G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 8

October 15, 2020

On a return to a hometown, a reunion with a first love

On the run from the law nd deep into his journey into the past, Mark Gray, the protagonist of "Blue Hill," returns to his home town, where he meets Sally Martin, his high-school girlfriend and first love. A long-buried secret will soon be revealed.

To learn more about the book, which published on October 6 - and to order in audio, Kindle or paper formats - visit http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

We both cracked up at that, and the laughter opened something, because our conversation was suddenly animated. I heard details of Sally’s divorce from a small-town cop who was a decent enough dad but couldn’t keep his hands off other women. I talked about Ruth and Timmy, albeit without details of his paternity, and I took a gratifying shot at old Syd. Sally told of bumping into my dad now and again; of her job in a nursing home, low-paying but rewarding helping others like that, she said; of our first-grade teacher, Miss Biddle, who’d died last winter; of Jane Rogers, who’d married at 19 and was now, could you believe it, a grandmother.

I told Sally of how I’d always hoped to move back here, or at least have a summer place. It was not the complete truth, but somehow it was the right thing to say.

“You’re wearing Old Spice,” Sally said when we reached a lull.

It was almost dark now.

“Is it too strong?”

“No. I’m just surprised you remembered.”

“I remember a lot.”

“So do I.”

I looked seaward, at waves that had turned Blue Hill Bay angry. Further out, the unprotected ocean would be treacherous. On nights like this, my father always offered a prayer for mariners; when she was alive, Mom always joined in. Her grandfather, the guy who’d bought Blue Hill’s blueberry fields from a Native American for a dollar, had been lost at sea on a night like this. His body had never been recovered, which meant no funeral or grave to ever visit.

“Can I ask you something?” Sally said.

“Anything you want.”

“Why’d you call?”

I’d been expecting that question. I still didn’t have the answer.

“I found the ring,” I explained, “going through your letters.”

I dug into my pocket and offered it to Sally, but she wouldn’t take it.

Suddenly, the circumstances of our last encounter were with us—heavy and low, and nasty, like the clouds.

You stupid fuck,I thought. What possessed you to do that?

“I want you to have it,” I said, struggling.

“Why?”

“Because it’s yours.”

“Was mine.”

“Please?”

Sally took the ring, but she wouldn’t wear it. Rather, she slipped it into her pocket.

“Things didn’t turn out like we planned, did they?” I said, and that sentence sounds monumentally stupid now, but then—then, it seemed profound.

“They never do,” Sally said. “The older you get, you learn that. And when you do, you reach a place of peace.”

A place of peace.

How I envied her, this girl who’d become this woman.

We left the beach and climbed quite some distance, to the top of a granite ledge bordered by pines. The wind was stronger here and I wished I had gloves and hat, as Sally did.

“Do you remember this ledge?” I said.

“Of course.”

“We used to fish off here when the tide was high. What were we in—fourth grade?”

“Something like that.”

“Mom was always afraid we’d fall.”

“Mothers are like that. I remember the time you told me about sharks that could crawl out of the ocean. I really believed you, for a while.”

“I think that was the beginning of my infantile practical jokes.”

“I wouldn’t call them infantile,” Sally said. “Sophomoric, maybe.”

We laughed.

“I have other memories of here,” I said.

“One stronger than the rest,” Sally said.

“Graduation night.”

“It seems like a million years ago.”

“Maybe it was,” I said. “Maybe everything went into a time warp and here we are, back again.”

I know—that sounds stupider than my last stupid comment. But if Sally took it that way, she didn’t let on.

Moving closer to her, I smelled Shalimar perfume, always her favorite; in one of those inexplicably weird coincidences, it was Ruth’s, too. I thought I also smelled whiskey, but I couldn’t be sure.

I wanted to kiss Sally and feel the swell of her breasts. I wanted it to be summer, and sunrise, over a flat blue sea.

“We better go,” Sally said, “before it’s completely dark.”

She squeezed my hand, fleetingly.

“You’re right,” I said.

“We wouldn’t want to get stranded here. Not with a storm coming on.”

“No,” I said, “not with a storm coming on.”

We walked in silence until we got to our cars.

“Well,” I said, “I guess this is it.”

“Where do you go now?” Sally asked.

“Maybe my father’s,” I said. “Maybe the Blue Hill Inn. I’m not sure I’m quite ready for Dad yet.”

“But you will see him before he goes.”

That seemed important to her.

“Of course,” I said.

“Since you don’t have plans,” Sally said, “would you like to have dinner?”

“I’d love to,” I said, too eagerly.

“I’ll even cook,” Sally said.

It had been an old joke, how she had trouble boiling water.

“You don’t have to go to that bother,” I said.

“I want to. Just don’t expect any of that gourmet stuff you get at home.”

“Are you kidding?” I said. “We live on macaroni and cheese. It’s Timmy’s favorite.

“Then maybe I have a chance.”

“What about your kids?”

“They’re with their father,” Sally said, “until tomorrow night.”

“You’re sure it wouldn’t be a bother?” I said.

“Do you think I would have asked if it was? Take your car. You can follow me.”

October 11, 2020

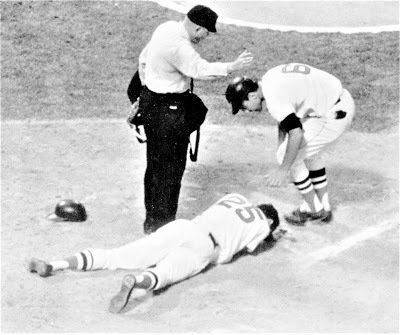

Fenway Park on August 18, 1967: Tony Conigliaro struck by pitch.

Mark Gray, the protagonist of "Blue Hill," is a young Red Sox fan when slugger Tony Conigliaro is beaned by a pitch during the Sox "Dream Team" of 1967. The pitch changed the real-life Tony C. -- and had a profound impact on the fictional protagonist of my new novel.

To learn more about the book, which published on October 6 - and to order in audio, Kindle or paper formats - visit http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

I close my eyes and I can see the sun setting over Fenway,can feel my hand inside my glove, a Wilson that Mom gave me for my ninth birthday. I hear Dad, happy for the first time since Mom took sick, explaining with uncharacteristic enthusiasm why the bleachers are the statistically proven best place to catch a Tony Conigliaro home run because of how he pulls the ball—nothing, of course, about how the bleachers are all we can afford. I didn’t come to that realization until much later.

“Today’s the day, Mark,” he said, “I feel it.”

I said: “Does He feel it, too?”

And Dad saying impishly: “Who—the Big Guy?”

This was Dad at his wickedest—you knew he’d be good for an extra Coke, a day like this.

“Yeah, the Big Guy,” I said.

“Oh, yes, He feels it, too,” Dad said. “I can tell, because we’ve been doing a lot of talking lately.”

Talk was what Dad called prayer, when explaining it to little kids.

Even if you’re only marginally into baseball, you know where this one goes.

Jack Hamilton was pitching for the California Angels when Tony C. came to bat. I had Dad’s binoculars and I followed Conigliaro as he left the warmup circle. The first ball was a strike. Conigliaro fouled the second off behind first base. The next pitch, a fast ball, caught Conigliaro in the left cheekbone. I heard it—I swear I did, three hundred and seventy-nine feet away—a sound like a hammer on wood.

Tony C. fell.

Fenway Park on August 18, 1967.

Fenway Park on August 18, 1967.The crowd went silent, and Fenway Park suddenly seemed frighteningly huge, and then the woman next to me began to cry.

She was a woman like Lisa: pretty, ponytailed, dressed in cut-offs and a tee shirt with Tony C.’s number. I remember having stared at her breasts when she wasn’t looking—how I saw Dad sneaking a look, too. I remember her telling me how she went every weekend to the club where Tony C. hung out. I remember the smell of the baby oil she rubbed onto her arms and legs, tanned to bronze, like Bridget Bardot, whose picture I’d secretly cut from a Look magazine from the library. I was a boy, discovering, awkwardly like all of us, sexuality.

I remembered all that and could not but wonder, sitting there at Fenway now with my own son more than thirty years later, where she was now and did she still feel good enough about herself to tan or did she heed the emerging warnings about skin cancer, and was she a grandmother—and did she have even the faintest memory of the boy sitting next to her that day.

I didn’t cry, at first.

I knew that any second, Tony C. would get up, brush himself off and take first base, and the next time he faced Hamilton, he would send his darn beanball all the way to Kenmore Square. Yaz would knock one out, too, and maybe George Scott also for good measure, and that would teach the Angels a thing or two about messing with the man.

