G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 9

June 17, 2020

An Uncommon Man: The Life and Times of Senator Claiborne Pell

This 12th free offering is the prologue to "An Uncommon Man: The Life and Time of Senator Claiborne Pell," edition published in 2011 by University Press of New England, in Kindle and hardcover editions.

Prologue: A Cold Winter Day

Dawn had barely broken when the crowd began to build outside Trinity Episcopal Church. A frigid wind blew and snow frosted the Newport, Rhode Island, ground. Police had restricted vehicular traffic to allow passage of the motorcade carrying a former president, the vice president-elect, and dozens of U.S. senators, representatives and other dignitaries who would be arriving. Men in sunglasses with bomb-sniffing dogs patrolled the church grounds, where flags flew at half-mast.

It was Jan. 5, 2009, the day of Senator Claiborne deBorda Pell’s funeral.

Some of those waiting to get inside Trinity Church were members of Newport society, to which Pell and Nuala, his wife of 64 years, had belonged since birth. Some were working-class people who knew Pell as a tall, thin, bespectacled man who once regularly jogged along Bellevue Avenue, greeting strangers and friends that he passed. Some knew him only from the media, where he was sometimes portrayed, not inaccurately, as the capitol’s most eccentric character, as interested in the afterlife and the paranormal as the federal budget. Some knew him mostly from the ballot booth or from programs and policies he’d been instrumental in establishing. First elected in 1960, the year his friend John F. Kennedy captured the White House, Pell served 36 years in the U.S. Senate, 14th longest in history as of that January day. His accomplishments from those six terms touched untold millions of lives.

Pell died at a few minutes past midnight on Jan. 1, five weeks after his 90th birthday and more than a decade after the first symptoms of the Parkinson’s Disease that slowly stole all movement and speech, leaving him a prisoner in his own body. He died, his family with him, at his oceanfront home -- a shingled, single-story house that he personally designed and which stood in modest contrast to Bellevue Avenue mansions and Bailey’s Beach, the exclusive members-only club that has been synonymous with East Coast wealth since the Gilded Age. Pell, whose colonial-era ancestors established enduring wealth from tobacco and land, and Nuala, an heiress to the A&P fortune, belonged to Bailey’s. But the Pells were unflinchingly liberal and Democratic. In the old manufacturing state of Rhode Island, where the American Industrial Revolution was born, blue-collar voters embraced their aristocratic senator with the unconventional mind.

The motorcades passed the waiting crowd, which by 9 a.m. was more than a block long. Former President Bill Clinton stepped out of an SUV and went into the parish hall to await the procession to the church. Vice President-elect Joe Biden and Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, whose malignant brain cancer would claim him that summer, followed Clinton. A bus that met a jet from Washington brought more senators, including Majority Leader Harry Reid and Republicans Richard Lugar and Orrin Hatch. Pell’s civility and even temper during his decades in the Senate earned him the respect of his colleagues. “I always try to let the other fellow have my way,” is how Pell liked to explain his Congressional style. It was the best means, he maintained, to “translate ideas into actions and help people,” as he described the heart of his legislative style. He had learned these philosophies from his father, a minor diplomat and one-term Congressman who had cast an inordinate influence on his only child even after his own death in the first months of John F. Kennedy’s presidency.

The doors to Trinity opened and the crowd went in, filling seats in the loft that had been reserved for the public. The overflow went into the parish hall, to watch the live-broadcast TV feed. Led by their mother, Nuala and Claiborne’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren took seats near the pulpit. The politicians settled in pews across the aisle. The organ played, the choir sang, and six Coast Guardsmen wheeled a mahogany casket draped in white to the front of the church.

From early childhood, Pell had loved the sea, an affection he captured in sailboat drawings and grade-school essays about the joys of being on the water. When he was nine, he took an ocean journey that would influence him in ways a young boy could not have predicted: traveling by luxury liner with his mother and stepfather, he went to Cuba and on through the Panama Canal to California and Hawaii. “It was the most interesting voyage I have ever taken,’’ he wrote, when he was 12, in an essay entitled The Story of My Life. After graduating from college in 1940, more than a year before Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Coast Guard, pointedly remaining in the reserves until mandatory retirement at age 60, when he was nearing the end of his third Senate term.

In the many stories that had accompanied his retirement from the Senate, Pell had named the 1972 Seabed Arms Control treaty, which kept the Cold War nuclear arms race from spreading to the ocean floor by prohibiting the testing or storage of weapons deep undersea, as among his favorite achievements. He pointed also to his National Sea Grant College and Program Act of 1966, which provided unprecedented federal funding of university-based oceanography. And one of his deepest regrets, he said 1996, was in failing to achieve U.S. ratification of the international Law of the Sea Treaty, which establishes ocean boundaries and protects global maritime resources.

In planning his funeral, Pell requested a ceremonial honor guard from his beloved service. The Coast Guard granted his wish -- and added meaning when selecting Pell’s pallbearers. Two of the six had graduated college with the help of Pell Grants, the tuition-assistance program for lower- and middle-income students that Pell called his greatest achievement. Since their inception in 1972, the grants by 2009 had been awarded to more than 115 million recipients. Without them, many could not have earned a college degree.

*********

Kennedy left his wife, Vicki, in their pew and walked slowly to the pulpit.

In his nearly eight-minute eulogy, the last substantial speech the final Kennedy brother would make, Ted talked of Pell’s fortitude when he and Nuala lost two of their grown children. His hands trembling but his voice strong, he spoke of his family’s long relationship with Pell, which began before the Second World War -- and of his own friendship with Pell and their 34 years together in the Senate. He spoke of Pell’s political support for his president brother and his support for hos own son, Patrick Kennedy, representative from Rhode Island’s 1st Congressional District, which includes Newport. He recalled the summer tradition of sailing with Vicki on his sailboat, Maya, from Long Island to Newport, enroute to their home in Hyannisport on Cape Cod. During their overnight visits with the Pells, Claiborne, who owned no yacht, relished sailing on Ted’s sailboat Mya, even after Parkinson’s Disease left him in a wheelchair and unable to speak. “The quiet joy of the wind on his face was a site to behold,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy closed with tribute.

“During his brilliant career, he amassed a treasure trove of accomplishments that few will ever match,” Kennedy said, citing the Pell Grants, Pell’s 1965 legislation that established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Seabed Treaty. It was Claiborne Pell who advocated the power of diplomacy before resorting to the power of military might. And it was Claiborne Pell who was a environmentalist long before that was cool. Claiborne Pell was a senator of high character, great decency and fundamental honesty. And that’s why he became the longest serving senator in the history of Rhode Island. He was a senator for our time and for all time. He was an original. He was my friend and I will miss him very much.”

Kennedy returned to his pew Clinton took the pulpit of the historic old church, which has overlooked Newport Harbor since 1726. Drawing laughter, the former president told of first seeing Pell: in 1964, when he was a freshman at Georgetown University living in a dorm that overlooked the backyard of the Pells’ Washington home.

“I was this goggle-eyed kid from Arkansas. I had never been anywhere or seen anything and here I was in Washington, D.C., and I got to be a voyeur looking down on all the dinner parties of this elegant man. So I got very interested in the Pell family. And I read up on them, you know. And I realized that they were a form of American royalty. I knew that because it took me 29 years and six moths to get in the front door of that house I’d been staring at. When I became president, Senator and Mrs. Pell, who had supported my campaign, invited me in the front door. I received one of Claiborne Pell’s courtly tours of his home, which was like getting a tour of the family history. There were all these relatives he had with wigs on. Where I came from only people who were bald wore wigs. And they weren’t white and curled. It was amazing.

“And even after all those years, I still felt as I did when I was a boy: that there was something almost magical about this man who was born to aristocracy but cared about people like the people I grew up with.”

He cared, too, Clinton said, for the citizens of the world. Clinton spoke of Pell’s belief that together, nations can solve the planet’s problems -- a belief that took root in his childhood travels and solidified in 1945 in San Francisco, where delegates of 50 countries drafted the U.N. Charter. Pell served as an assistant for the American delegation.

