Collins Hemingway's Blog, page 6

March 7, 2017

Austen and MTM: Pleasantly Subversive

When the news came recently that Mary Tyler Moore had died, I joined millions of others in feeling a deep sadness at the loss of an actress who had lit up television during a relatively bland era. Before she was done, Moore won seven Emmy Awards and two Tony Awards, received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Comedy Awards, and was in the Television Hall of Fame.

In taking embarrassment into the form of high art, she found a way to make a case for all women to be treated with respect, whether the woman in question was a suburban housewife caring for her family or an enterprising single woman making her own way in the world. She proved her serious acting chops in the movie “Ordinary People” and many other films.

As I—along with many, many others—replayed some of the best clips from both “The Dick Van Dyke Show” and “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” I kept thinking that there was another connection to be made, but I couldn’t figure out what it might be until I was watching an hour-long retrospective. Early critics savaged Moore’s show for having a pug-ugly male lead—Ed Asner—a strange supporting cast, and a lead that no American audience would ever accept—not only a woman, but a “spinster.”

Then it hit me: Mary Tyler Moore was the Jane Austen of our era.

Think about it. At their height, Mary Tyler Moore (as Mary Richards in her TV series) and Austen (as a novelist) were single woman in their thirties, hitting their professional stride in a world weighted against women and thwarting them in a variety of ways big and small. Both experienced might-have-been relationships in their personal lives that at times brought reflection over loss—but never stopped their quest to move ahead alone.

In a time of great social tumult, both were quiet supporters of a better way. While some contemporary women were tough, intellectual advocates of better treatment for women (Mary Wollstonecraft in Austen’s day, Gloria Steinem and others in Moore’s day), Austen and Moore used gentle humor and social satire in their renderings of ordinary life. They made many of the same points as did the advocates, but in a way that was easier to accept because, in ordinary life, the injustice perpetrated was so palpably wrong.

Jane and Mary adhered to most social norms while subverting them.

Mary Richards, for example, was the only cast regular who called Lou Grant “Mr. Grant” instead of “Lou.” Her respect and deference were the basis by which she would haltingly question Mr. Grant. Step by step, she would walk him down some male-centered policy until his own logic proved he was wrong. In a similar fashion, Austen did not preach a moral as many of her sisterly novelists did. Instead, Austen let people like Mr. Collins and Mrs. Elton simply speak and act, demonstrating their selfishness and vanity objectively—aided at times with the gentlest of authorial irony.

The approachability of Jane and Mary, and their handling of ordinary domestic life and work, led readers and viewers not only to identify with them but to feel that they had their own personal relationship. Fans automatically spoke in terms of “my Jane” and “my Mary”—sister, aunt, BFF. One actress, who played a character who was mean to Mary on the show, received death threats. One suspects a similar reaction should anyone trash-talk Austen in front of Janeites.

Austen influenced numerous women authors in future generations—as well as men—while Oprah Winfrey and a generation of female journalists praised Moore for showing them how to achieve success while remaining themselves, how not to succumb to anger or despair while persevering. Putting a good face forward was not a way of swallowing pride at insult and disrespect but of subtly gaining ground while antagonists—male and female—were busy preening.

Jane Austen of the 19th Century and Mary Tyler Moore of the 20th Century: Sisters at heart!

What do you think—are these reasonable parallels? Are there others I missed? Who else might be the Jane Austen of our world?

P.S. I may be slow to respond to comments. I’m in Australia this week to deliver a series of talks to the Jane Austen Society of Australia in Sydney, Newcastle, and Brisbane, with a lot of travel and a huge time difference!

The post Austen and MTM: Pleasantly Subversive appeared first on Austen Marriage.

March 2, 2017

Impressions of Australia

On the week-long visit to Australia to discuss the time and works of Jane Austen with fellow Janeites, the schedule set up so that I had a day on and a day off, giving me the opportunity to see a little of the country-continent. This was a welcome change from my only other visit, a business trip in 1998, when all I saw was hotels and conference rooms—and Michael Palin of “Monty Python” fame in an elevator.

When my time in a new place is limited, my preference is to find one or two things to do and strike out on foot. With an early morning arrival, I promptly set off to explore Sydney after fueling up at the nearest eatery—a 7-11 selling urn coffee and Krispy Kreme doughnuts. I found authentic Australian food later. …

Weather in the country had been dreadfully hot in the weeks before my arrival—above 100 degrees Fahrenheit—but had cooled to the high-80s (about 30 in their Celsius), which made for pleasant if occasionally sweaty walks. Remember, it’s summer in the Southern hemisphere. At the Sydney talk, the day was so sultry that the dress code was casual. Ceiling fans shoved the hot air around, and the talk ended just as the skies unleashed a barrage of hail. I felt like I was back home in an Arkansas summer T-storm. When the hail abated, we dashed for the car, but on the way home got hit by several pieces so large we thought it was going to break the windshield (it didn’t!).

On a day off, I walked Oxford Street from the Paddington area of Sydney through Hyde Park to Sydney Harbor. (Many place names in Australia refer to the English homeland.) The street is lined with fashionable dress shops for women on one side and more specialized shops for male clientele on another. (All I bought was a pair of bicycle socks from a U.S. expatriate who had made his career in the Coast Guard, then met an Aussie girl and came with her here.)

Ancient Moreton Bay fig trees cover much of Hyde Park in Sydney

Ancient Moreton Bay fig trees cover much of Hyde Park in SydneyOne turns and goes downhill through Hyde Park, a cool respite populated with exotic birds and huge trees, including the Moreton Bay fig tree with its convoluted branches. The harbor is anchored on the right by the clamshell roofs of the famous Sydney Opera House and on the left by “The Rocks,” where a handful of the original stone buildings survive from the colony’s founding. Sydney’s first citizens were convicts transported from England for mostly petty crimes—in essence, England dumping its impoverished citizens on a largely empty land.

Sydney has a huge harbor with lots of coves—the city of 4.5 million wraps around almost too many coves to count. A two-hour cruise provided an appreciation of the scale of this beautiful city. Sydney’s Harbor Bridge is a magnificent structure, completed in the 1930s, which gave the people the confidence that they could create a city to rival any in the world.

I dined twice with members of the Jane Austen society at 5 Ways, an intersection of five streets in Paddington that sports a number of restaurants, including the Thai and Italian where we dined. Food is somewhat pricier in Australia than the U.S., but we landed upon pasta specials one night and did well for the sum spent. Bright and lively conversation in all three cities I visited convinced me of what one woman said, “Jane Austen has a way of bringing good people together.”

Paddington lace–wrought-iron metalwork–on colorful buildings

Paddington lace–wrought-iron metalwork–on colorful buildingsThe Paddington area is known for its ornate wrought-iron work on the front of houses, called “Paddington Lace.” These designs, along with the warmth, humidity, and subtropical plants, remind an American of New Orleans. As does the Mardi Gras celebration scheduled for the next weekend!

In Sydney, Susannah Fullerton, the president of the Jane Austen Society of Australia, took me along a hill on the south side of the Sydney Harbor, where our loop brought lovely views of the entrance of the harbor to the sea, along with the original lighthouse and gun emplacements that were still active in World War II. One stone path had been built by the convict laborers transported from England to Australia.

Detail of the wrought-iron metalwork known as Paddington lace

Detail of the wrought-iron metalwork known as Paddington laceThose who survived the year-long voyage, and the initial years of hardship and near-starvation here, were the hardiest stock. Having earned their freedom, they carved out a nation from a stingy land. (And, like settlers in the U.S., had often brutal encounters with the natives, a troubled legacy that lingers to today.)

My journey continued Wednesday with a 2.5-hour train ride north and west to Newcastle, like its English namesake a coal-producing town. The train went through densely forested hills and alongside Lake Macquarie. Efficient and fresh, the train gave me the opportunity to work on Volume III of my trilogy. Writing in a new location stimulates creativity.

Like the U.S. west coast, the Australian east coast can be hot and dry, and the danger of bush fire is serious. On one side, a fire had come right up to the railroad tracks. Recent rains had been very welcome.

In Newcastle, my host lived at the top of an area known as the Hill, and we walked on an engineering marvel of a pedestrian bridge that spanned several small headlands. We went only partway; the entire bridge tied together the beaches and port below with the upper parts of town. Later, we also strolled the main port area.

Though coal is still exported (a long line ships stretched into the distance offshore, waiting their turn to come in for loading), the steel mill shut down years ago. The closure was a severe shock to the economy, but Newcastle has rebounded and is now becoming a tourist destination and cultural center.

An author on parade must balance the number of books he hopes to sell with the number that one can physically carry. My arms are several inches longer than when I started. The people of Newcastle were particularly receptive, leaving me with much lighter bags to schlepp back.

Downtown of Brisbane, largest city in Queensland, still another port in Australia

Downtown of Brisbane, largest city in Queensland, still another port in AustraliaIn Brisbane, I stayed in an area known as Ascot, which has two racecourses, named of course for its English parallel. On Saturday, the men in their suits and the ladies in their finery strolled down to the horse track. Their return, after a hot afternoon and the consumption of adult beverages, left the ladies holding onto their bonnets while swaying on their heels.

Racecourse Road—a half-mile stretch of bars, coffee shops, restaurants, and interesting shops—leads to the Brisbane River. One eatery is called 5 Burroughs, named for the five divisions of New York City but feeling more like a rib joint in the American South. If Sydney felt like New Orleans with its upscale feel and wrought-iron work, Brisbane feels more like Charleston by the sea or Little Rock by the river. The local variety of cicadas begin to call the minute you get off the main street, even in the day.

On the river itself, with tall new buildings on three sides and a large cruise ship on the other, the air saturates a courtyard with the smell of curry. Dinner was at a restaurant at the old brick power plant, a huge structure that has been converted into theaters, restaurants, and other night-life venues.

I’m hesitant to generalize about a country from meeting only a dozen or so, but Australians are a gregarious folk. Everyone I met was eager to speak to me, eager to visit with a visiting American. Granted that I was spending much of my time with well-educated and well-read people, but even those I ran into on the street were engaged and interested in the world around them.

No doubt one reason is that Australia is an island nation—and a coastal country. Every major city is a port town. People look out to sea rather than inland. Out-country visitors are common, from all over the world. That may be why many Australians think of international rather than in-country travel. With few mountains to generate weather, the interior of Australia is hot and dry and relatively unpopulated. The big cities are all on the coast. Darwin is closer to Jakarta, Indonesia, than to any major Australian city. As one person in Brisbane put it, she can fly three and a half hours still be in Queensland. A little farther, and she can be in a different country.

Being part of the British Commonwealth and being the only nation of Western heritage on this side of the Pacific, Australians pay much more attention to international affairs, particularly American and English, than the average American.

After all, World War II came right to Australia’s door—Brisbane guns exchanged fire with Japanese ships in World War II, submarines attacked Sydney Harbor, and the battle of the Coral Sea stopped a fleet intent on invasion.

Every Australian with whom I said more than a few words—my accent gave me away—peppered me with questions about the U.S. election. Though Americans tend to think of England, Germany, and other European nations as our allies, Australians consider themselves America’s closest ally—they are the ally in the Pacific. They’ve fought beside the U.S. in Iraq and Afghanistan—not to mention in Vietnam and the two world wars. They could not understand why our President had attacked their Prime Minister. They were more confused and disappointed than angry—doesn’t America know who our friends are?

After just ten days, I certainly know who mine are.

The post Impressions of Australia appeared first on Austen Marriage.

February 27, 2017

Austen in Australia

I spent the week in Australia, giving presentations on the history and work of Jane Austen. The lectures took me to Sydney, where I spoke at the Annual General Meeting of the Jane Austen Society of Australia, and at a local library; and at the Austen societies in Newcastle and Brisbane.

As in America as well as England, many people here are Austen aficionados, if not fanatics. All manner of readers speak of “their Jane” or “my Jane.” The author’s stories resonate on every continent.

Subjects included the Napoleonic Wars and how they affected Jane Austen’s family and her novels; the general history of the period 1775-1820 and how the major issues of the broader world are subtly weaved into the life of Austen’s country villages; and the battle over slavery, a contentious issue that spanned Austen’s life. Her handling of the topic—or not—in her books is the subject of much debate.

I had given the talks in the U.S. and England, but to more general audiences. I was a little nervous about whether well-studied Janeites would find the information compelling—or old hat. Because I generally cover material outside Austen’s immediate context, though, the topics held their attention and led to good questions afterward.

At the Sydney talk about the war, one person suggested that I add the fact that the income tax was instituted in 1799 to help pay for it. She was probably right, but I was able to say I would cover that point in the broader talk I was doing two days hence. The war cost England the staggering sum of 1.68 billion pounds. Despite this and taxes on goods such as carriages and hair powder, half that amount remained as debt at war’s end.

Australians were interested to hear how Austen weaves naval references into her novels

Australians were interested to hear how Austen weaves naval references into her novelsThe next lecture was at the Ashfield library in a Sydney suburb, located in a mall close by Woolworth’s—completely separate from the U.S. five-and-dime that went out of business decades ago. We were upstairs from the library proper, in a large meeting room where the area council meets to conduct local government business.

Questions here were more about her writing and the writing of other authors of the same period. One person asked what kind of novel I thought Austen would have written had she been a man. This enabled me to say with a smile, “These over here!” Appreciative laughter as I pointed to my trilogy, “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen.” The gentleman was kind enough to buy a copy.

The people in Newcastle were lovely; the town is also lovely—an old steel town that is now being rejuvenated, though a lot of its business remains shipping coal to China and elsewhere. My hosts and the group leader were, well, … lovely. One easily falls into the habit of describing the people and locales as “lovely,” because that’s the one short word that best describes them all.

This venue was more intimate, which either unnerves the speaker or relaxes him. I found myself enjoying the close encounter.

Susannah Fullerton, Austen expert, shows a path in Sydney, built in the early 1800s by convicts sent to Australia from England

Susannah Fullerton, Austen expert, shows a path in Sydney, built in the early 1800s by convicts sent to Australia from EnglandAt the Brisbane talk on slavery, for time and relevance, I did not discuss Mrs. Smith and her financial troubles in the West Indies in “Persuasion.” This reference strongly implies her business is related to the sugar plantations. To me, this is a plot device rather than a comment on slavery. This minor character needs help on a financial matter distant and complicated enough that she cannot resolve it on her own, and the purpose of her predicament is to demonstrate the relative trustworthiness of Mr. Eliot and Capt. Wentworth. The question, though, shows how closely Janeites peruse the works.

My sponsor for this trip was Susannah Fullerton, long-term president of the Jane Austen Society of Australia, a highly respected author of several books on the English writer, speaker on numerous literary topics, and leader of worldwide literary tours.

I have been corresponding with Susannah for three years on many matters related to Austen. She’s a terrific person, very generous with her time and thoughts. Her kindness to me on this trip, and her thoughtful advice on literary projects, were beyond anything I might have expected. Arriving as a distant colleague, I was treated as a close friend.

The post Austen in Australia appeared first on Austen Marriage.

January 25, 2017

Do Austen’s Novels Reveal Her Views on Slavery?

My last blog explored the effort in England to abolish the slave trade—the buying and selling of human flesh—which was accomplished in 1807—as well as the effort to eliminate slavery itself throughout all British possessions, which was not accomplished until 1840.

Slave owners were helped through their “difficult” six-year period of adjustment, 1834-1840, with payments of twenty million pounds as recompense for the loss of their “property.”

Before England ended the slave trade in 1807, the selling price for a healthy adult male was about fifty pounds; women and children were less. Four in ten slaves died—one for every two tons of sugar produced. It was less expensive to buy a new slave than to feed an existing slave. The cycle was self-fulfilling. With new slaves constantly arriving, there was no financial incentive to feed current slaves properly. Without enough to eat, women could not reproduce, requiring more slaves to be brought in.

Slave owners portrayed their “workers” as living happy lives, much better than in their native Africa. The reality was horribly different, with four of ten slaves dying from the grueling work.

Slave owners portrayed their “workers” as living happy lives, much better than in their native Africa. The reality was horribly different, with four of ten slaves dying from the grueling work.Twice during Austen’s life, slaves had the chance to earn freedom. The first was during the Revolutionary War, when American slaves were promised freedom if they fought for England against the rebels. When England lost, many of the freed blacks left with other Loyalists. It is estimated that England had about 15,000 freed blacks, mostly in London, where they took up typical lower-class occupations—and suffered many of the privations typical of the working poor.

A similar offer for freedom came in the French wars. By 1802, England had sent more than 90,000 sailors and soldiers to the West Indies. Half of them died of disease, including Tom Fowle, fiancé of Cassandra, Jane’s sister, who served as a chaplain on his cousin’s military ship. These huge losses caused the British army to buy 13,400 slaves locally to reinforce its troops. As before, the promise to blacks was freedom at the end of their service.

Evangelicals, particularly the Methodists, led the fight against slavery. In contrast, the establishment Church of England not only supported the institution—it also owned a slave plantation, bequeathed to the church in the early 1700s. The profit was used to take the message of Christ to America. That’s right: Anglicans sent the black man to his grave to save the soul of the white.

Before the entire slave trade was abolished in 1807, the abolitionist William Wilberforce (image above, with headline) pushed through a Foreign Slave Trade Bill in 1806. Authorizing the Royal Navy to intercept foreign slave ships, the bill was as much about hurting French interests in the West Indies during the Napoleonic Wars as it was about helping slaves.

In an effort to curry favor with the British after his brief return to power in 1815, Napoleon signed a decree to end France’s slave trade. Though it had the effect of ending the slave trade for all the European powers, the edict did not stop England from taking Napoleon down a second time and exiling him to St. Helena in the far south Atlantic.

Slavery was not the only cause for Wilberforce, the Minister of Parliament who led the fight for twenty years. He supported many other charitable causes, providing relief for the poor and the “deaf and dumb” and founding the first society to prevent cruelty to animals. After giving away tens of thousands of pounds to charitable causes, the abolitionist died in poverty after an investment with one of his sons collapsed.

Mansfield Park undoubtedly concerns slavery, but what does the novel really say about it?

Mansfield Park undoubtedly concerns slavery, but what does the novel really say about it?The battle to end the slave trade came when Austen was reaching the height of her creative powers. Mansfield Park, published in 1814, has slavery as a major theme. The wealth of the Bertram family comes from a West Indies plantation, and Sir Thomas Bertram disappears for the middle part of the novel to tend to business there. The critic Edward Said leads a contingent that criticizes Austen for apparently accepting slavery, while author Paula Byrne leads a group that has Fanny Price speaking “truth to power” about slavery.

As proof of her abolitionist views, Austen supporters cite Fanny’s noted comment that when she raises the issue of the slave trade to her uncle in a room with the entire family, she is met with “dead silence!” The inability of Sir Thomas or his children—her cousins and, theoretically, her betters—to respond to her question about slavery is proof of Fanny’s moral superiority.

However, it’s not at all clear that Fanny’s “dead silence!” comment is a rebuttal of slavery and the family’s reliance on its revenue. The entire passage—not just the one sentence—needs to be carefully read and key phrases studied. I challenge every reader to decide what is really happening with the book’s heroine.

Thoughts?

The post Do Austen’s Novels Reveal Her Views on Slavery? appeared first on Austen Marriage.

December 29, 2016

Fight Against Slavery Carried on Beyond Austen’s Life

Slavery was one of the most contentious issues of Jane Austen’s time. Some scholars claim that she ignored the issue or even accepted the legitimacy of the practice. Others claim that her novel Mansfield Park serves as an anti-slavery tract. For certain, Austen would have tackled the complex issue in a complex way.

The fight to abolish the slave trade—the buying and selling of slaves—had been raging since 1787, when Thomas Clarkson, who had won an essay contest at Cambridge condemning slavery, helped form the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Another founding member was Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery magnate, who created the official emblem of the group, an image of a chained slave (see image with headline) with the plaintive cry “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?”

Soon after, Clarkson gave William Wilberforce a copy of his pamphlet. Shortly after that came the famous meeting under the oak tree on William Pitt’s estate in which Pitt and William Grenville, two future prime ministers, convinced Wilberforce to take up abolition as his main political cause in the House of Commons. In Pitt’s fabled words, “We were too young to realize that certain things are impossible, so we will do them anyway.”

It was Grenville who shepherded the final bill through after Pitt’s death in 1806. Ironically, Pitt had become a (temporary) opponent to abolition because the cause made it harder for him to keep his pro-war political coalition together against France.

The climactic vote to end the slave trade came in March 1807, when Jane Austen was at the peak of her authorial powers. It took another generation before England abolished slavery entirely—six months after the death of Wilberforce in July 1833. Three days before he died, Wilberforce is said to have been assured of the passage of the bill. The end to slavery in all English possessions was phased in over six years, beginning in 1834, and slave owners received twenty million pounds in recompense.

William Wilberforce spent his life seeking to abolish slavery. He succeeded in ending the buying and selling of slaves, but died six months before slavery itself began to be phased out.

William Wilberforce spent his life seeking to abolish slavery. He succeeded in ending the buying and selling of slaves, but died six months before slavery itself began to be phased out.It is not surprising that it took twenty years to end the purchase of human flesh and another twenty-six to end slavery itself. In the early years, the focus was to end the misery of the capture, sale, and transport of slaves, though abolitionists assumed the end to slavery would come eventually. There was the hope that, if slave holders could not buy more, they would treat their current slaves better: It was cheaper to buy a new slave than to feed an old one.

Slavery is perniciously difficult to eliminate once it is in place, for free labor has an addictive effect on the beneficiaries. The slave trade represented 5 percent of the British economy, with a slave ship departing England every day. When everything is tallied—manufactured goods, tools, and rum to Africa; slaves to America; rum, sugar, tobacco and cotton to England—the Triangular Trade represented 80 percent of England’s overseas trade. Liverpool and Bristol were the two largest slave-related ports, which gives us the hint that Mrs. Elton’s family was involved in Emma.

Its tentacles stretched far enough to ensnare the Austen family. Mr. Austen’s half-brother, William Hampson, owned a Jamaica plantation, and Jane’s father was also a trustee of a slave plantation in Antigua for friend, James Nibbs. Nibbs was godfather to Jane’s brother, James. It does not appear that Mr. Austen ever did any work related to the trust.

Aunt Leigh-Perrott was heir to a plantation in Barbados, meaning that any inheritance from that side of the family—which the genteelly poor Austens desired—would have been tainted. The family received none, though, until Aunt Leigh-Perrot’s death in 1836, after slavery itself had been voted out.

What of Jane Austen’s own point of view? We know that her favorite authors opposed slavery, including the poet William Cowper, who penned the famous lines celebrating Lord Mansfield’s freeing of a black slave in England in 1772: “Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs/Receive our air, that moment they are free;/They touch our country, and their shackles fall.”

Jane’s niece Fanny had an anti-slavery story in her diary in 1809; it’s likely her views would have been shaped by Jane, Cassandra, and others of her aunts’ generation. Frank Austen is the only Austen sibling known to have actively denounced slavery; his views likely shaped Jane’s.

In a letter home in 1808, Frank compared the relatively “mild” form of slavery practiced at St. Helena in the eastern Atlantic with the “harshness and despotism” practiced in the West Indies. In St. Helena, a slave owner could not “inflict chastisement” on a “refractory” slave; he must apply to the magistrate for relief. Frank concluded with characteristic honesty: “This is wholesome regulation as far as it goes, but slavery however it may be modified is still slavery. [No] trace of it should be found … in countries dependent on England, or colonized by her subjects.”

In her letters, Austen indirectly praises Thomas Clarkson by saying she was “as much in love” with author Charles Pasley as she ever was with Clarkson—a reference to Clarkson’s book, History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1808).

Mansfield Park has a number of references to slavery, from the title itself—Lord Mansfield having freed the slave Somersett and by extension all slaves in England—to Mrs. Norris, evidently named for a slaver who tormented the abolitionists, particularly Clarkson. Whether the novel itself stands opposed to slavery is a matter of dispute; personally, I believe Austen was too much of an artist to telegraph her own views.

All of these references, however, come after the end to the slave trade in early 1807. Barring the discovery of new family letters, it’s unlikely we’ll know Austen’s true views during the years leading up to 1807. Her beliefs likely evolved along with those of England in general, with little thought early on and a growing realization of the horrors of slavery.

Given her respect for her older brother, Frank’s ardent opposition to slavery likely galvanized her own opposition as she matured.

There’s poetic justice that the Royal Navy, which had earlier protected slaving ships making the Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas, now enforced the ban on slave traffic. Two generations of Austen men, beginning with Frank and Charles and continuing through their self-named sons, intercepted slavers on the open seas.

The post Fight Against Slavery Carried on Beyond Austen’s Life appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 30, 2016

What Did Jane Austen Look Like?

What did Jane Austen look like? No one really knows.

Which is to say: We know fairly precisely her size and shape, but only a little of what her face looks like.

A forensic analysis done by clothing expert Hilary Davidson in 2015 details Austen’s figure. By analyzing an outer garment called a pelisse, known to have been Austen’s, and constructing a new one of the same dimensions, Davidson concludes that Austen was between 5 feet, 6 inches and 5 feet, 8 inches tall and she had a bust of 31 to 33 inches, a waist of 24 inches, and hips of 33 to 34 inches.

This made her tall for the age and typically spare. One observer, not necessarily friendly, used the metaphor of a fireplace poker to describe her, though it’s not clear whether that reference was to her ramrod shape or to the underlying iron of her personality.

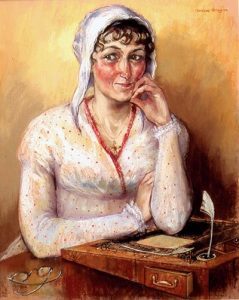

Conventional image of Austen, which did not favor her and was later altered to make her appearance softer

Conventional image of Austen, which did not favor her and was later altered to make her appearance softerAusten’s face in theory is one of the best known in the world, based on a somewhat cherubic image that has launched a thousand books—and will soon be imprinted on England’s ten-pound note. The image is based on a watercolor done by her sister Cassandra in about 1810. However, people who knew Austen said the image was not very flattering, and the version normally used in print (see image) was further altered by an illustrator to soften her features.

The only other drawing known to be of Austen, also a watercolor by her sister Cassandra, is a lovely wash of blue in which Jane’s face is obscured by the angle and a large bonnet and her figure is obscured by her blooming dress (see image with the headline at the top).

Silhouette of Austen?

Silhouette of Austen?There is also a silhouette, found in a family copy of Mansfield Park, believed to be of Jane (see image).

Two other images have emerged in the last few years. The most curious—and interesting image—comes from an Austen scholar, Paula Byrne, who wrote a lovely book called The Real Jane Austen: A Life in Small Things. Byrne’s husband bought a drawing at auction that he thought resembled Jane.

On the back they discovered the name “Miss Jane Austin”—the name being misspelled. At first they thought the portrait might be a later rendering of her; but many things pointed to it being

of Austen herself—in particular, the strong resemblance of the face to her brothers, particularly Charles (see images below).

Byrne, who eventually did a BBC special on the pencil-on-vellum drawing, calls the usual portrait “saccharine.”

Byrne’s portrait of Austen shares the nose and striking eyes of the family, particularly of her brother Charles

Byrne’s portrait of Austen shares the nose and striking eyes of the family, particularly of her brother Charles Charles Austen was a naval officer who had the family’s piercing gaze

Charles Austen was a naval officer who had the family’s piercing gazeTwo of three Austen experts have supported the idea that the newly found portrait was of Austen.

Perhaps because the image is not as mild and sweet as the accepted image, only a few others have rallied around the likeness as a likely portrayal of Austen. In particular, Austen expert Deirdre le Faye rejects the portrait, but then le Faye has not always been enthusiastic about any ideas involving Austen or her family that did not originate with her.

Studies indicate that the picture is likely from 1815, when Austen was riding high as an author, though her identity remained largely unknown. It’s tempting to think that Jane may have had her portrait done after she saw some success. It’s likely to have been done in London, where she spent quite a bit of time as her books were in production. This is also when she cared for her brother Henry during a serious illness. An ornate church peeks through the window. Le Faye dismisses the building as being Canterbury. It’s more likely to be Westminster Abbey, with its symbolism as the resting place for literary greats.

Personally, I find the piercing intelligence—exactly the same as the gaze of her brothers Frank and Charles—to be more convincing than the soft, plump rendering of the conventional portrait.

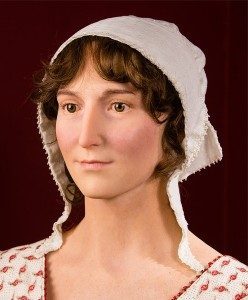

Even more recently, forensic painter Melissa Dring was commissioned by the Jane Austen Centre in Bath to create a new portrait of Austen, working as if she had been commissioned by police to develop a sketch of someone. Dring took descriptions of Austen, incorporated the general family features—particularly the eyes and nose—and painted her as a woman in her late twenties, which she would have been during her years in Bath.

Dring’s forensic portrait captures Austen’s liveliness

Dring’s forensic portrait captures Austen’s livelinessThe best description of Jane’s face comes from her niece Caroline, who said it “was rather round than long—she had a bright, but not pink colour—a clear brown complexion and very good hazle eyes. She was not … an absolute beauty, but … a very pretty girl. … Her hair, a darkish brown, curled naturally.” Another person described Jane as having rosy cheeks.

Dring’s result is a striking portrait of a bright, humorous woman—though in my view the painter slathers on the red rather too thick. Instead of having rosy cheeks, Austen seems to suffer from rosacea. Interestingly enough, though, the result far more resembles the Byrne portrait than the conventional portrait (see image).

Dring explains her research and methodology here.

Unless someone finds an indisputable portrait of Austen, we’re left ultimately to speculation. However, the most believable rendering I’ve seen is a wax figure, also commissioned by the Jane Austen Centre, based on the Dring portrait and done by the renown sculptor Mark Richards (see final image).

Perhaps because this rendering is three dimensional, it seems to best capture the stature, grace, and personality of a person whose intelligence and humanity radiate outward.

This is a woman who could charm her nieces and nephews, captivate men, be every woman’s best friend–and write insightful novels about human beings and their day-to-day lives.

The post What Did Jane Austen Look Like? appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 17, 2016

Strolling in the Pleasure Gardens of Jane Austen’s Bath

Whereas the first day of the Jane Austen Festival in Bath was as dreary as anyone could wish to avoid—enlivened only by the gaily dressed ladies and gentlemen who braved the rain for the Promenade—the next day broke off as sunny and pleasant as anyone in England would wish to enjoy.

The major activity for our group was a tour of the pleasure gardens, beginning at the Holburne Museum, which now as then is the entrance to Sydney Gardens. In Austen’s day the building was called the Sydney Hotel, though it was not a hotel in the traditional sense but a place of entertainment. All of the activities of the Gardens—public breakfasts, music, fireworks, and special events—began at this building. The Gardens were behind.

The public could buy subscriptions for a season of activities, though occasionally special events required additional admission. Jane Austen is known to have participated in some public breakfasts.

Moira throws herself energetically into her history of Sydney Gardens

Moira throws herself energetically into her history of Sydney Gardens

Our tour was led by an architectural historian by the name of Moira, a knowledgeable, energetic, theatrical, R-trilling woman of a certain age and build. She walked us through—literally—the layout of the Gardens, which as originally constructed had a variety of features including a canal, Chinese-style bridges, a waterfall, serpentine promenades, a grotto, and a labyrinth.

Progress has reduced the size of the Gardens and eliminated a few features. The Great Western Railway swallowed the labyrinth in the 1830s, for instance. Most of the Gardens remain, however, and it’s still a lovely place to promenade of a pleasant afternoon, as Jane and her sister Cassandra were fond of doing.

The only way for a lovely woman to dress for an afternoon promenade

The only way for a lovely woman to dress for an afternoon promenade

On our Sunday, the Gardens were full of visitors, including a few dressed in Regency wear. (Being in costume can lead to discounts at some haberdashers and eateries, we learned.) Our group featured a stunning young woman in a blue Regency walking outfit carrying complementary ivory parasol and gloves. It’s this sort of thing that gives credence to the concept of time machines.

The one thing that surprised me was the extent to which the Gardens sloped up from the entrance. Given that the canal cuts across the Gardens along the back, I had assumed that the elevation would be relatively flat or would slope downhill rather than up.

We finished at Jane Austen’s three-story house at 4 Sydney Place across the street from the Gardens. The building is rather austere, with a plain front of light-colored local Bath stone. Next to the red door is a small plaque giving the dates of Jane’s tenure there.

The family lived at Sydney Place from 1801 to 1804, after her father retired and they moved from the country in Steventon, about eighty miles east, to Bath where her parents had met and married as young people.

The location of their house, just off the Great Pulteney Bridge and across from the Gardens, was, however, too expensive for a retired clergyman and they ultimately moved to cheaper quarters. The plaque incorrectly gives the end date as 1805. Likely, the person who commissioned the sign assumed that the family moved upon the death of her father in January 1805; in fact, it was before then.

In her first few years in Bath, Jane Austen lived in a townhome at 4 Sydney Place, across from the Gardens

In her first few years in Bath, Jane Austen lived in a townhome at 4 Sydney Place, across from the Gardens

We couldn’t go into the house because it’s now part of a boutique hotel group—so any Janeite can settle in for a long weekend. The price is somewhat dear! A member of our group who recently stayed there says it is well decorated and has a number of Austen-related books but, curiously, none of Austen’s own novels.

Moira the tour guide had a book of illustrations that she used to point out details of the Gardens to the tour group. I noticed that one illustration showed a hot-air balloon, which she had not mentioned by the time the tour concluded.

I discreetly asked whether that drawing might be of the flight from the Gardens in September 1802. She laughed with surprise and excitement. The illustration was from a much later flight in Vauxhall Gardens, London—there is no artwork apparently of the 1802 flight by Monsieur André-Jacques Garnerin in Bath. The story is that the balloon was intended to remain tethered, being moved about by ropes above the heads of the admiring crowd. But the balloon got away, causing great mischief and alarm.

Moira wondered how an ordinary modern-day American might know about Bath’s aviation history. Before I could answer, my companions leapt in to explain that I had written a novel about Jane Austen, the critical scene coming when she is launched in a runaway balloon from Sydney Gardens. Furthermore, they announced, after hearing all the details about the Sydney Gardens, the Sydney Place home, and the balloon flight—I had got all the details right.

(Actually, there’s one detail I might have fudged, but I will wait for a diligent reader to point it out.)

The post Strolling in the Pleasure Gardens of Jane Austen’s Bath appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 13, 2016

Rain in Bath Fails to Dampen Spirits During Promenade

Being in Bath for the annual Jane Austen Festival was a special treat, and things were so busy that the first time I’ve had to write is two days later, in another Austen haunt about 90 miles east of Bath–Hampshire.

Even these thoughts are quickly put together. No coherent theme has emerged!

The Jane Austen Festival runs for ten days in Bath every September, two weekends sandwiching a week in which something interesting happens each day: lectures, balls, tours, theatrical performances.

My wife, Wendy, and I attended the Friday night pre-festival soiree, which was a relatively small affair in which we got to mingle with the many volunteers who help put on the event. Things are informal enough, and hands’ on enough, that Jackie Herring, the festival director, was the one taking tickets.

Jackie has been with the festival almost since its start and director for nine years. She says it’s a good thing it’s an annual event, because it takes about a year to put together.

It was interesting to see the number of young women involved as stewards, who have various assignments all during the festival, including shepherding participants to the right places for the Promenade and different events. One such young lady was a microbiologist in Bristol, and another held multiple teaching jobs. Both were eager to help all week at the Festival. It’s good to think that another generation has fallen in love with Austen.

Saturday’s big event was the Promenade, at which a few years ago Bath set a world record in the number of people wearing Regency dress. This is the modern record, of course. One supposes Bath had a few more Regency-clad denizens in 1802. Bath reclaimed the modern record from upstart Americans who had previously gathered the largest modern Regency crowd, thinking it would be fun to beat the Brits at their own game.

We were a group of six: Wendy and I, the two winners of the sweepstakes tied to the launch of the second volume of my trilogy, “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen,” and their guests. As we stood for a few photos in and around the Abbey, we were swarmed by a host of the other tourists, who could not get enough photos of relatively attractive people dressed so smartly. We had to explain to most of them that there was this festival going on, and that hundreds of people would soon be walking all over the city in Regency costumes.

The weather was gloomy all morning, with a light shower here and there. The forecast was for the rain to clear at 11:00 with the start of the Promenade, which began at the Assembly Rooms (the Upper Rooms in Jane’s day) and meandered by or through all of the big sights (and sites) in Bath.

Naturally, a forecast of clearing skies at 11:00 meant that this was when the rain began in earnest, and it came down in buckets for part of the two-hour walk. By the end, we were all as bedraggled—but in equally determined spirits—as Liz Bennet when she traipsed through the mud to see her ill sister.

Beyond my finely accoutered companions, the highlights of the Promenade for me were a delightful girl out with her grandparents, a set of half a dozen middle-aged Janeites from a Germanic country (whose language I could not understand), and a group of young people and children performing dances in the rain for those of us now able to finish inside the building where we started.

Inside the Rooms were hot drinks and pastries, which the crowd quickly set upon before turning to see all the wares at the Festival Fayre. This emporium features all manner of items related to the Regency era, from subscriptions to the magazine “Jane Austen’s Regency World” to Austen books and memorabilia to every variety of period clothing and accessories. If you’ve been to the shops at the annual general meeting of the Jane Austen Society of North America, the fayre is similar—but the clothing for sale comes in a greater variety of quality and expense.

The day formally concluded for me with a lecture on the bigger history of the Regency period that framed Jane Austen’s novels. A small but attentive audience listened as I spoke about science, business, social and labor issues, politics, and war.

After answering several interesting questions, I was pleased when a man in the audience thanked me for the talk and said—apparently quite surprised—“You made an hour go by fast!”

The post Rain in Bath Fails to Dampen Spirits During Promenade appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 8, 2016

Austen Authors

Austen and the Big Bow-Wow

Austen and the Big Bow-WowJane Austen told both her nephew and the Prince Regent’s librarian that she lacked the knowledge and ability to write about the big world. She worked in miniatures, she said, “two inches wide, on which I … produce little effect after much labor.”

Indirectly seconding her, Sir Walter Scott wrote: “That young lady has a talent for describing … ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The big bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going; but [I lack her] exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting.” Read full post…

The post Austen Authors appeared first on Austen Marriage.

Just Jane

“The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen: Volume 1″/ By Collins Hemingway/ A Review & Giveaway

“The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen: Volume 1″/ By Collins Hemingway/ A Review & GiveawayThe Marriage of Miss Jane Austen reimagines the life of England’s most famous female author by asking: How would her life have changed if she had married and had a child? How would this thinking woman, and sensitive soul, have responded not to a ballroom flirtation but to a real relationship that developed over time? How would shouldering the responsibilities of marriage and motherhood have changed her as a person and a writer? Read full post…

The post Just Jane appeared first on Austen Marriage.