But Tony C. didn’t get up.

He lay in the dirt, motionless, as men in white rushed out with a stretcher.

I started to cry then. Dad talked soothingly and held my hand, and when I didn’t stop, he led me out to Landsdowne Street. I didn’t know, of course, that he’d already decided I would never play baseball again, or that the tumor inside Mom would kill her before New Year’s Day.

October 9, 2020

The possibility of reconciliation, and an outrageous climb in a Maine Nor'easter. An excerpt from "Blue Hill."

Mark Gray, the protagonist of "Blue Hill," is the son of a now-retired Episcopal priest and '60s social activist. Their relationship has been difficult since Gray's childhood, but there is always the possibility of reconciliation. Maybe it will occur when Gray, now one of America's Most Wanted criminals, visits his elderly father, who lives in Blue Hill, Gray's hometown, and proposes an outrageous climb of a favorite mountain... in a raging Nor'easter. Read the excerpt here.

To learn more about the book, which published on October 6 - and to order in audio, Kindle or paper formats - visit http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

The real Mount Blue, near Blue Hill, Maine.

The real Mount Blue, near Blue Hill, Maine.My eye traveled to Mom’s piano: an ancient Kimball uprightthat had been handed down from her grandmother. Mom always dreamed of owning a baby grand, but she never complained that circumstances did not allow her one. What she did was put a pickle jar on the mantel and squirrel away spare change, pennies and nickels, mostly, for her “Steinway Fund,” as she called it. She died before it was full. Dad used what was there to buy her tombstone.

We sat in silence then, for I don’t know how long. I finished my brandy and Dad his and he poured us another. We’d never shared a drink before, never mind two.

“Go on,” he urged, “it’ll fortify you.”

“For what?”

“For climbing Blue Hill.”

I thought he was kidding, or drunk.

But to my knowledge, Dad had never been drunk, and he wasn’t acting it now. He didn’t sound demented. He sounded resolute, as if he’d pondered this a long time.

And there was no mistaking his eyes. They were as steely as the day IRS agents led him out of Saint Luke’s in handcuffs while a photographer for the Bangor Daily News snapped away.

“You’re kidding,” I said.

“No, I’m not,” he said.’

“It’s a blizzard out there.”

“City living’s spoiling you,” Dad said, smiling. “What this is is a good old Downeaster, no more, no less. Now, I intend to climb Blue Hill. If you won’t accompany me—well, I guess I’ll have no choice but to go it alone.”

We parked at the base of the mountain. Dad struggled leaving the car and I doubted he’d have been able to get out if I hadn’t helped him.

“This is worse than when we left the house,” I said as Dad got his balance.

“Maybe to a city slicker.”

“This is crazy.”

“You’ve more than made your point,” Dad said. “Now let’s go—the day’s getting away from us. Don’t lock your doors, I’m afraid the locks will freeze.”

We made respectable progress the first few hundred yards, a stretch that is gently sloped. Dad walked unassisted and the pines surrounding us broke the wind and the snow hadn’t drifted much, was only a smooth three or four inches deep. We nipped from a flask Dad had filled with his brandy and we were determined in our silence.

It was one-thirty on the kind of wintry afternoon when night is impatient to fall.

A bit further, we hit a deadfall.

Dad tried getting over it by himself, but it was too much—even he conceded that after a clumsy try that left him sputtering. I straddled the trunk and as Dad swung his body over, I bore his weight. He was thinner than I remembered and I thought, although it was probably only my imagination, that I could feel the brittleness of his bones.

“Damn arthritis,” he said, then added: “Don’t take that to mean I want to turn back. This is actually easier than I expected.”

A bit further still, we were on an open stretch of mountain. The wind had blown the snow deeper than two feet in places and knocked down pines. A ranger would have had trouble getting through.

“I don’t know, Dad,” I said.

“It gets easier past here,” he declared.

“How do you know?”

“The Big Guy told me,” Dad said.

I grinned, but he didn’t; he really meant it.

“Let’s take a five-minute breather,” he went on, “then give it all we’ve got. We’ll make the top by three.”

We took shelter behind a boulder. Dad drank from his flask.

I wanted to tell him that alcohol and sub-freezing temperatures were a deadly mix, but he’d had his fill of my observations so I didn’t. His face was flush, whether from effort or wind or both I could not tell, but I didn’t mention that, either. I didn’t tell him how worried I was that his gloves, and mine, were soaked. I listened to the wind and it sounded like the wildcats I always imagined awaited us on our family climbs more than three decades ago.

The snow was so heavy that I did not notice, until Dad was set to push off again, that just beyond this boulder was the path leading to Mom’s grandfather’s blueberry field.

I lost my grip bringing Dad over the last deadfall and he surely would have broken his hip if the drift hadn’t cushioned his fall. I said nothing and neither did Dad, but his face showed pain. He put his arm around my waist, and we hobbled on, under a canopy of pines that was strangely still and unblanketed with snow.

Ten minutes more, we reached the summit.

“After all I’ve given Him,” Dad said, “the Big Guy owed me.”

October 5, 2020

Quite a cast of characters: Another excerpt from "Blue Hill," my latest book, which publishes on Oct. 6

Along with several fictional characters, starting with the narrator, "Blue Hill" features some real-life people -- Jack Nicholson, for example, albeit in fictionalized form. To learn more about the book, which publishes on October 6 - and to preorder in audio, Kindle or paper formats - visit http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

The crowd was hushed. You could see them glancing around, nervously, a case of mass suspicion. I looked at them looking and saw—my number-one fan, the tall skinny kid who’d wanted Ultra Bloodfest.

“It’s him!” he shouted, pointing at me.

“The crazy old guy!” his friend added.

“HE’S THE SOCIETY STALKER!”

The boys looked terrified. They looked like I was about to eat their livers, here in view of two hundred people—and then they ran, screaming as they ripped through the crowd.

In an instant, the place was bedlam. Kids shrieked as mothers tried to get them to safety. Elders fainted. And when I bolted, a blue-uniformed security guard decided it was his moment to become a hero. You know the type—a twenty-something high-school dropout entrusted with a loaded sidearm and carrying a boatload of attitude.

“Stop!” he shouted.

I plowed into the scattering crowd.

“Stop or I shoot!”

That only happens in movies, I thought.

I didn’t stop.

It didn’t happen only in movies: Our intrepid hero fired a warning shot over my head.

And then another, and another, until his magazine was empty.

The bullets must have hit a power line because bulbs blew and the ceiling started smoking and the mall went dark. Alarms were ringing and people were crying and screaming and Christ knows why, but the fire sprinklers were sprinkling—and I kept on going, past stores, down a stopped escalator, outdistancing the guard, across a promenade and into the enclosed walkway that connects Copley Place with the Prudential Center, which is next to the Sheraton, where I was staying.

I was being pursued.

Not by the guard—that slug had fallen by the wayside—but by a young man with a fancy camera. I never did learn if he was an off-duty news photographer, or an intrepid freelancer, or just some feckless passerby. Whoever, he wanted my picture. Wanted dozens of them! A paparazzi, of all things! And an athlete, to boot—a sinewy young man in Nikes who surely ran marathons! He was gaining quickly on me when, as impulsively as I’d done anything in that season of impulse, I stopped and dropped my trousers. Mooned him as he clicked away.

“Is that what you wanted?” I said.

Before he could answer, I snatched the camera from him, opened it and exposed the film. Then I threw his camera onto the floor. It shattered and the flash exploded.

I ran into the Prudential Center and ducked into an elevator.

The doors closed.

I was going down.

“Shit,” I said.

My room was on the twenty-third floor.

The elevator stopped at the parking garage. I was about to hit the button for my floor when I noticed a magnificent black ‘30s roadster. A distinctive-looking man dressed in a white three-piece suit and wearing a tan fedora was behind the wheel, smoking an unfiltered cigarette.

By God, it was Jack Nicholson! Driving the car he drove in Chinatown! He smiled when he saw me. Evidently, he’d been waiting for my arrival.

“Take a load off your feet, kid,” he said, opening the passenger door.

I got in.

“What happened to you?” he said, examining my face. “Don’t tell me the old liver’s giving out.”

The cream had created a tan in streaks, as was evident on inspection. Close on, the overall impression was jaundice.

“It’s a long story,” I said.

“Don’t I know,” Nicholson said. “I’ve been following you on TV.”

“Then you know why I couldn’t make the Knicks.”

“Disappointed as I was, I understood.”

I noticed Nicholson had a flask cradled between his legs.

“Johnnie Walker Red,” he said. “Good for what ails you.”

He offered me the bottle. I took a swig and thanked him.

“Don’t mention it,” he said. “Cigarette?”

He opened a silver case and I took one. He lit it. I hadn’t had a cigarette since Venice Beach.

“I’m lucky I made it out of there alive,” I said, inhaling deeply.

It was a Camel. It tasted wonderful.

“Tough audience,” Nicholson agreed, “but aren’t they all? They love you when you’re up—and when you’re down, you might as well be wind from a duck’s ass.”

It was J.J. Gittes’ best line in Chinatown.

“Look how they crucified Roman Polanski,” Nicholson said.

“Or Randall Patrick McMurphy.”

“Exactly. All I can say, kid, is your story’d make a hell of a movie.”

“I suppose it would,” I said, modestly.

“Call it My Adult Life or Blue Hill or Deep Blue, something darkly ironic like that. Or 1997, if you want to capture the zeitgeist of the era and quite an era it is. You’d have the critics eating out of the palm of your hand.”

I said: “The only issue is: Would it be a comedy or a tragedy?”

“Neither,” Nicholson said. “It would be a farce. What a silly ass you’ve become, if you’ll pardon the pun.”

I was crestfallen.

My face must have given me away, because Nicholson added:

“You haven’t lost your sense of humor, have you, kid? That was a joke! As for tragedy or comedy, it would be both. You’re talking Hollywood. Nuance means nothing out there. Think Oscar. We’d go for the big lights and forget the rest.”

He took a long, loving swallow of Johnnie Walker.

“Only one person,” he said, “would do justice directing: Robert Altman.”

“Not me?”

“You’re too close to it, kid. Not that you don’t have what it takes, ‘cause you do. Your day will come.”

“Thanks.” I smiled.

“Know who’d have to play you?” Nicholson continued.

“Sure I do,” I said. “You.”

“A gentleman you are,” Nicholson said with that shit-eating grin I adored, “a casting agent you are not. I’m a little past that now, kid.”

“No, you’re not. You look the same as you did in Cuckoo’s Nest.”

But he didn’t. Off screen, up close, in the unforgiving fluorescent light of an underground garage, you could see gray roots and what probably were scars from plug transplants. I saw his eyes, the flesh around them especially, and I knew why he always went out in shades. Surgery may have ameliorated all those years in Hollywood, but it couldn’t erase them.

And if I’d had a time-travel machine, I would have seen the sad last chapter of his life, when he suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, his memories and long career achievements scrubbed from his mind, as if they had never happened.

“God bless you,” Nicholson said. “I was thinking more along the lines of Tom Hanks.”

“I’m flattered.”

“The big question is who’d do justice to Allison. I kind of have Julianne Moore in mind.”

“She’d be perfect,” I said. “Perfect! They even look alike.”

“Don’t think I haven’t noticed. You saw Lost World, I’m sure.”

“Three times.”

“Only thing wrong with that picture was Moore kept her clothes on. I ask you: What the hell would have been wrong with a little skin—say, one of those velociraptors ripping off her shirt just before she escapes into that building?”

“Nothing at all!” I said.

“I’m not talking sex—just give me a second or two of tit!” Nicholson said. “Use a body double if Moore’s not the type—but give me somethingto hang a fantasy on, for Chrissakes! Well, that’s Spielberg for you. Damn prude. Only skin he’s ever given us was in Schindler’s List, of all fucking flicks! What are your thoughts on who’d play Ruth?”

“Faye Dunaway?”

Nicholson looked over his sunglasses at me.

“Have you seen ole Faye lately?” he said. “I think Glenn Close is more what I have in mind.”

“Or Rene Russo."

“Better yet. Good middle-aged women are so hard to find.”

We were relating now. I could feel it. Destined for each other over the miles and the years, our souls had finally, irreversibly connected.

Nicholson took another hit of whiskey and checked his watch.

“Sorry to cut out on you,” he said, “but I’ve got a Celtics-Lakers game to catch. It’s not the same without Magic and Larry, but that’s life in the big city. Things change.”

“Not you, Jack.”

“Even me, Mark.”

He started the car.

“Take me with you?” I asked.

Nicholson was puzzled.

“To Boston Garden?”

“To anywhere.”

“I’m afraid you’re on your own now, my man. Just watch out for that Malloy: There’s something not quite right about him.”

“Everything’s so fucked-up,” I said. “I need help.”

“What you need,” Nicholson said, “is a golf club!”

He grinned, and then he was cackling, and before long he was wheezing, he was so amused with himself. Apparently, he still wasn’t over his freeway encounter.

“That’s not funny,” I said.

“Not funny? You really have lost your sense of humor. The shit you’re in, my friend, you need one. I wasn’t kidding about the golf club. They’re all bastards. Have a little fun at their expense. You’re good at that kind of stuff. I laughed myself silly at the Sermon put-on at the convention.”

I was stunned.

“You were there?” I said.

“Hell, yes,” Nicholson said. “Snuck in at the last minute and had to run out before you got your Wilbur—congratulations on that, by the way. I figured I’d see you at the Knicks. Now if you don’t mind, I’ve got to go.”

“Please don’t,” I begged.

“Don’t make me do something I’ll regret,” Nicholson said. “We’ve been friends too long.”

“We could go to the movies,” I said. “I’ll pay.”

Nicholson took off his sunglasses and our eyes met.

“You just don’t get it, do you, kid?” he said.

He was not a man to mess with now. I stepped out of his car and slowly closed the door. He put the transmission in gear and roared off.

Nicholson photo courtesy Kingkongphoto, www.celebrity-photos.com via wikipedia commons.

October 1, 2020

Blue Hill: An excerpt from Chapter Four

Baseball is a central theme of my new novel, "Blue Hill," a departure from my other fiction, which has been solidly in the mystery, horror and sci-fi genres. To learn more about the book, which publishes on October 6 - and to preorder in audio, Kindle or paper formats - visit http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

I never could visit Fenway without thinking of my father.

I would never have admitted it to him, of course, because it would have plunged us into issues I never intended to revisit, but it was true. Just seeing the Citgo sign in Kenmore Square set me off.

Dad was an Episcopal priest until his retirement a few years back, and my guess is when he gets to the pearly gates, Saint Peter will wave him straight through.

And not only for the collar he’d worn.

Dad believed in social justice, believed that principle mattered more than ascending the Episcopal hierarchy, even though principle had cost him a bishopric. He believed life was about more than desiring things, and my mother, who’d been raised in a house without plumbing, agreed. Dad went stratospheric over war. He’d been a conscientious objector during the Second World War, not exactly the launchpad for a Great American Hero, and his sermons on Veterans Day and Memorial Day were thundering tirades against the military-industrial complex. It was scary, watching the guy who read me Thornton Burgess starting before I could walk transformed into Cotton Mather of the nuclear age. And when I was too old to be scared, I was pissed.

Lest you imagine him as all fire and ice, it must be noted that Dad had two—exactly two—earthly indulgences.

One was Sunday dinner, which he always cooked to give Mom a day off.

The other was the Boston Red Sox.

Dad had played ball as a kid, well enough to be invited to tryouts the year he graduated from high school. He idolized Foxx and Williams, and he was at Fenway with my grandfather the day in 1946 that the Sox clinched their first pennant in three decades. Once a year, in August, we drove down to Dorchester, where my mother’s brother lived in a triple-decker. It was our vacation, all we ever took—me and Dad at Fenway while Mom bought school clothes at Filene’s Basement, where goods after three weeks were automatically marked down 75 percent.

If I had one certainty in my young life, it was that I was going to play for the Sox when I grew up. I was going to have my face on Wheaties boxes and drive a red Corvette with a 427 V-8 and when I pulled into Fenway, I was going to be mobbed by fans seeking autographs. In other words, I was going to be just like Tony Conigliaro, youngest player in history to hit 100 home runs.

I still had my Little League scrapbook and sometimes, for no reason at all, I flipped through it. “Gray Hits Third Grand Slam of Season,” is one of the headlines from the Bangor Daily News. “Gray Leads Blue Hill to Maine Title,” is another, from the June 21, 1967, edition. I was ten that year. Ten! No other starter was so young. We went to Hartford for the regionals, and it was there that I faced the best fastball pitcher in all of New England.

