G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 20

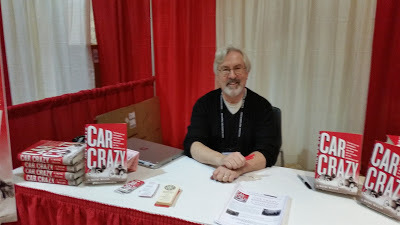

April 16, 2016

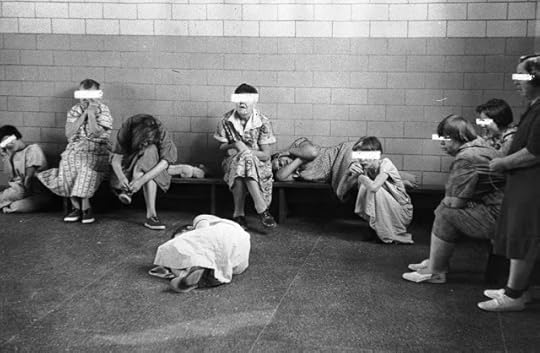

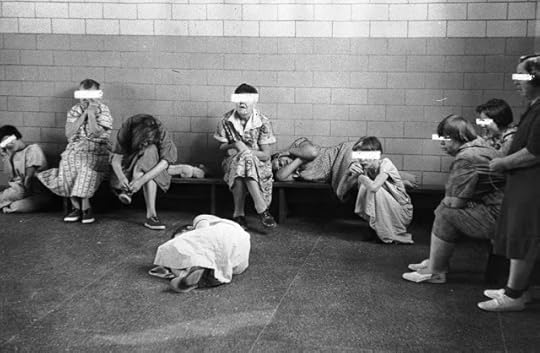

A week at the old Institute of Mental Health, a now-closed state asylum

From the archives...

Inside the I.M.H.

G. Wayne Miller

Publication Date: November 10, 1985 Page: M-06 Section: MAGAZINE Edition: ALL

Rhode Island officials today are proud of the Institute of Mental Health, which not very long ago was considered a public disgrace. Since it was opened, 115 years ago this month, officials say, no reporter has ever been allowed to live inside the IMH with the purpose of publishing what he saw. In September, after being assured that the confidentiality of patients would be protected, IMH administrators agreed to let Journal-Bulletin reporter G. Wayne Miller spend four days and three nights on AM-9, a locked ward. Both patients and staff were told in advance who he was, and what he would be doing.

This is his report.

Part one of two parts.

TUESDAY, 10:10 A.M.

I've just been introduced to Roger, 35, who has nothing at all to say to me. Roger is unshaven. His eyes are bloodshot. His hair is dirty and short, like a British hoodlum's.

Roger is not a happy man. His mental illness, known as a bipolar disorder, has flared again, making him angry and tense. Earlier in the week, he got roaring drunk and threatened to beat up his elderly parents; the police brought him in handcuffs to the IMH. He wants out. "Roger's the name, escape's the game," he keeps repeating.

At the moment, Roger is sitting across from me in the conference room of Ward AM-9. In terms of the quality of its treatment and the caliber of its staff, AM-9 is considered among the institution's most progressive wards. The challenge on AM-9 is to take very sick people, quickly make them better and then discharge them as soon as possible.

Roger sits at the conference table, a sly grin on his face. With him are a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, an attendant, a nurse. Their job during this meeting is to pump Roger for information so that they can begin shaping a treatment plan. One of his problems is he won't take medication to control his disorder. Dr. Aimee Schwartz, the psychiatrist, is hoping that Roger will agree to try a new prescription.

During the interview, Roger skips back and forth between subjects. He lives in a tough neighborhood, he says. Takes drugs sometimes. Fights. Has a habit of abusing his body. "I almost got murdered. I have a brain concussion right now. I got a bad heart, a busted-up ear, scraped knuckles."

According to the report Dr. Schwartz has, Roger got into an argument with his parents over a pack of cigarettes. What the issue was, exactly, is unclear. The report also says he may have been hearing voices.

"Lies]" Roger says. "I'm here under false pretenses. I got kidnapped. Shanghaied."

"Why would they lie, Roger?" Dr. Schwartz asks.

"I guess they say I'm crazy."

"Are you?"

"I knock on wood I ain't."

10:30 A.M.

Roger's review is over, and now activity has shifted to the day room, where staff and patients congregate during their free moments.

Ann, a chronically depressed woman in her 50s, sits in a chair, her head buried in her hands. A chaplain comforts her. Rose, also depressed, also middle-aged, sits alone, staring blankly. For days, the staff has been unable to coax so much as a single word out of her. Other patients are more upbeat this morning. Craig, 42, is talking with a psychologist about his progress, which has been substantial. Jean, 20, is on the pay phone to her parents.

Without fully realizing it, I keep looking over my shoulder to see if anyone has crept up behind me.

And it's not just my very real fear of Roger, who strikes me as a 170-pound pressure cooker with the lid about to blow off.

No, it's the history of the IMH, known to a century of Rhode Islanders simply as Howard, after the Cranston farm that was here before. It's the weight of all those stories people tell about what goes on inside here, or what they think goes on. Stories about assembly lines for horrifying electric-shock treatments. About the poor souls subjected to the tortures of lobotomies and cold-water therapies. About the notorious back wards, where people were treated, and consequently acted, like caged animals. In short, about the state's very own "loony bin," a complex of brooding Victorian buildings where entire lifetimes were swallowed by darkness.

Since November, 1870, when it opened as the State Asylum for the Incurable Insane, the IMH has been the state's public psychiatric hospital - the temporary or permanent home for generations of mentally ill Rhode Islanders. In the last two decades, the state has moved hundreds of patients into group homes and community residences. Hundreds of others, who once would have been locked away, are now treated in the community. Today, only the sickest mentally ill go to the IMH, almost always when they are in a state of crisis. Most spend only a few days inside the hospital.

For the last two or three years, state officials have been singing the praises of the IMH: how the back wards have all been closed, how the institution has emerged from the Dark Ages to become a humane, compassionate place, where people get better - not abused.

I'm here to see.

10:45 A.M.

I'm still sitting in the day room.

Roger, who disappeared for several minutes, makes his reappearance dressed in a bathrobe. He is clean, having showered with Kwell, an antiparasitic chemical that kills body lice. He is unwilling to take his new medication. Under Rhode Island law, it would take a court order to force him; there is, as yet, no such order. He paces the hall, continuing to froth about being "shanghaied."

I wonder if Roger will approach me. He doesn't.

AM-9, located in the Adolf Meyer Building, is what is known as an admissions ward. It is affiliated with community mental-health centers in Warwick and Barrington. Under this arrangement, patients admitted to the IMH from the East Bay and West Bay areas come directly to AM-9, are treated here and eventually are discharged from here. In this way, community and hospital can stay in close touch, the idea being that patient care improves when continuity is ensured.

It is not a dreary place, this ward; neither is it especially cheerful. Because the doors are always locked, because the windows are covered with knifeproof safety screens, because there is a seclusion room at one end and restraint devices in a nearby closet - because needles and tranquilizers appear during emergencies, and pills are handed out every few hours - it is hard ever to forget just what this is: a ward in the state psychiatric hospital.

Ward AM-9 is essentially one long corridor with rooms off it. The day room, about three-quarters of the way down the corridor, predominates. It is about the size of a classroom, with seven large windows facing New London Avenue. The walls are blue. Hanging on them are bulletin boards and some Woolworth's art: framed reproductions of a ship, flowers, a duck. Thirty-five wood-frame upholstered chairs are here, along with two coffee tables, two end tables, a color TV and two card tables with inlaid chess- and checkerboards. All of the furniture is new. The chairs are comfortable. The TV gets good reception.

Off the day room is the nurses' station, a glass-enclosed booth where records and medications are kept. At the southern end of the ward are two women's bedrooms, an examination room and a seclusion room, where the most agitated patients are sequestered. The seclusion room has one bed, one window, an outside lock and no inside doorknob; inside doorknobs were removed from all IMH seclusion rooms last year after a patient, using his belt as a noose, hanged himself from one. A long corridor stretches north from the day room. Off the corridor are men's bedrooms, shower rooms, bathrooms, a kitchen. All of the bedrooms sleep two people, except one that sleeps four.

11:10 A.M.

In the day room, a couple of patients are exercising, stretching their arms, bending over to touch their toes. Mild, all of it.

Roger finally drinks a dose of lithium, his new medication. It has no immediate effect, nor will it; it can be days, even weeks, before some drugs take hold. Despite his abrasive personality, I'm beginning to feel a touch of compassion for Roger, a man whose lot in life clearly overwhelms him. Because of his illness, he has been unable to hold a steady job. He has few, if any, friends. Here on AM-9, when he thinks no one is watching, his posturing and combativeness subside and Roger sits forlornly alone, like a grammar-school kid who doesn't have anyone to play with.

NOON

Down three flights from AM-9 in a basement activity room, most of the ward's patients have gathered to prepare lunch, under the guidance of Noreen Altham, an activities coordinator. Numerous activities and therapy sessions are available weekdays: music, dance, drama, group discussions. Along with counseling and medication, these sessions help with recovery.

Ann has her good days, but today is not one of them. She sits in a chair sobbing, saying, "I'm sick to my stomach. I can't do it." In the kitchen, the remaining patients set about preparing the food. On today's menu: BLT sandwiches, fruit salad and Hawaiian Fluff, a pineapple-and-whipped-cream dessert that is Noreen's creation. There is a lot of joking and laughing as the patients become absorbed in their work.

"The idea is to give them a chance to mingle, make some decisions," Noreen says, "see if they're able to follow through on tasks, relate to one another, take directions. Most people on admissions wards hold back. They're fearful. The most important thing for them is a trustful environment."

2:55 P.M.

After a group therapy session during which we discussed our feelings (What makes us happy? Sad? What scares us?), we have returned to the day room.

The door opens and a man is brought in by two policemen. Lloyd is tall, blond, in his 20s. He wears a headband and a T-shirt. Like Roger, he has threatened his parents. He has also been smoking marijuana, a substance that doesn't mix well with his medication. Once again, I feel like all hell is about to break loose. The second that door opened, the tension level on the ward went through the ceiling.

The police unlock Lloyd's handcuffs and he is free. He marches up and down the corridor, vowing over and over in explicit terms that "I'm walkin'. I want you to know that."

3:15 P.M.

When it's time to join the staff in the conference room for his preliminary interview, Lloyd goes peacefully, albeit reluctantly.

4:10 P.M.

One of the reasons Lloyd was so agitated today, the doctors assume, is that he has refused to take his biweekly shot of Prolixin, a psychotropic drug that helps control what has been diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia. This is common among mentally ill people in the 18-to-35 age group: Not believing they are mentally ill, they refuse treatment. After talking to the psychiatrist, Lloyd agrees to let a nurse give him his shot.

4:25 P.M.

Lloyd stands alone near the nurses' station. He is crying.

"I'm scared," he says. "I'll do anything if I can go home."

4:45 P.M.

Dinner.

I've yet to be here a full day and already meals have assumed larger-than-life proportions. For the last half-hour, I've been wondering when we will eat, what the food will be, how much I'll get. I think this is my response to boredom. Since before 4 p.m., I've done nothing but sit and watch TV while some patients napped.

Roger and Lloyd are considered elopement risks, which means their meals will be brought to them on the ward. The rest of us queue up at the door, then are led through an outside hall into a cafeteria, where we eat with another ward, AM-12. Dinner is canned peas, mashed potatoes, rolls and spinach-stuffed chicken, with chocolate pudding for dessert. The chicken and potatoes are good. I don't much like the plastic utensils.

In 10 minutes, dinner is over.

7 P.M.

After dinner, most patients' time is their own. Some watch TV, play cards, read, smoke. Some are in bed by 9 o'clock. Those with the appropriate privileges may take a walk outside or visit another building.

Movement of everyone at the IMH is controlled by a 10-stage "status" system. Those on Status One, the most permissive stage, have off-grounds privileges and are more or less free to come and go as they please, so long as they report for meals, medication and sleeping. Those on Status Ten, the least permissive, are confined to a seclusion room. Status Nine (strait-jacket or four-point restraint, when a person's legs as well as arms are tied) is used only in emergencies.

Craig is on Status Two, which means he can freely roam the grounds. And so he invites me to join him on a visit to an unlocked ward, Barry Hall 1, where longer-term patients live. Craig has several friends at Barry Hall; we meet them at a table in the Barry day room.

"You know why we're here?" says Pat, an attractive 31-year-old woman who has become one of Craig's good friends.

"No."

"Because we're insane. You want to hear something funny? See this plastic flower here? This summer, a bee was buzzing on it and then it crawled right inside. Isn't that funny?"

I laugh. The way she tells it, it is funny.

"They won't let me go because I talk to God," says Pat's friend Evelyn, a schizophrenic who looks to be in her 40s. "Out loud. Not introvertedly, extrovertedly. I accused the IMH of being the Antichrist. You know, the devil is the ruler of the world. Satan was thrown down to the earth to cause all the trouble he can. See, God hasn't reigned yet. If God had reigned, there'd be no guns, sickness, sorrow, wars, atomic weapons - nothing but happiness and joy.

"Utopia will come. It's coming. It's soon. You can tell it's going to happen because everything is in turmoil. It's all Biblical. I find peace, I find serenity in the IMH. I dine out every morning, noon and evening. I don't have that much pressure on me. Money is the root of all evil. Money causes greed, theft, murder, many sins. God is a mighty angel watching over everyone. You'll find most people here won't talk about it, but they're with Christ."

After Evelyn is through, Pat offers to buy coffee, provided Craig and I fetch it. We walk across the grounds to the main lobby of General Hospital, where we buy four coffees from a vending machine. When we return to the Barry day room, my seat at the table has been taken. Looking around the room, I see a dozen or so empty chairs. I walk over to one and begin dragging it across the floor to our table.

"Where you going with that chair?" The voice is loud, surly. I look up. A middle-aged male attendant is running toward me.

"I'm just taking it - "

"You ain't taking it nowhere. We have our rules here. You put that back."

"I'll put it back when I'm done," I explain. "I just want - "

"You put that back]" He's reached me now. For a second, I'm afraid he will hit me. It occurs to me: He thinks I am a patient from another ward.

Usually I have a slow fuse, but not tonight. I'm getting as angry as he is. There may or may not be a rule about the placement of chairs, but that's not the point. The point is that this attendant is treating me like dirt. Around and around we go, nearly coming to blows.

"Who do you think you are, anyway?" he rages.

I tell him that I am a reporter. This has an immediate calming effect on him. We agree that I may, after all, bring a chair to the table. Only not that chair. I get another one and finally sit down with the patients. Pat and Evelyn congratulate me. I've done something they've always wanted to do: stand up to this attendant, whom they describe as a bully.

As Craig and I leave, I look across the day room. There's the attendant, watching TV from the disputed chair. His chair.

Part two of two parts.

WEDNESDAY, 12:10 A.M.

Everyone has gone to sleep but me.

I'm watching Johnny Carson when the door opens and two policemen come in with Claire, an unclean, combative, obscene-tongued woman. Only 42, Claire is undergoing her 29th admission to the IMH. Her primary diagnosis: character disorder.

Claire is here because she set her hair on fire, tried to slit her wrists, was eating cigarette butts and soap, was vowing to kill her sister.

"I'm going to get a butcher knife and run it right through my sister]" she screams, fishing through an ashtray for a fresh butt. "My parents, too. Some f------ family. You know what it's like to be depressed? Huh? Day in and day out since I've been 28? Where's it going to end?"

Although her behavior is extreme, Claire's predicament is typical of the people who come to the IMH. They tend to be the sickest of the sick, in a state of crisis, frightened and confused about what is happening to them - people who are at their lowest. They tend also to be people without the financial resources or insurance to afford a bed (at $300 to $400 or more a day) in a private psychiatric hospital.

When there's no place left to go, you go to the IMH.

12:30 A.M.

Third shift has arrived, Claire has calmed down a bit and I go to bed, alone in my room. Everyone else has been asleep for three or four hours.

6:30 A.M.

Wake-up call.

I did not expect to sleep well, but I did. I had been afraid that the ward would be noisy, but it wasn't.

7 A.M.

Attendant Bernie Tramonti, Ann and I are being driven in a state car to St. Joseph Hospital, in North Providence, where a consulting physician conducts electric-shock treatments for IMH patients.

The IMH's electric-shock room was closed years ago. These days, the treatment is rare: a total of only 27 patients have had it in the last seven years, according to the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals, which runs the IMH.

Still, electric shock is among the most common frightening images associated with mental illness - only the mention of lobotomies, no longer practiced in Rhode Island, brings the same chills to the spine. And so I am expecting a scene straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the 1970s film about life in an insane asylum. At one point in that Oscar-winning movie, a patient screams in absolute terror and pain as he is tied down and zapped.

But it's nothing like that today, I am told. And for some deeply depressed people, it can work, when nothing else will. Exactly how the administration of voltage to the brain lifts depression is another question, as yet unanswered.

Ann's latest bout with her illness is particularly troubling to the AM-9 staff, most of whom are fond of her and remember her from years ago, when she spent more than a decade on the IMH's infamous back wards. What is so tragic, they say, is that Ann had been discharged and was doing fine living on her own for the last year or so. But late in the summer her world began to fall apart again. No one can say exactly what went wrong - just as no one can say exactly what will make her well again.

Nothing is more frustrating than this to the professionals, nothing more maddening to families and friends: the unknowns, the uncertainties of major mental illness. The mind can move a Renoir to great art, an Einstein to great thinking . . . and an Ann to a lifetime of pain.

8:05 A.M.

Ann is lying on a stretcher behind a curtain in a recovery room. A nurse has checked her vital signs and started running an IV into her arm. When the doctor is ready, the anesthesiologist injects anesthesia into the IV line. He follows that with a shot of muscle relaxant to minimize convulsion. In a few seconds, Ann is out.

The doctor rubs conducting jelly on both her temples, then straps a rubber headband around her forehead. On the inside of the band are flat metal electrodes, connected by wire to the generator, a black-and-silver machine the size of a Geiger counter. The dial has been set at 150 volts. The doctor is ready. He pushes a button. There is no sound, but Ann's body immediately tenses. Her facial muscles tighten, as if she were about to cry, and a very mild seizure rocks her body for about five seconds. Then it's over. In another 10 minutes, Ann is awake. She has no memory of the treatment, feels no pain.

10:35 A.M.

We are back on AM-9.

After spending a calm night, Lloyd is much more congenial. So is Roger. At the staff meeting, Dr. Schwartz agrees to discharge Roger to a so-called respite bed, a room in someone's home that the community mental-health center rents for transition back to the community. His condition will be followed closely by the center, which will also provide medication, counseling and other help.

During the meeting it is also decided that Claire isn't going to get better quickly, and so she will be transferred to a long-term ward. And Rose has been catatonic for so long, Dr. Schwartz orders her off all medication - a move that occasionally, inexplicably, leads to improvement.

Dr. Schwartz decides to increase Lloyd's Prolixin. He agrees. Then he demands to go home, today. The doctor says no; she wants time to see if the new dosage works. Lloyd has no choice but to stay. Under state law, people sent to the IMH may be kept up to 10 days against their will if they are judged by an IMH psychiatrist to be dangerous to themselves or others. If longer treatment is considered necessary and a patient refuses to stay, a court can order the person kept.

Dr. Schwartz wears two hats: staff psychiatrist at the IMH and medical director of the Kent County Mental Health Center, in Warwick. Her philosophy is that most patients most of the time do better in the community - provided they take their medication. Often she has been able to get judges to order mentally ill people to take medication outside the IMH. When they slip up, as Lloyd did, they can be returned to the IMH, quickly stabilized and then returned home.

NOON

Thirty years ago, when the population of the IMH was more than 3,500, patients rarely, if ever, left the hospital grounds. In the old days, the IMH was a self-contained "city," with its own post office, farm, cannery, dairy, power plant. Patients spent entire lifetimes there, without ever seeing the rest of the world. When they died, many were buried in a potter's field.

Over the past three decades, as the state has moved more and more people back to the community - a process known as deinstitutionalization - the population of the IMH has dropped to fewer than 330. Buildings have been closed or torn down. And most of the remaining patients get off the premises several times a week, to attend dance programs, shop, bowl, visit a park or a baseball game, dine out. Getting out on a regular basis prevents, or at least slows, the numbing effects of living inside an institution.

Today, several AM-9 patients get into a state van with Noreen and ride to Burger King in Apponaug for lunch. Because they have been so withdrawn, Rose and Ann stay behind, as do Roger, who is going home, and Lloyd, who is still considered an escape risk. Each patient has $3.50 to spend. Everyone gets burgers and fries. After lunch, we drive to Goddard State Park, in Warwick, where we take a short walk on the cold beach.

By now, I am comfortable with the AM-9 crew. When she's in an up mood - more and more of the time recently - Jean is a funny, easygoing young woman. So is Leslie. Craig is something of a father figure to other patients on the ward, going out of his way to console them, buy them cigarettes, reassure them they're going to be all right.

1:15 P.M.

Back on AM-9, we find that Roger has been discharged.

Since her shock treatment, Ann has perked up considerably. She is talking with the staff, enjoying a cigarette - even smiling occasionally. Lloyd is watching TV. Jean and Craig sit in a corner and chat.

Rose continues staring into space. Several staff members approach her, ask her how she's feeling. Then her husband calls. Would she like to come to the phone? For just a moment? The response is silence. Please? Your husband would like so very much to say hello. Again, silence. I have never seen such behavior in a person who wasn't deaf or autistic, and Rose is neither. Until the latest episode of her illness, in fact, she was outgoing and pleasant. But since being admitted, a month ago, about the only times she has spoken have been to suddenly, spontaneously jump up and scream, "I'm sorry for what I've done]" or "Oh, my God]" What she means, no one knows.

3:10 P.M.

Together with Craig, who will move to a group home soon, I set off for the IMH canteen, where patients with grounds privileges gather to talk, smoke, have 30-cent sodas. If any part of the IMH fits the outsider's preconception of life in an asylum, the canteen, located in the basement of a building several hundred yards from Adolf Meyer, is it.

It is a dim, cavernous room, full of smoke and noise. About two dozen patients are here. Some are playing cards. Some are talking to themselves. A couple are catnapping. One woman is wearing a Walkman radio and dancing with herself - not some old-fashioned waltz, but an honest-to-gosh, get-down boogie. One gap-toothed man wears a black witch's hat.

Immediately, I get hit up for change and cigarettes. "Got a quarter?" "Cigarette?" "Match?" "Buy me a coffee?" Few, if any, long-term patients have their own money. The government provides a small allowance every month, but this usually goes quickly. Then it's time to beg. Those rare patients who have outside sources of cash are popular.

But whatever else it may seem, the canteen provides a break from life on the wards, much as a neighborhood bar or health club provides noninstitutionalized people their chance to get away.

4:55 P.M.

At dinner, Ann is extremely talkative. I listen, fascinated.

She tells me about the food - how, considering budgetary constraints, it isn't all that bad. I agree. I can see now why the staff likes Ann so much; when she's out of the doldrums, she is a kind, intelligent, even charming woman. I feel terribly sorry for her. I feel something else, too: anger at a disorder than can be so cruel, so mysterious, so stubborn as mental illness.

7:20 P.M.

Craig and I wander down to AM-4, an old ward that has been turned into a social club run by the Providence YMCA.

Patients with the appropriate privileges come here every night for arts and crafts, board games, card games; to listen to the stereo, to chat. Special dinners and dances are also held here. AM-4 is the cheeriest place at the IMH that I have seen: soft-blue walls, curtained windows, real hanging plants, tables with tablecloths, comfortable chairs, paintings by patients, a selection of current magazines.

I take a seat and scribble a few notes. As I write, a middle-aged woman approaches, looks skeptically, then asks, "What you doing?"

"Taking notes," I say.

"To who?"

"To me."

"You write notes to yourself? You mean you don't have anybody to write notes to?"

The woman leaves, and is soon replaced by a young man who asks me, "Elvis, you got change for a one?"

"No," I say. He walks off.

The woman returns. I tell her that I am a reporter. "Maybe you're half nuts, too," she says. "Maybe you're wacky. I don't trust any of you, you know. What's your name, anyway?"

"Wayne Miller."

"Irish, huh?"

"No, English."

"I have no heart for the English," she says, disgusted.

THURSDAY, 7:05 A.M.

Breakfast is two stale doughnuts, dry cereal, juice, decaffeinated coffee. Dinner may be OK at the IMH, but breakfast is horrible. Even though I'm hungry, I only nibble at the doughnuts.

8:30 A.M.

Like a pendulum, Ann's mood has swung back to depression - a darker, uglier depression than I've ever seen in anyone. One minute she's sitting in a chair in the day room, her head bowed, sobbing; the next, she's on her feet. She runs to a wall and bangs her head against it - not some gentle tapping, but a vicious slamming that makes me cringe.

"I don't understand," Ann screams in a voice that chills me. "I don't understand. What have I done? God, what have I done?"

Psychologist Alan Feinstein and Thelma Gileau, an attendant, gently peel her off the wall and, their arms around her, try to console her. Like most of the staff I have observed on AM-9, Feinstein and Gileau are compassionate and competent. Solace in this case, however, is not enough. Ann does not calm down until a nurse leads her into her bedroom and gives her a shot of Atavan, a sedative.

8:45 A.M.

The daily ward meeting is a chance for patients to discuss their gripes. It also serves as a form of group therapy. After rearranging the day-room chairs, the staff and patients sit in a circle and introduce themselves. Surprisingly, Rose gives her name this morning; for her, this is progress.

Jean continues to be upset by her relationship with her parents: one day, their visit is welcome; the next time, they leave her in tears. The AM-9 staff would like that relationship to be a little less rocky before her planned discharge to a group home, early next week.

"What is it that makes you that way?" Mrs. Gileau asks.

"Death," says Jean, who experiences severe spells of paranoia and depression. "I don't want to die in an insane asylum."

"We're concerned about that," Mrs. Gileau says.

"Are you afraid you'll be killed at night?" asks Dr. Schwartz.

"Yes."

"Do you know how it's going to be done?" Dr. Schwartz continues.

"No. I have no idea."

"I wish I'd die," Ann bursts out. "The mental torture I'm being put through . . ."

10 A.M.

Downstairs in the activity room, some of the AM-9 patients have joined a drama class. Play acting helps the patients discuss their problems.

Jerry, a self-proclaimed minister, seizes the opportunity to preach. "Believe in miracles," he urges the group. "Trust the Lord for your salvation] Ask God to forgive you your sins] Believe He has accepted you]"

"I just want to be able to wake up one morning and feel good," says a patient from another ward. "Just be able to work one hour and feel good."

1 P.M.

We are joining patients from two long-term wards for the weekly charter-bus trip to Legion Bowladrome, in Cranston.

The Bowladrome's regular patrons stare as we file in, get our shoes and begin bowling. The AM-9 bunch, for the most part, know how to bowl; Jean and Lloyd are actually quite good. Some of the long-term patients, however, haven't the slightest idea of what's going on. One walks to the line, ball in hand, and drops it onto the alley; it dribbles into the gutter. Another has a decent toss, but stares vacantly at the alley when the pins drop. A third steps to the line and casually bowls a strike. I'm amazed.

For these long-term patients - many of whom lived on the back wards before they were closed - just being able to get outside the IMH is tremendous progress. Some of the ones who can bowl couldn't not too long ago.

While we are bowling, a patient wanders out of the Bowladrome, unnoticed until she is gone. On the way back to the IMH we search for her, without success. Several hours later, after she has ordered and happily eaten a dinner for which she cannot pay, the police are called. Cranston police, used to such runaways, bring her back.

EARLY EVENING

Three more patients have been admitted: a young man who threatened suicide, a 39-year-old woman who overdosed on sleeping pills, a 21-year-old woman who became paranoid that someone was trying to kill her baby. A close watch is ordered for all three.

FRIDAY, 10:30 A.M.

Lloyd's behavior has been exemplary, his new dosage seems to be working well, and so Dr. Schwartz decides to discharge him today. Russ Partridge, a social worker from the community mental-health center, gives Lloyd the word.

"Thanks] Really? Thanks]" Lloyd says excitedly. "No problems this time. I promise. I'm not going to let anyone down."

"You've got to take your meds," Russ warns.

"I will this time, I promise. They make me feel better. Before, I was blah-blah-blah. My head was twisted. Now, I feel better."

1:15 P.M.

In the day room, Ann is sitting, head in hands. Rose is staring at the walls - but her eyes are following the movements of people in the room.

Jean's privileges have been increased, and she joins Craig and me for a stroll about the grounds. If all goes well, she will get out the first part of the week. Craig, too, should get out sometime this month. Both are anxious, but eager, about their impending discharges.

I am leaving, too, in another hour or two. I depart with these thoughts from Danna Mauch, director of state Mental Health Services:

"The IMH is a place where people now come as a last resort. Ultimately, we should be judged by the extent to which we appreciate the profound pain and suffering experienced by people with mental disabilities."

G. Wayne Miller is a Journal-Bulletin staff writer.

Inside the I.M.H.

G. Wayne Miller

Publication Date: November 10, 1985 Page: M-06 Section: MAGAZINE Edition: ALL

Rhode Island officials today are proud of the Institute of Mental Health, which not very long ago was considered a public disgrace. Since it was opened, 115 years ago this month, officials say, no reporter has ever been allowed to live inside the IMH with the purpose of publishing what he saw. In September, after being assured that the confidentiality of patients would be protected, IMH administrators agreed to let Journal-Bulletin reporter G. Wayne Miller spend four days and three nights on AM-9, a locked ward. Both patients and staff were told in advance who he was, and what he would be doing.

This is his report.

Part one of two parts.

TUESDAY, 10:10 A.M.

I've just been introduced to Roger, 35, who has nothing at all to say to me. Roger is unshaven. His eyes are bloodshot. His hair is dirty and short, like a British hoodlum's.

Roger is not a happy man. His mental illness, known as a bipolar disorder, has flared again, making him angry and tense. Earlier in the week, he got roaring drunk and threatened to beat up his elderly parents; the police brought him in handcuffs to the IMH. He wants out. "Roger's the name, escape's the game," he keeps repeating.

At the moment, Roger is sitting across from me in the conference room of Ward AM-9. In terms of the quality of its treatment and the caliber of its staff, AM-9 is considered among the institution's most progressive wards. The challenge on AM-9 is to take very sick people, quickly make them better and then discharge them as soon as possible.

Roger sits at the conference table, a sly grin on his face. With him are a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, an attendant, a nurse. Their job during this meeting is to pump Roger for information so that they can begin shaping a treatment plan. One of his problems is he won't take medication to control his disorder. Dr. Aimee Schwartz, the psychiatrist, is hoping that Roger will agree to try a new prescription.

During the interview, Roger skips back and forth between subjects. He lives in a tough neighborhood, he says. Takes drugs sometimes. Fights. Has a habit of abusing his body. "I almost got murdered. I have a brain concussion right now. I got a bad heart, a busted-up ear, scraped knuckles."

According to the report Dr. Schwartz has, Roger got into an argument with his parents over a pack of cigarettes. What the issue was, exactly, is unclear. The report also says he may have been hearing voices.

"Lies]" Roger says. "I'm here under false pretenses. I got kidnapped. Shanghaied."

"Why would they lie, Roger?" Dr. Schwartz asks.

"I guess they say I'm crazy."

"Are you?"

"I knock on wood I ain't."

10:30 A.M.

Roger's review is over, and now activity has shifted to the day room, where staff and patients congregate during their free moments.

Ann, a chronically depressed woman in her 50s, sits in a chair, her head buried in her hands. A chaplain comforts her. Rose, also depressed, also middle-aged, sits alone, staring blankly. For days, the staff has been unable to coax so much as a single word out of her. Other patients are more upbeat this morning. Craig, 42, is talking with a psychologist about his progress, which has been substantial. Jean, 20, is on the pay phone to her parents.

Without fully realizing it, I keep looking over my shoulder to see if anyone has crept up behind me.

And it's not just my very real fear of Roger, who strikes me as a 170-pound pressure cooker with the lid about to blow off.

No, it's the history of the IMH, known to a century of Rhode Islanders simply as Howard, after the Cranston farm that was here before. It's the weight of all those stories people tell about what goes on inside here, or what they think goes on. Stories about assembly lines for horrifying electric-shock treatments. About the poor souls subjected to the tortures of lobotomies and cold-water therapies. About the notorious back wards, where people were treated, and consequently acted, like caged animals. In short, about the state's very own "loony bin," a complex of brooding Victorian buildings where entire lifetimes were swallowed by darkness.

Since November, 1870, when it opened as the State Asylum for the Incurable Insane, the IMH has been the state's public psychiatric hospital - the temporary or permanent home for generations of mentally ill Rhode Islanders. In the last two decades, the state has moved hundreds of patients into group homes and community residences. Hundreds of others, who once would have been locked away, are now treated in the community. Today, only the sickest mentally ill go to the IMH, almost always when they are in a state of crisis. Most spend only a few days inside the hospital.

For the last two or three years, state officials have been singing the praises of the IMH: how the back wards have all been closed, how the institution has emerged from the Dark Ages to become a humane, compassionate place, where people get better - not abused.

I'm here to see.

10:45 A.M.

I'm still sitting in the day room.

Roger, who disappeared for several minutes, makes his reappearance dressed in a bathrobe. He is clean, having showered with Kwell, an antiparasitic chemical that kills body lice. He is unwilling to take his new medication. Under Rhode Island law, it would take a court order to force him; there is, as yet, no such order. He paces the hall, continuing to froth about being "shanghaied."

I wonder if Roger will approach me. He doesn't.

AM-9, located in the Adolf Meyer Building, is what is known as an admissions ward. It is affiliated with community mental-health centers in Warwick and Barrington. Under this arrangement, patients admitted to the IMH from the East Bay and West Bay areas come directly to AM-9, are treated here and eventually are discharged from here. In this way, community and hospital can stay in close touch, the idea being that patient care improves when continuity is ensured.

It is not a dreary place, this ward; neither is it especially cheerful. Because the doors are always locked, because the windows are covered with knifeproof safety screens, because there is a seclusion room at one end and restraint devices in a nearby closet - because needles and tranquilizers appear during emergencies, and pills are handed out every few hours - it is hard ever to forget just what this is: a ward in the state psychiatric hospital.

Ward AM-9 is essentially one long corridor with rooms off it. The day room, about three-quarters of the way down the corridor, predominates. It is about the size of a classroom, with seven large windows facing New London Avenue. The walls are blue. Hanging on them are bulletin boards and some Woolworth's art: framed reproductions of a ship, flowers, a duck. Thirty-five wood-frame upholstered chairs are here, along with two coffee tables, two end tables, a color TV and two card tables with inlaid chess- and checkerboards. All of the furniture is new. The chairs are comfortable. The TV gets good reception.

Off the day room is the nurses' station, a glass-enclosed booth where records and medications are kept. At the southern end of the ward are two women's bedrooms, an examination room and a seclusion room, where the most agitated patients are sequestered. The seclusion room has one bed, one window, an outside lock and no inside doorknob; inside doorknobs were removed from all IMH seclusion rooms last year after a patient, using his belt as a noose, hanged himself from one. A long corridor stretches north from the day room. Off the corridor are men's bedrooms, shower rooms, bathrooms, a kitchen. All of the bedrooms sleep two people, except one that sleeps four.

11:10 A.M.

In the day room, a couple of patients are exercising, stretching their arms, bending over to touch their toes. Mild, all of it.

Roger finally drinks a dose of lithium, his new medication. It has no immediate effect, nor will it; it can be days, even weeks, before some drugs take hold. Despite his abrasive personality, I'm beginning to feel a touch of compassion for Roger, a man whose lot in life clearly overwhelms him. Because of his illness, he has been unable to hold a steady job. He has few, if any, friends. Here on AM-9, when he thinks no one is watching, his posturing and combativeness subside and Roger sits forlornly alone, like a grammar-school kid who doesn't have anyone to play with.

NOON

Down three flights from AM-9 in a basement activity room, most of the ward's patients have gathered to prepare lunch, under the guidance of Noreen Altham, an activities coordinator. Numerous activities and therapy sessions are available weekdays: music, dance, drama, group discussions. Along with counseling and medication, these sessions help with recovery.

Ann has her good days, but today is not one of them. She sits in a chair sobbing, saying, "I'm sick to my stomach. I can't do it." In the kitchen, the remaining patients set about preparing the food. On today's menu: BLT sandwiches, fruit salad and Hawaiian Fluff, a pineapple-and-whipped-cream dessert that is Noreen's creation. There is a lot of joking and laughing as the patients become absorbed in their work.

"The idea is to give them a chance to mingle, make some decisions," Noreen says, "see if they're able to follow through on tasks, relate to one another, take directions. Most people on admissions wards hold back. They're fearful. The most important thing for them is a trustful environment."

2:55 P.M.

After a group therapy session during which we discussed our feelings (What makes us happy? Sad? What scares us?), we have returned to the day room.

The door opens and a man is brought in by two policemen. Lloyd is tall, blond, in his 20s. He wears a headband and a T-shirt. Like Roger, he has threatened his parents. He has also been smoking marijuana, a substance that doesn't mix well with his medication. Once again, I feel like all hell is about to break loose. The second that door opened, the tension level on the ward went through the ceiling.

The police unlock Lloyd's handcuffs and he is free. He marches up and down the corridor, vowing over and over in explicit terms that "I'm walkin'. I want you to know that."

3:15 P.M.

When it's time to join the staff in the conference room for his preliminary interview, Lloyd goes peacefully, albeit reluctantly.

4:10 P.M.

One of the reasons Lloyd was so agitated today, the doctors assume, is that he has refused to take his biweekly shot of Prolixin, a psychotropic drug that helps control what has been diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia. This is common among mentally ill people in the 18-to-35 age group: Not believing they are mentally ill, they refuse treatment. After talking to the psychiatrist, Lloyd agrees to let a nurse give him his shot.

4:25 P.M.

Lloyd stands alone near the nurses' station. He is crying.

"I'm scared," he says. "I'll do anything if I can go home."

4:45 P.M.

Dinner.

I've yet to be here a full day and already meals have assumed larger-than-life proportions. For the last half-hour, I've been wondering when we will eat, what the food will be, how much I'll get. I think this is my response to boredom. Since before 4 p.m., I've done nothing but sit and watch TV while some patients napped.

Roger and Lloyd are considered elopement risks, which means their meals will be brought to them on the ward. The rest of us queue up at the door, then are led through an outside hall into a cafeteria, where we eat with another ward, AM-12. Dinner is canned peas, mashed potatoes, rolls and spinach-stuffed chicken, with chocolate pudding for dessert. The chicken and potatoes are good. I don't much like the plastic utensils.

In 10 minutes, dinner is over.

7 P.M.

After dinner, most patients' time is their own. Some watch TV, play cards, read, smoke. Some are in bed by 9 o'clock. Those with the appropriate privileges may take a walk outside or visit another building.

Movement of everyone at the IMH is controlled by a 10-stage "status" system. Those on Status One, the most permissive stage, have off-grounds privileges and are more or less free to come and go as they please, so long as they report for meals, medication and sleeping. Those on Status Ten, the least permissive, are confined to a seclusion room. Status Nine (strait-jacket or four-point restraint, when a person's legs as well as arms are tied) is used only in emergencies.

Craig is on Status Two, which means he can freely roam the grounds. And so he invites me to join him on a visit to an unlocked ward, Barry Hall 1, where longer-term patients live. Craig has several friends at Barry Hall; we meet them at a table in the Barry day room.

"You know why we're here?" says Pat, an attractive 31-year-old woman who has become one of Craig's good friends.

"No."

"Because we're insane. You want to hear something funny? See this plastic flower here? This summer, a bee was buzzing on it and then it crawled right inside. Isn't that funny?"

I laugh. The way she tells it, it is funny.

"They won't let me go because I talk to God," says Pat's friend Evelyn, a schizophrenic who looks to be in her 40s. "Out loud. Not introvertedly, extrovertedly. I accused the IMH of being the Antichrist. You know, the devil is the ruler of the world. Satan was thrown down to the earth to cause all the trouble he can. See, God hasn't reigned yet. If God had reigned, there'd be no guns, sickness, sorrow, wars, atomic weapons - nothing but happiness and joy.

"Utopia will come. It's coming. It's soon. You can tell it's going to happen because everything is in turmoil. It's all Biblical. I find peace, I find serenity in the IMH. I dine out every morning, noon and evening. I don't have that much pressure on me. Money is the root of all evil. Money causes greed, theft, murder, many sins. God is a mighty angel watching over everyone. You'll find most people here won't talk about it, but they're with Christ."

After Evelyn is through, Pat offers to buy coffee, provided Craig and I fetch it. We walk across the grounds to the main lobby of General Hospital, where we buy four coffees from a vending machine. When we return to the Barry day room, my seat at the table has been taken. Looking around the room, I see a dozen or so empty chairs. I walk over to one and begin dragging it across the floor to our table.

"Where you going with that chair?" The voice is loud, surly. I look up. A middle-aged male attendant is running toward me.

"I'm just taking it - "

"You ain't taking it nowhere. We have our rules here. You put that back."

"I'll put it back when I'm done," I explain. "I just want - "

"You put that back]" He's reached me now. For a second, I'm afraid he will hit me. It occurs to me: He thinks I am a patient from another ward.

Usually I have a slow fuse, but not tonight. I'm getting as angry as he is. There may or may not be a rule about the placement of chairs, but that's not the point. The point is that this attendant is treating me like dirt. Around and around we go, nearly coming to blows.

"Who do you think you are, anyway?" he rages.

I tell him that I am a reporter. This has an immediate calming effect on him. We agree that I may, after all, bring a chair to the table. Only not that chair. I get another one and finally sit down with the patients. Pat and Evelyn congratulate me. I've done something they've always wanted to do: stand up to this attendant, whom they describe as a bully.

As Craig and I leave, I look across the day room. There's the attendant, watching TV from the disputed chair. His chair.

Part two of two parts.

WEDNESDAY, 12:10 A.M.

Everyone has gone to sleep but me.

I'm watching Johnny Carson when the door opens and two policemen come in with Claire, an unclean, combative, obscene-tongued woman. Only 42, Claire is undergoing her 29th admission to the IMH. Her primary diagnosis: character disorder.

Claire is here because she set her hair on fire, tried to slit her wrists, was eating cigarette butts and soap, was vowing to kill her sister.

"I'm going to get a butcher knife and run it right through my sister]" she screams, fishing through an ashtray for a fresh butt. "My parents, too. Some f------ family. You know what it's like to be depressed? Huh? Day in and day out since I've been 28? Where's it going to end?"

Although her behavior is extreme, Claire's predicament is typical of the people who come to the IMH. They tend to be the sickest of the sick, in a state of crisis, frightened and confused about what is happening to them - people who are at their lowest. They tend also to be people without the financial resources or insurance to afford a bed (at $300 to $400 or more a day) in a private psychiatric hospital.

When there's no place left to go, you go to the IMH.

12:30 A.M.

Third shift has arrived, Claire has calmed down a bit and I go to bed, alone in my room. Everyone else has been asleep for three or four hours.

6:30 A.M.

Wake-up call.

I did not expect to sleep well, but I did. I had been afraid that the ward would be noisy, but it wasn't.

7 A.M.

Attendant Bernie Tramonti, Ann and I are being driven in a state car to St. Joseph Hospital, in North Providence, where a consulting physician conducts electric-shock treatments for IMH patients.

The IMH's electric-shock room was closed years ago. These days, the treatment is rare: a total of only 27 patients have had it in the last seven years, according to the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals, which runs the IMH.

Still, electric shock is among the most common frightening images associated with mental illness - only the mention of lobotomies, no longer practiced in Rhode Island, brings the same chills to the spine. And so I am expecting a scene straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the 1970s film about life in an insane asylum. At one point in that Oscar-winning movie, a patient screams in absolute terror and pain as he is tied down and zapped.

But it's nothing like that today, I am told. And for some deeply depressed people, it can work, when nothing else will. Exactly how the administration of voltage to the brain lifts depression is another question, as yet unanswered.

Ann's latest bout with her illness is particularly troubling to the AM-9 staff, most of whom are fond of her and remember her from years ago, when she spent more than a decade on the IMH's infamous back wards. What is so tragic, they say, is that Ann had been discharged and was doing fine living on her own for the last year or so. But late in the summer her world began to fall apart again. No one can say exactly what went wrong - just as no one can say exactly what will make her well again.

Nothing is more frustrating than this to the professionals, nothing more maddening to families and friends: the unknowns, the uncertainties of major mental illness. The mind can move a Renoir to great art, an Einstein to great thinking . . . and an Ann to a lifetime of pain.

8:05 A.M.

Ann is lying on a stretcher behind a curtain in a recovery room. A nurse has checked her vital signs and started running an IV into her arm. When the doctor is ready, the anesthesiologist injects anesthesia into the IV line. He follows that with a shot of muscle relaxant to minimize convulsion. In a few seconds, Ann is out.

The doctor rubs conducting jelly on both her temples, then straps a rubber headband around her forehead. On the inside of the band are flat metal electrodes, connected by wire to the generator, a black-and-silver machine the size of a Geiger counter. The dial has been set at 150 volts. The doctor is ready. He pushes a button. There is no sound, but Ann's body immediately tenses. Her facial muscles tighten, as if she were about to cry, and a very mild seizure rocks her body for about five seconds. Then it's over. In another 10 minutes, Ann is awake. She has no memory of the treatment, feels no pain.

10:35 A.M.

We are back on AM-9.

After spending a calm night, Lloyd is much more congenial. So is Roger. At the staff meeting, Dr. Schwartz agrees to discharge Roger to a so-called respite bed, a room in someone's home that the community mental-health center rents for transition back to the community. His condition will be followed closely by the center, which will also provide medication, counseling and other help.

During the meeting it is also decided that Claire isn't going to get better quickly, and so she will be transferred to a long-term ward. And Rose has been catatonic for so long, Dr. Schwartz orders her off all medication - a move that occasionally, inexplicably, leads to improvement.

Dr. Schwartz decides to increase Lloyd's Prolixin. He agrees. Then he demands to go home, today. The doctor says no; she wants time to see if the new dosage works. Lloyd has no choice but to stay. Under state law, people sent to the IMH may be kept up to 10 days against their will if they are judged by an IMH psychiatrist to be dangerous to themselves or others. If longer treatment is considered necessary and a patient refuses to stay, a court can order the person kept.

Dr. Schwartz wears two hats: staff psychiatrist at the IMH and medical director of the Kent County Mental Health Center, in Warwick. Her philosophy is that most patients most of the time do better in the community - provided they take their medication. Often she has been able to get judges to order mentally ill people to take medication outside the IMH. When they slip up, as Lloyd did, they can be returned to the IMH, quickly stabilized and then returned home.

NOON

Thirty years ago, when the population of the IMH was more than 3,500, patients rarely, if ever, left the hospital grounds. In the old days, the IMH was a self-contained "city," with its own post office, farm, cannery, dairy, power plant. Patients spent entire lifetimes there, without ever seeing the rest of the world. When they died, many were buried in a potter's field.

Over the past three decades, as the state has moved more and more people back to the community - a process known as deinstitutionalization - the population of the IMH has dropped to fewer than 330. Buildings have been closed or torn down. And most of the remaining patients get off the premises several times a week, to attend dance programs, shop, bowl, visit a park or a baseball game, dine out. Getting out on a regular basis prevents, or at least slows, the numbing effects of living inside an institution.

Today, several AM-9 patients get into a state van with Noreen and ride to Burger King in Apponaug for lunch. Because they have been so withdrawn, Rose and Ann stay behind, as do Roger, who is going home, and Lloyd, who is still considered an escape risk. Each patient has $3.50 to spend. Everyone gets burgers and fries. After lunch, we drive to Goddard State Park, in Warwick, where we take a short walk on the cold beach.

By now, I am comfortable with the AM-9 crew. When she's in an up mood - more and more of the time recently - Jean is a funny, easygoing young woman. So is Leslie. Craig is something of a father figure to other patients on the ward, going out of his way to console them, buy them cigarettes, reassure them they're going to be all right.

1:15 P.M.

Back on AM-9, we find that Roger has been discharged.

Since her shock treatment, Ann has perked up considerably. She is talking with the staff, enjoying a cigarette - even smiling occasionally. Lloyd is watching TV. Jean and Craig sit in a corner and chat.

Rose continues staring into space. Several staff members approach her, ask her how she's feeling. Then her husband calls. Would she like to come to the phone? For just a moment? The response is silence. Please? Your husband would like so very much to say hello. Again, silence. I have never seen such behavior in a person who wasn't deaf or autistic, and Rose is neither. Until the latest episode of her illness, in fact, she was outgoing and pleasant. But since being admitted, a month ago, about the only times she has spoken have been to suddenly, spontaneously jump up and scream, "I'm sorry for what I've done]" or "Oh, my God]" What she means, no one knows.

3:10 P.M.

Together with Craig, who will move to a group home soon, I set off for the IMH canteen, where patients with grounds privileges gather to talk, smoke, have 30-cent sodas. If any part of the IMH fits the outsider's preconception of life in an asylum, the canteen, located in the basement of a building several hundred yards from Adolf Meyer, is it.

It is a dim, cavernous room, full of smoke and noise. About two dozen patients are here. Some are playing cards. Some are talking to themselves. A couple are catnapping. One woman is wearing a Walkman radio and dancing with herself - not some old-fashioned waltz, but an honest-to-gosh, get-down boogie. One gap-toothed man wears a black witch's hat.

Immediately, I get hit up for change and cigarettes. "Got a quarter?" "Cigarette?" "Match?" "Buy me a coffee?" Few, if any, long-term patients have their own money. The government provides a small allowance every month, but this usually goes quickly. Then it's time to beg. Those rare patients who have outside sources of cash are popular.

But whatever else it may seem, the canteen provides a break from life on the wards, much as a neighborhood bar or health club provides noninstitutionalized people their chance to get away.

4:55 P.M.

At dinner, Ann is extremely talkative. I listen, fascinated.

She tells me about the food - how, considering budgetary constraints, it isn't all that bad. I agree. I can see now why the staff likes Ann so much; when she's out of the doldrums, she is a kind, intelligent, even charming woman. I feel terribly sorry for her. I feel something else, too: anger at a disorder than can be so cruel, so mysterious, so stubborn as mental illness.

7:20 P.M.

Craig and I wander down to AM-4, an old ward that has been turned into a social club run by the Providence YMCA.

Patients with the appropriate privileges come here every night for arts and crafts, board games, card games; to listen to the stereo, to chat. Special dinners and dances are also held here. AM-4 is the cheeriest place at the IMH that I have seen: soft-blue walls, curtained windows, real hanging plants, tables with tablecloths, comfortable chairs, paintings by patients, a selection of current magazines.

I take a seat and scribble a few notes. As I write, a middle-aged woman approaches, looks skeptically, then asks, "What you doing?"

"Taking notes," I say.

"To who?"

"To me."

"You write notes to yourself? You mean you don't have anybody to write notes to?"

The woman leaves, and is soon replaced by a young man who asks me, "Elvis, you got change for a one?"

"No," I say. He walks off.

The woman returns. I tell her that I am a reporter. "Maybe you're half nuts, too," she says. "Maybe you're wacky. I don't trust any of you, you know. What's your name, anyway?"

"Wayne Miller."

"Irish, huh?"

"No, English."

"I have no heart for the English," she says, disgusted.

THURSDAY, 7:05 A.M.

Breakfast is two stale doughnuts, dry cereal, juice, decaffeinated coffee. Dinner may be OK at the IMH, but breakfast is horrible. Even though I'm hungry, I only nibble at the doughnuts.

8:30 A.M.

Like a pendulum, Ann's mood has swung back to depression - a darker, uglier depression than I've ever seen in anyone. One minute she's sitting in a chair in the day room, her head bowed, sobbing; the next, she's on her feet. She runs to a wall and bangs her head against it - not some gentle tapping, but a vicious slamming that makes me cringe.

"I don't understand," Ann screams in a voice that chills me. "I don't understand. What have I done? God, what have I done?"

Psychologist Alan Feinstein and Thelma Gileau, an attendant, gently peel her off the wall and, their arms around her, try to console her. Like most of the staff I have observed on AM-9, Feinstein and Gileau are compassionate and competent. Solace in this case, however, is not enough. Ann does not calm down until a nurse leads her into her bedroom and gives her a shot of Atavan, a sedative.

8:45 A.M.

The daily ward meeting is a chance for patients to discuss their gripes. It also serves as a form of group therapy. After rearranging the day-room chairs, the staff and patients sit in a circle and introduce themselves. Surprisingly, Rose gives her name this morning; for her, this is progress.

Jean continues to be upset by her relationship with her parents: one day, their visit is welcome; the next time, they leave her in tears. The AM-9 staff would like that relationship to be a little less rocky before her planned discharge to a group home, early next week.

"What is it that makes you that way?" Mrs. Gileau asks.

"Death," says Jean, who experiences severe spells of paranoia and depression. "I don't want to die in an insane asylum."

"We're concerned about that," Mrs. Gileau says.

"Are you afraid you'll be killed at night?" asks Dr. Schwartz.

"Yes."

"Do you know how it's going to be done?" Dr. Schwartz continues.

"No. I have no idea."

"I wish I'd die," Ann bursts out. "The mental torture I'm being put through . . ."

10 A.M.

Downstairs in the activity room, some of the AM-9 patients have joined a drama class. Play acting helps the patients discuss their problems.

Jerry, a self-proclaimed minister, seizes the opportunity to preach. "Believe in miracles," he urges the group. "Trust the Lord for your salvation] Ask God to forgive you your sins] Believe He has accepted you]"

"I just want to be able to wake up one morning and feel good," says a patient from another ward. "Just be able to work one hour and feel good."

1 P.M.

We are joining patients from two long-term wards for the weekly charter-bus trip to Legion Bowladrome, in Cranston.

The Bowladrome's regular patrons stare as we file in, get our shoes and begin bowling. The AM-9 bunch, for the most part, know how to bowl; Jean and Lloyd are actually quite good. Some of the long-term patients, however, haven't the slightest idea of what's going on. One walks to the line, ball in hand, and drops it onto the alley; it dribbles into the gutter. Another has a decent toss, but stares vacantly at the alley when the pins drop. A third steps to the line and casually bowls a strike. I'm amazed.

For these long-term patients - many of whom lived on the back wards before they were closed - just being able to get outside the IMH is tremendous progress. Some of the ones who can bowl couldn't not too long ago.

While we are bowling, a patient wanders out of the Bowladrome, unnoticed until she is gone. On the way back to the IMH we search for her, without success. Several hours later, after she has ordered and happily eaten a dinner for which she cannot pay, the police are called. Cranston police, used to such runaways, bring her back.

EARLY EVENING

Three more patients have been admitted: a young man who threatened suicide, a 39-year-old woman who overdosed on sleeping pills, a 21-year-old woman who became paranoid that someone was trying to kill her baby. A close watch is ordered for all three.

FRIDAY, 10:30 A.M.

Lloyd's behavior has been exemplary, his new dosage seems to be working well, and so Dr. Schwartz decides to discharge him today. Russ Partridge, a social worker from the community mental-health center, gives Lloyd the word.

"Thanks] Really? Thanks]" Lloyd says excitedly. "No problems this time. I promise. I'm not going to let anyone down."

"You've got to take your meds," Russ warns.

"I will this time, I promise. They make me feel better. Before, I was blah-blah-blah. My head was twisted. Now, I feel better."

1:15 P.M.

In the day room, Ann is sitting, head in hands. Rose is staring at the walls - but her eyes are following the movements of people in the room.

Jean's privileges have been increased, and she joins Craig and me for a stroll about the grounds. If all goes well, she will get out the first part of the week. Craig, too, should get out sometime this month. Both are anxious, but eager, about their impending discharges.

I am leaving, too, in another hour or two. I depart with these thoughts from Danna Mauch, director of state Mental Health Services:

"The IMH is a place where people now come as a last resort. Ultimately, we should be judged by the extent to which we appreciate the profound pain and suffering experienced by people with mental disabilities."

G. Wayne Miller is a Journal-Bulletin staff writer.

Published on April 16, 2016 10:49

March 25, 2016

In Ladd's final days, some exemplary care

Many residents of the Ladd Center, Rhode Island's now-closed institution for the developmentally disabled, suffered cruelly through years of abuse and neglect. But toward the end, as the state moved aggressively to move everyone onto what was then, the 1990s, a model community system (and now is under intense scrutiny for alleged abuse and neglect), conditions had improved significantly. I witnessed this personally during the week 26 years ago that I was allowed to live on one of the last wards for a Providence Journal story.

Here is that story, the story of Lorraine Jean Bessette.

Lorraine's world As Ladd Center prepares to close, a new day dawns for the profoundly disabled

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: July 29, 1990 Page: A-01 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

SHE WAS given ID No. 2774. She was labeled an "idiot," one step below "imbecile" on the mental scale. She had blue eyes, perfect features, beautiful hair and skin, curvature of the spine. She was 18 months old.

"The child is a great burden on the mother," read the paperwork. "There are four older children, the oldest of whom is only eight. Mother is expecting a sixth child in another month. The baby, Lorraine, is very heavy, is unresponsive and takes a great deal of mother's time. She is exhausted. Lorraine is also a feeding problem."

Four days after Christmas, 1948, Lorraine Jean Bessette, born with severe cerebral palsy, was committed to the Ladd Center.

She's still there.

But only for a little longer.

Lorraine's headed for a home in the community.

And Ladd is going out of business, probably next year. Closing Rhode Island's only institution for the retarded will bring down the curtain on an era whose first act was compassion, whose long-running second act was degradation and despair, and whose finale is resplendent with a chorus of new dignity for some of society's most vulnerable - and needy - people, people like Lorraine.

Lorraine's 43 now, all grown up.

She loves babies, hugs, thumbing through women's magazines. She hates vegetables, particularly squash. She favors pink fingernail polish, ribbons in her hair, dresses she orders herself from the Sears catalogue, coffee with cream and sugar, chocolate cake, barbecued chicken - provided it is ground to a consistency she can swallow. Her best friend is Diane, who spent years at Ladd and is in a group home now. Diane telephones about once a week. Her picture's on Lorraine's dresser. When she can, she has Lorraine over for dinner.

On this summer Sunday, Lorraine is in her wheelchair, custom-built at a cost of almost $4,000 to accommodate her 88-pound body, which is permanently twisted in ways unique to her. On her tray is one of her sign boards. Lorraine cannot utter a word, but she is a masterful - and, sometimes, sly - communicator. With no more than facial expressions and her signature giggle, Lorraine can tease, flirt, plead and display anger or disgust or great joy.

Her sign boards expand the possibilities. This one, the small everyday one, has pictures of her doll, her bed, a TV, a toilet, orange juice and a three-layer chocolate cake. All day, she's been pointing to the cake with her left hand, the only one with any use in it. A huge smile has been overspreading her face. Those big blue eyes have been twinkling.

"What've you been wanting?" says Linda Hussey, principal attendant on Lorraine's ward, Rehab 1. On her supper break, Linda slipped off grounds on a secret errand. Now she's back.

"Tell me. What've you been wanting?"

Lorraine points to her sign-board cake.

"Ta-da]" Linda places a hunk of fudge cake on Lorraine's tray.

"See it? Just like the picture."

Lorraine shakes her head, the very image of disappointment.

"What do you mean, no?"

Lorraine's face brightens.

She laughs.

Her head is going up and down now, yes] yes] yes]

"You're teasing again, woman," Linda says. "As much as you nagged me about that cake, you're going to eat it]"

Lorraine, never one to pass on a prank, is convulsed. When she's calmed down some, she struggles to get her fingers around the cake, but the slice is too big. Linda breaks it into bits.

"There," she says. "All bite-size pieces so you can pick it up. Looks like we're going to have to wash our hands after that. Goo city."

Later, Linda will muse. "I wonder sometimes what they dream. I wonder what they'd say if they woke up one morning and could talk."

Lorraine and me, 26 years ago.

Lorraine and me, 26 years ago.

Most born 'fragile'

Living with Lorraine are 26 men and women ranging in age from 23 to 68. All are profoundly retarded. All have some sort of physical disability. Most are what the physicians call medically fragile: prone to epileptic fits, digestive difficulties, heart problems, limb contractures, muscular atrophy.

Some can trace their disabilities to early-childhood accidents, but most came into the world with something wrong, a reminder of just how delicate human procreation is.

All but a handful have been at Ladd for years. Because of their multiple handicaps, which make placement in group homes more of a challenge than those less dependent, they are the last to go. They are the Final 200, members of a class that in Ladd's heyday, the mid-1960s, numbered more than 1,000.

Lorraine's world is a cinder block and brick building. It has three stories. Two have bedrooms, day rooms, bathrooms and dining areas. The basement has treatment centers for exercising and learning skills - putting pegs in boards, for example, or introducing new symbols onto Lorraine's most sophisticated board, which is up to 48 pictures now. On steamy summer days, there are enough air conditioners and fans on Rehab 1 to make things tolerable.

Aesthetics, a concept once alien to institutions, count.

Walls are painted pleasant shades of green and blue. Curtains and prints have been hung, fake potted plants put about, color TVs and VCRs and tape decks brought in. Every resident has a chest of drawers, a closet, his own shampoo, deodorant and soap. Beds have pillows and spreads and are made every morning.

It's a far cry from the days of Ladd's infamous back wards - days, not much more than a decade ago, when Lorraine slept in a crib, always wore a hospital johnny and spent her waking hours alone in a "vegetable cart," a wheelbarrowlike contraption inspired by what old-time peanut vendors pushed around. These were the days of isolation chambers and personal hygiene that consisted of herding excrement-covered people into cavernous tiled rooms and hosing them down.

Today, everyone has his or her own wardrobe, purchased with Social Security money. One man sports a Playboy T-shirt. Another wears one that proclaims: Professional Beach Bum. Red Sox, Patriots and Special Olympics motifs are standard. Lorraine likes dresses and skirts, typically in bright colors. But her most beloved dress is checkered gray.

"Her preppie look," Linda says.

The care-givers

As conditions at Ladd have slowly improved, the work load inevitably has increased.

From 7 a.m. until the day's over, frequently at 10 p.m. or later, the attendants - who often must work shorthanded - barely have time for the cigarettes most of them seem to smoke. They spoon-feed those residents, a majority, who cannot lift a fork. They change diapers. They do the laundry. They groom, shave, dish out ice cream treats, comfort, amuse, brush teeth, hold hands, dress, undress, tuck into bed. They keep incessant records: positioning charts, defecation charts, med and hygiene charts.

"All my life, I've found someone to take care of," says Chris Eidam, another attendant on Rehab 1. If Lorraine could speak, Chris believes, "she'd probably say, 'Thank you.' She's such a grateful person."

Today, Chris has dinner duty in one of Rehab 1's small dining rooms. Four residents are here. Only Lorraine can feed herself. Chris dishes her dinner - ground steak, mashed potatoes, pureed butternut squash - onto her plate. Lorraine starts to eat with a Teflon-coated spoon, which is easy on the teeth. Lorraine has a special handle and cup for drinking, but she doesn't like them. She prefers sandwiching a regular cup between lips and the back of her hand, even if the spill rate is significantly higher.

Chris's little sister was 4 when she collapsed, the victim of a rare blood disease. "I remember holding her in my lap, my mother trying to call an ambulance," Chris says. "She kept saying, 'My head] My head]' They tried surgery. She didn't make it. She was buried on my 13th birthday.

"Had she made it, she probably would have been here."

Lorraine is crying. She's gotten a taste of squash.

"Squash isn't anything to cry about," Chris says, but her reasoning doesn't impress Lorraine.

"What about those roses in your cheeks?" That's Chris's little ploy, telling Lorraine vegetables bring out good color.

Lorraine won't be persuaded.

"Okay." Chris scrapes the squash away.

"There. Now there isn't any."

Lorraine grins and gets back to work - more quickly, now that dessert, some sort of pudding, is that much nearer.

"She likes to read beauty magazines," Chris says. "I tell her those girls are so pretty because they eat their vegetables. She laughs. But only sometimes does it work."

Opened in 1908

The Exeter School for the Feeble-Minded opened in January 1908, when Dr. Joseph H. Ladd (for whom the institution would later be renamed) and eight "boys" moved into an old farmhouse on property that was about as far away from it all as one could get in turn-of-the-century Rhode Island.

The motivation was compassion - and, purportedly, protection. Exeter gave all its residents asylum and, for the "high grades," employment on a farm. The School for the Feeble-Minded gave greater Rhode Island a dumping ground.

Within 20 years, 430 people were "enrolled." Many were retarded. Many were not. Prostitutes, paupers, immigrants, thieves, "undesirables" of all stripes wound up in Exeter. Typically, their ticket was a form requiring only the signature of two doctors. More often than not, the ticket was one-way.

As early as the 1920s, accounts of abuse began circulating about Exeter, which the automobile was bringing closer to populated Rhode Island. Buildings were fire hazards. Wards were overcrowded. Health care was primitive. Sanitation was lacking. Residents were being beaten, some to death. Decades passed. The stories, many verified in Journal-Bulletin investigations, only got worse.

"You'd see people in feces and urine, lying in it," says Ed Brown, who began work at Ladd in 1962 and is still there, on Lorraine's ward.

"I remember a client who would bite. He was in a detention room 365 days a year, 24 hours a day. He'd been there for years. He had no wearing apparel, only a mattress and two sheets. One day, they let him out. They had a rope around his waist. He was out maybe half an hour and they brought him back."

Says Walter Kirk, 77, who was shipped off to Ladd in 1925 and is still there: "Danforth beat me with a rubber hose. I don't know why, myself. He was the boss. He's dead now."

The only option

In 1948, there was no help for a family such as the Bessettes. If a family couldn't make a go of it with their disabled newborn, Exeter was the only option.

"Due to present high cost of living, family having a difficult time to get along, although the father is employed steadily," one of Lorraine's pre-admission records states. "They are attached to the child but realize that it is for the best to have her institutionalized."

On Dec. 29, 1948, she was.

Lorraine's siblings, who lived in northern Rhode Island, were told by their father that their baby sister had died, according to Ladd officials. Lacking anyone to pay any attention to her, Lorraine would pass the next four decades in her crib and vegetable cart, with little but the walls to amuse her.

There is no test to tell how much of Lorraine's situation results from birth defects, how much is the inevitable product of so much numbness. One can only speculate where she might be if, like today's handicapped babies, she'd had intensive help - and been able to stay home.

"If she'd been given the benefit of early intervention," says Chris Eidam, "she would have gone so far. How far? I don't doubt that she could read."