Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 40

September 9, 2025

[John Elwood] The Troubling Case of Dowd v. United States

I haven't posted on the Volokh Conspiracy in over a decade, because SCOTUSBlog is a better vehicle for my usual posts about Supreme Court minutiae. But one of my cases involves one of the more egregious miscarriages of justice I recall seeing in more than thirty years of practice. Yes, it involves a client of mine, but I try to take a detached view of the strengths and weaknesses of my cases. I've handled a lot of clients over the years, and this is the first case of mine that I'm blogging about.

The case against Andrew DowdAt the center is Dr. Andrew Dowd, a 69-year-old orthopedic surgeon with no criminal history (beyond traffic tickets). He ran a hugely successful practice medical practice, with 10 offices that treated hundreds of patients annually. He was convicted of conspiring to operate on patients who claimed to have slipped and injured themselves at various properties, thereby inflating insurance settlements. The defense maintained that a pre-existing conspiracy—led by a disgraced former chiropractor, another doctor, and lawyers—funneled Dowd patients precisely because his high-volume practice made him unlikely to spot their fraud, and they knew Dowd was likely to operate on the patients based on their medical records and complaints.

The evidence that Dowd knew the patients were fraudulent was thin. The trial witnesses all arrived with MRI reports showing soft-tissue damage, and since the conspirators preferred recruiting people with genuine injuries (just not from where they claimed!), four of the five patients who testified actually had knee damage—and Dowd accurately noted after surgery that the fifth lacked the injury her MRI suggested. The other conspirators chatted openly about the scheme in emails and texts, but none looped in Dowd. When an insurer launched an investigation, the group discussed it, but no one alerted Dowd—implying even they didn't think he was "in on it." Dowd was convicted on a "conscious avoidance" theory: that he deliberately turned a blind eye to signs of fraud.

Dowd recently began serving an 8 ½-year sentence and was ordered to forfeit $8.1 million. While numerous aspects of his case strike me as unjust, three stand out as especially outrageous.

When a judge becomes an advocate: a call for recusalIn an earlier trial, the scheme's mastermind and one of his "runners" (who recruited patients) testified against fellow runners. Dowd was repeatedly named as one of two doctors the group used. The presiding judge didn't just observe; he actively prodded prosecutors to broaden their probe, declaring, "I would urge the government to continue their investigation here, because, based on this testimony, the lawyers and the doctors were heavily involved," and voiced his "hope" that the feds were "pursuing … the corrupt doctors who were involved in this scheme."

Fast-forward: The government indicted Dowd and others, and the case landed randomly with a different judge. But prosecutors filed a "related case" letter, and it got reassigned to the very judge who'd pushed for the expansion. Dowd moved for recusal under 28 U.S.C. § 455(a), arguing that a judge who takes the rare step of lobbying the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York—not exactly a timid outfit—can't reasonably appear impartial when presiding over the resulting trial. While the judge may "not likely have all the zeal of a prosecutor" after calling for the prosecution, "it can certainly not be said that he would have none of that zeal." In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 137 (1955).

Botched "harmless error" reviewNo direct evidence showed Dowd knew about the fraud—just circumstantial bits supporting the "conscious avoidance" claim. To shore it up, prosecutors called Tara Arce, a professional insurance-fraud investigator, as a "lay" (non-expert) witness. Ms. Arce had no first-hand knowledge of the alleged conspiracy. Everything she knew about the case came from reviewing insurance files. Based on those files (much of which were undisputedly hearsay), she opined that there were "red flags" of obvious fraud in the claim files. But only four files involved Dowd, and the "red flags" that Arce identified involved non-medical details a treating physician wouldn't have known about, like the fact that accidents had no witnesses. The trial judge admitted the testimony anyway, even though lay witnesses can only describe what they observed, not draw expert conclusions.

The Second Circuit assumed error—credit where due—but dismissed the error as "harmless" in a superficial review that fixated on the government's "significant proof" elsewhere, without assessing the error's effect over the jury. (Pet. at 24-27.) That flouts Kotteakos v. United States, 328 U.S. 750 (1946), which requires evaluating whether the mistake had a "substantial and injurious effect" on the verdict, not just gauging the prosecution's overall strength. In this razor-thin, inference-heavy case, Arce's improper testimony painted Dowd as ignoring blatant fraud signals—fueling the government's core theory. Worse, the Second Circuit rested its decision on objective record errors, claiming the government "never mentioned [Arce's] testimony in its closing argument." In reality, prosecutors invoked it repeatedly in closing and rebuttal. We flagged that inaccuracy in a rehearing petition, but the court didn't even correct the opinion.

$8 million in restitution without a hearingIn the first trial, the judge set an explicit briefing schedule for restitution. For Dowd, though, the government started the process by emailing the judge in chambers demanding $8.1 million—more than double what earlier defendants paid for the harm caused by the same scheme. No docket filing, no response deadline, no hearing. We didn't even know the email's official status—after all, it wasn't on the public docket, so how could we respond? Local rules grant 14 days to oppose docketed motions. But the judge imposed the full $8.1 million on day 10, without waiting for our filing.

Astonishingly, the Second Circuit ruled no due process violation, claiming Dowd had notice and an opportunity to respond. How? The judge's offhand remark at sentencing that the government had "90 days on restitution" to gather materials. But that vague statement didn't tell the defense they'd lose even the standard 14 days to file a responsive pleading—and besides, the judge actually ruled on day 86 post-sentencing, not day 90. (He'd taken between 96 and 131 days to impose restitution on the other defendants after giving the government the same 90-day period.) We were eager to challenge the prosecution's restitution calculation, given insurer documents stating that some patients weren't "part of [the] pattern."

What's next?We quickly filed our cert petition seeking review of these three issues, supported by a strong amicus brief filed by the Cato Institute. But the government waived its right to respond after waiting long enough to ensure that would be considered at the Court's end-of-summer "Long Conference," where the odds of grants are statistically lowest.

The Court hasn't granted cert in decades without first calling for a response. So unless a Justice demands one, our petition is headed for the "dead list"—the pile of automatic denials.

Over the years, numerous Justices have forced the government to defend judgments in troubling criminal cases by requiring briefs in opposition. Indeed, it was happening so much that in 2023, the Justice Department had to hire more Assistants to the Solicitor General just to write them all.

It would be interesting to see a government response in Dowd's case—particularly on the sufficiency of due process before imposing an $8.1 million judgment on a person without even allowing him the ordinary 14 days to file a response, but also on whether it satisfied the appearance of justice to have a judge who openly "urged" a prosecution to preside over it. The Solicitor General likely would be able to come up with a justification for denying cert, but visible unease with certain rulings could cause him to propose some other resolution (such as a remand to permit Dowd the opportunity to contest restitution).

For now, we wait.

The post The Troubling Case of Dowd v. United States appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Third Circuit Holds Fired "Alt Right" Prof. Jason Jorjani's Speech Was Constitutionally Protected,

[though it remands for a decision on whether he would have been fired in any event based on other misconduct.]

[1.] From Jorjani v. N.J. Inst. of Tech., decided yesterday by Judge Paul Matey, joined by Judges Cheryl Krause and Peter Phipps:

New Jersey Institute of Technology declined to renew a lecturer's contract based on his private comments about race, politics, and immigration. But NJIT's regulation of speech outside the classroom and off the campus is subject to the restraints of the First Amendment, and the school documented no disruption to its educational mission….

NJIT hired Jason Jorjani in 2015 to teach philosophy, and twice renewed his contract in 2016 and 2017. During this time, Jorjani "formed the Alt Right Corporation," to "widen the message of his philosophy, which he describes as an affirmation of the Indo-European Tradition" and "the idea that European cultures are intimately related to those of Greater Iran and the Persianate World, Hindu India and the Buddhist East and are the sources the [sic] world's greatest scientific, artistic and spiritual developments." He spoke at conferences and published an essay titled "Against Perennial Philosophy" on "AltRight.com," a website he helped found. In the essay, he argued that "human racial equality" is a "left-wing myth" and that a great "Promethean" "mentality" rests on a "genetic basis" which "Asians, Arabs, Africans, and other non-Aryan peoples" lack.