I remember watching him warming up and thinking with a fear worse than going to the dentist: The ball’s a blur! I’ll never be able to hit it!

His first pitch to me was a ball, his second a strike. I didn’t see his third until it was too late to duck: It hit me in the left temple and I fell, unconscious.

When I came to, I was in an emergency room, an ice pack on my head.

“You were very lucky, son,” the doctor said. “I’ve seen kids in comas from less.”

And I can still see it—the knowing nod he and my father exchanged.

Mom got sick right after that.

“I don’t feel myself, is all,” she started to say, and pretty soon, she was spending most of every day on the couch.

That part of that summer is a blur—no matter how I’ve tried to bring it into focus, all I come up with is Mom under an Afghan and the TV on without the sound. She didn’t make the trip with us to Boston that summer, but she insisted Dad and I did. We stayed with Uncle Bob, and on August 18, the day everything changed, we were at Fenway Park.

September 10, 2020

Listen to the books!

Less than a month remains until the October 6 release of my next book, "Blue Hill," a novel, in paperback, Kindle and audio formats. You can preorder any (or all!) of the editions now on Amazon: https://amzn.to/3565Ysb

Want a sample of the audio by great narrator Justin Kawamoto? CLICK HERE

And if listening to books is your thing, you may appreciate audio editions of some of my other titles.

*****

With Halloween on the horizon, check out the audio version of my debut horror novel, "Thunder Rise," first volume in the Thunder Rise trilogy, which remains in print decades after publication. There has been a lot of interest in the audio version lately, the data shows. So why not?! CLICK HERE (sample available)

*****

A medical tale unlike any other, "King of Hearts" also remains in print in many editions two decades after publication. For the audio version, CLICK HERE (sample available).

*****

And in that same genre, consider "The Work of Human Hands," my first non-fiction book, about the legendary Dr. Hardy Hendren, former chief of surgery at Boston Children's Hospital and one of his most difficult cases. CLICK HERE (and, yes, sample available!).

July 22, 2020

This Time, I Walk

A lucky consequence of the pandemic is that, staying mostly home now, I have more time for my fiction writing. As The Providence Journal’s health reporter, I remain on the coronavirus strike team -- but after (and before) those long days, and on days off, I am indulging anew a passion with roots in elementary school, when I began scribbling tales of fantasy, perhaps as a way of momentarily escaping a rigid Irish-Catholic childhood.

I recently completed “Blue Hill,” a novel that will be published on October 6, and I am deep into writing another, due in 2021.

I also have had opportunity to open the proverbial writer’s trunk, where dozens of short stories and books, in varying degrees of completion, some promising, others worthy of immediate burial, have languished – some for decades. (Fellow writers, you know whereof I speak!)

One such piece is “This Time, I Walk,” a horror short I began in 1986 about a virus that was soon to cause a pandemic. If you haven’t guessed, it was inspired by reading my favorite author Stephen King’s “The Stand” – and by the many headlines about HIV/AIDS, which had reached wide public consciousness in 1985, when Rock Hudson announced he was infected. I interviewed King in 1986, in a session that remains one of my favorite encounters with creative giants. And I was writing “Thunder Rise,” my first published book.

In light of today, "This Time, I Walk" was prescient.

The idea came to me walking the streets of Manhattan back then, perhaps even that day I interviewed King, though my memory is not so precise. The mid- to-late 1980s was a heady period in horror writing, with King, Peter Straub, Dean Koontz, Clive Barker and others breaking into the mainstream with best-sellers that captivated mainstream audiences. I was on board, furiously penning horror (and sci-fi, mystery and thriller) stories and the novel “Thunder Rise,” published in 1989 by William Morrow and edited by the late Alan Williams, who was also editing King at the time. My agent then and for many years was Kay McCauley, who with her brother, the late Kirby McCauley, represented the man from Maine.

As I walked teeming Manhattan on that day, the idea for “This Time I Walk” materialized – I can think of no other way to phrase it, for the genesis of ideas remains a mystery still, although King’s answer one time to the question “Where do you get your ideas?” was “Utica,” as in the New York city, seems as good as any.

OK. Reading “This Time I Walk” for the first time in many years, I discovered that I had not written the ending. Not even any notes.

So I had to write that ending, and I did.

For now, Parts One and Two of five parts.

This Time, I Walk

by G. Wayne Miller

Copyright 2020 gwaynemiller.com

This time, I walk.

I start early, in order to catch the commuters. So many busy people in the big city. So many pretty secretaries. So many hard-working mothers and fathers. So many big shots, major domos, people of substance and weight, the movers and shakers of society here in and around Boston, Massachusetts.

You see, I walk.

I begin where I sleep, the Park Street subway stop, and I walk down Tremont to Chinatown. Up Washington, past the hookers, the porn palaces, the stores where the magazines are wrapped in cellophane. Past City Hall, through Quincy Marketplace to the over-priced waterfront, back through the banking district, over to the mall in time for the midday shoppers.

All day and into the summer night, I walk.

I walk and I breath -- always breathing, deeply satisfying breaths, in-out, in-out, in-out, a healthy vigorous breathing even though I allow myself a smoke every now and then. When I breath, I can feel that familiar strange tickle in my lungs, and I smile. I know it can't hurt me, what's been waiting patiently inside there all these years.

So many thousands go by, an endless river, and I walk.

Scum, they say, those that speak.

Swine.

Bum.

You need a shave, bud. Whatcha got in the bag, arse-hole. Smoke? Stick it up your butt, dogbreath. Get lost. Get a job. Get outta my way. Get bent. Get stoked, stiff.

Lots of gets, courtesy the fine people of Boston.

I do not answer. I do not speak at all.

But it makes me grin, knowing what I know. Yes, I am a forbearing man.

It is good to be alive. In my own way, I am having a ball. You may find that difficult to believe, looking at my clothing, my beard, the shoes, the bundle I carry, but it is true. It is good to walk, to have that occasional cigarette, to drink heartily from that bottle and enjoy. It is good to be free, to have my health, such as it is, to be able to breathe.

It is good to be alone.

It is good to be in the city, surrounded by so many.

I consider all of you to be my friends. I hate you with a passion that does not abate, yet you are my friends. A paradox, you say? The world is full of them. The sun that rises in the morning must sink in the evening. From the dead earth of winter blossom the living flowers of springtime. In the eye of a storm, the calm. Paradox, my friends, the natural order of things. Or are you so blind that you cannot see?

The young ones, most frequently, spit.

I have been robbed, beaten, rolled, mugged, preyed upon, chased, cornered, locked up, sent away. I have been kicked, pounded, pummeled, struck across the back of the head, and once, while I slumbered, urinated on. I have fought back, but in my own way and on my own terms.

Ah, humanity.

I admit I am not a pretty sight. I have plans to clean things up.

Still, I know what I am, the nasty side of mankind still living in caves. I myself lived cave-like once, in the not-too-distant past.

And yet, that is not the half of it.

Has it always been this way, you silently ask yourselves as you pass me by, the signature of disdain and disgust written unmistakably on your faces, in the way you will cross streets or step off the curb to avoid me. You should know better than that. You with the stylish clothes, the kids and Volvo station wagons at home, the golf courses and Cape Cod weekends, the neat ordered lives that are about to be ripped asunder and destroyed -- you, my friends, should know better than that.

No one is always this way, or any way. Motion is inevitable. Change is eternal. Didn't Hegel teach us that? Marx? And Darwin? Everyone is born. Everyone is a baby once. Everyone crawls before walking, burbles before speaking, scribbles before writing. Everyone loves, and in turn feels love, somewhere, no matter how faint or how brief. Everyone has a past, and there is good in that past, and there is bad, too, not always in equal proportions. No matter how many storms have ravaged.

I walk.

I walk because I want to be with you, because I have something for you. I walk because of what you, this species called homo sapiens, have done for me. I want to pay you back.

Not necessary, you protest? What was due has been paid?

Oh, but I insist.

So I walk, always on the move. I especially like to walk past the tourist hotels and the convention centers, of which there are a growing number in Boston. I especially like to mingle with the out-of-towners, the Midwest teachers on vacation, the busloads of schoolkids from New Hampshire and Maine, the businessmen hoping to strike it lucky in the hotel bars, the company outings here for an afternoon at Fenway Park. They will go home, all of these out-of-towners. They will not know it, not today or tomorrow or the next day even, but with them they will carry the lasting memory of me.

Let me tell you a little story.

It is my story, all I have. I think there are things you should know, the next time you push on past me, through the heavy stench of my breath.

The story begins, as many do, in the long-ago and far-away. I was a much younger man then, a far more respected man, if I may be immodest. I was, in fact, a scientist, and I was called a doctor for the PhD I carried after my name. Specifically, I was a climatologist, a well-published and scientifically daring one, and my specialty was the conditions of weather and astronomy that produce glaciers. My theories of orbital inclination (that is, the changing angles with which the earth over the millennia have faced the sun) had revolutionized our basic understanding of the Ice Ages and I had recently co-authored what was then the definitive text on the subject.

Therefore I was honored, but not surprised, when I was invited to join Polar '62.

Chances are you have never heard of the Polar '62 expedition. There is no good reason that you should have. Kennedy was in Berlin when the undertaking was announced, the news was all bluster and the fate of mankind, and we rated only a small mention as a wire story on an inside page of the New York Times. This bothered none of the 17 scientists who formed our party, and I sincerely doubt it made any difference to the 26 seamen and officers who manned our ship, the RV Arctic Maiden, either. Almost without exception, the most significant work in science is conducted in a methodical and decidedly non-romantic fashion, hardly the stuff of front-page headlines, unless it happens to be polio or cancer or something or someone shot into outer space.

Whatever the scientific fascination, ice and snow, I need not remind you, fit none of these categories.

Do not imagine, however, that this was your run-of-the-mill scientific junket. This was a million-dollar effort, years in the planning, supported by private funds and a congressional grant, and it would be many more years before our best universities and scholarly institutions would sift and sort their way through the incredible wealth of data with which we expected to return. Never had there been such an assault planned on the Arctic. Byrd and Peary could only have dreamed of what we were determined to do. The spectrum of interests was, perhaps, for a single mission, unique. There were scientists with expertise in glaciation, zoology, ultraviolet radiation, meteorology, geology, microbiology, internal medicine, immunology -- yes, the explorers themselves were to be subjects of unprecedented research. The eventual result, we were confident, would be not only a deeper understanding of that God-forsaken region, the Arctic, but also of the globe and mankind itself.

On an unusually hot, steamy day in late June, we left Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod. We departed with considerable fanfare including attention from the local press and the tears of wives and children, of which I, a 32-year-old with dreams of a Nobel Prize, had neither.

The irony the weather presented did not, of course, escape us. In another week we were to be plunged into one of the harshest environments on earth, the northern extremes of Greenland, that most misnamed of lands. True, it would be summer there when we arrived, with daylight around the clock, and afternoon temperatures rising well into the balmy 50s -- but Arctic summers are notoriously short, as fleeting and ultimately disappointing as a mistress's midnight kiss, if I may be so poetic. Within two months of our arrival, along toward the end of August, the mercury would begin to plummet, the snow would begin its relentless siege, and we would be locked into the Siberian vice-grip of an Arctic winter. We planned to stay almost a year, returning in May, when the ice had released what would then have become our captive ship.

From Woods Hole, we put in at St. John's, then continued on to Godthaab, Greenland, where we took on board a handful of bearded and bespectacled Danish scientists who were to make the journey with us. From Godthaab, we steamed north, along the shore of Baffin Island, where we observed the icebergs to be multiplying in both number and size. We put in a day and a night in Thule, a truly tiny and dreary outpost of mankind, then proceeded north again, until our captain found suitable moorage in a magnificent fjord extending like a skeletal finger off Kane Basin. The ice had grown even thicker, and the fog was nearly impenetrable at times. We would safely go not further, our captain informed us, and there was universal assent that Kane Basin suited our various needs to a T.

It took the better part of two days to unload our supplies and equipment and establish our base camp on a solid sheet of rock overlooking the sea end of a tired and dirty glacier. Ours was not so much a travel expedition -- the vastness of Greenland by then, of course, had long since been charted and mapped -- but an exercise in information-gathering and experimentation that could, for the most part, be conducted from a single camp. Naturally, there would be out camps and selected journeys inland, of two or three week's duration. For these, we had along two dozen Huskies and traditional Eskimo sleds -- this at the insistence of our Danish hosts who, for reasons we did not attempt to fathom, were soured on mechanized means of over-snow locomotion that were then becoming popular.

The first weeks were a period of industry and good cheer amongst our party, which had taken residence in a series of tents erected behind the comparative shelter of a series of house-size boulders. There is a certain savage beauty to the Arctic summer, and that beauty, combined with the endless day, was like a tonic for all of us. For it is summer when the wildflowers bloom, the lemmings and ermine and arctic hare are on the prowl, when whatever other limited flora and fauna there is in this unforgiving territory explodes in one fleeting celebration of life and reproduction. Then, too, there was the almost daily display of aurora borealis, or northern lights, which paints its ghostly rainbow across the sky like the backdrop to some wildly haunted dream.

As for me, I was intent on rainfall collection, pollen analysis, color spectrometry, ice coring -- especially the latter. An entire history of weather is captured in the layers of ice that comprise a glacier, and a simple hand-auger-driven core, although time-consuming and sweat-inducing and muscle-tiring, is worth its proverbial weight in gold. My colleagues were plunged into their various and sundry labors, and there was the unspoken but certain feeling that what we had successfully embarked upon was an expedition bound for inclusion in the ranks of all-time great Arctic ventures, if such is the way to describe a hardy legacy that predates Eric the Red.

Winter's arrival did nothing to disturb the enviable camaraderie that had developed amongst us. If anything, it only served to strengthen the bonds that had grown and which now joined us together like the close-knit family we had in fact become. The snow was virtually without stop, as those of us who were newcomers to this land had been told to anticipate. The wind was a harsh master and the temperatures were soon similarly uncooperative, and by the beginning of October, it was rare indeed the day when the mercury could be coaxed above zero degrees Centigrade.

But it was not weather, or the onset of the Arctic night (which, as you may know, lasts 24 hours a day) that began to change the temperament of our party toward the beginning of January.

No, it was not that. Christmas had come, and we had joyously celebrated it with an evening of old-fashioned caroling and a rare dinner of reindeer steak with gravy, a Danish custom on this largest of Denmark's islands. Those of us who so desired had chatted fleetingly with our families by short-wave radio, and that personal contact with loved ones and kin would be enough to sustain us for many weeks to come.

No, it was the discovery at Outcamp 3 that would eventually bring ugly turmoil to Polar '62.

Outcamp 3 had been set up some four kilometers inland by the microbiology folks, who were in pursuit of various strains of bacteria known only to this region and its equally inhospitable twin, Antarctica. It was little more than a single tent, this particular Outcamp, and it was not manned on a continual basis, but only as the dictates of microbiology demanded. Dave Heddon was the head of the microbiology contingent, which numbered exactly three, including Dave. He was a subdued man, introspective yet not glum, a powerful, broad-shouldered father of two young boys who looked for all the world like a starting defensive lineman for a professional football team. Had he been less clumsy, or more aggressive, I think that sport indeed would have suited him.

But he was a scientist -- tops in his field, or so was the glow of his reputation -- and he possessed that deliberate and calm way of speaking, so wonderfully rare, that is immediately soothing and almost therapeutic to those who hear it.

And that's how I knew something was up the evening of January 24, when he returned from three days at Outcamp 3.

I was alone in the chow tent, finishing off a cup of freeze-dried coffee, when Dave walked in, his beard twinkling with frost and his boots glazed with ice. In place of that calm voice was an imposter, a voice that fairly crackled with excitement. Remember, Dave Heddon was a man of unusual emotional maturity and control. I had learned that listening to him describe how much he missed his two young boys, but how sacrifices must sometimes be made in the name of science -- and now, now he was a man speaking with the control of a teenaged girl.

``Out there,'' he began, sipping on the steaming coffee I had brought him, ``I think we have discovered extraterrestrial life.''

``What?'' I asked.

``What we found by 3,'' he said. ``Frozen. And perfectly preserved, or so it would appear.''

``What?'' I repeated, persisting in my ignorance. ``What have you found?''

``Alien life. Twelve beings. From where, is anybody's guess. But definitely not of this world. You'll know that as soon as you see their... their heads.''

And then, his voice still tinged with an unusual excitement, he went on to relate the events of the last two days at Outcamp 3. How he and one of his party, Joanne White, one of the few women in our group, had set off the first day to gather samples on the agar plates they carried in special aluminum boxes. How they had wandered perhaps 200 meters north of the camp through an unusually strong, snowless wind when they happened upon... shall I call them beings, as Dave did?... and the wreckage of a vehicle they initially believed to be constructed of steel.

