Collins Hemingway's Blog, page 2

February 21, 2020

Jane Eyre: The Other Woman

Charlotte Brontë featured a Jane Austen-style heroine in her novel Jane Eyre. Despite her inferior social and financial position, Jane would not back down against Mr. Rochester any more than Elizabeth Bennet would back down against Mr. Darcy. Jane Eyre’s difficult situation as a governess is exactly what Austen’s Jane Fairfax sought to avoid—and finally did—in Emma.

Jane Eyre provides striking psychological insight into a woman’s mind. It also has the strange and forbidding mood and just-in-time plot twists of the Gothic thrillers and sentimental novels that Austen parodied in her early novel, Northanger Abbey. Most readers forgive Brontë’s melodrama for the intimate portrait it gives of this plucky young woman.

Most readers also forget the other woman. Or actually, the wife. It is Jane, it turns out, who is the other woman.

Jean Rhys, however, remembered. In the novel Wide Sargasso Sea, she tells the story of Jane Eyre from the point of view of the madwoman in the attic. This is the woman Jane initially fears is a ghost and who, until the fatal fire, prevents Jane from marrying Mr. Rochester. Herself a Creole from Domenica, Rhys had wanted to tell this story for years.

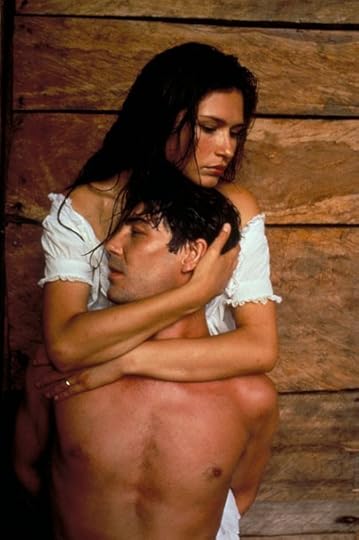

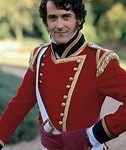

Wide Sargasso Sea was published in 1966, almost 120 years after Brontë’s novel, and has been made into a film several times. The movies focus on the steamy sensuality of the Caribbean. (Images above and in the text are from the 1992 movie by John Duigan.)

The book, however, is more into the overall life of heroine and her bare existence. The novel marked a reemergence of Rhys, who was originally part of the 1920s Paris crowd that included Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ford Maddox Ford, and others. Her earlier novels were about the Paris nightlife—and wild life.

Wide Sargasso Sea features a terrific first half, which tells the story of Antoinette Cosway’s early life in the West Indies. This is when the small white or Creole landowners in the West Indies lost their free labor. Such families would not have been the wealthy absentee owners but middle-class farmers who suddenly had no way to make a living.

It’s implied but never stated that her family is Creole. It’s several times described as white, but this may mean only whiter than the black neighbors. At one point a black girl tells the heroine that she’s a “white” (n-word) and “everybody know” that the “black” (n-word) is better than the white.

Mixed-race offspring were often freed and were allowed to set up their own shops and farms. They were allowed to possess their own slaves, who gained their freedom along with all the others in the 1830s. Now the small farmers, rather than their enslaved workers, are close to starvation. Away from the towns, they lack protection from their former “possessions.”

The story of life in the Indies is harrowing, but the novel becomes predictable in checking (“ticking” to my British friends) the boxes as to the evils of colonialism, sexism, and patriarchy as we get caught up in the Rochester story. Still, the descent of a strong, intelligent woman into insanity is terrifying. Readers will like Rochester a lot less after reading this novel than after Jane Eyre.

Sargasso is stylistically tight like Rhys’s 1930s novels and stories. One problem is that it switches the narrator from the female lead, Antoinette Cosway, in the first section to Rochester in the second section and back to Antoinette in the third section. Rochester is not nearly as interesting as she is, so the book sags when it should surge.

Movies of “Wide Sargasso Sea” emphasize the steamy sex, as shown in the Romance-cover-like image from the 1992 movie. Karina Lombard is Antoinette, and Nathaniel Parker is Rochester.

Movies of “Wide Sargasso Sea” emphasize the steamy sex, as shown in the Romance-cover-like image from the 1992 movie. Karina Lombard is Antoinette, and Nathaniel Parker is Rochester.However, Wide Sargasso Sea became Rhys’s most popular book and brought back her earlier novels, which are riveting explorations of Parisian life after World War I. Rhys is too important a writer for these other books to be lost.

Rhys lived in obscurity during the thirty-year gap between her early novels and Sargasso. She and her husband were desperately poor. He was involved in a financial crime and went to jail. Then his health failed. The situation drove her to desperation and depression. She described the passage of many years as being “two days drunk, one day hung over.” Her books went out of print and no one could find her to get permission to republish them. Finally, someone tracked her down in a remote English village. She died in 1979.

The person who collected her works, Diana Athill, said Rhys most identified with her heroine in Sargasso because she knew what it was like to be driven to the brink of madness. Most of her stories were biographical, including the one about a young woman’s ménage a trois.

I came upon her early novels in 1986 (I looked up my list of annual reads!) because I’d found a passing mention to a writer named Jean Rhys who might have been a model for Ernest Hemingway’s tight prose. I’d never heard of her, and I was studying Hemingway at the time. Her early stories and novels have a similar feel to his. However, they were writing more or less contemporaneously in Paris, among the same literary set. I’ve seen no references that they knew each other personally, but Hemingway knew and detested (as a writer) Ford Maddox Ford, who was her patron and lover.

Hemingway’s first novel was published in 1926, hers not until 1928. It’s not clear who might have influenced whom. But it is a strange parallel, indeed, between the most macho writer of the early 20th century and a woman who wrote no-holds-barred novels about the lives of women. Rhys’s early books are about those days in Paris, too, from a woman’s underdog point of view rather than Ernie’s two-fisted-drinking man’s point of view (though drink features prominently in hers too).

A collected set, The Complete Novels of Jean Rhys, is worth exploring for anyone interested in a unique voice telling unique stories about women. Not just Antoinette’s life but the lives of women of our era.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Jane Eyre: The Other Woman appeared first on Austen Marriage.

January 22, 2020

Coincidences Kick Off P&P; Chararacter Carries It

In a recent blog, I wrote about coincidences in Jane Austen’s work. I’m following up again today with a few more examples of how she used them and how this use affected her work.

Coincidences were a common contrivance to solve plot problems before and during Austen’s life. (And remain so in too many poor novels today.) Her novels had a few coincidences, but nothing like other books. Almost always, the important matters in Austen’s fiction result from actions of the characters themselves, not outside interventions. Her coincidences tend to clean up minor matters. As I mentioned previously, clerical livings come up twice at just the right time to settle the main couple’s finances in Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park.

The living in Mansfield Park is a major springboard for the plot, coming up at the start of the novel with the death of Mr. Norris and again at the end to provide for Edmund Ferrars and his new wife Fanny. In between, the incoming clerical family turns out to be related to Henry and Mary Crawford. These are the two players who bring great fun and ultimate agony to the young people in the Bertram clan. The Crawfords, in turn, were raised by an admiral who provides Fanny’s brother with a critical promotion—part of Henry’s unsuccessful attempts to win the heart of the heroine, Fanny Price. There would be no action without this opening set of coincidences.

Emma is more typical. This novel has two minor coincidences involving Harriet Smith, the heroine’s protégé. The first one sets her in the potentially romantic path of another major character, Frank Churchill, after she has been beset by “gipsies.” The second gets her safely married to the young farmer, Robert Martin, when Emma is worried about Harriet’s interest in George Knightley. These happenstances don’t materially alter or drive the main plot. They just save Austen a clarifying scene here or there.

Most of Austen’s coincidences involve what I call the “gathering of the cast”—getting all the players in one place at the beginning. Usually, she brings everyone together quickly, trading off a coincidence or two for the ability to set a lively—and realistic—story into motion quickly. Pride and Prejudice provides a great example, when the major outsiders all come to Meryton within ten weeks of each other.

We can see the unhappy results when Austen doesn’t get things going snappily. It takes her five chapters and nearly fifty pages to gather the cast in Mansfield Park, and another twenty pages before Fanny Price begins to act in present time. These delays are a major reason that the novel has such a sluggish feel in comparison to Austen’s other works.

If we discount the coincidences related to the “gathering of the cast” in P&P, the only major plot contrivance involves the Gardiner family. Mrs. Gardiner, a relative, is used to reconnect Elizabeth and Darcy after the big fight that occurred during Darcy’s failed first proposal. Mrs. Gardiner ends up taking Elizabeth to Darcy’s home, the Pemberley estate, and later tells Elizabeth about Darcy’s assistance to the Bennet family in London.

The Gardiners serve a double role in Pride and Prejudice: They connect Elizabeth to Darcy in key moments, and they show Darcy that not all of the Bennet clan are lightweight social climbers.

The Gardiners serve a double role in Pride and Prejudice: They connect Elizabeth to Darcy in key moments, and they show Darcy that not all of the Bennet clan are lightweight social climbers.Something of a minor deus ex machina (“god from the machine,” the general term for a plot contrivance), Mrs. Gardiner is Austen’s way of moving the chess pieces down the board. Her improbability has to do with her location—she grew up in the same county as Darcy—and the convenient change in plans that leaves Pemberley as the only target for Elizabeth’s visit. Austen’s use of Mrs. Gardiner is not perfect, though she plants Mrs. Gardiner’s roots in Devonshire early; has her invite Elizabeth to travel early; and has a rational explanation for the change in plans. (Mr. Gardiner’s business schedule no longer allows the original plan of travel to the Lakes region.)

The Gardiners, of course, have another important role beyond moving the plot forward. They are both sensible, intelligent people who raise Darcy’s awareness that not all of Elizabeth’s family are social climbers or out-of-control teenagers. One critic has said that the Gardiners are the only truly noble family members surrounding Elizabeth. The mechanics of the Gardiner subplot are a little clumsy, but almost any plot device would be. There’s no snap-the-fingers solution by which Austen can get Elizabeth to Pemberley to ascertain Darcy’s true worth.

A character with this double role of character-plus-plot-device occurs in a lot of novels, especially Austen’s. Mrs. Allen brings Catherine Morland into society in Northanger Abbey, setting the main plot in motion. Her lack of oversight of Catherine also leaves her young charge subject to the aggressive courting of John Thorpe. In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Jennings links the Dashwood sisters with people in London and other places and she relays back critical information to them. Pop social observer Malcolm Gladwell has a term for such people—a “connector.” We can accept one “connector” in any novel, as long as the connector is drawn as a real person.

I’d be more concerned if the coincidences drove the stories in Austen more than they do, once things are under way. There is a reason that Austen’s plots seem relatively so undramatic while also very real. It’s that, once the characters begin to act, they behave like human beings we all have met and known in our lives. It is no coincidence that resolution of the major story lines comes through character, not contrivance.

(Images from the 1995 BBC miniseries of Pride and Prejudice.)

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Coincidences Kick Off P&P; Chararacter Carries It appeared first on Austen Marriage.

December 25, 2019

Christmas Presents for Austen Lovers

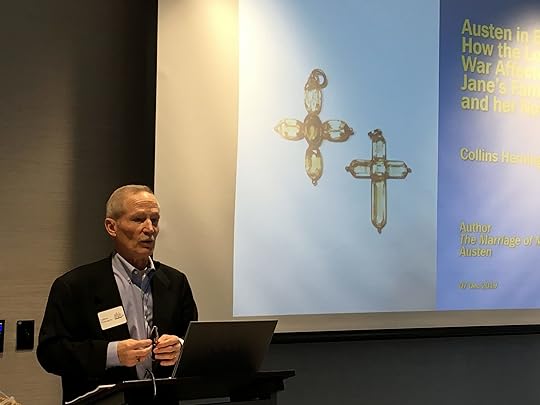

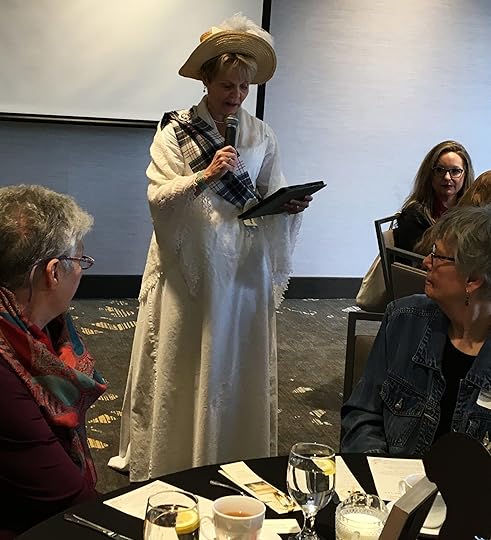

December is a joyous month for Janeites. The month includes Jane Austen’s birthday on Dec. 16 and of course Christmas on Dec. 25. Many Austen groups have December celebrations that partake of the holiday spirit. I was fortunate to speak at a December tea in Boise and a dinner in Salt Lake City.

It was my first chance to spend any time in either Western town. My wife and I had the opportunity to wander around both city centers, which were dressed in their best holiday finery. Snow in the mountains around both provided a nice touch, and Christmas trees provided organic ornaments on the hills. The Regency clothing sported by many members made both visits seem like an Austen Christmas card. Donna Fletcher Crow and her naval escort in Boise, above by headline, make the point.

My Boise talk was about the Austen family’s military service and how it affected Jane’s work. A topaz cross, a present from a naval brother, became a similar gift from a naval brother in “Mansfield Park.”

My Boise talk was about the Austen family’s military service and how it affected Jane’s work. A topaz cross, a present from a naval brother, became a similar gift from a naval brother in “Mansfield Park.”Christmas also brought a bounty of Austen gifts. One of them is in front of me as I finish this blog on Dec. 23. This is the date in 1815 when Emma was published. Of the other presents, here are just a few:

Janine Barchas’s new work, The Lost Books of Jane Austen, continues to garner rave reviews. The latest is from respected critic John Mullan, writing in The Guardian. Mullan calls Barchas’s book “a deliciously original study of the cheap editions of Pride and Prejudice and other novels” that casts new light on Austen’s readership. His conclusion: “The lesson of this delicious book is that she was even more popular for even longer with an even greater variety of readers than we ever thought.”

Barchas’s lushly illustrated history shows that it was the many cheap editions that spread Austen’s work, and her fame, throughout the English-reading world. By tracking this “pulp fiction,” produced by decades-old, heavily worn printing plates, The Lost Books of Jane Austen demonstrates that the inexpensive versions of Austen’s books did more to cement her reputation with the general public than all the fancy ones ever could. The book is funny in the right places, academic in the right places, and thoughtful and respectful where the “gritty” lives of the book owners required it to be.

Tamara MacKenthun, the suitably attired regional coordinator for Southern Idaho, opens the JASNA tea.

Tamara MacKenthun, the suitably attired regional coordinator for Southern Idaho, opens the JASNA tea.It’s a little late and a little big for a stocking stuffer, but it’s a find—just like the books it describes.

Barchas and another scholar, Devoney Looser, provide another treat. They have edited a special issue produced by the Texas Studies in Literature and Language and Project Muse that will be available free online for the next month. A collection of articles by a range of Austen experts, the issue is titled “What’s Next for Jane Austen?”

Separately, Looser published an article in the Times Literary Supplement about the very first Austen fan fiction, written by an Austen near-contemporary. It’s a hoot.

Another timely article is this one in the New Yorker, “You’ve Probably Never Heard of America’s Most Popular Playwright.” It’s about Lauren Gunderson, writer of the Austen-themed Christmas play Miss Bennet: Christmas at Pemberley. In addition to this seasonal favorite, Gunderson has more plays in production than any other playwright in America. …

Finally, Austen’s birthday brings us its annual bag of goodies from the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA). This is the collection of essays in Persuasions On-Line, which this year covers Northanger Abbey. The collection includes my essay, “The Bridge to Austen’s Mature Works—and More,” which reverse-engineers the novel to determine how it was constructed. My work leads to surprising conclusions about the book that has the double distinction of being both Austen’s first and last completed novel.

Merry Christmas to all!

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Christmas Presents for Austen Lovers appeared first on Austen Marriage.

November 27, 2019

Giving Thanks with Austen

With my regularly scheduled blog appearing this year on Thanksgiving, I wondered whether there was any formal giving of thanks in Jane Austen’s work. The November U.S. holiday has spread to most of the Americas. The English have a more general harvest-related tradition of providing bread and other food to the poor, often through the church. That tradition was extant in the Regency and continues now.

Though today’s American celebration is secular in nature, the practice has spiritual roots. It was religious settlers in Massachusetts and Virginia who began the celebration. Most Americans know the tradition of the Pilgrims inviting the native tribes to join in. It was the Indians who provided the food that enabled most of the early colonies to survive the first desperate years.

President George Washington created the first official Thanksgiving in 1789 “as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many and signal favours of Almighty God.” President Abraham Lincoln made it an annual event beginning in 1863, when, in the middle of the Civil War, he proclaimed a national day of “Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

Austen’s family was religious, of course. Her father and two brothers were clergymen. Her works contain strong, though not didactic, moral strains. I wondered: Did any of her characters ever directly express thanks—to God, to Providence, to the universe? Did anyone express gratitude in a way that recognized any higher power?

I could not find any direct use of “giving” or “offering” thanks in any of Austen’s six novels. Most of her novels contain fifty or sixty ordinary thanks each. Persuasion is the least thankful with only eighteen, but it includes the most fervent. Most of the thanks are a polite reflex to ordinary behavior or a specific response to a good deed performed by another.

“Thank God!” occurs once or twice per book. The sense is usually general. Sometimes the phrase is a positive and sometimes a negative. In Persuasion, Mrs. Croft thanks God that as a naval wife she is blessed with excellent health and was seldom seasick on the ocean. Perversely, William Elliot writes “Thank God!” that he can stop using the name “Walter”—the name of Anne’s father—as a middle name. Anne Elliot stiffens upon learning the insult to her family.

“Thank God!” is a remark that is canceled out in Northanger Abbey. Catherine Morland’s brother James writes her to say “Thank God!” that he is done with Isabella Thorpe, who is now pursuing Captain Tilney. The next post brings a letter from Isabella, telling Catherine “Thank God” that she’s leaving the “vile” city of Bath. By now dumped by the Captain, she doesn’t know that Catherine knows what’s up. Isabella pleads “some misunderstanding” with James and asks Catherine to help: “Your kind offices will set all right: he is the only man I ever did or could love, and I trust you will convince him of it.” Catherine doesn’t.

The only real “Thank God!”, as an appeal to the Deity, comes in Persuasion after Captain Wentworth’s inattention contributes to Louisa’s fall and concussion: “The tone, the look, with which ‘Thank God!’ was uttered by Captain Wentworth, Anne was sure could never be forgotten by her; nor the sight of him afterwards, as he sat near a table, leaning over it with folded arms and face concealed, as if overpowered by the various feelings of his soul, and trying by prayer and reflection to calm them.”

Admiral Croft and Anne Elliot are thankful that Captain Wentworth is coming to Bath–unengaged.

Admiral Croft and Anne Elliot are thankful that Captain Wentworth is coming to Bath–unengaged.Everyone’s prayers are answered. Louisa mends and becomes engaged to Captain Benwick. Wentworth is free to marry Anne.

A deeply thankful attitude does exist with two of Austen’s characters. Readers who pause to think can probably guess the two. Beyond the village poor in the background, which characters are most in distress and most likely to be thankful for any relief?

We might consider Mrs. Smith from Persuasion, who had the “two strong claims” on Anne “of past kindness and present suffering.” Her physical and financial straits are dire, yet “neither sickness nor sorrow seemed to have closed her heart or ruined her spirits.” Mrs. Smith, however, is more shrewd than thankful, using Anne’s marriage to help end her own suffering.

What character, living on the margins, has a level of energy that often sets into motion her active tongue? We find her in Emma:

“Full of thanks, and full of news, Miss Bates knew not which to give quickest.”

When Mr. Knightley sends her a sack of apples and the Woodhouse family sends her a full hindquarter of tender Hartfield pork, Miss Bates responds with the sunniest appreciation: “Oh! my dear sir, as my mother says, our friends are only too good to us. If ever there were people who, without having great wealth themselves, had every thing they could wish for, I am sure it is us.” She might be auditioning for Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

In contrast, the social-climbing new vicar’s wife, Mrs. Elton, feels thankful in a prerogative way. “I always say a woman cannot have too many resources—and I feel very thankful that I have so many myself as to be quite independent of society.”

If anyone has the right to feel a lack of thanks in life, it is Fanny Price of Mansfield Park. When she is not being forgotten, it is to provide some service for someone else. When she is not being ignored, it is to be abused by her aunt, Mrs. Norris. Just about every word that can convey melancholy, sadness, or anguish serves to repeatedly describe her.

She feels misery at least eight times; some variety of pain at least ten times; wretchedness half a dozen times. She is oppressed three times and suffers stupefaction once. The best she normally manages is to feel both pain and pleasure, four times. Her circumstances and personality leave her in a “creep mouse” state of mind. She trembles a dozen times; she cries a dozen times and sobs at least four other. The stress is so great that she comes close to fainting at least three times and is ready to sink once; she suffers fright or is frightened six times; she reacts with horror or to something horrible five times.

Yet for all her unhappiness, she manages to look on the sunny side of life.

Fanny feels gratitude at least fifteen times, for things small and large. Especially toward her cousin Edmund, played by Johnny Lee Miller in the photo by the headline. Gratitude for Edmund tending to her when she first comes to live with her wealthy relatives. For his providing her a horse to ride. For her uncle once letting her use the carriage to go to dinner. Even gratitude once “to be spared from aunt Norris’s interminable reproaches.” Kindness comes up more than 125 times in the book. The most common use again relates to Edmund: his kindness to her throughout, and his encouragement of others to be kind to her. Fanny can even feel grateful toward Henry Crawford, despite his character flaws, for his kindness to her brother and, a couple of times, for his kindness to her.

It seems to be a fundamental aspect of human nature that those with the least to appreciate in life treasure what they have the most. Austen’s treatment of Miss Bates and Fanny does not, I think, reflect a conscious attempt at moral teaching. Their attitudes flow directly from the women’s character. Fanny and Miss Bates are gentle souls with big hearts. They give thanks naturally for the joy of existence.

So should we all.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Giving Thanks with Austen appeared first on Austen Marriage.

October 30, 2019

Commemorating 40 Years, and 400

Today’s blog provides a capsule of the recent Annual General Meeting of the Jane Austen Society of North America, in Williamsburg, VA. The week involved history, pageantry, and good manners—and that was outside the conference halls. It was the 40th anniversary of the founding of JASNA, and the 400th commemoration of major events in Virginia’s history.

My wife and I enjoyed Williamsburg, a town that keeps its eighteenth-century history front and center. This was our first visit, and I thought perhaps we’d see a history museum here and an old house or forge there. Instead, the entire town is a living museum (and proud of it). It boasts more than forty historic sites and two art museums.

The governor’s palace (house) included a full panoply of weapons intended to impress colonists with the power of the British crown. The colonists rebelled anyway, and the last governor spent much of his time on the James River, avoiding capture.

The governor’s palace (house) included a full panoply of weapons intended to impress colonists with the power of the British crown. The colonists rebelled anyway, and the last governor spent much of his time on the James River, avoiding capture.Historic Williamsburg comprises almost all the town center, perhaps a mile on each side. Modern services and shops are confined to one area on the west side of the town. You can walk or ride a bus to all sites. We did a mix of both. We started early because of the forecast for hot weather. Hot it was. The official temperature was in the high 90s but the effective temperature was 100 degrees. (Wind-chill factor makes temperatures feel colder. In the South, the humidity makes temperatures feel warmer.) We benefited from a bright, knowledgeable tour guide at the governor’s palace (house) and learned about early crafts from several artisans doing their craft work in the shops. Though it was mid-week in October, there were plenty of visitors to keep tradespeople busy answering questions.

Williamsburg was more meaningful to us, I think, because we saw Jamestown the day before. Jamestown, the site of the first successful English colony in North America, is both an historical and an archeological site. Excavations have uncovered the foundations of early buildings and the fort.

This church, from the early 1900s, is built on the foundation of the original statehouse from hundreds of years earlier in Jamestown.

This church, from the early 1900s, is built on the foundation of the original statehouse from hundreds of years earlier in Jamestown.This year, 2019, makes for two important anniversaries. One is the 400th anniversary of the founding of the town’s governing council, which was the first democratic institution set up by British settlers. By the time of the American Revolution, colonists had more than 150 years of experience in self-government. The second anniversary was the 400th anniversary of most anti-democratic institution imaginable, slavery. The institution came by accident, when a British privateer captured a Portuguese ship carrying “20 and odd” enslaved Africans. The British ship traded the lives of these people for “victualls” at Jamestown.

Jamestown’s museum is well done, providing a thorough history of the creation of the colony and its difficult early years. It honors the sacrifice and hardships of the British settlers while also explaining the history of the native peoples and the fate of the enslaved people.

Weavers and other craftspeople not only practice their wares, they explain to visitors how they do their trades in Williamsburg.

Weavers and other craftspeople not only practice their wares, they explain to visitors how they do their trades in Williamsburg.Now, on to the AGM itself. Jocelyn Harris gave the opening plenary talk. As usual with Jocelyn, it was well-researched and well-presented. Her point was to defend the intelligence of Catherine Morland, the heroine of Northanger Abbey. I agreed with all her points, but it took me a few moments to get in synch with her commentary because it never occurred to me to doubt Catherine’s intelligence.

Naïve, yes. Gullible, yes. Prone to harmless fantasizing, certainly. Unschooled in dating politics and proprieties, yes—as only a girl from a small country village could be once she lands in the big city. But I’ve never considered Catherine anything less than sharp. Her arguments with her love interest, Henry Tilney, attest to the mental agility of both parties.

Catherine also shows backbone, refusing to buckle under pressure to act in a way that would hurt her new friends. She stands up to what Harris calls Henry’s sexism and arrogance. Here, we have a slightly different take. Henry does open with funny sexist challenges. It’s in the nature of young males to test someone they’ve just met, male or female. It’s how young men gauge the world around them.

If Catherine had accepted his presumptions, or responded angrily, Henry would have walked away. Instead, they either pass over her head (the naïveté) or she responds with good humor. Their first long dialogue is a series of funny back-and-forths that prove that she can engage his mind, but in a way that will not grate on his ears. The only time she’s at a disadvantage is when he teases her over her Gothic imaginings. Caught up in the story he spins, Catherine may not realize he’s funnin’ her.

Janine Barcas gave the next plenary, which was on the publication history of Austen’s lower-class books—the cheap, mass-produced ones. She gave particular examples from Northanger Abbey, the book which was the theme of the conference. Barchas’s topic, which is also the subject of her newly released The Lost Books of Jane Austen, was to demonstrate that the inexpensive, nonacademic versions of Austen’s books did more to cement her reputation with the general public than all the fancy ones did.

Jeanne Talbot of San Diego visits with one of the AGM’s distinguished guests, Thomas Jefferson.

Jeanne Talbot of San Diego visits with one of the AGM’s distinguished guests, Thomas Jefferson.I had seen Barchas’s similar presentation last year and was impressed by how much she has developed it since. In tracing the history of cheap editions read by ordinary people, Barchas came upon fascinating and sad tales. As shown by inscriptions, one surviving book had been won by a young reader in school and was passed down to her younger sister. As it happened, the book had a happier life than its owners. … Even more thoughtful anecdotes grace Barchas’s book. The presentation was funny in the right places, academic in the right places, and thoughtful and respectful where the “gritty” lives of the book owners required it to be.

My wife and I had to leave before Sunday’s plenary, “Northanger Before the Tilneys: Austen’s Abbey and the Religious Past.” I heard great reviews from several friends. Moore took a fairly harsh view of the eighteenth-century owners of various abbeys, which had begun as Catholic abbeys, were given over to the big supporters of Henry VIII, and then passed down to the grantees’ descendants. General Tilney, Henry’s father, was an example of the financially entitled, and self-entitled, owners who luxuriated in their perceived superiority.

Another talk worth noting is one presented by Diana Roome, a direct descendant of Francis Lathom of The Midnight Bell. This one of the seven “horrid” novels mentioned in Northanger Abbey. Roome discussed Lathom’s life and writing. After early plays and some Gothic novels, he was banished from the life of his wife and children not only by her father but by his. His children took the mother’s name. He disappeared from the family record. A relative of hers found the connection a few years ago, sending her into serious research. No one knows what happened. Homosexuality? Incest? … He lived hand to mouth, wandered over to America, finished his life in a remote area of the British Isles. Diana looked at his situation from every angle. A mystery to this day.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Commemorating 40 Years, and 400 appeared first on Austen Marriage.

October 3, 2019

‘It was certainly a very remarkable coincidence!’

“It was certainly a very remarkable coincidence!”—Northanger Abbey.

Writing from roughly 1795 on, Jane Austen is usually seen as the last major writer of the 18th century. In many novels of that century, plot coincidences were not only accepted, they were expected. It was a big coincidence if there were not major coincidences driving the plot.

Most of them were pretty ridiculous, like an important set of cast members being shipwrecked (à la Shakespeare’s The Tempest) at just the right place and time in Ann Radcliffe’s famous novel The Mysteries of Udolpho.

Henry Fielding, another major writer of the 18th century, builds wonderful characters and scenes atop ridiculous plot contrivances. One critic praised Fielding for displaying a “great knowledge of mankind,” yet had his characters involved in such “incalculably improbable” circumstances that fairies might well have intervened to resolve the plot.

This issue of coincidences is one that bedevils every writer of realistic fiction. A coincidence here and there is fine; ordinary life has coincidences. Too many, however, and the plot ceases to be believable. As a writer who pioneered realistic fiction, Austen used coincidences too. But how much, and why?

Sense and Sensibility is her one book that has traditional coincidences straight out of the 18th century. One is that Mrs. Jennings hears second hand of the comeuppance of Lucy Steele, which ultimately frees Edmund Ferrars to marry Elinor Dashwood. And there’s Colonel Brandon conveniently overhearing of Willoughby’s marriage from two ladies waiting for a carriage. The news leads him—generously or opportunistically— to show up to express his concerns over Marianne’s broken heart.

But Austen uses these typical coincidences a good deal less than most other authors of the 18th and early 19th century. Almost always, the important matters in Austen’s fiction result from actions of the characters themselves. Usually, her coincidences clean up minor matters. Clerical livings, for example, come up twice at just the right time to settle the couple’s finances in Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park. Characters also sometimes happen onto one another conveniently, as when Elinor runs into both Robert Ferrars and her half-brother John Dashwood minutes apart at the same place in London. These happenstances save Austen a few pages of prose here and there but don’t alter the course of the character-driver production.

A major coincidence in Pride and Prejudice involves what I call the “gathering of the cast.” Four different outsiders—Darcy, Wickham, Mr. Collins, and Mrs. Gardiner—all arrive at the small town of Meryton within a few weeks of each other. All have some degree of association with each other, and all become involved with the heroine, Elizabeth. These circumstances are not real likely.

To me, this string of coincidences is a lot like the coincidence that opens The Tempest. What are the odds that the same Italian court that banished Prospero twenty years earlier is now wrecked on the very same island he was? It’s about the same as Austen winning the English state lottery. Does anyone care about Shakespeare’s contrivance? It’s a device to bring everyone together and set the action in motion.

What matters is how the characters behave once they are all on stage together. Though The Tempest is not realistic fiction, the characters do behave realistically once they begin. With almost any novel, a reader can ask, how plausible is it that these two (or more) people end up at the same place at the same time to kick things off?

In one sense, it’s completely implausible that a particular boy, Pip, would meet and help a particular escaped convict at the start of Great Expectations—one who later wants to repay the favor. Yet some kid likely did meet some convict loose in England in the age when naval hulks were used as prisons.

What are the odds that Nick Carroway would meet Gatsby when and where he did? Yet somebody would have.

Hemingway (the other one), known for his hard-core realism, has two different sets of lovers meet “coincidentally”—one at a war hospital and one in the middle of a war zone. How likely is that? Well, the first one is based on something that happened to Ernest himself. More broadly, young people facing death tend to hook up. They’ll meet somewhere, somehow.

In a more Austen-like vein, how did the French lieutenant happen to meet up with that particular lady—while being watched by that particular spy—at none other than Lyme, on the very Cobb where Austen set one of her most popular novels? The reason is that John Fowles loves Lyme, where he lived much of his life, and also appreciates Austen. He had to have the officer and lady meet somewhere to open his novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman!

And in the Regency era, young people actively sought out opportunities to meet others. If the Bennet girls had not met these particular eligible bachelors, they’d have met others, especially with Mrs. Bennet on the job. Other meetings would have led to other romantic entanglements.

In other words, the way any group of characters meets in a fictional setting to start a novel’s activities is going to have some element of contrivance. Even more when you ask the question: How did the narrator also end up there reporting the scene? There must be some “willing suspension of disbelief” about the opening of almost every work of fiction.

In Pride and Prejudice, it’s reasonable that a rich bachelor and his friends would move into a country neighborhood to get away from London. It’s reasonable that Mrs. Gardiner showed up; she’s a relative at a time when people regularly traveled to visit family. It’s reasonable that at least one gentleman in that area would have an entailed estate that would bring someone like Mr. Collins around. Austen actually could have staggered Mr. Collins’s arrival because he makes enough of a fool of himself in the Bennet home that he didn’t need to be a doofus at the dance. However, his actions reinforce his character in a reasonable way, and having him come at a different time might have added another scene or two that would be otherwise unneeded.

The least likely coincidence is the convenient encampment of the militia at Meryton, bringing the villain onto the stage. Yet, the militias did move around regularly. Many small towns dealt with the influx. Many had the same result—foolish young girls entangled in an unseemly romance, and local businesses left with unpaid bills. To get Wickham there without the militia, Austen would have had to come up with some other complication that might not have been any more plausible than what she does. (Adrian Lukis shown above as Wickham from the 1995 BBC production.)

In other words, a little “compaction” of characters and plot is a reasonable tradeoff at the beginning, when there are a lot of characters and actions to set in motion. (Compaction is common in movies, when directors combine two or three characters from a novel to simplify some of the plot.)

Consider the alternative. If Austen had spread the arrivals more realistically over, say, ten months instead of ten weeks, how would she have filled the time in her novel? What would Austen have plausibly written about to cover anything more than a short time in which the cast assembles?

Would she fill it with “shade,” by having it “stretched out here and there” with a long and extraneous chapter—“some solemn special nonsense” or “something unconnected with the story” such as an essay on writing or a critique of Walter Scott? In a letter of 4 February 1813, Austen speaks of having “lopt and cropt” Pride and Prejudice so much that she might need to add such extraneities to make it weighty enough.

We don’t know what she cut, or whether the decision was hers or her publisher’s. It’s entirely possible that she was asked to sharpen the opening and that she “loptd” a much longer and slower gathering of her team.

Regardless, economy in fiction requires the cast to collect in a reasonable period of time. So Austen gathers them quickly. She trades off coincidence for the ability to set a lively—and realistic—story into motion quickly.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post ‘It was certainly a very remarkable coincidence!’ appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 5, 2019

Austen’s Letters, Rooms, TV, and Library …

This month’s mailbag brings a bundle of news related to Jane Austen. Autumn is a busy season for our favorite author!

First is that Jane Austen’s House Museum has been able to purchase a section of one of Jane’s letters, thanks to a generous outpouring of public support. The letter, from Jane to her niece Anna, was written in November 1814, when Jane was in London negotiating a second edition of Mansfield Park with her publisher Thomas Egerton. (The talks were unsuccessful.) The letter becomes one of the museum’s centerpieces in its celebration of seventy years in operation.

Speaking of her letters, the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford have put the text of all of Austen’s known surviving letters online. Here’s the story, with some excerpts and background, and here’s the link to the letters. The text of the letters is from R. W. Chapman’s second edition. Oxford has also published Deirdre Le Faye’s more current fourth edition of the letters; the assumption is that the text is identical.

Austen lovers also have the opportunity to see where Jane lived with her brother Henry when she was in London. In fact, the apartment may still be available to lease, at the bargain London price of only £1,395 per week.

Austen’s unfinished work Sanditon has been developed into an eight-part TV series. It’s premiered in England and is destined for U.S. shores, probably next year. First, what is Sanditon itself—Jane’s written piece? Next, what should viewers expect—not a traditional sitting room comedy! The producer, Andrew Davies, tells viewers not to watch the production on a smartphone—they’ll miss too much of the period detail. (See Rose Williams above in the ITV production for an example of period detail.)

Davies also lets it drop that still another Sanditon might be on the way.

In another kind of visual art, a photographer cut her teeth working with women in the army and in rugby. Only then did she feel capable of taking on the challenge of 21st century women dressed in Regency gowns. She came upon the Jane Austen Festival in Bath …

Last but not least, McGill University in Montreal has created a digital version of the library of Jane’s brother Edward at his home in Godmersham, Kent. The virtual library collection is called “Reading with Austen.” The digital books are lined up where they were on the original shelves. Users can click on each book to gather additional data and inspect the digital copy. (Note: to see all of the collection, viewers must check the “East Wall” on the left and the “West Wall” on the right of the display of the main bookshelves.)

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Austen’s Letters, Rooms, TV, and Library … appeared first on Austen Marriage.

August 7, 2019

Third Time’s the Charm: More Fun Facts about Austen

Though this may not be as exciting as Sheldon’s “Fun With Flags” segments on The Big Bang Theory TV show, today’s episode features the “Third Time’s the Charm Quiz” with questions about Jane Austen’s life and times. (It’ll also be the last quiz, so all those who stress over test-taking can look forward to a quiet future.)

For those who want to revisit the previous torture, here is Quiz #1 and here is Quiz #2. (Hint: Each will help with one question today.)

Like John and Fanny Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility winnowing their contribution little by little to their stepfamily, the number of questions has been reduced in each quiz, but by and large the questions have gotten harder. Today’s quiz may tax your Regency knowledge. It pertains to people and events current during Jane Austen’s time, but not all of them popped up directly in her novels. Let’s call these the graduate-level questions. However, two questions relate to the earlier quizzes, and one is included for extra credit. As before, there’s no rhyme or reason to topics or order. The answers appear below each question to avoid vertigo from excessive scrolling.

Rating scale:

0-5: You’re the bumbling Mr. Collins of Austenia.

6-9: You’re Edward Ferrars/Edmund Bertram: solid but dull.

10-12: You’re Henry Tilney, learned on topics from muslin to crown lands to Udolpho.

13-15: You’re Liz Bennet, fiercely demolishing all comers.

The quiz:

Why were both the French and English slow to let women fly in hot-air balloons?

Both the French and the English hesitated to let women ascend in a balloon for fear of the effects of altitude on their “delicate” bodies.

Beyond the possible biological effect of altitude on women, what was the major fear about women “going into space”?

Just as it was considered improper for an unengaged man and woman to have private carriage rides, society was concerned about the morality of an unchaperoned couple in a hot-air balloon. One can only wonder what Elinor’s reaction would have been in Sense and Sensibility if Marianne and Willoughby had soared alone into the wild blue yonder. (She would not have looked on benignly as she does when Willoughby brings Marianne flowers, in the above photo from the 1995 movie!)

Even before they read the newspapers that came from London, how would ordinary citizens know of a British victory in the wars with France?

To celebrate British victories, the coaches were decorated. At night, candles and lamps were lit, and formal illuminations were held in large towns.

Lord Nelson won the major sea battle at Trafalgar, off the Spanish coast, that ended the threat of a French invasion. How was hero-worship for him expressed?

Egyptian-style ladies’ hats celebrated his earlier victory on the Nile; special needlework stitching was created; and housing developments were named for him. Jane Austen satirizes the commercialization of military victories in her last, unfinished novel, Sanditon. A real-estate developer laments his having named a building Trafalgar House because “Waterloo is more the thing now.” However, he’s keeping Waterloo in reserve for the name of a housing crescent (a semicircle such as in Bath).

What was the major cause of death in the French army during Napoleon’s catastrophic winter retreat from Moscow in 1812?

The French suffered hideous losses from typhus as well as from defeat in battle.

What likely most antagonized the British public over the behavior of His Royal Highness as both Prince Regent and later as King George IV?

Though his philandering and his personal attacks on his wife, Caroline, riled many citizens, his worst fault was extravagant spending at a time when England was heavily in debt from the war. Repayment of his personal debts earned its own line item in England’s budget. When the Prince Regent, now George IV, died, the Times of London remarked that “there never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures.”

What were the political ramifications and the unintended consequences of the tax on hair powder during the Napoleonic wars?

A tax on hair powder in the early 1800s made it possible to tell political affiliation at a glance. Tories wore wigs, paying the hair-powder tax. Whigs, who opposed the war, stopped wearing wigs to avoid the tax. By the time the government reduced the tax, a more natural hairstyle had become fashionable. This marked the start of the Romantic era, when hair could be as wild as the heath.

Though Janeites recall the intelligence, wit, and character of her father and brothers, what medical problems did the males in Jane Austen’s family suffer?

Austen had an uncle and a brother who suffered the same serious mental and physical handicaps, apparently genetic. Both were reportedly “deaf and dumb.” Both lived away from the family. The son of her cousin Eliza died of epilepsy. More distant male family members also suffered serious neurological problems.

Before England ended the slave trade in 1807, how much did slaves cost in the West Indies and other British possessions?

The average selling price for a healthy adult male was about £50; women and children were less. It was usually cheaper to work a slave to death and buy a new one than it was to feed and care properly for a slave.

Several Austen family members, including Jane, were abolitionists, or at least no fans of slavery. Did Britain’s 1807 abolition act end slavery?

No. In the U.S., “abolition” usually meant the end to slavery, which did not begin to occur until 1863. In England, “abolition” meant only the end of the slave trade—the capture and sale of slaves in Africa. The hope was that the end to the slave trade would lead to better treatment of existing slaves. Both sides of the argument thought that the end of the slave trade would eventually end slavery itself. After the legal end to the slave trade in 1807, the British government did little to enforce the ban until 1811, when violation of the act was made a felony.

Two generations of Austen naval officers—her brothers Frank and Charles and their self-named sons—intercepted slave ships.

England did not abolish slavery until six months after the death of the great abolitionist William Wilberforce in July 1833. The end to slavery was phased in over several years, beginning in 1834. Slave owners received twenty million pounds in recompense.

Does Jane Austen ever touch upon the slave trade in her novels?

Yes, a surprising number of times. In Mansfield Park, the Bertram family’s wealth comes from a sugar plantation in Antigua. The heroine, Fanny Price, brings conversation to a halt when she asks about the slave trade. In Emma, both Jane Fairfax and Mrs. Elton make a passing reference to it. Mrs. Elton’s remark is hypocritical. She claims that her family, which has likely been involved in the slave trade, is “rather a friend to the abolition.” In Persuasion, Mrs. Smith’s estate is tied up in the West Indies, meaning a slave-based business. In her barely begun novel Sanditon, Austen introduces a wealthy “half mulatto” teenage girl. The wealth would have come from her white parentage, almost certainly a slave business. It’s unclear whether Miss Lambe would have become a major character.

What were the most dramatic changes to transportation during Jane Austen’s lifetime?

Steamboats and railroads entered service in England in 1812, though railroads did not become commercially feasible until 1825.

What was an obvious marker of the huge disparity of wealth in England during Jane Austen’s lifetime?

The cost of housing. The finest houses in London rented for £750 a year—more than what Jane Austen earned in her lifetime from writing.

Why did Jane Austen’s cousin, Eliza de Feuillide, give up her carriage in 1797?

The major reason was a new tax on carriages to support the war against France. These taxes would have affected all the wealthy in Austen’s novels, not only for carriages but for sporting horses. In December 1797, Eliza, who was soon to marry Jane’s brother Henry, complained: “These new Taxes will drive me out of London, and make me give up my Carriage.”

What Austen relative narrowly escaped hanging or banishment to Australia?

Jane Austen’s Aunt Leigh-Perrot was acquitted of stealing a card of lace from a shop in Bath. Though the theft may have been a setup by the store proprietors, Aunt Leigh-Perrot had a reputation for kleptomania. Her own lawyer questioned her veracity. Another case against her, for stealing a potted plant, was dismissed when a witness conveniently left town.

For extra credit:

Where did “bobbies,” the nickname for London police, originate?

English policemen are known as “bobbies” after Robert Peel, who created the first English police force, in London, in 1829. Early on, they were also called “peelers.” Peel served in Parliament almost nonstop from 1809 until his death in 1850. A protégé of Lord Wellington and a moderate Tory, he nonetheless supported many liberal reforms that kept the country from coming apart. These included Catholic emancipation in 1829, the voting reforms of 1832, the end to slavery in 1833, and child-labor reform in 1833. Because of the Great Famine in Ireland in 1845, he broke with the Tory Party to help end the Corn Laws, which had kept grain prices artificially high for more than thirty years.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Third Time’s the Charm: More Fun Facts about Austen appeared first on Austen Marriage.

July 11, 2019

Another Look at ‘Pride and Prejudice’

I’ve seen most of the television and movie productions of Pride and Prejudice. I’ve enjoyed almost all of them. Like most people, my favorite is probably the 1995 television production with Jennifer Ehle as Elizabeth Bennet and Colin Firth as Darcy. The reason has as much to do with the length—it is a six-hour miniseries—as with the casting. In contrast to a ninety-minute or two-hour movie adaptation, the six hours of screen time allow the script to more fully develop the plot lines in the novel and more faithfully encompass Jane Austen’s spirited dialogue.

My least favorite is the 1940 movie starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier. It’s not just that the leading players were a decade too old (36 and 33, respectively), or that the costumes were from the wrong time period, or that the story became pure comedy. (Lady Catherine not only ended up the star but for some reason her mannerisms reminded me of the Good Witch from the Wizard of Oz.)

It’s hard to believe that Aldous Huxley, the serious author of Brave New World, was one of the screenwriters. He might as well have penned the script for a Three Stooges movie. What rankled me most, however, is that Olivier smirks his way through the entire production. It’s as if he can’t believe he signed up for something this awful.

The 2005 film starring Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfadyen is the de facto standard for the shorter movie or TV versions. For pure enjoyment, however, my favorite movie-length adaptation is the 2004 Indian version, Bride and Prejudice. It stays true to the best parts of the original while also infusing the story with an exuberance that the stiff-upper-lip set seldom achieves.

It was with great interest, then, that I watched the recent Pride and Prejudice: Atlanta, a modern-day version set in the black community of the American city. I waited to see the Lifetime movie until a few days ago because I needed to re-read the novel for other reasons and thought it would be good to finish the book first.

There’s a fair amount to enjoy about this 2019 made-for-TV movie, directed by Rhonda Baraka. The cast is attractive and engaging; the men in particular have been cast to draw swoons. Lizzie (Tiffany Hines) and Darcy (Juan Antonio) have great chemistry, though not a lot to do. Mr. and Mrs. Bennet (Reginald VelJohnson and Jackée Harry)—happier than in the book—play off each other well, and the new reverend in town (Carl Anthony Payne II) is as self-satisfied as Austen’s Mr. Collins. He turns out not to be as flawed as the original, which is unfortunately true of everyone.

The Bennet family of “Pride and Prejudice: Atlanta” throws a lot of energy and charm into trying to overcome an abridged script. The result is fun but misses the complexities and seriousness of Austen’s masterpiece.

The Bennet family of “Pride and Prejudice: Atlanta” throws a lot of energy and charm into trying to overcome an abridged script. The result is fun but misses the complexities and seriousness of Austen’s masterpiece.Purists may wince, but I enjoyed the conversion of some of Austen’s lines to the colloquial, as when Bingley (Brad James) and his sister Caroline (Keshia Knight Pulliam) arrive and Mrs. Bennet says in a voiceover: “Everybody knows that a single man with money needs to get himself a wife.” (Notice that, as here, many Southern colloquialisms have a strong iambic rhythm: That’s often the reason for seeming filler words.)

Other changes place the movie in a contemporary setting. Lizzie is a political activist; Darcy is a political moderate she sees as a sellout. Bingley is a pro golfer; Jane (Raney Branch) is a widow with a child. Lady Catherine is just plain Catherine (Victoria Rowell), but she’s as arrogant and obnoxious as the worst aristocrat. One high-quality twist is when Catherine claims that Jane is a uniquely modern gold-digger, a “baby momma” looking for a pro athlete to support her.

Maybe half such original lines by screenwriter Tracy McMillan work well. Another is when Lizzie says: “If a woman ain’t happy alone, she won’t be happy with a man.” (Like many Southerners, this well-spoken character reverts to the colloquial when feeling strong emotions.)

P&P: Atlanta would work better if we returned to the best of Austen’s dialogue (even updated) when matters involved personal relationships. Lifetime, however, decided not just to have the requisite happily-ever-after ending but to remove any meaningful conflict whatsoever. This may have been the result of abridging the story to leave plenty of room for commercials. I wonder how frustrated the screenwriter McMillan must have been when given too little time to develop a serious plot.

Darcy has no real negatives to offset his looks. In the book, he looks down on the Bennets and thinks Jane does not care for Bingley. As a result, he pulls Bingley away. In the movie, he separates Bingley from Jane because, until now, Bingley has been a player. He’s afraid Bingley will hurt Jane. Darcy and Lizzie never have any blistering back-and-forth dialogue because Lizzie seldom gives him a chance to speak. Wickham (Phillip Mullings Jr.) reforms before he’s really done anything wrong. Lydia (Reginae Carter) has a few saucy moments but reforms even faster than Wickham.

With no real drama to work through, the actors imbue the characters with more zest than the script deserves. This makes the movie fun without any serious undertones. The serious undertones were there but did not directly show on screen. Harry told the New York Post that one of the film’s sets had at one time been a plantation house, “where they kept slaves in their quarters, and they told us all the history. … So you go [to the house] and do your thing, but you feel the ghosts of it. It really made it all the more real to what we were doing—a black version of a classic.”

In a movie filmed lovingly in Atlanta, the actors seemed to take great pride in recreating a standard, even a highly shortened version. They clearly enjoyed displaying a minority culture of middle-class, upper-middle-class, and wealthy blacks. This is a welcome contrast to the usual grim, poor, crime-ridden stereotypes of black urban life. That may be the best thing about Pride and Prejudice: Atlanta. Viewers see a vibrant community of generally happy people enjoying solid lives any of us would want to have.

(Images from Lifetime.)

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Another Look at ‘Pride and Prejudice’ appeared first on Austen Marriage.

June 12, 2019

More Questions–More Answers!–on Austen’s Life and Times

Last month’s pop quiz was so much fun that we’ll do another one today. These questions go somewhat further afield, so they may tax your Regency knowledge. As before, there’s no rhyme or reason to topic order. Today’s quiz has twenty-five questions. The answers appear below each question to avoid vertigo from excessive scrolling.

Ratings:

0-10: You’re the bumbling Mr. Collins of Austenia.

11-15: You’re Edward Ferrars/Edmund Bertram: solid but dull.

16-20: You’re Henry Tilney, learned on topics from muslin to crown lands to Udolpho.

21-25: You’re Liz Bennet, fiercely demolishing all comers.

The quiz:

What did the word “particular” mean with a young couple at a Regency ball?

Couples were said to be too particular at a Regency ball when they paid too much attention to each other. A couple being particular could start the gossip tongues wagging.

What military technology did France invent that led to fears along the English coast?

France invented the hot-air balloon, as well as the parachute. England feared an airborne invasion for much of the Napoleonic age. Though an aerial invasion was unfeasible, the French played up the fears to unsettle their enemies.

Who was the first Englishwoman to ascend in a hot-air balloon, and what was the result?

The first Englishwoman to ascend in a balloon was Mrs. Laetitia Sage in 1785. Her escort being a handsome young man, the flight gave rise to scandal. Years before, the French had convened meetings to determine whether it was proper for a single lady to ascend alone with a man.

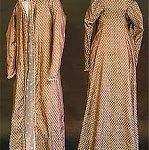

Jane Austen’s House Museum has a brown pelisse, a silk outer garment, believed to have belonged to Jane Austen. What is the symbolism of the oakleaf pattern on the pelisse?

The ships of the Royal Navy were made of oak. The oakleaf pattern was a symbol of the navy, likely in honor of Frank and Charles, her brothers who were naval officers. (See photo by headline; © Hampshire Museums Services.)

How much material would a Regency gown or pelisse require?

It took about seven and a half yards of material to make a gown or pelisse during Jane Austen’s day. Labor was the cheapest cost of any garment. The combined cost of one pelisse each for Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra was 17 shillings.

How long were England and France at war during Jane Austen’s life? (The answer is precise, but you can round up to a full year.)

Of Jane Austen’s forty-one years, seven months of life, England and France were at war for twenty-eight years, eleven months.

What was the solution for modest Regency ladies wearing their light, transparent summer dresses?

Because summer dresses were so light, women often wore full-body, flesh-colored pantaloons beneath them.

Of all the scientific discoveries or developments that occurred during Jane Austen’s lifetime, what may have been the most important, or at least the most convenient?

Joseph Bramah patented a valve-operated water-closet (toilet) in 1778. Over the next thirty years, bathrooms for the wealthy moved indoors from the “necessary” houses close by. It took well into the twentieth century for indoor toilets to become generally available.

Who may have been the most important scientist that Jane Austen met in her life?

Jane Austen very likely met Mary Anning, who became a major paleontologist, when Mary was four or five years old in Lyme Regis. Mary’s father, Richard, was a carpenter and fossil collector in Lyme Regis. He provided a bid for furniture repair to the Austen family while they lived in town. The Annings also sold fossils in the town market, where Austen likely met the young girl.

What traditional occupation was threatened by the paranoia about a French invasion of England?

Itinerant sketchers were feared to be spies, especially if they were sketching scenes of a port town.

How did Beau Brummell, the fashion arbiter of the Regency world, spread his taste in clothing?

Brummel would dress in fashionable outfits, then sit in the window of White’s gentleman’s club to watch passers-by watch him.

Beyond writing poetry and chasing women, at what other sport did Lord Byron excel?

The poet was considered a good boxer for his size (5 foot, 8 inches) despite having a club foot.

In his brief return to power in 1815, what did Napoleon do in a futile effort to curry favor with the British?

Napoleon agreed to end France’s slave trade. However, this did not save him from defeat at Waterloo, and the royalist government that replaced him did not enforce the ban with any enthusiasm.

Though Jane Austen insists that people should not marry for money—that marriage must involve respect and understanding—how many of her six finished novels open with references to money?

Four of her novels begin with discussions of finance, three in the first sentence: Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma.

What other novel quickly gets to money as well?

Persuasion soon moves from Sir Walter admiring his family history to the need for him to address the financial problems of the Elliot family. “Retrenchment” is the topic of the second chapter.

Beyond writing, what other artistic skill did Jane Austen possess?

She also played the piano-forte. She collected sheet music and copied out musical scores for her own use.

What does the use of the word “must” involve in Jane Austen’s novels?

According to critic John Mullan, whenever Jane Austen uses the word “must” in her narratives, she is beginning to move into the thoughts of her character.

Though he was known mostly for his partying, womanizing, and overspending, what signature accomplishments did the Prince Regent oversee?

The Prince Regent technically presided over the end of the War of 1812 with the United States and over the twin defeats of Napoleon in the Napoleonic wars. However, historians believe he contributed little leadership during these difficult times.

What signature honor did the Prince Regent offer Jane Austen that she grudgingly accepted?

The Prince Regent let it be known that Austen could dedicate her book Emma to him. It was an honor Austen could not refuse despite her contempt for his profligacy.

What was the most remarkable agricultural achievement during the Regency?

For the first time in history, food production increased faster than human food consumption. Among other things, the average weight of sheep and cattle more than doubled.

How were circulating libraries funded in Jane Austen’s day?

Circulating libraries charged according to the number of books a subscriber took at one time. A typical three-volume novel would count as three books.

Of the many taxes in England to finance the Napoleonic wars, what was the largest tax on luxury or personal items? Extra credit: What was the smallest tax?

The carriage tax was probably the highest personal tax: £8.16s for one carriage; £9.18s for a second; and £11 for each one after that. One of the few taxes that targeted poor people was the three-pence tax on a cheap worker’s hat.

What was the income range for the majority of the population during Jane Austen’s lifetime?

An unskilled farm laborer made about £25 a year, supplementing his pay with food and livestock he would provide for himself. A well-to-do merchant would make £2,000.

How much did Jane Austen and her mother and sister live on after her father died?

The Austen women lived on between £400 and £450, about half provided by their brothers. At Chawton, they also lived at their brother’s cottage without charge.

What was likely the most physically exacting regular activity for most young ladies in the Regency era?

Dancing. Balls could last six to eight hours, and many young people would dance every dance.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post More Questions–More Answers!–on Austen’s Life and Times appeared first on Austen Marriage.