G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 26

June 7, 2013

Your government spying on you

It has been an extraordinary week as London's The Guardian newspaper and The Washington Post have published top-secret documents revealing that the FBI and National Security Agency -- with the complicity and approval of Congressional intelligence committees, not to mention major U.S. corporations -- for years have been massively spying on U.S. citizens, whether suspected of criminal behavior or not.

The spying apparently extends to private telephone calls, emails, credit-card transactions, and Internet services provided by Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Skype, YouTube, Yahoo and AOL. And that's only what has come out so far.

Officials reacted with the lame observation that national security requires such erosion of privacy. Really? Secret orders from secret courts sound like... well, like George Orwell's dystopian novel 1984, as many have pointed out. It is all outrageous -- so outrageous that even the editorial board of The New York Times, which has supported President Obama on many issues, published a remarkable rebuke stating: "The administration has now lost all credibility on this issue. Mr. Obama

is proving the truism that the executive branch will use any power it

is given and very likely abuse it."

For a timeline of milestones in government surveillance since 9/11, read this excellent piece in Mother Jones.

Thank God for whistleblowers and a free press. The wisdom of the Founding Fathers in adopting the First Amendment is proved once again.

Like many other newspapers and media outlets, we at The Providence Journal will be examining this issue -- privacy v. security -- in greater detail in the weeks to come. It was already on our radar. For now, here's the local story we ran on P. 1 today alongside AP coverage of the story:

Balancing of security, rights urged

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: June 7, 2013

Page: MAIN_01

Section: News

Zone: MAIN

Edition: 1

PROVIDENCE - Disclosure that the National Security Agency is secretly

obtaining daily logs of phone calls made by Verizon customers brought a

comparison on Thursday to George Orwell's dystopian novel "1984," in

which "Big Brother" relentlessly spies on its citizens - whether they

are suspected of criminal behavior or not.

"The revelation that

the government has been secretly tracking the calls of potentially

millions of Verizon phone customers is shocking, but only the latest

example of the insidious growth of a surveillance state in this

country," Steven Brown, executive director of the Rhode Island Affiliate

of the American Civil Liberties Union, said Thursday.

"In the name of security and safety, the government is approaching Orwellian dimensions in its spying on ordinary people."

In

an interview, U.S. Sen. Jack Reed said Congress should convene hearings

into the reported surveillance and the general use of the Patriot Act,

under which the NSA apparently justified its data-gathering, with the

goal of "improvements" in the balance between Americans' right to

privacy and legitimate national security concerns.

"This is a topic that Congress should pursue," the Rhode Island Democrat said. "Hearings - absolutely."

The

revelation was published by The Guardian, a London newspaper that

obtained a copy of a top secret court order, issued two months ago by

the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a furtive U.S. government

body. The order requires Verizon Business Network Services to give the

NSA daily logs of information including the phone numbers, location data

and duration involved of all calls - regardless of whether the callers

are suspected of wrongdoing or not.

It is unknown if other U.S.

telecommunications companies, such as AT&T, are under separate

orders to supply logs to the NSA. The court order does not apply to the

content of the calls, which means the surveillance technically is not

wiretapping.

U.S. Rep. David N. Cicilline, D-R.I., was among the

members of Congress on Thursday who expressed serious concerns about

such indiscriminate surveillance.

"It is very disturbing to learn

that the National Security Agency reportedly required Verizon to turn

over information regarding the private communications of millions of

innocent Americans," Cicilline told The Providence Journal.

"The

federal government has a responsibility both to ensure our national

security and to maintain every citizen's essential right to privacy.

There has to be a better way - this level of sweeping surveillance has

no place in a free society and we should review this matter thoroughly."

Speaking

to The New York Times on Thursday, an unnamed senior official in the

Obama administration defended the gathering of phone information under a

contested section of the Patriot Act.

"Information of the sort

described in the Guardian article has been a critical tool in protecting

the nation from terrorist threats to the United States," the official

told the paper. (In a remarkable rebuke, the paper's editorial board

Thursday afternoon posted an editorial that said with the Verizon

disclosure, "the administration has now lost all credibility.")

The

"critical tool" sentiments were echoed by Daniel Castro, senior analyst

with the nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based Information Technology

& Innovation Foundation.

"Government should use data to fight

terrorism. One of the major failures pre-9/11 was the inability to

'connect the dots,' " Castro told The Journal. "Using meta-data such as

phone records is a useful way to identify networks of individuals … .

From a privacy perspective, this is also better than listening in on

phone calls. Data analytics alone won't stop terrorism, but it should be

one tool available to law enforcement officials."

Castro, however, questioned why the surveillance had not been publicly disclosed by the government.

"Most

Americans didn't know this was happening," he said. "There's nothing

intrinsically wrong with collecting and using this type of data on a

large scale, but there doesn't seem to be a good reason to do it in

secret."

Said David Barrett, professor with Villanova University's department of political science:

"A

program which is known to high officials of the executive branch and to

the two congressional committees on intelligence is not what I would

call Big Brother. I have assumed something like this has been going on

since the passage of the Patriot Act. Notice that this particular order

does not authorize monitoring of the content of such phone calls. That

would take additional authorization."

In a statement to The Journal, U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse urged balance between security and privacy.

"As

a former member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, I can't comment

extensively on these news reports, since they relate to classified

information to which I may have been exposed," the Rhode Island Democrat

said.

"That said, when looking at programs of this nature it is

always important to ensure that our nation is protecting both civil

liberties and national security. I have always worked to make sure the

actions of our government are consistent with both goals, and I will

continue to do so."

The ACLU's Brown was more emphatic.

"This

latest disclosure highlights the need for strong action at both the

state and federal level to address these increasing encroachments on

basic privacy rights," he said.

"We can no longer pretend that

our privacy is safe from indiscriminate government snooping. We hope

that steps will be taken to restore some semblance of our right to

privacy in the face of technological advances that are so easily able to

eradicate it."

The spying apparently extends to private telephone calls, emails, credit-card transactions, and Internet services provided by Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Skype, YouTube, Yahoo and AOL. And that's only what has come out so far.

Officials reacted with the lame observation that national security requires such erosion of privacy. Really? Secret orders from secret courts sound like... well, like George Orwell's dystopian novel 1984, as many have pointed out. It is all outrageous -- so outrageous that even the editorial board of The New York Times, which has supported President Obama on many issues, published a remarkable rebuke stating: "The administration has now lost all credibility on this issue. Mr. Obama

is proving the truism that the executive branch will use any power it

is given and very likely abuse it."

For a timeline of milestones in government surveillance since 9/11, read this excellent piece in Mother Jones.

Thank God for whistleblowers and a free press. The wisdom of the Founding Fathers in adopting the First Amendment is proved once again.

Like many other newspapers and media outlets, we at The Providence Journal will be examining this issue -- privacy v. security -- in greater detail in the weeks to come. It was already on our radar. For now, here's the local story we ran on P. 1 today alongside AP coverage of the story:

Balancing of security, rights urged

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: June 7, 2013

Page: MAIN_01

Section: News

Zone: MAIN

Edition: 1

PROVIDENCE - Disclosure that the National Security Agency is secretly

obtaining daily logs of phone calls made by Verizon customers brought a

comparison on Thursday to George Orwell's dystopian novel "1984," in

which "Big Brother" relentlessly spies on its citizens - whether they

are suspected of criminal behavior or not.

"The revelation that

the government has been secretly tracking the calls of potentially

millions of Verizon phone customers is shocking, but only the latest

example of the insidious growth of a surveillance state in this

country," Steven Brown, executive director of the Rhode Island Affiliate

of the American Civil Liberties Union, said Thursday.

"In the name of security and safety, the government is approaching Orwellian dimensions in its spying on ordinary people."

