G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 6

September 24, 2022

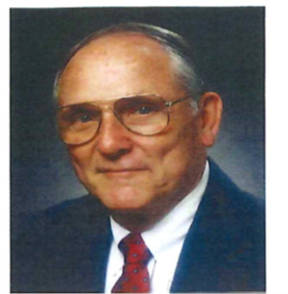

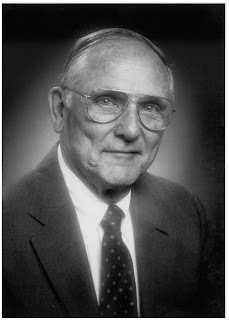

Remarks at the Sept. 24, 2022, Memorial Celebration of William Hardy Hendren III, M.D., held at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Thanks, Will, and thanks Jay, Pat, Jim, Kathy, Terry and Craig. And a big hello to Eleanor, Doug and Nancy, Linda, Rob, David and Astrid, and Charlotte and James, two of the grandchildren of Hardy and Eleanor who are here.

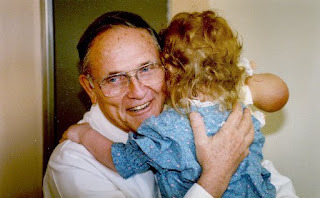

From the moment I first met Hardy more than three decades ago, on a visit to the Hendren home in Duxbury, I knew I was in the presence of an extraordinary human being. Whether by means of magic, divine intervention or just luck, a relationship was born that would prove professionally rewarding to me.

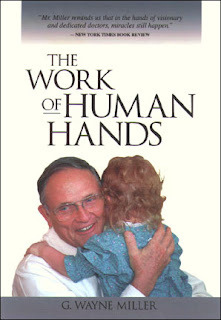

My 1993 biography of Hardy, “The Work of Human Hands,”launched my non-fiction book career – a career that also brought me, thanks to Hardy, to Walt Lillehei, father of Craig and the man who pioneered open-heart surgery, as recounted in my book “King of Hearts.”

But as great as the professional rewards have been, the personal rewards have been an even bigger blessing – one that everyone who has known the Hendrens has also shared. Eleanor and Hardy became dear friends, opening their lives to me and my family, including my son, Calvin, who is Hardy’s godson. We shared many laughs and stories and, as time went on, lots of memories.

So let me get a bit deeper into the personal.

And by personal, I mean the person who was William Hardy Hendren III.

In medical circles, this person earned the nickname of “Hardly Human” for what might correctly be called the superpowers he took with him into the operating room.

Here was a surgeon who could fix the unfixable and cure the incurable, sometimes during marathon operations that lasted 24 hours or more. Hardy saved and bettered untold thousands of lives during one of the most amazing runs in the history of the healing sciences. We will hear from [the father of] one of his patients, Keith Fox, in a moment.

But while “Hardly Human” works well enough as a description of the surgeon, there is a better one, I think, to describe the person.

And that is “Wholly Human” -- as in “thoroughly,” “completely,” or, as my trusty Roget’s Thesaurus declares, “in full measure.”

Allow me to give you a sense of that full measure.

I’ll start with Saltines. As Jim O’Neill just told us, hardy loved Saltines.

One Sunday long ago, I was visiting Hardy in Duxbury. Eleanor was away, but she had left freshly made soup, which Hardy and I were eager to eat for lunch. Hardy ladled a bowl for each of us, then announced he wanted Saltines to accompany the soup.

For some reason he did not explain, he wanted them warm.

So he put a bunch of them, still encased in cellophane, into the microwave and pressed on.

Full-power on.

I watched as the crackers circled inside the machine, horrified but not saying anything. This person was a master of technology, at least of the medical kind, so maybe he knew something I didn't.

He did not.

Soon enough, the cellophane ignited and we had a blazing fire. Smoke billowed and alarms sounded.

Hardy looked momentarily puzzled, but then, always cool under pressure, he removed the crackers with an oven mitt and walked them to the sink, where he extinguished the flames.

We sat down then to eat Eleanor's soup. The Saltines this time were room-temperature.

Hardy, of course, taught generations of doctors. I had no desire to become one, except, perhaps, vicariously, so there was nothing he would have taught me there.

But he did teach or re-teach me many things – among them, the importance of truth and generosity and the need to sometimes laugh at one’s self. Every time I retold the Saltines story, Hardy always roared.

Another lesson I learned from Hardy was how to cut a sandwich with scissors.

This lesson occurred during another long day at Children's when, between operations, we went down to the cafeteria to get something to eat. We both ordered sandwiches – I forget what kind – and brought them back to the surgeon’s lounge.

Which was no dining room. No knives, forks or spoons that I could see.

The sandwiches were large and I was mentally wrestling with the mess I would make tearing mine apart when Hardy came to the rescue. He happened to be carrying a pair of his gold-plated surgical scissors – the ones that Dorothy Enos so carefully kept – and with them, he cut my sandwich, then his, and began to eat.

I was amazed – so amazed that I didn’t ask if the scissors were clean, but trusting Hardy – you could always trust Hardy – I knew they were.

At home, I have since cut sandwiches with kitchen shears, and also string cheese and haddock filets -- sometimes to the amusement of observers but usually with a look that says, “Have you lost your blanking mind?”

To which I say: "I learned from the best."

As in, the best person.

I mentioned Hardy and Eleanor's generosity, and I could cite many examples of their largesse, but lacking the time, here is one: They offered their house to me for a week when they were away so that I could complete the final draft of "King of Hearts" in writerly solitude. It was an incredible week, and not just creatively, for I had the honor of sleeping in a guestroom that had been their late daughter's bedroom.

Let me close with one last story of Hardy, this wholly human person. While researching and writing "The Work of Human Hands," I spent many days in Duxbury going through Hardy's records and documents and photos. On one of those days -- it was a fine early autumn day not unlike today -- he asked if I wanted a ride on the back of his motorcycle.

I did.

We headed out from King Caesar Road, destination undeclared. After a while, Hardy turned off the main road into a church parking lot. We got off his bike and he led me to the cemetery in back.

And there was the grave of Sandy, his and Eleanor's first child, who became a nurse and worked with Hardy at The General when he was chief of pediatric surgery here.

We stood in silence and I was saddened thinking about the tragedy that Hardy and Eleanor and their other children had experienced.

The only other time I have been to that cemetery was this past March, when, after Hardy's funeral, his ashes were placed in the ground next to Sandy, who died of complications of diabetes in 1984 at the age of 37, here in Mass. General Hospital.

During that March service, I was privileged to throw sand from Eleanor and Hardy's favorite beach onto Hardy. And I, like others, was invited to say a few words.

On the verge of tears, I recalled what Hardy said one time when I asked how he never tired during those crazy long days in his OR, where he was working his wonders.

He said: "Don't forget, there's a great big rest at the end."

Rest in peace, Hardy. The world will never see another person like you.

W. Hardy Hendren III, M.D. Memorial Celebration

MGH O’Keefe Auditorium September 24, 11 AM – 1 PM

Program Photo History of the Life of W. Hardy Hendren, III

Welcome Keith Lillemoe, MD

American College of Surgeons Icons in Surgery Video

Remarks/Recollections Jay Vacanti, MD

(In the video)

Medical Patricia Donahoe MD

James O’Neill, MD

Kathryn Anderson, MD

Terry Hensle, MD

Craig Lillehei, MD

Author G. Wayne Miller

Patient Keith Fox

Family William G. Hendren, MD

Minister Father Daniel Dice

“Thanks for the Memories”

Closing remarks Allan Goldstein, MD

Retire to Russell Museum for reception 1 – 2 pm

September 15, 2022

The (future) King and I

In late-summer 1986, the young Prince Charles visited Harvard to speak at the school's 350th anniversary celebration. I was among the journalists who covered the visit -- and attended a private party with the now King Charles III at the Ritz-Carlton in Boston. Herewith my reports:

Faculty member Emily D. T. Vermeule with Prince Charles,

Faculty member Emily D. T. Vermeule with Prince Charles,350th celebration of Harvard's founding.

From the September 3, 1986, Providence Journal:

The Prince Meets the Duke

By G. Wayne Miller

The jet was waved to a stop, the engines were killed and the rear door opened. The British ambassador bounded on board. In a minute, he reappeared. There was a pause. Gathered on the Logan Airport tarmac, a dozen VIPs waited. Behind them, the mock colonial militia stood at attention. On the roof of a nearby hangar, a police sharpshooter scanned the proceedings. A motorcade of Jaguars and a gray Rolls was ready, engines idling.

Prince Charles stepped into the early evening and a small knot of invited well-wishers cheered.

He didn’t say much - not that the crowd could have heard it over the roar of jets taking off. But he did shake hands. He shook Governor, (sometimes known as the Duke) Dukakis’s hand. He shook Mayor Raymond Flynn’s hand. He shook Ambassador Antony Acland’s hand. He shook the hand of Francis Burr, the chief marshal of Harvard University, which is celebrating its 350th anniversary this week, and which invited the prince to speak tomorrow at a convocation.

When introductions were over, the militias, fifers and drummers began to play the national anthem. Accompanied by Dukakis, the prince passed in review. He was impeccably attired in blue shirt and dark suit. His face, which many say is handsome, showed no emotion. He seemed humorless. On how many occasions has the prince, who has been around the world countless times, had to review the local colors?

It was different when he got to the crowd of Union Jack-waving spectators, many of them British. Charles broke into a big smile, and he waded fearlessly into the mob, enthusiastically grasping every hand he could reach.

“It was so marvelous,” Helena Nultey, a British employee of the British Consulate, would later say. Nultey was one of the lucky ones: She got a piece of the prince. Sixty-two years old, and it was her first meeting.

“Such a handsome man. So charming. So much better looking than in photos. This is one of the most exciting moments of my life.”

Another few minutes, and Charles was gone - whisked away by motorcade to the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, where he is spending two nights on his first visit to Boston. He will be alone, as his family stayed behind at Balmoral, a royal castle.

If yesterday’s welcome was fleeting, it nonetheless was a reminder of what royalty in the age of congresses and parliaments and dictatorships still can be. Ceremony, in a word. Carefully coordinated ceremony that goes off like clockwork. Even the prince’s jet was on schedule.

Like him or not, Charles is the real thing, not some nouveau-riche opportunist who made his money in shopping malls and then managed to buy a title on Europe’s phony pedigree market.

Centuries-old monarchy

The prince, 37, the heir to his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, is part of a monarchy that traces its roots to William the Conqueror. As such, he is related to just about any English king you might name off the top of your head - all those Henrys, Edwards, Georges, Richards, many of whom wound up in Shakespeare. Queen Victoria was his great-great-great grandmother.

He doesn’t have a last name, but Charles Philip Arthur George, as he was christened, has more titles than you could ever hope to buy: Duke of Cornwall, Earl of Chester, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick and Baron Renfrew, Lord of the Isles, Chairman of the Royal Jubilee Trusts, to name a few.

Naturally, he’ entitled to respect - even here in America, which got rid of one of his ancestors a couple of hundred years ago. Earlier, by phone and during a press conference, the consulate staff gave reporters tips for being with the prince. On introduction, for instance, he is addressed as His Royal Highness - HRH, as the consulate refers to him in its news releases. Subsequently, he may be called “Sir.” And one never independently extends one’s hand to HRH; one waits until he offers his, and if for some reason he doesn’t, tough luck. In America, a bow is optional.

No contact with public

Not that many people yesterday had a chance to practice their protocol. Except for a small reception last night at the Ritz, to which reporters were invited only on condition that they not report any conversation with Charles, the prince had virtually no contact with the public.

Also from the September 3, 1986, Providence Journal:

No secrets here: HRH is a man who knows how to meet the press

By G. Wayne Miller

“As you are probably already aware,” the note from the British Consulate began, “His Royal Highness has asked for an opportunity to meet some of the working correspondents who will be covering the visit.

“The reception will be a purely social and informal event, by personal invitation only. It will be wholly off the record. No cameras, microphones or notebooks will be allowed. No reference should be made subsequently to specifics of any conversation with His Royal Highness.”

Fine. We agreed to the ground rules of last night’s reception at the Ritz-Carlton - who could pass up the chance to meet Prince Charles? And HRH, as he is sometimes known, will be be pleased to learn that we’re not about to divulge any of his deepest, darkest secrets.

Actually, no secrets were confided - but without breaking our word, we feel we can report that:

* There were about 50 guests, and except for a handful of Scotland Yard’s finest, almost all were reporters. Surprisingly, there were almost no names - excluding HRH, of course.

* The caviar, sliced fresh salmon and foie gras were delectable. They were served by waiters who wore white gloves.

* HRH drank a single martini, with a single olive.

* He wore a dark two-piece suit and a blue shirt. It was not an Oxford collar, but it was cotton. This is one dapper dresser. No surprise there. As others have remarked, he does indeed seem more handsome in person than in pictures.

* Charles smiles easily, talks pleasantly and went out of his way to mingle with the crowd. His questions showed a knowledge of America and an enthusiasm for his position as prince. And why not?

From the September 5, 1986, Providence Journal:

Harvard’s 350th: A Royal Occasion

By G. Wayne Miller

Harvard, an institution for far longer than America has been a republic, congratulated itself yesterday on its 350th birthday with a convocation flavored by all the colorful pageantry the nation’s oldest and wealthiest university could muster.

As it does for graduations, the university transformed that most revered of academic places, Harvard Yard, into a flag-filled amphitheater. During the two hours that it overflowed with an estimated 15,000 people - many dressed in top hat and tails or cap and gown - a bell pealed, a band played, anthems were sung, prayers were offered and speeches were delivered.

Yesterday’s ceremony was but part of a week’s celebration that will cost about $1 million. It was a spectacle worthy of royalty - and royalty there was, in the person of Britain’s future king, Prince Charles, who delivered a main address that began with humor and ended with a standing ovation.

Like others who spoke before him - Yale president Benno C. Schmidt Jr. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology head Paul E. Gray among them - Charles paid tribute to Harvard, whose graduates and professors over the years have had a tremendous influence on politics, science, medicine, business and the arts.

“After all,” the prince observed, “[Harvard] has produced a cornucopia of leaders for the United States in many fields, not to mention the fact that six Harvard men have become president.”

After making a joke or two about Yale, Harvard’s perennial rival, the prince became serious. And he turned away from Harvard for a moment to issue America and all of its schools a challenge - the challenge of educating young men and women as moral beings with a sense of spirituality and decency.

“While we have been right to demand the kind of technical education relevant to the needs of the 20th Century, it would appear that we have forgotten that when all is said and done, a good man - as the Greeks would say - is a nobler work than a good technologist.

“We should never lose sight of the fact that to avert disaster, we have not only to teach men to make things, but also to produce people who have control over the things they make.”

After a round of applause, he continued:

“Never has it been more important to recognize the imbalance that has seeped into our lives and deprived us of a sense of meaning because the emphasis has been too one-sided and has concentrated on the development of the intellect to the detriment of the spirit.

“Surely it is important that in the headlong rush of mankind to conquer space, to compete with nature, to harness the fragile environment, we do not let our children slip away into a world dominated entirely by sophisticated technology - but rather teach them that to live on this world is no easy matter without standards to live by.”

March 8, 2022

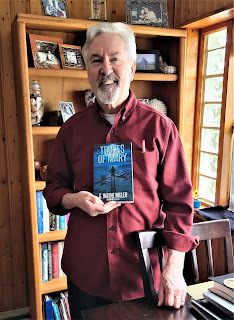

Publication day for Traces of Mary!

My first book, "Thunder Rise," from William Morrow, was published in 1989, and what a thrill it was for a young writer to hold a copy in his hands.

My first book, "Thunder Rise," from William Morrow, was published in 1989, and what a thrill it was for a young writer to hold a copy in his hands. Thirty-three years later, the thrill remains with publication today of my 20th: "Traces of Mary," from Crossroad Press, which USA Today bestselling author Jon Land called "a bold, bracing, blisteringly original hybrid tale that reads like Stephen King on steroids."

Part horror, part science fiction, part mystery and thriller, and part exploration of mental illness, "Traces of Mary" is unlike anything I have ever written.

I hope this novel meets your expectations!

And the same for the two short stories with extraterrestrial themes that are included in the volume: “A Couple from Manhattan,” which unfolds in a Lovecraftian setting, and “This Little Bug,” about an impending pandemic that will make COVID seem like child’s play.

Read the reviews, order the book.

p.s.And stay tuned for my 21st book, coming in 2023!

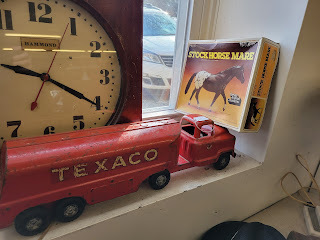

March 5, 2022

Antiquing

Tricycles

Tricycles Juke Boxes

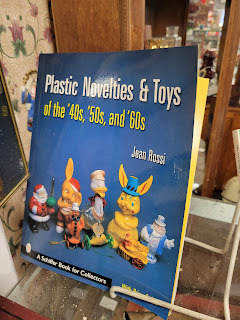

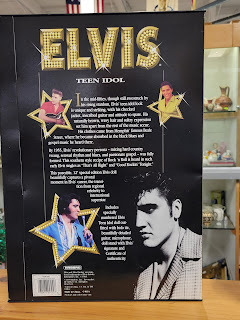

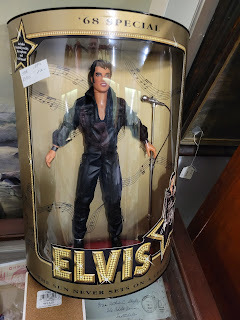

Juke Boxes Branded toys.

Branded toys. Skateboards

Skateboards Video games.

Video games. Wicked old toys.

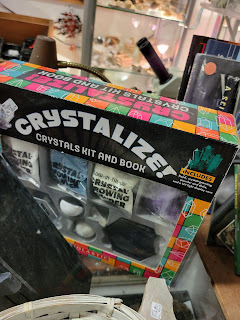

Wicked old toys. Science kits.

Science kits. Microscopes.

Microscopes. Weird s***

Weird s*** Golden Books!!!

Golden Books!!! Sno-cones.

Sno-cones. Stuffed animals/plushies.

Stuffed animals/plushies. Let's not forget lunch boxes.

Let's not forget lunch boxes. A line I never heard of.

A line I never heard of. Another line unknown too me. Hence, further research.

Another line unknown too me. Hence, further research. Models.

Models. Need I say more?

Need I say more? Sleds, liddle cars.

Sleds, liddle cars. Yup.

Yup. Bigger yup.

Bigger yup. My, my.

My, my. My, my, my.

My, my, my. Dentist Barbie!!! At Benny's.

Dentist Barbie!!! At Benny's. Off to war we go, Joe.

Off to war we go, Joe. Toy trucks.

Toy trucks. More toy trucks.

More toy trucks.March 1, 2022

Remembering Hardy Hendren: February 7, 1926, to March 1, 2022.

Early one Saturday morning in the early spring of 1990, my phone rang. I was in my basement shop, building something.

“This is Dr. Hendren,” the voice on the other end said. “I understand you’ve been trying to reach me.”

I had been. Recently, I’d been discussing writing a book about Boston Children’s Hospital with a young editor at Random House, Jon Karp, and we had agreed that Dr. W. Hardy Hendren III, the Chief of Surgery at Children’s and a giant in his field, might be a good guide into that world.

But after repeated calls to his office, I had despaired of him ever contacting me, if he had even seen the many messages I’d left with his staff.

Caught off-guard that Saturday morning, I mumbled something about being a staff writer at The Providence Journal and the author of exactly one published book, “Thunder Rise.”

A horror book, that.

I like to think it was instinct but more likely, it was appreciation of my persistence that prompted Hardy to invite me to his house in Duxbury, Mass., to discuss what I had in mind.

A short while later, I visited. Hardy’s wife, Eleanor, and youngest son, David, welcomed me inside and told me the surgeon was out on the bay but would be back soon. When he got home, we retired to his first-floor study, where we talked and he showed me bound copies of his operative notes dating back decades.

I left Duxbury with Hardy’s promise to open the doors to Children’s to me.

Thus began the extraordinary journey that led to my 1993 book “The Work of Human Hands: Hardy Hendren and Surgical Wonder at Children’sHospital” and a six-part series in The Journal, “Working Wonders.”

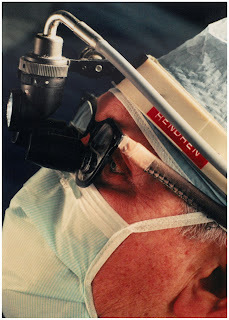

Neither, of course, could have been written without Hardy. Working with the Children’s Public Affairs staff in this pre-HIPAA era to protect patient privacy and with the permission of consenting parents, I began joining Hardy and scrub nurse Dorothy Enos in the OR. And not just Hardy’s – encouraged by him, I watched many kinds of surgery by many Children’s surgeons over the better part of two years that I was in residence.

What a remarkable adventure it was. I wore a Children’s-issued ID, kept a locker in the surgeons’ locker rooms, and soon enough got to know not only surgeons and other doctors – many of them, like Judah Folkman, giants in their own right – but also nurses, technicians and others. Many days were long – some of Hardy’s operations ran longer than 24 hours – and many was the time that I drove back to Rhode Island with dawn breaking and a new day begun.

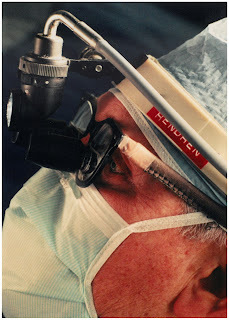

Man at work.

Man at work.

Hardy's OR, 1990: Hardy back to camera;

Hardy's OR, 1990: Hardy back to camera;Dorothy Enos to his left; me, second from right.

“The Work of Human Hands” launched my career as a non-fiction author, and I will always be indebted to Hardy for that. It also was the first book Jon Karp (who I’d met during the few months he was a staff writer at The Journal right out of brown University) bought and its success helped launch his career in publishing. We went on to do three more books at Random House – “Coming of Age,” “Toy Wars “ and “King of Hearts” – and one, “Top Brain, Bottom Brain,” at Simon & Schuster, where he is now president and CEO.

But the professional rewards are but a part of the story, a smaller part at that.

Because starting that day in Duxbury when I first met Hardy, we became dear friends and in the ensuing years – decades – would share many fine and often laugh-filled hours together. I would be welcomed into his family, and he into mine (he is the godfather of my son, Calvin). In recent days, as I have been on the phone with David and Eleanor, memories galore have surfaced about the human side of the man who was sometimes called “Hardly Human” for what Boston Globe obituary writer Bryan Marquard correctly called “his superhuman endurance during operations that lasted more than 24 hours and his ability to heal patients who couldn’t be cured anywhere else in the world.”

This human was funny, iconic, caring, loyal, loving and unique.

My daughter, Katy, and Hardy shared the same birthday!

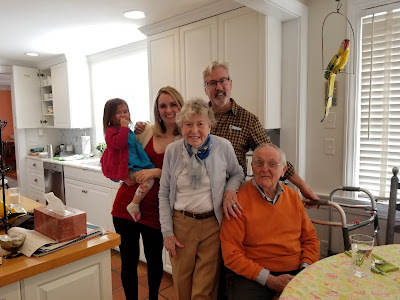

My daughter, Katy, and Hardy shared the same birthday!In Duxbury a few days before his 92d. L to R:

Katy's daughter, Viv; Katy; Eleanor; me and Hardt

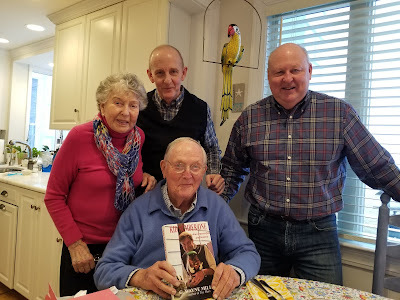

Hardy with Eleanor and sons Robbie and Will

Hardy with Eleanor and sons Robbie and Will on his 94th birthday, Feb. 7, 2020

He also was a decent biker. I know, because he took me on a ride on his motorcycle one day to visit the grave of his daughter, Sandra McLeod Hendren, a nurse who died of diabetes, a disease the master surgeon could not cure.

Since his death Tuesday, I have tried to calculate the number of lives he helped improve – the thousands directly on his table, the many more at the hands of the surgeons he trained, doctors including Jay Vacanti and Craig Lillehei and Patricia Donahoe.

I once asked Hardy how he found the stamina for his marathon operations.

“There’s a great big rest at the end,” he said.

Rest in peace, Hardy.

The sunrise outside the Hendren residence

The sunrise outside the Hendren residence on March 1, 2022. Courtesy of Astrid Hendren.

Watch a video of Hardy on his 90th birthday.

Dr. W. Hardy Hendren III: February 7, 1926, to March 1, 2022.

Hardy Hendren died this morning. I will have much more on him and his legacy tomorrow.

For now, this is the top of his obituary on The Hendren Project:

Dr. William Hardy Hendren III, a giant in American surgery, passed away peacefully at home on March 1, 2022, in Duxbury, MA, surrounded by the love and comfort of his family. The leading pediatric surgeon of his generation, Hendren was renowned worldwide for his pioneering ability to correct seemingly intractable anatomical conditions. He was 96.

Read the full obituary at https://www.hendrenproject.org/case/passing-w-h-hendren-iii-md

January 20, 2022

Traces of Mary: Read the reviews, order the book!

DESCRIPTION:

Despite carrying the scars of childhood trauma, Mary McAllister has enjoyed a successful career and become the mother of two wonderful children. Then their deadbeat father leaves, her young daughter dies, and she is hospitalized in a psychiatric center as she seeks to recover from this devastating loss. But she is not the same when she is released—and during escalating periods of crisis, she claims to be possessed by Z-DA, an evil creature from a distant galaxy that has come to earth in a war almost as old as the universe itself with Ordo, leader of a good species.

Is this real, or only extreme psychosis? Is Mary's young son, Billy, really Theus, the First Lieutenant for Ordo, as she increasingly believes? Is Billy's dead sister, Jessica, really reaching out to her brother for help in freeing her from the dark and distant place where she is trapped? As a city is engulfed in mayhem, events race toward a stunning conclusion in Traces of Mary, a one-of-a-kind mix of horror, science-fiction, thriller and mystery by best-selling author G. Wayne Miller.

ORDER "TRACES OF MARY" ON AMAZON

ORDER "TRACES OF MARY" ON BARNES & NOBLE

“ ‘Traces of Mary’ is a bold, bracing, blisteringly original hybrid tale that reads like Stephen King on steroids. G. Wayne Miller has penned a wild, psychedelic mind-bender of a book that challenges our sensibilities even as it hops across multiple genres with skill and aplomb. Call it horror, science fiction, mystery, thriller, or anything else you want, so long as you call it your next must-read.”

-- Jon Land, USA Today bestselling author.

“Strap yourself in for an intergalactic joy ride with Billy McAllister, the most engaging boy since Harry Potter, and a supporting cast starring his newly dead sister, Jess; his possessed mother, Mary; his uncle, Father John Lambert, a Jesuit priest; and a stuffed animal named Baby Bear. Throw in the evil Z-Da who is trying to kill Ordo, the leader of the Priscillas from a distant galaxy, Ordonia, and you’re in for a rare treat with ‘Traces of Mary.’ ”

-- Barbara Roberts, physician and author.

“This big-hearted novel follows an endearing 11-year-old boy who must navigate his mother's harsh reality of poverty, grief and mental illness. Along the way he discovers a place where resilience and faith are rewarded, where the miseries of the real world can be overpowered by the benevolence of a fantastical universe.”

-- Mark Johnson, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author.

“Supernatural horror? Check. Cosmic horror? Check. Science-fiction horror and childhood horror and psychological and religious and chemical horror? That's G. Wayne Miller's gripping Traces of Mary. Bonus: Billy, kid protagonist who is not a Harvard professor in kid skin. Bonus #2: Father Jack character, a Catholic priest who is neither a bumbler nor a perv. Flat-out, Traces of Mary is a five-star page-turner and a book to be remembered long after that last page.”

-- Mort Castle, Bram Stoker winner and best-selling horror author.

“G. Wayne Miller’s latest book is a complex, cross-genre tale of mystery and horror. Traces of Mary draws the reader into a dark world, both painfully realistic and fantastical, and doesn’t let go. Full of suspense and humor, it will keep you guessing until the very end.”

-- Jan Brogan, author of “The Combat Zone: Murder, Race and Boston’s Struggle for Justice”; “A Confidential Source”; and the Hallie Ahern mystery series.

“G. Wayne Miller has given the world a diversity of wonderful books, bestsellers that captivate, inform and otherwise transport his readers to new worlds. With Traces of Mary, Miller again dips his talented pen into the ink of imagination, giving readers a bold, immersive story that will captivate, thrill and thoroughly entrance.

“With a cast of memorable characters enriching his detailed storyline, Miller anchors Traces of Mary with Mary McAllister, a mother of two who is plunged into a chaos that challenges her very core. Miller fills this story with people of dimension and believability, as he swiftly unfurls the action through scene development and snappy, concise dialogue. Each character quickly comes to vibrant life and each scene ties into the overall arc of this tale. Readers will appreciate the depth of untold backstory giving this novel a deliciously rich, environmental context. Miller’s gift for creating a cinematic flow is marvelously alive in Traces of Mary. Traces of Mary crackles with other-worldly suspense. A storytelling gem.”

-- John Busbee, founder and producer of The Culture Buzz, Iowa’s independent cultural voice, for KFMG 98.9 FM, Des Moines, Iowa.

"The Legendary G. Wayne Miller has done it again! The mix of science fiction with psychological terror is the perfect match for this sublime story!"

-- Mark Slade, author, podcaster and anthologist.

"G. Wayne Miller's prose is electric in this genre-bending, mind-boggling, and devilishly good horror novel."

-- Ksenia Murray, Author of “The Cave”

“Perhaps it is his history as a reporter, or his investigative non-fiction, but either way, G. Wayne Miller has a way of delivering a suspenseful crime story with believable reality and scope. He leaves it to the readers to decide if the looming conclusion is paranormal or a natural horror, but by the end of ‘Traces for Mary,’ you will be at the edge of your seat.”

-- Chauncey Haworth, radio show host, podcaster and writer.

January 16, 2022

My review of Though the Earth Gives Way: 'A masterpiece'

“Though the Earth Gives Way,” by Mark S. Johnson. Bancroft Press, 288 pages. $25.

With his fiction debut, “Though the Earth Gives Way,” Mark S. Johnson has delivered a masterpiece. Beautifully written, with unforgettable settings and characters, this post-apocalyptic tale is a warning that disaster of unimaginable magnitude awaits us if we do not act urgently to mitigate the effects of manmade climate change.

That disaster in Johnson’s book?

A West Coast turned furnace, an East Coast flooded beyond repair, the region between the coasts a wasteland, literally. Technology gone, all of it — electricity, the internet, cellphones, motor vehicles, the entire infrastructure on which a nation and world was built — reduced to relics now. Survivors turned migrants walking on foot to they-know-not-where, some armed and dangerous, others victimized, all suffering physical and mental wounds as they cross a landscape littered with corpses of homo sapiens and other animals. Only the insects thrive here.

And yet, as grim as America has become in this not-too-distant future, “Though the Earth Gives Way” is also a story about friendship and family, the power of memory, the fear and allure of the future, and, yes, even the hope that might be found in a living hell.

More: USA Today names 'Though the Earth Gives Way' one of 20 winter books we can't wait to read

Johnson, formerly a Providence Journal staff writer, is a health and science reporter for The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. He shared the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting and has been a Pulitzer finalist three times. His science expertise shows in “Though the Earth Gives Way,” but it does not drive the narrative.

Mark S. Johnson

Mark S. JohnsonStorytelling, at the level of Stephen King and Cormac McCarthy, other masters of dystopian fiction, does.

The narrator, Elon, left Rhode Island when the coast became uninhabitable. Foraging for food, his clothes fetid and his only belongings ferried in a shopping cart, he has limped to the woods of Michigan, where he stumbles on an old retreat center now occupied by an unnamed old man who takes him in, providing food and shelter. Soon they are joined by fellow wanderers: Clarie and Elissa, a lesbian couple; Asher, a rough-hewn Floridian, and Amira, the young woman who has traveled with him; Johannes, who escaped California but with the best intentions left his wife behind, a decision that now haunts him; Hunter, a tormented teenager; and Nizar, a Syrian who fled the horrors of his war-decimated native land for America.

Slowly, these nine gain a degree of trust, supporting each other and becoming a sort of family. Central to their growing bonds are the nightly stories that each tells around a fire, a timeless place for sharing. Imagine your own fireplace, firepit or campfire. Imagine the fires in cave times, where storytelling may well have been born.

Johnson’s command of voice in these separate stories is magnificent, with each character’s tale fitting what we learned of them before their tellings — and going beyond, deepening our understanding of each of them, and of humanity in general.

Nizar gives as good a description of storytelling as I have seen, saying: “We trade in stories, don’t we? That’s how we unlock intimacy in each other. The stories don’t have to be big or dramatic. Most of what happens in our lives is so ordinary. We leave so little trace that we were ever here. Stories help us forget how small we truly are. They are a way to leave a few footprints in the sand.”

The real-life takeaway of “Though the Earth Gives Way” is that scorched sand and submerged terra firma are the future awaiting us if our present course is not changed.

As Asher describes our world on the eve of ultimate crisis, “what we had wasn’t no monument to human beings. Guys sticking guns in your face for money. Pointless bar fights. Wars over the stupidest s---. And, yeah, someone figured out how to make a very small, very fancy phone. Yet when people told us — smart people — that we were destroying the planet, we did what? We argued. We couldn’t work together when our lives depended on it. Literally.”

That is America and the world today, not only in Johnson’s dystopian future.

Unlike his book, which ends when the old retreat center goes up in flames — caused by fire, ignited by unexpected means — there may still be time.

“I’ve been dreaming of mountains,” Elon says at the end.

Mountains, Johnson argues, that we must climb now if complete catastrophe is to be averted.

Staff Writer G. Wayne Miller is the author of 19 books. His 20th, "Traces of Mary," will be published in March.

This review was originally published in The Providence Journal on January 9, 2022.

December 11, 2021

Nineteen years ago today. RIP, Dad.

Author's Note: I wrote this nine years ago, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of my father's death. Like his memory, it has withstood the test of time. I have slightly updated it for today, December 11, 2021, the 19th anniversary of his death. Read the original here.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 18 years ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 19th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 18 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now for four years and my best friend for more than a decade: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, Bella, Livvie and Viv, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister Mary Lynne and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died in 2015. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

My dad, second from top, with two of his sisters and his brother.

My dad, second from top, with two of his sisters and his brother.October 30, 2021

Happy Halloween! In the spirit of the day, I present "Death Train," one of the shorts in my collection "Vapors: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, Vol 2"

Death Train

From across the Iowa cornfields, sneaking through the early September night, Luke can hear it coming closer, closer, louder: The death train, starting to slow, easing up on the throttle, going to be a stop tonight.

Cat-like, he goes to his bedroom window, peers through the screen, the outside smells rich and sweet, harvest can't be but a week off.

He shivers and his upper body is getting a case of the chills again and at first he can't look.

Then he looks and...

...nothing.

'Course there's nothing. Can't see the death train, no sir. Death train don't run with lights. Don't have no switchmen with kerosene lanterns, don't have no friendly caboose rip-rollin' along, a big old pot belly stove burning.

Can hear it, though, sure you can, the clackety-clack of its wheels, the breathing heaving fire of its steam-engine belly, the laughter of its death engineer as he gets ready to pull down on the death whistle.

Matthew said:

(Listen to it, but don't listen to it for very long, Lukey my boy. Them that listens to it too long is as good as ---

(Don't say that word.

(Is goin' for a ride.)

``What is it, Luke?'' The voice is old and stern, the voice of Uncle John. Luke starts, like he's been caught touching himself where he oughtn't to. He turns toward the light, a single 25-watt bulb hanging on a black cord from the hall ceiling. There he is now, Uncle John, his fat, doughy body filling the doorway to Luke's room. He's rubbing the sleep from his eyes. He's sweating. Always sweating, Uncle John.

``I asked you a question, boy, and I expect an answer. What is it?''

``Nothing,'' Luke says, thinking desperately there must be some way to explain everything without really explaining anything at all.

``Gotta be somethin', it bein' past 1 in the ayem and you kneelin' by your window, son, lookin' out over a cornfield that's as black as pitch. Gotta be somethin'. Nothin' don't look like this. Nothin's nothin. This is somethin'.''

``It was just, just a---''

``Train, Luke? You gonna say train?''

``A crow, uncle. Eating on the corn. Honest, I heard it.''

``Crows don't fly by night. You know better than that, son.''

``You leave him alone, you old fool. You hear me?''

Now Aunt Edna is up. He listens to the softness of her slippers gliding across the upstairs hall floor. He can hear the rustle of her silk nightgown, disturbing the end-of-summer heat that hangs heavy and wet and still, like the YMCA pool on a busy Saturday, up here on the second story.

``Stay out of it, Edna. Just stay out of it.''

Great big hissing, the death train, its death wheels turning slower, the sound of metal brake on metal axle like fingernails on a grammar-school chalkboard.

``What is it, Luke? A nightmare?'' Her voice is soothing, cool, like the autumn that doesn't seem to want to come this year. She never talks to John like that, only him. Only Luke, the child nature never let her have, the child her no-good sister left for her that day she packed her bags and left for California, goodbye and good riddance.

``No, Auntie. It's not a dream.''

``What is it then, Luke?''

``It's the...''

``What, Luke? What do you hear?''

Should he say the word? Should he?

Edna pushes past John. John grunts like a hungry old sow. On a Saturday night, after filling his body with bourbon and beer, he might have started in on her, his voice getting filthy and loud and his face turning redder than a freshly painted barn. Might have wished her stinking lousy soul to hell, and Luke's right along with it, the two of them be damned forever.

``Train,'' Luke says.

It's more than John can take. ``Now, you know there ain't no train within 50 miles of here, son. Never has been. Never been no old tracks, no new tracks, no way, no how. County road, and that's it. We been through all that before.''

Aunt Edna has his arm around him. She is gazing out with him over the corn, dark and mysterious and speaking in hushed tones under a sluggish breeze that barely has the strength to reach the farmhouse. Whole summer's been like that, hazy, humid, never-ending. Overhead, there is a rind of moon, and it shines ghostly through the cornfields, over the barn, past the oak grove and beyond to where---

I can hear the death train grinding to a halt.

Death whistle blowing, a low, shivering sound as might come echoing around and behind and through and off of the cracked marble stones in that graveyard out back of St. George's Episcopal Church. Out in that graveyard alone on a late November afternoon, it could be, Uncle John's corn crop long since in, the pumpkins going orange to brown, the air promising flurries, the daylight draining away into the trees, the shadows lengthening.

That kind of day, Matthew said, you might hear it.

Or on the sunniest most perfect day God ever did make -- then, then you might hear it, too.

Matthew said:

(Heard it myself there more than once, Lukey boy. In the churchyard.

(Heard what?

(Why, the death train, death whistle blowin' full away. And don't it make sense, boy, hearin' it there? Hearin it where it stops? Don't it now?

(I guess it does.

(Sure it does. Sure.)

Luke covers his ears. He starts to cry.

``You make him stop that now,'' John bellows to the woman who long since stopped sharing his bed, his room, his life. ``You get him back in that bed, Edna, so's we can have peace and quiet. A man can't even get a good night's sleep in his own house no more, all this horseshit goin' on. Been goin' on now two years, it has. I mean to put a stop to it.''

``You shut up, John. Just keep that trap of yours shut. Can't you see he's afraid?''

``Nine years old, and afraid of the dark. It's downright sinful, is what it is.''

``I told you, shut up.''

``Where's he get all this nonsense, that's what I'd like to know.''

``Go back to your room, John. I'll handle this. This is none of your concern.'' She's sounding angry now, Aunt Edna is, angry like the day she threw that young whippersnapper from the electric company right out of the front parlor.

``Goin' on like somebody fresh on the lam from the looney bin.''

``Put a lid on it, John.''

``Well, I'll tell you where he gets this,'' John goes on, the rage building in his voice. ``From Matthew Dorfman, that's where.''

``Matthew Dorfman's your best worker,'' Edna says. ``Anybody around here's talkin' nonsense, it's you, John Johnson.''

``Idiot, no-good, sonofabitch Matthew Dorfman. Sits on his brains, that one does. Tomorrow, gonna fire him. Don't need no farmhand gettin' this kid riled up like that. First light, gonna fire him. That'll put an end to this midnight crap with the kid here.''

``Matthew's my friend,'' Luke says, but John doesn't hear him.

Matthew said:

(They laugh at me, Lukey, all the time. Call me names. Your own uncle's 'bout the worst.

(Why, Matt?

(Folks are like that, I guess. Mean, some of 'em. Downright mean. You look a little different, talk a little slow, and they laugh at you. Human nature, I guess. The dark side of things.

(But I like you, Matt.

(I like you, too, Luke.

(And I don't think you look strange. Honest, I don't.

(You're a good boy, Lukey. Gonna be a fine man. I'll see to that. I'll see you make it.)

``It's okay, Luke,'' Edna says when John's gone back to his room.

Eleven stops the death train's made in Carson's Corners since Luke started hearing it two years ago, the same summer Uncle John brought a simple-minded out-of-towner named Matthew Dorfman onto the payroll. Eleven folks ticketed, boarded and taken away. Phyllis Smith, who died of a heart attack the evening of the day she had tea with Edna. Uncle John's schoolhood buddy George Snyder, who put the barrel of a shotgun into his mouth and pulled the trigger the third night of a three-day drinking binge. Mr. and Mrs. Gerard and their two children, killed instantly in a car crash a mile down Route 16, right there by the end of Uncle John's number-two cornfield. The three scouts from Troop 112, drowned when their canoe tipped over the afternoon of St. George's annual parish picnic. Old Mrs. Wannamaker, the Sunday morning Bible teacher, whose house burned down Christmas Eve.

Matthew said:

(Trains run on schedule, Luke.

('Course they do.

('Specially this one.

('Specially this.

('Course, it ain't no ordinary schedule. Comes and goes as it sees fit, if you get what I mean.

(I do.

(Ever wonder who makes up those funny schedules, Lukey, my boy?

(Never did. Who, Matt? Who makes them up?

(Folks that run 'em, that's who.

(But who runs them, Matt?

(Can't tell you that, my boy. Don't know myself. But it's gonna be someone pretty important, right? Train that big?

(Right.)

They stay by the window, sitting, staring out, Edna's arms around Luke.

Death train's stopped now. Baggage's being unloaded. Taking on water. What's that bang? Must be adding on a car. Must be that.

In his room, John closes his eyes and is almost asleep when he swears he hears it, from across the moonlit fields: a sound like a train whistle, then the uncomfortable grating of metal spinning on metal, and then, as the death train gets traction, builds momentum, a steady chug-a-lug-a-lugging.

He thinks of Luke, but only for a moment, because the aneurism that's been quietly blowing up inside his brain finally bursts, flooding his skull and drowning out the scream starting to form on his lips.

``On its way, ain't it, Luke?'' Edna whispers as the breeze suddenly freshens and the staleness begins to move out of the farmhouse.

He shakes his head, Luke does. ``Yes, Auntie. On its way.''

On his forehead the new wind is cool, comforting, reminding. Outside, the cornfields are dark, quiet, asleep.