G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 16

May 18, 2018

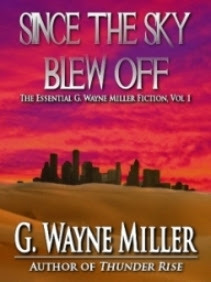

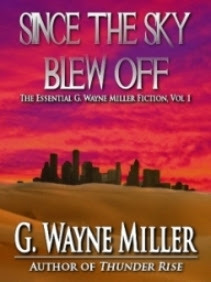

#33Stories: Day 18, "Since the Sky Blew Off," a screen treatment with Drew Smith

#33Stories

No. 18: “Since the Sky Blew Off,” a screen treatment with Drew Smith

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Writers Guild of American registration no. 1946967

The movie opens with a catastrophic planet-wide natural disaster that destroys civilization as we know it, leaving a few “good” people and bands of savage Roamers who ruthlessly prey on them and each other…Pickup midway through Act I:

TWO GENERATIONS (about 40 years) PASS.

The Dark Ages have settled on the world. A lawless landscape in which most traces of civilization are gone. No electricity, no Internet, no writing, no agriculture…

In this time, when the sky is mostly gone and CO2, methane and other gas levels are at dangerous levels, the atmosphere is poisonous. It affects health –– and mental health, progressively crippling the central nervous system and leading to loss of INDIVIDUAL MEMORY, minor at first but eventually terminal. The first, minor signs (forgetting where you left your keys, to use an example from our world) are in your teens; by your mid 20s, the signs are unmistakable (you begin to lose critical skills, such the ability to defend yourself against roamers); by 30, you are descending into senile dementia and in this eat-or-be-eaten world, you are eaten, by the younger generation. And if you somehow manage to survive, you are dead by 35, almost without exception. But there ARE exceptions – a few grizzled oldsters somehow survive, demented for the most part, wigged out, but alive (think of the lifelong chain-smoker who is still going strong at 80, rare as hell, but it happens).

Also lost is COLLECTIVE MEMORY. The memory of how life used to be in what is called “THE OTHER TIME” survives only in dribs and drabs of disjointed and unreliable oral stories and the occasional artifact that our protagonists will stumble upon in Act II (a burned-out movie theater, for example, or a wind-blown page of a book; think of the clues that CAVE ART give us today of our prehistoric ancestors).

No one celebrates the birth of a child –– it’s just a burden. In their savagery, many Roamers kill newborn babies, who are seen as a “drain’ on precious resources. (Think Chinese peasants drowning baby girls for real-life analogy.)

No one has the time or inspiration for any kind of creative ART –– no painting, no poetry, no books, nothing. NO ONE CAN READ.

Importantly, in light of how our main characters “come to life” in ACT III, no one LAUGHS any more. LAUGHTER seems to have been bred out of the species.

INT. FORTIFIED COMPOUND ON CAPE COD – AFTERNOONMATHER, 30 years old, and RACHEL, 28 –– evidently a “couple” –– and two comrades, TRISTAN, 22, and SARAH, 23, live together in a crude shack near the shore. It is surrounded by rusty barbed wire, rocks, etc. It is cooler here than the interior, and the ocean, while poisoned, still produces (barely edible) fish, mainstay of the diet.We see that Mather is mentally the slowest of the four –– he’s in the “forgetting where I put the keys” phase. Rachel is not, yet. Being younger, Sarah and Tristan are still sharp, and Rachel and Mather are increasingly relying on them to keep their shit together. They are especially valuable when defending the compound.None of the four remember any longer how they came to be together –– prior to the previous four or five years, all is a blank. In other words, they have NO STORY.

INT. A NEARBY ROAMER COMPOUND – EVENINGA nameless female Roamer gives birth to a child. Male Roamers immediately kill it. This excites them. They whoop and holler and leave their compound, bent on destruction.

EXT. FORTIFIED COMPOUND ON CAPE COD – NIGHTThe Roamers attack the Rachel/Mather compound –– and this time, Tristan and Sarah are killed. Rachel and Mather barely escape with their lives and make their way on a BICYCLE-BUILT-FOR-TWO (no more working cars or fuel) to BOSTON, in ruins…

EXT. BOSTON - DAYAs they behold the dead city, a flash of light atop the burnt-out John Hancock building catches their eye. Must be just the brutal sun, right, glinting off metal? Can’t be a person, can it? But it is –– it’s BIRDMAN, a grizzled, crazy man in his 70s beckoning them up. Rachel and Mather are leery. So Birdman sends down a carrier pigeon –– itself a startling development, as most birds have disappeared. The carrier pigeon has this message from Birdman:

I AM FRIENDLY. I HAVE FOOD. COME ON UP.But the two cannot read the message, of course. But it’s obvious that they can’t read. Watching through binoculars, Birdman realizes this. He shouts down that he has “GOOD FOOD, YOU MUST BE HUNGRY” (and they are), his voice carrying in the dead air. Warily, Rachel and Mather enter the skyscraper.

INT. JOHN HANCOCK BUILDING – DAYUp through the gloomy stairwells they go, questioning their judgment but so hungry they keep rising. As they get near the top, the encounter corpses of dead Roamers who have tried to get up here but were beaten back by Birdman.

EXT. JOHN HANCOCK BUILDING OBSERVATION DECK – DAYBirdman opens a steel door and lets them in. The air here is fresher, one of the secrets to Birdman’s existence. We see a street sign: CROW TOWN. Birdman has written “OLD” on it so that it now reads OLD CROW TOWN.

This is a place of marvels for Rachel and Mather. Birdman has a bunch of tame crows, including a talking crow (who says “Got birds?”), and a few songbirds he has managed to keep alive and reproductive. Rachel and Mather have never heard a songbird –– and they are amazed and soothed. For Birdman, the birds have become a substitute for people. He can talk to his crows. His mourning doves speak to the sadness of the world. Songbirds speak to joy… etc.

And he has chickens –– they produce the eggs that are the mainstay of his diet. Birdman collects rainwater, which he uses to grow a few hardy crops (the air is better here, remember) that he uses to feed himself and his birds. Birdman offers the couple eggs, which they enjoy –– for the first time.

As they eat, Birdman spins a yarn (or is it true?). He claims to recognize Mather – that’s why when he spotted him through his binoculars he invited him up. Birdman has never met Mather, but he looks exactly like a dear old friend of his, a man named LEONARDO. Birdman says that surely Mather is Leonardo’s grandson –– how else to explain the stunning similarity?

Rachel and Mather are skeptical –– until Birdman shows him an old photo of Leonardo, before the sky blew off. The similarity is truly remarkable.

Birdman, in a shaman-like dialogue, claims that Mather’s arrival here has been pre-ordained. For just recently, a carrier pigeon arrived from Nordenland, to which Leonardo, a wealthy young man before the sky blew off, evacuated as civilization was dying. Rachel and Mather have heard rumors of this place, but until now believe it to be mythical, a sort of Nirvana that doesn’t really exist. Birdman shows the various messages the pigeons have brought: in summary, they claim that the earth’s atmosphere over Nordenland shows rising levels of natural O2, decreasing levels of CO2. Nature herself is responsible. (And our real-life planet earth has a long history of healing itself: returning from ice ages, for example; recovering from the massive meteor strike that killed the dinosaurs and paved the way for mammals to rule the planet; and regional recovery from the massive soot sent into the atmosphere by giant volcanic eruptions.)

Birdman speculates that this pristine air can actually reverse dementia. This is good news on an individual level, of course –– especially for Mather, who’s losing it rapidly –– and also on the larger level of hope for humanity.

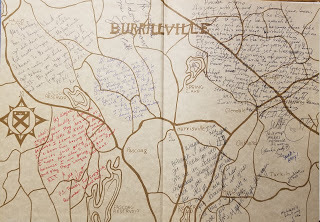

Birdman is too old to make the trip –– he’s happy here, anyway, crazy with his crows. But he urges Rachel and Mather to go –– what do they have to lose? Birdman has a map. He also has an old Polaroid camera, still working, and he takes a picture of him with the couple. Photography is a further marvel for Rachel and Mather.

Along with the photo (which will show proof of the couple’s meeting with Birdman), Birdman writes a letter of introduction to Leonardo.

And so Rachel and Mather set off…

-- 30 --

Context:

Of my many collaborations with Drew Smith, this may be my favorite -- and the lead, Birdman, one of my favorite fictional characters. It evolved from my short story of the same name, and over the many months we spitballed back and forth, we gave it varying names, “The Memory Bank” being one. Yes, this is another dystopian work, and it rings a true today as when we wrote it a few years back – perhaps more so, as climate change continues to jeopardize the planet and the life forms that inhabit it (for now, anyway).

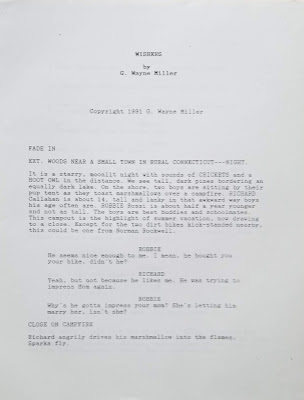

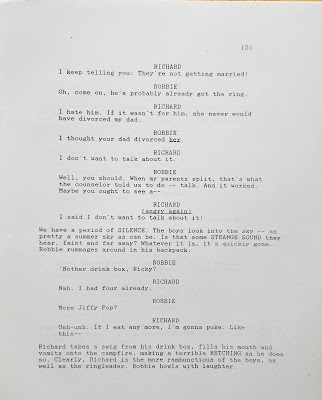

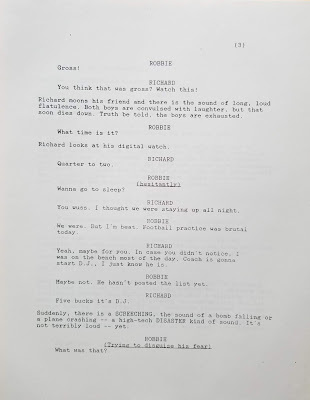

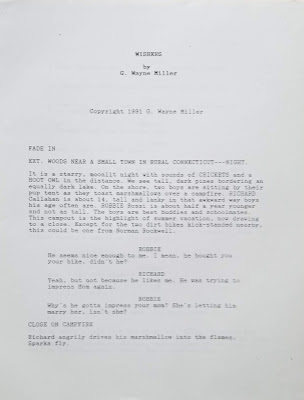

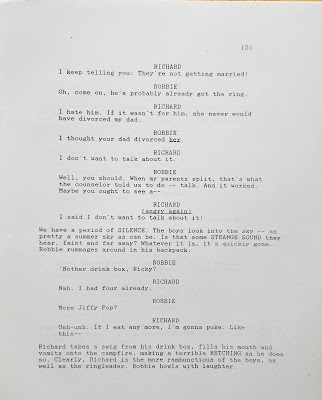

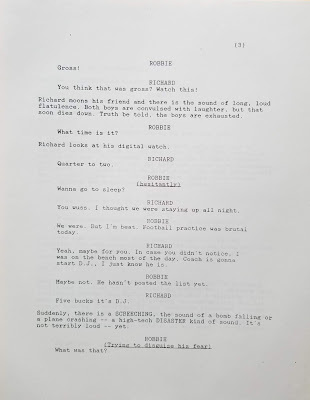

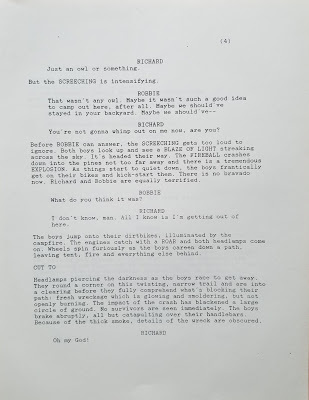

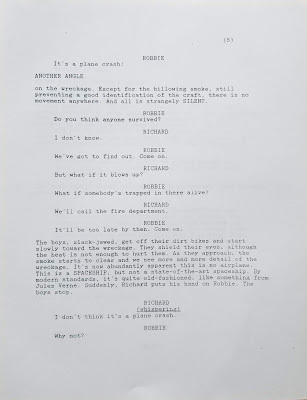

And humor me as I open the old writer’s trunk to reveal another screen project, much older than “Since the Sky Blew Off” – a completed full script for “Wishers,” which I completed more than a quarter of a century ago. Less dystopian than pure science fiction, it has flavors of early Spielberg. Herewith the first six pages. As you can see, this is literally from the trunk:

No. 18: “Since the Sky Blew Off,” a screen treatment with Drew Smith

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Writers Guild of American registration no. 1946967

The movie opens with a catastrophic planet-wide natural disaster that destroys civilization as we know it, leaving a few “good” people and bands of savage Roamers who ruthlessly prey on them and each other…Pickup midway through Act I:

TWO GENERATIONS (about 40 years) PASS.

The Dark Ages have settled on the world. A lawless landscape in which most traces of civilization are gone. No electricity, no Internet, no writing, no agriculture…

In this time, when the sky is mostly gone and CO2, methane and other gas levels are at dangerous levels, the atmosphere is poisonous. It affects health –– and mental health, progressively crippling the central nervous system and leading to loss of INDIVIDUAL MEMORY, minor at first but eventually terminal. The first, minor signs (forgetting where you left your keys, to use an example from our world) are in your teens; by your mid 20s, the signs are unmistakable (you begin to lose critical skills, such the ability to defend yourself against roamers); by 30, you are descending into senile dementia and in this eat-or-be-eaten world, you are eaten, by the younger generation. And if you somehow manage to survive, you are dead by 35, almost without exception. But there ARE exceptions – a few grizzled oldsters somehow survive, demented for the most part, wigged out, but alive (think of the lifelong chain-smoker who is still going strong at 80, rare as hell, but it happens).

Also lost is COLLECTIVE MEMORY. The memory of how life used to be in what is called “THE OTHER TIME” survives only in dribs and drabs of disjointed and unreliable oral stories and the occasional artifact that our protagonists will stumble upon in Act II (a burned-out movie theater, for example, or a wind-blown page of a book; think of the clues that CAVE ART give us today of our prehistoric ancestors).

No one celebrates the birth of a child –– it’s just a burden. In their savagery, many Roamers kill newborn babies, who are seen as a “drain’ on precious resources. (Think Chinese peasants drowning baby girls for real-life analogy.)

No one has the time or inspiration for any kind of creative ART –– no painting, no poetry, no books, nothing. NO ONE CAN READ.

Importantly, in light of how our main characters “come to life” in ACT III, no one LAUGHS any more. LAUGHTER seems to have been bred out of the species.

INT. FORTIFIED COMPOUND ON CAPE COD – AFTERNOONMATHER, 30 years old, and RACHEL, 28 –– evidently a “couple” –– and two comrades, TRISTAN, 22, and SARAH, 23, live together in a crude shack near the shore. It is surrounded by rusty barbed wire, rocks, etc. It is cooler here than the interior, and the ocean, while poisoned, still produces (barely edible) fish, mainstay of the diet.We see that Mather is mentally the slowest of the four –– he’s in the “forgetting where I put the keys” phase. Rachel is not, yet. Being younger, Sarah and Tristan are still sharp, and Rachel and Mather are increasingly relying on them to keep their shit together. They are especially valuable when defending the compound.None of the four remember any longer how they came to be together –– prior to the previous four or five years, all is a blank. In other words, they have NO STORY.

INT. A NEARBY ROAMER COMPOUND – EVENINGA nameless female Roamer gives birth to a child. Male Roamers immediately kill it. This excites them. They whoop and holler and leave their compound, bent on destruction.

EXT. FORTIFIED COMPOUND ON CAPE COD – NIGHTThe Roamers attack the Rachel/Mather compound –– and this time, Tristan and Sarah are killed. Rachel and Mather barely escape with their lives and make their way on a BICYCLE-BUILT-FOR-TWO (no more working cars or fuel) to BOSTON, in ruins…

EXT. BOSTON - DAYAs they behold the dead city, a flash of light atop the burnt-out John Hancock building catches their eye. Must be just the brutal sun, right, glinting off metal? Can’t be a person, can it? But it is –– it’s BIRDMAN, a grizzled, crazy man in his 70s beckoning them up. Rachel and Mather are leery. So Birdman sends down a carrier pigeon –– itself a startling development, as most birds have disappeared. The carrier pigeon has this message from Birdman:

I AM FRIENDLY. I HAVE FOOD. COME ON UP.But the two cannot read the message, of course. But it’s obvious that they can’t read. Watching through binoculars, Birdman realizes this. He shouts down that he has “GOOD FOOD, YOU MUST BE HUNGRY” (and they are), his voice carrying in the dead air. Warily, Rachel and Mather enter the skyscraper.

INT. JOHN HANCOCK BUILDING – DAYUp through the gloomy stairwells they go, questioning their judgment but so hungry they keep rising. As they get near the top, the encounter corpses of dead Roamers who have tried to get up here but were beaten back by Birdman.

EXT. JOHN HANCOCK BUILDING OBSERVATION DECK – DAYBirdman opens a steel door and lets them in. The air here is fresher, one of the secrets to Birdman’s existence. We see a street sign: CROW TOWN. Birdman has written “OLD” on it so that it now reads OLD CROW TOWN.

This is a place of marvels for Rachel and Mather. Birdman has a bunch of tame crows, including a talking crow (who says “Got birds?”), and a few songbirds he has managed to keep alive and reproductive. Rachel and Mather have never heard a songbird –– and they are amazed and soothed. For Birdman, the birds have become a substitute for people. He can talk to his crows. His mourning doves speak to the sadness of the world. Songbirds speak to joy… etc.

And he has chickens –– they produce the eggs that are the mainstay of his diet. Birdman collects rainwater, which he uses to grow a few hardy crops (the air is better here, remember) that he uses to feed himself and his birds. Birdman offers the couple eggs, which they enjoy –– for the first time.

As they eat, Birdman spins a yarn (or is it true?). He claims to recognize Mather – that’s why when he spotted him through his binoculars he invited him up. Birdman has never met Mather, but he looks exactly like a dear old friend of his, a man named LEONARDO. Birdman says that surely Mather is Leonardo’s grandson –– how else to explain the stunning similarity?

Rachel and Mather are skeptical –– until Birdman shows him an old photo of Leonardo, before the sky blew off. The similarity is truly remarkable.

Birdman, in a shaman-like dialogue, claims that Mather’s arrival here has been pre-ordained. For just recently, a carrier pigeon arrived from Nordenland, to which Leonardo, a wealthy young man before the sky blew off, evacuated as civilization was dying. Rachel and Mather have heard rumors of this place, but until now believe it to be mythical, a sort of Nirvana that doesn’t really exist. Birdman shows the various messages the pigeons have brought: in summary, they claim that the earth’s atmosphere over Nordenland shows rising levels of natural O2, decreasing levels of CO2. Nature herself is responsible. (And our real-life planet earth has a long history of healing itself: returning from ice ages, for example; recovering from the massive meteor strike that killed the dinosaurs and paved the way for mammals to rule the planet; and regional recovery from the massive soot sent into the atmosphere by giant volcanic eruptions.)

Birdman speculates that this pristine air can actually reverse dementia. This is good news on an individual level, of course –– especially for Mather, who’s losing it rapidly –– and also on the larger level of hope for humanity.

Birdman is too old to make the trip –– he’s happy here, anyway, crazy with his crows. But he urges Rachel and Mather to go –– what do they have to lose? Birdman has a map. He also has an old Polaroid camera, still working, and he takes a picture of him with the couple. Photography is a further marvel for Rachel and Mather.

Along with the photo (which will show proof of the couple’s meeting with Birdman), Birdman writes a letter of introduction to Leonardo.

And so Rachel and Mather set off…

-- 30 --

Context:

Of my many collaborations with Drew Smith, this may be my favorite -- and the lead, Birdman, one of my favorite fictional characters. It evolved from my short story of the same name, and over the many months we spitballed back and forth, we gave it varying names, “The Memory Bank” being one. Yes, this is another dystopian work, and it rings a true today as when we wrote it a few years back – perhaps more so, as climate change continues to jeopardize the planet and the life forms that inhabit it (for now, anyway).

And humor me as I open the old writer’s trunk to reveal another screen project, much older than “Since the Sky Blew Off” – a completed full script for “Wishers,” which I completed more than a quarter of a century ago. Less dystopian than pure science fiction, it has flavors of early Spielberg. Herewith the first six pages. As you can see, this is literally from the trunk:

Published on May 18, 2018 03:30

May 17, 2018

#33Stories: Day 17, "Snyder," a screenplay with Drew Smith and Drake Witham

#33Stories

No. 17: “Snyder,” a screenplay with Drew Smith and Drake Witham

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Writers Guild of American registration no. 1184318

Near the beginning of the screenplay:

INT. OFFICE --- NEXT MORNING

LEONARD is back in the rat maze of cubicles, coffee cups and broken dreams. He’s getting an earful from an irate customer, simmering.

LEONARDYes, I understand that you’re frustrated. Well I do think there’s uh, hey I don’t think that language is necessary…

Close up on Leonard as we see his getting red. The caller’s ranting is indistinct except for the phrase “you lousy motherfucker!”

LEONARD That’s Uncalled for. No, NO I’VE SPENT TEN MINUTES LISTENING TO YOUR FEEBLE BRAIN FORM FOUL-MOUTHED INSULTS AND NOW YOU WILL LISTEN TO ME.

LEONARD catches himself. Realizes he’s already gone too far, might as well finish with a bang.

LEONARD (Cont’d) How dare you bring anyone’s mother into this? I will have you know that not only am I not lousy but your mother was quite pleased and the only reason I haven’t been back is that her RATES ARE MUCH TOO HIGH! Good Day, sir.

LEONARD slams the phone down only to see red light blinking, another call is waiting. He sighs and answers.

LEONARDCustomer Service. Can I help you?(beat) Well that’s an interesting insult to open a conversation with a complete stranger. Listen up you MORON, the next time you want take out anger by screaming at someone you don’t know or kick a dog or,or well,, just don’t. Instead walk up to a nearby wall and bang your head repeatedly.I’m NOT FINISHED YET. Bang your head untilyou either pass out or you see enough ofyour own blood that you can finger paintthis message – I’M A RUDE, SELF-IMPORTANT JACKASS! I’ll send you a dictionary to help with the big words.

LEONARD hangs up and hears an applause from his co-workers but doesn’t turn the light is red again.

LEONARDWho wants some customer service now?(beat) Oh I’m fine thank you. Thank you fornot asking, ma’am. May I call you ma’am?Thank you for being just like every other barely literate fool who has called over the past 17 years to dump your problemson us… Hello?

LEONARD looks at the phone. Clearly the woman has hung up.

LEONARDAnd then sometimes this job is easy.

Leonard is largely oblivious to the gathering crowd. SALLY is looking on but so is STELLA, the office busy body, PHIL, the suck-up, MARIA, the tart and WALLACE. He misses the gathering crowd ‘cause he notices that his co-worker FloReese is dealing with another pompous jerk. He also doesn’t see that the whole thing is being filmed.

FLOREESEI can get you a manager, Miss but I’mnot sure why you have…

LEONARDGive me that phone, FloReese.

FloReese pauses. She’s never really liked Leonard but she kinda likes what he’s doing today.

LEONARDFLOREESE!

Before she can give him the phone he grabs it from her.

LEONARDManager’s number? Sure I’ll give it toyou. I’ll give you his home number. Whydon’t you call him in the middle of thenight and see if he cares anymore than Ido. But before you make that call why don’tyou see if you can locate your daughter atthat hour before she repeats your doubtless mistake of filling the world with illegitimate spawn. Oh, you know what we’re running aspecial today on, on advice so I’ve got onemore for you – grab a pen. Start showing somelove for the people around you and maybe they won’t hate you and then you won’t have to beso nasty to everyone you encounter. Believeit or not, we are trying to help. Hold forthe manager’s number and in the meantime whydon’t you apologize to FloReese?

Leonard hands the phone back to FloReese and sees that a crowd has gathered around. Some are shocked, some are in awe and some are squarely in his sights.

STELLAReal professional Leonard.

LEONARDIt’s really professional. Not real. Really.But they probably didn’t teach much grammarat busybody school. For once STOP STICKINGYOUR NOSE IN OTHER PEOPLE’s BUSINESS.

Some of them gasp, a few laugh, notably PHIL, the suck-up.

LEONARDI don’t know what you’re laughing at Phil.You’re better than anyone at sticking you’re little brown nose all the way in. WHO WANTSSOME NOW?

Just then Al the boss walks around the corner.

ALWhat are you serving up Leonard, more ofthe vitriol you’ve been sharing with our customers. You’re unstable, you’re unlikable and you’re unemployable. Get your ass out of here.

LEONARDI’ll be expecting a nice severance. Butsince you’ve come all the way down to thefront lines for the first time in what…sevenyears I’d like to tell you, fearless leaderthat you have all the intelligence andcharisma of a fire hydrant. But I don’t eventhink a dog would want to piss on your sorryass. Good Day, yes I said Good Day, Sir.

LEONARD begins to gather his things, when FloReese motions toward him.

LEONARDSorry about that call, FloReese.

FLOREESENot at all. It was my sister.

LEONARDOh, I’m sooo sorry…

FLOREESEShe needed to hear it. Thank you Leonard.

Leonard walks out and the place erupts in applause.

Context:

Screenwriter Drew Smith and I have worked on many projects together, including the screen version of "King of Hearts" and a long-running collaboration, "The Memory Bank," variously titled "The Memory Bank" and "Since the Sky Blew Off," for my short story on which it is based.

More on "The Memory Bank" in Day 18.

Although we have come close, Drew and I have yet to see any of our collaborations hit the actual screen. We still have hope! But if you know anything about Hollywood, you understand that disappointment and heartache are a part of the game.

In "Snyder," we brought in my old friend Drake Witham, a former newspaper reporter who left the biz to pursue his dream of becoming a stand-up comic, which he did. We wrote "Snyder" in the early days of YouTube, but we had figured out, like many others, the power it would have. And so that is the beginning of the narrative arc of the script: "Loser" Leonard discovers a rare talent for stand-up, and a YouTube clip goes viral, catapulting the man onto the pages of Variety.

I still like this one. Thanks Drake and Drew (sounds like the name of a bad law firm!) for working on "Snyder." I had fun then, and reading it now pleases me still.

Published on May 17, 2018 02:54

May 16, 2018

#33Stories: Day 16, "The Xeno Chronicles"

#33Stories

No. 16: “The Xeno Chornicles: Teo Years on the Frontier of Medicine Inside Harvard’s Transplant Lab””

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in 2005 by PublicAffairs/Perseus

The opening chapter, “Double Knockout,” of “The Xeno Chronicles”:

A twenty-one-pound pig

A cold day was dawning when Dr. David H. Sachs left his home and headed to his Boston laboratory, a few miles distant. He was praying that experimental animal no. 15502 -- a cloned, genetically engineered pig -- had arrived safely overnight from its birthplace in Missouri.

It was Friday, February 7, 2003.

Ordinarily a calm and measured man, Sachs had fretted for weeks over this young animal, whose unusual DNA might help save untold thousands of human lives. He worried about the weather, so frigid that Boston Harbor had iced over and pipes in the animal facility had frozen, fortunately without harm to the stock. He worried that the pig would become sick before getting to Boston. He had decided against transporting it by truck, for a winter storm could prove disastrous -- so then he worried about flying it up. What type of aircraft should they use? Commercial? Charter? Which airport in the congested metropolitan area would be safest?

``Use your best judgment,'' Sachs had told the staff veterinarian he had assigned to bring the pig north. ``Just don't lose this pig!''

An immunologist who trained in surgery, Sachs had distinguished himself in the field of conventional transplantation, in which human organs are used. His lab, the Transplantation Biology Research Center, was a part of Massachusetts General Hospital, where he was on staff. He was a professor at the Harvard Medical School. He belonged to the National Academy of Sciences's Institute of Medicine. He was fluent in four languages. He had written or co-written more than 700 professional papers. Science came as naturally to Sachs as breathing.

One achievement, however, still eluded him. For more than thirty years, Sachs had tried to find a way to get the diseased human body to accept parts from healthy animals.

Xenotransplantation, as cross-species transplantation was called, had the potential to save thousands of people who die every year because of a chronic shortage of human organs. Sachs envisioned a time when patients needing a new heart, liver or kidney would simply have their doctor order one up from the biomedical farm. Children born with defects and older people with all manner of ailment would benefit. Sachs himself was not motivated by money, but xeno could become a multi-billion-dollar business. You couldn't buy or sell a human organ, at least not in America and most countries of the world. But there were no laws in the U.S. against commerce in animal parts, although animal-rights activists and others believed there should be.

Many scientists over many years had tried to achieve what Sachs sought.

So far, the idea remained a dream.

A man of average height, Sachs was on a diet but still carried a few too many pounds, a fact he jokingly acknowledged when describing himself as ``chubby.'' With his full head of graying hair and his jolly face, the image of a Teddy bear came to mind -- an image that was reinforced when he laughed, which was often. Sachs favored button-down shirt, tie, khaki slacks, a rumpled suit jacket, and wingtip shoes. Unless you looked closely, you would not notice that his right foot was larger than his left, a remnant of his childhood when, at the age of 4 1/2, he contracted polio, the scourge of the 1940s. Sachs had spent weeks of his early childhood at Manhattan's Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, an institution on 42nd Street and Lexington whose very name evoked suffering. The doctors said he might never walk again. But he did, perfectly normally.

``It just never seemed possible to me that I wouldn't,'' Sachs said. ``It just seemed to me that I had to get over this problem. I've never had a defeatist attitude toward anything. I always feel that it's just a matter of being able to figure it out, make it work. That's my attitude toward everything.''

But Sachs could not stop the clock. He was past sixty now and increasingly conscious of his mortality.

``Only recently have I started to realize how finite my lifespan is,'' he said. ``Of course I've known that since I could think, but as you get older you realize that nobody lives past 100 and I'll be lucky if I get over eighty. So I don't have a hell of a lot of time left.''

In his darker moments, Sachs worried that he would never achieve his grand ambition. Experimental animal no. 15502 -- a creature small enough to fit into a baby stroller -- might well be the beginning of his last chance…

-- 30 --

READ the hardcover.

“The Xeno Chronicles” marked my return to medical non-fiction, and it was my second book with PublicAffairs – and the first there edited by the brilliant Lisa Kaufman. I dedicated it to “the three most incredible children, and the most incredible granddaughter: Rachel, Katy, Calvin and Isabella. I love you guys!!!” Did, do, and now we have two more youngsters in the family: Rachel’s second child, Olivia, and Katy’s first, Vivienne. Here, here!

Some of the reviews for “The Xeno Chronicles”:

"The xenotransplantation story has the makings of a Hollywood problem-picture blockbuster... Thought-provoking reading."

-- Booklist

A selection of the Scientific American Book Club

One of the three best Health Sciences books of 2005.

-- Library Journal, March 1, 2006.

"Dr. Samuel Johnson had James Boswell, and Dr. Sachs has G. Wayne Miller. The author has written a page-turner with good humor and elan, a memorable account of a fine scientist and his team on the cusp of life-saving research."

-- Boston Globe, Sept. 21, 2005.

"Xenotransplantation has the potential to radically transform medical practice, and Miller notes the financial stake pharmaceutical companies have in this research. But he focuses on the human issues... Miller always keeps readers' attention focused squarely on the hopes being placed on this research."

-- Publishers Weekly, April 11, 2005.

"Miller takes a broad, balanced approach."

-- Chicago Tribune, July 31, 2005.

"If you have any curiosity about how human beings could outfox illness in the 21st century, this is a must read... Miller sketches a vivid portrait of the pioneers in a field of science wracked by ethical issues."

-- Providence Journal, June 5, 2005.

"The writing is fluid and fun, and Miller systematically portrays a smart scientist who's never going to quit trying."

-- Wilson Quarterly, Summer 2005.

"Miller tells the story of this research and its leading figure, David H. Sachs, as he races to finish his controversial experiments before funding runs out."

-- Washington Post, June 12, 2005.

"Miller's flair for a dramatic story and a brilliant cast of characters make this a gripping read."

-- Library Journal, July 2005.

"The xenotransplantation story has the makings of a Hollywood problem-picture blockbuster. Thought-provoking reading."

-- Booklist, June 1, 2005.

"Miller, a staff writer at The Providence Journal,provides a you-are-there narrative of a scientist's attempts to make a breakthrough in the field of organ transplantation."

-- Book News, 2005.

"Miller creates a vivid, personalized account of a controversial arm of biomedical science and delves into the ethics of exploiting animals for the sake of people."

-- Science News, Sept. 10, 2005.

No. 16: “The Xeno Chornicles: Teo Years on the Frontier of Medicine Inside Harvard’s Transplant Lab””

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in 2005 by PublicAffairs/Perseus

The opening chapter, “Double Knockout,” of “The Xeno Chronicles”:

A twenty-one-pound pig

A cold day was dawning when Dr. David H. Sachs left his home and headed to his Boston laboratory, a few miles distant. He was praying that experimental animal no. 15502 -- a cloned, genetically engineered pig -- had arrived safely overnight from its birthplace in Missouri.

It was Friday, February 7, 2003.

Ordinarily a calm and measured man, Sachs had fretted for weeks over this young animal, whose unusual DNA might help save untold thousands of human lives. He worried about the weather, so frigid that Boston Harbor had iced over and pipes in the animal facility had frozen, fortunately without harm to the stock. He worried that the pig would become sick before getting to Boston. He had decided against transporting it by truck, for a winter storm could prove disastrous -- so then he worried about flying it up. What type of aircraft should they use? Commercial? Charter? Which airport in the congested metropolitan area would be safest?

``Use your best judgment,'' Sachs had told the staff veterinarian he had assigned to bring the pig north. ``Just don't lose this pig!''

An immunologist who trained in surgery, Sachs had distinguished himself in the field of conventional transplantation, in which human organs are used. His lab, the Transplantation Biology Research Center, was a part of Massachusetts General Hospital, where he was on staff. He was a professor at the Harvard Medical School. He belonged to the National Academy of Sciences's Institute of Medicine. He was fluent in four languages. He had written or co-written more than 700 professional papers. Science came as naturally to Sachs as breathing.

One achievement, however, still eluded him. For more than thirty years, Sachs had tried to find a way to get the diseased human body to accept parts from healthy animals.

Xenotransplantation, as cross-species transplantation was called, had the potential to save thousands of people who die every year because of a chronic shortage of human organs. Sachs envisioned a time when patients needing a new heart, liver or kidney would simply have their doctor order one up from the biomedical farm. Children born with defects and older people with all manner of ailment would benefit. Sachs himself was not motivated by money, but xeno could become a multi-billion-dollar business. You couldn't buy or sell a human organ, at least not in America and most countries of the world. But there were no laws in the U.S. against commerce in animal parts, although animal-rights activists and others believed there should be.

Many scientists over many years had tried to achieve what Sachs sought.

So far, the idea remained a dream.

A man of average height, Sachs was on a diet but still carried a few too many pounds, a fact he jokingly acknowledged when describing himself as ``chubby.'' With his full head of graying hair and his jolly face, the image of a Teddy bear came to mind -- an image that was reinforced when he laughed, which was often. Sachs favored button-down shirt, tie, khaki slacks, a rumpled suit jacket, and wingtip shoes. Unless you looked closely, you would not notice that his right foot was larger than his left, a remnant of his childhood when, at the age of 4 1/2, he contracted polio, the scourge of the 1940s. Sachs had spent weeks of his early childhood at Manhattan's Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, an institution on 42nd Street and Lexington whose very name evoked suffering. The doctors said he might never walk again. But he did, perfectly normally.

``It just never seemed possible to me that I wouldn't,'' Sachs said. ``It just seemed to me that I had to get over this problem. I've never had a defeatist attitude toward anything. I always feel that it's just a matter of being able to figure it out, make it work. That's my attitude toward everything.''

But Sachs could not stop the clock. He was past sixty now and increasingly conscious of his mortality.

``Only recently have I started to realize how finite my lifespan is,'' he said. ``Of course I've known that since I could think, but as you get older you realize that nobody lives past 100 and I'll be lucky if I get over eighty. So I don't have a hell of a lot of time left.''

In his darker moments, Sachs worried that he would never achieve his grand ambition. Experimental animal no. 15502 -- a creature small enough to fit into a baby stroller -- might well be the beginning of his last chance…

-- 30 --

READ the hardcover.

“The Xeno Chronicles” marked my return to medical non-fiction, and it was my second book with PublicAffairs – and the first there edited by the brilliant Lisa Kaufman. I dedicated it to “the three most incredible children, and the most incredible granddaughter: Rachel, Katy, Calvin and Isabella. I love you guys!!!” Did, do, and now we have two more youngsters in the family: Rachel’s second child, Olivia, and Katy’s first, Vivienne. Here, here!

Some of the reviews for “The Xeno Chronicles”:

"The xenotransplantation story has the makings of a Hollywood problem-picture blockbuster... Thought-provoking reading."

-- Booklist

A selection of the Scientific American Book Club

One of the three best Health Sciences books of 2005.

-- Library Journal, March 1, 2006.

"Dr. Samuel Johnson had James Boswell, and Dr. Sachs has G. Wayne Miller. The author has written a page-turner with good humor and elan, a memorable account of a fine scientist and his team on the cusp of life-saving research."

-- Boston Globe, Sept. 21, 2005.

"Xenotransplantation has the potential to radically transform medical practice, and Miller notes the financial stake pharmaceutical companies have in this research. But he focuses on the human issues... Miller always keeps readers' attention focused squarely on the hopes being placed on this research."

-- Publishers Weekly, April 11, 2005.

"Miller takes a broad, balanced approach."

-- Chicago Tribune, July 31, 2005.

"If you have any curiosity about how human beings could outfox illness in the 21st century, this is a must read... Miller sketches a vivid portrait of the pioneers in a field of science wracked by ethical issues."

-- Providence Journal, June 5, 2005.

"The writing is fluid and fun, and Miller systematically portrays a smart scientist who's never going to quit trying."

-- Wilson Quarterly, Summer 2005.

"Miller tells the story of this research and its leading figure, David H. Sachs, as he races to finish his controversial experiments before funding runs out."

-- Washington Post, June 12, 2005.

"Miller's flair for a dramatic story and a brilliant cast of characters make this a gripping read."

-- Library Journal, July 2005.

"The xenotransplantation story has the makings of a Hollywood problem-picture blockbuster. Thought-provoking reading."

-- Booklist, June 1, 2005.

"Miller, a staff writer at The Providence Journal,provides a you-are-there narrative of a scientist's attempts to make a breakthrough in the field of organ transplantation."

-- Book News, 2005.

"Miller creates a vivid, personalized account of a controversial arm of biomedical science and delves into the ethics of exploiting animals for the sake of people."

-- Science News, Sept. 10, 2005.

Published on May 16, 2018 02:31

May 15, 2018

#33Stories: Day 15, "Men and Speed"

#33StoriesNo. 15: “Men and Speed: A Wild Ride Through NASCAR’s Breakout Season”Context at the end of this excerpt.Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in 2002 by PublicAffairs/Perseus

pp. 1 to 4, Chapter One: The Guru and the Kid

On the afternoon of Saturday, July 8, 2000, a man who looked barely old enough to drive climbed into a car designed to race at almost a third the speed of sound. Kurt Busch and thirty-three other drivers fired up their engines. Bone-rattling noise rocked New Hampshire International Speedway and the air smelled suddenly burnt.

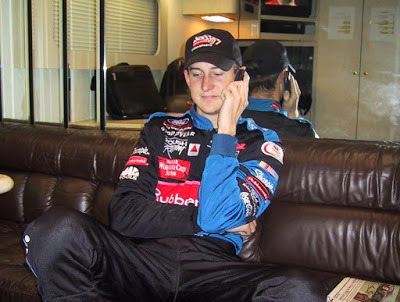

From the grandstands, the luxury boxes, and atop the campers and motor homes lining the hill behind the backstretch of the mile-long track, a sellout crowd of some ninety thousand fans watched. Most were getting their first glimpse of Busch, a tall, slender, twenty-one-year-old with a boyish face who only eight months before had earned his living fixing broken pipes. If they knew anything about the kid, it was that he drove ferociously and with uncommon skill -- and that his talent, while still raw, had earned him the backing of one of the most powerful men in American motorsports.

Polite and impeccably mannered off-track, and gifted with an easy humor, Busch became transformed when he took the wheel of a racecar. He drove at the edge – out in that rarefied zone between fearlessness and craziness, the place where speed kings thrive. No track intimidated Busch. No race seemed unwinnable at the green flag, regardless of where he started.

He was starting in fifth place today in this NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series race -- behind the series leader and three veterans, two of whom had begun their careers before he was born. As Busch fastened his belts, checked his gauges, and otherwise connected with his machine, he reviewed his strategy, which involved conserving his tires, which would give him track advantage, and a commitment to racing clean. Busch would go eyeball-to-eyeball with an opponent if need be -- would crawl to within a quarter inch of someone's bumper to bully him out of the way, if need be -- but he was determined to avoid contact.

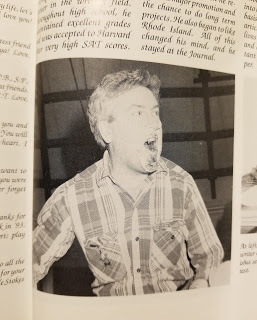

Kurt Busch in 2001. Three years later, he would be champion.Contact preoccupied everyone that July afternoon in Loudon, a small town in central New Hampshire. NASCAR racing is among the most violent of the motorsports: virtually no race passes without cars wrecking, often in fiery collisions that thrill fans. Protective gear, custom seats and steel caging ordinarily protect drivers -- but concrete and speed can be lethal. Just twenty-six hours earlier, popular driver Kenny Irwin Jr. had died while practicing at this track, whose nickname, The Magic Mile, now seemed a cruel joke. The throttle on his 720-horsepower car stuck at full speed, rendering meaningful braking impossible, and Irwin hit the Turn Three wall head-on at 160 miles per hour. The impact destroyed Irwin's vehicle and fractured the base of his skull, destroying his brain. A virtually identical crash on Turn Three had killed another well-known young driver, Adam Petty, grandson of stock car legend Richard Petty, only two months earlier.

Kurt Busch in 2001. Three years later, he would be champion.Contact preoccupied everyone that July afternoon in Loudon, a small town in central New Hampshire. NASCAR racing is among the most violent of the motorsports: virtually no race passes without cars wrecking, often in fiery collisions that thrill fans. Protective gear, custom seats and steel caging ordinarily protect drivers -- but concrete and speed can be lethal. Just twenty-six hours earlier, popular driver Kenny Irwin Jr. had died while practicing at this track, whose nickname, The Magic Mile, now seemed a cruel joke. The throttle on his 720-horsepower car stuck at full speed, rendering meaningful braking impossible, and Irwin hit the Turn Three wall head-on at 160 miles per hour. The impact destroyed Irwin's vehicle and fractured the base of his skull, destroying his brain. A virtually identical crash on Turn Three had killed another well-known young driver, Adam Petty, grandson of stock car legend Richard Petty, only two months earlier.Busch and his competitors circled the track behind the pace car, swerving in and out of file like hornets startled from a nest -- a maneuver that warms tires, improving grip. The field took the green flag and now the noise, fueled by 110-octane gas and the absence of mufflers, exceeded a jet on takeoff. For the moment, Busch pushed Turn Three from his mind. The race known as the thatlook.com 200 had begun. Half a million dollars was at stake.

Standing with Busch's crew on pit road, owner Jack Roush watched his newest protégé blister the mile-long oval.

A short man who favored button-down shirts, cuffed khaki pants and a straw fedora -- an outfit that made him an eccentric in a world of oil and grease -- Roush had built the largest motorsports operation in America. But Roush, fifty-eight, was renowned for more than his racing achievements. Bearer of a master's degree in mathematics, he had taught college physics. He had founded and remained chairman of a $250 million engineering firm, Roush Industries, of which Roush Racing was a subsidiary. He enjoyed piloting his own corporate jet, and he was about to purchase three 727 airliners to move his race teams around the country -- -but he felt deeper passion for his P-51 Mustang, a World War II fighter plane that he’d bought, restored, and now used to perform aerobatics, frequently with someone he wanted to thrill riding expectantly (if not nervously) in back.

Before one such adventure, Roush talked to the home office on his cell phone while conducting a pre-flight inspection of his plane, which was parked at an airport near his racecar-building shops in Concord, North Carolina, just outside of Charlotte. Freshly painted in its original colors and sporting its original name -- Old Crow, bestowed by Bud Anderson, the war hero who'd flown it in combat -- the P-51 sparkled in the midday sun. Roush shed his fedora and pulled a flight suit over his shirt and pants, then removed two parachutes from the trunk of his Lincoln and handed one to his passenger.

"Only two reasons you'd need it," said Roush. "One is if we catch fire. The other is a mid-air collision."

Jack Roush's passenger that day. After explaining the basics of operation as he understood them, Roush noted that he had never used a parachute. "I don't believe in practicing for something you only do once," he said, grinning.

Jack Roush's passenger that day. After explaining the basics of operation as he understood them, Roush noted that he had never used a parachute. "I don't believe in practicing for something you only do once," he said, grinning.The plane rattled and shook as it sped down the runway, and, after a final shudder, lifted like an eagle into the blue. Roush cruised northwest, turning the plane upside-down as he passed over the business headquarters of Roush Racing, where the mahogany walls gleam and the employees wear suits. A few moments later, having determined that he had the airspace all to himself, Roush executed maneuvers that he described in an animated monologue over the plane's intercom: a barrel roll, an aileron roll, a four-point victory roll, an enormous loop. At this point, having repeatedly achieved five Gs, a force that can flood the body with adrenaline, Roush leveled off and headed toward a friend's farm, which he buzzed at treetop level. Only then did Roush confide that he'd never taken lessons in aerobatics, but had figured things out himself.

But automobiles, not aircraft, had remained Roush's foremost obsession since childhood, when he got his first taste of speed…

Context:

NASCAR. Really?

Yes, really.

Every author needs to write at least one sports book, right?

Well, maybe not. But I wanted to, and after some thought, settled on motorsports, whose speed and ultimate risk-taking participants fascinated me. I also like fast cars (and would return to them, in a later book about a much earlier era, “Car Crazy,” coming on Day 30).

Through a combination of luck, determination and the good fortune to meet the great Jamie Rodway, who worked for Roush, I succeeded in winning Jack Roush’s permission to be embedded for an entire season with his NASCAR team of veterans Mark Martin and Jeff Burton, and rookie Kurt Busch and young driver Matt Kenseth, both of whom would later become champions.

So I travelled the country during the 2001 Winston Cup (now Monster Energy) season – a season that began with the death of legendary seven-time champion Dale Earnhardt at Daytona. I said good morning to him before that race, and snapped a picture…

Dale Earnhardt, befroe the race at Daytona in which he died.Quite a year – and with tracks like Talladega, in Alabama, quite a number of places I otherwise likely would never have visited. I drove a bit myself, too: somewhat recklessly and with my first taste of pure speed in one of Jack’s Stage 3 Mustang convertible that hits sixty in 4.3 seconds and tops out at some 170 miles per hour. That day-long ride, from Knoxville, Tennessee, and on into Lexington Kentucky, with Jack in the passenger seat, remains etched in memory. What a day. I should note that Jack never offered to hand me the wheel again: hitting 120 mph during rush hour on a highway into Lexington was not, shall we say, law-abiding. But damn, it felt good.

Dale Earnhardt, befroe the race at Daytona in which he died.Quite a year – and with tracks like Talladega, in Alabama, quite a number of places I otherwise likely would never have visited. I drove a bit myself, too: somewhat recklessly and with my first taste of pure speed in one of Jack’s Stage 3 Mustang convertible that hits sixty in 4.3 seconds and tops out at some 170 miles per hour. That day-long ride, from Knoxville, Tennessee, and on into Lexington Kentucky, with Jack in the passenger seat, remains etched in memory. What a day. I should note that Jack never offered to hand me the wheel again: hitting 120 mph during rush hour on a highway into Lexington was not, shall we say, law-abiding. But damn, it felt good.

“Men and Speed” was my first book for PublicAffairs, and editor Paul Golob took a workable manuscript and elevated it into a critically acclaimed book. PublicAffairs would later publish two more of my books -- “The Xeno Chronicles,” coming on Day 16 of #33Stories, and “Car Crazy” –and Lisa Kaufman would edit them. Thanks again, Paul and Lisa, and thanks publisher Clive Priddle.

Some of the reviews for “Men and Speed”:

A BOOK-OF-THE-MONTH CLUB SELECTION

"Eye-opening and provocative...revealing the humanity of these daredevils may be Miller's greatest accomplishment." -- Daytona Beach News-Journal, June 29, 2003.

"One of the strongest narrative sports books since John Feinstein’s classic A Season on the Brink." -- Editorial Board, BOMC, July 30, 2002.

"Thrilling." -- Boston Globe, July 3, 2002.

"An edge-of-your-seat read." -- Providence Journal, June 2, 2002.

"Recommended." -- Library Journal, June 1, 2002.

"Miller's insights into the economic, technological and emotional workings of a top team are fresh and valuable." -- New York Times, May 26, 2002.

"Mesmerizing... The moving stories of bravery, winning, and defeat, and the exploration of the addictive nature of speed make this a must-read: not only for race fans, but for non-enthusiasts who will finally understand once and for all what all the fuss is about." -- Writers Write, The Internet Writing Journal, May 2, 2002.

"A no-B.S. account of a season in NASCAR. Enjoyable, straight-ahead and smart." -- Paul Newman, actor and racer.

"If you're a racing fan and you've often wondered when you look down on pit road or in the garage area what those guys are talking about -- here's your chance to find out. MEN AND SPEED is awesome." -- Benny Parsons, Winston Cup champion and NBC broadcaster.

"New people with new perspectives, new ideas, have joined the throngs at America's superspeedways to take new, fresh looks at NASCAR, the fastest-growing sport on the commercial radar screen. Thankfully, G. Wayne Miller is one of them. He latched a ride through the 2001 season with the Roush Racing team and the result, MEN AND SPEED, tells the late-comers what the noise is all about. Sit down. Buckle up. Take the 288-page ride and kiss the beauty queen at the end. And enjoy." -- Leigh Montville, former Sports Illustrated writer, and author of AT THE ALTAR OF SPEED.

"If you want to learn about NASCAR, talk to the best, Jack Roush! If you want to learn about faster speeds, talk to Jack again! I have flown with Jack in his P-51 Mustang at more than 400 mph. He is as good as they come. And writer Wayne Miller captures the essence of Jack, NASCAR, and speed in his book MEN AND SPEED." -- Gen. Chuck Yeager, subject of Tom Wolfe's THE RIGHT STUFF.

"A title race fans will be talking about for years to come." -- Bob Schaller, StockCarCity.

Praise for Miller's last book, KING OF HEARTS, about another group of daring risk-takers:

"Breathless, spirited and dramatic." -- Mark Bowden, author of Black Hawk Down.

"Gripping." -- Los Angeles Times.

"You'll find yourself surfacing every few chapters to remind yourself it's nonfiction." -- amazon.com

Published on May 15, 2018 02:55

May 14, 2018

#33Stories: Day 14, "My Adult Life"

#33Stories

No. 14: “My Adult Life”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Begun in 1994, completed 2000, never published.

MY ADULT LIFEA novel in 19 chapters

© Copyright 2000 G. Wayne Miller

Chapter Seventeen.

Dad had retired to a house in Buck's Harbor, twenty minutes out of Blue Hill on Eggemoggin Reach. It was across the road from the water: a traditional white Cape with an incongruous picture window so the previous owner, a summertime deacon at Saint Luke's, could keep an eye on his boat. The deacon had left Sea Watch, as the place was known, to Dad in his will. Dad had lived there a decade now. I'd visited only twice.

I knocked and my father opened the door.

``Hello, son,'' he said. He sounded as if he'd been expecting me. I wasn't sure I liked that.

``Hello, Dad.''

``Come in,'' he said. A fire burned in the fireplace and I smelled a roast in the oven. Dad hung my coat and I followed him into the kitchen.

``Hungry?'' he said. ``I was just about to have my dinner.''

``No thanks,'' I said.

``I hope you won't consider me rude if I eat.''

``Not at all

.''

``You reach my age,'' he said with a smile, ``and the noon meal takes on new meaning. Can I get you coffee?''

``Coffee would be fine.''

Dad set the table and served. He moved slower than the last time I'd seen him, when he visited Marblehead last spring. He'd suffered a minor stroke over the summer, an event he shared with me only after he was out of the hospital, and you could see it was still affecting his coordination.

``Let me help you,'' I said when he had trouble removing the roast -- it was veal -- from the oven.

``No need to,'' he said, ``I manage just fine.''

Dad made gravy, and finished the cream sauce for his baby onions, and zapped a pan of sweet potatoes in butter and maple syrup in the microwave.

``All that fat's bad for the heart,'' I said.

``Nixon and Johnson were bad for the heart,'' Dad said with a smile. ``A little cholesterol is nothing by comparison.''

I remembered all those Sunday afternoons, the Pax Universum creeps making themselves at home while Dad fussed in the kitchen with his veal, or turkey, or leg of lamb, or ham. Dad would say grace, and over dinner, he'd kick off discussion of one of their pet issues. The topic often was war, but not always. Dad had been first in his class at the Harvard Divinity School, and he could expound on Thomas Aquinas, Kierkegaard, More, Fox, a bunch of other philosophers and theologians I steered clear of in college. His peacenik friends couldn't get enough, and after Mom died, when there was no one to move things along, there were Sundays Dad's sessions went late into the night. I'd come back from Sally's or Bud's, and they'd still be there, drinking decaffeinated coffee and going around and around, as if they really did believe a bunch of do-gooders from small-town Maine could change the world.

``I suppose I needn't ask how you are,'' Dad said when he was seated. ``You can't pick up a paper or turn on the boob tube these days without seeing something about you.''

``It's been an experience,'' I said.

``You know what my first reaction was?''

``I won't even guess.''

``I thought: I haven't seen that bottom since his diaper days!'' He laughed, and I couldn't help laughing, too. I'd forgotten how funny my father could be, when he was in the mood.

``Seriously,'' he went on, ``my first thought was: My son's not a murderer. That's what I told the officers who came by.''

``When were they here?''

``Two days ago. I refused to answer any of their questions. `You'll need a judge's order before I say another word,' I told them. Turned out not to be necessary, judging by this morning's headlines.'' Dad rose. ``Ice cream?'' he said. He'd barely touched his dinner. ``I've got Ben and Jerry's.''

``No thanks.''

``You should eat something. Stress is not good on an empty stomach. The acid eats the lining away.''

``I appreciate the advice,'' I said, ``but my appetite's had a mind of its own lately.''

Dad cleared the table and rinsed the dishes and I thought of the dishwasher I'd offered to get him and the wide-screen TV and satellite dish and VCR and everything else. He'd refused it all.

``I was up in the attic a little while ago,'' he said, ``poking around for the manger scene. I happened onto your train set. Do you remember it?''

``Of course I do.''

``It's a Lionel. Still runs -- I know, because I tested it. I thought Timmy might like it.''

``I'm surprised you saved it,'' I said.

He paused, and in that deep voice of his said: ``I should have saved more.''

I knew what he was referring to -- my glove and bat, the posters of Tony C., my baseball magazines and Red Sox programs. He threw everything out during a sudden fury in the spring of 1968, when I was hounding him to get back into ball -- everything but my scrapbook, spared because I'd left it at Sally's. I know how cruel Dad's reaction sounds, and the truth is, it was cruel. Dad was never angrier, before or after -- never close. Something snapped and he became someone else, a raging monster who terrified me, until my anger set in. I never forgave him, despite his apologies and what he did the very next day, which was go out and buy replacements for everything. Thirty years, and I was still pissed.

``I was terribly wrong, you know,'' Dad said.

I shrugged. ``We all make mistakes.''

``Some far more grievous than others,'' Dad said. ``Is it too late to apologize?''

I didn't know if he'd forgotten how often he already had, or if maybe he believed an apology was mandatory whenever the subject came up.

``No,'' I said, ``it's not too late.''

``I'm sorry.''

``We were both different then.''

``I wish I could do it over.''

``You know the bitch of it?'' I said. ``You can't.'' I didn't intend it as a cheap shot -- I was thinking of Sally, and me, and my son.

``No,'' Dad said, ``but it's never too late to seek forgiveness. Or to forgive.''

I didn't reply. I was certain Dad was going to quote Scripture, but he didn't. I wondered if his memory was failing, or if he only wanted to move along.

The dishes were done. We went into the living room and Dad threw a stovelength onto the fire and went to the china cabinet for a bottle of brandy I didn't know he kept. I could see the harbor through the picture window, barely. The storm was settling in for real now and no one was on the water. I looked at Dad's desk, cluttered with large-type books, receipts and cancelled checks, many to charitable organizations and the Episcopal Church. ``Almost tax time,'' Dad said, and I remembered when I was 13, how he'd been arrested for withholding that portion of federal taxes he calculated went to Vietnam. Only the diocesan lawyer's intervention had gotten him out of jail, after a highly publicized weekend during which, not for the first time, I wanted to run away and never return.

Dad set the brandy and two glasses down.

``Care for one?'' he said. ``I'm not sure it's the best thing on an empty stomach. Nor am I sure it's the worst.''

``Why not,'' I said.

``Mama would have liked this view. There isn't a prettier spot on the coast of Maine. She loved the water, your mother did. She always said it put her at peace. Do you remember?''

``How could I forget?''

``It's thirty-two years next Christmas,'' Dad said. ``Hard to imagine you could miss someone so much after so long. The choir sang at service this morning. When I closed my eyes, I could almost hear her voice. Do you remember our Christmas days?''

``Like yesterday.''

``How I cooked while she played her beloved piano?''

``I visited her grave this morning,'' I said.

``Did you see my wreath?''

``Yes.''

``Thank God. There's been a terrible problem with vandals lately. I'd hate for Mama to be without her wreath on Christmas.''

My eye traveled to Mom's piano: an ancient Kimball upright that had been handed down from her grandmother. Mom always dreamed of owning a baby grand, but she never complained that circumstances did not allow her one. What she did was put a pickle jar on the mantel and squirrel away spare change, pennies and nickles, mostly, for her ``Steinway Fund,'' as she called it. She died before it was full. Dad used what was there to buy her tombstone.

We sat in silence then, for I don't know how long. I finished my brandy and Dad his and he poured us another. We'd never shared a drink before, never mind two.

``Go on,'' he urged, ``it'll fortify you.''

``For what?''

``For climbing Blue Hill.''

I thought he must have been kidding, or in the beginning stages of Alzheimer's, or drunk. But to my knowledge, Dad had never been drunk, and he wasn't acting it now. He didn't sound the least bit senile. He sounded resolute, as if he'd pondered this a very long time. And there was no mistaking his eyes. They were as steely and defiant as the day IRS agents led him out of Saint Luke's in handcuffs while a photographer for the Daily News snapped away.

``You're kidding,'' I said.

``No,'' he said, ``I'm serious.''

``It's a blizzard out there.''

``City living's spoiling you,'' Dad said, smiling. ``What this is is a good old Downeast snowstorm, no more, no less. Now, I intend to climb Blue Hill. If you won't accompany me -- well, I guess I'll have no choice but to go it alone.''

****

We parked at the base of the mountain. Dad struggled leaving the car and I doubted he'd have been able to get out if I hadn't been there. And I thought, only half in jest: Where is Officer Bill when you need him? He'd put a stop to this, right quick.

``This is worse than when we left the house,'' I said as Dad got his balance.

``Maybe to a city slicker.''

``This is crazy.''

``You've more than made your point,'' Dad said, stern for the first time. ``Now let's go -- the day's getting away from us. Don't lock your doors, I'm afraid the locks will freeze.''

We made respectable progress the first few hundred yards, a stretch that is gently sloped. Dad walked unassisted and the pines surrounding us broke the wind and the snow hadn't drifted much, was only a smooth three or four inches deep. We nipped from a flask Dad had filled with his brandy and we were determined in our silence. It was one-thirty on the kind of wintry afternoon night is impatient to fall.

A bit further, we hit a deadfall. Dad tried getting over it by himself, but it was too much -- even he conceded that after a clumsy try that left him sputtering. I straddled the trunk and as Dad swung his body over, I bore his weight. He was thinner than I remembered and I thought, although it was probably only my imagination, that I could feel the brittleness of his bones. ``Damn arthritis,'' he said, then quickly added: ``Don't take that to mean I want to turn back. This is actually easier than I expected.''

A bit further still, we were on an open stretch of mountain. The wind had piled the snow to more than two feet in places and knocked down a row of pines. A ranger would have had trouble getting through.

``I don't know, Dad,'' I said.

``It gets easier past here,'' he declared.

``How do you know?''

``The Big Guy told me,'' Dad said. I grinned, but he didn't; he really meant it. ``Let's take a five-minute breather,'' he went on, ``then give it all we've got. We'll make the top by three.''

We took shelter behind a boulder. Dad drank deeply from his flask. I wanted to tell him that alcohol and sub-freezing temperatures were a deadly mix, but he'd had his fill of my observations. His face was flush, whether from effort or wind or both I could not tell, but I didn't mention that, either. I didn't tell him how worried I was that his gloves, and mine, were soaked. I listened to the wind and it sounded like the wildcats I always imagined awaited us on our family climbs more than three decades ago. The snow was so heavy I did not notice, until Dad was set to push off again, that just beyond this boulder was the path leading to Mom's grandfather's blueberry field.

I lost my grip bringing Dad over the last deadfall and he surely would have broken his hip if the drift hadn't cushioned his fall. I said nothing and neither did Dad, but his face showed pain. He put his arm around my waist and we hobbled on, under a canopy of pines that was strangely still and unblanketed with snow. Ten minutes more, we reached the summit.

``After all I've given Him,'' Dad said, dead-seriously, ``the Big Guy owed me.''

There is a firetower at the top of Blue Hill and a ranger's hut and, on good days, the finest coastal vista south of Bar Harbor. We found the leeward side of the hut and I eased Dad down. His lungs sounded like Timmy's, or Mom's on her final climb. Brandy brought him around. His breathing returned to normal and a satisfied look crossed his face. I wonder if he really would have attempted this without me, I thought, but didn't ask. I waited for him to speak and hoped it would be soon, for afternoon was starting to surrender to dusk.

``This was Mama's favorite spot in this world,'' he finally said -- like I didn't know. ``I think she really believed on a clear day, you could see forever.''

``You just about can,'' I said.

``Our first kiss was here,'' Dad said, ``on a day like that. I was still in divinity school.''

Dad had never shared this with me and although I wouldn't have stopped him, I didn't want him to go on. He didn't. His eyes grew distant and I could see he came here regularly in his mind.

``You were the apple of her eye,'' he said. ``I was always afraid she'd spoil you, but she'd have none of it. `It's impossible to spoil those you love,' she used to say. It was the only issue we ever had words over. The only one.''

``You did what you thought was right,'' I said.

``No,'' he said, ``I was a coward.''

``Coward? You went to jail for your beliefs.''

``Those were easy beliefs -- that senseless killing and wars are wrong. Only the Nixons and Johnsons of the world don't see that. My cowardice was with you. I wanted control.''

``You were protecting me.''

``No,'' Dad said, ``I was smothering you. Long after it was time, I wouldn't let go.''

``I was a brat,'' I said. ``I probably would have been with Mom, too, if she'd lived.''

``You had the most powerful imagination,'' Dad said. ``So unlike me. I was afraid of it. Instead of encouraging you, I tried to rein you in. That was wrong. What was more wrong was thinking I could live my dreams through you.''

I remembered the first anniversary of Mom's death. The bishop came to Saint Luke's to concelebrate her service, and afterwards, Dad hosted a reception. He and the bishop disappeared for a spell and I happened on them, alone in the vestibule. The bishop was tearing into Dad for his anti-war activities -- how the publicity was hurting collections and bringing dishonor to the Presiding Bishop and Executive Council. ``If you want a future,'' the bishop said, ``the shit stops now.'' I almost fainted, hearing a bishop talk like that. ``I can't,'' my father said. ``The war is wrong.''

And the bishop said: ``You do understand the Council has very high hopes for you.''

And Dad said: ``I have to do what's right.''

And the bishop declared: ``Then so be it. I hope you like it here.''

Only much later would I understand what had slipped away, forever, from my father that day.

What detached from him became affixed to me, however wishfully, until after I'd left for college. I would receive my doctoral degree in divinity and be ordained in the Episcopal faith. I would not be content with a small-town parish, but would take an assignment in a city. I would climb the church hierarchy, using my growing influence for social causes: working to end poverty, racism, hunger. I would be savvier than Dad was, more diplomatic, and I would make it to bishop, but I wouldn't be satisfied there. The longer my father protested Vietnam the more he became convinced change on the big issues could come only from Washington. And so one day I would be a Senator, even if it meant leaving the priesthood, and I would chair powerful committees and my words would move mountains. Dad never spelled this scenario out so definitively, but the gist of it became abundantly clear over time. It didn't seem to matter that there was an inverse correlation between his desires and mine -- that the harder he pushed, the more I ran.

``I've been doing all the talking,'' Dad said. ``It's your turn now.''

``I guess I don't have much to say.''

``Please,'' Dad said. ``I didn't drag us up here in a blizzard for one of my sermons.''

We laughed. ``So it is a blizzard!'' I said.

``Maybe a little one.''

``Really, I think you've said it all.''

``I know you too well to believe that,'' my father said.

I reflected a moment and said: ``Okay. You want to know the biggest thing?''

``Hollywood.''

``No,'' I said, ``baseball.''

``That would have been my second guess.''

``You were mean.''

``That wasn't my intent.''

``And not just mean -- destructive and mean.''

``That was the last thing I intended. I was thinking only of you. Kids get badly hurt -- even die -- every year in baseball.''

``And a thousand times more get hurt crossing the street.'' I was getting angry. ``What kind of logic is that?''

``I didn't say it was logical,'' my father said softly. ``I've already conceded I was over-protective.''

``Bullshit,'' I said. ``You were jealous.''

``Of my own son?'' He was incredulous.

``You didn't make it in baseball and so you weren't going to let me.''

``You're dead wrong,'' Dad said. ``Nothing ever made me prouder than watching you play.''

``Well, it doesn't matter now,'' I said.

``I'm sorry, Mark. I wish I could change how you feel. But I'm giving it to you straight.''

The last light was draining from the sky and the wind had picked up another notch. I figured we had five minutes, ten at most, before we had to start down or face true peril.

``I visited another grave this morning,'' I said. ``Sally took me. Sally Martin.''

``She said me she might.''

``She told you?''

``Yes. In the confessional. I've known about Jake since before he was born.''

I was stunned. I still had the capacity for that.

``How come you didn't tell me?'' I asked.

``I wanted to, sorely -- but I had my vows. And Sally was explicit that if anyone shared her secret, it be her. It's been a heavy burden for me to carry so long. Far heavier, of course, on Sally. Except for her parents and cousin and the undertaker, I'm not sure who, if anyone, even knows Jake existed. Sally is a very strong woman. Stubborn, but strong.''

``I'll never get over it,'' I said.

``No moral being could.''

``I would've come back immediately if I'd known. Sally doesn't believe me, but it's true. I'm not saying I would've married her -- I mean, maybe I would have, I don't know. But I think of him, the things we could've done...'' I trailed off, my thoughts scattering with the wind.

``I suspect you blame yourself in some way,'' my father said. ``You shouldn't. The Lord gave us Jake and the Lord took him, for reasons known best to Him. As I've said all too many times, the Big Guy can work in strange and mysterious ways.''

``Was he christened?'' I asked.

``Yes. By me, in a chapel in Bangor.''

``So he's happy now.''

``And will be for all eternity -- he's at the Lord's side. Does that help, even a little?''

``Yes,'' I said.

``He was the image of you.''

``Do you think he would have liked me?''

``He would've liked the person I'm talking to now.''

In the movie version of my adult life, of course, this is where Dad would have hugged me. Tears in my eyes, I would have accepted his embrace, and the words would have rushed out of us, words of forgiveness and acceptance, a blessing on us both. But my father said nothing. We did not hug.

``Do you know about Timmy, too?'' I finally said.

It was the most unexpected development of our marriage, how close Ruth had grown to Dad -- although, the better you knew Syd, the more you understood. Ruth was the one who made sure my father visited Marblehead every spring. She was the one who kept asking him to live with us. I don't want to imagine how far my father and I might have drifted apart without Ruth.

Dad nodded.

``You've never mentioned that, either.''

``There's been no need to,'' he said. ``You're a wonderful father. There's not a single thing I'd change.''

``You're mocking me.''

``I'm as serious as I've ever been.''

``Not even all the toys and the ballfield and the pool?''

``Not even all the toys and the ballfield and the pool. Ruth is a fortunate woman. And you are a fortunate man.''

``How could I have forgotten?''

We both laughed at that -- crazy, fool's laughter the storm swiftly carried away. There was much I felt compelled to tell my father now, but it was almost dark; even if we started down immediately, our descent would be treacherous.

``We should do this more often,'' my father said. He was grinning.

``Maybe next time in a hurricane,'' I said, and we laughed.

I helped Dad to his feet, but he didn't start off immediately. He drew my attention to a heart and arrow carved into the hut. My parents' initials were faded, but legible.

``Forty-nine years they've lasted,'' Dad said. ``I don't know what I'd do if the Park Service replaced the hut.''

``I'd haul you up here to carve them again.''

Dad reflected a moment. ``Mama would be proud of you,'' he said, and while I didn't agree, I kept my objections to myself.

****

Carolers were moving through downtown Blue Hill when we arrived and Dad identified them as the Saint Luke's choir. ``You were in that choir,'' he said. ``Sally, too.''

``I remember.''

``They're singing at Saint Luke's for the Christmas Eve concert,'' Dad said. ``Would you care to go?''

``Not this year,'' I said. ``I have some important matters to attend to.''

``Then stop here,'' Dad said in front of Merril & Hinckley, ``but keep that heater running, my bones are still freezing.'' I helped him out of the car and he went in -- alone, at his insistence.

When he returned, he handed me an envelope with Ticketron labeling. ``Sorry it's not wrapped,'' he said.

The envelope had three tickets to a Red Sox-Yankees game in June. They were bleacher seats.

``Our favorite homestand,'' I said.

``How long since we've been?''

``Twenty-five years, at least.''

``Does Timmy hate the Yankees as much as us?''

``More,'' I said. ``It must run in the family.''

Suddenly, my father was crestfallen. ``Stupid me,'' he said.

``What?''

``I forgot you have season tickets.''

``Not anymore,'' I said. ``I'm getting rid of them.''

``Really? Why?''

``Too expensive,'' I lied.

Dad brightened: ``Well, merry Christmas, son.''

``Merry Christmas, Dad.''

-- 30 –

Context:

I began writing “My Adult Life” in the late 1990s, during the dot.com era, as the internet world was transitioning from dial-up to fiber optic, the world we know today. Virtual reality was leaving the labs for the cineplex and home, and video games were advancing from Pong to Xbox. Like so many others, I was fascinated by and pondered how the internet would continue to transform modern life. We seemed to be accelerating to warp speed.

We also, as a culture, were becoming entranced with ourselves. The term “selfie” was yet to be coined (that apparently was in 2002), but with the rising popularity of the digital camera, folks were increasingly taking picture of… themselves. That was nothing new – since the advent of photography, in the 1800s, self-portraits were common – but digitalia made it so much easier. Social media as we know it today was about to dawn and narcissism, recognized since antiquity, was about to pervade the land.

Sound familiar?

So, yes, “My Adult Life” was prescient. In key respects, it rings as true today as in 2000, when I finished it.

But that is only the cultural backdrop to this novel. Beginning as parody and finishing as parable, “My Adult Life” is an exploration of fidelity, family and the power of memory and pull of the past. It speaks to an era, but more so, by the end, to honor and truth.

And it is set in Massachusetts and Maine.

SO, what happened to "My Adult Life"?