Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 43

September 4, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Trump's Unjust and Illegal Killing of 11 Venezuelans

[Killing suspected drug traffickers is both unjust and illegal. And it could be the start of an effort to turn the already awful War on Drugs into something more like a real war, thereby making it even worse.]

A General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper practices landings at March Air Reserve Base on Thursday, Aug 17, 2023 in Moreno Valley, Calif. (Dylan Stewart/AP/Newscom)

A General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper practices landings at March Air Reserve Base on Thursday, Aug 17, 2023 in Moreno Valley, Calif. (Dylan Stewart/AP/Newscom)

On September 2, at President Trump's order, US military forces used a drone strike to kill 11 Venezuelans on a small boat in the Caribbean Sea. The claimed justification for this action is that the people on the boat were drug traffickers. Even if that claim is true, the killings were unjust and illegal.

In my view, the entire War on Drugs is fundamentally unjust. It kills and imprisons many thousands of people every year, for no good reason, and in the process stimulates the growth of organized crime and associated violence. It has also severely undermined the Constitution. Under the principle of "my body, my choice," the government should not be in the business of deciding what drugs adults, at least, are allowed to consume. And the way to get rid of drug gangs like Venezuela's Tren de Aragua (TdA) is to end it, just as ending the similarly unjust Prohibition regime was what largely put paid to the organized crime involved in the alcohol trade then. But even if we assume the War on Drugs has some justification, it is a matter of ordinary law enforcement and doesn't justify gratuitously killing people without due process.

US officials admit they could have interdicted the boat and detained the people on board. They did not pose any imminent threat of violence, and they were not combatants in any war against the US. Calling them "narco-terrorists" does not change these obvious facts.

In addition, it is not even clear these people were drug traffickers at all (they might have been migrants fleeing Venezuela's horrible socialist dictatorship). If they were shipping drugs, it is not clear they were going to the US, as opposed to Trinidad and Tobago (which was much closer to their location) or somewhere else. It is not illegal for people on a ship in international waters to transport drugs that are banned in the United States. US law only applies, if at all, if they were planning bring their cargo into US territorial waters.

As GOP Senator Rand Paul put it, "The reason we have trials and we don't automatically assume guilt is what if we make a mistake and they happen to be people fleeing the Venezuelan dictator? … off our coast it isn't our policy just to blow people up … even the worst people in our country, they still get a trial." He's right.

I won't go through the legal issues in detail here, because national security law expert Brian Finucane has already done so in a thorough Just Security article. The bottom line is that these were illegal, extrajudicial killings.

I would call it a war crime, except that there is no war here, despite Trump's (also illegal) efforts to use TdA's activities to invoke the Alien Enemies Act against Venezuelan migrants. So really it's just an old-fashioned regular crime. Perhaps the president has immunity for his part in it under the Supreme Court's dubious immunity ruling in Trump v. United States (which is far from a model of clarity). But if so that just means he can't be prosecuted. It does not not make his actions either legal or right.

I have previously warned against Republicans' dangerous plans to try to turn the War on Drugs into a real war, thereby making an already awful policy much worse (though at that time they seemed more focused on Mexico than Venezuela). We shall have to see if this strike is just the first of a series of similarly terrible actions; administration officials say it may be.

Back in 2013, I testified before a Senate subcommittee on President Obama's use of targeted drone strikes in the War on Terror. Ironically (in light of recent events), I was called as a witness by Republicans who worried that Obama was going too far; some Democrats on the committee also had concerns. I argued that targeted killing of Al Qaeda terrorist leaders was legal and justified (citing precedents like the targeted killing of Admiral Yamamoto and SS General Reinhard Heydrich during World War II) but also that there should be somewhat greater due process to prevent inadvertent targeting of the innocent. See my testimony here.

I have not kept up with this issue in detail since then, instead focusing my writings on other matters). But the concerns I and others expressed at that time apply with much greater force to targeting alleged drug smugglers. And unlike Heydrich, Yamamoto, and Al Qaeda leaders, suspected drug traffickers are simply not proper military targets, except perhaps in rare situations where they are themselves about to launch an attack.

Perhaps, though I am skeptical, evidence will emerge to prove that the people killed in the strike were planning a dangerous terrorist attack, or the like. Otherwise, the president committed an utterly indefensible and criminal act here.

The post Trump's Unjust and Illegal Killing of 11 Venezuelans appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Can American Citizens (e.g., Rosie O'Donnell) Lose Their Citizenship?

[Yes, but only if they intend to relinquish it (or, if they are naturalized citizens and committed fraud during the naturalization process).]

[Originally posted in July, reposted today, with slight changes, in light of President Trump's renewed talk of stripping Rosie O'Donnell of her citizenship: "As previously mentioned, we are giving serious thought to taking away Rosie O'Donnell's Citizenship. She is not a Great American and is, in my opinion, incapable of being so!"]

Let's begin with the constitutional text, here from section 1 of the 14th Amendment:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

Once you have American citizenship, you have a constitutional entitlement to it. If you like your American citizenship, you can keep your American citizenship—and that's with the Supreme Court's guarantee, see Afroyim v. Rusk (1967):

There is no indication in these words of a fleeting citizenship, good at the moment it is acquired but subject to destruction by the Government at any time. Rather the Amendment can most reasonably be read as defining a citizenship which a citizen keeps unless he voluntarily relinquishes it. Once acquired, this Fourteenth Amendment citizenship was not to be shifted, canceled, or diluted at the will of the Federal Government, the States, or any other governmental unit.

(Special bonus in Afroyim: a cameo appearance by a Representative Van Trump in 1868, who said, among other things, "To enforce expatriation or exile against a citizen without his consent is not a power anywhere belonging to this Government. No conservative-minded statesman, no intelligent legislator, no sound lawyer has ever maintained any such power in any branch of the Government.") In Vance v. Terrazas (1980), all the justices agreed with this principle. Your U.S. citizenship doesn't turn on whether the President is of the opinion that you are a Great American.

Now, as with almost all things in law—and in life—there are some twists. Naturalized citizens can lose their citizenship if they procured their citizenship by lying on their citizenship applications; the premise there is that legal rights have traditionally been voided by fraud in procuring those rights. And citizens can voluntarily surrender their citizenship, just as people can generally waive many of their legal rights. This surrender can sometimes be inferred from conduct (such as voluntary service in an enemy nation's army), if the government can show that the conduct was engaged in with the intent to surrender citizenship. The relevant federal statute, 8 U.S. Code § 1481, provides (emphasis added):

A person who is a national of the United States whether by birth or naturalization, shall lose his nationality by voluntarily performing any of the following acts with the intention of relinquishing United States nationality—

(1) obtaining naturalization in a foreign state [as an adult];

(2) … making … [a] formal declaration of allegiance to a foreign state [as an adult];

(3) … serving in … the armed forces of a foreign state if (A) such armed forces are engaged in hostilities against the United States, or (B) such persons serve as a commissioned or non-commissioned officer; or

(4) (A) … serving in … any … employment under the government of a foreign state [as an adult] if he has or acquires the nationality of such foreign state; or

(B) … serving in … any … employment under the government of a foreign state [as an adult] … for which … employment … [a] declaration of allegiance is required; or

(5) making a formal renunciation of nationality before a diplomatic … officer of the United States in a foreign state …;

(6) making in the United States a formal written renunciation of nationality … whenever the United States shall be in a state of war and the Attorney General shall approve such renunciation as not contrary to the interests of national defense; or

(7) [being convicted of] committing any act of treason against, or attempting by force to overthrow, or bearing arms against, the United States, violating or conspiring to violate any of the provisions of section 2383 of title 18 [rebellion or insurrection], or willfully performing any act in violation of section 2385 of title 18 [advocating overthrow of government], or violating section 2384 of title 18 [seditious conspiracy] by engaging in a conspiracy to overthrow … by force the Government of the United States, or to levy war against them ….

But as both the statute and Afroyim make clear, the conduct listed in (1) through (7) will only surrender the person's citizenship if the person engaged in it "with the intention of relinquishing" citizenship. Subsection (b) of this statute provides that "Any person who commits or performs, or who has committed or performed, any act of expatriation under the provisions of this chapter or any other Act shall be presumed to have done so voluntarily, but such presumption may be rebutted upon a showing, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the act or acts committed or performed were not done voluntarily." That presumption is relevant when a person claims that one of the expatriating acts was done under duress, e.g., that he was forced to serve in an enemy army. But

It is important … to note the scope of the statutory presumption. [The subsection] provides that any of the statutory expatriating acts, if proved, are presumed to have been committed voluntarily. It does not also direct a presumption that the act has been performed with the intent to relinquish United States citizenship. That matter remains the burden of the party claiming expatriation to prove by a preponderance of the evidence….

I have no reason to think that O'Donnell has engaged in any of these acts, such as (in her case) "going through the process of obtaining her Irish citizenship through her grandparents," "with the intention of relinquishing United States nationality." American law allows dual citizenship, and "does not require a U.S. citizen to choose between U.S. citizenship and another (foreign) nationality. A U.S. citizen may naturalize in a foreign state without any risk to their U.S. citizenship."

The post Can American Citizens (e.g., Rosie O'Donnell) Lose Their Citizenship? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Putting the Brazil into a Brazilian": Woman Notices Beautician Wearing Meta Smart Glasses

Photo by Immo Wegmann on Unsplash. Relevance explained here.

Photo by Immo Wegmann on Unsplash. Relevance explained here.

A post from Ed Driscoll (at InstaPundit), pointing to a PetaPixel (Matt Growcoot) article:

Ever since the Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses arrived on the market, the elephant in the room has always been: what if someone uses them for clandestine recording?

And it struck one New York woman who was attending a Brazilian wax appointment at the [European] Wax Center and noticed midway through proceedings that the beautician was wearing a pair of the glasses that are capable of recording video and still images….

The European Wax Center … tells the Washington Post that the waxer's glasses were "powered off at the time of service." …

I was quite amused by Ed's summary (the "Putting …" part), and thought I'd pass it along.

The post "Putting the Brazil into a Brazilian": Woman Notices Beautician Wearing Meta Smart Glasses appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] California County's Restriction on Being a Spectator at a Car "Sideshow" Violates First Amendment as Applied to Reporter

[The ruling would apply, I think, to anyone gathering information about the sideshow for publication, whether or not he's a professional journalist.]

From today's Ninth Circuit decision in Garcia v. County of Alameda, by Judge Holly Thomas, joined by Judges John Owens and Mark Bennett; Alameda County contains Berkeley and Oakland:

Driven by concerns over unmanageable crowds, property damage, noise pollution, garbage, firearms use, and reckless driving under the influence of drugs and alcohol, … the County of Alameda … adopted an ordinance prohibiting any person from knowingly spectating a sideshow event conducted on a public street or highway from within 200 feet of that event. Possible penalties include both imprisonment and a monetary fine.

In this pre-enforcement suit, Jose Antonio Garcia, a reporter who writes about sideshows for The Oaklandside under the pen name Jose Fermoso, raises a First Amendment challenge to the County's prohibition as applied to his reporting activities….

The First Amendment protects Garcia's newsgathering and reporting activities. And the County's prohibition on knowingly spectating a sideshow is content based and fails strict scrutiny. Garcia has clearly demonstrated that he is likely to succeed on the merits of his as-applied challenge, that he is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that the balance of equities tips in his favor, and that the issuance of an injunction is in the public interest….

"The Supreme Court has recognized that newsgathering is an activity protected by the First Amendment." And we have determined both that the First Amendment protects recording and photographing "matters of public interest," and that an organization's "recording of conversations in connection with its newsgathering activities is protected speech within the meaning of the First Amendment." These holdings compel the conclusion that Garcia's newsgathering activities—the "quintessential function of a reporter"—are protected by the First Amendment.

The County argues that Garcia's "mere observation" of sideshows "is not expressive." But "[n]either the Supreme Court nor our court has ever drawn a distinction between the process of creating a form of pure speech (such as writing or painting) and the product of these processes (the essay or the artwork) in terms of the First Amendment protection afforded." In other words, "[w]hether government regulation applies to creating, distributing, or consuming speech makes no difference" for purposes of our First Amendment analysis…. "[T]he creation and dissemination of information are speech within the meaning of the First Amendment." …

Here, Garcia's observation of sideshows is a predicate for, and thus inextricably intertwined with, his recording of those events. If the County were permitted to carve out Garcia's observation of sideshows from his recording of those events, it could "effectively control or suppress speech by the simple expedient of restricting" a predicate for "the speech process rather than the end result."

Citing the Supreme Court's decision in Arcara v. Cloud Books, Inc. (1986), the County argues that … the County's restriction on the observation of sideshows "involves only incidental restriction of … speech." In Arcara, the Court upheld against a First Amendment challenge a nuisance statute used to authorize the closure of an adult bookstore on the grounds that the store was the site of ongoing illicit sexual activities. The Court held that "the First Amendment is not implicated by the enforcement of a public health regulation of general application against the physical premises in which respondents happen to sell books." The Court noted that its decision would be different if "the 'nonspeech' which drew sanction was intimately related to expressive conduct protected under the First Amendment.". But because operating an establishment where prostitution is ongoing "bears absolutely no connection to any expressive activity," the Court upheld the closure order.

Arcara is irrelevant to this case. Although the Ordinance "may be described as directed at conduct," as applied to Garcia, "the conduct triggering coverage under the [Ordinance] consists of communicating a message." Holder v. Humanitarian L. Project (2010). Even if observation of a sideshow on its own terms is non-expressive conduct, because Garcia must observe sideshows in order to record them, the Ordinance "burdens [his] First Amendment rights directly, not incidentally."

The County further argues that if the panel agrees with Garcia, "a reporter could seek First Amendment review of speeding regulations preventing her from better filming car chases." But … it is not the case that "any conduct related in some way to speech creation, however attenuated, is necessarily entitled to First Amendment protection." "[W]e need not precisely delineate the extent and contours of First Amendment protection for each constituent act that comprises speech creation" to determine that Garcia's conduct here—recording sideshows as a journalist for the purpose of reporting on them—falls under the ambit of the First Amendment….

"[C]ontent-based laws—those that target speech based on its communicative content—are presumptively unconstitutional and may be justified only if the government proves that they are narrowly tailored to serve compelling state interests." … The Ordinance is content based. It targets only one topic, sideshows, making it a misdemeanor for any person to be present within 200 feet of a sideshow for the purpose of spectating the event. The County does not dispute that a person can observe or record any other topic within that same 200-foot radius as long as they are not "knowingly present to watch the sideshow." A law that "require[s] 'enforcement authorities' to 'examine the content of the message that is conveyed to determine whether' a violation has occurred" in the manner required by the Ordinance here is content based. McCullen v. Coakley (2014).

The County argues that "the Ordinance regulates presence in a particular location[,] … not speech." But this is incorrect. As discussed, the Ordinance does not apply to every person present within 200 feet of a sideshow. As the County has conceded, the Ordinance would not apply to Girl Scout troops who, innocent to a sideshow's occurrence, set up a table to sell cookies within 200 feet of a sideshow event. The Ordinance instead applies only to people present within that range who are knowing spectators of the sideshow. Because the Ordinance does not "require[] an examination of speech only in service of drawing neutral, location-based lines," it is not "agnostic as to content." City of Austin v. Reagan Nat'l Advert. of Austin, LLC (2022)….

Because the Ordinance is content based, it … is presumptively unconstitutional. We will uphold it only if the County meets its burden of showing that the Ordinance "furthers a compelling interest and is narrowly tailored to achieve that interest." …

The Ordinance fails this analysis. Public safety is certainly a compelling interest, and the County cites important concerns about reckless driving, gun violence, illegal drug use, looting, destruction of public property, noise and air pollution, garbage, and traffic disruptions resulting from or accompanying sideshow events. But where a government "'has various other laws at its disposal that would allow it to achieve its stated interests while burdening little or no speech,' it fails to show that the law is the least restrictive means to protect its compelling interest." And, here, there are existing laws that address the County's stated concerns. See, e.g., Cal. Penal Code §§ 187–89, 192 (murder or manslaughter); id. §§ 191.5, 192(c), 192.5 (vehicular manslaughter with or without intoxication); id. §§ 242–43, 245 (assault with a deadly weapon and battery); id. § 246.3 (discharge of firearms); id. § 374 (littering); id. § 415(2) (noise pollution); id. § 451 (arson); id. § 594 (vandalism and destroying infrastructure or other property); Cal. Veh. Code §§ 20001–02 (hit and run); id. § 22500 (blocking intersections); id. § 23103(a) (reckless driving in willful or wanton disregard for the safety of persons or property); id. § 23104 (reckless driving that proximately causes bodily injury or great bodily injury to a person other than the driver); id. § 23105 (reckless driving that injures a person other than the driver); id. §§ 23109, 23109.1, 23109.2 (speed contests with or without resulting injuries); id. § 23152 (driving under the influence

of drugs or alcohol); Cal. Penal Code § 182 (conspiracy to commit any of the foregoing offenses).

The Ordinance also "fail[s] as hopelessly underinclusive." The County argues that "the Ordinance tries to stop people from placing themselves in the path of speeding cars, not to suppress speech about sideshows." Yet the County also acknowledges that, so long as they are not there to spectate, people can "ask for handouts," "advocate for fewer restrictions on sideshows," "stump for a candidate," or, yes, "sell girl scout cookies"—all within 200 feet of a sideshow. Indeed, the County concedes that even Garcia himself "may venture inside a 200-foot radius of a sideshow to interview residents, passersby, spectators, or even drivers, and to record these interviews."

The County contends that "spectators are at greater risk than those present for other reasons" because, "having sought out the sideshow, they are more likely to remain at the scene despite the dangers." But the County cites nothing in support of this argument, and there is no indication in the record that this is true. In particular, the County does not explain why people who might advocate for restrictions on sideshows or come to a sideshow to interview drivers would be any less likely to remain at the site of a sideshow than those there to participate in or observe the event. The lack of such evidence makes clear that the burden on speech imposed by the Ordinance is not "actually necessary to" solve the public safety problems associated with sideshows. The Ordinance thus fails strict scrutiny, and Garcia has made a clear showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits of his as-applied First Amendment claim….

David Loy and Ann Cappetta (First Amendment Coalition) represent plaintiff.

The post California County's Restriction on Being a Spectator at a Car "Sideshow" Violates First Amendment as Applied to Reporter appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Washington Supreme Court Allows a Crime Victim to Intervene in a Criminal Appeal

[Washington's highest court properly recognizes that crime victims can have interests at stake in appellate proceedings in criminal cases. ]

Last week, a divided Washington Supreme Court properly recognized that crime victims can, in appropriate cases, intervene in a criminal appeal brought by a criminal defendant. The Court joins other courts in recognizing that limited-purpose party standing is appropriate for victims when they have interests directly at stake in the appeal.

The case involved a defendant appealing his criminal conviction for second-degree murder, with a finding that it was a crime of domestic violence. In the trial court, the defendant moved to subpoena the medical records of the decedent victim. The mother of the victim (representing the victim's interests) intervened and objected. The defendant did not object to the mother's intervention at the trial court and, in fact, agreed that she had the right to oppose his motions. The trial court denied the defendant's motions to obtain the records, and he was convicted. His challenge to the conviction reached Washington's appellate courts, and the Washington Court of Appeals allowed the mother to intervene to oppose access to her daughter's medical records.

The Washington Supreme Court affirmed the decision allowing the intervention:

[Defendant] argues that on appeal he now faces two respondents and, in effect, "'two prosecutors.'" However, this is no different from the situation at the trial court level. Moreover, it is incorrect to characterize [the mother] as a second prosecutor. Instead, [the mother's] role in the appeal is limited in the same manner as it was in the trial court: the only issue she may address is whether [defendant] should be allowed access to her daughter's health care records. Justice Gordon McCloud makes a similar argument in the dissent, pointing out that it is the prosecutor who decides whether to bring an action and, if so, how that action is pursued. That is correct. The prosecutor's ability to decide strategy is not affected by our holding. Instead, our holding provides the Court of Appeals with the discretion to allow a person to continue seeking to protect health care records on appeal when they were allowed to do so at the trial level.

The dissent acknowledges that [the mother] could have brought a separate civil lawsuit to quash any attempt by [the defendant] to subpoena her daughter's health care records and that she had the right to appeal any adverse ruling. The dissent fails to explain the functional difference to [defendant] if [the mother] had brought a civil action that quashed any subpoenas issued by the court in the criminal action. Justice Gordon McCloud suggests that the civil action would only determine whether the health care records are confidential, which she concedes is not a debatable question—they are. Justice Gordon McCloud likewise assumes that the court in the civil action would not consider the reasons Mr. Thompson is seeking those records. On the contrary, a court faced with a motion to quash must consider all the arguments as to why the subpoena should be issued, together with all arguments against the issuance of the subpoena.

The decision allowing intervention by a crime victim with interests at stake makes considerable sense, and is in line with other decisions by courts facing similar issues. For example, in my home state of Utah, the Utah Supreme Court has recognized the right of a victim to seek restitution—and appeal if restitution is denied. The Utah Supreme Court held that

As an initial matter, we concede a general point advanced by [the defendant]: The traditional parties to a criminal proceeding are the prosecution and the defense, and a crime victim is not that kind of party; a victim is not entitled to participate at all stages of the proceedings or for all purposes. But that does not eliminate the possibility that a victim may qualify as a limited-purpose party—with standing to assert a claim for restitution. And we conclude that crime victims possess that status under our law.

The right of crime victims to effectively enforce rights with on-going criminal proceedings is one of the most significant changes in criminal justice in America over the last several decades, as I have chronicled in my recent article on the crime victims' rights movement. Washington's decision last week is another illustration of that important trend.

The post Washington Supreme Court Allows a Crime Victim to Intervene in a Criminal Appeal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "The Souterian and Rehnquistian Views of Legal Talent"

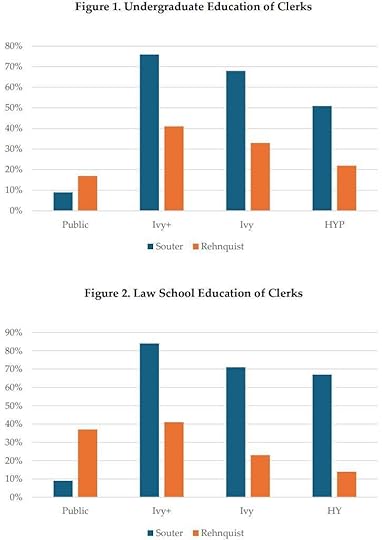

From a new law review article with that name, by Andy Smarick (Manhattan Institute):

During congressional testimony in 1999, the late Justice David Souter explained that only those who graduated from one of the nation's most elite law schools would be qualified for a precious Supreme Court clerkship. He considered it risky to hire from "outside the well-trodden paths." Earlier in the same hearing, he referred to Chief Justice Rehnquist's well-known and different view: that the top performers at a wide array of law schools are "fungible." That is, the most elite schools might have more of the highest-ability students, but extraordinary talent can be found far and wide.

These competing visions of legal potential are reified by Justice Souter's and Chief Justice Rehnquist's actual histories of clerk hiring. Since 1980, no justice pulled from a narrower sliver of schools than Justice Souter; Chief Justice Rehnquist hired from one of the largest pools. This finding, however, is not limited to these two justices or even to justices on the United States Supreme Court. On the contrary, the legal profession appears split between the elitist Souterian vision and the egalitarian Rehnquistian vision.

The consequence is two distinct prestigious legal circles. One has graduates of a vast array of undergraduate and law schools, including flagship public schools, regional public schools, small liberal arts schools, larger selective private schools, and more. The other is dominated by graduates of a strikingly slender set of private institutions, namely Ivy and "Ivy+" schools. {My studies follow the recent convention of adding four highly selective private schools (Chicago, Duke, MIT, and Stanford) to the eight Ivies to form an "Ivy+" category.}

At least two factors seem to have created and maintained these separate circles. The first is the education of "choosers," the gatekeepers for elite professional roles. When Ivy+ graduates are in charge, they overwhelmingly hire Ivy+ graduates. They seem to hold the Souterian view that talent is concentrated in the types of schools they attended (Justice Souter graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Law School). When choosers are educated at a broader array of schools, the Rehnquistian vision predominates: individuals are hired from a broader array of schools.

The second factor is geography. In most of the nation, the top ranks of the legal profession are mostly filled by individuals from nearby public and private universities. Ivy+ graduates are few and far between. In only a few states, such as California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York, are Ivy+ degrees prevalent.

The existence of two elite legal circles—and the reasons why they both exist—matters. First, as a practical matter, it affects the opportunities (or lack thereof) available to law students and early-career lawyers. Although the top graduates of non-Ivy+ schools can rise to professional prominence in the legal community across most of America, they are at a severe disadvantage in a few locations and when Ivy+ graduates are in charge of hiring decisions. For instance, Ivy+ justices are significantly less willing to hire clerks from non-Ivy+ schools. As such, talented graduates of most of America's colleges and law schools appear to be systemically denied a fair shot. This also means that some of our legal institutions have a paucity of talented individuals from such schools.

Second, these two elite legal circles, because they have different educational profiles, may well differ in other meaningful, predictable ways. For instance, affluent, connected students have an advantage in the Ivy+ application-and-acceptance process. Those students then spend years on campuses located in a sliver of America and with cultural sensibilities different than much of America. They then disproportionately build careers in a handful of East Coast, urban settings (e.g., Boston, New York, Washington, D.C.). This is not the experience of most legal leaders.

America could, as a result, have two elite legal circles with significantly different instincts about religion and technocracy, knowledge of rural America and regional traditions, and views on politics, federalism, localism, civil society, and so on. At minimum, we should recognize the possibility, perhaps the likelihood, that these different legal circles think differently about law and policy. In what follows, I describe the differences between the "Souterian" and "Rehnquistian" views of talent, show how these differences manifest in a variety of important legal roles at the federal and state level, and describe the influence of several notable factors, including geography, ideology, and "feeder judges." …

I will close with one question and two observations. The question relates to whether and how this difference in educational profiles manifests in different professional decisions and behavior. Future research should study the extent to which these different circles reflect different politics, cultural sensibilities, and more due to their members' different academic backgrounds. It is hard to justify different segments of the legal community's top ranks having dramatically different backgrounds. But if that is the case, we should be aware of it and understand the consequences.

The first observation is that many public and non-Ivy+ private schools are producing outstanding future leaders even though those schools' graduates are all but ignored by Souterian selectors. That is, non-Ivy+ justices and selection systems in most states find talented individuals in non-Ivy+ schools to serve in important posts. The most prominent of those schools are flagship public universities. For instance, University of Mississippi School of Law currently has nine graduates on state supreme courts. Only Harvard Law and Yale Law have more graduates as state justices. But only one Mississippi Law graduate has been a Supreme Court clerk since 1980. In that same time, Harvard Law and Yale Law have had 748 clerks combined.

The law schools of Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, West Virginia, Wyoming, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arkansas educated thirty-six current state supreme court justices. But not a single Supreme Court clerk in the last forty-five years came from any of those schools. The list of undercapitalized non-flagship publics includes Arizona State, Purdue, Michigan State, Miami (Ohio), and UCLA. The list of undercapitalized private universities includes Boston College, BYU, Creighton, Denver, Drake, Marquette, Seton Hall, St. Olaf, and Willamette University.

The other observation is that the Souterian approach to talent shortchanges countless individuals. Extraordinarily able seventeen-year-olds choose to go to non-Ivy+ colleges for many reasons. Many excel at those schools as undergraduates. Many top graduates of non-Ivy+ colleges choose to go to non-Ivy+ law schools for many reasons. Many excel at those law schools. These individuals will find leadership opportunities in some places, but they will be at a severe disadvantage when Souterians are in charge. Of Justice Souter's ninety clerks only three were double-public graduates. Of Justice Kagan's sixty-one clerks, only one was a double-public school graduate.

To be a Rehnquistian does not mean discriminating against the graduates of elite private schools. Indeed, in most Rehnquistian states, Ivy+ graduates are still overrepresented in legal leadership roles. The most Rehnquistian justices—Rehnquist included—hire a significantly higher percentage of Ivy+ college and law school grads than the Ivy+ percentage of the college- and law-school-graduate population. But being a Rehnquistian does mean looking for and hiring talented individuals from a wide array of schools. It is not clear whether Souterians doubt the existence of such individuals or whether they are not interested in looking for or hiring them. Whatever the reason, it can, and should, change.

The post "The Souterian and Rehnquistian Views of Legal Talent" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Dale Carpenter] Documenting Denial: A Record of Rejection Faced by Gay Couples

[Over the past two decades, scores of business owners across the nation have sought to refuse services for same-sex weddings, an SMU Law School study finds]

Of course you know about the website designer who didn't want to create sites for gay weddings. You probably remember the Colorado baker who declined to make a custom wedding cake for a gay couple. Perhaps you even recall the New Mexico photographers who refused to take pictures of a lesbian commitment ceremony.

But did you know about the stylist in Tennessee who refused to cut hair or apply makeup to the women in a wedding party for two men? Or the instructor in Missouri who spurned two grooms seeking dance lessons for their ceremony because it "would make everyone else in the room uncomfortable"? It's unlikely you've heard about the North Carolina trolley company that turned down, on religious grounds, a request to transport a gay couple to their wedding ceremony in a remote mountainous location?

For the past five years, with the invaluable help of my research assistants at SMU Dedman School of Law, I've been collecting all publicly known stories of same-sex couples who were denied wedding goods or services by private business owners that object to gay marriage. The compendium of cases is collected in a new website called, Documenting Denial: A Record of Wedding Services Denied to Same-Sex Couples Since 2004. As best I can tell, this is the first published attempt to compile such a record.

I. What is the Project?

On the website, the project is described as follows:

In 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States held in 303 Creative v. Elenis that Colorado could not compel a website designer to create wedding websites for same-sex couples. The 6-3 majority reasoned that forcing a designer to create messages with which she disagrees would violate her First Amendment right to freedom of speech. The decision marked the first time the Court ruled that a for-profit business in the public marketplace could be exempt from the requirement to serve customers protected from discrimination by state law.

Twenty years earlier, in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health (2003), the Massachusetts state supreme court became the first in the country to declare laws against same-sex marriage unconstitutional. By 2004, the first official marriage licenses in the United States were being issued to gay and lesbian couples. Other states followed, although most states resisted. In Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the Supreme Court recognized a federal constitutional right of same-sex couples to wed. Today, the number of same-sex marriages in the U.S. approaches one million.

Some of these couples have faced rejection from vendors when seeking goods and services related to their weddings or commitment ceremonies. Vendors have declined flowers, photography, wedding cakes, venues, tailoring, and more based on their personal and religious beliefs that marriage should not include same-sex couples.

The scope of the project

Our project is an attempt to document all publicly known examples of these denials. By "publicly known," we mean those denials accessible to the public through online media sources and public records of litigation. Our list also includes preemptive lawsuits filed by business owners seeking to establish or to clarify their right to refuse goods and services. In almost every instance we've listed, it is undisputed that a wedding-related service or good was actually denied. The claimed basis for the denial, the vendor's objection to same-sex marriage, is also almost always undisputed.

The record covers the period since 2004, the year that the first legal same-sex marriages began in the United States. It includes only denials by vendors in the business of providing such goods or services, not denials by judges or religious leaders refusing to officiate or by state officials refusing to issue marriage licenses. The record compiled here includes both denials that resulted in litigation and those that did not.

As part of the record, we want readers to know the who, what, where, when, and why of these denials. Accordingly, we offer a factual summary of the denial, the names of the parties involved on both sides, the locations and dates of each controversy, the particular product or service involved, whether litigation ensued, and the outcome. Links to relevant public records, like newspaper accounts and court opinions, are provided.

For a more visual experience of the scope and extent of the record, we have prepared a map showing the spread of denials across the nation and across the decades.

Finally, we invite readers to send us corrections and additions.

In essence, there are two ways to view the compilation of denial cases. One is by going to a chart (which we call the "Record") that gives detailed information about each case: a synopsis of the facts, the location and date of the denial or initial lawsuit filing, the type of wedding service or good involved, the names of the parties (both customers and business owners), the reason for the denial (religious, personal, or other), information about subsequent litigation (if any), and links to news articles or court opinions about the case. A color-coding scheme allows you to see quickly which of the listed denials resulted in litigation (pink), which of the denials resulted in no litigation (green), and which involved pre-enforcement actions by businesses where no actual denial occurred (blue).

The other way to view the compilation of cases is to peruse an interactive Map that allows you to click on the various locations in the country or to scroll through the cases chronologically. The Map is a good way to get an overview of the cases. You can then go the Record to find more detailed information about each case.

II. What We Found

In all, since Massachusetts became the first state to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples in 2004, we found 64 cases of private businesses declining, or seeking to decline, goods or services for gay weddings or similar events (e.g., a commitment ceremony or a renewal of vows). Ten of those 64 cases involved businesses filing preemptive lawsuits to clarify or establish their legal right to refuse such services, although no actual denial had yet occurred.

Thus, we found 54 denials that have actually occurred since 2004 ("actual denial cases"). In 52 of the 54 cases, there was apparently no dispute between the customers and the business about whether there was a denial or about whether the basis for the denial was an objection to same-sex marriage.

As you'll see from the Map, the cases are spread out geographically. They stretch from east to west, north to south, and everywhere in between. They appear in big cities, small towns, and rural areas. The first case we could find in the public record--the New Mexico photographers who refused to take pictures of a lesbian couple's commitment ceremony--arose in 2006. The most recent came in November 2024. There are no significant trends in the frequency of denials over time. Four cases have arisen since the Supreme Court's decision in 303 Creative v. Elenis (2023). Only one of those is being litigated.

Of the 54 actual denial cases, 39 (72%) involved no lawsuit. In most of these 39 unlitigated cases, there was no relevant legal protection for same-sex couples available in the particular jurisdiction. Fifteen actual denial cases (28%) resulted in litigation.

What types of good or services have been the subject of these denials? By far the most common site for disputes has been the wedding venues themselves: 26 of the 64 overall cases (41%) have involved business owners refusing to rent their spaces for same-sex weddings. This is followed by disputes with wedding cake bakers (10), photographers (7), videographers (4), dressmakers and tuxedo makers (4), florists (2), caterers (2), wedding planners (2), and one each for a newspaper refusing same-sex wedding announcements, a calligrapher, a hairstylist, a dance instructor, a trolley operator, and the celebrated website designer who was the subject of 303 Creative.

What was the stated basis for denying wedding services to same-sex couples? The vast majority of business owners, 54 out of 64 overall cases (84%), cited religious beliefs as their primary objection to same-sex marriage. Most of these religious objectors were self-described Christians. The remaining ten business owners characterized their opposition as personal or legal, or did not specify a reason.

III. Why the Record Matters

Here's what we said on this topic at the Documenting Denials website:

Marriage is an important milestone in a person's life. It helps cement relationships, meets needs, and reflects religious and personal values. Its meaning matters to almost everyone—the couple, their children, their families, their friends, their faiths, and their societies. Participating in and supporting the wedding itself is an act loaded with significance for everyone.

It's no wonder that people on both sides have claimed strong interests for their respective positions. Same-sex couples want equal access to wedding services in the open marketplace and equal treatment from the vendors they select. They also do not want to be insulted at this uniquely sensitive and anxiety-laden time. Wedding vendors with religious or other objections to same-sex marriage want to run their businesses without violating their consciences and want to preserve their freedoms of speech and religion.

Knowing the number, locations, dates, and outcomes of actual denials helps to inform the debate about the significance and extent of the claims on each side. The record will help inform the public, attorneys, judges, and scholars about the kinds of services that are most often denied.

From the exchange of rings to the tossing of the bouquet, symbolism pervades almost every aspect of a wedding. But these are usually thought of as the expressions of the couple, not of the ringmaker or the florist. The Supreme Court declared in 303 Creative that, at least in some cases, providing the good or service amounts to expression by the business, which cannot be compelled by state law. Recounting the circumstances and context of actual cases may help sharpen the questions and settle the answers of what services or goods are sufficiently part of the wedding vendor's own expression to merit constitutional protection.

We shouldn't lose sight of the real people involved in these cases. The stakes were high for the couples who were denied services. Even if they obtained the services elsewhere--and it appears that in all or almost all cases they did--they bore the anxiety, time, and expense of having to do so. And they were figuratively slapped in the face at what should have been a joyous time in their lives.

The stakes were also high in these cases for the objecting business owners. They had the choice of either serving the weddings and foregoing their convictions or denying the services and dealing with the fallout. Public pressure forced some of them out of business. Others had to defend themselves in court, and some of these ended up losing. Even if they prevailed, courts dragged out their cases. One Oregon baker who declined a wedding cake for a lesbian couple in January 2013 (when Barack Obama was beginning his second term) is still awaiting final word from the Oregon courts more than 12 years later. Even then the case will probably go back to the U.S. Supreme Court for possible review a second time. It's now zombie litigation: the bakery closed in 2016.

At the same time, it's important to keep the record in perspective. We found 54 actual denial cases over a 20-year time span, fewer than three per year on average. That may seem like a lot compared to the mere handful of cases most people have heard about. But consider that, at the upper range, Gallup estimated there were 930,000 same-sex marriages in the U.S. as of June 2025. At the lower end of the range, the Williams Institute at UCLA estimated there were 823,000 married same-sex couples in the United States as of June 2025.

Given those numbers, it's a safe bet that there have been close to one million same-sex marriages performed in the United States since 2004. Of course, not all of these married couples held weddings at which commercial services or goods were needed or desired.

By any reasonable reckoning, the 54 publicly known cases of actual service denials that we found are likely a tiny fraction of the total number of weddings at which gay couples called on service providers for venues, cakes, photographers, florists, and the innumerable other professionals who make weddings their business. Many of these couples self-selected their providers, opting for those they knew to be open to gay couples. But the logical inference from these numbers is that the vast majority of gay couples and wedding businesses have had no difficulty engaging in these particular commercial exchanges. Markets tend to value profit over identity or moral judgment.

IV. Limitations and ongoing efforts

With that perspective in mind, it's also important to highlight some limitations of this study. We aim to catalogue only publicly known instances of wedding-service denials. Again, by "publicly known," we mean those denials accessible to the public through online media sources (like newspapers and social-media sites) and public records of litigation.

There are doubtless many cases of actual denial where the rejection never surfaced publicly. It's possible the cases we've collected are the tip of an iceberg. Short of conducting broad surveys or doing other research, our review could not capture these private acts of denial. It also cannot capture the full impact of discrimination in the wedding-service industry, which would include cases where gay couples altogether avoid a provider because they fear rejection or cases where providers hide the true reason for denials.

This project is ongoing. We will update Documenting Denial as needed. To that end, we invite readers to send corrections and additions to: documentingdenial@smu.edu. If making suggestions for additional cases that should be added, please send links or other documentation supporting the additions.

Finally, I want to thank the following SMU Law students who gave countless hours and boundless devotion to this project over the past five years: Jaishal Dhimar, Sarah Fisher, Emily Fletcher, Ryan Fulghum, Lauren Jasiak, Kaci Jones, and Sarah Starr. Their excellent work will continue to inform this controversy long past their law school graduations.

The post Documenting Denial: A Record of Rejection Faced by Gay Couples appeared first on Reason.com.

September 3, 2025

[Ilya Somin] Fifth Circuit Rules Trump's Use of Alien Enemies Act is Illegal

[The 2-1 ruling is in line with most previous court decisions on Trump's invocation of the AEA. Judge Oldham wrote an extremely long, but significantly flawed, dissent.]

A prison guard transfers Alien Enemies Act deportees from the U.S., alleged to be Venezuelan gang members, to the Terrorism Confinement Center in Tecoluca, El Salvador. Mar. 16, 2025 (El Salvador Presidential Press Office)

A prison guard transfers Alien Enemies Act deportees from the U.S., alleged to be Venezuelan gang members, to the Terrorism Confinement Center in Tecoluca, El Salvador. Mar. 16, 2025 (El Salvador Presidential Press Office)

Yesterday, in W.M.M. v. Trump, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that President Trump's invocation of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as a tool to deport Venezuelans is illegal. While multiple federal district courts have issued similar rulings, as have individual concurring opinions by judges on two other circuit courts, this is the first full-blown appellate court decision on the subject. It is therefore an important precedent. There is a lengthy 130 page dissenting opinion by Judge Andrew Oldham. But it's serious flaws merely confirm the weaknesses of the government's position.

The AEA allows detention and deportation of foreign citizens of relevant states (including legal immigrants, as well as illegal ones) "[w]henever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government." Trump has tried to use the AEA to deport Venezuelan migrants the administration claims are members of the Tren de Aragua drug gang.

The Fifth Circuit majority opinion by Judge Leslie Southwick (a Republican George W. Bush appointee) holds that TdA's activities - drug smuggling, illegal migration, and related crimes - don't qualify as an "invasion" or a "predatory" incursion and therefore the AEA cannot be used here. Everyone agrees there is no declared war.

On the definition of "invasion," Judge Southwick concludes, after a review of the evidence:

Congress's use of the word in the AEA is consistent with the use in the Constitution, that "invasion" is a term about war in the traditional sense and requires military action by a foreign nation. Petitioners have the sense of the distinctions in saying that responding to another country's invasion is defensive; declaring war is an offensive, assertive action by Congress; and predatory incursion is for lesser conflicts. Of course, after this country has been attacked by an enemy with invading forces, Congress might then declare a war. That occurred in World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Still, when the invasion precedes a declaration, the AEA applies when the invasion occurs or is attempted. Therefore, we define an invasion for purposes of the AEA as an act of war involving the entry into this country by a military force of or at least directed by another country or nation, with a hostile intent.

Every other court to have ruled on the definition of "invasion" has reached similar conclusions, and I argue for that conclusion in the amicus brief I coauthored in W.M.M. on behalf of the Brennan Center, the Cato Institute, and others.

Here is the Fifth Circuit on the definition of "predatory incursion":

These different sources of contemporary meaning that we have identified from dictionaries, the writings of those from the time period of the enactment, and from the different requirements of the Alien Enemies Act and the Alien Friends Act, convince us that a "predatory incursion" described armed forces of some size and cohesion, engaged in something less than an invasion, whose objectives could vary widely, and are directed by a foreign government or nation. The success of an incursion could transform it into an invasion. In fact, it would be hard to distinguish some attempted invasions from a predatory incursion.

This too is similar to previous court decisions, and to the approach outlined in our amicus brief, which explains that a "predatory incursion" is a smaller-scale act of war. The one exception is a district court opinion that adopted an extremely broad definition of "predatory incursion," which I critiqued here.

The majority also persuasively argues that the definitions of "invasion," "predatory incursion" and other statutory terms are not unreviewable issues simply left to executive discretion.

The majority does, however, rule that courts must, to a degree, defer to presidential fact-finding regarding whether an "invasion" or a "predatory incursion" is occurring. It concludes, here, that the facts alleged in the President's Proclamation do not meet the requirements of the correct definition of that term. This may leave open the possibility that the president could simply legalize the AEA by claiming the existence of different (more egregious) "facts," even if the claims are patently false. I have criticized excessive deference on such factual issues in this recent article, and in the amicus brief. Deference on factual questions should not allow the president to invoke extraordinary emergency powers merely by mouthing some words and making bogus, unsubstantiated claims.

That said, the majority does suggest that factual deference must be limited:

The Supreme Court's recent J.G.G. opinion shows Ludecke is to be understood as requiring courts to interpret the AEA after the President has invoked it…. Interpretation

cannot be just an academic exercise, i.e., a court makes the effort to define a term like "invasion" but then cannot evaluate the facts before it for their fit with the interpretation. Thus, interpretation of the AEA allows a court to determine whether a declaration of war by Congress remains in effect, or whether an invasion or a predatory incursion has occurred. In other words, those questions are justiciable, and the executive's determination that certain facts constitute one or more of those events is not conclusive. The Supreme Court informs us that we are to interpret, and we do not create special rules for the AEA but simply use traditional statutory interpretive tools.

If courts must "use traditional… interpretive tools" and "determine… whether an invasion or a predatory incursion has occurred," they cannot simply blindly acquiesce to whatever factual claims the government might make, no matter how specious. Otherwise, interpretation will indeed become "just an academic exercise."

Prominent conservative Judge Andrew Oldham wrote a lengthy 130 page dissent. He's undoubtedly a highly capable jurist. But his herculean efforts here just underscore the radical and dangerous nature of the government's position.

Surprisingly, Judge Oldham doesn't seriously dispute the definitions of "invasion" and "predatory incursion." He just argues that these issues are left to the completely unreviewable discretion of the executive. If that's true, the president could use the AEA to detain or deport virtually any noncitizens he wants, at any time, for any reason, so long as he proclaims there is an "invasion" or "predatory incursion," regardless of whether anything even remotely resembling these things is actually happening. A power that is supposed to be used only in the event of a dire threat to national security would become a routine tool that can be deployed at the president's whim.

And, under Judge Oldham's analysis, the president also could deport and detain these people with little, if any, due process. He contends the government has no obligation to prove that the people detained are actually TdA members. And in fact there is no evidence that most of those deported under the AEA are members of the gang or have committed any crimes at all. Thus, Judge Oldham is essentially claiming the AEA gives the president unlimited, unreviewable power to detain and deport non-citizens - including legal migrants - whenever he wants (again, so long as he proclaims the right words).

Nothing in the text or history of the AEA even approaches this. Instead the text says that the AEA can only be used when a war, invasion, predatory incursion or threat thereof, exists, not merely when the president says so.

Oldham argues in detail that various precedents require the latter outcome. But, as the majority notes, those precedents - including the Supreme Court's recent decision in J.G.G. specifically indicate that there is room for judicial review. Moreover, if the AEA really did grant the president such unlimited power, one would have expected contemporaries in 1798 to point that out and object on constitutional grounds, as they did in the case of the contemporaneous Alien Friends Act, which really did give the president sweeping deportation and detention powers, even in peacetime, and which was duly denounced as unconstitutional by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, among others. The Alien Enemies Act, by contrast, was far less controversial, precisely because it was understood to be limited to genuine wartime situations, not anything the president might speciously label as such.

Moreover, under Suspension Clause of the Constitution, in the event of an "invasion," the federal government can suspend the writ of habeas corpus, and thereby detain people - including US citizens - without any due process. There is no way the Founders understood themselves to have given the president unreviewable authority to trigger that power anytime he wants.

I won't try to go through all of Judge Oldham's analysis of precedent here. But I will give one example of how problematic it is. The judge argues that Supreme Court's 1862 decision in The Prize Cases gives the president unreviewable authority to determine there is a war going on, and exercise war powers accordingly. The majority opinion in that case does no such thing. Rather, it emphasized the fact that then-ongoing Civil War was a conflict "which all the world acknowledges to be the greatest civil war known in the history of the human race." Thus, President Lincoln's power to establish a blockade in response could not be negated by "by subtle definitions and ingenious sophisms."

The Court then went on to make the point cited by Oldham:

Whether the President, in fulfilling his duties as Commander-in-chief in suppressing an insurrection, has met with such armed hostile resistance and a civil war of such alarming proportions as will compel him to accord to them the character of belligerents is a question to be decided by him, and this Court must be governed by the decisions and acts of the political department of the Government to which this power was entrusted. "He must determine what degree of force the crisis demands." The proclamation of blockade is itself official and conclusive evidence to the Court that a state of war existed which demanded and authorized a recourse to such a measure under the circumstances peculiar to the case.

But notice the president only gets deference on the question of whether the "insurrection" he is "fulfilling his duties" by combatting is one of "such alarming proportions" as to justify a wartime blockade. He does not get deference on the question of whether an insurrection exists in the first place (in that case, as the Court noted, it obviously did). Had Lincoln instead imposed a blockade to prevent, say, illegal smuggling of contraband goods and then claimed smuggling qualifies as war, he would not get the same deference.

Judge Oldham's reliance on other precedents has similar flaws. Nearly all of them also arose from genuinely massive wars, not attempts to pass off drug smuggling or other similar activity as an "invasion." Oldham complains that "[f]or over 200 years, courts have recognized that the AEA vests sweeping discretionary powers in the Executive," and that "until President Trump took office a second time, courts had never countermanded the President's determination that an invasion, or other similar hostile activity, was threatened or ongoing." But the AEA has previously only been invoked in connection with three indisputable international conflicts: the War of 1812, World War I, and World War II. You don't have to be an expert to see the difference between these conflicts and the activities of a drug gang.

The majority, the concurring opinion by Judge Ramirez, and the dissent also address a number of other issues, particularly various procedural questions. I will pass over them for now, as this post is already long.

The Trump administration may well appeal this case to the Supreme Court. If the Court takes it, I hope they, too, will recognize that the AEA doesn't give the president a blank check to wield sweeping extraordinary power whenever he wants.

In the meantime, litigation over this issue continues in various federal courts around the country.

The post Fifth Circuit Rules Trump's Use of Alien Enemies Act is Illegal appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Another Boston Judge Pushes Back Against Supreme Court Emergency Docket Ruling

[The Lower Court Revolt Continues.]

Remember Massachusetts District Court Judge Allison Burroughs? She wrote the opinion finding that Harvard engaged in no discrimination against Asian students and minimized the effect of some damning Admission Office emails. The Supreme Court roundly rejected her findings of facts in Students for Fair Admissions. As Justice Sotomayor pointed out in dissent, Chief Justice Roberts failed to "review the District Court's careful fact-finding with the deference it owes to the trial court." With good reason.

Fast forward to the Trump Administration. By luck of the draw, Judge Burroughs was assigned Harvard's funding case against the executive branch. Judge Burroughs issued an ex parte TRO in the funding case so quickly, that she could not have possibly even read the briefs. Judge Burroughs was also assigned the Harvard student visa case. How random? And she issued another immediate ex parte TRO. Not to be outdone, Boston Judge Talwani issued an immediate ex parte TRO in favor of Planned Parenthood, blocking the funding provisions of the One Big Beautiful Bill.

What is going on with Boston? Is there something in the Charles River?

Maybe there should be a rule that a TRO cannot be granted until at least enough time has elapsed so a reasonable person could actually read all the filings. They can even hang out at an all-night Denny's to finish their review. Sometimes when I receive a long email that I don't want to read, but I don't want the person to think I skipped it, I schedule a response for the following morning thanking the reader for the message. That approach at least creates the appearance that I took the matter seriously.

Today, Judge Burroughs issued a decision finding that in fact the Trump Administration threatened funding cuts would violate Harvard's rights under the First Amendment and Title VI. Critically, the court ruled that the case belongs in Boston, and not in the Court of Federal Claims. Where have I heard this before? Oh yeah, in DHS v. D.V.D. and in NIH v. APHA. Just yesterday, another Boston federal judge apologized for not knowing that emergency docket orders were precedential.

What did Judge Burroughs do? She took Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh to task for calling out lower judges in NIH v. APHA. Consider this remarkable passage in a footnote:

. . . This Court understands, of course, that the Supreme Court, like the district courts, is trying to resolve these issues quickly, often on an emergency basis, and that the issues are complex and evolving. See Trump v. CASA, Inc., 145 S. Ct. 2540, 2567 (2025) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring) ("In justiciable cases, this Court, not the district courts or courts of appeals, will often still be the ultimate decisionmaker as to the interim legal status of major new federal statutes and executive actions."). Given this, however, the Court respectfully submits that it is unhelpful and unnecessary to criticize district courts for "defy[ing]" the Supreme Court when they are working to find the right answer in a rapidly evolving doctrinal landscape, where they must grapple with both existing precedent and interim guidance from the Supreme Court that appears to set that precedent aside without much explanation or consensus.

"Unhelpful" and "Unnecessary." I don't recall ever seeing a federal judge push back against a Supreme Court justice in an opinion. I think after years of rantings about the "shadow docket," even federal judges have decided that their superior body is a fair target. Judge Burroughs may as well have painted a bullseye in Red Sox red on the imminent stay application. At least Judge Reinhardt tried to keep things on the down-low so SCOTUS couldn't catch them all.

The lower court revolt continues. I'll repeat my conclusion from my Civitas column: John Roberts faces a far greater threat from a lower court revolt, than from President Trump, who has pledged allegiance to SCOTUS.

I attended Professor Mascott's confirmation hearing this morning. Several senators brought up Justice Gorsuch's concurrence. He struck a nerve. This issue is not going away.

The post Another Boston Judge Pushes Back Against Supreme Court Emergency Docket Ruling appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] How Would You Know If a Justice Issues A Wise, Solomonic Ruling?

[Here's looking at you, Chief.]

The Free Press published an extended excerpt from Justice Barrett's new book. Justice Barrett develops at some length the theme of King Solomon. She reminds readers that Solomon never actually cut the baby in half. Rather, his wisdom was putting forward a test that would identify the real mother, without having to murder the child. And that test has endured for milennia. Barrett writes:

"Doing justice" doesn't call to mind a judge parsing statutory language; it sounds more like King Solomon, who famously mediated the dispute between two women claiming the same baby. In a brilliant (if high risk) strategy, Solomon proposed to divide the baby in half, betting that the true mother would relinquish the child rather than see him die.

Fortunately, Solomon was right. And because he achieved the just result, the Old Testament memorializes this story to illustrate Solomon's wisdom. In fact, Solomon is also honored on a frieze in the courtroom of the Supreme Court, where he appears as one of the "great lawgivers of history."

Barrett goes on to say that King Solomon is not the right model for a federal judge. Federal judges do not decide cases based on internal wisdom, but they decide cases based on external law.

It's notable to me that Solomon's wisdom came from within. He didn't resolve the case by turning to sources like laws passed by a legislature or precedents set by other judges. Nor was there any limit to the kind of solution he could impose—after all, his proposed remedy was to literally split the baby. Solomon's authority was bounded by nothing more than his own judgment. But that wasn't cause for concern, because the man and wise rule were one and the same.

If you'd asked me before law school, I may well have identified Solomon as the ideal judge. And in a certain respect, he is—it's appealing to entrust a dispute to someone who resolves it with reference solely to principles of justice. Solomon, however, stands out for a reason: His wisdom was flawless. Those who framed and ratified the Constitution didn't expect the same to be true of federal judges.

Barrett is exactly right here. Indeed, I have difficulty with the fact that the slogan chiseled into stone atop the Supreme Court is "Equal Justice Under Law." That phrase has no home in any legal authority. It was proposed by the architects of the Supreme Court. I suppose it is technically correct that the justice must be done under some type of written law, but that phrase conveys all the wrong message to litigants. The job of a judge is not to dispense justice, as she sees it.

Justice Barrett's point brings to mind a rather infamous statement made repeatedly by then-Judge Sonia Sotomayor. She would often say that a "wise Latina woman with the richness of her experience would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn't lived that life." King Solomon could perhaps draw on his wisdom, but federal judges should not. Then again, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson recently described "equal justice under law" as "this Court's guiding light nearly a century after those words were first engraved there." Not quite.

Barrett continues to develop the Solomon theme with regard to the death penalty. She restates her longstanding moral opposition to capital punishment. Yet, she still voted to affirm the death sentence for the Boston Marathon bomber. Barrett peels back the curtain a bit and explains how she could have issued a Solomonic vote, in which her legal judgment was (quietly) informed by her moral beliefs. Barrett writes that no one would have ever known if she had done this--not even her colleagues. (Does Barrett think that some judges do this?) But Barrett saw such an action as a dereliction of her duty, and violation of her oath. Read these passages carefully:

Soon after my appointment, the Court considered a death sentence imposed on Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the Boston Marathon bombers. The court of appeals had vacated Tsarnaev's sentence, and the United States argued that it had done so in error. I thought that the United States was right, and I joined the Court's holding that Tsarnaev's death sentence was valid.

That was not the only course open to me. Given my view of capital punishment, I could have looked for ways to slant the law in favor of defendants facing the death penalty. There were, after all, plausible arguments going Tsarnaev's way—the court of appeals agreed with him, as did three of my colleagues in dissent. Had I voted in favor of Tsarnaev, no one would have known that I did it because I objected to the death penalty rather than because I concluded that Tsarnaev had the better of the argument.

But that would have been a dereliction of duty. The people who adopted the Constitution didn't share my view of the death penalty, and neither do all my fellow citizens today. Quite the contrary: 27 states authorize capital punishment, as does the federal government.

If I distort the law to make it difficult for them to impose the death penalty, I interfere with the voters' right to self-government. My office doesn't entitle me to align the legal system with my moral or policy views. Swearing to apply the law faithfully means deciding each case based on my best judgment about what the law is, not what it should be.

I found the vote distasteful to cast, and I wish our system worked differently. Yet I had no doubt that voting to affirm the sentence was the right thing for me to do. Had I concluded that casting such a vote was immoral or that I couldn't fairly judge the case, the right thing to do would have been to recuse—not to cheat.

Once again, Barrett's prose brings to mind another one of her colleagues. Who on the Supreme Court is known to "distort" the law to reach "Solomonic" rulings based on a broader sense of "Justice"? Hmmm…..

Let me quote a law professor from 2017, writing about NFIB v. Sebelius:

In NFIB v. Sebelius, the inspiration for Barnett's book, Chief Justice Roberts pushed the Affordable Care Act beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute. He construed the penalty imposed on those without health insurance as a tax, which permitted him to sustain the statute as a valid exercise of the taxing power; had he treated the payment as the statute did—as a penalty—he would have had to invalidate the statute as lying beyond Congress's commerce power.

That law professor, of course, was Amy Coney Barrett, writing a review of Randy Barnett's book. On this front, I agree with Professor Barrett. Here is how I described Chief Justice Roberts's tenure of "faux-Solomonic" rulings:

Roberts's defining rulings are not models of judicial excellence. Instead, they dole benefits to the left and the right in a transparent effort to split the baby. In NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), Robert changed his vote to uphold the Affordable Care Act. But to reach that result, Roberts rewrote a penalty into a tax, and rewrote the mandatory Medicaid expansion into an optional program. And he did so during an apparently successful pressure campaign from legal elites. Few people believe that Roberts offered the best reading on the law based on neutral principles. Rather, the Chief twisted and turned the law to avoid striking down President Obama's signature law, while still preserving some conservative separation of powers principles. More than a decade later, we are stuck not with the healthcare law that Congress adopted, but with the compromise that Chief Justice Roberts brokered.

During the first Trump Administration, Roberts issued a troika of split rulings. First, in Department of Commerce v. New York (2019), Robert ruled that the executive branch had the broad power to inquire about citizenship status on the census. But, Roberts parried, the Trump Administration's reasons for adding the question was "pretextual," and further proceedings were needed to consider the rationale. Professor Noah Feldman of Harvard observed, "Roberts's approach . . . is to try to craft a middle ground that will make the Supreme Court seem less purely political than it would if he opted to join the conservatives."

Second, in Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California (2020), Roberts ruled that the executive branch could in theory terminate the DACA immigration policy. But in this case, the Trump Administration failed to adequately consider how that termination would affect the Dreamers. Again, a victory for the presidency, but a loss for Trump. Joan Biskupic of CNN lauded Roberts's decision as "pragmatic and political."

The third case, June Medical LLC v. Russo (2020), involved abortion. Four years earlier, Roberts dissented in a 5-4 decision that halted abortion restrictions from Texas. But in June Medical, Roberts could have been the fifth vote to pare back Roe v. Wade. Instead, Roberts declared unconstitutional abortion restrictions from Louisiana that were nearly indistinguishable from the Texas abortion restrictions that he had favored. An anonymous conservative writer told Vox, "The only way to make sense of the Supreme Court's abortion jurisprudence is to assume it is guided by one principle: 'Pro-lifers must lose.'"