G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 19

March 29, 2017

"Are you feeling lucky today?"

I had a tooth extracted today. Doesn’t matter why; suffice it to say that Miller teeth have been less than Hollywood-perfect since cave days. It was way back there in my mouth and I didn’t need it, anyway.

My dentist is a fine practitioner, but when his first question to me was “Are you feeling lucky today?” my heart sank.

I thought: Sure, playing Marathon Man ALWAYS makes me feel lucky, but of course I just said, “Yes I am. Why?”

Well, he said, HE needed luck to complete a swift procedure, given the particulars, which I totally did not understand and did not want to.

So that was the good luck. What was the bad, I asked?

He launched into something about how bad luck would force him into digging around down there if the damn thing cracked, or one root came out but the other didn’t, or if I was some genetic freak and the roots of this particular tooth went through my jaw into my spinal cord and up into my brain.

OK, I imagined that.

Still, “digging around down there” -- these are NOT words you ever want to hear in association with your mouth. So my mind went spinning off to some other universe where people do not need teeth to enjoy a good meal.

When it returned, my dentist asked me to inch back on the chair farther than seemed possible without falling off. That was so my head could be adjusted downward at such an angle that I could almost see the floor.

Access, I thought, correctly. My dentist did the usual turn this way and that thing repeatedly, until he found what I assumed was a suitable approach.

Then he said, and I quote: “Hmm, no leverage.”

Leverage is another word you never want to hear associated with your mouth, especially when the man saying it is holding a Cow Horn dental extractor in his hand. I believe leverage was the last word Dustin Hoffman heard before Laurence Olivier got down to it.

And, yes, Cow Horn is the technical name for the specific pliers used for this procedure. I know, because I managed to ask. I’m insatiably curious that way. I wish I weren’t.

Of course, I also had to ask how it got that name – you can see I was stalling big-time here – and my dentist said, well, it looks like a cow’s horn. And it did, a tiny one, but then my mind, which had returned from that universe where they do not have such things, thought of cows, which brought me to bulls, which have man-killing horns, as Spanish matadors can attest.

Feeling chatty now, I remarked that the Cow Horn must have an ancient lineage, given that for centuries, all dentists really could do was pull – ahem, extract – teeth. My dentist was not interested in history at that moment. He had the Cow Horn in his hand, and no leverage.

Stalling only works so long, by the way, in a dentist chair. My guy locked onto my tooth with his Cow Horn and began to wiggle back and forth, slowly at first. That’s when I began to wish he HAD found leverage.

The Cow HornHe asked if I could feel it. Dumb question, I thought.

The Cow HornHe asked if I could feel it. Dumb question, I thought.

Which is when I wished I had opted for sedation, not Novocain. My thinking had been that I wouldn’t feel groggy the rest of the day without sedation and I could get some actual work done, not write a silly essay. Stupid thinking, Wayne.

“Are YOU feeling lucky today?” my dentist then asked his assistant.

I am not making this up.

The assistant didn’t answer. I interpreted this to mean she was NOT feeling lucky, and my mind completed another round trip to that universe, which I think I will name the Happy Place. Maybe they only eat plain yogurt and cream cheese there, but I’m OK with that.

Back and forth with the Cow Horn, the dentist went. I was booking another trip to The Happy Place when he said, AGAIN, “luck.” Actually, he exclaimed: "Luck!"

And he’d had it. Really. The tooth was out. Total time elapsed? Maybe five minutes.

As I said, I have a fine dentist. He’s of Irish descent, and surely has a four-leaf clover.

Also, an Irish sense of humor.

My dentist is a fine practitioner, but when his first question to me was “Are you feeling lucky today?” my heart sank.

I thought: Sure, playing Marathon Man ALWAYS makes me feel lucky, but of course I just said, “Yes I am. Why?”

Well, he said, HE needed luck to complete a swift procedure, given the particulars, which I totally did not understand and did not want to.

So that was the good luck. What was the bad, I asked?

He launched into something about how bad luck would force him into digging around down there if the damn thing cracked, or one root came out but the other didn’t, or if I was some genetic freak and the roots of this particular tooth went through my jaw into my spinal cord and up into my brain.

OK, I imagined that.

Still, “digging around down there” -- these are NOT words you ever want to hear in association with your mouth. So my mind went spinning off to some other universe where people do not need teeth to enjoy a good meal.

When it returned, my dentist asked me to inch back on the chair farther than seemed possible without falling off. That was so my head could be adjusted downward at such an angle that I could almost see the floor.

Access, I thought, correctly. My dentist did the usual turn this way and that thing repeatedly, until he found what I assumed was a suitable approach.

Then he said, and I quote: “Hmm, no leverage.”

Leverage is another word you never want to hear associated with your mouth, especially when the man saying it is holding a Cow Horn dental extractor in his hand. I believe leverage was the last word Dustin Hoffman heard before Laurence Olivier got down to it.

And, yes, Cow Horn is the technical name for the specific pliers used for this procedure. I know, because I managed to ask. I’m insatiably curious that way. I wish I weren’t.

Of course, I also had to ask how it got that name – you can see I was stalling big-time here – and my dentist said, well, it looks like a cow’s horn. And it did, a tiny one, but then my mind, which had returned from that universe where they do not have such things, thought of cows, which brought me to bulls, which have man-killing horns, as Spanish matadors can attest.

Feeling chatty now, I remarked that the Cow Horn must have an ancient lineage, given that for centuries, all dentists really could do was pull – ahem, extract – teeth. My dentist was not interested in history at that moment. He had the Cow Horn in his hand, and no leverage.

Stalling only works so long, by the way, in a dentist chair. My guy locked onto my tooth with his Cow Horn and began to wiggle back and forth, slowly at first. That’s when I began to wish he HAD found leverage.

The Cow HornHe asked if I could feel it. Dumb question, I thought.

The Cow HornHe asked if I could feel it. Dumb question, I thought.Which is when I wished I had opted for sedation, not Novocain. My thinking had been that I wouldn’t feel groggy the rest of the day without sedation and I could get some actual work done, not write a silly essay. Stupid thinking, Wayne.

“Are YOU feeling lucky today?” my dentist then asked his assistant.

I am not making this up.

The assistant didn’t answer. I interpreted this to mean she was NOT feeling lucky, and my mind completed another round trip to that universe, which I think I will name the Happy Place. Maybe they only eat plain yogurt and cream cheese there, but I’m OK with that.

Back and forth with the Cow Horn, the dentist went. I was booking another trip to The Happy Place when he said, AGAIN, “luck.” Actually, he exclaimed: "Luck!"

And he’d had it. Really. The tooth was out. Total time elapsed? Maybe five minutes.

As I said, I have a fine dentist. He’s of Irish descent, and surely has a four-leaf clover.

Also, an Irish sense of humor.

Published on March 29, 2017 14:22

December 13, 2016

My Dad and Airplanes

Author's Note: I wrote this four years ago, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of my father's death. Like his memory, it has withstood the test of time. I have slightly updated it for today, December 13, 2016, the 14th anniversary of his funeral. Read the original here.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 14 years ago Sunday.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 14th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 14 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died last year. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 14 years ago Sunday.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 14th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 14 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died last year. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Published on December 13, 2016 01:42

November 10, 2016

Humbled and honored, twice

On Wednesday evening, November 9, Yolanda and I attended the annual fundraiser for Butler Hospital, the world-renown treatment, research and teaching hospital (The Warrant Alpert Medical School at Brown University) in Providence, Rhode Island. I was there to receive a community-service award for my decades of writing and filmmaking about mental health and neurological disorders. For Yolanda, a mental-health therapist who once studied and worked at Butler, it was a chance to see many old friends. For me, a high and humbling honor. This was not a contest one enters, but an award that came my way out of the blue.

My remarks below.

I, too, saw some friends – some I knew were would be there, some not. In the latter category were Cindy and John Duncan, farmers from Richmond, Rhode Island, who lost their teenaged daughter Cassie to suicide on Christmas Day 2005. Cindy found her.

“Her door was locked,” Cindy would recall. “I banged on the door. I didn’t hear anything. Then I smashed open the door. She was gone.”

From that terrible tragedy, the Duncans brought great good: a growing public crusade that includes the Rainbow Race, the yearly fundraiser they organize and host that benefits the Rhode Island chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“We have to take the dark cloud of stigma and fear away from mental illness and replace it with the rainbow of hope!” the Duncans declared in announcing the 2016 race.

Wanting to help such a good cause, I spent part of a day in May with the family and wrote a story and shot a video for The Providence Journal, which you can read here.

And I left a favorite jacket at the Duncans’ house. When I later got back to them, they said they would keep it at their farm stand for the next time I happened to be in the area. It was closed the one time I went by.

So there they were, surprise (to me) guests at Wednesday’s Butler fundraiser. It was wonderful to see them, introduce Yolanda to them, and just be in their company. At one point, Cindy said that having learned I would be there, she had brought my jacket. I could hardly believe it. How thoughtful! Cindy pointed to a shopping bag under the table. I looked, but did not open.

The Duncans had left by the time I did look. More than a jacket was inside:

Inside was a beautiful print of a flower. Cassie had made it. Among many other wonderful things in her short life, she was an artist.

“Hi, Wayne,” read Cindy’s note attached to her daughter’s art. “This print is one of Cassie’s and I would like you to have it. Thank you for all your help, ♥ Cindy and John.”

I nearly cried. Actually, I did cry.

I will frame Cassie’s flower, place it in my study, and treasure it always, a reminder of how precious life is -- and how, especially at a time when so many bad things happen, there are inspiring and loving people who selflessly work, one day at a time, in their neighborhood, town or state, to make the world a better place.

Thank you, Cindy and John, and thank you, Cassie.

Community service award, Cassie Duncan's flower.

Community service award, Cassie Duncan's flower.

My remarks after receiving the Lila M. Sapinsley Community Service Award:

Thank you, Dr. Price, and my thanks to the Butler Hospital Foundation. I am humbled and honored to receive this award. I knew Lila Sapinsley and always admired her many causes that benefitted so many people. Her heart was big. I’d like to think she would approve of my name now being associated with hers.

Let me also thank The Providence Journal, which has supported my work for so long and given me the time and resources needed to bring it to fruition. Our publisher, Janet Hasson, is here tonight – thank you, Janet, for your commitment.

Let me also thank someone who is not here: former editor Joel Rawson, who more than 30 years ago assigned me to cover the state-prison and child-welfare systems, and what was then known as the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals. That assignment began my long career in social-justice journalism, which remains my passion.

Thanks to my wife Yolanda, a mental-health therapist who imparts her greater wisdoms to me about the field that connects us.

Thanks, too, to the many other clinicians, educators, scientists and others involved in the treatment and research of mental illness and neurological disorders who have shared so generously of their time and expertise over the decades. Some are here tonight. To all of you, my heartfelt appreciation.

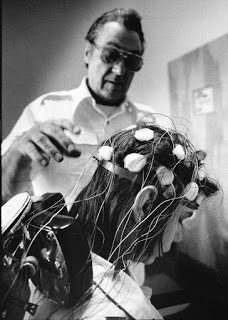

When I began writing about mental health in the 1980s, stigma was one of society’s worst cruelties – a legacy of the days when the mentally ill were shackled in cellars or burned at the stake, a savagery that Butler Hospital replaced with humane care when it was founded in 1844. Stigma remains an obstacle to understanding, acceptance and care – there is still work to be done -- but today, more people view mental illnesses as they do the so-called physical ones, where recovery and fulfilled lives are possible. Which is as it should be.

So I especially want to thank the countless individuals living with mental illness, along with their family members and friends, who have allowed me to tell their stories. Without them, my writing and films would be little more than facts and statistics, important though those are. What power stories have.

These many good people, who courageously let me use their real names and images and publish the most intimate details of their lives, have done more to strike a blow against stigma than anything else I can imagine. I salute and admire them. One by one, they are helping to better the world.

My remarks below.

I, too, saw some friends – some I knew were would be there, some not. In the latter category were Cindy and John Duncan, farmers from Richmond, Rhode Island, who lost their teenaged daughter Cassie to suicide on Christmas Day 2005. Cindy found her.

“Her door was locked,” Cindy would recall. “I banged on the door. I didn’t hear anything. Then I smashed open the door. She was gone.”

From that terrible tragedy, the Duncans brought great good: a growing public crusade that includes the Rainbow Race, the yearly fundraiser they organize and host that benefits the Rhode Island chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“We have to take the dark cloud of stigma and fear away from mental illness and replace it with the rainbow of hope!” the Duncans declared in announcing the 2016 race.

Wanting to help such a good cause, I spent part of a day in May with the family and wrote a story and shot a video for The Providence Journal, which you can read here.

And I left a favorite jacket at the Duncans’ house. When I later got back to them, they said they would keep it at their farm stand for the next time I happened to be in the area. It was closed the one time I went by.

So there they were, surprise (to me) guests at Wednesday’s Butler fundraiser. It was wonderful to see them, introduce Yolanda to them, and just be in their company. At one point, Cindy said that having learned I would be there, she had brought my jacket. I could hardly believe it. How thoughtful! Cindy pointed to a shopping bag under the table. I looked, but did not open.

The Duncans had left by the time I did look. More than a jacket was inside:

Inside was a beautiful print of a flower. Cassie had made it. Among many other wonderful things in her short life, she was an artist.

“Hi, Wayne,” read Cindy’s note attached to her daughter’s art. “This print is one of Cassie’s and I would like you to have it. Thank you for all your help, ♥ Cindy and John.”

I nearly cried. Actually, I did cry.

I will frame Cassie’s flower, place it in my study, and treasure it always, a reminder of how precious life is -- and how, especially at a time when so many bad things happen, there are inspiring and loving people who selflessly work, one day at a time, in their neighborhood, town or state, to make the world a better place.

Thank you, Cindy and John, and thank you, Cassie.

Community service award, Cassie Duncan's flower.

Community service award, Cassie Duncan's flower.My remarks after receiving the Lila M. Sapinsley Community Service Award:

Thank you, Dr. Price, and my thanks to the Butler Hospital Foundation. I am humbled and honored to receive this award. I knew Lila Sapinsley and always admired her many causes that benefitted so many people. Her heart was big. I’d like to think she would approve of my name now being associated with hers.

Let me also thank The Providence Journal, which has supported my work for so long and given me the time and resources needed to bring it to fruition. Our publisher, Janet Hasson, is here tonight – thank you, Janet, for your commitment.

Let me also thank someone who is not here: former editor Joel Rawson, who more than 30 years ago assigned me to cover the state-prison and child-welfare systems, and what was then known as the Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals. That assignment began my long career in social-justice journalism, which remains my passion.

Thanks to my wife Yolanda, a mental-health therapist who imparts her greater wisdoms to me about the field that connects us.

Thanks, too, to the many other clinicians, educators, scientists and others involved in the treatment and research of mental illness and neurological disorders who have shared so generously of their time and expertise over the decades. Some are here tonight. To all of you, my heartfelt appreciation.

When I began writing about mental health in the 1980s, stigma was one of society’s worst cruelties – a legacy of the days when the mentally ill were shackled in cellars or burned at the stake, a savagery that Butler Hospital replaced with humane care when it was founded in 1844. Stigma remains an obstacle to understanding, acceptance and care – there is still work to be done -- but today, more people view mental illnesses as they do the so-called physical ones, where recovery and fulfilled lives are possible. Which is as it should be.

So I especially want to thank the countless individuals living with mental illness, along with their family members and friends, who have allowed me to tell their stories. Without them, my writing and films would be little more than facts and statistics, important though those are. What power stories have.

These many good people, who courageously let me use their real names and images and publish the most intimate details of their lives, have done more to strike a blow against stigma than anything else I can imagine. I salute and admire them. One by one, they are helping to better the world.

Published on November 10, 2016 02:51

October 17, 2016

Historical injustices against Native Americans continue into today

As part of The Providence Journal's

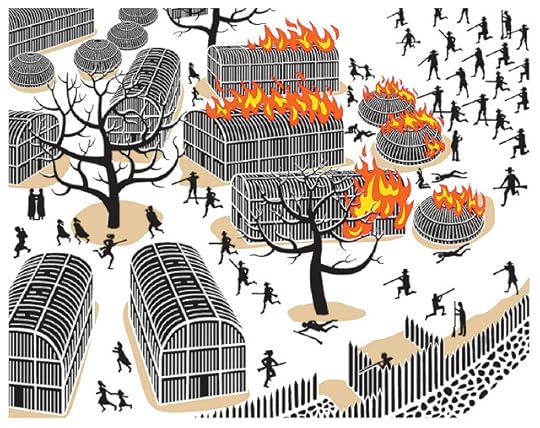

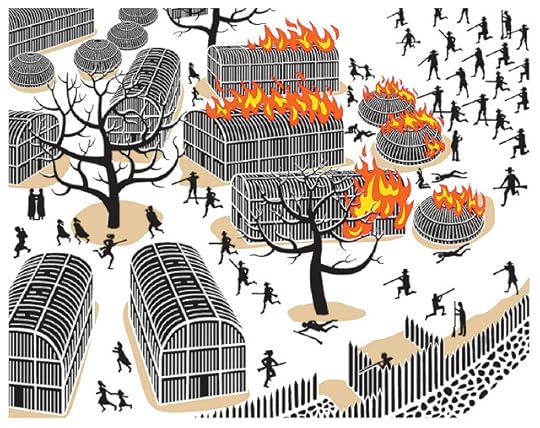

The massacre, on Dec. 19, 1675, is far and away the bloodiest event in Rhode Island history. It still reverberates today, nearly three and a half centuries later.

Publication Date: October 26, 2015 Page: 1 Section: A

Providence Journal illustration by Tom Murphy.

Providence Journal illustration by Tom Murphy.

A gentle rain falls on Paulla Dove Jennings as she stands by a monument deep in the South Kingstown woods. She has come here on this autumn morning to tell the story of the Great Swamp Massacre, in which white colonialists slaughtered and burned alive hundreds of her Narragansett and Niantic ancestors. Many were elders, women and children.

The massacre, on Dec. 19, 1675, was far and away the bloodiest event in Rhode Island history. Its repercussions are still felt today, nearly three and a half centuries later.

The backdrop was King Philip’s War, during which English settlers and some of New England’s Native American tribes fought, with devastating consequences for all. At the start, Jennings’ ancestors declared their neutrality, but they feared a white offensive. As winter approached that first year, many hundreds of them sought sanctuary on a remote island, farther into the wilderness from today’s monument.

They were living in long houses — large timber lodges that provided shelter for dozens of extended families.

“There was warmth,” says Jennings, 75, an educator, author and nationally acclaimed storyteller. “There was food stored. You shared. It was all right there so they could get through the winter.”

Extreme cold that December of 1675 had frozen the swamp solid, providing easy access for the colonialists, who suspected that the Narragansett and Niantic people were providing sanctuary to members of the Wampanoag tribe, the whites’ principal adversaries. On the afternoon of Dec. 19, they stormed the island with guns, blades and fire. In her telling, Jennings assumes the persona of a Native grandmother who was there with a young child.

“You could feel the pain. You could peek out and look and you could see people on fire, people being slaughtered, people being shot. Children, falling dead. And I’m thinking of how to get away, how do we survive, with these flames and these guns going off and people with daggers and swords and spears — and they’re trying to kill us, and you’re seeing the blood and you’re hearing the cries and you’re hearing the moans.

“And after all of this, the shock of it. How can man’s inhumanity to man be so strong? How they could be so hateful? When it was our land, our people.”

The colonialists captured a number of survivors and later sold some into slavery. Some of those who escaped fled as far away as Wisconsin, while others retreated deeper into the woods and swamps of South County, into parts of what are now known as Charlestown, South Kingstown and Westerly.

Further tragedy awaited them and the other tribes that ultimately were defeated in King Philip’s War, which left many Native communities and white towns in ruin, including Providence, founded by Roger Williams, an early friend of the Narragansett. Diseases introduced by the English claimed many. Tribal lands were taken, until, by the late 1700s, Narragansett territory had been reduced to about 15,000 acres, a fraction of what had been theirs for thousands of years. The Founding Fathers disparaged them in the Declaration of Independence, writing this often-overlooked clause near its end, referring to King George III:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

“That always just astounds me,” Jennings says. “We didn’t come with the cannon. We didn’t come with the gun. We didn’t invade [settlers’] territory. And yet we’re vilified.”

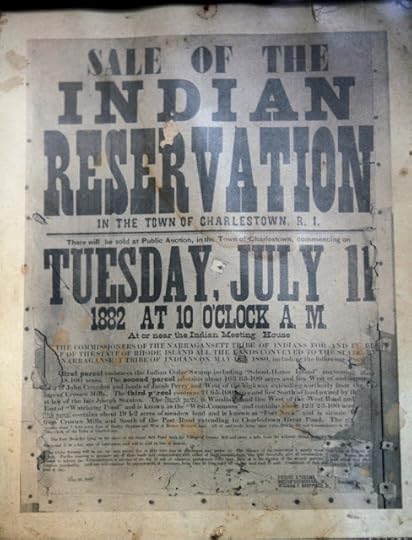

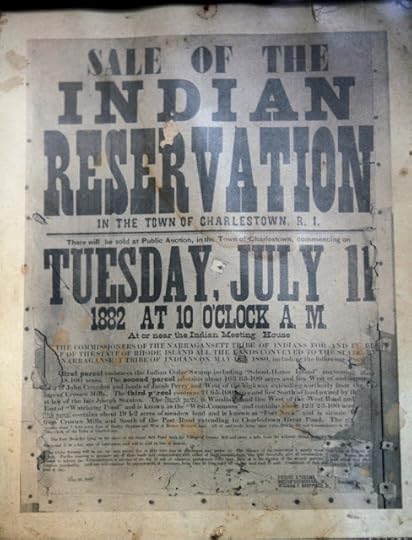

The Narragansett and Niantic struggled into the latter part of the 19th century — and then came another blow, one more injurious than words. In defiance of federal law, the Rhode Island General Assembly in 1880 “detribalized” the Narragansett, abolishing tribal authority and eventually selling all but two acres of the tribe’s land. In her Exeter home, Jennings keeps a copy of the poster that announced the first offering.

Sale of the Indian Reservation, it begins. There will be sold at public auction, in the town of Charlestown, commencing on Tuesday, July 11, 1882, at 10 o’clock a.m., at or near the Indian Meeting House … first parcel embraces the Indian Cedar Swamp, including ‘School House Island’…

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought the federal policy of “forced assimilation” of members of the Narragansett and other tribes across the United States. Government officials intended to essentially remake Indians into whites by forcibly remanding them to specialized boarding schools where their Native American culture was stripped away.

One of the most notorious was the United States Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, founded in 1879 by Army Capt. Richard Henry Pratt, who wrote that a Native American “is born a blank, like all the rest of us. Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of a civilization and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit.” His motto was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

Records at Exeter’s Tomaquag Museum, which preserves the culture and history of Rhode Island’s indigenous people, chronicle the fate of the Narragansett men who were sent to Carlisle.

“The entire purpose,” says museum head Lorén Spears, who is Jennings’ niece, “was to take you far away from home, keep you there for years on end and strip of you everything you know — your language, your culture, your community, your family. Change your clothes, change your hair, change your religion — literally strip you of everything you know as being Narragansett or any Native American nation group.”

In 1978, after a land-claim lawsuit, ownership of about 1,800 acres, a pittance, was returned to the Narragansett. In 1983, the federal government recognized the tribe as a sovereign nation. The State of Rhode Island, however, remained antagonistic.

As the 20th century wound down, the Narragansett sought to build a casino that might improve their economic circumstances, much as casinos across the border in Connecticut have for the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot peoples. But a 1996 budget-bill rider authored by the late Sen. John Chafee required the Narragansett to receive statewide voter approval. Voters have not granted it. None of America’s other 565 federally recognized tribes must get voter approval.

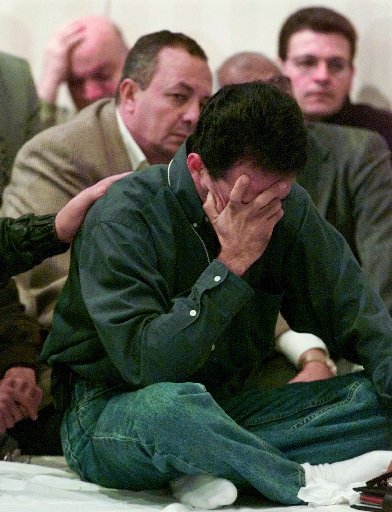

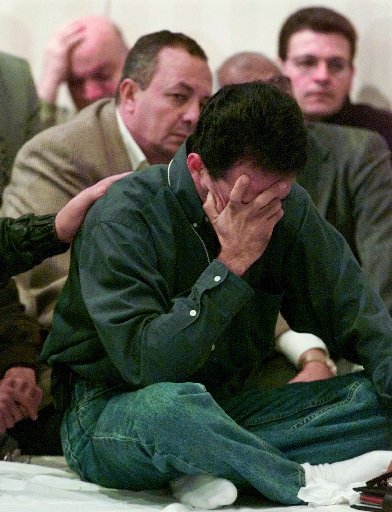

In 2003, another economic-development effort was crushed when the state police, acting on orders of then-Gov. Donald Carcieri, shut down the Narragansett’s tax-free smoke shop on July 14, the day after it opened. Police stormed the shop on tribal lands on South County Trail in Charlestown. Seven unarmed adult Narragansett were arrested, and several women and men, including Jennings’ son Adam, were injured.

“It looked like a war,” says Jennings. “We were all stunned.”

Carcieri called the raid “truly regrettable, but truly necessary,” and prompted by Narragansett’s “flagrant violation of state law.” Chief Sachem Matthew Thomas, one of those arrested, said the state ignored “the federal status of the tribe,” which allowed it to operate the store. “Governor Carcieri should be ashamed of himself,” Thomas said.

“Not once have the Town of Charlestown, the state police, or the State of Rhode Island come and apologized,” Jennings says. “And they need to.”

The immediate effect on the Narragansett community was demoralizing, says Spears, and not only because once again, an economic opportunity was denied: the violent arrests and injuries, recorded by many media outlets, brought viscerally to the surface earlier injustices dating to the Great Swamp Massacre.

“As a mother, my heart bled,” says Spears. “I thought my kids weren’t going to have to deal with this.”

In the wake of the smoke shop raid, Spears says, many Narragansett, including her and her aunt, were regularly followed and stopped by police without cause — and occasionally still are.

“We’re tailed because we are brown in an area of Rhode Island that is very white,” says Spears, whose husband, Robin Spears Jr., is a tribal environmental police officer. “I know there are good police officers, but the fact is that our family members get harassed. My mother was stopped not too long ago. Somebody didn’t believe it was her car because she drives a Volvo.”

The Rhode Island Indian Council website has a page on historical trauma, defining it as “the collective emotional and psychological injury both over the life span and across generations, resulting from a shattering history of genocide.”

The theory, embraced by many Native Americans but controversial in some quarters, seeks to help explain the significant rates of depression, suicide, substance abuse and domestic violence found in some Native American communities with long histories of suffering injustice and atrocity.

The autumn rain continues during Jennings’ visit to the monument marking Dec. 19, 1675.

Paulla Dove Jennings, left, and Lorén Spears.As she stands with her aunt, Spears describes the effect in metaphorical terms she heard from Elizabeth Hoover, a Brown University professor of American studies who is the daughter of a Micmac and Mohawk family. Passed down by an elder, the metaphor is of the succession of heavy bags of sand that Native Americans have carried, beginning with the 17th-century introduction of disease and loss of their homelands.

Paulla Dove Jennings, left, and Lorén Spears.As she stands with her aunt, Spears describes the effect in metaphorical terms she heard from Elizabeth Hoover, a Brown University professor of American studies who is the daughter of a Micmac and Mohawk family. Passed down by an elder, the metaphor is of the succession of heavy bags of sand that Native Americans have carried, beginning with the 17th-century introduction of disease and loss of their homelands.

“Each generation is trying to let one bag off, Spears says, “but it’s hard because we’re carrying all the pain of all those bags, and when the next generation after that is trying to pull their families back together, they’ve been so victimized and beaten down that they’re carrying the social woes — alcoholism, drug addiction, mental illness — just despondency.

“And you’ve got to try to start healing from that in order to take a bag off. I think our community has come a long way, but we’re still carrying the weight of a lot of those bags on our shoulders.”

At the monument, Jennings concludes her retelling of the Great Swamp Massacre by describing the connection she feels to the grandmother and child in her story.

“I always pictured that child as my grandmother Dove’s great-great-great-grandmother,” she says. “Without her surviving, my grandmother wouldn’t have been here. If my grandmother wasn’t here, my father wouldn’t have been here. And if my father wouldn’t have been here, I wouldn’t have been here. My children wouldn’t be here. My beautiful niece wouldn’t be here.

“But the inner strength that the Creator gave us — Cautantowwit gave us — to help us survive and nurture one another in any way that we can is why we come here and pay homage to those that were slaughtered.”

Says Spears: “It’s really a blessing and a powerful feeling to know that our ancestors truly are not only watching over us but their spirits are washing over us. They’re giving us what we need today to survive this period in time to bring our community forward.”

********

Publication Date: October 25, 2015 Page: 1 Section: A

EXETER – On this fine autumn morning, Paulla Dove Jennings welcomes a visitor into her house at the edge of woods with a handshake and a warm smile. She pours tea, sits at her kitchen table, and begins relating some of her life’s story, which in its essential elements mirrors that of her relatives and ancestors, Rhode Island’s Narragansett and Niantic people.

A tribal elder now at age 75, Jennings has been a waitress, chef, clerk, author, historian, educator, museum curator, state Indian Affairs Commissioner, Narragansett leader, and more. Gifted with words and possessing a keen memory, she today is a celebrated storyteller -- a woman who laughs easily, and who also can feel anger and pain at how some whites have treated her people since the Great Swamp Massacre of 1675 that nearly obliterated them. The Narragansett and Niantic are among the state’s original inhabitants, here for thousands of years.

“Oppression” is one word Jennings sometimes uses to describe that treatment.

“Racism” is another.

“Rhode Island has close to the same racism as in Mississippi and I’ve lived in both places,” says Jennings, a direct descendant of the great 17th-century Niantic sachem Ninigret.

“Rhode Island has close to the same racism as in Mississippi, and I’ve lived in both places,” says Jennings, a direct descendant of the great 17th-century Niantic sachem Ninigret.

Growing up in Rhode Island, Jennings says, she was called “dumb Indian” and “redskin” and the N-word. When she was a young married woman, landlords wouldn’t rent apartments to her family because she was brown-skinned. She watched her father, husband and other Native relatives and friends endure employment discrimination, a practice that continues today, she says.

“I couldn’t understand where this was coming from,” she says. “My family has always said that even though there are houses, there are roads, there are buildings, ‘this is your land, this is your home. Mother Earth is there underneath all this other stuff.’”

In the wake of the July 14, 2003, Smoke Shop Raid, in which state police arrested seven Narragansett, including her son, injuring several, she and other Natives were followed around — racially profiled — and that practice continues, she says. And there are many other ways, she says, in which historical injustices against her people continue to have impact in 2015.

“It just hurts my heart,” says Jennings. “I’ve reached the stage where I want good things to happen, uplifting things. I want the next generation to feel good about themselves and want to stay here and not leave Rhode Island, but that’s what’s happening. They’re leaving — those that get the education, that get the opportunity.”

The numbers

Of Rhode Island’s just over a million people in the 2010 U.S. Census, 803,685 were white, and only 14,394 were Native American: 6,058 residents who identified themselves as being only Native American, and another 8,336 who identified themselves as of mixed Native and other race. Of the total, nearly half live in Providence, Pawtucket and Warwick; East Providence, Cranston and South Kingstown round out the top six.

With nearly 3,000 people on the Federal Recognition rolls, the Narragansett constitute the largest tribal group. Pequot, Wampanoag, Nipmuc and others make up the rest.

None of these numbers bring power in a white-dominated state.

“It’s such a small segment of the population,” says Darrell Waldron, a man of Narragansett and Wampanoag descent who heads the Providence-based Rhode Island Indian Council. “When you have a very, very small ... community by numbers, you’re ignored. The only time we are visually seen or we are visually respected is when we dress up in clothing that’s 500 years old and perform for somebody. And that is sad.”

More numbers reveal other disparities. Less than a third of Indian households own their homes, compared with nearly two-thirds of whites, according to the 2010 Census. Native household median income is $28,750; whites’ is $62,188, according to the Bureau’s 2013 five-year estimates. Thirty-three percent of the state’s Native people live in poverty; 9 percent of whites do.

Nearly 30 percent of Native Americans ages 18 to 64 reported having no health insurance, compared with 11 percent of whites in that age group, according to the Bureau’s 2013 five-year estimates. Almost a quarter of all Native American adults reported being unable to afford a doctor’s care when needed at least once a year, compared with 11.5 percent of whites, according to the state and federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Health Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2013.

Given the small size of the samples and some people’s distrust of government, which discourages them from sharing information, the true numbers could be somewhat different. But no one disputes that in Rhode Island, Natives are on an unequal footing with whites.

Heartache

As she waits for her 97-year-old mother, Eleanor Dove, to come downstairs, Jennings shows a visitor the many photographs of her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and other relatives and friends that fill her kitchen. She has been blessed, she says. And she has experienced heartache, personally and in the larger, tribal sense.

One of the four children of Ferris and Eleanor (Spears) Dove, Jennings grew up in Charlestown. The late Ferris, known as Roaring Bull, was the last traditional Narragansett war chief; a graduate of Bacone College, in Oklahoma, he became a supervisor at Electric Boat and was a postmaster in Rockville, and Exeter town moderator and tax assessor. He and Eleanor founded and for many years ran Dovecrest, a popular restaurant and trading post, now closed. They succeeded against odds, unlike some of their people.

Jennings attended public schools, deciding in her senior year to leave North Kingstown High School, where she was the only Native in her class, after wearying of racial mistreatment, she says. When she expressed an interest in medicine, perhaps dentistry, a guidance counselor suggested a dental assistant would be more appropriate for someone of her background.

“I dropped out because of racism,” she says. “I had one friend. That was because of the color of my skin.” Decades later, she earned her GED and attended the Community College of Rhode Island and the University of Rhode Island, where she began to develop her talent for storytelling.

In 1960, she married John Jennings, a carpenter of Cherokee, Natchez, white and black descent and moved with him and their young daughter to Mississippi, home of Natchez Indians. One day in 1962, Jennings says, white supremacists sprayed 18 bullets into his car, nearly killing him. Ambulance drivers refused to bring him to a hospital, so a cousin who ran a funeral parlor brought him in a hearse. Released from the hospital, he was fined $75 for disturbing the peace.

A couple of years later, they returned to Rhode Island with daughter Heidi and baby son Shawn. The family then moved briefly to Detroit, where John was stabbed during the city’s 1967 race riot. In 1972, Shawn died in a mechanical accident. He was 10.

In the 1990s, with the family back in Rhode Island, Jennings became involved in the Narragansett campaign to build a casino that might replicate the success of Foxwoods, which had helped alleviate tribal poverty among Connecticut’s Mashantucket Pequot people. But a 1996 budget-bill rider authored by the late Sen. John Chafee impeded the cause. Because of Chafee, the Narragansett, unique among America’s 566 federally recognized tribes, would need statewide voter approval. That approval has never come.

Desperate for economic development, the Narragansett, like other tribes in America, opened a tax-free tobacco shop 12 years ago. The state stepped in to halt the untaxed sale of cigarettes. Jennings was on duty at the smoke shop on July 14, 2003, when Rhode Island State Police stormed the compound, arresting seven unarmed adult Narragansett; several women and men were injured, including Jennings’ other son, Adam, who suffered a broken ankle and, in the aftermath, posttraumatic stress disorder.

“It looked like a war,” says Jennings. “I said, ‘This is happening in my country, in my state?’ The pain will never go away.”

The man who ordered the raid, then-Gov. Donald Carcieri, was unapologetic. “Today’s actions were precipitated by the Narragansett Indians and their flagrant violation of state law,” Carcieri said at a news conference during which then-state police Col. Steven Paré and then-Attorney General Patrick Lynch stood with him.

Enduring myths

The morning is advancing when Eleanor Dove descends the stairs. She greets Jennings’ guest and retires with the morning paper to her chair by the massive stone fireplace that relatives built. Like her daughter, Dove is a faithful follower of the news.

Jennings has clipped two outside columns recently published on the op-ed pages of The Providence Journal: one on white privilege and another on King Philip’s War and the Great Swamp Massacre. Both contain derogatory stereotypes and historical inaccuracies, Jennings says, that offended her and many of her people and prompted them to write letters to the editor. Such perspectives still anger her, even though she has read and heard them for a lifetime.

“Outrageous. Filled with myths and falsehoods and sanctimonious lies,” she says.

These perspectives, she asserts, derive from paternalization that dates to the time of Roger Williams.

“‘Great White Father’ always thinks they have to support us, and tell us what to do, and how to do it — that we don’t know our heritage, our culture, how to take care of ourselves,” Jennings says. “It’s all about power. And I get frustrated and angry. I’m 75 now. And maybe I’ll get over the frustration or things will begin to change before I go to the Sky World, but until that time, I’m going to say what the truth is.”

Like Jennings, Thawn Harris, 37, a Narragansett who lives in Charlestown and teaches physical education at the Met School, has been subjected to insults. He, too, has been stereotyped.

“Being a Native person, you get asked some crazy things and people look at you in crazy ways, like they expect you to be able to talk to animals or ‘can I make the rain stop, can I do a sun dance?’” he says. “Absolutely ridiculous questions like that.”

Questions like, “Are you full-blooded?” which has been put to Jennings many times.

She says: “Who else gets asked those questions: ‘Are you all white? Are you all black? Are you all Asian, Chinese, Korean, whatever?’ It’s unfair, it’s dehumanizing, and it’s hurtful.”

Confining image

Among the stereotypes is what Harris calls “this Hollywood, mystical feeling of how Native Americans should be, how they should look.”

Except for occasional ceremonial events honoring their traditions, most dress in contemporary fashion, of course. Paradoxically, that fosters what Harris, Jennings and other Natives describe as “invisibility” — and not only visually.

“If we’re not walking around in leather skins with feathers hanging off us, if we don’t have that stereotypical look, if we don’t have long hair — if we’re not living a life that is not like out in the middle of nowhere, not living in a teepee, which we never lived in — they don’t even see us,” says Harris, who wears his hair short.

“We are very much invisible, not recognized at all; in a lot of things, we’re overlooked and forgotten. When people do think of us, it is, whether pro or con, in the light of ‘oh, the Indians want a casino.’”

Stereotyping is at the heart of the controversies embroiling the Indian names and mascots of some sports teams, notably the National Football League’s Washington Redskins, whose owner has refused demands to be more sensitive to the many Native Americans across the country who hold the word “redskin” to be offensive.

Jennings puts it this way:

“OK, let’s change the Yankees name to ‘The Honkies.’ Or ‘The White Trash’ or something else that’s negative and nasty and shouldn’t be said out loud.”

‘A beginning step’

Progress will require a better understanding of disparities and a commitment by officials and others to address them, says Waldron.

“Until we can begin to sit at the table and really discuss poverty disparities with families and equal access for all of our people regardless of what color they are, these problems are going to continue to be there,” he says.

Progress also will require education, say Jennings and niece Lorén Spears, 49, a former teacher who now directs Exeter’s Tomaquag Museum, dedicated to the culture and history of Narragansett, Niantic and other indigenous peoples. Most Rhode Island schoolchildren are taught little about the history and contemporary circumstances of the state’s original inhabitants.

Tomaquag’s exhibits and programs tell that story. So does Spears in her one-on-one encounters with museum visitors, many of whom are white.

“I’m not blaming them for any of this history,” Spears says. “And if they apologize, I say ‘You don’t have to apologize. You didn’t do this, but I do want you to understand it so we don’t repeat it and that you can help other people understand.’”

“What I would like to see happen is actual Native culture taught in the Rhode Island schools, as a beginning step,” says Jennings. “To do away with some of the myths that are on the history books, the social-studies books, and give what actually went on. Our true history, not made-up history.”

With reports from staff writer Paul Edward Parker.

The massacre, on Dec. 19, 1675, is far and away the bloodiest event in Rhode Island history. It still reverberates today, nearly three and a half centuries later.

Publication Date: October 26, 2015 Page: 1 Section: A

Providence Journal illustration by Tom Murphy.

Providence Journal illustration by Tom Murphy.A gentle rain falls on Paulla Dove Jennings as she stands by a monument deep in the South Kingstown woods. She has come here on this autumn morning to tell the story of the Great Swamp Massacre, in which white colonialists slaughtered and burned alive hundreds of her Narragansett and Niantic ancestors. Many were elders, women and children.

The massacre, on Dec. 19, 1675, was far and away the bloodiest event in Rhode Island history. Its repercussions are still felt today, nearly three and a half centuries later.

The backdrop was King Philip’s War, during which English settlers and some of New England’s Native American tribes fought, with devastating consequences for all. At the start, Jennings’ ancestors declared their neutrality, but they feared a white offensive. As winter approached that first year, many hundreds of them sought sanctuary on a remote island, farther into the wilderness from today’s monument.

They were living in long houses — large timber lodges that provided shelter for dozens of extended families.

“There was warmth,” says Jennings, 75, an educator, author and nationally acclaimed storyteller. “There was food stored. You shared. It was all right there so they could get through the winter.”

Extreme cold that December of 1675 had frozen the swamp solid, providing easy access for the colonialists, who suspected that the Narragansett and Niantic people were providing sanctuary to members of the Wampanoag tribe, the whites’ principal adversaries. On the afternoon of Dec. 19, they stormed the island with guns, blades and fire. In her telling, Jennings assumes the persona of a Native grandmother who was there with a young child.

“You could feel the pain. You could peek out and look and you could see people on fire, people being slaughtered, people being shot. Children, falling dead. And I’m thinking of how to get away, how do we survive, with these flames and these guns going off and people with daggers and swords and spears — and they’re trying to kill us, and you’re seeing the blood and you’re hearing the cries and you’re hearing the moans.

“And after all of this, the shock of it. How can man’s inhumanity to man be so strong? How they could be so hateful? When it was our land, our people.”

The colonialists captured a number of survivors and later sold some into slavery. Some of those who escaped fled as far away as Wisconsin, while others retreated deeper into the woods and swamps of South County, into parts of what are now known as Charlestown, South Kingstown and Westerly.

Further tragedy awaited them and the other tribes that ultimately were defeated in King Philip’s War, which left many Native communities and white towns in ruin, including Providence, founded by Roger Williams, an early friend of the Narragansett. Diseases introduced by the English claimed many. Tribal lands were taken, until, by the late 1700s, Narragansett territory had been reduced to about 15,000 acres, a fraction of what had been theirs for thousands of years. The Founding Fathers disparaged them in the Declaration of Independence, writing this often-overlooked clause near its end, referring to King George III:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

“That always just astounds me,” Jennings says. “We didn’t come with the cannon. We didn’t come with the gun. We didn’t invade [settlers’] territory. And yet we’re vilified.”

The Narragansett and Niantic struggled into the latter part of the 19th century — and then came another blow, one more injurious than words. In defiance of federal law, the Rhode Island General Assembly in 1880 “detribalized” the Narragansett, abolishing tribal authority and eventually selling all but two acres of the tribe’s land. In her Exeter home, Jennings keeps a copy of the poster that announced the first offering.

Sale of the Indian Reservation, it begins. There will be sold at public auction, in the town of Charlestown, commencing on Tuesday, July 11, 1882, at 10 o’clock a.m., at or near the Indian Meeting House … first parcel embraces the Indian Cedar Swamp, including ‘School House Island’…

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought the federal policy of “forced assimilation” of members of the Narragansett and other tribes across the United States. Government officials intended to essentially remake Indians into whites by forcibly remanding them to specialized boarding schools where their Native American culture was stripped away.

One of the most notorious was the United States Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, founded in 1879 by Army Capt. Richard Henry Pratt, who wrote that a Native American “is born a blank, like all the rest of us. Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of a civilization and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit.” His motto was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

Records at Exeter’s Tomaquag Museum, which preserves the culture and history of Rhode Island’s indigenous people, chronicle the fate of the Narragansett men who were sent to Carlisle.

“The entire purpose,” says museum head Lorén Spears, who is Jennings’ niece, “was to take you far away from home, keep you there for years on end and strip of you everything you know — your language, your culture, your community, your family. Change your clothes, change your hair, change your religion — literally strip you of everything you know as being Narragansett or any Native American nation group.”

In 1978, after a land-claim lawsuit, ownership of about 1,800 acres, a pittance, was returned to the Narragansett. In 1983, the federal government recognized the tribe as a sovereign nation. The State of Rhode Island, however, remained antagonistic.

As the 20th century wound down, the Narragansett sought to build a casino that might improve their economic circumstances, much as casinos across the border in Connecticut have for the Mohegan and Mashantucket Pequot peoples. But a 1996 budget-bill rider authored by the late Sen. John Chafee required the Narragansett to receive statewide voter approval. Voters have not granted it. None of America’s other 565 federally recognized tribes must get voter approval.

In 2003, another economic-development effort was crushed when the state police, acting on orders of then-Gov. Donald Carcieri, shut down the Narragansett’s tax-free smoke shop on July 14, the day after it opened. Police stormed the shop on tribal lands on South County Trail in Charlestown. Seven unarmed adult Narragansett were arrested, and several women and men, including Jennings’ son Adam, were injured.

“It looked like a war,” says Jennings. “We were all stunned.”

Carcieri called the raid “truly regrettable, but truly necessary,” and prompted by Narragansett’s “flagrant violation of state law.” Chief Sachem Matthew Thomas, one of those arrested, said the state ignored “the federal status of the tribe,” which allowed it to operate the store. “Governor Carcieri should be ashamed of himself,” Thomas said.

“Not once have the Town of Charlestown, the state police, or the State of Rhode Island come and apologized,” Jennings says. “And they need to.”

The immediate effect on the Narragansett community was demoralizing, says Spears, and not only because once again, an economic opportunity was denied: the violent arrests and injuries, recorded by many media outlets, brought viscerally to the surface earlier injustices dating to the Great Swamp Massacre.

“As a mother, my heart bled,” says Spears. “I thought my kids weren’t going to have to deal with this.”

In the wake of the smoke shop raid, Spears says, many Narragansett, including her and her aunt, were regularly followed and stopped by police without cause — and occasionally still are.

“We’re tailed because we are brown in an area of Rhode Island that is very white,” says Spears, whose husband, Robin Spears Jr., is a tribal environmental police officer. “I know there are good police officers, but the fact is that our family members get harassed. My mother was stopped not too long ago. Somebody didn’t believe it was her car because she drives a Volvo.”

The Rhode Island Indian Council website has a page on historical trauma, defining it as “the collective emotional and psychological injury both over the life span and across generations, resulting from a shattering history of genocide.”

The theory, embraced by many Native Americans but controversial in some quarters, seeks to help explain the significant rates of depression, suicide, substance abuse and domestic violence found in some Native American communities with long histories of suffering injustice and atrocity.

The autumn rain continues during Jennings’ visit to the monument marking Dec. 19, 1675.

Paulla Dove Jennings, left, and Lorén Spears.As she stands with her aunt, Spears describes the effect in metaphorical terms she heard from Elizabeth Hoover, a Brown University professor of American studies who is the daughter of a Micmac and Mohawk family. Passed down by an elder, the metaphor is of the succession of heavy bags of sand that Native Americans have carried, beginning with the 17th-century introduction of disease and loss of their homelands.

Paulla Dove Jennings, left, and Lorén Spears.As she stands with her aunt, Spears describes the effect in metaphorical terms she heard from Elizabeth Hoover, a Brown University professor of American studies who is the daughter of a Micmac and Mohawk family. Passed down by an elder, the metaphor is of the succession of heavy bags of sand that Native Americans have carried, beginning with the 17th-century introduction of disease and loss of their homelands. “Each generation is trying to let one bag off, Spears says, “but it’s hard because we’re carrying all the pain of all those bags, and when the next generation after that is trying to pull their families back together, they’ve been so victimized and beaten down that they’re carrying the social woes — alcoholism, drug addiction, mental illness — just despondency.

“And you’ve got to try to start healing from that in order to take a bag off. I think our community has come a long way, but we’re still carrying the weight of a lot of those bags on our shoulders.”

At the monument, Jennings concludes her retelling of the Great Swamp Massacre by describing the connection she feels to the grandmother and child in her story.

“I always pictured that child as my grandmother Dove’s great-great-great-grandmother,” she says. “Without her surviving, my grandmother wouldn’t have been here. If my grandmother wasn’t here, my father wouldn’t have been here. And if my father wouldn’t have been here, I wouldn’t have been here. My children wouldn’t be here. My beautiful niece wouldn’t be here.

“But the inner strength that the Creator gave us — Cautantowwit gave us — to help us survive and nurture one another in any way that we can is why we come here and pay homage to those that were slaughtered.”

Says Spears: “It’s really a blessing and a powerful feeling to know that our ancestors truly are not only watching over us but their spirits are washing over us. They’re giving us what we need today to survive this period in time to bring our community forward.”

********

Publication Date: October 25, 2015 Page: 1 Section: A

EXETER – On this fine autumn morning, Paulla Dove Jennings welcomes a visitor into her house at the edge of woods with a handshake and a warm smile. She pours tea, sits at her kitchen table, and begins relating some of her life’s story, which in its essential elements mirrors that of her relatives and ancestors, Rhode Island’s Narragansett and Niantic people.

A tribal elder now at age 75, Jennings has been a waitress, chef, clerk, author, historian, educator, museum curator, state Indian Affairs Commissioner, Narragansett leader, and more. Gifted with words and possessing a keen memory, she today is a celebrated storyteller -- a woman who laughs easily, and who also can feel anger and pain at how some whites have treated her people since the Great Swamp Massacre of 1675 that nearly obliterated them. The Narragansett and Niantic are among the state’s original inhabitants, here for thousands of years.

“Oppression” is one word Jennings sometimes uses to describe that treatment.

“Racism” is another.

“Rhode Island has close to the same racism as in Mississippi and I’ve lived in both places,” says Jennings, a direct descendant of the great 17th-century Niantic sachem Ninigret.

“Rhode Island has close to the same racism as in Mississippi, and I’ve lived in both places,” says Jennings, a direct descendant of the great 17th-century Niantic sachem Ninigret.

Growing up in Rhode Island, Jennings says, she was called “dumb Indian” and “redskin” and the N-word. When she was a young married woman, landlords wouldn’t rent apartments to her family because she was brown-skinned. She watched her father, husband and other Native relatives and friends endure employment discrimination, a practice that continues today, she says.

“I couldn’t understand where this was coming from,” she says. “My family has always said that even though there are houses, there are roads, there are buildings, ‘this is your land, this is your home. Mother Earth is there underneath all this other stuff.’”

In the wake of the July 14, 2003, Smoke Shop Raid, in which state police arrested seven Narragansett, including her son, injuring several, she and other Natives were followed around — racially profiled — and that practice continues, she says. And there are many other ways, she says, in which historical injustices against her people continue to have impact in 2015.

“It just hurts my heart,” says Jennings. “I’ve reached the stage where I want good things to happen, uplifting things. I want the next generation to feel good about themselves and want to stay here and not leave Rhode Island, but that’s what’s happening. They’re leaving — those that get the education, that get the opportunity.”

The numbers

Of Rhode Island’s just over a million people in the 2010 U.S. Census, 803,685 were white, and only 14,394 were Native American: 6,058 residents who identified themselves as being only Native American, and another 8,336 who identified themselves as of mixed Native and other race. Of the total, nearly half live in Providence, Pawtucket and Warwick; East Providence, Cranston and South Kingstown round out the top six.

With nearly 3,000 people on the Federal Recognition rolls, the Narragansett constitute the largest tribal group. Pequot, Wampanoag, Nipmuc and others make up the rest.

None of these numbers bring power in a white-dominated state.

“It’s such a small segment of the population,” says Darrell Waldron, a man of Narragansett and Wampanoag descent who heads the Providence-based Rhode Island Indian Council. “When you have a very, very small ... community by numbers, you’re ignored. The only time we are visually seen or we are visually respected is when we dress up in clothing that’s 500 years old and perform for somebody. And that is sad.”

More numbers reveal other disparities. Less than a third of Indian households own their homes, compared with nearly two-thirds of whites, according to the 2010 Census. Native household median income is $28,750; whites’ is $62,188, according to the Bureau’s 2013 five-year estimates. Thirty-three percent of the state’s Native people live in poverty; 9 percent of whites do.

Nearly 30 percent of Native Americans ages 18 to 64 reported having no health insurance, compared with 11 percent of whites in that age group, according to the Bureau’s 2013 five-year estimates. Almost a quarter of all Native American adults reported being unable to afford a doctor’s care when needed at least once a year, compared with 11.5 percent of whites, according to the state and federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Health Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011-2013.

Given the small size of the samples and some people’s distrust of government, which discourages them from sharing information, the true numbers could be somewhat different. But no one disputes that in Rhode Island, Natives are on an unequal footing with whites.

Heartache

As she waits for her 97-year-old mother, Eleanor Dove, to come downstairs, Jennings shows a visitor the many photographs of her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and other relatives and friends that fill her kitchen. She has been blessed, she says. And she has experienced heartache, personally and in the larger, tribal sense.

One of the four children of Ferris and Eleanor (Spears) Dove, Jennings grew up in Charlestown. The late Ferris, known as Roaring Bull, was the last traditional Narragansett war chief; a graduate of Bacone College, in Oklahoma, he became a supervisor at Electric Boat and was a postmaster in Rockville, and Exeter town moderator and tax assessor. He and Eleanor founded and for many years ran Dovecrest, a popular restaurant and trading post, now closed. They succeeded against odds, unlike some of their people.

Jennings attended public schools, deciding in her senior year to leave North Kingstown High School, where she was the only Native in her class, after wearying of racial mistreatment, she says. When she expressed an interest in medicine, perhaps dentistry, a guidance counselor suggested a dental assistant would be more appropriate for someone of her background.

“I dropped out because of racism,” she says. “I had one friend. That was because of the color of my skin.” Decades later, she earned her GED and attended the Community College of Rhode Island and the University of Rhode Island, where she began to develop her talent for storytelling.

In 1960, she married John Jennings, a carpenter of Cherokee, Natchez, white and black descent and moved with him and their young daughter to Mississippi, home of Natchez Indians. One day in 1962, Jennings says, white supremacists sprayed 18 bullets into his car, nearly killing him. Ambulance drivers refused to bring him to a hospital, so a cousin who ran a funeral parlor brought him in a hearse. Released from the hospital, he was fined $75 for disturbing the peace.

A couple of years later, they returned to Rhode Island with daughter Heidi and baby son Shawn. The family then moved briefly to Detroit, where John was stabbed during the city’s 1967 race riot. In 1972, Shawn died in a mechanical accident. He was 10.

In the 1990s, with the family back in Rhode Island, Jennings became involved in the Narragansett campaign to build a casino that might replicate the success of Foxwoods, which had helped alleviate tribal poverty among Connecticut’s Mashantucket Pequot people. But a 1996 budget-bill rider authored by the late Sen. John Chafee impeded the cause. Because of Chafee, the Narragansett, unique among America’s 566 federally recognized tribes, would need statewide voter approval. That approval has never come.

Desperate for economic development, the Narragansett, like other tribes in America, opened a tax-free tobacco shop 12 years ago. The state stepped in to halt the untaxed sale of cigarettes. Jennings was on duty at the smoke shop on July 14, 2003, when Rhode Island State Police stormed the compound, arresting seven unarmed adult Narragansett; several women and men were injured, including Jennings’ other son, Adam, who suffered a broken ankle and, in the aftermath, posttraumatic stress disorder.

“It looked like a war,” says Jennings. “I said, ‘This is happening in my country, in my state?’ The pain will never go away.”

The man who ordered the raid, then-Gov. Donald Carcieri, was unapologetic. “Today’s actions were precipitated by the Narragansett Indians and their flagrant violation of state law,” Carcieri said at a news conference during which then-state police Col. Steven Paré and then-Attorney General Patrick Lynch stood with him.

Enduring myths

The morning is advancing when Eleanor Dove descends the stairs. She greets Jennings’ guest and retires with the morning paper to her chair by the massive stone fireplace that relatives built. Like her daughter, Dove is a faithful follower of the news.

Jennings has clipped two outside columns recently published on the op-ed pages of The Providence Journal: one on white privilege and another on King Philip’s War and the Great Swamp Massacre. Both contain derogatory stereotypes and historical inaccuracies, Jennings says, that offended her and many of her people and prompted them to write letters to the editor. Such perspectives still anger her, even though she has read and heard them for a lifetime.

“Outrageous. Filled with myths and falsehoods and sanctimonious lies,” she says.

These perspectives, she asserts, derive from paternalization that dates to the time of Roger Williams.

“‘Great White Father’ always thinks they have to support us, and tell us what to do, and how to do it — that we don’t know our heritage, our culture, how to take care of ourselves,” Jennings says. “It’s all about power. And I get frustrated and angry. I’m 75 now. And maybe I’ll get over the frustration or things will begin to change before I go to the Sky World, but until that time, I’m going to say what the truth is.”

Like Jennings, Thawn Harris, 37, a Narragansett who lives in Charlestown and teaches physical education at the Met School, has been subjected to insults. He, too, has been stereotyped.

“Being a Native person, you get asked some crazy things and people look at you in crazy ways, like they expect you to be able to talk to animals or ‘can I make the rain stop, can I do a sun dance?’” he says. “Absolutely ridiculous questions like that.”

Questions like, “Are you full-blooded?” which has been put to Jennings many times.

She says: “Who else gets asked those questions: ‘Are you all white? Are you all black? Are you all Asian, Chinese, Korean, whatever?’ It’s unfair, it’s dehumanizing, and it’s hurtful.”

Confining image

Among the stereotypes is what Harris calls “this Hollywood, mystical feeling of how Native Americans should be, how they should look.”

Except for occasional ceremonial events honoring their traditions, most dress in contemporary fashion, of course. Paradoxically, that fosters what Harris, Jennings and other Natives describe as “invisibility” — and not only visually.

“If we’re not walking around in leather skins with feathers hanging off us, if we don’t have that stereotypical look, if we don’t have long hair — if we’re not living a life that is not like out in the middle of nowhere, not living in a teepee, which we never lived in — they don’t even see us,” says Harris, who wears his hair short.

“We are very much invisible, not recognized at all; in a lot of things, we’re overlooked and forgotten. When people do think of us, it is, whether pro or con, in the light of ‘oh, the Indians want a casino.’”

Stereotyping is at the heart of the controversies embroiling the Indian names and mascots of some sports teams, notably the National Football League’s Washington Redskins, whose owner has refused demands to be more sensitive to the many Native Americans across the country who hold the word “redskin” to be offensive.

Jennings puts it this way:

“OK, let’s change the Yankees name to ‘The Honkies.’ Or ‘The White Trash’ or something else that’s negative and nasty and shouldn’t be said out loud.”

‘A beginning step’

Progress will require a better understanding of disparities and a commitment by officials and others to address them, says Waldron.