Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 45

September 2, 2025

[Jonathan H. Adler] Why the Supreme Court Might Uphold Trump's Tariffs

[The Administration's arguments have more doctrinal support than some might think]

Last week, in V.O.S. Selections v. Trump, the en banc U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held, 7-4, that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) did not authorize the Trump Administration to impose broad reciprocal and other tariffs. Next stop: One First Street.

Some seem to think it is virtually certain that the Supreme Court will invalidate some, if not all, of the Trump tariffs. Here at the VC, my co-blogger Ilya Somin has done yeoman's work unpacking the various arguments against the tariffs and responding to counter-arguments.

While I hope these arguments are successful, I believe V.O.S. Selections presents a close question under current law. I explain why in today's WSJ. Here's a taste:

This is the third court ruling against the Trump tariffs, and it's tempting to assume the Supreme Court will make it four. Don't count on it. At first glance, it's hard to conceive how the Constitution could allow the rewriting of tariff schedules on mere presidential say-so. That President Trump's tariffs are bad policy is icing on the cake. Yet under current doctrine V.O.S. Selections v. Trump presents a close case that is likely to divide the justices and could go either way. . . .

Since the Constitution was adopted, Congress has enacted laws delegating responsibility for executing these powers to the executive branch. Supreme Court precedent requires that in granting such authority, Congress must articulate an "intelligible principle" to its exercise. But the justices have never interpreted that as much of a limitation—broad statements of purpose will do. Thus while V.O.S. Selections is an immensely important separation-of-powers case, it is unlikely to be resolved on constitutional grounds. Instead, the case will turn—as it did in the lower courts—on whether Congress granted the president the power Mr. Trump claims. . . .

The whole point of enacting statutes like IEEPA is to give the president broad authority to address emergencies when they arise. While IEEPA provides that such actions may "only be exercised" to address such declared emergencies "and may not be exercised for any other purpose," courts have rarely felt competent to second-guess the executive branch's national-security determinations.

Presidential power is at its zenith in matters of national security and foreign affairs, so it is understandable why Congress may delegate broader authority in such contexts than in domestic affairs. Setting tariffs on goods from other nations implicates different concerns from domestic environmental regulation or the payback of student loans. . . .

You may read the whole thing here.

The post Why the Supreme Court Might Uphold Trump's Tariffs appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] New in Civitas Outlook: "The Failed Lower Court Revolt"

Civitas Outlook has published my new essay, titled The Failed Lower Court Revolt. Here is the introduction:

Shortly before President Trump began his second term, Chief Justice John Roberts issued a not-too-subtle warning: the incoming administration might ignore Supreme Court rulings. Roberts was right that the high court's ruling would be discarded, but Trump is not to blame. Indeed, the Trump Administration stated in absolute terms that it would follow every facet of Supreme Court decisions. For better or worse, Trump has tied his fate to the Nine.

Rather, we are witnessing a remarkable shift in the lower courts. Federal judges on the East and West Coasts–not in flyover country–are blocking nearly every action taken by the Trump Administration. In some cases, judges are issuing emergency orders within hours, without even reading all the briefs. And through procedural rules, they can insulate their rulings from any appeal for up to a month. Due to forum shopping, federal courts of appeals within driving distance of an ocean invariably affirm these orders.

The Trump Administration has only one possible recourse: the United States Supreme Court. Much has been written about the so-called "shadow" or emergency docket. But the simple truth is that unless the Supreme Court intervenes at an early point–what Justice Brett Kavanaugh calls the "interim before the interim"–inferior court judges will basically have the final say over executive power. And to be clear, it is the Constitution that calls them "inferior" judges. Inferior courts sit below the United States Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has declared that "[U]nless we wish anarchy to prevail within the federal judicial system, a precedent of this Court must be followed by the lower federal courts no matter how misguided the judges of those courts may think it to be." Yet, in the view of a majority of the Supreme Court, anarchy by the inferior courts is reigning supreme.

I talk about three lines of cases where the Supreme Court was forced to promptly, and sharply, rebuke lower courts that were out of line. I conclude:

Perhaps we can make an addendum to this concept of the presumption of regularity. No President can actually lose this presumption. This deference is afforded to the President by virtue of his victory in the election; nothing his administration says or does can affect that presumption. But federal judges lack any such accountability. I think the Supreme Court is telling lower federal judges–especially in Boston–that they have lost the presumption of judicial regularity. And so long as they issue rulings that do not faithfully follow precedent, the Supreme Court will feel compelled to intervene on the emergency docket. As Justice Gorsuch explained, "Lower court judges may sometimes disagree with this Court's decisions, but they are never free to defy them."

We should be grateful that the Supreme Court stopped this failed lower court revolt. Chief Justice Roberts seems partially committed to this cause. He joined the majority in D.V.D. and Boyle, but not in NIH. I think the Chief Justice should worry far more about a revolt from the lower courts than resistance from Trump.

The post New in Civitas Outlook: "The Failed Lower Court Revolt" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Judge Barbara Lagoa (11th Cir.) Criticizes New York Times v. Sullivan

From Judge Lagoa's concurrence in Friday's Dershowitz v. CNN, Inc. (and see also Judge Charles Wilson's concurrence taking the opposite view):

In New York Times, Inc. v. Sullivan, the Court usurped control over [the] field of speech-related torts and invented "a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with 'actual malice'—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not." Three years later, this same rule was extended to "public figures" in addition to public officials…. [In 1974,] the Court held for the first time that falsity and harm were not enough, and even private plaintiffs must show some sort of "fault," negligence at the least, to recover for defamation. And, even with that proof of culpable fault, damages were not presumed but had to be proven … [and] no plaintiff could recover punitive damages for defamation without showing Sullivan-style malice. With this series of cases … one generation of the Supreme Court succeeded in imposing federal constitutional limitations (seemingly untethered to the Constitution's original meaning) on all defamation claims brought by all manner of plaintiffs.

Justice White recognized the ill-fated trajectory of this line of cases after originally joining the majority in Sullivan…. Justice White elaborated on the central problem in Sullivan: A people who govern themselves, as the Founders intended us to do, are entitled to adequate information about their government and their representatives, and that essential flow of information warrants First Amendment protection; but protecting lies—by insulating those who spread them behind an iron barrier, to be breached only by a showing of actual malice—does nothing to support an informed populus and, instead, has the contrary effect of leaving lies uncorrected. … "Also, by leaving the lie uncorrected, the New York Times rule plainly leaves the public official without a remedy for the damage to his reputation. Yet the Court has observed that the individual's right to the protection of his own good name is a basic consideration of our constitutional system, reflecting our basic concept of the essential dignity and worth of every human being—a concept at the root of any decent system of ordered liberty."

As the Court concluded in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., "there is no constitutional value in false statements of fact. Neither the intentional lie nor the careless error materially advances society's interest in 'uninhibited, robust, and wide-open' debate on public issues." But that is precisely Sullivan's effect. Under the actual-malice standard, the public's "only chance of being accurately informed is measured by the public [figure's] ability himself to counter the lie, unaided by the courts. That is a decidedly weak reed to depend on for the vindication of First Amendment interests." … "While the argument that public figures need less protection because they can command media attention to counter criticism may be true for some very prominent people, even then it is the rare case where the denial overtakes the original charge. Denials, retractions, and corrections are not 'hot' news, and rarely receive the prominence of the original story."

Quite the journey we have taken from Sullivan's attempt to protect the public's interest in being fully informed on matters of public import. But that, in fact, precisely identifies the error at the heart of Sullivan: In "federaliz[ing] major aspects of libel law by declaring unconstitutional in important respects the prevailing defamation law in all or most of the 50 States," the Court "made little effort to ground [its] holdings in the original meaning of the Constitution." …

What, then, does the original meaning of the First Amendment tell us about the propriety of an actual-malice standard? To understand the original meaning of the First Amendment is to understand law as those who ratified it did. Our starting place is, therefore, the natural law and our accompanying natural rights as they were understood pre-ratification. Natural rights are those that we possess innately as human beings; their existence does not depend on government endowment. See generally Jud Campbell, Natural Rights and the First Amendment, 127 Yale L.J. 246, 268–80 (2017). As to expression, our Founders recognized a variety of natural rights, including (as relevant here) speaking, writing, and publishing. [Historical evidence omitted. -EV] The "liberty of the press," meaning the freedom to print information, fell within the scope of natural rights that pre-existed our Bill of Rights. Closely related to freedom of the press—distinct, according to some; overlapping according to others—was the freedom to publish, most closely encapsulating that which we now think of as "journalism." There is little doubt, then, that our Founding generation recognized the freedoms to think, speak, write, print, and share ideas as natural rights endowed in the people by their Creator, not their government.

With the natural right established, we turn to the limits the government was authorized to impose on speech. Those limits turn on two central inquiries: the scope of the natural right and the extent to which we, as a people, agreed to some restraint of the natural right in exchange for the benefits that nationhood offered. Enter here the concept of natural law, which, at the least, provides the understanding that, regardless of any government structure, one individual may not interfere with another's natural rights. See Campbell at 271; Philip A. Hamburger, Natural Rights, Natural Law, and American Constitutions, 102 Yale L.J. 907, 922–30 (1993) ("[B]eing equally free, individuals did not have a right to infringe the equal rights of others, and, correctly understood, even self-preservation typically required individuals to cooperate—to avoid doing unto others what they would not have others do unto them." (citing John Locke, Two Treatises of Government). As James Wilson explained it in his 1790 Lectures on Law, as to avoiding injury and injustice under the natural law, each person may act "for the accomplishment of those purposes, in such a manner, and upon such objects, as his inclination and judgment shall direct; provided he does no injury to others; and provided some publick interests do not demand his labours. This right is natural liberty." …

Jud Campbell has … explain[ed] that "whether inherently limited by natural law or qualified by an imagined social contract, retained natural rights were circumscribed by political authority to pursue the general welfare. Decisions about the public good, however, were left to the people and their representatives—not to judges—thus making natural rights more of a constitutional lodestar than a source of judicially enforceable law." Thus, the Founders simultaneously understood that freedom of speech was both a natural right not dependent on government creation, and also subject to certain limitations for the public good—so long as those limitations did not abridge the natural right as it existed in a system of natural law. And while the freedoms of speech and of the press were both viewed as natural rights, they were viewed as properly subject to different regulation, with recognition that written statements were "more extended" and "more strongly fixed," thus "posing a greater threat to public order."

We turn next to the contours of the natural right and the natural law, and the types of restriction that were viewed as consistent with those boundaries. The Founders widely believed that "opinions," as James Madison observed to his colleagues, "are not the objects of legislation." In other words, opinion, understood as non-volitional thought, was not subject to government regulation at the time of the Founding.

But the freedom of opinion raises another question: What forms an opinion? History confirms that the freedom to express opinions was, indeed, limited to honest statements and did not encompass dishonesty or deceit. For instance, even in the debates over the Sedition Act, a persistent and widespread consensus emerged that "well-intentioned statements of opinion, including criticisms of government, were constitutionally shielded."

Consistent with the notion that the natural right to free speech coexisted with a limitation forbidding injurious lies, "10 of the 14 States that had ratified the Constitution by 1792 had themselves provided constitutional guarantees for free expression, and 13 of the 14 nevertheless provided for the prosecution of libels." …

What do we take away from the original sources? As the Supreme Court observed in Roth, "[t]he protection given speech and press was fashioned to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people," but such assurance focused on the exchange of ideas in service of advancing truth and imposed no additional burdens to recovery based on the harmed party's station in society. In a 1774 letter to the inhabitants of Quebec, the Continental Congress expressed the following objective:

The last right we shall mention, regards the freedom of the press. The importance of this consists, besides the advancement of truth, science, morality, and arts in general, in its diffusion of liberal sentiments on the administration of Government, its ready communication of thoughts between subjects, and its consequential promotion of union among them, whereby oppressive officers are shamed or intimidated, into more honourable and just modes of conducting affairs.

This statement from the Continental Congress … supports a conclusion that "[a]ll ideas having even the slightest redeeming social importance—unorthodox ideas, controversial ideas, even ideas hateful to the prevailing climate of opinion—have the full protection of the guaranties, unless excludable because they encroach upon the limited area of more important interests." Among those "excludable" expressions, we can only conclude, are those that patently do not serve "the advancement of truth."

Notably absent from the historical discussion is anything resembling a heightened requirement making it more difficult to prosecute libel or slander directed at an official (much less a "public figure") rather than a private citizen. On the contrary, the accepted consensus was that public officials could sue for libel "upon the same footing with a private individual" because "[t]he character of every man should be deemed equally sacred, and of consequence entitled to equal remedy." Tunis Wortman, A Treatise, Concerning Political Enquiry, and the Liberty of the Press (1800); accord St. George Tucker, View of the Constitution of the United States with Selected Writings (1803) ("[T]he judicial courts of the respective states are open to all persons alike, for the redress of injuries of this nature; there, no distinction is made between one individual and another; the farmer, and the man in authority, stand upon the same ground: both are equally entitled to redress for any false aspersion on their respective characters, nor is there any thing in our laws or constitution which abridges this right.").

From all this, I conclude, as Justice White did in Gertz, that "[s]cant, if any, evidence exists that the First Amendment was intended to abolish the common law of libel, at least to the extent of depriving ordinary citizens of meaningful redress against their defamers." What the historical documents suggest is that, in its original context, the First Amendment was intended to protect free dissemination of ideas—all manner of ideas, particularly those out of fashion or disfavored—but not the dissemination of lies. See, e.g., 10 Benjamin Franklin Writings 38 (1907) ("If by the Liberty of the Press were understood merely the Liberty of discussing the Propriety of Public Measures and political opinions, let us have as much of it as you please: But if it means the Liberty of affronting, calumniating, and defaming one another, I, for my part, own myself willing to part with my Share of it when our Legislators shall please so to alter the Law, and shall cheerfully consent to exchange my Liberty of Abusing others for the Privilege of not being abus'd myself."); Frank Luther Mott, Jefferson and the Press 14 (1943) (explaining that Thomas Jefferson endorsed the language of the First Amendment as ratified only after suggesting that "[t]he people shall not be deprived of their right to speak, to write, or otherwise to publish anything but false facts affecting injuriously the life, liberty or reputation of others").

And we held onto that principle for the first two centuries of our national existence. Just a decade before Sullivan, the Supreme Court reiterated as much, explaining that "[l]ibelous utterances not being within the area of constitutionally protected speech, it is unnecessary, either for us or for the State courts, to consider the issues behind the phrase 'clear and present danger.'" But, as we know, this interpretation of the First Amendment, true to its original meaning, fell apart shortly thereafter….

As expressed by Justice White, Sullivan and its progeny represent "an ill-considered exercise of the power entrusted to [the] Court." The lasting effect of Sullivan, as anyone who ever turns on the news or opens a social media app knows well, is that media organizations can "cast false aspersions on public figures with near impunity," causing untold harm to public figures and the general public alike. Jettisoning the original meaning of the First Amendment—and centuries of common law faithful to that meaning—has left us in an untenable place, where by virtue of having achieved some bit of notoriety in the public sphere, defamation victims are left with scant chance at recourse for clear harms.

But until the Supreme Court reconsiders Sullivan, we are bound by it, and I therefore must concur.

The post Judge Barbara Lagoa (11th Cir.) Criticizes New York Times v. Sullivan appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Judge Charles Wilson (11th Cir.) Defends New York Times v. Sullivan

From Judge Wilson's concurrence in Friday's Dershowitz v. CNN, Inc. (and see also Judge Barbara Lagoa's concurrence taking the opposite view):

"Fidelity to precedent—the policy of stare decisis—is vital to the proper exercise of the judicial function." I believe that Sullivan reflects "the accumulated wisdom of judges who have previously tried to solve the same problem."

To be sure, our understanding of the First Amendment should be guided by its original meaning and heed common law traditions. But "ambiguous historical evidence" does not justify casting aside a unanimous Supreme Court decision and nearly sixty years of settled precedent. The "real-world consequences" and reliance interests at stake counsel us to pump the brakes before calling to overrule Sullivan….

Adherence to precedent is "a foundation stone of the rule of law." Stare decisis is the "means by which we ensure that the law will not merely change erratically, but will develop in a principled and intelligible fashion," and "permits society to presume that bedrock principles are founded in the law rather than in the proclivities of individuals." …

"The Framers of our Constitution understood that the doctrine of stare decisis is part of the 'judicial Power' and rooted in Article III of the Constitution." Alexander Hamilton wrote that to "avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts, it is indispensable" that federal judges "should be bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them." Blackstone wrote that "it is an established rule to abide by former precedents," to "keep the scale of justice even and steady, and not liable to waver with every new judge's opinion."

Of course, Judges and even Justices, are fallible. And it is especially important for the Court to correct errors in constitutional rulings, which "Congress cannot override … by ordinary legislation." But even in constitutional cases, the Supreme Court "has always held that 'any departure'" from precedent "demands special justification." This is especially true when the constitutional protections recognized by the precedent have "become part of our national culture." …

In his concurring opinion in Ramos v. Louisiana, Justice Kavanaugh synthesized the Supreme Court's "varied and somewhat elastic stare decisis factors" into "three broad considerations" to determine what qualifies as a "special justification" or "strong grounds" to overrule a prior constitutional decision

First, the precedent must be "egregiously wrong as a matter of law." "A garden-variety error or disagreement does not suffice to overrule." The Court examines factors such as "the quality of the precedent's reasoning, consistency and coherence with other decisions, changed law, changed facts, and workability." Second, the Court considers whether "the prior decision caused significant negative jurisprudential or real-world consequences." This includes both "jurisprudential consequences," such as "workability, … consistency and coherence with other decisions," and "the precedent's real-world effects on the citizenry." Finally, the Court examines whether "overruling the prior decision unduly upset reliance interests." "This consideration focuses on the legitimate expectations of those who have reasonably relied on the precedent. In conducting that inquiry, the Court may examine a variety of reliance interests and the age of the precedent, among other factors." …

Judge Wilson concluded that Sullivan wasn't egregiously wrong:

Sullivan's "actual malice" requirement "has its counterpart in rules previously adopted by a number of state courts and extensively reviewed by scholars for generations." The rule is premised both on "common-law tradition" and "the unique character of the interest" it protects.

Sullivan was "widely perceived as essentially protective of press freedoms," and "has been repeatedly affirmed as the appropriate First Amendment standard applicable in libel actions brought by public officials and public figures." It "honored both the Court's previous recognition that 'libel' is not protected by the First Amendment and its concomitant obligation to determine the definitional contours of that category of unprotected speech." Lee Levine & Stephen Wermiel, What Would Justice Brennan Say to Justice Thomas?, 34 Commn's Law. 1, 2 (2019).

For decades after Sullivan, even as defamation plaintiffs petitioned the Court to limit or overrule the case, the Court refused. Matthew L. Schafer, In Defense: New York Times v. Sullivan, 82 La. L. Rev. 81, 84 & n.18 (2021). Although it faced some academic skepticism since the 1980s {e.g., Richard A. Epstein, Was New York Times v. Sullivan Wrong?, 53 U. Chi. L. Rev. 782 (1986)}, a "growing movement to engineer the overruling of Sullivan" has emerged in recent years, fueled by the idea that it represents an exercise of "judicial policymaking." See Samantha Barbas, New York Times v. Sullivan: Perspectives from History, 30 Geo Mason L. Rev. F. 1, 2 (2023)….

And experience tells us that "disputed history provides treacherous ground on which to build decisions written by judges who are not expert at history." See also, e.g., Schafer ("The freedom of the press that Thomas and Gorsuch espouse [in recent opinions criticizing Sullivan] is not an originalist one; it is a monarchist's one, predating the Founding and purporting to import into the First Amendment today common law rules long ago rejected by the Founders and early courts. This approach, however, violates Thomas's own instruction that what matters for the purposes of an originalist inquiry is the 'founding era understanding.' Indeed, Thomas's view ignores that there was a Revolution, and that no small complaint of that Revolution was England's abuses of prosecutions of early American printers. It also ignores everything that happened between 1789 and 1868 when the Fourteenth Amendment made the First Amendment applicable as against the States. Thomas's failure to deal with this history draws into question his supposed commitment to it."); Josh Blackman, Originalism and Stare Decisis in the Lower Courts, 13 N.Y.U. J.L. & Liberty 44, 54–55 (2019) (recognizing the Seditious Conspiracy Act provides "some originalist basis to impose a higher bar for libel suits filed by government officials").

History's flaws are especially apparent when confronting the law of libel in the United States, which "is not now, nor ever was, tidy." Schafer. "The founding generation and the Congresses of the Reconstruction were not of one mind when it came to the common law of libel or the effect, if any, the First and Fourteenth Amendments had on it." "We know very little of the precise intentions of the framers and ratifiers of the speech and press clauses of the first amendment" when it comes to defamation actions. Ollman v. Evans (D.C. Cir. 1984) (Bork, J., concurring). "But we do know that they gave into our keeping the value of preserving free expression and, in particular, the preservation of political expression, which is commonly conceded to be the value at the core of those clauses."

The Founders rejected early attempts to "transplant the English rule of libels on government to American soil." And "the restricted rules of the English law in respect of the freedom of the press in force when the Constitution was adopted were never accepted by the American colonists." Rather, "[o]ne of the objects of the Revolution was to get rid of the English common law on liberty of speech and of the press." Henry Schofield, Freedom of the Press in the United States, 9 Proc. Am. Soc. Soc'y 67, 76 (1914).

Conflicting history aside, "[i]t is ironic that an approach so utterly dependent on tradition is so indifferent to our precedents." The Supreme Court's First Amendment jurisprudence "is one of continual development, as the Constitution's general command that 'Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press,' has been applied to new circumstances requiring different adaptations of prior principles and precedents." Sullivan is part of a "judicial tradition of a continuing evolution of doctrine to serve the central purpose of the first amendment."

The consistent, guiding principle since the Founding and throughout our country's history is that the First Amendment "rests on the assumption that the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources is essential to the welfare of the public, that a free press is a condition of a free society." … Playing a key role in the marketplace, the "press serves and was designed to serve as a powerful antidote to any abuses of power by governmental officials and as a constitutionally chosen means for keeping officials elected by the people responsible to all the people whom they were selected to serve." "Suppression of the right of the press to praise or criticize governmental agents … muzzles one of the very agencies the Framers of our Constitution thoughtfully and deliberately selected to improve our society and keep it free."

What was true in 1791, 1868, and 1964 remains true today: a libel law regime that allows public figures and officials to silence "speech that matters," absent complete accuracy, "dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate" and is "inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments."

Judge Wilson went on to argue that Sullivan has not "caused significant negative jurisprudential or real-world consequences":

Looking first to jurisprudential consequences, such as consistency and workability, Sullivan's actual-malice rule allows courts to "expeditiously weed out unmeritorious defamation suits" while "preserv[ing] First Amendment freedoms and giv[ing] reporters, commentators, bloggers, and tweeters (among others) the breathing room they need to pursue the truth."

A return to the common-law defense that "the alleged libel was true in all its factual particulars," rather than malice, would be nearly unworkable. The "difficulties of separating fact from fiction convinced the Court in New York Times, Butts, Gertz, and similar cases to limit liability to instances where some degree of culpability is present in order to eliminate the risk of undue self-censorship and the suppression of truthful material." And hinging liability for public criticism on a judge or jury's determination of what is true deviates from the "marketplace of ideas" the First Amendment protects—where truth depends on an idea's competition with other ideas, not a government censor. Jane E. Kirtley, Uncommon Law: The Past, Present and Future of Libel Law in a Time of "Fake News" and "Enemies of the American People", 2020 U. Chi. L.F. 117, 123 (2020).

As far as "real-world effects on the citizenry," Sullivan allowed the public and the press to criticize public officials and public figures, and contribute to vital national dialogue without fear of unwarranted retaliation. Over the last sixty years, Sullivan's "actual malice" requirement has consistently "ensure[d] that debate on public issues remains uninhibited, robust, and wide-open," while balancing the individual's interest in his reputation….

[As to] the concern about injuries to an individual's reputation …[,] "The sort of robust political debate encouraged by the First Amendment is bound to produce speech that is critical" of public officials or public figures. And plaintiffs who cannot show "actual malice" may suffer some unwarranted reputational harm which cannot "easily be repaired by counterspeech." … [P]ublic figures "have a more realistic opportunity to counteract false statements than private individuals normally enjoy," and perhaps even more so with new technology creating new "channels of effective communication."

The "real world" consequences of stripping away Sullivan's protections in our current media climate would do the opposite of "preserve an uninhibited marketplace of ideas," and "muzzle[ ] one of the very agencies the Framers of our Constitution thoughtfully and deliberately selected to improve our society and keep it free."

And Judge Wilson also concluded that Sullivan has produced important "reliance interests":

Sullivan has "become part of the fabric of American law" and been "woven into a long line of federal and state cases." Roy S. Gutterman, Actually … A Renewed Stand for The First Amendment Actual Malice Defense, 68 Syracuse L. Rev. 579, 580, 602 (2018). Its "recognition that libel law could violate the First Amendment was the critical step that made possible all the Court's subsequent defamation decisions and the many restrictions later imposed on libel law by state judges and legislatures." David A. Anderson, The Promises of New York Times v. Sullivan, 20 Roger Williams U. L. Rev. 1, 23 (2015).

The "evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles" and "reliance on judicial decisions" is "particularly important in the area of free speech for precisely the same reason that the actual malice standard is itself necessary." First Amendment freedoms "are delicate and vulnerable, as well as supremely precious in our society. The threat of sanctions may deter their exercise almost as potently as the actual application of sanctions." "Uncertainty as to the scope of the constitutional protection can only dissuade protected speech—the more elusive the standard, the less protection it affords."

Overruling Sullivan would be especially disruptive because the case defines "the central meaning of the First Amendment" and influenced "virtually all of the Supreme Court's subsequent First Amendment jurisprudence." Wermiel. Casting the decision aside in favor of varied, plaintiff-friendly state libel laws would "create an inevitable, pervasive, and serious risk of chilling protected speech pending the drawing of fine distinctions that, in the end, would themselves be questionable." …

Out of respect for unanimous Supreme Court precedent, and the press freedoms that played a critical role in securing the civil rights many in this country hold dear, judges should reconsider their calls for the Supreme Court to overrule Sullivan. "For it is hard to overstate the value, in a country like ours, of stability in the law."

The post Judge Charles Wilson (11th Cir.) Defends New York Times v. Sullivan appeared first on Reason.com.

September 1, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Help Workers by Breaking Down Barriers to Labor Mobility

[Labor Day is a great time to remember that we can make workers vastly better off by empowering more of them to vote with their feet, both within countries and through international migration.]

Each Labor Day since 2021, I have written posts explaining how breaking down barriers to labor mobility can help many millions of workers around the world. The main points everything last year's post are just as relevant today. So I am reprinting it with some updates and modifications, many of them related to the awful deterioration in immigration policy over the last year:

Today is Labor Day. As usual, there is much discussion of what can be done to help workers. But few focus on the one type of reform that is likely to help more poor and disadvantaged workers than virtually anything else: increasing labor mobility. In the United States and around the world, far too many workers are trapped in places where it is difficult or impossible for them to ever escape poverty. They could vastly improve their lot if allowed to "vote with their feet" by moving to locations where there are better job opportunities. That would also be an enormous boon to the rest of society.

Internationally, the biggest barriers condemning millions to lives of poverty and oppression are immigration restrictions. Economists estimate that eliminating legal barriers to migration throughout the world would roughly double world GDP - in other words, making the world twice as productive as it is now. A person who has the misfortune of being born in Cuba or Venezuela, Zimbabwe or Afghanistan, is likely condemned to lifelong poverty, no matter how talented or hardworking he or she may be. If they are allowed to move to a freer society with better economic institutions, they can almost immediately double or triple their income and productivity. And that doesn't consider the possibility of improving job skills, which is also likely to be more feasible in their new home than in their country of origin.

The vast new wealth created by breaking down migration barriers would obviously benefit migrants themselves. But it also creates enormous advantages for receiving-country natives, as well. They benefit from cheaper and better products, increased innovation, and the establishment of new businesses (which immigrants create at higher rates than natives). Immigrants also contribute disproportionately to scientific and medical innovation, including vaccines and other medical treatments that have already saved millions of lives around the world.

The Trump Administration's massive assault on immigration of virtually every kind will predictably harm both migrants and native-born Americans, condemning hundreds of thousands of the former to a lifetime of poverty and oppression, and denying the latter the growth and innovation immigration facilitates.

Similar, though somewhat less extreme, barriers to labor mobility also harm workers within the United States. Exclusionary zoning prevents many millions of Americans - particularly the poor and working class - from moving to areas where they could find better job opportunities and thereby increase their wages and standard of living. Occupational licensing further exacerbates the problem, by making it difficult for workers in many industries to move from one state to another.

Breaking down barriers to labor mobility is an oft-ignored common interest of poor minorities (most of whom are Democrats), and the increasingly Republican white working class. Both groups could benefit from increased opportunity to move to places where there are more and better jobs and educational opportunities available.

As with lowering immigration restrictions, breaking down domestic barriers to labor mobility would create enormous benefits for society as a whole, as well as the migrants themselves. Economists estimate that cutting back on exclusionary zoning would greatly increase economic growth. Like international migrants, domestic ones can be more productive and innovative if given the opportunity to move to places where they can make better use of their talents.

Many proposals to help workers have a zero-sum quality. They involve attempts to forcibly redistribute wealth from employers, investors, consumers, or some combination of all three. Given that virtually all workers are also consumers, and many also have investments (e.g. - through their retirement accounts), zero-sum policies that help them in one capacity often harm them in another. Breaking down barriers to labor mobility, by contrast, is a positive-sum game that creates massive benefits for both workers and society as a whole; it similarly benefits both migrants and natives.

The same is true of breaking down barriers to the mobility of goods. Tariffs and other trade restrictions harm many more workers than they benefit, by increasing prices (which disproportionately hurt lower-income workers), and increasing the cost of inputs used by domestic industries (leading to lower employment levels and wages). The Tax Foundation estimates that, if they remain in place, the Trump's unconstitutional new IEEPA tariffs will impose $1.8 trillion in new taxes on Americans over the next decade, reduce GDP growth by 0.7% per year, and reduce income by 1.1% in 2026 alone. The actual effects may be even larger, as these estimates do not fully consider the effects of retaliation by trading partners and reduction in consumer choice.

Some on the left point out that, if investors are allowed to move capital freely, workers should be equally free to move, as well. It is indeed true that, thanks to government policies restricting labor mobility, investment capital is generally more mobile than labor. It is also true that the restrictions on labor mobility are deeply unjust. In many cases, they trap people in poverty simply because of arbitrary circumstances of birth, much as racial segregation and feudalism once did. The inequality between labor and capital, and the parallels with segregation and feudalism should lead progressives to put a higher priority on increasing labor mobility.

At the same time, it is worth recognizing that investors and employers, as a class, are likely to benefit from increased labor mobility, too. Increased productivity and innovation create new investment opportunities. The biggest enemies of both workers and capitalists are not each other, but the combination of nativists and NIMBYs who erect barriers to freedom of movement, thereby needlessly impoverishing labor and capital alike. Despite conventional wisdom to the contrary, even current homeowners often have much to gain from curbing exclusionary zoning policies that block the construction of housing needed by workers seeking to move to the region.

On the right, conservatives who value meritocracy and reject racial and ethnic preferences, would do well to recognize that few policies are so anti-meritocratic as barriers to mobility. The case for ending them also has much in common with the case for color-blind government policies, more generally. A number of other conservative values also reinforce the case for curbing both domestic NIMBYism and immigration restrictions. Right-wingers would also do well to recognize that most workers benefit from free trade, and are harmed by protectionism.

There are those who argue against increasing labor mobility, either on the grounds that existing communities have an inherent right to exclude newcomers, or because allowing them to come would have various negative side-effects. I address these types of arguments here, and in much greater detail in Chapters 5 and 6 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom. As I explain in those earlier publications, nearly all such objections are wrong, overblown, or can be ameliorated by "keyhole solutions" that are less draconian than exclusion. In addition, the vast new wealth created by breaking down barriers to mobility can itself be used to help address any potential negative effects. In the book, I also push back against claims that mobility should be restricted for the benefit of those "left behind" in migrants' communities of origin.

In recent years, there has been important progress on and reducing exclusionary zoning. Several states have also enacted occupational licensing reform, which facilitates freedom of movement between states. But there is much room for further improvement on these fronts. And when it comes to international migration, we are in a period of horrific regression. That must be reversed as soon as possible.

Workers of the world, unite to demand more freedom of movement!

The post Help Workers by Breaking Down Barriers to Labor Mobility appeared first on Reason.com.

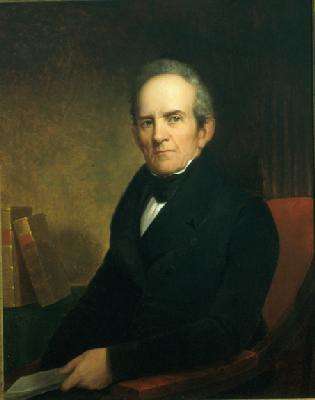

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: September 1, 1823

9/1/1823: Justice Smith Thompson takes judicial oath.

Justice Smith Thompson

Justice Smith ThompsonThe post Today in Supreme Court History: September 1, 1823 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Monday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Monday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

August 31, 2025

[Ilya Somin] New Jersey Town Drops Plan to Condemn a Church to Build a Park and Pickleball Courts

[The mayor abandoned the plan after it aroused strong political resistance and threats of litigation. ]

Christ Episcopal Church, Toms River, NJ.

Christ Episcopal Church, Toms River, NJ.

I have previously written about how the town of Toms River, New Jersey, planned to use eminent domain to condemn the Christ Episcopal Church and build a park and pickleball courts on the spot. The plan seems to have been motivated by a desire to prevent the church from building a homeless shelter on part of its property. In late July, the mayor postponed a scheduled vote on the plan, after it met with widespread opposition, and leading public interest firms specializing in property rights issues (such as the Institute for Justice and the Pacific Legal Foundation) offered to represent the Church in potential legal challenges to the taking. The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty offered to help bring a case under the RLUIPA statute. I outlined some possible grounds for such a challenge here.

Last week, the mayor announced that the plan is being abandoned completely:

His announcement came during the New Jersey town's council meeting's public comment time when a speaker asked him to stop the seizure. He responded that a poll he commissioned showed that "it's pretty clear that the public does not support the eminent domain. We thought the church would be a willing seller and we're not moving forward with the eminent domain of the church."

He said the poll, which he noted had an error rate of plus or minus five, showed that "somewhere in the neighborhood" 60% of the town opposed his plan. (Rodrick had told Episcopal News Service in May that, if the plan had to be put to a vote, he expected 85% of township voters would support it.)

Following the mayor's reversal, the council entered an executive session to seek legal advice on whether it could decide to let the proposed ordinance die, as action on it had not been advertised as legally required. Despite some conflicting opinions from township attorneys, council members unanimously passed a resolution saying they would no longer try to acquire Christ Church's property by eminent domain….

The resolution apparently leaves open the possibility that a new resolution could be brought on the other five lots Rodrick also wants to take for parkland along the Toms River. Those lots are not adjacent to the church.

I think this happy outcome is a small, but notable example of how litigation can be combined with political action to strengthen protection for property rights and religious freedom. I am not sure whether the public opposition or the threat of a lawsuit was more important in forcing the local government to reconsider. But probably it was some combination of both. Seizing a church because it wanted to help the homeless doesn't look good; and if you are a local government trying to get away with a dubious use of eminent domain, IJ and PLF are probably the people you least want to see arrayed against you in court! I commend them for their outreach here.

I have long argued that a dual strategy combining litigation and political action is the right approach to strengthening protection for constitutional property rights, and many other important rights, as well. This incident doesn't, by itself, prove me right. But it's a case in point.

The post New Jersey Town Drops Plan to Condemn a Church to Build a Park and Pickleball Courts appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Sunday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Sunday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

August 30, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Grand Jury Nullification in the District of Columbia?

[Grand jurors in the District of Columbia thrice refuse to indict a defendant for felony assault of a federal officer. And it happened again and again.]

Last week, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia sought to indict Sydney Reid on felony charges of assaulting an FBI agent, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 111.

Here are some of the allegations in the criminal complaint:

4.ERO Officer Vincent Liang gave instructions to REID to step back and allow them to complete the transfer of the two suspects. REID continued to move closer to the officers and continued to record the arrest. Officer Laing reiterated to REID that she could not get any closer. REID got in Officer Laing's face, and he could smell alcohol coming off REID's breath. After multiple commands to step back, REID tried to go around Officer Laing by going up the side steps and attempted to get in between the FBI Agents and the second suspect being transferred into their custody.

5.As REID was trying to get behind Officer Lang and impede the transfer of the second suspect by inserting herself between the second suspect and the agents, Officer Lang pushed REID against the wall and told her to stop. REID continued to struggle and fight with Officer Lang. Agent Bates came to Office Lang's assistance in trying to control REID. REID was flailing her arms and kicking and had to be pinned against a cement wall.

6.During the struggle, REID forcefully pushed Agent Bates's hand against the cement wall. This caused lacerations on the back side of Agent Bates's left hand as depicted below.

A federal magistrate found that there was probable cause to support the charge. Yet, on three occasions, a grand jury in the District of Columbia declined to indict. Instead, the U.S. Attorney filed an information for a misdemeanor violation of Section 111. A writer at MSNBC suggests that the grand jury's refusal to indict may be due to a weak cases being brought by the U.S. Attorney.

Since the failed indictment for Reid, there have been two more grand juries that failed to return a true bill.

It is possible that these juries are carefully attuned to the gradation between felonies and misdemeanors. May I suggest another possibility? Federal grand juries in the District of Columbia, made up (almost) entirely of critics of President Trump, are engaging in nullification of the Trump Administration's law federal enforcement efforts. I imagine this sort of active resistance will increase as more federal officers are fanned throughout the District of Columbia. The Capital likely seems something like this to D.C. residents:

Historically, at least, the concept of jury nullification was viewed as a popular check against tyrannical governments. I imagine an average D.C. resident who can take time off from work to serve extended periods of federal grand jury duty may see himself in that fashion.

During the Jack Smith saga, Trump argued that he could not possibly get a fair jury pool in the District of Columbia. I wonder if the same is true for cases brought by the Trump Administration?

The post Grand Jury Nullification in the District of Columbia? appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers