G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 10

April 26, 2020

Car Crazy

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I am regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at this time!

This is the fifth free offering: An excerpt from “Car Crazy: The Battle for Supremacy Between Ford and Olds and the Dawn of the Automobile Age," my 15th published book.

Chapter One: Fastest Man on Earth

The 999 and Arrow

It was a time when sane people did crazy things.

Henry Ford was one of those people.

On January 9, 1904, on the shore of frozen Anchor Bay, Lake St. Clair, some 30 miles northeast of Detroit, he vowed to be the first person to drive 100 miles per hour. The possibility that he might spin out of control and be killed as he roared across the ice did not deter him.

It did, however, attract a crowd.

Ford had deliberately scheduled his attempt for a Saturday, when kindly employers gave their workers the afternoon off. Then he’d created publicity that had filled the Detroit papers all week, mesmerizing a city that had already begun to thrum with the business of motors.

A brilliant inventor and engineer, Ford also was a skilled marketer. He knew that machine-powered speed excited many people unlike anything before — and that word of the latest spectacle sent consumers to dealers, where they could buy an automobile of their own. He knew also that cars angered and alienated other people — the horse-bound traditionalists — but with time, he believed, almost everyone would come around.

“Henry Ford of the Ford Motor Works of Detroit will attempt to lower the Worlds Record,” read the handbills Ford had arranged to be posted. “The race will be over a four-mile straight track on the ice opposite The Hotel Chesterfield. The snow will be cleared from the ice and the track will be sanded. The races will start at 2 o’clock and continue until Mr. Ford lowers the world’s record. He proposes to make a mile in 36 seconds.”

That would greatly eclipse the existing auto record of 84.732 miles per hour, set in 1903. It conceivably would be faster than anyone had ever moved on land.

The claimed land speed record was 112.5 miles per hour by the crew of a locomotive on May 10, 1893, on a stretch of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s mighty New York Central Railroad, but in this era so rife with tall tales, doubt existed that the train, the 999, had really travelled faster than about 90 miles per hour. Nonetheless, the train had generated international headlines — and Ford, hoping to capitalize on its fame, named one of the two identical racecars that he built after it. Like that 62-ton locomotive, Ford’s 999 racer and its twin, Arrow — the machine that Ford had brought to frozen Lake St. Clair — were essentially monster motors on wheels, producing as much as 80 horsepower, ten or more times the power of many stock models — “built to speed, and speed alone,” wrote The Automobile and Motor Review.

Many in the crowd knew about Ford, this slightly built 40-year-old man with the piercing gray eyes, prominent nose and long, thin hands who seemed always to have a sly grin on his lips. He had been building and driving horseless carriages around Detroit since 1896, when American-built cars were little more than a dream, and had founded and then left two other companies before incorporating a third, the Ford Motor Company, on June 16, 1903.

Son of a farmer, raised on a farm outside Detroit, Ford should have been destined to till the land, like so many of his 19th-century peers. But even as a young child his father’s tools fascinated him more than horses or fields, and by the time he turned teenager, machines had become his obsession. At first it was unpowered machines, the watches and clocks he taught himself to take apart and repair. And then, not long after, he saw his first steam engine. The operator took the time to explain its mechanizations to the boy. And thus was Ford’s true destiny revealed to him.

Many in the shivering crowd also already knew about Ford’s racecars from the man who had steered several of them to national headlines: Barney Oldfield, the greatest American racecar driver of the early era, a man even more daring than Ford. A champion bicyclist at age 16, Oldfield had never driven a motor vehicle of any kind until Ford, seeking publicity for his second attempt at an auto company, asked him to race the 999 in a competition. At the time, Ford himself was leery of driving it, except on the test track. Saying he would try anything once, Oldfield, 24, agreed. Ford entered the 999 into the October 1902 Manufacturer’s Challenge Cup at Detroit’s Grosse Pointe Blue Ribbon Track, venerable home of harness racing, and set about acquainting Oldfield with the car’s quirky features.

“It took us only a week to teach him to drive,” Ford later recalled. “The man did not know what fear was. All that he had to learn was how to control the monster.” Meaning specifically, how to steer it through corners without rolling over.

“The steering wheel had not yet been thought of,” Ford recalled. “On this one, I put a two-handed tiller, for holding the car in line required all the strength of a strong man.”

While Ford was cranking the 999 to life, Oldfield said: “Well, this chariot may kill me, but they will say afterward that I was going like hell when she took me over the bank.”

He did go like hell, winning that October 1902 race against the already legendary automaker and racer Alexander Winton, who until then was thought to be invincible.

In the summer of 1903, Oldfield drove Ford’s Arrow to world records at Midwest fairgrounds and then on July 25, at a track in Yonkers, New York. A few weeks later, he raced again at Grosse Pointe. He had just passed the leader when a tire exploded and Arrow plowed into a fence, killing a spectator from Ohio. Oldfield, a newspaper reported, and “escaped by a miracle, as his machine was reduced to a mass of tangled iron and wood. That more people were not killed or maimed is a cause for wonder.” Cocky and gifted, a man who loved women as much as machines, Oldfield would maim and kill many more before the end of his career.

As Oldfield recovered from his injuries, the repaired Arrow took the starting flag in Milwaukee a week after the luckless Ohio man’s death. Promising young racer Frank Day was at the wheel. But the Arrow proved too much to manage, and he spun out of control. Ford’s racer rolled end over end, landing “on the unfortunate chauffeur, grinding him into the ground, an unrecognizable mess,” a paper reported.

For those who did not share autoists’ enthusiasm — and there were many who did not, influential politicians, judges, and editorialists among them — Day’s death was new cause for condemnation.

“We saw the young man who rode to his death on the day preceding the fatality,” the Wisconsin State Journal opined. “A cleaner, fresher youth never delighted his parents’ eyes. The wind tousled his abundant hair on his clear forehead as he whirled about the track; determination and enthusiasm were in his eyes; the cheers of the impassioned mob impelled him as soldiers go to certain death under martial music.”

And then, an unrecognizable mess.

“We are not wholesome enough to enjoy the triumphs of the soil and noble horses and royal-blooded cattle,” the State Journal proclaimed. “The incident is a disgrace.”

For Ford, it was a disquieting but momentary setback. Back in Michigan, he rebuilt Arrow once again. He had further use for its awesome power.

Pure speed was not the only lure for the spectators in their gloves and fur-trimmed coats at Lake St. Clair on that January day in 1904. In the first half-decade of what would be called the American Century, railroads, ships, bicycles, horses and horse-pulled vehicles still transported most people and goods, but the country was witnessing an astonishing proliferation of horseless carriage manufacturers and models. Every new entry seemed to generate buzz. Whether you liked cars or hated them, lived in a city where they swarmed the streets or in the country where they were rarely, if ever, seen, you could hardly get through a day without talking about them.

Car-making had started in earnest in America just a decade before, with bicycle maker Charles Duryea, 31, in partnership with his 24-year-old mechanic brother, Frank—the first Americans to publicly declare their intention of creating a commercial enterprise from building and selling cars, contraptions most folks at the time thought were cobbled together by men possessing more free time than common sense. In September 1893 in Springfield, Massachusetts, Frank completed construction of a vehicle that married a custom-built single-cylinder gasoline motor to a horse-drawn phaeton buggy purchased second-hand for $70.

Shortly before he road-tested the car, Frank granted an interview to the Springfield Evening Union, which published a story on September 16, 1893, under the headline:

Springfield Mechanics Devise a New Mode of TravelIngenious Wagon Being Made in This CityFor Which the Makers Claim Great Things

“A new motor carriage when, if the preliminary tests prove successful as expected, will revolutionize the mode of travel on highways, and do away with the horse as a means of transportation, is being made in this city,” the reporter wrote. “It is quite probable that within a short period of time one may be able to see an ordinary carriage in almost every respect running along the streets or climbing country hills without visible means of propulsion.”

Frank was more than a good pitchman. The car he had built with his brother’s support and the backing of lone financial backer Erwin F. Markham, a nurse who had invested $1,000 in the Duryeas, did indeed succeed its first time on the road. On the afternoon of September 20, the vehicle was hauled by horse from Frank’s machine shop to a friend’s yard on the outskirts of the city. The next morning, Frank took a streetcar out to the neighborhood. As he rode, he fantasized that “once well started on the open road, the machine would roll along sweetly for at least a mile or two… With this pleasant thought in mind, I enthusiastically pushed the car from under the apple tree.”

Frank started the engine and his car chugged onto Spruce Street. “America’s first gasoline automobile had now appeared,” he would recall. “It had done what it was designed and built to do, in that it carried the driver on the road and had been steered in the direction the driver wished to go.”

The car only travelled about 100 feet before stalling — but it restarted quickly, and each time again after successive stallings, providing sufficient encouragement for the Duryeas to continue. By March 1895, they had a smoother-operating machine that successfully completed an 18-mile round trip to Westfield, Massachusetts, along rough, steep, horse-ravaged roads — a feat that suggested the brothers really were onto something. On September 21, 1895, they incorporated the Duryea Motor Wagon Company.

“Those who have taken the pains to search below the surface for the great tendencies of the age know that a giant industry is struggling into being,” wrote the editor of The Horseless Age, America’s second automobile journal, in its inaugural issue, published in November 1895. “It is often said that a civilization may be measured by its facilities of Locomotion. If this is true, as seems abundantly proved by present facts and the testimony of History, the New Civilization that is rolling in with the Horseless Carriage will be Higher Civilization than the one that you enjoy.”

Like The Horseless Age’s editor, the growing ranks of motorists saw the car as the future; along with the locomotive, the telegram, photography, and electricity, it was a technology that would move mankind valiantly forward. They envisioned a time when a motorist could comfortably drive from East Coast to West and all points between –– when everyone could, and would, own a car.

This vision of the future seemed fairly delusional to the naysayers, whose numbers grew as the 19th century gave way to the 20th. They viewed the gas- and steam-powered car, by whatever name, as a loud, dangerous and polluting fiend that threatened the social fabric — an enemy of God-fearing people and noble horses. They dismissed the car, however propelled, as a fad soon to fade. Common sense alone told you it couldn’t last.

In those early days, most cars were so finicky that repair kits were included as standard features and wealthy owners hired mechanics to ride with them. Many cars had no cabins, roofs, headlamps, or doors. They could explode or burst into flame for no apparent reason. “As gasoline tanks and leads sometimes leak and the fluid more rarely becomes ignited,” The Automobile, a leading weekly wrote, “it is a wise precaution on the part of the automobilist to carry a fire extinguisher in the car for such emergencies. Even though it may never be required, it will add something to the driver’s feeling of security; and should it ever be wanted, it will, like a revolver in the West, be wanted badly.”

And if the machine itself was at a primitive stage of development, the experience of motoring was cruder still. No training, registration or licenses to drive were required in most jurisdictions. There were few stop signs and no traffic lights. Accidents that injured or killed motorists and pedestrians abounded. Only a tiny percentage of U.S. roads were hard-surfaced. Service stations were scarce, gasoline rare in the outskirts and smaller cities, maps unreliable or non-existent. Motorists venturing off the beaten path were advised to carry guns, for protection against wildlife, irate horse-loving citizens, and ornery constables determined to avenge the evil of the new machine.

Regardless, the car was a siren’s call to inventors, entrepreneurs and all manner of tinkerers. In America, as in Europe, a new sort of gold rush was underway.

Like the Duryeas, some of the new manufacturers had been building bicycles before falling under the spell of the self-propelled machine. Horse-drawn carriage builders also sensed opportunity, as did blacksmiths, ship builders, sewing-machine makers, and many others. Unlike the railroad, petroleum, coal, and steel industries, the cost of entry was minimal. Not even a technical background was required, at least to stake a claim: In March 1901, an industry publication reported that The Reverend H.A. Frantz of Cherryville, Pennsylvania, “believes he has received a call to the motor trade, and will henceforth make petrol cars in place of sermons.”

This was an era when many car companies managed to build just a single vehicle or two a year and annual production of a few dozen was cause for Hallelujah. The Duryea brothers’ Duryea Motor Wagon Company, the first U.S. firm to serially produce a car, built and sold just 13 vehicles during its first full year of operation, 1896; sales were sporadic after that and in 1898, with Frank and Charles feuding, the company went out of business.

This was by far the most common story of the early era. According to calculations Charles Duryea made in 1909, in the years 1900 to 1908, 502 U.S. car makers went into business, an average of 55 a year, or more than one a week. Of that total, 273 failed, and another 29 went into some other field, a failure rate of greater than 60 percent.

Given his obsession with machines and his gift for building and improving them, Henry Ford seemed to have decent odds at enduring success. His business record, however, suggested he had much to learn. Two previous companies he’d started had failed, and rival firms—particularly industry leader Olds Motor Works, whose founder Ransom Eli Olds also was greatly gifted with machines —were already building devoted followings. Ford needed more than just a good car if he were to succeed. In this frenzied period, so filled with competition, he needed attention. Speed records and racing got attention.

The winter sun shone weakly, bringing no warmth to the people lining the shore near the front porch of the Hotel Chesterfield. Among them were Ford’s wife, Clara, and the couple’s only child, their 10-year-old son, Edsel.

The Chesterfield, since it first opened in 1900, was one of the finest establishments in the resort community of New Baltimore, known for its mineral baths, opera house, saloons, and bathing, fishing, and sailing on Anchor Bay, just an hour by rail from Detroit. It offered the best food and amenities, including electric lights and steam heat throughout. Here was a clientele that might buy a Ford car; possibly, a potential investor or two was lurking in the crowd that second Saturday of January 1904. A much larger audience would read about Ford’s attempt in the newspapers, thanks to the reporters on hand.

The ice-boat races Ford had arranged as a sort of opening act ended and the Arrow racecar was brought onto the ice. It was ugly and weird. It looked like it had been concocted by someone who had failed his mechanics apprenticeship and taken to whisky, not by an engineering genius. How else to explain its steel-reinforced wood frame, spoked wheels, single seat, and bewildering arrangement of exposed wires, gears, levers and controls – all in the service of an open motor that occupied nearly half the length of the vehicle and drenched the driver in oil and grease when it fired, for it had no oil pan or engine compartment.

Men hired by Ford had cleared a 15-foot-wide strip of ice four miles long on Anchor Bay, then coated it with cinders from the coal-fired power plant north of The Hotel Chesterfield. The first two miles would allow Arrow to come up to speed, the third mile would be timed, and the last was for deceleration. The event would have been easier (not to mention warmer) on the long, flat sands of Ormond Beach, Florida, just north of Daytona, future birthplace of NASCAR, where racing already was enormously popular. But the auto show at New York's Madison Square Garden, America’s largest, began the next weekend, before the start of the Daytona season. Ford hoped to arrive in Manhattan with a headline-making story of the incredible cars he could build.

Assuming no tragic accident occurred, that is. A thought that, when Ford walked onto the ice, left him uncharacteristically unnerved.

But it was too late to stop.

“If I had called off the trial,” he later said, “we would have secured an immense amount of the wrong kind of advertising.”

Starting any car in 1904 was never easy — but firing in sub-freezing temperatures one of the largest automobile engines ever built was akin to raising the dead. Ford called on Edward S. “Spider” Huff, one of a small group of employees whose mechanical skills and ingenuity rivaled the boss’s. So valuable was Huff to Ford that the boss not only forgave him his habit of chewing tobacco, which Ford loathed, but allowed him to install a spittoon in his car. He also overlooked Spider’s disappearances for days inside houses of ill repute, where he sought relief from his recurring depression.

Spider warmed parts of Arrow with a blow torch and poured hot water into the cooling system to help coax the beast to life. A spectator volunteered to hand-crank the open engine, whose cast-iron heart was four massive seven-by-seven-inch cylinders.

The motor caught with a thunder that rattled the windows of the Hotel Chesterfield. Flame shot from Arrow’s exhausts and oil sprayed everywhere.

“The roar of those cylinders alone was enough to half kill a man,” Ford said of the first time they had been fired. More shock had awaited when he took Arrow and 999 onto the test track on its maiden run. “We let them out at full speed,” he said. “I cannot quite describe the sensation. Going over Niagara Falls would have been but a pastime after a ride in one of them.”

Ford took his seat. A warm-up run revealed something no test course or track had predicted: when the car hit fissures in the ice, the impact rattled the vehicle so violently that the driver could not keep a steady hand on the gas. Ford would never be able to bring Arrow full-throttle alone. Spider would have to ride with him, one hand controlling the gas and the other holding on, while hunkered down on the floorboards. There was no other place on the racecar. “There was only one seat,” Ford said.

The afternoon was advancing, the January sun weakening. The American Automobile Association, the AAA, had agreed to officially certify the race –– but the organization’s three timers were tardy and Ford decided to make a run without them. His speed would not be official, but at least he’d have a number. As the iceboats circled, Spider and Ford drove to the start of the four-mile course. Men with stopwatches stood ready.

Spider leaned on the gas and Arrow rocketed down the ice. This time, the fissures did more than rattle and shake — they launched the car repeatedly into the air. The laws of physics were being tested, but Ford and Spider miraculously maintained control.

Some four minutes later, they coasted to a stop.

A speed of 100 miles an hour had been clocked.

That indeed buried the existing mark of 84.732 miles per hour, set on solid ground two months before by Arthur Duray, a 21-year-old who drove a French-built stock car that, its manufacturer claimed, could run not just on gasoline but also gin or brandy, presumably an enticement to the upper-class buyer in those twilight days of the Gilded Age. Duray’s record was the latest in a series of officially sanctioned advances that dated back to 1898, when a wedge-shaped, battery-powered vehicle had reached 39.2 mph, about as fast as a thoroughbred could gallop.

But Ford’s mark was not official: the AAA timekeepers had not arrived.

When they finally did, Ford brought Arrow back to the start of the course. But the car’s 225-pound flywheel whirred loose, nearly hitting him and Spider. “Ford narrowly escaped with his life,” wrote the Detroit Journal, which called Ford “a mechanic who began to design automobiles several years ago, when the craze for them began.”

Repairs could not be accomplished in the waning light, and the contest was postponed until Tuesday afternoon, January 12. With luck, Ford might still make it to New York a hero.

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

LANDING PAGE for all the Free Reads during #coronavirus

Published on April 26, 2020 04:29

April 22, 2020

Thunder Rise

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I am regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at this time!

This is the fourth free offering: An excerpt from “Thunder Rise: A Novel of Terror,” my first published book and the first volume of the Thunder Rise trilogy..

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

Friday, October 10

Maureen McDonald was appreciably worse.

She was back in Bostwick’s office this morning, two weeks and two days after her last visit. Her mother was on the verge of panic. Bostwick didn’t blame her. If she’d been his child, he’d have been there, too.

Because things didn’t look good. Things didn’t look good at all. Maureen’s temperature was 103.8, and she was enveloped by a faint, sweaty odor, an odor not dissimilar to garlic—the exact same odor, Bostwick thought with a chill, that terminally ill patients get as their days are winding down. She was still congested, still occasionally experiencing sharp abdominal pains (“like a knife,” she said, “stickin’ in my stomach.”). Every lymph node he touched was swollen and tender.

But he hadn’t needed an examination to conclude there was something really frightening going on with this child. He’d sensed that the instant she’d come into his office, shuffling listlessly, her head down, her shoulders hunched, as if the world no longer held any interest for her. A little more than two weeks ago she’d been under the weather, but if you peeled back the aches and pains a bit, you could still see her spirit, alive and well. Now there was barely a hint of that spirit. Now her eyes had a lifeless, distant glaze to them, as if she’d grown tired of seeing. The eyes especially bothered him. He’d learned there was more than a grain of truth to the old adage that eyes were windows to the soul.

The original cover: William Morrow, 1989.If it hadn’t developed so quickly, he would have suspected cancer . . . or AIDS.

The original cover: William Morrow, 1989.If it hadn’t developed so quickly, he would have suspected cancer . . . or AIDS.He hated what he had to subject her to, but there was no choice. It was time to go on a medical fishing expedition.

“Can you be in Pittsfield this afternoon?” he asked Susie when her daughter had shuffled back to the waiting room to claim the lollipop her eyes said she didn’t care if she had or not.

“Yes,” Susie said.

“Good. I want you at Berkshire Medical Center at one. I’ll call and make the arrangements. She’s going to need additional tests.”

“What kind of tests?” Susie sounded as if she’d just been sentenced.

“Blood tests. X-rays. Possibly a liver scan. I’ll have a better idea after consulting with Dr. Miller. He’s an internist at Berkshire Medical. Also a personal friend. A very capable physician.”

“Doctor?”

“Yes?”

“What do you think it is?” Bostwick could tell she was close to losing control. His eyes avoided hers, and the examining room suddenly seemed too small, too quiet, too warm. He’d been here before. Oh, yes. Ordering tests for suspected leukemia cases evoked this mood. Getting positive test results back and delivering that horrible news evoked it, too.

“I don’t know,” he said. “And I’m being completely candid. I just don’t know.”

“You don’t think it’s a cold, do you?” Susie said, allowing herself only the faintest trace of hope.

“Like a really long cold?”

“No. Not anymore.”

“Is it a—a virus?”

“It could be. We’ll know better after this afternoon. I’m ordering her workup stat.”

Susie was silent. In the last two minutes Bostwick had seen the color drain from her cheeks. “You don’t think it’s—you don’t think it’s cancer, do you?” She pronounced that word superstitiously, as if saying it too loudly might jinx her.

“I’d be very surprised if it were. It’s very rare that cancer—any kind of cancer—develops so quickly.”“It’s been two months almost.”

“And that seems like a long time—and it is, in terms of what you’ve been through—but disease-wise, two months is a snap of the fingers.”

“Doctor?”

“Yes?”

“She’s going to be all right, isn’t she?”

In all his years of medicine—years in which he had had a distressing amount of practice in delivering the grimmest possible news—he’d never learned how to answer this question without feeling like the world’s biggest asshole.

“I hope so,” he said. “Now I want you to get going. The sooner you’re there, the quicker you’ll be home.”

Crossroad Press editions: Audible and Kindle.

Crossroad Press editions: Audible and Kindle.

For two weeks he’d been trying to piece things together.

Something’s going on. Something I’ve never seen in almost a decade of family practice.

That much was indisputable now. This wasn’t your basic infection taking the scenic tour through the local youth, a bout of unusually stubborn rhinovirus that sooner or later would be put off the bus by said youths’ immune systems. It had gone on too long. On Morgantown’s scale, this was as close to a public health crisis as anything in Bostwick’s experience.

Because there were too many sick kids out there. Not a townful, or a schoolful, but seventeen kids (he’d counted) with no history of chronic disease or unusual susceptibility who all of a sudden were sick as dogs. Seventeen kids, up from a dozen two weeks ago, all with a common set of symptoms, all with parents getting more uptight by the minute. Some—roughly half, Bostwick calculated—seemed to be getting progressively sicker. A smaller group appeared to be on some kind of strange disease seesaw: flat on their backs one day, chipper as you please the next. A couple, Jimmy Ellis among them, seemed to have recovered and not relapsed—if that was the word. There seemed to be no rhyme or reason.

For two weeks he’d puzzled over it, so intensely that his wife and children had started to comment. For two weeks he’d done his homework. Taken out the case folders each evening and gone over every iota of information with a magnifying glass. He’d done follow-ups on every child, which had meant house calls in a couple of instances. Maureen was the first he’d referred to Berkshire Medical. He knew she would not be the last.

It could be almost anything.

That’s what was beginning to give him chills.

It could be bacterium. It could be virus. It could be some kind of obscure but cumulatively lethal poison. It could be something in the water at school. It could be something in the food. Something in the air. Something well documented in the public health texts. Something utterly unprecedented.It could be the bloody Martians, for all he knew, dropping down to field-test their latest extraterrestrial bug on the unsuspecting inhabitants of Planet Earth.

If he’d been unable to pinpoint the cause, he’d at least uncovered some potentially valuable common denominators. All the children were prepubescent. All except for two preschoolers went to Morgantown Elementary, and both those preschoolers had older siblings who did. All lived on the same side of town, the side near Thunder Rise. There was something else, too, although he wasn’t sure how much significance he should attach to it. Nightmares. Each kid had reported frequent nightmares. Probably the fevers would explain that. Kids with temps not only had nightmares but could actually hallucinate.

So could brains poisoned with certain chemicals.

“Will you call me as soon as you get the results?” Susie asked on her way out.

“Immediately,” Bostwick promised.

“Thank you, Doctor.”

For what? he wanted to say. For telling you in so many words that your kid’s slowly going down the tubes, and I don’t have a clue why? For suggesting between the lines that if somebody doesn’t come up with something soon, little Maureen McDonald could actually . . . die? And as things stand at this very moment there’s not a blessed thing we can do about it?

“You’re welcome,” he said, and again he had to avoid eye contact. He felt defeated.When she had closed the door, he picked up the phone and called the Boston headquarters of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

“Epidemiology,” he told the operator.

His question was if anything like this had been reported recently anywhere else in the state. The answer was not comforting. The answer was no.

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

LANDING PAGE for all the Free Reads during #coronavirus

Published on April 22, 2020 13:52

April 20, 2020

FREE READING! Landing page for ALL the free reads during #coronavirus

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I am regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at this time!

Previous free reads

-- Monday, April 13Not Just Traces of Me, a short storyhttps://gwaynemiller.blogspot.com/2020/04/not-just-traces-of-me.html

-- Thursday, April 16To Be Cold, Like Trees, a short storyhttps://gwaynemiller.blogspot.com/2020/04/to-be-cold-like-trees.html

-- Monday, April 20, 2020Men and Speed, a book excerpthttps://gwaynemiller.blogspot.com/2020/04/men-and-speed.html

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

Published on April 20, 2020 07:59

Men and Speed

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I will be regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at this time!

This is the third free offering: An excerpt from "Men and Speed: A Wild Ride Through NASCAR's Breakthrough Season," my sixth book (and fifth non-fiction).

Preface: Speed

Until one day in the spring of 2001, I thought I understood speed. For more than a year, I'd been traveling NASCAR's elite Winston Cup circuit, which features some of America's most exciting automobile racing. I'd experienced the sensation of racecars whizzing by at over 200 miles per hour. I'd gotten to know drivers, mechanics, and builders of cars. I'd spent many days with Jack Roush, an engineer, ex-racer, and racecar owner who had built a $250-million empire on speed. Roush raced four cars in Winston Cup competition, more than anyone. That spring day, Jack handed me the keys to one of the Stage 3 Mustang convertibles he sells on the open market. It wasn't a racecar -- but it was close, a low-slung, super-charged street machine that top ends at some 170 miles per hour and hits sixty in an astonishing 4.3 seconds. The sedan I ordinarily drove was a slug compared to it, a fact that was evident from the moment I gave it the gas. One touch and the Mustang rocketed forward, pushing me back into my seat. It felt good, and inviting: what would this car do if I put the pedal to the floor? Perhaps I would learn. I had joined Jack on an early leg of The History Channel's Great American Race, a cross-country competition involving antique cars. His new Mustang obviously couldn't enter, but Jack was sending it along as a VIP vehicle -- and he'd given me the wheel for an entire day, a trip that would take us on a winding route from Knoxville, Tennessee, to Lexington, Kentucky. Tempted though I was, I exercised caution as we started off through the morning commute. I didn't want to risk damaging Jack's car, which retails for more than $50,000 -- nor embarrass myself with a man who had won many championships. But the sun shone, the traffic thinned, and we started down a long stretch of open highway. Almost unconsciously, I began to lean into the gas, until we were doing eighty. The car handled like the proverbial dream, and I experienced a flutter inside my chest whenever I passed someone. And even if they were booking it, I passed, without a whisper of protest from Jack's 360-horsepower V-8 engine. Our route took us from highway to narrow mountain roads. This was wild country: steep inclines, precipitous ravines, deadman's curves, a place better suited to moonshining than automobiling. We came up behind one of the antique cars, traveling at a sober speed, and I backed off; the road hooked abruptly to the left, and I had only about a hundred yards of clearance. Anything could have been around that corner. "You can pass him, you know," said Jack, a twinkle in his eye. His friend, Victor Vojcek, another ex-racer, who was riding in back, agreed. I stood on the gas. We shot from twenty to sixty in about two seconds -- and blew by the old classic with room to spare. The flutter intensified to an adrenaline rush and I craved more. I was entering the zone. I had a few close calls on those mountain roads, including nearly running us into a ditch -- but instead of slowing me down, flirting with disaster produced the opposite effect. By now, I felt invincible. Other defining characteristics of my life (a wife and three dependent children, for example) had lost relevance. My world now was a cool car and blacktop, and what a glorious world it was. Late afternoon found us on the highway again: specifically, an interstate that leads into Lexington. Rush hour traffic was building. I asked Jack, who married a Kentucky woman, if the state police here were tough -- and he said they were worse than in Ohio, notorious for its speeding tickets. Deciding to be vigilant but not dawdling, I started passing again. I was back in the zone.

Suddenly, we were alongside a shiny black Pontiac Firebird -- a fast car, but surely no match for a Roush Stage 3. A man in his early twenties was driving, and he grinned over at us. Jack surmised that he was a street racer who probably had something other than an assembly-line engine under his innocent-looking hood. I only knew that when I attempted to pass, he powered up. I stood on the gas. For an instant, we led -- but the young man roared ahead. I leaned into the gas a little deeper and we took him. Back and forth, trading the lead, until we'd hit 90. I'd reached my limit. I eased off, and the young man disappeared in the traffic ahead of me. "You didn't have to let him take you," Jack said. "You had fifty horsepower on him." I was humiliated. We were about ten miles outside of Lexington now and the highway was clogged, but I silently vowed to hunt down that Firebird -- I couldn't get the image of the young man's triumphant smile as he'd zoomed away out of my head. Jack could see what I was up to, but he figured we were done. Jack was wrong. Taking chances a man of forty-seven never should, I tore through the traffic -- and there was the Firebird, on my right door. I punched the gas and we shot ahead. Caught off guard, the young man lagged -- but only momentarily. I wove through the commuters, now left, now right, the young man all the while gaining. Damn if he didn't have some kind of engine under his hood. I was totally in the zone now -- knuckles white, sweat on my forehead, the flutter in my chest a narcotic pounding. I could see with a clarity I'd never before experienced, and my reflexes were dangerously sharp -- but sound had virtually ceased, as if they'd dropped the soundtrack out of the movie. I think Jack said something about showing no mercy now, but I didn't need Jack to light the way. I punched the pedal to the floor, and we finally smoked the Firebird. The speedometer read 120, or so Jack later informed me. Thank God the Stage 3 was equipped with race brakes and race suspension -- traffic had slowed to a clot, and I was about to wreck us. I slammed on the brakes, and we came back from 120 faster than we'd gotten there, with nary a wiggle. Jack gave me a high-five, and I allowed as how you'd become a millionaire if you could bottle the feeling I had right then. I hadn't just gone fast -- I'd won, and the high of winning was more blissful than any drug. We exited the highway shortly thereafter, and as we stopped at a red light like the good citizens we were once again, the Firebird pulled up next to us. As it happened, the young man had his teenage brother along for the ride, and they both congratulated me on an excellent race. I asked if they were into NASCAR, and they said they were. But they hadn't made careful note of the man sitting beside me -- and when I introduced Jack Roush, they went crazy. "No way!" shouted the brother. "We raced Jack Roush!" said the driver. Turns out the boys liked Mark Martin, Jack's most popular Winston Cup driver. Jack invited them to follow us into downtown Lexington, where a crowd of several thousand awaited the Great American Race cars. The twenty-four-year-old driver, Jeremiah Staab, told us about his Firebird, which he had indeed configured to street race, and his eighteen-year-old brother, Jakob, let on as how he'd just graduated from high school. Jack autographed some Roush Racing hats for the boys, who lived in the hills of eastern Kentucky, and then we all posed for pictures. I was a calm and rational being once again, but I could still feel a trace of something mighty good inside my body. I later asked Jack about the effect of introducing such a substance into a young person's veins. "When the sap is high in the tree, oh man!" he said. "It's something that really drives you. It's just incredible. It spins you off into that business." Speed entices, and for the characters in this book, it proved a potent addiction from the earliest taste.

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

LANDING PAGE for all the Free Reads during #coronavirus

NEXT UP: An excerpt from my first book, "Thunder Rise: A Novel of Terror," first book in the Thunder Rise trilogy.

Published on April 20, 2020 03:51

April 13, 2020

To Be Cold, Like Trees

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I will be regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at this time!

This short story, the second free offering, is also from the collection "Since the Sky Blew Off: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, Vol. 1" It was first published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine in 1987 -- one of my first big sales -- but I daresay it has stood the test of time. Nuclear holocaust was the fear then; today, a viral equivalent...

TO BE COLD, LIKE TREESI look at the trees outside my window and I think how many centuries they have survived, how many summers they have blossomed with life, how many Septembers they have worn fire, how many winters, like this winter, they have been skeletal and cold and perfectly . . .

... content.

I look across the empty street at the factory and I remember back so long to when it was alive, to when there were workers on all three shifts, and the parking lot was full, and chimneys spewed smoke, and lunch sirens blew, and the trucks and boxcars ringed it like a fortress under siege.

Now the factory is cold, like the trees, and shadowy, like the hills beyond, and black at night except for a single light some fool leaves on in an attempt to keep the vandals away. Down the street is an antique shop, and there are desks and chairs and rusting bed frames still piled on the front porch, but it is closed, too. The windows are boarded with plywood, and the weeds are wild and thick where once there was impeccable lawn.

Only the grocery still opens for business, weekdays nine to six, Saturdays nine to noon, as it has for over a century. Of course, they're going to close that, too. Hank McArthur, whose family's run it from the start, said so himself. Told me he's keeping his stock up only through the end of black-powder season and then he's putting the for-sale sign up and moving over the mountains past the reservoir to Amherst, where, he assures me, times are better.

Why don't you come along? he said.

You could stay with me at my sister's until you find something of your own. She's got a mean tongue, Sis has, and she don't tolerate drinking, but you're no drinker anyways, so why not? You've got your Social Security and that's good anywhere a body chooses to be, so can you just tell me, why not?And I nodded my head, and said as how I would consider it, but I won't. There are still some things to do in this town. Still some whisperings I must pay attention to.

I stare at the trees tonight, and I look at the factory, and I remember something I read once in one of those glossy magazines before my eyes went bad. It was a story about how many H-bombs there are in the world today, and how many times over they could turn this planet into a radioactive graveyard, and how many people would die, and how many animals would be incinerated, and how many of God's lovely trees would be vaporized, and how long the sky would remain the color and temperature of frozen charcoal. I saw one of those bombs once.

It was lashed to an army flatbed and it was rolling through the Nevada desert in the middle of an armed convoy one Sunday evening late in 1947. I was a staff sergeant, and I was one of only a dozen guards with the necessary clearance to be out there on that range, and I had been sworn to secrecy, and I have kept that secret to this day. We hauled that thing off into the setting sun and the next morning at the crack of dawn, there was a tremendous flash followed by a mushroom cloud and a sound like the devil himself announcing the end of the earth. Five or more miles away, the sagebrush and pine were reduced to ash. Three hours ' later, we could see traces of the cloud, still faintly shaped like a mushroom from an opium-eater's dream.

And I wanted to scream, but I didn't. Not out loud.

Today is Christmas Eve.

It's almost midnight now, almost the Savior's Day, and I sit here as I have nightly since summer, when the trees were so green.

Outside, it is spitting snow. The wind is right, blowing, as it is, toward the reservoir that services two million people in a metropolitan area a hundred miles to the southeast. I suppose somewhere, probably over the hills there in Amherst, young children are dreaming their sugarplum dreams. The wind is not blowing their way, no, but toward the scientists and politicians and generals and industrialists whose existence is nourished, by nightmares.

They call me, these Vermont trees.

I sit here in my bedroom, the window open, the factory fading in and out of the snow, and they call me. I cough blood again, and my whole body shakes, and my head feels deliciously light, my stomach painfully heavy, and I wonder once more if this disease that consumes my insides began that Monday morning in 1947, or if it started later, in the bowels of that factory, where we manufactured clothing out of asbestos.

Like all the others, this is an academic issue now.

I take another sip of codeine and I feel ready.

Soon, I am going to the cellar to remove from a wall safe the lead canister that has been hidden there so long. I will put on my winter coat then and step out into the night, loading the canister onto a child's rusted wagon I happened upon near the antique shop. Pulling that wagon, I will cross the street to the factory and go inside through a back door, the one closest to the hills and the trees. After forty years, I know that door well. I will carry a flashlight and I will find my way down deep into the basement, a stuffy and fume-filled place where my little fire can get its best running start. I shall laugh at the absentee owner and his silly light, and I shall disarm the sprinklers by closing a valve the size of a grown man's skull. I will hum a nameless tune and I will pour kerosene everywhere through that rat-infested cellar and when I am ready to leave, I will drop a match. Kerosene burns slower than gas, and I will be in no rush, no rush at all.

I shall climb.

I will use the back stairway, the one where I first kissed the young mill girl who became my wife and mother of my children, both of whom were stillborn. I will probably struggle with that canister, but I will make it to the top, I am sure. I will go to the middle of the roof, the place I expect the fire to be most fierce, the smoke most thick, and I will pry the top off that canister. For the first time since 1947, I shall see plutonium dust. There is almost a pound of it, and I am not ashamed to say it was stolen by me and a long-dead man of rank who had vague hopes of someday becoming rich or famous with it.

Then I will go to the edge, six granite and iron-beam stories high, and I shall check the wind one final time to be sure it is still blowing strongly toward the reservoir.

Then I shall breathe. Deep, long breaths, hale and hearty with the raw power of the new season. At last I shall sit, staring off into trees, and I shall wait, listening to the whispers:

To be cold, like trees.To be hot, like bombs.

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction and non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

This short story, the second free offering, is also from the collection "Since the Sky Blew Off: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, Vol. 1" It was first published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine in 1987 -- one of my first big sales -- but I daresay it has stood the test of time. Nuclear holocaust was the fear then; today, a viral equivalent...

TO BE COLD, LIKE TREESI look at the trees outside my window and I think how many centuries they have survived, how many summers they have blossomed with life, how many Septembers they have worn fire, how many winters, like this winter, they have been skeletal and cold and perfectly . . .

... content.

I look across the empty street at the factory and I remember back so long to when it was alive, to when there were workers on all three shifts, and the parking lot was full, and chimneys spewed smoke, and lunch sirens blew, and the trucks and boxcars ringed it like a fortress under siege.

Now the factory is cold, like the trees, and shadowy, like the hills beyond, and black at night except for a single light some fool leaves on in an attempt to keep the vandals away. Down the street is an antique shop, and there are desks and chairs and rusting bed frames still piled on the front porch, but it is closed, too. The windows are boarded with plywood, and the weeds are wild and thick where once there was impeccable lawn.

Only the grocery still opens for business, weekdays nine to six, Saturdays nine to noon, as it has for over a century. Of course, they're going to close that, too. Hank McArthur, whose family's run it from the start, said so himself. Told me he's keeping his stock up only through the end of black-powder season and then he's putting the for-sale sign up and moving over the mountains past the reservoir to Amherst, where, he assures me, times are better.

Why don't you come along? he said.

You could stay with me at my sister's until you find something of your own. She's got a mean tongue, Sis has, and she don't tolerate drinking, but you're no drinker anyways, so why not? You've got your Social Security and that's good anywhere a body chooses to be, so can you just tell me, why not?And I nodded my head, and said as how I would consider it, but I won't. There are still some things to do in this town. Still some whisperings I must pay attention to.

I stare at the trees tonight, and I look at the factory, and I remember something I read once in one of those glossy magazines before my eyes went bad. It was a story about how many H-bombs there are in the world today, and how many times over they could turn this planet into a radioactive graveyard, and how many people would die, and how many animals would be incinerated, and how many of God's lovely trees would be vaporized, and how long the sky would remain the color and temperature of frozen charcoal. I saw one of those bombs once.

It was lashed to an army flatbed and it was rolling through the Nevada desert in the middle of an armed convoy one Sunday evening late in 1947. I was a staff sergeant, and I was one of only a dozen guards with the necessary clearance to be out there on that range, and I had been sworn to secrecy, and I have kept that secret to this day. We hauled that thing off into the setting sun and the next morning at the crack of dawn, there was a tremendous flash followed by a mushroom cloud and a sound like the devil himself announcing the end of the earth. Five or more miles away, the sagebrush and pine were reduced to ash. Three hours ' later, we could see traces of the cloud, still faintly shaped like a mushroom from an opium-eater's dream.

And I wanted to scream, but I didn't. Not out loud.

Today is Christmas Eve.

It's almost midnight now, almost the Savior's Day, and I sit here as I have nightly since summer, when the trees were so green.

Outside, it is spitting snow. The wind is right, blowing, as it is, toward the reservoir that services two million people in a metropolitan area a hundred miles to the southeast. I suppose somewhere, probably over the hills there in Amherst, young children are dreaming their sugarplum dreams. The wind is not blowing their way, no, but toward the scientists and politicians and generals and industrialists whose existence is nourished, by nightmares.

They call me, these Vermont trees.

I sit here in my bedroom, the window open, the factory fading in and out of the snow, and they call me. I cough blood again, and my whole body shakes, and my head feels deliciously light, my stomach painfully heavy, and I wonder once more if this disease that consumes my insides began that Monday morning in 1947, or if it started later, in the bowels of that factory, where we manufactured clothing out of asbestos.

Like all the others, this is an academic issue now.

I take another sip of codeine and I feel ready.

Soon, I am going to the cellar to remove from a wall safe the lead canister that has been hidden there so long. I will put on my winter coat then and step out into the night, loading the canister onto a child's rusted wagon I happened upon near the antique shop. Pulling that wagon, I will cross the street to the factory and go inside through a back door, the one closest to the hills and the trees. After forty years, I know that door well. I will carry a flashlight and I will find my way down deep into the basement, a stuffy and fume-filled place where my little fire can get its best running start. I shall laugh at the absentee owner and his silly light, and I shall disarm the sprinklers by closing a valve the size of a grown man's skull. I will hum a nameless tune and I will pour kerosene everywhere through that rat-infested cellar and when I am ready to leave, I will drop a match. Kerosene burns slower than gas, and I will be in no rush, no rush at all.

I shall climb.

I will use the back stairway, the one where I first kissed the young mill girl who became my wife and mother of my children, both of whom were stillborn. I will probably struggle with that canister, but I will make it to the top, I am sure. I will go to the middle of the roof, the place I expect the fire to be most fierce, the smoke most thick, and I will pry the top off that canister. For the first time since 1947, I shall see plutonium dust. There is almost a pound of it, and I am not ashamed to say it was stolen by me and a long-dead man of rank who had vague hopes of someday becoming rich or famous with it.

Then I will go to the edge, six granite and iron-beam stories high, and I shall check the wind one final time to be sure it is still blowing strongly toward the reservoir.

Then I shall breathe. Deep, long breaths, hale and hearty with the raw power of the new season. At last I shall sit, staring off into trees, and I shall wait, listening to the whispers:

To be cold, like trees.To be hot, like bombs.

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction and non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

Published on April 13, 2020 14:09

April 11, 2020

Not Just Traces of Me

STAY TUNED, updating soon...

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I will be regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! (And if you'd like to purchase any of my collections and books, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)This short story is from the collectionNOT JUST TRACES OF MEHe remembered it so well. The bridge over the bay. The shipyard, quiet and empty at this hour. The clam shack, plywooded until spring. The turn into park. The access road, freshly plowed. And the pines trees. A wall of pine, blocking his view of the ocean. But he could hear it. He drove with the window down, and he could hear it, boiling and swirling against the rocks.

"This is where I will be," she had said. "Not just traces of me, but me. Me, Donny. Me."

On down the road, passing no one, the radio off. Past the refreshment stand to the edge of the parking lot, buried in white drifts. Stopping the car, silencing the engine, getting out and standing, his breath enveloping him like steam. A cloudless sky, full of stars, and dominated by a frozen moon. Starting toward the beach, his footsteps puncturing the crusty snow with a sound like eggshells being crushed.He remembered.The two of them, there between the rocks, newly met, crazy in love. Kissing, and whispering, and then his hand under her suit, and then both of them unable to wait, stripping, making desperate love that leaves their bodies shaking and soaked in sweat.Summer, and no end to time, no beginning, just him with her on a deserted beach on the sun-drenched coast of Maine."This is where I will be," she said that first they when they had dressed, and were moving arm-in-arm back to her car."I will linger here for you."He walked.The sound of the ocean, louder, angrier as if battered the granite rocks, laminated with icy spray. Out of the parking lot and onto the boardwalk, which the wind had swept of snow. Closer now. Through the dunes, the beach plums bearing last autumn's shriveled fruit. Stepping onto sand. Stepping over dead crabs. Driftwood. A rotted can. Tangles of seaweed, spit out by the cleansing surf. South, to where the rocks began. Climbing now, the ocean pounding in his ears. Over the ridge and down to sand again.It was her theory.He never expected to have to test it. He expected them to go on forever. Jokingly, she called it the Theory of Endurability, a play on Einstein’s words. She did not laugh at the concept. It was impossible to scientifically prove, of course. You either believed it or you didn't. She did. She said she felt it in her soul. She said it was a part of nature, the most mysterious part. She said that an echo of every event lingers forever in the places where it occurs. Visit a battlefield, she said, and if you are patient – if you will give them their chance – you will feel the soldiers. You will hear their weapons, smell their gunpowder, see their dead and their dying. Every detail of the battle, no matter how insignificant or long ago, still lingering. Still faintly echoing, on and on through eternity, like light from a star a billion light years away.It wasn't only a function of war, she'd explained. Wasn't only a function of tragedy, although tragedy almost certainly left the stronger imprint. Every conversation, every handshake, every walk through a park, every plunge into a pool, every baby's smile, every mother's hug, every lover's summertime kiss on the sun-drenched coast of Maine – echoes of it all, lingering forever, like some kind of metaphysical fingerprint that cannot be erased.This was their beach.It had been four years, a very different season, but he was sure of it. "Our place," she'd called it. Rocks to both sides, and tucked in there between, a sliver of bleached sand. Such a secluded spot. Where he had had her that very first time, had her with no blanket, just him on her on sand, their hearts exploding out of their ribcages. He closed his eyes and he could see her, just as she'd promised, could feel her engine-hot body, the incredible taste of salt on her skin, his mind and his senses crazy all over again. In his trousers, his masculinity stirred, and it was as if she was really there, opening herself to him, glisteningDo not wait.She'd come to him nightly in his dreams the last two weeks – the last two weeks of December – and that, only that. had been her message.You know where I will be.And then her final words, just last night, only hours before beginning his drive east from Chicago, where he'd settled after her drowning.I want you, Donny. I want you now.He was at water's edge.The waves foamed at his feet, soaking his boots. Ahead, the ocean. To both sides, the rocks.Above, moon and so many millions of stars, impossible to count.He started with his gloves. His wool cap. Then his coat. One arm, then the other, folding it and placing it in a careful bundle on the beach. He took his watch and tossed it ahead of him, into the water, black and noisily restless . Only once had she indicated it was possible to be more than a trace.You could exist like that forever, she'd said, but only if you plan ahead.He unbuttoned his shirt and dropped it to the sand. The wind caught it, whipping it along the beach until it snagged on rocks. He felt that wind on his bare chest. It had an edge like a blade, but he did not mind. Did not notice. Everything he was feeling now was concentrated lower in his body. He stooped to get at his boots. His fingers already were beginning to numb, and he had difficulty with the laces, but eventually he loosened them. His socks. His belt. His fly. His trousers falling down around his ankles in a heap.He stepped out. Now he saw her, a hundred yards out, dancing just above the waves, the moon casting silvery shadows across the whitecaps.I love you with all of my heart, she'd said the last time he saw her. I will love you forever.He walked seaward, deeper and deeper, eager for her embrace.

Published on April 11, 2020 07:05

February 23, 2020

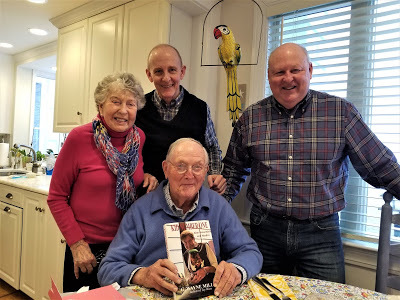

Starting 9th year of Story in the Public Square (And, yes, we love telling our origins story. Hey, we ARE storytellers!)

Eight years ago today, on February 23, 2012, I joined Jim Ludes for coffee in a shop in downtown Newport, Rhode Island. I had met Jim the previous October 16, 2011, when, as the newly arrived (from Washington) director of the Pell Center at Salve Regina University, he had kindly hosted the launch singing and reception for my biography of Claiborne Pell, “An Uncommon Man: The Life and Times of Senator Claiborne Pell.” The event, at the Pell Center on Bellevue Avenue, was a fine success. Kristine Hendrickson, Salve’s Associate Vice President University Relations/CCO, also came for that coffee. She, too, had been instrumental in the Pell bio launch.

Full house at the "An Uncommon Man" launch party.

Full house at the "An Uncommon Man" launch party.

During the hour or so that we met for coffee that winter day, Jim discussed his ideas for building the Pell Center into a robust place, what he now describes thusly: “The Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy's programs are designed to generate new ideas, to expand public understanding of important issues and, ultimately, to help the public and its leaders make better decisions. Working with students and faculty, we don't just study the world, we try to change it.”

I, in turn, discussed my desire to extend my storytelling into the academic world.

Seemed like a good fit.

And so Story in the Public Square was born.

Within a few months, we had formed a partnership between the Pell Center and The Providence Journal, where I was and still am a staff writer. I was named a visiting fellow and director of Story in the Public Square, and Jim and I -- with Office and Events Manager Teresa Haas, then-communications assistant Mia Lupo, and some Salve work-study students -- got down to work. We had the full support of the great Sister Jane Gerety, who retired last year after a decade as Salve president. Her successor, Dr. Kelli J. Armstrong, has been equally supportive. Thanks to both presidents!

One of the first Story events was an address I gave on May 16, 2012, to the 2012 Pell Scholars. Sister Jane was present at the dinner, as was Nuala Pell, Claiborne’s widow.

©Marianne Lee / Courtesy of Salve Regina University The 2012 Pell Scholars, with Mrs. Nuala Pell, center; me, behind her; and Dr. Khalil Habib, director of the Pell Honors Program and philosophy professor at Salve Regina University, right rear.

©Marianne Lee / Courtesy of Salve Regina University The 2012 Pell Scholars, with Mrs. Nuala Pell, center; me, behind her; and Dr. Khalil Habib, director of the Pell Honors Program and philosophy professor at Salve Regina University, right rear.

That October, I spent a week in residence at the Pell Center as visiting fellow. The next week, we opened a Twitter account, @pubstory. A web site and Facebook page followed, along with a Wikipedia page. We did not, at that point, have even a whisper of a clue that one day we would have a national PBS/SiriusXM Radio show, our own YouTube Channel, podcasts and more...

On November 17, 2012, I gave my first public address for Story, "Where Stories Take Us." In january 2013, we received our first major grant, from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. And on On March 3, 2013, we spelled out our foundational philosophy: Public Story = Policy Change. Which means, we wrote, “Storytelling can powerfully influence how people collectively think and act.” We traced the roots of storytelling to prehistoric peoples: Story, we declared, is hardwired into the human species.

Magura Cave, Bulgaria

Magura Cave, Bulgaria

On Friday, April 12, 2013, we staged our first major public event: a day-long conference featuring Gary Hart as keynote speaker and Dana Priest receiving the inaugural Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square. Plus, a great panel of storytellers.

Jim Ludes, me, Dana Priest, and Sr. Jane Gerety.

Jim Ludes, me, Dana Priest, and Sr. Jane Gerety.

Hart: "We need stories to tell us where we are [and] where we are headed."

Hart: "We need stories to tell us where we are [and] where we are headed."

L to R: Moderator Karen Bordeleau, executive editor of The Journal; novelist

L to R: Moderator Karen Bordeleau, executive editor of The Journal; novelist

Karen Thompson Walker; BU professor Chris Daly; URI political scientist

Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz; WBUR's David Boeri; and the NAACP's Jim Vincent.

A year later, on April 11, 2014, we staged our second Story conference. The theme was "Moving Images" -- screen storytelling in its many forms, including Hollywood, animation, short-form documentary, TV and long-form documentary. The Emmy-winning actors, screenwriter, producer and creator Danny Strong received the Second annual Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square, and other prominent screen storytellers spoke to another sellout audience: Jim Taricani, founder of Rhode Island NBC Channel 10’s celebrated I-Team; Kendall Moore, associate professor of journalism and film media at the University of Rhode Island and an award-winning documentary filmmaker; Agnieszka Woznicka, animation artist and associate professor at the Rhode Island School of Design; and Teja Arboleda, another award-winning documentarian, writer and educator.

Sister Jane and Danny Strong.New York Times best-selling author Lisa Genova received the third annual Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square in a ceremony at the Pell Center on June 4, 2015.

Sister Jane and Danny Strong.New York Times best-selling author Lisa Genova received the third annual Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square in a ceremony at the Pell Center on June 4, 2015.

Lisa Genova accepts the Pell Prize. In an experiment that paved the way for our weekly TV/SiriusXM show, we taped Lisa at the Pell Center. A wonderful learning experience that led Jim and me to decide, that fall, to try TV -- in a TV studio, not a wing of the Pell Center, where ambient sound and other factors beyond our control interfered with the business at hand. The episode was never shown or aired -- but, as noted, we learned! (And Lisa, being a good sport, will return to Rhode Island to tape an episode of our show -- in our studio at our flagship station, more on that studio and station further into this post...)

Lisa Genova accepts the Pell Prize. In an experiment that paved the way for our weekly TV/SiriusXM show, we taped Lisa at the Pell Center. A wonderful learning experience that led Jim and me to decide, that fall, to try TV -- in a TV studio, not a wing of the Pell Center, where ambient sound and other factors beyond our control interfered with the business at hand. The episode was never shown or aired -- but, as noted, we learned! (And Lisa, being a good sport, will return to Rhode Island to tape an episode of our show -- in our studio at our flagship station, more on that studio and station further into this post...)

Lisa Genova, right, goes before the cameras.

Lisa Genova, right, goes before the cameras.

Not strictly a Story event, the November 1, 2015, launch of my book "Car Crazy: The Battle for Supremacy Between Ford and Olds and the Dawn of the Automobile Age" at the Pell Center brought more attention to the Story program. AND, was a return to the scene of the crime, so to speak. Not to mention a really fun day with really old antique cars. Four were on hand, courtesy of Ambassador Bill Middendorf and the Audrain Automobile Museum: a 1904 Oldsmobile, 1912 Model T Speedster, 1912 Packard and 1893 Duryea: Watch them in action on YouTube. Also on hand was a crew from C-SPAN BOOK TV, which taped the event: Watch it here.

The talk. Longtime friend and screenwriting partner Drew Smith, center.

The talk. Longtime friend and screenwriting partner Drew Smith, center.

Drew travelled from California to join us!

My wonderful wife, Yolanda, and me on a 1904 Olds.

My wonderful wife, Yolanda, and me on a 1904 Olds.

Those conversations Jim and I had about moving toward TV reached early fruition in early 2016, when Llewellyn King, host with his wife, Linda Gasparello, of the national show "White House Chronicle" graciously gave us a monthly episode, shot on their set at Rhode Island PBS. Our first show, "A New Partnership for White House Chronicle," broadcast three years ago this month, introduced Story to a much wider audience. Watch that inaugural episode here.

Llewellyn King on our maiden show.

Llewellyn King on our maiden show.

Jim, me, Linda and Llewellyn.After that explainer introductory show, we featured author August Cole; Dan Barry, Pulitzer prize-winning New York Times staff writer and best-selling author; Tricia Rose, Brown University professor of Africana Studies and director of Brown's Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America; Hasbro CEO and chairman Brian Goldner; 2016 Pell Prize winner Javier Manzano, photographer and filmmaker; Raina Kelley, managing editor of ESPN's "The Undefeated"; Emmy-winning broadcast journalist David Shuster; and Adam Zyglis, Pulitzer-winning editorial cartoonist. These eight episodes from 2016 can be viewed here.

Jim, me, Linda and Llewellyn.After that explainer introductory show, we featured author August Cole; Dan Barry, Pulitzer prize-winning New York Times staff writer and best-selling author; Tricia Rose, Brown University professor of Africana Studies and director of Brown's Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America; Hasbro CEO and chairman Brian Goldner; 2016 Pell Prize winner Javier Manzano, photographer and filmmaker; Raina Kelley, managing editor of ESPN's "The Undefeated"; Emmy-winning broadcast journalist David Shuster; and Adam Zyglis, Pulitzer-winning editorial cartoonist. These eight episodes from 2016 can be viewed here.

An early "class photo," of 2016 guests Javier Manzano and Raina Kelley with Jim, me and David Marseglia, who played a vital role in launching our show. The "class photo" has become a fixture of the proceedings. Gianna Gerace took this one.

An early "class photo," of 2016 guests Javier Manzano and Raina Kelley with Jim, me and David Marseglia, who played a vital role in launching our show. The "class photo" has become a fixture of the proceedings. Gianna Gerace took this one.

How could we NOT turn the tables and have Javier shoot us?! Joining us were

How could we NOT turn the tables and have Javier shoot us?! Joining us were

Allison Barbera, second from left, and Teresa Haas, second from right.

That was the original set. We replaced it, but the off- (and on-) camera fun never went away. Here, Javier was game.

That was the original set. We replaced it, but the off- (and on-) camera fun never went away. Here, Javier was game.

So have been many of our guests -- when appropriate, of course.

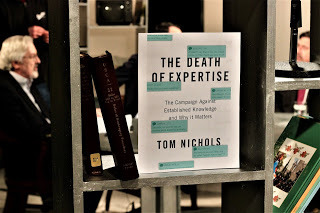

And then we took the plunge, working with the fabulous folks at Rhode Island PBS to create, produce and broadcast what is now the weekly Story in the Public Square. We had a consultant custom-design and build a set, we hire the enormously talented Allison Barbera and her team to provide makeup and hair service, and after little (actually, no) rehearsal, Jim and I on January 3, 2017, sat behind it and welcomed our first three guests -- author and professor Tom Nichols, and Native Americans Loren Spears and Christian Hopkins -- for two separate shows that aired only on RI PBS and SiriusXM Satellite Radio -- a southeastern New England TV market, and an international radio one. By this point, Gianna Gerace was handling communications.

Scenes from that first day below -- or if you prefer, watch a behind-the-scenes video I shot and cut.

Loren Spears, center; Christian Hopkins, standing behind her.

Loren Spears, center; Christian Hopkins, standing behind her.

Tom Nichols, right, as taping is set to begin.

Tom Nichols, right, as taping is set to begin.

Jen Bates was in charge of looks on Day One.

Jen Bates was in charge of looks on Day One.

When she wasn't shooting stills, Gianna was running the social media.

When she wasn't shooting stills, Gianna was running the social media.

Andy Gannon and Jen grooming Jim.

Andy Gannon and Jen grooming Jim.

Nick Moraites checked the cameras. Today, he is our ace editor.

Nick Moraites checked the cameras. Today, he is our ace editor.

Our first director, Scott Saracen, readied the control room.

Our first director, Scott Saracen, readied the control room.

So that began the bigger story of Story in the Public Square. It grew in 2017, when the masterful Erin Demers succeeded Gianna and I began writing an occasional column for The Journal, "Inside Story," and in September 2018, we went national. Meanwhile, we began to podcast the show on several popular channels. We continued to name a Story of the Year. And we continued to award the Pell Prize: After Dana Priest, Danny Strong , Lisa Genova and Javier Manzano came Oscar-nominated filmmaker Daphne Matziaraki in 2017 and Dan Barry in 2018. The seventh honoree, Elizabeth Kolbert,

Erin Demers, with some of our crew. That's Mark Smith pointing at Scott!When Erin Demers left, she was succeeded by Erin Barry, who has done a superior job, too!

Erin Demers, with some of our crew. That's Mark Smith pointing at Scott!When Erin Demers left, she was succeeded by Erin Barry, who has done a superior job, too!

Erin Barry, third from right, with crew and director Cherie O'Rourke,

Erin Barry, third from right, with crew and director Cherie O'Rourke,

third from left, and guest Susan Rice, center.So thanks to our Pell Center staff, our RI PBS crew, Allison and Jen, and a roster of extraordinary guests -- more than 150 now -- we are now a national show, seen coast-to coast in most major markets. We also delight in having students and other visitors join us for tapings and meet-and-greets in the Green Room.

Reading across Rhode Island: Guest Elizabeth Rush, seated, with teachers

Reading across Rhode Island: Guest Elizabeth Rush, seated, with teachers

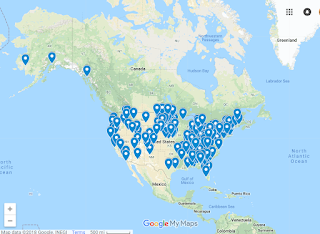

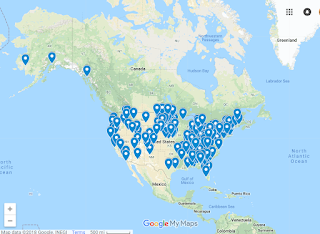

and students from Juanita Sanchez Educational Complex, Providence.We have won two Telly Awards. We have another remarkable lineup for 2020. Broadcast episodes can be viewed here. And you can find your local station and broadcast times here.

We had only a few ideas and a lot of enthusiasm when we started eight years ago. The ideas have grown, but the enthusiasm has never faded. Happy birthday, Story. Here's to many more!

Full house at the "An Uncommon Man" launch party.

Full house at the "An Uncommon Man" launch party.During the hour or so that we met for coffee that winter day, Jim discussed his ideas for building the Pell Center into a robust place, what he now describes thusly: “The Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy's programs are designed to generate new ideas, to expand public understanding of important issues and, ultimately, to help the public and its leaders make better decisions. Working with students and faculty, we don't just study the world, we try to change it.”

I, in turn, discussed my desire to extend my storytelling into the academic world.

Seemed like a good fit.

And so Story in the Public Square was born.

Within a few months, we had formed a partnership between the Pell Center and The Providence Journal, where I was and still am a staff writer. I was named a visiting fellow and director of Story in the Public Square, and Jim and I -- with Office and Events Manager Teresa Haas, then-communications assistant Mia Lupo, and some Salve work-study students -- got down to work. We had the full support of the great Sister Jane Gerety, who retired last year after a decade as Salve president. Her successor, Dr. Kelli J. Armstrong, has been equally supportive. Thanks to both presidents!

One of the first Story events was an address I gave on May 16, 2012, to the 2012 Pell Scholars. Sister Jane was present at the dinner, as was Nuala Pell, Claiborne’s widow.

©Marianne Lee / Courtesy of Salve Regina University The 2012 Pell Scholars, with Mrs. Nuala Pell, center; me, behind her; and Dr. Khalil Habib, director of the Pell Honors Program and philosophy professor at Salve Regina University, right rear.

©Marianne Lee / Courtesy of Salve Regina University The 2012 Pell Scholars, with Mrs. Nuala Pell, center; me, behind her; and Dr. Khalil Habib, director of the Pell Honors Program and philosophy professor at Salve Regina University, right rear.That October, I spent a week in residence at the Pell Center as visiting fellow. The next week, we opened a Twitter account, @pubstory. A web site and Facebook page followed, along with a Wikipedia page. We did not, at that point, have even a whisper of a clue that one day we would have a national PBS/SiriusXM Radio show, our own YouTube Channel, podcasts and more...

On November 17, 2012, I gave my first public address for Story, "Where Stories Take Us." In january 2013, we received our first major grant, from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. And on On March 3, 2013, we spelled out our foundational philosophy: Public Story = Policy Change. Which means, we wrote, “Storytelling can powerfully influence how people collectively think and act.” We traced the roots of storytelling to prehistoric peoples: Story, we declared, is hardwired into the human species.

Magura Cave, Bulgaria

Magura Cave, BulgariaOn Friday, April 12, 2013, we staged our first major public event: a day-long conference featuring Gary Hart as keynote speaker and Dana Priest receiving the inaugural Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square. Plus, a great panel of storytellers.

Jim Ludes, me, Dana Priest, and Sr. Jane Gerety.

Jim Ludes, me, Dana Priest, and Sr. Jane Gerety.  Hart: "We need stories to tell us where we are [and] where we are headed."

Hart: "We need stories to tell us where we are [and] where we are headed."  L to R: Moderator Karen Bordeleau, executive editor of The Journal; novelist

L to R: Moderator Karen Bordeleau, executive editor of The Journal; novelistKaren Thompson Walker; BU professor Chris Daly; URI political scientist