Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 41

August 1, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] Russian Opera Singer Anna Netrebko's National Origin Discrimination Lawsuit Over Firing by N.Y. Metropolitan Opera Can Go Forward

[So a federal judge held Tuesday, reversing its contrary decision from last year.]

From Judge Analisa Torres's decision in Netrebko v. Metropolitan Opera Ass'n, Inc.:

In the [earlier order], the Court found that Netrebko did not allege direct evidence of discriminatory intent…. Netrebko contends, however, that the Court overlooked at least one allegation in the complaint—that the Met replaced Netrebko with exclusively non-Russian artists in the roles for which she had originally been cast….

Among other allegations, [Netrebko] claims that the Met promoted the fact that it replaced her, a Russian, with a Ukrainian artist—and that Gelb even "admitted that [the new performer's] Ukrainian national origin was one reason the Met selected her for the role." Netrebko further alleges that "the Met did not ask artists who were not of Russian origin about their views on Russia's actions or ask them to make statements about the war in Ukraine or denouncing Putin," even though some artists who performed at the Met had "received support from," or even "expressed support for, Putin and/or the Russian government." Together, such allegations support the inference that Netrebko's replacement by non-Russian artists occurred under circumstances giving rise to at least a "minimal" inference of discrimination.

Here's more from the post about last year's decision, which also discusses Netrebko's other claims (as to which the judge didn't change her mind):

[* * *]

From [the Aug. 22, 2024] opinion by Judge Analisa Torres (S.D.N.Y.) in Netrebko v. Metropolitan Opera Ass'n:

After Anna Netrebko, an acclaimed opera singer, refused to repudiate Russian President Vladimir Putin in the wake of Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the Metropolitan Opera fired her….

Netrebko first alleges that the Met's February 27 Policy, in which it announced it would cut ties with artists and institutions that support or are supported by Putin, is "facially discriminatory" because it "singles out Russian artists." The Met argues that the Policy was "a political statement" and demonstrates that Netrebko's termination "ha[d] nothing to do with Netrebko being Russian" and everything to do with the Met's support for Ukraine and Netrebko's support for Putin….

The February 27 Policy is not facially discriminatory as it does not explicitly implicate a protected class. On its face, non-Russians can run afoul of the Met's policy. Moreover, a policy that targets "a generalized political affiliation, [and] not a specific national origin," cannot form the basis of a claim for national origin discrimination. That there exist Russian expatriates in the United States who support Putin does not compel a finding that the February 27 Policy facially discriminates against them.

Next, Netrebko alleges that the Met's discriminatory motivation is evidenced by (1) the "pretextual nature" of its stated reason for her firing (Netrebko's support of Putin), and (2) the fact that she was replaced by non-Russian performers. The Court disagrees.

First, the truth or falsity of the Met's stated reason for Netrebko's termination is immaterial so long as the Met's decision was based on a belief held in good faith. Netrebko has alleged no facts which plausibly suggest that the Met's stated reason for her termination masked an invidious motive to discriminate against Russians. This argument is, therefore, unavailing.

Netrebko's claim that her replacement by non-Russian performers establishes pretext fares no better…. The [Complaint's] treatment of Netrebko's non-Russian replacements is too cursory to permit a jury to determine whether they were similarly situated. "Plaintiff must 'show that similarly situated employees who went undisciplined engaged in comparable conduct.'" In support of this claim, Netrebko alleges only her replacements' nation of origin. The SAC fails to describe how Netrebko's non-Russian [Ukrainian, Italian, and Norwegian] replacements might be similarly situated as either Putin supporters or holders of a political belief or affiliation the Met finds similarly odious.

At bottom, the Met's firing of Netrebko, "while potentially indicating unfair dislike," does not sufficiently implicate her national origin to permit an inference of discrimination….

But the court concluded that

[Netrebko] has pleaded a claim of gender discrimination based on the "more favorable treatment" received by her male counterparts whom Netrebko alleges also had connections to Putin and the Russian state. For example, she alleges that the male opera singer Ildar Abdrazakov performed at political events, "including at least one event at which Putin … spoke about the war in Ukraine," and that Abdrazakov organized a Kremlin-backed music festival. She further states that male opera singer Evgeny Nikitin was featured at a Victory Day event involving Putin, and that Igor Golovatenko and Alexey Markov have performed at state-sponsored venues since the invasion of Ukraine. Although Netrebko has not alleged comparable conduct on the part of her female, non-Russian replacements, she has alleged conduct that permits comparison on the basis of gender.

{Netrebko does not claim that the male Russian performers had connections to Putin outside of a professional performance setting or made statements hinting at a pro-Putin stance. At summary judgment, Netrebko will be required to produced evidence to establish that the conduct of the male performers is not "too different in kind to be comparable to [Netrebko's] conduct."}

Here, Netrebko's claim of gender discrimination crosses the line from merely possible to plausible. The Second Circuit has held that "[a] defendant is not excused from liability" when discrimination is not the product of "a discriminatory heart, but rather [ ] a desire to avoid practical disadvantages" such as "negative publicity" or public pressure. "[C]lear procedural irregularities," against the backdrop of potential backlash and public scrutiny, may evince an unlawful "policy of bias favoring one sex over the other."

In [two past Second Circuit cases], male plaintiffs accused of sexual misconduct alleged that they were subject to disparate treatment when the defendant universities—facing public pressure over their mishandling of sexual assault and harassment on campus—found them culpable after hasty adjudicative processes plagued by procedural irregularities. The Circuit found that the irregularities in the handling of these matters coupled with other allegations were sufficient to establish a prima facie case of gender discrimination.

Here, the simultaneity of Netrebko's termination, public outcry over Putin's 2022 invasion, and the Met's efforts to show its pro-Ukraine bona fides—taken in conjunction with Netrebko's claim that the Met arbitrarily applied the February 27 Policy—suffice at the pleadings stage to create an inference of discrimination. Since 2017, the Met has collaborated with Moscow's Bolshoi Theatre, a "state-controlled institution," and Gelb [the Met's general manager] was in Moscow for a Bolshoi rehearsal "on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine." Netrebko alleges that the Met's "rapid turnabout on the Russian question"—from being at the Bolshoi one day to firing her a few days later—was part of its "anti-Russia publicity campaign."

