G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 15

May 24, 2018

#33Stories: Day 24, "Paper Boy," a novel

#33Stories

No. 24: “Paper Boy: A novel about media, truth and other important things.”

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Excerpt follows this synopsis

Since we’ve been on the topic of newspapers lately, I present “Paper Boy,” subtitled “A Novel About Media, Truth and Other Important Things.”

I wrote this unpublished book several years ago, during the first wave of turmoil that the digital revolution wrought upon the venerable print-journalism industry. Set inside the fictitious Daily Tribune, published in the real city of Boston, it chronicles the journey that popular columnist Nick and colleagues take as the once-proud and Pulitzer-winning paper’s new owners insist that the ridiculous mantra of “Good News Rules” is the key not only to survival but to restored glory.

Meaning, write “good” stuff to balance the “bad” headlines of crime, crooked politics and so forth.

Write “good” stories because that’s what readers and advertisers want, and “Good New Rules” is the key to reversing declining circulation and ad revenues.

Write it, even if that means taking certain liberties with the truth.

Fake news. Sound prescient?

The sub-narrative concerns a love story of a sort, and an exploration of the meaning of miracles and faith.

And fraud.

So that’s the synopsis.

“Paper Boy,” Table of Contents:

-- Chapter One: Market Value.

-- Chapter Two: E.B. White.

-- Chapter Three: Visions.

-- Chapter Four: Live at Six.

-- Chapter Five: Perceived Motion.

-- Chapter Six: Football.

-- Chapter Seven: Sacred Waters.

-- Chapter Eight: The Other Side.

-- Chapter Nine: A Reliable Source.

-- Chapter Ten: Conflicts of Interest.

-- Chapter Eleven: Full Disclosure.

-- Chapter Twelve: Extraordinary Things.

Excerpt from Chapter 12. This scene opens inside The Tribune’s pressroom, as the next day’s edition is about to roll:

We found press foreman Roger Adams standing by the master controls. One of his men was loading the redone page-one plates. Like me, Adams went back a long way with the executive editor.

``I'm sorry about the verdict,'' said Adams. ``What a kick in the teeth, especially on Christmas Eve. If it means anything, I was with you one hundred percent. That son of a bitch got your kid, no question. Not that it don't take balls to stand up to him like you did. I admire you, Bob. It couldn't have been easy testifying.''

``You'd do the same thing in my shoes,'' said Bob. ``Anybody would.''

``Anybody but Poop Man,'' said Adams. Even production hadn't escaped the consultants: Adams had arrived at work yesterday to find he'd lost three of his men.

``And Chamberlain,'' I said. ``Don't forget him.''

``Birds of a feather,'' said Adams. ``Well, looks like we're ready to roll. You staying for the run?''

``At least the first few thousand,'' said Bob.

``You, too, Nick?''

``Me too.''

``By the way,'' said Adams, ``I read your column. Hell of a piece of work. Said a lot of things I've been thinking since the sale. 'Course, your ass is toast the second I hit this button.''

``Actually, my ass already is toast,'' I said. ``So is Bob's. We got fired.''

``I'm sorry,'' said Adams.

``For what?'' said Bob. ``My only regret is Hill will be in surgery when this hits the streets. What I wouldn't give to see the look on his face.''

``Press time, boys,'' Adams said. ``Maybe you'd like to start 'er up, Nick. Or you, Bob.''

``All yours, Bob,'' I said.

Adams passed us ear protectors and safety glasses, then showed Bob the commands on the control panel. Bob worked them and the presses slowly began to turn.

``Sitting in an office all day, you forget the power this thing has,'' said Bob. ``I remember my first job -- Christ, it's almost fifty years ago now. They still had hot type. I'd watch them pour it, then go out in the press room and wait for the first copies. Of course, that press wasn't anywhere near this big, but it still seemed invincible. Maybe I'm old-fashioned, but there's something about this that a monitor can't equal. This is real, not pixels on a screen.''

Adams and his newly-short staff pulled a few copies of the paper off the belts and gave them a quick once-over. Satisfied, they let Bob rev the press up to full speed.

The telephone woke me on Christmas morning. It was eleven o'clock on a raw and foggy day. I'd slept almost twelve hours.

``Hello?'' I said.

It was Courtney.

``I just wanted to wish you Merry Christmas,'' she said.

``Merry Christmas,'' I said.

``You probably didn't expect me to call.''

``I've given up expecting things anymore.''

``For what it's worth, I loved your column. I don't know how you got it in the paper, but congratulations.''

``You don't think I sounded like Chicken Soup for the Soul?''

``Can I be honest -- in a couple of places, yes. But you told the truth. The truth can be devastating.''

``I guess it beats socks,'' I said.

``Your words, not mine.''

``It must be a miracle.''

Courtney laughed. ``Careful,'' she said. ``It's a short trip from profound to sophomoric.''

``Tell me about it.''

``Are you going out there today?''

``I'm not sure,'' I said.

``I think you have to,'' Courtney said. ``You can't just slip quietly into the night after all this.''

She was right. It's one thing to present truths, another to be accountable.

``Will you be there?'' I said.

``Would you like me to?''

``I would.''

``Then maybe I will.''

``Strange mood here today,'' said Officer Maloney as he escorted me through the crowd outside Louise's, which numbered more than twenty thousand, according to the policeman's estimate.

``In what way?'' I said.

``I can't tell if they're happy or sad. Or angry. I seen a lot of people reading your column. I hear a lot of grumbling.''

``What did you think?'' I said.

``Pretty heavy stuff,'' said the cop, ``but you told it from the heart. It's the kind of column you don't see much of anymore.''

``You didn't think the end was silly.''

``Sentimental, maybe,'' the policeman said. ``But not silly. Silly don't make you stop and think like that.''

I could barely make out Louise's house through the fog, but I could see that the shades were drawn and there was no sign of activity except for officers on horses behind the police tape. The authorities had never called out the mounted patrol before.

``Have you seen her today?'' I asked Maloney.

``Only for a second, when I came on duty. She poked her head out and said she might come out later, but not to plan on it. Then she told me not to let anyone in -- not even you. Sorry, Nick. I don't think she liked your column.''

We moved toward the altar, where Mass was underway. The priest was just beginning Communion, and lines were forming for the deacons who assisted him.

I stood to the side, wishing the fog were thicker. I wanted to crawl back behind the First Amendment.

And yet, I was strangely calm as I ascended the altar when the Mass ended. I'd spotted Courtney in the crowd and I noticed that Ethan Cottrill was there, too. Seeing me approach, the priest guided me to the lectern. I tapped the microphone -- and felt the eyes of twenty thousand on me.

``I know many of you have already seen this,'' I said, unfolding today's paper, ``but I wanted to read it to you myself. Then I'll be happy to take questions.''

I cleared my throat and began…

Published on May 24, 2018 03:04

#33Stories: Day 24, "Paper Boy"

#33Stories

No. 24: “Paper Boy: A novel about media, truth and other important things.”

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Excerpt follows this synopsis

Since we’ve been on the topic of newspapers lately, I present “Paper Boy,” subtitled “A Novel About Media, Truth and Other Important Things.”

I wrote this unpublished book several years ago, during the first wave of turmoil that the digital revolution wrought upon the venerable print-journalism industry. Set inside the fictitious Daily Tribune, published in the real city of Boston, it chronicles the journey that popular columnist Nick and colleagues take as the once-proud and Pulitzer-winning paper’s new owners insist that the ridiculous mantra of “Good News Rules” is the key not only to survival but to restored glory.

Meaning, write “good” stuff to balance the “bad” headlines of crime, crooked politics and so forth.

Write “good” stories because that’s what readers and advertisers want, and “Good New Rules” is the key to reversing declining circulation and ad revenues.

Write it, even if that means taking certain liberties with the truth.

Fake news. Sound prescient?

The sub-narrative concerns a love story of a sort, and an exploration of the meaning of miracles and faith.

And fraud.

So that’s the synopsis.

“Paper Boy,” Table of Contents:

-- Chapter One: Market Value.

-- Chapter Two: E.B. White.

-- Chapter Three: Visions.

-- Chapter Four: Live at Six.

-- Chapter Five: Perceived Motion.

-- Chapter Six: Football.

-- Chapter Seven: Sacred Waters.

-- Chapter Eight: The Other Side.

-- Chapter Nine: A Reliable Source.

-- Chapter Ten: Conflicts of Interest.

-- Chapter Eleven: Full Disclosure.

-- Chapter Twelve: Extraordinary Things.

Excerpt from Chapter 12. This scene opens inside The Tribune’s pressroom, as the next day’s edition is about to roll:

We found press foreman Roger Adams standing by the master controls. One of his men was loading the redone page-one plates. Like me, Adams went back a long way with the executive editor.

``I'm sorry about the verdict,'' said Adams. ``What a kick in the teeth, especially on Christmas Eve. If it means anything, I was with you one hundred percent. That son of a bitch got your kid, no question. Not that it don't take balls to stand up to him like you did. I admire you, Bob. It couldn't have been easy testifying.''

``You'd do the same thing in my shoes,'' said Bob. ``Anybody would.''

``Anybody but Poop Man,'' said Adams. Even production hadn't escaped the consultants: Adams had arrived at work yesterday to find he'd lost three of his men.

``And Chamberlain,'' I said. ``Don't forget him.''

``Birds of a feather,'' said Adams. ``Well, looks like we're ready to roll. You staying for the run?''

``At least the first few thousand,'' said Bob.

``You, too, Nick?''

``Me too.''

``By the way,'' said Adams, ``I read your column. Hell of a piece of work. Said a lot of things I've been thinking since the sale. 'Course, your ass is toast the second I hit this button.''

``Actually, my ass already is toast,'' I said. ``So is Bob's. We got fired.''

``I'm sorry,'' said Adams.

``For what?'' said Bob. ``My only regret is Hill will be in surgery when this hits the streets. What I wouldn't give to see the look on his face.''

``Press time, boys,'' Adams said. ``Maybe you'd like to start 'er up, Nick. Or you, Bob.''

``All yours, Bob,'' I said.

Adams passed us ear protectors and safety glasses, then showed Bob the commands on the control panel. Bob worked them and the presses slowly began to turn.

``Sitting in an office all day, you forget the power this thing has,'' said Bob. ``I remember my first job -- Christ, it's almost fifty years ago now. They still had hot type. I'd watch them pour it, then go out in the press room and wait for the first copies. Of course, that press wasn't anywhere near this big, but it still seemed invincible. Maybe I'm old-fashioned, but there's something about this that a monitor can't equal. This is real, not pixels on a screen.''

Adams and his newly-short staff pulled a few copies of the paper off the belts and gave them a quick once-over. Satisfied, they let Bob rev the press up to full speed.

The telephone woke me on Christmas morning. It was eleven o'clock on a raw and foggy day. I'd slept almost twelve hours.

``Hello?'' I said.

It was Courtney.

``I just wanted to wish you Merry Christmas,'' she said.

``Merry Christmas,'' I said.

``You probably didn't expect me to call.''

``I've given up expecting things anymore.''

``For what it's worth, I loved your column. I don't know how you got it in the paper, but congratulations.''

``You don't think I sounded like Chicken Soup for the Soul?''

``Can I be honest -- in a couple of places, yes. But you told the truth. The truth can be devastating.''

``I guess it beats socks,'' I said.

``Your words, not mine.''

``It must be a miracle.''

Courtney laughed. ``Careful,'' she said. ``It's a short trip from profound to sophomoric.''

``Tell me about it.''

``Are you going out there today?''

``I'm not sure,'' I said.

``I think you have to,'' Courtney said. ``You can't just slip quietly into the night after all this.''

She was right. It's one thing to present truths, another to be accountable.

``Will you be there?'' I said.

``Would you like me to?''

``I would.''

``Then maybe I will.''

``Strange mood here today,'' said Officer Maloney as he escorted me through the crowd outside Louise's, which numbered more than twenty thousand, according to the policeman's estimate.

``In what way?'' I said.

``I can't tell if they're happy or sad. Or angry. I seen a lot of people reading your column. I hear a lot of grumbling.''

``What did you think?'' I said.

``Pretty heavy stuff,'' said the cop, ``but you told it from the heart. It's the kind of column you don't see much of anymore.''

``You didn't think the end was silly.''

``Sentimental, maybe,'' the policeman said. ``But not silly. Silly don't make you stop and think like that.''

I could barely make out Louise's house through the fog, but I could see that the shades were drawn and there was no sign of activity except for officers on horses behind the police tape. The authorities had never called out the mounted patrol before.

``Have you seen her today?'' I asked Maloney.

``Only for a second, when I came on duty. She poked her head out and said she might come out later, but not to plan on it. Then she told me not to let anyone in -- not even you. Sorry, Nick. I don't think she liked your column.''

We moved toward the altar, where Mass was underway. The priest was just beginning Communion, and lines were forming for the deacons who assisted him.

I stood to the side, wishing the fog were thicker. I wanted to crawl back behind the First Amendment.

And yet, I was strangely calm as I ascended the altar when the Mass ended. I'd spotted Courtney in the crowd and I noticed that Ethan Cottrill was there, too. Seeing me approach, the priest guided me to the lectern. I tapped the microphone -- and felt the eyes of twenty thousand on me.

``I know many of you have already seen this,'' I said, unfolding today's paper, ``but I wanted to read it to you myself. Then I'll be happy to take questions.''

I cleared my throat and began…

Published on May 24, 2018 03:04

May 23, 2018

#33Stories, Day 23: "An Uncommon Man," a biography

#33Stories

No. 23: “An Uncommon Man: The Life & Times of Senator Claiborne Pell”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Published in 2011 by University Press of New England.

The opening of “An Uncommon Man”:

Prologue: A Cold Winter Day

Dawn had barely broken when the crowd began to build outside Trinity Episcopal Church. A frigid wind blew and snow frosted the Newport, Rhode Island, ground. Police had restricted vehicular traffic to allow passage of the motorcade carrying a former president, the vice president-elect, and dozens of U.S. senators, representatives and other dignitaries who would be arriving. Men in sunglasses with bomb-sniffing dogs patrolled the church grounds, where flags flew at half-mast.

It was Jan. 5, 2009, the day of Senator Claiborne deBorda Pell’s funeral.

Some of those waiting to get inside Trinity Church were members of Newport society, to which Pell and Nuala, his wife of 64 years, had belonged since birth. Some were working-class people who knew Pell as a tall, thin, bespectacled man who once regularly jogged along Bellevue Avenue, greeting strangers and friends that he passed. Some knew him only from the media, where he was sometimes portrayed, not inaccurately, as the capitol’s most eccentric character, as interested in the afterlife and the paranormal as the federal budget. Some knew him mostly from the ballot booth or from programs and policies he’d been instrumental in establishing. First elected in 1960, the year his friend John F. Kennedy captured the White House, Pell served 36 years in the U.S. Senate, 14th longest in history as of that January day. His accomplishments from those six terms touched untold millions of lives.

Pell died at a few minutes past midnight on Jan. 1, five weeks after his 90th birthday and more than a decade after the first symptoms of the Parkinson’s Disease that slowly stole all movement and speech, leaving him a prisoner in his own body. He died, his family with him, at his oceanfront home -- a shingled, single-story house that he personally designed and which stood in modest contrast to Bellevue Avenue mansions and Bailey’s Beach, the exclusive members-only club that has been synonymous with East Coast wealth since the Gilded Age. Pell, whose colonial-era ancestors established enduring wealth from tobacco and land, and Nuala, an heiress to the A&P fortune, belonged to Bailey’s. But the Pells were unflinchingly liberal and Democratic. In the old manufacturing state of Rhode Island, where the American Industrial Revolution was born, blue-collar voters embraced their aristocratic senator with the unconventional mind.

The motorcades passed the waiting crowd, which by 9 a.m. was more than a block long. Former President Bill Clinton stepped out of an SUV and went into the parish hall to await the procession to the church. Vice President-elect Joe Biden and Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, whose malignant brain cancer would claim him that summer, followed Clinton. A bus that met a jet from Washington brought more senators, including Majority Leader Harry Reid and Republicans Richard Lugar and Orrin Hatch. Pell’s civility and even temper during his decades in the Senate earned him the respect of his colleagues. “I always try to let the other fellow have my way,” is how Pell liked to explain his Congressional style. It was the best means, he maintained, to “translate ideas into actions and help people,” as he described the heart of his legislative style. He had learned these philosophies from his father, a minor diplomat and one-term Congressman who had cast an inordinate influence on his only child even after his own death in the first months of John F. Kennedy’s presidency.

The doors to Trinity opened and the crowd went in, filling seats in the loft that had been reserved for the public. The overflow went into the parish hall, to watch the live-broadcast TV feed. Led by their mother, Nuala and Claiborne’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren took seats near the pulpit. The politicians settled in pews across the aisle. The organ played, the choir sang, and six Coast Guardsmen wheeled a mahogany casket draped in white to the front of the church.

From early childhood, Pell had loved the sea, an affection he captured in sailboat drawings and grade-school essays about the joys of being on the water. When he was nine, he took an ocean journey that would influence him in ways a young boy could not have predicted: traveling by luxury liner with his mother and stepfather, he went to Cuba and on through the Panama Canal to California and Hawaii. “It was the most interesting voyage I have ever taken,’’ he wrote, when he was 12, in an essay entitled The Story of My Life. After graduating from college in 1940, more than a year before Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Coast Guard, pointedly remaining in the reserves until mandatory retirement at age 60, when he was nearing the end of his third Senate term.

In the many stories that had accompanied his retirement from the Senate, Pell had named the 1972 Seabed Arms Control treaty, which kept the Cold War nuclear arms race from spreading to the ocean floor by prohibiting the testing or storage of weapons deep undersea, as among his favorite achievements. He pointed also to his National Sea Grant College and Program Act of 1966, which provided unprecedented federal funding of university-based oceanography. And one of his deepest regrets, he said 1996, was in failing to achieve U.S. ratification of the international Law of the Sea Treaty, which establishes ocean boundaries and protects global maritime resources.

In planning his funeral, Pell requested a ceremonial honor guard from his beloved service. The Coast Guard granted his wish -- and added meaning when selecting Pell’s pallbearers. Two of the six had graduated college with the help of Pell Grants, the tuition-assistance program for lower- and middle-income students that Pell called his greatest achievement. Since their inception in 1972, the grants by 2009 had been awarded to more than 115 million recipients. Without them, many could not have earned a college degree.

Kennedy left his wife, Vicki, in their pew and walked slowly to the pulpit.

In his nearly eight-minute eulogy, the last substantial speech the final Kennedy brother would make, Ted talked of Pell’s fortitude when he and Nuala lost two of their grown children. His hands trembling but his voice strong, he spoke of his family’s long relationship with Pell, which began before the Second World War -- and of his own friendship with Pell and their 34 years together in the Senate. He spoke of Pell’s political support for his president brother and his support for his own son, Patrick Kennedy, representative from Rhode Island’s 1st Congressional District, which includes Newport. He recalled the summer tradition of sailing with Vicki on his sailboat, Maya, from Long Island to Newport, enroute to their home in Hyannisport on Cape Cod. During their overnight visits with the Pells, Claiborne, who owned no yacht, relished sailing on Ted’s sailboat Mya, even after Parkinson’s Disease left him in a wheelchair and unable to speak. “The quiet joy of the wind on his face was a site to behold,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy closed with tribute.

“During his brilliant career, he amassed a treasure trove of accomplishments that few will ever match,” Kennedy said, citing the Pell Grants, Pell’s 1965 legislation that established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Seabed Treaty. It was Claiborne Pell who advocated the power of diplomacy before resorting to the power of military might. And it was Claiborne Pell who was an environmentalist long before that was cool. Claiborne Pell was a senator of high character, great decency and fundamental honesty. And that’s why he became the longest serving senator in the history of Rhode Island. He was a senator for our time and for all time. He was an original. He was my friend and I will miss him very much.”

Kennedy returned to his pew and Clinton took the pulpit of the historic old church, which has overlooked Newport Harbor since 1726. Drawing laughter, the former president told of first seeing Pell: in 1964, when he was a freshman at Georgetown University living in a dorm that overlooked the backyard of the Pells’ Washington home.

“I was this goggle-eyed kid from Arkansas. I had never been anywhere or seen anything and here I was in Washington, D.C., and I got to be a voyeur looking down on all the dinner parties of this elegant man. So I got very interested in the Pell family. And I read up on them, you know. And I realized that they were a form of American royalty. I knew that because it took me 29 years and six moths to get in the front door of that house I’d been staring at. When I became president, Senator and Mrs. Pell, who had supported my campaign, invited me in the front door. I received one of Claiborne Pell’s courtly tours of his home, which was like getting a tour of the family history. There were all these relatives he had with wigs on. Where I came from only people who were bald wore wigs. And they weren’t white and curled. It was amazing.

“And even after all those years, I still felt as I did when I was a boy: that there was something almost magical about this man who was born to aristocracy but cared about people like the people I grew up with.”

He cared, too, Clinton said, for the citizens of the world. Clinton spoke of Pell’s belief that together, nations can solve the planet’s problems -- a belief that took root in his childhood travels and solidified in 1945 in San Francisco, where delegates of 50 countries drafted the U.N. Charter. Pell served as an assistant for the American delegation.

“Every time I saw him -- every single time -- he would pull out this dog-eared copy of the U.N.

Charter,’’ Clinton said. “It was light blue, frayed around the edges. I was so intimidated. There I was in the White House and I actually went home one night and read it all again to make sure I could pass a test in case Senator Pell asked me any questions. But I got the message and so did everybody else that ever came in contact with him: that America could not go forward in a world that had only a global economy without a sense of global politics and social responsibility.”

The ex-president ended with a reference to ancestors.

“The Pell family’s wealth began with a royal grant of land in Westchester County where Hilary and I now live,” he said. “It occurred to me that if we had met 300 years ago, he would be my lord and I would be his serf. All I can tell you is: I would have been proud to serve him. He was the right kind of aristocrat: a champion by choice, not circumstance, of the common good and our common future and our common dreams, in a long life of grace, generous spirit, kind heart, and determination, right to the very end. That life is his last true Pell Grant.”

Despite the work of transitioning from the Bush to the Obama administration, Biden had taken the morning off to eulogize the man who befriended him when he arrived in Washington in 1972 as a 29-year-old senator-elect. Biden had just lost his wife and baby daughter in a car accident. “You made your home my own,” Biden said, turning to Nuala. In the Senate, Pell became Biden’s mentor.

The vice-president-elect, who served with Pell on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, enumerated more of Pell’s accomplishments, including legislation that helped build Amtrak and a lesser-publicized campaign against drunk driving -- a cause Pell embraced when two of his staff members, including one central in the fight for Pell Grants, were killed by drunk drivers. In these efforts and in all of his Congressional dealings, Biden said -- and all of his campaigns, none of which he ever lost -- Pell brought a gentlemanly sensibility that seemed outdated in an era of hot tempers and mud.

“I’m told, Ted,” Biden said, “that your brother, President Kennedy, once said Claiborne Pell was the least electable man in America -- a view that, I suppose, was shared by at least six of his opponents when he ran for the United States Senate over the course of 36 years.”

Laughter filled Trinity Church.

“I understand how people could think that,” Biden continued. Here was a graduate of an exclusive college-preparatory school and Princeton, who later earned an advanced degree from another Ivy league School, Columbia -- a man born into wealth who married into more and had traveled the world many times over before ever seeking office.

“He didn’t have a great deal in common, I suspect, with many of his constituents in terms of background, except this: I think Claiborne realized that many of the traits he learned in his upbringing -- honesty, integrity, fair play -- they didn’t only belong to those who could afford to embrace the sense of noblesse oblige. He understood, in my view, that nobility lives in the heart of every man and woman regardless of their situation in life. He understood that the aspirations of the mother living on Bellevue Avenue here in Newport were no more lofty, no more considerable, than the dream of a mother living in an apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant.…each of those mothers wanted their children to have the opportunity to make the most of their gifts and the most of their lives.”

Biden told some favorite stories, drawing laughter with the one about Pell going for a jog on a trip to Rome dressed in an Oxford button-down shirt, Bermuda shorts, black socks and leather shoes -- an image of Pell that his friends and family knew well. Sweat suits and Nikes were not Pell’s style.

“To be honest, he was a quirky guy, Nuala,” Biden said.

The mourners laughed -- Nuala most appreciatively, for she understood best what Biden meant. For two thirds of a century, she had experienced his odd dress, his obsession with ancestors, his bad driving, his frugality, his fascination with ESP and the possibility of life after death, his manner of speaking, as if he had indeed traveled forward in time from the 1600s, when Thomas Pell was named First Lord of the Manor of Pelham. These traits were all part of his charm, which sometimes annoyed but often amused his wife. This and his handsome looks and ever-curious mind were why Nuala had fallen in love when they met in the summer of 1944, when she was 20, and why she married him four months later. Claiborne Pell was different. Unlike most other young men of her circle, he aspired to be something more than a rich guy who threw parties.

Biden’s eulogy was nearing a half hour, but he had one more story.

“One day, I was sitting in the Foreign Relations Committee room waiting for a head of state to come in.” Pell was there.

“He took his jacket off, which was rare -- I can’t remember why -- and I noticed his belt went all the way around the back and it went all the way to the back loop. I looked at him and I said, `Claiborne, that’s an interesting belt.’

“He said, `it was my father’s.’ And his father was a big man.

“I looked at him and I said, `Well, Claiborne, why don’t you just have it cut off?’

“He unleashed the whole belt and held it up and said, `Joe, this is genuine rawhide.’ I’ll never forget that: `This is genuine rawhide.’ I thought, God bless me!”….

Context:

Like some of my other books and two of my documentaries, “An Uncommon Man” grew out of a story I wrote for The Providence Journal, “A Remarkable Life.” We published it in April, 2005, as Pell was nearing the end of his life, his Parkinson’s having robbed him of speech and movement. I have reprinted it below. How fondly I remember the days I spent with Claiborne and Nuala, one of the greatest ever, in their home overlooking the open Atlantic. They came at a moment of deep discontent in my own life, and while I never mentioned that to them, Nuala could sense it. And she was, in an unspoken way, very supportive.

In writing the book after Pell passed, I spent many hours again in that house with Nuala, a tape recorder running – and not running, as we talked and lunched and reminisced. More very fond memories (not to mention such enormous help with “An Uncommon Man,” Nuala held the keys to the kingdom.

The launch party for “An Uncommon Man” was held at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center, and it was on that day that I met center director Jim Ludes. And THAT led to a conversation over coffee in early 2012 that began what became Story in the Public Square, now a weekly PBS and SiriusXM Satellite radio program.

Last note, quite literally. I wrote Nuala’s obituary after she passed in April 2014 at the age of 89. Here’s how it began:

Nuala Pell, longtime patron of the arts, humanities and education, supporter of many causes, prominent philanthropist and the widow of the late Sen. Claiborne Pell, died early Sunday morning at Newport Hospital. She was 89.

Word of her passing prompted an outpouring of tribute.

“An extraordinary woman whose grace and decency infused everything she did and everything Senator Pell did,” is how Sen. Jack Reed remembered her. “She was just a wonderful person.”

“Nuala Pell’s remarkable lifetime of public service left an indelible mark on our state,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse. “Alongside her husband, Senator Claiborne Pell, she was a passionate advocate for the arts and humanities -- and, above all, for the people of our Ocean State.”

'A Remarkable Life' - Nuala and Claiborne Pell reflect on six extraordinary decades together

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: April 10, 2005 Page: E-01 Section: SUNDAY EXTRA Edition: All

NEWPORT - Claiborne deBorda Pell sits in a wheelchair at a table in his seaside home, eating a lunch of lasagna cut into small pieces. Nuala, Pell's wife of 60 years, is seated to his left. She is telling the story of their early days together, when they lived with the first two of their four children in the chaos of postwar Europe.

It is a dreary day in late winter: the sky threatens snow, and the ocean, south of the living room, is an angry gray. To the west, the cabanas at Bailey's Beach Club are all shuttered. The waves roll onto lonely sand, playground for the old-money set on summer days.

Inside the Pell residence, a single-story house so unlike the gilded mansions on nearby Bellevue Avenue, the atmosphere is inviting.

The living room is furnished with upholstered sofas and chairs, and salmon-colored drapes frame the windows. Paintings of relatives and ancestors -- including great-grandfather Eugene deBorda, a Paris-born Basque -- cover the walls. And there is a fireplace, lit every night in cold weather, next to the reclining chair where Claiborne takes his long, daily naps. A 19th-century clock that he inherited from his father chimes on the quarter hour. Nuala winds it once a week.

In 1948, Nuala says, Claiborne was an officer in the U.S. Foreign Service. After spending many months in Prague, he had been assigned to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia. The Pells were there when the Communists took control of the government. "A lot of our friends were put in prison, and a lot of our friends were tortured," Nuala says.

One was Claiborne's interpreter, Andrew Spiro. "One day they kidnapped him and put him in prison and asked him to report on us, and we assumed he would be doing that, so we were very careful. He didn't get out for three months, and he had a terrible time. Am I correct so far, Claiborne?"

Once, Pell possessed a distinctive aristocratic voice - a voice heard in Washington and many overseas capitals during the 36 years he was a U.S. senator, longer than any other Rhode Islander. For more than a decade, Pell chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

But Pell, 86, suffers from Parkinson's disease now, and while his mind remains firm, his memories clear, he can barely whisper.

"Yes," he tells his wife, who is 80.

"You stop me if I'm not," she says.

Nuala continues as Claiborne finishes his lunch assisted by an attendant; with effort, Pell can still get a fork or a glass to his mouth, but the attendant's help is appreciated. Someone is on duty 24 hours a day for the former senator, whose many legislative accomplishments include the Pell Grant college aid program, which has helped millions of needy students.

Nuala finishes her Bratislava tale: in the fall of 1948, they and their two young children departed for a new assignment in Genoa, Italy.

"When we were leaving," Nuala says, "Spiro, who by that time had been released from prison, asked Claiborne if he would take him out of the country. Claiborne said no, he couldn't. However, Claiborne said, 'The trunk of my car will be unlocked.' " Pell succeeded in smuggling his interpreter to freedom.

Lunch ends. An attendant wipes Pell's mouth and straightens his tie, worn with a button-down shirt. Pell stares across the room, his eyes focused on a small painted altar, one of several pieces of furniture -- including the dinner table, with its exquisite inlaid Japanese figures -- that the Pells bought in postwar Europe.

"That was from Romania," Claiborne whispers. It is one of the longest sentences I will hear him say in several visits.

"Wood?" I ask.

"Yes," he says.

"Poor Claiborne," Nuala says. "He's so good about it. He never complains. But it's such a shock if you run all your life -- and he was constantly working and constantly doing things, he never stopped. And to be suddenly trapped in your body. It's horrible."

* * *

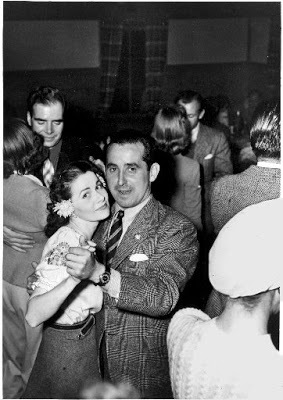

THE DINNER table occupies the corner of the living room near the wing where the children used to sleep. Claiborne sleeps in one of their bedrooms now. On the wall by the door is a painting of Claiborne and Nuala on their wedding day, Dec. 16, 1944.

The young Claiborne is dignified, dark-haired, handsome; he is wearing his Coast Guard uniform, and it lends him an air of quiet authority at age 26. Nuala, who was 20, is beautiful, with a fair complexion and red hair that is a shade darker than strawberry blond. With her necklace of diamond and pearls and her cream-colored satin wedding dress, she looks enchanting.

Although they come from the same old-money world, their families' political views were diametrical.

Claiborne is a descendant of Pierre Lorillard, who founded America's first tobacco company, in 1760. The nation's fourth-largest tobacco firm today, Lorillard sells Newport cigarettes, among other brands. Wealthy though they were, the Pells believed in civic duty: several of Claiborne's relatives served in Congress, and his father, Herbert Claiborne Pell, was not only a U.S. representative from New York (for one term, 1919-1921) but also U.S. minister to Portugal and then Hungary in the 1930s and '40s. Pells were Demo-crats.

Nuala's mother, the former Marie Josephine Hartford, Paris-educated and trained as a concert pianist, belonged to the family that founded The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., the A&P. Unlike Claiborne, Nuala grew up with no sense of noblesse oblige: her parents traveled the high-society circuit, with its Fifth Avenue townhouses, Newport summer homes and pursuit of elegant pleasures. In their world, a dinner party that set Bailey's Beach abuzz was a crowning achievement.

Even before meeting Pell, Nuala found that existence lacking.

"I didn't really agree with my parents' way of life; it seemed so superficial. That's not to say that I did not enjoy it -- I had a ball. But I thought Claiborne had it all right. I believed in what he believed in. Plus, I found him enormously attractive."

Did Claiborne find Nuala attractive, too?

"Yes," he says.

"He wouldn't have married me otherwise!"

And there was something else that Pell promised Nuala, something most other bachelors from her set could not provide.

"I thought it would be an interesting life with him. And it has been. I mean, look at what we've done."

* * *

THEY MET at a cocktail party in Newport one evening in the early summer of 1944. Nuala was a student at Bennington College, in Vermont, and Claiborne, a Coast Guard lieutenant, had been sent home from the Mediterranean Theater to recover from a bacterial infection, contracted from consuming unpasteurized cheese or milk.

"We met again at the beach the next day," says Nuala, beckoning toward Bailey's Beach Club. "And then we saw each other in July and August. We got engaged in what -- September, I think -- and married in December. It was very quick, the whole thing." Whirlwind romances abounded in wartime America.

The engagement was announced that fall, and it made all the New York and Washington papers. After rummaging through the house, Nuala finds a scrapbook chronicling the engagement and wedding, and also her wedding album. Both are bound in red leather and emblazoned in gold.

A few days later, as Claiborne sleeps under a blanket in his reclining chair, she opens them up. The fireplace clock chimes 11:15 a.m. "It's a very ornery clock," Nuala says. "It used to run fast -- and now, I haven't fixed it, it runs slow. So I have to push it forward."

The clippings are yellowed, the scrapbooks dog-eared, and some have lost their covers. But they provide details of the Pells' story that memory alone cannot.

"Most of '400' to See Nuala O'Donnell Wed," was the headline in the New York News in November 1944. "Half of Newport, most of Tuxedo Park, a large delegation from Aiken, and many of the fashionable Long Island set are expected to make tracks Manhattanward a week from next Saturday," the story read. "It's the day that the pretty A&P heiress Nuala O'Donnell has set for her marriage to the blue-blooded Lieut. Claiborne Pell of the Coast Guard."

A Journal-American society writer predicted that Dec. 16 would be "THE social star-studded wedding of the season. Nuala, who has just come down from Bennington, where she finished this semester's studies, is brightening Gotham's dark nights with the glow in her eyes, as she goes about the titillating business of completing plans down to the last orange blossom."

The Pells were married in St. James Episcopal Church on New York's Madison Avenue, with a reception at the St. Regis Hotel, built by another person tied to Newport, John Jacob Astor IV. The scrapbook contains mementos from the day: a folded wedding cake box with white bow; samples of the fabric of Nuala's satin gown, and of the pink taffeta that her bridesmaids wore; and petals from a bouquet of 36 roses sent by President and Mrs. Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The clippings confirmed the society writers' predictions. "There were enough mink coats on view to envelop the globe," one noted.

Nuala thumbs through her wedding album. "There's my mother and stepfather; Claiborne's father." She speaks matter-of-factly. She seems more concerned by the condition of the albums than their content. "I'm sorry they're in such bad shape. I have to get these scrapbooks fixed."

* * *

THE PELLS honeymooned at Pellbridge, an estate that Pell's father owned in Dutchess County, N.Y. In early 1945, the Coast Guard assigned Pell to Princeton University. On Feb. 14, they exchanged their first Valentine's Day cards. Claiborne's to Nuala was hand-drawn. It showed an arrow through a heart, and a man on bended knee offering flowers to his sweetheart.

"Had you started teaching then or were they training you?" Nuala asks.

On this visit, Claiborne is awake.

"I was teaching then," he says. He taught military government.

Nuala says: "We lived in a tiny, tiny house with one room upstairs and one room downstairs. Einstein lived next door. I didn't know anything. I didn't know how to cook, I didn't know how to balance my checkbook. And guess who taught me to balance my checkbook? Einstein. Isn't that wonderful?"

* * *

PELL SPENT the late 1940s and 1950s in the Foreign Service, the State Department and in private business. He worked on voter registration for the national Democratic Party, and he was active with the Rhode Island Democratic State Committee. He gave speeches about his experiences behind the Iron Curtain and the lessons that could be drawn. The Brown Daily Herald's coverage of one of his talks, at Brown University, includes a photo of him with mustache and bow tie.

But Pell was an unlikely candidate to replace the retiring Sen. Theodore Francis Green: he had been a loyal party soldier but had never held elective office.

Pell declared his candidacy in April 1960 with newspaper ads urging voters to "Think Well. Think Pell." A full-page ad in The Providence Evening Bulletin gave his biography, noting his wartime duty -- "he started out as a ship's cook and rose through the ranks to lieutenant" -- his Foreign Service experiences, his support of Newport's Touro Synagogue, and his family's membership in Trinity Episcopal Church. The ad revealed that the Pells spoke French and Italian -- and also that Claiborne was a "forward-thinking Democrat" who had "worked closely" with the AFL/CIO and been an alternate delegate to the 1956 National Democratic Convention.

With Nuala helping on the campaign, Pell won. It was the beginning of a political career without parallel in Rhode Island history.

"The Pell Record," a pamphlet of accomplishments published in 1990, when the senator ran for reelection the final time, numbers 53 pages; a 1994 update adds 13 pages more. Legislation that he wrote or supported concerned economic development (four pages), energy (four pages), veterans (two pages), women's issues (four pages), oceans and fishing (two pages), crime and drugs (two pages), transportation (two pages), and health care (four pages).

Pell was instrumental in the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and he championed the cause of high-speed rail service, especially in the Northeast (he always traveled to and from Washington by train).

His postwar experiences served him well: from his seat on the Foreign Relations Committee, he played an influential role in arms control, human rights, and protection of the global environment, among other international issues.

One of Nuala's scrapbooks from their early years in Washington has several photographs of the Pells at parties and on a yacht with President and Jacqueline Kennedy, who spent much of her childhood in Newport and was married there. Several of the Pells' Christmas cards show the family by the fireplace at Pelican Ledge, their Newport house, which Nuala labeled "the Homestead." And there are photographs of the Pells in Burma, Thailand and India.

What other countries have they visited in their 60 years together?

"Oh, God," Nuala says. She names some two dozen nations on every continent but Antarctica. But she knows she has left many out. "Where else have we been, Claiborne?" she says.

"Liechtenstein."

"Liechtenstein, yes. We spent a lot of time in Liechtenstein."

Which Senate achievement ranks highest on Pell's list?

A finger on his right hand begins to twitch, as it does when he concentrates, and he looks slowly around the room. Thirty seconds pass without him speaking.

"Banning nuclear weapons on the floor of the sea?" Nuala says. "The Pell grants?"

Claiborne clears his throat and whispers: "I think the Pell grants."

* * *

PARKINSON'S arrived with a soft touch.

"What were the first symptoms, Claiborne?" Nuala says.

He doesn't answer.

"I think a couple of people in the office noticed that he was sort of slowing down," Nuala says. And he was walking stooped. It was 1994, and Pell was 75. Perhaps it was his age.

"I remember on our wedding anniversary in 1994, which was our 50th. We had a dinner party here, and I was sitting next to [then-Gov.] Bruce Sundlun, and he said: 'Nuala, you have to do something. Claiborne's obviously got something wrong with him. He has trouble speaking, his voice is going. Get him to a doctor.' "

Soon afterward, a Georgetown University Hospital neurologist made the diagnosis of Parkinson's, an incurable disease of the central nervous system. "He has a peculiar kind," Nuala says. "He doesn't have the shaky kind; he has the kind that gets you all stiff and makes it difficult to talk and swallow."

At first, Pell refused to accept his illness. "I still resist it," he said in April 1995, in The Journal story that broke the news.

Gradually, though, the reality became inescapable.

"It was very slow," Nuala says. "At first, he couldn't tie his tie -- so Bertie, our oldest son, got all his ties and tied them for him -- looped them so he could get them over his head. It was wonderful."

With the help of staff, Pell still occasionally gets out: for doctors' visits, and to attend lectures and political and educational fundraisers. He likes the movies.

"I did take him to see Hotel Rwanda the other day -- it's a wonderful movie. And he thought it was wonderful, too. But we have to go to movies that are on the ground floor that we can get the wheelchair in."

Mostly now, though, Claiborne's world is his home.

* * *

TO REACH the Pells', you travel most of Bellevue Avenue and turn left onto a street that delivers you to a narrow, bumpy road.

One branch leads to The Waves, the mansion built by the eminent architect John Russell Pope -- and owned by Nuala's mother for a decade or so in the mid-20th century. The other branch takes you to Pelican Ledge, as the Pell residence is known in the Green Book, the private guide to the Newport elite.

Pelican Ledge is built of wood, with weathered shingle siding, white trim, and Swiss-blue shutters. Ramps have been built over the slate stairs so that Claiborne can be wheeled out to his car, a 1997 Mercury Sable, and lifted into the front seat on those occasions he leaves home. The Pells have bird feeders and birdbaths -- one with a heater to keep it ice-free.

"We have cardinals, we have ducks, we have a lady coyote who is in love with the German shepherd next door -- she thinks he's a coyote," Nuala says.

Rusted iron pelicans serve as lawn decorations. A pelican is on the Pell coat of arms, but Nuala is not particularly impressed. "There are pelicans in all our cars, there are pelicans all over the place. I've had enough of them! So has my daughter-in-law -- she won't have one in the house." Nuala laughs. She has always indulged her husband's little obsession with his English ancestry.

When Nuala's mother sold The Waves, in 1952, she divided an acre off the estate and gave it to her daughter and son-in-law. Through all their travels and all their years in Washington, the house they built 53 years ago on that acre has remained home. It is where the extended Pell family has summered, spent holidays, and celebrated the milestones in their lives.

Now, Claiborne's days begin at 7 or 8, when an attendant dresses him and helps with breakfast. He usually naps the rest of the morning, in his chair by the fireplace, while Nuala runs errands or goes to the gym. He returns to the table for lunch, and then seeks the comfort again of his chair.

"The afternoon can be boring," Nuala says. "We read the papers to him, and if we don't go out, we have dinner here, too. If there's anything interesting on television, we watch it."

Christopher T.H. Pell, N. Dallas Pell, and Julia L. Pell, three of Claiborne's and Nuala's four children, are frequent visitors to Pelican Ledge -- as are the Pells' five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. A fourth is due in June. "I'm thrilled!" Nuala says. "It's going to be a girl."

Photos of the Pells' firstborn, Herbert C. Pell III -- Bertie -- as a baby fill pages of one of Nuala's scrapbooks. One shows Nuala in the fall of 1945 with her "first lesson in diaper pinning." Others show Claiborne cradling his son. Baby Bertie's first passport photo is there, too.

In 1999, Bertie died of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, a type of cancer, at age 54.

Nuala remembers a letter that Jackie Onassis wrote to them after she was diagnosed with the disease. "She said: 'What is this disease that both Bertie and I have?' [Jackie] got it later than Bertie, and she died so quickly."

Diagnosed in 1993, Bertie was in remission for three years, and then the cancer returned. "He'd gone to the boat show, if you can believe this, two or three days before he died, and bought a boat. He was the optimist of all time. Then he caught a cold in his good lung, and his other lung had been radiated to pieces, so there was no way that he could survive."

* * *

WHILE NUALA was in Washington, she served on several political committees. She worked on all of her husband's campaigns. She served on the board of Roger Williams University, Newport's Redwood Library and the John A. Hartford Foundation, a family charity that champions health care. She is currently on the board of Salve Regina University. And she has other civic interests, including preservation, cancer prevention, and the Newport International Film Festival.

She also runs the household, as she has since Albert Einstein taught her the intricacies of a checkbook. Her office is in the front of the house: it's a small, cozy room, with rust-colored curtains and many photographs and paintings. Her desk is piled with papers and bills. She uses a laptop computer, although not as deftly as she'd like. "I'm going to have to take a course, I think, because it takes forever," she says.

Nuala's bedroom is past the front hall, where she's hung the only painting done of the Pells when Claiborne was a senator. Nuala's room is predominantly blue, with an exposed beam ceiling and grand views of the open Atlantic. A pillow embroidered "Happiness is being married to your best friend" lies on a chair. A life-size painting of Nuala's mother, Nuala's brother and Nuala when she was a young teenager occupies the space behind her bed.

"It's interesting because Mother is holding a portrait of the painter and I'm holding a scrapbook which is open at a photograph of the painting," she says. "Now come follow me."

We walk to the eastern-most end of the house, the end facing The Waves, into a room filled with tools and brushes and buckets of yellow paint.

"This was Claiborne's office, which, when he was elected to the Senate, we added on. Everything was blue and white in here, and there were bookcases and everything. But obviously he can't use any of it anymore, so it's all gone to [Salve Regina's] Pell Center or URI."

The workers have added new bookcases, and Nuala plans to outfit the room with a queen-size sofa bed and an 18th-century clock and black furniture that was in their Georgetown house during the Pells' Washington days. "This is a spectacular room in the summer," she says. "I'm going to call it a garden room."

Nuala expects that her husband will spend hours in it, and also on the terrace that the workers have built outside the sliding glass doors.

"I've added this little terrace because the wind doesn't hit here the way it does the other terrace. I think it's going to be lovely for Claiborne because he'll be able to get outside with a little ramp here, and we have two wonderful chairs that he can sit in."

But Claiborne has not seen the terrace or his redone office yet, although he knows construction is under way.

"I thought I'd wait until it's done because otherwise he might be too upset with the loss of his office completely," Nuala says.

* * *

ON YET another visit to Pelican Ledge, the sky is clear but for a few high clouds. The sea is deep blue and whitecapped. Sun floods the southern windows, catching Claiborne and Nuala at their table.

Nuala remains a beautiful woman, with fair skin and chin-length white hair that she keeps straight. "I tried to streak it when it started to go gray," she says, "but I was never able to get the same colors so I gave up." But like pearls, white hair becomes her.

Claiborne's hair is thinner than a decade ago, but his face retains its patrician lines. He wears a sweater over an Oxford button-down shirt this day, though no tie. He is freshly shaved. Behind his glasses, his eyes have an unmistakable intensity. At this moment, he doesn't look radically different from when he left public office almost 10 years ago.

"It's so maddening," Nuala says. At this moment, it's easy to imagine Pell addressing a favorite issue back on the Senate floor.

"Parkinson's can sink you into deep depression," Nuala says. "But not Claiborne. He's been very accepting, which is amazing to me."

Claiborne attempts to speak, but no words come out.

"Are you trying to say something?"

Claiborne doesn't answer.

Nuala says that while her husband does not bemoan his condition, he is not reticent, either.

"Claiborne is extremely strong-minded, as all the people who look after him who've been with us for some time have found: if he doesn't want to do something, he doesn't do it. And I notice, Claiborne, that when you get mad, you can yell at somebody. Oh, yes: if he needs something and nobody's paying attention, you'll hear about it. But he's [generally] very uncomplaining."

She's accepting.

"We've had a remarkable life, really. I must say I was looking forward to even more trips after we got out of the Senate and doing a lot of things, but be that as it may; it doesn't matter. We're really lucky because all our children live around here, or basically around here, and most of our grandchildren, too. We have a lot of family around."

The sun warms Nuala's hands, and I notice her wedding ring, a thin gold band that her husband placed on her finger in a New York church so long ago. Claiborne is not wearing his: he was never big on jewelry, and for more than 60 years, Nuala has kept his ring in her jewelry box.

"He said he'd be willing to wear it now," Nuala says.

She takes her husband's hand and holds it gently.

"But I wouldn't do that to your fingers. They're all curled up."

No. 23: “An Uncommon Man: The Life & Times of Senator Claiborne Pell”

Context at the end of this excerpt.

Other entries in #33Stories at the Table of Contents. See you tomorrow!

Published in 2011 by University Press of New England.

The opening of “An Uncommon Man”:

Prologue: A Cold Winter Day

Dawn had barely broken when the crowd began to build outside Trinity Episcopal Church. A frigid wind blew and snow frosted the Newport, Rhode Island, ground. Police had restricted vehicular traffic to allow passage of the motorcade carrying a former president, the vice president-elect, and dozens of U.S. senators, representatives and other dignitaries who would be arriving. Men in sunglasses with bomb-sniffing dogs patrolled the church grounds, where flags flew at half-mast.

It was Jan. 5, 2009, the day of Senator Claiborne deBorda Pell’s funeral.

Some of those waiting to get inside Trinity Church were members of Newport society, to which Pell and Nuala, his wife of 64 years, had belonged since birth. Some were working-class people who knew Pell as a tall, thin, bespectacled man who once regularly jogged along Bellevue Avenue, greeting strangers and friends that he passed. Some knew him only from the media, where he was sometimes portrayed, not inaccurately, as the capitol’s most eccentric character, as interested in the afterlife and the paranormal as the federal budget. Some knew him mostly from the ballot booth or from programs and policies he’d been instrumental in establishing. First elected in 1960, the year his friend John F. Kennedy captured the White House, Pell served 36 years in the U.S. Senate, 14th longest in history as of that January day. His accomplishments from those six terms touched untold millions of lives.

Pell died at a few minutes past midnight on Jan. 1, five weeks after his 90th birthday and more than a decade after the first symptoms of the Parkinson’s Disease that slowly stole all movement and speech, leaving him a prisoner in his own body. He died, his family with him, at his oceanfront home -- a shingled, single-story house that he personally designed and which stood in modest contrast to Bellevue Avenue mansions and Bailey’s Beach, the exclusive members-only club that has been synonymous with East Coast wealth since the Gilded Age. Pell, whose colonial-era ancestors established enduring wealth from tobacco and land, and Nuala, an heiress to the A&P fortune, belonged to Bailey’s. But the Pells were unflinchingly liberal and Democratic. In the old manufacturing state of Rhode Island, where the American Industrial Revolution was born, blue-collar voters embraced their aristocratic senator with the unconventional mind.

The motorcades passed the waiting crowd, which by 9 a.m. was more than a block long. Former President Bill Clinton stepped out of an SUV and went into the parish hall to await the procession to the church. Vice President-elect Joe Biden and Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, whose malignant brain cancer would claim him that summer, followed Clinton. A bus that met a jet from Washington brought more senators, including Majority Leader Harry Reid and Republicans Richard Lugar and Orrin Hatch. Pell’s civility and even temper during his decades in the Senate earned him the respect of his colleagues. “I always try to let the other fellow have my way,” is how Pell liked to explain his Congressional style. It was the best means, he maintained, to “translate ideas into actions and help people,” as he described the heart of his legislative style. He had learned these philosophies from his father, a minor diplomat and one-term Congressman who had cast an inordinate influence on his only child even after his own death in the first months of John F. Kennedy’s presidency.

The doors to Trinity opened and the crowd went in, filling seats in the loft that had been reserved for the public. The overflow went into the parish hall, to watch the live-broadcast TV feed. Led by their mother, Nuala and Claiborne’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren took seats near the pulpit. The politicians settled in pews across the aisle. The organ played, the choir sang, and six Coast Guardsmen wheeled a mahogany casket draped in white to the front of the church.

From early childhood, Pell had loved the sea, an affection he captured in sailboat drawings and grade-school essays about the joys of being on the water. When he was nine, he took an ocean journey that would influence him in ways a young boy could not have predicted: traveling by luxury liner with his mother and stepfather, he went to Cuba and on through the Panama Canal to California and Hawaii. “It was the most interesting voyage I have ever taken,’’ he wrote, when he was 12, in an essay entitled The Story of My Life. After graduating from college in 1940, more than a year before Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Coast Guard, pointedly remaining in the reserves until mandatory retirement at age 60, when he was nearing the end of his third Senate term.

In the many stories that had accompanied his retirement from the Senate, Pell had named the 1972 Seabed Arms Control treaty, which kept the Cold War nuclear arms race from spreading to the ocean floor by prohibiting the testing or storage of weapons deep undersea, as among his favorite achievements. He pointed also to his National Sea Grant College and Program Act of 1966, which provided unprecedented federal funding of university-based oceanography. And one of his deepest regrets, he said 1996, was in failing to achieve U.S. ratification of the international Law of the Sea Treaty, which establishes ocean boundaries and protects global maritime resources.

In planning his funeral, Pell requested a ceremonial honor guard from his beloved service. The Coast Guard granted his wish -- and added meaning when selecting Pell’s pallbearers. Two of the six had graduated college with the help of Pell Grants, the tuition-assistance program for lower- and middle-income students that Pell called his greatest achievement. Since their inception in 1972, the grants by 2009 had been awarded to more than 115 million recipients. Without them, many could not have earned a college degree.

Kennedy left his wife, Vicki, in their pew and walked slowly to the pulpit.

In his nearly eight-minute eulogy, the last substantial speech the final Kennedy brother would make, Ted talked of Pell’s fortitude when he and Nuala lost two of their grown children. His hands trembling but his voice strong, he spoke of his family’s long relationship with Pell, which began before the Second World War -- and of his own friendship with Pell and their 34 years together in the Senate. He spoke of Pell’s political support for his president brother and his support for his own son, Patrick Kennedy, representative from Rhode Island’s 1st Congressional District, which includes Newport. He recalled the summer tradition of sailing with Vicki on his sailboat, Maya, from Long Island to Newport, enroute to their home in Hyannisport on Cape Cod. During their overnight visits with the Pells, Claiborne, who owned no yacht, relished sailing on Ted’s sailboat Mya, even after Parkinson’s Disease left him in a wheelchair and unable to speak. “The quiet joy of the wind on his face was a site to behold,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy closed with tribute.

“During his brilliant career, he amassed a treasure trove of accomplishments that few will ever match,” Kennedy said, citing the Pell Grants, Pell’s 1965 legislation that established the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Seabed Treaty. It was Claiborne Pell who advocated the power of diplomacy before resorting to the power of military might. And it was Claiborne Pell who was an environmentalist long before that was cool. Claiborne Pell was a senator of high character, great decency and fundamental honesty. And that’s why he became the longest serving senator in the history of Rhode Island. He was a senator for our time and for all time. He was an original. He was my friend and I will miss him very much.”

Kennedy returned to his pew and Clinton took the pulpit of the historic old church, which has overlooked Newport Harbor since 1726. Drawing laughter, the former president told of first seeing Pell: in 1964, when he was a freshman at Georgetown University living in a dorm that overlooked the backyard of the Pells’ Washington home.

“I was this goggle-eyed kid from Arkansas. I had never been anywhere or seen anything and here I was in Washington, D.C., and I got to be a voyeur looking down on all the dinner parties of this elegant man. So I got very interested in the Pell family. And I read up on them, you know. And I realized that they were a form of American royalty. I knew that because it took me 29 years and six moths to get in the front door of that house I’d been staring at. When I became president, Senator and Mrs. Pell, who had supported my campaign, invited me in the front door. I received one of Claiborne Pell’s courtly tours of his home, which was like getting a tour of the family history. There were all these relatives he had with wigs on. Where I came from only people who were bald wore wigs. And they weren’t white and curled. It was amazing.

“And even after all those years, I still felt as I did when I was a boy: that there was something almost magical about this man who was born to aristocracy but cared about people like the people I grew up with.”

He cared, too, Clinton said, for the citizens of the world. Clinton spoke of Pell’s belief that together, nations can solve the planet’s problems -- a belief that took root in his childhood travels and solidified in 1945 in San Francisco, where delegates of 50 countries drafted the U.N. Charter. Pell served as an assistant for the American delegation.

“Every time I saw him -- every single time -- he would pull out this dog-eared copy of the U.N.

Charter,’’ Clinton said. “It was light blue, frayed around the edges. I was so intimidated. There I was in the White House and I actually went home one night and read it all again to make sure I could pass a test in case Senator Pell asked me any questions. But I got the message and so did everybody else that ever came in contact with him: that America could not go forward in a world that had only a global economy without a sense of global politics and social responsibility.”

The ex-president ended with a reference to ancestors.

“The Pell family’s wealth began with a royal grant of land in Westchester County where Hilary and I now live,” he said. “It occurred to me that if we had met 300 years ago, he would be my lord and I would be his serf. All I can tell you is: I would have been proud to serve him. He was the right kind of aristocrat: a champion by choice, not circumstance, of the common good and our common future and our common dreams, in a long life of grace, generous spirit, kind heart, and determination, right to the very end. That life is his last true Pell Grant.”

Despite the work of transitioning from the Bush to the Obama administration, Biden had taken the morning off to eulogize the man who befriended him when he arrived in Washington in 1972 as a 29-year-old senator-elect. Biden had just lost his wife and baby daughter in a car accident. “You made your home my own,” Biden said, turning to Nuala. In the Senate, Pell became Biden’s mentor.

The vice-president-elect, who served with Pell on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, enumerated more of Pell’s accomplishments, including legislation that helped build Amtrak and a lesser-publicized campaign against drunk driving -- a cause Pell embraced when two of his staff members, including one central in the fight for Pell Grants, were killed by drunk drivers. In these efforts and in all of his Congressional dealings, Biden said -- and all of his campaigns, none of which he ever lost -- Pell brought a gentlemanly sensibility that seemed outdated in an era of hot tempers and mud.

“I’m told, Ted,” Biden said, “that your brother, President Kennedy, once said Claiborne Pell was the least electable man in America -- a view that, I suppose, was shared by at least six of his opponents when he ran for the United States Senate over the course of 36 years.”

Laughter filled Trinity Church.

“I understand how people could think that,” Biden continued. Here was a graduate of an exclusive college-preparatory school and Princeton, who later earned an advanced degree from another Ivy league School, Columbia -- a man born into wealth who married into more and had traveled the world many times over before ever seeking office.

“He didn’t have a great deal in common, I suspect, with many of his constituents in terms of background, except this: I think Claiborne realized that many of the traits he learned in his upbringing -- honesty, integrity, fair play -- they didn’t only belong to those who could afford to embrace the sense of noblesse oblige. He understood, in my view, that nobility lives in the heart of every man and woman regardless of their situation in life. He understood that the aspirations of the mother living on Bellevue Avenue here in Newport were no more lofty, no more considerable, than the dream of a mother living in an apartment in Bedford-Stuyvesant.…each of those mothers wanted their children to have the opportunity to make the most of their gifts and the most of their lives.”

Biden told some favorite stories, drawing laughter with the one about Pell going for a jog on a trip to Rome dressed in an Oxford button-down shirt, Bermuda shorts, black socks and leather shoes -- an image of Pell that his friends and family knew well. Sweat suits and Nikes were not Pell’s style.

“To be honest, he was a quirky guy, Nuala,” Biden said.

The mourners laughed -- Nuala most appreciatively, for she understood best what Biden meant. For two thirds of a century, she had experienced his odd dress, his obsession with ancestors, his bad driving, his frugality, his fascination with ESP and the possibility of life after death, his manner of speaking, as if he had indeed traveled forward in time from the 1600s, when Thomas Pell was named First Lord of the Manor of Pelham. These traits were all part of his charm, which sometimes annoyed but often amused his wife. This and his handsome looks and ever-curious mind were why Nuala had fallen in love when they met in the summer of 1944, when she was 20, and why she married him four months later. Claiborne Pell was different. Unlike most other young men of her circle, he aspired to be something more than a rich guy who threw parties.

Biden’s eulogy was nearing a half hour, but he had one more story.

“One day, I was sitting in the Foreign Relations Committee room waiting for a head of state to come in.” Pell was there.

“He took his jacket off, which was rare -- I can’t remember why -- and I noticed his belt went all the way around the back and it went all the way to the back loop. I looked at him and I said, `Claiborne, that’s an interesting belt.’

“He said, `it was my father’s.’ And his father was a big man.

“I looked at him and I said, `Well, Claiborne, why don’t you just have it cut off?’

“He unleashed the whole belt and held it up and said, `Joe, this is genuine rawhide.’ I’ll never forget that: `This is genuine rawhide.’ I thought, God bless me!”….

Context:

Like some of my other books and two of my documentaries, “An Uncommon Man” grew out of a story I wrote for The Providence Journal, “A Remarkable Life.” We published it in April, 2005, as Pell was nearing the end of his life, his Parkinson’s having robbed him of speech and movement. I have reprinted it below. How fondly I remember the days I spent with Claiborne and Nuala, one of the greatest ever, in their home overlooking the open Atlantic. They came at a moment of deep discontent in my own life, and while I never mentioned that to them, Nuala could sense it. And she was, in an unspoken way, very supportive.

In writing the book after Pell passed, I spent many hours again in that house with Nuala, a tape recorder running – and not running, as we talked and lunched and reminisced. More very fond memories (not to mention such enormous help with “An Uncommon Man,” Nuala held the keys to the kingdom.

The launch party for “An Uncommon Man” was held at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center, and it was on that day that I met center director Jim Ludes. And THAT led to a conversation over coffee in early 2012 that began what became Story in the Public Square, now a weekly PBS and SiriusXM Satellite radio program.

Last note, quite literally. I wrote Nuala’s obituary after she passed in April 2014 at the age of 89. Here’s how it began:

Nuala Pell, longtime patron of the arts, humanities and education, supporter of many causes, prominent philanthropist and the widow of the late Sen. Claiborne Pell, died early Sunday morning at Newport Hospital. She was 89.

Word of her passing prompted an outpouring of tribute.

“An extraordinary woman whose grace and decency infused everything she did and everything Senator Pell did,” is how Sen. Jack Reed remembered her. “She was just a wonderful person.”

“Nuala Pell’s remarkable lifetime of public service left an indelible mark on our state,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse. “Alongside her husband, Senator Claiborne Pell, she was a passionate advocate for the arts and humanities -- and, above all, for the people of our Ocean State.”

'A Remarkable Life' - Nuala and Claiborne Pell reflect on six extraordinary decades together

G. WAYNE MILLER

Publication Date: April 10, 2005 Page: E-01 Section: SUNDAY EXTRA Edition: All

NEWPORT - Claiborne deBorda Pell sits in a wheelchair at a table in his seaside home, eating a lunch of lasagna cut into small pieces. Nuala, Pell's wife of 60 years, is seated to his left. She is telling the story of their early days together, when they lived with the first two of their four children in the chaos of postwar Europe.

It is a dreary day in late winter: the sky threatens snow, and the ocean, south of the living room, is an angry gray. To the west, the cabanas at Bailey's Beach Club are all shuttered. The waves roll onto lonely sand, playground for the old-money set on summer days.

Inside the Pell residence, a single-story house so unlike the gilded mansions on nearby Bellevue Avenue, the atmosphere is inviting.

The living room is furnished with upholstered sofas and chairs, and salmon-colored drapes frame the windows. Paintings of relatives and ancestors -- including great-grandfather Eugene deBorda, a Paris-born Basque -- cover the walls. And there is a fireplace, lit every night in cold weather, next to the reclining chair where Claiborne takes his long, daily naps. A 19th-century clock that he inherited from his father chimes on the quarter hour. Nuala winds it once a week.

In 1948, Nuala says, Claiborne was an officer in the U.S. Foreign Service. After spending many months in Prague, he had been assigned to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia. The Pells were there when the Communists took control of the government. "A lot of our friends were put in prison, and a lot of our friends were tortured," Nuala says.

One was Claiborne's interpreter, Andrew Spiro. "One day they kidnapped him and put him in prison and asked him to report on us, and we assumed he would be doing that, so we were very careful. He didn't get out for three months, and he had a terrible time. Am I correct so far, Claiborne?"

Once, Pell possessed a distinctive aristocratic voice - a voice heard in Washington and many overseas capitals during the 36 years he was a U.S. senator, longer than any other Rhode Islander. For more than a decade, Pell chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

But Pell, 86, suffers from Parkinson's disease now, and while his mind remains firm, his memories clear, he can barely whisper.

"Yes," he tells his wife, who is 80.

"You stop me if I'm not," she says.

Nuala continues as Claiborne finishes his lunch assisted by an attendant; with effort, Pell can still get a fork or a glass to his mouth, but the attendant's help is appreciated. Someone is on duty 24 hours a day for the former senator, whose many legislative accomplishments include the Pell Grant college aid program, which has helped millions of needy students.

Nuala finishes her Bratislava tale: in the fall of 1948, they and their two young children departed for a new assignment in Genoa, Italy.

"When we were leaving," Nuala says, "Spiro, who by that time had been released from prison, asked Claiborne if he would take him out of the country. Claiborne said no, he couldn't. However, Claiborne said, 'The trunk of my car will be unlocked.' " Pell succeeded in smuggling his interpreter to freedom.

Lunch ends. An attendant wipes Pell's mouth and straightens his tie, worn with a button-down shirt. Pell stares across the room, his eyes focused on a small painted altar, one of several pieces of furniture -- including the dinner table, with its exquisite inlaid Japanese figures -- that the Pells bought in postwar Europe.