G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 18

April 26, 2018

Jim Ludes on the Pell Prize and Story in the Public Square

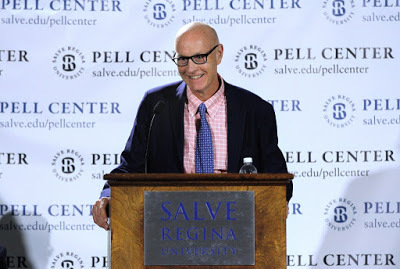

Pell Center director Jim Ludes begins the ceremony honoring Pulitzer winner and twice Pulitzer finalist Dan Barry with the sixth-annual Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square April 23, 2018, in Newport, Rhode Island.

Dan's eloquent address in accepting the honor can be read here, and my introduction of Dan here.

Wayne Miller, Dan Barry and Jim Ludes.

Wayne Miller, Dan Barry and Jim Ludes.

Good evening, Ladies and Gentlemen. Friends, my name is Jim Ludes and I’m the Vice President for Public Research and Initiatives here at Salve Regina University, as well as Executive Director of the Pell Center, and it is my distinct privilege and honor to welcome all of you to campus for the presentation of the 2018 Pell Center Prize.

Before we begin, there are a handful of special guests I want to take a moment to acknowledge.

• Sister Jane Gerety, the President of Salve Regina University.

• Janet Robinson, the Chair of Salve’s Board of Trustees, and the former President and CEO of the New York Times Company.

Thank you both for being here and for your tremendous support of the Pell Center and “Story in the Public Square,” in particular.

I also want to acknowledge:

• Janet Hasson, the publisher of the Providence Journal.

• Alan Rosenberg, the executive editor of the Journal.

Tonight is the sixth anniversary of the remarkable relationship between the Pell Center at Salve and the Journal in the form of “Story in the Public Square.” Thank you for your continued support for what we’re trying to do here.

And I do want to also take a moment to recognize

• His Excellency Thomas J. Tobin, Bishop of Providence.

• Tom Heslin, a former executive editor of the Journal who worked with tonight’s honoree earlier in his career.

Thank you both for joining us.

I know that no one came to tonight’s event to hear from me, so I’m not going to be very long, but I do want to say a few brief words about Story in the Public Square and share with you some exciting news.

A little more than six years ago, my friend and partner in this enterprise, G. Wayne Miller, and I met for coffee in downtown Newport. Wayne had just finished his biography of Senator Claiborne Pell, the launch of which we had hosted here at the Pell Center, and Wayne wanted to know if there was more we could do together.

“What do you have in mind?” I asked.

“Something about storytelling,” he said.

I scrunched up my nose. “I was thinking about something political,” I replied.

And over the following hour we achieved a compromise that I think Senator Pell would have admired. We would create a project on the role storytelling plays in public life.

In retrospect, it seems like a blinding flash of the obvious. Storytelling plays a central role in the politics of this country—even more so than sober analysis and facts. That’s not a recent phenomenon, you can think of the first American patriots in Boston as gifted storytellers—propagandists, even—whose depiction of the “Boston Massacre,” for example, was substantially different from the way the event actually unfolded.

That’s not to pass judgment on the rightness of any cause—but it is to acknowledge that stories big and small have long shaped the way Americans think about important issues. Lincoln referred to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin as “the book that caused this great war,” referring to the American Civil War. From the temperance movement to the political warfare of the Cold War, the civil rights movement, the Iraq War, and today’s era of so-called “Fake News,” narratives told by leaders, journalists, and citizens of all stripes, in print, in broadcast, in social media, or sitting in a diner with friends shape our understanding of issues and define the boundaries within which policy makers and political leaders can act.

Our goal in Story in the Public Square is to unpack those stories, to shine a light into some dark places so that we better understand the motive and the intent behind the stories that dominate American public life. We hope that the public that is exposed to our research and our programming begins to ask these questions themselves.

We’re doing a lot of work at the Pell Center, more broadly, on the issue of foreign disinformation and the threat to democracy. Some analysts will tell you information has been weaponized in the last several years. I will take it one step further: narrative—meaning story in all its forms—delivered by microtargeted social media has been weaponized. In a very real sense, we are talking about precision guided munition of the mind that threaten democracy.

Our hope as a democratic republic that values free speech and a free press is a critical thinking citizenry that can understand and dissect the stories they are being told. If you believe as I do that “democracy is a race between education and disaster,” then Story in the Public Square is firmly on the side of education and democracy.

Six years after that coffee-shop meeting—after a couple of successful conferences that validated our central insight; after presenting the Pell Center prize to a really dazzling assortment of storytellers:

• Pulitzer Prize Winning journalist Dana Priest of the Washington Post;

• Emmy-winning screenwriter Danny Strong;

• Best-selling author Lisa Genova;

• Pulitzer Prize winning photographer Javier Manzano;

• Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker Daphne Matziaraki.

And then having taken a crash-course in television production—Wayne and I were thrilled, fifteen months ago, to debut “Story in the Public Square,” as a weekly public affairs show where we like to say “storytelling meets public affairs.” The show launched on Rhode Island PBS and nationally on SiriusXM satellite radio’s Politics of the United States—that’s the POTUS Channel, number 124. Our mission is still the same—we want more and more people to understand that we are bombarded by stories every day, some of them are truthful. Some of them are not. But all shape our understanding of the world around us and the actions we take as citizens and, collectively, as a democratic society.

And so, now, some news. It is with particular hope about the impact of our work, that Wayne and I announce to you that Story in the Public Square, the half-hour public affairs program that began right here in Rhode Island, has gained a national television distributor and will be available to PBS stations across the United States later this year.

That’s not the end of our journey. Much work still needs to be done. But it’s a milestone and one that would not have happened without the support and encouragement of so many people in this room. On behalf of Wayne and I, we thank you, and hope you’ll stay tuned for what comes next.

Now, please join me in welcoming my collaborator and co-host to the stage, ladies and gentlemen, G. Wayne Miller.

Dan's eloquent address in accepting the honor can be read here, and my introduction of Dan here.

Wayne Miller, Dan Barry and Jim Ludes.

Wayne Miller, Dan Barry and Jim Ludes.Good evening, Ladies and Gentlemen. Friends, my name is Jim Ludes and I’m the Vice President for Public Research and Initiatives here at Salve Regina University, as well as Executive Director of the Pell Center, and it is my distinct privilege and honor to welcome all of you to campus for the presentation of the 2018 Pell Center Prize.

Before we begin, there are a handful of special guests I want to take a moment to acknowledge.

• Sister Jane Gerety, the President of Salve Regina University.

• Janet Robinson, the Chair of Salve’s Board of Trustees, and the former President and CEO of the New York Times Company.

Thank you both for being here and for your tremendous support of the Pell Center and “Story in the Public Square,” in particular.

I also want to acknowledge:

• Janet Hasson, the publisher of the Providence Journal.

• Alan Rosenberg, the executive editor of the Journal.

Tonight is the sixth anniversary of the remarkable relationship between the Pell Center at Salve and the Journal in the form of “Story in the Public Square.” Thank you for your continued support for what we’re trying to do here.

And I do want to also take a moment to recognize

• His Excellency Thomas J. Tobin, Bishop of Providence.

• Tom Heslin, a former executive editor of the Journal who worked with tonight’s honoree earlier in his career.

Thank you both for joining us.

I know that no one came to tonight’s event to hear from me, so I’m not going to be very long, but I do want to say a few brief words about Story in the Public Square and share with you some exciting news.

A little more than six years ago, my friend and partner in this enterprise, G. Wayne Miller, and I met for coffee in downtown Newport. Wayne had just finished his biography of Senator Claiborne Pell, the launch of which we had hosted here at the Pell Center, and Wayne wanted to know if there was more we could do together.

“What do you have in mind?” I asked.

“Something about storytelling,” he said.

I scrunched up my nose. “I was thinking about something political,” I replied.

And over the following hour we achieved a compromise that I think Senator Pell would have admired. We would create a project on the role storytelling plays in public life.

In retrospect, it seems like a blinding flash of the obvious. Storytelling plays a central role in the politics of this country—even more so than sober analysis and facts. That’s not a recent phenomenon, you can think of the first American patriots in Boston as gifted storytellers—propagandists, even—whose depiction of the “Boston Massacre,” for example, was substantially different from the way the event actually unfolded.

That’s not to pass judgment on the rightness of any cause—but it is to acknowledge that stories big and small have long shaped the way Americans think about important issues. Lincoln referred to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin as “the book that caused this great war,” referring to the American Civil War. From the temperance movement to the political warfare of the Cold War, the civil rights movement, the Iraq War, and today’s era of so-called “Fake News,” narratives told by leaders, journalists, and citizens of all stripes, in print, in broadcast, in social media, or sitting in a diner with friends shape our understanding of issues and define the boundaries within which policy makers and political leaders can act.

Our goal in Story in the Public Square is to unpack those stories, to shine a light into some dark places so that we better understand the motive and the intent behind the stories that dominate American public life. We hope that the public that is exposed to our research and our programming begins to ask these questions themselves.

We’re doing a lot of work at the Pell Center, more broadly, on the issue of foreign disinformation and the threat to democracy. Some analysts will tell you information has been weaponized in the last several years. I will take it one step further: narrative—meaning story in all its forms—delivered by microtargeted social media has been weaponized. In a very real sense, we are talking about precision guided munition of the mind that threaten democracy.

Our hope as a democratic republic that values free speech and a free press is a critical thinking citizenry that can understand and dissect the stories they are being told. If you believe as I do that “democracy is a race between education and disaster,” then Story in the Public Square is firmly on the side of education and democracy.

Six years after that coffee-shop meeting—after a couple of successful conferences that validated our central insight; after presenting the Pell Center prize to a really dazzling assortment of storytellers:

• Pulitzer Prize Winning journalist Dana Priest of the Washington Post;

• Emmy-winning screenwriter Danny Strong;

• Best-selling author Lisa Genova;

• Pulitzer Prize winning photographer Javier Manzano;

• Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker Daphne Matziaraki.

And then having taken a crash-course in television production—Wayne and I were thrilled, fifteen months ago, to debut “Story in the Public Square,” as a weekly public affairs show where we like to say “storytelling meets public affairs.” The show launched on Rhode Island PBS and nationally on SiriusXM satellite radio’s Politics of the United States—that’s the POTUS Channel, number 124. Our mission is still the same—we want more and more people to understand that we are bombarded by stories every day, some of them are truthful. Some of them are not. But all shape our understanding of the world around us and the actions we take as citizens and, collectively, as a democratic society.

And so, now, some news. It is with particular hope about the impact of our work, that Wayne and I announce to you that Story in the Public Square, the half-hour public affairs program that began right here in Rhode Island, has gained a national television distributor and will be available to PBS stations across the United States later this year.

That’s not the end of our journey. Much work still needs to be done. But it’s a milestone and one that would not have happened without the support and encouragement of so many people in this room. On behalf of Wayne and I, we thank you, and hope you’ll stay tuned for what comes next.

Now, please join me in welcoming my collaborator and co-host to the stage, ladies and gentlemen, G. Wayne Miller.

Published on April 26, 2018 03:13

April 24, 2018

Ode to Dan Barry

My remarks introducing author, New York Times staff writer, and Pulitzer winner and twice Pulitzer finalist Dan Barry as he was about to receive the sixth-annual Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square April 23, 2018, in Newport, Rhode Island. Past winners were

Dan's eloquent address in accepting the honor can be read here.

Me, Dan and Jim Ludes/Photo by Erin Demers

Me, Dan and Jim Ludes/Photo by Erin Demers

Good evening. I join Jim in welcoming everyone here on this beautiful spring evening. I am especially delighted that so many members of The Providence Journal family, past and present, are present.

I don’t remember when I first met Dan Barry.

It probably was in December 1987, when he arrived at The Journal, latest in a parade of reporters who came to Rhode Island hoping to write their way into distinction. It would have been in our old newsroom. I covered mental health and social services, and still do.

As a young but already senior staff writer by virtue of that beat, I would have introduced myself, exchanged small talk, and offered to help Dan however I could, as is my custom with all newcomers. And that likely was it. We had lots of new writers back then, a new one every month or two, or so it seemed. I had plenty of work, by day at the projo and by night at home writing fiction and caring for my two young daughters. I had no crying need of new friends, or one more writer brother. This was before the online world as we know it today, and our paper was thick with stories by an enormous staff spread around a downtown headquarters and a dozen bureaus. I would read a Dan Barry story if it caught my eye.

Which was almost immediately. When his work began to appear, it was evident that this tall, lanky guy from Long Island who loved baseball and possessed wonderful Irish wit had the gift.

You don’t pull many choice assignments your first weeks on the job – but whether he was writing a cop short or a weather story, Dan’s prose mesmerized with its poetic elegance, elevating the ordinary into the must-read. And when he got the chance to tackle bigger topics and more interesting people, as he soon did, he had no equal. Outside of fiction and a few journalists at a few papers and magazines, you rarely saw anything like it anywhere.

I can still picture Dan in that cavernous old newsroom, his sleeves rolled, his tie loose, conversing with editors Joel Rawson and Tom Heslin, who is here tonight, as he advanced to the head of the class -- and it was a distinguished class, as The Journal's many writing awards confirmed.

Being of Irish descent myself – like a lot of other people in this room tonight – I have come to believe that some things can only be explained by magic. I now understand that Dan’s way with words -- the power of his prose; his voice, unlike any other -- was magic of the highest literary order.

On deadline or with the developed piece, there was nothing Dan could not spin into gold. Sports. Crime. Business. Politics. Profile. Essay. You get the idea. I spent some time recently going through our archives, just to be sure my memory was true that there was no genre Dan did not own, and I can reliably report there was none.

When Dan left for The New York Times in the summer of 1995, he already had earned national recognition, including for his central role in The Journal’s 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. Even in that hallowed genre, Dan had the touch.

So there was little doubt that he would further distinguish himself at The Times -- but to what extent, I bet not even those who hired him could have imagined.

Leaving Rhode Island, Dan needed no Hogwarts, if you’ll pardon the cheap metaphor, but in New York he got even better, until he had joined the ranks of such masters of creative non-fiction as John McPhee and Susan Orlean. With his This Land series, he travelled to all 50 states, bringing back stories of places and people that were at once unique and yet also spoke to the universal bonds we share.

He has written about past lives, present lives, and the afterlife. With his rare ability to connect to people – most of them strangers when he knocks at their door – he has put flesh and blood on the cruel statistics of racial and social injustice and disparity, and on the challenges faced by the disenfranchised and disadvantaged. He has illuminated what is sometimes called man's inhumanity to man.

At a time of national division, of hatred and anger loose in the land, he has brought us stories of inspiration, of people who are sometimes called the salt of the earth. People we can admire and hold as heroes.

And wherever he has cast his spell, he has always produced treasure: a great and unforgettable story, built on the bones of truth.

He has, in other words, become the very definition of a public storyteller, which is why we honor him tonight.

We honor him not only for his journalism, but also for his books, most recently the extraordinary "The Boys in the Bunkhouse” -- and for his storytelling in the podcast hit Crimetown, with Marc Smerling, also with us this evening.

And in honoring Dan, we note that this prize is but the most recent in a list of honors that since joining The Times includes twice being named a Pulitzer finalist, and the bestowing of an honorary degree two years ago at his alma mater, St. Bonaventure University, which like Salve is another great Catholic school.

And so, it is our distinct honor to present him this award “for distinguished storytelling that has enriched the public dialogue.” Ladies and gentlemen, the 2018 Pell Center Prize Winner for Story in the Public Square, Dan Barry.

Dan's eloquent address in accepting the honor can be read here.

Me, Dan and Jim Ludes/Photo by Erin Demers

Me, Dan and Jim Ludes/Photo by Erin DemersGood evening. I join Jim in welcoming everyone here on this beautiful spring evening. I am especially delighted that so many members of The Providence Journal family, past and present, are present.

I don’t remember when I first met Dan Barry.

It probably was in December 1987, when he arrived at The Journal, latest in a parade of reporters who came to Rhode Island hoping to write their way into distinction. It would have been in our old newsroom. I covered mental health and social services, and still do.

As a young but already senior staff writer by virtue of that beat, I would have introduced myself, exchanged small talk, and offered to help Dan however I could, as is my custom with all newcomers. And that likely was it. We had lots of new writers back then, a new one every month or two, or so it seemed. I had plenty of work, by day at the projo and by night at home writing fiction and caring for my two young daughters. I had no crying need of new friends, or one more writer brother. This was before the online world as we know it today, and our paper was thick with stories by an enormous staff spread around a downtown headquarters and a dozen bureaus. I would read a Dan Barry story if it caught my eye.

Which was almost immediately. When his work began to appear, it was evident that this tall, lanky guy from Long Island who loved baseball and possessed wonderful Irish wit had the gift.

You don’t pull many choice assignments your first weeks on the job – but whether he was writing a cop short or a weather story, Dan’s prose mesmerized with its poetic elegance, elevating the ordinary into the must-read. And when he got the chance to tackle bigger topics and more interesting people, as he soon did, he had no equal. Outside of fiction and a few journalists at a few papers and magazines, you rarely saw anything like it anywhere.

I can still picture Dan in that cavernous old newsroom, his sleeves rolled, his tie loose, conversing with editors Joel Rawson and Tom Heslin, who is here tonight, as he advanced to the head of the class -- and it was a distinguished class, as The Journal's many writing awards confirmed.

Being of Irish descent myself – like a lot of other people in this room tonight – I have come to believe that some things can only be explained by magic. I now understand that Dan’s way with words -- the power of his prose; his voice, unlike any other -- was magic of the highest literary order.

On deadline or with the developed piece, there was nothing Dan could not spin into gold. Sports. Crime. Business. Politics. Profile. Essay. You get the idea. I spent some time recently going through our archives, just to be sure my memory was true that there was no genre Dan did not own, and I can reliably report there was none.

When Dan left for The New York Times in the summer of 1995, he already had earned national recognition, including for his central role in The Journal’s 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. Even in that hallowed genre, Dan had the touch.

So there was little doubt that he would further distinguish himself at The Times -- but to what extent, I bet not even those who hired him could have imagined.

Leaving Rhode Island, Dan needed no Hogwarts, if you’ll pardon the cheap metaphor, but in New York he got even better, until he had joined the ranks of such masters of creative non-fiction as John McPhee and Susan Orlean. With his This Land series, he travelled to all 50 states, bringing back stories of places and people that were at once unique and yet also spoke to the universal bonds we share.

He has written about past lives, present lives, and the afterlife. With his rare ability to connect to people – most of them strangers when he knocks at their door – he has put flesh and blood on the cruel statistics of racial and social injustice and disparity, and on the challenges faced by the disenfranchised and disadvantaged. He has illuminated what is sometimes called man's inhumanity to man.

At a time of national division, of hatred and anger loose in the land, he has brought us stories of inspiration, of people who are sometimes called the salt of the earth. People we can admire and hold as heroes.

And wherever he has cast his spell, he has always produced treasure: a great and unforgettable story, built on the bones of truth.

He has, in other words, become the very definition of a public storyteller, which is why we honor him tonight.

We honor him not only for his journalism, but also for his books, most recently the extraordinary "The Boys in the Bunkhouse” -- and for his storytelling in the podcast hit Crimetown, with Marc Smerling, also with us this evening.

And in honoring Dan, we note that this prize is but the most recent in a list of honors that since joining The Times includes twice being named a Pulitzer finalist, and the bestowing of an honorary degree two years ago at his alma mater, St. Bonaventure University, which like Salve is another great Catholic school.

And so, it is our distinct honor to present him this award “for distinguished storytelling that has enriched the public dialogue.” Ladies and gentlemen, the 2018 Pell Center Prize Winner for Story in the Public Square, Dan Barry.

Published on April 24, 2018 13:37

Dan Barry on writing

You will rarely, if ever, read such an exceptional essay about writing and storytelling than this one by author, New York Times staff writer, and Pulitzer Prize winner and twice finalist Dan Barry. He delivered these remarks on accepting the sixth annual Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square the evening of April 23, 2018, at the center in Newport.

Dan, we cannot thank you enough for all your work -- and this wonderful description of our craft! It brings to mind Stephen King's "On Writing," a masterpiece of how the written word best works.

(My remarks introducing Dan can be read here.)

Thank you, Wayne. Thank you, Jim.

Just know that it is now officially too late for you and the Pell Center to change your mind. Mary, start the car.

What an honor it is to be receiving this award. It means so much because The Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square is not about investigative reporting, or deadline reporting, or opinion writing. It centers on something less celebrated -- but more elemental. Something that binds all nonfiction at its best.

That, of course, is the telling of the story:

The pursuit of enticing the audience to step out of their own lives and into the lives of others -- all through the alchemy of facts, and words, and images, carefully arranged.

I just turned 60 years old, and for most of my life, if someone bothered to ask what I did for a living, I would proudly say:

I’m a newspaper reporter. A scribe. A hack. An ink-stained wretch.

Or, if I wanted to impress the ladies: I’m a journalist.

But a few years ago, I was speeding in a rental car through a place called Washington, Kansas. You know where that is, right?

Between Marysville and Scandia?

Anyway, I was speeding down Highway 36, singing along with the radio to “Nights in White Satin” by the Moody Blues:

Nights in white satin, I don’t know the wordsWhen a Kansas state trooper pulled me over.La la la la la, I am so screwed.

License and registration.

Then the trooper said: Mind if I ask a question? What’s a fella from New Jersey, driving a car with Colorado plates, doing in northern Kansas.

It’s for my job, sir.

What do you do?

I’m a reporter for The New York Times (This is before our name was presidentially changed to The Failing New York Times.).

Don’t read it, the trooper said. What’s your business here?

Well, officer, if you must know.

I was just in Junction City, Kansas, where I watched the inauguration of President Obama with some middle school students -- the children of soldiers at Fort Riley preparing for another deployment. They have a lot at stake in the new president, and I wanted to be there.

Uh huh. And where are you headed?

Carleton, Nebraska. It’s a town of about 140 people, and a few days ago a masked man robbed the bank, about the only business left in town. Witnesses described him as having – quote -- a LARGE NOSE AND FAT FINGERS.

You haven’t seen anyone fitting that description, have you, officer? Large nose? Fat fingers?

The trooper looked at me for an uncomfortable length of time. Finally, he said: Have a nice day –Oh, and I almost forgot. Here’s a speeding ticket for $123.

That state trooper gave me more than a speeding ticket. He forced me to think about that eternal, self-involved question: Who am I What is it I do?

Well, like so many people gathered here tonight, I guess I’m a storyteller.

And, to my mind, there is no greater calling.

To me, telling stories is like the childhood pursuit of catching fireflies in a glass jar. In the never-ending rush of time, you reach out to capture a glowing moment.

You hold it up to examination with a kind of informed innocence.

You meditate on its individual wonder.

You try to see its place in the larger context of the universe.

I’ve always been like this. I’ve always had a pen and pad with me – at considerable cost to many suit jackets and pairs of khaki pants. But I want to be always ready to capture another firefly of a moment.

Here, for example, is my life. More than 30 years ago, I was at a county fair in Connecticut, and there was an attraction for – a large pig. The recording of the carnival barker’s pitch was so beguiling to me that I listened to over and over, until I had written it down exactly:

Ladies and gentlemen, your attention please. If you have come to see the rare and unusual, come right in and see Big Alfie, the giant pig. Big Alfie is twice the size of the average pig. He is over 1,000 pounds. He is eight feet long and four feet tall. His jaws are so powerful that they could take a man’s leg off -- in one bite. Come right in and see Big Alfie before you leave this arena. He’s one of a kind!

What’s crazy about this is: I still have that scrawled note. And while I have never written a story about Big Alfie, here’s the thing: I still think that, someday -- maybe I will.

There are many reasons why I am this way.

For one thing, I had what others might call a dysfunctional childhood -- but I prefer to think of it as merely insane. There was a lot of drinking, and fighting, and searching the skies for UFOs – as you do.

But at the center of it all was The Word.

My mother, an orphaned girl from County Galway, was a kind of suburban seanachie – spinning Homeric epics out of a simple run to the supermarket for a loaf of bread.

My father, a New Yorker hardened by the privations of the Great Depression, was forever delivering speeches in the kitchen – to a captive audience of eight, including three dogs -- on how the powerful need to be held accountable.

And me? I got beat up a lot as a kid. My parochial school uniform included green pants, green tie, green and gold belt, and a gold shirt with the insignia of the Holy Spirit embroidered on the shirt pocket.

I looked like an usher at a St. Patrick’s Day party from hell.

It was catnip for bullies.

But you take these three gifts – the gift of language, the gift of skepticism, and the gift of the victim’s perspective – and my future was all but predestined.

Another reason why I am so drawn to the telling of stories is that I somehow wound up in Rhode Island, in the newsroom of the Providence Journal. At one point I was working on a project about the state’s infamous banking crisis. This project was chock-full of colorful characters, operatic moments, and larcenous behavior.

That’s right: I was writing about North Providence.

Anyway, I was pushing to get the story in the paper right away, because I had been conditioned to always be on deadline – always be in the paper. But my editor, Tom Heslin, who’s here this evening, sent me a three-word note through the newspaper’s messaging system.

The note said, simply: Slow it down.

Slow. It. Down.

I have thought about those three words more than Tom could have imagined. Beyond being good advice for how to live, “Slow It Down” has meant – in terms of storytelling – to savor that which is before you.

To recognize the epiphanies to be found in the throwaway moment; in the seemingly mundane details; in the lives of the voiceless, the vulnerable, the people who are just trying to get by.

Here’s how I slow it down.

I read a small article about a man who saved someone from drowning off the shores of Coney Island, and I think: I’ve never saved anyone from drowning. What does that feel like? Is it slippery? Is the victim buoyant in the water? It may not be news – but it is a story about the preciousness of life.

I go out on a torrential day in Manhattan, hear the song of rain-soaked men selling cheap umbrellas -- “’Brella, ‘brella, ‘brella” – and wonder: Where do all these umbrellas come from? And there’s a story.

I spend a lot of time in Hampton Inns and Holiday Inn Expresses, and I think about the housecleaners -- the maids, who spend their days cleaning the messes of others. They are invariably immigrants, and I ask: What must it be like to be an immigrant maid, working in a hotel – owned by Donald Trump.

And there is a story.

The mind trick, for me, is to try to put myself not only in the shoes of others – but in their skin as well.

At the same time, stories told by others have informed my worldview. Others who are here this evening.

Marc Smerling, whose multimedia work includes the “Crimetown” podcast. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

Kevin Cullen, the great Boston columnist and the Boswell to Whitey Bulger.

Kevin Sullivan and Mary Jordan of the Washington Post, who infuriate me because they never stop working. Kevin leaves tomorrow for Morocco. To out that in perspective, that’s even farther than Woonsocket.

Wayne Miller, who just recently helped the world understand the enigma that is Michael Flynn.

And, especially, other former colleagues of mine from the Providence Journal, many of whom I see here tonight. It shouldn’t be forgotten that the Providence Journal led the way in publishing narrative non-fiction of high quality in the pages of newspapers.

I am so grateful to have worked there, with you.

So thank you again for this humbling honor.

Storytelling sustains us. It helps us to navigate the shoals of life. To understand our everyday existence. To empathize with our brothers and sisters. To embrace the human condition in all its complicated wonder and glory.

Shout it from the rooftops and in the public square. Say Hallelujah. Say Amen.

Thank you.

Dan, we cannot thank you enough for all your work -- and this wonderful description of our craft! It brings to mind Stephen King's "On Writing," a masterpiece of how the written word best works.

(My remarks introducing Dan can be read here.)

Thank you, Wayne. Thank you, Jim.

Just know that it is now officially too late for you and the Pell Center to change your mind. Mary, start the car.

What an honor it is to be receiving this award. It means so much because The Pell Center Prize for Story in the Public Square is not about investigative reporting, or deadline reporting, or opinion writing. It centers on something less celebrated -- but more elemental. Something that binds all nonfiction at its best.

That, of course, is the telling of the story:

The pursuit of enticing the audience to step out of their own lives and into the lives of others -- all through the alchemy of facts, and words, and images, carefully arranged.

I just turned 60 years old, and for most of my life, if someone bothered to ask what I did for a living, I would proudly say:

I’m a newspaper reporter. A scribe. A hack. An ink-stained wretch.

Or, if I wanted to impress the ladies: I’m a journalist.

But a few years ago, I was speeding in a rental car through a place called Washington, Kansas. You know where that is, right?

Between Marysville and Scandia?

Anyway, I was speeding down Highway 36, singing along with the radio to “Nights in White Satin” by the Moody Blues:

Nights in white satin, I don’t know the wordsWhen a Kansas state trooper pulled me over.La la la la la, I am so screwed.

License and registration.

Then the trooper said: Mind if I ask a question? What’s a fella from New Jersey, driving a car with Colorado plates, doing in northern Kansas.

It’s for my job, sir.

What do you do?

I’m a reporter for The New York Times (This is before our name was presidentially changed to The Failing New York Times.).

Don’t read it, the trooper said. What’s your business here?

Well, officer, if you must know.

I was just in Junction City, Kansas, where I watched the inauguration of President Obama with some middle school students -- the children of soldiers at Fort Riley preparing for another deployment. They have a lot at stake in the new president, and I wanted to be there.

Uh huh. And where are you headed?

Carleton, Nebraska. It’s a town of about 140 people, and a few days ago a masked man robbed the bank, about the only business left in town. Witnesses described him as having – quote -- a LARGE NOSE AND FAT FINGERS.

You haven’t seen anyone fitting that description, have you, officer? Large nose? Fat fingers?

The trooper looked at me for an uncomfortable length of time. Finally, he said: Have a nice day –Oh, and I almost forgot. Here’s a speeding ticket for $123.

That state trooper gave me more than a speeding ticket. He forced me to think about that eternal, self-involved question: Who am I What is it I do?

Well, like so many people gathered here tonight, I guess I’m a storyteller.

And, to my mind, there is no greater calling.

To me, telling stories is like the childhood pursuit of catching fireflies in a glass jar. In the never-ending rush of time, you reach out to capture a glowing moment.

You hold it up to examination with a kind of informed innocence.

You meditate on its individual wonder.

You try to see its place in the larger context of the universe.

I’ve always been like this. I’ve always had a pen and pad with me – at considerable cost to many suit jackets and pairs of khaki pants. But I want to be always ready to capture another firefly of a moment.

Here, for example, is my life. More than 30 years ago, I was at a county fair in Connecticut, and there was an attraction for – a large pig. The recording of the carnival barker’s pitch was so beguiling to me that I listened to over and over, until I had written it down exactly:

Ladies and gentlemen, your attention please. If you have come to see the rare and unusual, come right in and see Big Alfie, the giant pig. Big Alfie is twice the size of the average pig. He is over 1,000 pounds. He is eight feet long and four feet tall. His jaws are so powerful that they could take a man’s leg off -- in one bite. Come right in and see Big Alfie before you leave this arena. He’s one of a kind!

What’s crazy about this is: I still have that scrawled note. And while I have never written a story about Big Alfie, here’s the thing: I still think that, someday -- maybe I will.

There are many reasons why I am this way.

For one thing, I had what others might call a dysfunctional childhood -- but I prefer to think of it as merely insane. There was a lot of drinking, and fighting, and searching the skies for UFOs – as you do.

But at the center of it all was The Word.

My mother, an orphaned girl from County Galway, was a kind of suburban seanachie – spinning Homeric epics out of a simple run to the supermarket for a loaf of bread.

My father, a New Yorker hardened by the privations of the Great Depression, was forever delivering speeches in the kitchen – to a captive audience of eight, including three dogs -- on how the powerful need to be held accountable.

And me? I got beat up a lot as a kid. My parochial school uniform included green pants, green tie, green and gold belt, and a gold shirt with the insignia of the Holy Spirit embroidered on the shirt pocket.

I looked like an usher at a St. Patrick’s Day party from hell.

It was catnip for bullies.

But you take these three gifts – the gift of language, the gift of skepticism, and the gift of the victim’s perspective – and my future was all but predestined.

Another reason why I am so drawn to the telling of stories is that I somehow wound up in Rhode Island, in the newsroom of the Providence Journal. At one point I was working on a project about the state’s infamous banking crisis. This project was chock-full of colorful characters, operatic moments, and larcenous behavior.

That’s right: I was writing about North Providence.

Anyway, I was pushing to get the story in the paper right away, because I had been conditioned to always be on deadline – always be in the paper. But my editor, Tom Heslin, who’s here this evening, sent me a three-word note through the newspaper’s messaging system.

The note said, simply: Slow it down.

Slow. It. Down.

I have thought about those three words more than Tom could have imagined. Beyond being good advice for how to live, “Slow It Down” has meant – in terms of storytelling – to savor that which is before you.

To recognize the epiphanies to be found in the throwaway moment; in the seemingly mundane details; in the lives of the voiceless, the vulnerable, the people who are just trying to get by.

Here’s how I slow it down.

I read a small article about a man who saved someone from drowning off the shores of Coney Island, and I think: I’ve never saved anyone from drowning. What does that feel like? Is it slippery? Is the victim buoyant in the water? It may not be news – but it is a story about the preciousness of life.

I go out on a torrential day in Manhattan, hear the song of rain-soaked men selling cheap umbrellas -- “’Brella, ‘brella, ‘brella” – and wonder: Where do all these umbrellas come from? And there’s a story.

I spend a lot of time in Hampton Inns and Holiday Inn Expresses, and I think about the housecleaners -- the maids, who spend their days cleaning the messes of others. They are invariably immigrants, and I ask: What must it be like to be an immigrant maid, working in a hotel – owned by Donald Trump.

And there is a story.

The mind trick, for me, is to try to put myself not only in the shoes of others – but in their skin as well.

At the same time, stories told by others have informed my worldview. Others who are here this evening.

Marc Smerling, whose multimedia work includes the “Crimetown” podcast. Perhaps you’ve heard of it.

Kevin Cullen, the great Boston columnist and the Boswell to Whitey Bulger.

Kevin Sullivan and Mary Jordan of the Washington Post, who infuriate me because they never stop working. Kevin leaves tomorrow for Morocco. To out that in perspective, that’s even farther than Woonsocket.

Wayne Miller, who just recently helped the world understand the enigma that is Michael Flynn.

And, especially, other former colleagues of mine from the Providence Journal, many of whom I see here tonight. It shouldn’t be forgotten that the Providence Journal led the way in publishing narrative non-fiction of high quality in the pages of newspapers.

I am so grateful to have worked there, with you.

So thank you again for this humbling honor.

Storytelling sustains us. It helps us to navigate the shoals of life. To understand our everyday existence. To empathize with our brothers and sisters. To embrace the human condition in all its complicated wonder and glory.

Shout it from the rooftops and in the public square. Say Hallelujah. Say Amen.

Thank you.

Published on April 24, 2018 07:19

February 26, 2018

#33Stories

I was several years into my journalism career when, 33 years ago this May, Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine became the first major publication to print one of my short stories. Many more would follow that story, "The Warden" -- in mystery, horror and science-fiction magazines. And then came the books, the first, Thunder Rise, a novel. Soon, my 17th book, the sequel to Toy Wars, will appear...

And so, to mark this long run, starting May 1, and continuing daily through May 31, I will publish an excerpt from 16 of those short stories and each of the 17 books (with three excerpts on Memorial Day, to total #33Stories). I will provide brief commentary on the excerpts, and the times in which they were published. A sort of retrospective, if you will, of my non-journalism body of work.

Should be fun! See you on May 1.

Published on February 26, 2018 15:11

February 17, 2018

Inside Story

In conjunction with Story in the Public Square, the weekly Rhode Island PBS/SiriusXM Satellite Radio show I co-host and co-produce with Pell Center head Jim Ludes, I write an occasional column, Inside Story, for The Providence Journal. And I frequently produce a podcast from these shows.

We have a marvelous range of guests -- noted scholars and storytellers from the worlds of film, TV, still photography, books, journalism, social activism, academia and more -- more than a few Pulitzer and other prize-winners -- and I highly recommend you see the full slate at the Story in Public Square episode site. Story is a partnership of the Pell Center, where I am a visiting fellow, and The Providence Journal, where I have been a staff writer for many years.

So let's get to it. I will archive my Inside Story columns -- and links to the podcasts -- here on my blog, and I invite you to read... and to download and listen. I always welcome feedback, and suggestions for guests. We are in Season Three and growing, so welcome to the family!

-- Weekend of February 17, 2018: Immigration, Latino issues, with guest Gabriela Domenzain.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

I knew from meeting Gabriela Domenzain last fall that she would soon make her mark in Rhode Island. The newly arrived head of Roger Williams University’s Latino Policy Institute, Domenzain brought impressive credentials from her time in Washington, the national media and the Hispanic advocacy organization National Council of La Raza, now known as UnidosUS. With her distinctive energy, Domenzain, the daughter of Mexican immigrant doctors, got right to work on Latino issues, including significant educational and economic disparities here and across the nation.

But the public has come to know her best with her recent involvement in the case of longtime Rhode Island resident Lilian Calderon, wife of U.S. citizen Luis Gordillo and mother of their two young children who this week was released after a month in federal detention. Thirty years old now, Calderon came to America from Guatemala as a 3-year-old, and in January she was seized by ICE, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. Her story made national headlines as Congress once again tackles the hot-button issue of immigration.

Gordillo, daughter Natalie, Miller, Domenzain, and Ludes on setSo we were keen to discuss that case and the larger issues surrounding it with Domenzain, this week’s guest on “Story in the Public Square,” TV and radio. Her intimate knowledge of immigration and her life experiences give Domenzain an authority that is often lacking in the local and national conversations, when some people are quick to post Facebook comments and fire off tweets based on hot emotion and misinformation, not cold facts.

Gordillo, daughter Natalie, Miller, Domenzain, and Ludes on setSo we were keen to discuss that case and the larger issues surrounding it with Domenzain, this week’s guest on “Story in the Public Square,” TV and radio. Her intimate knowledge of immigration and her life experiences give Domenzain an authority that is often lacking in the local and national conversations, when some people are quick to post Facebook comments and fire off tweets based on hot emotion and misinformation, not cold facts.Lilian, Domenzain said, was seeking to set her record straight when “she was literally vanished from her community without any explanation.” For Domenzain, it represented a chilling change of tactics by federal authorities. It was one of the first such in New England, she said — but not the last in the region and country, she fears, under the Trump administration and a Republican-controlled Congress.

How did we get here? we asked. Efforts at comprehensive immigration reform date to the presidency of Ronald Reagan, more than three decades ago.

From the GOP side, Domenzain said, an explanation can be found in those congressional Republicans who bitterly opposed Barack Obama in his first term. “A backlash,” she called it, led by extremists who understood that a hard-line anti-immigration stand would appeal to some white voters and might prevent America’s first African-American president from winning a second term.

“We’re talking about the Tea Party and the very, very right fringe extreme caucus that is now in the middle of the Republican Party,” Domenzain said. “It used to be fringe. Now it’s actually front and center.”

Across the aisle, Domenzain asserted, other factors were in play.

“On the Democratic side, they haven’t decided to use their political capital on these issues,” she said. “President Obama tried his first year. It didn’t work. He decided to go with health-care reform, which, by the way, was the number-one priority for Latino voters because we are the most underinsured and uninsured population.”

Like many others, Domenzain sees this year’s elections as potentially game-changing. Surveys suggest that greater numbers of Hispanic, African-American and other traditionally non-Republican voters will cast ballots than in 2016.

That, she said, does not bode well for today’s Washington.

“The Republican Party has no chance with Latinos right now. They have the most anti-immigrant, racist president in the history of this country and Latinos recognize that they’re scapegoats.”

I have only touched on our wide-ranging conversation (which, I would note, Lilian’s husband and one of the children watched from the control room). Wherever you stand on the immigration debate, this is a broadcast well worth hearing or watching.

*****

-- Weekend of January 27, 2018: Genocide, the Holocaust, with guest Omer Bartov.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

On Saturday, the world marks International Holocaust Remembrance Day, #WeRemember, in honor of the 6 million Jewish victims of Nazism and the millions of others killed when Hitler was in power. So it is appropriate that during this weekend’s TV and radio broadcasts of “Story in the Public Square” we feature Omer Bartov, the esteemed Brown University historian who has written extensively about Nazi Germany and ethnic cleansing.

His latest book, “Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz,” published this week by Simon & Schuster, is an extraordinary story of how one small town in Eastern Europe descended into unspeakable atrocity in the first half of the 20th century.

Miller, Ludes, Bartov.

Miller, Ludes, Bartov.“Genocide is often being studied from the top,” Bartov tells us on “Story in the Public Square,” “from the point of view of the perpetrators: how was it organized, how do you organize the mass destruction of a group. One of the ideas in explaining that was you have to dehumanize people, that you have to think of them as different from us, as not normal.”

In “Anatomy of a Genocide,” Bartov focused on the border town of Buczacz, which is today part of Ukraine. Before Hitler and Stalin, the Jewish, Polish and Ukrainian residents there had gone centuries without conflict.

“I wouldn’t say it was a harmonious coexistence, but they lived together and they did not know any other reality,” Bartov said. “This was what they had always done.”

“They didn’t have gangs and killing squads or anything of that sort,” I said.

“No, no, no.”

“They had their differences, but they lived together.”

“Yes,” Bartov said. “They lived side by side quite peacefully. And they often speak each other’s languages, they go to school together.”

As World War II unfolded, German authorities took control of Buczacz after driving out the occupying Soviets.

“The mass killing begins in the late summer, early fall of 1942,” Bartov said, “and by spring 1943 most of the Jewish population in that town has been murdered, about 10,000 people. So by June 1943, this area is decreed by the Germans ‘clean of Jews.’”

“Who did the killing?” my co-host Jim Ludes asked.

“The killing of the Jews is done primarily by about 20 to 30 Germans who are members of the security police,” Bartov said.

Police, not soldiers.

And not at Auschwitz or Dachau, but in Any Town in East Europe — as neighbors watched and, in some instances, cooperated.

As the Bosnian and Rwandan genocides and other ethnic cleansing after (and before) World War II demonstrate, the Holocaust was not unique. Given the right, terrible conditions, human nature can turn horrific.

Bartov explained how ordinary people can conspire in such a descent into the worst darkness.

Say, for example, he told us, “you live in a house and the house has four stories and the people upstairs have the nicest apartment and they have a piano and they’re taken out by the police and shot on the street. You had nothing to do with it. You were friends, your daughters went to school together. Now what happens to their apartment? Who is going to live there? If you don’t move in — it’s a nicer apartment, it has better air, it’s the fourth floor, it has a piano — somebody else will.

“So you move in. And once you’ve moved in, well, you are already part of this process. On the local level, there are no simple victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. Everyone is involved in this process. Everybody gets roped in in one way or another. And the veneer of civilization — of saying hello to your neighbors in the morning — suddenly disappears.”

This process of demonizing or dehumanizing someone who is racially, ethnically or religiously different, Bartov says, is key. He sees similar social dynamics at work today in many parts of the world, including America, where racism and nativism bring headlines.

Born and raised in Israel, where he served four years in the army, Bartov is the son of a woman who grew up in Buczacz, so there is a strong personal element to “Anatomy of a Genocide.” Hear more about that and Bartov’s latest book this weekend on “Story in the Public Square.”

Published on February 17, 2018 15:07

December 11, 2017

Remembering my father, Roger Linwood Miller

Author's Note: I wrote this five years ago, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of my father's death. Like his memory, it has withstood the test of time. I have slightly updated it for today, December 11, 2017, the 15th anniversary of his death. Read the original here.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 15 years ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 15th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 15 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now for three years and my best friend for more than a decade: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, Bella, Vivvie and Liv, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister Mary Lynne and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died in 2015. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller

I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 15 years ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 15th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 15 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now for three years and my best friend for more than a decade: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, Bella, Vivvie and Liv, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sister Mary Lynne and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that my other sister, his younger daughter, Lynda, died in 2015. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Published on December 11, 2017 11:07

November 3, 2017

We could use more Franks

I never met anyone like the late Frank Beazley, nor am ever likely to meet anyone like him again. My time with him -- culminating but not ending with "The Growing Seasons," my 12-part 2006 Providence Journal series, republished below -- was a precious blessing. I think of him often still. He was a great man and I was honored to be his friend.

Despite a cruel upbringing followed by a tragic accident that broke his body and could have ruined his soul, he instead became an extraordinarily inspiring, uplifting and selfless champion of those without power or voice. Also, a celebrated artist, devoted gardener and man of fine humor. In these times of dark, narcissistic so-called "leaders" in Washington who are determined to divide, break and dehumanize, and sit idly as the planet screams in death agony, we could use more Franks.

Read, or re-read, "The Growing Season," the story of Frank.

Despite a cruel upbringing followed by a tragic accident that broke his body and could have ruined his soul, he instead became an extraordinarily inspiring, uplifting and selfless champion of those without power or voice. Also, a celebrated artist, devoted gardener and man of fine humor. In these times of dark, narcissistic so-called "leaders" in Washington who are determined to divide, break and dehumanize, and sit idly as the planet screams in death agony, we could use more Franks.

Read, or re-read, "The Growing Season," the story of Frank.

Published on November 03, 2017 02:58

November 1, 2017

The last word

At 10:20 a.m. yesterday, Halloween, one of my favorite holidays, I wrote the last of the 134,393 words of my 17th book, Transformers, sequel (and prequel) to Toy Wars. It opens in 1903 with Hasbro founders Henry and Hillel Hassenfeld immigrating to America to escape religious persecution in their native Poland. They were penniless teenage refugees then. From their new home, they later saved hundreds (if not thousands) of fellow Jews from suffering and death, and their descendants and their company have carried on that tradition of giving back, to people of all faiths.

After writing that last word, I drove to visit Henry's and Hillel's final resting place, in a cemetery near my home. As is custom, I left a stone, on Henry's grave, next to his brother. Then I visited the nearby graves of Merrill, Henry's son; Sylvia, Merrill's wife; and Stephen, their first son. Alan, protagonist of both Toy Wars and Transformers, often visits, too. It was a crisp, sunny morning following a ferocious storm and I cleared some branches that had fallen. I felt at ease.

After writing that last word, I drove to visit Henry's and Hillel's final resting place, in a cemetery near my home. As is custom, I left a stone, on Henry's grave, next to his brother. Then I visited the nearby graves of Merrill, Henry's son; Sylvia, Merrill's wife; and Stephen, their first son. Alan, protagonist of both Toy Wars and Transformers, often visits, too. It was a crisp, sunny morning following a ferocious storm and I cleared some branches that had fallen. I felt at ease.

Published on November 01, 2017 02:16

July 4, 2017

"No more essential ingredient than a free, strong and independent press"

Happy Independence Day! As we celebrate the birth of our nation, on July 4, 1776, in Philadelphia, let us thank the Founders for their courage and wisdom in an act and a subsequent constitution unlike any previously seen that has guided a diverse people into 2017.

Let’s thank the many good women and men who over the centuries have given selflessly – and, those lost in war, their very selves – to their fellow citizens, often without great financial reward or recognition: the teachers, healthcare professionals, social workers, clergy, police, veterans, patriots of all stripes, and many more. The list is long; the final result, a nation still united and still, despite inevitable flaws and divisions, a remarkable example of democracy.

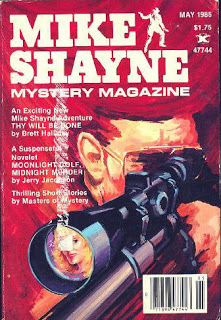

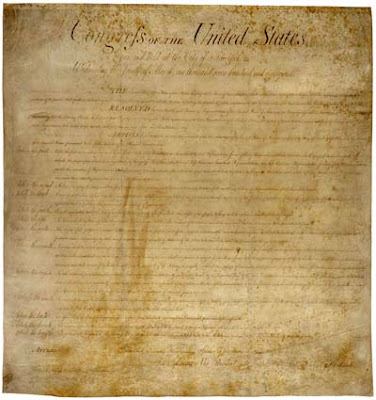

I would ask also that we reflect on the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791, specifically the First Amendment: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. That Madison, et al, placed it first was no accident. The first casualty of any repressive regime is the loss of the freedom to say and publish what people will. King George III ruled just such a regime.

The Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights

In Washington and beyond today, we are witnessing an ugly attack against press freedom. It is not explicitly stated in such terms, at least not frequently, but the message of “fake news” and of members of the press being “the enemy of the people” and the dog-whistle suggestions that harming a journalist would be heroic are unambiguous evidence of that attack.

I have been a professional journalist my entire adult life, through seven presidents: Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump. And I remember well presidents before that career: Gerald Ford, Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy. Every one of them, to varying degrees, faced the scrutiny of the press. And while they may have disliked or hated it, with the exception of 45, they all understood (as presidents before them did) why Madison, et al, made press freedom the first of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights. Through the colonial press, they had long experience with tyranny.

The New York Times and Washington Post, among other practitioners of the First Amendment, are among those publications that have been singularly targeted in this year’s attacks against the press. Just as the Founders would have wished – if you know any of the history of the colonial press, starting with journalist Benjamin Franklin, you can be sure of it –the journalists at these contemporary publications have not been intimidated. They have continued on their constitutionally enshrined mission despite the sort of hate, threats, scorn and ignorance directed against not only the press, but other pillars of our society, science among them.

We live in perilous times.

On Sunday, The Times’ Jim Rutenberg wrote a thoughtful essay on this subject. Whatever your politics, it is well worth reading. In his column, Rutenberg quoted Franklin and several presidents on the press; they are worth reading too, as we celebrate our independence, an independence supported by the press of a long-ago era.

Here are a few of them:

“Power can be very addictive, and it can be corrosive. And it’s important for the media to call to account people who abuse their power, whether it be here or elsewhere.” -- George W. Bush, 2017

“There is no more essential ingredient than a free, strong and independent press to our continued success in what the founding fathers called our ‘noble experiment’ in self-government.” -- Ronald Reagan, 1983

“The freedom of speech may be taken away — and, dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep, to the slaughter.” -- George Washington, 1783

“There is nothing so fretting and vexatious, nothing so justly terrible to tyrants, and their tools and abettors, as a free press.”-- Samuel Adams, 1768

“Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation must begin by subduing the freeness of speech.”-- Benjamin Franklin, 1722

Happy Independence Day! And as always, please subscribe to a newspaper.

Let’s thank the many good women and men who over the centuries have given selflessly – and, those lost in war, their very selves – to their fellow citizens, often without great financial reward or recognition: the teachers, healthcare professionals, social workers, clergy, police, veterans, patriots of all stripes, and many more. The list is long; the final result, a nation still united and still, despite inevitable flaws and divisions, a remarkable example of democracy.

I would ask also that we reflect on the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791, specifically the First Amendment: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. That Madison, et al, placed it first was no accident. The first casualty of any repressive regime is the loss of the freedom to say and publish what people will. King George III ruled just such a regime.

The Bill of Rights

The Bill of RightsIn Washington and beyond today, we are witnessing an ugly attack against press freedom. It is not explicitly stated in such terms, at least not frequently, but the message of “fake news” and of members of the press being “the enemy of the people” and the dog-whistle suggestions that harming a journalist would be heroic are unambiguous evidence of that attack.

I have been a professional journalist my entire adult life, through seven presidents: Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump. And I remember well presidents before that career: Gerald Ford, Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy. Every one of them, to varying degrees, faced the scrutiny of the press. And while they may have disliked or hated it, with the exception of 45, they all understood (as presidents before them did) why Madison, et al, made press freedom the first of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights. Through the colonial press, they had long experience with tyranny.

The New York Times and Washington Post, among other practitioners of the First Amendment, are among those publications that have been singularly targeted in this year’s attacks against the press. Just as the Founders would have wished – if you know any of the history of the colonial press, starting with journalist Benjamin Franklin, you can be sure of it –the journalists at these contemporary publications have not been intimidated. They have continued on their constitutionally enshrined mission despite the sort of hate, threats, scorn and ignorance directed against not only the press, but other pillars of our society, science among them.

We live in perilous times.

On Sunday, The Times’ Jim Rutenberg wrote a thoughtful essay on this subject. Whatever your politics, it is well worth reading. In his column, Rutenberg quoted Franklin and several presidents on the press; they are worth reading too, as we celebrate our independence, an independence supported by the press of a long-ago era.

Here are a few of them:

“Power can be very addictive, and it can be corrosive. And it’s important for the media to call to account people who abuse their power, whether it be here or elsewhere.” -- George W. Bush, 2017

“There is no more essential ingredient than a free, strong and independent press to our continued success in what the founding fathers called our ‘noble experiment’ in self-government.” -- Ronald Reagan, 1983

“The freedom of speech may be taken away — and, dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep, to the slaughter.” -- George Washington, 1783

“There is nothing so fretting and vexatious, nothing so justly terrible to tyrants, and their tools and abettors, as a free press.”-- Samuel Adams, 1768

“Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation must begin by subduing the freeness of speech.”-- Benjamin Franklin, 1722

Happy Independence Day! And as always, please subscribe to a newspaper.

Published on July 04, 2017 03:19

May 17, 2017

'The truth, is we need to do a better job'

"Childhood trauma has its effects on intellectual, social and emotional well-being of a child. The truth is we need to do a better job attending to the complex needs of these vulnerable children: families, agencies, social workers teachers, psychologists, politicians etc. Let us consider this quote from Pablo Casals: 'to the whole world you might be one person, but to one person you might just be the whole world.' " -- Mary Beth Berube

Left to right:Dave and Rob Berube, John Kostrzewa, Mary Beth Berube, me.

Left to right:Dave and Rob Berube, John Kostrzewa, Mary Beth Berube, me. I have been blessed in my decades as a journalist and writer to meet some of the most courageous and noble people who live among us. The Berubes are three of them. We all were honored today at the 29th annual Metcalf Media Awards from Rhode Island for Community and Justice, a wonderful organization dedicated to "fighting bias, bigotry and racism and promoting understanding together." My three-part Providence Journal series on the Berubes, "Saving Rob," about a dysfunctional and sometimes criminally harmful social-service agency, published last summer, won in the Print Daily category. John Kostrzewa edited the series, and our new executive editor, Alan Rosenberg, took time from a busy day to join us. And I was surprised and delighted that my Story in the Public Square partner, Pell Center director Jim Ludes, and Kristine Hendrickson, Associate Vice President for University Relations/Chief Communications Officer at Salve Regina University, came, too.

Below are Mary Beth's remarks, and after those, mine, followed by a list of the other winners. Congratulations to them!

Mary Beth Berube:

We are very excited to be here to honor Wayne for winning the Metcalf Award for his three-part series Saving Rob. Rob is our son and we are very grateful to Mr. Miller for writing such a sensitive piece detailing his life as a child in state care.