conquest of the ebook market.

The publishing world's response to this shot across the bow has been essentially to withdraw from the fight. Penguin infamously pulled all of its titles from library lending altogether, only to capitulate in part after a mass reaction from both press and public: their older titles are once again available via libraries, but new titles are not, and they're having nothing to do with the Kindle at all for the time being. The reaction has been only slightly less dramatic from the remaining players among the majors, but none of this seems to have phased Amazon in the least, or slowed sales of the revamped Kindle line, including the new Kindle Fire, which various estimates place somewhere between three and five million units. With each of those tablets including a free month of Amazon Prime, that's quite a few million free ebook loans pending for the month of December alone.

This week Amazon rolled out the fledgling Kindle Owner's Lending Library to independent authors who publish through Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP). The new program is called KDP Select, and Amazon is setting aside half a million dollars every month to pay authors royalties for titles that are borrowed by Kindle owners through the Prime membership program, with the entire monthly sum of $500,000 being divided out among all titles borrowed during each month. Within a day of launch over 37,000 titles were enrolled in the program. So I guess that answers all those authors' questions as to how they'll be compensated for ebook loans.

The caveat to this deal is that in order to enroll a title in the program it must be exclusive to Amazon for a period of at least 90 days, meaning the ebook cannot be available for sale on any other site or any format but the Kindle (although the print edition can still be sold elsewhere). Like many authors, I can afford to do this because the vast majority of my sales come from Amazon. I also have the added benefit of having a two-volume edition of The Saga of Beowulf available on other sites that does not fall under the non-compete clause by virtue of being listed on Amazon as separate entries from the Complete Edition, which is the one I have enrolled in the program. I'm always up for trying out a new experiment, and it will be interesting to see how this plays out.

So let's do some math. Amazon offers this example:

...if total borrows of all participating KDP titles are 100,000 in December and your book was borrowed 1,500 times, you will earn $7,500 in additional royalties from KDP Select in December.

In other words, 100,000 loans is one fifth of the $500,000 pot, allotting $5 to each book loan, times 1500 loans equals $7500. Of course, with 3-5 million new Kindle Fire owners each being given a free month of Prime, the number of loans is likely to be something closer to 10-20 times that given in the example, dividing the allotment down to around .25 to .50 cents each, and potentially much much less. With five million ebooks loaned the per-loan royalty would be a mere .05 cents each. So even at the incredibly unlikely rate of 1500 loans per month, you're still only looking at a total revenue of $75. And most books will only be loaned out a handful of times, if even that. Of course, it could go the other way and only a handful of titles will be borrowed, making the individual allotment much more impressive: a total of 10,000 loans for December, for example, would net each author $50 per loan. But I highly doubt that will happen.

The question of numbers is, of course, entirely conjectural. At best these are wild guesses. Even Amazon can't know fully what to expect, although I'm pretty certain they know what they're doing. And I have to give them kudos for putting up the money in the first place, particularly since the only way they can possibly make any profit here is by converting borrowers to buyers, which they must believe is a fairly solid possibility. The number of initial Prime users who opt to continue their enrollment at $79/year is certainly bound to be greater with this added bonus of a "free" ebook to read each month than it would be otherwise. And as we're already seeing an influx of titles to the program, it's obviously paying off in terms of having a lot of exclusive content to offer.

It's unlikely the "Big Six" will go for this, which is making Amazon the leader of the new independent revolution. They're clearly not courting the major publishers here, and frankly it looks more like all out war to me, to see who can command the largest market share on the other side of the digital divide (that is, in the post-print era that is coming). With titles like Water For Elephants (Algonquin Press) and The Hunger Games trilogy (Scholastic) enrolled in the program it's clear their strategy is to divide and conquer, courting the smaller presses while the major trades fall further and further behind. It's a battle that is only bound to get more vicious and ugly as time goes on. But so far, Amazon is winning.

Published on December 10, 2011 16:17

December 3, 2011

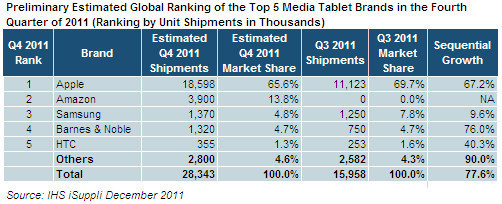

Projected Tablet Sales

The chart above shows the current (right) and projected (left) market shares for the various tablet devices out right now through the end of this year. Amazon, of course, had no tablet on the market in the 3rd quarter, but this projection estimates the Kindle Fire will gain 13.8% of tablet sales for the final quarter, putting Amazon in 2nd place, well behind Apple (who have a two year head start) but firmly ahead of everyone else, including Barnes & Noble, who have had a full year to gain traction with the Nook, but have failed to do so in any significant way.

Even though the NookColor has been priced at half the iPad's lowest price, B&N's lack of content support for both music and video, as well as a weak app environment, have hampered Nook adoption. This just goes to show how few people actually use multimedia devices for reading books: tablets are primarily a game platform, as evidenced by the top selling app charts. Comics are the only segment of the book trade making serious headway on color tablets, for obvious reasons.

Interestingly however, B&N are the only entry project not to lose market share through the holiday season (although they won't gain any either). Amazon's cannibalization will come primarily from Apple's share, with Samsung taking a heavy loss as well. Granted, these are only projections, but it's fairly clear than the Kindle Fire is the winner here: to claim 2nd place and close to 14% of any market in your first quarter of existence is a feat most products can only dream of.

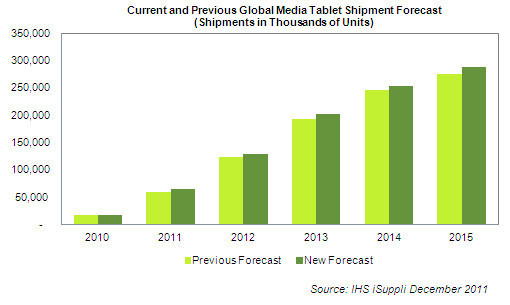

The chart below shows the newly revised tablet sales forecasts for the coming years. As you can clearly see, the figures have been revised upward as the tablet adoption trend is projected to continue unabated for at least another three or four years, during which time tablet technology will continue to improve at a rapid pace and prices will drop until they reach a plateau somewhere around 2015. Again, these are only guesstimates, but they're based on expected production orders from reliable sources in the business of knowing what's going on. What will really happen is anybody's guess.

Published on December 03, 2011 08:52

December 2, 2011

Tablet Display Resolution Soon To Increase

With pixel density set to multiply in the next generation of e-reading devices, several questions face today's ebook designers with regards to visual content. Much like the early days of video games, today's digital comics and illustrated novels face quick extinction as display technology outpaces the ability of content to keep up. By the time a fixed layout ebook is formatted and finalized today, tomorrow's devices will improve and render it outdated within a year of its release. This is true not only of the reading devices themselves - which have a virtually built in obsolescence date of twelve months between generation waves - but now for a particular segment of the content spectrum as well: any images formatted to render correctly on today's e-reading devices will be horribly outmoded by this time next year.

This may seem a bit extreme until you consider that an ebook cover image formatted to fill the screen of an iPad 2 at 132 pixels per inch will cover only half that space on the iPad 3's projected 264 ppi display. That is, given the same 9.7" display size, an image 768x1024 pixels in size will completely fill the screen of the iPad 2 today, but on next year's 2048x1536 iPad 3 display, that same cover image or illustration will leave over half the screen empty - or zoomed to twice its resolution, rendering it grainy and pixelated, just like ancient Space Invaders. Illustrations embedded amidst reflowable text will suddenly become swamped in a sea of words, their detail all but indistinguishable due to their smaller size.

And Apple isn't the only device platform planning a pixel explosion in the coming year: Android tablet manufacturers are said to be ramping up production of 1920x1200 ppi displays, many of them believed to be destined for Amazon's next gen full size tablets, which various reports place at either 8.9" or 10.1" (or both). This poses critical problems for graphic ebook designers. With these increased screen specs comes demand for higher resolution images, and with it increased file size. With Amazon enforcing a .15 cent surcharge per megabyte on ebook sales this is no small consideration for heavily illustrated works such as photo collections or cookbooks, not to mention comics and graphic novels. In order for an illustrated ebook created today to still be viewable with its same design layout on tomorrow's tablets images nearly twice their current standard size need to be embedded; otherwise we'll all be viewing mini-mebooks.

Tablet pixels-per-inch average set to increase in coming quarters

Published on December 02, 2011 07:14

December 1, 2011

2011 Book Sales Update

As you can see from the chart above, it's been another banner year for ebooks so far, with a 100.9% increase in sales over this time last year. Meanwhile, print books continue to decline, with adult mass market titles taking the biggest hit in a -54.3% nosedive. Overall book trade sales dropped by 6.45% over the prior year, showing that increased ebook sales are not making up entirely for lost print sales. This is due, of course, to the fact that digital editions are a fraction (less than half on average) than that of their respective print entries.

For a more in depth comparison of some key factors relating print to digital here is an infographic which lays out in visual terms such book related statistics as relative market share and growth of ebooks vs. print, the pros and cons of each in ecological terms (i.e. relative carbon emissions and deforestation), as well as the misperception of average production costs between the two mediums (it is at present vastly more expensive per unit to produce an ebook than a hardback, for example).

Most importantly, this is a trend that doesn't look as if it's likely to change anytime soon. With the tablet market riding a wave of rapid expansion and its supporting technological innovation experiencing a relentless momentum of improvement, digital will only continue to consume an ever larger share of the overall book and multimedia market. What this means for authors and publishers is a pivotal shift in our fundamental paradigm unlike anything that's happened since the Renaissance. We are witnessing nothing less than a revolution in the cultural history of our species. Historians will look back on these few years as a turning point, a dividing line that separates two epochs of our literary evolution. The first decade of the 21st century will be the last days that print books were the predominant mode of consuming literary content.

Published on December 01, 2011 18:16

November 26, 2011

Diatribe on "Book: A Futurist's Manifesto, Part 1"

As the title states, this "Book" from the O'Reilly collection is a compendium of dissertations covering some of the challenges and changes facing the publishing industry today, with commentary on how those changes might (or should) take place, ranging from overall conceptual shifts to specific issues of implementation.

The book itself was produced using (and as a test platform for) the new PressBooks utility, an online ebook creation and conversion tool that allows for outputting to multiple formats, including ePub, Kindle, HTML, InDesign-ready XML and print-ready PDF. While this efficient workflow is admirable in principle (and is discussed in both theory and detail in the book itself), the ebook editions I downloaded each suffer from some inconsistent (or just poor) formatting, broken external links, and at least one garbled graphic on the Kindle Fire (double tapping to zoom produced an image with full width but squashed to just a few pixels in height). I viewed the book in ePub format in iBooks (on the iPad2) and Adobe Digital Editions (PC), as well as Mobi format on both Kindle 3 and the Kindle Fire.

Currently the book contains only the first of three parts, with the next two said to be forthcoming as free "updates" for anyone who purchases part one. As each part is added the initial price will increase from its current $7.95, so getting in now guarantees the best value. However, you can also read the entire thing online for free. A print edition will be forthcoming once the book is finished.

Part 1: The Setup

As with most collections of essays, this one is a mixed bag, being aimed for the most part at medium to large scale publishing houses whose outmoded production model is currently in flux. While much of the content is of little use to indie authors and other content creators, the overall discussion of the changing landscape of publishing is informative and enlightening (if often pedantic and heavy-handed).

The opening essay in particular - "Context, Not Container" - while conceptually interesting, is nearly unreadable due to the utter tedium of its writing style and lack of a clearly stated thesis. It's a typically long-winded academic dissertation aimed at an unspecified target audience, filled with repetitive arguments and undefined terminology, which could have been said more clearly in a fraction of the space. Ultimately, it's as if we're reading an extract from a conversation for which we are not privy to the beginning, and in which a large number of us ultimately do not belong, since the subject applies only to a subset of content creators (a distinction made far more relevant and interesting in the final essay of this section by Craig Mod).

The overall concept of a broader content ecosystem that exists beyond the confines of its container makes great sense and is highly relevant to the future evolution of electronic texts; but the essay seems to place the content author at the bottom of an infinite pile, forgetting that without an artist's vision there can be no art at all. While the elements of the author's palette now extend far beyond the borders of the visible canvas, one must remember that these are all tools for the artist to use, and constitute a broader new "container," rather than the lack of one. The interconnected world is the new container.

To my mind this is an underlying flaw in the focus of the whole collection, which is aimed not so much at what can be done by content creators, but how e-production houses and aggregators can gain the most by implementing a workflow which creates the greatest efficiency and widest possible distribution to all platforms. Certainly this is a valid goal for all content, and is particularly relevant with respect to content that reflows easily, as much content does. But one of the foremost challenges facing content creators on the "bleeding edge" is in the areas where this is either undesirable, or simply not possible without destroying what the content is (i.e. as a work of art); some content simply requires a fixed state to retain its essential nature. Rethinking the container (or the canvas, as I prefer to think of it) is a fundamental shift which will be far more difficult for some than others.

