Leslie Glass's Blog, page 381

April 4, 2018

Setting Boundaries For A Boundary Buster

Boundaries keep us safe from all types of harm. Some boundaries, like my 6-foot tall wooden fence are visible. Others are not. No matter which type of boundary you set, someone somewhere will find a way to test your boundary. Last night, my boundary buster was a tortoise. He showed me breaches in my boundaries, and I found 10 ways to reinforce them.

I was doing some stretches in my backyard, when I heard a strange rustling in the leaves. My dog heard it too, and we quickly found an uninvited guest – a big turtle. He was probably 20 inches long. My new guest exposed four of my biggest boundary problems.

1. My Boundary Has A Weakness

This was no small turtle. He was certainly bigger than any natural gaps in the fence. Since he lacks opposable thumbs and a ladder, I’m not sure how he got in. Worse than that, we live in Florida. If he got in, what else will wander into my yard? Skunks? Bobcats? Alligators? Thieves?

2. Denial Is Stronger Than My Boundary

I pondered the potential alligator dilemma for a minute then quickly dismissed it. “There’s no way an alligator could fit through my fence.” I reasoned.

“Yet this awkward, slow moving turtle found a way in,” the voice of truth answered. Years of destructive conditioning prepared me to ignore the truth at all costs, but the possibility of an alligator in my pool keeps creeping back to the forefront of my mind.

Denial answers, “Silly girl, an alligator would be put off by the chemicals in your pool. You’ve got nothing to worry about.”

One small-ish turtle is OK for a yard my size. No alligators of any size will work for me, but I am surprised at how strong my denial is.

3. Boundaries Will Be Tested Repeatedly

The turtle isn’t my only boundary buster. My son, being a typically boy, wanted to keep the turtle. Being co-dependent, I wanted to keep it too, but I’m recovered enough to know my backyard is not a turtle hotel. My yard does not have enough food or water to keep the turtle alive.

Drs. Henry Cloud and John Townsend explain the pain I felt in setting my boundary, “The most responsible behavior possible is usually the most difficult.”

4. Boundaries Must Be Reinforced

I have the same amount of control over a wild turtle as I do any other human – NONE. I can only change myself. When I am frustrated, edgy, and angry, I have most likely been giving in to a boundary buster, who is often my teenager.

In her book, Codependent No More, Melody Beattie gives codependents some sample boundaries. If your boundary buster isn’t a person struggling with addiction, just fill in the blank with your boundary buster du jour i.e., turtle, teenager, or gaslighting mother-in-law. I will not:

Allow anyone to physically or verbally abuse me.

Knowingly believe or support lies.

Allow _________________ (chemical abuse, wild turtles, or hateful teenagers) in my home.

Allow criminal behavior in my home.

Rescue ___________________ (people, turtles, or teenagers) from the consequences of _________________ (lying, chemical abuse, or trespassing).

Finance a person’s addiction to ________________ (alcohol, substances, wild turtles, or other irresponsible behaviors).

Lie to protect you or me from _________________ (alcoholism, abuse, or harboring a wild turtle).

Use my home as a detoxification center for recovering alcoholics or a rehabilitation center for wayward turtles.

Her last two suggested boundaries are crucial:

“If you want to act crazy, that’s your business, but you can’t do it in front of me. Either you leave, or I will walk away.”

“You can spoil your day, your fun, your life – that’s your business, but I won’t let you spoil my fun, my day or my life.”

Sometimes we need professional help to set boundaries. Visit Recovery Guidance to find therapists, counselors, and other treatment options near you.

The post Setting Boundaries For A Boundary Buster appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

Eat Pasta For Weight Loss

It all comes down to pasta’s low glycemic index (GI), according to researchers at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Canada. GI is a system used to rate how quickly a food affects blood sugar levels. The sugar in high GI foods such as white rice, white bread and potatoes are digested and absorbed quickly by the body, while low GI foods such as green vegetables and lentils are burned slowly.

Researchers investigated the supposed link between pasta and weight gain by assessing 30 randomized control trials with almost 2,500 participants who followed what was regarded as a healthy low GI diet, and ate pasta instead of other forms of carbohydrate. Study participants ate 3.3 servings of around a half cup of pasta on average each week. Pasta has been unfairly maligned, the study suggests.JASON LEUNG/UNSPLASH

Pasta has been unfairly maligned, the study suggests.JASON LEUNG/UNSPLASH

By analyzing participants’ body weight, BMI, body fat, and waist measurements, the researchers behind the study published in the BMJ Open journal found that pasta did not contribute to weight gain or increased fat levels. Over 12 weeks, they lost half a kilo on average. The results could be explained by the fact that lower GI foods satiate hunger better, and therefore prevented people from consuming more food, according to the authors.

The researchers noted that while there are many types of pasta, they all generally have a lower GI status than other starchy foods such as white bread. The study emphasized that the inclusion of whole grains does not significantly affect pasta’s GI status. And while it is relatively low in fiber, pasta has a similar GI rating to fiber-rich foods such as barley, legumes and steel cut oats, and a lower rating than wholewheat bread, breakfast cereals like bran flakes and potatoes with skin. On average, white pasta also has a higher micronutrient content than other white wheat products.

“These results are important given the negative messages with which the public has been inundated regarding carbohydrates, messages which appear to be influencing their food choices, as evidenced by recent reductions in carbohydrate intake, especially in pasta intake,” the authors wrote.

“So contrary to concerns, perhaps pasta can be part of a healthy diet such as a low GI diet,” lead author Dr John Sievenpiper, a clinician scientist with the hospital’s Clinical Nutrition and Risk Modification Centre, said in a statement.

“In weighing the evidence, we can now say with some confidence that pasta does not have an adverse effect on body weight outcomes when it is consumed as part of a healthy dietary pattern.”

The authors said that the overall weight loss was likely down to eating pasta alongside other low GI foods. Further research is now needed to assess whether the same effects of eating pasta would occur in other healthy eating patterns, such as Mediterranean and vegetarian patterns, which may not be primarily focused on low GI.

Nichola Ludlam-Raine, a qualified dietitian and spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association told Newsweek that gram for gram, carbohydrates are not fattening.

“Carbohydrates actually provide only four calories per gram, which is the same as protein and is under half of what fat provides (nine calories per gram).

“The reason why carbohydrates have a bad rep is that we tend to eat too much of them and then smother them in fat and sugar, i.e. extra calories. For example big bowls of cheesy pasta and sugary cereal. So it isn’t carbohydrates per se that cause weight gain, it’s the portion size in which we eat them and what we add to them that counts.”

She added: “I personally advise people aim for a clenched fist size of cooked pasta (preferably wholemeal) at a meal, remembering that pasta swells during cooking.

“It’s not the amount of fats or carbs in your diet that matters, it’s down to the overall quality and taking both into account matters.”

The post Eat Pasta For Weight Loss appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

April 3, 2018

FDA Orders Recall of Kratom

The Food and Drug Administration said Tuesday it took the rare step of ordering the recall because Triangle Pharmanaturals refused to cooperate with regulators. Companies typically issue their own recalls of tainted products.

Various brands of kratom supplements have been linked to nearly 90 cases of salmonella across 35 states, according to federal figures.

Sold in various capsules and powders, kratom has gained popularity in the U.S. as an alternative treatment for pain, anxiety and drug dependence.

The FDA says the ingredient is dangerous and has no approved medical use.

The post FDA Orders Recall of Kratom appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

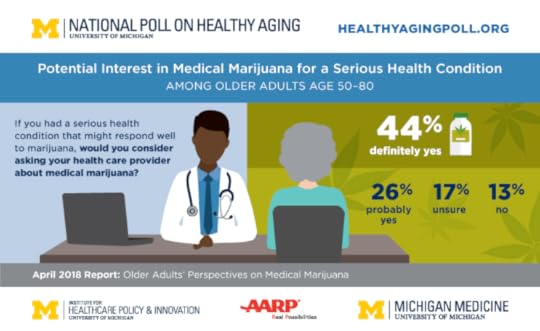

Seniors Want More Research On Med Pot

ANN ARBOR, MI – Few older adults use medical marijuana, a new national poll finds, but the majority support its use if a doctor recommends it, and might talk to their own doctor about it if they developed a serious health condition.

Four out five of poll respondents between the ages of 50 and 80 said they support allowing medical marijuana if it’s recommended by a physician. Forty percent support allowing marijuana use for any reason.

And two-thirds say the government should do more to study the drug’s health effects, according to the new findings from the National Poll on Healthy Aging.

While more than two-thirds of those polled said they thought that marijuana can ease pain, about half said they believed prescription pain medications were more effective than marijuana.

The poll was conducted in a nationally representative sample of 2,007 Americans between the ages of 50 and 80 by the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation. It was sponsored by AARP and Michigan Medicine, U-M’s academic medical center.

“While just six percent of our poll respondents said they’d used marijuana for medical purposes themselves, 18 percent said they know someone who has,” says U-M’s Preeti Malani, M.D., director of the poll and a specialist in treatment of older patients. “With medical marijuana already legal in 29 states and the District of Columbia, and other states considering legalizing this use or all use, this is an issue of interest to patients, providers and policymakers alike.”

She notes that the poll results indicate older Americans have a sense of wariness, rather than wholehearted acceptance, around medical use of marijuana. This may be surprising to those who think of the Baby Boom generation – who are now in their mid-50s to early 70s — as embracing marijuana use in their youth in the 1960s and 1970s.

Marijuana and pain

The poll sheds new light on older Americans’ attitudes toward the use of marijuana to control pain – one of the most common conditions cited in state medical marijuana statutes.

Just under one-third of respondents said they feel that marijuana definitely provides pain relief, and another 38 percent said it probably does. But only 14 percent thought marijuana was more effective than prescription pain medication, while 48 percent believed the opposite and 38 percent believed the two were equally effective. When it came to controlling dosages for pain relief, though, prescription pain medicine won out: 41 percent thought it would be easier to control dosage with medication.

The poll also asked respondents about negative effects of both substances. In all, 48 percent thought prescription pain medicines are more addictive than marijuana, and 57 said that such medicines have more side effects than marijuana.

“These perceptions of relative safety and efficacy are important for physicians, other providers and public health regulators to understand,” says Malani. Marijuana use, particularly long-term use, has been associated with impaired memory, decision making and ability to perform complex tasks.

The widespread support by older Americans for more research on the effects of marijuana is especially significant, she says, given the growing legalization trend in states and the continued federal policy that marijuana use is illegal.

“Although older adults may be a bit wary about marijuana, the majority support more research on it,” says Alison Bryant, Ph.D., senior vice president of research for AARP. “This openness to more research likely speaks to a desire to find safe, alternative treatments to control pain.”

Research on marijuana’s effects and related issues can be done under carefully controlled circumstances, but few studies have included older adults. The new poll results indicate an appetite for further government-sponsored research, including government-standardized dosing.

Malani, a professor of internal medicine at the U-M Medical School who specializes in infectious diseases and geriatrics, notes that providers should be routinely asking older patients about marijuana use.

Only one in five poll respondents said their primary health care provider had asked whether they use marijuana. A slightly lower percentage said they thought their provider was knowledgeable about medical marijuana – but three-quarters said they simply didn’t know how much their provider knows about the topic.

Still, 70 percent of those who answered the poll said they would definitely or probably ask their provider about marijuana if they had a serious medical condition that might respond to it. That means providers need to be ready to answer questions and provide counseling to patients, especially in states where medical marijuana is legal.

The poll results are based on answers from a nationally representative sample of 2,007 people ages 50 to 80. The poll respondents answered a wide range of questions online. Questions were written, and data interpreted and compiled, by the IHPI team. Laptops and Internet access were provided to poll respondents who did not already have it.

A full report of the findings and methodology is available at www.healthyagingpoll.org , along with past reports on National Poll on Healthy Aging findings.

The post Seniors Want More Research On Med Pot appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

How To Regulate In Recovery

What Does Regulate For Recovery Mean

When I am well exercised, rested, nourished and cared for, I don’t feel restless, irritable, and discontented. No, this didn’t come easy. Yes, it took years of practice, but I’m pretty disciplined now. I don’t want to feel crummy because I’m eating poorly and feel bloated. I hate feeling anxious because I’ve had nothing to eat but coffee all day, and I do my very best to stay away from feelings of anger, or resentment, whenever possible. So, great, Yay for me. It’s nice that I have some tools and knowledge about how to care for myself today, but there’s more to it.

Reality Challenges Discipline and Tools

Reality is always going to enter the picture. No matter how careful I am, bad things are going to happen, and good things are going to happen. Professional successes come up and steal the spotlight creating heightened emotions. Professional mistakes or failures occur that get me all shook up. Romance happens, heartbreak happens. For me, sometimes quarterly! I seem always to have lots of change in my life, so if I’m not vigilant about regulation, I’m screwed.

Wishful Thinking Challenges Discipline And Tools

Here’s another challenge: my thinking. I regularly get caught up in thinking someone, or something is going to complete my life. I have to regulate my thinking as well as my physical habits. It’s easy to remember to eat when you realize you’re hungry, or to take a nap when you realize you need one. It’s much harder to know what to do when you feel lonely, or angry.

How To Know What You’re Thinking

Personally, I’ve spent some time figuring out how to understand what I’m feeling. This required the help of people who people who know like therapists and other experts, even being in groups. But internalizing what I heard was only part of it. Reading up on recovery and behaviors and writing about the past and my emotions keeps me centered. Writing is part of recovery for many people. Writing (or journaling) helps clarify what’s going on for me. Once I’m clear, I usually have a better answer of what to do next. A dear friend once told me, when you don’t know what to do, don’t do anything. The answer will eventually come clear. With a little practice, I now know when to do what. For example, don’t do nothing when someone is expecting an answer.

I challenge you to think about how you regulate yourself. What do you do when you feel dreaded feelings? What’s your care-level these days? Sometimes, we get too busy doing life we forget how to take a moment and make sure we’re covered.

The post How To Regulate In Recovery appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

April 2, 2018

Maintaining Individuality While Loving Another

Maintaining individuality in a loving relationship requires a quite a bit of self awareness and sensitivity all around. If you’re codependent or happen to be an adult child of an alcoholic (ACOA), you’re likely to be subsumed by the needs of your loved one, never thinking of your own likes and dislikes. And often boundaries go out the window altogether. The other person wins. And you, secretly might be full of resentments.

Maintaining Individuality Is A Balancing Act

Recovering from codependency requires me to be hyper vigilant about so many things. I have to be aware of boundary setting, or what behaviors are not okay with me. I have to be able to communicate my needs while still being concerned and caring for the other person’s well-being. I can’t be selfish. I have to be willing to let go of control and accept that relationships have two sides both with standards and expectations. I can’t be a dishrag and let my partner rule my life. I had a lot of work to do to understand what my own individuality looks like. Through codependency recovery I have learned to value of my own self-worth and self-esteem, and my own likes and dislikes. Humility has taught me my right size and the very important fact that I can only control my own actions. I can’t control the actions of others. There’s a lot to remember.

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke put it this way.

Once we realize that even between the closest human being infinite distance continues to exist, a wonderful living side by side can grow up if they succeed in loving the distance between them, which makes it possible for each to see the other whole against the sky. A good marriage is that in which each appoints the other guardian of his individuality.

An ideal intimate relationship whether marriage, friendship, or partnership have the ingredient of accepting the other person as an individual with wants, needs and desire that not always coincide with our needs and wants. That is where acceptance lives and respect is born and above all trust.

Tips For Maintaining Individuality In A Loving Relationship

Limited text messages to partner, spouse, friend – not to be over bearing and snoopy.

Limited phone calls – everyone works, no need to be on the phone at all times of the day. There is plenty of time to discuss later.

Relationship with friends meeting friends on a regular basis, on the weekend too, without feeling guilty that a partner is on his/her own during a weekend night.

Having one’s own interest groups that have nothing to do with a partner, such as a book club, playing mahjong, or a special recovery meeting.

Going solo at the gym or learning a new skill by yourself without worrying that a partner would enjoy it too, but rather sharing all these new experiences later.

Traveling solo like visiting an out of town family member on your own.

Being present while with a partner, enjoying the moment, and not thinking of 10,000 other things that need to be done.

I am, and need to be, myself. And you are you. We can love each other with balance and care, as long as we can trust ourselves not to slip into old habits that can hurt.

The post Maintaining Individuality While Loving Another appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

Overcoming Negative Communication Patterns

Where there are negative communication patterns, codependency reigns. Codependency often develops when children are not encouraged to understand what’s happening around them and express their thoughts and feelings. Stifling expression is very common in families with Substance Use Disorder (addiction), but is also a function of all unhealthy family systems. When feelings are repressed or held inside, unhealthy communication results.

3 Types Of Negative Communication

You may recognize some of the results of feelings and thoughts that can’t be expressed because loved ones can’t or won’t listen. Being angry and acting out that anger. Feeling depressed and isolating from others. Blaming others and feeling resentful. You may be communicating in 1 of 3 ways: aggressive, passive, or passive aggressive. Others experience these types of communication in a negative way and may mirror your behavior back to you.

1. Aggressive Communication

Here you find yourself being a bully:

Complaining

Blaming

Yelling

Threatening

Dominating

Intimidating

Perhaps, being physical such as throwing things or hurting someone.

You enjoy other’s pain and tend to humiliate others. Also, you tend to be impulsive and react to your thoughts and feelings without examining issues. You are feared by others and you enjoy their discomfort and fear. This is a way to keep others away from you and to avoid taking responsibility.

Aggression comes from unresolved anger and instead of coping with that anger, you act out in your own way, similar to how the addict acts out with inappropriate behavior.

2. Passive Communication

This often happens when you give up. You don’t express your needs at all, but hibernate and withdraw from life and living. Passivity can also look like anxiety, depression, and the “poor me’s.” You cower in the face of adversity. You don’t use direct communication, you agree with everyone, you apologize for everything (including things that aren’t your fault), and you let the dysfunction rule your life. You have no sense of trust in yourself and you depend on others instead of taking responsibility for yourself. Perhaps you make excuses for the addict, perhaps you buy him his alcohol so he won’t yell at you, and perhaps you choose to lie in bed with the covers over your head. In this manner, you basically opt out of life.

3. Passive-aggressive Communication

This is a combination of the above 2 styles where you appear to be passive, but in reality, you are acting out of anger. This can be done in a subtle way which can be confusing to others. Here, you use sarcasm in your communication, drop snarky comments, act rudely, and feel smug about your communication. You are resentful and angry but cannot express feelings appropriately. This style lets you act aggressively in a sly manner as you undermine basic communication. This is the style of back-handed compliments – a compliment with a nasty zinger attached. You know when you’ve said a really good passive-aggressive statement when you are smirking on the bomb you’ve just dropped.

Overcoming Negative Communication

The problem with negative communication is that people around you do not respond to you the way you’d like. You work on becoming assertive. Changing your communication pattern can be difficult, even though you recognize it needs to change. You may benefit from counseling to help change a life-long pattern. Healthy, assertive communication depends on prep work and communicating in the moment.

Healthy Communication Prep Work

Feeling your feelings

Keep the focus on yourself

Doing affirmations daily (these are positive statements about yourself)

Exploring what you are grateful for

Focusing on your positives

Recognizing that you are a valuable person with EQUAL rights (such as being treated with respect, being accepted as to who you are, etc.)

Above all, accepting who you are

Healthy Communication

Examining your own behaviors to see if they are healthy

Accepting you role in changing your communication style and in communicating with others

Focusing on the positives of others

Listening, listening, and listening some more

State your thoughts and feelings directly, using phrases like:

“I statements” such as “I feel angry when…”.

“When you____________________, I feel_______________.”

Allowing others to communicate in a healthy manner and supporting this

Compromising and accepting compromise

Long-term communication patterns can be difficult to change, but in order to deal with others, this is a major step. You will find yourself feeling better as you engage in such communication and will find that others may also want to change their styles as well.

Visit Recovery Guidance to find therapists, counselors, and other treatment options near you.

The post Overcoming Negative Communication Patterns appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

Overcoming Shame

Overcoming shame is not easy. Many of us have been shamed in childhood as well as adulthood. Remember that shame is a feeling that lies for it says that you are a horrible, terrible, sick, weak, dysfunctional person. While guilt is about taking responsibility for behaviors and making amends, shame is about feeling awful to our core. Within shame, we struggle to see our positives and often give up hope on ourselves as we feel we are not ‘fixable.’ But there are ways to get out of shame.

Become Aware:

Learn as much as possible about shame because such education is the first step in understanding the toxicity of shame.

Learn to change the negative voices in your head. You no longer accept your own self shame which often repeats the shaming messages given to you in the past. Reframe the negative voices to positive ones by focusing on your virtues.

Accept:

Acknowledge the shame to yourself. This is a way to begin to let go of all of negative beliefs and feelings that can keep you trapped.

Accept the child within who was shamed. This allows you to see that you were only a child when this happened and you could not have done anything about it.

Talk to others about your shame. If kept secret, you won’t recover. Expressing how you feel is a beginning step to honoring your own realities.

Journal about how you have been shamed. This also helps to externalize the internal pain.

Take Action:

Find supportive family and friends.

When you make a mistake, realize that it was about a thought, feeling or behavior and not about WHO you are.

Watch out for a shame spiral. If you start to feel shame, you need to immediately do things to get out of it before it spirals out of control, like:

Read

Write

Play healthy video games

Go for a walk

Play with your pet

Focus on your strengths and who you are as a beloved human being.

Practice staying in the moment, instead of dwelling on the past and fantasizing about the future.

Attend 12-step meetings such as Codependency Anonymous.

Seek out a therapist who focuses on addictions and codependency. This may be individual counseling, group counseling, and/or family counseling.

Don’t attend places shamed you such as a church that doesn’t honor who you are (such as if you are LGBTQ or have been shamed for having an abortion).

Use affirmations. Affirmations are positive statements about yourself. Say them out loud, internally, or post messages around the house that are affirming statements such as, “I’m a good person” or I deserve the best in life.”

Learn how to be assertive (see article on communication patterns). By being assertive, you take control of your own life and your relationships with others.

Hold people accountable for how they shamed you. You can do this by writing a letter (to a living or deceased person) and either send it or burn it as a way to let go of what others have said and done to you. Or confront them if this feels appropriate.

Remember that the person and/or institution that shames you are the ones with a problem.

Shame gives us a license to hate ourselves. We need to focus on how to overcome shame and focus on our strengths. Finally, remember that you are a good person to the core and that you will not accept shaming behavior from anyone, including yourself.

Visit Recovery Guidance to find therapists, counselors, and other treatment options near you.

The post Overcoming Shame appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

William White Interviews Jerry Moe

A rare conversation about children affected by addiction from two pillars of the recovery movement. William L White, the premier addiction treatment historian and pioneer recovery advocate, interviews Jerry Moe, the premier advocate for the needs of children impacted by addiction

Introduction by William White

For more than thirty-five years, Jerry Moe has been one of the most singular advocates for the needs of children affected by addiction. Jerry Moe has a Master’s degree in education and counseling, but no academic program now in existence in the United States could have prepared him for this life mission. Much of the historical work in this area as a culture has focused on the effects of addiction on infants and young children (via the child welfare system, the primary school system, and child-focused therapy) or on providing support for affected teens (via student assistance programs, Alateen, or varied counseling programs). Much of Jerry’s clinical work has focused on the neglected needs of those who lie between the developmental stages of infancy and childhood on the one hand and adolescence and young adulthood on the other. I recently (January 2015) had the opportunity to interview Jerry about his work with “tweeners”—children from age seven to twelve—at such treatment facilities as the Betty Ford Center, Sierra Tucson, and the Sequoia Hospital Alcohol and Drug Recovery Center.

Bill White: Jerry, like so many of us who work in this field, your entrance begins with a very personal story. Could you briefly recount how that personal story led to your involvement and subsequent leadership within the field?

Jerry Moe: What a joy and honor it is to do this with you today. My story begins at age fourteen, when I was fortunate and blessed to find Alateen. I became a regular participant in Alateen and had a wise sponsor who was very clear that we were going to work all the Alateen steps. This was a pivotal point in my life, shaping my response to my father’s alcoholism. It helped me to look inward and begin my own healing journey. I became an Alateen speaker. I’d attend Alcoholics Anonymous conferences where there would be an AA speaker, an Al-Anon speaker, and an Alateen speaker. Filling that latter role was an opportunity to share my experience, strength, and hope and convey how teenagers can recover from this family disease. I was young and naïve enough to not realize what a big deal it was to convey this message in a room filled with hundreds of recovering people. Unfortunately, Alateen is the only Twelve-Step program with an age limit. At twenty-one, I faced a dilemma. My sponsor, who gratefully was still guiding me, suggested I go to Al-Anon. I started going to Al-Anon meetings, but it wasn’t a good fit. This was long before Adult Children of Alcoholics Al-Anon meetings, or CODA [Co-Dependents Anonymous]. After a few months, my sponsor suggested that I become an Alateen sponsor. I 2 went through an interview with group representatives and district representatives before taking on this role. The neat thing about it, Bill, was that my Alateen group coincided with a very popular Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, and a well-attended Al-Anon group. It was an evening of Twelve Step meetings for the entire family. Over the next few years, this Alateen group grew to between forty and sixty regular participants.

Bill White: Were many younger children involved at that time?

Jerry Moe: Ten and twelve-year-olds and sometimes even younger children began to show up for this meeting. We’d do a group conscience and the teens would always say, “Oh yeah, let a younger child come in. They need help, too.” But after two years, what became clear was how difficult it was to meet the developmental needs of such a wide age span. I’d often wondered as a young adult how my life might have been different if I’d been helped when I was seven or eight years old instead of fourteen. That decision to focus on the younger kids was the beginning of my professional journey. I never could have anticipated what would unfold in the years ahead. Early Career

Bill White: When and where does that professional journey begin?

Jerry Moe: That journey began at the Delancey Street Foundation during my undergraduate work. I had this wonderful advisor who helped start the Haight-Ashbury Clinic and who believed that the best learning takes place outside the classroom. So I did an internship at the Delancey Street Foundation. What I did within this therapeutic community was help residents prepare to take the GED exam. Most of those I worked with were recovering alcoholics and addicts who had spent a lot of time in the criminal justice system and were now putting their lives back together. I found that I really enjoyed working with this population, and the experience also reinforced my thinking about the value of prevention. I was struck by the possibilities if these folks had been reached when they were younger—how the trajectory of their lives could have potentially been so different. After graduation, I was working in special education in the Redwood City School District. Based on my professional education and experience in Alateen, I created a program for younger kids. Alateen comes under the auspices of Al-Anon Family Groups, and they weren’t looking to sponsor a program for kids under the age of twelve. So, I created a weekly one-hour program to serve these kids. It was an education/support group experience, specifically for kids growing up in families affected by alcoholism and other drug addiction. I piloted that program at the Salvation Army’s Clinton House in Redwood City, California. Much to my surprise, it was very well-received with a group of just little kids. Now my challenge was to find a permanent home for the program. At the time, there was Children Are People, founded by Rokelle Lerner and Barbara Naiditch in Minneapolis-St. Paul; Claudia Black was working with young kids in Washington, and Phil Diaz was doing Project Rainbow in New York. I just didn’t know about these programs or the efforts by others to support this special population.

Bill White: If I remember right, you found that home within a series of addiction treatment programs. 3

Jerry Moe: That is correct. I first took the children’s program to Sequoia Hospital Alcohol and Drug Recovery Center in February 1978. It was a twenty-eight bed, inpatient addiction treatment program. When I first met with the administrators, I told them that if we offered a children’s program that was open to all children, not just the children of patients in treatment, that I would guarantee ten inpatient admissions and five outpatient admissions a year, directly a result of that program. Today, I laugh at such boldness. The administrators looked at each other quite skeptically. My response was, “Well, if someone needs to bring the little kids to group and if those people are also participating in Twelve-Step meetings while the children’s program is taking place, there’s a chance that we’re going to begin to change the family system from the other side of the equation. Instead of waiting for the alcoholic or the addict to seek treatment, let’s help the family. Maybe change in the family system will accelerate help-seeking on the part of the addicted family member.”

Bill White: That’s a remarkable argument for that time period.

Jerry Moe: It was the application of Dr. Murray Bowen’s family systems theory from graduate school. Change one part of the family, and the whole family’s going to change as a result. The administrators at Sequoia bought my argument, and we began to see adults entering treatment as a result of the support we were providing other family members. I wanted to work in the treatment field full-time with little kids, and it took a number of years to make that happen because that job didn’t exist. Before I forged such a position, I worked as a detox counselor, a counselor on the midnight shift, a family counselor, and a continuing care counselor—all of that gave me the basics of working in this field before I began my full time work with children. My work continued at Sequoia, then at Kids Are Special, then back to Sequoia, Sierra Tucson, and then to the Betty Ford Center, where I have been since 1998. All of these later positions focused on work with children. Through this work, a new model emerged. The traditional model was weekly group for sixty to ninety minutes. There would be boys and girls just about to make a breakthrough—to talk about hurting inside, the guilt and shame they felt, or their fear that they were going to lose their parent, and then time would run out. We’d meet again the next week, and it wasn’t like the Dallas TV show where you’re left with a cliffhanger and the first thing you see is its resolution. In real life with these kids, you had to start all over the next week. By the end of 1979, we began to hold weekend retreats with the alumni organization at Sequoia Hospital, and I’d run a children’s program parallel to the adult program. Over the course of a weekend, there was time for recreation, social interaction, and play. We’d deepen the process because there was more time to build relationships and create safety with the children. In 1985, we started summer camp for children of alcoholics. It was specifically for kids who were participating in the Sequoia program because we already knew them and realized that they could benefit from a six-day, five-night camp experience. And it was a camp, in every traditional sense—with marshmallows, campfires, hideand-seek, and swimming, but also with a focus on dealing with alcoholism and other drug addiction in their lives. I’m proud to say that in early July 2014, I went to the thirtieth annual gathering of this camp. It’s still helping a lot of kids in Northern California, and I’m blessed to be invited back to participate every year.

Bill White: How did this camp model evolve into your later work? 4

Jerry Moe: What fortuitously happened was that we used the camp model at the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACoA) conferences. In the mid-1980s through the 1990s, NACoA held a national conference. Someone had the idea to do a children’s program during the Conference while their parents went to lectures and workshops. I was approached to direct this children’s program. Sierra Tucson often sponsored this children’s program. That’s how I met Bill O’Donnell, who was the CEO of Sierra Tucson at the time. At one point he said, “Jerry, would you consider coming to work at Sierra Tucson and creating a five-day children’s program that would run parallel to the family program?” That was how I came to work at Sierra Tucson from 1991 to 1998. The model came directly from the camps. Betty Ford Center Children’s Program

Bill White: And how did the opportunity then arise to move to the Betty Ford Center?

Jerry Moe: The Betty Ford Center, from its inception in 1982, was doing work with children, but it was done on a piecemeal basis. Quarterly, one of the family counselors would do a couple of days with kids and also do something with parents. But it wasn’t until 1996 that the Betty Ford Center received a generous philanthropic gift and hired someone to develop a fulltime children’s program. I was called upon to serve as a consultant to review the program and offer suggestions based on the model that I’d been working on for so long. Then, in 1998, I was invited to go to the Betty Ford Center and create the children’s program that we continue to run today.

Bill White: For those that are not familiar with that program, how would you describe the structure of that program?

Jerry Moe: There are a number of program elements. The community program is a four-day, all-day program open to all boys and girls who come from a family where alcoholism and/or other drug addiction has been a problem. It was Mrs. Ford herself who insisted no child ever be turned away due to an inability to pay. The first two days, Bill, are just for the children, and we use an experiential play model to teach kids about the true nature of alcoholism and other drug addiction. We teach them a variety of communication skills and coping strategies—ways to take good care of themselves. Then during the last two days, a parent, grandparent, or a foster parent—or maybe it’s the twenty-one-year-old who’s just been through a young adult program at a treatment center—will come and participate with the child. We also do a school-based program. We partner with a local school district, and the school principal and the counselor pick children to participate. The principal sends home a letter inviting kids because we need parental consent. We do a four-day program at the school where boys and girls are pulled out of all classes to attend the program. Many more of the boys and girls in the school program live with active addictions, so we change the model to talk more about safety plans and safe people—ways to just stay safe. Then the school counselors do follow-up. A third element is for kids who live locally. Every Wednesday night is Continuing Care Night. It’s a one-hour group much like the model that originally was created at Sequoia Hospital. It’s an hour of age-specific group support for the children who’ve been through the Children’s 5 Program. If you’re an alumnus of the Betty Ford Center Children’s Program and you’re a teenager, you go to Alateen and then there’s an AA and Al-Anon meeting for the grown-ups. So, it’s an evening where the whole family can come to deepen their healing.

Bill White: How would you describe the goals or core principles that underlie the Betty Ford Children’s Program?

Jerry Moe: Our focus is on helping boys and girls understand the true nature of alcoholism and other drug addiction, for them to realize that it’s not their fault, they’re not to blame, they didn’t cause it, and they can’t cure it. We also teach them about their own risk for developing addiction. We emphasize creating a place where kids feel safe and they can—through art, stories, writing, and role-plays—begin to share their own experience of what’s happened in their lives. And it’s also about play—an opportunity for boys and girls to be children. While we’re engaged in a lot of therapeutic activities throughout the day, there’s also swimming, hide-and-seek, playing ball, having meals, and social interaction. Play is an incredibly important part of the program.

Bill White: I seem to recall you’ve adapted and delivered the program in some very different cultural contexts.

Jerry Moe: Yes, I’ve been blessed to work with Native Americans. Through Don Coyhis and White Bison, I have learned a great deal about Native culture and how to incorporate stories and rituals into our work with Native children. Our staff has done a children’s program in Alkali Lake in Canada with a tribe that is a model of recovery and healing. I’ve been a frequent presenter and worked with children at the Seminole Wellness Conference in Florida. The Betty Ford Center is located in Coachella Valley, so we also serve MexicanAmerican families by offering bilingual groups. It’s typical that the boys and girls from these families speak both English and Spanish, but often the parents are Spanish-speaking only. Children often go back to their Native language when things get emotional. I have been both an attendee and presenter at the annual Counseling and Treating People of Color Conference. Dr. Frances Brisbane has helped me to become much more culturally competent in this work.

National and International Work

Bill White: Is the BFC children’s program offered in other locations?

Jerry Moe: There are three Betty Ford Center Children’s Programs. In addition to our program here in Rancho Mirage, California, we operate a program in Irving, Texas, that encompasses the Dallas – Fort Worth Metroplex. We also have a Children’s Program in Aurora, Colorado, that serves the greater Denver area. Mrs. Ford was instrumental in the Children’s Program expansion. She knew that few communities offered such programs and that it would benefit so many boys and girls. Now with the merger of Betty Ford Center and Hazelden, the thought of expansion is very exciting.

Bill White: Have you been called upon to do training and consultation to help replicate or adapt the Betty Ford Children’s Program at other sites? 6

Jerry Moe: Yes, we have partnered with Brighton Center for Recovery in Michigan, and the Houston Council on Alcohol and Drugs to offer the Betty Ford Center Children’s Program Training Academy. We train key staff for two years to develop and then independently operate a children’s program for their local communities.

Bill White: I know you’ve taken this work internationally in such countries as Russia, China, and Africa. Have you been struck by how similar the experiences of affected children are across these cultures?

Jerry Moe: In Russia, China, and Ghana, I was blessed to work directly with little kids. In all three places, I didn’t speak their native tongue, so there were interpreters. While I did a crash course in their culture and tried to learn as much as I could in a short amount of time, I was struck wherever I went that little kids are little kids. They’re hurt by this disease. They respond so quickly and so favorably to the tools and techniques we’ve developed over the years. What I’ve always wondered is: Will these same games and activities work in other cultures? How do we need to change it up a little bit? How do we best meet their needs? In working across cultures with children challenged by addiction, the similarities so outweigh the differences. To touch little kids’ hearts is the key to all of it. While what we do is incredibly important with children, it’s how we do it, with love, with kindness, listening, and caring that’s the most important part of all.

Evolving Status of Children’s Programs in the U.S.

Bill White: Jerry, let me take you to a larger discussion about where you see the field. First, could you elaborate on the status of family and children’s programs when you entered the field?

Jerry Moe: At the time I entered, this work had already begun, but it wasn’t until the founding of the National Association for Children of Alcoholics in 1983 that there was a vehicle to network and expand such efforts. Before then, those of us trying to do this work knew little of each other. There were pioneers whose work influenced NACOA and its mission, such as Stephanie Brown’s ground-breaking work with adult children and Claudia Black’s early work, including her first book, My Dad Loves Me, My Dad Has a Disease. Sharon Wegscheider-Cruse was doing amazing work with families. I remember ordering Robert Ackerman’s book, Children of Alcoholics: a Guidebook for Educators, Therapists, and Parents, and it arrived in brownwrapped paper, as if people would have been ashamed to have others know they had ordered it. We had those early resources, but we had yet to become a mobilized force within the field and the larger culture. Bill White: So, in many ways, NACOA became the kinetic detonation point for the movement dealing with the needs of families and children. Jerry Moe: Most definitely. I am not a NACOA founder. I’m part of the second wave that came after the founders. I was doing work with children when NACOA was founded but my involvement came later. NACOA was the umbrella embracing some extremely gifted and talented counselors, writers, and advocates. In addition to Claudia Black, Stephanie Brown, and 7 Bob Ackerman, there were Cathleen Brooks, Sharon Weigsheider-Cruse, Sis Wenger, and Tim Cermak. What incredibly rich resources! NACOA helped to validate and strengthen what I was doing, and provided a key support mechanism. This talented and gifted group of folks both challenged and stretched me to further grow and develop.

Bill White: So much of this seminal work was done in the 1980s and early 1990s. Have we progressed beyond that pioneering work, or have we as a field lost some of the focus on children?

Jerry Moe: We’ve progressed in many ways, Bill. I think about the work that gets done in the schools with student assistance programs and with prevention. Mrs. Ford always said that we need to go to where the kids are, and where are the boys and girls? They’re in schools. Children’s programming needs to reach beyond the walls of addiction treatment. It needs to be open to all kids. There’s also exciting work being done in the faith community and with Drug Courts. The National Association for Children of Alcoholics now works closely with SAMHSA and with the White House Office on National Drug Control Policy. You see how far we’ve come. But while we’ve made progress, there are still so many boys and girls out there who are hurting and who don’t have access to the education and support that they so desperately need. We need more clinicians and programs to address this issue.

Treatment Program Response to Needs of Children

Bill White: What do you think are some of the most important steps that inpatient and outpatient addiction treatment programs can take to better address the needs of affected children?

Jerry Moe: One of the first things that treatment centers can do is offer family and children’s program services to the general public—to affected families and children whose addicted family member is not in primary treatment or in stable recovery. It’s time we widened the doorway for all affected families. Such families can also include the men and women in long-term recovery who want to involve their children in support services to help break intergenerational cycles of addiction. The second thing treatment centers can do is address parenting issues in recovery. This is a tough one because there are so many critical things to address in treatment, but there needs to be a focus on parenting issues in early recovery. Right here at the Betty Ford Center, there may be a mom who has been in treatment for a few weeks who today has a spiritual awakening and realizes the devastation this disease has wreaked on herself and others, particularly her children. And she may also come to realize the similar devastation it did to her when she was growing up. She now sees the horror of this repeated cycle that she was so adamant to avoid. We can help empower folks in early recovery to begin to balance their own recovery with the needs of becoming a more effective parent, one day at a time.

Resources

Bill White: I know you and others have created a number of resources that would be of great help to programs wanting to amplify their focus on children. What’s the best way for people to access those resources?

Jerry Moe: Over a dozen years ago, the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACoA) partnered with SAMHSA to create the Children’s Program Kit. All of the NACoA people who worked on the Kit donated their services to create this. It remains an excellent resource for working with elementary, middle-school, and high-school youth. About one hundred-eighty thousand Kits have been distributed across the United States. The good news today, Bill, is that NACoA is in the process of finishing a major revision of this Kit. People can go to the NACoA website, www.nacoa.org, and order that kit for free. There’s also a Native American-specific kit that Don Coyhis and White Bison helped put together. The kit has been used in a variety of settings, from treatment programs, schools, family clinics, mental health programs, private practice settings, church youth groups, and Boys and Girls Clubs. We are always trying to create new resources for our alumni kids, ones that reinforce the major messages and strengthen the skills they learned in the program. One exciting development is the Beamer Project. Tom Drennon and I created a series of books revolving around a ten-yearold named Beamer. His head is shaped like a light bulb, and it actually changes colors as his feelings change. Both of Beamer’s parents have been trapped by addiction. Children readily identify with the many challenges he faces and the solutions he utilizes to positively cope on a daily basis. This has become wildly popular with the kids and is being developed into animation with hope of wider availability.

Child Vulnerability and Resiliency

Bill White: I’d like you to reflect on some of what you’ve learned about children through your years of running children’s programs. How do you now view the vulnerability of children and the resiliency of children?

Jerry Moe: I still get to do groups with boys and girls, not as often, but I am still moved and refreshed by this contact. Many are so hurting, yet have mastered the ability to look good on the outside. When boys and girls have adversity or challenges in their life, many have the blessing to go home to a safe place for support in facing these challenges. But for boys and girls who grow up in families with alcoholism and drug addiction, the dilemma is that home is often the source of those challenges. So, these kids are incredibly vulnerable, but you said it: so many are resilient. I never forget the longitudinal study of Dr. Emmy Werner, who is often referred to as the “grandmother of resilience.” She studied the children of Kauai for almost 50 years. Many of them were children from alcoholic and drug-addicted homes. What I most recall from this study is that the presence of a nurturing, caring adult in a child’s life can make such a difference. I look at the way that we structure the children’s program, and it’s really a strength-based model. One of the most important lessons I’ve learned through the years is children don’t care about how much you know until they know about how much you care. So, bringing your heart and soul, developing that relationship, playing with kids, listening to boys and girls is so important, and it’s important because of its ability to move children from a position of vulnerability to a place of resilience. 9 It’s being in a group with other kids who are going through the same exact thing, knowing they’re not alone and that there are other kids like them. At the Betty Ford Center, it’s about sending kids a newsletter every ninety days in the mail, and a series of Beamer books to reinforce those major messages. We make a promise to kids going through our program that we’re going to always be here for them. They get an 800 number that they can call, and e-mail addresses where they can reach us when they are hurting or scared, or even when they’re joyous because something good is happening in their lives.

Breaking Intergenerational Cycles

Bill White: You referenced earlier this propensity for addiction to move from generation to generation within families. Given your experience, what strategies could be used to help break such cycles of addiction?

Jerry Moe: The best gift parents, grandparents, or an older sibling can give to a child is the gift they give themselves, and that starts with getting clean and sober. I’ve worked with so many boys and girls who would give anything to see a parent not just get well, but to then consistently be in their lives. The plea from the child is to play with me, love me, teach me, keep me safe, respect me, honor me, listen to me. When those things are present, cycles of addiction can be broken. When I have the opportunity to talk to people in early recovery, I always tell them that the greatest devastation of the disease of addiction is that you cannot consistently love the people who mean the most to you because the disease keeps getting in the way. I suggest three remedies. Number one is to work on your own healing. That is the foundation. Secondly, begin to rebuild relationships with your children (or your younger siblings.) And it’s hard in early recovery because so much else is going on. But I suggest that even if it’s just once a week for thirty minutes, set time aside, put everything else out of your world and just show up and play with those little ones in your life. That’s what boys and girls want the most; they want time and positive attention, and addiction robs everyone in the family of both. Then, thirdly, I always suggest to folks in recovery to find a program or resource that can offer support for your child. I truly believe that one of the ways to begin the process of making amends to the people we love is to see that children have such support, whether it is a formal program or a counselor or a youth minister—someone who will just sit and help explain what’s going on in a way that the child can understand. This is a safe person to whom children can talk. Without help understanding this in an age-appropriate way, boys and girls often make up a story to make sense of it all. Unfortunately, those stories are often far off-base. “Did I do something wrong? Is it my fault?” Such a miscast story may continue to shape their lives and thwart them from realizing their true potential.

Bill White: Listening to you makes me wonder if we’re at a point where we need a parenting effectiveness in recovery training program built in to all treatment programs, if not during primary treatment, then as part of continuing care.

Jerry Moe: Bill, I agree with you wholeheartedly. The Betty Ford Center held a conference in 2010 in Washington, DC, where we explored parenting and its role in the treatment and recovery process, especially in terms of breaking the intergenerational cycle of addiction. This is an area 10 that needs much more emphasis and programming, particularly for those in early recovery. Addressing effective parenting in recovery and healing the parent-child relationship are critical issues that we can’t afford to neglect.

Media Coverage of Affected Children

Bill White: I’ve watched the media coverage of children affected by addiction, if it’s covered at all, and what’s there seems to primarily focus on the damage done to children. I don’t see the flipside of the story, which is the story of resilience and recovery of children within these families. Would you agree with that critique of the media?

Jerry Moe: This is too often the case. Through the years, I have been invited on national shows that wanted to primarily focus on the disease and how it devastates the whole family. No thanks. What’s missing is media coverage that speaks of hope, recovery, and healing. I think it’s something that has dogged our entire field, but there are wonderful exceptions. I worked with Nickelodeon News and Linda Ellerbee of Lucky Duck Productions to produce a thirty-minute Nick News Special, Under the Influence: Kids of Alcoholics, that initially aired in November 2010. We focused on solutions and hope. It featured five adolescents, all from different backgrounds, across the United States, and all living in various family contexts: some in recovery, some dealing with relapse, and some where the addiction remains active. The show looked at how children learned to positively cope with the challenges they face in their lives. This show won an Emmy Award.

Closing Reflections

Bill White: As you look back over a long and what has already been a significant career, what do you personally feel best about?

Jerry Moe: We are developing a growing body of scientific evidence that the work we are doing with children really makes a difference. I’m proud of the Children’s Program Kit that is free, has been so widely distributed and used to change the lives of countless children and families. There are many adults who I worked with as kids who still keep in touch. It’s wonderful to see that the seeds we planted in their lives have born such wonderful fruit. But it’s more than just the kids; it’s watching families heal, and, for me, it’s having alcoholics and addicts who say thank you, I’m letting go of my guilt and shame. It’s watching families get beyond their disease to live lives of recovery, hope, and joy. It’s seeing adults become good citizens and responsible parents and passing that on to the next generation. Today, we’re seeing people stand up and say, “I’m in recovery.” It’s recovering alcoholics and addicts shifting from how their disease hurt their children to how their recovery is benefitting themselves, their families, and their children. That’s a big shift.

Bill White: We will have some readers of this interview who are interested in potentially devoting their lives as you have to affected children. Do you have any closing guidance that you would offer those individuals? 11

Jerry Moe: Well, the first thing I’d say is, “Come on board, we need you.” We need people who bring energy and passion. Bring your heart and soul to this work on a daily basis. Self-care is incredibly important. This work can be exhilarating and exhausting, so finding balance between the work and self-care of oneself and one’s own family is very important. Be patient with children, letting them be kids and letting them be silly and make mistakes. It is equally important to be patient with the systems that we work with as we push them to make substantial changes in how they operate. Celebrate the wins—big and little—and experience the joy in the journey. What we do in this work is never an event; it is a process that we must both guide and let unfold. Reach out to people who have done this work before you and learn lessons from them, but then be brave and courageous enough to take this work to new levels. Parents need to be an integral part of what we do with children. It’s essential that we empower the grownups taking care of the children to work on their own healing and to develop the tools to become effective parents and grandparents and older brothers and sisters. Cultivate a good sense of humor in order to always be able to laugh and maintain a balanced perspective on what we are doing. I was interviewed not long ago by someone who was new to this issue who said, “My goodness, there must be so much pain in what you do.” I work with little kids who are in pain, who describe their pain, who act their pain out, who then courageously talk about it. But to me, I always think of the joyous gift I have found in this work—to witness nine year olds or twelve year olds doing such healing rather than painfully waiting until they’re forty years old or sixty years old or eighty years old to do that.

Bill White: Jerry, this is a wonderful place for us to stop. Thank you for taking this time to share what has been an incredible personal and professional journey.

Jerry Moe: Thank you, Bill.

Acknowledgement: Support for this interview series is provided by the Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) through a cooperative agreement from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). The opinions expressed herein are the view of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), SAMHSA, or CSAT.

The post William White Interviews Jerry Moe appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.

March 31, 2018

4 Causes Of Damaging Shame

Some people grow up feeling good and strong, while others carry the burden of damaging shame that persists no matter how much love they receive or great their achievements later in life. There is a difference between shame and guilt. Guilt can be the motivator of change, taking responsibility, and making amends, but shame is always a damaging feeling that keeps us trapped in misery. Shame lies to us and tells us we are no good, terrible, horrible human beings, and we feel this to our core.

The first step to healing is understanding that shame comes from influences outside of us and is internalized as reality.

Damaging Shame Begins From Dysfunction

Shame is developed through a variety of ways. John Bradshaw, author of the recovery classic Healing The Shame That Binds You, and Fossum and Mason, authors of Facing Shame: Families in Recovery explain it this way.

We learn shame just as we learn guilt, but shame is the result destructive conditioning. Shame begins from relationships that are the most valuable to us and within the systems that are most important.

Four Causes Of Damaging Shame

1. Unhealthy family systems

The family is the most important aspect of growing up and becoming functional or dysfunctional. Extended family generations can be a source of shame.

For example, if one grew up in a family where there is poverty, or abuse, or perhaps, having multiple generations of family members who end up in prison, we learn shame by believing that we are a bad family and therefore, I am a bad child. Also, shame-based families have unhealthy coping skills and may be controlling, non-nurturing, poor communicators, arguing and fighting, and blame the child for all of the family issues. Also, shame-based children may have been abused – physically, sexually, emotionally, and/or spiritually – such trauma in and of itself is shaming as the child blames her/his/them self for the dysfunction and feels shame that this has happened. Being teased, humiliated, blamed, purposefully shamed, and told to keep secrets also leads to shame. Other shame comes from being abandoned; again the child feels she is so bad, that the parents want to have nothing to do with her.

2. Shame in the educational system

Shame can be developed through school with teachers, principals, and other personnel shaming students for who they are.

For example, the school system knows that Shannon’s mother is a drug addict and is currently in prison. She may have that pointed out to her, i.e., “You’re going to grow up just like your mom.” Similarly, a child may be told: “Why don’t you act like your siblings” or “You aren’t as smart as your brother.” Also, peers may shame the student; for example, “You smell” and call you “Smelly” or make fun of you because your dad has left home. They may know family history such as, “Your cousin committed suicide, why don’t you do the same thing?”

3. Shame in religious systems

Unfortunately, some religious institutions cultivate shame in its members. Having to believe a certain way, follow dogma, being told you were born in original sin, having a punishing/punitive god, and other issues can be shaming.

Other shaming results from religious beliefs may include shaming about who you are (i.e., GLBTQ, your situation (divorced, living outside of marriage) or actually excommunicating you because of who you are or what you’ve done. Still other issues include the focus on perfectionism and righteousness (as defined by a church), the church telling you they are the only belief system (Christian churches telling you that Muslims are heathens, violent, non-god like), focusing on literal interpretation of religious texts such as the Bible, or even getting into religious addictive behaviors.

4. Shame in being different

Being different can mean so many things. It can be how you look relative to the mainstream, or people around you. For example, do you have piercings, tattoos or pink hair in a conservative community? It can mean having different culture from people around you (ie being in the minority). It can mean ethnic background that is not as respected as it should be for one reason or another. Your color of skin, belief system, religion/spirituality, sexual orientation, gender status, obesity, mental illness, physical disability can also be perceived as different from the norm and a cause for shame.

Within all systems there is an artificial norm projected, and those who fall outside of that norm are perceived and can be shamed as different.

All kinds of people live in every system, including families, schools, communities. Because everyone is different and equally valuable in his or her own unique way, there is no actual norm in humanity. Inclusiveness and acceptance is something that has to be taught in the same way intolerance is taught. Being different in closed societies (neighborhoods or region or family) or any of the systems above can bring about deep and lasting shame. Differences can set us up for being shamed and we internalize this shame instead of rejoicing about our differences.

Everyone Has Some Shame

No one has escaped feelings of shame. Parents or teachers may have called you stupid or hopeless. You may have experienced prejudice for one reason or another. Gay Pride, the “Me Too” movement are two examples of people using community acknowledgement to both heal from shame and lift the stigma. Healing begins with your personal acknowledging when and how you’ve been shamed and how the experience has caused you harm. Know that in whatever way you have been shamed, you are not alone.

The post 4 Causes Of Damaging Shame appeared first on Reach Out Recovery.