“Every time I saw him -- every single time -- he would pull out this dog-eared copy of the U.N. Charter,’’ Clinton said. “It was light blue, frayed around the edges. I was so intimidated. There I was in the White House and I actually went home one night and read it all again to make sure I could pass a test in case Senator Pell asked me any questions. But I got the message and so did everybody else that ever came in contact with him: that America could not go forward in a world that had only a global economy without a sense of global politics and social responsibility.”

The ex president ended with a reference to ancestors.

“The Pell family’s wealth began with a royal grant of land in Westchester County where Hilary and I now live,” he said. “It occurred to me that if we had met 300 years ago, he would be my lord and I would be his serf. All I can tell you is: I would have been proud to serve him. He was the right kind of aristocrat: a champion by choice, not circumstance, of the common good and our common future and our common dreams, in a long life of grace, generous spirit, kind heart, and determination, right to the very end. That life is his last true Pell Grant.”

Despite the work of transitioning from the Bush to the Obama administration, Biden had taken the morning off to eulogize the man who befriended him when he arrived in Washington in 1972 as a 29-year-old senator-elect. Biden had just lost his wife and baby daughter in a car accident. “You made your home my own,” Biden said, turning to Nuala. In the Senate, Pell became Biden’s mentor.

The vice-president-elect, who served with Pell on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, enumerated more of Pell’s accomplishments, including legislation that helped build Amtrak and a lesser-publicized campaign against drunk driving -- a cause Pell embraced when two of his staff members, including one central in the fight for Pell Grants, were killed by drunk drivers. In these efforts and in all of his Congressional dealings, Biden said -- and all of his campaigns, none of which he ever lost -- Pell brought a gentlemanly sensibility that seemed outdated in an era of hot tempers and mud.

“I’m told, Ted,” Biden said, “that your brother, President Kennedy, once said Claiborne Pell was the least electable man in America -- a view that, I suppose, was shared by at least six of his opponents when he ran for the United States Senate over the course of 36 years.”

Laughter filled Trinity Church.

“I understand how people could think that,” Biden continued. Here was a graduate of an exclusive college-preparatory school and Princeton, who later earned an advanced degree from another Ivy league School, Columbia -- a man born into wealth who married into more and had traveled the world many times over before ever seeking office.

“He didn’t have a great deal in common, I suspect, with many of his constituents in terms of background, except this: I think Claiborne realized that many of the traits he learned in his upbringing -- honesty, integrity, fair play -- they didn’t only belong to those who could afford to embrace the sense of noblesse oblige. He understood, in my view, that nobility lives in the heart of every man and woman regardless of their situation in life. He understood that the aspirations of the mother living on Bellevue Avenue here in Newport were no more lofty, no more considerable, than the dream of a mother living in an apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant.…each of those mothers wanted their children to have the opportunity to make the most of their gifts and the most of their lives.”

Biden told some favorite stories, drawing laughter with the one about Pell going for a jog on a trip to Rome dressed in an Oxford button-down shirt, Bermuda shorts, black socks and leather shoes -- an image of Pell that his friends and family knew well. Sweat suits and Nikes were not Pell’s style.

“To be honest, he was a quirky guy, Nuala,” Biden said.

The mourners laughed -- Nuala most appreciatively, for she understood best what Biden meant. For two thirds of a century, she had experienced his odd dress, his obsession with ancestors, his bad driving, his frugality, his fascination with ESP and the possibility of life after death, his manner of speaking, as if he had indeed traveled forward in time from the 1600s, when Thomas Pell was named First Lord of the Manor of Pelham. These traits were all part of his charm, which sometimes annoyed but often amused his wife. This and his handsome looks and ever-curious mind were why Nuala had fallen in love when they met in the summer of 1944, when she was 20, and why she married him four months later. Claiborne Pell was different. Unlike most other young men of her circle, he aspired to be something more than a rich guy who threw parties.

Biden’s eulogy was nearing a half hour, but he had one more story.

“One day, I was sitting in the Foreign Relations Committee room waiting for a head of state to come in.” Pell was there.

“He took his jacket off, which was rare -- I can’t remember why -- and I noticed his belt went all the way around the back and it went all the way to the back loop. I looked at him and I said, `Claiborne, that’s an interesting belt.’

“He said, `it was my father’s.’ And his father was a big man.

“I looked at him and I said, `Well, Claiborne, why don’t you just have it cut off?’

“He unleashed the whole belt and held it up and said, `Joe, this is genuine rawhide.’ I’ll never forget that: `This is genuine rawhide.’ I thought, God bless me!”

**********

Almost a half century before, Pell’s father, Herbert Claiborne Pell Jr., had been remembered here in Trinity Church after dying of a heart attack in Munich, Germany, on July 17, 1961. A plaque in Herbert’s name hung from the wall behind the pulpit from which distinguished men now eulogized his son. “Lay Reader in this Church,” the plaque read. “Kind and beloved Public Servant & Scholar. Member 66th United States Congress. United States Minister to Portugal and to Hungary.”

Elected from Manhattan’s Silk Stocking District, Herbert served one term, from 1919 to 1921, in the U.S. House of Representatives. Losing re-election, he became chairman of the New York’s Democratic State Committee, remaining until 1926. His friend President Franklin Delano Roosevelt named him minister to Portugal in 1937, and then, in 1941, minister to Hungary. When Hitler’s war forced Herbert to return home, Roosevelt named him a delegate to the United Nations War Crimes Commission.

Herbert was more an intellectual than a politician -- a bibliophile, art collector and writer whose inheritance allowed him to do whatever he desired. Herbert owned properties in Manhattan, New York state and Newport, and kept a staff that included a chauffeur and a personal secretary. He traveled extensively, preferring to stay at the many European and American men’s clubs to which he belonged. But of all his passions, none rivaled the interest he took in his only child.

Herbert made the decisive decisions about Claiborne’s education. He critiqued the young boy’s penmanship and tennis serve and brought Claiborne along with him on his world adventures. He used his considerable influence in attempting to place the young man into the military and, after the war, public service. He advised Claiborne on matters of business, politics, ethics and love. He responded at length when Claiborne sought his counsel, as Claiborne regularly did. He established the trust fund that would free his son, as his parents had freed him, from the concerns of earning the daily bread. He taught his son that the family had maintained its wealth since the 17th Century not with the sort of obscene extravagance that had eroded many a Gilded-Age fortune, but by living a refined life without want, but with limits that protected the base for subsequent generations.

“Financial independence, even the humblest, is not a necessity but it is a most desirable concomitant of spiritual and intellectual freedom,” he wrote to his son in 1939, the year Claiborne turned 21 and Herbert, 55, gave him control of the trust. With the money came words of fatherly wisdom. “I strongly advise you not to make the mistake I made: Do not accumulate possessions. I do not say that if I had my life to live over again I would own nothing except my clothes, but I would give a lot of heart to following that drastic course than to doing what I did.”

Claiborne was six months into his first Senate term when Herbert died, without warning or goodbye, 4,000 miles away. Claiborne flew to Germany to oversee his cremation, returning with his father’s ashes, which were scattered in the ocean off Jamestown, an island community next to Newport. Already obsessive about Pell family ancestry, as Herbert had been, Claiborne decorated his Washington and Newport homes with paintings and mementoes of his father. He began wearing his clothes, much too big for him. Herbert stood six-feet-five-inches tall and weighed nearly 250 pounds; at six-foot-two and 156 pounds, Claiborne was physically slight by comparison.

But it was not the only measure by which Pell likened himself to his father -- and in which he saw himself short. This senator who would draw many of the nation’s political elite to his funeral was never convinced he was the man his father had been. It was a judgment that would both drive and haunt Pell, in his legislative career and personal life. It was central to the fascination he developed with the paranormal and his largely unpublicized but obsessive quest to learn what, if anything, lay beyond death -- and whether it was possible to communicate to those who were departed.

If it was, perhaps he could reach his father, who had not lived to see what his son had become. Perhaps he could receive Herbert’s approval.

*******

Senator Jack Reed, who received Pell’s endorsement and succeeded him in the Senate, joined the other eulogists in praising his predecessor’s accomplishments. Like Biden, Reed had a funny story related to Pell’s forbears. It took place in 1992, when Reed, a freshman member of the House, was waiting with Pell for President George H. W. Bush to sign the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, which provides the funding for Pell Grants. Reed, the son of a janitor and a housewife, had grown up admiring Pell.

“Now, Claiborne was a master of many things, but small talk was not one of them,” Reed told the mourners. “We got through the weather and the traffic pretty quickly and we were rapidly moving into the area of awkward silence. But I was sitting next to one of my heroes and felt compelled to keep talking so I blurted out:

“ `Are you going up to Rhode Island this weekend, senator?’

“Claiborne perked up noticeably and said: ‘Well, no, Jack, I’m going up to Fort Ticonderoga for a family reunion.’

“I was a bit thrown by the response, so I said: `Why would you ever go up there for a family reunion?’

“ `Well, Jack, you see, we own it.’ ”

Laughter filled the church.

``For a moment, I thought he was pulling my leg,” Reed continued. “But that was not Claiborne Pell. As President Bush entered, we stood up and I realized one more reason why Claiborne Pell was so unique and so deserving of trust: he owned his own fort.”

The last to speak was Nick Pell, 31, Claiborne’s oldest grandson. Tall and slim like his grandfather, Nick listed the qualities he would remember best about his grandfather: his stubborn resolve, his patriotism, and his generosity to his family and constituents, though not in the ordinary sense to himself. Pell could have bought many things, but he had heeded his father’s 1939 admonition about possessions.

“My grandfather will be remembered by those who loved him for his extreme frugality,” Nick said. “For some, this may be a negative trait, but in true New England WASP form, my grandfather was actually quite proud of his ability to conserve resources. He served famously bad cigars and wine. He jogged in actual business suits that had been reluctantly retired. He drove a Chrysler LeBaron convertible, which was outfitted with tattered red upholstery, a roof held together with duct tape, and an accelerator which was so old it required calf-strengthening exercises just to depress the pedal. When it finally fell apart, he replaced it with a Dodge Spirit which he had purchased used from Thrifty Rental Car. I guess Hertz was too expensive.

“When my sister lived with him in Washington for the summer, he used to make her gather hors d’oeuvres from cocktail parties as he’d just as soon not pay for dinner. He used to say `food is fuel’ and `never turn down a meal, as you never know when your next one will come.’ He was able to strike the perfect balance between a gentleman and a man in tattered suits living from meal to meal.”

Nick did not repeat his grandfather’s Congressional achievements, some of which came after years of work. What he would remember with deepest respect was his grandfather’s inner strength as his Parkinson’s advanced and freedom slipped away.

“He won some impressive battles during his time on the hill,” the grandson said, “but in my mind, his greatest show of strength was his battle with his failing health. He had been sick for well over ten years and while his body gave out long ago, his will to live was of mythic proportions. He showcased what we in the family call ‘warrior spirit’ -- and his resolve to live and enjoy time with the people he loved most, his family, his friends, and his constituents. It’s as if God had told him years ago that his time was up and he just said, ‘Not until I’m ready.’ ”

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

June 6, 2020

Toy Wars

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I am regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at this time!

The 11th free offering is the first chapter of "Toy Wars: The Epic Struggle Between G.I. Joe, Barbie and the Companies That Make Them," first edition published in 1998 by Random House, with other subsequent print and Kindle editions.

I

The hearse bearing the body of Stephen Hassenfeld left New York the afternoon of June 26, 1989, and reached Mitch Sugarman's Mt. Sinai Memorial Chapel in Providence, Rhode Island, by nightfall. After being washed in accordance with ancient Hebrew custom, Stephen was dressed in a burial shroud, a simple garment that is white, to symbolize death's democracy, and pocketless, a reminder that nothing material from this world survives to the next. At the family's request, a business suit was placed over the shroud. Stephen was laid out in Sugarman's finest mahogany casket and wheeled into the chapel, where a red memorial candle with a Star of David burned. The coffin was closed. Dark-haired and handsome in life, an impeccable dresser with exquisite taste in everything, Stephen in death was devastated by AIDS, which had finally claimed him after almost a month in a coma in Manhattan's Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.Stephen's callers the next day were only those closest to him. His mother, Sylvia, was in from New York, along with his sister, Ellie Block; during Stephen's hospitalization, the details of which they'd kept fiercely private, they'd maintained a bedside vigil. Stephen's life partner and longtime business associate, Robert Beckwith, came, as did Leslie Gutterman, Rhode Island's foremost rabbi.As midnight neared and his mother and sister wearied, Alan insisted they leave, to get what rest they could. Jewish tradition requires the deceased be attended until burial, and Sugarman ordinarily hired elderly holy men for the ritual. But Alan did not want Stephen with strangers. He'd insisted on watching, on reciting the Book of Psalms, by himself. Sometime in the pre-dawn hours, he put his book down, opened the casket, and tucked into a pocket of Stephen's suit the notes and pictures his nieces and nephew wanted their uncle to have. Alan had a note of his own and he placed that in the pocket, too. Then he removed one of his rubber bands and placed it on Stephen's wrist, to be worn for all eternity.

Through his tears, Alan spoke of his love for his only brother and best friend, seven years his senior. His thoughts wandered to their childhoods, here on Providence's East Side -- the fancy Porsche Stevie had driven, his reputation as a debater at the prestigious Moses Brown School, how Stevie always came to the rescue when Alan's shenanigans landed him in trouble with mom. He pondered the tragedy of Stephen's disease, which Stephen had confirmed only to Beckwith. Only when Stephen was on his deathbed did his family confront the truth behind the maladies that had slowly consumed him until, at his last public appearance, Hasbro's annual meeting in his beloved New York showroom, this man who'd once regularly worked 18-hour days was exhausted by a routine thirty-minute presentation. Forty-seven years old, Stephen had died without finding the way to unburden himself.

He was called the father of the modern toy company, but that hardly did Stephen D. Hassenfeld justice. In 1980, when Stephen became Hasbro's chairman and chief executive officer, toy companies were but a quirky footnote on Wall Street. Investors were wary of businesses built on the whims of kids, for good reason: One big hit and men became millionaires overnight, one bomb and bankruptcy beckoned. Hasbro had been no exception, having made tremendous profits in the mid-sixties with the introduction of G.I. Joe, and then sputtering into the seventies as Joe's popularity waned. Hasbro lost more than a million dollars in 1978; two years later, it made a modest five million, its stock traded at but six dollars a share, and revenues were only $104 million. Mattel, the industry leader, was eight times as big, and vastly more profitable.Under Stephen's leadership, Hasbro in the next five years surpassed $1.2 billion in sales, clobbering Mattel, whose investments outside of traditional toys had left it deeply in debt. Forbes magazine rated Hasbro first in a thousand-corporation survey of increased value during that tumultuous period, well ahead of other high flyers such as Wal-Mart and Berkshire Hathaway. Alan had been a force in all this, but a less potent one than Stephen. President and chief operating officer, he was primarily responsible for international, the side of the business he'd joined after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania, where he'd majored in creative writing. Stephen involved Alan in major decisions and both took pains to describe their relationship as teamwork, an accurate description; until Alan had married this spring, they'd even shared a house in Rhode Island, home of corporate headquarters, and apartments in Palm Beach and New York. But there was never doubt who was in control, never suspicion the younger brother coveted the older's job, for truthfully he did not. ``It's the old Chinese philosophy,'' Alan would say. ``Two tigers can't live on the same hill.''

•

Until cardiac arrest sent him into irreversible coma, Stephen had believed he would recover. A wonder drug would be found, a miraculous new therapy perfected, something. He'd never discussed succession at Hasbro with Alan or anyone else. Stephen had confidence in his brother's potential, but he'd never wanted to believe he would be tested this way.Should I?Alan was talking aloud again. In the scented shadows of the funeral home, he imagined Stephen would respond.How tempting it was to simply walk away. A millionaire many times over, Alan could return to writing, an earlier passion he still carried within. He could devote himself to philanthropy or pursue his distant dream of being a diplomat or holding political office. Alan had never shared his brother's single-minded focus. Life for him was a great feast, meant to be sampled in its many delicious varieties.What would Stevie or their late father, Merrill, Stephen's predecessor at Hasbro, have wanted him to do? For that matter, what would their grandfather, Hasbro's founder, have thought? It was difficult to imagine that any of the Hassenfelds, even soft-hearted Merrill, would have approved of the final brother simply walking away. But Alan had someone else to consider: his wife, Vivien, a granddaughter of Prussian nobility who'd schooled in England and built a successful Hong Kong design firm. She'd married Alan, barely two months ago, expecting to continue her cosmpolitan lifestyle, not be anchored in Rhode Island, a post-industrial backwater that had no charm she could discern, except, perhaps, Newport. Alan knew Vivien would support any decision he made, but her happiness was a concern he could not blithely ignore.Alan didn't question where mom stood. He never had, not through his youth or later at Hasbro, when, regardless of where she was in the world, she telephoned her sons at least daily. Sylvia was a noted philanthropist, prominent in domestic and international Jewish causes, but no small share of her stature rested on the foundation of Hasbro. It mattered not that, unlike her firstborn, Alan had come reluctantly to the firm and had remained contentedly in Stephen's shadow. Alan was the only one she had now in a position of corporate power, for her daughter Ellie, herself a philanthropist, was of a generation whose women were kept from the executive suite.And if he did seek the chairmanship of Hasbro -- he supposed it was his for the asking, although he could not be certain until the board met -- how would he fill this void Stephen had left? Alan's strengths were product, merchandising, manufacturing, and overseas. He knew little about balance sheets and investor relations -- Wall Street, the treacherous soil on which the legend of Stephen had grown. The prospect of following him there was terrifying.As dawn came, Alan thought he could hear Stephen giving him advice. Alan accepted it. ``He would have killed me,'' Alan said, ``if I had basically thought of anything different.''

•

From the funeral parlor, Stephen was taken to his home in Bristol, on the east shore of picturesque Narragansett Bay. Stephen was no sailor, but during the America's Cup campaign of 1983, which was staged from Newport, he'd chartered three large sailing vessels for the exclusive summer-long use of business associates, family and friends. Alan kept a photograph of him with his brother on one of those long-ago cruises on his desk.Alan placed white roses on the casket and he and the small gathering of family and friends bid Stephen farewell. The hearse returned to Providence, to Temple Emmanu-el, where bronze tablets and a stained-glass window inscribed with the names of Hassenfelds attested to the family's prominence for most of the century. Stephen's senior executives awaited the deceased in the warmth of the summer day. Of the innermost circle, only Robert Beckwith was not standing with them, was not a pallbearer; the Hassenfelds had not asked him. But as he ascended the temple steps, he was hugged by all of Stephen's senior people, each of whom Stephen had made a wealthy man.Stephen A. Schwartz, chief marketing executive during the years of fastest growth, had been instrumental in returning G.I. Joe from retirement in 1982 -- the single most critical factor in building Hasbro's huge cash reserve, which Stephen had applied to acquisitions, which in turn brought growth. Schwartz had a tremendous ego, but it was not undeserved. He was smart and stubbornly ambitious, a fast-talking native New Yorker endowed with great product sense. Two more of the industry's most profitable lines of the 1980s, Transformers and My Little Pony, had been introduced by Hasbro on his watch.Lawrence H. Bernstein stood next to Schwartz, his close friend. Bernstein was the best salesman Hasbro had ever had -- an exceptionally entertaining man whose jokes and mannerisms were reminiscent of Sid Caesar, a comic he'd adored growing up in '50s Brooklyn. Bernstein could make the unique claim of having coaxed Stephen, after too much wine, into reenacting a Marx Brothers routine at a company gathering. The Three Musketeers is what Bernstein had called himself, Schwartz and research director George A. Dunsay, no longer with Hasbro. Standing there, consumed by grief at the loss of a man he loved, Bernstein could not possibly have imagined what fate would soon befall the surviving two of the Three Musketeers.Barry J. Alperin, executive vice president and the only officer beside Alan to serve on the board at that time, was the lone intellectual on the temple steps. An aficionado of ballet, opera and theater, as Stephen had been, Alperin had grown up in Providence, where his family's philanthropy brought him into contact with the Hassenfelds. Alperin was an attorney, a bespectacled man steeped in the arcana of acquisition law. Before his death, Stephen had given Alperin a new responsibility in marketing and product development, including development of a secret video game. Like Bernstein, Alperin could never have guessed what his future at Hasbro held.With Alperin was George R. Ditomassi Jr., Stephen's games vice president, entrusted with Candy Land, Chutes and Ladders, and other timeless jewels. Ditomassi had come to Hasbro with Stephen's acquisition of Milton Bradley, America's premier maker of games and puzzles. Dito, as he was known, had style that rivalled Stephen's. He was that rare man who could wear gold without seeming tacky or pretentious.And then there was Al Verrecchia, who knew more about the business than anyone but Stephen himself.Of all the chairman's men, Verrecchia most looked the part of senior executive. Six-foot-three, broad-shouldered and fit, and uncommonly handsome, Verrecchia favored suits and wing-tip shoes. Employees sometimes joked that his hair must obey different laws of physics, for a strand was never out of place. ``Make sure your hair is combed and your shoes are shined,'' his grandmother had said in advice he'd taken to heart, ``for those are the first two things people see.'' Twenty-five years with Hasbro and recently promoted to president of manufacturing, Verrecchia had no equal with numbers. Many an underling had experienced the chill when he perched his reading glasses on the tip of his nose, took up his mechanical pencil, ruler and calculator, and started into their business plans. Verrecchia knew the underside of Hasbro: the late '60s and early '70s, when Merrill, president, had been forced to put up his personal property as collateral on high-interest loans needed to cover the payroll. It was Verrecchia who'd negotiated those loans, Verrecchia who'd begged resin suppliers for extended terms to keep the molding machines running, Verrecchia who'd analyzed when individual paychecks were cashed so that he could dole out the precious dollars to cover them. Despite their grief, Stephen's senior managers had not lost sight of succession. Few doubted the board would deny Alan the chairmanship if he sought it, but they had few clues about how, when, or even if he would restructure the top after taking charge. Alan's U.S. office was next to his brother's at world headquarters, and he was everywhere at Toy Fair, but there was an ethereal quality to him. With his international duties, he was always traveling, and when he was home, he was as likely to regale them with tales of expeditions through early post-Mao China as with marketing strategies for toys. Alan's closest confidants at the company were his mother and brother, and his wife to most was a stranger. No one knew his vision for Hasbro, because he'd never had to spell one out.

•

In his eulogy, Rabbi Gutterman spoke to more than company executives, for Stephen Hassenfeld would long be remembered for more than stock options and dividends alone. Factory workers whose names and birthdays he'd never forgotten were present, together with politicians, religious and community leaders, and beneficiaries of corporate and family philanthropy. ``If every person Stephen Hassenfeld touched with happiness brought a flower to his grave,'' Gutterman said, ``he would sleep tonight beneath a wilderness of roses.''Led by a State Police escort, Stephen's funeral procession was more than three miles long. Those familiar with such matters said it was the largest motorcade in Rhode Island history, surpassing even Presidential visits.

