Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 42

September 5, 2025

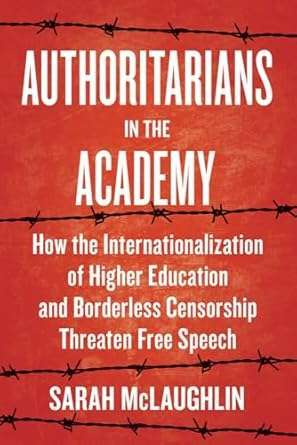

[Eugene Volokh] Sarah McLaughlin (FIRE) on "Authoritarians in the Academy: How the Internationalization of Higher Education and Borderless Censorship Threaten Free Speech,"

I'm delighted to report that Sarah McLaughlin (of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression) will be guest-blogging this coming week about her new book. From the publisher's summary:

A revealing exposé on how foreign authoritarian influence is undermining freedom and integrity within American higher education institutions.

In an era of globalized education, where ideals of freedom and inquiry should thrive, an alarming trend has emerged: foreign authoritarian regimes infiltrating American academia. In Authoritarians in the Academy, Sarah McLaughlin exposes how higher education institutions, long considered bastions of free thought, are compromising their values for financial gain and global partnerships.

This groundbreaking investigation reveals the subtle yet sweeping influence of authoritarian governments. University leaders are allowing censorship to flourish on campus, putting pressure on faculty, and silencing international student voices, all in the name of appeasing foreign powers. McLaughlin exposes the troubling reality where university leaders prioritize expansion and profit over the principles of free expression. The book describes incidents in classrooms where professors hesitate to discuss controversial topics and in boardrooms where administrators weigh the costs of offending oppressive regimes. McLaughlin offers a sobering look at how the compromises made in American academia reflect broader societal patterns seen in industries like tech, sports, and entertainment….

And here are the jacket blurbs:

As universities globalize, authoritarian regimes export censorship to American campuses. In Authoritarians in the Academy, Sarah McLaughlin unsparingly exposes how foreign pressure, self-censorship, and administrative complicity threaten academic freedom―challenging the notion that universities remain safe havens for open debate. A timely warning from the front lines of global free expression.

―Jacob Mchangama, Executive Director of The Future of Free Speech and author of Free Speech: a History from Socrates to Social MediaEssential reading for understanding how authoritarians abroad are limiting the freedom to think, teach, and learn at US universities. McLaughlin expertly shows how the sensitivity discourse prevalent on campuses is invoked to serve the censorious impulses of foreign regimes. With authoritarianism ascendant at home, this book is even more relevant.

―Amna Khalid, Carleton CollegeAuthoritarians in the Academy uncovers an alarming truth: oppressive governments are silencing their critics on campus, even those half a world away and in countries that protect campus free speech, including the United States. Beyond the students and faculty members who are directly targeted, the resulting chill stifles others and deprives all campus community members of the opportunity to hear suppressed information and ideas. This book is an urgent call to protect dissidents and dissent in higher education.

―Nadine Strossen, former president, American Civil Liberties Union; author of Free Speech: What Everyone Needs to KnowAuthoritarians in the Academy is one of those books that turns over a lot of rocks, exposing the unpleasant things going on underneath… The book deserves a wide readership.

―National Review

The post Sarah McLaughlin (FIRE) on "Authoritarians in the Academy: How the Internationalization of Higher Education and Borderless Censorship Threaten Free Speech," appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] $7500 Sanctions for Nonexistent Citations in Brief; Magistrate Judge Stresses Cite-Checking Isn't a New Obligation

["Whether a case cite is obtained from a law review article, a hornbook, or through independent legal research, the duty to ensure that any case cited to a court is "good law" is nearly as old as the practice of law."]

From the Report and Recommendation in Davis v. Marion County Superior Court Juvenile Detention Center, filed Tuesday by Magistrate Judge Mark Dinsmore (S.D. Ind.):

In [a] brief, Mr. Sture included two citations that he concedes do not exist….Mr. Sture acknowledged that he was responsible for the errors in the brief that he signed and filed. However, he took the position that the main reason for the errors in his brief was the short deadline (three days) he was given to file it. He explained that, due to the short timeframe and his busy schedule, he asked his paralegal (who once was, but is not currently, a licensed attorney) to draft the brief, and Mr. Sture did not have time to carefully review the paralegal's draft before filing it.

[The Magistrate Judge briefly explained the reason for the unusually short deadline, and noted that, "while Mr. Sture did only have three days to file his response after the motion to compel was filed, he had much more time than that to consider and research the issues that were ultimately addressed in the response brief"; for more on that, read the full opinion. -EV]

Further, while Mr. Sture made much at the hearing about the fact that he filed his response brief literally at the eleventh hour (the brief was, in fact, filed at 11:00 p.m. on the due date), he further represented that he subscribes to LEXIS. It would have taken only a few minutes to check the validity of the citations in the brief using LEXIS before filing it.

Mr. Sture failed to take even that most basic of actions, and therefore did not catch the fact that the brief contained citations that did not exist. The most logical explanation for the citation to non-existent authority is, of course, the use of generative AI to conduct legal research and/or draft the brief. The issue of "hallucinated case[s] created by generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT and Google Bard" has been "widely discussed by courts grappling with fictitious legal citations and reported by national news outlets."

The paralegal who drafted the brief did not appear at the hearing. Mr. Sture represented at the hearing that the paralegal did not use generative AI to aid in the drafting of the brief; rather, she told Mr. Sture that she used a legal research product called Fastcase. However, neither Mr. Sture nor the paralegal provided any alternative explanation for the erroneous citations. Further, whether generative AI was or was not used to draft the brief is not particularly relevant to the analysis. There is nothing fundamentally improper in the use of AI tools to draft a brief. Rather, it is counsel's abdication of his responsibility to ensure that the information he provided to the Court was accurate that is the basis for the sanctions recommended….

Courts have consistently held for decades that failing to check the treatment and soundness—let alone the existence—of a cited case warrants sanctions. See, e.g., Salahuddin v. Coughlin, 999 F. Supp. 526, 529 (S.D.N.Y. 1998) (noting that Shepardizing would have led defense counsel to a key case); Brown v. Lincoln Towing Serv., No. 88C0831, 1988 WL 93950 (N.D. Ill. 1988) (imposing sanctions where the attorney filed a claim based on an expired federal statute); Pravic v. U.S. Indus.-Clearing, 109 F.R.D. 620, 623 (E.D. Mich. 1986) (holding that the act of relying on another attorney's memorandum without Shepardizing the cases cited warranted sanctions); Blake v. Nat'l Cas. Co., 607 F. Supp. 189, 191 (C.D. Ca. 1984) (noting that Shepardizing cases already cited would have led to controlling authority).

The advent of modern legal research tools implementing features such as Westlaw's KeyCite and Lexis's Shephardization has enabled attorneys to easily fulfill this basic duty, and there is simply no reason for an attorney to fail to do so. Such has been the view for decades: "It is really inexcusable for any lawyer to fail, as a matter of routine, to Shepardize all cited cases (a process that has been made much simpler today than it was in the past, given the facility for doing so under Westlaw or LEXIS)." Gosnell v. Rentokil, Inc., 175 F.R.D. 508, 510 n.1 (N.D. Ill. 1997). Confirming that a case is good law is a basic, routine matter and something that is expected from a practicing attorney. As noted in the case of an expert witness, an individual's "citation to fake, AI-generated sources … shatters his credibility." See Kohls v. Ellison, 2025 WL 66514, at (D. Minn. Jan. 10, 2025). The same is true even if the fake citations were generated without the knowing use of AI.

Mr. Sture admits that he did not make the requisite reasonable inquiry into the law before filing his brief. Whether or not AI was the genesis of the non-existent citations, Mr. Sture's failure to review them before submitting them to the court was a violation of Rule 11. See Hayes, 763 F. Supp. 3d at 1066-67 ("The Court need not make any finding as to whether Mr. Francisco actually used generative AI to draft any portion of his motion and reply, including the fictitious case and quotation…. Citing nonexistent case law or misrepresenting the holdings of a case is making a false statement to a court. It does not matter if generative AI told you so.") (citations and quotations marks omitted).

The fact that Mr. Sture did not file the brief with the intention of deceiving the court does not excuse his failure to check the citations therein. Whether a case cite is obtained from a law review article, a hornbook, or through independent legal research, the duty to ensure that any case cited to a court is "good law" is nearly as old as the practice of law. As previously noted, the development of resources such as the Shephard's citation system provided lawyers a tool to accomplish that most basic of tasks. {Frank Shepard introduced his print citation index in the 1870s, though other precursor citation series had existed since the early nineteenth century. See Laura C. Dabney, Citators: Past, Present, and Future, 27 Legal Reference Servs. Q. 165, 166 (2008).} It is Mr. Sture's failure to comply with that most basic of requirements that makes his conduct sanctionable.

The Undersigned finds that Mr. Sture violated Rule 11 and that sanctions for that violation are appropriate…. Monetary sanctions ranging from $2,000 to $6,000 have been imposed in similar contexts in the past few years. Given the distressing number of cases calling out similar conduct since the opinions cited above were issued, it is clear that the imposition of modest sanctions has failed to act as a deterrent. {The Undersigned's very quick, certainly non-exhaustive search revealed at least eleven cases noting fictitious citations (to either non-existent cases or non-existent quotations) in federal court filings in the month of August 2025 alone. While most of these cases involved filings by pro se litigants, three of them … involved filings by attorneys.} Accordingly, the Undersigned RECOMMENDS that Mr. Sture be sanctioned $7,500.00 for his Rule 11 violations in this case….

The Magistrate Judge also referred "the matter of Mr. Sture's misconduct in this case to the Chief Judge pursuant to Local Rule of Disciplinary Enforcement 2(a) for consideration of any further discipline that may be appropriate."

The post $7500 Sanctions for Nonexistent Citations in Brief; Magistrate Judge Stresses Cite-Checking Isn't a New Obligation appeared first on Reason.com.

[John Ross] Short Circuit: An Inexhaustive Weekly Compendium of Rulings from the Federal Courts of Appeal

[Predatory incursion, financial fraud, and taking your gun to a fandango.]

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

New cert petition! According to the Alaska Supreme Court, it's a-okay to forfeit bush pilot Ken Jouppi's $95,000 airplane over a passenger's six-pack of Budweiser. According to us, that's wrong. And sharpens a division among the state and federal courts. And is a compelling candidate for Supreme Court review. Sit back, relax, and enjoy this breezy read about the most excessively fine clause in the Constitution.

In March 2025, the EPA cancels "Green New Deal" grants for clean-energy infrastructure. The grantees sue in the federal district court in D.C., which issues a preliminary injunction. D.C. Circuit (over a dissent): Yeah, but the legitimate claims are just "the gov't didn't pay me." That's breach of contract, so get thee to the Court of Federal Claims. (Which is like an eight-minute drive up Pennsylvania Avenue, but, legally, they're worlds apart.)Liars and deltas and rands, oh my! For a federal appeals court, the Second Circuit has a pretty lively tale of financial fraud involving a trader trying to shave 0.6% off the dollar–rand exchange rate to trigger an option worth $20 million. Your editor, who needs to get ready for a moot, doesn't feel like summarizing all six of the trader's claims on appeal. But when the court quotes him early on as telling a subordinate "to start fucking around," reversal seems like a risky bet.In prison-condition news from the Second Circuit, qualified immunity is still hard to overcome. If the prison offers zero penological justification for denying access to a Native American religious service, yeah, maybe that claim can get through. Unclear, though, whether the prisoners cared more about that than the quasi-solitary confinement and the toilets that stop flushing for hours.Elon Musk fired thousands of employees when he took over X (formerly, and forever in our hearts, Twitter). Former employees have claims that (per an arbitration agreement) they try to arbitrate. X disagrees about how much it has to pay toward the arbitration and only ponies up half, so no arbitrator is appointed. District court: That's failure to arbitrate. Second Circuit: Really better for the arbitrator to decide that.In which the Third Circuit holds that Rooker-Feldman applies the same way in bankruptcy courts as in any other federal court, i.e., never.In 2022, Congress enacted a law directing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to negotiate drug prices for certain drugs that lack a generic competitor. Drug companies sue, alleging that the law is an unconstitutional taking of property, compels speech, and imposes unconstitutional conditions on participation. Third Circuit: Companies are free not to participate in Medicare Part D. Dissent: Companies that make that choice face excise taxes of up to 1,900%, which means their freedom not to participate is illusory.New Jersey man—charged as a felon in possession—refuses to enter into stipulation regarding an earlier conviction, despite his lawyer's advice that he do so. So the judge allows the gov't to introduce evidence about that previous conviction to prove elements of the crime. The man is found guilty and appeals, arguing that the district court abused its discretion by allowing in the evidence despite his lawyer's offer to stipulate. Third Circuit: The Sixth Amendment gives you the right to "assistance" of counsel, but if you overrule your counsel, that's on you.In honor of the late Judge Bruce Selya, we share this admiralty decision out of the Fourth Circuit, which taught your summarist a new vocabulary word: Allision, n., a collision between a ship and a stationary object. E.g., "The tugboat owner's invocation of the Exoneration and Limitation of Liability act to limit its liability for the tug's allision with a Maryland bridge was not barred by sovereign immunity."In 2022, Nigerian man is tricked into a terrorist camp, where he serves as a line cook for several months before escaping. He ends up in the U.S. and requests asylum. But must he be deported for having provided "material support" to terrorists? Fourth Circuit: Converting pre-purchased raw ingredients into food isn't really material support. Dissent: "An army marches on its stomach"! Majority: "Our good colleague apparently enjoys bombast for law—wielding rhetorical flourishes about Napoleon's alleged digestive wisdom." (Meanwhile, the gentleman was removed to Nigeria in April 2025; whether Immigration and Customs Enforcement should now facilitate his return is left to the agency's discretion.)Maryland initially makes its new cannabis licenses available only to "social equity applicants." Among various other criteria, a social equity applicant includes companies that are at least 65% owned by folks who went to a Maryland college where at least 40% of students were eligible for Pell Grants. Californian: I went to a California college that fits that description. Maryland: No dice. Fourth Circuit: No Dormant Commerce Clause violation here. That the only qualifying universities are in Maryland does not require Maryland residency."Predatory incursion" may sound like a pulp fiction novel with an odd mix of humans and animals on the cover. In fact, it's been in U.S. law since the Directory governed France. And if it happens the President can swiftly kick "alien enemies" out of the country. But has it or an "invasion" happened? Fifth Circuit: Stop trying to make predatory incursion happen; it's not going to happen. Oldham, J. (dissenting): I'm more a post-Directory kind of judge.Man dining at a Waffle House in Terrytown, La., elides into a verbal altercation with another customer. He then pulls a green pistol from his backpack, making his conversation partner fear for his life. Two weeks later a cop finds out the suspect is at his girlfriend's apartment, where he seems to also be living. Cop obtains a search warrant. In the search they then find a gun, drugs, and ammo. Suppress the evidence? Fifth Circuit: Yes. You had probable cause he did a bad thing at the Waffle House but "probable cause to arrest is not probable cause to search." Warrant was threadbare and exclusionary rule applies. Dissent: C'mon, the guy was living there.Louisiana pretrial detainee with a prosthetic eye tells the jailers about his chronic condition. At first medical staff help him and schedule a follow-up "wound care appointment." But then no one comes to bring him to it. Weeks go by. The detainee complains, but all looks fine after a deputy falsifies a form where it looks like the detainee refused medical treatment. Eventually he files a pro se complaint. District court: This seems fine. Fifth Circuit: Not so fine. Case undismissed.If you thought there was no way the Fifth Circuit was going to find that some provisions in a new Texas voting law violated the Voting Rights Act then you were right (although over a dissent).Illinois prohibits those with concealed-carry licenses from carrying on public transportation. A Second Amendment violation? Seventh Circuit: Nope, there were historical limitations on the right to carry guns in confined, crowded spaces, such as New Mexico's 1852 prohibition on carrying arms at any "Ball or Fandango."Today in implausible exculpatory arguments, Illinois man convicted of being a felon in possession argues—among other things—that he was trying to hide drugs above a ceiling tile in a gas-station bathroom and it is a total coincidence that a gun was also found there. Seventh Circuit: Not buying it. Nor did you have a privacy interest in the unlocked, out-of-order bathroom.Minnesota enacts a law that prohibits employers from taking any adverse employment action against an employee for declining to attend meetings or receive communications from their employer about religious or political matters. Companies that would like to hold meetings with their employees—probably to discuss unionization—sue, alleging the law violates the First Amendment. State AG: I'm not planning to enforce the law at present. Eighth Circuit (over a dissent): Oh, well then case dismissed.A "sideshow" is an informal and usually illegal demonstration of automotive stunts often held at public intersections. Alameda County, Calif., not content with existing law banning the reckless driving, adopts an ordinance prohibiting people from watching sideshows within 200 feet. Reporter who writes about sideshows challenges the law as applied to his reporting. District court: The First Amendment does not apply to his newsgathering and reporting activities. Ninth Circuit: Incorrect. Preliminary injunction granted.Since 2021, more than 600k Venezuelans living in the country have received Temporary Protected Status, allowing them to live and work in the United States for renewable periods of six to 18 months. On Jan. 17, 2025, outgoing DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas extends the TPS designation for 18 months. Seventeen days later, newly confirmed DHS Secretary Kristi Noem vacates the extension. Lawsuits ensue and a district court enjoins the purported vacatur. Ninth Circuit: And correctly so. The law does not permit granted extensions to be revoked.Defendant: My machineguns are protected by the Second Amendment because machineguns are commonly used for self-defense! Tenth Circuit: No, they aren't.Does the Second Amendment permit the gov't to forbid a person under indictment from receiving firearms? Tenth Circuit: Yup! At the Founding, the gov't could throw the indicted person in jail and totally disarm them, which seems, y'know, worse than this. [Editor: D'oh! Thanks to commenter ducksalad for catching a now-fixed flub in this one.]In which the Tenth Circuit reminds us that a plaintiff mounting a pre-enforcement challenge to a statute only needs to establish that he might be prosecuted under the statute, not that he would actually be guilty.In circuit-split news, the Tenth Circuit holds that the federal income tax is not unconstitutional, so there's still no circuit split about that.Come for the Eleventh Circuit's holding that professor/lawyer/gadfly Alan Dershowitz cannot show actual malice by pointing to internal meetings and emails in which CNN employees all seemed to act like they thought their reporting was true. Stay for dueling concurrences about whether the Supreme Court should chuck the actual-malice standard entirely.How many times may a citizen call 911 without being arrested for calling 911 for the purpose of harassment? Your summarist will not venture a guess, but this Eleventh Circuit opinion suggests the number is perhaps less than "a gazillion."And in en banc news, the Fifth Circuit will reconsider its opinion affirming a preliminary injunction against Texas's SB 4, a law criminalizes both reentry into Texas by certain aliens and border crossings at any location other than a federal port of entry. But will the en banc court base its ruling on standing? Sovereign immunity? Federal preemption? Invasion? Only time will tell.For 24 years, Gene and Debbie Weierbach have run an auto repair shop in their garage on a secluded, 16-acre piece of land in North Whitehall, Pa. No neighbor has ever complained, and the home business allows the Weierbachs to look after their adult son, who has severe autism. But when Gene told a bumptious township supervisor that he might be happy if he took his business elsewhere, the supervisor got the township to issue a cease-and-desist order, commanding the Weierbachs to shut down their shop. Now they've joined with IJ to fight back. Read more here!

The post Short Circuit: An Inexhaustive Weekly Compendium of Rulings from the Federal Courts of Appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[John Ross] Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal

[Predatory incursion, financial fraud, and taking your gun to a fandango.]

Please enjoy the latest edition of Short Circuit, a weekly feature written by a bunch of people at the Institute for Justice.

New cert petition! According to the Alaska Supreme Court, it's a-okay to forfeit bush pilot Ken Jouppi's $95,000 airplane over a passenger's six-pack of Budweiser. According to us, that's wrong. And sharpens a division among the state and federal courts. And is a compelling candidate for Supreme Court review. Sit back, relax, and enjoy this breezy read about the most excessively fine clause in the Constitution.

In March 2025, the EPA cancels "Green New Deal" grants for clean-energy infrastructure. The grantees sue in the federal district court in D.C., which issues a preliminary injunction. D.C. Circuit (over a dissent): Yeah, but the legitimate claims are just "the gov't didn't pay me." That's breach of contract, so get thee to the Court of Federal Claims. (Which is like an eight-minute drive up Pennsylvania Avenue, but, legally, they're worlds apart.)Liars and deltas and rands, oh my! For a federal appeals court, the Second Circuit has a pretty lively tale of financial fraud involving a trader trying to shave 0.6% off the dollar–rand exchange rate to trigger an option worth $20 million. Your editor, who needs to get ready for a moot, doesn't feel like summarizing all six of the trader's claims on appeal. But when the court quotes him early on as telling a subordinate "to start fucking around," reversal seems like a risky bet.In prison-condition news from the Second Circuit, qualified immunity is still hard to overcome. If the prison offers zero penological justification for denying access to a Native American religious service, yeah, maybe that claim can get through. Unclear, though, whether the prisoners cared more about that than the quasi-solitary confinement and the toilets that stop flushing for hours.Elon Musk fired thousands of employees when he took over X (formerly, and forever in our hearts, Twitter). Former employees have claims that (per an arbitration agreement) they try to arbitrate. X disagrees about how much it has to pay toward the arbitration and only ponies up half, so no arbitrator is appointed. District court: That's failure to arbitrate. Second Circuit: Really better for the arbitrator to decide that.In which the Third Circuit holds that Rooker-Feldman applies the same way in bankruptcy courts as in any other federal court, i.e., never.In 2022, Congress enacted a law directing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to negotiate drug prices for certain drugs that lack a generic competitor. Drug companies sue, alleging that the law is an unconstitutional taking of property, compels speech, and imposes unconstitutional conditions on participation. Third Circuit: Companies are free not to participate in Medicare Part D. Dissent: Companies that make that choice face excise taxes of up to 1,900%, which means their freedom not to participate is illusory.New Jersey man—charged as a felon in possession—refuses to enter into stipulation regarding an earlier conviction, despite his lawyer's advice that he do so. So the judge allows the gov't to introduce evidence about that previous conviction to prove elements of the crime. The man is found guilty and appeals, arguing that the district court abused its discretion by allowing in the evidence despite his lawyer's offer to stipulate. Third Circuit: The Sixth Amendment gives you the right to "assistance" of counsel, but if you overrule your counsel, that's on you.In honor of the late Judge Bruce Selya, we share this admiralty decision out of the Fourth Circuit, which taught your summarist a new vocabulary word: Allision, n., a collision between a ship and a stationary object. E.g., "The tugboat owner's invocation of the Exoneration and Limitation of Liability act to limit its liability for the tug's allision with a Maryland bridge was not barred by sovereign immunity."In 2022, Nigerian man is tricked into a terrorist camp, where he serves as a line cook for several months before escaping. He ends up in the U.S. and requests asylum. But must he be deported for having provided "material support" to terrorists? Fourth Circuit: Converting pre-purchased raw ingredients into food isn't really material support. Dissent: "An army marches on its stomach"! Majority: "Our good colleague apparently enjoys bombast for law—wielding rhetorical flourishes about Napoleon's alleged digestive wisdom." (Meanwhile, the gentleman was removed to Nigeria in April 2025; whether Immigration and Customs Enforcement should now facilitate his return is left to the agency's discretion.)Maryland initially makes its new cannabis licenses available only to "social equity applicants." Among various other criteria, a social equity applicant includes companies that are at least 65% owned by folks who went to a Maryland college where at least 40% of students were eligible for Pell Grants. Californian: I went to a California college that fits that description. Maryland: No dice. Fourth Circuit: No Dormant Commerce Clause violation here. That the only qualifying universities are in Maryland does not require Maryland residency."Predatory incursion" may sound like a pulp fiction novel with an odd mix of humans and animals on the cover. In fact, it's been in U.S. law since the Directory governed France. And if it happens the President can swiftly kick "alien enemies" out of the country. But has it or an "invasion" happened? Fifth Circuit: Stop trying to make predatory incursion happen; it's not going to happen. Oldham, J. (dissenting): I'm more a post-Directory kind of judge.Man dining at a Waffle House in Terrytown, La., elides into a verbal altercation with another customer. He then pulls a green pistol from his backpack, making his conversation partner fear for his life. Two weeks later a cop finds out the suspect is at his girlfriend's apartment, where he seems to also be living. Cop obtains a search warrant. In the search they then find a gun, drugs, and ammo. Suppress the evidence? Fifth Circuit: Yes. You had probable cause he did a bad thing at the Waffle House but "probable cause to arrest is not probable cause to search." Warrant was threadbare and exclusionary rule applies. Dissent: C'mon, the guy was living there.Louisiana pretrial detainee with a prosthetic eye tells the jailers about his chronic condition. At first medical staff help him and schedule a follow-up "wound care appointment." But then no one comes to bring him to it. Weeks go by. The detainee complains, but all looks fine after a deputy falsifies a form where it looks like the detainee refused medical treatment. Eventually he files a pro se complaint. District court: This seems fine. Fifth Circuit: Not so fine. Case undismissed.If you thought there was no way the Fifth Circuit was going to find that some provisions in a new Texas voting law violated the Voting Rights Act then you were right (although over a dissent).Illinois prohibits those with concealed-carry licenses from carrying on public transportation. A Second Amendment violation? Seventh Circuit: Nope, there were historical limitations on the right to carry guns in confined, crowded spaces, such as New Mexico's 1852 prohibition on carrying arms at any "Ball or Fandango."Today in implausible exculpatory arguments, Illinois man convicted of being a felon in possession argues—among other things—that he was trying to hide drugs above a ceiling tile in a gas-station bathroom and it is a total coincidence that a gun was also found there. Seventh Circuit: Not buying it. Nor did you have a privacy interest in the unlocked, out-of-order bathroom.Minnesota enacts a law that prohibits employers from taking any adverse employment action against an employee for declining to attend meetings or receive communications from their employer about religious or political matters. Companies that would like to hold meetings with their employees—probably to discuss unionization—sue, alleging the law violates the First Amendment. State AG: I'm not planning to enforce the law at present. Eighth Circuit (over a dissent): Oh, well then case dismissed.A "sideshow" is an informal and usually illegal demonstration of automotive stunts often held at public intersections. Alameda County, Calif., not content with existing law banning the reckless driving, adopts an ordinance prohibiting people from watching sideshows within 200 feet. Reporter who writes about sideshows challenges the law as applied to his reporting. District court: The First Amendment does not apply to his newsgathering and reporting activities. Ninth Circuit: Incorrect. Preliminary injunction granted.Since 2021, more than 600k Venezuelans living in the country have received Temporary Protected Status, allowing them to live and work in the United States for renewable periods of six to 18 months. On Jan. 17, 2025, outgoing DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas extends the TPS designation for 18 months. Seventeen days later, newly confirmed DHS Secretary Kristi Noem vacates the extension. Lawsuits ensue and a district court enjoins the purported vacatur. Ninth Circuit: And correctly so. The law does not permit granted extensions to be revoked.Defendant: My machineguns are protected by the Second Amendment because machineguns are commonly used for self-defense! Tenth Circuit: No, they aren't.Does the Second Amendment permit the gov't to forbid a person under indictment from receiving firearms? Tenth Circuit: Nope! At the Founding, the gov't could throw the indicted person in jail and totally disarm them, which seems, y'know, worse than this.In which the Tenth Circuit reminds us that a plaintiff mounting a pre-enforcement challenge to a statute only needs to establish that he might be prosecuted under the statute, not that he would actually be guilty.In circuit-split news, the Tenth Circuit holds that the federal income tax is not unconstitutional, so there's still no circuit split about that.Come for the Eleventh Circuit's holding that professor/lawyer/gadfly Alan Dershowitz cannot show actual malice by pointing to internal meetings and emails in which CNN employees all seemed to act like they thought their reporting was true. Stay for dueling concurrences about whether the Supreme Court should chuck the actual-malice standard entirely.How many times may a citizen call 911 without being arrested for calling 911 for the purpose of harassment? Your summarist will not venture a guess, but this Eleventh Circuit opinion suggests the number is perhaps less than "a gazillion."And in en banc news, the Fifth Circuit will reconsider its opinion affirming a preliminary injunction against Texas's SB 4, a law criminalizes both reentry into Texas by certain aliens and border crossings at any location other than a federal port of entry. But will the en banc court base its ruling on standing? Sovereign immunity? Federal preemption? Invasion? Only time will tell.For 24 years, Gene and Debbie Weierbach have run an auto repair shop in their garage on a secluded, 16-acre piece of land in North Whitehall, Pa. No neighbor has ever complained, and the home business allows the Weierbachs to look after their adult son, who has severe autism. But when Gene told a bumptious township supervisor that he might be happy if he took his business elsewhere, the supervisor got the township to issue a cease-and-desist order, commanding the Weierbachs to shut down their shop. Now they've joined with IJ to fight back. Read more here!

The post Short Circuit: An inexhaustive weekly compendium of rulings from the federal courts of appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Keith E. Whittington] Donald Trump, Constitutionalism, and the Third Face of Power

[How to speak a new constitution into being]

Early in my career, I wrote a paper on "constitutional theory and the faces of power." It borrowed from an older concept in political science to reflect on the less examined ways in which constitutions shape and limit political outcomes and constrain the exercise of power. That particular paper did not exactly light the scholarly world on fire, but it reflected a general theme of my work on constitutions.

Constitutional lawyers in particular tend to focus on the countermajoritarian checks -- the veto points -- built into our constitutional system. That is, after all, where constitutional law lives. But those veto points are what might be characterized as only the "first" and most explicit face of power in a political system. There are more subtle but still extremely important ways in which constitutions limit power, and we are getting a lesson in them now. President Donald Trump's latest social media post about Rosie O'Donnell is just the latest example of how he presses on those most subtle -- and ultimately more important -- constitutional constraints.

As political science was remaking itself into its more modern form in the postwar era, the great Yale democratic theorist Robert Dahl pushed scholars of politics to think more carefully about the concept of power. What was it, and how could one know when it was being exercised? Dahl posited a formulation that "A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do." Dahl leveraged this idea to launch his long-running battle with a "ruling elite model" of American politics. (Dahl himself eventually came around to conceding some points to his antagonists in that debate.) He denounced a so-called "realistic" view of politics that knowingly asserted that an amorphous "'they' run things: the old families, the bankers, the City Hall machine, or the party boss behind the scene."

Dahl thought the theory's primary appeal was that it was "virtually impossible to disprove." Dahl thought a serious social scientist should be examining hypotheses that could be empirically tested, which meant less focus on vibes and what "everyone knows" and more focus on the observable, and in particular on "concrete decisions" in which the powerful turned aside the expressed preferences of the powerless. This led him to ask influential questions like how often does the Supreme Court strike down important laws that actually matter to powerful political actors anyway -- that is, how powerful is the Court and how would we know? Questions that have helped drive some of my own work.

One response to Dahl and his investigations of who actually exercises power in American society was to complicate the problem of how power was exercised. It was suggested that Dahl was focused only on the "first face power," but that there was a second and then a third face of power that pluralists like Dahl ignored. The "second" face of power hinged on the control of the political agenda by the "mobilization of bias" within the political system. Power could be exercised by preventing issues from ever coming up for decision in the first place.

These "non-decisions" might be harder to observe but they mattered to political outcomes and could prevent the powerless from realizing their own preferences. Such agenda control might be exercised by a legislative committee chair or a lobbyist behind closed doors. It might be exercised by how political parties and coalitions were put together. Dahl's contemporary E.E. Schattschneider argued that "some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out." More recent institutionalist scholarship would point out that such non-decisions might be generated by the design of policymaking institutions. The mere existence of a presidential veto keeps some things off the legislative agenda without the president ever having to make the "concrete decision" of exercising the veto power to reject a bill, for example.

Yet another, "third" face of power contends that powerful actors can shape political values, ideologies, and preferences such that the powerless do not even imagine to make demands that challenge the powerful. In its initial formulation, this "radical" view drew from Marxist theories of false consciousness, a kind of argument that had gained purchase with New Left scholars by the 1970s but that would have gained little traction among the behaviorists of the 1950s like the young Robert Dahl. But one need not be a Marxist fixated on class consciousness to appreciate that an important part of politics, in a broad Aristotelian sense, is the socialization of citizens into the values and commitments of the regime. Civic education is in part an effort to "Americanize" each new generation by inculcating them with decidedly and distinctively American values (or it could be used to socialize schoolchildren into rejecting such values).

What does this have to do with constitutions and Rosie O'Donnell? The late-nineteenth-century Harvard law professor James Bradley Thayer pointed out that "under no system can the power of courts save a people from ruin; our chief protection lies elsewhere." James Madison thought it was contributing to this third face of power that the Bill of Rights would do its real work. He hoped that, "political truths declared in that solemn manner acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free Government, and as they become incorporated into the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion." Years later the Pennsylvania Jacksonian jurist John Gibson continued to be skeptical about the value of judicial review in preserving constitutional liberties. He put his hopes elsewhere. A written constitution, he thought, "is of inestimable value . . . in rendering its principles familiar to the mass of the people; for, after all, there is no effectual guard against legislative usurpation but public opinion, the force of which, in this country, is inconceivably great."

The third face of constitutional power works by making some things unspeakable. Serious people do not even talk about violating constitutional conventions and constitutional norms, and they are disciplined when they do. We keep some things off the table by building up a social consensus that those are not things about which we should organize our political debates, contest our political elections, or put up for a vote in Congress. An important set of constitutional constraints have already been slipped when the unspeakable becomes a topic of political debate and now we have to rely on other, more explicit tools to keep those ideas from coming to fruition and made into public policy. Judicial review is the last resort, not the first, for enforcing constitutional limits on power.

Donald Trump has an extraordinary superpower in his willingness and ability to speak the unspeakable. It is a trait shared by radical reformers of all sorts, and even sometimes by political leaders. Strikingly, it is a trait that Trump uses not only in regard to public policy or social mores but also to constitutional verities. A president willing to assert in public ideas that flagrantly violate existing constitutional assumptions may not have the immediate power to act on those ideas. They are, after all, "unconstitutional" and "beyond the scope of his authority." Or perhaps they are just "jokes" or things "many people are saying."

But in throwing such ideas against the wall, he can reshape the political agenda, launch new political and intellectual movements, and make the unimaginable imaginable. He breaks down an important set of constitutional constraints and forces us to rely less on our small-c constitution and more on our big-c written Constitution and its explicit checks and balances and veto points. And yet the efficacy of those "parchment barriers" itself depends on the more foundational constitutional culture. Trump exercises real power by reshaping that constitutional culture.

The post Donald Trump, Constitutionalism, and the Third Face of Power appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Welcome to the "Interim Docket"

[Justice Kavanaugh on what to call the "shadow docket" now that it is no longer in the shadows.]

Speaking to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit's Judicial Conference, Justice Brett Kavanaugh suggests that the "interim docket" is a better label for the Supreme Court's docket of requests for interim orders and emergency relief than the "shadow docket."

From a Bloomberg report:

"I think the term 'interim docket' best captures it," Kavanaugh told attendees at the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit's conference in Memphis on Thursday, after he was asked to "settle" the dispute over what to call the justices' oft-criticized practice of issuing brief orders in pending cases without explanation.

Though the docket has also been called the "emergency docket," for its handling of emergency requests for relief — or the "shadow docket" by critics who see it as opaque —Kavanaugh noted that not all of these requests the justices field are emergencies.

"It's not real catchy, so I'm not sure it'll bloom, but that's the term" Kavanaugh said of his preferred label, which he'd also invoked in July at the Eighth Circuit's conference in Kansas City.

The "shadow docket" label was first suggested by Will Baude because the Court's non-merits orders about pending cases, often in response to petitions for emergency or extraordinary relief, did not receive much attention. Such orders, and their effects, were in the shadows, and Baude thought they needed more attention.

The Supreme Court's handling of requests for interim and other relief no longer occurs within the shadows. To the contrary, such orders receive extensive coverage and commentary. Thus the "shadow docket" is no longer apt, and the "interim docket" (or, perhaps, the "interim orders docket") definitely makes more sense.

The post Welcome to the "Interim Docket" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: September 5, 1922

9/5/1922: Justice George Sutherland takes the oath.

Justice George Sutherland

Justice George SutherlandThe post Today in Supreme Court History: September 5, 1922 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Friday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Friday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

September 4, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Professor Barrett's interview on CBS News

[The American people don't know what a "ConLaw" professor is, don't know what "doctrine" means, and don't realize that ACB changed the "doctrine" in Dobbs.]

CBS News posted a short excerpt of a TV interview with Norah O'Donnell and Justice Barrett. I do not think it went well. Consider this brief snippett:

O'Donnell: You wrote in the book that the Court has held that the rights to marry, engage in sexual intimacy, use birth control, and raise children are fundamental. But the rights to do business, committ suicide, and obtain abortion are not.

Barrett: Right, I'm describing the doctrine. I was a ConLaw professor for many years. Yes, I've described the doctrine in the book. And yes that is the state of the law. . . .

O'Donnell: But you also say in the book that the rights to marry and engage in sexual intimacy and use birth control are fundamental.

Barrett: Yes. And again I'm describing what our doctrine is and that is what we've said.

What are the problems here?

First, regular people do not know what a "ConLaw" professor is. ConLaw, CivPro, CrimPro, FedCourts, and other abbreviations are known to lawyers. But not to non-lawyers. When I say that Justice Barrett is still at her heart a law professor, I mean it. This is a vocation one cannot shake.

Second, regular people do not know what "doctrine" means in this context. Of course, Barrett is trying to explain that her book merely restates what the Court has held, and that she is not articulating her private views on marriage, abortion, and birth control. But people watching this clue will have no idea what "doctrine" is, a word she said three times in the span of about a minute.

Third, Barrett is using the word "fundamental" in the legal sense--a right that triggers strict scrutiny. Roe held that abortion was a fundamental right. Casey held that abortion was not a fundamental right, and abortion laws should be reviewed under the heightened "undue burden" standard. I think this is the test that Professor Barrett would have taught for years. O'Donnell, and most Americans, do not know how Barrett used the word "fundamental." Moreover, I think this explanation is incomplete. Dobbs held that abortion rights receive only deferential rational basis review. Justice Barrett cast the deciding fifth for that opinion. She is not merely describing doctrine. She changed the "doctrine." The right to contract was once deemed fundamental, but the Court changed course? And what would stop the Court from holding that other rights are not fundamental.

Years ago, I wrote that Barrett could benefit from media training. I can see how Barrett went through extensive media training. She kept referring back to the book, and repeating that the Court is trying to see what the American people decided, and stating that the Court should not impose its own values on the American people. These are the talking points. But she got tripped up by a fairly predictable question.

This was Justice Barrett's first TV interview. She cancelled an interview with the New York Times "The Daily" podcast. Her session at Lincoln Center with Bari Weiss does not seem to have been livestreamed. Hopefully future interview go better. Then again, ACB said that her husband and assistant screens the stuff she reads:

"To be in this job, you have to not care," she said, referring to the criticism. "You have to have a thick skin."

She added that she doesn't have social media and that her husband and one of her assistants screen material for her and determine whether to share it with her on a "need-to-know arrangement."

Sounds like an episode of South Park.

The post Professor Barrett's interview on CBS News appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] As The Lower Courts Revolt Against Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Kavanaugh Rises To The Moment

[The revolution started with the Boston TRO Party. Who can end it?]

With each new day, the revolt in the lower courts grows. What started with the Boston TRO Party has now spread across the nation. Now, more than a dozen judges talked to Lawrence Hurley of NBC News. The message is loud and clear. The inferior court judges are frustrated with the cursory orders from the emergency docket. Moreover, they blame Chief Justice Roberts for not standing up for the judiciary--and indeed fault Roberts's own rulings as legitimating Trump's criticisms. Here are the key excerpt from the article:

Federal judges are frustrated with the Supreme Court for increasingly overturning lower court rulings involving the Trump administration with little or no explanation, with some worried the practice is undermining the judiciary at a sensitive time.

Some judges believe the Supreme Court, and in particular Chief Justice John Roberts, could be doing more to defend the integrity of their work as President Donald Trump and his allies harshly criticize those who rule against him and as violent threats against judges are on the rise.…

Ten of the 12 judges who spoke to NBC News said the Supreme Court should better explain those rulings, noting that the terse decisions leave lower court judges with little guidance for how to proceed. But they also have a new and concerning effect, the judges said, validating the Trump administration's criticisms. A short rebuttal from the Supreme Court, they argue, makes it seem like they did shoddy work and are biased against Trump.

"It is inexcusable," a judge said of the Supreme Court justices. "They don't have our backs." ….

With tensions so high, four of the judges said they believe the Supreme Court and specifically Roberts, the head of the judiciary, should do more to defend the courts.

The Supreme Court, a second judge said, is effectively assisting the Trump administration in "undermining the lower courts," leaving district and appeals court judges "thrown under the bus." ….

The Supreme Court, that judge said, is effectively endorsing Miller's claims that the judiciary is trying to subvert the presidency.

"It's almost like the Supreme Court is saying it is a 'judicial coup,'" the judge said.…

"Judges in the trenches need, and deserve, well-reasoned, bright-line guidance," a judge said. "Too often today, sweeping rulings arrive with breathtaking speed but minimal explanation, stripped of the rigor that full briefing and argument provide."

Ten of the judges, both Republican and Democratic appointees, agreed the court's lack of explanation is a problem. Judges must follow Supreme Court precedent, but they can find it difficult to assess what the justices are asking them to do.…

A judge who spoke to NBC News expressed frustration that judges' role in the judicial system is being undermined by the Supreme Court's frequent interventions, before there has been extensive litigation and, potentially, a trial.

"It's very discouraging," the judge said. "We are operating in a bit of a vacuum."….

Roberts, who generally does not seek public attention, has long been known as an institutionalist who looks out for the interests of the Supreme Court, but several judges wondered whether that instinct extends to lower courts.

"He should be doing everything he can internally to insist on ordinary process," the judge who has received threats said in reference to the emergency cases. Roberts' end-of-year report was "not enough," the judge added.

Another judge said: "He hasn't been completely absent, and he's trying to do the best he can. I wish he would be a little bit more assertive and aggressive."

"If the entire foundation falls out from under your house, it does no good to have a really well-insulated attic," the judge said. "It sure would be nice if someone had our backs."

Kudos to Judge Burroughs in Boston for calling out Justice Gorsuch publicly and by name. All of these other judges, who have life tenure, feel the need to hide behind the cloak of anonymity. Same for the judges who anonymously tell the press they will not take senior status, even they were eligible long before Emil Bove.

One more quote stuck out:

A judge appointed by President Barack Obama said that while the Supreme Court could do more to explain itself, some lower court judges had been out of line in blocking Trump policies.

"Certainly, there is a strong sense in the judiciary among the judges ruling on these cases that the court is leaving them out to dry," he said. "They are partially right to feel the way they feel."

But, the judge added, "the whole 'Trump derangement syndrome' is a real issue. As a result, judges are mad at what Trump is doing or the manner he is going about things; they are sometimes forgetting to stay in their lane."

Truth. At an event today at SMU, I joked that the federal judiciary health insurance policy should provide special treatment for TDS. There must be some kind of rehab.

There is much to say here, but let me tie together a few disparate threads. This story is the latest in a series of leaks to the press about Chief Justice Roberts. First, there was the leak from the Judicial Conference. Remember that Chief Justice Roberts did not take seriously Judge Boasberg's concern that President Trump would defy orders. Roberts mused that Trump was nice to him at the State of the Union Address. I suspect Jeb(!) thought that response was tone deaf. Second, there was a leak about how Roberts presided over the Smithsonian Board. (The Times reported that only a three--person executive committee of the Board, not including the Chief, approved a letter that the likely-to-be-fired director sent to President Trump; but who appointed that committee?) Third, there has been a never-ending series of leaks from the Supreme Court, first to Joan Biskupic and more recently to Jodi Kantor. Plus, there were a host of leaks about the lackluster internal investigation performed about the Dobbs leak. Justice Alito publicly spoke out and said he thought he knew who leaked it, but the Court said nothing.

At this point, people do not even remember why I first proposed that Roberts should resign: it was the leaks. In August 2020, I wrote that if Roberts can't stop the leaks from his Court, it would be a reflection of his failed leadership, and he should step down. In hindsight, I was onto something. And now, the leaks are not just coming from the Supreme Court, but from every entity under Roberts's control: the lower courts, the Judicial Conference, and even the Smithsonian Institution.

In any other context, when a leader loses the confidence of every facet of his organization, he steps down or is fired. Of course, Roberts is not going to be removed. But I think after twenty-years, even he should be able to see that his leadership has not been successful. He came to the Court with the agenda of reducing 5-4 decisions and increasing the Court's "legitimacy" as an institution. How has that goal worked out? Now, his subordinates are publicly speaking out against him.

Roberts did not comment to NBC News, but he had an unnamed employee offer a comment:

A federal judiciary employee familiar with Roberts' institutional role said there are various reasons he is restrained from speaking out more. If he did, the employee said, the force of what he said would be diluted through repetition, and, with litigation pending in lower courts, he could face accusations of bias or calls for his recusal when he comments on specific cases.

"The chief justice has spoken out strongly against attacks on judges in various contexts, but he has been appropriately judicious in his statements, focusing on institutional norms and not personalities," the employee said.

"The chief justice can't be the public spokesperson against the administration and still do his job of deciding cases, including matters that involve the administration," the person added.

And wouldn't you know it, Robert Dow the Chief's counselor, made very similar remarks at the Sixth Circuit conference on Wednesday.

Dow pointed to other periods in American history when the judiciary loomed large in political debate and sometimes encountered threats of violence over unpopular rulings. "This isn't the first time that we've had to navigate times similar to the times we're in now. It doesn't make it any less scary for all of us who have to navigate that."

Roberts "is very aware of these threats," Dow said.

But he also suggested the chief justice is wary about being pulled into political struggles where the judiciary is at a significant disadvantage compared to the White House and Congress.

"The problem for our branch is that we have a very tiny megaphone, and if we use our megaphone too often, we risk losing what I would say is the long game, and the long game is to preserve our independence," said Dow, who was appointed to the federal bench by President George W. Bush in 2007.

Sound familiar? I wonder who the "federal judicial employee" was?

The truth is that Roberts never actually faces the press. He releases poorly drafted statements that seldom actually resolve the problem at hand. Instead, he trots out Bob Dow to give statements on--and apparently off--the record that likewise fail to address concerns.

So if Roberts is not speaking up for the Court? Who is? NBC News pointed out the obvious:

So far, the only recent public defense from the court has come from conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who said at a legal conference in Kansas City, Missouri, last month that the court has been "doing more and more process to try to get the right answer" and offers more explanation in such cases than it did in the past. In the birthright citizenship cases, for example, the court heard oral arguments and issued a 26-page opinion explaining the decision.

One reason for keeping emergency decisions short, Kavanaugh said, is that the justices have to make decisions but do not necessarily want to pre-judge how cases will ultimately be decided when they come back to the court via the normal appeals process.

"There can be a risk … of making a snap judgment and putting it in writing," even though it might not reflect the court's ultimate conclusion further down the line, he said.

While the Supreme Court wrestles internally with some of the criticism, lower court judges are increasingly focused on their own safety.

I have celebrated Justice Kavanaugh's recent opinions, which explain why the Court is doing what he is doing. Everyone cheers for Justice Barrett's CASA majority, but the most influential opinion should be Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence. He is giving coherence to the "ineterim" dockets when the Chief wants to pretend that nothing out of the ordinary is happening. And he is speaking publicly to reinforce those messages. Right now, Justice Kavanaugh is the only member of the Court rising to the moment.

Today, Kavanaugh continued the mission at the Sixth Circuit conference:

"It's a difficult job that each of us has," he said, as he opened remarks during a luncheon panel at the annual Sixth Circuit Judicial Conference in Memphis, "particularly the trial judges who operate alone." (In the federal system, district courts are the trial courts.)

He called trial-court judges "the front lines of American justice" and thanked them for helping to "preserve and protect the Constitution and the rule of law of the United States."

Justice Kavanaugh's remarks came at a time of increased strain on the Supreme Court's relationship with district court judges, who have often moved swiftly to block President Trump's policies with sweeping preliminary orders, issued before a case has been heard in full. The Supreme Court in turn in June imposed new limits on the lower courts' power to issue orders that affect the whole country, known as universal injunctions.

The justices have also intervened in more than a dozen individual cases in ways that at least temporarily lift blocks imposed by lower court judges that would have stopped Mr. Trump's policies from being implemented while their legality is litigated.

Kavanaugh offered conciliatory remarks about the Chief:

Kavanaugh also came to the defense of Chief Justice John Roberts, who has pushed back publicly on occasion against Trump's attacks on individual judges while seeking to avoid having the courts dragged into a political mudfight that might only fuel perceptions of a politicized judiciary.

"I think the chief justice … has done a great job about picking his spots appropriately over the last seven years, since I've been there, defending the independence of the judiciary, and I think all of us need to do that together," Kavanaugh said during an exchange with 6th Circuit Judges Joan Larsen and Andre Mathis.

Kavanaugh suggested Roberts was right not to engage every time a politician launches a heated rhetorical attack on a judge.

"The tone matters," Kavanaugh said. "We're modeling behavior for everyone. Again, we all fall short at times, but I think redoubling our efforts on tone, especially when the tone around us is in the public sphere, in the political world, on all sides, is loud, it's probably important."

And while Kavanaugh insisted the collegiality at the court is "very strong," he also suggested Roberts often has to mediate differences among the justices on how the court is run. Kavanaugh compared that to "trying to herd cats."

"Let's just say, it's not easy," Kavanaugh said.

Today I spoke at the SMU FedSoc chapter. My plan was to talk about some recent Supreme Court cases. But I called an audible and instead talked about the lower court revolt. (I decided to do so about 5 minutes before we began.) I said something that I wasn't planning to say, and didn't think I would ever say, but now feel might be right.

Chief Justice Roberts should step down and President Trump should elevate Justice Kavanaugh to the Chief Justice position. Being Chief Justice is not a permanent sinecure. Judges have life tenure, not a life sentence. Justice Kavanaugh might be the only person who can steer the Court through this current moment. Roberts cannot.

I think Kavanaugh can push the Court to grant cert before judgment more often, hold oral argument, and issue reasoned emergency docket opinions. No more one-paragraph John Roberts blue plate specials. Roberts is so concerned about saying too much, that he invariably says too little. And Justice Kavanaugh has the media savvy to speak intelligently to the American public, and not hide behind pretentious press releases and cryptic comments at conferences.

Chief Justice Roberts would no doubt worry who President Trump might replace him with. But I like to think that Roberts would be assured if Kavanaugh picked up the mantle. Again, I have been a vigorous Kavanaugh critic over the years. I had, have, and will have my differences with him. But there are much bigger issues at play.

The post As The Lower Courts Revolt Against Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Kavanaugh Rises To The Moment appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers