R. Scot Johns's Blog, page 16

January 23, 2012

How to Create Fixed-Layout iBooks, Part 2

Today we'll be tearing apart an ePub file to look at what's inside, and then starting at the top and working our way down the list of contents one by one. If you haven't downloaded the free template file yet, then do so now, as I'll be using it to describe the contents of a standard iBooks file. You can also download my Ring Saga sample chapter and have a look inside if you want to see a somewhat more complex file. It's encryption-free, so you can open it up and look at all the content.

NOTE: For anyone who tried to download the template or sample chapter earlier but got corrupt files, the problem has been fixed. My web host apparently altered their file requirements to all lower case without informing me (or maybe I just missed the memo), and also lowered the file size limit.

SECOND NOTE: I meant to write and post this yesterday, but all my free time was taken up in dealing with corrupt file issues, which led to hosting server issues, which led to searching for a new host, which led to domain transfer matters, which led to further delays, which required finding a temporary file host in the meantime. So I apologize for the delay, but it couldn't really be helped. Consequently, this post will be shorter than I'd planned, and we won't get to the real nitty-gritty until tomorrow, when (hopefully) I find the time.

OPENING THE FILE

As I mentioned previously, an iBooks file is just a slightly modified .epub, which itself is just a .zip archive with the extension changed. Consequently, you can open an .epub the same way you open any .zip file. You can either change the .epub extension back to .zip if you want to, or you can just right-click on the .epub and select "Extract" or "Open with" whatever zip program you use. I recommend 7-Zip, which lets you modify the contents of an .epub without changing the extension or extracting the files. You can also just drag and drop new files into it, and delete ones that are in there. Other compression programs might do this too, but I haven't tried them, so you're on your own there.

The other program you'll want is Notepad++, or something similar which has numbered lines and search/replace functions. Don't use Windows Notepad as it doesn't have these features and will totally garble your files. You can use any webpage builder you might have, such as Dreamweaver or whatnot, but since you'll be opening and closing it a lot and often, you'll want something that loads and opens files quickly. Whichever editor you choose, be sure to add it as the default editor in 7-Zip (Tools / Options / Editor) so that you can right-click and select "edit" to open compressed files in the editor without extracting the files.

THE FILE STRUCTURE

When you look inside the template, what you'll see at the root level is one file and two folders (whose contents I'll also disclose here for a complete overview of where we're going:

mimetype

/META-INF/

container.xml

com.apple.ibooks.display-options.xml

/OEBPS/

/css/

page02.css

styles.css

/fonts/

Storybook.ttf

/images/

bookpage.jpg

cover.jpg

content.opf

cover.xhtml

page01.xhtml

page02.xhtml

toc.ncx

This is the basic ePub file structure, all of which must be in an iBooks file (except for the custom font), although the names of the content files themselves can be unique to your book project, with the exception of the META-INF folder and its contents, which must be named exactly as shown. And of course there will likely be a whole lot of additional files in there before you're done, possibly including a few varieties not listed here. But more on that later. First things first...

THE MIMETYPE FILE

The mimetype file tells the reading system what type of file it's looking at. If you right-click and select "edit" to open this file you'll see a single line of text:

This tells the device's operating system that the file is an epub/zip archive, which tells it a lot about it's structure that the contents are compressed. You can create this file from scratch in your editor, but you can also just use this one, as they're mostly all the same. The new .ibooks files have a new mimetype:

which I imagine tells the iBooks application to apply a whole new set of rules to the contents. As an experiment I changed my Ring Saga mimetype to this and loaded it into iBooks. The file opened with the super-cool new hardback cover, but there wasn't anything else inside, so I've got some work to do yet in figuring that out. I'll let you know when I work it out. But from this we can discern that one of those new rules is that .ibooks files get the nice new glossy hardback cover!

If you choose to create your own mimetype file there are three stipulations you must observe:

The best way to achieve these requirements is to create a zip archive with just the mimetype file in it, using no compression when you add it, and then to add in all the other files later, with compression. Encryption is an issue I won't even begin to get into here.

THE CONTAINER FILE

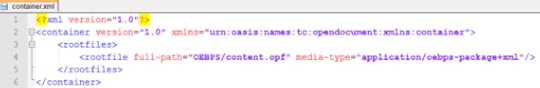

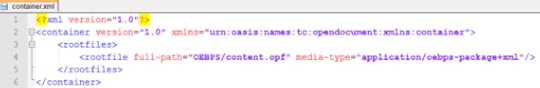

Like the mimetype file, the container.xml must be named exactly that. In addition, it must be in a folder named META-INF, so that the OS knows where to find it. The sole function of the container file is to tell the device where to find the .opf (which seems a somewhat redundant step if you ask me). Looking inside the container.xml file here is what you'll see:

This is the first of many files where we need to explain some things to the computer so it understands what we're saying and what to do with the information.

The first two lines are declarations, stating what language we're speaking and giving a namespace reference (xmlns), which is a specific set of operating rules, more or less:

Within this is contained the rootfile path, which as I said tells the system where to look for the file that contains a listing of the ebook's contents, and what type of file that is:

Looking at our file structure above, you'll see that the content.opf is in the OEBPS folder, just like our path data says here. This file can actually be anywhere and named anything you like, so long as you say so here. The media-type, however, must read exactly as given, since it describes the target's file type, which is an Open eBook Publication Structure (OEBPS) package written in eXtensible Markup Language (XML). We'll talk about the .opf itself later. Be sure to include both the </rootfiles> and </container> closing tags as shown in the image.

THE COM.APPLE FILE

This is a file completely unique to Apple's iBooks, which consists of a set of display options that tell iOS devices how to present the content. I've included all of the triggers that I am aware of in the template file, along with some notes (in green) giving the allowable choices. However, the only ones required are these:

The platform name "*" means all devices, with the only two other options being either "iphone" for handheld devices only (including the ipod touch) or "ipad" for tablet only content. This allows you to specify different display options for different platforms. I'll give an example using the remaining options:

So here we have one set of options that apply to all platforms and three that apply only to the ipad. This would create an ebook with a fixed-layout and custom fonts on all devices, but which would only open as a spread on the ipad, and only in landscape mode, and which would have its interactive content disabled on handheld devices (since "true" is only chosen for the iPad and "false" is the default).

Most of these have "true/false" choices, with "false" as the default. Taking them one by one:

"fixed-layout" [true/false] - this must be set to "true" for any of what we're about to do to work. This is the tag that tells iBooks to use fixed-layout properties, and so is required.

"specified-fonts" [true/false] - you can embed your own fonts into your ebook if you want something beyond what's offered on the ipad, although you must have the appropriate rights to do so. More on this when we get into the fonts folder.

"open-to-spread" [true/false] - this tells iBooks whether or not to open to the full two-page spread or to show the starting page at its largest possible size and force the rest beyond the frame. This is set to "false" by default which does not mean you won't see some (or even all) of the two-page spread, depending on the size of your book's pages, particularly in landscape mode. But with this option set to "false" the start page will take up either the full height or width of the screen, with the opposing page flowing off the screen. Set to "true" you'll see the full two-page spread no matter which way you turn the device. Which brings us to...

"orientation-lock" [portrait-only/landscape-only/none] - this allows you to choose just one orientation in which your ebook can be viewed, which can be beneficial if your book has odd sized pages (such as a photo album with pages wider than they are tall), or you're aiming for handheld-only devices only where you might want single pages viewed in portrait mode only.

"interactive" [true/false] - this is a new option which allows scripted content to be added and made active. Again, "false" is the default setting, so you must tell it if you're adding scripted content. This does not apply to anything that's inherent in iBooks itself, such as pinch-and-zoom or tapping and swiping, but only to more complex content such as finger-painting or movable images.

As mentioned, aside from the "fixed-layout" option itself, you only need to add in others if they apply to your book. Just leave out the rest. But this gives you some leverage in how your work is presented to the world, which can make a lot of difference.

So that's it for the META-INF folder. There are other files that can find there way in here, but none you'll need to mess with, as they mainly involve encryption controls. Some ebooks will put in manifest and metadata files here, but those are best left in the .opf where they belong (and are required). These are all you'll need for now, and that's as far as we'll be going for the moment.

NEXT UP: Creating Your Content

NOTE: For anyone who tried to download the template or sample chapter earlier but got corrupt files, the problem has been fixed. My web host apparently altered their file requirements to all lower case without informing me (or maybe I just missed the memo), and also lowered the file size limit.

SECOND NOTE: I meant to write and post this yesterday, but all my free time was taken up in dealing with corrupt file issues, which led to hosting server issues, which led to searching for a new host, which led to domain transfer matters, which led to further delays, which required finding a temporary file host in the meantime. So I apologize for the delay, but it couldn't really be helped. Consequently, this post will be shorter than I'd planned, and we won't get to the real nitty-gritty until tomorrow, when (hopefully) I find the time.

OPENING THE FILE

As I mentioned previously, an iBooks file is just a slightly modified .epub, which itself is just a .zip archive with the extension changed. Consequently, you can open an .epub the same way you open any .zip file. You can either change the .epub extension back to .zip if you want to, or you can just right-click on the .epub and select "Extract" or "Open with" whatever zip program you use. I recommend 7-Zip, which lets you modify the contents of an .epub without changing the extension or extracting the files. You can also just drag and drop new files into it, and delete ones that are in there. Other compression programs might do this too, but I haven't tried them, so you're on your own there.

The other program you'll want is Notepad++, or something similar which has numbered lines and search/replace functions. Don't use Windows Notepad as it doesn't have these features and will totally garble your files. You can use any webpage builder you might have, such as Dreamweaver or whatnot, but since you'll be opening and closing it a lot and often, you'll want something that loads and opens files quickly. Whichever editor you choose, be sure to add it as the default editor in 7-Zip (Tools / Options / Editor) so that you can right-click and select "edit" to open compressed files in the editor without extracting the files.

THE FILE STRUCTURE

When you look inside the template, what you'll see at the root level is one file and two folders (whose contents I'll also disclose here for a complete overview of where we're going:

mimetype

/META-INF/

container.xml

com.apple.ibooks.display-options.xml

/OEBPS/

/css/

page02.css

styles.css

/fonts/

Storybook.ttf

/images/

bookpage.jpg

cover.jpg

content.opf

cover.xhtml

page01.xhtml

page02.xhtml

toc.ncx

This is the basic ePub file structure, all of which must be in an iBooks file (except for the custom font), although the names of the content files themselves can be unique to your book project, with the exception of the META-INF folder and its contents, which must be named exactly as shown. And of course there will likely be a whole lot of additional files in there before you're done, possibly including a few varieties not listed here. But more on that later. First things first...

THE MIMETYPE FILE

The mimetype file tells the reading system what type of file it's looking at. If you right-click and select "edit" to open this file you'll see a single line of text:

application/epub+zip

This tells the device's operating system that the file is an epub/zip archive, which tells it a lot about it's structure that the contents are compressed. You can create this file from scratch in your editor, but you can also just use this one, as they're mostly all the same. The new .ibooks files have a new mimetype:

application/x-ibooks+zip

which I imagine tells the iBooks application to apply a whole new set of rules to the contents. As an experiment I changed my Ring Saga mimetype to this and loaded it into iBooks. The file opened with the super-cool new hardback cover, but there wasn't anything else inside, so I've got some work to do yet in figuring that out. I'll let you know when I work it out. But from this we can discern that one of those new rules is that .ibooks files get the nice new glossy hardback cover!

If you choose to create your own mimetype file there are three stipulations you must observe:

1. The mimetype file must not be compressed or encrypted

2. There must be nothing else in the file but the one line of text

3. It must be the first file in the zip archive

The best way to achieve these requirements is to create a zip archive with just the mimetype file in it, using no compression when you add it, and then to add in all the other files later, with compression. Encryption is an issue I won't even begin to get into here.

THE CONTAINER FILE

Like the mimetype file, the container.xml must be named exactly that. In addition, it must be in a folder named META-INF, so that the OS knows where to find it. The sole function of the container file is to tell the device where to find the .opf (which seems a somewhat redundant step if you ask me). Looking inside the container.xml file here is what you'll see:

This is the first of many files where we need to explain some things to the computer so it understands what we're saying and what to do with the information.

The first two lines are declarations, stating what language we're speaking and giving a namespace reference (xmlns), which is a specific set of operating rules, more or less:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<container version=1.0" xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:opendocument:xmlns:container">

Within this is contained the rootfile path, which as I said tells the system where to look for the file that contains a listing of the ebook's contents, and what type of file that is:

<rootfile full-path="OEBPS/content.opf" media-type="application/oebps-package+xml"/>

Looking at our file structure above, you'll see that the content.opf is in the OEBPS folder, just like our path data says here. This file can actually be anywhere and named anything you like, so long as you say so here. The media-type, however, must read exactly as given, since it describes the target's file type, which is an Open eBook Publication Structure (OEBPS) package written in eXtensible Markup Language (XML). We'll talk about the .opf itself later. Be sure to include both the </rootfiles> and </container> closing tags as shown in the image.

THE COM.APPLE FILE

This is a file completely unique to Apple's iBooks, which consists of a set of display options that tell iOS devices how to present the content. I've included all of the triggers that I am aware of in the template file, along with some notes (in green) giving the allowable choices. However, the only ones required are these:

<display_options>

<platform name="*">

<option name="fixed-layout">true</option>

</platform>

</display_options>

The platform name "*" means all devices, with the only two other options being either "iphone" for handheld devices only (including the ipod touch) or "ipad" for tablet only content. This allows you to specify different display options for different platforms. I'll give an example using the remaining options:

<display_options>

<platform name="*">

<option name="fixed-layout">true</option>

<option name="specified-fonts">true</option>

</platform>

<platform name="ipad">

<option name="open-to-spread">true</option>

<option name="orientation-lock">landscape-only"</option>

<option name="interactive">true</option>

</platform>

</display_options>

So here we have one set of options that apply to all platforms and three that apply only to the ipad. This would create an ebook with a fixed-layout and custom fonts on all devices, but which would only open as a spread on the ipad, and only in landscape mode, and which would have its interactive content disabled on handheld devices (since "true" is only chosen for the iPad and "false" is the default).

Most of these have "true/false" choices, with "false" as the default. Taking them one by one:

"fixed-layout" [true/false] - this must be set to "true" for any of what we're about to do to work. This is the tag that tells iBooks to use fixed-layout properties, and so is required.

"specified-fonts" [true/false] - you can embed your own fonts into your ebook if you want something beyond what's offered on the ipad, although you must have the appropriate rights to do so. More on this when we get into the fonts folder.

"open-to-spread" [true/false] - this tells iBooks whether or not to open to the full two-page spread or to show the starting page at its largest possible size and force the rest beyond the frame. This is set to "false" by default which does not mean you won't see some (or even all) of the two-page spread, depending on the size of your book's pages, particularly in landscape mode. But with this option set to "false" the start page will take up either the full height or width of the screen, with the opposing page flowing off the screen. Set to "true" you'll see the full two-page spread no matter which way you turn the device. Which brings us to...

"orientation-lock" [portrait-only/landscape-only/none] - this allows you to choose just one orientation in which your ebook can be viewed, which can be beneficial if your book has odd sized pages (such as a photo album with pages wider than they are tall), or you're aiming for handheld-only devices only where you might want single pages viewed in portrait mode only.

"interactive" [true/false] - this is a new option which allows scripted content to be added and made active. Again, "false" is the default setting, so you must tell it if you're adding scripted content. This does not apply to anything that's inherent in iBooks itself, such as pinch-and-zoom or tapping and swiping, but only to more complex content such as finger-painting or movable images.

As mentioned, aside from the "fixed-layout" option itself, you only need to add in others if they apply to your book. Just leave out the rest. But this gives you some leverage in how your work is presented to the world, which can make a lot of difference.

So that's it for the META-INF folder. There are other files that can find there way in here, but none you'll need to mess with, as they mainly involve encryption controls. Some ebooks will put in manifest and metadata files here, but those are best left in the .opf where they belong (and are required). These are all you'll need for now, and that's as far as we'll be going for the moment.

NEXT UP: Creating Your Content

Published on January 23, 2012 23:47

January 22, 2012

Call for Beta Readers! Rhinegold, Chapter 1 - iBooks Edition

For anyone with an iPad who is interested, you can now download the opening chapter of my illustrated novel project The Curse of the Rhinegold in fixed layout format for iBooks. The file is available for free for a limited time, so get your copy now before it's gone.

Chapter 1 is 22 pages long, plus full jacket cover, title page, and an afterword addressed to beta readers. The file is 24.2 megabytes, optimized for the highest quality graphics, with images at 1788 x 1118 pixels (just under 2 million pixels each) to future proof them against increased screen resolution in the coming months. This project is an experiment in creating a full color, full bleed illustrated fantasy novel for a older audience (i.e. it is not a children's picture book, although young adults have read and enjoyed it so far). You can learn more about it on the Fantasy Castle Books website, or just download it and have a look. It won't cost you anything but time.

As with the initial PDF file, I'm extending the beta reader offer to this new iBooks edition. To anyone who sends in a review or critical comments on this chapter I will send a limited edition autographed chapbook of this section, as well as the next chapter in iBooks format as soon as it's complete. The second and subsequent chapters will not be made available online, and will only be free to those who have reviewed the earlier sections. For each chapter you critique you will receive the next one free. For those who send in comments or reviews on all five chapters of Book One, you will earn a signed print edition of the final published book, as well as the finished ebook in the format of your choice.

For more details see the final pages of the sample chapter download.

Published on January 22, 2012 22:04

January 21, 2012

How to Create Fixed-Layout iBooks, Part 1

With the new iBooks Author application only available for Mac users, the vast majority of us are left to fend for ourselves when it comes to making fixed-layout ebooks. This is probably just as well if you're at all like me and prefer to do things yourself and have complete control over the end result, although it's not all that difficult if you take it step by step and have a fair amount of patience (and good attention to details). While iBooks Author looks like it has some nice features, it requires a trade off in rights to the final product that I'm not willing to make just yet, particularly when there are other options available.

For the past few months I've been working out how to build fixed layout ebooks for the iBooks platform in order to replicate the layout I've created for my illustrated novel project, The Ring Saga. Since my intention is to produce the four-volume series as a full-color print edition in the standard 5.5" x 8.5" "perfect bound" format as well as in various digital editions, I needed to produce the art and page layouts in the print edition aspect ratio and reproduce them as ebooks from that. For a full color, heavily illustrated project such as this, the iBooks fixed layout format for the iPad was the obvious place to start when it came to creating the digital editions.

WHAT IS FIXED-LAYOUT?

The essence of a fixed-layout ebook, from a practical point of view, is that - as the name implies - it allows for the creation/replication of exact graphic design layout which the reader cannot alter, as opposed to the standard "reflowable" formats which allow the end user to change the font and text size, for example. This is incompatible with highly formatted layouts such as graphic novels and magazines, and simply unacceptable to many graphic design departments who've spent decades (if not centuries) refining the arts of composition, typography, and illustration.

Fixed-layout also allows for "full-bleed" (edge-to-edge) artwork and the layering of multiple elements on top of one another, placed precisely using XML, a relatively basic subset of HTML, and CSS for styling. You don't need to know very much of this code to make an ebook work, but of course the more you do know, the more complex and stylized your formatting can be. iBooks also allows both javascript and canvas for incorporating interactive elements, although this requires a far more extensive knowledge of those programming languages than the average author generally has. I'll include a few examples of scripting code that you can copy and customize for your own use as we go along.

Apple's fixed-layout iBooks format is an ePub file with a few additional options and requirements that make it only viewable on iOS devices, but also incorporates all the nice features inherent in the iBooks app, such as pinch and zoom, animated page turns, and automatic reorientation. Both Barnes & Noble's NookColor/Tablet and Amazon's Kindle Fire have fixed-layout formats, but B&N have thus far been very restrictive in allowing anyone but trade publishers to use their format, and Amazon have only just recently released the specs for their new KF8 format, which is still a work in progress, with the comics portion still forthcoming. And of course they both only have 7" screens, which is too small to adequately display more than a single book page at a time. This is not prohibitive, but it isn't ideal either, particularly if you want to reproduce the two-page layout of a print edition.

THE TEMPLATE

My intention here is to share enough of what I've learned to aid you in producing your own fixed layout iBooks from scratch, without the need of an app or conversion service to do the work for you. To make this easier, I've created a sample template file that you can download and use as the starting point for your own projects. In a series of subsequent posts I will break this file down into its component parts and explain them as plainly as possible, giving examples of the various code elements and describing the options available for each.

RESOURCES

There are some good resources available to assist in learning the fixed layout format, but none of them discuss in much detail the formatting options allowed or the reasons for them. I'll try to do that here. But I won't go into HTML or CSS beyond the necessary basics, and a few specifics that apply to iBooks, since the rest is common web code known to most, or easily learned elsewhere. In addition, I won't be discussing anything that applies solely to standard "reflowable" ebooks, or how to format your manuscript with headings and sections and the like. This tutorial is to help you create an illustrated ebook with "live" text, such as a children's book or graphic novel, for the iBooks platform. I plan to do subsequent tutorials for the Kindle Fire's KF8 format, and the Color Nook tablets, if interest warrants.

Before we begin, here are some useful ePub resources you might consult:

International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF) - complete ePub specs reference

MobileRead ePub Wiki - discussion and examples of the ePub file structure

ePub: The Language of eBooks - A Primer - guest post by Iris Febres explaining ePub

Build a Digital Book With ePub - tutorial by Liza Daly of ThreePress

- outdated and overly complicated, but informative

JediSaber's ePub Tutorial - A bit antiquated, but filled with useful information

When it comes to fixed-layout iBooks specifically, the resources are more scarce:

iBookstore Asset Guide (PDF) - Apple's own documentation, which includes a very sketchy section on creating fixed-layout ebooks

How To Make An iPad Photo Book - the only online tutorial I've found on the subject, with just enough to get you started

Liz Castro has a book out about making ePub files, with a fixed-layout supplement available for five bucks more. Also be sure to pick up her Read Aloud mini-guide, if only so you can take a look at her Aesop's Fables sample.

Other than that, there isn't much information available on how to produce high quality iBooks in this format. I'll cover the essentials, but knowing more about the underlying ePub format is recommended if you really plan to get your hands dirty. To that end, there's nowhere better to go than the IDPF site, where you can read through the entire code specification top to bottom. It's pretty dry reading and hard going at times, but quite enlightening nonetheless.

NEXT UP: The File Structure

Published on January 21, 2012 22:29

January 20, 2012

iBooks Author Update

So my initial reaction to the release of iBooks Author yesterday was essentially one of frustration. What at first appeared to be a reasonably decent - even exciting - application for creating ebooks for the iBooks platform was quickly rendered mute by its virtual unavailability to the vast majority of computer users, including me. So utterly idiotic was Apple's decision to make this a Mac-only app that it completely overshadowed all other considerations at the time. It just seemed so plainly obvious to me when advance reports began to leak of Apple's intention to seriously compete in the ebook market that the only logical move that made any sense at all to me would be to open up the iBooks platform to a wider audience of content creators as Amazon have done so successfully.

But Apple's intention was, in fact, to make content creators come to them, and not the other way around at all. The astounding stupidity of this is just mind-boggling beyond belief. To think you have that kind of clout when you hold less than 5% of the market you're aiming at is one of the most misguided business notions I have ever heard (and there has certainly been plenty of stupidity in the business world of late). To create a product almost no one can use and expect it to somehow alter the fabric of reality is just complete insanity.

What I hadn't really given due consideration to was the fine print in the end user licensing agreement, which stipulates quite clearly that any content created using iBooks Author can only be sold via the iBookstore: that is, not on Smashwords, not on your own website, not anywhere else...ever. Like many (if not most) potential users I more or less blew this off. Since an iBook can only be read on an iOS device it didn't seem to make all that much difference, as the iBookstore is obviously the best place to sell that content. After all, you can purchase Kindle ebooks all over the place, but the place most readers purchase them is right on their Kindle. Why not the same for iBooks? The difference, of course, is that Amazon does not require you to sell Kindle ebooks on the Kindle, or even on Amazon at all, and aside from the exclusive Library Lending program, you're free to sell them anywhere.

But Apple are taking a different tack entirely, one that might be called totalitarian by some, and just plain dumb by any moderately educated business analyst. Perhaps they think that just because they've made the application free people will rush out and buy their relatively overpriced hardware in droves so that they can use it. And maybe they're right. But I highly doubt it.

The more real and serious implications of this move were pointed out quite clearly in a post by Dan Wineman over at Venomous Porridge yesterday, which boil down to the fact that Apple are in essence claiming sole rights to all output from its software, not just to the use of the software itself. This has vast legal implications for creative content beyond just this instance, which could set a precedent for digital content that might have lasting repercussions that are difficult to reverse. More importantly, it has immediate and practical implications for authors who want to retain full rights and control of their work. If you create content via iBooks Author then Apple gain sole and final distribution rights to that work. One can only imagine the lawsuits just waiting in the wings the first time an iBooks release becomes a million seller and that author wants to add the book to other platforms, or sign with a traditional publisher for worldwide publication rights.

As I mentioned yesterday, I had ordered a Mac Mini in order to upload my content to the iBookstore. Today I cancelled that order. Not only that, but I've started writing a tutorial on how to create your own fixed layout iBooks using a template I have uploaded to my website. I'll post the first part tomorrow, and continue so long as there is interest.

Published on January 20, 2012 18:47

January 19, 2012

iBooks Author: Awesome & Disappointing

According to many news headlines, Apple "made their bid today" for a larger presence in the self-publishing space with the introduction of iBooks Author, a Mac app that lets content creators do just that: create rich, interactive ebooks with a simple drag-and-drop interface. The new tool was launched at a New York press conference this morning, along with iBooks 2 and an upgraded iTunes U, both of which now feature enhanced textbook sections, as Apple follow up on Steve Jobs' desire to reinvent the education space with digital content.

But while iBooks Author does indeed look promising, it leaves a great deal to be desired, both in terms of functionality and accessibility, and one must question whether it can ever hope to achieve what these latest headlines are touting. While the Author app will likely prove more than adequate for the majority of book content creators, it's essentially a dot-to-dot, fill-in-the-blanks production tool, with templates that are bound to make a lot of its output look alike. For textbooks and most standard fiction this is fine, but it eliminates much of the creativity involved in making content with complex layouts. Based on the promotional images and video released today, it appears to handle full-page images with overlaid text to some degree, and the image word wrap function is impressive. But the font selections are limited to those available on the iPad, and interactivity is little more than simple pinch and zoom and standard tap functions that trigger events like photo galleries and videos. Rotating 3D models are interesting, in a limited way, but I'm curious to see how the glossary feature works, and there's a lot that can be done with layered images and some scripting if you know how (java and html code are allowed, but not something many authors are familiar with). But of course, I can't really know how well it works, since I'm unable to use it. Which brings me to my main point, concerning accessibility.

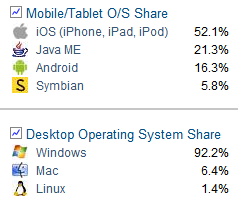

Source: netmarketshare.com

The primary mark against iBooks Author as a useful tool for content creators in general, and self-published authors specifically, is its immensely restricted availability: it's only being released through the Mac app store, for OS X Lion only (not even Apple's own iOS), leaving 93.6% of the world's computer users out of luck. Had Apple at least made it available as an iPad app they could have targeted well over half of the tablet market, particularly given that their Pages word processing app is already on there, providing authors with all the tools they might need to create rich content for the iBookstore right on their iPads. But with only 6.4% of computer users (and thus, one must infer, authors) having access to a Mac, one can hardly call this a "bid to own publishing's future," as today's L.A. Times business section put it. The figures are even more skewed in the education field that Apple seems to be aiming for here, with less than 5% of schools and offices using Macs.

Still, it's a really sweet looking piece of software which is bound to lure in at least a few new Mac OS users. I can say that with some certainty because I bought my first Mac today, in the form of a Mac Mini, which is about the cheapest you can get into an OS X product. I had been contemplating this for some time, not as a jump to Mac, or even because of this new app, but simply as the only practical means of uploading my content to the iBookstore when it's ready, since iTunes Connect is also only available for the Mac. People complain about the proprietary nature of Amazon's Kindle format (with some justification), but Apple is truly even worse, since you can at least read Kindle ebooks on other hardware via apps, and Mac users can create and upload Kindle content. Not so with Apple. With them it's Mac or nothing. Which is why they have just 4% of the ebook market currently, and will never come close to competing with Amazon in terms of publishing. They may sell a lot of tablets, but they'll never sell very many ebooks until they open up the platform to all of the people who produce them.

You can learn more about this new app and view a promo video on the iBooks Author page.

Published on January 19, 2012 19:54

January 13, 2012

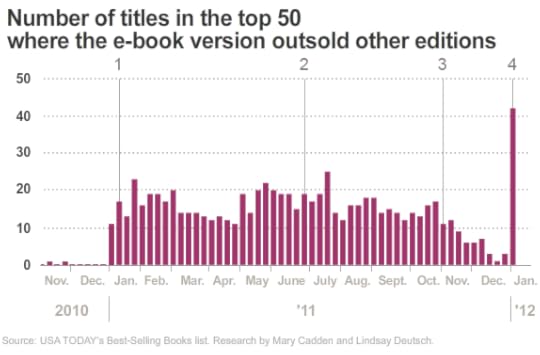

Ebooks Take Over USA Today Top 50

This is part of a new graphic put out by USA Today this week, showing the rise of ebook sales up the bestseller charts. The full chart shows dates running back to July 2009 when Amazon's ebook sales were first added to the bestseller charts, but entries in the top fifty were essentially non-existent until last January, so I haven't included that portion of the chart here. However, you can click though on the image to view it over at USA Today.

The only important points missing from the truncated chart above are the inclusion of Barnes & Noble ebook sales in December of 2009, and Sony's in February 2010, plus the singular event when I, Sniper by Stephen Hunter became the first ebook to crack the top 50, coming in at #48 on January 1st, 2010.

Points noted on the chart above include:

First ebooks crack the Top 10 as post-holiday sales explode

Kobo ebook sales added (no significant impact in the U.S.)

Ebook sales begin to dip as holiday shoppers buy print books as gifts instead (and a whole lot of e-reading devices)

Ebooks outsell print editions for every title in the Top 10, including 42 of the top 50 best selling titles

As with this week last year, ebook sales have increased exponentially after a holiday season in which literally millions of new e-reading devices were received as gifts. Forrester Research estimates that Amazon has sold some five million Kindle Fires since its launch in mid November, with Barnes & Noble adding two million new Nook Tablets to the fray. Apple, meanwhile, sent out around forty million iPads last year, although it's difficult to determine how many will be used to read ebooks.

With digital editions overtaking print for the top spots on the bestseller charts, print is destined to decline even faster in the coming year, as print sales have largely been held up by the million-selling titles. Initial figures from the U.S. Census Bureau show that print sales fell by 9% in 2011, due in part to the demise of Borders, who sold their final book in September. But if post-holiday ebook sales remain as stable this year as they did throughout the past year, ebooks might well achieve market dominance this year.

Published on January 13, 2012 09:26

January 12, 2012

Amazon Reveals Library Loan Royalties

In a somewhat unprecedented move, Amazon has publicly revealed some very specific financial figures in a press release today. These concern the Kindle Library Lending Program and its fledgling counterpart, Kindle Select, in which authors are given a share of a half million dollar pot each month for every ebook they have enrolled in the program that is borrowed, based on the total number of loans that month.

December was the inaugural launch of the Kindle Select program, and until today no one knew how much to expect each loan to earn, as there were too many unknown variables, such as how many total loans there would be, how many titles would be enrolled in the program, and how those loans would be distributed among the current offerings. Would the top ten ebooks get the lion's share? Would everybody get a little? And how would anybody really know if Amazon never offered up the numbers? I floated some estimates in a post last month, but made no predictions. Amazon used the figure of 100,000 ebooks borrowed for their example.

The actual figure was 295,000. Thus, dividing the $500,000 pot by 295,000 loans results in a payout of $1.70 per ebook borrowed. And thus ends the speculation.

Now let me put that in perspective a bit. On a $2.99 ebook with a 70% royalty, an author receives $2.09 for each book sold, minus the download fee, which is .10 cents per megabyte. My "Complete Edition" ebook is 2.31 Mb, so .35 cents is taken out, leaving me with $1.74 - only four cents more than I now make when the book is loaned instead of purchased. This effectively increases my revenue, and brings new readers to my work. It's a win-win situation.

Let me put it in even more perspective. On a .99 cent book with a 35% royalty (the only royalty allowed for that price point), the author receives .35 cents. Total. But for each time that same ebook was borrowed in December, they will receive... yep, $1.70. More than the cost of the ebook. Nearly five times the royalty paid out for a sale of that same ebook. Thus, rather than having to sell 100 books you can now loan out just 20 and make the same amount of money.

Now let me put this in another light. The average royalty for a traditionally published author is 10% on hardback sales up to 250,000 copies (12-15% for higher sales volume), and 6% for paperbacks. Minus 15% taken by the agent. Thus, for a $25 hardback the author receives $2.13 per copy sold ($2.50 minus 15%), but only when and if their advance has earned out (a $20,000 advance, for example, would require sales of over 9390 copies to start paying royalties; until then the author receives nothing beyond the advance). For a hardback book sold to a library to loan out innumerable times, that author receives... yep, $2.13. Total. Regardless of how many times that book is taped back together and checked out of that library. And that hardback is only out for a short period of time, giving them just a small window of opportunity to make that advance. After the paperback comes out our same author receives an average royalty of 6%, which on the average $6.50 title is just .39 cents... $1.31 less than our ebook author has just received for loaning out their title via Amazon.

For anyone that doesn't understand what Amazon is doing here, let me spell it out: they are buying authors. They are drawing authors in and stocking their shelves with exclusive content by paying out the best royalties in the business, giving them the best terms, the best tools, and the best distribution platform you could ever want: instant access, everywhere. Because of this, 75,000 titles are now enrolled in the Kindle Select program. Exclusively. Meaning, you can't get those ebooks elsewhere. That is a requirement of the program.

And, just to make it more enticing, they have now just sweetened the deal: $200,000 more has been added to the pot for January, bringing the total to $700,000 that will go out to authors enrolled in the Kindle loan program this month. That would bring the royalty for those same 295,000 borrows to $2.38 instead of $1.70, more than the average traditionally published authors earns for selling hardbacks.

Of course, the more hardbacks an author sells, the more they earn. In this case, the more ebooks are loaned out the less each one earns. But for those that are loaned out in large numbers, the paycheck can be quite nice. Today's press release offered a few examples:

The top ten borrowed authors earned a total of $70,000 in December

Paranormal romance author Carolyn McCray received $8250

Romance writer Amber Scott's paycheck will be $7650

16 year old children's book author Rachel Yu will get $6200

Plus, sales for KDP Select authors have risen by an average of 26%

Other publishers and book distributors are going to have a really tough time competing with this kind of stuff. Complain all you like about the megalithic empire that is Amazon, I defy you to name a single other entity that has done so much to get so many books in front of so many readers, and pay those authors for it.

Oh, and by the way, my payday will come to just a little over twenty dollars.

Published on January 12, 2012 19:09

January 11, 2012

KF8 & KindleGen2 Released

Amazon today finally released to the public the long awaited and much anticipated tools to produce ebooks in the new KF8 format, including a new Kindle Previewer, an upgrade to KindleGen 2, and a plug-in for InDesign that allows for KF8 export (minus a few of the enhanced features, such as Text Pop Ups and Panel Views). Links to each of these are provided below, as well as the associated documentation.

In addition, Amazon sent out a new survey to self-published authors today, which seeks to gather data on what they are looking for in a self-publishing service, what their past experiences have been, if any, with their own or other services, and asks for ratings of Amazon's offerings in this area if any have been used. So collectively it appears as if Amazon are poising themselves to actively champion the self-publishing cause, via a new enhanced format, new devices on which to distribute them, the tools with which to create them, and information on how best to serve the needs of content creators. I have, of course, completed the survey, with ample notes and commentary.

With the new format specs and tools having just come out today, it will take me a few days to sort through it all and test it out. I have nearly completed an iBooks fixed layout edition of my opening sample chapter, which I plan to upload early next week for your perusal, and as soon as I work out how to create an accurate KF8 version I'll upload that as well. Meanwhile, here are the links Amazon provided today, should you wish to go cavorting through some ebook code yourself...

Kindle Format 8 Home Page - now includes links to the Previewer, KindleGen, and Guidelines

KindleGen2 - Comand-line application for creating KF8/Mobi ebooks from X/HTML and EPUB

Kindle Previewer - Graphic interface for the viewing, converting, and validation of KF8 ebooks

Kindle Previewer documentation (PDF) - just in case you want to read it first

Kindle Publishing Guidelines (PDF) - newly revised to include the KF8 format, with complete instructions on how to self-publish on Amazon

Kindle InDesign Plugin (Beta) - includes KF8 support, minus enhanced features mentioned above, but with updates to be forthcoming

Kindle Plugin for Adobe InDesign documentation (PDF) - again, for perusing first to see if it's what you need

Simplified Format Guide - A step-by-step online reference for building KF8 ebooks from Word documents (the link to an HTML-based version isn't currently working)

More info will be posted as I have it.

Published on January 11, 2012 21:18

January 10, 2012

The Growing Value of Reader Reviews

Carrying on from where I left off yesterday, it has become increasingly apparent that with the mass influx of new reading material on the market the average reader is rapidly becoming overwhelmed with choices. In a sea of three million new titles sorting out what's good from what is utter dreck is getting harder every day. This is the primary reason people tend to read the same few authors and titles that everyone else is reading, which is to say, what's currently being promoted heavily by the major trades via talk shows and magazine ads. It helps us sort through the ever-growing pile of work of only minor value or peripheral interest, works for which in business terms the potential return does not justify a large investment to promote. Consequently, more mainstream books are promoted, and works of "lesser interest" are left behind to wallow in obscurity.

Of course, many of those "minor" works are truly great. Not every great book has a huge potential audience: some genres and subjects are by their very nature smaller than others. But that does not imply no good work can be written on those subjects. Young adult vampire novels, for example, have a very large audience, while stories about, say, Sumerian mythological deities do not. That does not imply that all vampire novels are inherently excellent, and all (if there are any) newly written fiction concerning ancient Mesopotamian myths and legends are inherently bad. The latter will just never be read (or likely even published) because no viable publisher would ever put much effort into promoting it (unless it's been turned into a modern-day archaeological thriller by a major author, that is). Because of this, subjects of significant literary interest have become very narrow and overburdened with replicated content (much of it utter rubbish), while subjects with just as much potential literary value have been ignored and overlooked, even while some of it is extremely good (and often more imaginative).

This has been the state of affairs for much of the modern era, with a few narrow subjects such as crime thrillers and horror stories being promoted with lavish budgets and high praise from mainstream book reviewers while the vast majority of subject categories go unnoticed, aside from a handful of literary book reviewers who might take a fancy to a work of a more quirky nature. There has been, for example, an earnest and heartfelt effort to support small press publishers who produce works of social or personal drama, with the occasional Oprah selection of the month gaining incandescent notoriety. In general, though, the bestseller lists are populated with the same old dreck just written with different words.

That condition has been exacerbated by the literal flood of unfiltered material now inundating the world through self-publishing venues, much of which is drivel, but some among it bound to be quite good, if not astounding (while also odd, unconventional, or geared toward a rather narrow audience). Until now, one could place at least some minor faith in the traditional system which gleans (however inefficiently) through a virtual mountain of submissions to filter out the "best" of what's been written (define "best" how you like, but for the major trades this means "most potential return on investment" since they are, after all, a business). The enforcement of that filter has now been removed (or bypassed, as it were), and a veritable landslide of literary muck has been unleashed upon an unsuspecting public.

The question then, is how do we now discern what is of value when the traditional system has been usurped? Of course, the traditional system is still there, so one answer is simply to keep doing what we've always done, and read what everyone else is reading, which is to say, what the six main publishers promote. Eventually all this other stuff will go away if no one pays it any mind, and we can go about our business knowing greater minds are deciding what is best for us in a comfortably Brave New World (Huxley postulated a world in which "the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance,"* where the general populace, unable to distinguish literary value for themselves, are reduced to passively accepting what is given them) [*Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves To Death, 1985]. Sadly, that is not too far from the truth today.

But there is an alternative. There is another system already in place that can help us with our burden. It is built upon that most sacred and cherished of all commodities we possess: our own opinions, and those of others like ourselves. This system is made functional and relevant via the vast network of reader reviews on public sites like Goodreads, LibraryThing, book review blogs, and most importantly, online book retailers such as Amazon, whose reader review and recommendation engine is unparalleled. In a world where every reader rated and/or reviewed each book that they've read no good book would go undiscovered. Even in a year with over three million titles published, very few of them will go entirely unread. But a great many of them will remain unreviewed, leaving the rest of us to wonder as to their quality, and casually pass them by.

The value of a book review is difficult to understate (and here I should specify that I mean reviews by readers unaffiliated with, and thus uninfluenced by, the publishing world, which casts a wide shadow over the media empires they control, including periodicals and TV stations). Even a simple one-to-five star rating tells the next potential reader much, particularly when it's an average based on a larger number of ratings. It also helps the author quite considerably in determining how their writing is received, and thus in trying to decide whether or not to bother writing another. A book that has no stars and no reviews is a book that few will ever read. It's an unknown quantity, an unnecessary risk in a world of opportunity, a gamble with those two other great commodities most of us have in short supply: our time and our money. But a minute spent rating a book that you've just read can save another reader (or yourself when selecting a book that others have rated and reviewed) a week or more of wasted time reading something that should never have been released in the first place, self-published or otherwise.

The days of benevolent gatekeepers looking out for our literary welfare are long gone. Regardless of whether it's independent or traditional, there is no one now evaluating the actual merit of what is being published but ourselves. Trade publishers tend to look at monetary rather than literary value, and self-published works are released regardless of value. Any given book published today can span the gamut of value, both monetary and literary. There is no real way to know unless someone has actually read the book and made the effort to give it an honest review.

And lest you think perhaps nobody pays attention to reader reviews, let me offer this bit of wisdom from personal experience: when Amazon recently added U.S. reviews to their U.K. site, my sales multiplied virtually overnight. No one in the U.K. had bothered to add a single review or rating to my debut novel, even though I'd sold well over a hundred copies there last year. With my U.S. reviews now available on the U.K. site my sales increased sevenfold, and I am currently on track to sell 780 copies this year just in the U.K. alone. Of course, some of that increase is likely due to holiday Kindle gifts that would have occurred regardless, but the effect was immediate and obvious when the reviews first appeared: seeing the increase in my sales report is what caused me to go looking at my book page on Amazon UK in the first place, to see if they had put the book on sale or something. They hadn't, but by adding the reviews they were helping to promote it in a very significant way.

So please, for your own sake, and the sake of every dedicated reader out there, take two minutes to rate each book you read this year, so that all of us can gain a better sense of what is out there worth our time. Better, take ten minutes and write a short review, describing what you liked or disliked, and why. This is particularly important for books with few or no reviews, as your opinion will carry a lot of weight with future viewers of that page. That being said, the opposite is true: if there are already over a hundred reviews don't bother adding your own as it will only be drowned out by the cacophony of voices, and clearly one more opinion is not needed. Certainly write one if you feel you have something of value to add to the conversation. But one more review of The Hunger Games won't convince anybody one way or the other, so save that for the fan sites. Instead, spend your effort posting your reviews of lesser read material. Maybe you'll discover the next great work and start a literary landslide.

P.S. To all the book review bloggers out there, my heartfelt thanks and keep up the good work. You're serving a critical social function that's becoming more important every day.

Published on January 10, 2012 14:55

January 8, 2012

Book Publication Statistics 2002-2010

Just ten years ago, in 2002, a total of 247,777 new books were published in the U.S. That figure was well over double the 104,124 titles published nine years earlier in 1993. A virtual literary boom one might say. Until one compares the statistics of today.

According to the running tally over at Worldometers, 23,653 books have been published worldwide thus far, in just the first 7 days of this year. In the U.S. alone total book publications for 2011 are estimated to have reached a staggering 3,092,740, according to Bowker's latest ISBN registration data. And that's just for titles with official ISBNs: a large percentage of self-published titles released via Amazon and Barnes & Noble (among others) are never assigned an ISBN, and thus are not tracked by Bowker or included in these figures. Meanwhile, aggregators such as Smashwords hand out ISBNs like Halloween candy to anyone that wants one: Smashwords alone produced 92,500 titles last year, up from 28,800 in 2010.

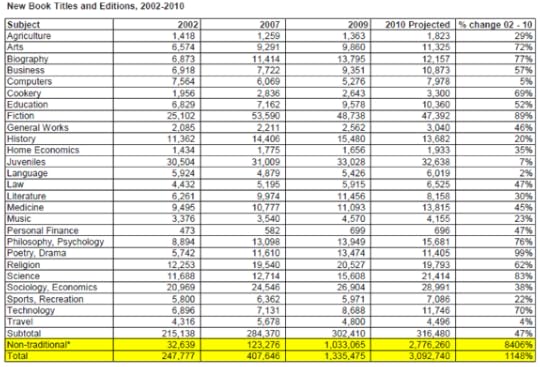

*Non-traditional consists largely of reprints, often public domain, and other titles printed on-demand.

The chart above is taken from the latest Bowker stats, which I've truncated from a larger version showing every year from 2002-2010 (available in pdf here) to highlight a few major points along the way. From 2002 to 2006 book production was fairly flat, remaining below 300,000 titles released each year. But in 2007, the year the first Kindle was released, new book titles jumped to 407,646, skyrocketing within two years to well over a million for the first time, and nearly tripling again just a year after that, bringing us to our current state of affairs: a market literally awash in literary matter. Thus, in just a single decade the number of books produced has increased by 1148%, most of it in just the last two years.

But even more telling is the second line from the bottom on the chart, which shows the number of "non-traditional" books produced, a figure that has leaped exponentially from just 32,639 titles released independently ten years ago to a mind-boggling 2,776,260 last year - an 8406% increase! According to Bowker's note, while many of these are public domain and back-list titles being hauled out in new editions (mainly in ebook format to take advantage of the Kindle/iPad boom), a great many are new self-published works being released for the first time via ebook or print-on-demand services such as CreateSpace and Lightning Source. If you compare these numbers with the total figures for each year (or the subtotal on the line above) you'll see that they make up the lion's share of growth within the industry: traditional print accounted for only 316,480 titles released last year (just 47% growth over 2002), compared to 2.7 million non-traditional titles.

Of course, these are unit figures, not sales statistics. While traditional print publishing is in decline (see my last post for stats on that), it still accounts for a large majority of book industry revenues. But that is changing rapidly as well. If each non-traditional title published last years sells on average just five copies each, that's nearly 14 million books sold, which is nothing to scoff at. And that is something Amazon clearly understands: they don't care who wrote them or produced them or who gets the royalty check...it could be one publisher or half a million different ones, it's all the same to them. A million candles burning steadily make a great deal of light, while the scattered illumination of random bonfires burning here and there cast fleeting brilliance that soon fades.

And that's something career authors also understand. The retirement fund won't come for most of us from selling millions of a single title or from small advances that won't ever pay out, but from slow and steady sales on a growing catalog of backlist titles you control and a fan base that will read each new book you put out. Looking at the numbers from this chart would seem to suggest the plight of independent authors is hopeless as their small output is swallowed up by an ever-growing sea of titles readers have to choose from. But in fact, just the opposite is true, because ten years ago the hope most authors had of being read was even less. It's estimated that the odds of getting published via the traditional submission route are less than 1% (the average literary agency receives 150-200 queries a day, follows up on less than 50, reads no more than the first three pages of most, and accepts no more than one per agent per week to represent, of which a good agent can sell 1 in 4, meaning the average agent sells less than twelve manuscripts to publishers each year). That leaves roughly 99.5% of manuscripts to rot away in the slush pile, unread.

But America is now the great slush pile, and the reader is the literary agent who buys or passes on a manuscript. Traditional publishers are no longer the arbiters of literary opinion, as the end user has the final say, literally, via online book reviews and ratings. I had originally intended to title this post "The Growing Value of Book Reviews" ... or, "The Increasing Importance of Reader Opinions" or some such, and talk about how the end consumer has now become the great literary filter of our culture. How at last it is the readers who decide what books are worthy of their time and attention (and their hard earned pay). How every author has just as much opportunity to reach an audience as any other, and will succeed or fail based solely on the merit of their work. But I'll save that for another day, as this post has gone on long enough, and I've got another book (or two) to write.

Published on January 08, 2012 17:12