R. Scot Johns's Blog, page 12

May 25, 2012

Self-Publishing Statistics

Two sources of statistics appeared this week that provide some insight into the overall success rate of self-published authors. Both provide some Infographics to illustrate their findings, so I'll embed those below. Unfortunately, neither provide particularly rosy or optimistic outlooks for the average author, even as the self-pub movement expands rapidly and ebook adoption explodes.

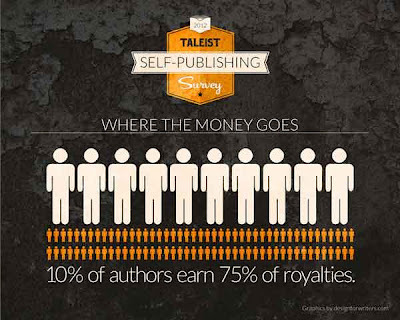

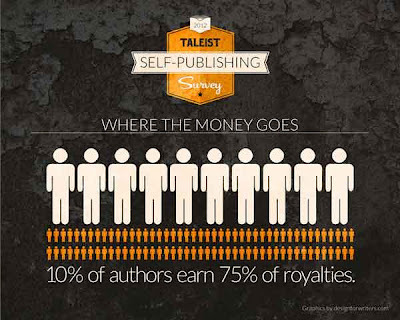

The first of these was a survey by Taleist, an Australian publisher/author services provider, who compiled responses to 61 questions from 1007 self-published authors. The report, titled Not a Gold Rush, found among other things that 10% of self-pubbed authors reap 75% of the rewards.

This is hardly surprising, and not altogether different than the traditional publishing route, and I would hazard a guess that 10% is being generous. If, for example, one of those 1007 authors happened to be John Locke the statistics might look very different. 1007 is a very small sample for a field in which 2.75 million books were self-published in 2010 alone. The fact is that the vast majority of those likely sold only a handful of copies, while a handful of authors sold the lion's share, making the ratio something closer to 5% of authors earn 90% of the royalties.

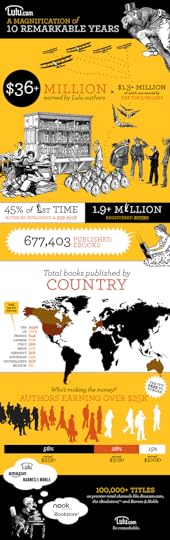

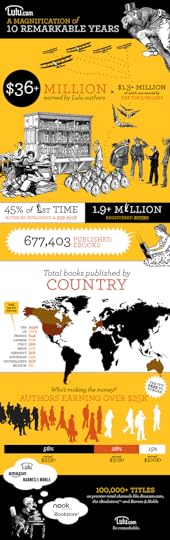

You can see this at work in the Infographic provided by Lulu.com, who are ostensibly celebrating "10 remarkable years" of success for self-published authors by proudly proclaiming that Lulu authors have earned $36 million during that time. They also go on to state that $1.3 million of that went to just five sellers (though not necessarily for just five books, I would point out), leaving $34.7 million for the remaining sellers to divvy up. But with a total of 1,441,000 books published during that time in just the top ten countries, the average total per title royalty is less than $25 ($36 million / 1,441,000 books = $24.98). And that's including the $1.3 million that those top five authors earned. This means that the vast majority of titles likely brought in less than ten or fifteen bucks total for their labors. And Lulu are celebrating this as an achievement!

To add more clouds to this already hazy forecast, Lulu's graphic confusingly provides a breakdown that makes it appear as if 56% of their authors are earning over $56k, when in fact the breakdown only applies to the authors making over that amount, so that it should read "Of authors earning over $25k, 56% earned $25k+..." Of course, they neglect to mention what percentage of their total authorship that represents, but I doubt it's anything like the Taleist's 10%.

If that were the case, then 75% of the $36 million in total earnings would be $27 million, leaving only $9 mil to divide among the remaining 90% of authors. Assuming an even distribution of books among those authors, that would leave a pool of 1,296,900 books to share 9 million bucks, for an average income of just $6.94 per book for the bottom 90%, while the top 10% earn an average of $187.37 per title, which is a damned far cry from $25k. What we're looking at is something more like 1% earned over $25k, while 99% earned next to nothing.

By comparison, Taleist found that half of their respondents brought in less than $500 last year from selling their wares, while the average income was $10,000. Again, this shows how skewed the numbers are toward the top few authors, with just those top 10% of respondents (97 out of 1007) saying that they make enough to live off their book sales alone. Meanwhile, 25% said they did not earn enough to cover the cost of producing their book. 53% had published for the first time in 2011, producing 2.8 books on average during the year, while another 20% debuted in 2010.

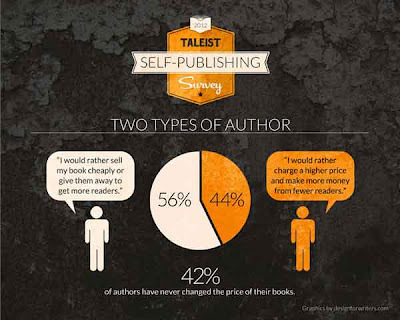

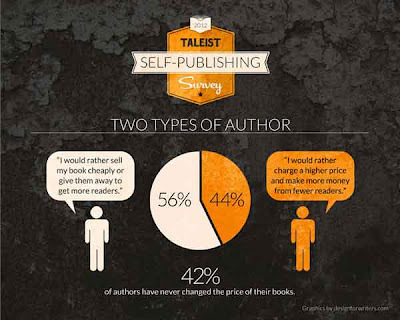

Another interesting statistic is this division in the pricing strategy of self-pubbed authors, where somewhat more than half (56%) prefer the volume sales model while the remaining minority (of 44%) think selling at a higher price is the way to go. Unfortunately, the survey did not elaborate on these points, which would have been highly enlightening, since there are many reasons for (and against) both views. It would be useful to know, for example, which of these models was the more successful, and if a higher retail price with fewer sales equated to more or less income, and more or less satisfied readers, with higher or lower average reader ratings.

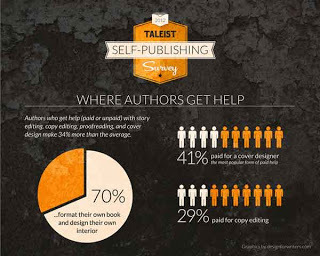

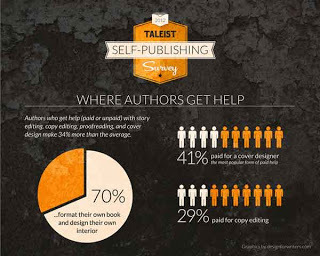

And finally, the Taleist report concluded that authors who got outside help with issues such as editing and cover design earned 34% more than the average, although 70% of respondents did not do so. Apparently more authors feel that books are judged more by their cover than their content, as 41% invested in a professional cover design, while only 29% shelled out for copy editing.

Surveys such as this are only snapshots of a segment of the industry, but they can shed some light on what is happening and how to make the best of it. You can buy the full report on Amazon for five bucks.

The first of these was a survey by Taleist, an Australian publisher/author services provider, who compiled responses to 61 questions from 1007 self-published authors. The report, titled Not a Gold Rush, found among other things that 10% of self-pubbed authors reap 75% of the rewards.

This is hardly surprising, and not altogether different than the traditional publishing route, and I would hazard a guess that 10% is being generous. If, for example, one of those 1007 authors happened to be John Locke the statistics might look very different. 1007 is a very small sample for a field in which 2.75 million books were self-published in 2010 alone. The fact is that the vast majority of those likely sold only a handful of copies, while a handful of authors sold the lion's share, making the ratio something closer to 5% of authors earn 90% of the royalties.

You can see this at work in the Infographic provided by Lulu.com, who are ostensibly celebrating "10 remarkable years" of success for self-published authors by proudly proclaiming that Lulu authors have earned $36 million during that time. They also go on to state that $1.3 million of that went to just five sellers (though not necessarily for just five books, I would point out), leaving $34.7 million for the remaining sellers to divvy up. But with a total of 1,441,000 books published during that time in just the top ten countries, the average total per title royalty is less than $25 ($36 million / 1,441,000 books = $24.98). And that's including the $1.3 million that those top five authors earned. This means that the vast majority of titles likely brought in less than ten or fifteen bucks total for their labors. And Lulu are celebrating this as an achievement!

To add more clouds to this already hazy forecast, Lulu's graphic confusingly provides a breakdown that makes it appear as if 56% of their authors are earning over $56k, when in fact the breakdown only applies to the authors making over that amount, so that it should read "Of authors earning over $25k, 56% earned $25k+..." Of course, they neglect to mention what percentage of their total authorship that represents, but I doubt it's anything like the Taleist's 10%.

If that were the case, then 75% of the $36 million in total earnings would be $27 million, leaving only $9 mil to divide among the remaining 90% of authors. Assuming an even distribution of books among those authors, that would leave a pool of 1,296,900 books to share 9 million bucks, for an average income of just $6.94 per book for the bottom 90%, while the top 10% earn an average of $187.37 per title, which is a damned far cry from $25k. What we're looking at is something more like 1% earned over $25k, while 99% earned next to nothing.

By comparison, Taleist found that half of their respondents brought in less than $500 last year from selling their wares, while the average income was $10,000. Again, this shows how skewed the numbers are toward the top few authors, with just those top 10% of respondents (97 out of 1007) saying that they make enough to live off their book sales alone. Meanwhile, 25% said they did not earn enough to cover the cost of producing their book. 53% had published for the first time in 2011, producing 2.8 books on average during the year, while another 20% debuted in 2010.

Another interesting statistic is this division in the pricing strategy of self-pubbed authors, where somewhat more than half (56%) prefer the volume sales model while the remaining minority (of 44%) think selling at a higher price is the way to go. Unfortunately, the survey did not elaborate on these points, which would have been highly enlightening, since there are many reasons for (and against) both views. It would be useful to know, for example, which of these models was the more successful, and if a higher retail price with fewer sales equated to more or less income, and more or less satisfied readers, with higher or lower average reader ratings.

And finally, the Taleist report concluded that authors who got outside help with issues such as editing and cover design earned 34% more than the average, although 70% of respondents did not do so. Apparently more authors feel that books are judged more by their cover than their content, as 41% invested in a professional cover design, while only 29% shelled out for copy editing.

Surveys such as this are only snapshots of a segment of the industry, but they can shed some light on what is happening and how to make the best of it. You can buy the full report on Amazon for five bucks.

Published on May 25, 2012 22:15

May 20, 2012

Infographic: Self Publishing By The Numbers

I love Infographics, and this is a particularly interesting one. It's packed with loads of information comparing traditional publishing to the newly emergent self-pub trend, with a couple of "case studies" for good measure. Some of the info is outdated, such as Amanda Hocking turning down a trade pub deal in favor of self-publishing, when she signed a trade deal well over a year ago (March 2011), or providing sales data for January 2010 that are hardly relevant in May 2012.

In addition, while many writers use Lulu for print-on-demand self-publishing, it's far from the cheapest route to go (both CreateSpace and Lightning Source are less expensive and used by far more authors and independent publishers), so using it as a base of comparison is hardly representative. The $300-500 Initial Outlay for POD services, for example, should start at FREE, since Amazon's CreateSpace charges no initial setup fees and provides an ISBN.

And while it's more difficult to establish an account with Lightning Source, it's well worth the effort, since their per-page charges are far less than either CreateSpace or Lulu, at .013 cents per page for 6x9" black & white plus .90 cents for the cover (and from .05 to .10 cents per page for color, depending on the page size). This makes the production cost for a 300 page paperback $4.80 rather than the $10.50 given in the example. Thus, a $15 book sold at 70% royalty returns $5.70 instead of $3.60, a $2.10 increase in profits per sale, which is more by itself than most trade published authors make as their entire royalty. Of course, you could also lower the retail price of your book and sell more copies instead.

But all in all the data provided in this Infographic is valid and provides a generally accurate comparison of the two opposing business models, clearly illustrating why self-publishing has become so popular of late.

Infographic by: Website Creation.com

In addition, while many writers use Lulu for print-on-demand self-publishing, it's far from the cheapest route to go (both CreateSpace and Lightning Source are less expensive and used by far more authors and independent publishers), so using it as a base of comparison is hardly representative. The $300-500 Initial Outlay for POD services, for example, should start at FREE, since Amazon's CreateSpace charges no initial setup fees and provides an ISBN.

And while it's more difficult to establish an account with Lightning Source, it's well worth the effort, since their per-page charges are far less than either CreateSpace or Lulu, at .013 cents per page for 6x9" black & white plus .90 cents for the cover (and from .05 to .10 cents per page for color, depending on the page size). This makes the production cost for a 300 page paperback $4.80 rather than the $10.50 given in the example. Thus, a $15 book sold at 70% royalty returns $5.70 instead of $3.60, a $2.10 increase in profits per sale, which is more by itself than most trade published authors make as their entire royalty. Of course, you could also lower the retail price of your book and sell more copies instead.

But all in all the data provided in this Infographic is valid and provides a generally accurate comparison of the two opposing business models, clearly illustrating why self-publishing has become so popular of late.

Infographic by: Website Creation.com

Published on May 20, 2012 12:44

May 19, 2012

Global eBooks Sales Up 332%

The Association of American Publishers (AAP) released a new report yesterday detailing 2011 sales data for U.S. book exports, and the rate of digital growth worldwide is quite astonishing. With U.S. ebooks and e-reading devices becoming available internationally only within the last few years, the increase is not entirely surprising, but the rate of adoption in some quarters is rather staggering considering the overall economic climate.

Total U.S. book export sales for 2011 were $357.4 million (71.9 million units), up a modest 7.2% over 2010. Total eBook sales were $21.5 million (3.4 million units), up 332.6% from 2010's $4.9 million total revenue. That makes ebooks just a little over 6% of the global book market, with a lot of room to grow.

The AAP report breaks down the print and ebook stats for four of the leading regions in the West in terms of rapid growth:

U.K. ebook sales increased by 1316.8%, while print was up 10.4%

Africa saw ebooks rise by 636.8%, with print up 17.1%

Continental Europe grew its digital by 218.8% and print by 9.5%

Latin America saw ebooks grow by 201.6%, while print was up by 9.7%

No statistics were given for Eastern regions. U.S. publishers currently export roughly 90% of their titles to retailers in 200 countries.

This rapid increase in digital adoption worldwide is the result of markets opening in many regions for the first time, with new Amazon stores in Italy and Spain, new devices now being released internationally soon after their U.S. launch, if not day and date (although there's still a significant lag with, for example, the Kindle Fire not yet available in the U.K. six months after its launch). Instant access to digital content via global networks is becoming more widespread with distribution and marketing limited only by international trade agreements and copyright laws. Within ten years there will be no limits at all, with anyone able to buy a book anywhere at any time, and start reading it instantly (barring governmental restrictions on free speech and commerce, that is).

The implications of this cannot be understated. What is occurring is the creation of a one-world market, a global economy with no borders or barriers, with a resulting increase in literacy and intellectual communication. What the Internet has done for information, ebooks will do for reading in a way that print just can't achieve due to its cost to print and ship. What excites me most when I see these numbers is that it represents a hunger for books, for reading, for intellectual stimulation that stretches the mind and broadens the horizons. With the overwhelming glut of media available these days, it's good to see that kids still want to read, that people love to dive into a good book, to curl up with their Nook or Kindle and get lost. Words have power, to transform, to change, to alter the world we live in, and the more people read them the more possible those changes are.

Published on May 19, 2012 13:15

May 13, 2012

The Kindle Color Touch

Another prediction that I made for 2012 looks to be close to fruition as well, and this is one I'm very excited about. DigiTimes is reporting that Amazon plans to launch their first Kindle with a color eInk screen in the latter half of this year, most likely in September. According to supply chain sources, orders have been placed for color touch screen panels from TPK Holding, with components to begin shipping this month.

The new Kindle model will feature multi-touch capacitive displays rather than the infrared panels used currently. Both have pros and cons, but the capacitive panels are generally less sensitive to dust and dirt or interference caused by hovering a finger just above the surface. However, they cannot be used with gloves on as infrared displays can, so reading while waiting at a bus stop in January will be much less pleasant. The main advantage of capacitive touch panels is their faster response time, although they are slightly less clear due to patterning in the glass, with a slightly lower light transmission rate than infrared displays.

With the Nook Touch now sporting the nifty Glowlight feature, Amazon's eInk reader line needs a boost to keep up with the pace of progress. Barnes & Noble have been ahead at every step in device development, putting out the first eInk touch screen reader last May (with Amazon following in September), and now the first with a built in backlight, released just last month. BN also launched the LCD screen Nook Color back in October of 2010, with Amazon following their lead a full year later with the Kindle Fire. This is somewhat surprising given that Amazon was two years ahead of Barnes & Noble getting into ebook readers in the first place (although Sony beat them both, releasing the first eInk reader back in 2004, three years ahead of the Kindle). But Amazon could leap ahead again with the first full color electronic paper display (EPD) launched in the U.S. (Ectaco's Jetbook Color launched in Russia last September, while Hanvon released the first color eInk reader in China back in November 2010).

Ectaco JetBook with Triton Color E-Ink screen

According to E Ink Holdings chairman Scott Liu, the company will unveil new EPD screens soon, which presumably will be the ones to be adopted by Amazon for the "Kindle Color" line. Look to see the fifth generation Kindle this September with a full color eInk touchscreen and built in backlight. Due to the higher cost of components for color screens my guess is it will retail in the $149 range, with the 4th generation black and white devices staying in production as the low-cost entry level models, the bottom end dropping down to around $49 by Christmas.

This, of course, is all speculation.

Published on May 13, 2012 10:17

May 11, 2012

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt to File for Bankruptcy

One of my predictions for 2012 was that one of the major trades would fall prey to bad business decisions based on outmoded operating models and file for bankruptcy protection, and today the Wall Street Journal reports that Houghton Mifflin Harcourt have done just that.

In retrospect this is hardly surprising, given HMH's heavy reliance on the educational market, which has declined by 48% over the past four years, due primarily to cuts in school budgets, but also because of a shift away from printed textbooks to laptops and tablets. In addition, they've been struggling under a capital restructuring plan since January (their second in as many years), with a hefty burden of $3.1 billion dollars in debts that is nearly three times their total gross sales for all of 2011 ($1.3 billion before expenses). And as with all the major trades, HMH has been reluctant to transition into digital, with major list authors like J.R.R. Tolkien only recently becoming available in official ebook editions (just this February for Tolkien, in fact).

Such blundering moves by short-sighted corporate heads are not uncommon, and HMH have made their share. Just four years ago the head of the trade division resigned in protest when the company put a freeze on acquisitions of new titles, a move seen by trade insiders as a monumental blunder when faced with lagging sales. Without new books to offer sales can only stagnate and decline. In 2009, HMH was ranked the 10th worst place to work in America, according to one survey.

In truth, HMH has been operating in debt for over a decade, with new ownership or mergers occurring nearly every year since 2001. But none of the new owners or executives were visionary enough to see the shifting tradewinds, or turn about a ship clearly riding contrary to the current. Whether or not it can ride out the tide will depend on how quickly and effectively they can retool for the new digital medium, particularly with regard to taking on Apple for domination of the educational arena. But big boats turn slowly, and Apple are already heading in the right direction. If HMH simply continue to operate on the business-as-usual model that ship is gonna sink.

Published on May 11, 2012 16:28

May 10, 2012

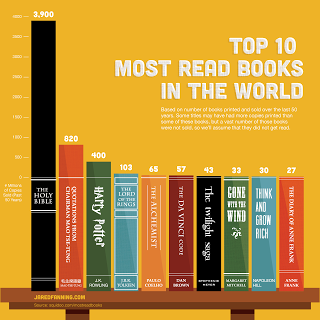

Comments on the Top 10 Most Read Books In The World

I saw this the other day and thought it was really interesting. First of all, it's a cool way to visualize the data, and the graphic itself is nicely done, with the font and design elements replicating the actual print editions of each title. I like graphics, and I like statistics, and I like books, so this was right up my alley.

Of course, what's most interesting is the content. What it represents is the number of copies each of the top ten titles has sold in the past fifty years. That is sold, mind you, not read. There's a big difference. Of these top 10 titles, six are works of fiction (seven if you're an atheist), with the top and bottom two falling into the non-fiction category. The top and bottom are works of an historical nature, while the second to the top and bottom fall into the "inspirational" category, at least in intent (and only if you find these subjects inspiring, of course). Six of these works were originally written in English, and all but The Holy Bible within the last century. Nearly all of the popular fiction works fall within the past fifty years, within the time frame that the statistics take into account (or very shortly before that) - only The Lord of the Rings and Gone With The Wind are older than that - while the three most well recognized by modern readers fall into the "pop culture" bin of the most recent two to three decades (these being Harry Potter, The DaVinci Code, and The Twilight Saga, the most poorly written of the bunch, and of modern literature in general).

Conversely, all of the non-fiction works are more than fifty years old, save for Mao's Little Red Book (otherwise known as Quotations from...), which was first published in 1964. Think and Grow Rich was issued in 1937 and continues to be the best-selling "get rich quick" treatise on the market, and will likely remain so for as long as there are people who want to get rich just by thinking about it (the book, of course, is not about getting rich quick at all, but that seems to be what everybody thinks it's about). After all, it costs nothing to read (if you're a patron of the local library, that is), and even less to sit around thinking about getting rich all day.

My bet is that the three "pop culture" titles will fall off the list within the next ten years, while the more well-crafted works will remain, at least until equally well-crafted and deserving works appear. The influence of The Lord of the Rings has only grown with time as readers discover its astonishing depth and complexity, while Harry Potter's influence will likely wane as the legions of fans outgrow their childhood (if not their fifth grade reading level) and The Twilight Saga becomes gradually indistinguishable from the hundred other vampire-werewolf romance novels out there. Of the "pop culture" trio only The DaVinci Code will have any lasting impact, due not only to its controversial subject matter, but also its pseudo-historical context, which proves ever relevant and fascinating for conspiracy theorists of a literary bent (and there will always be boat-loads of those). The Alchemist is a bit of a dark horse here, being a truly unique entry among these titles, as both a work of fiction and an inspirational self-help allegory. It's hard telling what a book like this will say to people from one generation to the next. It's difficult to say what it means to people today.

As for the other non-fiction works, Mao's book will disappear as soon as he does (i.e. not soon enough), and Gone With the Wind will be just that, as younger generations fail to find an interest in outdated fictional history (read: stuffy and irrelevant). Anne Frank, of course, will have a lasting impact on the history of civilization, of the type that only grows with time and perspective - up to a point, at which it becomes ancient history, and no longer poignant (after all, who reads Caesar these days?). But that won't happen in our lifetime, because for at least the next century WWII will remain recent history, all too close for comfort. What will become of The Holy Bible is anyone's guess. Religion is a fickle mistress.

What would be more interesting here, to my mind, would be a comparative statistic of how many of these purchased books were actually read. The graphic's caption makes the distinction between number of books printed and number actually sold, but more important is the number actually read, a figure unfortunately impossible to determine. My guess is that more than half the Bibles lying around have barely had their covers cracked, while nearly every copy of Harry Potter has long since become tattered and dog-eared. The vast majority of purchased Bibles are bought in bulk by churches and related ministries to give away to third world nations and stock the drawers of cheap hotels. Additionally, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of variations of the Holy Bible, from tiny pocket editions in condensed form to fully annotated comparative editions in multi-column translations. All those count as a Bible sold. Still, 3.9 billion is a lot of books in any form. Too bad the author's not around to get those royalties.

Published on May 10, 2012 19:42

May 6, 2012

The "100,000 Visitors" Giveaway

In recognition of the rapidly approaching milestone of 100,000 page views on this blog I've decided to mark the occasion with a contest. As a way of saying thanks for stopping by I'll be giving away a 2-volume print edition of The Saga of Beowulf, autographed and shipped wherever you would like, plus two ebook editions in the format of your choice for the 2nd and 3rd place runners-up.

To enter, simply go to the Fantasy Castle Books website and register or login and send a message to the Contest Department via the contact page mentioning this giveaway. Be sure to opt in for the newsletter to receive news and updates on the progress of the new book and developments on the website, which is in the midst of being rebuilt at the moment.

Deadline for entry is Friday, May 11th at midnight Mountain Standard Time (GMT-6), with the drawing to be held on Saturday as soon as I wake up. Entries will be drawn at random using Random.org's list randomizer and integer generator. Best of luck, and thanks again for stopping by!

Published on May 06, 2012 22:24

April 30, 2012

Microsoft Returns to the eBook Business

In mid-August of last year Microsoft announced that it would be pulling the plug on its eleven year old Reader software and the .lit format it supported. No official reason was given, and the company stated unequivocally that they would not produce a new e-Reader software or even help their customers migrate their .lit files to another ebook platform. They would continue to provide downloads of the Reader software for a year - until August 30th of this year - but after that you're on your own. The online Reader store closed up in mid-November, and it looked to be the end of ebooks for Microsoft.

I had been a fan of Reader and the .lit format almost since its inception back in August of 2000: ClearType was a huge improvement over the basic text files I'd been gleaning from Project Gutenberg, making the text crisp and clear on the tiny iPaq Pocket PC that I had bought on its release that April and had carried with me ever since. The device's 32 Mb of onboard storage, augmented by an additional 128 Mb SD card, meant that I could carry dozens - if not hundreds - of ebooks with me wherever I went! Between the two my reading intake increased ten-fold. In addition, the ability to highlight passages and insert notes or scribble doodles with the stylus, as well as searching through the document, was a quantum leap in reading. For me, the digital revolution began way back there with the new millennium, and I haven't looked back since.

More importantly, the Reader add-on for Word allowed me to create .lit ebooks instantly from any document, and Gutenberg soon began doing so themselves. This meant that I would never run out of content to read, so long as the software was supported.

So it was with great sadness, and some bitter disappointment, that I bid farewell to Reader. My iPaq had long since given up the ghost, and a newer version purchased after HP's acquisition of Compaq was soon replaced by a new kid on the block: a first generation Kindle. Things would never be the same, and Microsoft new it.

In retrospect, it's one of the more curious business decisions of that first decade of the 21st century that Microsoft chose not to press its advantage in the ebook space by producing a hardware device of its own to support that pioneering digital format. But Microsoft have always been a software company rather than a hardware manufacturer, and perhaps they didn't see a future in competing with a retail giant like Amazon in that arena. Or maybe they just misjudged the impact the Kindle would have on the world of publishing. They had, after all, seen a hundred other ebook formats come and go with little or no impact on the reading world. For all its advances, their own format had barely left an impression on the general book-buying public, and the ebook market was essentially non-existent, so one can hardly blame them.

So not surprisingly, it was with much interest that I read the press release this morning announcing that Microsoft had partnered with Barnes & Noble to create a new subsidiary company that will house B&N's digital content, including the Nook devices and app software, as well as their educational division. Microsoft will infuse $300 million into the venture (currently dubbed "Newco") for a 17.6% stake in equity, and bundle the Nook app in its upcoming Windows 8 OS. At one fell swoop this lifts B&N's digital outlook from troubled waters to fast track for global domination, while virtually dooming its brick and mortar stores to second-rate obscurity in a heartbeat.

According to the press release, the intention of the new partnership is to "accelerate the transition to e-reading." "We're on the cusp of a revolution in reading," it says. What this tells me is that the captain is jumping from a sinking ship in shark infested waters to firmer ground aboard an ocean liner bound for the tropics. While Barnes & Noble's announcement states that Newco "will have an ongoing relationship with the company's retail stores," it goes on to say that "The company intends to explore all alternatives for how a strategic separation of Newco may occur." B&N had announced back in January that it was exploring just such a "strategic separation" of the digital side of the business from the physical, and we have now seen the means by which this will occur: Newco will thrive, Barnes & Noble will not.

Partnering with Microsoft does a number of important things beyond the obvious monetary clout it brings. It gives them a global platform in the form of Windows, allowing Nook to piggyback on Microsoft's extensive reach: with the release of Windows 8 later this year Barnes & Noble will go from virtually no international presence whatsoever for its ebook format to near absolute saturation overnight. Expect to see a massive winding up of its online presence in the meantime, if not an all-new web store for "Newco". Secondly, this makes absolutely clear BN's intentions with regards to divesting its digital revenue from the shackles of the brick and mortar store. Nook "boutiques" are likely to remain in place so long as there's a place for them to remain, but henceforth they'll reside in rented space that they can easily move elsewhere should such a move prove beneficial. My guess is Nook boutiques will start to spring up in mall kiosks and stand-alone outlets as print books disappear.

Most importantly, however, is the reinforcement this brings to the digital consumer. I have personally avoided buying Nook ebooks for the very reason my .lit experience dictates: with Barnes & Noble teetering on the brink of financial oblivion, why in my right mind would I invest in a library of content that may or may not be supported just a few years down the road? After the demise of Borders last year the stability of Barnes & Noble came far more into question, whereas the chances of Amazon or Apple going by the wayside anytime soon don't appear too probable.

And while I can convert my .lit archive to other formats via software such as Calibre, the conversion isn't perfect and it's a lot of time and trouble I just as soon avoid. So the support of Microsoft goes a long way to assuaging my anxiety with regards to the Nook platform. The physical stores my go away, but for now at least, it looks as if the Nook is here to stay. And it will probably be running a Windows Mobile OS next year.

Published on April 30, 2012 20:08

April 23, 2012

Why Encyclopaedia Britannica Went Out Of Print

The Encyclopaedia Britannica has been publishing its behemoth multi-volume compendium of human knowledge for 244 years, since it first appeared in 1768. That first edition consisted of just 3 volumes running 2,670 pages, growing through continual revision and expansion until it reached its final size of 32,030 pages spread across 32 volumes with the 15th edition in 1985. Production of the initial 15th edition required ten years at a cost of $32 million. The cost of a full set would run you $2,200.

The glacially slow pace of production has always been a difficulty with print, and all the more so when its content is in need of continual revision. With the pace of information changing at an ever increasing speed, it was only a matter of time before the rate of change outpaced Britannica's ability to keep up. With a new edition being published only every quarter-century such innovations as the Internet or the iPad might not have gained an entry into Britannica until better than a decade after their advent. By the time the $32 million dollar 15th edition appeared it was already outdated.

Although a policy of "continual revision" had been instituted in 1933 to deal with just this issue (in which new printing was done every year, with time-sensitive entries being updated in the intervening months), rapidly evolving fields of knowledge such as science and technology have continued to escalate at an exponential rate, making even a year too long a span of time to stay up to date, particularly in the face of a globally networked information age where news appears online the moment it occurs.

But the beginning of the end for Britannica in print actually began back in 1980, when the publishers declined an offer from Microsoft to produce the first comprehensive CD-ROM encyclopedia, believing it would cheapen their brand and undermine print sales (sound familiar anyone?). Undeterred, Microsoft went on to create Encarta using content from Funk & Wagnalls Standard Encyclopedia instead. Encarta would become a mainstay of computer reference works for years to come, with the result that within three years of its release in 1993 sales of Britannica had declined by half, from an all-time high of $650 million in 1990 to $325 million by 1996, with print edition sales dropping from 117,000 to 55,000 units.

Meanwhile, the publishers had seen the errors of their ways and released a CD-ROM set of their own in 1994 (for just $995), as well as launching Britannica online, with a subscription rate of a mere $2000. Within two years the CD-ROM had dropped to two hundred bucks. The company was sold that same year to a Swiss financier for a paltry $125 million, a fraction of its former worth. Today, you can get the iPad app for free, with access to full content for just $1.99 per month. Information, they say, is power, and in a world where information is available only to the wealthy that power remains concentrated. When information is free, everybody is enriched.

The Britannica today: an interactive hyperlinked network of knowledge

Britannica has not been without its scandals or controversies either. From its cheapening through doorstep hawking during the Sears & Roebuck years (1920-1943), with its subsequent "simplifying" of information for a common populace, to the publication of Einbinder's scathing 1964 exposé, The Myth of Britannica (which found enough faults to fill up 390 pages of diatribe), it's hardly any wonder the free online resource Wikipedia flourished virtually overnight (Wikipedia is currently ranked #6 by Alexa, while E.B. Online is #114,852). Of course, it's two-thousand dollar price tag hasn't help much.

And lest you scoff at the vagaries of a public information database such as Wikipedia compared to the staunch authority that is the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the journal Nature undertook a study in 2005 that showed articles in Britannica to be hardly more accurate than those on Wikipedia: the former had an average 2.92 mistakes per article while the latter rated only marginally worse with 3.86. Of course, few would argue that the credentials of Britannica contributors are vastly more authoritative, although Wikipedia has gotten much more stringent in its reference requirements over the years. And if you're talking about online authority, Alexa reveals that 2,123,583 sites link in to Wikipedia, while only 7,180 link to eb.com, which tells us where people are getting their information these days.

But the real point of all this is the general shift from print to digital that's occurring globally. Print suffers in nearly every way when compared to digital. Not only is digital dynamic and interactive, but it's unhindered by print's inherent limitations via an infinite network of hyperlinks. It allows for instantaneous access to a wide array of media, its content is specifically targeted to the user's needs, and it's continually evolving as the network itself evolves: every link leads to a destination that may have been updated since your last visit, even if that visit was just an hour ago. It will not fade or age with time, every copy is an identical reproduction of the original, and it doesn't take up any space.

The end of Britannica in print should serve as an object lesson for other entrenched publishers and slow-moving behemoths. The world we live in today is changing rapidly, and one can either change with it or be left behind, because that change is coming whether you're onboard with it or not. The end of Britannica in print should not be marked with sadness for its passing, but rather as an affirmation of the march of human progress.

Published on April 23, 2012 17:09

April 22, 2012

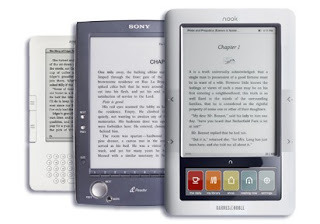

Dedicated eReader Use Rises 250% in 2011

According to a new report by TDG Research, 20% of U.S. households with Internet access now also own at least one dedicated e-reading device. That represents a 250% increase from the 8% just twelve months earlier, at the end of 2010.

The new report focused specifically on "dedicated" reading devices - those designed and intended to be used solely, or primarily, for reading digital content, as opposed to multi-media devices - as this is a practical concern for current device manufacturers and retailers with a digital product line and content designed to be read on it.

With the recent introduction of lower priced, full-function tablets, there has been much speculation as to whether a market for dedicated e-readers would continue to exist, and if so, how significant it might be. Yet while multipurpose devices have begun to reach a price level more accessible to the general populace, e-reader prices have dropped proportionally as well, bringing them well within the grasp of average users rather than early adopters and tech aficionados. And this is almost certain to remain the case for years to come - we'll very likely see dedicated e-readers fall below the $50 mark within a year or so, with low-end models eventually retailing under $30 (subsidized largely by content sales). This would give them a great advantage over tablets for such institutions as schools and libraries, for example.

Conversely, it's unlikely multi-purpose tablet devices will fall below $100 for several years, although a $99 Fire or Nook Tablet is not unthinkable at some point down the line. Still, less functional devices will always remain less expensive than more complex machines, due simply to the cost of production, making them naturally more appealing to a broader audience. The fact that digital reading has increased at a more or less proportionate rate to the decrease in device cost only goes to prove the point. With e-reader prices dropping below $100 for the first time last year, digital adoption has hit its highest peak.

Finally, readers will be readers, and in the end what they want in their hands is a book, not a computer. The advantages of digital make dedicated e-readers attractive, and the added features are a great benefit, but it doesn't make the leap to app-based tablet computing a given (although for some this is certainly the case, and tablet saturation will surely continue to increase at its current remarkable rate as well). In addition, they are easier to use and lighter to hold or carry around, which makes them ideal for travel and commuting. In essence, tablets and dedicated e-readers will become the hardbacks and paperbacks of the future.

The 36 page TDG report, "Profiling eReader Users -- A Consumer Snapshot," is available for just $2,500.

Published on April 22, 2012 10:57