The essay also argued that, through "genetic engineering" and eugenic "embryo selection," Iran could produce great philosophers by "restor[ing] the pre-Arab and pre-Mongol genetic character of the majority of the Iranian population within only one or two generations." Jorjani did not discuss these outside associations with his students or colleagues, nor did he disclose them as required by NJIT policy.

Then, in 2017, a person posing as a graduate student contacted Jorjani to discuss "how the Left persecutes and silences Right wing thought in academia." But he was working with a group called "Hope Not Hate," whose goal is to "deconstruct[ ]" individuals it deems "fascist" or "extremist." The two met at a pub where the undercover operative recorded their conversations, at first with Jorjani's consent. But later, apparently assuming the recording had stopped, Jorjani commented on matters concerning race, immigration, and politics.

The meeting became a piece published by the New York Times featuring a video excerpt from Jorjani's remarks at a conference characterizing "liberalism, democracy, and universal human rights" as "ill-conceived and bankrupt sociopolitical ideologies," before cutting to the secretly recorded portion of Jorjani's conversation where he predicts "[w]e will have a Europe, in 2050, where the banknotes have Adolf Hitler, Napoleon Bonaparte, Alexander the Great. And Hitler will be seen like that: like Napoleon, like Alexander, not like some weird monster, who is unique in his own category."

The day after the Times piece was published, NJIT's President emailed all faculty and staff, denouncing Jorjani's statements as "antithetical" to NJIT's "core values." NJIT's Dean of the College of Science and Liberal Arts sent a separate email echoing those sentiments. In the following days, NJIT received some unverified number of calls and, at most, fifty emails expressing concern about Jorjani's recorded comments and his membership on the faculty. Faculty chimed in too, highlighting the content of Jorjani's "Against Perennial Philosophy" essay.

Six days after the New York Times posted the article, NJIT sent a letter to Jorjani placing him on paid leave, explaining the article 1) "caused significant disruption at the university" that NJIT believed would "continue to expand," and 2) revealed "association with organizations" that Jorjani did not disclose on his outside activity form, despite prior direction to fully update the form the preceding Spring. The letter advised Jorjani that NJIT planned to investigate whether he had violated university policies or State ethics requirements.

Fallout continued with NJIT's Department of Biology penning a statement published in the student newspaper asserting "Jorjani's beliefs, as revealed by his remarks, cannot help but produce a discriminatory and intimidating educational environment for [NJIT's] diverse student body." The Faculty Senate followed suit, releasing an "Official Faculty Senate Statement," explaining that "NJIT is a university that embraces diversity and sees that diversity as a source of strength. The NJIT Faculty Senate finds racist pronouncements made by University Lecturer Jason Reza Jorjani to be morally repugnant. Hate and bigotry have no place on the NJIT campus." The Department of History also joined the fray, demanding Jorjani's termination and asserting his "published beliefs create a hostile learning environment for students of color in particular." …

Jorjani was eventually fired, and the District Court "conclude[d] that Jorjani's speech was not protected by the First Amendment because 'Defendants' interest in mitigating the disruption caused by Plaintiff's speech … outweighs Plaintiff's interest in its expression.' Seeing error in that conclusion, we will vacate and remand."

[2.] The Court of Appeals articulated the legal standard for when the government may discipline or fire employees based on their speech (even if it couldn't imprison or fine ordinary citizens for their speech).

"[T]o state a First Amendment retaliation claim, a public employee plaintiff must allege that his activity is protected by the First Amendment, and that the protected activity was a substantial factor in the alleged retaliatory action." If those two requirements are satisfied, the burden shifts and the employer must show "the same action would have been taken even if the speech had not occurred."

A public employee's speech is protected if 1) "the employee spoke as a citizen," 2) his "statement involved a matter of public concern," and 3) "the government employer did not have 'an adequate justification for treating the employee differently from any other member of the general public' as a result of the statement he made." In assessing the third prong, we "balance … the interests of the [employee], as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees." Pickering v. Bd. of Ed. (1968). So "the more substantially an employee's speech involves matters of public concern, the higher the state's burden will then be to justify taking action, and vice versa." …

[3.] This standard leaves considerable room for a version of the "heckler's veto," under which someone's speech may be punished because it causes a hostile reaction by offended listeners.

When the government is administering the criminal law or civil liability, such a "heckler's veto" is generally not allowed: The government generally can't shut down a speaker, for instance, because his listeners are getting offended or even threatening violence because they're offended. But in the employment context, the Pickering balance often allows government to fire employees because their speech sufficiently offend coworkers or members of the public. Perhaps this stems from the judgment that employees are hired to do a particular job cost-effectively for the government, and if their speech so offends others (especially clients or coworkers) that keeping the employees on means more cost for the government than benefit, the government needn't continue to pay them for what has proved to be a bad bargain.

Still, when it comes to public university professors, especially as to their off-the-job speech, courts have often applied the Pickering balance in a way that deliberately offers more speech protection (though perhaps not the same speech protection as ordinary citizens enjoy when it comes to the criminal law). That is what the court did here; to illustrate it, I underline the passages supporting such extra protection, and italicize the passages that seem to leave open room for some sort of heckler's veto:

NJIT's actions do not pass the ordinary Pickering analysis on this record. The parties agree that Jorjani spoke as a private citizen on a matter of public concern. So we consider only whether the distractions NJIT identified as flowing from Jorjani's speech outweigh interest in his discussion. They do not….

Begin with interest in Jorjani's speech, which cannot "be considered in a vacuum" as "the manner, time, and place of the employee's expression are relevant." Jorjani's speech occurred entirely outside NJIT's academic environs. His theories, even if lacking in classical rigor, remain of public import. It matters not that his opinions do not enjoy majoritarian support, since "the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express 'the thought that we hate.'" Matal v. Tam (2017)….

Against that interest, we weigh NJIT's need "as an employer" to promote "the efficiency of the public services it performs." NJIT points only to the "disruption" that followed the publication of Jorjani's remarks consisting of certain students' disapproval of Jorjani's speech, disagreement among faculty, and administrators fielding complaints. We "typically consider whether the speech impairs discipline or employee harmony, has a detrimental impact on close working relationships requiring personal loyalty and confidence, impedes the performance of the speaker's duties, or interferes with the enterprise's regular operations." And we focus mostly on what happened, not what might have been, because although NJIT can act to prevent future harms, and need not "allow events to unfold to the extent that the disruption of the office and the destruction of working relationships is manifest," it must ground predictions in reason, not speculation. The minimal evidence of disruption that NJIT cites differs little from the ordinary operation of a public university and therefore cannot outweigh interest in Jorjani's speech.

First, there is no support for NJIT's contention that student disapproval of Jorjani's speech disrupted the administration of the university. Some students and alumni disagreed with Jorjani's views. But NJIT never identified the exact number of calls or complaints made in person or writing, nor any details about the students' concerns. And although Jorjani said that he perceived a "huge change in attitude toward [him] on the part of [his] students," NJIT points to no objective evidence that students questioned Jorjani's ability to teach, grade, or supervise his classes evenly, beyond one administrator recalling a student dropped Jorjani's class. Entirely absent is any evidence of specific student protests, upheaval, or unwillingness to abide by university policies. But "in the context of the college classroom," students have an "interest in hearing even contrarian views." Meriwether v. Hartop (6th Cir. 2021); see also Blum v. Schlegel (2d Cir. 1994) (explaining that "the efficient provision of services" by a university "actually depends, to a degree, on the dissemination in public fora of controversial speech"). NJIT's theory that student dissent rose to the level of disruption is simply speculative.

Second, the cited disputes among Jorjani and his colleagues are not disruption. NJIT cites the pointed letters denouncing Jorjani published by faculty in the pages of the student newspaper, but that is precisely the sort of reasoned debate that distinguishes speech from distraction. And there is no allegation these editorials, or Jorjani's belief they were defamatory and warranted suit, interfered with the ability of other faculty to fulfill their responsibilities in research, teaching, or shared governance, or otherwise thwarted the university's efforts to educate its students. So although challenges to "employee harmony" might pose disruption when disagreements disturb "close working relationships," that concern is irrelevant inside the university where professors serve the needs of their students, not fellow academics. {Bauer v. Sampson (9th Cir. 2001) ("[G]iven the nature of academic life, especially at the college level, it was not necessary that Bauer and the administration enjoy a close working relationship requiring trust and respect—indeed anyone who has spent time on college campuses knows that the vigorous exchange of ideas and resulting tension between an administration and its faculty is as much a part of college life as homecoming and final exams.").}

That leaves only NJIT's ordinary obligation to field calls and emails, routine administrative tasks that, conceivably, might become so overwhelming in number or nature as to disrupt. But not here. The record reveals that throughout this occurrence there were "[p]ossibly" fifty emails received about Jorjani. Calls were so few that NJIT's witness was "not sure what the number is," and only knew "by reading some emails that so-and-so called the mother, and so-and-so called, former student called, things of that nature." All a most minor uptick in communications, if at all, and one that required no additional staffing to support the single administrator who handled these inquiries.

While NJIT raises an "interest in providing a non-denigrating environment," and appeals to the notion that Jorjani's views could, theoretically, undermine the pedagogical relationship between a teacher and student, it has not pointed to anything in the record that indicates its determination was based on competence or qualifications. In essence, NJIT posits that because Jorjani offered views it disliked, the First Amendment should not apply, and it is entitled to summary judgment. We cannot agree, lest we permit "universities to discipline professors, students, and staff any time their speech might cause offense." {And this case does not implicate a university's "discretionary academic determinations" that entail the "review of [ ] intellectual work product" or "the qualifications of faculty members for promotion and tenure."}

[4.] There's also a factual twist in the case, but the court concludes that this needs to be resolved back in trial court on remand:

As [the controversy about Jorjani took place], NJIT retained a law firm to investigate whether Jorjani had disclosed his outside activities, or engaged in practices "that resulted in a conflict of interest with his responsibilities toward NJIT." The firm's report concluded he did, finding Jorjani: 1) "violated the New Jersey ethics code by failing to disclose that he was a founder, director, and shareholder of the AltRight Corporation"; 2) "violated NJIT faculty policy by cancelling 13 classes in the Spring of 2017," some of which "were not due to illness as he suggested" and resulted in negative student evaluations; 3) erroneously claimed the "video excerpts in the NYT Op-Ed were misleadingly edited to paint [him] in a false light"; and 4) "exhibited a clear pattern of non-responsiveness from the time he started working at NJIT" by neglecting his email inbox….

{The District Court did not … consider whether the speech was a substantial or motivating factor in the alleged retaliation, [or] the same action would have occurred absent Jorjani's speech …. We leave those matters for remand.} …

Frederick C. Kelly, III represents Jorjani.

The post Third Circuit Holds Fired "Alt Right" Prof. Jason Jorjani's Speech Was Constitutionally Protected, appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Free Speech Unmuted: A Conversation with FIRE's Greg Lukianoff

[FIRE is one of the leading free speech advocacy and litigation groups in the country, and Greg is not only its long-time head but also coauthor of several books, including Coddling of the American Mind (with psychologist Jonathan Haidt) and War on Words: 10 Arguments Against Free Speech—And Why They Fail (with law professor and former ACLU President Nadine Strossen).]

Our past episodes:

Free Speech Unmuted: President Trump's Executive Order on Flag DesecrationFree Speech and DoxingThe Supreme Court Rules on Protecting Kids from Sexually Themed Speech OnlineFree Speech, Public School Students, and "There Are Only Two Genders"Can AI Companies Be Sued for What AI Says?Harvard vs. Trump: Free Speech and Government GrantsTrump's War on Big LawCan Non-Citizens Be Deported For Their Speech?Freedom of the Press, with Floyd AbramsFree Speech, Private Power, and Private EmployeesCourt Upholds TikTok Divestiture LawFree Speech in European (and Other) Democracies, with Prof. Jacob MchangamaProtests, Public Pressure Campaigns, Tort Law, and the First AmendmentMisinformation: Past, Present, and FutureI Know It When I See It: Free Speech and Obscenity LawsSpeech and ViolenceEmergency Podcast: The Supreme Court's Social Media CasesInternet Policy and Free Speech: A Conversation with Rep. Ro KhannaFree Speech, TikTok (and Bills of Attainder!), with Prof. Alan RozenshteinThe 1st Amendment on Campus with Berkeley Law Dean Erwin ChemerinskyFree Speech On CampusAI and Free SpeechFree Speech, Government Persuasion, and Government CoercionDeplatformed: The Supreme Court Hears Social Media Oral ArgumentsBook Bans – or Are They?

The post Free Speech Unmuted: A Conversation with FIRE's Greg Lukianoff appeared first on Reason.com.

September 8, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Justice Kavanaugh Continues To Be The Only Justice To Explain Emergency Docket Orders

[And Justice Kavanaugh has come a long way since using the term "noncitizen" instead of "illegal alien."]

On Monday, the Supreme Court granted a stay in . The vote was (likely) 6-3. Justice Kavanaugh wrote a ten-page concurrence. Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson, wrote a twenty-page dissent.

This case was first filed on August 7, and briefing was completed on August 13. The Justices in the majority had about a month to put together a majority opinion. They didn't. Why? Perhaps the majority could not come to a consensus on a single line of reasoning--whether on Article III standing or the Fourth Amendment. Perhaps the majority simply didn't feel the need to write a majority opinion, because this is only an interim order. Or maybe a book tour got in the way of writing something. Well, it's hard to read the opinion when there isn't an opinion to read.

I don't have any particular expertise on the interaction between Article III standing and police stops, or on the Fourth Amendment issue. But I will commend Justice Kavanaugh, once again, for explaining his thinking. I don't know if Kavanaugh's views command a majority of the Court, but it is difficult to think of any other basis on which a stay could have been granted. We've seen some lower courts favorably cite dissents on the emergency docket. I think the judges in California would be prudent to cite Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence over Justice Sotomayor's dissent.

Justice Kavanaugh writes that the two "most critical" factors when deciding to grant a stay are certworthiness and irreparable arm

To obtain a stay from this Court, the moving party must demonstrate a fair prospect that, if the District Court's decision were affirmed on appeal, this Court would grant certiorari and reverse. The moving party also must show a likelihood that it would suffer irreparable harm if a stay were not granted. Those two factors are the "most critical." Nken v. Holder, 556 U. S. 418, 434 (2009).

I didn't remember Nken calling those two factors the "most critical." And it didn't. Rather, Nken found that the two "most critical" actors were likelihood of success on the merits and irreparable harm. Cert-worthiness was not discussed at all in Nken. But this factor was discussed in Hollingsworth v. Perry, which Justice Barrett amplified in Does v. Mills. Justice Kavanaugh is tweaking the standard here. He very well might be right about what are the two most factors in his view, but I don't think that comes from Nken.

I continue to think cert-worthiness is not a useful factor. Each Justice has a different threshold for whether a case is cert-worthy. Justice Kavanaugh, to his credit, signals that he wants to grant more cases. Same for Justices Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch. Justice Barrett is the most stingy justice with cert-grants. We should not pretend cert-worthiness adds much to the equation, beyond a Justice's subjective valuation of how important a case is.

Because Justice Kavanaugh thinks that the case is cert-worthy, and the government will suffer irreparable harm in the absence of a stay, he turns to balancing the harms and equities. But Justice Kavanaugh immediately pivots, and explains that balancing the harms and equities is really tough in a case like this:

Turning then to the balance of harms and equities: Aswith many other applications for interim relief to this Court, the harms and equities may appear weighty on both sides. . . . Moreover, in a case like this involving government action, balancing the harms and equities can become especially difficult and policy-laden.

Why is this task so tough? Because of the "harms to the third parties who otherwise would benefit from the challenged government action." Justice Kavanaugh does not spell out this point clearly. But if I am reading between the lines, the third parties would be Americans who benefit from the deportation of illegal aliens. I'll return to Justice Kavanaugh's discussion of illegal immigration below.

Footnote 3 revisits Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence in NetChoice v. Fitch. That opinion left me a bit confused about how to conceptualize the relationship between balancing the equities and likelihood of success on the merits. Footnote 3 offers a way to reconcile those prongs.

In Fitch, Kavanaugh explains, there was a state law, and enjoining it for the interim status would not have caused much harm to the porn companies. But when there is a "significant new law," there are harms on both sides of the ledger.

There can be situations where, based on the record before this Court, it appears that a temporary injunction or stay would not impose much if any harm on the non-prevailing party in the interim period before a final judgment. See, e.g., NetChoice, LLC v. Fitch, 606 U. S. ___, ___ (2025) (KAVANAUGH, J., concurring in denial of application to vacate stay) (slipop., at 2); Response in Opposition in NetChoice, LLC v. Fitch, No. 25A97, pp. 38–39. But especially in cases involving a significant new law or government action, the interim harms and equities are typically weighty on both sides.

Justice Kavanaugh then turns to Labrador v. Poe. In candor, the state law at issue in Labrador and the state law at issue in Fitch both seem "significant" and "new." I'm not sure why the likelihood of success on the merits was not enough to deny the stay in Fitch. But in any event, Kavanaugh explains that the court should turn to the likelihood prong for these sorts of "significant" laws.

In those situations, as I have explained before, resolving the application therefore often will depend on this Court's assessment of likelihood of success on the merits. See Labrador v. Poe, 601 U. S. ___, ___–___ (2024) (KAVANAUGH, J., concurring in grant of stay) (slip op., at 3–4) (when applicant has demonstrated irreparable harm and when the harms and equities are weighty on both sides, "this Court has little choice but to decide the emergency application by assessing likelihood of success on the merits"); Trump v. CASA, Inc., 606 U. S. ___, ___ (2025) (KAVANAUGH, J., concurring) (slip op., at 10) ("[I]n deciding applications for interim relief involving major new statutes or executive actions, we often have no choice but to make a preliminary assessment of likelihood of success on the merits; after all, in cases of that sort, the other relevant factors (irreparable harm and the equities) are often very weighty on both sides").

I think the order of operations can be stated plainly. The most important two factors at the outset are whether the case is cert-worthy and whether the moving party would suffer irreparable harm in the absence of a stay. Next, the Court will balance the harms and equities. But if that balancing test is difficult, especially in a "significant" case, the court should consider which side is likely to prevail on the merits. Does that sound right?

Finally, I have to point out the nomenclature.

In June 2020, Justice Kavanaugh made headlines by using the term "noncitizen" instead of alien. He wrote in Barton v. Barr:

This opinion uses the term "noncitizen" as equivalent to the statutoryterm "alien." See 8 U. S. C. §1101(a)(3).

As best as I can tell, Justice Kavanaugh has continuously used the neologism "noncitizen," even as Justices Thomas and Alito continue to use the correct statutory term, "alien." Or at least Justice Kavanaugh did so before Noem v. Perdomo.

Justice Kavanaugh repeatedly refers to illegal immigrants and illegal immigration. The word "noncitizen" is used only once in passing. Consider this passage:

The Government estimates that at least 15 million peopleare in the United States illegally. Many millions illegally entered (or illegally overstayed) just in the last few years. Illegal immigration is especially pronounced in the LosAngeles area, among other locales in the United States. About 10 percent of the people in the Los Angeles region are illegally in the United States—meaning about 2 million illegal immigrants out of a total population of 20 million.

Indeed, Justice Kavanaugh goes further and acknowledges problems caused by illegal immigration:

So it is in this case, particularly given the millions of individuals illegally in the United States, the myriad"significant economic and social problems" caused by illegal immigration, Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U. S., at 878, and the Government's efforts to prioritize stricter enforcement of the immigration laws enacted by Congress.

And as noted above, Kavanaugh alludes to harms to third parties when illegal aliens are not deported:

That is because a court must balance the harms to the regulated and negatively affected parties not only against the harms to the Government as an institution, but also against the harms to the third parties who otherwise would benefit from the challenged government action.

Is Justice Kavanaugh alluding to illegal aliens who may commit crimes if not deported?

Justice Kavanaugh does acknowledge the reasons why people illegally migrate to the United States. He also recognizes that different administrations have different enforcement priorities--leading to some whiplash.

To be sure, I recognize and fully appreciate that many (not all, but many) illegal immigrants come to the UnitedStates to escape poverty and the lack of freedom and opportunities in their home countries, and to make better lives for themselves and their families. And I understand that they may feel somewhat misled by the varying U. S.approaches to immigration enforcement over the last few decades. But the fact remains that, under the laws passed by Congress and the President, they are acting illegally by remaining in the United States—at least unless Congress and the President choose some other legislative approach to legalize some or all of those individuals now illegally present in the country. And by illegally immigrating into and remaining in the country, they are not only violating the immigration laws, but also jumping in front of those noncitizens who follow the rules and wait in line to immigrate into the United States through the legal immigration process.

But ultimately, none of this matters, as illegal aliens "jumped" in front of the line. (Reminds me of my experience while waiting for the DACA oral argument.)

I think we are seeing based Brett--and I like it.

The post Justice Kavanaugh Continues To Be The Only Justice To Explain Emergency Docket Orders appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Farewell to the TaxProfBlog

[Blogging can be a thankless and burdensome task. We should all be grateful for Dean Paul Caron's many year or service.]

In 2011, while clerking on the Sixth Circuit, I entered the academic job market. At the time, I checked Paul Caron's TaxProfBlog regularly. Paul compiled information about VAPs, fellowships, and other aspects of academia. I reached out to Paul, and asked if he would meet. He graciously agreed!

I'll never forget the meeting. We caught up at a Starbucks near the campus of the University of Cincinnati. Who walks in, but the former mayor of Cincy: Jerry Springer. Yes, that Jerry Springer. Paul offered some invaluable advice about the academic market and how to approach the meat market. And Jerry offered some useful advice of how to handle conflicts at faculty meetings. (Okay, I made up the last point, but it would be hilarious to see Jerry manage a hiring meeting.)

Since then, I have been fortunate to keep Paul in my circle of contacts. I still read his blog daily, and often will email him about certain items he may wish to cover. Paul's output is staggering. He has published more than 55,000 posts, on top of his full-time job as a Dean! Paul also answers emails at all hours of the day, a remarkable feat. He doesn't miss a thing.

Alas, all good things come to an end. In 2023, I offered a requiem for SCOTUSBlog, which seemed destined to drift away, though thanks to a bizarre turn of events, it is not being bolstered by The Dispatch. But now, a pillar of the legal blogosphere will draw to a close. TypePad, the once-popular blogging software, is shutting down at the end of September. Paul has announced that he is shutting down TaxProfBlog. I will preserve his final post since the current page will soon vanish:

TaxProf Blog has been a labor of love these past 21 years. I have been puzzling over when would be the right time to stop. Typepad, the platform on which TaxProf Blog is hosted, made the decision for me when it announced on August 27th that it will discontinue all blogs effective September 30th. At this stage in my life, I am not interested in starting anew on a different platform. I hope to find another home for the massive content of my 55,780 TaxProf Blog posts. If I do, I will post the link on this post before September 30th and notify the subscribers to my tax and legal education email lists.

I am proud of the role TaxProf Blog has played in the tax and legal education communities over the past 21 years. My boyhood dream was to be a sports reporter covering the Boston Red Sox on a daily basis for The Boston Globe (after it became obvious even to me that my dream of playing first base for the Red Sox would not pan out). My wife Courtney early on said the blog scratched that itch for me in academics rather than sports.

Before TaxProf Blog sunsets on September 30th, I would greatly appreciate it if readers who have enjoyed my tax, legal education, and/or faith coverage through the years would drop a short note in the comment section at the bottom of this post. When I eventually retire, I will cherish the memories of the time I spent writing this blog for over two decades in the hope that it enriched your lives just a little bit.

Other legal blogs may also shut down, including the valuable Mirror of Justice. What a loss.

Blogging can be a thankless and burdensome task. We don't earn any actual income for doing it, and receive countless attacks from people who may never write any publicly. Indeed, social media for better or worse, has supplanted much of what made the legal blogosphere so important. I started blogging in the Fall of 2009, and still enjoy the process. But I do not write nearly as much as I used to, and I see diminishing returns.

We should all be grateful for Dean Paul Caron's many year or service. No one will replace him.

The post Farewell to the TaxProfBlog appeared first on Reason.com.

[Orin S. Kerr] Supreme Court Lifts Injunction in Los Angeles Immigration Enforcement Case

[Allowing the Administration's program to continue, although not creating any new Fourth Amendment law.]

The Supreme Court entered an order today staying an order by a Los Angeles district court that had imposed a broad injunction in how the Trump Administration can enforce the immigration laws. The Supreme Court's order itself has no reasoning, but Justice Kavanaugh wrote a concurrence in the judgment explaining his vote in support of the Court's order and Justice Sotomayor (joined by Justice Kagan and Justice Jackson) wrote a dissent explaining their votes against the Court's order.

Given that the underlying merits involve my area, the Fourth Amendment, I thought I would offer some tentative thoughts.

By way of context, the usual practice is that courts rarely enter injunctions in Fourth Amendment cases. Fourth Amendment law is just too fact-specific. What the police can and can't do is so dependent on the facts that it's hard for courts to carve out ahead of time a class of things the Fourth Amendment will not allow. This creates a problem for courts wanting to impose broad injunctive relief to prevent Fourth Amendment violations. It forces courts to either say something generic like "don't violate the Fourth Amendment" —something the Fourth Amendment already covers—or to try to come up with prophylactic rules to protect the underlying Fourth Amendment values even if it means enjoining some constitutional acts to prevent other unconstitutional ones.

The Supreme Court has in the past interpreted limits on Article III to basically block these options. The key case is City of Los Angeles v. Lyons (1983). To get an injunction, a plaintiff has to show that the specific unconstitutional practice to be enjoined has happened to him before and will likely happen to him again. When that happens, the injunction will be specific and not prophylactic; it will specify a clearly unconstitutional practice. But that's a high bar, as it requires a situation in which a plaintiff who had his Fourth Amendment rights violated in a specific way before to have good reason to think his rights will be violated in that same specific way in the future. It means that injunctive relief in Fourth Amendment cases is uncommon. For more, see my short article The Limits of Fourth Amendment Injunctions (2009).

Now on to this case. The trial court imposed a broad injunction about what kinds of immigration stops are permitted. The key language was this:

a. As required by the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution, Defendants shall be enjoined from conducting detentive stops in this District unless the agent or officer has reasonable suspicion that the person to be stopped is within the United States in violation of U.S. immigration law.

b. In connection with paragraph (1), Defendants may not rely solely on the factors below, alone or in combination, to form reasonable suspicion for a detentive stop, except as permitted by law:

i. Apparent race or ethnicity;

ii. Speaking Spanish or speaking English with an accent;

iii. Presence at a particular location (e.g. bus stop, car wash, tow yard, day laborer pick up site, agricultural site, etc.); or

iv. The type of work one does.

The first part of this, (a), is just more or less summarizing Fourth Amendment law. It's (b) that is the more important part. Exactly what this language means isn't entirely clear, but it has a prophylactic quality. As I read it, at least, it seems to enjoin some constitutional action to prevent other unconstitutional action that is otherwise hard to stop. Put another way, the injunction approaches the Trump Administration's enforcement program at a programmatic level. It seeks to reform it at a programmatic level. That was justified under Lyons, the district court's reasoning seemed to go, because the plaintiffs were groups instead of individuals. In effect, the unknown but presumably large membership of the plaintiff groups created a way around the requirement that the particular plaintiff show a specific practice had happened before that would happen to him again.

When the district court's order came down, I was dubious about the legal basis of it. It seemed too easy a way around the limits of Fourth Amendment injunctions, allowing just the kind of programmatic reform efforts by injunctions that Lyons had stopped. Given all of this, I wasn't surprised that the Supreme Court stayed the order today.

Because the Supreme Court's order doesn't have any reasoning, it doesn't tell us why a majority of the Court ruled as it did. No new law is created. But we do have some dueling opinions which might be of interest. Here's an overview and some thoughts, focusing on the Fourth Amendment-related issues. (I'll skip over the non-Fourth Amendment parts, as they are not in my area of expertise. I'm sure others are writing on those.)

The only view we have in support of the order is Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence in the judgment. Justice Kavanaugh's opinion begins with what I would have thought was the traditional way to look at these things: You can't have this kind of broad injunction under Lyons.

Plaintiffs' standing theory largely tracks the theory rejected in Lyons. Like in Lyons, plaintiffs here allege that they were the subjects of unlawful law enforcement actions in the past—namely, being stopped for immigration questioning allegedly without reasonable suspicion of unlawful presence. And like in Lyons, plaintiffs seek a forward-looking injunction to enjoin law enforcement from stopping them without reasonable suspicion in the future. But like in Lyons, plaintiffs have no good basis to believe that law enforcement will unlawfully stop them in the future based on the prohibited factors—and certainly no good basis for believing that any stop of the plaintiffs is imminent. Therefore, they lack Article III standing: "Absent a sufficient likelihood" that the plaintiffs "will again be wronged in a similar way," they are "no more entitled to an injunction than any other citizen of Los Angeles; and a federal court may not entertain a claim by any or all citizens who no more than assert that certain practices of law enforcement officers are unconstitutional." Lyons, 461 U. S., at 111; see Clapper v. Amnesty Int'l USA, 568 U. S. 398 (2013); Application 16–22; Reply 4–9.2

That seems right. It's what I take to be the standard view of the law from Lyons.

Next, Justice Kavanaugh argues that even if the plaintiffs have standing to bring the case, the government has a fair prospect of success on the merits under the Fourth Amendment:

To stop an individual for brief questioning about immigration status, the Government must have reasonable suspicion that the individual is illegally present in the United States. See Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U. S., at 880–882; Arvizu, 534 U. S., at 273; United States v. Sokolow, 490 U. S. 1, 7 (1989). Reasonable suspicion is a lesser requirement than probable cause and "considerably short" of the preponderance of the evidence standard. Arvizu, 534 U. S., at 274. Whether an officer has reasonable suspicion depends on the totality of the circumstances. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U. S., at 885, n. 10; Arvizu, 534 U. S., at 273. Here, those circumstances include: that there is an extremely high number and percentage of illegal immigrants in the Los Angeles area; that those individuals tend to gather in certain locations to seek daily work; that those individuals often work in certain kinds of jobs, such as day labor, landscaping, agriculture, and construction, that do not require paperwork and are therefore especially attractive to illegal immigrants; and that many of those illegally in the Los Angeles area come from Mexico or Central America and do not speak much English. Cf. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U. S., at 884–885 (listing "[a]ny number of factors" that contribute to reasonable suspicion of illegal presence). To be clear, apparent ethnicity alone cannot furnish reasonable suspicion; under this Court's case law regarding immigration stops, however, it can be a"relevant factor" when considered along with other salient factors. Id., at 887.

Under this Court's precedents, not to mention common sense, those circumstances taken together can constitute at least reasonable suspicion of illegal presence in the United States. Importantly, reasonable suspicion means only that immigration officers may briefly stop the individual and inquire about immigration status. If the person is a U. S. citizen or otherwise lawfully in the United States, that individual will be free to go after the brief encounter. Only if the person is illegally in the United States may the stop lead to further immigration proceedings.

In short, given this Court's precedents, the Government has demonstrated a fair prospect of success both on standing and Fourth Amendment grounds. To conclude otherwise, this Court would likely have to overrule or significantly narrow two separate lines of precedents: the Lyons line of cases with respect to standing and the Brignoni-Ponce line of cases with respect to immigration stops based on reasonable suspicion. In this interim posture, plaintiffs have not made a persuasive argument for this Court to overrule or narrow either line of precedent, much less both of them.

I am not so sure what to make of this. It's trying to answer a vague hypothetical: If there were actual facts, would those actual facts reveal a Fourth Amendment violation? I think the answer is, well, it just depends on what the facts turn out to be.

This goes back to the prophylactic point I made above. If we imagine 100 stops that were prevented by the injunction, some number X would satisfy the Fourth Amendment and some number 100-X would not. We don't know what X is. Maybe it's 50, or maybe it's 90, or maybe it's 10. Or something else. Who knows. But there are no specific facts yet, which makes it impossible to apply the Fourth Amendment at this point.

I think Kavanaugh is on solid ground in thinking that X is not zero. That is, some of the stops would be constitutional. And for that matter, some of the interactions would not be deemed stops at all. But I'm not sure how that should translate in terms of the likelihood of success on the merits under the doctrine, though. Are we talking about the government's likelihood of success in one of the X cases where the Fourth Amendment was satisfied (very high), or the likelihood of success in one of the 100-X cases where the Fourth Amendment was violated (very low)? Maybe, in a case involving some unknown but large number of stops, you just take the whole imagined set and average them to get some predicted typical likelihood of success (high enough to satisfy that prong of the test, apparently)? The question is an odd one.

Justice Sotomayor's dissent offers a starkly different picture. Justice Sotomayor accepts the programmatic framing of the district court. That is, instead of looking at individual stops, she would look broadly at the program of stops that the Trump Administration enacted, called "Operation At Large." This is my characterization, not hers, but I think it's fair to say that this means you treat the facts as an imagined stop that the Administration is planning, in which (as she puts it) "all Latinos, U. S. citizens or not, who work low wage jobs are fair game to be seized at any time, taken away from work, and held until they provide proof of their legal status to the agents' satisfaction." With that as as the assumed set of facts, Justice Sotomayor says that those facts violate the Fourth Amendment:

The Fourth Amendment thus prohibits exactly what the Government is attempting to do here: seize individuals based solely on a set of facts that "describe[s] a very large category of presumably innocent" people. Reid, 448 U. S., at 441. As the District Court correctly held, the four factors—apparent race or ethnicity, speaking Spanish or English with an accent, location, and type of work—are "no more indicative of illegal presence in the country than of legal presence." App. 105a. The factors also in no way reflect the kind of individualized inquiry the Fourth Amendment demands. See, e.g., Terry, 392 U. S., at 21, n. 18 ("This demand for specificity . . . is the central teaching of this Court's Fourth Amendment jurisprudence"); United States v. Arvizu, 534 U. S. 266, 277 (2002) (relying on particularized facts about the vehicle and its passengers to justify stop based on reasonable suspicion). Allowing the seizure of any Latino speaking Spanish at a car wash in Los Angeles tramples the constitutional requirement that officers "must have a particularized and objective basis for suspecting the particular person stopped of criminal activity." United States v. Cortez, 449 U. S. 411, 417–418 (1981).

What about the problem of X? That is, that some X number of stops will be constitutional, and therefore presumably shouldn't be enjoined? Justice Sotomayor is dismissive of these concerns. Looking at the enforcement action as a program, she says the government has not put forward evidence that stops under the program are X cases. Thus, the X stops can be considered outside this case and are not relevant:

In any event, Operation At Large bears little resemblance to the Government's hypothetical. The Government has provided no evidence showing that its seizures were based on credible intelligence about a particular employer at a particular location. Indeed, the Government submitted no evidence about what facts its agents relied upon to conduct most of the seizures documented in the record. Rather, its declarations suggest that the Government generally targeted locations based on the "types of businesses" that, in the agents' generalized experiences, undocumented immigrants supposedly frequent. ECF Doc. 71–2, at 2 (emphasis added). That is plainly insufficient to give rise to a "particularized and objective basis for suspecting [a] particular person" under the Fourth Amendment. Cortez, 449 U. S., at 417–418.

What to make of this?

It seems to me that Justice Kavanaugh's opinion and Justice Sotomayor's dissent both have a hard time grappling with the X problem, and they both end up addressing it through framing. There are a lot of stops here, and some will comply with the Fourth Amendment (X) and others won't (100-X). Justice Kavanaugh says, in effect, there's enough X here so that we can take X as important we can't have a broad injunction. Justice Sotomayor says, in effect, let's focus on the 100-X cases so we can exclude the X cases from consideration and we need the broad injunction.

To my mind, all of this points to the underlying problem with Fourth Amendment injunctions that I wrote about in my 2009 article. It's hard to enter orders addressing a large but unknown set of scenarios in which some of the scenarios will be constitutional and some won't. You end up either just saying to not violate the Fourth Amendment, or you end up with the impossible task of trying to say in advance which specific facts will violate the Fourth Amendment, or you end up entering an overly broad prophylactic order enjoining a broad class of conduct to get to the cases that are unconstitutional within it. Given how fact-specific Fourth Amendment law is, it's just a hard way to rule on Fourth Amendment issues. So I tend to think reliance on Lyons is correct here, and that this should get in the way of saying much if anything about the Fourth Amendment merits.

Anyway, all of this means a lot more practically than legally. Legally, this doesn't change the law, as far as I can tell. It's an order with no reasoning, and Kavanaugh's opinion can be read in different ways but I wouldn't think of it as changing the law (at least on Fourth-Amendment-related issues). What matters here is the practical reality that the Trump Administration's enforcement program can continue. That's a very big deal on the ground.

Anyway, those are my tentative thoughts.

The post Supreme Court Lifts Injunction in Los Angeles Immigration Enforcement Case appeared first on Reason.com.

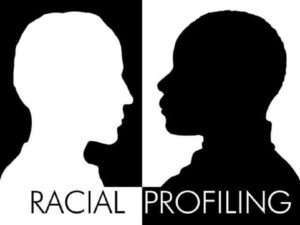

[Ilya Somin] Supreme Court Issues Dubious "Shadow Docket" Ruling Staying Injunction Against Racial Profiling in Immigration Enforcement

[There is no majority opinion, so the reasoning is unclear. But Justice Kavanaugh's concurring opinion undercuts principle that government must abjure racial discrimination.]

NA

NA Today, the Supreme Court issued a "shadow docket" ruling staying a district court decision that had enjoined ICE from engaging in racial and ethnic profiling in immigration enforcement in Los Angeles. The decision was apparently joined by the six conservative justices; the three liberals dissented. As is often the case with "emergency"/shadow docket rulings, there is no majority opinion. Thus, we cannot know for sure what the majority justices' reasoning was. We have only a concurring opinion by Justice Brett Kavanaugh. But that opinion has deeply problematic elements. Most importantly, it is fundamentally at odds with the principle that government must be "color-blind" and abjure racial discrimination.

The district court found extensive use of racial profiling by ICE in immigration enforcement in the LA area, and issued an injunction barring it. Justice Kavanaugh, however, contends that the profiling is not so bad, and does not necessarily violate the Fourth Amendment because, while "apparent ethnicity alone cannot furnish reasonable suspicion," it could count as a "relevant factor when considered along with other salient factors."

But even if it is not the sole factor, its use still qualifies as racial or ethnic discrimination. And, at least in some cases, it will be a decisive factor, in the sense that some people will be detained based on their apparent ethnicity, who otherwise would not have been. Imagine if the use of race and ethnicity were permitted in other contexts, so long as it is not the "sole" factor. Government could engage in racial discrimination in hiring (so long, again, as other factors were permitted), voting rights, access to education, and more.

Moreover, in this case, race and ethnicity clearly were major factors in ICE decision-making, not just peripheral ones. That is evident from the fact that ICE arrests in Los Angeles County declined by 66 percent after the district court issued the injunction the Supreme Court stayed today.

In SFFA v. Harvard the Supreme Court's 2022 ruling against racial preferences in university admissions, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that "eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it." If this is a sound constitutional principle - and it is - there cannot be an ad hoc exception for immigration enforcement, or for law enforcement generally. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor emphasizes in her dissent, joined by all three liberal justices, "We should not have to live in a country where the Government can seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low wage job." Or at least that's true if the Constitution genuinely requires government to abjure racial and ethnic discrimination.

Today's case is under the Fourth Amendment, while SFFA v. Harvard was decided under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth. But it makes no sense to conclude that racial and ethnic discrimination is generally unconstitutional, yet also that its use is "reasonable" under the Fourth Amendment.

In assessing the desirability of staying the injunction Justice Kavanaugh also argues that illegal migrants have little or not legitimate interest in avoiding immigration detention, while citizens and legal residents are only slightly inconvenienced because "reasonable suspicion means only that immigration officers may briefly stop the individual and inquire about immigration status. If the person is a U.S. citizen or otherwise lawfully in the United States, that individual will be free to go after the brief encounter." This ignores the reality that ICE has detained and otherwise abused numerous US citizens and legal residents for long periods of time. As the district court ruling and Justice Sotomayor's dissent describe, there are plenty of examples of this problem in the record of this very case. Moreover, even actual illegal migrants have a constitutional right to be free of racial discrimination. The relevant constitutional provisions aren't limited to citizens or to legal residents.

Justice Kavanaugh also argues that the plaintiffs in this case - including people victimized by earlier incidents of ICE profiling - lacked standing to seek an injunction against future racial profiling because they cannot prove that the profiling will recur. He cites City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, a 1983 Supreme Court decision in which a victim of a police chokehold was denied standing to seek an injunction against future such incidents. But, as Sotomayor notes, ICE has a systematic policy of racial and ethnic profiling that it seeks to continue on a large scale, at least in the LA area at issue in this case. That makes the situation fundamentally different from Lyons, where the court found there was no evidence that LA police had a systematic policy of using illegal chokeholds.

There are some other issues covered by Kavanaugh and Sotomayor, which I will not attempt to go over here. But the above points suffice to show how problematic Kavanaugh's position is.

In fairness, while Kavanaugh and possibly other conservative justices (depending on why they voted to impose the stay) are inconsistent on issues of racial discrimination, the same is true of the liberals. The arguments Kavanaugh uses to excuse racial profiling by law enforcement here are similar to those many left-liberals routinely use to justify affirmative action racial preferences in employment and university admissions. Just as Kavanaugh argues that race is just one of several factors used by ICE to decide who to detain, so defenders of affirmative action argue that race is just one of several factors in a "wholistic" process.

Kavanaugh also suggests that the use of race and ethnicity here may be understandable, given the large population of illegal migrants in the LA area, and the correlation (even if imperfect) between illegal status and the appearance of Hispanic ethnicity. As Kavanaugh notes, people who "come from Mexico or Central America and do not speak much English" are disproportionately likely to be illegal migrants. As I have been saying for many years, this kind of argument is very similar to standard rationales for affirmative action, which hold that there is a large population of ethnic minorities (particularly Blacks and Hispanics) who are disproportionately likely to be victims of past discrimination or to contribute to "diversity" in higher education. These correlations, it is said, justify the use of racial preferences, even if they are often inaccurate in a given case.

Conservatives and others who rightly reject this kind of rationale for affirmative action preferences should not accept the same flawed reasoning in the law enforcement context. Either it is acceptable for government to use race and ethnicity as a crude proxy for other characteristics, or it is not. If we truly believe in color-blind government, we cannot make an exception for for those government agents who carry badges and guns have the power to arrest and detain people.

Nor can the exception be cabined to immigration enforcement. If preventing illegal migration is sufficient reason to authorize racial discrimination (so long as it isn't the only "sole" factor), why not preventing murder, rape, assault, or any number of other, more serious violations of the law? For that matter, why not pursuing racial justice - the traditional rationale for affirmative action (before it was displaced by the "diversity" theory, thanks to Supreme Court rulings blessing the latter)?

Today, the Supreme Court took a step in a badly wrong direction. But, since this is a shadow docket ruling issued without an majority opinion, it creates little, if any, binding precedent. Perhaps some of the five majority justices who didn't join Kavanaugh have different and narrower grounds for their stance. Hopefully, a majority will reach a different conclusion when and if they take up this kind of issue more systematically. We shall see.

The post Supreme Court Issues Dubious "Shadow Docket" Ruling Staying Injunction Against Racial Profiling in Immigration Enforcement appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] My New Boston Globe Article Making Case for Abolishing ICE and Giving the Money to State and Local Police

[It builds on an earlier piece in The Hill]

NA

NA On August 27, I published an article in The Hill, advocating abolishing ICE and giving the money to state and local police. The Boston Globe asked me to adapt the earlier piece into an article for them. That new article was published earlier today. Here is an excerpt:

The Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency has a history of horrific abuses, which have gotten worse under the second Trump administration. They include violations of civil liberties, large-scale racial profiling, and terrible conditions for detainees. Those abuses are of special interest to the Boston area, given the region's large immigrant population and that the administration is apparently planning a surge in ICE activity in Boston.

ICE's cruel actions have made the agency highly unpopular, with recent polls showing large majorities disapprove of it. But most Democrats, including most Massachusetts leaders, still shy away from calling for its abolition, likely for fear of being seen as "soft on crime" or against law enforcement. But there is a way out of this dilemma: Advocate for abolishing ICE and giving the money to state and local police.

In the new article, I took the opportunity to address some objections left-liberals (like, perhaps, many Globe readers) might have, such as this one:

Many studies show that putting more police on the streets can reduce crime. Indeed, diverting law enforcement resources from deportation to ordinary policing can help focus more effort on the violent and property crimes that most harm residents of high-crime areas. Deportation efforts, by contrast, target a population with a lower crime rate than others…..

Some progressives might nonetheless oppose transferring funds to conventional police. The latter, too, sometimes engage in abusive practices, including racial profiling. I share some of these concerns and am a longtime advocate of increased efforts to combat racial profiling. But comparative assessment is vital here. Despite flaws, conventional police are much better in these respects than ICE, with its ingrained culture of brutality and massive profiling. They have stronger incentives to maintain good relations with local communities and don't need to rely on racial profiling nearly as much to find suspects. A shift of law enforcement funds from ICE to conventional police would mean a major overall reduction in racial profiling and other abuses.

Survey data show most Black people (the biggest victims of profiling) actually want to maintain or increase police presence in their neighborhoods, even as they (understandably) abhor racial profiling. Grant money transferred from ICE could potentially be conditioned on stronger efforts to curb racial profiling and related abuses, thereby further reducing the problem. It should also be conditioned on spending it on combatting violent and property crime, and structured in a way that prevents excessive dependence on federal funding.