In

an interview, U.S. Sen. Jack Reed said Congress should convene hearings

into the reported surveillance and the general use of the Patriot Act,

under which the NSA apparently justified its data-gathering, with the

goal of "improvements" in the balance between Americans' right to

privacy and legitimate national security concerns.

"This is a topic that Congress should pursue," the Rhode Island Democrat said. "Hearings - absolutely."

The

revelation was published by The Guardian, a London newspaper that

obtained a copy of a top secret court order, issued two months ago by

the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a furtive U.S. government

body. The order requires Verizon Business Network Services to give the

NSA daily logs of information including the phone numbers, location data

and duration involved of all calls - regardless of whether the callers

are suspected of wrongdoing or not.

It is unknown if other U.S.

telecommunications companies, such as AT&T, are under separate

orders to supply logs to the NSA. The court order does not apply to the

content of the calls, which means the surveillance technically is not

wiretapping.

U.S. Rep. David N. Cicilline, D-R.I., was among the

members of Congress on Thursday who expressed serious concerns about

such indiscriminate surveillance.

"It is very disturbing to learn

that the National Security Agency reportedly required Verizon to turn

over information regarding the private communications of millions of

innocent Americans," Cicilline told The Providence Journal.

"The

federal government has a responsibility both to ensure our national

security and to maintain every citizen's essential right to privacy.

There has to be a better way - this level of sweeping surveillance has

no place in a free society and we should review this matter thoroughly."

Speaking

to The New York Times on Thursday, an unnamed senior official in the

Obama administration defended the gathering of phone information under a

contested section of the Patriot Act.

"Information of the sort

described in the Guardian article has been a critical tool in protecting

the nation from terrorist threats to the United States," the official

told the paper. (In a remarkable rebuke, the paper's editorial board

Thursday afternoon posted an editorial that said with the Verizon

disclosure, "the administration has now lost all credibility.")

The

"critical tool" sentiments were echoed by Daniel Castro, senior analyst

with the nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based Information Technology

& Innovation Foundation.

"Government should use data to fight

terrorism. One of the major failures pre-9/11 was the inability to

'connect the dots,' " Castro told The Journal. "Using meta-data such as

phone records is a useful way to identify networks of individuals … .

From a privacy perspective, this is also better than listening in on

phone calls. Data analytics alone won't stop terrorism, but it should be

one tool available to law enforcement officials."

Castro, however, questioned why the surveillance had not been publicly disclosed by the government.

"Most

Americans didn't know this was happening," he said. "There's nothing

intrinsically wrong with collecting and using this type of data on a

large scale, but there doesn't seem to be a good reason to do it in

secret."

Said David Barrett, professor with Villanova University's department of political science:

"A

program which is known to high officials of the executive branch and to

the two congressional committees on intelligence is not what I would

call Big Brother. I have assumed something like this has been going on

since the passage of the Patriot Act. Notice that this particular order

does not authorize monitoring of the content of such phone calls. That

would take additional authorization."

In a statement to The Journal, U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse urged balance between security and privacy.

"As

a former member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, I can't comment

extensively on these news reports, since they relate to classified

information to which I may have been exposed," the Rhode Island Democrat

said.

"That said, when looking at programs of this nature it is

always important to ensure that our nation is protecting both civil

liberties and national security. I have always worked to make sure the

actions of our government are consistent with both goals, and I will

continue to do so."

The ACLU's Brown was more emphatic.

"This

latest disclosure highlights the need for strong action at both the

state and federal level to address these increasing encroachments on

basic privacy rights," he said.

"We can no longer pretend that

our privacy is safe from indiscriminate government snooping. We hope

that steps will be taken to restore some semblance of our right to

privacy in the face of technological advances that are so easily able to

eradicate it."

Published on June 07, 2013 06:55

June 4, 2013

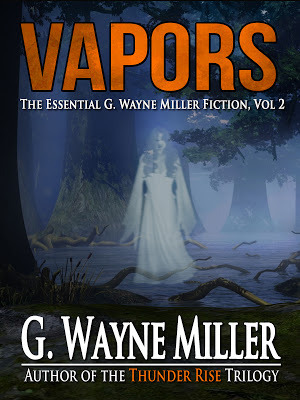

"Vapors," v. 2 of the collected short stories, soon to be published

Updated, refreshed, edited and otherwise made ready for publication (and republication), a second set of my collected short stories is soon to appear in

Vapors, The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, Vol 2

. And once again, designer David Dodd, of publisher Crossroad Press, has knocked it out of the park. Check out this cover. I'll post the link to Kindle when it goes up, but meanwhile, Since the Sky Blew Off, Vol 1 in the collected stories, may be of interest. A similar mix of horror, sci-fi, mystery and crime.

Another great David Dodd cover! This dude's got it, folks.

Another great David Dodd cover! This dude's got it, folks.

Published on June 04, 2013 08:34

May 31, 2013

Bob Whitcomb retires from Providence Journal

After 43 years in journalism -- 32 of them at The Providence Journal -- Bob Whitcomb retired today as vice president and editor of the editorial pages. He will be missed here at 75 Fountain Street -- but we will be seeing him in many other places (and on the op-ed pages) as he continues with his writing. And also at Salve Regina Univerity's Pell Center, where he will be an adjunct fellow. He already is a governor with The Pell Center's Story in the Public Square program.

I have known Bob since 1981, when I arrived at the projo and he was soon to depart for Paris, where he became an

editor for the International Herald Tribune. Five years later, he came back. Best of luck, Bob! Ed Achorn is replacing Bob, as

Bob Whitcomb in his fourth-floor office, May 31, 2013.

Here is the story about Bob that my colleague Tom Mooney wrote for last Sunday's paper:

Media | Editorial page editor to retire but will write column

TOM MOONEY

Publication Date: May 26, 2013

Page: MAIN_06

Section: News

Zone: MAIN

Edition: 1

PROVIDENCE - Robert B. Whitcomb, the erudite and good-humored editorial

pages editor for The Providence Journal for the last 21 years and one of

the newspaper's vice presidents, is retiring at the end of this month.

Whitcomb,

65, said he is stepping down now to "try other things." One of them

will be as a regular guest contributor on the editorial pages that he

has overseen - writing a column every other week on "a wide range of

topics representing my existential angst."

Whitcomb, who worked

for 32 years at The Journal, has been a vice president at the newspaper

since 1997 and in charge of its editorial pages since 1992.

"Bob

Whitcomb has had a stellar 43-year career in journalism," said Howard G.

Sutton, publisher, president and chief executive officer of The

Providence Journal Co. "For the last 21 years he has produced some of

the finest editorial pages in the country for The Providence Journal.

"He

leaves behind a sterling record of service to the newspaper and to

Southern New England, as an advocate for better government, a fan of

alternative energy, a strong supporter for economic development and a

skeptic of big business."

Whitcomb first joined The Journal in

1976 after writing and editing stints at the Boston Herald Traveler, the

Wilmington (Del.) News Journal and The Wall Street Journal, in New

York. He left The Providence Journal at the end of 1982 to become an

editor for the International Herald Tribune, based in Paris, and

returned to The Journal in 1987, serving as acting Sunday managing

editor before moving upstairs in 1989 to begin writing editorials.

Whitcomb championed having a wide range of voices on the editorial and opinion pages.

"I'm not one who believes a paper like this should have just local

news," he said in a recent interview. "It should give you a view of the

world. And not just from where you are sitting."

Whitcomb has had

a ringside seat to revolutionary changes in the media in recent years

as more people turn to news online. Besides the reduction of reporters

gathering the news and asking questions, "the most distressing thing to

me," Whitcomb said, has been "the triumph of process over content which

permeates most of the media now," the emphasis of story display over

proper writing and editing.

"I think in the next five years, we

will kind of reinvent ourselves…. In the interim I worry about quality

journalism. You can see the effect, the decline in civic discourse in

civil society."

But reality being what it is, Whitcomb said, "it's like complaining that rocks are hard."

Whitcomb,

a 1970 Dartmouth College graduate, co-authored a book in 2008 about the

various interests surrounding the Cape Cod wind farm project. He says

he has a couple of other writing projects in mind, including perhaps

another book, historical in nature.

He also plans to help a friend who is making a documentary about the OSS, the predecessor to the CIA.

Whitcomb and his wife, Nancy, live in Providence and have two adult daughters.

"I

have a very strong sense of clocks, of running out of time," Whitcomb

said. "A lot of people in my family have died pretty young, so I think

about that and think about having enough time to try other things. I

will miss some of the absurdities of this business, some of the humor,

the craziness, the unpredictability…. But like everyone in the business,

five minutes after I leave, everyone will forget that I was here. So

there is a wonderful transient nature to this business."

I have known Bob since 1981, when I arrived at the projo and he was soon to depart for Paris, where he became an

editor for the International Herald Tribune. Five years later, he came back. Best of luck, Bob! Ed Achorn is replacing Bob, as

Bob Whitcomb in his fourth-floor office, May 31, 2013.

Here is the story about Bob that my colleague Tom Mooney wrote for last Sunday's paper:

Media | Editorial page editor to retire but will write column

TOM MOONEY

Publication Date: May 26, 2013

Page: MAIN_06

Section: News

Zone: MAIN

Edition: 1

PROVIDENCE - Robert B. Whitcomb, the erudite and good-humored editorial

pages editor for The Providence Journal for the last 21 years and one of

the newspaper's vice presidents, is retiring at the end of this month.

Whitcomb,

65, said he is stepping down now to "try other things." One of them

will be as a regular guest contributor on the editorial pages that he

has overseen - writing a column every other week on "a wide range of

topics representing my existential angst."

Whitcomb, who worked

for 32 years at The Journal, has been a vice president at the newspaper

since 1997 and in charge of its editorial pages since 1992.

"Bob

Whitcomb has had a stellar 43-year career in journalism," said Howard G.

Sutton, publisher, president and chief executive officer of The

Providence Journal Co. "For the last 21 years he has produced some of

the finest editorial pages in the country for The Providence Journal.

"He

leaves behind a sterling record of service to the newspaper and to

Southern New England, as an advocate for better government, a fan of

alternative energy, a strong supporter for economic development and a

skeptic of big business."

Whitcomb first joined The Journal in

1976 after writing and editing stints at the Boston Herald Traveler, the

Wilmington (Del.) News Journal and The Wall Street Journal, in New

York. He left The Providence Journal at the end of 1982 to become an

editor for the International Herald Tribune, based in Paris, and

returned to The Journal in 1987, serving as acting Sunday managing

editor before moving upstairs in 1989 to begin writing editorials.

Whitcomb championed having a wide range of voices on the editorial and opinion pages.

"I'm not one who believes a paper like this should have just local

news," he said in a recent interview. "It should give you a view of the

world. And not just from where you are sitting."

Whitcomb has had

a ringside seat to revolutionary changes in the media in recent years

as more people turn to news online. Besides the reduction of reporters

gathering the news and asking questions, "the most distressing thing to

me," Whitcomb said, has been "the triumph of process over content which

permeates most of the media now," the emphasis of story display over

proper writing and editing.

"I think in the next five years, we

will kind of reinvent ourselves…. In the interim I worry about quality

journalism. You can see the effect, the decline in civic discourse in

civil society."

But reality being what it is, Whitcomb said, "it's like complaining that rocks are hard."

Whitcomb,

a 1970 Dartmouth College graduate, co-authored a book in 2008 about the

various interests surrounding the Cape Cod wind farm project. He says

he has a couple of other writing projects in mind, including perhaps

another book, historical in nature.

He also plans to help a friend who is making a documentary about the OSS, the predecessor to the CIA.

Whitcomb and his wife, Nancy, live in Providence and have two adult daughters.

"I

have a very strong sense of clocks, of running out of time," Whitcomb

said. "A lot of people in my family have died pretty young, so I think

about that and think about having enough time to try other things. I

will miss some of the absurdities of this business, some of the humor,

the craziness, the unpredictability…. But like everyone in the business,

five minutes after I leave, everyone will forget that I was here. So

there is a wonderful transient nature to this business."

Published on May 31, 2013 08:31

May 23, 2013

Short story "All My Children" and interview on new Blackout City/Dark Dreams podcast

Horror aficionado and entrepreneur Mark Slade has brought a second short story from the Since the Sky Blew Off collection to podcast. Following on the heels of the fine narration of "We Who are His Followers" comes the 'cast of "All My Children," a horror/crime tale.

Listen to the podcast at Mark's Blackout City page. "All My Children" starts at the 14:45 mark of Episode 3: Darkness and Light.

"Stalking G. Wayne Miller," an interview Mark conducted with me is also on the same Blackout City page. We talk about many things, but mostly writing -- some good advice for young writers trying to break in, as I myself was many years ago as I was starting out. I know that rough road well!

"We Who are His Followers" can be heard at Mark's Dark Dreams podcast site. Starts at the 10:08 mark.

As Mark and the folks at Crossroad Press bring more of my short- and long-form fiction to new audiences, I am drawn to my archives -- to the magazines in which some of my short stories originally appeared. While I believe it has stood the test of time, "All My Children" was first published in 1988 in Violent Legends, a magazine published by writer and poet Joey Froehlich. For a glimpse into what things were like back then, before the Internet, when I was trying to break through -- young writers today, take note! -- look at the cover of that issue, and the first page of my story as it appeared. I do not recall if this was the only issue ever published, and I have tried without success to track Joey down. If you're out there, man, please drop me a line!

The cover of Violent Legends, horror zine in 1988.

First page of my story. It was typed!

Published on May 23, 2013 15:34

Short story "All My Children" and interview on new Blackout City Podcast

Horror aficionado and entrepreneur Mark Slade has brought a second short story from the Since the Sky Blew Off collection to podcast. Following on the heels of the fine narration of "We Who are His Followers" comes the 'cast of "All My Children," a horror/crime tale.

Listen to the podcast at Mark's Blackout City page. "All My Children" starts at the 14:45 mark of Episode 3: Darkness and Light.

"Stalking G. Wayne Miller," an interview Mark conducted with me is also on the same Blackout City page. We talk about many things, but mostly writing -- some good advice for young writers trying to break in, as I myself was many years ago as I was starting out. I know that rough road well!

"We Who are His Followers" can be heard at Mark's Dark Dreams podcast site. Starts at the 10:08 mark.

As Mark and the folks at Crossroad Press bring more of my short- and long-form fiction to new audiences, I am drawn to my archives -- to the magazines in which some of my short stories originally appeared. While I believe it has stood the test of time, "All My Children" was first published in 1988 in Violent Legends, a magazine published by writer and poet Joey Froehlich. For a glimpse into what things were like back then, before the Internet, when I was trying to break through -- young writers today, take note! -- look at the cover of that issue, and the first page of my story as it appeared. I do not recall if this was the only issue ever published, and I have tried without success to track Joey down. If you're out there, man, please drop me a line!

The cover of Violent Legends, horror zine in 1988.

First page of my story. It was typed!

Published on May 23, 2013 15:34

Vote now! Help choose the title of my next short story collection.

Once we settle on the cover art, my good friends at Crossroad Press will be publishing the second volume of my collected short stories, a year after they brought out the first, SINCE THE SKY BLEW OFF.

And I'd like your help in choosing the title. Here are your choices:

-- VAPORS

or

-- NOTHING THERE

Each is also the name of a story that will be included in the collection. Please cast your vote on my Facebook page, or send me an email.

It's not necessary to read either story to vote, nor even to know the genres -- in fact, I am hoping for your immediate, instinctive response. Which rings better to your ear: Vapors or Nothing There?

For the record, these are horror, mystery and sci-fi stories, like those in SKY.

If you would like to read "Vapors," however, follow this link.

And if you'd like to read "Nothing There," originally published in the late David Silva's legendary 1980s and '90s magazine The Horror Show, scroll down past the original art that appeared with the story. Illustration © copyright 1987 Chris Pelletiere.

Nothing There

© copyright 1987 and 2013 G. Wayne Miller

He drove north from Chicago in a rented Honda.

The Saturday afternoon traffic was thick and sluggish, like blood through

diseased arteries. How polite these drivers seemed. Back in Boston, you

couldn't go a block without some idiot trying to nail you. Here, folks signaled

when passing. They stayed close to the speed limit. No one tailgated. He

supposed it was part of their Midwestern nature to be so courteous. He wondered

momentarily what kind of world it would be if everyone were like them.

Before long, the factories and tenements

had thinned and then disappeared. The jets in and out of O'Hare had shrunk to

distant specks. He passed an amusement park, closed for the season. He saw

transmission lines coming down from Canada. It was suburbia now, 7-11 stores

and neat little lawns fronting neat little houses. Soon they, too, had faded.

Farmhouses took their place. Cornfields and dairy cattle. Silos, rigid and

tall, guardians of this rich black soil. He crossed the line and he was in

Wisconsin. From here, she'd said, it was only another half hour.

The traffic was weaker now. The November

day was, too. High, thin clouds spread across the measureless sky. Another

hour, and the sun would be swallowed by the fields. At kitchen tables, dinner

would be served. He imagined seeing aproned housewives, their hair done up in

curlers and kerchiefs, bending over ovens where hamburger casseroles simmered.

He imagined hearing the children, giddy with the thought of Saturday night, and

the tired husbands, ready for their evening of rest.

Overhead, the sign said County K, one mile.

What a funny name for a road, he thought. County K, like some new brand of

cereal. He looked down at the directions he'd scribbled on hotel stationery.

Yes, this was it. He eased over into the travel lane, slowed and left

Interstate 94. There was the 76 truck stop, just as she'd said. A combination

restaurant, gift shop and Greyhound bus stop. A parking lot full of full-sized

Fords and Chryslers, with hardly a Toyota in sight. The heartland.

He'd called her after lunch from his hotel

room. The first few minutes had been awkward for them both. He could hear the

sounds of kids in the background. He told her about his convention. She talked

about the weather, unseasonably mild, and unlikely to last, considering

Thanksgiving was just around the corner.

``Where are you staying?'' she'd asked.

``The Palmer House.''

``Very fancy.''

``It's OK.''

``No, it's fancy,'' she insisted. ``I've

been there. Window- shopping in that big lobby.''

``They have some nice shops.''

``You've done all right for yourself, John,''

she said, trying to mask her bitterness. A trace still showed. ``You always

did.''

He didn't answer. Didn't know what he could

have said if he'd tried.

``So how'd you find me?'' she asked after

shouting at the children to be quiet, Mommy's got a very special call.

``The alumni office.'' They'd been the same

class, the class of '96. He'd gone back east after graduation. She'd gone home

to Wisconsin, never expecting to hear from him again.

``It's funny.''

``What?''

``That you tracked me down. I tried to find

you, you know.''

He didn't. But it didn't surprise him.

There was a time he'd actually dreaded her call, but that had passed. During

the period he was married, he'd almost forgotten her. It wasn't until after his

divorce that he'd thought much about her again.

``I tried several times, as a matter of

fact,'' she continued. ``I wrote letters. They kept coming back.''

``I've moved a lot,'' he said. ``The

company.''

``It doesn't matter now.''

There was another pause. The words weren't

coming easily from either of them.

``I'm divorced, you know,'' she said after

a bit.

``I know. I am, too.''

``I've got two children. That's who you

hear running around. A boy and a girl.''

``I know,'' he repeated dumbly.

``You seem to have done your homework,'' she

said, and he couldn't tell if she was mad or not.

``It's all on record at the alumni

office,'' he explained. ``Anyone can get it by calling.''

``Did they tell you they were both

adopted?'' she asked.

``No.''

``After Bryce, I couldn't have children. Of

my own.''

Bryce, he thought. So that's what she called him. Why did she even bother to name him?

What could it matter?

``I'm sorry,'' he said. He wished he had a

glass of water to get rid of the dryness in his mouth.

``I am, too.'' He was surprised at how cold

her voice had turned. How suddenly. He didn't remember her like that. He

remembered her as soft, pretty, the youngest-looking girl sitting at the back

of Economics 101 the morning he first set eyes on her.

``I'm really sorry.''

``Sure.''

There was silence again. It was a bad cell,

and he could hear static through the phone.

The child had been stillborn. That much

he'd heard years ago from a friend of a friend of a friend. There had been whispers

of some horrible deformity, but he'd never been able to confirm that, never

bothered to try. What would have been the gain? What was done was done. All he

knew for sure was that Sheryl had carried the baby to term, and he'd come out

blue and unbreathing. There was a question of medical malpractice. As far as he

knew, it had never come to a suit. That wouldn't have been like her. This had

all happened that September, three months after he'd said goodbye.

``So why'd you call, John?'' she asked,

breaking the silence.

He'd been ready for this one, but he still

didn't have a good answer. Just some private feelings he couldn't share because

he wasn't sure what they meant, if they meant anything at all.

``I just thought I should,'' he said.

``I've been thinking about it for a long time.''

``Do you want to see him?'' she asked. ``I

think you should see him. Just once. It wouldn't have to be for long.''

He had no idea what she was talking about.

``Who?''

``Bryce. His grave, I mean.''

What a strange idea, he thought. Perverse.

Again, the pause was long, uncomfortable. He wished desperately that the call

was over, but he saw no way of ending it. It was up to her now.

``I could tell you how to get there. It's

not even two hours from Chicago.''

``I--''

``I think you should, John,'' she said

sternly. ``I think you owe him at least that. Him and me. Respect for the

memory. Respect for the past.''

``Yes,'' he finally said. ``I'd like to.''

She gave him directions. He was reading

them again now after stopping at the restaurant to use the men's room. County K

six miles west to an intersection. Right on Rowe's Lane about a mile to a seed

farm. The cemetery would be just over the next knoll. You can't miss it, she'd

said. It's on the highest land around.

He rolled the window down and put the car

in gear.

Night wasn't far off, but it seemed to have

warmed up since leaving Chicago. The air on his face felt refreshing, like a

shower after a bad night's sleep. For some reason, he'd been getting

increasingly anxious the last few miles. Strung out. He could feel the excess

nervous energy running up and down his body. It was like having too many cups

of coffee. His palms were actually sweaty. For the first time since talking to

her, he wondered what exactly he'd gotten himself into, and why. He didn't have

the answers. That bothered him more than anything. He'd gotten where he had in

business by coming up with answers.

County K, a two-lane blacktop, wound off

toward the setting sun. There was almost no traffic, only an occasional tractor

or pickup truck or stainless-steel tanker carrying milk destined to become

butter or cheese. The only buildings were farmhouses and barns. It seemed

everyone was flying an American flag. In the Ivy-League East, patriotism

smacked too much of Tea Party politics to be worn on the sleeve. Here, it fit.

He found the cemetery without any trouble.

From this knoll, you could see for miles and miles over the rolling

countryside. It reminded him of a Grandma Moses painting, the fields and

outbuildings arranged like patchwork.

He got out of the car and paused a moment,

surveying the cemetery.

It was unexpectedly tiny, a postage stamp

of graveyards. The only smaller one he recalled ever seeing was one near

Concord, Mass., where a handful of Revolutionary War heroes were buried

together under white headstones whose inscriptions had worn off over the years.

He counted, unconsciously using his finger as a measure. There couldn't be more

than a dozen families buried here. One of them was hers, the Andersens. He

remembered her telling the story of how the family had come over from Sweden

during the great wave of Scandinavian immigration a century ago. They'd been

carpenters and masons, these Andersens, and they'd done all right for

themselves in the New Land.

The wind had picked up since the truck stop

and it was insistent now, brisk but not harsh. In a few short weeks it would

deliver the sleet and the snow, but today, on the cusp of fall, it brought only

a final reminder of summer. In great sheets, it came whipping across the flat landscape,

fragrant with a sweet agricultural odor he did not recognize. He stood, letting

the wind caress him. He looked out over the stones, the torn veterans' flags,

potted geraniums wilted by the autumn's first frost. The cemetery was

surrounded by fields. They were brown, their life gone silently underground to

await a more encouraging season.

The heartland. He'd probably eaten food

grown around here, maybe from one of these very fields.

Carrying the green bag he'd picked up in the

Palmer House lobby, he opened the rusted iron gate and walked uncertainly into

the cemetery. That shaky feeling had returned. His lips were dry. He felt

suddenly alone, inexplicably embarrassed, like the man in the dream who finds

himself in public without any clothes. Let's get it over with and get out of

here, he thought. He went directly to the Andersen plot, past the Birds, the

Bergmans, the Mondales, the Thompsons. The featured Andersen stone was a

towering obelisk, at least twice his height, cut from what appeared to be gray

marble, polished and mirror-smooth. The shadow from a leafless tree fell across

it in an abstract pattern. Somebody had paid a small fortune for this display,

he could tell that. He remembered her father, Ambrose Andersen, a tall, stern

man he'd met once. Andersen had made a small fortune in construction, and like

many newly wealthy people, he enjoyed spending. He'd probably footed the bill.

Laid out in front of the obelisk were

perhaps 25 flat stones, each roughly the size of a hardcover dictionary. All

that had been inscribed on any of them were names and the two most important

years in anyone's existence. ``Mother, 1845-1912.'' ``Father, 1840-1905.''

``Henry, 1884-1944,'' and so forth. On the extreme left-hand perimeter of the

Andersen territory, almost into the Birds', was the stone he was looking for.

``Baby Bryce,'' it read, ``1996-1996.''

He opened the green bag and laid what was

in it, a single white rose, atop the stone. His fingers were clumsy, his breath

more labored than it should have been. He didn't have any of the thoughts he

had expected would be haunting him right now; maybe they would come on the

return trip to Chicago, or the plane home tomorrow to Boston. Nothing about

what might have been, how he might have been playing Little League baseball,

what he might have looked like, what his favorite subject in school might have

been. None of that. Only a nagging sensation of having done wrong, and never

being able to make contrition, even if he wanted to.

He didn't hear the pickup. Didn't see her

approach from the field.

When he looked up, she was there, barely 20

feet away.

He looked at her, startled initially. Time

had gotten to her. It had to him, too, he couldn't kid himself. She looked

unkempt, haggard, as if she never got enough sleep any more. Her clothes looked

freshly laundered but worn, as if she'd had them too long. For an instant,

their eyes locked. It was impossible to say what was exchanged between them in

that moment. Recognition, but more. Loneliness. A glimmer of what might have

been, perhaps. A rush of memories, none well defined. Then it was gone. Her

eyes went as cold as the gathering evening. There was nothing to say.

She came closer. He didn't move. He hadn't

expected it to play out like this.

They embraced. For his part, it was

instinctive. Reflexive. There was no more thought to it than drawing a breath.

She was warm, her breath intoxicating. Through her coat, he could feel the

swell of her breasts. Suddenly, the memories had taken on sharp definition. Now

he remembered them making love the first time, the way he'd eased inside her,

the softly building passion that had finally exploded one Saturday evening when

his roommate was away.

He didn't see her knife.

She plunged it into the back of his neck.

The first blood fell in perfect splatters

on Baby Bryce's stone, like drops of wax from a flaming red candle. It was only

a surface wound, calculated and deliberate. Alone, it might have stopped

bleeding. He wasn't even sure at first that he'd been stabbed. He thought maybe

she'd dug her fingernails into him. The tenderness he'd started to feel escaped

him like steam. He was tempted to slap her. He'd never wanted to hit a woman

before. He did now. Self-defense. But he didn't. He turned, headed for the car.

A trickle of warmth ran down the inside of his shirt. The crazy fucker.

She roared toward him, her cutting arm a

scythe of blurred motion. This time he saw the blade. It was a pocket knife,

the kind young punks smuggle into school. The blade couldn't have been four

inches long. In that instant of confused terror, he remembered something his

mother had told him as a kid. It wasn't about knives. It was about drowning.

You can drown anywhere there's water, she'd said. Even in your own bathtub,

even in an inch of water.

This time, she connected only once, a long,

violent gash that sliced through his coat sleeve into his forearm. The fabric

was quickly moist from the inside out. The pain was immense. She meant to kill

him. It was like being kicked in the stomach, realizing that, but he knew it

was true. He was suddenly breathless, fevered. With his good arm, he grabbed

his wounded one, holding it fiercely, as if that would stop the bleeding. She

came at him again. For a second, he saw her eyes. There was nothing there but

emptiness. He ducked to one side, and she charged past him, almost falling.

He hesitated. For a second, he thought of

fighting back. He was bigger than she, stronger. And she was out of her mind, a

crazed psychotic with a knife. He looked wildly around, but there was nothing

he could use as a weapon, no branch or loose rock. The best bet was to get the

hell away. The bleeding wasn't bad, but he'd have to see a doctor. Then he

would go to the police and have the crazy fucker arrested. That's what he was

going to do, goddamn it. Have her put behind bars for good.

He took a step, a step that brought his

foot into contact with Baby Bryce's stone.

He felt something lock around his ankle.

Tiny, vice-like.

He looked down. There was nothing there, of

course, only grass and that flat polished marble stone, blending into the

shadows of approaching evening. He could taste bile as his panic rose.

He tried to move.

He was locked in place.

``What the--''

She was back, blade whistling. Her aim was

more precise than before. He saw the knife, heard it, tried to roll out of its

trajectory, but his foot was stuck. He did the best he could, twisting and

squirming to one side. It was not enough.

She made contact, again and again. His

shoulder. His side. His thigh. His right hand. He felt each cut. None was

deeper than tendon level. It was more like being pricked with a needle or stung

by hornets than being stabbed. After each cut, the warm moisture. Death by a

thousand cuts.

His ankle.

He grabbed at it, like a

mink caught in a leg hold trap. There was nothing there, of course. With his

other hand, he tried frantically to fend her off. She was nimble. She seemed

able to anticipate him, dodging when he lashed out, closing back in when he

tried unsuccessfully to get to his feet.

Maybe he could crawl. In his panic, that

new thought was delightful. It was like being born again. He was on his belly

and maybe he could crawl. Maybe he'd broken his ankle, that was all, and he

could slither away from her.

But he couldn't crawl, not more than a few

inches. His foot was frozen.

She was in no hurry. There was still plenty

of daylight remaining, 15 minutes or more until blackness settled over them.

She was nicking him. Little flicks of cuts, counting toward a thousand. It was

uncanny how she kept missing all the major arteries and organs, the ones that

would have ended it quickly. She seemed to know anatomy, seemed to have studied

it until she was sure what to hit, what to avoid. He was bleeding everywhere

but gushing nowhere. His central nervous system only gradually was shifting

into shock.

The pain was building. Soon it was too big

for screaming. He began to moan. A mortally wounded animal sound, back through

the millennia to when ancestors walked on all fours. Hunter and prey. Victor

and vanquished.

His vision blurred.

As consciousness drained away to

nothingness, he thought he saw her.

Smiling, her face inches from his.

He thought he heard a new sound.

The sound of a newborn crying.

The sound of birth.

Published on May 23, 2013 05:28

May 7, 2013

Audible potpouri

More of my writing, new and old, keeps finding its way into additional formats. Previous publishers are issuing new e-editions, and my partners today at the multi-platform, multi-genre Crossroad Press have joined in that effort -- with books and stories that span my professional career, from old to brand-new, notably the finally completed Thunder Rise trilogy of horror/mystery novels and Since the Sky Blew Off, first of a planned three volumes of my horror/mystery/sci-fi short stories. (Read "The Beach That Summer," from the forthcoming v. 2, Vapors.)

Now come the audio (and video) productions, of various works, from multiple sources:

Thunder Rise, first in the trilogy (with Asylum and Summer Place, is now an audible book.

The earlier audible version of King of Hearts, from Random House, remains available.

Also now on audible is The Work of Human Hands, my first non-fiction book. .

A podcast of "We Who Are His Followers," from the Sky collection, is now available as a podcast (starts at 10:08 mark) from Mark Slade's Dark Dreams. More stories will be available on Dark Dreams soon.

A podcast about Toy Wars and G.I. Joe on JoeDeclassified: Special Ops went up in January 2013.

And you can watch an interview with me on writing from a few years ago, by my son, Calvin.

Now come the audio (and video) productions, of various works, from multiple sources:

Thunder Rise, first in the trilogy (with Asylum and Summer Place, is now an audible book.

The earlier audible version of King of Hearts, from Random House, remains available.

Also now on audible is The Work of Human Hands, my first non-fiction book. .

A podcast of "We Who Are His Followers," from the Sky collection, is now available as a podcast (starts at 10:08 mark) from Mark Slade's Dark Dreams. More stories will be available on Dark Dreams soon.

A podcast about Toy Wars and G.I. Joe on JoeDeclassified: Special Ops went up in January 2013.

And you can watch an interview with me on writing from a few years ago, by my son, Calvin.

Published on May 07, 2013 12:01

May 2, 2013

The Thunder Rise trilogy, finis!

In 1989, when William Morrow published my first book, the horror/mystery novel

Thunder Rise,

I envisioned it as the first in a trilogy set in the area around a fictional mountain in real-life Berkshire County, Massachusetts. In the last few months, I have completed writing the last two.

And thanks to my good friends at Crossroad Press, Asylum and Summer Place are now in print and Thunder Rise is also an audio book. Details on all editions of the three books are at my books page -- along with details about Since The Sky Blew Off, the first volume, of a planned three, of my collected horror/mystery/sci-fi stories, some previously published, some now for the first time. (Read The Beach That Summer, from Vapors, the upcoming Volume 2.)

The beginning of the saga. In e-editions and now also an audio book.

Second in the Thunder Rise trilogy. Proceeds will benefit patients at Zambarano Hospital, in memory of my dear friend Frank Beazley.

The final book in the trilogy. A Kindle exclusive.

Dystopia, Apocalypse and more, available on multiple platforms.

And thanks to my good friends at Crossroad Press, Asylum and Summer Place are now in print and Thunder Rise is also an audio book. Details on all editions of the three books are at my books page -- along with details about Since The Sky Blew Off, the first volume, of a planned three, of my collected horror/mystery/sci-fi stories, some previously published, some now for the first time. (Read The Beach That Summer, from Vapors, the upcoming Volume 2.)

The beginning of the saga. In e-editions and now also an audio book.

Second in the Thunder Rise trilogy. Proceeds will benefit patients at Zambarano Hospital, in memory of my dear friend Frank Beazley.

The final book in the trilogy. A Kindle exclusive.

Dystopia, Apocalypse and more, available on multiple platforms.

Published on May 02, 2013 03:00

The Beach That Summer

THE BEACH THAT

SUMMER

copyright 2013 www.gwaynemiller.com

(From Vapors, the upcoming v. 2 of my collected short stories, companion to the Thunder Rise trilogy)

That summer,

Sand Hill was overrun by crazies. Try as you might, you couldn't get away from

them -- not at the beach, not in the bars, not even in your own backyard.

I don't mean the

summer people, the Applebaums and Lodges, the Bloomfields and Morgans. They

came that summer, as always, but they stayed even more to themselves inside

their Victorians and Capes. I don't know how many installed burglar alarms or

hired guards or took up arms, but I guarantee you there were a lot.

No, they were a

new breed, strangers to oldtime islanders like me. Out-of-towners, drawn by the

big-city papers and the checkout-counter tabloids and that big story on network

news the day before the Fourth of July. Just for fun, I stood on the bridge one

morning and checked license plates. It's a two-lane job, and both those lanes

were busy the hour I was there. Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire,

Connecticut, a few New Yorks, a couple of Ohios, even a California -- that's

what I saw. I don't claim every one of them was drawn by what was going on, but

I'd bet you a shore dinner most were.

We had gorgeous

weather that summer, absolutely picture- postcard perfect the whole way

through, and that didn't help, either. Come Labor Day, an islander -- a sailor

whose business it is to know such things -- counted the rainy days and came up

with a total of five. Even the thunderstorms stayed away that summer.

Of course, the

crazies would've come anyway, fair weather or foul. I knew that. Most every

islander knew that. The authorities knew it, too, and the frustration of it

nearly drove them mad.

See, there was a

crackle in the air that summer on Sand Hill. A tension you couldn't hide from.

A tension that was strongest out on West Shore, where all of them were found.

*****

Paula Hempson

was first. I knew Paula -- about as well as anyone else, I guess, and that was

none too well at all.

She was a loner

-- a seamstress by trade but a drinker by profession, an overweight woman about

my age, 47, who lived with a couple of strays in a trailer out by the landfill.

Once in a blue moon you'd see her at Jake's Cafe, swilling beers alone at the

end of the bar, clothes unkempt and hair dirty, looking for all the world like

somebody who'd just poisoned her overbearing mother.

June 8, they

found her body -- what was left of it -- on a tidal flat off West Shore.

West Shore is

the island's scenic gem, three miles of beautiful white sand that belongs in

Florida or South Carolina or Hawaii, not southern New England. Three miles of

clean, virgin beach, not a hot dog stand or a windsurfing shop in sight. State

land, the only reason it's stayed undeveloped for so long.

West Shore --

since I was old enough to walk, I must've been there a million times, swimming,

fishing, clamming, falling in love with it again and again and again. I had my

first woman on West Shore. She was 36 and I was 17 and she took me there in her

car, a '51 Plymouth, and we shared wine and a blanket as we watched

Fourth-of-July fireworks. She disappeared years ago -- there's still talk it

was murder -- but I never forgot her, or that night.

I say they found Hempson's body, but it

actually was a 10-year-old girl. She was the daughter of Jake Cabot, the

selectman, and she was out there clamming when she stumbled onto it. As Jake

later told it, first she screamed, then got sick, then finally ran like the

devil himself was after her -- ran straight to the police station, a full mile

away.

Sgt. Ross Miller

was on duty that afternoon, and he knew Jake's little girl well enough to know

she wasn't bull-crapping about what she'd seen off West Shore. After calling

her dad, he got in his cruiser and headed down. On the way, he called Rescue

One.

I was at home,

camped out in front of the TV, when I heard the chatter over my Bearcat. In

half a minute, the fire horn downtown was blaring. I heard a second siren --

somebody'd decided to send an engine, too. I got in my Jeep and headed after

it.

When I got to

West Shore, half the department was already there (but not a single other

soul), sloshing knee-deep through the incoming tide on their way out to the

flat. I headed out with them, curious, but also strangely edgy and...

...excited isn't quite the word.

Nobody spoke,

but everybody felt it, what I was feeling. There wasn't going to be any rescue

today, we saw that right off, only a cleanup we'd be seeing in our dreams for

months to come. I don't blame that girl for getting sick. I damn near did

myself, and I've spent my adult life in fishing boats -- not the pleasantest of

places to be, especially a week after a full catch.

Paula was face

down, three-quarters submerged, bobbing gently as the waves licked over her.

With his billy stick as a prod, Sarge Miller turned her over.

That's when we

saw -- total evisceration. I think we all gasped. I think we all said a silent

prayer. We stood, not wanting to look, unable to turn away, wishing that the

sea would swallow the body up again so we could go home and forget we'd ever

seen it. Ten seconds, half a minute, a minute -- who was counting? The time

went by and we were still there, lost in our thoughts, the sea lapping against

our boots, a few gulls skimming low over the water, the sun pinkening as it

started down toward evening.

Finally, Sarge

Miller said in an unsteady voice, ``OK, boys, we got work to do. Tide's gonna

beat us, we don't get a move on.''

Sarge's order

was like a rock through glass. In no time, we had the body on the sand, safe

from high tide.

Buzz Aldrich

went across the sand to his four-wheel-drive to have the station call the ME's

office. The rest of us moved off some and lit up cigarettes.

*****

Sarge Miller was

the first to use the word ``shark.''

It was, as

events would later prove, a most unfortunate choice of word. It was a word that

would come back to sorely haunt him, and the island, and the state -- a word

that would be misinterpreted and misquoted and misused so badly that for part

of that summer, at least, it would seem like our lives were being scripted in

Hollywood, and we were actors in a real-life Jaws. It was wrong, as we would

find out -- about as wrong as you can get -- but then, the beginning of that

summer, that's what we believed.

Now, it would be

one thing if Sarge made his assessment over beers at Jake's, but he didn't. He

made it in to a reporter.

His name was

Storin, and he worked for one of the Boston papers. Storin was on the island

that day getting notes on Sand Hill's summer set when the siren blew and we

tore-assed down to West Shore, him not far behind. I remember thinking that Sarge

was going to tell him to take a flying leap when he strolled up, dressed in tan

slacks and a button-down shirt, Mr. City Slicker himself. Only he didn't. He

didn't say boo when Storin pushed straight past us, barely a word of hello, to

get a better look.

``Mauled,''

Storin said simply when he strolled back. Mauled -- it was the word we'd been

wracking our brains for.

``You got it, my

friend,'' Sarge said.

``Homicide?''

Storin asked casually as he pulled his notebook out of his back pocket.

I saw that notebook

and cringed, and I figured by that point alarm bells should have been going off

inside Sarge's head. They weren't. Maybe he was shocked. Maybe he didn't

understand the press. Maybe he'd been cozying up to Jack Daniel again.

Whatever the

maybe, he was just as cordial as can be.

``No person

could have done that,'' he said, as Storin scribbled crazily. ``Had to be

something from out there,'' he finished, sweeping the expanse of the sea with

his right arm.

``You mean

shark,'' Storin said, and that's when he pulled the tape recorder out of his

pocket.

You knew,

listening, that the guy had Jaws dancing in his head. You knew he couldn't wait

to get back to Boston to write it. You knew, if you knew anything at all, that

his story would draw the media to Sand Hill like gulls to a homebound trawler.

Even then, Sarge

didn't come to his senses. ``That's right,'' he said, spitting into the sand.

``I mean shark.''

*****

The Herald put

Storin's story on Page Three. It mentioned Jaws, quoted Sarge Miller

extensively, and included a list of documented shark attacks around the world

the last 50 years.

Beyond that --

well, what more could it have said?

The ME wasn't

talking and there were no grieving relatives to be quoted. I understand the

police phone rang off the hook the next day, and I understand that Sarge Miller

got reamed but good by Chief, but until Marjorie Peters, that Herald story was

it.

*****

Mark Peters was

second.

It was after him

that the lid blew off Sand Hill. It was after him that the crazies took over

the beach.

I wasn't on the

island the day he washed up, June 30, but Chief gave me a description over

Rolling Rocks at Jake's Cafe. Thank God, no kid found him. That kind of thing

could have scarred another kid for life -- just ask Jake. No, this time, a guy

from state Environmental Affairs had the honors. Spotted him through binoculars

on a law-enforcement patrol of West Shore, about a half mile north of where we

fished Hempson out of the surf.

Spotted him and

then threw his lunch, just like Jake's girl.

Like Hempson, Peters

was a shadow figure, a ghost. He wasn't poor like Hempson -- he had a nice

waterfront cottage, what was rumored to be a nice fat nest egg in a First State

trust. The other particulars were identical: Mark Peters was lonely and alone.

``Looked like

Hemspon,'' Chief said, ``exactly like Hempson,'' and he knew he didn't need to

say any more. I killed my Rolling Rock and ordered a double Cutty. Chief

followed suit. We sat together on our stools, silent as the mahogany under our

elbows.

Silent, that is,

until another double Cutty was history. That's when Chief whispered: ``It ain't

no shark.''

I didn't catch

his drift, not immediately.

``Somebody

wanted it to look that way,'' he continued, ``faked it like a shark. Mark Peters

was murdered.''

``You're

kidding.''

``I wish I was.

Lord, how I wish I was.''

``How can you be

sure?''

``We got a note.

Hand-written. Arrived at the station an hour after we fished him out. Certain

details in that note are consistent with certain preliminary findings from the

ME. And there was a drawing. Very precise. Very gory. Made me sick.''

``Holy smokes.''

``There's

more,'' Chief said on our third Cutty. ``Hempson wasn't any shark, either.''

``You can't be

serious.''

``I am. ME's

report came back.''

``And--''

``--and it seems

we got a nut on the loose.''

*****

The papers and

web went ape over Mark Peters. TV joined right in. By Friday night, the island

was crawling with reporters and photographers and bloggers -- I mean crawling,

the way an army of ants'll crawl over something sweet that's dripped down your

kitchen counter.

Who cared if

Chief was urging restraint, was insisting nothing was definitive, that no

sharks had ever been sighted within miles of Sand Hill? Who cared if the ME

took pains to explain that the natural action of seawater and bacteria have a

certain disgusting but distinctly deteriorative effect on human flesh?

Who cared?

This was the

rarest of opportunities, probably it would never come again, a summertime Jaws

in real life and all there within a couple hours driving time of the big East

Coast cities.

*****

If you wanted to

put a date on when we first felt the crackle in the air that summer, first really felt it, it's fair to say it was

at 6:39 p.m. on Sunday, July 3.

I knew it was

coming, and I guess most other islanders did, too. Hadn't we seen the big-shot

film crew sticking cameras in shoppers' faces on their way out of Franny's

Market? Hadn't we seen three shiny new Lincolns parked outside Clipper Inn?

Hadn't they rented Bill Weather's 44-foot Chris Craft, mooring it for an entire

afternoon off West Shore? Hadn't there been a helicopter?

We knew the

report was coming, but still the force of it was overwhelming -- introduced, as

it was, by Brian Williams.

I remember that

report like it just ended. It opened with an aerial shot of the island, the

water shimmering like diamonds in a jewelry-store display case, and then it cut

directly to West Shore, where a pretty-boy type was standing alone with a

microphone, the wind tousling his hair, this terribly somber look on his face.

``Fear has

struck this quintessential New England resort,'' he said, or something very

close to that, ``fear that man's greatest natural enemy is prowling these

beautiful waters. Fear that a great white shark which has apparently claimed

two victims will go for more before the long hot summer is through...''

The day after

that broadcast. That's when it got crazy to walk the beach.

Crazy, because

for a spell, it didn't seem the off-islanders were ever going to leave. Crazy,

because everyone knew why everyone else was there -- to wait, to watch, to hope

in the sickest fashion that they would be the ones there when... when it

happened again.

And nobody

doubted it would.

All day, they

were there, and well into the evening. They parked their Broncos and

Winnebagoes and played Frisbee and set up Volleyball nets and lit charcoal

fires on Hibachi grilles and the younger and more foolish ones, the

gold-chained men with their painted-toenail women, dared each other to wade in.

From the dunes, you could see them -- shadowy characters in a bad dream.

Few islanders

walked deep down the beach from then on that summer, but I did.

I did because

I'd always done it, always been in love with the smells and sounds and sunsets

you get there, only there, on West Shore. I did because I'd been going there

since I was a kid. I did because stress and tension magically dissipated there,

carried away on the warm summer breeze. If I'd been a poet, I think I would

have camped out forever on West Shore. The poems I would have written would

have been soft and billowy, like clouds, not angry and irrational and

unforgiving, like the world around us.

Once a day, I

walked West Shore, end to end, three miles in all. Once a day, invariably in

early evening, when the sun was dropping down to kiss the sea and the breeze

was stiff enough to keep the black flies grounded.

I carried a .38

that summer, and sometimes, the razor-sharp stiletto I picked up in New York

years ago. I carried them -- and carrying them gave me security. Few islanders

walked West Shore that summer, but when they did, they carried weapons, too.

After Billie

Robards, it would have been crazy not to.

*****

Billie put an

end to all the shark talk. There were two good reasons for that. One was where

they found her: in the West Shore dunes, 100 yards, easy, from mean high tide.

The other was

the letter that was mailed to the editorial offices of the Providence Journal.

It arrived July

14, hours before they found her, decapitated and limbless, so there was no

question it was authentic. They never published the full text of that letter,

which had a Providence postmark, but word got around the island pretty quickly

about what was in it: Billie's name, a drawing, a plea to ``stop me, I can't

control myself,'' all of it in black felt pen.

``He's sick,

really sick,'' Chief said to me, and I could see the desperation and

frustration and the something I hesitated to call fear in his tired blue eyes.

I knew Billie.

Knew her

personally, and well. She was married to Will Robards, the skipper and owner of

the Liza D., a Sand Hill trawler I'd crewed on for years. Will's boat had kept

me in dough times when times were rotten, and for that, I was eternally

grateful. His wife was a peach, a 40-year-old brown-eyed peach with a wonderful

laugh. I used to run into her in the market, at the gas station, wherever, and

we always exchanged pleasantries. For years, she'd made it a point to stop by

the house Christmas Eve to drop off her home-baked goodies. ``Bachelor's

Special,'' she'd say, and we always laughed heartily as we toasted our mutual

good health.

After Billie's

autopsy, they quietly exhumed Paula Hempson and Mark Peters, allowing the pathologists

to conclude that one person almost certainly was responsible for all three

deaths. It answered the question the papers had forgotten to ask: Just what had

Hempson and Peters been doing swimming off West Shore, anyway?

If they loved

Shark, they went berserk for Maniac on the Loose.

They'd smelled

blood, real honest-to-God fresh-flowing blood, blood that seemed certain to

flow again if everybody only waited a spell, and now there was no stopping

them. Somebody joked that every fourth person on Narragansett Avenue was a

reporter from there on out, but I didn't laugh. One knocked on my door, and I

live half a mile from the main drag. Forget downtown, Jake's Cafe, the docks.

Things were at a fever pitch, nobody seemed sane anymore, everybody had a theory

and a suspect and...

...and that

crackle was in the air.

I don't know how

else to describe it. I think back to that summer and I can hear it inside my

head, a loud, painful crackle, this terrible thing that prickles the hairs on

my neck.

``All that publicity

can only be encouraging him. Sons of Satan, every one of these reporters.''

If Chief said it

once that summer, he said it a hundred times, and he was right, he was right.

That was the bitch of it; everyone knew what the publicity was doing, but we were

powerless to stop it. A great country, America, isn't it? You could see this

sick puppy, living alone, catching the evening news and getting all worked up

about his latest victim -- a steam-filled pressure cooker set to blow again,

and no one there to turn the burners off.

Off-islanders

still walked West Shore -- for the most part, only in the bold light of day

now. And they did it in tighter and larger clusters than before -- the foolish

illusion of strength in numbers, I imagine. But mostly, after Billie Robards,

they stuck to the docks and the restaurants and Jake's, endlessly, morbidy

fascinated with the Shore Stalker, as they came to call him.

I kept walking

West Shore, my hand a little tighter on my .38, my eyes straining a little

harder, every passerby a suspect. I kept walking because I was determined the

Stalker couldn't keep me from the place I loved so. I kept walking because I

always had.

*****

Victims four and

five were found Aug. 14, three days after a letter arrived on Chief's desk. The

State Police sent it off to the lab for analysis, but it didn't take a

criminologist to see that the same hand had penned both letters.

I got a

photocopy of that letter from Sarge Miller. Photocopies were worth their weight

in gold that summer. ``Stop me,'' the letter said. ``Please, I beg you, stop

me.''

Nothing else.

I forget their

names -- they were off-islanders, a honeymooning couple in their 20s from

Pennsylvania. Their car was found in the West Shore lot, and there was some

dispute over whether they had known what was happening on the beach that summer

or had wandered there unsuspectingly through impossibly bad luck.

Even after them,

the curious came, but they came in much smaller numbers. By late afternoon,

West Shore would be deserted, whatever off-islanders there had been having

retreated to the safety of the motels and bars. After Aug. 14, the only people

I met on my evening walks were cops and a couple of old salts who'll be out

there surf casting the day they drop the Big One.

We islanders

drew tightly together then -- for solace, more than protection. I bet there

have never been more floodlights sold than that summer, more German Shepherds

bought, more shotguns oiled and loaded, mine included.

For all that, it

was an uneasy camaraderie.

Media or no

media, one fact could not be exaggerated: there was a cold-blooded killer out

there, and who's to say he wasn't your Uncle Joe or your Cousin Henry? Who's to

say he wasn't sitting right there with you in Jake's, or standing with you at

the checkout counter, or behind the wheel of the car in front of you coming

over the bridge? Who's to say it wasn't Jake, or Will Robards, or Chief, or

Sgt. Ross? Stranger things have happened.

Truth was, we

were an island scared to death.

Up in the

capitol, there was a sense of urgency you usually see only after hurricanes or

blizzards. The governor went on TV to announce creation of the Sand Hill Task

Force, what he described as the state's largest, most ambitious crime hunt

ever. State Police, Sand Hill Police, the National Guard -- they were all in on

it.

The Shore

Stalker was going to be caught, yes he was.

Except he

wasn't.

One week, two

weeks, three weeks went by, Labor Day was just around the corner, and there

hadn't been an arrest. Thank the Lord, the Stalker was quiet, but the

authorities were no closer to finding him than they'd been all summer.

They tried

everything -- roadblocks, unmarked cars, armed men in the dunes. They searched

cars, boats, crunched names through national data bases, run up the biggest

overtime bill in the history of Rhode Island law enforcement. Eventually, the

American Civil Liberties Union began to squawk. It was that big.

That

unsuccessful.

``It's the

goddamndest thing I ever saw,'' Chief told me on Sept. 3, two days before the

Board Of Selectmen fired him. ``It's almost like this guy doesn't really

exist.''

He wasn't the

first to think that. I'd thought it myself.

*****

Labor Day came

and went, and the Stalker didn't strike, and then it was Columbus Day, and

Christmas, and we were into the New Year. The papers and TV moved on to other

places, other tragedies.

Still, he wasn't

caught. There wasn't even an arrest.

So here it is,

Friday of Fourth of July weekend, and the traffic into Sand Hill is noticeably

heavier, and every islander is remembering last summer and feeling strangely

skittish and...

...and that

crackle in the air is back, louder than before.

I close my eyes

and I can hear it, feel it, excruciatingly painful, like the first stab of a

migraine at the back of your skull.

They won't admit

it, of course, but the authorities are convinced that there's a

better-than-even chance the Stalker will be tempted this weekend. Something

about the pattern of last year's killings, they say, something about the

renewed publicity, something the handwriting experts say they can see in his

letters.

Another one, you

see, was received by the new Chief today.

So they've

closed off West Shore for the weekend, and they're turning back cars headed