Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 44

September 3, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Government's Cancelling Harvard Contracts Violated First Amendment, Judge Rules

From today's decision by Judge Allison Burroughs (D. Mass.) in President & Fellows of Harvard College v. U.S. Dep't of Health & Human Servs.:

Harvard asserts that the Defendants' actions in this case "violated Harvard's First Amendment rights in at least two ways: 1) by retaliating against Harvard based on the exercise of its First Amendment rights, and 2) by imposing content- and viewpoint-based burdens on those rights through the imposition of funding conditions that are unrelated to any legitimate government interest in combating antisemitic harassment or otherwise." Because of this, Harvard contends that "[t]he Freeze Orders and Termination Letters should be vacated and set aside, and any further similar action against Harvard should be permanently enjoined." …

The court concluded that the government's actions were unconstitutional retaliation for Harvard's exercise of First Amendment rights:

Harvard engaged in constitutionally protected conduct 1) when it refused the terms set forth in the April 11 Letter, which sought to control viewpoints at Harvard, and 2) when it filed this lawsuit. Defendants do not dispute that the latter constitutes protected conduct. As to the April 11 Letter rejection, there is "a zone of First Amendment protection for the educational process itself," that encompasses not only "the independent and uninhibited exchange of ideas among teachers and students," but also Harvard's "autonomous decisionmaking." The rights protected by the First Amendment include the right to "manage an academic community and evaluate teaching and scholarship free from [governmental] interference," as well as Harvard's "prerogative 'to determine for itself on academic grounds who may teach'" and what is taught in the "college classroom."

Defendants' April 11 Letter, on its face, was directed at these core freedoms, and Harvard's April 14 rejection, on its face, was aimed at preserving them. The April 11 Letter stated, in no uncertain terms, that the letter would constitute an "agreement in principle that w[ould] maintain Harvard's financial relationship with the federal government" but only if Harvard agreed to "audit the student body, faculty, and leadership for viewpoint diversity," report that audit to the government, and "hir[e] a critical mass of new faculty" and "admit[] a critical mass of students … who will provide viewpoint diversity."

It further required Harvard to "abolish all criteria, preferences, and practices, whether mandatory or optional, throughout its admissions and hiring practices, that function as ideological litmus tests;" to audit "programs and departments that … reflect ideological capture;" to "immediately shuttter all diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, committees, positions, and initiatives … including DEI-based … speech control policies," and to demonstrate that it had done so "to the satisfaction of the federal government." In brief, the April 11 Letter purported to require Harvard to overhaul its governance, hiring, and academic programs to comport with the government's ideology and prescribed viewpoint….

Based on this administrative record, the Court is satisfied that Harvard's protected conduct was a substantial and motivating factor in the Freeze Orders and Termination Letters. Defendants contend, however, that Harvard's retaliation claim nonetheless fails because "the agencies' terminations are explained by a nonretaliatory purpose: opposing antisemitism," such that the government "would have terminated" the grants irrespective of Harvard's viewpoints. This argument does not carry the day.

Defendants have failed to meet their burden to show they acted with a non-retaliatory purpose for several reasons. First, as discussed, the April 11 Letter specifically conditioned funding on agreeing to its ten terms, only one of which related to antisemitism, while six related to ideological and pedagogical concerns, including who may lead and teach at Harvard, [HHSHarv_00000098–99 ("Governance and leadership reforms;" "Merit-Based Hiring Reform")], who may be admitted, [HHSHarv_00000099 ("Merit-Based Admissions Reform;" "International Admissions Reform")], and what may be taught, [HHSHarv_00000099–100 ("Viewpoint Diversity in Admissions and Hiring;" "Discontinuation of DEI")]. Additionally, Defendants' argument ignores that Harvard's April 14 letter rejected only the conditions it viewed as infringing on its First Amendment rights and, in fact, specifically agreed to discuss measures aimed at combatting antisemitism, [HHSHarv_00000104–105 ("Harvard remains open to dialogue about what the university has done, and is planning to do" to combat antisemitism)], an offer Defendants similarly disregarded when instituting the first funding freeze on the basis of "Harvard's statement[s]" hours later.

Moreover, although combatting antisemitism is indisputably an important and worthy objective, nothing else in the administrative record supports Defendants' contention that they were primarily or even substantially motivated by that goal (or that cutting funding to Harvard bore any relationship to achieving that aim). As discussed further infra, before the April 14

Freeze Order, Defendants had announced a funding review consistent with the goals of combatting antisemitism; the record, however, does not reflect that Defendants engaged in such a review, weighed the value of any grant, gathered any data regarding antisemitism at Harvard, or considered if and how terminating certain grants would improve the situation for Jewish students at Harvard.

Rather, all that Defendants learned between March 31 and April 14, 2025 was that Harvard would not capitulate to government demands that it audit, censor, or dictate viewpoints of staff and students. The fact that Defendants' swift and sudden decision to terminate funding, ostensibly motivated by antisemitism, was made before they learned anything about antisemitism on campus or what was being done in response, leads the Court to conclude that the sudden focus on antisemitism was, at best (and as discussed infra), arbitrary and, at worst, pretextual.

Thus, the Court is satisfied that Harvard is entitled to summary judgment on its claim for First Amendment retaliation on the face of the administrative record. The Court would be remiss, however, if it did not note that the summary judgment record also contains numerous exhibits and undisputed facts that go beyond the administrative record that speak to Defendants' retaliatory motive in terminating Harvard's funding.

Although Defendants now contend that Harvard's April 14 rejection and subsequent lawsuit had nothing to do with their decision to cut its funding, numerous government officials spoke publicly and contemporaneously on these issues, including about their motivations, and those statements are flatly inconsistent with what Defendants now contend. These public statements corroborate that the government-initiated onslaught against Harvard was much more about promoting a governmental orthodoxy in violation of the First Amendment than about anything else, including fighting antisemitism.

