G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 13

January 14, 2019

Story in the Public Square TV and Radio marks second-year anniversary

Two years ago today, on January 14, 2017, Story in the Public Square debuted. The first broadcast of our weekly show was with the audio version, on SiriusXM Satellite Radio – the popular P.O.T.U.S. (Politics of the United States), channel 124.

The TV debut, on Rhode Island PBS, was the next day, a Sunday, at 11 a.m., which remains our time slot today in the southeastern New England market (rebroadcasts Thursdays at 7:30 p.m.).

Since our debut, Story in the Public Square has won a Telly Award and, starting in September 2018, gone national -- now seen coast-to-coast in 22 of the top 25 U.S. markets and 76 percent of all U.S. markets. And co-host Jim Ludes and I have brought more than 100 storytellers to our audiences.

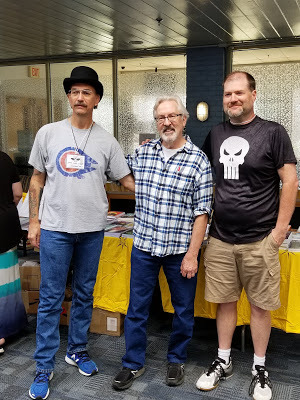

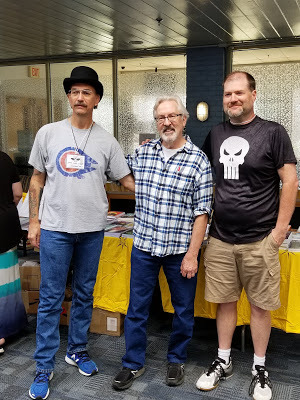

Story cast and Crew during recent taping of guests Alice Robb, center, and Mike Stanton, right of Robb.They come from the worlds of journalism, film, photography, academia, poetry, art, books, politics, medicine and more. Many have won national awards. All have informed and educated and many have also entertained -- and all have met our only request, to learn about their creative processes and how their stories impact public understanding and policy in America and the world. Jim and I listen more than talk. Story is about our guests and important issues, not us.

Story cast and Crew during recent taping of guests Alice Robb, center, and Mike Stanton, right of Robb.They come from the worlds of journalism, film, photography, academia, poetry, art, books, politics, medicine and more. Many have won national awards. All have informed and educated and many have also entertained -- and all have met our only request, to learn about their creative processes and how their stories impact public understanding and policy in America and the world. Jim and I listen more than talk. Story is about our guests and important issues, not us.

The roots of Story in the Public Square date to February 2012, when Jim and I met for coffee, which began a conversation that led to the founding of the Story program at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center, which Jim heads. A partnership with The Providence Journal, where I am a staff writer, was formed and remains to this day.

The old saw holds that it takes a village -- but it’s true, and our guests belong to that village; without them, we’d be little more than a couple more talking heads yammering about whatever. And there are many others who have helped build our show. An anniversary is an appropriate time to acknowledge them.

Let me start with The Providence Journal, with publisher Janet Hasson and Executive Editor Alan Rosenberg. Thanks, Janet and Alan. Also, Jeff Beland, Marketing and Audience Development Director. And at GateHouse Media, our parent company, thanks to Lori Catron, Vice President Marketing Strategy & Communications.

At Salve, President Sister Jane Gerety has been supportive from the start. Teresa Haas, Office & Events Manager at the Pell Center, keeps the trains rolling on time – almost literally, as many of our guests come up from New York. Communications chief Erin Demers masterfully handles our social media, press and more. She succeeds Gianna Gerace and before Gianna, Mia Lupo, who also once held those responsibilities.

At our flagship station, Rhode Island PBS, so many! David W. Piccerelli, Kim Keough, Scott Saracen, Lori Sullivan, Cherie O’Rourke, Nick Moraites, Mark Smith, Joe Brathwaite, Andrew Vanasse, Lynn Nardone Young are among them. And our set designer, John Methia. And two people no longer at RIPBS who were instrumental in getting us off the ground: Dave Marseglia and Kathryn Larsen, Senior Director of Broadcasting for Radio and Television at WNED in Buffalo.

The broadcast beginnings of Story in the Public Square can be traced to the nine episodes Jim and I did as guest hosts in 2016 for White House Chronicle, hosted by Llewellyn King and Linda Gasparello. Thanks to them, and our guests on those episodes.

And finally, thanks to our great hair and makeup team, Allison Barbera and Jennifer Colleen Smith.

That first broadcast, BTW, was “The Death of Expertise” author, Naval War College professor and Harvard Extension School teacher Tom Nichols. We taped him on the same day as Native Americans Loren Spears, head of the Tomaquag Museum, and Christian Hopkins, a Standing Rock activist. They were the guests on the second week of our show, broadcasts the weekend of January 21, 2017.

Tom Nichols on set, right.

Tom Nichols on set, right.

Lrein spears and Christian Hopkins, center.These three set the tone for all that has followed. Gracias.

Lrein spears and Christian Hopkins, center.These three set the tone for all that has followed. Gracias.

We invite you to tune in during 2019, as we begin our third year on the radio and the telly. More great guests…

The TV debut, on Rhode Island PBS, was the next day, a Sunday, at 11 a.m., which remains our time slot today in the southeastern New England market (rebroadcasts Thursdays at 7:30 p.m.).

Since our debut, Story in the Public Square has won a Telly Award and, starting in September 2018, gone national -- now seen coast-to-coast in 22 of the top 25 U.S. markets and 76 percent of all U.S. markets. And co-host Jim Ludes and I have brought more than 100 storytellers to our audiences.

Story cast and Crew during recent taping of guests Alice Robb, center, and Mike Stanton, right of Robb.They come from the worlds of journalism, film, photography, academia, poetry, art, books, politics, medicine and more. Many have won national awards. All have informed and educated and many have also entertained -- and all have met our only request, to learn about their creative processes and how their stories impact public understanding and policy in America and the world. Jim and I listen more than talk. Story is about our guests and important issues, not us.

Story cast and Crew during recent taping of guests Alice Robb, center, and Mike Stanton, right of Robb.They come from the worlds of journalism, film, photography, academia, poetry, art, books, politics, medicine and more. Many have won national awards. All have informed and educated and many have also entertained -- and all have met our only request, to learn about their creative processes and how their stories impact public understanding and policy in America and the world. Jim and I listen more than talk. Story is about our guests and important issues, not us.The roots of Story in the Public Square date to February 2012, when Jim and I met for coffee, which began a conversation that led to the founding of the Story program at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center, which Jim heads. A partnership with The Providence Journal, where I am a staff writer, was formed and remains to this day.

The old saw holds that it takes a village -- but it’s true, and our guests belong to that village; without them, we’d be little more than a couple more talking heads yammering about whatever. And there are many others who have helped build our show. An anniversary is an appropriate time to acknowledge them.

Let me start with The Providence Journal, with publisher Janet Hasson and Executive Editor Alan Rosenberg. Thanks, Janet and Alan. Also, Jeff Beland, Marketing and Audience Development Director. And at GateHouse Media, our parent company, thanks to Lori Catron, Vice President Marketing Strategy & Communications.

At Salve, President Sister Jane Gerety has been supportive from the start. Teresa Haas, Office & Events Manager at the Pell Center, keeps the trains rolling on time – almost literally, as many of our guests come up from New York. Communications chief Erin Demers masterfully handles our social media, press and more. She succeeds Gianna Gerace and before Gianna, Mia Lupo, who also once held those responsibilities.

