Collins Hemingway's Blog, page 5

November 1, 2017

Last Pieces Snap into Place in Austen Puzzle

Stepping back 200 years, what we see in Jane Austen’s personal life are tantalizing hints of relationships but primarily obfuscation about any possible romances from 1802, when she was 26, until her retirement to Chawton Cottage with the other Austen women in 1809. As described in my last two blogs,...

Read More

The post Last Pieces Snap into Place in Austen Puzzle appeared first on Austen Marriage.

October 5, 2017

A Dance to Time: When Wellington Became a Janeite

The “Long War,” as it was known in the day, raged between England and France during almost all of Jane Austen’s adulthood. Two of her brothers served in the Navy, and the others served in or supported the Militia. England’s problem from the start was that it had no effective way to take the war to Napoleon in Europe. That changed with the Peninsular War, which began in the summer of 1808.

Austen’s home county of Hampshire had the major naval installation at Portsmouth. The calm waters of Spithead, between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, was where the fleet gathered to go out to fight—and where the shattered remnants of General Sir John Moore’s army returned in January 1809 after the initial, failed expedition to Spain.

Moore’s campaign was designed to open a southern front against Napoleon, to enable the British army to get a foothold on the continent. Until this time, as Napoleon put it, France was the elephant, the most powerful force on land, and England was the whale, the most powerful force at sea. There was no way for one to take the war to the other.

Austen mentions the Spanish campaign in letters to her sister Cassandra in January 1809. Jane was at Southampton, the civilian port twenty miles up the road from Portsmouth, and Cass was at Godmersham with the family of brother Edward after the sudden death of Edward’s wife, Elizabeth, after childbirth. When news of the army’s reverses reaches England, Jane says that brother Frank, stationed at Portsmouth, “may soon be off to help bring home what may remain by this time of our poor Army, whose state seems dreadfully critical” (10-11 January 1809).

On 24 January she writes again of the “grievous news from Spain,” including the death of Sir John in the final battle that protected the army’s embarkation for home—the largest British military evacuation until Dunkirk in World War II. On 30 January she follows with seemingly callous remarks: “I am sorry to find that Sir J. Moore has a Mother living, but tho’ a very Heroick son, he might not be a very necessary one to her happiness. I wish Sir John had united something of the Christian with the Hero in his death.—Thank Heaven! we have no one to care for particularly among the troops—no one in fact nearer to us than Sir John himself.”

The reason for Austen’s catty remarks about Sir John’s un-Christian views is unclear. He was a military officer respected for his courage and tactical abilities but not for his strategic thinking. His army’s foray into central Spain was a deliberate effort to draw the French army away from England’s beleaguered Spanish allies, but the action nearly allowed Napoleon to get behind him with an army twice the size of his own. It is also unclear whether Frank helped evacuate the army. He was in charge of their disembarkation at Portsmouth, and it appears that his ship, the St. Albans, remained in port, but there is a chance it dashed out to help.

What is curious about the Moore campaign—and how the story loops back to the Austen family 150 years later—is that it should have been the action of General Sir Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington. Wellesley was a highly regarded officer who resigned from the army during a multi-year lull in action to enter politics. He returned to service when it became clear that England was going to find a way to strike at Napoleon on land.

Wellesley won a major victory at Vimeiro, Spain, in the summer of 1808; was replaced on the same day by two more senior but less experienced generals; and the terms of surrender for the French were so generous that all three officers were recalled to explain themselves. Frank Austen watched the battle unfold from his ship and ferried the wounded and captured home.

Moore, the most senior officer remaining in country, led what became the disastrous winter offensive. Later in 1809, Wellesley returned to Spain to badger Napoleon for several more years. Sir Arthur never had enough forces to directly battle one of the massive armies of the French, but he would move into northern Spain when Napoleon deployed his troops elsewhere and would withdraw in orderly fashion to a coastal fortress when the French returned.

After Napoleon’s own winter disaster in Russia in 1812, he no longer had reinforcements to send to Spain, and Wellesley (now Duke) punched into southern France in 1813, leading to Napoleon’s first abdication. Wellington, of course, led the British at Waterloo after Napoleon returned to power, the victory bringing more fame and riches to himself and his family. Wellington followed with a distinguished, largely conservative career in government.

One of the prizes for the Duke was the 7,000-acre Stratfield Saye estate in northeast Hampshire, which was sold to the nation for £600,000 in 1817 to present as a reward to the Iron Duke. The original plan was to build a Waterloo Palace to rival Blenheim Palace, home of the Duke of Marlborough, the great military hero of the previous century. Though that plan proved to be too expensive, the Stratfield Saye estate and house, about 22 miles north of Chawton, where Austen lived her final years, have remained in the family ever since.

Stratfield Saye was purchased for the Duke of Wellington by a grateful nation and has been home to the family since. The seventh duke and his literary friends sallied forth from this estate in Hampshire to attend meetings of the Jane Austen Society in Chawton.

Stratfield Saye was purchased for the Duke of Wellington by a grateful nation and has been home to the family since. The seventh duke and his literary friends sallied forth from this estate in Hampshire to attend meetings of the Jane Austen Society in Chawton.I was giving a series of talks to the Jane Austen Society of Australia (JASA) about the war and its effects on the Austens, when Ellen Jordan, of the Centre for Literary and Linguistic Computing at the University of Newcastle, Australia, approached me about my knowledge of an Austen-Wellington connection. I knew that the Wellington home was close to the Austen haunts, but nothing else. Ellen not only explained how the world of Wellington and the world of Austen intersected but also was kind enough to send direct citations that explained them.

The seventh Duke of Wellington, great-grandson of our Sir Arthur, was the third cousin of Violet Powell, the wife of novelist Anthony Powell, famous for his twelve-volume Dance to the Music of Time. A shared interest in Jane Austen was one highlight of their friendship. In their autobiographies, the Powells explain the Duke’s love of Austen and his support for the Jane Austen Society in the 1950s.

(It should be noted that military service has remained a part of the Wellington tradition. The first eight Dukes all served in the military. Gerald (Gerry), the seventh duke, inherited the title from his nephew, Henry, the sixth, when the nephew was killed in World War II leading a commando force in Italy.)

After World War II, Anthony Powell said, they came to know Gerry quite well, often staying at Stratfield Saye. “Gerry Wellington’s great literary passion was for Jane Austen, a novelist on whom Violet is expert, and for some time the two of them maintained a correspondence, purporting to be exchanged between Austen characters, though more ribald in strain. … A firm tradition grew up for us to … attend the annual meeting of the Jane Austen Society, held in the gardens of Chawton House.”

Violet proved to be a true Janeite, passing the Duke’s test on her knowledge about Austen’s works. Violet says: “In 1958 we were again invited … to attend the AGM of the Jane Austen Society at Chawton. This was partly the result of my having correctly answered Gerry’s two test questions. Where in Jane Austen is there a scene of transvestism and where is the word ‘dung’ mentioned? The transvestite scene occurs in Pride and Prejudice when one of the officers who so excite the younger Miss Bennets is dressed up in a gown belonging to their vulgar aunt, Mrs. Phillips. It is in Persuasion that collision with a dung cart is averted by the skill of Mrs. Croft’s intervention, when out driving with her husband, the genial Admiral.”

The trips to the AGM became a custom involving still another respected novelist, L. P. Hartley, best known for The Go Between. Violet continues: “A tradition grew that a house party at Stratfield Saye should drive over to the [AGM]. … An eccentricity of this literary house party was that the two novelists, Anthony Powell and L.P. Hartley, regarded Jane Austen with sincere respect, but with less than total commitment, and jibbed at the esoteric exchanges so enjoyed by Gerry and myself.”

In addition to Jane Austen’s Letters, January 1809, sources are:

Powell, Anthony. 1980. To Keep the Ball Rolling: The Memoirs of Anthony Powell. Vol 3: Faces in My Time. London: William Heinemann, pp. 123-4.

Powell, Violet. 1998. The Departure Platform: An Autobiography. London: William Heinemann, pp. 137-8.

The post A Dance to Time: When Wellington Became a Janeite appeared first on Austen Marriage.

September 6, 2017

A Modest Proposal: Might the Spinster Have Married?

As reported in last month’s blog about Jane Austen’s romantic attachments, biographers dutifully recount the story of Jane’s acceptance/rejection of a proposal by Harris Bigg-Wither, a young, brash man six years her junior, on Thursday-Friday, 2-3 December 1802.

The story goes that Jane and Cassandra journeyed to Manydown, the Bigg-Wither estate, for several weeks of leisure with the family. The Austen ladies were good friends with Harris’s sisters, especially Caroline and Alethea. On 2 December, Bigg-Wither surprises Jane with a proposal. Overwhelmed at the prospect of becoming mistress of a large estate, Jane accepts this proposal from a person with little to recommend him except wealth. She reconsiders overnight; recants her acceptance in the morning; then flees back to Bath in humiliation. (A woman could accept and reject a proposal then; a man could not withdraw one without the woman’s consent.)

What is distinctly odd about this history, however, is that this purported engagement and refusal, which would have created a scandal, does not appear to show up in any surviving contemporaneous letters or journals by anyone who knew Jane.

When I began to analyze the details of Austen’s life eight or nine years ago for historical fiction based on her life, I recognized that the references all went back to Caroline, daughter of her brother James and sister-in-law Mary, “the Steventonites”—so called because they replaced the Austens’ father and his family at the Steventon rectory when the elder Austen retired to Bath in 1801. I knew Caroline sourced the story to her mother, but it wasn’t until some years later, when it hit me that Caroline was one of Austen’s youngest relatives, that I checked and learned that Caroline had not even been born when the proposal is supposed to have happened!

Manydown Park, where Jane Austen attended many balls, flirted with Tom Lefroy, and according to one niece accepted and rejected a marriage proposal

Manydown Park, where Jane Austen attended many balls, flirted with Tom Lefroy, and according to one niece accepted and rejected a marriage proposalRecently, Helena Kelly, in her book “Jane Austen: Secret Radical,” points out the same odd circumstance: this major biographical event is reported only by Caroline, and only in 1870—68 years after the supposed incident—a lifetime! (I am in general agreement with Kelly’s take on Austen and her work in society, though I find her interpretations of the novels to be eccentric.)

Supposedly, after the disaster with Bigg-Wither, it was James who escorted the Austen sisters to Bath, so Mary would have been aware of the situation. Mary, however, was never close to Jane and died herself in 1843—26 years after Jane died, 41 years after the event, and 27 years before Caroline’s telling. Caroline was only 12 when Austen died—she recounts her last sad meeting with her aunt. Even if the Bigg-Wither topic arose in the sad conversations after her death, that still would have been 15 years after the events. Considering the reticence people have about speaking “ill” of the dead, it is easy to believe the topic well might not have come up until much later.

How is it this story is handed down by a niece too young to have known about it directly but not by the many other nieces and nephews who were alive? James Edward, her first official biographer, was 19 when Jane died–he attended her funeral on behalf of his father–yet he sources his younger sister for the tale of the botched proposal! Wouldn’t he have heard the story from his parents himself?

Stories have become legends in less time than the gaps in this recounting!

Further, descriptions of Bigg-Wither by Caroline do not seem to match to the one or two portraits of him—he is supposed to be a very large, heavy young man, but the visual evidence shows him as relatively slim. See the image at the top, by the headline–he does not seem to be the hulking, brooding young man of Caroline’s description.

Notice something else: Cassandra, an actual witness to the mysterious coastal suitor, who was going to propose to Jane in the summer of 1801 but died unexpectedly, as described in my last blog, provides almost no details about the man. Nor does she mention Bigg-Wither’s proposal in 1828 when she’s reminded of the other (expected) proposal.

Cass seems to have relayed just enough information about Jane’s coastal “romance” to confuse rather than enlighten. Cass also destroyed the vast majority of Jane’s letters from this period, leaving no other evidence of the events. We know nothing about the letters except that Caroline calls them “open and confidential”–but she gives no indication she has seen them. Why would Cass have kept the letters about Tom Lefroy, which support the idea that he (or his aunt) had dumped Jane, while burning those about those later relationships—unless at least one of those relationships was even more serious?

Though the story of any embarrassing Bigg-Wither encounter likely would have circulated for years in the “Steventonite” family (niece Fanny coined the name), the incident is too specific for one being recounted twenty, thirty, or forty years later, as likely happened. Mary provides too many details. How would she have remembered the exact date of a proposal so long before about a sister-in-law she was not close to? (Mary did not seem much fond of anyone, though in fairness she did help Cass tend to Jane during Jane’s final illness.)

Meaning the provenance of this story is suspicious, at the very least.

(The oafish Bigg-Wither married someone else in 1804 and sired ten children.)

Now that we’ve covered all the proposals, what about a possible marriage? Shocking! But the question brings us to the one letter in which Jane Austen identifies herself as a married woman, the 5 April 1809 letter to the publisher Crosby (she spells it “Crosbie”) in which she demands they either publish “Susan,” which they had bought six years earlier, or she would sell it to someone else.

The publisher quickly replies that they paid for the book (though not required to publish it) and if she sold it to anyone else “we shall take proceedings to stop the sale.” End of correspondence—though years later her brother Henry did buy the book back for Jane for the original 10£, enabling it to be published as “Northanger Abbey.”

Jane signs her letter to Crosby “Mrs. Ashton Dennis,” care of the Southampton Post Office. The publisher does not know her name—Henry handled the sale, and she was identified only as “A Lady.” The thinking is that she uses a different name to remain anonymous, and the one she uses spells out “MAD” to indicate her unhappiness at the delays. (And what prompted to her write the abrupt letter six years after the fact?)

That leads to an interesting problem. Jane has been in Southampton for some time; the post office knows her. In the autumn, she kept up a steady stream of correspondence with Cassandra, then at Godmersham, when Edward’s wife, Elizabeth, died unexpectedly after childbirth. How is Jane going to pick up a letter for a “Mrs. Ashton Dennis” unless that is now her name? Isn’t it also strange that, while Jane’s life is relatively well-known, the two proposals that have very poor provenance come in the period in which Cass destroyed almost all of Jane’s letters?

In this time, we have a three-and-a-half-year gap of Jane’s letters, 1801-1804; a year-long gap, mid-1805 to mid-1806; and a 16-month gap, February 1807-June 1808. We have only 13 letters—not quite 2 a year—from 1801 to 1808, where they begin again with some regularity. Besides the occasional passing reference to her in other people’s letters and diaries, we know nothing of Jane’s whereabouts or doings for this time.

Considering the confusion and inconsistency in reports of who she was involved with, and when—too many specifics in one major encounter (Bigg-Wither) and far too few in another (the mysterious clergyman described last time)—one must ask what was really going on. Were there multiple romantic encounters, each one ending disastrously, or perhaps one relationship that these inconsistent stories point to—or are designed to point away from?

When she signed her name as a married woman in 1809, was she MAD at the publisher about not publishing the book “Susan,” or MAD about some man the family sought to hide?

There is still time to enter the quiz and giveaway for a leather-bound collection of Jane Austen’s works.

The post A Modest Proposal: Might the Spinster Have Married? appeared first on Austen Marriage.

August 15, 2017

Brotherly Love?

In a recent blog, I wrote about the general but oft ignored belief that cousins should not marry. Cousin marriage was fashionable in Jane Austen’s time among the wealthy, but it also happened more than once in Jane’s immediate family. Her brother Henry (top, by headline) married their cousin Eliza, and the son of brother Frank married the daughter of brother Charles. Cousin marriage also occurs in “Mansfield Park,” when Fanny and Edmund are betrothed.

An even closer—and absolutely prohibited—degree of consanguinity is that of brother and sister. Sibling marriage being an incestuous taboo the world over, one would not expect such a thing ever to enter the environs of Austenia. Yet tradition brought it to Jane’s doorstep, for the law not only forbade marriage between blood siblings but also between brothers and sisters by marriage.

Therefore, the marriage of Jane’s brother Charles to Harriet Palmer after the death of his first wife was “voidable” because Harriet was Fanny’s sister. As explained in Martha Bailey’s article in “The Marriage Law of Jane Austen’s World” (Persuasions, Winter 2015), this sisterhood created a prohibition by “affinity” (marriage) as strong as one by blood. The logic was: Because Fanny and Harriet were related by blood, and because husband and wife became one flesh upon consummation, then Charles would also be related to Harriet by blood. This thinking applied equally for a woman who married the brother of her dead husband.

“Voidable” in Charles’ case did not necessarily mean “voided.” Someone—most likely a relative seeking to grab an inheritance—would have to sue to have the marriage voided and any children declared illegitimate. Charles never had enough money for anyone to bother trying to disinherit his four children by Harriet.

To resolve the ambiguity about people marrying the sibling of a deceased spouse, the 1835 Marriage Act validated all previous such marriages but voided any going forward. To evade this prohibition in still another Austen situation, Jane’s niece Louisa Knight went to Denmark in 1847 to marry Lord George Hill, who had been married to Louisa’s now deceased sister Cassandra. Such dodges continued until the affinity laws were removed in 1907.

This concept of “affinity” as a barrier to marriage brings us to the most difficult “brother and sister” pair in Austen, Mr. Knightley and Emma. Their “affinity” is not a technical one under the law but one created by proximity and time. In all but blood, Mr. Knightley functions as Emma’s older brother. He’s the good-natured scold who tries to keep a bright but undisciplined young woman on the straight and narrow and who also seeks to protect her in a fraternal way.

Modern courts have struggled with psychological affinities even when no biological issue exists. Adoptive parents have wanted to marry adoptive children, for instance. Did the love grow naturally as happens in any other relationship, or did the parent use a position of authority to groom the child inappropriately? Courts have looked at the amount of the disparity in age or the length of the relationship to try to determine the right course. Mr. Knightley is seventeen years older than Emma—and has known her since birth!

This is not to imply there is anything immoral in the Emma-Knightley relationship. Readers quickly recognize that they are the only two people worthy of the other and are intrigued at how they will surmount the barriers between them—primarily those Emma herself creates with her matchmaking exercises. This almost subliminal conflict is, however, one of many ways that Austen develops deep psychological issues in the courtship genre where other authors never reach beyond the superficial.

Their relationship begins to change as each (incorrectly) foresees the loss of the other—Emma to Frank Churchill and Mr. Knightley to Jane Fairfax. Feelings break through at the Westons’ ball.

The critical scene in the 1998 movie when Jeremy Northam, as Mr. Knightley, recognizes the shift from brother and sister to man and woman in “Emma”

The critical scene in the 1998 movie when Jeremy Northam, as Mr. Knightley, recognizes the shift from brother and sister to man and woman in “Emma”First, Emma notices his physique: “so young as he looked! … His tall, firm, upright figure, among the bulky forms and stooping shoulders of the elderly men.” Then there is his gallant rescue of Harriet after Elton’s snub. “Never had [Emma] been more surprized, seldom more delighted, than at that instant.” Finally, there is their brief but serious tête-à-tête. The well-known and memorable exchange that follows ends up redefining their roles. Note that it is Emma who nudges the two forward.

“Whom are you going to dance with?” asked Mr. Knightley. She hesitated a moment, and then replied, “With you, if you will ask me.”

“Will you?” said he, offering his hand.

“Indeed I will. You have shewn that you can dance, and you know we are not really so much brother and sister as to make it at all improper.”

“Brother and sister! no, indeed.”

The sense of this scene turns on how the key phrases are handled. In the 1972 BBC series starring Doran Godwin and John Carson, the brother-sister comments are treated as so much banter. In the 1998 movie, Gwyneth Paltrow also tosses her line out merrily. What follows, however, makes all the difference. Jeremy Northam first responds with a laughing “Brother and sister! … ” Then, as she moves out of earshot, he adds meaningfully, “No, indeed.” He understands the tectonic shift that has occurred.

When the book opens, Emma, in addition to being handsome, clever, and rich, has lived “nearly” twenty-one years. In the months that pass covering the events of the novel, she comes of age. This is not likely to be a casual choice for Austen. Twenty-one is the age of consent. This is Austen’s signal that the heroine is no longer in the junior position but is fully capable of owning this momentous swing from younger sister to adult wife.

The post Brotherly Love? appeared first on Austen Marriage.

August 10, 2017

Engaging Stories About Miss Austen and Her Beaus

How many times was Jane Austen engaged—or married (!)? Thoughts about her short life—and her emotional life, whatever it may have been—bubble up in this year of 2017, the 200th anniversary of her death.

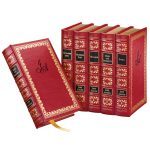

Officially, Austen was engaged once, for less than a day, to a young, callow Harris Bigg-Wither, in 1802. Because the engagement is recounted in all the Austen biographies, the answer of “one” is the correct answer in my quiz/giveaway for an Easton Press collector’s edition of leather books comprising Jane Austen’s six major novels.

(Please enter! No purchase required; contest open till 18 Sept. 2017; different quiz each week. The contest appears several items down on the Facebook page.)

Whether there was such an engagement, however, is open to speculation, as we will see next month when we drill into that proposal in detail.

This time, we consider several other beaus in the amorous history of Miss Austen.

Let’s quickly dispose of two. Clergymen figure regularly among her suitors, though her novels have only one clergyman with any pluck, and he’s a clown in his persistence. Two who came and went in her life were a Mr. Samuel Blackall in 1798, whom Jane testily labels “a piece of … noisy perfection,” and Mr. Edward Bridges in 1805. It seems these relationships went no further than the men displaying an interest in her and Jane deflecting it.

Her first and best-known attachment involves an Irishman, Tom Lefroy (above, by headline), in late 1795 and early 1796 when both were turning 20. With plans to study law in London, the lad comes down to visit his aunt, Mrs. Anne Lefroy, who was Jane’s friend and mentor. The story is that, when the flirtation becomes too serious, Mrs. Lefroy (whom many called Madame Lefroy, though Jane uses “Mrs.” in all her letters) sends Tom away before an “understanding”—an engagement—can be reached.

The reason is that Tom could forfeit the Langlois inheritance if he marries a penniless girl. In this scenario, Mrs. Lefroy is torn between her affection for Jane and her need to protect her nephew’s financial well-being, as he is there under her supervision.

This relationship is the basis of the book and movie “Becoming Jane,” which is a combination of good and bad extrapolation of their personal history. For example, “Becoming Jane” has Tom naming his oldest daughter after Jane, when a family’s oldest daughter would normally have been named after her own mother or grandmother. As luck has it, the mother of Tom’s wife is indeed also named Jane! Convenient for our Irish lawyer, as well as the movie script. …

But was the relationship that serious? Tom, whom Jane describes as a “very gentleman-like, good-looking, pleasant young man,” is mentioned in the very first extant Austen letter of 9 January 1796, when she says that his birthday was the day before. She tells her sister Cassandra that she was “almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved … everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together.” She also mentions that he will leave “soon after next Friday.”

Anne Lefroy was Jane Austen’s friend and mentor but is reported to have sent her nephew away before their flirtation became too serious

Anne Lefroy was Jane Austen’s friend and mentor but is reported to have sent her nephew away before their flirtation became too seriousSix days later she writes that “I rather expect to receive an offer from my friend” at the next day’s (Friday’s) ball, saying she “will refuse him, however, unless he … give[s] away his white Coat”—a follow-on joke about his dress. Then, on Friday, she writes that she will “flirt my last with Tom Lefroy,” adding, “My tears flow as I write, at the melancholy idea.”

Biographers have taken this to mean that she is broken-hearted, yet this is all she says to her confidante-sister about what is supposed to be a tragic breakup, and her very next remark is that “Wm. Chute called here yesterday. I wonder what he means by being civil,” and she follows with several more bits of ordinary gossip.

So: She says on the 9th that she and Tom are having great fun but he will leave in little more than a week. In little more than a week, he leaves! Hard to see this as his being shipped off in “disgrace,” as biographer David Nokes describes it. Austen being wry in almost every sentence of every letter, it’s hard to know if she is serious or joking about expecting a proposal or laughing or crying about melancholy tears.

The Lefroy and Austen families had continuing personal connections, and years later Jane’s niece Anna married Tom’s cousin Ben. No one objected to that pairing because Ben did not have wealth. Jane could keep up with Tom, but was hesitant to. In November 1798, nearly three years after the ball flirtations, Jane recounts to Cass that when Mrs. Lefroy visits she is “too proud” to make any inquiries of him. Her father does, likely on her behalf, and she learns that Tom is returning to Ireland to practice law. There, he married an old friend, eventually became Lord Chief Justice, and remembered Austen fondly.

Perhaps her heart was broken, if only a little. One suspects it was on the level of a summer vacation flirtation in which both parties know they will go their separate ways after an exciting but innocent fling. Perhaps later, considering their delightful weeks together, she hoped he might come back after completing his initial studies in London.

Tom at one time admitted that he loved Austen but in a “boyish” way. Still, in an ending to rival “Dr. Zhivago,” he traveled to England to pay his respects to her when he learned of her death on 18 July 1817, according to his family.

It’s hard to know: Had they truly fallen hard for each other and then forced apart, or were they both just tantalized by a lively start and simply wondered what might have been?

Then we have the mysterious lover at the beach in the summer of 1801, which Cassandra recounts to at least two of their nieces after Jane’s death. The story is that while the Austens are at the beach, Jane and the man meet and fall in love; they are to meet again later, where a proposal is expected. Instead, Jane and Cass receive a letter that he has died.

Tradition is that he was a clergyman, but that’s not certain; Cass says he was “pleasing and very good looking,” but never provides the man’s name. The nieces, Caroline and Louisa, cannot even agree about where on the Devonshire coast this romance occurs. Finally, Cass does not relay the story until 1828—more than a quarter-century after it is supposed to have happened, when she sees a man who evidently reminds her of the suitor.

Her nieces and nephews carry on the inconstancy about Jane’s possible relationships. In the first edition of “A Memoir of Jane Austen,” her nephew James Edward writes: “I have no reason to think that she ever felt any attachment by which the happiness of her life was at all affected.” In the next edition, however, he hints at two romantic attachments, concluding that he is “unable to say whether her feelings were of such a nature as to affect her happiness”—whether she seriously cared about either man.

Even in these comments, it’s not clear whether he is speaking of Lefroy and Bigg-Wither, one or more clergy, the beach mystery, or someone entirely different.

Next time: the Bigg-Wither proposal: Why does it not ring true?

The post Engaging Stories About Miss Austen and Her Beaus appeared first on Austen Marriage.

July 28, 2017

To Celebrate Austen’s Life, Chance to Win Collector’s Edition

Jane Austen lovers the world over have spent the last week commemorating the loss of the author at the far too young age of 41. She died on July 18, 1817, and was buried in Winchester Cathedral on July 24.

In recognition of her passing, we are inviting our fellow Austen fans to enter a contest to win a special, leather-bound collector’s edition set of her major books from Easton Press, which produces some of the finest-quality books made.

It seemed only fitting to acknowledge the loss of such a beloved novelist with an opportunity for one of her many fans around the world to win the full collection of her mature literary works.

Included in the Easton Press book collection are Austen’s well-known titles “Sense and Sensibility,” “Pride and Prejudice,” “Mansfield Park,” “Emma,” “Northanger Abbey,” and “Persuasion.”

The contest is being held on The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen’s Facebook page. Participants may enter the Austen Book Collection contest daily through September 18, 2017, for a chance to win the grand prize of the special collection of Austen’s novels. Entrants will be asked to answer trivia questions about Austen’s life and literary works; you have to complete the short quiz, but you don’t have to answer correctly to be entered into the drawing. No purchase is necessary for entry.

In addition, a monthly winner will be chosen to win signed copies of all three volumes of “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen” trilogy, my historical novels which reimagine Austen’s life and combine her close portraits of ordinary life with the grand scope of the Regency Era and Napoleonic wars. Volume III of “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen” trilogy is scheduled for release in October 2017.

Austen is one of my favorite authors and it seemed only fitting to acknowledge the loss of such a beloved novelist with an opportunity for one of her many fans around the world to win the full collection of her mature literary works. Her writing didn’t receive widespread recognition and popularity until years after her death. It’s a statement of the quality of her work that her popularity grew steadily over time and that 200 years later, she is one of the most respected and best-loved writers of all time.

While Austen achieved success as an author during the years of 1811 to 1816 with her novels “Sense and Sensibility” (1811), “Pride and Prejudice” (1813), “Mansfield Park” (1814) and “Emma” (1815), it wasn’t until the joint publication of “Northanger Abbey/Persuasion” shortly after her death in 1817 that the public knew her name—she had published anonymously during her life.

In my trilogy, I use Austen’s real life to provide a thoughtful, in-depth look at life for women in the early 1800s. I plunge the protagonist into the period’s scientific advances, political foment, wars that were among the longest and most devastating in European history—and into a serious relationship with a man very much her equal. By the end, circumstances challenge the heroine’s courage, integrity, and heart.

The series is available from Amazon or at Jane Austen Books.

The post To Celebrate Austen’s Life, Chance to Win Collector’s Edition appeared first on Austen Marriage.

July 12, 2017

Austen and the Cathedral: Was Interment a Signal Honor?

July 18, 2017, marks the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen. At that date, the official commemoration begins. Tributes will flow through any number of activities, readings, evensongs, and events, leading to July 24, the date of her funeral. In the UK, public benches are being dedicated to Austen, and the “Rain Jane” program will have Austen’s words appear in public places throughout Hampshire whenever there is precipitation. These are just a few of the many events scheduled throughout the year.

Winchester Cathedral, where she is interred, will be the focus of many of the activities. One of these will be the unveiling of the £10 note graced with her face (above, by headline). As she is also on the £2 coin, Austen will be the first person other than a monarch to appear on more than one form of British currency at the same time. Cathedral bells will toll 41 times to mark each of her years on this earth.

Her burial raises an interesting question: Why, when this comparatively obscure spinster died in 1817, was she buried in a cathedral which houses the bones of Saxon kings and saints? This, in fact, is the subject of a talk scheduled by Professor Michael Wheeler at the cathedral on July 21.

It seems highly unusual for an ordinary citizen to be buried in a place normally reserved for secular and religious leaders. According to Jo Bartholomew, curator and librarian at the cathedral, the mortuary chests hold such dignitaries as: Cynigils and Cenwalh, two Christian kings from the seventh century; Kings Egbert and Ethelwulf (grandfather and father of King Alfred); King Cnut (Canute) and his Queen Emma; two bishops, Alwyn and Stigand; and king William Rufus. Most had been originally buried in Old Minster, the predecessor to Winchester Cathedral, which was just to the north and partially beneath it.

Was it common for an ordinary citizen to be buried there in

King Cnut (Canute) is one of the ancient kings and bishops interred at Winchester Cathedral, along with Jane Austen.

King Cnut (Canute) is one of the ancient kings and bishops interred at Winchester Cathedral, along with Jane Austen.1817, or was this an extraordinary honor? In those days, not so extraordinary after all. Indeed, Jane was the third and last person buried there that year. Cost, rather than rank, may have been the limiting factor for a cathedral interment. Jane’s funeral expenses came to £92, a significant amount for someone of her means. Clearly, she or her family was determined to make a statement–after all, none of her brothers, including Frank, who died the highest-ranking naval officer in England, received such a burial.

Elizabeth Proudman, vice chairman of the Jane Austen Society and an expert on Jane Austen, said in a letter that the location was likely Austen’s choice: “I believe that she is buried there, because she wanted to be. It was up to the Dean in those days to decide who could and who could not be buried in the Cathedral. Usually it was enough to be respectable and ‘gentry.’ This, of course, she was as her late father and two of her brothers were in the church.”

Jane’s father, George, had been the rector at Steventon, fourteen miles away, until he retired in 1801. He was succeeded by James, his oldest son, who still held that position in 1817. Henry, who had taken up the cloth after his bank collapsed in the recession of 1816, also had a clerical position nearby. It probably did not hurt that Jane’s brother Edward was the wealthy inheritor of the Knight estate, with extensive holdings in Steventon and Chawton, which was sixteen miles away. From his recent ordination, Henry knew the Bishop, according to Claire Tomalin; and the Dean, Thomas Rennell, was a friend of the important Chute family who were relatives of the Austens.

Having lived at Chawton for nine years, where she wrote or significantly revised her oeuvre, Jane was taken to Winchester for unsuccessful medical treatment. “She had been ill in Winchester for about two months, and I think her burial must have been discussed,” Proudman says. “I like to think that her family would have talked about it with her, and that they followed her wishes. … It may be that she had no particular attachment to the village [of Chawton]. We know that she admired Winchester Cathedral, and she knew several of the clergy. When she died she had some money from her writing, and her funeral expenses were paid from her estate. It was a tiny funeral, only 3 brothers and a nephew attended, and it had to be over before the daily business of the Cathedral began at 10.00 am.”

In fact, most funerals were relatively small in those days, and women did not attend. Cassandra, with their friend Martha Lloyd (James’ sister-in-law), “watched the little mournful procession the length of the street & when it turned from my sight I had lost her for ever.” In that letter to their niece Fanny in the days after Jane’s death, Cass added: “I have lost a treasure, such a Sister, such a friend as can never be surpassed. … She was the sun of my life, the gilder of every pleasure, the soother of every sorrow, I had not a thought concealed from her, & it is as if I have lost a part of myself. … Never was [a] human being more sincerely mourned … than was this dear creature.”

Edward, Francis, and Henry were the brothers who attended. Charles was too far away to come. James was ill (he died two years later), but his son, James Edward, rode from Steventon to Winchester for the service. Thomas Watkins, the Precentor (a member of a church who facilitates worship), read the service. Jane was interred in a brick-lined vault on the north side of the nave.

While Jane is interred at a grand cathedral, her mother (left) and sister are buried in the churchyard at Chawton, close to the cottage where all three women lived.

While Jane is interred at a grand cathedral, her mother (left) and sister are buried in the churchyard at Chawton, close to the cottage where all three women lived.Tomalin believes it was Henry who “surely sought permission for their sister to be buried in the cathedral; splendid as it is, she might have preferred the open churchyard at Steventon or Chawton.” One suspects it was Henry who pushed for the cathedral, and Jane would have been happy to be at rest anywhere. Yet, modest as she was in many ways, she understood the worth of her writing. She may have made the decision with a view to posterity. In any event, Cassandra was pleased with the decision. “It is a satisfaction to me,” she said, that Jane’s remains were “to lie in a building she admired so much. … her precious soul I presume to hope reposes in a far superior mansion.”

Henry arranged for a plaque to be installed in the cathedral to commemorate Jane’s benevolence, sweetness, and intellect, but curiously enough, not her writing. As the popularity of her novels grew over time, officials were baffled by the pilgrims coming to visit the crypt of a woman the church knew not as a brilliant novelist but only as the daughter of a rural clergyman.

The post Austen and the Cathedral: Was Interment a Signal Honor? appeared first on Austen Marriage.

May 19, 2017

Marrying a Cousin

There’s a whole lot of marrying going on in Jane Austen’s novels. Among the major characters of her six major novels, at least nineteen couples tie the knot.

One wedding was so singular that it could have been halted in certain quarters, then and now. The marriage in Mansfield Park between Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram, who are first cousins, would have been illegal for much of England’s history and would still have been illegal under Catholic canon. Even today, marriage of first cousins is illegal in half the jurisdictions of the United States, though it is legal in other Western nations—and quite common in other parts of the world.

One wedding was so singular that it could have been halted in certain quarters, then and now. The marriage in Mansfield Park between Fanny Price and Edmund Bertram, who are first cousins, would have been illegal for much of England’s history and would still have been illegal under Catholic canon. Even today, marriage of first cousins is illegal in half the jurisdictions of the United States, though it is legal in other Western nations—and quite common in other parts of the world.

As one might suspect, English law on cousin marriage diverged from Catholic doctrine as the result of Henry VIII. His tendency to tire of a wife—and his need to sire a male heir—put him regularly in need of a new marriage. This regularly put him afoul of church doctrine.

Just as he manipulated canon law to have his first marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled so that he might marry Anne Boleyn, he later had the marriage laws altered so that he could marry Catherine Howard. Under the old law, his marriage to Howard would have been incestuous because she was Anne’s first cousin. The law applied whether a person was cousin by blood or marriage. Where before no one closer than fourth cousins could marry, the Marriage Act of 1540 made marriage legal for first through third cousins.

A ban on incestuous marriages probably preceded civilization, as people recognized that inbreeding caused deformities and other birth defects. In ancient times, no one knew what degree of separation would prevent problems, so tradition (often via religion) became very cautious.

Modern genetics largely contradict the fear of defects among the children of first cousins. Unless both carry a specific genetic problem, the risk for cousin couples is only 1.7 to 2.8 percent higher than with other couples. Conversely, cousin couples suffer fewer miscarriages. It has been posited but not proven that similar blood chemistry may account for the lower miscarriage rate.

Prince Regent, later George IV, had a disastrous marriage to his cousin

Prince Regent, later George IV, had a disastrous marriage to his cousinBy the 1800s, cousin marriage was not unusual. The most famous of Austen’s time was that between the Prince Regent and Caroline. Similar blood chemistry didn’t help much in that horrific mismatch!—a mismatch that Austen comments on in her letters when she sides with the princess.

Closer to home, Jane’s brother Henry married Eliza, their first cousin, whose exotic charm created sibling competition between Henry and James as to which cousin would win her heart. A first-cousin marriage occurred in the family’s next generation, too, when Francis, the oldest son of Jane’s brother Frank, married Fanny, the daughter of Frank and Jane’s brother Charles.

By that generation, it was estimated that about one in fifty marriages for ordinary people involved cousins vis-à-vis about one in twenty for the aristocracy and other swells; the higher number among the wealthy likely related to the desire to keep family property together. The estimate came from George Darwin, the son of Charles Darwin and Emma Wedgwood of the pottery dynasty—first cousins! Whenever his children became ill, Charles worried that they were weak from inbreeding.

Cousin marriage appears twice in Austen’s novels. In Pride and Prejudice, Lady Catherine proves the economic rationale for cousin marriage—that of building family fortunes—in her determination to join her daughter Anne to her nephew. Darcy has the good sense to reject his listless relative for the spirited if poor Liz Bennet.

Eliza de Feuillide had not one but two cousins who sought to marry her: James Austen and Henry Austen, two of Jane’s brothers. She chose the more ebullient Henry.

Eliza de Feuillide had not one but two cousins who sought to marry her: James Austen and Henry Austen, two of Jane’s brothers. She chose the more ebullient Henry.And of course Fanny and Edmund marry at the end of Mansfield Park. Whatever the church tradition, which still discouraged cousin marriage, no eyebrows shot up. Interestingly, the subject is raised before Fanny is ever invited into the family, when Mrs. Norris declares that Sir Thomas need not worry about a match between one of his sons and their cousin: “do not you know that, of all things upon earth, that is the least likely to happen, brought up as they would be, always together like brothers and sisters? It is morally impossible. I never knew an instance of it.”

By the novel’s conclusion, many years later, Sir Thomas gives not a thought to the match being between cousins, recognizing only Fanny’s many virtues.

Austen makes a point of mentioning “married cousins” on the last page, but only in the context of their joy in a relationship “as secure as earthly happiness can be.” It’s as if the familiarity that came from cousinage—their growing up together in the same house—bode well for a companionable life. At the very least, in this family of affairs, divorce, elopements, and general scandal, Fanny’s moral worth transcends any consanguineous concerns.

Next time: A look at another form of consanguinity.

The post Marrying a Cousin appeared first on Austen Marriage.

April 20, 2017

Miss Austen—No Politician, She

In this, the 200th anniversary year of Jane Austen’s death, we learn that white supremacists are co-opting the English author in support of a racial dictatorship, shocked opponents are claiming that true readers are “rational, compassionate, liberal-minded people,” and conservatives are chiding Janeites for assuming that great literature can be written only by great liberals.

All these political takes on Austen, yet whenever someone describes her political views, they get them wrong, because they have no idea what hers actually were. As an individual and an artist, she kept her political mouth firmly shut. She had other—I would claim—more important things to write about.

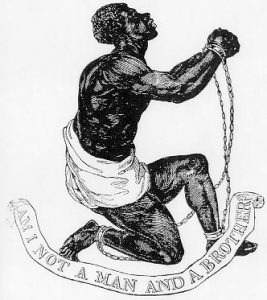

This silence can be confounding, for Austen lived in a time tumultuously like our own. Slavery—the “alt-right” issue of the day—was bitterly fought over. War, political corruption, and disparity in wealth had England on the brink of breakdown. Factory automation was destroying the middle class. Sound familiar?

Yet, when asked about her aunt’s political views, Caroline Austen, who wrote a memoir of the author, said: “In vain do I try to recall any word or expression of Aunt Jane’s that had reference to public events—Some bias of course she must have had—but I can only guess to which quarter it inclined.”

As today, the politics of 1800-1820 had many “quarters.” Radical Tories believed that God had put themselves and the King in charge; the poor deserved their lot because God had made them so. Radical Whigs, full of entrepreneurial zeal, believed that the poor deserved to starve because they were too lazy or incompetent to rise from their rags.

In between was a shifting coalition of moderate Tories, who felt a responsibility to those beneath them, and moderate Whigs, who sought to spread the political and social wealth—mostly to themselves, the rising business and technical class.

Lower-case “republicanism”—power to the people by putting them in charge, rather than an anointed king—drew the same reaction among conservatives then as “socialism” does today—the fear of the leveling of society (and power). A few desperate citizens pushed for revolt out of despair at the lack of economic and political justice.

Many of the issues are woven into the fabric of Austen’s work, but none plays out in the foreground. Thus, people take a slice here and there to justify their own political stances. Sheryl Craig, in her book Jane Austen and the State of the Nation, goes so far as to conclude that Austen’s novels are “carefully constructed texts … about political economics. The love stories came later.” Despite much great information in her work, Craig’s conclusion strikes me as exactly wrong.

A few feminist scholars were also described as “startled” to discover that a Wikipedia entry on Austen claimed she supported traditional marriage. Sorry, but she did. Every woman in her novels outside of traditional marriage, unless she started out rich, ends up impoverished, disgraced, or dead. The women in traditional marriage end up happy—or make a conscious and occasionally odious tradeoff for its security (see Charlotte Lucas and Mr. Collins). What Austen insisted upon is that traditional marriage include love and respect.

Naval officers like Frank Austen needed patronage to move up in the navy; otherwise, an officer could languish for years. All but a wealthy oldest son faced an uncertain future.

The poet W. H. Auden wrote a ditty noting that her supposed love stories actually describe the “economic basis” of society. Four of her six novels open with a reference to wealth, and conversations regularly involve finance. But this “economic basis” develops not through political discourse but through her factual descriptions of life.

Naval officers like Jane’s brothers needed patronage to move up in the navy; otherwise, an officer could languish for years. All but a wealthy oldest son faced an uncertain future.

Naval officers like Jane’s brothers needed patronage to move up in the navy; otherwise, an officer could languish for years. All but a wealthy oldest son faced an uncertain future.Being dependent, women must be canny in their romantic choices (see what happens to Marianne and Lydia when they are not). The non-inheriting males must find a career (see all younger sons). The lower classes need patrons to move up (sailor William Price, along with Jane Austen’s sailor brothers).

One sees in these stories her liberal sympathies, but it is not a sympathy of class. While self-made naval heroes return from war to supplant the attenuated aristocracy in Persuasion, the author holds in equal esteem the dull but reliable Col. Brandon, the grouchy aristocrat Darcy, the energetic Mr. Knightley, the farmer Martin—anyone who shares the virtues of industry, intelligence, and generosity.

The telling issue of that era was the slave trade, which became illegal in 1807, when Austen was 31, in her maturity as an author. As I have discussed before, Edward Said and other scholars claim that she turns a blind eye, particularly in Mansfield Park, where the family’s money comes from slavery on a West Indies plantation. Paula Byrne and others, in contrast, claim that Fanny Price in Mansfield Park speaks “truth to power” about slavery.

As today, racial issues divided society. Economic and religious traditionalists supported slavery and evangelicals led the bitter fight to end it.

Austen’s admiration for the poet-abolitionist William Cowper and for Thomas Clarkson’s abolitionist book indicate her opposition to slavery. Despite a few anti-slavery winks, however, Mansfield Park does not prove

As today, racial issues divided society. Economic and religious traditionalists supported slavery and evangelicals led the bitter fight to end it.

As today, racial issues divided society. Economic and religious traditionalists supported slavery and evangelicals led the bitter fight to end it.these personal views. Apologists cite Fanny’s comment that, when she raises the issue of the slave trade with her family, she is met with “dead silence!” The inability of anyone to respond to her question demonstrates Fanny’s—Austen’s—moral rebuke.

Only it doesn’t.

Fanny explains the silence: Her cousins simply have no interest in their father’s business, and Fanny does not wish to “set myself off at their expense,” by showing any curiosity about his topics. Earlier, she makes similar, maddeningly oblique comments. She could mean that she’s interested in the plantation reforms that were beginning to make slavery somewhat less horrific. We don’t know. Slavery adds a subtle metaphor about Fanny’s own lowly status, but Austen is too talented to turn her most complex novel into a political tract.

In attitude, Austen was a moderate Tory—the equivalent of a moderate Republican. Austen never challenged the existing order. Like the abolitionist William Wilberforce, she wanted to reform it—not abolish it. She believed in merit as the economic salvation for herself and her brothers. She was a proto-feminist in the sense that she was a pragmatist. Dependent on the men in her family for most of her life, she needed to be able to support, as well as express, herself. That ability became critical when her brother Henry’s bank collapsed, taking much of the family’s wealth with it. (Most of Jane’s funds were safely deposited in Navy Fives–stock paying five percent.)

Practical economic considerations fill her books, but to read the novels as political commentary is to miss the point. Austen creates a rich, original world in which complex, believable human beings interact at their best and worst.

Any political lessons flow from the way human characteristics manifest themselves at all levels in the real world. Life experience, not ideology, dictates any political take-aways from her plots. She demonstrates that women should be able to accept relationships on their own terms and to provide for themselves as their needs require.

In the 200th commemoration of her death, it is disquieting that these lessons of a woman’s right to basic self-determination remain too often unheeded—even disputed.

The post Miss Austen—No Politician, She appeared first on Austen Marriage.

March 22, 2017

Rules of the Road for Regency Language

Recently, some writers online were discussing language, particularly the use of language for an historical period such as the Regency age. I was traveling and unable to jump into the discussion, but the comments set me to reflect about my approach—which I had considered for quite a while as I began my historical fiction based on Jane Austen’s life.

As for general language, I take the actor’s approach when preparing to play an historical character: don’t imitate the person, inhabit the person. Learn all you can, absorb the way the individual thinks, feels, and acts, then speak naturally. The voice will come to you. Afterward, with a period piece, check for anachronisms. It’s not unusual for me to check five or six words a page. Trouble is, some old English words sound new, and some new English words sound old. “Ignition,” for example, sounds like a modern word: We relate it to car ignitions, “ignition, liftoff,” and so on. However, this word has been firing up our vocabulary since at least 1612.

The discussion covered a variety of bugaboos, mostly prohibitions that grammarians in the 19th Century tried to force on English to make it more like Latin, to rein in English’s sprawling structure to become more “proper.”

Among these rules, there’s no law against beginning a sentence with “And” or “But” or other conjunctions; however, that usage was not typical of traditional English and it does sound modern. Austen, though, uses an opening conjunction once in a while. Here’s an early example from “Mansfield Park,” when Fanny is trying to settle in: “And sitting down by her, he was at great pains to overcome her shame in being so surprised, and persuade her to speak openly.”

When I begin a sentence with a conjunction, it is usually to express a character’s thoughts, to distinguish a character who speaks abruptly, or to mark the less formal aspect of speech. Austen does the last in the same section in “Mansfield”: “And remember that, if you are ever so forward and clever yourselves, you should always be modest; for, much as you know already, there is a great deal more for you to learn.”

Austen commonly uses the “semicolon-and”; perhaps fifty for every “period-and.” Why should the former be seen as stately English, connecting two balanced phrases, and the latter as improper?

Split infinitives are another bogus issue. English is an accented language, and sometimes sentences split an infinitive for the rhythm: “To boldly go where no one has gone before” is a “Star Trek” phrase in almost perfect iambic. “To go boldly” or “Boldly to go” strike the English ear as wrong.

The phrase originated in a 1958 White House pamphlet on space travel; it was amended to “where no man has gone before” for the first “Star Trek” television series, then returned to “where no one has gone before” for the revival, “Star Trek: The Next Generation.” The phrase is also brought out in the split-infinitive debate. I’ve always wondered why the phrase wasn’t “to boldly go where none has gone before,” because that is perfect iambic pentameter. Perhaps the author thought it sounded too lyrical. Or perhaps “none” might have been contradicted by alien species, of which there are aplenty boldly going somewhere in the “Star Trek” saga.

There are other sentences in which the only correct sense requires the infinitive to be split. How else could you construct the following: “Prices are expected to more than double by next year.” The words that split the infinitive are nothing more than modifiers of the main verb; i.e., adverbs.

Split prepositions are also fine. Both Austen and Shakespeare used them. When challenged on his use of sentence-ending prepositions, Winston Churchill is reputed to have responded: “This is the kind of arrant pedantry up with which I will not put!” Though there is no definitive source of the remark that traces directly to the British Prime Minister, it sounds like the English bulldog—though he might have thrown in a “bloody” or two. Ending a sentence with a preposition is fine if it gives the sentence a punch. The same is true of keeping the preposition with its object where it technically belongs.

Among the other language issues that arose in the earlier lively discussion, I admit that it bugs me when people don’t know the difference between “farther” and “further,” but Jane Austen didn’t. Neither did Thomas Hardy, who wrote nearly a hundred years later. They both used “further” to mean distance. “Further” has always had the broader sense, but it’s a relatively recent development to separate the two so that “farther” means only “distance” and “further” means everything else. A nice distinction, but new.

Having been a copy editor, I learned and enforced all the rules. I was part of the priesthood. Over many years since, I have become more flexible. I do not believe technicalities should overcome the sense the writer is trying to convey. Some technically correct solutions are so cumbersome they break the spell by taking the reader out of the story. Usually, the best solution is to rewrite the sentence entirely, but that sometimes creates other problems.

I have a good friend and fellow writer who was never very good with spelling and punctuation. He asked me one time if the technical stuff really mattered, since the writer must focus on content. I replied that the rules were part of our box of tools and after twenty or thirty years we should be able to use them. I noticed decided technical improvements in his work after that. These changes, in turn, led to crisper writing. Sharpening his tools paid off.

There are many good style guides, from the plain and simple “AP Style Book” to the dense and complex “Chicago Manual of Style.” Even when the rules seem unintelligible, you can usually find an example that matches the phrase you’re concerned about. E.B. White’s “Elements of Style” is another classic, more about elegant writing than technical style.

One of the problems for American writers with an English audience is the difference between English spelling and punctuation and American spelling and punctuation. Some of the differences, mostly in spelling, evolved over time (“colour” = “color”, “encyclopaedia” = “encyclopedia”). A few developed independently (automobile “boot” = automobile “trunk”).

The main differences, however, happened abruptly and deliberately. Have you ever wondered why American punctuation is the inverse of English? American usage begins with a double quotation mark, and any interior quote is a single quotation mark: “Jones said angrily, ‘I hate quotes within quotes!’ ” English usage is the opposite: ‘Jones said angrily, “I hate quotes within quotes!” ’ Another difference is that in English usage, a noun that has a plural sense takes a plural referent: “The government/they.” In American usage, the same word has a singular sense: “The government/it.”

The reason is purely arbitrary. After the Revolutionary War, American printers wanted protection from the more established and cost-efficient British publishers. In a patriotic and protectionist fervor, Americans established a style just different enough to keep British printers from winning U.S. print contracts. It was the literary equivalent of driving on the other side of the road.

(Originally, most nations used the left side of the road in order to have the (right-handed) sword hand in a protective position against people coming the other way. The U.S. switch to the right side related to Napoleon’s preference for the right, which shifted the continent in that direction, and to the larger freight wagons over here in the U.S., which favored a rider on the left rear horse. This person would have a whip in his right hand for the horses and would want to see oncoming traffic on his left, putting his wagon on the right.)

Back to language. In some cases, the arbitrariness of the grammatical rule frustrates sense.

Consider a mixed group of men and women asked a question, and no one knows the answer. Which should it be:

“Everyone shook his head in confusion.” {grammatically correct but leaves out women}

“Everyone shook her head in confusion.” {grammatically correct but leaves out men}

“Everyone shook their heads in confusion.” {grammatically incorrect but correctly inclusive}

Most “singular/he” constructions can be avoided by changing the noun to plural, something like “people/they.” This is one example of trying to write around the problem. Most grammarians say it is fine to use the “everyone/they” construction in informal usage, but not in formal usage. I would normally use “everyone/he” or “everyone/she” in nonfiction, depending on sense. Nonfiction wants to be rigorous. In the above example, I would use “everyone/they” in fiction. Why? Because in fiction, there’s a different kind of rigor, which is maintaining the spell of the scene. There is no good substitute for the word “everyone” in English. Try recasting the above sentence to “people” and you’ll see what I mean: “People shook their heads in confusion.” What people? Everyone!

Also, rewriting the section might create more awkwardness than it solves; and being the way most of us speak, “everyone/they” is far less intrusive to a reader who, you hope, is caught up in your story. If the only one who objects is a grammar freak, I’m OK with that. I know I would have tried every workaround beforehand.

There’s only one unbreakable grammatical rule: You can’t break a rule unless you fully understand it, know why it exists, and have a good reason to break it.

As an American, I use U.S. spelling and punctuation. I know the obvious differences between U.S. and UK style, but a UK publisher will be far more capable than I of properly dealing with the nuances. English and American readers buy the opposite editions all the time, and neither has any trouble reading the other’s punctuation and spelling style. The best thing is to be proper and consistent with whichever you use.

When writing from an English point of view, however, I avoid Americanisms. In writing about Austen, I have readers versed in both the Regency period and UK English review my work before I publish. I have been corrected in the American use of “fall” for “autumn,” “creek” for “brook,” and a few other such provincialisms. I was embarrassed to learn from an English friend that I used the American “momma” instead of the English “mama” near the end of Volume II of “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen,” my novel on Austen’s life, after having used the correct form earlier. This was a late addition and suffered from the lack of vetting.

A few times, my intrepid early readers caught a few words they thought were anachronisms but were not. One flagged “administratrix” as modern technical, but it goes back to circa 1561. I follow a rule similar to that of Regina Jeffers, another Austen blogger, who will use a word if its documented use comes within ten or twenty years of the time she writes about. The rationale is that a word must have been circulating in speech for a while before it became part of the written lexicon. In my Austen trilogy, the character Ashton Dennis uses the word “stomp” in late 1802. The first known written use of the word was 1803. I decided that Ashton must have been the one to coin it.

The post Rules of the Road for Regency Language appeared first on Austen Marriage.