G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 17

May 8, 2018

#33Stories: No. 8, "The Work of Human Hands"

#33Stories

No. 8: “The Work of Human Hands”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in 1993 by Random House.

Introduction to the new edition, Crossroad Press, 2012:

During the course of my writing career, I have been privileged to meet many extraordinary people, from many walks of life. Hardy Hendren belongs to a rare class. Measured by the good he has done for so many others, directly through his operations and indirectly through his teachings and the surgeons he trained (and the surgeons they have now trained), he ranks with another pioneer I knew and wrote about in my book King of Hearts: C. Walton Lillehei, remembered as The Father of Open Heart Surgery. A rare class, indeed: a class of two.

This new edition of The Work of Human Hands, which includes an updated Epilogue, remains a testament to Hardy’s impact on countless thousands of lives.

To that group, I must add my own.

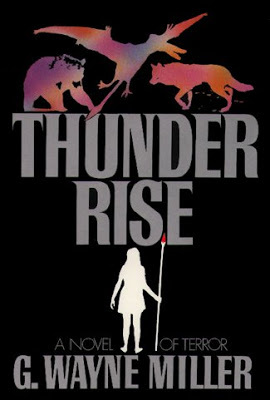

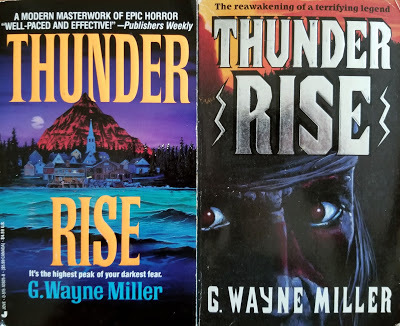

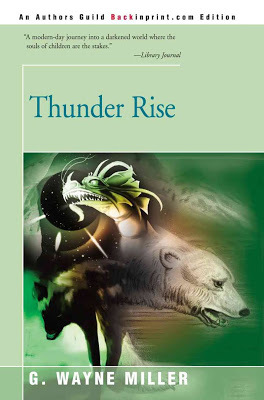

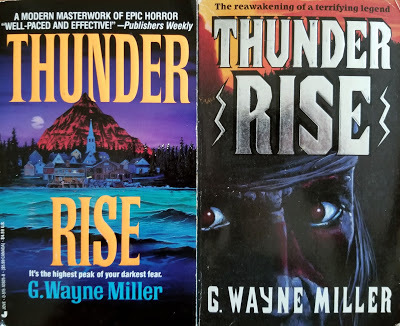

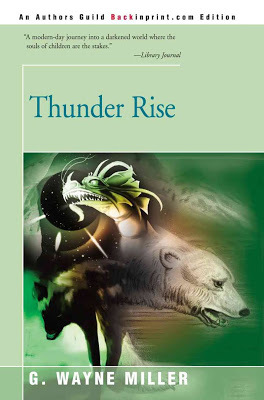

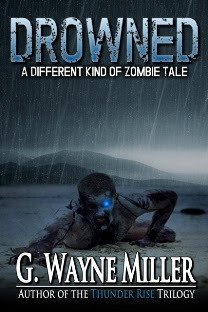

As recounted in the Foreword, I met Hardy almost 25 years ago, when I was at a critical juncture in my development as a writer. I had published one book, Thunder Rise, a horror/mystery novel, and I had dreams of one day writing only fiction. My day job was staff writer at The Providence Journal, a newspaper published every day since its founding in 1829. Hardy welcomed me into his world and the book that resulted began my run as a non-fiction author –– a run that allowed me the freedom to continue my fiction and also to make movies.

But Hardy gave me something more valuable than a professional boost. He gave me reminders of the value of hard work and discipline; of the need for honesty, decency and charity; of the importance of family; and of the eventual rewards of perseverance, even when the going is protracted and tough, as writing, like life, often is. More than this, Hardy gave lasting friendship, along with did Eleanor, his lovely wife. He brought my three children into his circle (he is godfather to my son, Calvin). Hardy and I continue to share stories, laughs and joys (and a few sorrows). I sometimes turn to him for counsel, and he sometimes seeks mine. Some will say this crosses a journalistic line, but for every rule, there is an exception. This rule, I gladly break. So Hardy, my heartfelt thanks.

In preparing this edition of The Work of Human Hands with Crossroad publisher David N. Wilson (to whom I also owe a debt of gratitude), Hardy and I spoke repeatedly on the phone, and the emails went back and forth. On the eve of bringing his non-profit educational foundation to fruition, his gift to generations now and in the future, Hardy felt honored to have the book return to print. In one of his messages to me, he summarized the mutual sentiments that were forged so many years ago, when researching and writing the words on these pages. He wrote:

“I have always felt it was my good fortune that you came to see me with a book in mind! From that came a great book and a very valued lifelong friendship. Any time the Millers would like to breathe the pure Duxbury air, come with the whole family.”

The invitation, as you might imagine, holds true on this end, too.

In my book (as it were), Hardy Hendren is the best.

-- 30 --

READ on Kindle

READ on iTunes

LISTEN on Audible

READ the paperback edition.

Context:

Fate is a funny thing. I was a journalist by day and a horror/mystery/sci-fi writer by night (and early morning) when, in 1989, the year “Thunder Rise” was published, a young man who had worked briefly (and brilliantly) at The Providence Journal after graduating from Brown University contacted me. Jon Karp had taken a job as an editorial assistant at Random House. He said he had always liked my writing and wondered if I had any book ideas.

I did: “Asylum,” the sequel to “Thunder Rise.”

Jon did not want fiction. Did I have any non-fiction ideas?

I did: Dr. W. Hardy Hendren, the chief of surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital, a true surgical miracle worker. Jon liked that. “The Work of Human Hands” was the first book he ever bought – but hardly the last in his long and distinguished career. He went on to buy and edit three more of my non-fiction books at Random House -- and more recently he bought a fifth, “Top Brain, Bottom Brain,” co-authored with neuroscientist Stephen M. Kosslyn, as publisher of Simon & Schuster, the title he holds today. Jon took a chance on me in 1989 when there was little reason to – my single published book was horror! – and I remain grateful to this day.

The reviews for “The Work of Human Hands” were positive, including these glowing words from the Los Angeles Times. I remember vividly when Jon called with work of it – how excited he was: "Only rarely does a work of nonfiction equal or surpass the novel in the art of storytelling, the play of emotion and the sheer grandeur of human spirit. Alive! by Piers Paul Read was such a book. So was Bruce Chatwin's The Songlines and, more recently, Norman Maclean's Young Men and Fire. To this short list I must add The Work of Human Hands.''

The Chicago Tribune also liked the book, writing "Worshipful biographies of great surgeons are so common that one must really be special to merit attention. This one is.'' And how thrilling to receive my first review in The New York Times, with the Book Review stating “"Mr. Miller reminds us that in the hands of visionary and dedicated doctors, miracles still happen.''

Synopsis:

THE WORK OF HUMAN HANDS is a timeless medical journey through pioneering surgeon Dr. Hardy Hendren’s legendary operating room that the Los Angeles Times called “impossible to forget.”

Set at Boston Children’s Hospital, which U.S. News & World Report consistently rates as America’s best children’s hospital, THE WORK OF HUMAN HANDS is available now for the first time in digital format and a new paperback will also be available soon. The new edition includes a fresh introduction and a greatly expanded epilogue updating readers on Hendren and patient Lucy Moore today.

The central narrative remains an epic story of struggle against seemingly impossible odds as Hendren faces one of his biggest challenges: Lucy Moore, a fourteen-month-old girl born with life-threatening defects of the heart, central nervous system and genitourinary system. Before Hendren, surgeons regarded Lucy's condition as fatal.

But at the hands of master surgeon Hendren, she will go on to lead a normal life. And Hendren is aided in that quest by Aldo R. Castaneda, the pioneering cardiac surgeon, and R. Michael Scott, the internationally renowned neurosurgeon. Hendren, Castaneda and Scott are all affiliated with the Harvard Medical School.

The Work of Human Hands is also the story of a revered hospital, its lore, its people and their remarkable accomplishments – an example of the best of health care in America. Poignant and dramatic, lively and engrossing, with breathtaking insight into the craft of surgery, The Work of Human Hands is medical and literary journalism at its best.

“At a time when TV shows like Grey’s Anatomy and ER win huge followings for their stories, The Work of Human Hands stands out as a real-life medical drama with a cast of uniquely colorful characters,” said Crossroad publisher David N. Wilson. “We are thrilled to publish this new edition of the classic Work of Human Hands.”

Said author G. Wayne Miller: “At a time when health care dominates the public discourse, and rightly so, it’s refreshing to rejoice in the triumphs. American medicine truly can perform miracles.”

Today, the 14-month-old baby who spent nearly 24 hours on Hendren’s operating table is a college graduate, fully healed. Hendren performed his last surgery in 2004, when he was 78, but he continues to work full-time on his non-profit W. Hardy Hendren Education Foundation for Pediatric Surgery and Urology. He still receives some of the world’s most prestigious medical honors, most recently the Jacobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons, in June 2012.

The publisher and author are donating a portion of the proceeds from this edition of The Work of Human Hands to the Hendren Foundation.

The paperback edition, 1999, Borderlands Press.

The paperback edition, 1999, Borderlands Press.

No. 8: “The Work of Human Hands”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in 1993 by Random House.

Introduction to the new edition, Crossroad Press, 2012:

During the course of my writing career, I have been privileged to meet many extraordinary people, from many walks of life. Hardy Hendren belongs to a rare class. Measured by the good he has done for so many others, directly through his operations and indirectly through his teachings and the surgeons he trained (and the surgeons they have now trained), he ranks with another pioneer I knew and wrote about in my book King of Hearts: C. Walton Lillehei, remembered as The Father of Open Heart Surgery. A rare class, indeed: a class of two.

This new edition of The Work of Human Hands, which includes an updated Epilogue, remains a testament to Hardy’s impact on countless thousands of lives.

To that group, I must add my own.

As recounted in the Foreword, I met Hardy almost 25 years ago, when I was at a critical juncture in my development as a writer. I had published one book, Thunder Rise, a horror/mystery novel, and I had dreams of one day writing only fiction. My day job was staff writer at The Providence Journal, a newspaper published every day since its founding in 1829. Hardy welcomed me into his world and the book that resulted began my run as a non-fiction author –– a run that allowed me the freedom to continue my fiction and also to make movies.

But Hardy gave me something more valuable than a professional boost. He gave me reminders of the value of hard work and discipline; of the need for honesty, decency and charity; of the importance of family; and of the eventual rewards of perseverance, even when the going is protracted and tough, as writing, like life, often is. More than this, Hardy gave lasting friendship, along with did Eleanor, his lovely wife. He brought my three children into his circle (he is godfather to my son, Calvin). Hardy and I continue to share stories, laughs and joys (and a few sorrows). I sometimes turn to him for counsel, and he sometimes seeks mine. Some will say this crosses a journalistic line, but for every rule, there is an exception. This rule, I gladly break. So Hardy, my heartfelt thanks.

In preparing this edition of The Work of Human Hands with Crossroad publisher David N. Wilson (to whom I also owe a debt of gratitude), Hardy and I spoke repeatedly on the phone, and the emails went back and forth. On the eve of bringing his non-profit educational foundation to fruition, his gift to generations now and in the future, Hardy felt honored to have the book return to print. In one of his messages to me, he summarized the mutual sentiments that were forged so many years ago, when researching and writing the words on these pages. He wrote:

“I have always felt it was my good fortune that you came to see me with a book in mind! From that came a great book and a very valued lifelong friendship. Any time the Millers would like to breathe the pure Duxbury air, come with the whole family.”

The invitation, as you might imagine, holds true on this end, too.

In my book (as it were), Hardy Hendren is the best.

-- 30 --

READ on Kindle

READ on iTunes

LISTEN on Audible

READ the paperback edition.

Context:

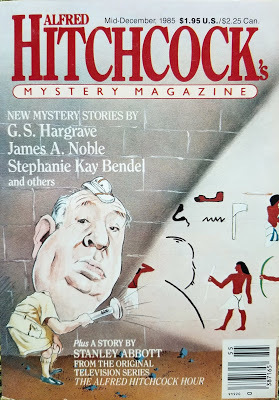

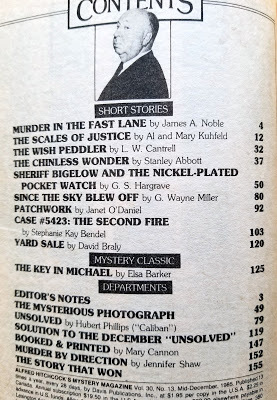

Fate is a funny thing. I was a journalist by day and a horror/mystery/sci-fi writer by night (and early morning) when, in 1989, the year “Thunder Rise” was published, a young man who had worked briefly (and brilliantly) at The Providence Journal after graduating from Brown University contacted me. Jon Karp had taken a job as an editorial assistant at Random House. He said he had always liked my writing and wondered if I had any book ideas.

I did: “Asylum,” the sequel to “Thunder Rise.”

Jon did not want fiction. Did I have any non-fiction ideas?

I did: Dr. W. Hardy Hendren, the chief of surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital, a true surgical miracle worker. Jon liked that. “The Work of Human Hands” was the first book he ever bought – but hardly the last in his long and distinguished career. He went on to buy and edit three more of my non-fiction books at Random House -- and more recently he bought a fifth, “Top Brain, Bottom Brain,” co-authored with neuroscientist Stephen M. Kosslyn, as publisher of Simon & Schuster, the title he holds today. Jon took a chance on me in 1989 when there was little reason to – my single published book was horror! – and I remain grateful to this day.

The reviews for “The Work of Human Hands” were positive, including these glowing words from the Los Angeles Times. I remember vividly when Jon called with work of it – how excited he was: "Only rarely does a work of nonfiction equal or surpass the novel in the art of storytelling, the play of emotion and the sheer grandeur of human spirit. Alive! by Piers Paul Read was such a book. So was Bruce Chatwin's The Songlines and, more recently, Norman Maclean's Young Men and Fire. To this short list I must add The Work of Human Hands.''

The Chicago Tribune also liked the book, writing "Worshipful biographies of great surgeons are so common that one must really be special to merit attention. This one is.'' And how thrilling to receive my first review in The New York Times, with the Book Review stating “"Mr. Miller reminds us that in the hands of visionary and dedicated doctors, miracles still happen.''

Synopsis:

THE WORK OF HUMAN HANDS is a timeless medical journey through pioneering surgeon Dr. Hardy Hendren’s legendary operating room that the Los Angeles Times called “impossible to forget.”

Set at Boston Children’s Hospital, which U.S. News & World Report consistently rates as America’s best children’s hospital, THE WORK OF HUMAN HANDS is available now for the first time in digital format and a new paperback will also be available soon. The new edition includes a fresh introduction and a greatly expanded epilogue updating readers on Hendren and patient Lucy Moore today.

The central narrative remains an epic story of struggle against seemingly impossible odds as Hendren faces one of his biggest challenges: Lucy Moore, a fourteen-month-old girl born with life-threatening defects of the heart, central nervous system and genitourinary system. Before Hendren, surgeons regarded Lucy's condition as fatal.

But at the hands of master surgeon Hendren, she will go on to lead a normal life. And Hendren is aided in that quest by Aldo R. Castaneda, the pioneering cardiac surgeon, and R. Michael Scott, the internationally renowned neurosurgeon. Hendren, Castaneda and Scott are all affiliated with the Harvard Medical School.

The Work of Human Hands is also the story of a revered hospital, its lore, its people and their remarkable accomplishments – an example of the best of health care in America. Poignant and dramatic, lively and engrossing, with breathtaking insight into the craft of surgery, The Work of Human Hands is medical and literary journalism at its best.

“At a time when TV shows like Grey’s Anatomy and ER win huge followings for their stories, The Work of Human Hands stands out as a real-life medical drama with a cast of uniquely colorful characters,” said Crossroad publisher David N. Wilson. “We are thrilled to publish this new edition of the classic Work of Human Hands.”

Said author G. Wayne Miller: “At a time when health care dominates the public discourse, and rightly so, it’s refreshing to rejoice in the triumphs. American medicine truly can perform miracles.”

Today, the 14-month-old baby who spent nearly 24 hours on Hendren’s operating table is a college graduate, fully healed. Hendren performed his last surgery in 2004, when he was 78, but he continues to work full-time on his non-profit W. Hardy Hendren Education Foundation for Pediatric Surgery and Urology. He still receives some of the world’s most prestigious medical honors, most recently the Jacobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons, in June 2012.

The publisher and author are donating a portion of the proceeds from this edition of The Work of Human Hands to the Hendren Foundation.

The paperback edition, 1999, Borderlands Press.

The paperback edition, 1999, Borderlands Press.

Published on May 08, 2018 06:06

May 7, 2018

#33Stories: No. 7, "God Can Be a Cruel Bastard"

#33Stories

No. 7: “God Can Be a Cruel Bastard”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

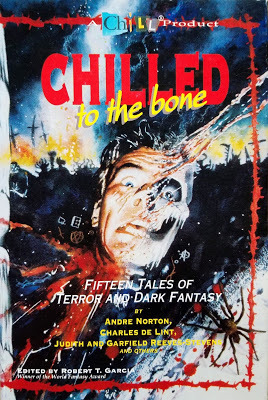

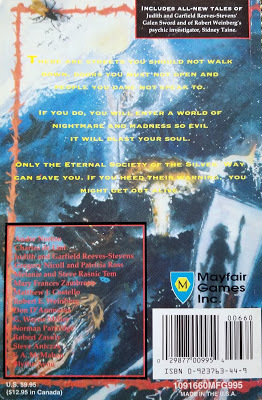

Originally published in “Chilled to the Bone,” 1990, The Berkley Publishing Group.

pp. 234 - 235 of "God Can Be a Cruel Bastard":

At 11: 30, I left the bar and drove to Sunset Point. It was Monday, a night off for Wakefield's holy hell-raisers, and I wasn't terribly worried about the police. The cemetery gates were secured with a chain and lock for the night, but I was prepared for that. Before leaving New York, I'd purchased bolt-cutters – spent almost 50 bucks for them – and they did the job cleanly and easily. I drove through, stopped, and closed the gates behind me.

It was a cinch finding Steve's grave. I parked by the war memorial, got out and opened the trunk. It was full of tools. Brand-new tools I'd bought at the same store where I'd purchased the bolt-cutters. There was a shovel. A crow bar. A sledgehammer. A screwdriver. A battery-powered lantern. I hadn't found a winch.

Before I picked up any of those tools, I stood.

Stood and remembered once again – there were a million memories that day, too many to begin to sort out – remembered the high-school conversations we'd had not far from here.

It had always been Steve's biggest nightmare.

That someday he would die, and having no say from that point on about the fate of his earthly remains, he would be buried. That having been buried, having been locked into his satin-lined box – tons of earth above him, six feet of hard-packed earth impenetrable to sound – he would wake up.

Wake up.

Fully conscious.

In his casket.

His locked, pitch-dark casket. Would wake up like that, and would run his fingers along the cloth, would pry his frantic fingers into the joint between the coffin's lid and bottom, would locate the hinges... rusted solid, rusted forever...

and then he would scream.

Scream through bloodless lips. Scream, the impossibly stuffy air filling his lungs, his fingers tearing madly at his surroundings, his sweat profuse and dank like the mold already beginning to grow around him.

And then – then, at the moment when panic was greatest – there would be the pronouncement.

Maybe it would only be inside his head. Maybe it would actually be a voice, deep, throaty, authoritative.

God's voice.

Forever.

Just that single word, forever.

Steve would hear it, and he would begin to scream again, and then it would happen... utter hopelessness, drowning him.

But not truly drowning him, of course.

Forever.

Never to sleep.

No eternal rest.

God can be a cruel bastard, he always said. Wouldn't that be a cruel bastard kind of thing to do? Wouldn't that bring a smile to a cruel bastard's lips?

Please don't think Steve was a morbid son of a bitch, because he wasn't. Not about most stuff. He didn't believe in ghosts or goblins or vampires or spirits or any of that flapdoodle. Just this hangup, this crazy conviction that God was saving this practical joke for him – him, specifically for him, a conviction so firm you'd think it had been written in the Bible somewhere.

I should mention that Steve had another fear that chilled him to the bone. Claustrophobia. The paralyzing fear of enclosed spaces. The fear of closets, phone booths, tunnels, caves.

And coffins....

-- 30 –

READ “God Can Be a Cruel Bastard” in “Since the Sky Blew Off: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction Vol. 1, Kindle Edition.”

Context:

They say horror writers exorcise their fears by writing. They’re right. “God Can Be a Cruel Bastard” is how I tried to chase one of mine back in the early 1990s.

It also is an example, one of many, where you will find a degree of reflection and commentary on social and cultural issues, including politics, the treatment of women, the stigma surrounding those living with mental illness and intellectual disability – and, in this case, religion. Raised Roman Catholic during the era of the unforgiving and scary Baltimore Catechism by the daughter of Irish immigrants (and a once-Protestant father who converted), I was trying to make sense of organized faith, which for some is salvation and blessing, and for others cruelty and real-life horror. Look around the world today.

But I digress. Come back tomorrow for an uplifting story about a real-life miracle worker…

No. 7: “God Can Be a Cruel Bastard”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in “Chilled to the Bone,” 1990, The Berkley Publishing Group.

pp. 234 - 235 of "God Can Be a Cruel Bastard":

At 11: 30, I left the bar and drove to Sunset Point. It was Monday, a night off for Wakefield's holy hell-raisers, and I wasn't terribly worried about the police. The cemetery gates were secured with a chain and lock for the night, but I was prepared for that. Before leaving New York, I'd purchased bolt-cutters – spent almost 50 bucks for them – and they did the job cleanly and easily. I drove through, stopped, and closed the gates behind me.

It was a cinch finding Steve's grave. I parked by the war memorial, got out and opened the trunk. It was full of tools. Brand-new tools I'd bought at the same store where I'd purchased the bolt-cutters. There was a shovel. A crow bar. A sledgehammer. A screwdriver. A battery-powered lantern. I hadn't found a winch.

Before I picked up any of those tools, I stood.

Stood and remembered once again – there were a million memories that day, too many to begin to sort out – remembered the high-school conversations we'd had not far from here.

It had always been Steve's biggest nightmare.

That someday he would die, and having no say from that point on about the fate of his earthly remains, he would be buried. That having been buried, having been locked into his satin-lined box – tons of earth above him, six feet of hard-packed earth impenetrable to sound – he would wake up.

Wake up.

Fully conscious.

In his casket.

His locked, pitch-dark casket. Would wake up like that, and would run his fingers along the cloth, would pry his frantic fingers into the joint between the coffin's lid and bottom, would locate the hinges... rusted solid, rusted forever...

and then he would scream.

Scream through bloodless lips. Scream, the impossibly stuffy air filling his lungs, his fingers tearing madly at his surroundings, his sweat profuse and dank like the mold already beginning to grow around him.

And then – then, at the moment when panic was greatest – there would be the pronouncement.

Maybe it would only be inside his head. Maybe it would actually be a voice, deep, throaty, authoritative.

God's voice.

Forever.

Just that single word, forever.

Steve would hear it, and he would begin to scream again, and then it would happen... utter hopelessness, drowning him.

But not truly drowning him, of course.

Forever.

Never to sleep.

No eternal rest.

God can be a cruel bastard, he always said. Wouldn't that be a cruel bastard kind of thing to do? Wouldn't that bring a smile to a cruel bastard's lips?

Please don't think Steve was a morbid son of a bitch, because he wasn't. Not about most stuff. He didn't believe in ghosts or goblins or vampires or spirits or any of that flapdoodle. Just this hangup, this crazy conviction that God was saving this practical joke for him – him, specifically for him, a conviction so firm you'd think it had been written in the Bible somewhere.

I should mention that Steve had another fear that chilled him to the bone. Claustrophobia. The paralyzing fear of enclosed spaces. The fear of closets, phone booths, tunnels, caves.

And coffins....

-- 30 –

READ “God Can Be a Cruel Bastard” in “Since the Sky Blew Off: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction Vol. 1, Kindle Edition.”

Context:

They say horror writers exorcise their fears by writing. They’re right. “God Can Be a Cruel Bastard” is how I tried to chase one of mine back in the early 1990s.

It also is an example, one of many, where you will find a degree of reflection and commentary on social and cultural issues, including politics, the treatment of women, the stigma surrounding those living with mental illness and intellectual disability – and, in this case, religion. Raised Roman Catholic during the era of the unforgiving and scary Baltimore Catechism by the daughter of Irish immigrants (and a once-Protestant father who converted), I was trying to make sense of organized faith, which for some is salvation and blessing, and for others cruelty and real-life horror. Look around the world today.

But I digress. Come back tomorrow for an uplifting story about a real-life miracle worker…

Published on May 07, 2018 03:58

May 6, 2018

#33Stories: No. 6, "Freddy and Rita"

#33Stories

No. 6: “Freddy and Rita”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in NECON stories, 1990, Three Bobs Press, Providence, R.I.

pp. 40 – 41 of “Freddy and Rita”:

The missiles fall at noon on a perfect August day. New York, Washington, Houston, Los Angeles –– all gone, instantly. Springfield, Massachusetts, a small city west of Boston, has the misfortune to be spared. The nearest hit is the submarine base at New London Connecticut, fifty miles south. Before they sign off, the emergency people on the radio and TV say it will be eight hours before the cloud reaches Springfield. Plenty of time, they predict, to evacuate north to Vermont where only one weapon, an errant one that failed to detonate, has dropped into a pasture.

It is six-twenty p.m.

Freddy is hungry. Freddy has a weight problem and he's almost always hungry. He strolls Merchants Mall rifling through the trash barrels, as is his wont, for something good to eat. Usually, he is rewarded — half a hot dog, a Chicken McNugget, the soggy bottom of Baskin-Robbins ice cream cone, his favorite treat — but today, the pickings are slim. He moves down the mall, working the barrels, humming a tune whose words he's never learned. In Angelo's Department store, the window-display TVs are still on, but only silver static fills the screens. On the street corners, the traffic lights continue through their cycles: red to green to yellow and back to red. Smoke curls from a small fire in the alley behind Burger King. It is quiet.

Freddy is alone.

Six or seven hours ago (or was it more? time is such an elusive concept), the mall was mobbed. When the announcement came, there was a moment of silence. You could see something new, something terrible, in the faces of the shoppers and bankers and secretaries on their lunchtime strolls. Like someone had died or the president had been shot. It didn't last, that strange silence. Soon there was screaming, and people running, and cars racing, and horns blaring, and then there was a traffic jam that didn't unclog.

When most everyone had gone, the looters moved in. Freddy found shelter in a doorway and watched. It was kind of funny, what they went after. Not the TVs or jewelry or even the money in the banks, as near as he could tell. Things like flashlights and battery-powered radios and cans of soda. Freddy even saw one guy with a bag of canned hams come tearing out of the deli. Freddy went to get one for himself, but by the time he got there, they were all gone, along with all the cheeses and bologna and chicken roll.

Today is Freddy's 42nd birthday.

This morning, with Mother's help, he dressed in his madras shorts and that green shirt with the alligator over the pocket that she gave him last Christmas. He put on white knee socks and sneakers and, lastly, his Red Sox cap. He's never been to Fenway Park, but you don't have to in order to get one of those caps. You can buy them right inside the sports department at Angelo's, and Freddy did, his last birthday, right after Mother's check came in. When he gets home tonight, she's going to have a special meal for him. Hot dogs, and potato salad, and chocolate ice cream with fudge sauce and whipped cream from a can for dessert.

He continues up the mall. Now and again, he looks at the sky. It is still cloudless. He doesn't know what the cloud they say's coming will look like: a normal fluffy white cloud, or maybe a dark cloud, like before the thunderstorm or the hurricane that September weekend a few years back. He doesn't know what will drop out of the cloud, if anything at all.

Freddy finds Rita at the fountain.

The water isn't squirting out today, but there's plenty left in the pool, and she's sitting next to it, her head cocked toward the sky, her sunglasses on. Cool. It's like she's getting a tan…

-- 30 --

READ “Freddy and Rita” in “The Big Book of NECON,” the 2009 collection edited by Bob Booth.

READ “Freddy and Rita” in “Since the Sky Blew Off: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction Vol. 1, Kindle Edition.”

THE ORIGINAL “NECON Stories.”

Context:

Another dystopian story, written as the Cold War had finally breathed its last, but not without the possibility of nuclear holocaust continuing. Those who lived through the tensions between the Soviet Union and the U.S. were affected in many ways – ways that, to one degree or another, continue – and have been resurrected with Kim Jong-un’s North Korea ballistic capabilities. Writers then and now worked these fears into their fiction. Stephen King, for example, in works including The Stand, which was a big influence on my own writing.

Which brings us to NECON, officially Camp NECON: The Northeastern Writers’ Conference, the annual gathering co-founded in 1980 by Mary Booth and the late Bob Booth (whose obituary I had the honor of writing for The Providence Journal).

King was an early attendee at NECON, back in the day, as the saying goes, when he was rising fast on the literary scene but not quite the best-selling master he became. I attended several NECONs in the mid and late ‘80s, with writers and artists including Gahan Wilson, Tom Monteleone, Elizabeth Massie, Kathryn Ptacek, Paul F. Olson, Peter Straub, Chet Williamson, Robert McCammon, David Wilson, Courtney Skinner, and the late Charles F. Grant and Les Daniels. Good times down there at Roger Williams University. Lasting friendships made.

I never met King at NECON, though his “The Old Dude’s Ticker,” written in the early 1970s but not sold at that time, was the story before “Freddy and Rita” in the “The Big Book of NECON.” I did, however, have the chance to meet King in New York, in 1986. He was granting interviews for Maximum Overdrive, the film he directed, in his suite in a hotel overlooking Central Park. What a thrill to meet him! I had been hooked on King since reading ‘Salem’s Lot – which, like much of his work, maybe all, has withstood the test of time.

Here’s that story:

KING OF HORROR His career's in 'Overdrive' as he directs his first film

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: August 3, 1986 Page: I-01 Section: ARTS Edition: ALL

STEPHEN KING, the most popular horror writer of all time, is eating pizza - thick, oily, mega-calorie pizza with all the fixings. He's eating it the way a big hungry kid would - ferociously and noisily. Stephen King loves pizza, just as he loves scaring the pants off people.

King, who has made enough money from what he calls his "marketable obsession" to buy Brooks Brothers' entire inventory, is dressed in jeans, work shirt, running shoes. Comfort is the thing for King, who sets many of his stories in rural Maine, the place he's lived most of his 38 years.

Would his visitor like a slice of that greasy monster masquerading as a pizza, he asks politely? No? Then have a seat. Feel at home.

He sits - flops is probably a better word - onto an oversized chair in his hotel suite. King is well over six feet tall, and his long legs seem to stretch halfway across this elegantly furnished sitting room. He brushes his black hair off his face, grins mischievously, and peers from behind thick glasses, his "Coke bottles," as he's referred to them.

"Whatever you want to talk about," he says in a voice that is a curious mix of Downeast twang and Ted Kennedy drone. "The film is what I'm supposed to talk about, so why don't we start with the film?"

Maximum Overdrive, King's first shot at directing, opened last weekend. It's about a group of people trapped by driverless vehicles in an isolated truck stop the week all the machines in the world go murderously beserk. Machines gone mad. It's a favorite King theme, and if one were to psychoanalyze it, the connection to modern man's uneasy coexistence with his nuclear genie would be hard to miss.

The obvious first question, of course, is why a one-time teacher who has parlayed a lifelong fascination with the macabre into a fairy-tale existence as best-selling author (70 million books in print) would want to trade his golden pen for a camera.

Certainly, King is no stranger to movies. He admits to being a horror-movie junkie growing up in the '50s and '60s; as an adult, he has written the screenplays for five films, including Overdrive. Eight of his full-length novels have been made into films of varying quality, and another four (including Pet Sematary, his most recent) are in various stages of production. On top of all that, several King short stories have been adapted for TV, and an unpublished novel has been sold for a mini-series.

So why direct?

"Curiosity," he says, continuing to gorge himself on pizza.

Actually, it wasn't simply curiosity that prompted King to accept movie mogul Dino De Laurentis's offer to direct.

Pleased with some

Although King is pleased with some film adaptations of his works - he thinks Cujo and The Dead Zone are great - he has been disappointed with others. In particular, Firestarter, Children of the Corn, and The Shining, directed by Stanley Kubrick, still make King cringe. (He once described Firestarter as "flavorless," like "cafeteria mashed potatoes.")

The disappointing films, King explains between bites, failed to capture the spirit of his written works - either they didn't frighten, or took implausible twists, or were blandly acted, or sloppily directed, whatever. With Overdrive, King finally wanted to see if he could capture that spirit on film. If he couldn't, well, at least he'd have no one but himself to blame.

"My son's got this wonderful imitation of Leonard Malton on Entertainment Tonight," King says, becoming suddenly animated.

"He'll start off the way he always starts off when he's going to give a really bad review. He'll say, 'This is Leonard Malton, Entertainment Tonight. Stephen King says that he wanted to direct a picture to see if whatever makes his books so successful could be translated to film if he did it himself.

" 'The answer is no]' "

King grins. "Actually," he continues, "the answer is yes. I think. I think it has a lot of appeal of the books."

Not that he's exactly rehearsing his Academy Award acceptance speech, as he notes wryly. Although the film does not look amateurish - for a rookie, King's grasp of cinematic technique is quite impressive - its human characters are undeveloped. And despite King's hopes, Overdrive only hints at his books' rich textures. It's hard to escape the conclusion that what King does so well in print probably can't be translated onto the silver screen.

"I think by and large this movie will get kind of a sour critical reception," he predicts. "It's a 'moron movie,' for one thing. It's crash and bash. It's a head-banger movie - really, really loud."

Promotional tour

Critics notwithstanding, King believes audiences will like Overdrive as much as he does. He hopes so, anyway. The only reason he agreed to do a nationwide promotional tour is to hype the film. Too many earlier King films, he laments, have lasted in theaters all of two weeks.

"Graham Greene said . . . writers write books they can't find on library shelves. To some extent, I think directors must direct movies that they can't go and watch in movie theaters.

"Overdrive is fun. I like movies where you can just, like, check your brains at the box office and pick 'em up two hours later. Sit and kind of let it flow over you and, you know, dig on it. This movie is just sort of gaudy blaaaaah. It's not a heavy social statement," he asserts.

Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth - he's got one hell of a set of incisors, one discovers. Normally a rational and intelligent human being, he's transformed himself into a raving lunatic.

He jumps up and screams: "One of the things I wanted was to never let up. My idea is that what you do is build up, like reaching out and grabbing somebody by the ----] Right out of the page if possible or right out of the screen] Tell you what, ------------, you're mine]]]]]]"

He sits down again, laughing like - like a kid.

Four new novels

To say that Stephen King is big is a little like saying Carrie, telekinetic murderess of his first novel, is odd.

Some noteworthy footnotes to the King saga:

* The initial hardcover printing of last year's Skeleton Crew, his second anthology, was one million copies, one of the largest first hardcover printings in publishing history.

* King books are hot collectors items. In May, for example, an uncorrected proof of his Night Shift collection brought $2,500 at a San Francisco auction. A small-press magazine in which one of his stories appeared years ago brought a cool $150.

* For a decade, King's books have consistently topped the best-seller lists. According to Publishers Weekly, his scorecard for 1985 included the fifth and 11th best-selling fiction hardcover books; the second, fourth and eight best-selling mass paperbacks; and the second and third best-selling trade paperbacks. Total sales of those seven books alone: 11.49 million.

* King has his own monthly newspaper, Castle Rock, published and edited by his secretary, Stephanie Leonard.

* Against the advice of his publisher, who's worried that the market will be saturated (King disagrees), King will release four new novels in the next year, including the 1,000-page-plus IT later this summer.

* A musical version of Carrie takes to Broadway this fall.

Not to mention all those movies.

This being America, money has come hand-in-hand with his fame. King is so rich that when someone threatened to buy his favorite radio station in Bangor, Maine, and replace its rock format with EZ Listening, he rushed out and bought it himself. Rumor has it he paid cash.

The unknowns remain

Naturally, there are secrets to King's success.

One - hardly the best-kept - is that people, millions of them, anyway, like to be scared. Late at night, with the wind moaning, the leaves on the trees rustling, the kids sleeping (are they still breathing?) and something downstairs making a strange noise (is it only the cat?), they love to curl up with a good scary book and let the chills crawl down their spines.

King has lectured and written extensively about fear. He understands that no matter how technologically advanced we become, no matter how much the scientists figure out about ourselves and our world, the great unknowns remain: darkness, death, whatever is beyond the grave.

Still, there are plenty of horror writers slogging away out there, including several who have won critical acclaim - such as Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho, and Peter Straub, author of the million-seller Ghost Story, and J.N. Williamson and Richard Matheson, two of the more prolific writers of the genre. Some are literary, closer to Poe than King; others are more gruesome, more skilled with plot. In terms of popularity, King has eclipsed them all.

The real secret is where King has taken horror - out of the Egyptian mummy's tomb and straight into the living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens of contemporary middle- and lower-class America. King's landscape is the America of kids and pets and Coke and malls and cheeseburgers and troubles with the mortgage payment and that old clunker, the family car - much the same vision of America that Steven Speilberg has brought to Hollywood.

Not that everything is ordinary in King's works. Whether haunted car or haunted child, King's villains and monsters and spirits are deeply troubling, frequently uncontrollable, and usually deadly. There's a lot of darkness in King's work, and plenty of ghosts. Death is never very far away.

It is precisely this juxtaposition - ordinary people victimized by extraordinary forces - that is the key to all good horror, not just King's.

Hitting the nerves

Still . . . 70 million books, 16 movies, a Broadway play, and no end in sight?

"Some of it," King explains as he polishes off lunch, "has got to be that I'm talking about things that, like you say, hit nerves. Or maybe they don't hit nerves - maybe they just resonate.

"You know, people say, 'I know about that, because that happened to me.' I don't mean an ability to light fires or anything like that (the heroine of Firestarter is a young girl with pyrotechnic powers), but something about family life, or something your kid said, something like that."

Not that King's intent is anthropological exposition; he is not a scholar, nor does he pretend to be. He bases his fiction on situations he understands because they've been his life, too - family, marriage, the battle (at least in the early days) for a buck. King and his wife, Tabitha, also an author, have three children. The eldest is 16.

"I don't write with an audience in mind. I mean, the audience is me. My popularity says something about my own mind. It's a little bit distressing when you think about it. It says, 'Well, here's a person who's so perfectly in tune with middle-cultural drone that there must be this incredible bowling alley echo inside his head.' "

Even King's detractors - there's no shortage of critics who dismiss his work as insignificant - concede that he has a true talent for depicting children. Maybe that's because King himself could well be the biggest kid in America. Even when they are blessed/cursed with supernatural powers, King's fictional children are flesh and blood - so seemingly real that you wonder if they don't actually exist somewhere, and King is only documenting their lives.

In fact, King's own children have had enormous impact, and if you doubt that, you only need look at his dedications.

"I grew up with them," he says. "Bringing up baby or child or children or whatever has been one of the experiences of my life, and so it's one of the things I write about. But also it's a way of trying to make sense of how the child you were yourself became the man that you are and that whole crazy business."

Woes with women

As good as King has been creating children, he has had his woes with women, as countless critics have been quick to point out.

"I've had such problems with women characters," he agrees, the smile leaving his face. "God knows I have tried. I tried with Donna Trenton in Cujo - tried to make a real woman. (I thought) she worked pretty well, except I got hit pretty hard by a lot of critics. An awful lot of critics said the dog is punishment for adultery.

"The death of her child . . . consciously, on top of my mind, I was simply trying to create a convincing chain of events that would put the boy and her in that position where they could spend a period of time. But when you think about it. . . .

"Yes, I've had trouble with women. It's funny because that's why I started to write Carrie. This friend of mine said to me, 'The trouble with you is you don't understand women.' I said, 'What do you mean?' It's like he'd accused me of being a virgin or something like that, which I just barely wasn't at that time.

"He says, 'Ah, all these stories with these hairy-chested horror things, these guys fighting monsters and stuff like that.' I was trying to tell him, 'You don't understand. That's what they buy, these men's magazines.' He said, 'You couldn't create a woman character if you tried. You know, a good one.' I said I bet I could. Carrie - that's a book about women, almost completely about women. There are almost no male characters in it."

Father ran off

By now, the story of King's climb to the top is legendary.

It begins with a kid growing up in Maine and (for four years) in Connecticut - a kid whose father ran off never to be heard from again, a kid whose mother raised him and his elder brother on a shoestring. On the outside, King was a polite child who liked cars, played some sports - but inside, he would later recall, he often felt unhappy, "different," even violent.

He remembers writing his first horror story at the age of seven; it was about dinosaurs on a rampage. Through his teens, he read voraciously, spent hours in movie theaters, kept on writing and writing and writing. It was while attending the University of Maine, Orono, that he began to sell short stories to magazines. But his novels, and there were several of them by this point, were going nowhere.

After college, he and his wife worked a succession of jobs to keep their family afloat: Tabitha as a waitress, he as a worker in a coin laundry and as an English teacher at a private school. The short stories kept selling - they were helping to pay the rent on the tiny trailer where they lived - but the novels were still moribund.

King wrote Carrie working late into the night in the furnace room of their trailer - the only available space in already cramped quarters. Somewhere, King says, they still have the Olivetti portable typewriter on which he banged out several early novels and stories.

The old portable

"There were no word processors then," King remembers. "I used my wife's portable. She stills says sometimes - in jest, I think - 'My husband married me for my portable typewriter.' It's got my fingerprints carved into the keys. I mean, I beat that thing to death just about.

"I used to have to bring Joe in in his crib to where I worked, which was the furnace room. You'd get hot and you'd be going along good and he'd wake up and you'd have to give him a bottle because he'd cried. It was just, you know, you get it done the best you can.

"You don't raise your head and look around, because if you do you just get depressed. And I was depressed then. Because I was selling some short stories, but I had had like three, four novels bounced back at me at that time and also a number of other short stories."

Even after finally selling Carrie to Doubleday, the struggle continued.

"My wife used to work at 'Drunken' Donuts,' which is what they called it on the night shift. I used to take care of the kids while I did the rewrite. This was after the contract and everything, but before we had any money. I mean, the contract was only for $2,500. It wasn't exactly a king's ransom," he says, seemingly unaware of the pun.

The big break came with the paperback contract for Carrie, which had done reasonably well in hardcover. King had expected to earn $5,000 to $12,000 on the paperback rights. When his editor called to tell him that the sale had been for $400,000, virtually unprecedented at the time for a newcomer, he was flabbergasted.

He celebrated by buying the thing he thought his wife would like the most - a $29 hair dryer.

'Normal' life in Maine

It seems a lifetime ago, those early days.

Today, King and his family live in a large Victorian house in Bangor. He has a summer home on a Maine lake, drives a Mercedes, is a Red Sox fan, loves beer as much as pizza, enjoys tennis and softball, usually wears a beard in winter. Except when he's on tour, he writes every day of the year, except Christmas, the Fourth of July and his birthday. He does the family shopping. His children attend public schools.

"They don't have any sense that there's anything really odd about what I do because I've never made out like I'm a big shot because I don't feel that I am. Also, we don't live in New York or California, where they might live in an atmosphere that's a little stranger. They seem pretty normal."

Although he is Bangor's most famous citizen - arguably Maine's, as well - the natives, he says, "mostly leave me alone. I have the town broken in. I guess familiarity breeds contempt."

Not that he hasn't become something of a celebrity for the tourists - a class of citizen he has often lampooned in his written works.

"Oh, sure," he says. "They have Canadian tour buses that come down to go to the mall - the Bangor Mall, which is the closest real big super mall to Nova Scotia. One of the things they throw in with this is you get to go by the 'Stephen King House,' like you're stuffed and embalmed. You're in there and one day you look out and you see this huge bus with 150 Canadians lined up along the fence snapping pictures. It's very odd."

Next interview

A TV crew has arrived early to set up for King's next interview. "Let's go into the bedroom," he suggests. "It's quieter." He gets up, crosses the room and closes the door behind him. Stretching full-length on his unmade bed, he props himself up on his elbows and resumes talking about his film.

Overdrive is based on "Trucks," one of several brilliant short stories in his first anthology, Night Shift.

"It's always been my favorite from that collection," he says. "Trucks I liked just for the feel of it. It had a desperate film noir quality as a story."

Machines gone mad. In Overdrive, which will be remembered more for its special effects and pyrotechnics than its acting or social significance, they go one step further: They try to take over the world. Knives, soda machines, video games, lawnmowers, a drawbridge, cars, 18-wheelers - all become killers.

"I'm fascinated by (machines)," King says enthusiastically. "They scare me. There's so much potential for destruction. In the film there's a track shot that starts on this hammock that's empty and swinging. In the background you see a guy who's obviously had his head cut off by his own chainsaw. The chainsaw is buried somewhere in his neck.

"There's a little Watchman with a little teeny screen giving this information about machines having gone beserk. The camera pans down and tracks and you see an overturned Styrofoam cooler and then you see empty beer bottles and then you see the Watchman. It doesn't have a picture on it but it's splattered with blood.

"Then you see the guy and you track up his body and he's all been shredded because he's been, you know, 'lawn-mowered' to death. You come to the lawnmower itself and it's all covered with blood and everything. When it finally runs, it chases this kid. It's quite funny."

He chuckles, then pauses. "Well to me, it's funny," he explains. "A lot of people are going to say it's gross and gratuitous. That's OK."

Machines and actors

King chose Overdrive for his directorial debut because he thought it would be easier to work with special effects and machines rather than with real-life actors.

It turned out to be the other way around.

"I thought to myself: 'My electric knife is never going to say, 'I can't cut the actress's arm today because my hairdresser didn't come in from New York.' My truck is never going to say, 'I can't run by myself today because I'm having my period.' You know what I mean?

"I went into the thing with a lot of the stereotyped ideas that people get about actors. You know, 'They're a bunch of conceited snobs. They're all babyish, you have to baby them along, you have to always be feeding them constant praise, they're always difficult to work with,' all this stuff.

"It turned out all to be b-------. They all worked really hard. They gave me more than 150 percent. They were almost always at their best.

"The actors were great, but all the machines . . . they wouldn't run. The trucks wouldn't start. We crashed four vehicles that were supposed to roll over before one finally did, and that was only on the third take. We had problems with the power mower. It was radio-controlled. Back at the studio, it went like a bat out of hell. Get it on location, it would just sit there.

"The electric knife that goes beserk . . . skittering along the floor like a big bug. The special-effects guys built three knives using dildo motors - basically vibrator motors to make them work. Two of them got wrecked on bad takes and we only had one left and we had to get it right. Luckily we did."

What scares him

The TV people are ready and time is almost up.

A few questions remain.

What scares you?

"Just about everything, in one way or another," he says. "But I think the thing that scares me most would be to check on one of my kids one night and find him dead in bed."

Did you ever expect to sell 70 million books?

"I don't even know what that figure means," he says, as if still finding it impossible to believe. "Do you realize if I live along enough there could be as many copies of my stuff actually sold as there are people in the country?"

No, King never expected all this - not even in his wildest dreams.

Are you afraid that someday it'll all be gone?

"Yeah," he laughs, starting to act out a scene from a movie where an enormously fat man explodes after a gargantuan meal. "Someday I'll just burst like that guy in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life. Did you see that? 'Just one more mint.' 'Nah, I'll burst'. . . and he did."

No. 6: “Freddy and Rita”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Originally published in NECON stories, 1990, Three Bobs Press, Providence, R.I.

pp. 40 – 41 of “Freddy and Rita”:

The missiles fall at noon on a perfect August day. New York, Washington, Houston, Los Angeles –– all gone, instantly. Springfield, Massachusetts, a small city west of Boston, has the misfortune to be spared. The nearest hit is the submarine base at New London Connecticut, fifty miles south. Before they sign off, the emergency people on the radio and TV say it will be eight hours before the cloud reaches Springfield. Plenty of time, they predict, to evacuate north to Vermont where only one weapon, an errant one that failed to detonate, has dropped into a pasture.

It is six-twenty p.m.

Freddy is hungry. Freddy has a weight problem and he's almost always hungry. He strolls Merchants Mall rifling through the trash barrels, as is his wont, for something good to eat. Usually, he is rewarded — half a hot dog, a Chicken McNugget, the soggy bottom of Baskin-Robbins ice cream cone, his favorite treat — but today, the pickings are slim. He moves down the mall, working the barrels, humming a tune whose words he's never learned. In Angelo's Department store, the window-display TVs are still on, but only silver static fills the screens. On the street corners, the traffic lights continue through their cycles: red to green to yellow and back to red. Smoke curls from a small fire in the alley behind Burger King. It is quiet.

Freddy is alone.

Six or seven hours ago (or was it more? time is such an elusive concept), the mall was mobbed. When the announcement came, there was a moment of silence. You could see something new, something terrible, in the faces of the shoppers and bankers and secretaries on their lunchtime strolls. Like someone had died or the president had been shot. It didn't last, that strange silence. Soon there was screaming, and people running, and cars racing, and horns blaring, and then there was a traffic jam that didn't unclog.

When most everyone had gone, the looters moved in. Freddy found shelter in a doorway and watched. It was kind of funny, what they went after. Not the TVs or jewelry or even the money in the banks, as near as he could tell. Things like flashlights and battery-powered radios and cans of soda. Freddy even saw one guy with a bag of canned hams come tearing out of the deli. Freddy went to get one for himself, but by the time he got there, they were all gone, along with all the cheeses and bologna and chicken roll.

Today is Freddy's 42nd birthday.

This morning, with Mother's help, he dressed in his madras shorts and that green shirt with the alligator over the pocket that she gave him last Christmas. He put on white knee socks and sneakers and, lastly, his Red Sox cap. He's never been to Fenway Park, but you don't have to in order to get one of those caps. You can buy them right inside the sports department at Angelo's, and Freddy did, his last birthday, right after Mother's check came in. When he gets home tonight, she's going to have a special meal for him. Hot dogs, and potato salad, and chocolate ice cream with fudge sauce and whipped cream from a can for dessert.

He continues up the mall. Now and again, he looks at the sky. It is still cloudless. He doesn't know what the cloud they say's coming will look like: a normal fluffy white cloud, or maybe a dark cloud, like before the thunderstorm or the hurricane that September weekend a few years back. He doesn't know what will drop out of the cloud, if anything at all.

Freddy finds Rita at the fountain.

The water isn't squirting out today, but there's plenty left in the pool, and she's sitting next to it, her head cocked toward the sky, her sunglasses on. Cool. It's like she's getting a tan…

-- 30 --

READ “Freddy and Rita” in “The Big Book of NECON,” the 2009 collection edited by Bob Booth.

READ “Freddy and Rita” in “Since the Sky Blew Off: The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction Vol. 1, Kindle Edition.”

THE ORIGINAL “NECON Stories.”

Context:

Another dystopian story, written as the Cold War had finally breathed its last, but not without the possibility of nuclear holocaust continuing. Those who lived through the tensions between the Soviet Union and the U.S. were affected in many ways – ways that, to one degree or another, continue – and have been resurrected with Kim Jong-un’s North Korea ballistic capabilities. Writers then and now worked these fears into their fiction. Stephen King, for example, in works including The Stand, which was a big influence on my own writing.

Which brings us to NECON, officially Camp NECON: The Northeastern Writers’ Conference, the annual gathering co-founded in 1980 by Mary Booth and the late Bob Booth (whose obituary I had the honor of writing for The Providence Journal).

King was an early attendee at NECON, back in the day, as the saying goes, when he was rising fast on the literary scene but not quite the best-selling master he became. I attended several NECONs in the mid and late ‘80s, with writers and artists including Gahan Wilson, Tom Monteleone, Elizabeth Massie, Kathryn Ptacek, Paul F. Olson, Peter Straub, Chet Williamson, Robert McCammon, David Wilson, Courtney Skinner, and the late Charles F. Grant and Les Daniels. Good times down there at Roger Williams University. Lasting friendships made.

I never met King at NECON, though his “The Old Dude’s Ticker,” written in the early 1970s but not sold at that time, was the story before “Freddy and Rita” in the “The Big Book of NECON.” I did, however, have the chance to meet King in New York, in 1986. He was granting interviews for Maximum Overdrive, the film he directed, in his suite in a hotel overlooking Central Park. What a thrill to meet him! I had been hooked on King since reading ‘Salem’s Lot – which, like much of his work, maybe all, has withstood the test of time.

Here’s that story:

KING OF HORROR His career's in 'Overdrive' as he directs his first film

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: August 3, 1986 Page: I-01 Section: ARTS Edition: ALL

STEPHEN KING, the most popular horror writer of all time, is eating pizza - thick, oily, mega-calorie pizza with all the fixings. He's eating it the way a big hungry kid would - ferociously and noisily. Stephen King loves pizza, just as he loves scaring the pants off people.

King, who has made enough money from what he calls his "marketable obsession" to buy Brooks Brothers' entire inventory, is dressed in jeans, work shirt, running shoes. Comfort is the thing for King, who sets many of his stories in rural Maine, the place he's lived most of his 38 years.

Would his visitor like a slice of that greasy monster masquerading as a pizza, he asks politely? No? Then have a seat. Feel at home.

He sits - flops is probably a better word - onto an oversized chair in his hotel suite. King is well over six feet tall, and his long legs seem to stretch halfway across this elegantly furnished sitting room. He brushes his black hair off his face, grins mischievously, and peers from behind thick glasses, his "Coke bottles," as he's referred to them.

"Whatever you want to talk about," he says in a voice that is a curious mix of Downeast twang and Ted Kennedy drone. "The film is what I'm supposed to talk about, so why don't we start with the film?"

Maximum Overdrive, King's first shot at directing, opened last weekend. It's about a group of people trapped by driverless vehicles in an isolated truck stop the week all the machines in the world go murderously beserk. Machines gone mad. It's a favorite King theme, and if one were to psychoanalyze it, the connection to modern man's uneasy coexistence with his nuclear genie would be hard to miss.

The obvious first question, of course, is why a one-time teacher who has parlayed a lifelong fascination with the macabre into a fairy-tale existence as best-selling author (70 million books in print) would want to trade his golden pen for a camera.

Certainly, King is no stranger to movies. He admits to being a horror-movie junkie growing up in the '50s and '60s; as an adult, he has written the screenplays for five films, including Overdrive. Eight of his full-length novels have been made into films of varying quality, and another four (including Pet Sematary, his most recent) are in various stages of production. On top of all that, several King short stories have been adapted for TV, and an unpublished novel has been sold for a mini-series.

So why direct?

"Curiosity," he says, continuing to gorge himself on pizza.

Actually, it wasn't simply curiosity that prompted King to accept movie mogul Dino De Laurentis's offer to direct.

Pleased with some

Although King is pleased with some film adaptations of his works - he thinks Cujo and The Dead Zone are great - he has been disappointed with others. In particular, Firestarter, Children of the Corn, and The Shining, directed by Stanley Kubrick, still make King cringe. (He once described Firestarter as "flavorless," like "cafeteria mashed potatoes.")

The disappointing films, King explains between bites, failed to capture the spirit of his written works - either they didn't frighten, or took implausible twists, or were blandly acted, or sloppily directed, whatever. With Overdrive, King finally wanted to see if he could capture that spirit on film. If he couldn't, well, at least he'd have no one but himself to blame.

"My son's got this wonderful imitation of Leonard Malton on Entertainment Tonight," King says, becoming suddenly animated.

"He'll start off the way he always starts off when he's going to give a really bad review. He'll say, 'This is Leonard Malton, Entertainment Tonight. Stephen King says that he wanted to direct a picture to see if whatever makes his books so successful could be translated to film if he did it himself.

" 'The answer is no]' "

King grins. "Actually," he continues, "the answer is yes. I think. I think it has a lot of appeal of the books."

Not that he's exactly rehearsing his Academy Award acceptance speech, as he notes wryly. Although the film does not look amateurish - for a rookie, King's grasp of cinematic technique is quite impressive - its human characters are undeveloped. And despite King's hopes, Overdrive only hints at his books' rich textures. It's hard to escape the conclusion that what King does so well in print probably can't be translated onto the silver screen.

"I think by and large this movie will get kind of a sour critical reception," he predicts. "It's a 'moron movie,' for one thing. It's crash and bash. It's a head-banger movie - really, really loud."

Promotional tour

Critics notwithstanding, King believes audiences will like Overdrive as much as he does. He hopes so, anyway. The only reason he agreed to do a nationwide promotional tour is to hype the film. Too many earlier King films, he laments, have lasted in theaters all of two weeks.

"Graham Greene said . . . writers write books they can't find on library shelves. To some extent, I think directors must direct movies that they can't go and watch in movie theaters.

"Overdrive is fun. I like movies where you can just, like, check your brains at the box office and pick 'em up two hours later. Sit and kind of let it flow over you and, you know, dig on it. This movie is just sort of gaudy blaaaaah. It's not a heavy social statement," he asserts.

Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth - he's got one hell of a set of incisors, one discovers. Normally a rational and intelligent human being, he's transformed himself into a raving lunatic.

He jumps up and screams: "One of the things I wanted was to never let up. My idea is that what you do is build up, like reaching out and grabbing somebody by the ----] Right out of the page if possible or right out of the screen] Tell you what, ------------, you're mine]]]]]]"

He sits down again, laughing like - like a kid.

Four new novels

To say that Stephen King is big is a little like saying Carrie, telekinetic murderess of his first novel, is odd.

Some noteworthy footnotes to the King saga:

* The initial hardcover printing of last year's Skeleton Crew, his second anthology, was one million copies, one of the largest first hardcover printings in publishing history.

* King books are hot collectors items. In May, for example, an uncorrected proof of his Night Shift collection brought $2,500 at a San Francisco auction. A small-press magazine in which one of his stories appeared years ago brought a cool $150.

* For a decade, King's books have consistently topped the best-seller lists. According to Publishers Weekly, his scorecard for 1985 included the fifth and 11th best-selling fiction hardcover books; the second, fourth and eight best-selling mass paperbacks; and the second and third best-selling trade paperbacks. Total sales of those seven books alone: 11.49 million.

* King has his own monthly newspaper, Castle Rock, published and edited by his secretary, Stephanie Leonard.

* Against the advice of his publisher, who's worried that the market will be saturated (King disagrees), King will release four new novels in the next year, including the 1,000-page-plus IT later this summer.

* A musical version of Carrie takes to Broadway this fall.

Not to mention all those movies.

This being America, money has come hand-in-hand with his fame. King is so rich that when someone threatened to buy his favorite radio station in Bangor, Maine, and replace its rock format with EZ Listening, he rushed out and bought it himself. Rumor has it he paid cash.

The unknowns remain

Naturally, there are secrets to King's success.

One - hardly the best-kept - is that people, millions of them, anyway, like to be scared. Late at night, with the wind moaning, the leaves on the trees rustling, the kids sleeping (are they still breathing?) and something downstairs making a strange noise (is it only the cat?), they love to curl up with a good scary book and let the chills crawl down their spines.

King has lectured and written extensively about fear. He understands that no matter how technologically advanced we become, no matter how much the scientists figure out about ourselves and our world, the great unknowns remain: darkness, death, whatever is beyond the grave.

Still, there are plenty of horror writers slogging away out there, including several who have won critical acclaim - such as Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho, and Peter Straub, author of the million-seller Ghost Story, and J.N. Williamson and Richard Matheson, two of the more prolific writers of the genre. Some are literary, closer to Poe than King; others are more gruesome, more skilled with plot. In terms of popularity, King has eclipsed them all.

The real secret is where King has taken horror - out of the Egyptian mummy's tomb and straight into the living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens of contemporary middle- and lower-class America. King's landscape is the America of kids and pets and Coke and malls and cheeseburgers and troubles with the mortgage payment and that old clunker, the family car - much the same vision of America that Steven Speilberg has brought to Hollywood.

Not that everything is ordinary in King's works. Whether haunted car or haunted child, King's villains and monsters and spirits are deeply troubling, frequently uncontrollable, and usually deadly. There's a lot of darkness in King's work, and plenty of ghosts. Death is never very far away.

It is precisely this juxtaposition - ordinary people victimized by extraordinary forces - that is the key to all good horror, not just King's.

Hitting the nerves

Still . . . 70 million books, 16 movies, a Broadway play, and no end in sight?

"Some of it," King explains as he polishes off lunch, "has got to be that I'm talking about things that, like you say, hit nerves. Or maybe they don't hit nerves - maybe they just resonate.

"You know, people say, 'I know about that, because that happened to me.' I don't mean an ability to light fires or anything like that (the heroine of Firestarter is a young girl with pyrotechnic powers), but something about family life, or something your kid said, something like that."

Not that King's intent is anthropological exposition; he is not a scholar, nor does he pretend to be. He bases his fiction on situations he understands because they've been his life, too - family, marriage, the battle (at least in the early days) for a buck. King and his wife, Tabitha, also an author, have three children. The eldest is 16.

"I don't write with an audience in mind. I mean, the audience is me. My popularity says something about my own mind. It's a little bit distressing when you think about it. It says, 'Well, here's a person who's so perfectly in tune with middle-cultural drone that there must be this incredible bowling alley echo inside his head.' "

Even King's detractors - there's no shortage of critics who dismiss his work as insignificant - concede that he has a true talent for depicting children. Maybe that's because King himself could well be the biggest kid in America. Even when they are blessed/cursed with supernatural powers, King's fictional children are flesh and blood - so seemingly real that you wonder if they don't actually exist somewhere, and King is only documenting their lives.

In fact, King's own children have had enormous impact, and if you doubt that, you only need look at his dedications.

"I grew up with them," he says. "Bringing up baby or child or children or whatever has been one of the experiences of my life, and so it's one of the things I write about. But also it's a way of trying to make sense of how the child you were yourself became the man that you are and that whole crazy business."

Woes with women

As good as King has been creating children, he has had his woes with women, as countless critics have been quick to point out.

"I've had such problems with women characters," he agrees, the smile leaving his face. "God knows I have tried. I tried with Donna Trenton in Cujo - tried to make a real woman. (I thought) she worked pretty well, except I got hit pretty hard by a lot of critics. An awful lot of critics said the dog is punishment for adultery.

"The death of her child . . . consciously, on top of my mind, I was simply trying to create a convincing chain of events that would put the boy and her in that position where they could spend a period of time. But when you think about it. . . .

"Yes, I've had trouble with women. It's funny because that's why I started to write Carrie. This friend of mine said to me, 'The trouble with you is you don't understand women.' I said, 'What do you mean?' It's like he'd accused me of being a virgin or something like that, which I just barely wasn't at that time.

"He says, 'Ah, all these stories with these hairy-chested horror things, these guys fighting monsters and stuff like that.' I was trying to tell him, 'You don't understand. That's what they buy, these men's magazines.' He said, 'You couldn't create a woman character if you tried. You know, a good one.' I said I bet I could. Carrie - that's a book about women, almost completely about women. There are almost no male characters in it."

Father ran off

By now, the story of King's climb to the top is legendary.

It begins with a kid growing up in Maine and (for four years) in Connecticut - a kid whose father ran off never to be heard from again, a kid whose mother raised him and his elder brother on a shoestring. On the outside, King was a polite child who liked cars, played some sports - but inside, he would later recall, he often felt unhappy, "different," even violent.

He remembers writing his first horror story at the age of seven; it was about dinosaurs on a rampage. Through his teens, he read voraciously, spent hours in movie theaters, kept on writing and writing and writing. It was while attending the University of Maine, Orono, that he began to sell short stories to magazines. But his novels, and there were several of them by this point, were going nowhere.

After college, he and his wife worked a succession of jobs to keep their family afloat: Tabitha as a waitress, he as a worker in a coin laundry and as an English teacher at a private school. The short stories kept selling - they were helping to pay the rent on the tiny trailer where they lived - but the novels were still moribund.

King wrote Carrie working late into the night in the furnace room of their trailer - the only available space in already cramped quarters. Somewhere, King says, they still have the Olivetti portable typewriter on which he banged out several early novels and stories.

The old portable

"There were no word processors then," King remembers. "I used my wife's portable. She stills says sometimes - in jest, I think - 'My husband married me for my portable typewriter.' It's got my fingerprints carved into the keys. I mean, I beat that thing to death just about.

"I used to have to bring Joe in in his crib to where I worked, which was the furnace room. You'd get hot and you'd be going along good and he'd wake up and you'd have to give him a bottle because he'd cried. It was just, you know, you get it done the best you can.

"You don't raise your head and look around, because if you do you just get depressed. And I was depressed then. Because I was selling some short stories, but I had had like three, four novels bounced back at me at that time and also a number of other short stories."

Even after finally selling Carrie to Doubleday, the struggle continued.

"My wife used to work at 'Drunken' Donuts,' which is what they called it on the night shift. I used to take care of the kids while I did the rewrite. This was after the contract and everything, but before we had any money. I mean, the contract was only for $2,500. It wasn't exactly a king's ransom," he says, seemingly unaware of the pun.

The big break came with the paperback contract for Carrie, which had done reasonably well in hardcover. King had expected to earn $5,000 to $12,000 on the paperback rights. When his editor called to tell him that the sale had been for $400,000, virtually unprecedented at the time for a newcomer, he was flabbergasted.

He celebrated by buying the thing he thought his wife would like the most - a $29 hair dryer.

'Normal' life in Maine

It seems a lifetime ago, those early days.

Today, King and his family live in a large Victorian house in Bangor. He has a summer home on a Maine lake, drives a Mercedes, is a Red Sox fan, loves beer as much as pizza, enjoys tennis and softball, usually wears a beard in winter. Except when he's on tour, he writes every day of the year, except Christmas, the Fourth of July and his birthday. He does the family shopping. His children attend public schools.

"They don't have any sense that there's anything really odd about what I do because I've never made out like I'm a big shot because I don't feel that I am. Also, we don't live in New York or California, where they might live in an atmosphere that's a little stranger. They seem pretty normal."

Although he is Bangor's most famous citizen - arguably Maine's, as well - the natives, he says, "mostly leave me alone. I have the town broken in. I guess familiarity breeds contempt."

Not that he hasn't become something of a celebrity for the tourists - a class of citizen he has often lampooned in his written works.