At our flagship station, Rhode Island PBS, so many! David W. Piccerelli, Kim Keough, Scott Saracen, Lori Sullivan, Cherie O’Rourke, Nick Moraites, Mark Smith, Joe Brathwaite, Andrew Vanasse, Lynn Nardone Young are among them. And our set designer, John Methia. And two people no longer at RIPBS who were instrumental in getting us off the ground: Dave Marseglia and Kathryn Larsen, Senior Director of Broadcasting for Radio and Television at WNED in Buffalo.

The broadcast beginnings of Story in the Public Square can be traced to the nine episodes Jim and I did as guest hosts in 2016 for White House Chronicle, hosted by Llewellyn King and Linda Gasparello. Thanks to them, and our guests on those episodes.

And finally, thanks to our great hair and makeup team, Allison Barbera and Jennifer Colleen Smith.

That first broadcast, BTW, was “The Death of Expertise” author, Naval War College professor and Harvard Extension School teacher Tom Nichols. We taped him on the same day as Native Americans Loren Spears, head of the Tomaquag Museum, and Christian Hopkins, a Standing Rock activist. They were the guests on the second week of our show, broadcasts the weekend of January 21, 2017.

Tom Nichols on set, right.

Tom Nichols on set, right.

Lrein spears and Christian Hopkins, center.These three set the tone for all that has followed. Gracias.

Lrein spears and Christian Hopkins, center.These three set the tone for all that has followed. Gracias.We invite you to tune in during 2019, as we begin our third year on the radio and the telly. More great guests…

Published on January 14, 2019 06:41

January 8, 2019

Story in the Public Square begins third season on SiriusXM Satellite Radio

For Immediate ReleaseContact: Erin Demers, Pell Center401-341-7462erin.demers@salve.edu

For Immediate ReleaseContact: Erin Demers, Pell Center401-341-7462erin.demers@salve.edu“Story in the Public Square” Renews Contract for Year Three with SiriusXM P.O.T.U.S.For the third consecutive year, Story in the Public Square will broadcast on SiriusXM P.O.T.U.S.

Newport, R.I.—The Pell Center at Salve Regina University will broadcast new, weekly episodes of “Story in the Public Square” for a third year on satellite radio provider SiriusXM’s P.O.T.U.S. channel, number 124.

Hosted by Jim Ludes, Executive Director of the Pell Center at Salve Regina University, and G. Wayne Miller, senior staff writer at The Providence Journal, “Story in the Public Square” features interviews with today’s best print, screen, music, and other storytellers about their creative processes and how their stories impact public understanding and policy. “We’ve been fortunate to have a great relationship with SiriusXM since we began production in 2017,” said Ludes. “We’ve reached an audience of people who care passionately about the issues and we’re excited to continue broadcasting on P.O.T.U.S in 2019.”

“The heart of ‘Story in the Public Square,’ is the guests we welcome each week,” said Miller. “Their stories, their analysis, their insights about public life and the human experience make the show what it is—and we have some great guests already lined up for the new year.”

The audio version of “Story in the Public Square” airs Saturdays at 8:30 a.m. & 6:30 p.m. ET, and Sundays at 4:30 a.m. & 11:30 p.m. ET on SiriusXM’s popular P.O.T.U.S. (Politics of the United States), channel 124. Episodes are also broadcast each week on public television stations across the United States. In Rhode Island and southeastern New England, the show is broadcast on Rhode Island PBS on Sundays at 11 a.m. and is rebroadcast Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. A full listing of the national television distribution, is available at this link.

“Story in the Public Square” is a partnership between the Pell Center and The Providence Journal . The initiative aims to study, celebrate, and tell stories that matter.

SiriusXM P.O.T.U.S. channel 124 features non-partisan political talk radio. SiriusXM is the world’s largest radio company with more than 33 million subscribers, offering commercial-free music; premier sports talk and live events; comedy; news; exclusive talk and entertainment, and a wide-range of Latin music, sports, and talk programming.

First published in 1829, The Providence Journal is the oldest continuously published daily newspaper in the United States.

For more information about Story in the Public Square, please visit http://pellcenter.org/story-in-the-public-square/.

Published on January 08, 2019 14:22

January 1, 2019

A new year brings two related anniversaries

Happy New Year! I hope 2019 holds blessings for all. I have expressed my personal wishes elsewhere. This is my professional greeting.

The year just started brings two related anniversaries.

The first is the 30th anniversary of the publication of my first book, the horror novel “Thunder Rise” (horror/sci-fi/mystery is another of my writing lives) God willing and the creek don’t rise (you Irish folks can appreciate that), I’ll post more about the book that began my author career come September, 30 years (gasp) after “Thunder Rise” landed on shelves.

The second is far more recent: the two-year anniversary of the debut of Story in the Public Square, the weekly and since September 2018 the national PBS and SiriusXM Satellite Radio show that I co-host and co-host with my good friend Jim Ludes.

The maiden Story broadcast, on January 14, 2017, featured Tom Nichols, of the Naval War College. Tom was the first of more than 40 authors who have appeared on our weekly show (with many more lined up for 2019). Many of these individuals wear other hats, but they are authors and they know that entering the authorial world is a milestone made possible only by means of dedication, discipline and old-fashioned elbow grease that anyone who has worked hard to achieve in any field understands.

Having myself passed that milestone 30 years ago and having never stopped writing books – it becomes a nagging part of your DNA – you fellow authors know whereof I speak! -- I began to support and encourage others who aspired to be published, or already were.

I did my best to park my ego at the door and mentor, applaud or listen to others I knew or who sought my counsel. Except for the readings and appearances, writing books is a lonely and frequently fruitless passion (think: trunk novel). It helps to have someone in your corner who has experienced the allure and frustration of the blank page -- and the magic of the filled.

So we have made a home for authors on Story in the Public Square. They come to us from Rhode Island and around the country, and from houses including Simon & Schuster, PublicAffairs, Penguin Random House and Harper Collins, and many university and niche presses.

Some are friends and former Providence Journal colleagues: Dan Barry and C.J. Chivers of The New York Times, and Kevin Sullivan, who co-authors with his wife and fellow Washington Post writer Mary Jordan. But most are people I had never met, except on the page, until they journeyed to our flagship station, Rhode Island PBS, to go before the camera.

In random order, these authors (in addition to Barry, Jordan, Sullivan and Chivers) have appeared on episodes of Story in the Public Square:

Alan Lightman, John Kerry, Mark Blyth, Padma Venkatraman, Sandeep Jauhar, Ross Douthat, Daniela Lamas, Larry Tye, Martin Puchner, Timothy Edgar, Omer Bartov, Margalit Fox, Eve Ewing, Tara Copp, Chris Brown, John Farrell, Tricia Rose, Julian Chambliss, Jeffrey Lewis, Sister Helen Prejean and Jed Shugerman.

Also, Heather Ann Thompson, Kenneth R. Miller, Teja Arboleda, David Jones, Paul Gionfriddo, Jason Healey, Allan A. Ryan, Oona A. Hathaway, Scott Shapiro, Michael D. Kennedy, Christopher Vials, Daniel W. Drezner, Robert B. Hackey, Adam Segal, Charles Dorn, Edward Luce and Gregg Easterbrook.

Thanks to our Story authors, and may 2019 bring more wonderful words from all of you!You can learn more about Story authors – and the full list of all of our guests and links to their appearances -- at https://pellcenter.org/story-in-the-public-square/episodes/https://pellcenter.org/story-in-the-public-square/episodes/

Published on January 01, 2019 04:07

December 25, 2018

Christmas 2018

Merry Christmas! And to my non-Christian friends, Happy Holidays! May we behold the spirit of the season, which is the spirit of peace and goodwill.

But first, let me briefly play Scrooge.

Even the most casual observer of current events knows that this nation and planet face crisis. The litany of troubles is long and they are grounded in the opposite of peace and good will: in discord and egoism. To which we could add greed, narcissism, prejudice, anger and hate.

And yet, as my late mother used to say: perhaps it is darkest before dawn. Perhaps the message of hope and redemption that is the story of Jesus’ birth and the foundational story of many other religions and belief systems is the story we should still tell.

As difficult as it sometimes can be reading the headlines, not to mention being in my line of work – journalism and public-affairs TV – in my heart, I still do.

The story of light and hope.

The Adoration of the Shepherds, pupil of Rembrandt.

The Adoration of the Shepherds, pupil of Rembrandt.I see it writ daily in a baby’s eyes, the joy of children and the selfless love of good parents. I see it in teachers and social workers and healthcare professionals and rescue personnel who risk their lives to save a stranger. I see it in artistic creation, in a great book, movie or TV show, in a comedian at the top of her or his game (we could all use a laugh, right?!) I see it in the quiet strength of people who live daily with medical and behavioral-health challenges. In people who toil at thankless jobs in order to support their families and hold the dream. In farmers, and in the clergy, scholars and scientists who dispel darkness and hold humanity high. In the generosity of philanthropists and those who practice Tikkun Olam. In my wife’s smile and her softly held hand. In my children and grandchildren and the colleagues and friends who fill and bless my life.

I see it in red sky at night, and in the birds and the gardens, slumbering now but counting on spring. So that is my hope on this Christmas – hope.

Hope that these many forces of light, which in number vastly outnumber the dark, will prevail. Let me part with a quote from that great American storyteller, Bruce Springsteen, who closed his recent Broadway show this way:

“Remember that the future is not yet written. So when things look dark, do as my mighty mom would insist. Lace up your dancing shoes and get to work.”

Come 2019, shall we?

Published on December 25, 2018 03:40

December 18, 2018

Remembering my father, Roger Linwood Miller

Author's Note: I wrote this six years ago, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of my father's death. Like his memory, it has withstood the test of time. I have slightly updated it for today, December 18, 2018, the 16th anniversary (plus one week!) of his death. Read the original here.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 16 years (and one week) ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 15th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 15 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now for three years and my best friend for more than a decade: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, Bella, Vivvie and Liv, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister Mary Lynne and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died in 2015. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 16 years (and one week) ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 15th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 15 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now for three years and my best friend for more than a decade: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, Bella, Vivvie and Liv, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister Mary Lynne and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died in 2015. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Published on December 18, 2018 02:11

October 3, 2018

Wolf Hill: An Essay About a Boy

I periodically repost some of my favorite essays. Here's one, set in autumn, my favorite season. I wrote this in October 1996, on a break from finishing my fourth book, Toy Wars: The Epic Struggle Between G.I. Joe, Barbie and the Companies That Make Them.

WOLF HILL

An Essay About a Boy

We avoid the woods in summer. We don't like bugs, the ticks and mosquitoes especially, and anyway, we're drawn to the beach at Wallum Lake, which is just up the road. But early October finds us eager for the first killing frost. It came this year at the customary time, when the sugar maples are at their peak and the oaks are only beginning to turn. The temperature at dawn read 29 or 30 degrees, depending on the angle the thermometer was viewed. I figured if any of my city friends asked, I'd say 29.

By late afternoon, it had warmed to almost 50. The sky was cloudless and the breeze had shifted to the south. I put on my boots and vest and helped Cal, who is almost three, on with his. Our vests have large pockets, very important for walks in the woods. We went through the backyard and onto the cart path that ascends Wolf Hill, a fanciful name in the nineties, even for a rural town like ours. Cal's first priority was equipping himself with a stick. He found one about two feet long, and another slightly larger, which he gave me. ``Little boys need big sticks,'' he observed. I wholeheartedly agreed.

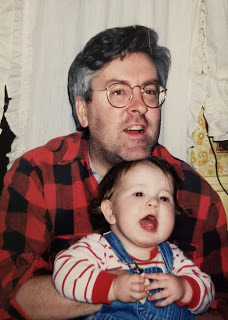

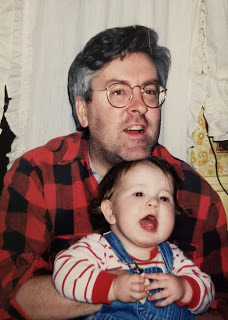

Young Calvin with his proud dad.Many years ago, when a farmhouse graced the top of Wolf Hill, the path could accommodate vehicles; one, a bus, ended its last journey up there and its rotting remains continue to be a source of wonderment to all who happen upon it. Every year the mountain laurel and pine claim more of the path, and this year was no exception, but there was still plenty of room -- more than sufficient, I informed Cal, for another good flying- saucer run this winter. Cal insisted on taking the lead and, unlike our last walk, in April, he refused assistance getting past deadfalls. He went under, or around, and then stopped to reveal the appropriate route to me. ``Dad, come on over here,'' he said at one point, ``that's a safe place to get by.''

Young Calvin with his proud dad.Many years ago, when a farmhouse graced the top of Wolf Hill, the path could accommodate vehicles; one, a bus, ended its last journey up there and its rotting remains continue to be a source of wonderment to all who happen upon it. Every year the mountain laurel and pine claim more of the path, and this year was no exception, but there was still plenty of room -- more than sufficient, I informed Cal, for another good flying- saucer run this winter. Cal insisted on taking the lead and, unlike our last walk, in April, he refused assistance getting past deadfalls. He went under, or around, and then stopped to reveal the appropriate route to me. ``Dad, come on over here,'' he said at one point, ``that's a safe place to get by.''

We climbed, past the inevitable stone walls, still remarkably intact, if mostly overgrown. The air seemed fresher as we continued, the light through the foliage stronger, and soon enough we'd reached the peak. Only a cellar hole is left of the farmhouse, destroyed some thirty years ago in a fire of suspicious origin. Rusting machinery, barrels and bedframes are strewn about, and the woods are slowly claiming them, too. We marveled together at a sight as strange as grape vines entwined around a bedframe, and I tried explaining how a house not unlike our own had been reduced to ruin, but I don't believe I succeeded, nor did I really try. I steered Cal's attention to the only grass on Wolf Hill, a small, sunlit remnant of lawn. We picked wildflowers, the last of the season. I did not know the species. They had thirteen petals and came in two shades: lavendar and white. The frost had not touched them. Cal was more interested in mushrooms. He'd been keen on mushrooms since our last swim at Wallum Lake, when he found ones as big as my hand that had materialized overnight beneath a picnic bench. He also gathered acorns, which he proposed to feed to squirrels, a word he still had difficulty pronouncing.

From the cellar hole, we descended to the quarry. I cautioned Cal not to run, but he explained that he was not -- this was skipping. I wanted to carry him or at least hold his hand; instead, I took a breath and was silent on the matter. The quarry has not been worked since the 1800s, but if you look around town, you will see many foundations made of its imperfect granite. Our own front steps, I am sure, came from here. Water has long filled where men once labored, of course, and a century's worth of sediment covers the bottom, making it impossible to gauge true depth (although we have tried, with our sticks). When Cal is a little older, I will tell him -- as I did his sisters -- spooky stories of the goings-on here when the moon is full. For now, we concern ourselves with water. It had not rained in over a week, and the stream that empties the quarry was dry. Our April walk was during a nor'easter, and we got soaked playing in the waterfall, but it was gone now, too. Cal was worried it would never return, but I reassured him it would, with the next steady downpour.

The shadows were lengthening and the temperature was edging down. An inventory of our pockets disclosed sticks, pebbles, acorns, flowers, mushrooms and a bright yellow leaf, which Cal had selected for his mom. We left the quarry and made our way back to the cart path through a stand of towering Balsam firs, unlike any other on Wolf Hill. When the girls were small, long before Cal was born, we found this place. It resembles a den, and the forest floor is softly carpeted and often dotted with toadstools -- certainly a spot, I allowed, where elves dance under the starry sky. Honest? Rachel and Katy were wide-eyed. There was only one way to know for sure, I said: Some fine summer night, we would have to camp out here, being careful to stay awake until midnight. We never did. Rachel is in high school now, and Katy, four years younger, is sneaking looks at Seventeen. Cal listened with great interest at the prospect of seeing elves. He was tired, and as I carried him home, I promised we'd camp out next summer, bugs and all. I intend to ask Rachel and Katy if they'd care to join us.

Copyright © 1997 G. Wayne Miller

WOLF HILL

An Essay About a Boy

We avoid the woods in summer. We don't like bugs, the ticks and mosquitoes especially, and anyway, we're drawn to the beach at Wallum Lake, which is just up the road. But early October finds us eager for the first killing frost. It came this year at the customary time, when the sugar maples are at their peak and the oaks are only beginning to turn. The temperature at dawn read 29 or 30 degrees, depending on the angle the thermometer was viewed. I figured if any of my city friends asked, I'd say 29.

By late afternoon, it had warmed to almost 50. The sky was cloudless and the breeze had shifted to the south. I put on my boots and vest and helped Cal, who is almost three, on with his. Our vests have large pockets, very important for walks in the woods. We went through the backyard and onto the cart path that ascends Wolf Hill, a fanciful name in the nineties, even for a rural town like ours. Cal's first priority was equipping himself with a stick. He found one about two feet long, and another slightly larger, which he gave me. ``Little boys need big sticks,'' he observed. I wholeheartedly agreed.

Young Calvin with his proud dad.Many years ago, when a farmhouse graced the top of Wolf Hill, the path could accommodate vehicles; one, a bus, ended its last journey up there and its rotting remains continue to be a source of wonderment to all who happen upon it. Every year the mountain laurel and pine claim more of the path, and this year was no exception, but there was still plenty of room -- more than sufficient, I informed Cal, for another good flying- saucer run this winter. Cal insisted on taking the lead and, unlike our last walk, in April, he refused assistance getting past deadfalls. He went under, or around, and then stopped to reveal the appropriate route to me. ``Dad, come on over here,'' he said at one point, ``that's a safe place to get by.''

Young Calvin with his proud dad.Many years ago, when a farmhouse graced the top of Wolf Hill, the path could accommodate vehicles; one, a bus, ended its last journey up there and its rotting remains continue to be a source of wonderment to all who happen upon it. Every year the mountain laurel and pine claim more of the path, and this year was no exception, but there was still plenty of room -- more than sufficient, I informed Cal, for another good flying- saucer run this winter. Cal insisted on taking the lead and, unlike our last walk, in April, he refused assistance getting past deadfalls. He went under, or around, and then stopped to reveal the appropriate route to me. ``Dad, come on over here,'' he said at one point, ``that's a safe place to get by.''We climbed, past the inevitable stone walls, still remarkably intact, if mostly overgrown. The air seemed fresher as we continued, the light through the foliage stronger, and soon enough we'd reached the peak. Only a cellar hole is left of the farmhouse, destroyed some thirty years ago in a fire of suspicious origin. Rusting machinery, barrels and bedframes are strewn about, and the woods are slowly claiming them, too. We marveled together at a sight as strange as grape vines entwined around a bedframe, and I tried explaining how a house not unlike our own had been reduced to ruin, but I don't believe I succeeded, nor did I really try. I steered Cal's attention to the only grass on Wolf Hill, a small, sunlit remnant of lawn. We picked wildflowers, the last of the season. I did not know the species. They had thirteen petals and came in two shades: lavendar and white. The frost had not touched them. Cal was more interested in mushrooms. He'd been keen on mushrooms since our last swim at Wallum Lake, when he found ones as big as my hand that had materialized overnight beneath a picnic bench. He also gathered acorns, which he proposed to feed to squirrels, a word he still had difficulty pronouncing.

From the cellar hole, we descended to the quarry. I cautioned Cal not to run, but he explained that he was not -- this was skipping. I wanted to carry him or at least hold his hand; instead, I took a breath and was silent on the matter. The quarry has not been worked since the 1800s, but if you look around town, you will see many foundations made of its imperfect granite. Our own front steps, I am sure, came from here. Water has long filled where men once labored, of course, and a century's worth of sediment covers the bottom, making it impossible to gauge true depth (although we have tried, with our sticks). When Cal is a little older, I will tell him -- as I did his sisters -- spooky stories of the goings-on here when the moon is full. For now, we concern ourselves with water. It had not rained in over a week, and the stream that empties the quarry was dry. Our April walk was during a nor'easter, and we got soaked playing in the waterfall, but it was gone now, too. Cal was worried it would never return, but I reassured him it would, with the next steady downpour.

The shadows were lengthening and the temperature was edging down. An inventory of our pockets disclosed sticks, pebbles, acorns, flowers, mushrooms and a bright yellow leaf, which Cal had selected for his mom. We left the quarry and made our way back to the cart path through a stand of towering Balsam firs, unlike any other on Wolf Hill. When the girls were small, long before Cal was born, we found this place. It resembles a den, and the forest floor is softly carpeted and often dotted with toadstools -- certainly a spot, I allowed, where elves dance under the starry sky. Honest? Rachel and Katy were wide-eyed. There was only one way to know for sure, I said: Some fine summer night, we would have to camp out here, being careful to stay awake until midnight. We never did. Rachel is in high school now, and Katy, four years younger, is sneaking looks at Seventeen. Cal listened with great interest at the prospect of seeing elves. He was tired, and as I carried him home, I promised we'd camp out next summer, bugs and all. I intend to ask Rachel and Katy if they'd care to join us.

Copyright © 1997 G. Wayne Miller

Published on October 03, 2018 07:34

August 29, 2018

Four decades: Children of Poverty, a five-part series

Why this post? Marking four decades in journalism, and you can read about that here.

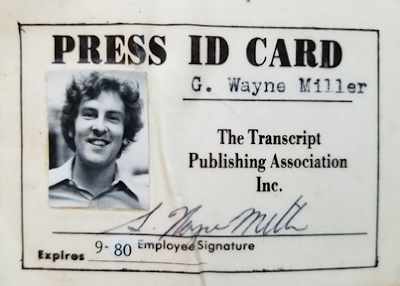

From August 28, 2018, through August 27, 2019, I will periodically post -- in no particular order and with no set number in mind (think: whimsy) -- some of my stories during my four decades as a journalist at three newspapers: The Transcript, in North Adams, Mass, now defunct; The Cape Cod Times, in Hyannis, Mass.; and since 1981 at The Providence Journal.

Today: Opening day of "Children of Poverty," a five-part series published in 1989, as I continued to explore social justice and disparities, issues about which I continue to write today.

CHILDREN of POVERTY: Behind from the start. Poor children, a vicious circle

Publication Date: November 26, 1989 Page: A-01 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

Part one of five parts.

Related stories on pages A-08, A-10 and A-11.

May 25, 1989.

Terrance Andre Smith has come into the world. He's a beautiful baby, healthy and normal, all dimples and flawless ebony skin. The joy of motherhood lights up Cheryl Smith as she cradles her third son, the very image of her, in their room at Providence's Women & Infants Hospital.

It is a universal moment.

Poignant, especially in light of the road that brought them here.

Since her own birth 28 years ago, the odds have been stacked against Cheryl. Given up by a sickly mother, she spent her childhood being shuffled from foster care to orphanage to reform school. She never met her dad. The one constant has been poverty. Cheryl Smith has hardly ever had a dollar to call her own.

Even against that background, this pregnancy defied the odds. As bad as things had always been for her, in 1988 they'd gotten worse.

In May of that year, her first four children were taken by the state, in large part because the Smiths - again - had found themselves homeless. Before Cheryl could find another apartment, a precondition of getting her children back, she was arrested on bogus car-theft charges. Unable to raise $250 for bail, she spent 16 days in jail, until a judge threw the case out.

It was mid-August. For a spell, she lived with Terrance's father, an occasional carnival worker who drifts in and out of her life, in an abandoned South Providence building that its 20 or so residents nicknamed The Dewdrop Inn. When that burned, taking with it the few items of clothing Cheryl owned, she moved into a 1977 AMC Matador that had no brakes but a good heater.

In November, when even a good heater couldn't ward off approaching winter, a doctor confirmed it: Cheryl was going to be a mother again.

By the first of the year, circumstances had improved, however marginally. Using donations begged from charitable organizations, she scraped together enough cash for an apartment. But the pleasure of having her own place, however ramshackle, was soon overshadowed by the realities of keeping it. Her rent - $400 a month, utilities not included - was $94 more than her monthly welfare payments.

Unable to afford oil, she heated with the three working burners of a gas stove. She had no refrigerator, no car, no money for baby clothes or crib. Using the bathroom after dark presented this choice: leaving the door open so light from the kitchen fluorescent fixture reached inside, or unscrewing the apartment's lone bulb from a living room lamp and carrying it in.

Medically, Cheryl was on shaky ground. A cigarette smoker and cocaine user who suffers from high blood pressure, her diet was too heavy on carbohydrates, too sparse on fresh vegetables and fruits. Anemia was diagnosed at a prenatal clinic for the poor, but it was weeks before she got a corrective prescription filled.

Somehow, she and Terrance made it.

As she smothers her newborn with kisses, as she whispers into his perfect little ears, Cheryl can be forgiven a burst of pride at what she has created.

"All I went through with him," she says. "In the streets, out of the streets, up, down . . . this baby's already been through everything. And to have him come healthy - hallelujah]"

An optimistic moment.

It won't last. Like an estimated 3,000 Rhode Islanders born every year - 1 in 4 - and hundreds of thousands nationwide, Cheryl Smith's baby will not have the same chances for a healthy, productive life as a baby born into a more affluent community.

Terrance was born poor.

In a couple of days, Cheryl plans to take him home to her apartment on Wendell Street, in Providence's West End. Like many poor neighborhoods, the culture is one where hope often is an illusion, frustration and despair the emotional landscape, drugs the temptation that doesn't go away.

Compared to, say, a typical Barrington baby, Terrance - not only poor, but black - is more likely to:

* Be homeless.

* Drop out of school.

* Fall victim to violent crime.

* Wind up behind bars.

* Contract AIDS.

* Remain underskilled and unemployed.

* Spend a lifetime in poverty.

* Father children out of wedlock, a situation likely to begin the cycle anew.

That's if Terrance survives childhood intact.

Chances are he - and the 12.6 million, or 1 in 5, American children who also are poor - won't. Because of his economic status, before Terrance reaches 18 he is more likely than his middle-class contemporary to be burned, poisoned, injured or abused. His overall health is more likely to be bad. His female counterparts are more likely to become pregnant while unmarried. Many of both sexes will give in to the instant gratification of crack and other drugs, modern America's scourge.

"A child who doesn't have the memory of a respectable past has no basis for creating a future," Lisbeth B. Schorr, lecturer in social medicine and health policy at Harvard Medical School, says in an interview. Her prescription for change, Within Our Reach, published last year, has been praised by politicians and social scientists alike.

"The Labor Department finds the fastest growing occupational category in this country is that of prison guard," Schorr says.

Unless the situation is turned around, she argues, "we're going to keep investing more in prisons, in building walls between the haves and the have-nots. We're going to have a more polarized society. We're going to have more violence. We're going to have more alienation.

"Absolutely, the future of the country is at stake."

The last thing Cheryl Smith had in mind was another child.

Neither did Cheryl's boyfriend expect a baby, although he hadn't given it much thought one way or the other. Terrance Cannon, 31 - known throughout South Providence as Tank, a nickname that aptly describes his physique - isn't in the habit of looking much past tomorrow.

When a doctor at South Providence's St. Joseph Hospital told Cheryl the bleeding she'd been experiencing was related to pregnancy, she was incredulous. Her next reaction was to get plastered. Sober, she considered abortion.

"If I'd had the money when I found out I was pregnant . . ."

She doesn't finish. "I couldn't have gone through with it," she explains. "I would have had to live with that guilt the rest of my life."

Cheryl pauses. She is not religious, not in the sense of organized worship, but she believes in God, even if she sometimes wonders where He is.

"In the beginning, I wanted this baby dead, dead, dead. But the Good Lord didn't want it to happen. Obviously it was meant to be for some reason. I thought: 'That'll be one more person in the world who will love me - and who I can love. Maybe this baby can teach me something.' "

Poor children have always been with us.

But not, since 1965, in such numbers.

According to the Census Bureau, 27.3 percent of U.S. children (under 18 years old) were poor in 1959, the first year such data was kept. By 1969, when most of former President Johnson's Great Society program was on line, the percentage had been virtually halved, to 14 percent.

Then the climb began, reaching 22.3 percent in 1983 before leveling off in the 20 percent range. Today, 12.6 million U.S. children, or 19.7 percent, live in officially defined poverty - which, for a family of four, was an annual income of $12,091 in 1988, the latest year for which poverty data is available. Since 1975, the poverty rate for children has been higher than for any other age group in the U.S.

Why the increase?

Demographers, economists and politicians cite a variety of factors.

Some point to reduced government aid to the poor, particularly in housing. Some look to changing morals - a legacy of the free-spirited '60s - and to an explosion of single-parent families. Others fault education. Still others see a fundamental shift in the economy from traditional manufacturing to high-tech industries requiring job skills more sophisticated than threading a spindle. Noting that 46 percent of all black children are poor - compared to 16 percent of white youngsters - many blame discrimination.

Yet another explanation is the growing disparity between the poorest and richest families. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a research group, the wealthiest fifth of the population last year received 44 percent of the nation's total family income - the biggest share ever - while the poorest fifth got less than 5 percent, the lowest percentage in 34 years.

Those traveling the moral high road are alarmed. So are captains of industry, for whom children are tomorrow's labor force.

Their concern is spelled out in the 1987 report, Children of Need, published by the Committee for Economic Development, an economic research group whose board of trustees includes officers from such corporate giants as Exxon, BankAmerica, General Motors and Sears. The report warned that a vital part of America - its economy - is endangered when so many young people are so poor, undereducated and unskilled.

"This nation cannot continue to compete and prosper in the global arena when more than one-fifth of our children live in poverty and a third grow up in ignorance," the report said.

"And if the nation cannot compete, it cannot lead. If we continue to squander the talents of millions of our children, America will become a nation of limited human potential. It would be tragic if we allow this to happen. America must become a land of opportunity - for every child."

Owen B. Butler, retired chairman of Procter & Gamble Co., was on the task force; he has since become CED's chairman. For the last two years, he has been on the lecture circuit, arguing for greater investment in early intervention, targeting children before they start school.

"The economic argument is simple," Butler says. "These children are going to be with us for their lifetimes - although, tragically, some of their lifetimes will be brief. They're going to be in our society as either producers or nonproducers. If they are producers, they will contribute to society. If they're nonproducers, they will detract from it."

There is no typical poor kid.

They live in cities and suburbs, the Grain Belt and industrialized Northeast, in housing projects and tumbledown trailers. Nationally, 7.5 million poor children are white or Hispanic, roughly 4.4 million are black. Some live with both mom and dad; but a greater number, nearly 7 million, live with mom alone.

Millions are the children of welfare recipients. Millions more are offspring of the working poor - people with jobs who find adequate housing, health care and proper nutrition a daily battle. With incomes just high enough to disqualify them for most government benefits, they live from paycheck to paycheck.

"One has to be absolutely clear that we're talking here in probabilities," says Harvard's Schorr. "There are kids from this kind of background who become Nobel Prize winners. It's just that the odds are they're going to have disastrous outcomes.

"These kids have no reason to believe that their effort is going to make a difference. If they're called upon to postpone gratificaton - whether it's by staying in school or saying no to drugs or by saying no to sex, they have no reason to do that. Because both from their own experience and in the lives around them, there is no evidence that hard work pays off."

For Cheryl, the only thing worse than taking her baby home to the ghetto would be not taking him home at all.

Losing her other children already was exacting a heavy emotional toll. With the state restricting visits to two hours every week or so, mother and children were becoming strangers to one another.

"The baby was really all I had," she'd often thought during the months she was pregnant. "I didn't have my other kids, I didn't have nothing. Just the baby inside me. That's what it really boiled down to."

Early the afternoon of Friday, May 26, as Cheryl is giving Terrance his bottle and thinking about the Memorial Day weekend, a social worker from the Women & Infants staff drops by. In a few minutes Cheryl is going to have a visitor, the worker explains. Someone - the social worker won't say who - has dialed the state's child-abuse hotline with a tip, something about Cheryl and cocaine. DCF has been looking into the situation.

The first step was running Cheryl's name through the agency's Child Abuse and Neglect Tracking System computer, which keeps files of all complaints, whether the allegations are substantiated or not by field investigation. Cheryl's name was there. More computer work and a synopsis of the Smith family history came up on a screen.

The DCF investigator - trained, like her colleagues, in quasi-police work - contacted South Providence's St. Joseph Hospital, where Cheryl received regular prenatal care. Sure enough, tests of Cheryl's urine taken during visits to the prenatal clinic had, on six of eight occasions, disclosed traces of cocaine.

The desire for a healthy baby had driven Cheryl to the St. Joseph prenatal clinic. But she was willing to go to almost any length to avoid further trouble with DCF, an agency she blames for many of her problems. Cheryl had chosen to deliver at Women & Infants in the hope that her St. Joseph records would not follow her.

Carrying a clipboard, Martha Donnelly, the investigator, closes the door.

Was Cheryl aware of the results from St. Joseph?

Yes, Cheryl says.

Did she know cocaine could be harmful to the unborn?

What do you take me for, an idiot? Cheryl snaps. Of course I knew. Didn't your snooping show I've been getting drug counseling this spring? Didn't that show I had a problem? But my cocaine use has been sporadic, a toke of a cocaine-sprinkled joint every now and then. Never much. And never crack.

Cocaine was very much in the news at this time.

"The cocaine epidemic that has swept this state over the past five years has outpaced the ability of various human service systems to cope with its effects on children and their families," said child advocate Laureen D'Ambra. Her report, released the day before Terrance Smith was born, was prompted by the death of a baby who'd been discharged from Memorial Hospital, Pawtucket, despite a test showing cocaine in his body. Less than two months later, the baby was dead of starvation.

Another story - it made Page One the week after Terrance Smith was born - reported the state medical examiner's finding that cocaine ingestion had killed a 6-week-old Central Falls baby.

The door opens and Donnelly disappears.

Before talking to Cheryl, Donnelly had been in touch with Terrance's pediatrician. No, the cocaine test results on the baby weren't back yet. But the doctor "had noticed some jitteriness in the baby's condition." A jittery baby can mean nothing. It can be a sign of cocaine withdrawal.

Based on "jitteriness" and Cheryl's positive tests, the investigator and her superiors decide Terrance should be kept at the hospital on a 72-hour hold - an order a doctor can unilaterally, and without appeal, enter. The hold will give DCF the chance to take Cheryl to court. Then it will be up to a judge.

"I got all sorts of things going through my heart, my brain," Cheryl says, cuddling her baby.

Her room is shiny and clean, but there is not a single card, no flowers or gifts, no newspapers or magazines to read. There is no money - not even spare change - in her purse, and no chance of any for four days, when the welfare check, all of it already owed to the electric company, arrives. Visitors might have cheered her up, but there have been few.

Tank was by her side for a few minutes during labor, but once the baby's head started to appear, he mumbled something about hospitals making him sick and took off. He hasn't been back. Word is he's been seen at a bar, but there's no way of confirming. Yesterday, Cheryl called her apartment. A strange woman answered, said she hadn't seen Tank, then hung up. When Cheryl called back, the phone was off the hook. It's been off ever since.

"Wish I had a gun," Cheryl says. "Wish I had a bomb. Wish I had a Mack truck. Wish, wish, wish]"

She goes to the window, looks out over the ruins of South Providence, her turf. Anger darkens her face.

"I feel like a caged animal. I was free for awhile and now I'm back in. I got nothing now. Nothing. A piece of paper and a pen - and wham] My baby's history."

Tears forming, she hugs Terrance tight.

"At least I got to name him."

* * *

REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK

I met Cheryl Smith one January morning at Amos House, the South Providence haven that feeds and shelters the poor. I was doing a story on how the haves and have-nots had fared during Ronald Reagan's presidency. I also was keeping an eye out for people I might spotlight for a series about the lives of Rhode Island's poorest children.

"There's no way poverty should be this doggone bad," Cheryl said when I asked her about Reagan's eight years.

So began a relationship that was destined to take photographer Frieda Squires and me on a nearly year-long journey with Cheryl and her five children. Theirs is in many ways a grim existence. But it is not entirely bleak, as Cheryl, with her sharp tongue and quick wit, showed me.

On that very first morning, I told Cheryl that I was not interested in a quick interview that I would gussy up with a fancy phrase and an alarming statistic and slap into the paper. Nothing so easy. It would mean spending hundreds of hours with her and her children, going into their homes, getting to know their friends, relatives and neighbors. It would mean a slew of personal questions. It would mean a lot of photographing and prying and record-combing, not necessarily a pleasant experience.

Cheryl said yes.

To my surprise, so did almost everyone else we talked to over the next several months.

From the start, I was impressed with Cheryl's candor and intelligence. I knew, long before our reporting was done, that here was a person who deserved better, as did her children. I knew instinctively that she was willing to share so much because she felt her story, by no means unique, was important to tell.

- Wayne Miller

* * *

HOW THE SERIES HAPPENED

In January, reporter G. Wayne Miller and photographer Frieda Squires began an investigation into the plight of Rhode Island's poor children. They went to schools, workplaces, welfare offices, shelters, soup kitchens, hospitals, health clinics, day-care centers. They examined police, court, state and medical records. They spent hundreds of hours in the inner city, in substandard housing and on the streets.

They report their findings in a five-part series beginning today and continuing daily in the Journal-Bulletin through Thursday.

Miller, 35, a graduate of Harvard College, has been with the Journal-Bulletin since 1981. His previous series were about the graying of America and deinstitutionalization, the policy of moving mentally disabled people from hospitals to the community. Miller is the father of two young girls.

Squires, 41, attended East Central University in Oklahoma and served in the Navy. She joined the Journal-Bulletin full time in 1985. Her photography has been recognized by the National Press Photographers Association, among other groups. Squires is the mother of two teenage boys.

From August 28, 2018, through August 27, 2019, I will periodically post -- in no particular order and with no set number in mind (think: whimsy) -- some of my stories during my four decades as a journalist at three newspapers: The Transcript, in North Adams, Mass, now defunct; The Cape Cod Times, in Hyannis, Mass.; and since 1981 at The Providence Journal.

Today: Opening day of "Children of Poverty," a five-part series published in 1989, as I continued to explore social justice and disparities, issues about which I continue to write today.

CHILDREN of POVERTY: Behind from the start. Poor children, a vicious circle

Publication Date: November 26, 1989 Page: A-01 Section: NEWS Edition: ALL

Part one of five parts.

Related stories on pages A-08, A-10 and A-11.

May 25, 1989.

Terrance Andre Smith has come into the world. He's a beautiful baby, healthy and normal, all dimples and flawless ebony skin. The joy of motherhood lights up Cheryl Smith as she cradles her third son, the very image of her, in their room at Providence's Women & Infants Hospital.

It is a universal moment.

Poignant, especially in light of the road that brought them here.

Since her own birth 28 years ago, the odds have been stacked against Cheryl. Given up by a sickly mother, she spent her childhood being shuffled from foster care to orphanage to reform school. She never met her dad. The one constant has been poverty. Cheryl Smith has hardly ever had a dollar to call her own.

Even against that background, this pregnancy defied the odds. As bad as things had always been for her, in 1988 they'd gotten worse.

In May of that year, her first four children were taken by the state, in large part because the Smiths - again - had found themselves homeless. Before Cheryl could find another apartment, a precondition of getting her children back, she was arrested on bogus car-theft charges. Unable to raise $250 for bail, she spent 16 days in jail, until a judge threw the case out.

It was mid-August. For a spell, she lived with Terrance's father, an occasional carnival worker who drifts in and out of her life, in an abandoned South Providence building that its 20 or so residents nicknamed The Dewdrop Inn. When that burned, taking with it the few items of clothing Cheryl owned, she moved into a 1977 AMC Matador that had no brakes but a good heater.

In November, when even a good heater couldn't ward off approaching winter, a doctor confirmed it: Cheryl was going to be a mother again.

By the first of the year, circumstances had improved, however marginally. Using donations begged from charitable organizations, she scraped together enough cash for an apartment. But the pleasure of having her own place, however ramshackle, was soon overshadowed by the realities of keeping it. Her rent - $400 a month, utilities not included - was $94 more than her monthly welfare payments.

Unable to afford oil, she heated with the three working burners of a gas stove. She had no refrigerator, no car, no money for baby clothes or crib. Using the bathroom after dark presented this choice: leaving the door open so light from the kitchen fluorescent fixture reached inside, or unscrewing the apartment's lone bulb from a living room lamp and carrying it in.

Medically, Cheryl was on shaky ground. A cigarette smoker and cocaine user who suffers from high blood pressure, her diet was too heavy on carbohydrates, too sparse on fresh vegetables and fruits. Anemia was diagnosed at a prenatal clinic for the poor, but it was weeks before she got a corrective prescription filled.

Somehow, she and Terrance made it.

As she smothers her newborn with kisses, as she whispers into his perfect little ears, Cheryl can be forgiven a burst of pride at what she has created.

"All I went through with him," she says. "In the streets, out of the streets, up, down . . . this baby's already been through everything. And to have him come healthy - hallelujah]"

An optimistic moment.

It won't last. Like an estimated 3,000 Rhode Islanders born every year - 1 in 4 - and hundreds of thousands nationwide, Cheryl Smith's baby will not have the same chances for a healthy, productive life as a baby born into a more affluent community.

Terrance was born poor.

In a couple of days, Cheryl plans to take him home to her apartment on Wendell Street, in Providence's West End. Like many poor neighborhoods, the culture is one where hope often is an illusion, frustration and despair the emotional landscape, drugs the temptation that doesn't go away.

Compared to, say, a typical Barrington baby, Terrance - not only poor, but black - is more likely to:

* Be homeless.

* Drop out of school.

* Fall victim to violent crime.

* Wind up behind bars.

* Contract AIDS.

* Remain underskilled and unemployed.

* Spend a lifetime in poverty.

* Father children out of wedlock, a situation likely to begin the cycle anew.

That's if Terrance survives childhood intact.

Chances are he - and the 12.6 million, or 1 in 5, American children who also are poor - won't. Because of his economic status, before Terrance reaches 18 he is more likely than his middle-class contemporary to be burned, poisoned, injured or abused. His overall health is more likely to be bad. His female counterparts are more likely to become pregnant while unmarried. Many of both sexes will give in to the instant gratification of crack and other drugs, modern America's scourge.

"A child who doesn't have the memory of a respectable past has no basis for creating a future," Lisbeth B. Schorr, lecturer in social medicine and health policy at Harvard Medical School, says in an interview. Her prescription for change, Within Our Reach, published last year, has been praised by politicians and social scientists alike.

"The Labor Department finds the fastest growing occupational category in this country is that of prison guard," Schorr says.

Unless the situation is turned around, she argues, "we're going to keep investing more in prisons, in building walls between the haves and the have-nots. We're going to have a more polarized society. We're going to have more violence. We're going to have more alienation.

"Absolutely, the future of the country is at stake."

The last thing Cheryl Smith had in mind was another child.

Neither did Cheryl's boyfriend expect a baby, although he hadn't given it much thought one way or the other. Terrance Cannon, 31 - known throughout South Providence as Tank, a nickname that aptly describes his physique - isn't in the habit of looking much past tomorrow.

When a doctor at South Providence's St. Joseph Hospital told Cheryl the bleeding she'd been experiencing was related to pregnancy, she was incredulous. Her next reaction was to get plastered. Sober, she considered abortion.

"If I'd had the money when I found out I was pregnant . . ."

She doesn't finish. "I couldn't have gone through with it," she explains. "I would have had to live with that guilt the rest of my life."

Cheryl pauses. She is not religious, not in the sense of organized worship, but she believes in God, even if she sometimes wonders where He is.

"In the beginning, I wanted this baby dead, dead, dead. But the Good Lord didn't want it to happen. Obviously it was meant to be for some reason. I thought: 'That'll be one more person in the world who will love me - and who I can love. Maybe this baby can teach me something.' "

Poor children have always been with us.

But not, since 1965, in such numbers.

According to the Census Bureau, 27.3 percent of U.S. children (under 18 years old) were poor in 1959, the first year such data was kept. By 1969, when most of former President Johnson's Great Society program was on line, the percentage had been virtually halved, to 14 percent.

Then the climb began, reaching 22.3 percent in 1983 before leveling off in the 20 percent range. Today, 12.6 million U.S. children, or 19.7 percent, live in officially defined poverty - which, for a family of four, was an annual income of $12,091 in 1988, the latest year for which poverty data is available. Since 1975, the poverty rate for children has been higher than for any other age group in the U.S.

Why the increase?

Demographers, economists and politicians cite a variety of factors.

Some point to reduced government aid to the poor, particularly in housing. Some look to changing morals - a legacy of the free-spirited '60s - and to an explosion of single-parent families. Others fault education. Still others see a fundamental shift in the economy from traditional manufacturing to high-tech industries requiring job skills more sophisticated than threading a spindle. Noting that 46 percent of all black children are poor - compared to 16 percent of white youngsters - many blame discrimination.

Yet another explanation is the growing disparity between the poorest and richest families. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a research group, the wealthiest fifth of the population last year received 44 percent of the nation's total family income - the biggest share ever - while the poorest fifth got less than 5 percent, the lowest percentage in 34 years.

Those traveling the moral high road are alarmed. So are captains of industry, for whom children are tomorrow's labor force.

Their concern is spelled out in the 1987 report, Children of Need, published by the Committee for Economic Development, an economic research group whose board of trustees includes officers from such corporate giants as Exxon, BankAmerica, General Motors and Sears. The report warned that a vital part of America - its economy - is endangered when so many young people are so poor, undereducated and unskilled.

"This nation cannot continue to compete and prosper in the global arena when more than one-fifth of our children live in poverty and a third grow up in ignorance," the report said.

"And if the nation cannot compete, it cannot lead. If we continue to squander the talents of millions of our children, America will become a nation of limited human potential. It would be tragic if we allow this to happen. America must become a land of opportunity - for every child."

Owen B. Butler, retired chairman of Procter & Gamble Co., was on the task force; he has since become CED's chairman. For the last two years, he has been on the lecture circuit, arguing for greater investment in early intervention, targeting children before they start school.

"The economic argument is simple," Butler says. "These children are going to be with us for their lifetimes - although, tragically, some of their lifetimes will be brief. They're going to be in our society as either producers or nonproducers. If they are producers, they will contribute to society. If they're nonproducers, they will detract from it."

There is no typical poor kid.

They live in cities and suburbs, the Grain Belt and industrialized Northeast, in housing projects and tumbledown trailers. Nationally, 7.5 million poor children are white or Hispanic, roughly 4.4 million are black. Some live with both mom and dad; but a greater number, nearly 7 million, live with mom alone.

Millions are the children of welfare recipients. Millions more are offspring of the working poor - people with jobs who find adequate housing, health care and proper nutrition a daily battle. With incomes just high enough to disqualify them for most government benefits, they live from paycheck to paycheck.

"One has to be absolutely clear that we're talking here in probabilities," says Harvard's Schorr. "There are kids from this kind of background who become Nobel Prize winners. It's just that the odds are they're going to have disastrous outcomes.

"These kids have no reason to believe that their effort is going to make a difference. If they're called upon to postpone gratificaton - whether it's by staying in school or saying no to drugs or by saying no to sex, they have no reason to do that. Because both from their own experience and in the lives around them, there is no evidence that hard work pays off."

For Cheryl, the only thing worse than taking her baby home to the ghetto would be not taking him home at all.

Losing her other children already was exacting a heavy emotional toll. With the state restricting visits to two hours every week or so, mother and children were becoming strangers to one another.

"The baby was really all I had," she'd often thought during the months she was pregnant. "I didn't have my other kids, I didn't have nothing. Just the baby inside me. That's what it really boiled down to."

Early the afternoon of Friday, May 26, as Cheryl is giving Terrance his bottle and thinking about the Memorial Day weekend, a social worker from the Women & Infants staff drops by. In a few minutes Cheryl is going to have a visitor, the worker explains. Someone - the social worker won't say who - has dialed the state's child-abuse hotline with a tip, something about Cheryl and cocaine. DCF has been looking into the situation.

The first step was running Cheryl's name through the agency's Child Abuse and Neglect Tracking System computer, which keeps files of all complaints, whether the allegations are substantiated or not by field investigation. Cheryl's name was there. More computer work and a synopsis of the Smith family history came up on a screen.

The DCF investigator - trained, like her colleagues, in quasi-police work - contacted South Providence's St. Joseph Hospital, where Cheryl received regular prenatal care. Sure enough, tests of Cheryl's urine taken during visits to the prenatal clinic had, on six of eight occasions, disclosed traces of cocaine.

The desire for a healthy baby had driven Cheryl to the St. Joseph prenatal clinic. But she was willing to go to almost any length to avoid further trouble with DCF, an agency she blames for many of her problems. Cheryl had chosen to deliver at Women & Infants in the hope that her St. Joseph records would not follow her.

Carrying a clipboard, Martha Donnelly, the investigator, closes the door.

Was Cheryl aware of the results from St. Joseph?

Yes, Cheryl says.

Did she know cocaine could be harmful to the unborn?

What do you take me for, an idiot? Cheryl snaps. Of course I knew. Didn't your snooping show I've been getting drug counseling this spring? Didn't that show I had a problem? But my cocaine use has been sporadic, a toke of a cocaine-sprinkled joint every now and then. Never much. And never crack.

Cocaine was very much in the news at this time.

"The cocaine epidemic that has swept this state over the past five years has outpaced the ability of various human service systems to cope with its effects on children and their families," said child advocate Laureen D'Ambra. Her report, released the day before Terrance Smith was born, was prompted by the death of a baby who'd been discharged from Memorial Hospital, Pawtucket, despite a test showing cocaine in his body. Less than two months later, the baby was dead of starvation.

Another story - it made Page One the week after Terrance Smith was born - reported the state medical examiner's finding that cocaine ingestion had killed a 6-week-old Central Falls baby.

The door opens and Donnelly disappears.

Before talking to Cheryl, Donnelly had been in touch with Terrance's pediatrician. No, the cocaine test results on the baby weren't back yet. But the doctor "had noticed some jitteriness in the baby's condition." A jittery baby can mean nothing. It can be a sign of cocaine withdrawal.

Based on "jitteriness" and Cheryl's positive tests, the investigator and her superiors decide Terrance should be kept at the hospital on a 72-hour hold - an order a doctor can unilaterally, and without appeal, enter. The hold will give DCF the chance to take Cheryl to court. Then it will be up to a judge.

"I got all sorts of things going through my heart, my brain," Cheryl says, cuddling her baby.

Her room is shiny and clean, but there is not a single card, no flowers or gifts, no newspapers or magazines to read. There is no money - not even spare change - in her purse, and no chance of any for four days, when the welfare check, all of it already owed to the electric company, arrives. Visitors might have cheered her up, but there have been few.