The post My New Boston Globe Article Making Case for Abolishing ICE and Giving the Money to State and Local Police appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Past Copyright Settlement Agreements Needn't Be Sealed When Directly Related to Merits of Current Claim

From Judge Thomas Rice (E.D. Wash.) Aug. 29 in Prepared Food Photos, Inc. v. Pool World, Inc., a copyright case in which the question is whether defendant has to redact certain materials from its summary judgment papers:

Defendant's motion for summary judgment rests on a statute of limitations defense, specifically that the discovery rule [under which the statute of limitations sometimes runs from when defendant discovered the infringement, rather than from when the infringement began -EV] is unavailable to Plaintiff as a matter of law in part due to Plaintiff's pattern of inequitable conduct toward Defendant and past accused infringers. The information Defendant seeks to [file not under seal] pertains to prior subscription fees and infringement settlement payments previously received by Plaintiffs. This information directly relates to the merits of Defendant's dispositive motion, and the "compelling reasons" standard [for determining whether the information should be sealed -EV] is appropriate….

Plaintiff asserts that settlement agreements entered into by Plaintiff and any infringer are subject to confidentiality clauses requiring the contracting terms be kept confidential. Therefore, unsealing documents that identify the infringer subject to the settlement agreement and the amount of the settlement paymhent would constitute a breach by Plaintiff for every respective settlement agreement. Plaintiff argues confidentiality of these terms is needed to protect both the infringer from revealing that it utilized copyrighted material and settled for a specified amount, thus inviting other copyright holders to pursue litigation against it, and Plaintiff from having prior settlements leveraged against it in future infringement claims.

The Court does not find compelling reasons exist to seal the payment terms of the settlement agreements but the payors identifying information may [be] redacted. While the Ninth Circuit has found private confidentiality agreements to satisfy the "good cause" standard for sealing non-dispositive motions and supporting documents, without more, they do not constitute a compelling reason to seal the information…. "That [the parties] agreed among themselves to keep the settlement details private, without more, is no reason to shield the information from … the public at large." ….

Plaintiff's concern of breach is likewise not supported. In its summary judgment papers, Defendant provides a copy of a proposed settlement agreement Plaintiff previously sent to an alleged infringer. The proposed agreement contains a confidentiality clause stating the terms of the agreement shall be kept confidential "except as required by an order from a court of law." Thus, to the extent other settlement agreements contained similar language, there would be no breach for a court ordered unsealing of settlement agreement terms. But as none have been provided to the Court, no such determination can be made. Even so, the Court does not find Plaintiff's conclusory statements of harm a compelling reason to keep the payment terms of each settlement agreement redacted….

As for names of the third parties making settlement payments pursuant to each settlement agreement in Exhibits SS and RR, the Court finds those redactions to be proper. Courts in this circuit have routinely found that an invasion of third-party's privacy interest constitutes a compelling reason to seal or redact identifying information of third parties….

Plaintiff's subscription pricing terms are available to the public, including any competitors, on its website (https://www.preparedfoodphotos.com/stock-photo-subscription/), as are the terms of use. Such available information does not qualify as a trade secret when it is already loose in the public domain. Moreover, Defendant does not seek to disclose the terms of each subscriber agreement in the entirety, only the name of the subscriber, the monthly payment amount, and the months of payment. To the extent the pricing terms vary from the advertised price on Plaintiff's website, the potential for resulting discord between Plaintiff and its customers is not a compelling reason to keep such terms sealed…. "The mere fact that the production of records may lead to a litigant's embarrassment, incrimination, or exposure to further litigation will not, without more, compel the court to seal its records." …

Finally, it is unclear how a competitor might poach Plaintiff's former subscribers as it argues will inevitably be the case. A review of Exhibit KK supports Defendant's contention that many of the subscribers listed in Exhibit OO appear to no longer be customers of Plaintiff. Plaintiff does not present any additional argument constituting a compelling reason why the identity of former customers should remain sealed. Therefore, Exhibit OO may be filed with the names of former subscribers unredacted. The names of current subscribers/customers shall remain redacted [presumably on the theory that current customer lists are generally treated as trade secrets and therefore presumptively confidential -EV].

Paul Alan Levy (Public Citizen), Phillip Malone (Stanford Law School, Juelsgaard Intellectual Property & Innovation Clinic), and Stephen Thomas Kirby (Kirby Law Office PLLC) represent defendant. Thanks to Griffin Klema for the pointer.

The post Past Copyright Settlement Agreements Needn't Be Sealed When Directly Related to Merits of Current Claim appeared first on Reason.com.

[Stewart Baker] The U.S. Can't Afford AI Copyright Lawsuits

[ It's time for President Trump to invoke the Defense Production Act and resolve the crisis.]

I have a new post at Lawfare making this argument. Here's a summary:

Anthropic just paid $1.5 billion to settle a copyright case that it largely won in district court. Future litigants are likely to hold out for much more. A uniquely punitive provision of copyright law will allow plaintiffs who may not have suffered any damage to seek awards in the trillions. (Indeed, observers estimated that Anthropic dodged $1 trillion in liability by settling.) The avalanche of litigation, already forty lawsuits and counting, doesn't just put the artificial intelligence (AI) industry at risk of spending their investors' money on settlements instead of advances in AI. It raises the prospect that the full bill won't be known for a decade, as different juries and different courts reach varying conclusions.

A decade of massive awards and deep uncertainty poses a major threat to the U.S. industry. The Trump administration saw the risk even before the Anthropic settlement, but its AI action plan offered no solution. That's a mistake; the litigation could easily keep the U.S. from winning its race with China to truly transformational AI.

The litigation stems from AI's insatiable hunger for training data. To meet that need, AI companies ingested digital copies of practically every published work on the planet, without getting the permission of the copyright holders. That was probably the only practical option they had. There was no way to track down and negotiate licenses with millions of publishers and authors. And the AI companies had a reasonable but untested argument that making copies for AI training was a "fair use" of the works. Publishers and authors disagreed; they began filing lawsuits, many of them class actions, against AI companies.

The American public will likely have little sympathy for a well endowed AI industry facing the prospect of hiring more lawyers, or even paying something for the works it copied. The problem is that peculiarities of U.S. law—a combination of statutory damages and class action rules—allow the plaintiffs to demand trillions of dollars in damages, a sum that far exceeds the value of the copied works (and indeed the market value of the companies). That's a liability no company, no matter how rich and no matter how confident in its legal theory, can ignore. The plaintiffs' lawyers pursuing these cases will use their leverage to extract enormous settlements, with a decade-long effect on AI progress. At least in the United States. China isn't likely to tolerate such claims in its courts.

This is a major national security concern. The US military is already building AI into its planning, and the emerging agentic capabilities of advanced AI holds out the prospect that future wars will become contests between armies deploying coordinated masses of autonomous weapons. Even more startling improvements in AI could come in the next five years, with transformative consequences for militaries that capitalize on them as well as those that don't. Not surprisingly, China is also pursuing military applications of AI. Given the US stake in making sure its companies do not fall behind China's, anything that reduces productive investment in AI development has national security implications. As Tim Hwang and Joshua Levine laid out in an earlier Lawfare article, this means the U.S. can't afford to let the threat of enormous copyright liability hang over the AI industry for the decade or more it could take the courts to reach a final ruling.

The Trump administration should cut this Gordian knot by invoking the Defense Production Act (DPA) and essentially ordering copyright holders to grant training licenses to AI companies on reasonable terms to be determined by a single Article I forum. This is the only expeditious way out of the current mess. It is consistent with the purpose and with past uses of the DPA. And it creates a practical solution that copyright holders have long used in similar contexts.

The post The U.S. Can't Afford AI Copyright Lawsuits appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers