R. Scot Johns's Blog, page 8

March 24, 2013

Kindle Fixed Layout Tutorial - Part 11

PAGES

Having gotten the support files out of the way, we can now turn our attention to the actual pages of the ebook. From this point forward we will be examining each page of the Basic and Advanced Templates, beginning with the simple image-only content and progressing in stages through increasingly complex layouts, complete with overlays and zoom functions.

Before we begin a short prologue is in order regarding the files required to create the page layouts themselves. As mentioned previously, each page in a fixed layout ebook is contained within a separate HTML file, formatted to the size of the default display as discussed in the section on images above. We will see how this is done in a moment.

The HTML file contains all of the text for that page, and/or links that tell the reading system which images to insert into that page (if any). Each of these content elements are enclosed within a variety of “containers” that can be sized and styled and placed into position using class and/or id tags, such as:

<div id=“container1” class=“fullpage”>

Some content goes here.

</div>

The div is a “division” of the content that functions as a container for that section of content, and can best be thought of as a text box, although it can contain images as well, and even other divs within it. In this way you can visualize each page as a series of containers within containers, each with a definable height and width, and which can be placed precisely on the page. The page itself consists of an all-encompassing div that contains all of the other elements on that page.

We will spend nearly all the remainder of this book looking at the various content elements in a Kindle fixed layout ebook and how to place them on the page. However, before getting to that content, a few things should be pointed out here with regard to how HTML code works for those who have never used it before, since I must assume there will be some of these among the readers of this tutorial. Many lengthy textbooks have been written on the subject, but a few basic facts are all that are required to begin.

Firstly, each of the attribute tags that surround the content elements in an HTML file are references to an entry in the related CSS file that determines how that content should be styled, which includes all aspects of its visual presentation. CSS stands for Cascading Style Sheet, and is a secondary document, or set of documents, that contains all the styling data for these tags. The relevant CSS is referenced from each HTML file, so that the reading system knows where to look for this information.

If you look inside any of the HTML files contained in either of the templates, or in any ebook file, you will see there are two main sections below the namespace declaration: a <head> section and a <body> section. In the <head> section you will find a line containing the <title> (where you simply enter the title of your publication), a <meta> entry which gives the encoding information for the content, telling the reading system what it’s looking at (you don’t need to change anything here), and finally a <link> to the CSS file, such as:

<link rel=“stylesheet” href=“../css/stylesheet.css” type=“text/css” />

The three attributes may be in any order, but each must be present. The only one you need to change, however, is the href defining the link, or location, of the css file. In this case the ../ portion tells the system to begin looking for the file at the root level, since this particular file is in a neighboring branch folder labeled css.

A second general point to make concerns the difference between the class and id tags. These are often confused, and even used interchangeably, but in proper usage the id tag is used to “identify” one specific instance of an element, such as a particular div on a page, and consequently are generally used in fixed layouts to define the size and position of a given element, rather than its visual style (although they can contain some, such as when there is no need to create a whole new class for just that one instance). Conversely, class tags can be applied to any number of elements, and thus contain general styling data, such as color and weight for text, or border style and background-color for containers.

Inside the CSS file you will find something called a CSS Reset. This is a long string of common code elements set to a default neutral value. This is done so as to override any inherent browser settings that might be added if the file is opened in a third-party reader, since many browsers include their own default values. This sets everything to zero so that nothing goes awry. There are many CSS Resets that can be found online, but in Amazon’s samples they include the one from Yahoo! that is found in both of the templates.

Finally, with regard to positioning in fixed layouts, you must use absolute positioning for all divs in order to affix their position, but the content within those containers can have relative positioning, as, for example, to center align a block of text, which can only be done using relative positioning (since its position is inherently relative to the borders on either side). You can, of course, also use absolute positioning for content within a div. We will see a variety of ways to do this very soon, but be aware that this is very often an attribute that trips up even seasoned formatting veterans, since it can throw off everything with wildly unexpected results! If things are just not showing up where they should be, go back and check your positioning values. Chances are you’ll find one that should be the other.

Published on March 24, 2013 17:30

February 18, 2013

Kindle Fixed Layout Functionality [UPDATED 2-18-13]

Before we dive into the next portion of the tutorial, I thought it would be useful to post the following chart which comprises Appendix A of the ebook. This information will be discussed thoroughly and referred to throughout the tutorial, so having it beforehand might be helpful (especially since the ebook isn't out yet). And since much of it will make no sense without some explanation, I will provide a short introductory breakdown here as well. This will get a little technical, and may well make no sense at first for some of you (if so, just skip it for now and refer back when necessary), but it will all become clear in time. First, the chart...

Function

Booktype

Kindle

3

Paper

white

Fire

(Gen1)

HD7

HD9

PC

app

Android

app

1 - Page-Spread

Comic

Children

None

N/A

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

2 - Letterbox Color

Comic

Children

None

White

White

White

White

White

White

White

White

White

Black

White

White

Black

White

White

Choice

Choice

Choice

White

White

White

3 - Virtual Panels

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

4 - HTML Image Zoom

Comic

Children

None

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

5 - Cover Image Access

Comic

Children

None

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

6 - Cover Doubling

Comic

Children

None

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

7 - TOC Menu Link

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

NONE

No

No

NONE

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

8 - Bookmarks

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

9 - Live Text Functions

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

10 - Hyperlinks

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

11 - Font Embedding

Comic

Children

None

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Each of the 11 rows features one functionality element in KF8 that I have tested on the devices and apps listed in the five columns to the right. These are (in order): the Kindle for PC desktop application, a first generation Kindle Fire, the new Kindle HD 7" and HD 8.9" devices, and the Kindle for Android app. Unfortunately, I do not have a second generation Kindle Fire to test, nor a Mac on which to test the Kindle for Mac desktop application. And, of course, as mentioned in the Introduction, fixed layout files cannot be tested in the Kindle for iOS/iPad app, since transferring them in any way I have attempted (Dropbox / DiskAid / Send To Kindle) actually breaks the file. I didn't bother testing these on my Paperwhite or Kindle 3 keyboard model, since comics and graphic novels on these devices are pointless, even though technically they now support the format [see Update below].

As mentioned previously, there are two official book types for Kindle fixed layouts, defined by the appropriately titled "booktype" metadata value in the OPF file (to be discussed in an upcoming section), these being "children" and "comic." But, of course, you can also enter "none" (or simply leave it out), making essentially a third practical booktype. Unlike all the other Amazon-specific metadata values, which determine functionality for a specific listed attribute (such as fixed-layout or orientation, for example), the "booktype" attribute effects a broad range of overall ebook functionality - none of which is detailed by Amazon in their documentation. Hence, this chart. In it, each of the listed functions has been tested with each of the three booktype values set.

In addition, each of the three was tested with the RegionMagnification set both to "true" and to "false," since Amazon states in the Kindle Publishing Guidelines (Section 5.7) that the new Virtual Panels feature (row 3) is reliant upon this setting. This does not prove to be the case, as thorough testing resulted in no change whatsoever in the Virtual Panels functionality with either setting on any device or app. This, of course, may change in future updates, and I will update the chart accordingly at that time. But I have made no note of this distinction in the chart at present, since there is none.

Also, I should point out that in every case changing the booktype made no difference to the functionality of the Kindle for PC app, which appears to simply ignore the setting.

I have entered bold text for the results that stand out as the exception to the rule in order to make the disparity more readily apparent at a glance, and to point out issues with the functionality.

In addition, Appendix A provides no test results for region magnification features (aside from the new Virtual Panels function), as this is contained in Appendix B, and will be dealt with in the latter, more complex portions of the tutorial.

And now the breakdown...

1. Page Spread

A new function in KF8 is the "page-id" spine element which (purportedly) allows for the creation of two-page spreads in landscape mode (either with or without a margin in between). As you can see from the chart, this is only consistently true for the HD 8.9" ('HD9') device, while the HD7 and Android app work correctly with the "comic" booktype value only. In all other cases only one page is shown at a time in landscape mode. Even the Kindle for PC app, which shows an activated two-page button icon, does not actually display two page spreads.

2. Letterbox Color

This refers to the color used to fill in any display space outside the page area, much like the "letterboxing" used in widescreen movies on a 4:3 format television (or iPad). I only tested this because I noticed it was sometimes black and sometimes white and wasn't really paying attention at first to when and where. As it turns out it's only black on the two new HD devices with the "comic" booktype chosen, and white at all other times, with the sole exception of Kindle for PC, where the three standard values of white, sepia, or black are all still available. Not critical, but sometimes one or the other blends better, so it is interesting to know. And given that it is the newest of the Kindle line that sport the black background, this may be an indication of future changes.

3. Virtual Panels

This new feature is apparently a fallback for fixed layout ebooks that have no custom region magnification elements included, and works by dividing the page into four equal quadrants (or "panels") that are zoomed by tapping and advanced in sequential order by swiping (the ordering being based on the "primary-writing-mode" value to allow for right-to-left and left-to-right reading order). Surprisingly, the zoomed page can also then be scrolled around by dragging, and variably resized using pinch-and-zoom, making it a very nice add-on feature for most fixed layout ebooks (in the absence of precisely placed mag zones, that is). As already mentioned, it is supposedly activated by default when the RegionMagnification value is "false," but this value actually has no effect at present: Virtual Panels either work in a particular Kindle reader or their don't, and in most cases they don't. In fact, in only two instances does this currently work: on the HD7 and Kindle for Android app, and only when the booktype is set to "comic." My guess is this feature will continue to roll out until all Kindle iterations have it - aside, perhaps, from the HD9, which somewhat surprisingly doesn't have it; but, then, it doesn't really need it, either, due to its size. However, as you'll see in the next item, you can actually zoom images on the HD9 in certain instances.

4. HTML Image Zoom

This ties in somewhat with the last item, since only one or the other can work. This relates to the HTML <img src="http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheAdv... insertion method for adding background images in fixed layout, as opposed to the <div id="...> method of referencing a CSS background-image url. Amazon recommends the latter, but for reasons I will discuss later, I disagree (in fact, Section 4.2.3 of the Guidelines says it's a requirement, because "HTML images interfere with Region Magnification," which is demonstrably untrue). The important factor here, however, is that the <img src="http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheAdv... method allows the user to zoom a background image by double-tapping on it anywhere that it's not overlaid by text or Tap Targets, while the CSS method does not. This allows for zooming and scrolling entire background images (minus any text overlays), which until Virtual Panels was the only way this could be done. However, since the Virtual Panels function effectively creates a Tap Target covering the entire page, where that feature is active this one cannot be, since the background image cannot be tapped (the images still appear correctly using the HTML insertion method, so there's no issue where the image's placement is concerned). That said, assuming the RegionMag "true/false" value will eventually work as stated, you will then be able to chose one or the other, so this information will still theoretically be relevant. As seen in the chart, however, it's not just the Virtual Panels factor that determines whether <Img Src> Zoom works or not, since in no case does it work with the "comic" booktype value chosen. But since this is - at present - the only place where Virtual Panels works, in all other case (aside from Kindle for PC) this image zoom method works. An important distinction to make between Virtual Panels and the HTML "img src" method is that that latter only magnifies the actual background image (which is sometimes desirable and sometimes not), while Virtual Panels zooms the entire page, including text overlays, making it more like the iPad's pinch and zoom feature than Kindle's standard Panel View. (For an additional difficulty with Virtual Panels, see number 10. Hyperlinks below.)

5. Cover Image Access

6. HTML Cover Doubling

These two go hand-in-hand, and it all really comes down to one thing: Amazon flat out got it wrong on this one. In Sections 4.2.4 and 4.3.7 of the Kindle Publishing Guidelines Amazon either "requires" or "recommends" (depending on the section) than an HTML page containing the cover image be included in fixed layout files, even though in Section 3.2.3 they unequivocally state that you are not to do this because the cover image may appear twice - which is, in fact, exactly what happens in every instance. They then contradict themselves further by providing (in Section 3.2.3) one exception to this rule, in which case you must enter the linear="no" value to the spine entry for this element (the underlined element being "mandatory"); but then in the later two sections they state that the same value must be set to "yes." All this contradictory information can be cleared away easily by the facts: if an HTML cover is included, the cover image always appears twice. "Cover Image Access" simply refers to whether you can swipe back to the cover once you have moved forward into the book, and was tested in conjunction with the cover doubling issue to see how pervasive the latter was. In only one instance are you not able to return to the cover (even the HTML one) by swiping (or tapping), which is on the HD7. You can still access the cover via the menu link on this device, when again you will be presented with two consecutive covers, one JPEG, one HTML, but you cannot swipe back to it once into the book, whereas on every other device or app you can do so, and there will always be two consecutive cover images in a row. Therefore, there is simply no reason whatsoever to include an HTML cover, and several good reasons not to.

7. TOC Menu Link

Since we're on the subject of menu links, here's another issue to consider. For some unfathomable reason, Amazon has decided to remove the "Table of Contents" link from the default "Go To" menu on the new HD devices. And not only that, but on ebooks with the "children" booktype value the entire "Go To" menu is inexplicably missing. Gone. Completely absent. No links to the cover, the beginning, or any other internal links. Apparently they think readers of children's ebooks don't use menus, nor that comics should ever have a Table of Contents - which, granted, they often don't, but lengthy graphic novels could certainly benefit from one. Perhaps they thought removing it was better than including a Go To menu where all the links are non-functional, but even so, removing the option is a bit reactionary, especially considering that the menu is still present and fully functional in all other Kindle readers.

8. Bookmarks

9. Live Text Functions (inc. Notes, Highlights, Search, & Definitions)

Of all the ebook functions that should never be disabled, these are the ones. If any feature promotes digital reading over print it's the ability to interact in highly useful and informative ways with the text. Being able to annotate, highlight (without ruining the book!), instantly search the entire text, and get the meaning of any word with just a tap of your finger - not to mention adding as many bookmarks as you like - are just some of the wonders that set ebooks apart. And yet Amazon has somehow decided (intentionally or inadvertently) that these features are not needed in children's books or comics. For with either of those booktypes entered they are all disabled - with the single exception of bookmarks in "comics" on the Android app. And mind you, this is not a fixed layout issue, not some odd quirk in the fixed layout Kindle code, since when you delete the booktype value altogether (or enter "none") all this functionality is back, with the fixed layout intact. It did not used to be this way for the "children" booktype, which originally retained live text functions, although "comic" did not have them from the very first. However, disabling them for children's ebooks only happened recently. I have ranted long and often on this here before, so I won't go on at length now. To me, there is simply no justification for this decision, since decision it must be, as there is no logical reason why a manufactured metadata value would have any effect it was not designed to have, unless Amazon is just not paying attention, which I find unlikely.

10. Hyperlinks

Somewhat similar to the live text problem is the issue of interactive links, both internal and external. Here there is fortunately only one disparity, which is on the HD7, where the "comic" booktype completely disables all text hyperlinks, none of which work at all. External hyperlinks are still blue, but non-active. This is clearly related to the Virtual Panels feature, rather than live text functions, since in all but this one instance hyperlinks work correctly even where live text is disabled. But as Virtual Panels currently only work on the HD7 and the Android app, it is possible that this feature is somehow interfering with the links, since Virtual Panels overlay the entire page with a tap target. However, given that the Android app is not effected, it's uncertain what is actually causing this. My concern is that as the Virtual Panels function is rolled out across devices the loss of hyperlinks might become a widespread problem. Hopefully the HD7 issue is an aberration, but it's 50/50 at the moment, so we'll just have to wait and see. Fortunately in most cases this is not an issue at present (which is little comfort to owners of a brand new HD7).

11. Font Embedding

This was just a standard test that I'm happy to report has essentially become unnecessary, as font embedding is now supported by all tested Kindle devices and apps. This was not the case just a few short years ago, when Kindle reflowable files did not allow custom fonts. Now they do, and KF8 has supported them from inception, and happily continues to do so. I include it because it's just good to know. And it's always nice to end on a positive note.

CONCLUSION

These are all considerations each ebook designer must weigh and make decisions on, based on their project and target audience. Bear in mind that digital publishing is still in its infancy, and in a state of great upheaval at the moment. All of this will settle out in time, but for now we have to be aware of what is possible and what is not, and try to stay abreast of any changes (which are numerous and often). Already this chart shows the great disparity between a single year's development of the Kindle Fire line: in at least half the features listed there is a difference in functionality between the 1st generation Fire and the latest models.

My biggest issue continues to be the lack of support for live text when either booktype value is entered, making my clear recommendation not to add one. The only functionality that will be lost by doing this are the two instances where Page Spread works with the comic value entered, but not when it is absent - these being the HD7 and Android app - as well as Virtual Panels on the same two readers. But since these features are hardly universal, being not yet present in any other case (aside from the HD9 where Page Spread is functional regardless of booktype), there is very little incentive to add a booktype value. The primary exception, unfortunately, is that only the "comic" booktype allows images of up to 800kb in size; otherwise, you're restricted to 256kb for fixed layouts, which can be a significant consideration with the advent of HD displays. Of course, this may all change (and probably will) over time as new updates are rolled out. But one cannot plan current work based on future possibilities. One must take what data is available today and use it to inform your present efforts.

As mentioned, I will update this chart regularly, and note the changes made at the bottom of the post. If a large number of changes are suddenly made - say, when a new line of devices arrives - I will do a new post and reevaluate the situation.

And by the way, if anyone has a 2nd generation Fire or a Mac with the Kindle desktop app and can test any of these features I would very much appreciate the information. I would love to add it to the chart for reference and will gladly give you ample credit and provide a link, both here and in the published ebook. For that matter, if any of your own testing contradicts what I have listed here, please let me know so I can look into it further. Comment below or send an email to scot(at)fantasycastlebooks.com.

UPDATE 1/6/2013

Just for the sake of being thorough, I went ahead and tested the eInk Kindle 3 and Paperwhite devices. And while I won't bother to include the data in the chart above due to space restrictions, I will point out the primary data points here.

First, and most surprising, is that the Paperwhite actually supports Page-Spread in all booktypes. This is accessed via the menu's "View in Landscape" option, since the Paperwhite has no internal orientation sensor. Just as interesting is the fact that, while the Kindle 3 does not support Page-Spread, it does default to landscape orientation for the booktype values "children" and "none" (though inexplicably showing only one page at a time), while for comics it reverts to portrait orientation. There is no way to change the orientation from the Kindle 3 menu. Letterbox color is white in each instance.

Equally surprising is support for Virtual Panels on the Paperwhite with "comic" or "none" booktypes (but not for children's books). This is, therefore, the only device that currently does so with the booktype absent, and only the second device that supports it at all. Why the eInk Paperwhite would support this function, but not the 1st gen Fire is beyond me (except that the Fire's OS has not been updated for some time).

Another curious fact is that pinch and zoom is available for all pages on the Paperwhite with any booktype setting, regardless of image insertion method. The Kindle 3 has some default zoom functions available via the menu, with incremental 5-way controller scrolling in all directions rather than the Virtual Panels' default quarter page progression. So that's a sort of "qualified" yes for that feature.

Cover issues remain consistent on both devices, and there are no Table of Contents menus in any instance. Bookmarks are functional in all three booktypes on the Paperwhite, but not at all on the Kindle 3, even though it retains the default Bookmark and TOC menu links, they're just grayed out and inactive. There are no live text functions, nor active hyperlinks, on either device in any booktype, but font embedding is consistently present.

UPDATE 1/15/2013

The chart has been updated to incorporate the tests I ran on the Kindle eInk devices for ease of reference and comparison. This makes the text in the table somewhat smaller that I'd like, but this is a restriction of the blog format. You can easily use the zoom function on your monitor to increase the text size for better readability, or - since it's a live table and not an embedded image - copy and paste it into a word processor and increase the font size.

UPDATE 2/18/2013

Removed information regarding Guide items, which now receives a more in-depth analysis within the body of the tutorial.

Function

Booktype

Kindle

3

Paper

white

Fire

(Gen1)

HD7

HD9

PC

app

Android

app

1 - Page-Spread

Comic

Children

None

N/A

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

2 - Letterbox Color

Comic

Children

None

White

White

White

White

White

White

White

White

White

Black

White

White

Black

White

White

Choice

Choice

Choice

White

White

White

3 - Virtual Panels

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

4 - HTML Image Zoom

Comic

Children

None

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

"Yes"

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

5 - Cover Image Access

Comic

Children

None

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

6 - Cover Doubling

Comic

Children

None

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

7 - TOC Menu Link

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

NONE

No

No

NONE

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

8 - Bookmarks

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

9 - Live Text Functions

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

Yes

10 - Hyperlinks

Comic

Children

None

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

11 - Font Embedding

Comic

Children

None

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Each of the 11 rows features one functionality element in KF8 that I have tested on the devices and apps listed in the five columns to the right. These are (in order): the Kindle for PC desktop application, a first generation Kindle Fire, the new Kindle HD 7" and HD 8.9" devices, and the Kindle for Android app. Unfortunately, I do not have a second generation Kindle Fire to test, nor a Mac on which to test the Kindle for Mac desktop application. And, of course, as mentioned in the Introduction, fixed layout files cannot be tested in the Kindle for iOS/iPad app, since transferring them in any way I have attempted (Dropbox / DiskAid / Send To Kindle) actually breaks the file. I didn't bother testing these on my Paperwhite or Kindle 3 keyboard model, since comics and graphic novels on these devices are pointless, even though technically they now support the format [see Update below].

As mentioned previously, there are two official book types for Kindle fixed layouts, defined by the appropriately titled "booktype" metadata value in the OPF file (to be discussed in an upcoming section), these being "children" and "comic." But, of course, you can also enter "none" (or simply leave it out), making essentially a third practical booktype. Unlike all the other Amazon-specific metadata values, which determine functionality for a specific listed attribute (such as fixed-layout or orientation, for example), the "booktype" attribute effects a broad range of overall ebook functionality - none of which is detailed by Amazon in their documentation. Hence, this chart. In it, each of the listed functions has been tested with each of the three booktype values set.

In addition, each of the three was tested with the RegionMagnification set both to "true" and to "false," since Amazon states in the Kindle Publishing Guidelines (Section 5.7) that the new Virtual Panels feature (row 3) is reliant upon this setting. This does not prove to be the case, as thorough testing resulted in no change whatsoever in the Virtual Panels functionality with either setting on any device or app. This, of course, may change in future updates, and I will update the chart accordingly at that time. But I have made no note of this distinction in the chart at present, since there is none.

Also, I should point out that in every case changing the booktype made no difference to the functionality of the Kindle for PC app, which appears to simply ignore the setting.

I have entered bold text for the results that stand out as the exception to the rule in order to make the disparity more readily apparent at a glance, and to point out issues with the functionality.

In addition, Appendix A provides no test results for region magnification features (aside from the new Virtual Panels function), as this is contained in Appendix B, and will be dealt with in the latter, more complex portions of the tutorial.

And now the breakdown...

1. Page Spread

A new function in KF8 is the "page-id" spine element which (purportedly) allows for the creation of two-page spreads in landscape mode (either with or without a margin in between). As you can see from the chart, this is only consistently true for the HD 8.9" ('HD9') device, while the HD7 and Android app work correctly with the "comic" booktype value only. In all other cases only one page is shown at a time in landscape mode. Even the Kindle for PC app, which shows an activated two-page button icon, does not actually display two page spreads.

2. Letterbox Color

This refers to the color used to fill in any display space outside the page area, much like the "letterboxing" used in widescreen movies on a 4:3 format television (or iPad). I only tested this because I noticed it was sometimes black and sometimes white and wasn't really paying attention at first to when and where. As it turns out it's only black on the two new HD devices with the "comic" booktype chosen, and white at all other times, with the sole exception of Kindle for PC, where the three standard values of white, sepia, or black are all still available. Not critical, but sometimes one or the other blends better, so it is interesting to know. And given that it is the newest of the Kindle line that sport the black background, this may be an indication of future changes.

3. Virtual Panels

This new feature is apparently a fallback for fixed layout ebooks that have no custom region magnification elements included, and works by dividing the page into four equal quadrants (or "panels") that are zoomed by tapping and advanced in sequential order by swiping (the ordering being based on the "primary-writing-mode" value to allow for right-to-left and left-to-right reading order). Surprisingly, the zoomed page can also then be scrolled around by dragging, and variably resized using pinch-and-zoom, making it a very nice add-on feature for most fixed layout ebooks (in the absence of precisely placed mag zones, that is). As already mentioned, it is supposedly activated by default when the RegionMagnification value is "false," but this value actually has no effect at present: Virtual Panels either work in a particular Kindle reader or their don't, and in most cases they don't. In fact, in only two instances does this currently work: on the HD7 and Kindle for Android app, and only when the booktype is set to "comic." My guess is this feature will continue to roll out until all Kindle iterations have it - aside, perhaps, from the HD9, which somewhat surprisingly doesn't have it; but, then, it doesn't really need it, either, due to its size. However, as you'll see in the next item, you can actually zoom images on the HD9 in certain instances.

4. HTML Image Zoom

This ties in somewhat with the last item, since only one or the other can work. This relates to the HTML <img src="http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheAdv... insertion method for adding background images in fixed layout, as opposed to the <div id="...> method of referencing a CSS background-image url. Amazon recommends the latter, but for reasons I will discuss later, I disagree (in fact, Section 4.2.3 of the Guidelines says it's a requirement, because "HTML images interfere with Region Magnification," which is demonstrably untrue). The important factor here, however, is that the <img src="http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/TheAdv... method allows the user to zoom a background image by double-tapping on it anywhere that it's not overlaid by text or Tap Targets, while the CSS method does not. This allows for zooming and scrolling entire background images (minus any text overlays), which until Virtual Panels was the only way this could be done. However, since the Virtual Panels function effectively creates a Tap Target covering the entire page, where that feature is active this one cannot be, since the background image cannot be tapped (the images still appear correctly using the HTML insertion method, so there's no issue where the image's placement is concerned). That said, assuming the RegionMag "true/false" value will eventually work as stated, you will then be able to chose one or the other, so this information will still theoretically be relevant. As seen in the chart, however, it's not just the Virtual Panels factor that determines whether <Img Src> Zoom works or not, since in no case does it work with the "comic" booktype value chosen. But since this is - at present - the only place where Virtual Panels works, in all other case (aside from Kindle for PC) this image zoom method works. An important distinction to make between Virtual Panels and the HTML "img src" method is that that latter only magnifies the actual background image (which is sometimes desirable and sometimes not), while Virtual Panels zooms the entire page, including text overlays, making it more like the iPad's pinch and zoom feature than Kindle's standard Panel View. (For an additional difficulty with Virtual Panels, see number 10. Hyperlinks below.)

5. Cover Image Access

6. HTML Cover Doubling

These two go hand-in-hand, and it all really comes down to one thing: Amazon flat out got it wrong on this one. In Sections 4.2.4 and 4.3.7 of the Kindle Publishing Guidelines Amazon either "requires" or "recommends" (depending on the section) than an HTML page containing the cover image be included in fixed layout files, even though in Section 3.2.3 they unequivocally state that you are not to do this because the cover image may appear twice - which is, in fact, exactly what happens in every instance. They then contradict themselves further by providing (in Section 3.2.3) one exception to this rule, in which case you must enter the linear="no" value to the spine entry for this element (the underlined element being "mandatory"); but then in the later two sections they state that the same value must be set to "yes." All this contradictory information can be cleared away easily by the facts: if an HTML cover is included, the cover image always appears twice. "Cover Image Access" simply refers to whether you can swipe back to the cover once you have moved forward into the book, and was tested in conjunction with the cover doubling issue to see how pervasive the latter was. In only one instance are you not able to return to the cover (even the HTML one) by swiping (or tapping), which is on the HD7. You can still access the cover via the menu link on this device, when again you will be presented with two consecutive covers, one JPEG, one HTML, but you cannot swipe back to it once into the book, whereas on every other device or app you can do so, and there will always be two consecutive cover images in a row. Therefore, there is simply no reason whatsoever to include an HTML cover, and several good reasons not to.

7. TOC Menu Link

Since we're on the subject of menu links, here's another issue to consider. For some unfathomable reason, Amazon has decided to remove the "Table of Contents" link from the default "Go To" menu on the new HD devices. And not only that, but on ebooks with the "children" booktype value the entire "Go To" menu is inexplicably missing. Gone. Completely absent. No links to the cover, the beginning, or any other internal links. Apparently they think readers of children's ebooks don't use menus, nor that comics should ever have a Table of Contents - which, granted, they often don't, but lengthy graphic novels could certainly benefit from one. Perhaps they thought removing it was better than including a Go To menu where all the links are non-functional, but even so, removing the option is a bit reactionary, especially considering that the menu is still present and fully functional in all other Kindle readers.

8. Bookmarks

9. Live Text Functions (inc. Notes, Highlights, Search, & Definitions)

Of all the ebook functions that should never be disabled, these are the ones. If any feature promotes digital reading over print it's the ability to interact in highly useful and informative ways with the text. Being able to annotate, highlight (without ruining the book!), instantly search the entire text, and get the meaning of any word with just a tap of your finger - not to mention adding as many bookmarks as you like - are just some of the wonders that set ebooks apart. And yet Amazon has somehow decided (intentionally or inadvertently) that these features are not needed in children's books or comics. For with either of those booktypes entered they are all disabled - with the single exception of bookmarks in "comics" on the Android app. And mind you, this is not a fixed layout issue, not some odd quirk in the fixed layout Kindle code, since when you delete the booktype value altogether (or enter "none") all this functionality is back, with the fixed layout intact. It did not used to be this way for the "children" booktype, which originally retained live text functions, although "comic" did not have them from the very first. However, disabling them for children's ebooks only happened recently. I have ranted long and often on this here before, so I won't go on at length now. To me, there is simply no justification for this decision, since decision it must be, as there is no logical reason why a manufactured metadata value would have any effect it was not designed to have, unless Amazon is just not paying attention, which I find unlikely.

10. Hyperlinks

Somewhat similar to the live text problem is the issue of interactive links, both internal and external. Here there is fortunately only one disparity, which is on the HD7, where the "comic" booktype completely disables all text hyperlinks, none of which work at all. External hyperlinks are still blue, but non-active. This is clearly related to the Virtual Panels feature, rather than live text functions, since in all but this one instance hyperlinks work correctly even where live text is disabled. But as Virtual Panels currently only work on the HD7 and the Android app, it is possible that this feature is somehow interfering with the links, since Virtual Panels overlay the entire page with a tap target. However, given that the Android app is not effected, it's uncertain what is actually causing this. My concern is that as the Virtual Panels function is rolled out across devices the loss of hyperlinks might become a widespread problem. Hopefully the HD7 issue is an aberration, but it's 50/50 at the moment, so we'll just have to wait and see. Fortunately in most cases this is not an issue at present (which is little comfort to owners of a brand new HD7).

11. Font Embedding

This was just a standard test that I'm happy to report has essentially become unnecessary, as font embedding is now supported by all tested Kindle devices and apps. This was not the case just a few short years ago, when Kindle reflowable files did not allow custom fonts. Now they do, and KF8 has supported them from inception, and happily continues to do so. I include it because it's just good to know. And it's always nice to end on a positive note.

CONCLUSION

These are all considerations each ebook designer must weigh and make decisions on, based on their project and target audience. Bear in mind that digital publishing is still in its infancy, and in a state of great upheaval at the moment. All of this will settle out in time, but for now we have to be aware of what is possible and what is not, and try to stay abreast of any changes (which are numerous and often). Already this chart shows the great disparity between a single year's development of the Kindle Fire line: in at least half the features listed there is a difference in functionality between the 1st generation Fire and the latest models.

My biggest issue continues to be the lack of support for live text when either booktype value is entered, making my clear recommendation not to add one. The only functionality that will be lost by doing this are the two instances where Page Spread works with the comic value entered, but not when it is absent - these being the HD7 and Android app - as well as Virtual Panels on the same two readers. But since these features are hardly universal, being not yet present in any other case (aside from the HD9 where Page Spread is functional regardless of booktype), there is very little incentive to add a booktype value. The primary exception, unfortunately, is that only the "comic" booktype allows images of up to 800kb in size; otherwise, you're restricted to 256kb for fixed layouts, which can be a significant consideration with the advent of HD displays. Of course, this may all change (and probably will) over time as new updates are rolled out. But one cannot plan current work based on future possibilities. One must take what data is available today and use it to inform your present efforts.

As mentioned, I will update this chart regularly, and note the changes made at the bottom of the post. If a large number of changes are suddenly made - say, when a new line of devices arrives - I will do a new post and reevaluate the situation.

And by the way, if anyone has a 2nd generation Fire or a Mac with the Kindle desktop app and can test any of these features I would very much appreciate the information. I would love to add it to the chart for reference and will gladly give you ample credit and provide a link, both here and in the published ebook. For that matter, if any of your own testing contradicts what I have listed here, please let me know so I can look into it further. Comment below or send an email to scot(at)fantasycastlebooks.com.

UPDATE 1/6/2013

Just for the sake of being thorough, I went ahead and tested the eInk Kindle 3 and Paperwhite devices. And while I won't bother to include the data in the chart above due to space restrictions, I will point out the primary data points here.

First, and most surprising, is that the Paperwhite actually supports Page-Spread in all booktypes. This is accessed via the menu's "View in Landscape" option, since the Paperwhite has no internal orientation sensor. Just as interesting is the fact that, while the Kindle 3 does not support Page-Spread, it does default to landscape orientation for the booktype values "children" and "none" (though inexplicably showing only one page at a time), while for comics it reverts to portrait orientation. There is no way to change the orientation from the Kindle 3 menu. Letterbox color is white in each instance.

Equally surprising is support for Virtual Panels on the Paperwhite with "comic" or "none" booktypes (but not for children's books). This is, therefore, the only device that currently does so with the booktype absent, and only the second device that supports it at all. Why the eInk Paperwhite would support this function, but not the 1st gen Fire is beyond me (except that the Fire's OS has not been updated for some time).

Another curious fact is that pinch and zoom is available for all pages on the Paperwhite with any booktype setting, regardless of image insertion method. The Kindle 3 has some default zoom functions available via the menu, with incremental 5-way controller scrolling in all directions rather than the Virtual Panels' default quarter page progression. So that's a sort of "qualified" yes for that feature.

Cover issues remain consistent on both devices, and there are no Table of Contents menus in any instance. Bookmarks are functional in all three booktypes on the Paperwhite, but not at all on the Kindle 3, even though it retains the default Bookmark and TOC menu links, they're just grayed out and inactive. There are no live text functions, nor active hyperlinks, on either device in any booktype, but font embedding is consistently present.

UPDATE 1/15/2013

The chart has been updated to incorporate the tests I ran on the Kindle eInk devices for ease of reference and comparison. This makes the text in the table somewhat smaller that I'd like, but this is a restriction of the blog format. You can easily use the zoom function on your monitor to increase the text size for better readability, or - since it's a live table and not an embedded image - copy and paste it into a word processor and increase the font size.

UPDATE 2/18/2013

Removed information regarding Guide items, which now receives a more in-depth analysis within the body of the tutorial.

Published on February 18, 2013 12:02

February 14, 2013

Kindle Fixed Layout Tutorial - Part 7

<!-- eBook Content Metadata -->

This section can be just a few short lines giving only the bare essentials of title, language, and identifier (the only three that are required), or add a host of other information that can be useful for identifying and indexing your title. In this, more is always better, as individual systems can ignore non-relevant portions, but cannot make them up if they are not provided. Furthermore, much of this information is searchable in online catalogs, such as Amazon's search engine and the Google Play bookstore, helping potential readers find your work.

There are 15 elements, known as "properties," in the standard Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES). These are (in alphabetical order):

Contributor

Coverage

Creator

Date

Description

Format

Identifier

Language

Publisher

Relation

Rights

Source

Subject

Title

Type

Not all of these are relevant to all ebooks, nor were they created specifically for ebooks, but rather for electronic publications in general. The purpose of using a standard reference set such as Dublin Core is so that everyone who might reference or add to the data pool will be using a common vocabulary.

To see the official documentation, visit the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. For the IDPF's ePub 2.0 specification set, see Section 2.2: Publication Metadata.

I will describe each property - grouped into a more or less logical order - along with their modifiers and options, but you can also find a complete table of all fifteen in Appendix C of the ebook tutorial, along with concise descriptors and reference links (included at the end of this post).

<title>

The <dc:title> attribute is one of three required elements in any ePub-based ebook, Kindle included. This is the title that will appear on the Home screen or Kindle Bookshelf in list view. You can add more than one, using separate entries, either for subtitles or series/volume titles. But the primary title by which you want your ebook to be listed must be given first. Simply insert the title of your ebook between the angle brackets, like so:

<dc:title>YOUR TITLE HERE</dc:title>

There is no opf modifier to designate a given title entry as the series title or a subtitle, so the order in which they are listed is critical. You can enter it all as a single title, or as separate entities, but whatever is in the first entry will be how the book is listed anywhere that it appears.

You will also be allowed to enter additional title information during the upload process to KDP, including Series titles and/or Volume numbers. But be sure to include it in the metadata section, so that no matter where the ebook goes, the information will go with it. For example, it may be sold to libraries or academic institutions, or find its way to secondary resellers if used ebooks become a legitimate market in the future. And, of course, you want it to appear correctly in the reader's own device library.

As a side note, you should be aware that ebooks will only appear on the Books tab of the Kindle device after they are downloaded from Amazon. Otherwise, they are considered personal documents and will appears on the Docs tab, even when you put them in the Books folder on your device. This is unfortunate for those who wish to sell ebooks directly to their readers, but you cannot change it, so don't try. A metadata entry called "CDE Type" with the content value EBOK (or EBSP for samples) will be created during the KDP upload process, but it is ignored if added manually. Incidentally, Calibre will add the EBOK entry during its conversion of reflowable ebooks, but unfortunately it cannot yet convert fixed layout files correctly.

<creator> <contributor>

You are required to include a title, for obvious reasons, but not an author or other creator, as works can be anonymous. There can, of course, also be multiple creators of a work, and each of these should be entered as a separate entity. The OPF spec adds two optional attributes to the <dc:creator> element that greatly aid with this and extend its value as a data attribute. The first of these is file-as, which allows you to specify the last-name, first-name sorting order for creator names, as in:

<dc:creator opf:file-as="Last, First">First Last</dc:creator>

If you leave this out your ebook will be listed under your first name in many catalogs and databases, such as the Calibre library.

The second opf modifier is the role attribute, which has a wide range of values to specify the exact function of each creator or contributor to the work, including author, illustrator, editor, and many others. In addition, there can be multiple entries of each.

These are entered using a three-character code, such as "aut" for author or "ill" for illustrator, as seen in the template metadata. For a complete list of the 223 role values and their 3-character codes, along with a description of each role's function, see the MARC Code List for Relators.

<dc:creator opf:role="aut">Your Name</dc:creator>

In the unlikely event this extensive list does not contain a value for a particular function utilized in the production of your work (the required skills for creating ebooks are expanding rapidly, after all), you can add generic contributor elements using the "oth" value for any others whose roles remain unspecified.

All role values can be used for both the creator and contributor elements, each of which are entered in the same way. The distinction between these is that creators are the primary producers of the work, such as the author or an artist of a heavily illustrated children's book or comic, while translators or designers who contribute to the work should be listed using the <dc:contributor> element. In many instances this might be a purely arbitrary distinction, but in general those who produce the work are creators, and those who help to shape the work are contributors. But there is no hard and fast rule for usage, so use your best judgment.

<publisher>

The publisher of a work is defined as the entity responsible for making the publication available in its present form. This is somewhat less obvious than one might think for self-published books, for the simple reason that the legal "publisher of record" is the entity to whom the assigned ISBN is registered, and not necessarily the person or organization on whose book it ends up.

For example, if you publish your ebook through Smashwords, they will provide you with a free ISBN. However, contrary to popular belief, you will not be a "self-published" author, since the publisher will be listed as Smashwords at every retail vendor who carries your ebook. This is a technicality for all intents and purposes, since you will have "self-published" your own work. But you are not the publisher, Smashwords is.

Conversely, if you do not provide an ISBN when uploading your ebook to Amazon (or Barnes & Noble or Google Play, who do not require one), they will assign their own "unique identifier" to your work (an ASIN in the case of Amazon), but you will still be listed as the publisher.

This might seem a fine idea from a financial standpoint, since ISBNs do not come cheap (at least in the United States: in Canada they're free). However, this makes cross-referencing your works vastly more difficult for archivists and collectors, not to mention librarians who might want to buy your ebook. With an ISBN assigned to the ebook edition of your book (it cannot be the same one used for a print edition, if there is one), your title can easily be found anywhere that it is listed. In addition, all sales for that title will be aggregated in bestseller lists, whereas this is not always the case for titles with a different number assigned at every vendor.

The sole reason I point this out here is that simply entering your personal or business name into the publisher metadata entity does not make you the publisher of record - legally, at least, which may become an issue down the line if you decide to sell your Smashwords published ebook to another publisher. It is always best to have an ISBN assigned to your work, and for legal reasons it is always best to have it registered to you.

<date>

The opf spec adds the event attribute to the <dc:date> element, allowing you to specify the nature of a given point in time, such as the date of creation, publication, modification or revision, of which you can include one, all, or none. There is no defined set of date values, so you can enter any that you feel might be useful, such as an entire revision history, or just the date that it was finished. Only the first one will be recognized by Kindlegen during conversion, but the rest will be retained in the internal metadata.

<dc:date opf:event="publication">2013</dc:date>

The date element is optional (though recommended by Amazon), and if used you can enter just the four-digit year as shown and call it good for most books. However, if you're working on a periodical or other timely content (or simply like to be precise), you may want to include the month and day as well. If so, you must use the year-month-day format of YYYY-MM-DD in order to conform to ePub standards.

<rights>

A statement of your rights within the metadata is recommended, though not required. This can be anything from a simple "All Rights Reserved" (or creative commons, public domain, or whatnot), to a full assertion of your Intellectual Property Rights in different territories and/or under various conditions (as, for example if you're doing translations into different languages, or have retained the ebook rights but not the print edition rights). In most cases, if you're getting this involved you'll want to consult a literary agent or legal representative who knows publishing law.

A reference to the system of protection should be included along with any assertion of rights, such as "Copyright" or "Trademark" for print and graphic elements. Thus, a standard concise statement of universal rights might be:

<dc:rights>© Copyright YYYY - All Rights Reserved</dc:rights>

Within the XML code framework of the OPF file you should include the full word "Copyright," and/or use a universally recognized string to stand in for the © symbol, as it may not be recognized by reading systems throughout the world. Three standard, code-based alternatives are given here:

Character

Decimal

Hexadecimal

Named Entity

©

©

©

©

<language>

The second required element is at least one entity that identifies the primary language of the content. This should employ the standard RFC 3066 Unicode language identifiers, using a base two-letter code, either alone or with a secondary string, or "subtag" for a language variant. So, for example, English can be either plain EN, or EN-US for United States dialects, or EN-GB for British idioms, or any of a host of others. Values are not case-sensitive, so en, En, and EN are all valid entries.

<dc:language>En-US</dc:language>

Generally it is best to avoid using subtags unless it is clearly relevant to the work, as it inherently alienates speakers of related languages for which the work is equally accessible. On the other hand, readers might be interested to know that they are in for British slang when diving into Harry Potter for the first time.

You can also include more than one language identifier if more than one language is used in the work, as are found in dual-language translations, or where large portions are given in another tongue, such as Latin passages in a history text. It is not necessary to include a language identifier for single foreign terms scattered throughout a book, unless it is required to know the language for comprehension of the content, or where are a large number of foreign terms have been inserted.

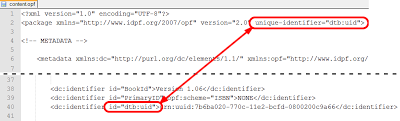

<identifiers>

The third and final element you are required to include is at least one unique identifier. As mentioned in the introduction to the OPF file earlier, there must be one identifier with an id value that matches the value of the unique-identifier element in the header declaration, and this is where it goes.

An identifier is a reference to the publication from a given system of documentation, the most common of which is the International Standard Book Number (ISBN). However, it can be any string of data that is specific to this particular incarnation of your work, though preferably one drawn from a formal identification system, such as a Globally Unique Identifier (GUID), Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), or Digital Object Identifier (DOI). No particular identifier schema is required, nor has any been endorsed by either Dublin Core or the IDPF, although, of course, an ISBN is universally recognized as the standard for publications.

Multiple identifiers can be used instead of, or in addition to, an ISBN, but as mentioned, one must be the globally unique identifier. This is specified by an XML id tag that matches the unique-identifier value in the header. The value itself can be any descriptive term or key phrase, such as the common "BookId" or "book-id" employed both by Amazon and Apple in their samples. The value is case sensitive only in that its two entries must match exactly. Otherwise the id value is essentially arbitrary, functioning merely as a label for the data string, although, of course, you will want it to make sense and clearly describe the contents of this particular identifier.

In addition to the id value, the OPF spec adds an optional scheme attribute that allows you to name the specific system of authority that generated or assigned the data used as the identifier. Here is where you would enter "ISBN" or "DOI", or whatever the source of the data string may be. Here again, the OPF spec does not endorse or restrict you to any given identifier scheme.

In the templates I have included three identifiers, each with a particular function. The first of these is labeled "BookId" and is used to identify the Version number of the ebook, since there is no other means of doing so within the metadata, aside from a "revision" event in a date element. It is good practice to include a version or edition number on the copyright page within the ebook itself for the reader's reference, but in order for electronic databases to recognize a revised edition, you will need to include it in the metadata.

The second line in the template is given only as an example of how to enter an ISBN, since the template itself does not have one, being free. You would simply enter your ISBN number between the angle brackets, where it now says NONE. The id that I've entered for it here is just an arbitrary label, and has no actual value. But I could make this the unique identifier simply by changing either the id value here or in the header so that they match.

The final entry is the one I have used as the template's globally unique identifier, and as you can see it matches the unique-identifier value in the header declaration.

Here I've used a standard 32-character data string known as a UUID, or Universally Unique Identifier, which contains an encoded timestamp based on the moment and node location where it was created. These can be generated at no cost on many websites, including UUIDGEN, where one is automatically created the moment to land on the page. The string itself is the portion after the prefixed urn:uuid: tag. The "urn" element stands for Uniform Resource Name, which is a predecessor of the URI and URL.

The dtb:uid value of the id will be found in the metadata section of the NCX file as well, where it should match this data string as well (if used), although it is not strictly necessary. I'll discuss that further when we get there.

The UUID is particularly useful in that it can be decoded to discover the exactly moment and location of creation, but looks like utter gibberish otherwise. Each time you update the ebook's content, however trivial, you should alter this data string, as well as the version number if used, in order to allow users (or yourself) to identify the particular version they are holding.

<type> <subject>

By using the type element you can add category data such as whether the work is Fiction, Non-Fiction, Poetry, etc., and/or a specific genre or classification, such as Science Fiction or Art History. You can also include functional descriptors for such works as Almanacs and Working Papers. The values here are limitless, but should use commonly recognized terminology.

The subject element, on the other hand, is used to define the topic or subject matter of the content itself. This is where you would add Library of Congress classification codes, BISAC Subject Headings, or others such as those used by Amazon to categorize their entries (many of which will be drawn from these metadata entries). One reason you're adding all this extra information is precisely so that retailers can add it to their product pages. Adding it here facilitates the quick and accurate transfer of metadata concerning your work, and this is your chance to make sure it's right.

The template provides half a dozen examples of subject headings that might be appropriate for such a work, drawn from the BISAC listing. You can add as many as you like, and as always, more is generally better than too few.

<description>

This is where you place the back jacket blurb or other descriptive content that tells the reader what the book is about, with the intention of enticing them to read it. Anything you might desire a potential customer to know could go here, including reviews, extracts, or a table of contents to let them know exactly what's included.

Aside from the content of the book itself, this is the most important piece of writing you will do with regard to your published work. Give it some serious thought and apply your finest craftsmanship, as it will show up all over the Internet, on every ebook retailer and social reading site, as well as book review blogs and library lending catalogs, and once it's there it's there for good.

<format>

One other tag you might include is format (Kindle in this case, but ePub or iBooks or whatever is appropriate otherwise). This might seem redundant since you've got the ebook right there in front of you, but not everyone reading this data will, and it's one more way this specific iteration of your work can be identified. For example, a library may be looking at a metadata listing in search of a particular format to include in their catalog, and other general ebook retailers will want to identify the format for their customers before selling it to them via whatever systems are put in place down the line as ebooks become more common.

There are a handful of other elements that you can add in order to expand upon or define further aspects of your work, such as its sources or relation to other works. Following is the Appendix C table containing the complete list and their definitions.

Before moving on to the next section of the OPF, be sure to close the metadata section by using the backslash </metadata> tag. It's also a good idea to check through your list of entries to be sure that they're all closed as well.

DUBLIN CORE METADATA ATTRIBUTES

Property

Description

contributor

Used for persons making contributions to the publication in a manner that is secondary to the role of creator, such as editors, translators, or designers. The significance of the role is arbitrary, as, for example, an illustrator may be a primary creator or a secondary contributor. The semantics and attributes are the same as those used for creator.

coverage

Identifies the spatial or temporal topic of the publication, such as the geographic applicability of a resource or jurisdiction under which it is relevant. Spatial coverage refers to a physical region, using place names or coordinates, while temporal coverage specifies a time period covered by the content, such as Neolithic or Elizabethan. See the DC Coverage Element for further descriptive commentary.

creator

The primary authors or creators of the publication, whether person, service, or organization. A separate element should be used for each name, and these should be given in the order to be presented to the reader. The OPF 2.0 spec adds the optional attributes role and file-as. See MARC Code List for Relators for complete list of the 223 role values and their 3-character codes, along with a description of each role's function.

date

Any relevant date(s) for the publication, such as creation, publication, and/or revision. The OPF spec adds the optional event attribute to define these temporal points, using standard defined Date & Time Formats (i.e. YYYY-MM-DD), of which the 4-digit year is required (this is not required by Amazon, although it is recommended). A full set of event values has not been defined.

description

The description(s) of the publication content. This may include, but is not limited to, an abstract, table of contents, graphical representation, or free-form account of the content. It is often used to provide the sales copy for online retailers, as well as book reviewers and bloggers.

format

The media-type or physical dimensions of the publication. This might also include such factors as duration, software version, or operating system, along with hardware required to use the resource. The recommendation is to use a MIME type.

identifier

Required. One or more unique references to the publication within a given context, such as ISBN, DOI, URN or URI. The OPF spec provides an optional scheme attribute that names the system or authority that generated the identifier, although no specific schema are endorsed or defined as required. One element must be defined as the unique-identifier, with an id value specified.

language

Required. One or more language identifiers, with optional region subtag, such as en-us for English as spoken in the United States, or fr-ca for Canadian French. Avoid using subtags unless necessary. The OPF spec requires that these conform to RFC 3066 or its successor.

publisher

The publisher(s) of the resource, defined as the entity responsible for making the publication available in its present form, such as a publishing house, university department, or a corporate entity. This is generally the entity to whom the ISBN is registered (the "publisher of record").

relation

Identifies related resources and their relationship to the current publication. Used to express linkages between entities, such as soundtracks to a movie, or reference works dependent on support materials. There is no standard schema adopted.

rights

An assertion of the rights held by the publisher/creator with respect to the publication and its content. A statement of Copyright notice should appear, including Intellectual and other Property Rights, as well as links and/or references to the rights protection system or service employed.

source

Identification of primary or secondary resource documents or publications from which the current publication is derived, either in whole or in part, including necessary discovery metadata.

subject

The topic or subject matter of the content. This can be anything from one or more keywords, classification codes such as those provided by the Library of Congress or BISAC's Subject Headings, or any descriptive phrase. There is no schema standardization provided.

title

Required. There must be at least one title for the publication, although multiple titles and/or subtitles are allowed, such as for series or volumes. The first one listed should be the primary title.

type

The nature or genre of the publication. Includes terms for general categories (such as Fiction or Non-Fiction, etc.), genres (such as Young Adult, Fantasy, Romance), as well as those describing functions (such as Technical Report or Dictionary). To describe the physical medium or coding mechanism of the resource, use the format element.

Published on February 14, 2013 21:32

February 9, 2013

Kindle Fixed Layout Tutorial - Part 6

<!-- Kindle-Specific Metadata -->

The first group of attributes in the metadata section are those that pertain specifically to Kindle fixed layout ebooks (see end of post for a complete list), and the first of these is the one that makes the layout fixed:

<meta name="fixed-layout"content="true/false"/>

This tells the Kindle reading system to display the content exactly as defined in the html and css files. This radically alters some basic functions of a Kindle reader, foremost of which is the disabling of the Settings menu (Aa), where Font size and style, margins, and background color options are contained. That means, of course, that none of these can be changed by the reader, so it's up to you to make the content legible. In many cases, that's where Region Magnification comes in. But good typography will go a long way to presenting your work in the best light.

The only real option here for the content value, of course, is "true", since if you're entering "false" then you are not making a fixed layout ebook, and nothing else that follows in this tutorial will apply. Hence, this is a required attribute for Kindle fixed layout ebooks, and the required value is "true".

Note that the actual data in the Kindle section is given in quotes as a content value, rather than between angle brackets, as in the standard metadata section.

The ordering of metadata elements in the OPF, by the way, is entirely up to you, as long as they are all entered within the <metadata> </metadata> tags. I prefer to put the Kindle ones first, since they are unique to this format, while the rest belong to the standard ePub structure that is found in virtually every modern ebook file.

Next up is the orientation function:

<meta name="orientation-lock"

content="portrait/landscape/none"/>

This is the attribute that determines if the orientation is fixed as well as the content, or if the pages are allowed to reorient as the device is rotated to either a horizontal or vertical position. Options here are "portrait", "landscape", or "none", which is the one that allows auto-reorientation. Another way of selecting "none", of course, is just to leave the "orientation-lock" attribute out altogether.

A new features in KF8 called PageID allows for two-page spreads in landscape orientation (which will be discussed in detail shortly), but at present it is not universally supported across all Kindles, so that in many cases only a single page can be viewed in landscape rather of two. This will likely change in future updates, but it's something to take into consideration at the moment when planning your layout.

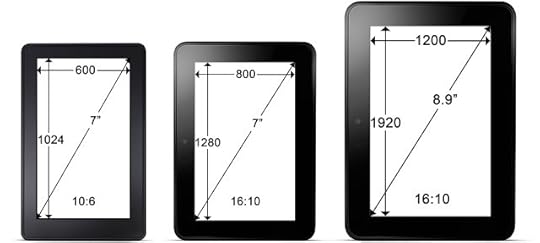

Additionally, the widescreen aspect ratio of the Kindle Fire line makes auto-rotation less ideal than the 4:3 ratio of the iPad, which retains a larger page size in landscape than the Fire. Only the Fire HD 8.9" has a display size large enough to make two-page spreads effective, but designing ebooks for a single model ignores too many potential readers to be a serious consideration. I am in hopes that Amazon will eventually transition to 4:3 ratio displays, but for now we have to work with what we've got. That said, it's probably best to plan for single page displays, whether portrait or landscape in dimension. Enter your chosen orientation as the content value here.