Given the prominence of female opera singers compared to their male counterparts, Netrebko claims that "actions against [her], as a well-known 'diva' or 'prima donna' … would garner more international headlines than similar actions taken against male artists and would therefore be more successful in furthering the Met's anti-Russia publicity campaign." {Further supporting Netrebko's gender discrimination claim, an article cited—and incorporated by reference—in the SAC notes that another female Russian performer, Hibla Gerzmava, was fired by the Met after "com[ing] under fire for her ties to Putin," including for "signing a letter in support of Putin in 2014."}

In all, Netrebko plausibly alleges that, faced with "practical disadvantages"—such as the possibility of public pressure and negative press over its connections to the Russian state and individuals aligned with Putin—the Met adopted a "policy of bias favoring one sex over the other." …

Finally, Netrebko alleges that over the course of a year—coinciding with Russia's invasion of Ukraine and her firing by the Met—Gelb, on behalf of the Met, defamed her on multiple occasions…[:]

{In an August 14, 2022 article in the Sunday Times, Gelb stated, "I was always aware [Netrebko] was, you know, a huge Putin supporter … The fact is she put herself in this awful position by being Putin's political acolyte and fan club member over a period of many years, which I had witnessed."In the same Sunday Times article, Gelb stated "When the war is over, Putin has been defeated, he's no longer in office, [and] [Netrebko]'s demonstrating genuine remorse. Maybe that's when we can consider [rehiring her]…. But I would say there's a very small chance of that happening.In a September 12, 2022 Guardian article, Gelb stated that Netrebko "is inextricably associated with Putin… She has ideologically and in action demonstrated that over a period of years."In a November 9, 2022 article in Limelight, Gelb stated, "Netrebko has demonstrated over a period of many years that she was kind of in lockstep politically and ideologically with Putin."In a February 27, 2023 Associated Press article, Gelb stated, referencing Netrebko's termination, "It's a small price to pay…. To be on the side of right was what's important. I wouldn't be able to look at myself in the mirror and have known Putin supporters performing on our stage."In a March 17, 2023 New York Times article, Gelb stated, "Although our contracts are 'pay or play,' we didn't think it was morally right to pay Netrebko anything considering her close association with Putin…. It's an artistic loss for the Met not having her singing here. But there's no way that either the Met or the majority of its audience would tolerate her presence."}Because Netrebko is a public figure, she must prove that the allegedly defamatory statements were made with actual malice. "Actual malice is a high bar. A plaintiff cannot, for example, allege merely that the speaker was negligent in failing to uncover falsity or that he should have investigated his claims further before speaking." Actual malice exists if a false statement was made "with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not." "A 'reckless disregard' for the truth requires more than a departure from reasonably prudent conduct." The allegations must "permit the conclusion that the defendant in fact entertained serious doubts as to the truth" of the statements. Moreover, the actual malice standard is subjective and must be proven by clear and convincing evidence….

Netrebko has not met this high bar. She alleges that because the Met knew she made multiple statements opposing the war, distancing herself from Putin, and disavowing any connection to him, its subsequent statements referring to her as a Putin supporter must have been made with knowledge of their falsity or with reckless disregard for the truth. Yet, such a finding is not required. There is a difference between the Met knowing that Netrebko uttered these statements and the Met believing that what she said was true.

Netrebko fails to allege any facts demonstrating that her statements disassociating herself from Putin's war against Ukraine altered the Met's subjective belief that she supported the Russian leader. Thus, she has not adequately pleaded that the Met made any of the allegedly defamatory statements with "high degree of awareness of their probable falsity." … Although a court "typically will infer actual malice from objective facts" like "the defendant's own actions or statements, the dubious nature of [its] sources, and the inherent improbability of the story," the [Complaint] offers none that permit the Court to make this inference. At most, the [Complaint] contains "bare assertions of ill will," which are not sufficient to allege actual malice.

The post Russian Opera Singer Anna Netrebko's National Origin Discrimination Lawsuit Over Firing by N.Y. Metropolitan Opera Can Go Forward appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: August 1, 1942

8/1/1942: Military commissions conclude for eight nazi saboteurs. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of these trials in Ex Parte Quirin.

The Stone Court (1942)

The Stone Court (1942)

The post Today in Supreme Court History: August 1, 1942 appeared first on Reason.com.

July 31, 2025

[Paul Cassell] The Defense Challenge to Alina Habba's Appointment is Weak

[A defendant has challenged Acting New Jersey U.S. Attorney Alina Habba's appointment under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act, but he has no real case under the statute's plain language.]

Previously Steve Calabresi and I have blogged about how Alina Habba's appointment as Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Jersey is valid under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA). Calabresi's initial post argued that New Jersey judges lacked constitutional power to displace Habba by appointing an interim replacement. But while I disputed that constitutional conclusion, I ultimately reached the same position as Calabresi under the relevant statutes. I concluded that, under 28 U.S.C. § 546 and the FVRA, Habba was appropriately serving as the Acting U.S. Attorney. In my last post, I explained that the Justice Department had made a powerful defense of Habba's appointment under the FVRA. Earlier today, the defendant challenging Habba's appointment filed a reply brief. But that brief fails to engage on the main issues surrounding the FVRA. It appears that the defendant's position is weak and should be swiftly be rejected.

The timeline is important here. To recap the (essentially undisputed) facts, on March 27, 2025, the Attorney General appointed Ms. Habba interim United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey pursuant § 546. (To make his case seem stronger than it really is, the defendant's brief claims that the Ms. Habba was appointed three days earlier, on March 24—citing a CBS news article. But the Justice Department's brief includes as an exhibit the actual appointment order, which is dated March 27, 2025.) Section 546 explicitly limits such interim appointments to a maximum period of 120 days. 5 U.S.C. § 3346(a)(1). Given an appointment of 120-days, Habba's interim appointment would have expired on on Saturday, July 26.

On June 30, 2025, President Trump formally nominated Ms. Habba for the permanent position of United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey and submitted her nomination to the Senate. On July 24, 2025, before the Senate had acted, the President withdrew Habba's nomination. That same day—July 24, two days before her interim appointment expired—Habba resigned her interim position as United States Attorney. The Attorney General then immediately appointed her as a Special Attorney under 28 U.S.C. § 515, which appointment Ms. Habba accepted. Exercising her authority under 28 U.S.C. §§ 509, 510, 515 and 542, among other provisions, the Attorney General also designated Ms. Habba as the First Assistant in New Jersey, effective upon her resignation as the interim United States Attorney. All of this occurred on Thursday, July 24, two days before the 120-day limit period in § 546(c)(2) expired at 12:00 a.m., Saturday, July 26. As a result of her holding the position of First Assistant U.S. Attorney position in New Jersey, by operation of law, Habba then became the Acting United States Attorney under the FVRA, 5 U.S.C. § 3345(a)(1).

In addition, on Saturday, July 26, a senior Department of Justice official notified the former First Assistant that the President would have removed her from the position of United States Attorney if her judicial appointment to that office had somehow become effective. The notification indicated that, in taking that step, the President was exercising his authority under Article II of the Constitution and 28 U.S.C. § 541(c). The former vests "the executive power in" the President; the latter provides that "each United States Attorney is subject to removal by the President."

Against this backdrop, it seems hard to see the argument that Habba is not currently and validly the U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey. The defendant's argument turns on a single phrase in the FVRA, which he does not bother to quote in his brief. Instead, the defendant represents that the FVRA "explicitly prohibits individuals whose nominations have been submitted to the Senate from serving in an acting capacity for the same office, regardless of subsequent withdrawal of the nomination. 5 U.S.C. § 3345(b)(1)." But let's look at the text of the statute that the defendant fails to quote. The statute provides that an otherwise-qualified individual cannot serve as an Acting U.S. under the FVRA if:

(A) during the 365-day period preceding the date of the death, resignation, or beginning of inability to serve, such person—

…

(ii) served in the position of first assistant to the office of such officer for less than 90 days; and

(B) the President submits a nomination of such person to the Senate for appointment to such office.

5 U.S.C. § 3345(b)(1)(A)–(B) (emphasis added).

To be sure, Habba had been the first assistant for less than 90 days. So her eligibility to serve devolves to the last phrase highlighted above, related to a Presidential nomination.

At the time Habba became the Acting U.S. Attorney, the President had previously withdrawn her nomination. So the statutory question becomes whether the highlighted phrase above should be read as creating a perpetual disability for a person whose nomination was submitted to the position from becoming Acting U.S. Attorney—i.e., should be read as if it were written "the President has submitted a nomination of such person …."—or read as creating a disability for a person whose nomination is pending at the time—i.e., should be read as if it were written "the President is currently submitting a nomination of such person …."

As between these two alternative readings, the later reading (which affirms Habba's appointment) seems like the obvious one. As I explained in my earlier post, the statute's plain language does not create a disability after the President "has submitted" a nomination in the past. Instead, the statute uses the present tense: a disability exists when the President "submits a nomination." Under standard, recommended principles of legislative drafting, the present tense is used "to express all facts and conditions required to be concurrent with the operation of the legal action," as Bryan Garner explains in his excellent treatise, Garner's Dictionary of Legal Usage 536 (3d edition 2011) (emphasis added). After the President withdrew Habba's nomination—i.e., was no longer submitting her nomination—the condition of her nomination being submitted to the Senate was no longer concurrent with her becoming the Acting U.S. Attorney.

The Justice Department has made the same argument, as I recounted earlier. Here's the Department's argument:

The purpose of subsection (b)(1) is to prevent the President from circumventing the Senate's advice-and-consent function by installing a pending nominee for an office on an acting basis before the Senate can act on the nomination. See NLRB v. SW General, Inc., 580 U.S. 288, 295–96 (2017) (tracing history of provision). Accordingly, "if a first assistant is serving as an acting officer under [subsection (a)(1)], he must cease that service if the President nominates him to fill the vacant [Presidentially-appointed, Senate confirmed] office," or else withdraw from nomination. Id. at 301; see Hooks v. Kitsap Tenant Support Servs., Inc., 816 F.3d 550, 558 (9th Cir. 2016) ("Subsection (b)(1) thus precludes someone from continuing to serve as an acting officer after being nominated to the permanent position, unless he or she had been the first assistant for ninety days of the prior year.").

Subsection (b)(1) therefore presupposes a current nomination to an office that is pending before the Senate. Nothing in the FVRA, however, suggests that the mere fact of a past nomination for an office—withdrawn by the President and never considered or acted upon by the Senate—forever bars an individual from serving in that capacity on an acting basis. The statute precludes a person from serving as an acting officer once "the President submits a nomination of such person to the Senate for appointment to such office," 5 U.S.C. 3345(b)(1)(B) (emphasis added); it does not say that the person is barred from such service if the President ever submitted a nomination in the past, or continues to be barred once a nomination is withdrawn. See, e.g., Dole Food Co. v. Patrickson, 538 U.S. 468, 478 (2003) (explaining that a statutory provision "expressed in the present tense" requires consideration of status at the time of the regulated action, not before); Nichols v. United States, 578 U.S. 104, 110 (2016) (same). Indeed, a lifetime ban of that sort would have no logical relationship to the distinct separation-of-powers problem that Congress sought to address in subsection (b)(1): Congress's desire to protect its ability to consider and act upon a pending nomination for an office can hardly be served if no nomination is pending.

In my earlier post, I explained my view that the Department's argument was "powerful." So what does the defendant now say in reply to the Department? Nothing. The defendant's entire reply brief is devoted to teasing out the implications of what happens if Habba were to be in her position improperly. Indeed, nowhere in his reply does the defendant even quote the FVRA's "submits a nomination" language, much less explain why the Department's straightforward interpretation is somehow unreasonable.

Against this backdrop, I expect the defendant's argument will be swiftly rejected. Perhaps his motion has had its desired effect, of attracting headlines about how Habba's appointment has been challenged as unconstitutional and diverting attention attention away from whether the defendant is guilty of the drug dealing crime alleged against him. But the bottom line is that the defendant is asking a court to bar his prosecution under a statutory provision he does not even quote, much less plausibly interpret.

The defendant does refer back to the New Jersey's judges' effort to appoint a person besides Habba as the interim U.S. Attorney. But that argument founders on the fact that judicial authority to appoint an interim U.S. Attorney only exists after the expiration of the 120-day term. Indeed, the New Jersey's judge's order provided that it became effective "upon the expiration of 120 days after appointment by the Attorney General of the Interim U.S, Attorney, Alina Habba." As the chronology recounted above makes clear, there was no expiration of the 120 days. Habba resigned two days before. And even if the judges had somehow effected an appointment of a person besides Habba, the relevant statutes make clear that the President (acting through his Attorney General) can remove that person. Title 28 U.S.C. § 541 specifically provides that "[e]ach United States Attorney is subject to removal by the President." 28 U.S.C. § 541(c). Here again, the defendant does not even cite this provision, much less explain why the President is somehow unable to use it to effectuate his choice to be U.S. Attorney.

To be sure, one can debate whether Habba is well qualified to assume the important position of the U.S. Attorney for the District of Jersey. I take no position on the merits of that issue. And one can also find this entire appointment process to be arcane and hyper-technical--even a "loophole." Perhaps so. But the bottom line is that the President (acting through his Attorney General) has put in place (at least temporarily) an Acting U.S. Attorney that he has confidence in to execute his policies. That seems like the sensible outcome.

The post The Defense Challenge to Alina Habba's Appointment is Weak appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Justice Kavanaugh "Definitely Pay[s] Attention" To the Press

[I am still incredulous that Justice Barrett does not read coverage about herself.]

Justice Kavanaugh spoke at the Eighth Circuit Judicial Conference. He was interviewed by Judge Sarah Pitlyk, who was his former law clerk. (Kavanaugh's clerk tree continues to grow, with President Trump's recent nominations to the Third and Sixth Circuits.)

I have yet to find a video of the event, but there are several press accounts. Politico offers this insight:

Kavanaugh also made clear he closely follows press coverage, podcasts and social media posts about the Supreme Court, what he described as "an ocean of criticism and critiques out there."

"I'm aware of it. I definitely pay attention to it. I think you have to. We're public officials who serve the American people. It's not an academic exercise," said Kavanaugh, who worked as a White House lawyer for President George W. Bush. "It's important for maintaining public confidence in the judiciary and the Supreme Court to know how the opinions are being conveyed and received and understood by the American people."

Oh I bet he does. Indeed, in 2021, the Supreme Court's Public Information Office "clipped approximately 10,000 news articles related to the court and the justices, roughly half of them tweets." The Justices have to go out of their way to not see this content.

I also appreciate that Justice Kavanaugh responded directly to Justice Kagan's missives at the Ninth Circuit Conference about the lack of a written opinion for emergency docket orders.

Kavanaugh . . . said there can be a "danger" in writing those opinions. He said that if the court has to weigh a party's likelihood of success on the merits at an earlier stage in litigation, that's not the same as reviewing their actual success on the merits if the court takes up the case.

"So there could be a risk in writing the opinion, of lock-in effect, of making a snap judgment and putting it in writing, in a written opinion that's not going to reflect the final view," Kavanaugh said.

Kavanaugh is right. More and more, it seems that Justice Kavanaugh is speaking out in defense of what the majority is doing--his opinions in Labrador v. Poe and CASA were extremely important. He has become the explainer in chief! Chief Justice Roberts is content in issuing stern end-of-year messages and trying to cheer up Judge Boasberg at Judicial Conference meetings.

By contrast, in 2022, Justice Barrett said she does not read press coverage about herself.

Let's say I have not ever talked to my clerks about whether they read SCOTUS blog. I would be surprised if most of the law clerks in the building did not. I have a policy of not reading. I read news. I'm not an uninformed person, but I have a policy of trying not to read any coverage that addresses me. I mean, I kind of generally want to know about the court. But I do try not to read like whether they're positive or negative, I think it's not a very good idea to read and consume media, that's about me, because, you know, I think there are personal and institutional reasons for that, you know, the institutional reason is that judges have life tenure, so that they can be insulated from fear of public opinion. And so to read criticisms of the court, I think, undermines that. So you know, you shouldn't be playing to anyone in the public or any kind of constituency, you know, being happy if you make one segment of the public happy, or, you know, reluctant to anger another. . . .

And then on a personal level, you know, it's just not good to have any of that in your head. Certainly not if it's critical and mean. But even if it's high praise, I mean, like, why should you be reading a steady diet? Or my case, it wouldn't really be a steady diet. But why should you be consuming, you know, flattering, you know, articles about yourself, because on a personal level, I mean, the day that I think I am, you know, better than the next person in the grocery store, checkout line, and you know, is a bad day. So, I would say that I really tried to bracket and put aside, you know, anything, you know, to the extent that I can avoid reading, and if it addresses me in particular.

I was incredulous about this statement at the time, and I remain incredulous. Indeed, as Justice Barrett prepares a media blitz for her forthcoming book, I have to imagine she will follow press coverage about herself carefully. Justice Barrett's planned event with Bari Weiss at Lincoln Center seems to have sold out almost immediately.

I am still fond of Justice Scalia's 2013 remarks about his press diet to New York Magazine:

What's your media diet? Where do you get your news?

Well, we get newspapers in the morning.

"We" meaning the justices?

No! Maureen and I.

Oh, you and your wife …

I usually skim them. We just get The Wall Street Journal and the Washington Times. We used to get the Washington Post, but it just … went too far for me. I couldn't handle it anymore.

What tipped you over the edge?

It was the treatment of almost any conservative issue. It was slanted and often nasty. And, you know, why should I get upset every morning? I don't think I'm the only one. I think they lost subscriptions partly because they became so shrilly, shrilly liberal.

So no New York Times, either?

No New York Times, no Post.

And do you look at anything online?

I get most of my news, probably, driving back and forth to work, on the radio.

Not NPR?

Sometimes NPR. But not usually.

Reading the press is not necessarily a bad thing. As Mike Davis observed "Sometimes feeling the heat helps people see the light."

But the president's supporters were delighted by her criticism of Justice Jackson, with some crowing that their earlier attacks on Justice Barrett had succeeded.

"Sometimes feeling the heat helps people see the light," Mike Davis, a right-wing legal activist with close ties to…

— ???????? Mike Davis ???????? (@mrddmia) July 7, 2025

The post Justice Kavanaugh "Definitely Pay[s] Attention" To the Press appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Today's Federal Circuit Oral Argument in Our Tariff Case

[Outcomes are hard to predict. But the judges seemed skeptical of the administration's claim that the president has virtually unlimited power to impose tariffs.]

NA

NA Today, the en banc US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit hear oral arguments in VOS Selections, Inc. v. Trump, the case challenging Trump's massive "Liberation Day" tariffs brought by the Liberty Justice Center and myself on behalf of five small businesses seriously harmed by the tariffs. You can listen to the argument here. Leading appellate litigator and Georgetown law Prof. Neal Katyal argued for us.

The case is consolidated with a similar one brought by twelve state governments, led by Oregon. We are defending a unanimous ruling in our favor by the US Court of International Trade, which held that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) does not grant the president anything approaching unlimited tariff authority, and if it did it would be an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive.

It is difficult to predict case outcomes based on oral arguments, particularly one with eleven judges that have a diversity of views and interests. Still, I can make a few tentative observations.

First, there seems little, if any, support for the idea that IEEPA grants the president unlimited tariff authority of the kind the administration claims. Multiple judges expressed skepticism that the law gives him the authority to rewrite the tariff schedule or to claim "unbounded authority." Several judges emphasized, as Judge Reyna noted, that "IEEPA doesn't even mention the word tariffs." From the beginning of this litigation, we have emphasized that IEEPA delegates authority to "regulate" importation, but regulation is distinct from taxation.

Even if IEEPA does allow some tariff authority, as the predecessor court to Federal Circuit ruled in United States v. Yoshida International Inc. (1975), with respect to the Trading with the Enemy Act (predecessor statute for IEEPA), it doesn't follow that authority is unlimited. Yoshida held it was not endorsing unlimited tariff authority. It emphasized that the Nixon tariffs were linked to the preexisting tariff schedule set by Congress, and that "[t]he declaration of a national emergency is not a talisman enabling the President to rewrite the tariff schedules." It even noted that to "sanction the exercise of an unlimited [executive] power" to impose tariffs "would be to strike a blow to our Constitution." A number of judges noted today that, if Yoshida applies to IEEPA (thereby authorizing some tariffs), so too do its limitations on the scope of permissible tariff authority.

Some judges also suggested that unconstrained tariff authority would run afoul of the major questions doctrine and constitutional constraints on delegation of legislative power to the executive. The CIT based its ruling in part on these considerations.

Even if IEEPA does allow the use of tariffs, the law can only be invoked in the event of an "emergency" that poses an "unusual and extraordinary threat" to the US economy and national security. Those judges who raised this issue seemed skeptical of claims that what qualifies and an "unusual and extraordinary threat" is left to the unreviewable discretion of the president. Otherwise, IEEPA (assuming it allows tariffs at all) would be a blank check for the president, thereby exacerbating major questions and nondelegation problems.

There is nothing unusual or extraordinary about trade deficits, the supposed threat targeted by the Liberation Day tariffs. We have had them for decades, and today's deficits are well in line with historical norms.

A number of judges raised an issue that was given little consideration by the lower court, and in briefing by the parties: even if trade deficits are not an "unusual and extraordinary threat," perhaps some of their supposed consequences do. Those possible effects include damage to US manufacturing, decline of the defense industrial base or the like.

Claims that trade damages US manufacturing and defense industries are - like trade deficits - far from unusual. Protectionists have advanced such arguments for decades. Far from atrophying or "hollowing out," US manufacturing output has actually grown in recent decades, nearly doubling since 1997. While it has declined as a percentage of GDP, that's largely because other industries (such as services) have grown even more. Perhaps we should have still more manufacturing. But there is nothing "unusual and extraordinary" about its current level. Whatever danger trade deficits pose to manufacturing or defense is not an unusual and extraordinary threat, but a normal policy issue that cannot be addressed through a statute limited to emergency situations. Moreover, as the amicus brief by leading economists points out, trade deficits, as such do not cause decline in manufacturing.

Finally, it is worth noting that IEEPA only authorizes measures that "deal with" the emergency and unusual and extraordinary threat that justifies its invocation. Trump's imposition of 10% or higher tariffs on virtually every nation in the world goes far beyond merely targeting imports that might plausibly be said to undermine manufacturing or defense.

In sum, it is hard to predict what exactly the Federal Circuit will do here. But I am tentatively optimistic that the court will at least reject claims that IEEPA gives the president virtually unlimited, unreviewable tariff authority.

The post Today's Federal Circuit Oral Argument in Our Tariff Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] My New Dispatch Article on Judicial Review of Emergency Powers

[It makes the case for strong judicial review of executive invocations of sweeping emergency powers.]

NA

NA Today, The Dispatch published my article "Not Everything is an Emergency" (gift link). Here is an excerpt:

The Trump administration has attempted to make sweeping use of emergency powers in the areas of immigration, trade, and domestic use of the military. In each case, President Donald Trump has tried to use powers legally reserved for extreme exigencies—invasion, war, grave threats to national security—to address essentially normal political challenges. If he is allowed to get away with them, these abuses would set dangerous precedents and gravely threaten civil liberties and the structure of our constitutional system.

Each of these efforts has resulted in litigation, and in each case the administration claims the issues in question are left to virtually unreviewable executive discretion. The president alone supposedly gets to determine whether an emergency exists and (with few or no limitations) what should be done about it. Courts have mostly rejected the argument that the president has the power to define terms such as "invasion." But they have often been overly deferential to presidential determinations about relevant facts, such as whether an "invasion" (correctly defined) has actually occurred. At least one judge has also embraced the view that these issues are unreviewable "political questions." It is vital that courts engage in full, nondeferential review of administration invocations of emergency powers. None of the arguments against doing so outweigh the immense dangers of letting the president invoke these powers at will…..

The Trump administration has attempted to make sweeping use of emergency powers in the areas of immigration, trade, and domestic use of the military. In each case, President Donald Trump has tried to use powers legally reserved for extreme exigencies—invasion, war, grave threats to national security—to address essentially normal political challenges. If he is allowed to get away with them, these abuses would set dangerous precedents and gravely threaten civil liberties and the structure of our constitutional system.

Each of these efforts has resulted in litigation, and in each case the administration claims the issues in question are left to virtually unreviewable executive discretion. The president alone supposedly gets to determine whether an emergency exists and (with few or no limitations) what should be done about it. Courts have mostly rejected the argument that the president has the power to define terms such as "invasion." But they have often been overly deferential to presidential determinations about relevant facts, such as whether an "invasion" (correctly defined) has actually occurred. At least one judge has also embraced the view that these issues are unreviewable "political questions." It is vital that courts engage in full, nondeferential review of administration invocations of emergency powers. None of the arguments against doing so outweigh the immense dangers of letting the president invoke these powers at will….

Nondeferential judicial review of invocations of emergency powers is an application of the judiciary's normal role in interpreting the law and applying it to the relevant facts. Moreover, the use of terms denoting extraordinary dangers (such as "invasion," "rebellion," or "emergency") counsels against interpreting them in ways that allow invocation of these powers in normal times. Otherwise, these words become superfluous, and emergency powers turn into blank checks for executive power grabs.

The same point applies to factual deference. Courts routinely assess whether the factual prerequisites for applying a law are present. Emergency powers should not be an exception. Otherwise, the government could get around constitutional and other constraints on its authority simply by engaging in lying and misrepresentation about the facts on the ground.

In litigation over all three of its major invocations of emergency powers—immigration, tariffs, and domestic use of the military—the administration has also invoked the "political questions" doctrine, which holds that some issues are off limits to the judiciary, because they have been left to the political process…. But there is no general principle holding that invocations of emergency powers are exempt from judicial scrutiny….

Some defenders of the administration's position argue that courts should defer to the executive's specialized expertise on emergency power issues. But a genuine emergency does not require much expertise to detect. You don't have to be an expert to understand that Russia's assault on Ukraine is an "invasion" or that the COVID pandemic was an "emergency." The very enormity of true emergencies generally makes detection easy.

In rare cases where specialized knowledge is required, courts can take expert testimony and consider scientific evidence, as they routinely do in other situations. Courts also have procedures for considering classified information, when necessary….

Elsewhere in the article, I discuss the enormous issues at stake in cases involving dubious invocations of emergency powers:

Advocates of judicial deference claim it is important to give the president discretion to combat threats. But the enormous risks such deference poses easily outweigh any possible advantage of increased executive flexibility. If illegal migration and drug smuggling qualify as an "invasion," the federal government, under the Constitution, could suspend the writ of habeas corpus whenever it wants, thereby gaining the authority to detain people without due process or filing charges. If properly invoked, the AEA allows detention and deportation even of legal immigrants.

In addition, the weak due process protections mean U.S. citizens may get ensnared in the process, as often happens even with ordinary deportations….

Likewise, normalizing domestic use of the military poses obvious dangers to civil liberties and social order. Routine use of the military for such purposes is a grave menace, and a hallmark of authoritarian regimes.

The stakes with Trump's IEEPA tariffs are also very high. If not struck down, they are expected to impose some $1.9 trillion in tax increases on Americans over the next decade, costing the average household some additional $1,000 per year, while also raising prices and greatly diminishing economic growth. In addition, giving one man total control over tariffs undermines the rule of law and the expectations of stability on which the international economy depends.

The post My New Dispatch Article on Judicial Review of Emergency Powers appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Justice Kavanaugh on the Peril of Writing Shadow Docket Opinions

[Rushing out opinions can lock in erroneous conclusions and create problematic precedent.]

Speaking at the Eighth Circuit Judicial Conference this week, Justice Brett Kavanaugh addressed concerns about the Supreme Court's failure to issue opinions with "shadow docket" orders. While explanatory opinions could be useful, he explained, rushing out opinions could increase the risk of error.

Kavanaugh . . . said there can be a "danger" in writing those opinions. He said that if the court has to weigh a party's likelihood of success on the merits at an earlier stage in litigation, that's not the same as reviewing their actual success on the merits if the court takes up the case.

"So there could be a risk in writing the opinion, of lock-in effect, of making a snap judgment and putting it in writing, in a written opinion that's not going to reflect the final view," Kavanaugh said.

Kavanaugh said members of the court have differing thoughts on when to issue opinions for those cases on the so-called shadow docket, or when parties petition the justices for emergency relief on rulings made by lower courts. He said those cases will "get back to us soon enough."

Adam Liptak of the New York Times reports further:

Justice Kavanaugh said presidents of both parties were to blame. "Executive branches of both parties over the last 20 years have been increasingly trying to issue executive orders and regulations that achieve the policy objectives of the president in power," he said. Those actions give rise to challenges that can race to the Supreme Court. . . .

Emergency applications present the court with difficult issues, Justice Kavanaugh said.

"What is the status of the new regulation or executive order for the next two years?" he asked. "That itself is a very important question, and that's the question we often have to decide: Will the new regulation be in effect or not be in effect in the next two years?" . . .

In opening remarks, without referring to Mr. Trump's attacks on the federal judiciary, Justice Kavanaugh thanked the assembled judges for their service and urged them "to preserve what I think is the crown jewel of our constitutional democracy, which is the independence of the judiciary."

As Liptak also reports, Justice Elena Kagan made the case for explaining such orders at the Ninth Circuit's judicial conference last week.

In a similar appearance last week at the Ninth Circuit's judicial conference, Justice Elena Kagan, who has often dissented from the court's emergency rulings in favor of President Trump, made the opposite case, saying the majority should do more to explain its reasoning.

"I think as we have done more and more on this emergency docket, there becomes a real responsibility that I think we didn't recognize when we first started down this road, to explain things better," Justice Kagan said. "I think that we should hold ourselves, sort of on both sides, to a standard of explaining why we're doing what we're doing."

The post Justice Kavanaugh on the Peril of Writing Shadow Docket Opinions appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] UCLA Stipulates to Permanent Injunction as to Alleged Exclusion of Jewish or Pro-Israel Students from Parts of Campus [UPDATE: + $6M Payment]

[UPDATE 7/31/2025 12:09 pm: The agreement also apparently includes an over $6M payment by UC; according to the N.Y. Times (Anemona Hartocollis), "The settlement, which still has to receive final approval from a judge, would give $50,000 to each of the named plaintiffs, including two law students, one undergraduate and one medical school professor. It would distribute $2.33 million among eight nonprofits, including Hillel at UCLA, the Anti-Defamation League and Chabad House at UCLA; $320,000 to a U.C.L.A. account dedicated to combating antisemitism; and the rest to costs and legal fees."]

From today's proposed stipulated judgment in Frankel v. Regents (C.D. Cal.):

a. The Regents of the University of California, President of the University of California, the Chancellor of UCLA, the Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost of UCLA, the Administrative Vice Chancellor of UCLA, the Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs of UCLA, and the Associate Vice Chancellor for Campus and Community Safety of UCLA—in their official capacities (collectively, the "Enjoined Parties")—are enjoined from offering any of UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas to students, faculty, and/or staff if the Enjoined Parties know the ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas are not fully and equally accessible to Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff.

b. The Enjoined Parties are prohibited from knowingly allowing or facilitating the exclusion of Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff from ordinarily available portions of UCLA's programs, activities, and/or campus areas, whether as a result of a de-escalation strategy or otherwise.

c. For purposes of this order, all references to the exclusion of Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff shall include exclusion of Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff based on religious beliefs concerning the Jewish state of Israel.

d. Nothing in this order prevents the Enjoined Parties from excluding any student, faculty member, or staff member, including Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff, from ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas pursuant to UCLA code of conduct standards applicable to all UCLA students, faculty, and/or staff.

e. Nothing in this order requires the Enjoined Parties to immediately cease providing medical treatment at hospital and medical facilities, fire department services, and/or police department services. However, the Enjoined Parties remain obligated to take all necessary steps to ensure that such services and facilities remain fully and equally open and available to Jewish students, faculty, and/or staff.

Here's the backstory, from my post a year ago about the preliminary injunction in the case:

[* * *]

From [the] order by Judge Mark Scarsi (C.D. Cal.) in Frankel v. Regents:

In the year 2024, in the United States of America, in the State of California, in the City of Los Angeles, Jewish students were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith. This fact is so unimaginable and so abhorrent to our constitutional guarantee of religious freedom that it bears repeating, Jewish students were excluded from portions of the UCLA campus because they refused to denounce their faith. UCLA does not dispute this. Instead, UCLA claims that it has no responsibility to protect the religious freedom of its Jewish students because the exclusion was engineered by third-party protesters. But under constitutional principles, UCLA may not allow services to some students when UCLA knows that other students are excluded on religious grounds, regardless of who engineered the exclusion….

On April 25, 2024, a group of pro-Palestinian protesters occupied a portion of the UCLA campus known as Royce Quad and established an encampment. Royce Quad is a major thoroughfare and gathering place and borders several campus buildings, including Powell Library and Royce Hall. The encampment was rimmed with plywood and metal barriers. Protesters established checkpoints and required passersby to wear a specific wristband to cross them. News reporting indicates that the encampment's entrances were guarded by protesters, and people who supported the existence of the state of Israel were kept out of the encampment. Protesters associated with the encampment "directly interfered with instruction by blocking students' pathways to classrooms."

Plaintiffs are three Jewish students who assert they have a religious obligation to support the Jewish state of Israel. Prior to the protests, Plaintiff Frankel often made use of Royce Quad. After protesters erected the encampment, Plaintiff Frankel stopped using the Royce Quad because he believed that he could not traverse the encampment without disavowing Israel. He also saw protesters attempt to erect an encampment at the UCLA School of Law's Shapiro courtyard on June 10, 2024.

Similarly, Plaintiff Ghayoum was unable to access Powell Library because he understood that traversing the encampment, which blocked entrance to the library, carried a risk of violence. He also canceled plans to meet a friend at Ackerman Union after four protesters stopped him while he walked toward Janss Steps and repeatedly asked him if he had a wristband. Plaintiff Ghayoum also could not study at Powell Library because protesters from the encampment blocked his access to the library.

And Plaintiff Shemuelian also decided not to traverse Royce Quad because of her knowledge that she would have to disavow her religious beliefs to do so. The encampment led UCLA to effectively make certain of its programs, activities, and campus areas available to other students when UCLA knew that some Jewish students, including Plaintiffs, were excluded based of their genuinely held religious beliefs.

The encampment persisted for a week, until the early morning of May 2, when UCLA directed the UCLA Police Department and outside law enforcement agencies to enter and clear the encampment. Since UCLA dismantled the encampment, protesters have continued to attempt to disrupt campus. For example, on May 6, protesters briefly occupied areas of the campus. And on May 23, protesters established a new encampment, "erecting barricades, establishing fortifications and blocking access to parts of the campus and buildings," and "disrupting campus operations."

Most recently, on June 10, protesters "set up an unauthorized and unlawful encampment with tents, canopies, wooden shields, and water-filled barriers" on campus. These protesters "restricted access to the general public" and "disrupted nearby final exams." Some students "miss[ed] finals because they were blocked from entering classrooms," and others were "evacuated in the middle" of finals.

Based on these facts and other allegations, Plaintiffs assert claims for violations of their federal constitutional rights, including violation of the Equal Protection Clause, the Free Speech Clause, and the Free Exercise Clause; claims for violations of their federal civil rights, including violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, conspiracy to interfere with civil rights, and failure to prevent conspiracy; claims for violations of their state constitutional rights, including violation of the California Equal Protection Clause and the California Free Exercise Clause; and claims for violations of their state civil rights, including violations of section 220 of the California Education Code, the Ralph Civil Rights Act of 1976, and the Bane Civil Rights Act….

The court rejected UCLA's standing objections, in part reasoning:

UCLA argues that Plaintiffs lack standing because they fail to allege an imminent likelihood of future injury…. UCLA contends that its remedial actions following the Royce Quad encampment make any "future injury speculative at best." These actions include the creation of a new Office of Campus Safety and the transfer of day-to-day responsibility for campus safety to an Emergency Operations Center. The changes, while commendable, do not minimize the risk that Plaintiffs "will again be wronged" by their exclusion from UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas based on their sincerely held religious beliefs below "a sufficient likelihood."

First, since UCLA's changes, protesters have violated UCLA's protest rules at least three times: on May 6, May 23, and June 10. While these events may not have been as disruptive as the Royce Quad encampment, according to a UCLA email, the June 10 events "disrupted final exams," temporarily blocked off multiple areas of campus, and persisted from 3:15 p.m. to the evening. Similarly, also according to UCLA emails, the May 6 and 23 events disrupted access to several campus areas. Further, any relative quiet on UCLA's campus the past few months is belied by the facts that fewer people are on a university campus during the summer and that the armed conflict in Gaza continues.

Finally, while UCLA's focus on safety is compelling, UCLA has failed to assuage the Plaintiffs' concerns that some Jewish students may be excluded from UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas based on their sincerely held religious beliefs should exclusionary encampments return. In response to these concerns raised at the hearing, UCLA did "not state[] affirmatively that" they "will not" provide ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas to non-Jewish students if protesters return and exclude Jewish students.

It remains to be seen how effective UCLA's policy changes will be with a full campus. While the May and June protests do not appear to have resulted in the same religious-belief-based exclusion as the prior encampment that gives rise to the Plaintiffs' free exercise concerns, the Court perceives an imminent risk that such exclusion will return in the fall with students, staff, faculty, and non-UCLA community members. As such, given that when government action "implicates First Amendment rights, the inquiry tilts dramatically toward a finding of standing," the Court finds that Plaintiffs have sufficiently shown an imminent likelihood of future injury for standing purposes….

And the court concluded that plaintiffs were likely to succeed on their Free Exercise Clause claim (and thus declined to consider any of the other claims):

The Free Exercise Clause … "'protect[s] religious observers against unequal treatment' and subjects to the strictest scrutiny laws that target the religious for 'special disabilities' based on their 'religious status.'" "[A] State violates the Free Exercise Clause when it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits." …

Here, UCLA made available certain of its programs, activities, and campus areas when certain students, including Plaintiffs, were excluded because of their genuinely held religious beliefs. For example, Plaintiff Frankel could not walk through Royce Quad because entering the encampment required disavowing the state of Israel. Similarly, Plaintiff Ghayoum was prevented from entering a campus area at a protester checkpoint, and Plaintiff Shemuelian could not traverse Royce Quad, unlike other students…. Plaintiffs' exclusion from campus resources while other students retained access raises serious questions going to the merits of their free exercise claim….

Plaintiffs have put forward a colorable claim that UCLA's acts violated their Free Exercise Clause rights. Further, given the risk that protests will return in the fall that will again restrict certain Jewish students' access to ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas, the Court finds that Plaintiffs are likely to suffer an irreparable injury absent a preliminary injunction…….

Under the Court's injunction, UCLA retains flexibility to administer the university. Specifically, the injunction does not mandate any specific policies and procedures UCLA must put in place, nor does it dictate any specific acts UCLA must take in response to campus protests. Rather, the injunction requires only that, if any part of UCLA's ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas become unavailable to certain Jewish students, UCLA must stop providing those ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas to any students. How best to make any unavailable programs, activities, and campus areas available again is left to UCLA's discretion….

The court therefore issued the following order:

[1.] Defendants Drake, Block, Hunt, Beck, Gordon, and Braziel ("Defendants") are prohibited from offering any ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas to students if Defendants know the ordinarily available programs, activities, or campus areas are not fully and equally accessible to Jewish students.

[2.] Defendants are prohibited from knowingly allowing or facilitating the exclusion of Jewish students from ordinarily available portions of UCLA's programs, activities, and campus areas, whether as a result of a de-escalation strategy or otherwise.

[3.] On or before August 15, 2024, Defendants shall instruct Student Affairs Mitigator/Monitor ("SAM") and any and all campus security teams (including without limitation UCPD and UCLA Security) that they are not to aid or participate in any obstruction of access for Jewish students to ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas.

[4.] For purposes of this order, all references to the exclusion of Jewish students shall include exclusion of Jewish students based on religious beliefs concerning the Jewish state of Israel.

[5.] Nothing in this order prevents Defendants from excluding Jewish students from ordinarily available programs, activities, and campus areas pursuant to UCLA code of conduct standards applicable to all UCLA students.

[6.] Absent a stay of this injunction by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, this preliminary injunction shall take effect on August 15, 2024, and remain in effect pending trial in this action or further order of this Court or the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

The court also noted:

[T]his case [is not] about the content or viewpoints contained in any protest or counterprotest slogans or other expressive conduct, which are generally protected by the First Amendment. See Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 358 (2003) ("The hallmark of the protection of free speech is to allow 'free trade in ideas'—even ideas that the overwhelming majority of people might find distasteful or discomforting." (quoting Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting)); see also Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 414 (1989) ("If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.").

Amanda G. Dixon, Richard C. Osborne, Eric C. Rassbach, Mark L. Rienzi, Laura W. Slavis, and Jordan T. Varberg (Becket Fund), Erin E. Murphy, Matthew David Rowen, and former U.S. Solicitor General Paul Clement (Clement & Murphy, LLC), and Elliot Moskowitz, Marc J. Tobak, and Adam M. Greene (Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP) represent plaintiffs.

The post UCLA Stipulates to Permanent Injunction as to Alleged Exclusion of Jewish or Pro-Israel Students from Parts of Campus [UPDATE: + $6M Payment] appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "If Doe Wishes to Use Judicial Proceedings" "to Seek Relief from … Defamat[ion],"

["he must do so under his true name and accept the risk that certain unflattering details may come to light over the course of the litigation."]

From Judge John J. Tharp, Jr. (N.D. Ill.) in yesterday's Doe v. Ahrens:

Plaintiff John Doe has filed this suit against defendant Valery J. Ahrens, alleging that after the two engaged in a long-distance, casual relationship, conducted largely online and over the phone, Ahrens began stalking and harassing him. Doe, who describes himself in the Amended Complaint as "a self-made entrepreneur, author, internet personality, [] venture capitalist … [and] a dedicated and loving father," alleges that Ahrens sent him non-stop messages and created various social media accounts for the purpose of publishing false and unflattering information about him, often engaging with his followers to direct them to these accounts.

Further, Doe alleges that Ahrens broadcast certain private, sexual telephone exchanges between the two that, Doe says, he did not know she was recording. Doe claims these actions amount to defamation per se, false light invasion of privacy, public disclosure of private facts, and intentional infliction of emotional distress under state law, and has invoked diversity jurisdiction for his federal suit.

With his complaint, Doe filed a motion to proceed under a pseudonym, arguing that given her past behavior, Ahrens is likely to "weaponize" this case and any filings therein to "exacerbate" the harm she has already allegedly inflicted on Doe. Doe argues that given the sensitivity of Ahrens's posts about Doe, and the fact that the "veracity" of those posts will be central to his defamation claims, he should be allowed to pursue his claims without further damaging his reputation.

"The norm in federal litigation is that all parties' names are public." This is because judicial proceedings are public and "[i]dentifying the parties to the proceedings is an important dimension of publicness. The people have a right to know who is using their courts." Departures from that norm are justified in cases involving, for example, parties who are minors or who have reason to fear physical harm or retaliation by third parties as a result of the litigation. Pseudonyms may also be allowed in cases involving victims of sex crimes.

The Seventh Circuit has "held that a desire to keep embarrassing information secret does not justify anonymity." … "[F]ear of stigmatization and a desire not to reveal intimate details were not enough to justify anonymity for the plaintiff." . . . Moreover, "the Seventh Circuit generally opposes allowing sexual harassment claimants to proceed anonymously."

In his motion and reply brief, Doe argues that this case is "exceptional" due to Ahrens's extreme, prolific, and long-running efforts to publicly defame and embarrass him. Even after Doe filed his complaint, he alleges, Ahrens threatened to publicize their phone and video calls, intervened in his personal relationships, posted about Doe online (using his real name and photo), and even lodged an unsuccessful complaint against Doe's counsel with the Attorney Registration and Disciplinary Committee. For the purposes of weighing the merits of Doe's motion, the Court will assume the truth of these allegations.

Doe believes that revealing his name "will embolden Ahrens to disseminate every public filing and discovery response filed or exchanged in this litigation" while "hid[ing] behind the litigation privilege and craft[ing] pleadings designed to inflict greater mental distress and deter Plaintiff from continuing to seek redress[.]"Doe in fact separately moved for a protective order pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c), which the Court granted in part by ordering any materials filed by the parties related to the communications recorded (whether video or audio) by Ahrens to be filed under seal.

The problem for Doe is that the potential harms he identifies are not the sort which are appropriately remedied by proceeding under a pseudonym. Doe fears that Ahrens will use this litigation—the fact of its existence, and any filings made therein—in her continued campaign against him, causing him further reputational and emotional damage. But the Seventh Circuit has been quite clear that reputational harm alone is not an adequate justification for proceeding anonymously. And Doe has not offered any other specific consequence he fears will befall him if his name is made public in connection with this litigation other than that potential reputational harm. Only "[a] substantial risk of harm—either physical harm or retaliation by third parties, beyond the reaction legitimately attached to the truth of events as determined in court—may justify anonymity."

Further, while not bound to follow it, the Court finds persuasive the reasoning set forth in Doe v. Doe (4th Cir. 2023), a decision from the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit highlighted by the intervenor in this case, Eugene Volokh, an academic and journalist. In its ruling, the Fourth Circuit affirmed a denial of a plaintiff's motion to proceed under a pseudonym in a defamation case:

[W]e fail to see how Appellant can clear his name through this lawsuit without identifying himself. If Appellant were successful in proving defamation, his use of a pseudonym would prevent him from having an order that publicly "clears" him. It is apparent that Appellant wants to have his cake and eat it too. Appellant wants the option to hide behind a shield of anonymity in the event he is unsuccessful in proving his claim, but he would surely identify himself if he were to prove his claims.

If Doe wishes to use judicial proceedings against Ahrens—who is publicly named in this case—to seek relief from her allegedly defamatory and harassing behavior, he must do so under his true name and accept the risk that certain unflattering details may come to light over the course of the litigation.

This is not to say that Doe has no recourse to protect himself if he fears that Ahrens will continue to post about him or broadcast illicitly recorded conversations. Doe has already sought a protective order pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c), which the Court granted in part by directing any materials related to the contents of communications (whether audio or video) recorded by the Ahrens to be filed under seal. That order will remain in place for now, as the parties proceed into discovery. Doe is also free to seek preliminary injunctive relief against Ahrens if, as he indicates in his reply brief, he believes he is at imminent risk of further defamation by Ahrens. But he must seek any relief against Ahrens under his true name….

The post "If Doe Wishes to Use Judicial Proceedings" "to Seek Relief from … Defamat[ion]," appeared first on Reason.com.

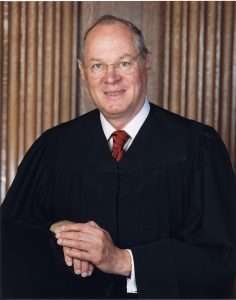

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: July 31, 2018

7/31/2018: Justice Anthony Kennedy retired.

Justice Anthony Kennedy

Justice Anthony Kennedy

The post Today in Supreme Court History: July 31, 2018 appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers