G. Wayne Miller's Blog, page 24

April 15, 2014

The shade of a copper beech

While writing The Providence Journal feature "A Remarkable Life" and the biography An Uncommon Man about Nuala and Claiborne Pell -- and on numerous other occasions -- I spent many hours with this wonderful woman who died on April 13. Fittingly, I wrote Nuala's obituary.This was one of many memorable occasions with Nuala, and it became the epilogue of my biography. I will have more memories to share soon. The sun was breaking through an overcast sky as Nuala Pell left her home and rode down Bellevue Avenue past her father-in-law’s former estate, now the headquarters of the Preservation Society of Newport County. A writer was at the wheel.It was Veterans Day, 2009.The car passed the Tennis Hall of Fame and First Beach and continued into Middletown. St. George’s School came into view as the car traveled past Hanging Rock, a massive outcropping of ledge in the woods below the school that has been a favorite destination for generations of young people. A memory brought a smile to Nuala’s face. In the summer of 1944, not long after they met, Claiborne took her on a date here, Nuala said. The writer suggested that perhaps the 25-year-old suitor was proud to point out his alma mater. Nuala laughed.“He wasn’t talking about St. George’s,” she said. North on Indian Avenue the car continued, past Eastover, where Claiborne spent part of his childhood with his mother and stepfather. The car turned off at Saint Columba’s Chapel, a stone church built during the 19th Century in old-English style. Ten months before, Pell’s final worldly journey had ended here. His family had gathered around a freshly opened grave beneath a grand old copper beech tree as Episcopal Bishop Geralyn Wolf led them in the Lord’s Prayer. Coast Guardsmen fired a 21-gun salute, a bugler played taps, and the American flag that draped the mahogany casket was folded and handed to Vice Admiral Clifford I. Pearson, Coast Guard chief of staff, whose father served with Pell on a cutter. Pearson gave the flag to Nuala. The casket was lowered, and Nuala and her family threw spades of earth on it. All was silent for a moment, and then the Pells disappeared inside black funeral-home limousines.

Snow had frosted the cemetery grounds on that cold January day -- but now it was decorated with fallen leaves, a blanket of yellow and gold that extended up the chapel steps. Nuala pointed out her husband’s tombstone, recently erected. It was a simple gray tablet, like the stones marking the graves of Bertie and Julie, who lie next to their father. Inscribed on it were Pell’s name; dates of birth, death and Senate service; and the epitaph he had written. “Statesman, legislator, champion of education and the arts,” it read.Nuala walked through the churchyard, pointing out other graves she knew. There was Ollie O’Donnell, her father, who had found little time for Nuala and her brother after his divorce from their mother. There side-by-side were Claiborne’s mother, Matilda, who died in 1972 at Pelican Ledge, and her husband, the mysterious Commander Koehler, whose death in 1941 had left Matilda in financial difficulty. There in front of the Koehlers was their only child together: Hugo Gladstone Koehler, who died in 1990 at the age of 60. His premature death had moved stepbrother Pell to tears, one of the few times in his life that he cried.On the drive home, Nuala talked of Claiborne’s obsession with death. “He couldn’t accept the fact that there wasn’t anything,” she said. “I told him it was what you believed it to be -- but you had to believe strongly that it would happen. But if you were doubtful, there was nothing.” Claiborne, she said, went to his grave without ever telling her if he had reached any conclusion in his quest. No one would ever know if this man who had worked so long for peace had found it for himself.

One of the last public appearances of Nuala: at the Jan. 28, 2014, announcement that grandson Clay, here with wife Michelle Kwan, is running for governor of Rhode Island.

One of the last public appearances of Nuala: at the Jan. 28, 2014, announcement that grandson Clay, here with wife Michelle Kwan, is running for governor of Rhode Island.

Published on April 15, 2014 04:19

January 19, 2014

Second Amendment gun rights rally: Providence, R.I., 1/19/14

A crowd of hundreds braved a punishing winter wind Sunday to demonstrate on the front steps of the magnificent Rhode Island State House in support of second-amendment rights. The rally, which I covered for The Providence Journal, was one of 50 such planned for every state by Gun Rights Across America.

Scenes from the rally:

Atop the State House dome stands The Independent Man, a monument to Roger Williams, father of Rhode Island, first in America to espouse freedom of speech and religion

Atop the State House dome stands The Independent Man, a monument to Roger Williams, father of Rhode Island, first in America to espouse freedom of speech and religion A broader shot of the rally

A broader shot of the rally Exercising 1st Amendment rights.

Exercising 1st Amendment rights. The view from behind the speakers, Providence Place Mall in background.

The view from behind the speakers, Providence Place Mall in background. Another view.

Another view. The State House steps are popular for wedding photos. This party posed before the gun-rights rally began. What a bitterly cold day to marry!

The State House steps are popular for wedding photos. This party posed before the gun-rights rally began. What a bitterly cold day to marry!

Published on January 19, 2014 12:35

January 8, 2014

Volume 3 of my collected short stories: The Beach That Summer

Thanks once more to my good friends at Crossroad Press, the esteemed David Wilson and David Dodd, the third volume of my collected short stories is now in print. Yay!

Fifteen horror, crime, post-apocalyptic and science-fiction stories -- most never before published, including "The Feeling," my latest, written in 2013. And several personal favorites: the very strange "Every Step of the Way," the religio-dystopian (my specialty) "Christmas in the Year of Our Lord Ten," the seriously demented "The Overseer," and the title story, a twist on Jaws.

Available from Amazon, and in other digital formats and read-online, at Smashwords.

Volumes 1 and 2 (and the rest of my books)? Read more here.

Here is my introduction to the third volume, which tells some of the early story of my other-writer half (yes, the dark side). As always, enjoy -- and heed the last line of the intro, my friends! It all goes so fast, trust me...

Introduction

So here we are. The third volume of my collected short stories. My thanks once more to David and David.

I remember fondly when this long, fulfilling journey of writing horror, mystery and dystopian fiction began. I was in high school – a freshman, I believe – and I had started reading Edgar Allan Poe, who, I assure you, had not been on any reading list at my parochial grammar school, or recommended by my unbending Irish-Catholic mother, whose demons have served me well in my dark fiction in these later years. I loved Poe immediately. He opened a new world to me.

Those early stories, some of which were published in my high school newspaper (easily enough, since I was co-editor!), were not my first tries at fiction. Those came earlier, when I began to scribble vignettes and dribs and drabs of stories. If memory serves me, the very first story I wrote was in fifth grade: a fantasy set on the bottom of the sea, the characters an octopus and a fish.

So writing has been pretty much in my blood forever, for better and for worse (trust me, there is plenty of worse, but we’ll save the psychoanalysis for another time).

After college, I became a journalist, with non-fiction my bread and butter. Reading my first Stephen King Book, ’Salem’s Lot, in 1980, brought me back to horror. I started writing fiction seriously again, on an old electric typewriter. I sold some stories and my first horror novel, Thunder Rise. And while non-fiction remained – and remains – my meal ticket, fiction is my true love.

And so, I am delighted to present The Beach That Summer, fifteen explorations of horror, mystery, madness and more. A couple appeared in magazines a few years back, but the rest are new. Several rank among my personal favorites, if I may be immodest for a moment.

“Christmas in the Year of Our Lord Ten” harkens to that ’60s Catholic upbringing that many of us endured, and it belongs firmly to a treasured sub-genre of my fiction – religious madness, as it may be called – many examples of which you will see in my other collections.

“Every Step of the Way” is a tidy little tale of insanity – or is it?

“First Love” is a most unconventional coming-of-age story, “Labor of Love” a twist on Rosemary’s Baby. The aging mother in “Momma” seems to suffer from Alzheimer’s… seems to. In “Something for Heidi,” a creepy misogynist gets what he deserves. “The Overseer” demonstrates that while you may be able to run, you can never, ever hide. “The Place He Was In” was inspired by “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” the best Twilight Zoneepisode ever, in my view.

Title story “The Beach That Summer” is near the top of my personal favorites – a noir tale of a serial killer loose in an idyllic setting. In that one, I took the basic premise of the great summer movie Jaws and turned it human. Or, more accurately, inhuman.

And I offer several more dark stories in this volume, including one I completed just a few weeks ago: “The Feeling,” about a young man with a haunting connection to his dead father.

As always, enjoy. Be well.

And give someone you love a hug. That’s the best kind of feeling.

January 5, 2014Providence, Rhode Island

January 5, 2014Providence, Rhode Island

Published on January 08, 2014 11:58

January 1, 2014

Stephen King interview, summer, 1986

In the summer of 1986, I interviewed Stephen King in a New York City hotel room. Here's The Providence Journal Story that resulted...

KING OF HORROR His career's in 'Overdrive' as he directs his first filmG. WAYNE MILLERPublication Date: August 3, 1986 Page: I-01 Section: ARTS Edition: ALL

STEPHEN KING, the most popular horror writer of all time, is eating pizza - thick, oily, mega-calorie pizza with all the fixings. He's eating it the way a big hungry kid would - ferociously and noisily. Stephen King loves pizza, just as he loves scaring the pants off people.

King, who has made enough money from what he calls his "marketable obsession" to buy Brooks Brothers' entire inventory, is dressed in jeans, work shirt, running shoes. Comfort is the thing for King, who sets many of his stories in rural Maine, the place he's lived most of his 38 years.

Would his visitor like a slice of that greasy monster masquerading as a pizza, he asks politely? No? Then have a seat. Feel at home.

He sits - flops is probably a better word - onto an oversized chair in his hotel suite. King is well over six feet tall, and his long legs seem to stretch halfway across this elegantly furnished sitting room. He brushes his black hair off his face, grins mischievously, and peers from behind thick glasses, his "Coke bottles," as he's referred to them.

"Whatever you want to talk about," he says in a voice that is a curious mix of Downeast twang and Ted Kennedy drone. "The film is what I'm supposed to talk about, so why don't we start with the film?"

Maximum Overdrive, King's first shot at directing, opened last weekend. It's about a group of people trapped by driverless vehicles in an isolated truck stop the week all the machines in the world go murderously berserk. Machines gone mad. It's a favorite King theme, and if one were to psychoanalyze it, the connection to modern man's uneasy coexistence with his nuclear genie would be hard to miss.

The obvious first question, of course, is why a one-time teacher who has parlayed a lifelong fascination with the macabre into a fairy-tale existence as best-selling author (70 million books in print) would want to trade his golden pen for a camera.

Certainly, King is no stranger to movies. He admits to being a horror-movie junkie growing up in the '50s and '60s; as an adult, he has written the screenplays for five films, including Overdrive. Eight of his full-length novels have been made into films of varying quality, and another four (including Pet Sematary, his most recent) are in various stages of production. On top of all that, several King short stories have been adapted for TV, and an unpublished novel has been sold for a mini-series.

From StephenKing.comSo why direct?

From StephenKing.comSo why direct?"Curiosity," he says, continuing to gorge himself on pizza.

Actually, it wasn't simply curiosity that prompted King to accept movie mogul Dino De Laurentis's offer to direct.

Although King is pleased with some film adaptations of his works - he thinks Cujo and The Dead Zone are great - he has been disappointed with others. In particular, Firestarter, Children of the Corn, and The Shining, directed by Stanley Kubrick, still make King cringe. (He once described Firestarter as "flavorless," like "cafeteria mashed potatoes.")

The disappointing films, King explains between bites, failed to capture the spirit of his written works - either they didn't frighten, or took implausible twists, or were blandly acted, or sloppily directed, whatever. With Overdrive, King finally wanted to see if he could capture that spirit on film. If he couldn't, well, at least he'd have no one but himself to blame.

"My son's got this wonderful imitation of Leonard Malton on Entertainment Tonight," King says, becoming suddenly animated.

"He'll start off the way he always starts off when he's going to give a really bad review. He'll say, 'This is Leonard Malton, Entertainment Tonight. Stephen King says that he wanted to direct a picture to see if whatever makes his books so successful could be translated to film if he did it himself.

" 'The answer is no' "

King grins. "Actually," he continues, "the answer is yes. I think. I think it has a lot of appeal of the books."

Not that he's exactly rehearsing his Academy Award acceptance speech, as he notes wryly. Although the film does not look amateurish - for a rookie, King's grasp of cinematic technique is quite impressive - its human characters are undeveloped. And despite King's hopes, Overdrive only hints at his books' rich textures. It's hard to escape the conclusion that what King does so well in print probably can't be translated onto the silver screen.

"I think by and large this movie will get kind of a sour critical reception," he predicts. "It's a 'moron movie,' for one thing. It's crash and bash. It's a head-banger movie - really, really loud."

Promotional tour

Critics notwithstanding, King believes audiences will like Overdrive as much as he does. He hopes so, anyway. The only reason he agreed to do a nationwide promotional tour is to hype the film. Too many earlier King films, he laments, have lasted in theaters all of two weeks.

"Graham Greene said . . . writers write books they can't find on library shelves. To some extent, I think directors must direct movies that they can't go and watch in movie theaters.

"Overdrive is fun. I like movies where you can just, like, check your brains at the box office and pick 'em up two hours later. Sit and kind of let it flow over you and, you know, dig on it. This movie is just sort of gaudy blaaaaah. It's not a heavy social statement," he asserts.

Suddenly, without warning, the lines on King's face deepen, his eyes become cat slits and he's baring his teeth - he's got one hell of a set of incisors, one discovers. Normally a rational and intelligent human being, he's transformed himself into a raving lunatic.

He jumps up and screams: "One of the things I wanted was to never let up. My idea is that what you do is build up, like reaching out and grabbing somebody by the ----] Right out of the page if possible or right out of the screen] Tell you what, ------------, you're mine]]]]]]"

He sits down again, laughing like - like a kid.

Four new novels

To say that Stephen King is big is a little like saying Carrie, telekinetic murderess of his first novel, is odd.

Some noteworthy footnotes to the King saga:

* The initial hardcover printing of last year's Skeleton Crew, his second anthology, was one million copies, one of the largest first hardcover printings in publishing history.

* King books are hot collectors’ items. In May, for example, an uncorrected proof of his Night Shift collection brought $2,500 at a San Francisco auction. A small-press magazine in which one of his stories appeared years ago brought a cool $150.

* For a decade, King's books have consistently topped the best-seller lists. According to Publishers Weekly, his scorecard for 1985 included the fifth and 11th best-selling fiction hardcover books; the second, fourth and eight best-selling mass paperbacks; and the second and third best-selling trade paperbacks. Total sales of those seven books alone: 11.49 million.

* King has his own monthly newspaper, Castle Rock, published and edited by his secretary, Stephanie Leonard.

* Against the advice of his publisher, who's worried that the market will be saturated (King disagrees), King will release four new novels in the next year, including the 1,000-page-plus IT later this summer.

* A musical version of Carrie takes to Broadway this fall.

Not to mention all those movies.

This being America, money has come hand-in-hand with his fame. King is so rich that when someone threatened to buy his favorite radio station in Bangor, Maine, and replace its rock format with EZ Listening, he rushed out and bought it himself. Rumor has it he paid cash.

The unknowns remain

Naturally, there are secrets to King's success.

One - hardly the best-kept - is that people, millions of them, anyway, like to be scared. Late at night, with the wind moaning, the leaves on the trees rustling, the kids sleeping (are they still breathing?) and something downstairs making a strange noise (is it only the cat?), they love to curl up with a good scary book and let the chills crawl down their spines.

King has lectured and written extensively about fear. He understands that no matter how technologically advanced we become, no matter how much the scientists figure out about ourselves and our world, the great unknowns remain: darkness, death, whatever is beyond the grave.

Still, there are plenty of horror writers slogging away out there, including several who have won critical acclaim - such as Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho, and Peter Straub, author of the million-seller Ghost Story, and J.N. Williamson and Richard Matheson, two of the more prolific writers of the genre. Some are literary, closer to Poe than King; others are more gruesome, more skilled with plot. In terms of popularity, King has eclipsed them all.

The real secret is where King has taken horror - out of the Egyptian mummy's tomb and straight into the living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens of contemporary middle- and lower-class America. King's landscape is the America of kids and pets and Coke and malls and cheeseburgers and troubles with the mortgage payment and that old clunker, the family car - much the same vision of America that Steven Speilberg has brought to Hollywood.

Not that everything is ordinary in King's works. Whether haunted car or haunted child, King's villains and monsters and spirits are deeply troubling, frequently uncontrollable, and usually deadly. There's a lot of darkness in King's work, and plenty of ghosts. Death is never very far away.

It is precisely this juxtaposition - ordinary people victimized by extraordinary forces - that is the key to all good horror, not just King's.

Hitting the nerves

Still . . . 70 million books, 16 movies, a Broadway play, and no end in sight?

"Some of it," King explains as he polishes off lunch, "has got to be that I'm talking about things that, like you say, hit nerves. Or maybe they don't hit nerves - maybe they just resonate.

"You know, people say, 'I know about that, because that happened to me.' I don't mean an ability to light fires or anything like that (the heroine of Firestarter is a young girl with pyrotechnic powers), but something about family life, or something your kid said, something like that."

Not that King's intent is anthropological exposition; he is not a scholar, nor does he pretend to be. He bases his fiction on situations he understands because they've been his life, too - family, marriage, the battle (at least in the early days) for a buck. King and his wife, Tabitha, also an author, have three children. The eldest is 16.

"I don't write with an audience in mind. I mean, the audience is me. My popularity says something about my own mind. It's a little bit distressing when you think about it. It says, 'Well, here's a person who's so perfectly in tune with middle-cultural drone that there must be this incredible bowling alley echo inside his head.' "

Even King's detractors - there's no shortage of critics who dismiss his work as insignificant - concede that he has a true talent for depicting children. Maybe that's because King himself could well be the biggest kid in America. Even when they are blessed/cursed with supernatural powers, King's fictional children are flesh and blood - so seemingly real that you wonder if they don't actually exist somewhere, and King is only documenting their lives.

In fact, King's own children have had enormous impact, and if you doubt that, you only need look at his dedications.

"I grew up with them," he says. "Bringing up baby or child or children or whatever has been one of the experiences of my life, and so it's one of the things I write about. But also it's a way of trying to make sense of how the child you were yourself became the man that you are and that whole crazy business."

Woes with women

As good as King has been creating children, he has had his woes with women, as countless critics have been quick to point out.

"I've had such problems with women characters," he agrees, the smile leaving his face. "God knows I have tried. I tried with Donna Trenton in Cujo - tried to make a real woman. (I thought) she worked pretty well, except I got hit pretty hard by a lot of critics. An awful lot of critics said the dog is punishment for adultery.

"The death of her child . . . consciously, on top of my mind, I was simply trying to create a convincing chain of events that would put the boy and her in that position where they could spend a period of time. But when you think about it. . . .

"Yes, I've had trouble with women. It's funny because that's why I started to write Carrie. This friend of mine said to me, 'The trouble with you is you don't understand women.' I said, 'What do you mean?' It's like he'd accused me of being a virgin or something like that, which I just barely wasn't at that time.

"He says, 'Ah, all these stories with these hairy-chested horror things, these guys fighting monsters and stuff like that.' I was trying to tell him, 'You don't understand. That's what they buy, these men's magazines.' He said, 'You couldn't create a woman character if you tried. You know, a good one.' I said I bet I could. Carrie - that's a book about women, almost completely about women. There are almost no male characters in it."

Father ran off

By now, the story of King's climb to the top is legendary.

It begins with a kid growing up in Maine and (for four years) in Connecticut - a kid whose father ran off never to be heard from again, a kid whose mother raised him and his elder brother on a shoestring. On the outside, King was a polite child who liked cars, played some sports - but inside, he would later recall, he often felt unhappy, "different," even violent.

He remembers writing his first horror story at the age of seven; it was about dinosaurs on a rampage. Through his teens, he read voraciously, spent hours in movie theaters, kept on writing and writing and writing. It was while attending the University of Maine, Orono, that he began to sell short stories to magazines. But his novels, and there were several of them by this point, were going nowhere.

After college, he and his wife worked a succession of jobs to keep their family afloat: Tabitha as a waitress, he as a worker in a coin laundry and as an English teacher at a private school. The short stories kept selling - they were helping to pay the rent on the tiny trailer where they lived - but the novels were still moribund.

King wrote Carrie working late into the night in the furnace room of their trailer - the only available space in already cramped quarters. Somewhere, King says, they still have the Olivetti portable typewriter on which he banged out several early novels and stories.

The old portable

"There were no word processors then," King remembers. "I used my wife's portable. She stills says sometimes - in jest, I think - 'My husband married me for my portable typewriter.' It's got my fingerprints carved into the keys. I mean, I beat that thing to death just about.

"I used to have to bring Joe in in his crib to where I worked, which was the furnace room. You'd get hot and you'd be going along good and he'd wake up and you'd have to give him a bottle because he'd cried. It was just, you know, you get it done the best you can.

"You don't raise your head and look around, because if you do you just get depressed. And I was depressed then. Because I was selling some short stories, but I had had like three, four novels bounced back at me at that time and also a number of other short stories."

Even after finally selling Carrie to Doubleday, the struggle continued.

"My wife used to work at 'Drunken' Donuts,' which is what they called it on the night shift. I used to take care of the kids while I did the rewrite. This was after the contract and everything, but before we had any money. I mean, the contract was only for $2,500. It wasn't exactly a king's ransom," he says, seemingly unaware of the pun.

The big break came with the paperback contract for Carrie, which had done reasonably well in hardcover. King had expected to earn $5,000 to $12,000 on the paperback rights. When his editor called to tell him that the sale had been for $400,000, virtually unprecedented at the time for a newcomer, he was flabbergasted.

He celebrated by buying the thing he thought his wife would like the most - a $29 hair dryer.

'Normal' life in Maine

It seems a lifetime ago, those early days.

Today, King and his family live in a large Victorian house in Bangor. He has a summer home on a Maine lake, drives a Mercedes, is a Red Sox fan, loves beer as much as pizza, enjoys tennis and softball, usually wears a beard in winter. Except when he's on tour, he writes every day of the year, except Christmas, the Fourth of July and his birthday. He does the family shopping. His children attend public schools.

"They don't have any sense that there's anything really odd about what I do because I've never made out like I'm a big shot because I don't feel that I am. Also, we don't live in New York or California, where they might live in an atmosphere that's a little stranger. They seem pretty normal."

Although he is Bangor's most famous citizen - arguably Maine's, as well - the natives, he says, "mostly leave me alone. I have the town broken in. I guess familiarity breeds contempt."

Not that he hasn't become something of a celebrity for the tourists - a class of citizen he has often lampooned in his written works.

"Oh, sure," he says. "They have Canadian tour buses that come down to go to the mall - the Bangor Mall, which is the closest real big super mall to Nova Scotia. One of the things they throw in with this is you get to go by the 'Stephen King House,' like you're stuffed and embalmed. You're in there and one day you look out and you see this huge bus with 150 Canadians lined up along the fence snapping pictures. It's very odd."

Next interview

A TV crew has arrived early to set up for King's next interview. "Let's go into the bedroom," he suggests. "It's quieter." He gets up, crosses the room and closes the door behind him. Stretching full-length on his unmade bed, he props himself up on his elbows and resumes talking about his film.

Overdrive is based on "Trucks," one of several brilliant short stories in his first anthology, Night Shift.

"It's always been my favorite from that collection," he says. "Trucks I liked just for the feel of it. It had a desperate film noir quality as a story."

Machines gone mad. In Overdrive, which will be remembered more for its special effects and pyrotechnics than its acting or social significance, they go one step further: They try to take over the world. Knives, soda machines, video games, lawnmowers, a drawbridge, cars, 18-wheelers - all become killers.

"I'm fascinated by (machines)," King says enthusiastically. "They scare me. There's so much potential for destruction. In the film there's a track shot that starts on this hammock that's empty and swinging. In the background you see a guy who's obviously had his head cut off by his own chainsaw. The chainsaw is buried somewhere in his neck.

"There's a little Watchman with a little teeny screen giving this information about machines having gone berserk. The camera pans down and tracks and you see an overturned Styrofoam cooler and then you see empty beer bottles and then you see the Watchman. It doesn't have a picture on it but it's splattered with blood.

"Then you see the guy and you track up his body and he's all been shredded because he's been, you know, 'lawn-mowered' to death. You come to the lawnmower itself and it's all covered with blood and everything. When it finally runs, it chases this kid. It's quite funny."

He chuckles, then pauses. "Well to me, it's funny," he explains. "A lot of people are going to say it's gross and gratuitous. That's OK."

Machines and actors

King chose Overdrive for his directorial debut because he thought it would be easier to work with special effects and machines rather than with real-life actors.

It turned out to be the other way around.

"I thought to myself: 'My electric knife is never going to say, 'I can't cut the actress's arm today because my hairdresser didn't come in from New York.' My truck is never going to say, 'I can't run by myself today because I'm having my period.' You know what I mean?

"I went into the thing with a lot of the stereotyped ideas that people get about actors. You know, 'They're a bunch of conceited snobs. They're all babyish, you have to baby them along, you have to always be feeding them constant praise, they're always difficult to work with,' all this stuff.

"It turned out all to be b-------. They all worked really hard. They gave me more than 150 percent. They were almost always at their best.

"The actors were great, but all the machines . . . they wouldn't run. The trucks wouldn't start. We crashed four vehicles that were supposed to roll over before one finally did, and that was only on the third take. We had problems with the power mower. It was radio-controlled. Back at the studio, it went like a bat out of hell. Get it on location, it would just sit there.

"The electric knife that goes beserk . . . skittering along the floor like a big bug. The special-effects guys built three knives using dildo motors - basically vibrator motors to make them work. Two of them got wrecked on bad takes and we only had one left and we had to get it right. Luckily we did."

What scares him

The TV people are ready and time is almost up.

A few questions remain.

What scares you?

"Just about everything, in one way or another," he says. "But I think the thing that scares me most would be to check on one of my kids one night and find him dead in bed."

Did you ever expect to sell 70 million books?

"I don't even know what that figure means," he says, as if still finding it impossible to believe. "Do you realize if I live along enough there could be as many copies of my stuff actually sold as there are people in the country?"

No, King never expected all this - not even in his wildest dreams.

Are you afraid that someday it'll all be gone?

"Yeah," he laughs, starting to act out a scene from a movie where an enormously fat man explodes after a gargantuan meal. "Someday I'll just burst like that guy in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life. Did you see that? 'Just one more mint.' 'Nah, I'll burst'. . . and he did."

Published on January 01, 2014 07:34

December 11, 2013

Remembering Dad

I wrote this a year ago, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of my father's death. Like his memory, it has withstood the test of time.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died ten years ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 10th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy,which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last decade. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three children are making their way in the world, and that he now has two great-granddaughters, wonderful little girls both. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sisters and my children remember and miss him. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.My Dad and Airplanesby G. Wayne Miller I live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died ten years ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 10th anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy,which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last decade. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three children are making their way in the world, and that he now has two great-granddaughters, wonderful little girls both. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I, my sisters and my children remember and miss him. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, for whom I am named, built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

Published on December 11, 2013 03:16

December 2, 2013

Your brain isn't lefty or righty, but probably top or bottom

Published on December 02, 2013 09:07

November 14, 2013

ReadWave -- a Must-Read!

There may not be exactly a million writers' sites out there, but there sure are a lot of them. Cutting through the din is difficult, particularly for young writers seeking an audience for their work -- a tough row to hoe, as I know first-hand from my early days toiling in this crazy vineyard.

So when a truly distinctive opportunity opens, I pay attention. Which is why I responded to a recent email from a gent named Robert Tucker, co-founder and editor of ReadWave, whose physical home is in London. Rob had happened on my work, and contacted me to see if I would like to contribute a story to his site, a place "for sharing 3 minute stories and articles... a place where you can write about anything -- an idea, a life experience, a travel adventure or a moment of inspiration -- as long as it's under 800 words."

I went to ReadWave and really liked what I saw -- a fresh mix of creatively and culturally diverse voices participating in what I would describe as a very public storytelling square (as co-founder and co-director of just such an enterprise, the Story in the Public Square program at Salve Regina University's Pell Center in Newport, R.I., USA, I really dug that!)

So I accepted Rob's invitation, and wrote a 3- (possibly 4!) minute essay about collaborative writing, something I have rarely done in my long career.

Long story short: This is a great place for writers and readers (and that pretty much covers everyone). Make ReadWave part of your daily routine. Pass the word by mouth, Tweet, Facebook, whatever. And wish Rob and his crew the best of luck as they grow their storytelling square.

Robert Tucker

Robert Tucker

So when a truly distinctive opportunity opens, I pay attention. Which is why I responded to a recent email from a gent named Robert Tucker, co-founder and editor of ReadWave, whose physical home is in London. Rob had happened on my work, and contacted me to see if I would like to contribute a story to his site, a place "for sharing 3 minute stories and articles... a place where you can write about anything -- an idea, a life experience, a travel adventure or a moment of inspiration -- as long as it's under 800 words."

I went to ReadWave and really liked what I saw -- a fresh mix of creatively and culturally diverse voices participating in what I would describe as a very public storytelling square (as co-founder and co-director of just such an enterprise, the Story in the Public Square program at Salve Regina University's Pell Center in Newport, R.I., USA, I really dug that!)

So I accepted Rob's invitation, and wrote a 3- (possibly 4!) minute essay about collaborative writing, something I have rarely done in my long career.

Long story short: This is a great place for writers and readers (and that pretty much covers everyone). Make ReadWave part of your daily routine. Pass the word by mouth, Tweet, Facebook, whatever. And wish Rob and his crew the best of luck as they grow their storytelling square.

Robert Tucker

Robert Tucker

Published on November 14, 2013 11:08

October 16, 2013

Baltimore Catechism v. NSA: Lessons 15 and 17

15. What do we mean when we say that God is all-knowing?

When we say that God is all-knowing we mean that He knows

all things, past, present, and future, even our most secret thoughts, words,

and actions.

15. What do we mean when we say that NSA is all-knowing?

When we say that NSA is all-knowing we mean that It knows

all things, past, present, and future, even our most secret thoughts, words,

and actions.

*****

17. If God is everywhere, why do we not see Him?

Although God is everywhere, we do not see Him because He is

a spirit and cannot be seen with our eyes.

17. If NSA is everywhere, why do we not see It?

Although NSA is everywhere, we do not see It because It is a

spy agency and cannot be seen with our eyes through Its windowless concrete building in Utah.

Published on October 16, 2013 03:17

September 11, 2013

Sneak Preview: Test the Brain Test

With the impending publication of TOP BRAIN, BOTTOM BRAIN: Surprising Insights Into How You Think (Simon & Schuster, Nov. 5), we are soon to launch an online and mobile app that assesses (in 20 easy questions) your dominant thinking mode. Are you a Mover? A Perceiver? A Stimulator or Adaptor? The app version of the test automatically makes the determination (in the hard copy of the book, you need pencil and paper).

Before we publicize the test, I'd like some reader input. And so, I invite you to take the test, and send your comments to us at TopBrainBottomBrain@gmail.com

The test is here. Thanks!

Published on September 11, 2013 06:23

September 9, 2013

Camelot, then and now

The Providence Sunday Journal yesterday published "Sunset Days in Camelot: JFK's last September in Newport," my look back at the president's final two weekends with Jackie, Caroline and John Jr. at Hammersmith Farm and the City by the Sea. Oswald's bullet, of course, closed the story.

The story is accompanied by a great slideshow of JFK, Jackie and family, and friends including Nuala and Claiborne Pell. Highly recommended!

In writing the story, I visited Jackie's stepbrother, Yusha Auchincloss, who still lives on the grounds of Hammersmith Farm. A gentleman always, Yusha shared stories, showed photos, and walked the seaside lawn of the big house, where the president's helicopter touched down a half century ago. Yusha's son, Cecil, joined us. Here are few photos that did not make the paper.

Yusha walks the Hammersmith Lawn, big house beyond.

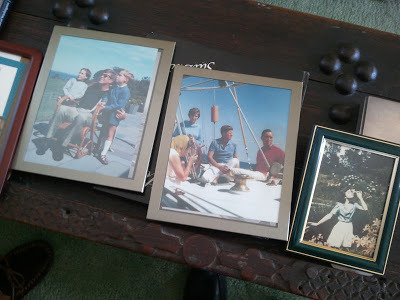

JFK with Yusha's children, Maya and Cecil; the president with Yusha on yacht Honey Fitz; Jackie before she married. Photos in Yusha's house

Cecil and Yusha pose for Journal staff Photographer Freida Squires.

Yusha in his sitting room today.

Close on the young Jackie.

Published on September 09, 2013 03:39