However, that fundamental shift in perception is one we all will need to make, from seeing ebooks as a re-creation of what print books have been, to what ebooks can be in their new environment: the interconnected, interactive world without borders. The idea of an "infinite canvas" that stretches out endlessly in all directions from the e-reader viewport was a great revelation. Imagine, for example, the screen as a magnifying glass positioned over a giant globe - like Google Earth - that can travel in any direction endlessly, both horizontally and vertically, as well as in and out, with links like transportation hubs between distant points (this might be a great concept for an adventure novel, for example, with directional travel "paths" like an Indiana Jones vignette rather than mono-directional page turns). And those dimensions of travel are not limited in time or space: the reader's own input and interaction can effect the outcome, and alter the content itself by, for example, adding commentary or participating in an interconnected network of readers who each input information in a Wikipedia-like way. It's in ways like this that the "container" has been shattered.

These are just examples of what an ebook can be. But it's not necessarily what they should be (certainly not in all cases, at any rate). Just because the borders of the canvas can be transcended doesn't mean they must be. The iPad, for example, is a device with a specific dimension and resolution, a canvas with a frame if you will, and that in itself is a medium many artists will make great art on (and are with fixed layout epubs), entirely within those boundaries. Just because you can morph the Mona Lisa's nose doesn't make it better art than what daVinci created. And I can't imagine he would appreciate it much in any case, or think it an improvement.

So even though the lid is off, there must still be a "box" where the core content resides. Otherwise, there is no longer an author or artist, and the readers themselves become the content creators, a conceit which is flawed in its very nature, since there is no longer a place for individual authors and artists in that world, and content without a guiding creative force can only become dissipated and, ultimately, forgotten. Great works are created by great minds, not by common consensus or collating the voices of the multitudes. Art by committee is not art but socialism. By the laws of the bell chart this can only result in reduction to the average.

As for the remainder of the essays in this section of the book, most of them were only relevant to large production houses facing a major restructuring of their workflow in the digital age. There are chapters covering topics from aggregated distribution to the history of metadata and the usual concerns with DRM. Interesting, and useful to know, but nothing that hasn't been written and discussed elsewhere already.

Of most value and interest to my mind (as an author and independent publisher) were Liza Daly's essay on 'What We Can Do with "Books",' which discusses the malleable nature of the digital medium and how interactive elements can give readers a chance to participate and explore a more immersive text in a real and focused way. The idea of a book as a living document, for example, that can be updated automatically in revised editions like software upgrades is intriguing. This very book is an example of that, with additions coming later this year. I recently read about an author who is selling the first chapter of her book for .99 cents, with additional chapters to be added as completed for no additional charge, simply by updating the retailer-hosted file. This not only gives her an income during the writing process (sort of an advance for the self-pub ebook era), but also allows her readers to offer feedback that she can incorporate into the story as it progresses. That's very much the idea I had in mind as I've posted up the pages and completed chapters of my current Ring Saga project for readers to peruse (albeit without any real feedback aside from friends so far, so at this point it's pretty much a failed experiment, but it may yet grow as time goes on).

Very much related to this is Craig Mod's insightful analysis of the "post-artifact" landscape of content creation. As mentioned earlier, I found this of particular value, with its discussion of the more direct interaction that can now be had between the author and the reader (theoretically at least, although he mentions more successful examples than mine), due to the narrowing and overlap of creation and distribution phases of content creation itself. The book is worth purchasing (or reading online at any rate) for this essay alone. It is a well-crafted piece of analysis with clearly defined concepts, into which a lot of thought and originality has gone. Would that all the essays included were as well written.

The overall impression the "Book" gives is not just of an industry in turmoil, but of a cultural icon and symbol of human progress undergoing a fundamental change. And that says a lot about who we are, and where we're going.

Book Rating: 3/5

#bookreview #ebook #eprdctn #selfpub #indieauthor

Published on November 26, 2011 11:50

November 25, 2011

SVG Text in iBooks Fixed Layout

Here's a really cool video from those awesome eBookNinjas, showing some crazy sweet stuff you can do with SVG text in the iBooks fixed layout format. This is a children's picture book their e-production company eBookArchitects has put together (kudos to Bridget!), and I have to say it really excites me about the possibilities for more advanced graphic novels.

Being able to wrap and warp text while still having it remain interactive for functions such as highlighting and dictionaries - or the read-aloud feature displayed here - is a really critical step in creating complex illustrated books that can retain the elements that make ebooks so awesome in the first place. I've been following these guys for awhile now, as well as many others working on these problems, and eBookArchitects are definitely one of the leaders in this field. So if you've got an ebook project that requires complex formatting, you really need look no further.

Being able to wrap and warp text while still having it remain interactive for functions such as highlighting and dictionaries - or the read-aloud feature displayed here - is a really critical step in creating complex illustrated books that can retain the elements that make ebooks so awesome in the first place. I've been following these guys for awhile now, as well as many others working on these problems, and eBookArchitects are definitely one of the leaders in this field. So if you've got an ebook project that requires complex formatting, you really need look no further.

Published on November 25, 2011 11:28

November 23, 2011

Mirasol Color Display Goes On Sale

As I mentioned yesterday, Qualcomm debuted its new full color Mirasol e-paper display on a 5.7" Android tablet, with a 30-frame-per-second refresh rate for smooth scrolling and video. That tablet went on sale today.

The Kyobo eReader is now shipping in Korea where the book retailer Kyobo is based. Retailing at around $300, the device features a 1024x768 capacitive touch screen with front-lit LEDs for illuminated reading in dim light. The reader sports a 1Ghz processor running Android 2.3, and is WiFi only. No mention was made of its memory specs, but battery life is estimated at about 3 weeks, which is impressive. That factor alone should make it catch the attention of western device retailers. If user reviews are good expect to see next year's incarnation of the Kindle Touch in color.

For anyone who's interested, Mirasol's technology works essentially by refracting ambient light through tiny prism-like mirrors which rotate or "flip" magnetically to display a given color. Although these reflective particles are microscopic, they require a small amount of space to spin about, an "air gap" between the glass and surface. This is why I laughed so hard the other day when Barnes & Noble touted their new Nook Tablet as the first display without an air gap, as if that was somehow a major innovation.

The video below gives a brief demonstration of the Kyobo screen's refresh rate and color capabilities. To me it still looks a bit pastel, but it's certainly got speed and color. Color intensity and contrast will improve with time. I would like to have seen the screen demonstrated in a darker room to see how the LED illumination looks, but since it's only available in Korea at present it's a mute point for me anyway.

Published on November 23, 2011 09:46

November 22, 2011

The Hobbit Issued as Enhanced eBook

One of the foremost prototypical fantasy novels of the modern era has been treated to a new edition for the digital age. J.R.R. Tolkien's perennial 1937 children's classic The Hobbit was released today as an enhanced edition for iBooks and Kindle, complete with 28 full color interactive images and four audio recordings of the author reading (and singing!) excerpts from the story.

The four recordings are:

"Chip the Glasses and Crack the Plates!" (sung)

"Far Over the Misty Mountains Cold"

"Roast Mutton"

"Riddles In The Dark"

New high resolution images of Tolkien's illustrations are included for the first time, which can be zoomed to full size by double tapping. Many of the original black and white drawings also now have alternate overlays colored by H. E. Riddett, which can be accessed and dismissed with a single tap or swipe. Among these are some unused drawings and several images of Tolkien's first handwritten manuscripts, complete with doodles and margin notes.

In addition, a new introduction by Christopher Tolkien examines the writing of the book and discusses many of the sketches and drawings that are included.

NOTE: KINDLE BUYERS BEWARE!!!

While this new edition has been released for both the Kindle and iBooks (and apparently soon the Nook), the interactive content is currently only available in iBooks. A notice beneath the book cover image on the Kindle edition page states that "Audio/Video" content is available only on iOS devices, but whether this refers to the interactive illustrations or just the audio is unclear. I'm guessing that the latter is the case, as it would be difficult to justify selling this edition as an "enhanced" ebook without at least one of the added features included. Even to release it as a semi-crippled version of what it was intended to be is pretty sketchy.

It is also uncertain if this is just a temporary glitch in the KF8 rollout, or if the enhanced features will be forthcoming for the Kindle edition at some point down the road. I would presume they will be for the reason I just mentioned (some serious backlash is certain to ensue otherwise), but since it isn't mentioned there's no way to be sure. Consequently I bought the iBooks edition, which works better on the larger screen anyway.

Published on November 22, 2011 16:40