II

Seven days after Alan had thrown the last spade of earth onto his brother's grave, the directors of Hasbro Inc. gathered in a conference room on the mezzanine floor of the company's New York showroom. Alan spoke a few words to the board and he, his mother and Alperin left.Directors were aware that Stephen's hospitalization and persistent rumors about its true cause had troubled Wall Street before the chairman's death. Their concern was compounded by Hasbro's uncharacteristically flat performance in 1987 and 1988. Had Stephen lost his touch -- or was Hasbro simply catching its breath after its extraordinary run? Whatever the case, Alan, this man with the rubber bands always on his wrists, gave Wall Street the jitters. Would he and Sylvia -- they effectively controlled almost a third of Hasbro's stock -- decide to sell? Speculation that the Walt Disney Co., entertainment giant MCA, video-game maker Nintendo, and Mattel were interested in acquiring the firm had led to a run on Hasbro stock. If Hasbro remained independent, more probable after adoption of a so-called poison pill a week after Stephen was hospitalized, would Alan be up to the job? The Wall Street Journal was among the doubters. It recently had described him as his brother's ``shadow.''Behind closed doors, director E. John Rosenwald Jr. had the floor. Newly named vice chairman of The Bear Stearns Companies, one of New York's foremost investment bankers, Rosenwald had been a close friend of Stephen and was the most powerful member of the Hasbro board, after Alan. Shortly after the funeral, Alan had visited him in his Fifth Avenue penthouse. Sitting on the terrace as the sun set over Central Park, Alan had poured his heart out. ``I'd be a little bit different from my brother,'' he told Rosenwald, ``but I know the business and I want my shot.'' Rosenwald related their discussion to the directors, some of whom had spoken privately with him of their inclination to sell Hasbro and, having turned a tidy profit, be done with it. He talked of the depth of Hasbro's management team and praised Alan's intelligence, experience and desire. ``He deserves his shot,'' Rosenwald said. ``His name is on the door, too. He has spent his whole life here and he's ready to roll and he has a plan and I think you should support him.'' The vote was unanimous. Alan returned with Sylvia and Alperin and was congratulated. He had not heard, of course, Rosenwald's caveat about the last Hassenfeld brother -- sole surviving grandson of the founder, a Polish immigrant who'd arrived in America, virtually penniless, at the age of thirteen.``If it doesn't work out,'' Rosenwald had said, ``we can always sell the company.''

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

May 27, 2020

The Horror Show, Fall 1987

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I am regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at his time!

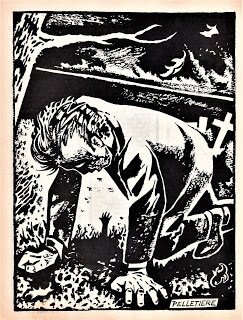

The tenth free offering is “Nothing There,” a short story originally published in the late legendary Dave Silva’s “The Horror Show” and republished in "Vapors: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, V. 2," 2013, Crossroad Press.

BONUS No. 1: Cover of the Fall 1987 “The Horror Show,” when Dave Silva rated me a “rising star,” along with Elizabeth Massie, Poppy Z. Brite, Bentley Little and others. Also, the first page of “Nothing There,” the original illustration, and a two-page interview from three-plus decades ago.

My, how time flies!

Nothing There: Story, illustration, interviews and link to audio drama

During the #coronavirus pandemic, I am regularly posting stories and selections from my published collections and novels. Read for free! Reading is the best at his time!

This is the tenth free offering: “Nothing There,” a short story originally published in the late legendary Dave Silva’s “The Horror Show” and republished in "Vapors: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, V. 2," 2013, Crossroad Press.

BONUS No. 1: Cover of the Fall 1987 “The Horror Show,” when DaveSilva rated me a “rising star,” along with Elizabeth Massie, Poppy Z. Brite, Bentley Little and others. Also, the first page of “Nothing There,” the original illustration, and a two-page interview from three-plus decades ago.

BONUS No. 2: Twisted Pulp’s audio drama based on the story will be broadcast this summer on KKRN radio in northern California, but you can hear it now – including an interview of me on writing, Stephen King, Story in the Public Square and more: https://bit.ly/2XwGFdx

Nothing There

He drove north from Chicago in a rented Honda. The Saturday afternoon traffic was thick and sluggish, like blood through diseased arteries. How polite these drivers seemed. Back in Boston, you couldn't go a block without some idiot trying to nail you. Here, folks signaled when passing. They stayed close to the speed limit. No one tailgated. He supposed it was part of their Midwestern nature to be so courteous. He wondered momentarily what kind of world it would be if everyone were like them.

Before long, the factories and tenements had thinned and then disappeared. The jets in and out of O'Hare had shrunk to distant specks. He passed an amusement park, closed for the season. He saw transmission lines coming down from Canada. It was suburbia now, 7-11 stores and neat little lawns fronting neat little houses. Soon they, too, had faded. Farmhouses took their place. Cornfields and dairy cattle. Silos, rigid and tall, guardians of this rich black soil. He crossed the line and he was in Wisconsin. From here, she'd said, it was only another half hour.

The traffic was weaker now. The November day was, too. High, thin clouds spread across the measureless sky. Another hour, and the sun would be swallowed by the fields. At kitchen tables, dinner would be served. He imagined seeing aproned housewives, their hair done up in curlers and kerchiefs, bending over ovens where hamburger casseroles simmered. He imagined hearing the children, giddy with the thought of Saturday night, and the tired husbands, ready for their evening of rest.

Overhead, the sign said County K, one mile. What a funny name for a road, he thought. County K, like some new brand of cereal. He looked down at the directions he'd scribbled on hotel stationery. Yes, this was it. He eased over into the travel lane, slowed and left Interstate 94. There was the 76 truck stop, just as she'd said. A combination restaurant, gift shop and Greyhound bus stop. A parking lot full of full-sized Fords and Chryslers, with hardly a Toyota in sight. The heartland.

He'd called her after lunch from his hotel room. The first few minutes had been awkward for them both. He could hear the sounds of kids in the background. He told her about his convention. She talked about the weather, unseasonably mild, and unlikely to last, considering Thanksgiving was just around the corner.

``Where are you staying?'' she'd asked.

``The Palmer House.''

``Very fancy.''

``It's OK.''

``No, it's fancy,'' she insisted. ``I've been there. Window- shopping in that big lobby.''

``They have some nice shops.''

``You've done all right for yourself, John,'' she said, trying to mask her bitterness. A trace still showed. ``You always did.''

He didn't answer. Didn't know what he could have said if he'd tried.

``So how'd you find me?'' she asked after shouting at the children to be quiet, Mommy's got a very special call.

``The alumni office.'' They'd been the same class, the class of '96. He'd gone back east after graduation. She'd gone home to Wisconsin, never expecting to hear from him again.

``It's funny.''

``What?''

``That you tracked me down. I tried to find you, you know.''

He didn't. But it didn't surprise him. There was a time he'd actually dreaded her call, but that had passed. During the period he was married, he'd almost forgotten her. It wasn't until after his divorce that he'd thought much about her again.

``I tried several times, as a matter of fact,'' she continued. ``I wrote letters. They kept coming back.''

``I've moved a lot,'' he said. ``The company.''

``It doesn't matter now.''

There was another pause. The words weren't coming easily from either of them.

``I'm divorced, you know,'' she said after a bit.

``I know. I am, too.''

``I've got two children. That's who you hear running around. A boy and a girl.''

``I know,'' he repeated dumbly.

``You seem to have done your homework,'' she said, and he couldn't tell if she was mad or not.``It's all on record at the alumni office,'' he explained. ``Anyone can get it by calling.''

``Did they tell you they were both adopted?'' she asked.

``No.''

``After Bryce, I couldn't have children. Of my own.''

Bryce, he thought. So that's what she called him. Why did she even bother to name him? What could it matter?

``I'm sorry,'' he said. He wished he had a glass of water to get rid of the dryness in his mouth.``I am, too.'' He was surprised at how cold her voice had turned. How suddenly. He didn't remember her like that. He remembered her as soft, pretty, the youngest-looking girl sitting at the back of Economics 101 the morning he first set eyes on her.

``I'm really sorry.''

``Sure.''

There was silence again. It was a bad cell, and he could hear static through the phone.

The child had been stillborn. That much he'd heard years ago from a friend of a friend of a friend.

There had been whispers of some horrible deformity, but he'd never been able to confirm that, never bothered to try. What would have been the gain? What was done was done. All he knew for sure was that Sheryl had carried the baby to term, and he'd come out blue and unbreathing. There was a question of medical malpractice. As far as he knew, it had never come to a suit. That wouldn't have been like her. This had all happened that September, three months after he'd said goodbye.

``So why'd you call, John?'' she asked, breaking the silence.

He'd been ready for this one, but he still didn't have a good answer. Just some private feelings he couldn't share because he wasn't sure what they meant, if they meant anything at all.

``I just thought I should,'' he said. ``I've been thinking about it for a long time.''

``Do you want to see him?'' she asked. ``I think you should see him. Just once. It wouldn't have to be for long.''

He had no idea what she was talking about.

``Who?''

``Bryce. His grave, I mean.''

What a strange idea, he thought. Perverse. Again, the pause was long, uncomfortable. He wished desperately that the call was over, but he saw no way of ending it. It was up to her now.

``I could tell you how to get there. It's not even two hours from Chicago.''

``I--''

``I think you should, John,'' she said sternly. ``I think you owe him at least that. Him and me. Respect for the memory. Respect for the past.''

``Yes,'' he finally said. ``I'd like to.''

She gave him directions. He was reading them again now after stopping at the restaurant to use the men's room. County K six miles west to an intersection. Right on Rowe's Lane about a mile to a seed farm. The cemetery would be just over the next knoll. You can't miss it, she'd said. It's on the highest land around.

He rolled the window down and put the car in gear.

Night wasn't far off, but it seemed to have warmed up since leaving Chicago. The air on his face felt refreshing, like a shower after a bad night's sleep. For some reason, he'd been getting increasingly anxious the last few miles. Strung out. He could feel the excess nervous energy running up and down his body. It was like having too many cups of coffee. His palms were actually sweaty. For the first time since talking to her, he wondered what exactly he'd gotten himself into, and why. He didn't have the answers. That bothered him more than anything. He'd gotten where he had in business by coming up with answers.

County K, a two-lane blacktop, wound off toward the setting sun. There was almost no traffic, only an occasional tractor or pickup truck or stainless-steel tanker carrying milk destined to become butter or cheese. The only buildings were farmhouses and barns. It seemed everyone was flying an American flag. In the Ivy-League East, patriotism smacked too much of Tea Party politics to be worn on the sleeve. Here, it fit.

He found the cemetery without any trouble. From this knoll, you could see for miles and miles over the rolling countryside. It reminded him of a Grandma Moses painting, the fields and outbuildings arranged like patchwork.

He got out of the car and paused a moment, surveying the cemetery.

It was unexpectedly tiny, a postage stamp of graveyards. The only smaller one he recalled ever seeing was one near Concord, Mass., where a handful of Revolutionary War heroes were buried together under white headstones whose inscriptions had worn off over the years. He counted, unconsciously using his finger as a measure. There couldn't be more than a dozen families buried here. One of them was hers, the Andersens. He remembered her telling the story of how the family had come over from Sweden during the great wave of Scandinavian immigration a century ago. They'd been carpenters and masons, these Andersens, and they'd done all right for themselves in the New Land.

The wind had picked up since the truck stop and it was insistent now, brisk but not harsh. In a few short weeks it would deliver the sleet and the snow, but today, on the cusp of fall, it brought only a final reminder of summer. In great sheets, it came whipping across the flat landscape, fragrant with a sweet agricultural odor he did not recognize. He stood, letting the wind caress him. He looked out over the stones, the torn veterans' flags, potted geraniums wilted by the autumn's first frost. The cemetery was surrounded by fields. They were brown, their life gone silently underground to await a more encouraging season.

The heartland. He'd probably eaten food grown around here, maybe from one of these very fields.

Carrying the green bag he'd picked up in the Palmer House lobby, he opened the rusted iron gate and walked uncertainly into the cemetery. That shaky feeling had returned. His lips were dry. He felt suddenly alone, inexplicably embarrassed, like the man in the dream who finds himself in public without any clothes. Let's get it over with and get out of here, he thought. He went directly to the Andersen plot, past the Birds, the Bergmans, the Mondales, the Thompsons. The featured Andersen stone was a towering obelisk, at least twice his height, cut from what appeared to be gray marble, polished and mirror-smooth. The shadow from a leafless tree fell across it in an abstract pattern. Somebody had paid a small fortune for this display, he could tell that. He remembered her father, Ambrose Andersen, a tall, stern man he'd met once. Andersen had made a small fortune in construction, and like many newly wealthy people, he enjoyed spending. He'd probably footed the bill.

Laid out in front of the obelisk were perhaps 25 flat stones, each roughly the size of a hardcover dictionary. All that had been inscribed on any of them were names and the two most important years in anyone's existence. ``Mother, 1845-1912.'' ``Father, 1840-1905.'' ``Henry, 1884-1944,'' and so forth. On the extreme left-hand perimeter of the Andersen territory, almost into the Birds', was the stone he was looking for.

``Baby Bryce,'' it read, ``1996-1996.''

He opened the green bag and laid what was in it, a single white rose, atop the stone. His fingers were clumsy, his breath more labored than it should have been. He didn't have any of the thoughts he had expected would be haunting him right now; maybe they would come on the return trip to Chicago, or the plane home tomorrow to Boston. Nothing about what might have been, how he might have been playing Little League baseball, what he might have looked like, what his favorite subject in school might have been. None of that. Only a nagging sensation of having done wrong, and never being able to make contrition, even if he wanted to.

He didn't hear the pickup. Didn't see her approach from the field.

When he looked up, she was there, barely 20 feet away.

He looked at her, startled initially. Time had gotten to her. It had to him, too, he couldn't kid himself. She looked unkempt, haggard, as if she never got enough sleep any more. Her clothes looked freshly laundered but worn, as if she'd had them too long. For an instant, their eyes locked. It was impossible to say what was exchanged between them in that moment. Recognition, but more. Loneliness. A glimmer of what might have been, perhaps. A rush of memories, none well defined. Then it was gone. Her eyes went as cold as the gathering evening. There was nothing to say.

She came closer. He didn't move. He hadn't expected it to play out like this.

They embraced. For his part, it was instinctive. Reflexive. There was no more thought to it than drawing a breath. She was warm, her breath intoxicating. Through her coat, he could feel the swell of her breasts. Suddenly, the memories had taken on sharp definition. Now he remembered them making love the first time, the way he'd eased inside her, the softly building passion that had finally exploded one Saturday evening when his roommate was away.

He didn't see her knife.

She plunged it into the back of his neck.

The first blood fell in perfect splatters on Baby Bryce's stone, like drops of wax from a flaming red candle. It was only a surface wound, calculated and deliberate. Alone, it might have stopped bleeding. He wasn't even sure at first that he'd been stabbed. He thought maybe she'd dug her fingernails into him. The tenderness he'd started to feel escaped him like steam. He was tempted to slap her. He'd never wanted to hit a woman before. He did now. Self-defense. But he didn't. He turned, headed for the car. A trickle of warmth ran down the inside of his shirt. The crazy fucker.She roared toward him, her cutting arm a scythe of blurred motion. This time he saw the blade. It was a pocket knife, the kind young punks smuggle into school. The blade couldn't have been four inches long. In that instant of confused terror, he remembered something his mother had told him as a kid. It wasn't about knives. It was about drowning. You can drown anywhere there's water, she'd said. Even in your own bathtub, even in an inch of water.

This time, she connected only once, a long, violent gash that sliced through his coat sleeve into his forearm. The fabric was quickly moist from the inside out. The pain was immense. She meant to kill him. It was like being kicked in the stomach, realizing that, but he knew it was true. He was suddenly breathless, fevered. With his good arm, he grabbed his wounded one, holding it fiercely, as if that would stop the bleeding. She came at him again. For a second, he saw her eyes. There was nothing there but emptiness. He ducked to one side, and she charged past him, almost falling.

He hesitated. For a second, he thought of fighting back. He was bigger than she, stronger. And she was out of her mind, a crazed psychotic with a knife. He looked wildly around, but there was nothing he could use as a weapon, no branch or loose rock. The best bet was to get the hell away. The bleeding wasn't bad, but he'd have to see a doctor. Then he would go to the police and have the crazy fucker arrested. That's what he was going to do, goddamn it. Have her put behind bars for good.He took a step, a step that brought his foot into contact with Baby Bryce's stone.

He felt something lock around his ankle. Tiny, vice-like.

He looked down. There was nothing there, of course, only grass and that flat polished marble stone, blending into the shadows of approaching evening. He could taste bile as his panic rose.

He tried to move.

He was locked in place.

``What the--''

She was back, blade whistling. Her aim was more precise than before. He saw the knife, heard it, tried to roll out of its trajectory, but his foot was stuck. He did the best he could, twisting and squirming to one side. It was not enough.

She made contact, again and again. His shoulder. His side. His thigh. His right hand. He felt each cut. None was deeper than tendon level. It was more like being pricked with a needle or stung by hornets than being stabbed. After each cut, the warm moisture. Death by a thousand cuts.

His ankle.

He grabbed at it, like a mink caught in a leg hold trap. There was nothing there, of course. With his other hand, he tried frantically to fend her off. She was nimble. She seemed able to anticipate him, dodging when he lashed out, closing back in when he tried unsuccessfully to get to his feet.Maybe he could crawl. In his panic, that new thought was delightful. It was like being born again. He was on his belly and maybe he could crawl. Maybe he'd broken his ankle, that was all, and he could slither away from her.

But he couldn't crawl, not more than a few inches. His foot was frozen.

She was in no hurry. There was still plenty of daylight remaining, 15 minutes or more until blackness settled over them. She was nicking him. Little flicks of cuts, counting toward a thousand. It was uncanny how she kept missing all the major arteries and organs, the ones that would have ended it quickly. She seemed to know anatomy, seemed to have studied it until she was sure what to hit, what to avoid. He was bleeding everywhere but gushing nowhere. His central nervous system only gradually was shifting into shock.

The pain was building. Soon it was too big for screaming. He began to moan. A mortally wounded animal sound, back through the millennia to when ancestors walked on all fours. Hunter and prey.

Victor and vanquished.

His vision blurred.

As consciousness drained away to nothingness, he thought he saw her.

Smiling, her face inches from his.

He thought he heard a new sound.

The sound of a newborn crying.

The sound of birth.

(Should you wish to purchase any of my collections and books, fiction or non-fiction, visit www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm)

LANDING PAGE for all the Free Reads during #coronavirus

May 23, 2020

The time I interviewed Stephen King

READ AFTER THIS INTRO: One of my favorite interviews ever! Of my still-favorite author.

Look between the lines (this one, for example: Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth...) and you will see evidence of King's then-cocaine addiction, unknown to the world at the time but later very public when King himself wrote and spoke about his struggle. He's been clean and sober for decades now.

BUT then -- during this interview -- he was deep into it. Every few minutes during my hour-or-so-with him he jumped up, disappeared into a back room of his hotel suite, and returned, even more animated and hyper than before. Little did I know. I just thought he was, well, full of energy.

Another note: King was in a suite on an upper floor of a hotel overlooking New York City's Central Park (I forget which one, maybe The Pierre?). I waited in the lobby for a publicist to take me up and when the elevator opened, who stepped off but the now-disgraced Today Show ex-host Matt Lauer, who had just interviewed King for Fox affiliate WNYW, the NYC station he'd joined after leaving PM Magazine, Channel 10, Providence. We said hello; I knew him peripherally. No clue, of course, what awaited him...

And one more note, if I may?

King's editor then was the late Alan Williams, one of publishing's greats. He happened to be the editor who bought and published my first book, Thunder Rise. How glorious that was, and how long ago. I can recall like yesterday sitting in his mid-town Manhattan office discussing the book, which my first agent, the wonderful Kay McCauley, sister of then-King agent Kirby McCauley, had sold.

OK now:

The Providence Journal

KING OF HORROR: His career's in 'Overdrive' as he directs his first film

Publication date: 8/3/1986 Page: I-01 Section: ARTS

Byline: G. WAYNE MILLER

STEPHEN KING, the most popular horror writer of all time, is eating pizza - thick, oily, mega-calorie pizza with all the fixings. He's eating it the way a big hungry kid would - ferociously and noisily. Stephen King loves pizza, just as he loves scaring the pants off people.

King, who has made enough money from what he calls his "marketable obsession" to buy Brooks Brothers' entire inventory, is dressed in jeans, work shirt, running shoes. Comfort is the thing for King, who sets many of his stories in rural Maine, the place he's lived most of his 38 years.

Would his visitor like a slice of that greasy monster masquerading as a pizza, he asks politely? No? Then have a seat. Feel at home.

He sits - flops is probably a better word - onto an oversized chair in his hotel suite. King is well over six feet tall, and his long legs seem to stretch halfway across this elegantly furnished sitting room. He brushes his black hair off his face, grins mischievously, and peers from behind thick glasses, his "Coke bottles," as he's referred to them.

"Whatever you want to talk about," he says in a voice that is a curious mix of Downeast twang and Ted Kennedy drone. "The film is what I'm supposed to talk about, so why don't we start with the film?"

Maximum Overdrive, King's first shot at directing, opened last weekend. It's about a group of people trapped by driverless vehicles in an isolated truck stop the week all the machines in the world go murderously beserk. Machines gone mad. It's a favorite King theme, and if one were to psychoanalyze it, the connection to modern man's uneasy coexistence with his nuclear genie would be hard to miss.

The obvious first question, of course, is why a one-time teacher who has parlayed a lifelong fascination with the macabre into a fairy-tale existence as best-selling author (70 million books in print) would want to trade his golden pen for a camera.

Certainly, King is no stranger to movies. He admits to being a horror-movie junkie growing up in the '50s and '60s; as an adult, he has written the screenplays for five films, including Overdrive. Eight of his full-length novels have been made into films of varying quality, and another four (including Pet Sematary, his most recent) are in various stages of production. On top of all that, several King short stories have been adapted for TV, and an unpublished novel has been sold for a mini-series.

So why direct?

"Curiosity," he says, continuing to gorge himself on pizza.

Actually, it wasn't simply curiosity that prompted King to accept movie mogul Dino De Laurentis's offer to direct.

Pleased with some

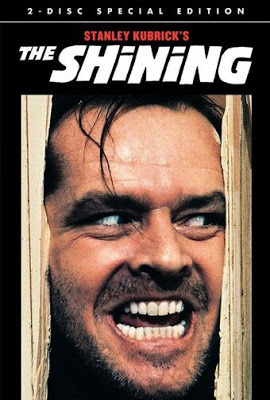

Although King is pleased with some film adaptations of his works - he thinks Cujo and The Dead Zone are great - he has been disappointed with others. In particular, Firestarter, Children of the Corn, and The Shining, directed by Stanley Kubrick, still make King cringe. (He once described Firestarter as "flavorless," like "cafeteria mashed potatoes.")

The disappointing films, King explains between bites, failed to capture the spirit of his written works - either they didn't frighten, or took implausible twists, or were blandly acted, or sloppily directed, whatever. With Overdrive, King finally wanted to see if he could capture that spirit on film. If he couldn't, well, at least he'd have no one but himself to blame.

"My son's got this wonderful imitation of Leonard Malton on Entertainment Tonight," King says, becoming suddenly animated.

"He'll start off the way he always starts off when he's going to give a really bad review. He'll say, 'This is Leonard Malton, Entertainment Tonight. Stephen King says that he wanted to direct a picture to see if whatever makes his books so successful could be translated to film if he did it himself.

" 'The answer is no]' "

King grins. "Actually," he continues, "the answer is yes. I think. I think it has a lot of appeal of the books."

Not that he's exactly rehearsing his Academy Award acceptance speech, as he notes wryly. Although the film does not look amateurish - for a rookie, King's grasp of cinematic technique is quite impressive - its human characters are undeveloped. And despite King's hopes, Overdrive only hints at his books' rich textures. It's hard to escape the conclusion that what King does so well in print probably can't be translated onto the silver screen.

"I think by and large this movie will get kind of a sour critical reception," he predicts. "It's a 'moron movie,' for one thing. It's crash and bash. It's a head-banger movie - really, really loud."

Promotional tour

Critics notwithstanding, King believes audiences will like Overdrive as much as he does. He hopes so, anyway. The only reason he agreed to do a nationwide promotional tour is to hype the film. Too many earlier King films, he laments, have lasted in theaters all of two weeks.

"Graham Greene said . . . writers write books they can't find on library shelves. To some extent, I think directors must direct movies that they can't go and watch in movie theaters.

"Overdrive is fun. I like movies where you can just, like, check your brains at the box office and pick 'em up two hours later. Sit and kind of let it flow over you and, you know, dig on it. This movie is just sort of gaudy blaaaaah. It's not a heavy social statement," he asserts.

Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth - he's got one hell of a set of incisors, one discovers. Normally a rational and intelligent human being, he's transformed himself into a raving lunatic.