We had reached the peak of a slight rise and were descending the opposite side when our lights picked up what we first assumed was another rise, albeit one irregularly contoured. Thinking little of it, we moved closer, our lights stabbing the pitch. As we approached, the rise took on a distinctly different shape. Or shapes, I should say, for there were several.

The most prominent was a rockpile, roughly the size of a large automobile. It looked as if it may have been erected, however crudely, for purposes of shelter. Off to one side was a circle of blackened stones that appeared to have once enclosed a fire. Moving closer still, we got our first indistinct look at the... beings, four of them, sprawled in various contorted postures around the stones.

Of course, the term `beings' had not occurred to us then. Standing from the distance we were, and under such unsatisfactory light conditions, we assumed we had found the remains of earlier human explorers -- the frozen cadavers of the unfortunate members of whatever ill-fated party it had been. Many of the early European and American pioneers of this region, as you know, never came home and were never found. As recently as 1956, not 10 years ago, the Finnish expedition was last, as also you may recall.

And who would have thought otherwise? The forms we were surveying were of human size and appeared to have the human compliment of limbs -- two arms, two legs -- and they were clothed in mammalian fur not the least bit incongruous for this cruel environment. Arctic hare was my guess. Of the four forms, no faces were visible. Not then. It seemed that their heads were unusually large, but that was difficult to ascertain. They had died in the same position, on their stomachs, faces into the snow.

TO BE CONTINUED...

July 7, 2020

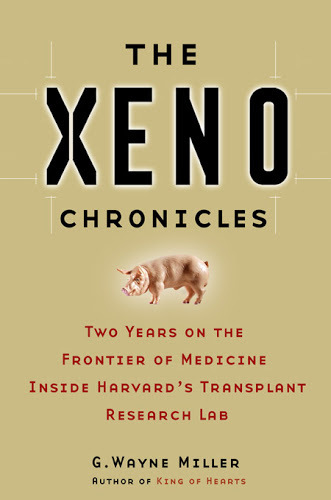

The Xeno Chronicles

Chapter 1: Double Knockout

I. 'Goldie is here'

A cold day was dawning when Dr. David H. Sachs left his home and headed to his Boston laboratory, a few miles distant. He was praying that experimental animal no. 15502 -- a cloned, genetically engineered pig -- had arrived safely overnight from its birthplace in Missouri.

It was Friday, February 7, 2003.

Ordinarily a calm and measured man, Sachs had fretted for weeks over this young animal, whose unusual DNA might help save untold thousands of human lives. He worried about the weather, so frigid that Boston Harbor had iced over and pipes in the animal facility had frozen, fortunately without harm to the stock. He worried that the pig would become sick before getting to Boston. He had decided against transporting it by truck, for a winter storm could prove disastrous -- so then he worried about flying it up. What type of aircraft should they use? Commercial? Charter? Which airport in the congested metropolitan area would be safest?

"Use your best judgment," Sachs had told the staff veterinarian he assigned to bring the pig north. "Just don't lose this pig!"

A surgeon and immunologist, Sachs had distinguished himself in the field of conventional transplantation, in which human organs are used. His lab, the Transplantation Biology Research Center, was a part of Massachusetts General Hospital, where he was on staff. He was a professor at the Harvard Medical School. He belonged to the National Academy of Sciences's Institute of Medicine. He was fluent in four languages. He had written or co-written more than 700 professional papers. Science came as naturally to Sachs as breathing.

One achievement, however, still eluded him.

For more than three decades, Sachs had tried to find a way to get the diseased human body to accept parts from healthy animals.

Many scientists over many years had tried to achieve what Sachs sought. So far, the idea remained a dream.

Xenotransplantation had the potential to save thousands of people who die every year because of a chronic shortage of human organs. Sachs envisioned a time when patients needing a new heart, liver or kidney would simply have their doctor order one up from the biomedical farm. Children born with defects and older people with all manner of ailment would benefit. And while riches didn't compel Sachs, xeno, as insiders often called their field, could become a multi-billion-dollar business. You couldn't buy or sell a human organ, at least not in America and most countries of the world. But there were no laws against commerce in animal parts.

Many scientists over many years had tried to achieve what Sachs sought.

So far, the idea remained a dream.

A man of average height, Sachs was on a diet but still carried a few too many pounds, a fact he jokingly acknowledged when describing himself as "chubby." With his full head of graying hair and his jolly face, the image of a Teddy bear came to mind -- an image that was reinforced when he laughed, which was often. Sachs favored button-down shirt, tie, khaki slacks, a rumpled suit jacket, and wingtip shoes. Unless you looked closely, you would not notice that his right foot was larger than his left, a remnant of his childhood when, at the age of 4 1/2, he contracted polio, the childhood scourge of the 1940s. Sachs spent weeks at Manhattan's Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, an institution on 42nd Street and Lexington whose very name evoked suffering. His polio affected only his lower body, so Sachs did not require an iron lung, a more terrifying symbol still.

Sachs eventually went home -- with the doctors' prognosis that he might never walk again. But he did walk again, perfectly normally.

"It just never seemed possible to me that I wouldn't," Sachs said. "It just seemed to me that I had to get over this problem. I've never had a defeatist attitude toward anything. I always feel that it's just a matter of being able to figure it out, make it work. That's my attitude toward everything."

But Sachs could not stop the clock. He was past 60 now and increasingly aware of his mortality. He occasionally joked about wanting to be frozen, like Ted Williams, so that if they ever solved the thawing end of cryonics he might return to experience the marvels of a distant age -- an age, he believed, when disease would have left the earth.

"Only recently I have started to realize how finite my lifespan is," he said. "Of course I've known that since I could think, but as you get older you realize that nobody lives past 100 and I'll be lucky if I get over 80 and I'm already 61. So I don't have a hell of a lot of time left."

In his darker moments, Sachs wondered if he would ever achieve his grand ambition. Experimental animal no. 15502 -- a creature small enough to fit into a baby stroller -- might well be the beginning of his last chance.

Sachs parked his Saturn, then cleared the guards with their walkie-talkies and closed-circuit TVs in the lobby. He needed a card key to operate the elevator and to open the outer door to his lab on a floor upstairs. Another lock secured the administrative suite, with yet one more protecting his inner office.

Once inside, the atmosphere was delightful: this was a bright, open, corner space with a commanding view of Boston Harbor, and Sachs had decorated it with photographs of colleagues, mentors, and friends, and his wife, Kristina, and their four children. The scientist felt blessed with having so many good people in his life, and he still marveled at having three daughters and a son after Kristina's first three pregnancies had ended in miscarriage and her obstetrician had predicted she would never give birth. Except for the books and professional journals, one of the only clues into the nature of Sachs's work was a pink stuffed pig.

It was nearing eight o'clock.

Sachs checked his e-mail -- those messages that had come in since he'd last checked, at home over breakfast. He put on a lab coat, left his office, and passed through the main conference room, which featured a photograph of a Little League team that he had sponsored and a large bulletin board for laboratory business.

Alongside the ordinary notices and schedules was a clip of one of the few stories about Sachs that had appeared in the mainstream press. It was a piece from the August 11, 2001, San Francisco Chronicle, and it concerned a precursor animal to no. 15502. "This little piggy may be what the doctor ordered," the headline read.

The clip included a photo of Sachs, posed behind a beaker. The writer listed some of the reasons the miniature breed of pigs that Sachs used were the current focus of xeno research: their organs are similar in size and function to a human's, and nearly 100 million pigs of all sizes already are slaughtered for food every year in the U.S. alone with little protest from anyone. And unlike chimpanzees, who were immunologically closer to people -- and who looked more like people than any other animal -- pigs were pigs.

The Chronicle story was straightforward and informative, but a printout of an Internet page that someone had posted suggested that the pursuit of xeno could prompt a quirky humor.

"The U.S. is critically low on organ donations. What is the nation's medical community doing to address the shortage?" the page read. One answer offered was: "Removing David Crosby's new liver and giving it to a more deserving person." Another was: "Allowing recipient's body to reject maximum of two hearts; after that, no more favors for Mr. Picky." A third was: "Experiment with tofu-based organ substitutes." Xeno humor wasn't confined to this bulletin board. An unsigned editorial comment in a recent issue of Xenotransplantation -- which Sachs founded and which a senior member of his staff now edited -- noted that some surgeons are considering face transplants. "This is unlikely to be an area in which the xenotransplanters can become involved," the editorialist wrote.

Sachs left the conference room and went to a separate facility, which was secured by yet another electrically-locked door. He opened it with his cardkey and stepped into a windowless domain constructed of cinderblocks painted a glossy institutional beige and lit with fluorescent bulbs. This was the animal area, where experiments were conducted and where he gathered his scientists every Friday at eight for large-animal rounds.

At any given time, Sachs's staff included nearly 90 scientists, technicians, assistants, administrative aides and secretaries. Many were research fellows: young men and women who stayed a year or two before moving on in their careers. Although Sachs was no household name, his reputation inside medical science was large, and competition for his fellowships was intense. Over the years, he had attracted scientists from all over the world.

Some two dozen men and women, most wearing white coats, awaited Sachs on that February 7. They lined a wall of the animal area's central corridor, which separated the baboon room and the pig rooms from the operating suites. A strict, if unwritten, hierarchy was observed: non-scientists stood at the ends of the line, with the middle held by two of Sachs's senior staff researchers. One was Dr. David K.C. Cooper, 62, a tall, refined British surgeon (the K.C. stood for Kempton Cartwright) who had transplanted hundreds of human hearts and had worked in South Africa with Dr. Christiaan N. Barnard, who transplanted the first heart, in 1967. The other was Dr. Kazuhiko Yamada, 43, a Japanese surgeon who so impressed Sachs with his surgical prowess and innovative ideas during his 1990s fellowship that Sachs brought him on staff. Both doctors conducted research on allotransplantion -- same-species transplants -- but, like their boss, they held special passion for xeno.

Sachs took his place in the precise center of the line, bid everyone good morning, and large-animal rounds were underway.

One by one, scientists stepped to a chalkboard that held dozens of paper cutouts in the shape of a pig. Each cutout had a number that corresponded to an animal. The scientists described the status of each of his or her experiments and Sachs, who had no notes but held the most minute details in his head, asked questions and made suggestions. Although he no longer personally conducted experiments, Sachs supervised all those that took place in his lab. He was not overbearing or arrogant, just frightfully smart. Only when one of his people was clearly headed in the wrong direction, which was infrequent, would he overrule.

Most experiments involved transplanting organs from one pig to another, a model that mimicked conventional human transplantation. In their efforts to make transplants simpler and safer, the Sachs researchers experimented with drugs, radiation, bone marrow, and the thymus, a small gland that plays a large role in the immune system. The Holy Grail was tolerance: eliminating the need for the immunosuppressive drugs that a recipient must take for life to prevent rejection. Such drugs can cause cancer and many other side effects, some potentially deadly and some cosmetically unappealing, and they leave a recipient at increased risk of infection. "A cold that you or I would get over in a day or two can be life-threatening," Sachs said. Weight gain and hair growth didn't kill, but for women especially, they could be depressing.

Here, Sachs had enjoyed success: working with colleagues at Mass. General, and building on a long body of research by other doctors, he had devised a way to manipulate the immune system so that a recipient would accept a transplanted organ without having to remain on drugs. The method involved bone-marrow transplantation, and was one of many ways that had been attempted to achieve tolerance. After years of research with pigs, Sachs had helped move it from the lab to the clinic -- where a few people had already benefited, including a woman who was still alive and well and immunosuppressive-free three years after a kidney transplant.

The woman, Janet McCourt, a Massachusetts resident, was the first patient to try the tolerance protocol devised by Sachs and his colleagues.

She had been on dialysis and hated its constraints -- being married to a machine was not her idea of living -- and she was willing to try anything to get off, including a treatment that had only been tried in laboratory animals. "They told me the odds were unknown, because this had never been tried in a human," the middle-age McCourt told a Mass. General publication. "But when we found that my sister was an excellent match and that she was willing to be the donor, I decided to go ahead and risk it. If I couldn't have the kind of active life I wanted, if I couldn't play with my grandchildren, I simply didn't want to live."

More work remained to be done so that more people could benefit, but the success of McCourt and a handful of others who followed was a breakthrough for Sachs and his colleagues. It was big news, not only in the scientific literature but in the mainstream press. It was the sort of work a Nobel committee might pay attention to.

But the excitement at this morning's large animal rounds was not for bone marrow-induced tolerance. It was for the overnight arrival of a 21-pound pig.

"Goldie is here," veterinarian Mike Duggan announced.

Sachs, of course, was aware of xeno's colorful past: of quacks who had implanted goat testicles into impotent men in the 1920s, of legitimate scientists in the 1960s and 1970s who had transplanted monkey, baboon and chimpanzee organs into people. He knew about Baby Fae, the most famous xeno patient ever. He knew of the renewed enthusiasm for xenotransplantation in the 1990s, when scientists had made several major advances and large corporations had invested heavily in the field, only to be disappointed when xeno failed to reach the clinic -- and return anything on their investments.

Sachs knew, too, of other emerging technologies in what was called regenerative medicine: stem-cell science, tissue engineering, and artificial organs. He knew all this and still believed that if xeno could be perfected, it would play a major role in health care.

"I see xeno as a possible answer to the organ shortage in the short-term," he said. "Adult stem cells and tissue engineering have great appeal because they can potentially provide organs that are composed of `self' tissues, thus avoiding the immune response. Fetal or embryonic stem cells are creating a lot of hype, but the tissues and organs derived from these sources would be just as foreign as allogeneic transplants.

"For simple tissues -- like islets or skin -- stem cells and tissue engineering may provide solutions in the near future. However, for organs I think we are many, many years away from a solution. There is too much we don't know about the intra- and inter-cellular signaling required to make a complex organ to expect rapid development of the technology. Artificial organs have the problem of a power supply, and until we can harness nuclear energy in a practical form, organs like the heart will require too large a battery pack to be practical. Also, people do not want to be dependent on an external source of energy that could be interrupted -- e.g., blackouts. The xenograft uses nature's own way of deriving energy."

II. Dolly

Starting in 1973, when he was at the National Institutes of Health, Sachs had bred a line of miniature swine for use in his many transplant experiments. By now, he had bred more than 10,000 of the pigs, and his current colony numbered about 450, but he had never named one. It served no good purpose, he reasoned, for anyone to become emotionally attached to a creature unlikely to see ripe old age.

But no. 15502 was unlike any of Sach's other pigs.

After years of trying, scientists at Immerge BioTherapeutics, a Massachusetts biotechnology firm with which Sachs collaborated, had succeeded in removing -- knocking out, the geneticists called it -- both copies of the gene that produces a sugar molecule found on the surface of ordinary pig cells. These sugar molecules are harmless to the pig -- but when a pig organ was transplanted into a baboon (or a person), the recipient's immune system recognized them as the calling cards of an invader. Within minutes, white blood cells attacked and destroyed the organ, leaving it a dark, useless mess. Hyperacute rejection was the scientific term for this vengeance, which evolution created as a life-saver: the same sugar found on pig cells is also found on the surface of certain parasites, viruses, and bacteria, some of which are fatal to the human. Evolution had not anticipated transplantation.

Sachs hoped that the pig's organs might provide protection against more delayed varieties of rejection, which can set in weeks or months after a transplant. He hoped, too, that fewer drugs would be needed with this pig's organs. That would be a step toward tolerance, the Holy Grail.

Sachs and Immerge also collaborated with the National Swine Research and Resource Center at the University of Missouri's College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources -- and it was scientists there who had cloned animal no. 15502 from a cell lacking both copies of the sugar gene that Immerge BioTherapeutics had supplied. The Missouri scientists wanted to name the pig, born a week before Thanksgiving -- and the name they chose for the so-called double-knockout pig was Goldie. Goldie had a fairy tale-like feel. Goldie captured the medical promise of the piglet and its commercial prospects as well. Immerge BioTherapeutics aimed to get a decent share of that business.

Duggan recounted his journey to fetch Goldie, and it was good that Sachs was learning the details after the fact.

The flight down, in a chartered twin-engine plane that had left Worcester airport the morning before, Duggan said, had been uneventful -- at first. But just after refueling, in Ohio, the airplane's heater blew and the temperature in the cabin dropped below zero. "At that point I was more concerned about my well-being than any pig!" Duggan said. Three hours later the plane touched down safely in Missouri, where mechanics fixed the heater and a veterinarian drove up with Goldie.

Hand-fed since birth, and pampered perhaps more than any experimental pig ever, Goldie had never left her home in Missouri.

Now she was inside a dog crate, flipping out.

"She had always been in a single room by herself with a lot of human contact," Duggan said, "and now she was taken from that environment, put into a crate, put into the back of a truck, driven to an airport. Then she was being taken out of that environment into the strange environment of a plane -- loud engines, the whole issue of takeoff, everything. All of that was very stressful." Duggan feared that on the trip north, the stress would induce shipping fever -- a pneumonia-like affliction, well-known to horse breeders and veterinarians, that can kill. Duggan considered sedating Goldie -- but talking to her and offering her bottle calmed her down, and no sedative, which carried its own risks, was needed. "The same way as if I'm flying with my own child," the veterinarian explained. Three-month-old Goldie also found comfort in her ball and teddy bear. Soon, she was asleep.

Skirting a storm, the plane returned to Worcester at about 9 p.m. Goldie was transferred to a van and driven to Sachs's lab, where she was placed -- with her bottle, ball, and teddy bear -- in a cage lined with lambs wool. The cage provided Goldie with a constant flow of filtered air, to keep the dust and germs away. Duggan settled the pig in and hand-fed her a dinner of fruit. It was nearing midnight when he dimmed the lights. "Goodnight, I'm off to bed," Duggan said. "See you in the morning." Goldie passed a restful night and was happy and playful at breakfast that morning.

Duggan told the group in the corridor: "She does interact well with people." It would be fine to pet her, he said -- with gloves.

"I don't think you need to pet her," Sachs said.

"It should be minimized," Duggan agreed. "It shouldn't be like a circus back there."

Animal rounds ended with a review of the current xeno experiments, which involved transplanting organs from pigs that had the sugar gene into baboons, whose immune systems are similar to a human's. Although Goldie and others like her that would be produced seemed the best chance of solving the xeno puzzle, other approaches using other protocols and another type of genetically modified pig had been tried over the years, at Sachs's center and elsewhere. The best success was a transgenic pig heart that Cooper transplanted into a baboon that beat for 139 days before being rejected. These particular pigs were not Sachs's own: he had gotten them from Imutran, a once-promising British xeno firm that had developed them in the 1990s.

But neither Cooper nor anyone else had been able to get another pig heart to last anywhere close to as 139 days, and he, like his boss, believed the best chance was with double-knockout pigs.

She was a pretty shade of pink like the other pigs, and she was uncommonly cute. She bore an eerie resemblance to Babe.

Sachs and the senior members of his staff pulled on shoe covers -- not for their benefit, but to protect the animals from germs that shoes can carry -- and passed through an electrically operated door into the larger of the lab's two pig chambers. The room had dozens of cages, some plastic-walled, some with steel bars. Most were occupied: one pig per cage. Some pigs still wore bandages from recent operations, and most had intravenous lines for administering medications and taking blood samples. The room was clean and bright with only the faintest trace of odor. Sachs treated his animals with compassionate care, for they were his most valuable tools. Inspections by federal and hospital agents, who often showed up unannounced, rarely disclosed infractions.

Goldie stood in her special cage, her ball and teddy bear at her feet. "Should be a different color or something, don't you think?" said a scientist. But she was a pretty shade of pink like the other pigs, and she was uncommonly cute. She bore an eerie resemblance to Babe.

Sachs put on rubber gloves and reached into the cage. Goldie came to him without hesitation.

Sachs patted the animal, felt her ears, tickled her snout. Goldie snorted agreeably, but Sachs said nothing. He was listening to her breathing to confirm that her lungs were clear -- that she was healthy. She was.

And he was thinking about the animal's importance. "A lot of hopes are riding on this pig," he said.

A magnet held Goldie's paper cutout to the board at large animal rounds the following Friday, Valentine's Day, but it would be a fleeting presence: this was the last such meeting before, as Duggan put it, "Goldie gives it up for science."

On Wednesday, February 19, the animal's heart, kidneys, thymus, and bone marrow would be transplanted into four separate baboons. As far as anyone in Boston knew, nothing like this had been attempted before -- five animals, four operating tables, six surgeons, six technicians and assistants, one operating room supervisor, all on one day. Just getting the organs moved into their proper places would be an accomplishment. Sachs saw no value in a rehearsal -- these were accomplished surgeons, after all -- but he, Cooper, Yamada and the staff had spent hours devising a written plan.

"Only people who are really essential go into the OR that day," Sachs said. "Don't come in unless you're asked."

Another concern was preventing publicity of next Wednesday's events: Sachs did not want word leaking out to reporters or animal rights activists. He ordered inquiring calls be referred to him.

"When the time comes," Sachs said, "I want the news to be correct."

But as it would happen, reporters and animal rights activists would prove to be among the least of the scientist's concerns.

July 2, 2020

Wiping the Slate Clean

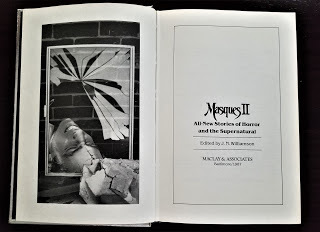

I do not have the digital files, so photos of the pages will have to do!

June 27, 2020

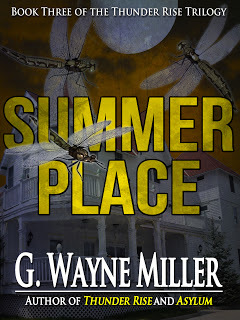

Summer Place: Book Three of the Thunder Rise Trilogy

Chapter 67

Something was wrong. Something was very wrong. Caleb felt it as soon as he and his sister crossed the threshold into the kitchen of the summer place. He felt it grow as they went room to room, calling their father’s name, getting no answer — only a spooky echo of Caleb’s voice that was like the time Mommy had taken them to the Museum of Art and he’d shouted down a long marble corridor. He could see the Dark Thoughts now, quite plainly: They’d returned from their hiding place the instant they’d come inside.

Something was wrong.

But what?

Well, Daddy was missing, that was wrong. That was scary, if you thought about it too much, which Caleb tried not to. He kept telling himself that Daddy must be in the barn, or maybe out looking for Paul, or getting help somehow. And he’d be back very, very soon.

No, it wasn’t just Daddy’s absence that had brought the Dark Thoughts out of their hiding place. It wasn’t the by-now-dull ache from where he’d been bitten. Bites were no fun, but they hurt a less than bee stings, and if you tried really, really hard — if you did what Daddy always advised, “grin and bear it” — you could almost forget about them.

So what could it be?

The house. It had to be something about the house. Standing on the second-story landing, holding his sister’s hand, looking down the stairs into the brilliantly illuminated living room, Caleb struggled to figure what, exactly, was wrong with the house.

On the surface, nothing was different.

All the furniture was where it belonged. His and Sarah’s toys were where they were supposed to be, in their rooms. There were dirty dishes in the kitchen sink. The candle they’d been burning was still in the living room, along with the empty cans of Raid. And those bugs — the dead bodies of the ones they’d killed were scattered around, and there were a few new live ones, which Caleb had dispatched to bug heaven with his remaining Raid. If anything, the house should have been less creepy — the power was on, and as they’d moved through the house, Caleb had turned on every single light. It was like daytime in here now, so bright there didn’t seem to be any shadows.

No, it should have felt OK. Should have felt good.

But it didn’t.

It was like someone was watching them. Like the house was watching them. Like the walls and the ceilings had trick mirrors and there was someone behind them, following them as they moved, listening, listening to what was inside his head... the Dark Thoughts... and waiting...

waiting.

“Daddy?” he called, his voice thinning. “Daddy are you up there?”

He had not opened the door to the attic yet. Except for the barn and cellar, which wasn’t sure he wanted to check, the attic was the last place left. The entire first floor, the bedrooms, bathroom, even behind the sofa and in the downstairs closet — he’d looked, and Daddy wasn’t there.

Don’t have to check the attic, he thought. Daddy wouldn’t have gone up there.

But what if he had? What if, for some reason that made sense only to a grownup, he’d climbed up there and had an accident? Like Caleb had had that accident under the barn? What if he was up there on the floor right now, unconscious, needing to be rescued, the way Caleb had needed to be rescued?

For the first time, it occurred to Caleb that Daddy might not be OK. The realization terrified him. So many other bad things had happened this weekend, but Daddy — Daddy had been all right. Daddy had been invincible.

I have to go up. Even Mommy, mad as she was at Daddy, would have insisted he go up if she’d been able to advise him.

“Sarah?” he said, his voice a whisper.