Collins Hemingway's Blog, page 4

July 12, 2018

Putting the History in Historical Fiction

Ernest Hemingway once said: “If a writer knows enough about what he is writing about, he may omit things that he knows. … The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

This non-obvious lesson is one I learned and relearned in the four and a half years it took to write The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, a literary trilogy based on the author’s life. Along the way, I jotted down a similar set of guides regarding the use of history in historical fiction: 1) Start with as much actual history as you can. 2) Use as few of the details of that history as possible. 3) Make the history serve the story, not the other way around.

(I would call these three items “Hemingway’s Rules” except for the possible confusion with the big guy and his iceberg.)

Rule 1 and 2 might seem to cancel out, but they actually reinforce. Rule 1 is to know the history so well that you understand the personal (biography) and the social (history) enough to make both real. This gives you the ability to internalize the material and write about it thoroughly. The information will flow naturally, not as if you’re cribbing lines from another source. We’ve all read historical fiction that is set in a certain time, yet all the author does is wave his or her hand toward a few well-known facts of the era and then writes a story that could be set anywhere or any time. This is not artistic freedom; this is artistic indolence. When asked once how he wrote great free verse, the poet Richard Wright replied that it was because he had trained for years on sonnets. Freedom comes from mastering the subject, not avoiding it.

Rule 2 is important, however, because once you know something really well, your instinct is to tell the world all about it. This is usually not good in fiction. We’ve all also read the historical fiction in which the story suddenly stops for a two-paragraph or two-page digression on an historical sidebar. This can be interesting, but very few writers have the literary skills to pull off this trick more than once per novel. What Hemingway (the other one) meant is: Using your deep well of knowledge, put down the most salient facts—and only those—that are necessary to make the setting believable and the scene function. Anything beyond that will slow down the story and eventually bury your characters in the rubble of times gone by.

Rule 3 embraces the other two. Don’t let historical events drag your story along. Have the history illuminate and support your story. Diana Gabaldon sets the Outlander series in the Scottish rebellion against England of the 1740s. Her first several volumes do a terrific job of weaving her deeply moving love story in and out of the era’s political and military events. This tight weave of danger increases the drama, putting more at stake in the lives of Claire and Jamie. In the later volumes, the connection to the bigger world becomes less integral, and the stories lose some of their punch. The plots become more contrived as the author subconsciously shifts from developing the relationship to tying together historical episodes. You can’t really dislike anything that Claire and Jamie do, but at times it feels as though Gabaldon is repeating her formula in a new setting rather than coming up with compelling external events to continue to drive their relationship forward.

This is likely a minority view, as the huge popularity of the series shows. My wife, who finds reading straight history boring, loves learning about the West Indies, North Carolina, and the American Revolution through the lives of our Outlanders. But that’s the point: Later on, the main characters are there to relate the history more than their own lives. Even Georgette Heyer, who did more to create the Regency romance genre than Jane Austen, sometimes has her characters on the sideline, exchanging bright repartee while watching the parade of history march by. My view is that the history should remain the supporting platform for the characters and their relationship. I think we fell in love with Claire and Jamie in the early going and now are just along for the ride.

If there’s any doubt, read any of the last two or three volumes in the series and then return to the original The Outlander. You’ll see what I mean. The later books continue with the buckles being swashed and the Frasers’ trademark enthusiasm for sex. But the inventive personal story line, the slow entanglement of their feelings, and the brilliant contradictions of the Frank character(s) are what make the first volume psychologically and emotionally compelling. And one of the most remarkable books I’ve ever read.

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Putting the History in Historical Fiction appeared first on Austen Marriage.

June 14, 2018

Seeing Fanny Price Through Modern Eyes

Until this week, I had seen all of the major film adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels—the theater releases, the BBC series, etc.—except one. I have now completed the sweep by finally watching Patricia Rozema’s 1999 version of Mansfield Park.

I missed the movie when it came out. After reading a few reviews and coming across additional commentary over the years, I wasn’t sure I wanted to see it. The reason is that Rozema takes the slavery issues in the background of MP and puts them in the foreground. The way she does this changes the book fundamentally.

I felt preemptive annoyance that people who saw the movie but never read the book would be confused about what Austen had written and about what her positions on slavery actually were. (In my view, Austen’s views are not at all clear.)

Rozema justifies the changes by saying that there’s a difference between a book and a film and by insisting that as an artist she has the right to provide a “fresh view.” She adds: “Whenever you turn a novel into a movie, you’re changing form. … I felt fairly free to make changes as long as I felt I could face Austen if I met her.”

Rozema justifies the changes by saying that there’s a difference between a book and a film and by insisting that as an artist she has the right to provide a “fresh view.” She adds: “Whenever you turn a novel into a movie, you’re changing form. … I felt fairly free to make changes as long as I felt I could face Austen if I met her.”

She’s correct that some things in the novel form cannot be produced in the film form. A book can convey a character’s thoughts. A movie has to have the character express those thoughts in dialogue or demonstrate them through action. A two-hour movie can usually show only a third to a fourth of the content of a novel, so subplots have to be condensed or dropped or reduced to a passing moment on screen. Characters must be cut or combined. The Grant family disappear from the film, which is no big loss. But Rozema drops William Price, Fanny’s brother, and his naval service from the screen, which is a big loss and which creates complications described below.

When I finally saw the movie on DVD, I was not as bothered by the slavery issues as I thought I would have been. There was one immediate howler, though. Young Fanny, the poor cousin being adopted by her rich relatives, sees a slave ship in an English bay. A slave ship wouldn’t be within a thousand miles of England. That cargo passed between Africa and America. In England, those ships would have been delivering sugar, rum, and rice purchased in America with the profits from the slave sales.

But most of the slave references did bring out points visually in the only way possible. There’s one scene when Edmund and Fanny are riding and the topic of abolition comes up. Fanny says abolition is a good thing. Edmund reminds her that abolition will hurt the Bertram family finances. Fanny reacts as if recognizing this dependency for the first time. Strangely, the one direct reference to the slave trade in the novel—in a scene that would have made for great theater—is absent.

One possible exception to the slavery motif is the treatment of Sir Thomas. One depiction of his role in slavery left him irredeemable, which was not Austen’s intent nor, I think, Rozema’s.

I liked several other changes, too. Rozema heightens the sexuality with several brief but intense PG-rated interactions (along with one R-rated moment). She also converts Fanny’s interior life into Jane Austen’s, by having Fanny, as she matures from ten to eighteen years old, write and recite Austen’s juvenilia. That’s great fun.

What I didn’t like is that Rozema changed the emotional dynamics among the major players. In the novel, for instance, Edmund is gobsmacked by the beautiful, worldly Mary Crawford. She toys with him for fear that he will settle for a dull, country, clergyman’s life counter to her love of the big city. Edmund returns to Fanny at the end of the novel only because Mary’s attitudes on love and sex are revealed to be too scandalous. In the movie, Edmund is wary of Mary. She works her wiles on him and wins him over only after Fanny is sent back to Portsmouth by her uncle as punishment for not being willing to marry Henry Crawford.

Similarly, the dynamics change between Fanny and Henry. In the book, his attempts to seduce her cause the reverse—he falls for Fanny. As a result, he arranges for her brother, William Price, to be promoted to lieutenant through the auspices of his uncle, an admiral. This is a huge deal. Otherwise, William could have remained a midshipman indefinitely and his hopes for a career ruined. Most young ladies would have married Crawford for that act alone. (Cassandra, Jane’s sister, said she wanted Fanny to marry him instead of Edmund, probably for that very reason.)

With William gone from the movie, there’s no way for Henry to show his feelings for Fanny in a bold or honorable way. All we see is his continuing charm offensive against her until, when she thinks Edmund is committed to Mary, she finally gives in. Here, Rozema adds another element from Jane’s own life. She has Fanny accept his proposal, then reverse her acceptance overnight. This happened with Jane in December 1802, supposedly with Harris Bigg-Wither, though the veracity of the story is uncertain.

Fanny’s actions send Henry off in a rage, which he acts upon by seducing Fanny’s married cousin, Maria. These actions conform to the novel’s plotline, but the motivations are substantially different. In the novel, Henry’s seduction comes as the result of boredom, or an unwillingness to wait for Fanny, or plain self-indulgence. (Though Fanny has also made it clear she plans never to marry him.) In the film, Fanny’s actions are so hurtful that they justify some kind of retaliation by Henry—though not in the extreme way he does.

The characters are well played. Frances O’Connor is terrific as Fanny. Rozema makes her stronger and more independent than Austen’s Fanny, but O’Connor also is able to imbue her Fanny with morality and dignity without self-righteousness. She still has a tendency to keep her thoughts to herself, but the audience can read them on her face.

Johnny Lee Miller makes Edmund—a character who strikes me as undeserving of the heroine in the novel—an interesting, intelligent man. (He’s played a major role in the two Trainspotting movies and is best known to U.S. audiences for playing Sherlock Holmes on TV.) Alessandro Nivola has only one note to play as Henry Crawford but does it well.

In the movie, Henry Crawford has a reason to strike back at Fanny Price, unlike the novel.

In the movie, Henry Crawford has a reason to strike back at Fanny Price, unlike the novel.Lindsay Duncan plays both the quiet Lady Bertram and her impoverished, overwhelmed sister, Mrs. Price, Fanny’s mother. I did not realize it was the same actress until reading the credits!

Last and least—in an amusing way—is Hugh Bonneville as Mr. Rushworth. It was a hoot to see Bonneville, who became a star a decade later as the solid, respectable Lord Grantham in Downton Abbey, playing MP’s buffoon with a scrumptiously awful haircut.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Seeing Fanny Price Through Modern Eyes appeared first on Austen Marriage.

May 17, 2018

Jane Austen’s Chawton Sanctuary

Jane Austen was a religious woman but not a religious writer. The good prevail in her works, but unlike one of her favorite authors, Samuel Richardson, or one of her contemporaries, Maria Edgeworth, the outcome is the result of the characters’ decisions and actions. It is not the result of the author’s desire to preach a lesson. The people with failings—including a clergyman here and there—suffer (or not) according to their earned deserts.

The church she attended as she pursued her writing full time had a strong family connection. This was St. Nicholas Church in Chawton, a short walk from the cottage where she lived the last eight years of her life. In addition to her regular attendance, she would frequently pass the church, for she would turn left at the building to make her way up the hill to the Great House where her older brother Edward lived and other family members regularly stayed.

Edward, the adopted heir of the Knight family, provided the living (salary and home) for the minister. At one time, Austen brother Henry

Jane Austen and her family walked a short distance from their cottage to attend church at St. Nicholas

Jane Austen and her family walked a short distance from their cottage to attend church at St. Nicholaswas the pastor here on an interim basis until one of Edward’s sons, Charles, succeeded to the living. The rectory was across the road from the church. As the wealthy landowner, Edward also provided most of the funds for the church’s upkeep.

Because the village was on the pilgrims’ route from Winchester to Canterbury, there’s a good chance that a church existed back in Norman times. The first records indicate a church at “Chautone” was built between 1225 and 1250, and one appears as part of the Diocese of Winchester in 1270.

The Knights acquired the manor in 1578; the church remained part of the estate until the family transferred it to the Bishop of Winchester in 1953, when Chawton and Farringdon, a village just to the south, combined under a single rector. The rectory was sold to benefit the parish, and the rector lived in Farringdon. In 2004, this parish consolidated with nine other local parishes.

The Chawton parish registers began in 1596, but the first wedding was not recorded until 1620, a “curious gap,” according to a church history. Sometime in the 18th Century the building acquired a square belfry and shingled spire. Jane would not have known most of the current building, because Edward and his son Charles reconstructed it in 1838, twenty-one years after her death. Over the next thirty years, Charles made additional changes. Tragically, in 1871 the church caught fire on the morning the church was scheduled to reopen after the latest alterations. The volunteer fire brigade finally put out the flames, but not before much of the building’s contents were damaged or destroyed. The losses included the pulpit, the clock, the organ, ancient memorial tablets, and stained-glass windows.

Many of the cottages in Chawton are the same as when Jane Austen lived there beginning in 1809, but the church looks much different as the result of later remodeling by her brother as well as a major fire

Many of the cottages in Chawton are the same as when Jane Austen lived there beginning in 1809, but the church looks much different as the result of later remodeling by her brother as well as a major fireThe church was immediately rebuilt. In 1883, four new bells were added to two ancient ones. The Friends of Chawton Church, founded in 2000, with help from the Jane Austen Society and contributions from villagers, installed new bells in 2009 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Jane and the other Austen women moving to Chawton—a quiet little village little changed since her residence there. Even the population is about the same–350, and many of today’s village buildings existed then. One can easily imagine the ladies—Jane, her sister Cassandra, her mother, and their dear friend Martha Lloyd—walking the short distance to the church and Jane’s lovely voice joining with the others in song to celebrate her deep Anglican beliefs.

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Jane Austen’s Chawton Sanctuary appeared first on Austen Marriage.

April 19, 2018

Austen Sideroads Yield Interesting Journeys

Combing the internet for information on the life and times of Jane Austen sometimes leads to links in which the English author is mentioned in passing or as part of a broader story. More times than not, these side trips become worthwhile journeys of their own. Today we look at some of these online detours and where they take us.

Most Janeites assume that the revered Austen is already a saint. They will be pleased to know that one article suggests her canonization, one of five women authors so nominated. Familiar faces here—Jane Austen; Mary Wollstonecraft, the feminist firebrand of Austen’s day; and Mary Shelley, who as the author of Frankenstein became the first science-fiction writer (at the age of 21!). In addition to being Wollstonecraft’s daughter, Mary Shelley was also married to the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Other fascinating women of later periods are also put forth for beatification. Terrific reasons

A search for Jane Austen often yields connections with other authors or greater insight to women’s fiction overall or to women’s issues.

A search for Jane Austen often yields connections with other authors or greater insight to women’s fiction overall or to women’s issues.for them all. https://lithub.com/5-writers-who-should-be-feminist-saints/

Though women authors have proliferated in the modern era, a recent study involving more than 104,000 books turns up the unexpected finding that women were better represented in the Burney-Austen-Bronte period than they have been in most of the modern era. Researchers expected to see the number of female authors and prominent female characters increase in literature from 1780 to 2007, the period studied. Instead, “from the 19th century through the early 1960s we see a story of steady decline” in prominent female characters, the study found. This is likely the direct result of the percentage of titles by women authors dropping from about 50 percent in 1850 to about 25 percent in 1950.

The study speculates that one reason for the drop, which reversed around 1970, could be the “gentrification” of the novel. When novel-writing became a “high-status career,” it drew more male writers, displacing women, while women began to find other opportunities that took them away from fiction. Also, Kate Mosse, the historical novelist and founder of the Women’s Prize for Fiction, said that Victorian values, “the idea of the angel in the home,” tended to suppress women’s writing. Ironically, this meant that Ann Radcliffe, Jane Austen, and Mary Shelley had more opportunities than their successors. Mosse adds, “And then criticism becomes a … male discipline, and it’s therefore not surprising to me that women as writers lose their positions.” These words echo Anne Elliot’s complaint in Persuasion that women are characterized poorly in books because men have had “every advantage of us in telling their own story … ; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.”

The article has much more to say about gender differences in the way women and men are described in novels, physically and emotionally—what they say, how they act and react. It’s a great read. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/19/women-better-represented-in-victorian-novels-than-modern-finds-study

Country houses have been a part of English literature for hundreds of years, including the fictional Mansfield Park as well as the very real Great House at Chawton, where Austen likely worked from time to time in the library.

Country houses have been a part of English literature for hundreds of years, including the fictional Mansfield Park as well as the very real Great House at Chawton, where Austen likely worked from time to time in the library.Country houses play a prominent role in English literature. Everything from The Go-Between, Brideshead Revisited, The Remains of the Day, to of course our own Mansfield Park. The article authors appreciate Austen’s take because it is “so wonderfully not intoxicated with the grandeur and romance of its big house—makes you feel its convenience and its privilege, yes absolutely, but also its boredom, the dullness of the people living in it.” The blog is a lovely stroll about the grounds of books with these settings and the way in which these works are the same and how they differ. http://lithub.com/repositories-of-memory-on-the-country-house-novel/

Last but not least is the story of how a young man became a Jane Austen superfan. Hint: His mother was involved. The blog is actually a plug for the guy’s new book, but the essay itself (a book excerpt) is worth the time. Reading her juvenilia was his introduction to Jane. He describes her early writings as “hit jobs” against authors she liked and didn’t. He explores being “utterly drunk on letters”—and on a charming girl named Nathalie—as a prepubescent American boy abroad in England. This experience eventually transitions into a four-day summer conference billed as a “Jane Austen Summer Camp,” followed by trips to JASNA annual general meetings, where his mother’s prominence caused him problems. “Did I skip the dance rehearsals? Doze off during the lectures? There were phone calls on the subject.” I’ve not read the book, so I can’t say whether it continues to develop in this wonderful vein or is just the same story stretched out over 200 pages. The essay itself is a hoot. https://lithub.com/how-i-became-a-jane-austen-superfan/

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The Trilogy is also available in a single “boxed set” e-book.

The post Austen Sideroads Yield Interesting Journeys appeared first on Austen Marriage.

March 21, 2018

Foreign invasion of Bath? Quelle Horreur!

The lovely city of Bath, England, might be the most regular character in Jane Austen’s novels. Much romantic intrigue occurs there in Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. A clergyman finds a wife there in Emma. The bad boys in the other three novels head in that direction—one known to have seduced a young woman there and the others likely in town for lascivious diversions of their own.

So with all that’s going on in Bath, why doesn’t Austen tell us about the French invasion?

I’m not talking about the French attack threatened by Napoleon for much of Austen’s adult life—which included an abortive landing near Bristol, not far from Bath. I’m speaking of the invasion by the people chased from the country by La Terreur the decade before Boney took power. In doing research on Bath, I came across an article in a Somerset County historical publication that said waves of French émigrés came to Bath beginning with the Revolution in 1789.

At first, the good citizens of Bath welcomed the émigrés fleeing the French Revolution.

At first, the good citizens of Bath welcomed the émigrés fleeing the French Revolution.According to one report, Bath received as many as 25,000 French in 1791 alone! The number is hard to believe, as the total population of Bath was less than 40,000 in the late 1700s. Even if the number were half what was reported, that would have been a huge influx of foreigners. Many of the exiles were royalty and their retainers and followers; some were intellectuals. Everyone who wasn’t part of the French Revolution was fleeing for his or her life.

British authorities determined that the solidly Tory town was a good place for the French and that Bath’s leadership would quickly sniff out—and snuff out—any pro-Jacobin, pro-Republican sentiment that might slip in with the tide. The idea of a representative democracy back then was frightening to the political elite. They had only two examples to date: The United States and France, neither on good terms with the British and the latter descending into chaos.

The French found places to live in the city’s many lodging houses and spreading suburbs. For a resort town, Bath was relatively inexpensive. Various princesses, French clergy, and other royal dandies were feted. They became a cause celebré. Money was raised in support, even for the French clergy, though they were Catholic. One of Bath’s other charms is that it had a registered (legal) Catholic church at a time of great discrimination against the faith.

Formal outbreak of war against the Republican government in France in 1793 caused Bath’s building boom to collapse, leading to bankruptcies and two bank failures. This, and the general hardship of war, led to a souring of attitudes toward the visitors. Paranoia spread that the emigres were awaiting signals from Paris to rise up against their friendly hosts. With the passage of several Alien Acts in the 1790s, French exiles were examined by magistrates for seditious attitudes and had to register any weapons they had.

The French also created economic problems—welfare first (even the wealthy French began to run short of cash after a while)—then work, as they began to seek jobs. Painting, drawing, and music lessons were common pursuits, and fashion was a big thing. Every exile seemed to be teaching French. When a local committee sought to stimulate the sale of craft goods, businessmen rose up, afraid the project would favor the work of the Alien over the Native.

Visitors from all countries enjoyed tours of beautiful Sydney Gardens.

Visitors from all countries enjoyed tours of beautiful Sydney Gardens.On the opposite side, the availability of French silver coins aided the economy at a time when British silver was in short supply. The government was using paper money to pay for the war, but everyone preferred what Jane Austen called a bit of pewter.

The gouty Louis XVIII even came to Bath in 1813 for the waters with his French court in exile. He stayed until Napoleon was overthrown the next year. With the restoration of the monarchy, many French returned home. But the émigré demographics skewed to the older, and many had died in the twenty-plus years. Several elderly French priests lived on in Bath until the 1830s; the rest of the exiles were absorbed into the population or moved elsewhere, most likely London.

Somehow, though, Bath seems to have resisted any permanent French influence. Not only is this influx of foreigners not mentioned in any other books and articles I’ve read about Bath, but this is also a topic not mentioned by Austen. Perhaps it’s because she’s quintessentially English, but you think she might have made passing references to at least a few French sights and sounds—French advertisements, French dress, or French accents. At a ball in 1789, Bath resident Elizabeth Sheridan reported that “the sound of French prevail’d [even] over the Irish accent which reigns pretty generally at Bath.”

The only reference to anything French in Austen’s Bath novels comes in Northanger Abbey, but it’s not related to French emigres overflowing the streets. Catherine makes three references to the south of France as being “fruitful in horrors”—a connection to her Gothic novels, particularly Mysteries of Udolpho. She also relates Beechen Cliff near Bath with the vistas of the same part of France.

Finally, when Catherine joins the Tilney family to travel the thirty miles from Bath to their abbey home, the group must wait two hours at Petty France, about halfway there, for a change of horses. This must be a coach inn where one can “eat without being hungry, and loiter about without anything to

A future famous author lived here, with French exiles close by.

A future famous author lived here, with French exiles close by.see.” Perhaps it was named for an enclave of local French. Or did some enterprising French royalty establish the coach stop? (Though one expects they would have spelled it Petit France rather than Petty.)

What say ye? Are there French subtexts in the Bath novels—or anywhere in Austen’s mature works—that I’ve missed? Yes, there’s the vague connection of Frank Churchill to an undefined French lack of reliability in Emma, but is there anything more substantive? Does Austen plant subtle French flags for sharp elves to see?

The post Foreign invasion of Bath? Quelle Horreur! appeared first on Austen Marriage.

February 21, 2018

Retracing Themes in Austen’s Life and Works

My blogs over the last two years have covered a wide expanse of territory: Jane Austen’s fiction; her speech patterns; her looks; her romantic life, both real and possible; the close biological relationships of people involved in courtships; the effect of the war on her life and that of her family; taxes; and even the jewelry she wore.

Over that time, I have come upon additional information about some of these topics. This post follows up with material that expands on what I originally wrote, providing additional background and depth on repeating themes and ideas in Austen’s life and works.

In honor of tax day in America (April 15), I summarized the many taxes that individuals paid back then in England, much of the funding supporting the war with France. One of the highest duties was paid on carriages, which were the province of the rich. Jane Austen’s cousin and sister-in-law, Eliza, who enjoyed the high life whenever she could, complained about such levies on luxury items. “New taxes will drive me out of London and make me give up my carriage,” she griped—though she continued to live in grand style in the expensive capital for most of her life.

I pointed out that Mr. Bennet’s horses in Pride and Prejudice would not have been taxed, because they were primarily farm horses. Jane Austen herself makes a similar point through an indirect reference in real life. In a letter of 24 January 1813, she speaks of riding with Mr. and Mrs. Clement in “their Tax-cart,” so named because this open work cart had a lower tax rate than a fancy carriage. Most of the taxes were paid by the rich, but a few, including taxes on spirits, hats—and carts—were paid by the poor and middle classes.

In one of my earliest blogs, I wrote of a turquoise ring Jane owned. It might have come from the meager inheritance the family received through the Stoneleigh inheritance, a story too complicated to repeat here. The point was that the stone was odontolite, a polished blue fossil that connected Jane to Lyme Regis’s Mary Anning, in 1804 a child fossil hunter. Mary’s family dug out fossils from the cliffs at Lyme Regis and sold them in the local market when Jane lived there. It’s even possible that this is where Jane bought her ring. As a pioneering paleontologist, Anning became the most famous woman scientist of her day—though like most women, underpaid and underappreciated.

After Jane’s death, her sister Cass gave the ring as a wedding present to Eleanor, the second wife of brother Henry (Eliza, Henry’s first wife, had died a few years earlier). Eleanor must have been very beloved for Cass to give her this precious keepsake. The ring came down through the family, was purchased by the Jane Austen Memorial Trust, and can now be seen at the Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton, Hampshire.

As I described just last month, all the able-bodied men in Jane Austen’s family helped England’s military effort in some way, but only the women suffered direct casualties: Cassandra, who lost her fiancé, Tom Fowle, to disease on a military expedition; and Elizabeth, Jane’s sister-in-law, who lost her youngest brother in a naval battle.

Still other casualties, it turned out, haunted the women: Tom Fowle’s brother, a medic, died in Egypt in 1801, a few years after Tom. (A few years after that, another Tom Fowle, a nephew of Cass’s fiancé, moved up through the ranks by serving successively on the ships of Frank and Charles, Jane’s sailor brothers.) Finally, Lady Burrell, a dear friend of Eliza, lost her son, a captain of the dragoons, in an abortive British invasion of Argentina. Often in the background of her novels, the war weighed heavily on the country in actual life.

Two of my blogs touched upon marriages involving consanguinity—close blood ties. Austen’s work and life were replete with marriages involving first cousins and a couple that involved a psychological closeness akin to siblings. At that time, marriage between first cousins in England was technically forbidden. The practice is now legal in the United Kingdom and is fairly common around the world, but remains problematic in the U.S. Today, cousin marriage is illegal in about half the states—including the two, Oregon and Arkansas, where I’ve lived most of my life. In five states, cousin marriage is a criminal offense! An advice columnist even received a query in 2017 from a foreign-born woman whose American friends were concerned about her marrying her third cousin (their closest connection being great-grandparents). American law is based on largely debunked concerns of damaged offspring.

In Regency society, cousins married all the time. The practice was common among the wealthy to keep family fortunes intact. In the Austen world, the reason must have been love, for no fortunes were ever melded. The most visible, of course, was Henry’s marriage to Eliza, but Frank’s son and Charles’s daughter also married. In addition to the several I mentioned, I found at least one more: Henry, a son of Jane’s brother Edward, married another cousin, Sophie Cage. Others may lurk in the interconnected tangles of families close to the Austens.

The Mansfield Park marriage of Edmund Bertram and Fanny Price was the biggie in Austen’s novels. A reader, Cinthia, pointed out that I had overlooked one in Persuasion, between Henrietta Musgrove and Charles Hayter, whose mothers are sisters.

Several commentators, most recently E.J. Clery, in her 2017 book Jane Austen: The Banker’s Sister (pp. 208-211), have noticed how close the cousins orbit toward the psychological sphere of brother and sister and how that closeness sometimes leads to amorous rather than sibling affection. When he takes Fanny in, Sir Thomas Bertram worries about her becoming too close with his sons, but Mrs. Norris, the meddling aunt in MP, dismisses his concerns with her usual lack of judgment, saying nothing improper could come of Fanny being “bred up” as a sister to the Bertram boys.

Edmund and Fanny’s first major encounter involves what Clery calls a “triangulation” of sibling affection involving William Price, Fanny’s brother, now in the Navy. Edmund comes upon Fanny weeping because William has asked her to write but she has no paper. Edmund not only provides the paper but also slips in a half-guinea coin for the young man. “With this small transferal of wealth,” Clery says, Fanny becomes “devoted to Edmund”—a sisterly affection that becomes stronger and more romantic over the years.

Though at times a modern reader might squirm at such thoughts, Clery cites the critic Celia Easton as saying that in Austen, “sibling-style love lays a good foundation for committed relationships.” Austen herself sees nothing unnatural about the closeness of cousins, encouraging one of her nieces to develop a relationship with one of hers. “I like first cousins to be first cousins, & interested about each other,” she says in a letter to Anna Austen Lefroy, 29 Nov 1814. “They are but one remove from Br & Sr.”

Another couple “but one removed” from brother and sister are Emma and Mr. Knightly (image by headline, from 1995 movie), who struggle with emerging romantic feelings after twenty years of sibling-style affection. They begin with a dance, which as Austen says elsewhere, is “a certain step towards failing in Love.” Emma says that they are “not so much like brother and sister as to make it all improper,” to which Mr. Knightly exclaims, “No, indeed!”

—

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, which traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions, is now complete and available from Amazon and Jane Austen Books.

The post Retracing Themes in Austen’s Life and Works appeared first on Austen Marriage.

January 25, 2018

Jane Austen and the Casualties of War

Jane Austen had two brothers who served in the navy, Frank and Charles, and two who served in the militia, Edward and Henry. Father George Austen and brother James, as clergymen, were discouraged from bearing arms but recruited soldiers and militiamen from the local population.

It was the women in Jane’s close orbit, however, who suffered most directly from the horrors of war itself.

Jane’s sister, Cassandra, lost her fiancé, Tom Fowle, who went on a military expedition to the West Indies as the chaplain of his cousin’s ship. There, Tom died of yellow fever–as did half of all the British serving there. The cousin later said that, if he had known Tom was engaged, he would not have taken him. Tom’s generous £1,000 financial legacy to Cassandra, yielding about £50 annually, proved providential when the family income plummeted after the elder Mr. Austen died.

The other woman suffering a casualty from the war was Elizabeth, the wife of Jane’s wealthy brother Edward. In August 1807, Edward and Elizabeth learned that Elizabeth’s youngest brother, George, had been wounded in naval action, taken prisoner and brought ashore, and died.

Fanny Austen, Jane’s niece, would have been a young teenager when she wrote in her diary about the death in a naval battle of George Bridges, her uncle on the other side of the family.

Fanny Austen, Jane’s niece, would have been a young teenager when she wrote in her diary about the death in a naval battle of George Bridges, her uncle on the other side of the family.The only surviving reference to the death of “poor Uncle George” comes on August 27, 1807, in the diary of Fanny Austen, Edward and Elizabeth’s oldest child and Jane Austen’s favorite niece. The death of the twenty-three-year-old lieutenant was confirmed about a week later.

Only nine years older than Fanny, George likely was more of a brother to Fanny and Edward’s other eldest children than an uncle. Though he came from the wealthy Bridges family, George had no wealth of his own. He lacked the inheritance of the oldest son or the clerical calling of the other three surviving sons. Like the two youngest Austen males, he sought to make a career of the Royal Navy. In fact, being five years younger than Charles, he might well have been emulating their careers. Both families came and went at Edward’s Godmersham estate; it’s likely that young George might have met at least Frank, who honeymooned there in 1806 while Charles spent 1805-1811 on duty in North America.

Jane’s reaction is unknown—the year 1807 is nearly blank insofar as her letters go. But the equivalence of the two situations—two women whose favorite young brother faced the fury of battle—must have struck Jane deeply.

Still more shocking, George was mortally wounded on Frank’s old ship, the Canopus (above, by headline), which he had captained to victory at San Domingo the previous year. The Austens lacked the connections to be given command of the newest ships, and Frank had complained about how slow and clumsy the old vessel was. Jane must have shuddered to realize that Frank himself had walked the same quarterdeck—it could have easily been his blood spilled on the oaken planks as George’s.

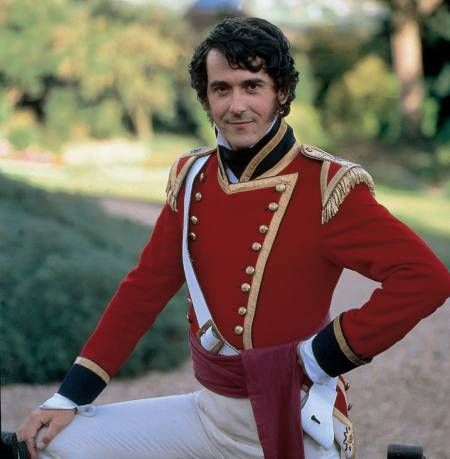

George Wickham’s scarlet uniform from the militia serves as a lure for young women in “Pride and Prejudice”–a major subplot.

George Wickham’s scarlet uniform from the militia serves as a lure for young women in “Pride and Prejudice”–a major subplot.The war with France ran most of Austen’s adult life, and she wove elements of it into her works. The bad-boy militia is an important subplot in “Pride and Prejudice”; the courage and open-heartedness of young naval officer William Price provides a counterpoint to the several dubious male characters in “Mansfield Park”; and the return of the conquering navy is the heart of “Persuasion.”

In addition to serving as a meaningful backdrop in these Jane Austen novels, the war also comes up subtly elsewhere as a plot device or character marker. In “Emma,” Jane Fairfax needs to be an orphan, so her father has been killed in action. In “Sense and Sensibility,” Colonel Brandon’s earlier service in India illustrates his sturdy character and reliability, while in “Northanger Abbey” Frederick Tilney’s captaincy in the dragoons serves as a flag for his hell-bent-for-leather recklessness.

Nowhere, however, does the war itself truly come to the forefront or serve as a major part of the storyline. Even in the most military book, “Persuasion,” the theme is not the horrors of war but the contrast after the war between self-made naval heroes entering society and the lazy, self-indulgent gentry who will be displaced by them.

Austen kept the war at a distance in her novels, but not because she was uninterested or unaware of the military battles raging. Instead, as the losses to Cass and Elizabeth show, its dangers struck far too close to home.

The post Jane Austen and the Casualties of War appeared first on Austen Marriage.

December 15, 2017

Jane Austen’s Birthday, Season of Giving, and Chawton House Library

We’re coming to the end of a year commemorating the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death, but I prefer to celebrate the great author’s birth. December 16, 2017, marks her 242nd birthday. This day of celebration falls in the middle of the Christmas season, a time of joy and giving.

For this reason, I’d like ask readers to consider a small holiday gift that celebrates not only Austen but also a dozen other early women writers. I’m speaking of donating to the Chawton House Library (photo by headline), which requires a major infusion of cash if it is to survive and prosper.

The Great House, as it was known when Jane Austen’s brother owned it and it served as a gathering place for the Austen clan. The library was founded by American entrepreneur and philanthropist Sandy Lerner in 1993 to restore the neglected literary heritage of women writers. She saved the property from conversion to a golf course, oversaw the rehabilitation of a house in serious disrepair, and stocked the library with her own extraordinary collection of works by early women writers. She made the collection available to scholars and the general public.

After more than two decades of personal support, in which she provided roughly 65 percent of the library’s operating costs, it was time for Lerner to step back and for the Austen community and lovers of literature in general to step in. The result is that Chawton House Library is in the middle of a major fundraising campaign, both to protect and improve the house and grounds and to expand the collections and resources.

People are already rallying to the cause. The Garfield Weston Foundation, one of the largest charitable organizations in the world, has contributed £100,000. Emma Thompson, who wrote the screenplay and portrayed Elinor in the 1995 movie “Sense and Sensibility”—launching today’s Austen renaissance—and her husband, Greg Wise, who played Willoughby, have announced their support.

But as with most projects of this nature, the rare major donations need to be supported by numerous small donations. Janeites, in particular, should rally to the cause. The library has several specific ways to give, including #BrickbyBrick, in which you buy a brick, or you can adopt a book. Among the books available to be adopted are the letters and works of Lady Montagu, “Evelina” by Fanny Burney, and “Pride by Prejudice,” by “A Lady.”

Suggested donations begin at £25 pounds ($40), but they’ll accept less.

Citizens of the United Kingdom can donate to the library directly. North Americans can contribute through the North American Friends of Chawton House Library, a nonprofit that will enable you to take a tax deduction.

North Americans, who have donated generously to other restoration projects involving Austen and her era (including English churches), can help again—there are more of us! The Eastern Pennsylvania region of the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA

The stables of the Great House have been converted into units that are available to rent for visitors.

The stables of the Great House have been converted into units that are available to rent for visitors.), led by Dan Macey and regional coordinator Paul Savidge, have already raised $4,500 at a recent holiday dinner. Fundraising activities would be a natural for every JASNA region.

For those not familiar with the Great House, it was the home of the Knight family, wealthy childless relatives of the Austens. The Knights adopted Jane’s older brother, Edward, as a young man and made him their heir. The main Knight estate was at Godmersham in Kent, eight miles south of Canterbury, and that’s where Edward moved as a youth and lived for many years.

In turns out, however, as Linda Slothouber documents in “Jane Austen, Edward Knight, and Chawton,” that the Knight family’s holdings in Hampshire, around Steventon (where Jane grew up) and Chawton (16 miles southeast, where she lived the last eight years of her life) were at least as large as their holdings in Kent. These included farms, timberlands, and houses—including many of the homes in Chawton village.

In 1809, after his mother and his sisters Cassandra and Jane and their sister-in-law Martha Lloyd had traipsed about southeast England for four years in search of cheap quarters, Edward made the old bailiff’s cottage at the bottom of the village of Chawton available to the Austen women. That house is now the separate Jane Austen’s House Museum.

It was in the peace and tranquility of Chawton Cottage that Austen wrote or heavily revised the six major works that brought her posthumous fame.

In addition, Edward began to spend more and more time in Hampshire on estate business. Once his patroness, the elder Mrs. Knight

The Austen women would walk a short distance down the lane from Chawton Cottage to St. Nicholas church. Edward’s Great House was just up the hill behind the church. Edward had the church rebuilt beginning in 1838, so it looks different than when Jane attended.

The Austen women would walk a short distance down the lane from Chawton Cottage to St. Nicholas church. Edward’s Great House was just up the hill behind the church. Edward had the church rebuilt beginning in 1838, so it looks different than when Jane attended., died in 1812, his time in Hampshire increased still more. This shift created a hub for the Austen family in Chawton. Whenever Edward and his family were in residence, the other Austen siblings would visit regularly, while the Austen sisters would walk to the Great House almost daily. (Frank and his family lived there for a while when he was without a sea command.) The Austen women could walk south down the lane from their cottage in less than ten minutes, either to the church or the Great House, just up the hill behind the church.

Jane’s letters after 1809 recount the enjoyment the Great House provided the family, saying that she went up to the house and “dawdled away an hour very comfortably” or that “we four sweet Brothers and Sisters dine at the Great House today. Is that not natural?” or that “Edward is very well and enjoys himself as much as any Hampshire born Austen can desire.—He talks of making a new Garden.”

These holdings remained in the Knight family and generally prospered until social change and increased taxation led to the decline or demise of many great houses in the twentieth century (see “Downton Abbey”). During World War II, Chawton House, along with other country estates, became home to children

In Austen’s day, the house would have been covered in a white stucco-like plaster, but later Victorians felt that older houses needed to look more rustic and so removed the plaster to expose the rock.

In Austen’s day, the house would have been covered in a white stucco-like plaster, but later Victorians felt that older houses needed to look more rustic and so removed the plaster to expose the rock.evacuated from large cities to avoid German bombing.

Caroline and Paul Knight were the last of the line to grow up in the Great House, which experience Caroline Knight documents in “Jane & Me: My Austen Heritage,” published this year (2017). The last Knight to inherit the home, which had fallen into disrepair, was Richard Knight, who sold it in 1992 to the developers, from whom Sandy Lerner retrieved the lease.

Today the responsibility for protecting Chawton House Library falls on all of those who care about Austen’s life and work.

Consider a Christmas donation in honor of Jane’s Christmas-time birthday. We can all help to save one of the finest women’s libraries in England and simultaneously honor Jane Austen.

The post Jane Austen’s Birthday, Season of Giving, and Chawton House Library appeared first on Austen Marriage.

November 29, 2017

Book Launch of ‘Austen Marriage’; Plus Excerpt, Giveaway!

Having written the last several times about Jane Austen’s relationships with men–and the confusion about which relationships were real and which ones lacked supporting evidence–I am announcing today the launch of the last volume in my trilogy based on her life, “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen.” True to what is (actually) known about her life–and to the events of the turbulent Regency era–the series tells a compelling and believable story of a marriage during the “lost years” of her twenties before she retired to write.

Along with the announcement comes A GIVEAWAY FOR READERS–an eBook copy for the winner, selected from those who comment below. The giveaway ends at midnight EST on 3 December 2017. You may choose whichever volume in the trilogy you prefer.

“The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen” uses the iconic author to explore what life was like for women in the Regency period. Volume I is a charming courtship novel. Volume II is a deep psychological examination of marriage from the woman’s perspective. Volume III is the conclusion that tests Jane’s courage and moral convictions. The last volume is available for order now on Amazon.

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 3, as Jane and her husband begin to confront the first of several crises, both personal and public, that dramatically affect their lives.

Chapter 3

Finally, everything was done. It had taken several days but at last the baggage was unloaded and sorted for use in the big house or placed in storage; the latest contrivances that Ashton had collected were distributed to sometimes doubting employees; and the inhabitance had passed the white-gloved inspection by the butler, Mr. Hanrahan, and the housekeeper, Mrs. Lundeen.

Hants House thus secured and the baby napping, Jane made her brisk way up to the Greek temple from which she would have a clear view of the estate’s immediate environs. Her lifelong preference was to meander among the fields. She had been back to the top of the hill only a couple of times since their fateful confrontation there—an argument whose ferocity could only have led to marriage. Twenty months ago, it was: an eternity in terms of life lived and changes undergone. Today, for some reason, she needed elevation, as if by gaining the purer air of altitude she could rise above her sooty mood.

Her route took her through the hedgerows and the park, through deliberately casual arrangements of trees—each of which had the same unlikely combination of oak, birch, and ash—around the manmade lake, and up the rise to the Ionic temple. This fashionable folly was the work of Ashton’s parents, as leading Hampshire landholders were required to have at least one rustic ruin. Her husband would have planted trees with commercial value and used the lake to water them. Even now he spoke of how he might justify the expense of converting the temple into an astronomical observatory. She smiled to herself, though, knowing very well it would remain sacredly untouched as the place their life began together.

She did not sit inside on the stone slab, which always felt cold, but walked slowly around the building, taking in the lands and sky. Though below her by a hundred feet, Hants House itself sat on a small rise to the south of her position, fronted by the lawn, the brook, and the meadow. Their lane paralleled the brook in curling around several large irregular tree-covered mounds before angling down a sharp slope to the village. Behind the main building were the pond, the stables, and the usual out-buildings needed to support a country house and working farm. Because Hants had grown by acquisition over more than a hundred years, it had inherited rather than constructed many of its larger buildings. The dispersion of these—the oat, wheat, and barley barns, the fodder house, cart barn, and chicken houses—lent an air of disorganization in contrast to the neatness of a typical estate. This layout, however, meant that many buildings lay close to the fields and livestock, lessening the work for laborers. Beyond these, farmlands rolled east in soft undulations planted in grain and hay, and holding many varieties of livestock. To her left, many more fields stretched up the green valley northward. Some were worked by tenant or yeoman farmers, but this area also included their own lands-in-hand, on which grazed the many horses bred and trained for the Army.

Everywhere, men worked, as signified by the occasional shout or command, the heavy movement of wagons, or the ringing strike of the smith. Everywhere, fireplaces smoked, the women already preparing supper. There were the fresh, orderly strokes of green as spring thrust itself out of the tilled ground. Trees were in that state just beyond budding such that their leaves seemed less blooms than green vibrations in the air. The air smelled of the green of the season. In the distance, on both sides, she could just discern the sharp quick movements of newborn animals, and the jostling of the older animals as they tried to avoid the unpredictability of prance and buck. Somewhere came the startling sound—part whinny, part scream—of a horse that had lost sight of its favored companion.

From here she could also see the coal-gas manufactory, tucked behind a small outcropping that served as a shield against any inadvertent detonation. It sat in a bed of new wood chips that, fresh as a bird’s nest, softened the determined jaws of the building. It was this project that had decided the Dennises to relocate to Southampton with Jane’s family at the first of the year. Their removal had enabled the renovation of Hants House to incorporate the modern Rumford fireplaces and kitchen stoves, under Ashton’s edict that he would not sell what he himself did not use; and the installation of coal-gas lamps in place of candles, which required the manufactory close at hand.

Because only a handful of servants had been needed in Southampton, most of the staff had received temporary outdoor assignments with Mr. Fletcher, the steward, well away from the potential danger zone of the developing gas mechanisms. Jane was satisfied that the staff was put to good use, as her farm-girl eyes could discern subtle improvements in fencing, hay storage, and weed removal—the last of the many chores that are seldom fully completed over winter.

The Dennis entourage had returned after the difficult but ultimately safe delivery of Mary’s baby, a girl named Mary Jane. Worry lingers over every pregnancy and birth, but Jane had been particularly concerned about the wife of her brother Frank. Mary had been ill, sometimes violently, and suffered fainting spells all during her pregnancy; and her delivery, just a few months after Jane’s own, reminded Jane vividly of the complications she herself had suffered. Mary’s confinement had, in fact, been so difficult as to alarm them all extremely, her safety and that of her baby hanging in the balance. Like Jane, however, Mary made a rapid recovery. This somehow seemed to bode well as much for Jane as for her sister-in-law, and her spirits freshened with the breeze that drove away the clouds that had sulked over the Southampton port for weeks. Within a few days, they felt free to start for Hants.

The sun accompanied them on their journey north and had been shining ever since. Every corner of the house was now dry and warm, in contrast to the musty damp it exhaled after prolonged disuse of the previous rainy weeks. By the time she reached the top of the hill today, she felt that she had climbed completely out of her despondency.

And now, finally, she felt safe enough to address her fears about her baby. She could not believe there was anything wrong with George, who had filled out as plump and strong as a piglet; but simultaneously she could not fully dispute the indications, subtle and otherwise, that some things were not quite right with him either. … She had no definitive knowledge of the speed at which a baby developed, but she had the experience of a lifetime caring for the children of her relatives, as well as her own instincts as a mother. …

Jane could not consider the possibility of what might be wrong without initial consideration of the litany of things that were right. George was happy; he smiled and gurgled with pleasure whenever his mother or father played with him. He made the requisite smacking noises, though with less of the fullness of the mouth that would soon turn sound into vowels. His sense of touch was superb, and so was his sensitivity to pain. The slightest pinch brought a howl of protest. His taste was acute—he loved honey when she dabbed it on his tongue and pulled the most awful face when she experimented with something sour. His sight seemed fine—he lit up whenever he saw her, as if it were a game when she suddenly appeared. When they were together he stared so intently he might have been trying to penetrate her soul.

And yet …

—

I hope you will take a look at how life might have been for Jane Austen–and how, if the literary culture of her day had allowed, she might have written about the deepest matters of the heart. And what might have compelled her to declare that everybody had the right to marry once in their lives for love.

The post Book Launch of ‘Austen Marriage’; Plus Excerpt, Giveaway! appeared first on Austen Marriage.

November 12, 2017

Last Volume of ‘Marriage’ Available for Pre-order

My last several posts have provided background on what little is known about Jane Austen’s relationships with men. In short, several promising relationships ended prematurely and, according to tradition, she lived a quiet life as a spinster, composing or extensively revising her novels at the family cottage in the village of Chawton, Hampshire.

But as I’ve shown in my blogs about her boyfriend and other suitors and about her marriage proposal and rejection, the information about her romances is neither conclusive nor consistent. In particular, her otherwise well-documented life has a gap of seven years from her mid-twenties until she moved to Chawton, largely because her sister Cassandra destroyed almost all the letters and any of Jane’s journals from that period.

These missing years led me to write the trilogy “The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen,” in which I use the iconic author to explore what life was like for women in the Regency period. Volume I is a charming courtship novel; Volume II is a deep psychological look at marriage from the wife’s perspective; Volume III is the conclusion that tests Jane’s courage and moral convictions. I’m pleased to announce that the last volume is available for pre-order now on Amazon.

The series resolves the mystery of Austen’s life before she devoted herself fulltime to her writing: Why the enduring rumors of a lost love or tragic affair? Why, afterward, did the vivacious Jane prematurely put on the “garb of middle age” and retire to write her books? Why, upon her death, did her beloved sister destroy almost all evidence of her life in that period?

I hope you will take a look at how life might have been for Jane Austen–and how she might have written about the deepest matters of the heart if female authors had been able to do that in her lifetime.

The post Last Volume of ‘Marriage’ Available for Pre-order appeared first on Austen Marriage.