He jumps up and screams: "One of the things I wanted was to never let up. My idea is that what you do is build up, like reaching out and grabbing somebody by the ----] Right out of the page if possible or right out of the screen] Tell you what, ------------, you're mine]]]]]]"

He sits down again, laughing like - like a kid.

Four new novels

To say that Stephen King is big is a little like saying Carrie, telekinetic murderess of his first novel, is odd.

Some noteworthy footnotes to the King saga:

* The initial hardcover printing of last year's Skeleton Crew, his second anthology, was one million copies, one of the largest first hardcover printings in publishing history.

* King books are hot collectors items. In May, for example, an uncorrected proof of his Night Shift collection brought $2,500 at a San Francisco auction. A small-press magazine in which one of his stories appeared years ago brought a cool $150.

* For a decade, King's books have consistently topped the best-seller lists. According to Publishers Weekly, his scorecard for 1985 included the fifth and 11th best-selling fiction hardcover books; the second, fourth and eight best-selling mass paperbacks; and the second and third best-selling trade paperbacks. Total sales of those seven books alone: 11.49 million.

* King has his own monthly newspaper, Castle Rock, published and edited by his secretary, Stephanie Leonard.

* Against the advice of his publisher, who's worried that the market will be saturated (King disagrees), King will release four new novels in the next year, including the 1,000-page-plus IT later this summer.

* A musical version of Carrie takes to Broadway this fall.

Not to mention all those movies.

This being America, money has come hand-in-hand with his fame. King is so rich that when someone threatened to buy his favorite radio station in Bangor, Maine, and replace its rock format with EZ Listening, he rushed out and bought it himself. Rumor has it he paid cash.

The unknowns remain

Naturally, there are secrets to King's success.

One - hardly the best-kept - is that people, millions of them, anyway, like to be scared. Late at night, with the wind moaning, the leaves on the trees rustling, the kids sleeping (are they still breathing?) and something downstairs making a strange noise (is it only the cat?), they love to curl up with a good scary book and let the chills crawl down their spines.

King has lectured and written extensively about fear. He understands that no matter how technologically advanced we become, no matter how much the scientists figure out about ourselves and our world, the great unknowns remain: darkness, death, whatever is beyond the grave.

Still, there are plenty of horror writers slogging away out there, including several who have won critical acclaim - such as Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho, and Peter Straub, author of the million-seller Ghost Story, and J.N. Williamson and Richard Matheson, two of the more prolific writers of the genre. Some are literary, closer to Poe than King; others are more gruesome, more skilled with plot. In terms of popularity, King has eclipsed them all.

The real secret is where King has taken horror - out of the Egyptian mummy's tomb and straight into the living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens of contemporary middle- and lower-class America. King's landscape is the America of kids and pets and Coke and malls and cheeseburgers and troubles with the mortgage payment and that old clunker, the family car - much the same vision of America that Steven Speilberg has brought to Hollywood.

Not that everything is ordinary in King's works. Whether haunted car or haunted child, King's villains and monsters and spirits are deeply troubling, frequently uncontrollable, and usually deadly. There's a lot of darkness in King's work, and plenty of ghosts. Death is never very far away.

It is precisely this juxtaposition - ordinary people victimized by extraordinary forces - that is the key to all good horror, not just King's.

Hitting the nerves

Still . . . 70 million books, 16 movies, a Broadway play, and no end in sight?

"Some of it," King explains as he polishes off lunch, "has got to be that I'm talking about things that, like you say, hit nerves. Or maybe they don't hit nerves - maybe they just resonate.

"You know, people say, 'I know about that, because that happened to me.' I don't mean an ability to light fires or anything like that (the heroine of Firestarter is a young girl with pyrotechnic powers), but something about family life, or something your kid said, something like that."

Not that King's intent is anthropological exposition; he is not a scholar, nor does he pretend to be. He bases his fiction on situations he understands because they've been his life, too - family, marriage, the battle (at least in the early days) for a buck. King and his wife, Tabitha, also an author, have three children. The eldest is 16.

"I don't write with an audience in mind. I mean, the audience is me. My popularity says something about my own mind. It's a little bit distressing when you think about it. It says, 'Well, here's a person who's so perfectly in tune with middle-cultural drone that there must be this incredible bowling alley echo inside his head.' "

Even King's detractors - there's no shortage of critics who dismiss his work as insignificant - concede that he has a true talent for depicting children. Maybe that's because King himself could well be the biggest kid in America. Even when they are blessed/cursed with supernatural powers, King's fictional children are flesh and blood - so seemingly real that you wonder if they don't actually exist somewhere, and King is only documenting their lives.

In fact, King's own children have had enormous impact, and if you doubt that, you only need look at his dedications.

"I grew up with them," he says. "Bringing up baby or child or children or whatever has been one of the experiences of my life, and so it's one of the things I write about. But also it's a way of trying to make sense of how the child you were yourself became the man that you are and that whole crazy business."

Woes with women

As good as King has been creating children, he has had his woes with women, as countless critics have been quick to point out.

"I've had such problems with women characters," he agrees, the smile leaving his face. "God knows I have tried. I tried with Donna Trenton in Cujo - tried to make a real woman. (I thought) she worked pretty well, except I got hit pretty hard by a lot of critics. An awful lot of critics said the dog is punishment for adultery.

"The death of her child . . . consciously, on top of my mind, I was simply trying to create a convincing chain of events that would put the boy and her in that position where they could spend a period of time. But when you think about it. . . .

"Yes, I've had trouble with women. It's funny because that's why I started to write Carrie. This friend of mine said to me, 'The trouble with you is you don't understand women.' I said, 'What do you mean?' It's like he'd accused me of being a virgin or something like that, which I just barely wasn't at that time.

"He says, 'Ah, all these stories with these hairy-chested horror things, these guys fighting monsters and stuff like that.' I was trying to tell him, 'You don't understand. That's what they buy, these men's magazines.' He said, 'You couldn't create a woman character if you tried. You know, a good one.' I said I bet I could. Carrie - that's a book about women, almost completely about women. There are almost no male characters in it."

Father ran off

By now, the story of King's climb to the top is legendary.

It begins with a kid growing up in Maine and (for four years) in Connecticut - a kid whose father ran off never to be heard from again, a kid whose mother raised him and his elder brother on a shoestring. On the outside, King was a polite child who liked cars, played some sports - but inside, he would later recall, he often felt unhappy, "different," even violent.

He remembers writing his first horror story at the age of seven; it was about dinosaurs on a rampage. Through his teens, he read voraciously, spent hours in movie theaters, kept on writing and writing and writing. It was while attending the University of Maine, Orono, that he began to sell short stories to magazines. But his novels, and there were several of them by this point, were going nowhere.

After college, he and his wife worked a succession of jobs to keep their family afloat: Tabitha as a waitress, he as a worker in a coin laundry and as an English teacher at a private school. The short stories kept selling - they were helping to pay the rent on the tiny trailer where they lived - but the novels were still moribund.

King wrote Carrie working late into the night in the furnace room of their trailer - the only available space in already cramped quarters. Somewhere, King says, they still have the Olivetti portable typewriter on which he banged out several early novels and stories.

The old portable

"There were no word processors then," King remembers. "I used my wife's portable. She stills says sometimes - in jest, I think - 'My husband married me for my portable typewriter.' It's got my fingerprints carved into the keys. I mean, I beat that thing to death just about.

"I used to have to bring Joe in in his crib to where I worked, which was the furnace room. You'd get hot and you'd be going along good and he'd wake up and you'd have to give him a bottle because he'd cried. It was just, you know, you get it done the best you can.

"You don't raise your head and look around, because if you do you just get depressed. And I was depressed then. Because I was selling some short stories, but I had had like three, four novels bounced back at me at that time and also a number of other short stories."

Even after finally selling Carrie to Doubleday, the struggle continued.

"My wife used to work at 'Drunken' Donuts,' which is what they called it on the night shift. I used to take care of the kids while I did the rewrite. This was after the contract and everything, but before we had any money. I mean, the contract was only for $2,500. It wasn't exactly a king's ransom," he says, seemingly unaware of the pun.