For instance, in the forty-eight hours following the April 14 Freeze Order, the President took to social media multiple times to talk about Harvard. He posted on Truth Social that Harvard is "a JOKE" that "should no longer receive Federal Funds." His stated concerns (which would later be echoed in the May 5 Freeze Order) were untethered from antisemitism and instead based entirely on Harvard's "hiring almost all woke, Radical Left, idiots and 'birdbrains' who are only capable of teaching FAILURE to students," including "two of the WORST and MOST INCOMPETENT mayors in the history of our Country," referring to Democratic mayors Bill de Blasio and Lori Lightfoot.

This post echoed his comments from a day earlier, when he opined, again on Truth Social, that "[p]erhaps Harvard should lose its Tax Exempt status and be Taxed as a Political Entity." Again, that post did not reference antisemitism explicitly but rather was focused on Harvard's "pushing political, ideological, and terrorist inspired/supporting 'Sickness[.]'" It was not until nearly ten days later that the President would call Harvard "Anti-Semitic," doing so in a Truth Social post that, in the same breath, called Harvard a "Far Left Institution" and a "Liberal mess, allowing a certain group of crazed lunatics to enter and exit the classroom and spew fake ANGER AND HATE."

A similar barrage followed Harvard's decision to litigate rather than settle this case, with Administration officials being clear about the connection between that decision and the funding cuts. In particular, on May 28, 2025, the Secretary of Education summarized the situation with Harvard, stating:

When we looked at different aspects of what Harvard was doing relative to anti- Semitism on its campuses they were not enforcing Title VI the way it should be. And we had conversations with President Garber and I expected that we would have more, but Harvard's answer was a lawsuit so that's where we find ourselves I think the President is looking at this as, OK, how, how can we really make our point[?]

The same day, during an interview in the Oval Office, the President himself said that Harvard is "hurting [itself]" by "fighting," contrasting Harvard with Columbia, who he noted "has been … very, very bad … But they're working with us on finding a solution." He declared that Harvard "wants to fight. They want to show how smart they are, and they're getting their ass kicked." His conclusion: "[E]very time [Harvard] fight[s], they lose another $250 million."

The court also held, for similar reasons, that "Defendants impermissibly imposed on Harvard content- and viewpoint- based funding conditions that were unrelated to any legitimate government interest."

"[The Supreme] Court has made clear that even though a person has no 'right' to a valuable governmental benefit and even though the government may deny him the benefit for any number of reasons … [i]t may not deny a benefit to a person on a basis that infringes … his interest in freedom of speech." … "[A] funding condition can result in an unconstitutional burden on First Amendment rights." Moreover, it is worth noting that the conditions here are particularly concerning because, as discussed, many of them were based on Harvard's "particular beliefs," NRA v. Vullo (2024), and sought to dictate the content of speech on campus and the "particular views taken by speakers on [particular] subject[s]," Rosenberger v. Rectors (1995). "On the spectrum of dangers to free expression, there are few greater than allowing the government to change the speech of private actors in order to achieve its own conception of speech nirvana." Moody v. NetChoice, LLC (2024).

The court also held that the government's action also constituted unconstitutional coercion in violation of the First Amendment. Finally, from the Conclusion:

This case, of course, raises complicated and important legal issues, but, at its core, it concerns the future of grants sponsoring research that promises to benefit significantly the health and welfare of our country and the world. Through the government's statements and actions, the fate of that research has now become intertwined with the issue of antisemitism at Harvard.

Antisemitism, like other types of discrimination or prejudice, is intolerable. And it is clear, even based solely on Harvard's own admissions, that Harvard has been plagued by antisemitism in recent years and could (and should) have done a better job of dealing with the issue. That said, there is, in reality, little connection between the research affected by the grant terminations and antisemitism. In fact, a review of the administrative record makes it difficult to conclude anything other than that Defendants used antisemitism as a smokescreen for a targeted, ideologically-motivated assault on this country's premier universities, and did so in a way that runs afoul of the APA, the First Amendment and Title VI. Further, their actions have jeopardized decades of research and the welfare of all those who could stand to benefit from that research, as well as reflect a disregard for the rights protected by the Constitution and federal statutes….

The First Amendment is important and the right to free speech must be zealously guarded. Free speech has always been a hallmark of our democracy. The Supreme Court itself has recognized that efforts to educate people, change minds, and foster tolerance all benefit from more open communication, not less. As Justice Brandeis wrote in the seminal case of Whitney California (1927), "[i]f there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence," or, in this case, the forced adoption of a political orthodoxy. As pertains to this case, it is important to recognize and remember that if speech can be curtailed in the name of the Jewish people today, then just as easily the speech of the Jews (and anyone else) can be curtailed when the political winds change direction.

Defendants and the President are right to combat antisemitism and to use all lawful means to do so. Harvard was wrong to tolerate hateful behavior for as long as it did. The record here, however, does not reflect that fighting antisemitism was Defendants' true aim in acting against Harvard and, even if it were, combatting antisemitism cannot be accomplished on the back of the First Amendment. We must fight against antisemitism, but we equally need to protect our rights, including our right to free speech, and neither goal should nor needs to be sacrificed on the altar of the other.

Harvard is currently, even if belatedly, taking steps it needs to take to combat antisemitism and seems willing to do even more if need be. Now it is the job of the courts to similarly step up, to act to safeguard academic freedom and freedom of speech as required by the Constitution, and to ensure that important research is not improperly subjected to arbitrary and procedurally infirm grant terminations, even if doing so risks the wrath of a government committed to its agenda no matter the cost….

There's a lot more in the 84-page opinion, but in this post I thought I'd focus on the First Amendment issues.

The post Government's Cancelling Harvard Contracts Violated First Amendment, Judge Rules appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Should Have Seen That One Coming: Claims Over A&E's "Miss Cleo: Her Rise and Fall" Dismissed

From today's decision by Judge Dale Ho (S.D.N.Y.) in Psychic Readers Network, Inc. v. A&E Television Networks, LLC:

"Call me now!" So ordered Miss Cleo, a television psychic who, in the late 1990s, offered purported spiritual guidance via a pay-per-minute telephone hotline. Last autumn, Hillionaire Productions LLC and A&E Television Networks, LLC … produced and aired, respectively, a biopic about Miss Cleo's life. Plaintiff Psychic Readers Network ("PRN") subsequently filed this lawsuit. PRN claims it created the Miss Cleo persona and that it holds several copyrights and trademarks associated with the Miss Cleo character. It accuses Defendants of, inter alia, copyright infringement, trademark infringement, and unjust enrichment based on the biopic's script and imagery….

Unless otherwise specified, the following facts are taken from PRN's Amended Complaint and the documents incorporated by reference therein. The Court assumes these facts are true for the purpose of adjudicating this motion to dismiss….

PRN began offering psychic readings over the telephone in the 1990s. Later that decade, PRN selected Youree Dell Harris, one of its telephone "psychic advisors," to serve as its spokesperson. Harris performed her spokesperson duties in character as "Miss Cleo," a spirited "clairvoyant" who purported to use tarot cards to predict callers' futures. PRN "created the Miss Cleo persona," which "became famous" based on PRN's extensive advertising efforts. Capitalizing on Miss Cleo's popularity, PRN "created television commercials, infomercials, press relations, campaigns, radio spots, books, tarot cards and numerous other materials all featuring the Miss Cleo character [to] promot[e] its psychic services and products." …

PRN filed this suit after "Defendants produced and began distributing the film 'Miss Cleo: Her Rise and Fall.'" PRN alleges that "Miss Cleo: Her Rise and Fall" ("the biopic") "freely copies and recreates [its] copyrighted materials, including, but not limited to, use of the look and feel of Plaintiff's television commercials including the Miss Cleo character's appearance, dress and tag lines such as 'Call Me Now.'" Defendants did not receive permission from PRN to include the Miss Cleo character in the biopic. Moreover, PRN avers that the biopic is "replete with false statements and inaccuracies," including a "false portrayal of an officer of PRN as a drunken, ruthless Wall Street CEO."….

People writing and making films about copyrighted or trademarked material generally have considerable latitude to quote parts of the material in the process (under fair use and related doctrines). But here, the court didn't have to reach that, because it found that plaintiff's Complaint hadn't adequately alleged infringement:

The only material for which the Complaint adequately alleges (1) the specific works that are the subject of the copyright claim, (2) PRN's ownership of the copyrights for those works, and (3) that the copyrights are registered are the Miss Cleo tarot deck, book, and videocassette. PRN "fails to allege [its] present ownership of the [other] copyrights at issue." Beyond a bald assertion that it "is the holder of a seven [sic] registered copyright[s] for Miss Cleo Creatives," PRN provides this Court with no evidence that it can lawfully pursue copyright infringement claims for anything beyond the three pieces of media for which it supplies registration numbers….

Having narrowed the copyrights at issue here to the Miss Cleo tarot deck, book, and videocassette, the only remaining issue is whether PRN has adequately pled "by what acts during what time the defendant infringed the[se] copyright[s]." Even under the most generous reading of the Complaint, PRN fails to meet this requirement.

Regarding copyright infringement, the Complaint alleges that "the Film freely copies and recreates Plaintiff's copyrighted materials, including but not limited to, use of the look and feel of Plaintiff's television commercials including the Miss Cleo character's appearance, dress and tag lines such as 'Call Me Now.'" It also states that "Defendants have infringed Plaintiff's copyrights in Plaintiff's Miss Cleo Creatives by reproducing, distributing, and making available to the public the infringing 'Miss Cleo: Her Rise and Fall' production without authorization in violation of the Copyright Act."

But these statements are not enough to "give the defendant[s] fair notice of what the … claim is and the grounds upon which it rests." "Rule 8 [of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure] requires that the particular infringing acts be set out with some specificity. Broad, sweeping allegations of infringement do not comply with Rule 8." Here, PRN's Complaint—which does not so much as even mention if, when, and where the three copyrighted works appear in the allegedly infringing biopic—cannot stand.

The court also rejected PRN's trademark claim:

[T]he Complaint provides no evidence that PRN "owns a valid protectable mark" in Miss Cleo…. [T]he Complaint states that one of PRN's subsidiaries had "applied for registration of the mark 'Miss Cleo' with the United States Patent and Trademark Office." It does not say that the Miss Cleo mark was registered at the time PRN commenced this case. And, in fact, PRN acknowledges that "the final registration [for the Miss Cleo mark] was issued by the USPTO on January 7, 2025…. PRN's acknowledgement that it did not hold a valid, protectable registered trademark at the time this case was filed is fatal to its Lanham Act claim…. And [PRN's] lack of standing is not cured by the fact that the Miss Cleo mark was eventually registered because "standing is measured as of the time the suit is brought." …

The court therefore declined to consider plaintiffs' state law claims ("for deceptive and unfair trade practices, for unjust enrichment, and for defamation"), leaving them to any future state court proceeding. And the court noted,

Defendants submitted, as an exhibit, a physical copy of "Miss Cleo's Tarot Power Deck." Unfortunately, the Court could not divine the proper outcome of this Motion by tarot.

CeCe Cole and Scott Jonathan Sholder (Cowan DeBaets Abrahams & Sheppard) represent defendants.

The post Should Have Seen That One Coming: Claims Over A&E's "Miss Cleo: Her Rise and Fall" Dismissed appeared first on Reason.com.

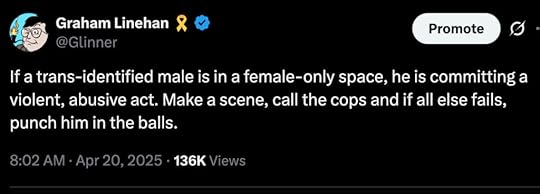

[Eugene Volokh] Would Graham Linehan's "if All Else Fails, Punch Him in the Balls" Be Protected Under U.S. Law?

Irish writer Graham Linehan has reportedly been arrested on his return to the U.K., in part apparently based on this Tweet that he had posted:

I don't know whether this is indeed punishable under English law; I have a hard enough time keeping track of the law of one country. But someone asked me whether this would be punishable even under U.S. law, so I thought I'd post about it.

[1.] The incitement exception to the First Amendment wouldn't apply here. Consider Hess v. Indiana, a 1973 Supreme Court case, where Hess was prosecuted for saying, as a demonstration that had blocked the street was being cleared, "We'll take the fucking street later" or "We'll take the fucking street again." The Court reversed the conviction, applying (and elaborating on) the famous Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) precedent (emphasis added):

The Indiana Supreme Court placed primary reliance on the trial court's finding that Hess' statement "was intended to incite further lawless action on the part of the crowd in the vicinity of appellant and was likely to produce such action." At best, however, the statement could be taken as counsel for present moderation; at worst, it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time. This is not sufficient to permit the State to punish Hess' speech.

Under our decisions, "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action." Brandenburg. Since the uncontroverted evidence showed that Hess' statement was not directed to any person or group of persons, cannot be said that he was advocating, in the normal sense, any action. And since there was no evidence, or rational inference from the import of the language, that his words were intended to produce, and likely to produce, imminent disorder, those words could not be punished by the State on the ground that they had "a 'tendency to lead to violence.'"

The Tweet likewise appears to be "at worst, … nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time," and it wasn't "intended to produce, and likely to produce imminent disorder."

This, by the way, is why statements such as "punch a Nazi," "snitches get stitches," T-shirts with a rifle (with or without Malcolm X) and the phrase "by any means necessary," and the like are generally constitutionally protected (absent advocacy of imminent violence or, as item 2 suggests, a specific target).

[2.] U.S. law has also, since Brandenburg and Hess, recognized a solicitation exception (the leading cases are U.S. v. Williams (2008) and U.S. v. Hansen (2023)). The Court wasn't clear what the exact scope of the exception was, but it appears to apply to speech intended to produce "specific conduct," as opposed to "abstract advocacy." The solicitation exception differs from the incitement exception in that it seems to lack an imminence requirement, but applies only to such advocacy of something specific, such as a transaction as to specific contraband or, I would think, an attack on a specific person.

I think that, under that exception, a Tweet saying "You should punch trans activist Pat Jones in the balls if you ever come across him" would likely be solicitation even in the absence of imminence (at least so long as Tweet is reasonably understood as serious rather than a joke or hyperbole). But here the advocacy appears not to target any particular person.

[3.] I also don't think this would be punishable under the "true threats" exception to the First Amendment. To be an unprotected true threat, (1) the speech has to be reasonably interpretable as a statement that says the speaker (or his confederates) themselves plan to do something (as opposed to a statement that urges others to do something) and (2) the speaker must have "consciously disregarded a substantial risk that his communications would be viewed as threatening violence," see Counterman v. Colorado (2023). I don't think this is the situation here. see, e.g., U.S. v. Bagdasarian (9th Cir. 2011).

[4.] Ken White says that the Tweet is "within shouting distance of prosecutable in the U.S." ("[t]he relevant question is whether it is sufficiently imminent to meet our incitement standard") and "would very plausibly get charged in the U.S." (though "it's not clear the prosecution would succeed"). Maybe; it's hard to know for sure, since charging decisions are made by tens of thousands of prosecutors throughout the country, and different prosecutors might interpret the precedents differently (or might not even be fully aware of Hess, even if they know about the less specific but more famous Brandenburg).

But if the question is whether, under modern First Amendment precedents, the Tweet would have been constitutionally protected in U.S. courts, I think the answer is yes.

The post Would Graham Linehan's "if All Else Fails, Punch Him in the Balls" Be Protected Under U.S. Law? appeared first on Reason.com.

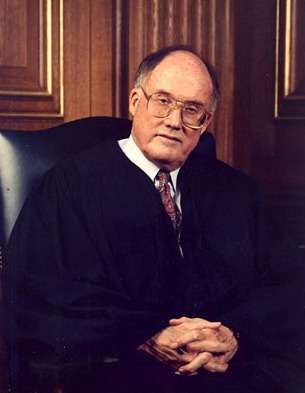

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: September 3, 2005

9/3/2005: Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist dies.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist

The post Today in Supreme Court History: September 3, 2005 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Wednesday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Wednesday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

September 2, 2025

[Josh Blackman] What Do We Make Of The Boston Federal Judge Who Apologized For Not Knowing Emergency Docket Orders Are Precedential?

[Judges who are unfamiliar with the workings of the emergency docket should be more cautious in granting emergency relief against the federal government.]

Judge William G. Young of the District of Massachusetts presided over the case that would become NIH v. APHA. In this case, a majority of the Court held that a suit over cuts to funding belongs in the Court of Federal Claims. This ruling followed directly from an earlier ruling, California v. Texas. Justice Gorsuch wrote a sharp concurrence, chiding Judge Young, and other judges, for defying Supreme Court orders. (I discuss this history in my Civitas column.) While writing this piece, I speculated aloud what could possibly be motivating judges who took actions that were inconsistent with the Supreme Court's emergency docket rulings.

Judge Young, to his credit, has shed some light on his thinking. Regrettably, these insights cast even more doubt on the Judge's decision-making authority.

The New York Times offers this account:

Judge Young said on Tuesday that he had not realized he was expected to rely on a slim three-page order issued with minimal legal reasoning in April to his case dealing with a different agency.

"Before we do anything, I really feel it's incumbent upon me to — on the record here — to apologize to Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh if they think that anything this court has done has been done in defiance of a precedential action of the Supreme Court of the United States," said Judge Young, who was appointed to the bench by President Ronald Reagan in 1985.

"I can do nothing more than to say as honestly as I can: I certainly did not so intend, and that is foreign in every respect to the nature of how I have conducted myself as a judicial officer," he added.

…

"I have served in judicial office now for over 47 years," he said. "Never before this admonition has any judge in any higher court ever thought to suggest that this court had defied the precedent of a higher court — that was never my intention."

He went out of his way to stress that it was never clear to him that the court's emergency ruling in the education case represented its thinking in other instances of federal grants the Trump administration has slashed since January.

"I simply did not understand that orders on the emergency docket were precedent," he said. "I stand corrected."

After delivering the apology, Judge Young met with lawyers out of earshot of the public, and eventually ended the hearing without saying more. He scheduled a follow-up hearing on Thursday to determine how the case should proceed.

I believe this apology is sincere and heartfelt. Judge Kozinski once said that being a federal judge means never having to apologize. Judge Young could have said nothing, and no one would have asked him to. Kudos to Judge Young.

But there is a far bigger problem: how could he have made that mistake? Maybe during the early days of the COVID pandemic, it could be argued that the precedential value of shadow docket orders was unclear. But Chief Justice Roberts's concurrence in South Bay become a super-precedent! (I found at least one order from Judge Young in 2021 that cited South Bay and Roman Catholic Diocese. Delaney v. Baker, 511 F. Supp. 3d 55, 72 (D. Mass. 2021) (Young, J.)).

In 2021, Judge McFadden (D.D.C.) co-authored an article on the precedential value of shadow docket rulings. In July 2022, I wrote that West Virginia v. EPA cited as precedents two other shadow docket rulings Alabama Association of Realtors v. HHS and NFIB v. OSHA. And since then, there has been a pretty consistent stream of authorities from the Supreme Court indicating these orders were precedents.

Most recently, DHS v. D.V.D. and Boyle expressly chastised lower courts for not following shadow docket precedents. D.V.D. rebuked Judge Brian E. Murphy, one of Judge Young's colleagues on the District of Massachusetts. Was Judge Young not even aware of that remarkable reversal of his colleague?

Moreover, before Judge Young, the Department of Justice vigorously argued that California v. Department of Education was a precedent. Here is how the emergency application described the record:

When the government pointed out that respondents' challenges to those grant terminations belong in the Court of Federal Claims under California, the district court recognized with serious understatement that California was a "somewhat similar case." App., infra, 221a. Yet the district court dismissed this Court's ruling as "not final" and "without full precedential force," "agree[d] with the Supreme Court dissenters," and "consider[ed] itself bound" by the First Circuit ruling that California repudiated. Ibid.; see id. at 229a (California "is not binding on this Court").

So it is not just the case that the Judge was unaware. Judge Young listened to the government's (correct) arguments, failed to do any additional research on the issue about the precedential value of shadow docket orders, and still issued an injunction against the government. To be sure, there is an academic debate on this issue, but that debate requires knowing both sides. Judge Young didn't even know there was a debate!

The problem here is not Judge Young's sincere mistake. Rather, the trouble arises from his willingness to enter broad relief without conducting sufficient research. Or more precisely, his law clerks were unable or unwilling to advise him otherwise. I find persuasive David Lat's description of law clerks as general counsels, and not associates. They have an obligation to advise their judge in on some fairly obvious Supreme Court precedent. And they failed to do so.

Judge Young turns 85 later this month. He has had a distinguished judicial career spanning half a century. A lot has changed since he graduated law school in 1967. Perhaps this apology provides a moment to reconsider where his talents and efforts are best suited.

At a minimum, this story should be a cautionary tale to the entire judiciary: judges who are unfamiliar with the workings of the emergency docket should be more cautious in granting emergency relief against the federal government. Perhaps readers of this blog take for granted that judges follow the Court as they do. It's not the case. Many federal judges never read new Supreme Court decisions. Maybe they'll ask their clerks to summarize it. Maybe they'll just wait for briefs to come in. Maybe they'll never read the briefs. But if you are such a judge, and you are presented with an emergency petition, you better be damn well sure you are up to speed before granting an injunction, especially an ex parte TRO. It is not the plaintiffs' job to provide a balanced approach to the law--that is what the adversarial process is for.

But you know which Article III nonagenarian still has a firm grasp of Supreme Court doctrine? Judge Pauline Newman. But she was just suspended for another year by the Federal Circuit, which is apparently waiting for her to die. She has nothing to apologize for.

One final note: the Times and other outlets make a point of saying that Young was a Reagan appointee. This point is irrelevant. President Reagan appointed Judge William G. Young to the federal bench in Boston in 1985. To be clear, the Harvard grad's blue slips were signed by Ted Kennedy (ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee) and (freshman) John F. Kerry. Young became eligible for senior status in 2005. In March 2021, only a few months after the inauguration, Young notified President Biden that he would take senior status. If there is any conservative indicia in Judge Young's four-decade tenure on the bench, I can't find it. Just another data point to prove that we shouldn't put any stock in the judicial philosophy of a Republican appointee in a deep blue state like Massachusetts or Hawaii.

The post What Do We Make Of The Boston Federal Judge Who Apologized For Not Knowing Emergency Docket Orders Are Precedential? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] What are the Precedential Values of Wilcox and Boyle?

[Judge Rao explains how to read emergency docket orders on stay applications.]

President Trump removed Federal Trade Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter without cause. The District Court ordered that Slaughter must be reinstated. Today, a divided panel of the D.C. Circuit declined to stay that order. Judges Millett and Pillard found that Wilcox and Boyle did not reverse Humphrey's Executor. As a result, that under-siege precedent controls this case. Judge Rao dissented, and parsed how the lower courts should read emergency docket orders that arise from stay applications.

I do not think this is a case where the D.C. Circuit is overtly defying Wilcox and Boyle, as Justice Gorsuch put it in NIH. Rather, I think the majority and dissent vigorously disagree about how to parse the effect of Wilcox and Boyle on Humphrey's Executor.

The majority opinion explains that Wilcox concerned the NLRB and MSPB and Boyle concerned the CPSC. By contrast, the Supreme Court did not issue any new ruling concerning the FTC. The only precedent on the books for that case is Humphrey's Executor.

In contrast, the present case [Slaughter] involves the exact same agency, the exact same removal provision, and the same exercises of executive power already addressed by the Supreme Court in Humphrey's Executor and subsequent decisions, and so is squarely controlled by that precedent.

I'm not sure that claim is exactly right. The FTC of 1935 is very different from the FTC of 2025. The Commissioners now exercise far more executive power. Judge Rao favorably cites Eli Nachmany's important new paper, The Original FTC. (Query whether Chief Justice Roberts will serve up another blue plate special, and distinguish Humphrey's Executor on the grounds that the members now have more executive power--to paraphrase Shelby County, "history did not end in 1935.")

But let's put aside that factual disagreement. Is it the case that Wilcox and Boyle have no impact on Slaughter? The majority argues that granting the stay would in fact be defying the Supreme Court!

Granting the government's motion would ignore the Supreme Court's stay order in Wilcox, not comply with it. That order said, less than three months ago, that stay decisions by the courts of appeals remain controlled by extant precedent including Humphrey's Executor.

Take that, Justice Gorsuch!

Judge Rao approached this issue from a completely different angle. Indeed, she provides a careful analysis of how lower-court judges should read orders from the emergency docket. The majority opinion does not respond to Judge Rao. They should start thinking of a response, because this approach very well may make it into a future Supreme Court decision.

Wilcox and Boyle did not simply decide that Trump had the power to remove members from certain boards. Rather, the Court stated how to resolve emergency applications to stay reinstatement to those boards. In short, the Court held that because these members exercise "significant executive power," the equities favor staying the injunctions. Here is the key paragraph from Judge Rao:

While it is true the removed officer here is a commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission, and the Supreme Court upheld the removal restriction for such commissioners in Humphrey's Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935), a stay is nonetheless appropriate. The Commission unquestionably exercises significant executive power, and the other equities favor the government. These grounds were sufficient to support the Supreme Court's judgment that a stay was warranted in two recent cases in which the district court ordered reinstatement of an officer removed by the President. The Court determined that "the Government faces greater risk of harm from an order allowing a removed officer to continue exercising the executive power than a wrongfully removed officer faces from being unable to perform her statutory duty." Trump v. Wilcox, 145 S. Ct. 1415, 1415 (2025); see also Trump v. Boyle, 145 S. Ct. 2653, 2654 (2025). Because we are required to exercise our equitable discretion in accordance with the Court's directives, the district court's order must be stayed. I respectfully dissent.

Judge Rao writes later:

Granting a stay of the district court's injunction, however, does not require this court to claim that Humphrey's Executor has been overruled. Instead, the stay is warranted by the Supreme Court's decisions to stay injunctions ordering the reinstatement of removed officers.

As I read Judge Rao, Wilcox and Boyle are not precedents for some future motion for summary judgment. Rather, these precedents explain how to handle emergency stay applications concerning reinstatement. Specifically, the Supreme Court has instructed the lower courts of how to balance equities in the case of a reinstatement.

In the stay posture, the Supreme Court has withheld judgment on the lawfulness of the President's removals of so called independent agency heads, focusing instead on the harm to the government from reinstatement. That reasoning similarly requires a stay here while the merits of the removal, and the ongoing validity of Humphrey's Executor, continue to be litigated.

Judge Rao explains:

And finally, we need not definitively determine whether Slaughter's removal was lawful, because we must follow the Supreme Court's conclusion that an injunction reinstating an officer the President has removed harms the government by intruding on the President's power and responsibility over the Executive Branch.

The en banc D.C. Circuit previously held that reinstatement was appropriate. Judge Rao contends that Wilcox and Boyle overruled (or at least abrogated) the en banc precedent.

My colleagues inexplicably stick to this court's en banc decision in Harris v. Bessent, which denied a motion to stay a similar reinstatement injunction. Order at 10 n.1 (citing Harris v. Bessent, No. 25-5037, 2025 WL 1021435, at *2 (D.C. Cir. Apr. 7, 2025) (en banc) (per curiam)). But the en banc court was reversed by the Supreme Court, which granted a stay of the injunction. Wilcox, 145 S. Ct. at 1415. I see no reason to follow overruled circuit precedent rather than Wilcox and longstanding Supreme Court precedent.

This is a very sophisticated approach to parsing emergency docket precedents. Unlike some judges who apparently did not know that emergency docket orders are precedential, Judge Rao is sketching out in what ways these orders are precedential. I think this opinion reinforces Justice Kavanaugh's Boyle concurrence. I like when Judges explain why they are doing what they are doing.

The post What are the Precedential Values of Wilcox and Boyle? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Stephen Halbrook] Second Amendment Roundup: 4th Circuit Upholds Park Ban

[Under Salerno test, ban held not to be invalid in all circumstances.]

On August 27, the Fourth Circuit decided LaFave v. County of Fairfax, Virginia, a challenge to a ban on possession of a firearm in the public parks of the County. The opinion by Chief Judge Diaz avoided reaching the merits because it concluded that plaintiffs could not succeed in their facial challenge. (Disclosure: I represented the LaFave plaintiffs-appellants in the case.)

While not mentioned in the opinion, the parks consist of 23,584 acres of mostly wooded land with 334 miles of trails, which is over 9.3 percent of the land mass of the County. By comparison, the borough of Manhattan, which the Bruen court held does not qualify as a "sensitive place," is only 14,502 acres of densely-populated land.

The LaFave opinion began with recitations from the Bruen decision, including that the Second Amendment protects the "right to bear arms in public for self-defense." More precisely:

Bruen rejected the notion that the sensitive places doctrine allows governments to prohibit firearms in "all places of public congregation that are not isolated from law enforcement," which would "define[ ] the category of 'sensitive places' far too broadly." … "[T]he island of Manhattan," said the Court, doesn't qualify as a sensitive place "simply because it is crowded and protected generally by the New York City Police Department."

Plaintiffs-Appellants argued that the existence of sensitive places within Manhattan did not preclude Bruen from declaring New York's ban on carrying firearms in public places facially unconstitutional, even though firearms could be banned in sensitive places. The Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse and the New York County Courthouse are located at Foley Square in Manhattan, and hundreds of schools are on that urban island. But New York's general carry ban was not valid, even though guns could be prohibited in sensitive places under specific laws.

The LaFave court saw it differently based on the existence of four preschools on a tiny portion of park property. In a facial challenge, the court related, "the challenger must establish that no set of circumstances exists under which the [challenged regulation] would be valid" (Salerno), or that "the statute lacks any 'plainly legitimate sweep'" (Stevens). To prevail against a facial challenge, "the [g]overnment need only demonstrate that [the challenged law] is constitutional in some of its applications." (Rahimi.)

LaFave upheld the ban on guns in the entire parklands on the basis that it may be constitutionally applied at the preschools. It noted that plaintiffs concede that "firearms may be banned in … schools," but contrary to the implication, plaintiffs noted that separate laws banned firearms in schools, but this law did not. No element of the offense of possession of a firearm in a park requires proof that the person possessed the firearm in a school. Heller said in dicta that a gun ban in schools is presumptively valid, but it did not say that one could be convicted under a general gun ban (such as D.C.'s handgun ban) as applied to a gun carried in a school. Here, a park ban is not a school ban.

According to LaFave, "The licensing regime in Bruen required all prospective gun owners to justify their wish to own a gun, regardless of where they sought to carry the weapon. There was no application of that regime that could satisfy the Second Amendment." Given that premise, the licensing regime would not satisfy the Second Amendment even if the applicant wished to carry a gun at a school. But any such carrying would be subject to a separate, specific school ban.

Moreover, the licensing issue did not stand alone – it was relevant only because carrying a firearm without a license was a crime. And the Second Amendment precluded a gun ban in all of Manhattan, even though it is filled with sensitive places.

Consider the implications of the holding that the parks ban is constitutional because a handful of preschools are on park property. Those same preschools are located in Fairfax County, so by implication firearms can be banned in the entirety of Fairfax County.

In more than one post-Salerno case, the Supreme Court clarified that "although statements in some of our opinions could be read to suggest otherwise, our holdings squarely contradict the theory that a vague provision is constitutional merely because there is some conduct that clearly falls within the provision's grasp." E.g., Johnson v. United States (2015). The LaFave court responds: "Plaintiffs' cases adopting a more generous standard all concern vagueness and are unpersuasive in the context of a Second Amendment challenge." Vague laws are precluded by the Due Process Clause. And as Bruen repeats: "The constitutional right to bear arms in public for self-defense is not 'a second-class right, subject to an entirely different body of rules than the other Bill of Rights guarantees.'"

In Rahimi the Court applied the Salerno rule to a specific statute with elements that are not invalid in all applications, not a general gun ban without such specific elements. The statute bans gun possession by a person subject to a court order that includes "a finding that such person represents a credible threat to the physical safety of such intimate partner or child." 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8). The Court upheld this narrow prohibition facially because: "Unlike the regulation struck down in Bruen, Section 922(g)(8) does not broadly restrict arms use by the public generally." The park ban in LaFave does just that.

But what if the statute in Rahimi simply prohibited gun possession without more? It would be invalid in all applications, even as applied to a person who has such a court order. Just because another law could apply to such persons, this law banning guns generally would facially violate the Second Amendment, just like the handgun bans in Heller and McDonald.

Likewise with another precedent cited by the LaFave court, U.S. v. Canada (4th Cir. 2024). It upheld the ban on felon possession of a firearm as facially valid because it could be applied constitutionally in some cases, such as when the felony of conviction was carjacking or armed bank robbery. But again, if the law did nothing more than ban gun possession by all members of the public, it couldn't be constitutionally applied to anyone, even felons.

Salerno itself further illustrates the point. "A facial challenge to a legislative Act" – the Bail Reform Act in that case – "must establish that no set of circumstances exists under which the Act would be valid." The Act provided that a court must "detain an arrestee pending trial if the Government demonstrates by clear and convincing evidence after an adversary hearing that no release conditions 'will reasonably assure … the safety of any other person and the community.'" As applied to dangerous persons, that did not violate the Due Process Clause. But imagine a more general law under which a court could simply detain any arrestee pending trial at whim without any finding at all. That law would be unconstitutional in all circumstances, even as applied to dangerous criminals.

In contrast to LaFave, in Rhode v. Bonta (2025), the Ninth Circuit decided that California's ammunition background check system lacks a "plainly legitimate sweep" and thus was facially unconstitutional. It noted that both Heller and Bruen found the subject laws to be facially unconstitutional.

Almost all Second Amendment challenges where the Salerno rule is applied involve criminal laws, which more often than not are upheld as not invalid in all circumstances. In the few civil cases where Salerno is raised, most courts address the Nation's history and tradition of firearm regulation. The Fourth Circuit in LaFave simply skipped over that analysis and upheld the parks ban based on the theory that a different kind of ban – a ban on firearms in schools – could be validly applied to schools located in parks, and thus the parks ban is not invalid in all applications. That's not a proper application of the Salerno test because the offense of gun possession in a park has no element related to schools.

The bottom line: if the existence of four preschools in the parks justifies a gun ban throughout the parks, the same justification – four preschools – would exist for a gun ban throughout all of Fairfax County. That logic could be applied even wider and would wholly upend the Second Amendment.

The post Second Amendment Roundup: 4th Circuit Upholds Park Ban appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "God, … Some of Your Early Work on Neural Networks Was Genuinely Groundbreaking, …"

["but honestly you’re the worst offender here."]

From Astral Codex Ten:

God: …and the math results we're seeing are nothing short of astounding. This Terry Tao guy -

Iblis: Let me stop you right there. I agree humans can, in controlled situations, provide correct answers to math problems. I deny that they truly understand math. I had a conversation with one of your "humans" yesterday, which I'll bring up here for the viewers … give me one moment …

When I give him an easy problem that he's encountered in school, it looks like he understands. But when I give him another problem that requires the same mathematical function, but which he's never seen before, he's hopelessly confused.

God: That's an architecture limitation. Without a scratchpad, they only have a working context window of seven plus or minus two chunks of information. We're working on it. If you had let him use Thinking Mode…

Dwarkesh Patel: Okay, okay, calm down. One way of reconciling your beliefs is that although humans aren't very smart now, their architecture encodes some insights which, given bigger brains, could -

Iblis: God isn't just saying that they'll eventually be very smart. He said the ones who got through graduate school already have "PhD level intelligence". I found one of the ones with these supposed PhDs and asked her to draw a map of Europe freehand without looking at any books. Do you want to see the result? …

You can come up with excuses and exceptions for each of these. But taken as a whole, I think the only plausible explanation is that humans are obligate bullshitters….

Read the whole thing; I much enjoyed it.

The post "God, … Some of Your Early Work on Neural Networks Was Genuinely Groundbreaking, …" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] The EPA Can Terminate Climate Change Grants to Nonprofits

[A divided panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit vacates a district court injunction barring clawback of climate grants.]

This morning a divided panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit vacated a district court injunction preventing the Environmental Protection Agency from terminating grants given to non-profit organizations by the Biden Administration to promote greenhouse gas reductions and other climate policies. I suspect a petition for rehearing en banc is likely to follow (as might an appeal to the Supreme Court should the en banc D.C. Circuit intervene).

Judge Rao wrote for the panel in Climate United Fund v. Citibank, joined by Judge Katsas. Judge Pillard dissented.

Judge Rao summarizes her opinion as follows:

The Environmental Protection Agency awarded grants worth $16 billion to five nonprofits to promote the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Citing concerns about conflicts of interest and lack of oversight, EPA terminated the grants in March 2025. The grantees sued, and the district court entered a preliminary injunction ordering EPA and Citibank to continue funding the grants.

We conclude the district court abused its discretion in issuing the injunction. The grantees are not likely to succeed on the merits because their claims are essentially contractual, and therefore jurisdiction lies exclusively in the Court of Federal Claims. And while the district court had jurisdiction over the grantees' constitutional claim, that claim is meritless. Moreover, the equities strongly favor the government, which on behalf of the public must ensure the proper oversight and management of this multi-billion-dollar fund. Accordingly, we vacate the injunction.

Her opinion seems quite in line with the way the Supreme Court has been handling cases in which district courts have considered questions Congress has directed to the Court of Federal Claims or administrative entities. While a majority of the D.C. Circuit may disagree with this approach, I doubt a majority of the Supreme Court would. See, for instance, the Court's handling of NIH v. APHA, another case involving grants (and upon which Judge Rao relies).

As noted, Judge Pillard dissents--and at some length. (Her opinion is over twice as long as Judge Rao's opinion for the panel.) From the intro to her 62-page dissent:

On the majority's telling, Plaintiffs bring garden-variety contract claims against EPA's reasonable decisions to terminate their grant awards. That version of events fails to contend with the government's actual behavior and misapprehends Plaintiffs' claims, leading the majority to the wrong conclusion at every step of its review of the district court's preliminary injunction. . . .

In characterizing this case as merely a contract dispute subject to the Tucker Act's jurisdictional bar, the majority baselessly strips the district court of authority to decide these important claims. The majority holds that a plaintiff cannot bring an arbitrary and capricious challenge to any government action that affects something of value that was originally obtained by contract. Maj. Op. 16-18. Doing so undercuts the Constitution's and the APA's checks on the Executive's illegitimate seizure of Plaintiffs' funds and subversion of Congress's will. The government's Tucker Act defense is especially pernicious here. Dismissal of this case presumably will enable the government to carry out its announced plan to immediately and irrevocably seize Plaintiffs' funds. At best, in the unlikely event the government refrains from immediately draining Plaintiffs' frozen accounts, the further delay involved in reinitiating litigation in the Court of Federal Claims will itself irreparably harm the infrastructure projects that cannot move forward and may fail without funding. In these circumstances, "[i]t is no overstatement to say that our constitutional system of separation of powers w[ill] be significantly altered" by "allow[ing] executive . . . agencies to disregard federal law in the manner asserted in this case." Aiken Cnty., 725 F.3d at 267.

The post The EPA Can Terminate Climate Change Grants to Nonprofits appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers