Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 36

September 15, 2025

[David Bernstein] Campus Violence and Threats Against Jewish Students Since October 7, Part I

For obvious reasons, everyone is talking about political violence in the US. Coincidentally, I have been working on two lists for an appendix to an article I am writing about hostile environment law. The first list, below, is of actual physical battery. The second is of threats and intimidation against Jewish individuals or institutions like Hillel. Since the article is not done and won't be out for a while, I thought it would be helpful to others working on related topics, and of course to curious blog readers, to see these lists. Note that these are not complete lists, but only contain incidents regarding which I could find public sources. I know of two cases of battery against Jewish students, one at Johns Hopkins and one at George Mason, that aren't on my list, and presumably there are many more. Note that while some of these incidents are more serious than others, they are listed in chronological order, not order of gravity.

Part I. Assaults and Physical Violence

This section documents reported incidents of physical violence directed against Jewish students or visibly Jewish individuals on or adjacent to U.S. university campuses. Entries are arranged in chronological order. For reading ease, I will delete the citations, but I'm happy to send them to anyone who requests them. Most of these assaults are attributable to anti-Israel activists, but in some cases the precise motivation (beyond targeting a Jewish student or students) is unknown.

Drexel University (Oct. 2023) — (Philadelphia, PA)

The door of a Jewish student's dorm suite in Race Hall was intentionally set on fire. The incident was investigated as arson and antisemitic harassment by local police and federal authorities.

Oct. 26, 2023 – Tulane University (New Orleans, LA):

During a campus rally in support of Israel, an anti-Israel counter-protestor swinging a pole struck a Jewish student in the face, causing visible injuries. Tulane police confirmed arrests.

Nov. 5–6, 2023 – UMass Amherst (Amherst, MA):

After an Israel solidarity event, a Jewish student carrying a flag was punched and the flag spat on. The suspect was arrested and barred from campus.

Nov. 10, 2023 – Ohio State University (Columbus, OH):

Two Jewish students were attacked near campus, with one reporting he was punched 'because he was Jewish.' The case was investigated as a hate crime.

Nov. 2023 – Harvard University (Cambridge, MA):

A Jewish student recording a protest 'die-in' at Harvard Business School was physically assaulted by demonstrators. Two students were charged with assault and battery. In February 2025, a Boston judge dismissed hate crime charges, but assault charges remained; the defendants were referred to a first-offender program.

February 26, 2024 – UC Berkeley (Berkeley, CA):

Students broke into Berkeley's Zellerbach Playhouse and rioted outside an event organized by Jewish student groups featuring an Israeli speaker. Approximately 200 protesters surrounded the building, chanting "Intifada" and "You can't run! You can't hide! We charge you with genocide!" while banging on the building's windows and doors. Students attempted to attend the event were harassed and assaulted by the protesters. One student was grabbed by the neck and another student was spat upon. Protesters shattered windows and broke open an entrance to the building. The audience to be evacuated from the building under a police escort. Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ and Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Ben Hermalin publicly acknowledged reports that Jewish students were subjected to "overtly antisemitic expression" including "allegations of physical battery, as hate crimes."

March 4, 2024 – Tufts University (Medford, MA):

At a student government meeting discussing anti-Israel resolutions, a Jewish student reportedly asked an anti-Israel student to stop laughing as the pro-Israel Jewish students presented their position. In response, the laughing student said, "Shut up b*tch," and spat on the Jewish student.

Apr. 25–May 2, 2024 – UCLA (Los Angeles, CA):

During the Palestine Solidarity encampment, Jewish students reported being physically blocked from entering parts of campus. A federal judge later ruled UCLA had failed to protect equal access.

Jewish students also reported: (1) a Jewish student who was lawfully filming the encampment being slapped by a UCLA teaching assistant; (2) another Jewish student was pepper-sprayed by a protestor; (3) a student from Israel being assaulted by protestors.

April 2024 - Northwestern University (Chicago, IL)

At the Northwestern "encampment," a Jewish Northwestern student photojournalist was identified by a masked student by name and physical description to hundreds of encampment members. Protestors then surrounded the student, shouting, "Shame! Shame! Shame!" In a separate incident, an encampment members assaulted a Jewish Northwestern student lawfully recording the encampment. Jewish students reported ordered to "go back to Germany and get gassed" and were spat at while walking past the encampment." [This one is on the borderline between intimidation/threat and battery, depending on where the spit landed.]

April 29, 2024 – Princeton (Princeton, NJ)

Jewish student David Piegaro was filming the aftermath of the arrests of several students involved with a Princeton encampment when a man, who later turned out to be a Princeton administrator, grabbed him and threw him down the marble stairs of a building. Piegaro suffered a concussion and rib injuries. Princeton officials pressed charges against Piegaro, claiming that he initiated the incident by bumping into the administrator's arm. Piegaro was found not guilty at trial by a judge, and now has a lawsuit pending against Princeton.

April 30, 2024 – Yale (New Haven, CT):

Protesters at Yale established checkpoints around the green guarded by so-called "marshals." These "marshals" physically prevented entry unless one was committed to "being committed to Palestinian liberation and fighting for freedom for all oppressed peoples." As a result, numerous Jewish students were physically prevented from accessing relevant areas of campus.

May 1, 2024 – UCLA (Los Angeles, CA):

Jewish student Elinor Hess was shoved, kicked, and pulled by the hair while attempting to retrieve a flag that fell within an anti-Israel encampment. She sustained a concussion and required medical treatment. The assailant was initially charged with felony assault, but prosecutors later downgraded the charges to misdemeanors.

Jun. 10–11, 2024 – UCLA (Los Angeles, CA):

Rabbi Dovid Gurevich of UCLA Chabad was surrounded by masked protesters, called 'pedophile rabbi' and told to 'go back to Poland,' and had his phone knocked away. Sources: The Forward:

May 2024 – Reed College (Portland, OR):

After antisemitic vandalism in dorms, a Jewish student was struck in the head with a rock while in her room, sustaining injuries. The attack was captured on surveillance cameras.

Aug. 31, 2024 – University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA):

Two Jewish students wearing kippot were assaulted in Schenley Plaza, one struck with a bottle and suffering a concussion. Police arrested suspects.

Sept. 15, 2024 – University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI):

A Jewish student was assaulted outside a dorm and subjected to antisemitic slurs. Police classified it as aggravated assault and ethnic intimidation.

Sept. 27, 2024: University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA):

A Jewish student at the University of Pittsburgh wearing a Star of David necklace was attacked by a group of people who used antisemitic language.

Apr. 2024 – Yale University (New Haven, CT):

Student journalist Sahar Tartak was assaulted while covering a protest, when a demonstrator jabbed her in the eye with a flagpole. She lost consciousness and was hospitalized.

Apr. 2024 – Emory University (Atlanta, GA):

At a protest outside Emory Chabad, a Jewish student was shoved and verbally abused. Chabad leaders described the attack as part of a climate of intimidation.

Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD):

An Israeli doctoral student was attacked during a pro-Palestinian protest. The university confirmed video evidence and promised to investigate.

November 6, 2024 - DePaul University (Chicago, IL)

Two Jewish students were physically assaulted by masked attackers while visibly supporting Israel. The attackers shouted antisemitic remarks during the attack. In April 2025, one suspect, Adam Erkan, was formally charged with a hate crime and aggravated battery in connection with that November 2024 assault. Another suspect remains at large.

Dec. 10, 2024 – Columbia University (New York, NY):

During a campus rally, a Jewish student was punched in the face. Columbia confirmed that disciplinary proceedings were underway.

July 31, 2025 – Florida State University (Tallahassee, FL):

A female graduate student approached a male student in the campus library who was wearing an Israeli Defense Forces t-shirt. After engaging in an expletive-laden tirade, she shoved him while apparently reaching for his drink. The offending student was arrested and charged with misdemeanor battery, and expelled from FSU.

Dates unknown – George Mason University (Fairfax, VA):

In a letter to the university community, university president Greg Washington alluded to two occasions on which "George Mason experienced unlawful activity associated with violent antisemitic actions by students."

The post Campus Violence and Threats Against Jewish Students Since October 7, Part I appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Transgender Kent State Prof Loses First Amendment + Discrimination Claim Related to "Weeks-Long, Profanity-Laden Twitter Tirade Insulting Colleagues and the University"

A short excerpt from the long decision in Patterson v. Kent State Univ., decided Friday by Judge John Nalbandian, joined by Judges Danny Boggs and Richard Allen Griffin:

GPat Patterson, a transgender professor at Kent State University, sued the university on several discrimination and retaliation claims. The claims arise out of Kent State's response to Patterson's weeks-long, profanity-laden Twitter tirade insulting colleagues and the university….

Patterson alleged that certain university actions—"(1) the Dean revoking her offer to lighten Patterson's credit load, (2) the Dean's '[r]evocation' of Patterson's leadership role in the Center, and (3) the English department's denial of the tenure-transfer request" through which Patterson sought to transfer] "from Kent State's Tuscarawas campus to the English department on the main campus"—were discriminatory or retaliatory. No, said the court.

[A.] The court concluded that the actions weren't retaliation against First-Amendment-protected speech:

[To be protected against retaliation by a public employer, the plaintiff's] speech must address a matter of public concern, and the plaintiff's interests in speaking on those matters must outweigh the state's interest in promoting effective and efficient public services….

Speech involves a matter of public concern when it deals with "any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community." "The linchpin of the inquiry is … the extent to which the speech advances an idea transcending personal interest or opinion" and instead impacts our shared social or political life. Allegations of public corruption, for example, touch on matters of public concern. So do remarks about government inefficiency or major government policy decisions. And so do statements exposing governmental discrimination.

On the other hand, speech about internal personnel disputes or management doesn't cut it. Run-of-the-mill "employee beef" doesn't implicate the public concern just because it's been spilled to the public. That's because "the First Amendment does not require a public office to be run as a roundtable for employee complaints over internal office affairs." The government, as an employer, must "enjoy wide latitude in managing [its] offices, without intrusive oversight by the judiciary in the name of the First Amendment." Put simply, "complaining about your boss and coworkers is not protected by the First Amendment just because you work for the government."

Patterson's tweets didn't involve a matter of public concern. The gist of the month-long diatribe was to complain about [Dean] Munro-Stasiuk's and [Prof.] Mazzei's decisions on how to handle new academic programming. Munro-Stasiuk and Mazzei were repeatedly called out as "cishet white admin ladies" engaged in "F*ckery," "shit," "trans antagonism," and "epistemic violence" who were "quite literally killing [Patterson]." Mazzei was singled out as a "usurper" and "cishet white admin with zero content expertise" whose field of study was a "sentient trash heap," and who was guilty of "back-stabbery" and "horizontal violence." These are complaints about other Kent State faculty members and their workplace decisions—"employee beef," plain and simple.

The tweets are insulting, disparaging, and targeted. They use profanities, and they describe Munro-Stasiuk and Mazzei in terms of their race and sex. Complaining about and insulting your coworkers simply doesn't implicate a matter of public concern.

Patterson frames the tweets as publicizing Kent State's alleged transphobia and exposing discrimination in the workplace. In fairness, a few tweets do make more general references that sound less like targeted insults. For example, one tweet states: "Academia is fundamentally racist, heterosexist, cissexist, ableist, classist & sexist." In isolation, perhaps that qualifies as protected speech. But the tweet is swarmed on either side by other attacks on Munro-Stasiuk and Mazzei. Indeed, that same tweet's very next sentence accuses Professor Mazzei of "violen[ce]." A public employee can't blend protected speech with "caustic personal attacks against colleagues," and then use the protected speech to immunize those attacks.

And even if the tweets did involve a matter of public concern, they still wouldn't receive protection. Kent State's interest as an employer in administering effective public services outweighs Patterson's interest in this kind of trash talk.

There's a way to raise awareness of discrimination without engaging in profanity-laced and race- and sex-based aspersions against colleagues. The tweets created serious strife within the Kent State community, causing Munro-Stasiuk and Mazzei to feel harassed and insulted. And it led to a dysfunctional work environment for several months.

Mazzei had to text Munro-Stasiuk, for example: "I'm really thinking continuing [having Patterson involved] is unhealthy for the potential program and school, at this point. It's clearly already having an impact. I have concerns." Munro-Stasiuk also testified to how noxious things had gotten. "The foundation of [revoking the offer]," she stated, "was the toxic, hostile tweets that Dr. Patterson had been posting over the course of over a month …. [I]t was escalating, continually targeting [Mazzei], in particular, continually targeting Lauren Vachon and Suzanne Holt, to a certain extent myself." The Dean discussed how Patterson had "show[n] over, and over, and over again" a refusal to be collaborative or respectful and was "completely trying to undermine the process." In short, Patterson had compromised any "ability to lead any initiative" and any "ability to work in the Center, or the [major.]"

Kent State's business is educating students. When an employee seriously undercuts the university's power to do its basic job, the Constitution doesn't elevate the employee over the public that Kent State exists to serve.

All told, "[t]he First Amendment does not require a public employer to tolerate an embarrassing, vulgar, vituperative, ad hominem attack, even if such an attack touches on a matter of public concern." When "the manner and content of an employee's speech is disrespectful, demeaning, rude, and insulting, and is perceived that way in the workplace, the government employer is within its discretion to take disciplinary action."

Here's a longer excerpt of the Tweets:

June 19: Patterson criticized the "two cishet1 white ladies in charge, with [no] content expertise in this area" (Mazzei and Munro-Stasiuk) and called Mazzei a "usurper."June 23: In response to the idea that insulting colleagues on social media was "unprofessional," Patterson wrote, "No the fuck it isn't."June 26: "Academia is fundamentally racist, heterosexist, cissexist, ableist, classist & sexist…. [B]lock[ing] multimarg2 faculty from leading is violent."June 29: Clarifying who the tweets were about, Patterson referred to people "on the main campus" (Munro-Stasiuk and Mazzei) acting in "a kind of translash." "[T]he minute I raise an equity issue, I'm suddenly read as a problem to be neutralized." Patterson also denounced Kent State's "[i]nstitutional transphobia" and "overt trans antagonism."June 30: "I wish there'd have been a grad practicum called Oh, The Places They'll Go: How to Navigate F*ckery as a Multimarg Faculty Member." Patterson again criticized "the white cishet admin with zero content expertise" who would be leading the new major (Mazzei).July 3: "Thanks for coming to my TED talk on how u can claim to be a trans ally all you want, but if you pull sh*t to bar trans ppl's access to life chances, ur still a transphobe. Also, if ur a bystander who watches someone do this mess & don't intervene? Also a transphobe."July 5: Patterson criticized "individual back-stabbery" and the "horizontal violence … [of people in higher education] who see you as competition & want you to fail," and declared that "the whole damn system is killing you a bit more each day."July 6: "I need you to understand the death-dealing & soul-murdering consequences that result from profoundly privileged administrators not grasping the insidiousness with which inequity & violence show up in multimarg faculty & staff workplaces. Y'all are quite literally killing us."July 8: "Absolutely zero surprise it's a poli sci prof. Forgive the generalization but that discipline is a sentient trash heap."July 10: "I'd like to talk about the epistemic violence of a university attempting to create a [gender-studies] major, but blocking scholars, with whole PhDs in the discipline, from leading the effort. Please. Tell me another discipline where admins try to pull this shit. I'll wait."

[B.] The court also concluded that Patterson hadn't sufficiently shown evidence of transgender identity discrimination. Among other things, the court reasoned,

Patterson … points to the committees' discussion of whether the English department needed more faculty with backgrounds in LGBT studies, claiming that this is direct evidence of discrimination. That argument conflates a professor's scholarly discipline with a professor's personal traits. An Italian person may offer to teach Italian classes, but if a university doesn't need more Italian classes, that's not direct evidence of animus against Italian people. So there's no direct evidence of discrimination….

And the court concluded there wasn't enough circumstantial evidence of such discrimination, either.

[C.] And the court rejected Patterson's claim of discrimination based on perceived disability:

The disability claim rests on one stray remark that Professor Holt made to Mazzei. Recall that Patterson sent several messages to Holt and Lauren Vachon venting at Mazzei; Holt and Vachon then became worried about whether they could work with Patterson. In her deposition, Mazzei recalled Holt saying "that she [Holt] had very deep concerns about Dr. Patterson's stability, mental stability, and that the communications were spiraling downward." Patterson points to this "mental instability" reference to invoke the disability protections of the Rehabilitation Act.

This isolated comment is not the kind of evidence that courts have found satisfies the "regarded as disabled" definition. "Personality conflicts among coworkers (even those expressed through the use (or misuse) of mental health terminology) generally do not establish a perceived impairment on the part of the employer." Holt's remark simply expressed her concern about Patterson's uncollegial and unprofessional attitude. At most, it is a "mere scintilla" of evidence—insufficient to survive summary judgment.

Daniel James Rudary (Brennan Manna & Diamond, LLC) represents the university.

The post Transgender Kent State Prof Loses First Amendment + Discrimination Claim Related to "Weeks-Long, Profanity-Laden Twitter Tirade Insulting Colleagues and the University" appeared first on Reason.com.

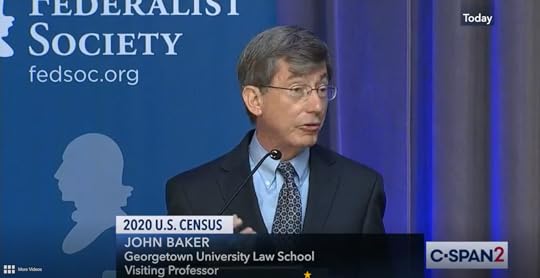

[Josh Blackman] RIP Professor John S. Baker, Jr.

I am very sad to relay that Professor John S. Baker, Jr. has passed away. John was an iconic constitutional law professor. John also taught a separation of powers seminar with Justice Scalia for two decades. I regret never taking this class when I had the chance. John will be deeply missed.

The James Wilson Institute posted this remembrance:

JWI Remembers Professor John S. Baker, Jr. 1946 - 2025

Professor Emeritus of Law John S. Baker, Jr., Louisiana State University

September 12, 2025

Dear Friend,

The James Wilson Institute joins all of those mourning the recent loss of our dear friend and affiliated scholar, Professor John S. Baker. Following years of slow decline in health due to complications from a life-saving surgery, Professor Baker passed on September 6th.

While Professor Baker's passing represents an immense loss to the conservative legal movement, his memory will be long maintained by generations of his former students as well as practitioners who have benefited from his intellect, guidance, and mentorship. Baker was a profound educator talented in the classroom, both in the United States and abroad.

Baker was a leading authority on originalism, natural law, separation of powers, criminal law, and federalism with a mastery that was demonstrative of not only his brilliance, but also his passion. He was also an advocate. Baker famously argued before the Supreme Court in 1984 the religious freedom case of Wallace v. Jaffree. We link to the transcript of his argument here.

A significant presence within the Federalist Society, Baker helped lead a variety of book clubs and seminars, most notably the Federalist Society's Separation of Powers Seminar co-taught with Justice Antonin Scalia for twenty years. Attendees of that seminar over the decades often described it as a highlight of their careers. Baker was also a regular contributor at JWI's Senior Seminar, from its inception fourteen years ago, where his presence and voice was a cherished constant by other JWI scholars.

JWI Founder & Co-Director Hadley Arkes shares, "John Baker became one of the most devoted and leading figures in our Senior Seminar. He was a remarkable teacher at every turn, whether in a seminar, or walking among students in a large audience to draw them out and get his points through. There was nothing passive about him. His imagination and energy were persistently engaged. He was ever at work in creating new programs in this country, and exploring the possibility of imparting the premises of our constitutional order to a new generation in China. He was tenacious as an advocate and teacher—and unbreakable as a friend. And at every turn, he was the best of company. But at the very core he was a serious Catholic, and through it all, in arguments made with verve, there was also the thread of love—for the subject and for the telos, the end, to which everything in his life was so surely directed."

In his memory, we would like to share with you a 2016 panel tribute to Justice Antonin Scalia featuring Professor Baker, Professor Arkes, and other esteemed thinkers. Click here to watch that tribute now.

We send our deepest condolences to his wife Dayle, his family, and friends. Details on funeral services in the next week may be found here.

About Professor Baker

Professor Baker previously served as the Dale E. Bennet Professor of Law at the Louisiana State University's Paul M. Herbert Law Center before coming Emeritus Professor of Law. He received his B.A. from the University from Dallas, JD from the University of Michigan Law School, and Ph.D. from the University of London. During his extensive teaching career, Professor Baker taught at the various law schools of New York University, Pepperdine, Tulane, George Mason, Hong Kong University, and the University of Dallas School of Managment. Baker was a Fulbright Fellow and Specialist and also held visiting professorships at Georgetown University and Oriel College, Oxford.

The post RIP Professor John S. Baker, Jr. appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Nina Jankowicz, Former "Disinformation Governance Board" Director, Loses Libel Suit Against Fox

From Friday's decision in Jankowicz v. Fox News Network, LLC, decided by Third Circuit Judge L. Felipe Restrepo, joined by Stephanos Bibas and Cindy Chung:

[A.] Appellant Nina Jankowicz [was the] Executive Director of the Department of Homeland Security's … Disinformation Governance Board … "from March 2, 2022, through May 18, 2022." The Board "had no operational capabilities" and "existed to study how other components of DHS with operational authority responded to disinformation, recommend best practices that complied with constitutional and other civil liberties, and coordinate operational DHS components' discussion of their work concerning disinformation threatening national security."

Jankowicz alleges that "immediately after DHS announced the creation of the Board in late April 2022," Fox became "obsess[ed]" with her, "ridicul[ing]" and "bullying Jankowicz day in and day out." Fox hosts and guests also frequently attacked the Board, sometimes displaying Jankowicz's image on screen while doing so, accusing it of being a "Ministry of Truth" that was trying to "take away your free speech." In response to these attacks, "DHS, Secretary Mayorkas, former officials, and even the White House Press Secretary" repeatedly sought to clarify the Board's limited operational capacity and dispel "the story Fox was telling about Jankowicz and the Board." Fox, however, "continued to level the same accusations about Jankowicz and the Board."

In May 2022, Fox programs repeatedly commented on a 2021 video in which Jankowicz had discussed a Twitter pilot program named "Birdwatch." Though Jankowicz asserts that her 2021 comments showed a "deep concern about allowing the government—or certain individuals—to control information," Fox's hosts and guests "repeatedly stated that Jankowicz had said she wanted to edit other Twitter user[s'] posts."

On May 18, 2022, in response to the backlash against the Board, "DHS officials announced that the Board was being 'paused.'" Though Jankowicz had been offered "the opportunity to stay on with the agency as a policy advisor while the Board's future was under review," she elected to resign instead. Fox programs celebrated Jankowicz's resignation, saying that she "got booted," that DHS "had to yank" her, and that a video parody posted by Jankowicz had been "so embarrassing that the Biden administration had to fire" her.

Jankowicz sued Fox for defamation. Jankowicz's … Complaint … detailed a litany of purportedly defamatory statements made by Fox, which she characterized as largely falling into "three categories": (1) "that Jankowicz intended to censor Americans' speech"; (2) "that Jankowicz was fired from DHS"; and (3) "that Jankowicz wanted to give verified Twitter users the power to edit others' tweets." …

[B.] The court concluded that the statements about the Board weren't sufficiently "of and concerning" Jankowicz to allow her to sue over them:

Jankowicz argues that the many statements made by Fox about the Board were also of and concerning her because "Fox repeatedly used Jankowicz's photo when discussing the Board" and because "Fox often referenced the Board and Jankowicz in the same statement or the same segment." But these allegations are not enough to transform criticism of the Board into statements of and concerning Jankowicz.

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court sought to avoid "transmuting criticism of government, however impersonal it may seem on its face, into personal criticism, and hence potential libel, of the officials of whom the government is composed." Doing so, the Court held, would "strike[ ] at the very center of the constitutionally protected area of free expression." Accordingly, when a government official sues for defamation, "[t]here must be evidence showing that the attack was read as specifically directed at the plaintiff."

Jankowicz's position—that criticism of government is transformed into actionable defamation when a television program displays an image of a government official or references a government official's name in the same segment—is precisely the sort of attack on core free expression rights that Sullivan sought to avoid. Nor does merely referencing an official in the same segment that a critique of government is made—nor using an official's photo as "a visual placeholder," in that segment—show that an "attack was read as specifically directed at the plaintiff."

[C.] The court went on to hold that the statements that were specifically about Jankowicz were "either opinion or was substantially true":

In her briefing, Jankowicz identifies three categories of statements about "Jankowicz and the Board's authority, intentions, and the fabricated threat they posed to Americans' free speech" that she asserts are actionable: (1) "claims about how Jankowicz would 'censor' Americans"; (2) "claims about how Jankowicz would 'surveil' Americans"; and (3) "claims about how Jankowicz would physically harm or imprison Americans."

[1.] As an initial matter, many of the statements Jankowicz references were directed at the Board and were not of and concerning her, as discussed supra. {For example, Jankowicz alleged that Fox called the Board "this bureau that's going to spy and target Americans[,]" and accused it of "controlling what you say[,]"} The vast majority of the remaining statements were speculation and conjecture about Jankowicz's motives, goals, and future actions, of which the truth or falsity were not readily verifiable. {For example, Jankowicz took issue with a statement that "DHS was planning a bigger censorship campaign push" where Jankowicz "[was] going to coordinate with Twitter … to basically censor things."} … "[P]resumptions and predictions as to what 'appeared to be' or 'might well be' or 'could well happen' or 'should be' would not have been viewed by the average reader … as conveying actual facts about plaintiff." … Much of this speculation was interlaced with hyperbole, which "is simply not actionable," making it more evidently opinion. {For example, Jankowicz alleges that a Fox host speculated that she "will be the czar of information with this presidency" who "will be telling you what's true and what's not—maybe you'll go to jail."}

The few non-speculative statements identified in the complaint concerning Jankowicz's authority and opposition to free speech were likewise opinion. Many were hyperbolic descriptions of Jankowicz's job description, such as a statement painting her as "our new disinformation minister," that conveyed mere opinion regarding the perceived dangers of her role. The rest described her current activities as Executive Director, where she was generally described as "censoring" Americans, and having "thought control[,]" over public discourse.

Once again, these statements used hyperbolic language and politically-charged words like "censorship" that, in context, lacked a precise, readily-understood, and falsifiable meaning. As the District Court correctly noted, while "censorship" can encompass "the actual removal of text or video from the public realm[,]" it "can also be understood to encompass efforts to restrain or suppress certain kinds of speech." Such an amorphous political accusation cannot be assessed as true or false until the term is given a more precise meaning and thus, these statements lack the precision to give rise to a defamation claim. Without a precise and falsifiable meaning, these statements cannot be actionable.

Lastly, the broader social context and surrounding circumstances of these statements would also have signaled to viewers that the statements were opinion and not fact. The Board was, as fairly characterized by the District Court, "a hypercharged subject of political debate," and the challenged statements were made in a political commentary context. "[E]ven apparent statements of fact may assume the character of statements of opinion, and thus be privileged, when made in public debate, heated labor dispute, or other circumstances in which an 'audience may anticipate [the use] of epithets, fiery rhetoric or hyperbole.'" That the challenged statements were made in a public discussion of a hot-button political issue only further indicates that they were opinion in nature….

[2.] The court also concluded that Fox's allegations of Jankowicz having been essentially fired were "substantially true":

Jankowicz splits hairs regarding Fox's description of her departure from DHS. By her own description, the Board was "paused"—thereby eliminating her position as Executive Director—and she was offered "the opportunity to stay on with [DHS] as a policy advisor while the Board's future was under review." She chose instead to resign. Fox's description of this sequence of events as Jankowicz being fired, "booted" and "yank[ed]" is substantially true….

[3.] And the court concluded that Fox's statement "that Jankowicz wanted to give verified Twitter users the power to edit others' tweets" was likewise substantially true:

In her complaint, Jankowicz quotes an interview in which she discussed a proposed Twitter feature named Birdwatch which, by her own words, would let "verified people … essentially start to 'edit' Twitter, the same sort of way that Wikipedia is, so they can add context to certain tweets." She described this feature as "interesting to [her,]" and said "I like that. I like the idea of adding more context to claims and tweets and other content online, rather than removing it." Jankowicz also said, however, that "we're going to have problems scaling it up, and it's not a solution that works for everything" and concluded that "I'm not sure it's the solution."

Jankowicz contends that this was not an endorsement of the feature, and that she merely "said 'I like that' about adding context to tweets." But by her own description, the mechanism by which users would "add context to certain tweets" was by "'edit[ing]' Twitter, the same sort of way that Wikipedia is." … Because Jankowicz expressed appreciation for the Birdwatch feature—even though she noted it was not a global solution to Twitter's problems—it was substantially true to say she had "pitched" it and that the feature was "her fix." The "substance" and "gist" of these statements was that Jankowicz had expressed her approval of the feature, which is exactly what she had done….

Chase Harrington, Kyle West, and Patrick Philbin (Torridon Law) and John L. Reed, Peter Kyle, and Stephanie O'Byrne (DLA Piper) represent Fox.

The post Nina Jankowicz, Former "Disinformation Governance Board" Director, Loses Libel Suit Against Fox appeared first on Reason.com.

September 14, 2025

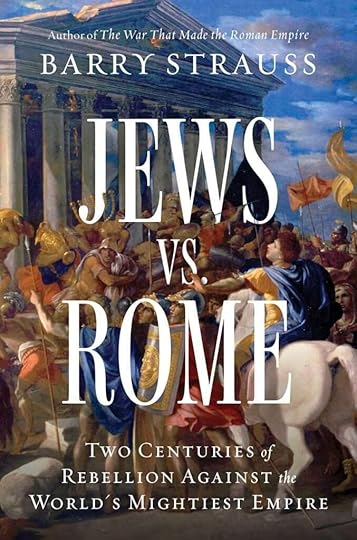

[Eugene Volokh] Barry Strauss Guest-Blogging About "Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World's Mightiest Empire"

I'm delighted to report that my Hoover colleague (and emeritus professor at Cornell), Barry Strauss, will be guest-blogging this week about this new book of his. Here's the publisher's summary:

A new history of two centuries of Jewish revolts against the Roman Empire, drawing on recent archeological discoveries and new scholarship by leading historian Barry Strauss.

Jews vs. Romeis a gripping account of one of the most momentous eras in human history: the two hundred years of ancient Israel's battles against Rome that reshaped Judaism and gave rise to Christianity. Barry Strauss vividly captures the drama of this era, highlighting the courageous yet tragic uprisings, the geopolitical clash between the empires of Rome and Persia, and the internal conflicts among Jews.

Between 63 BCE and 136 CE, the Jewish people launched several revolts driven by deep-seated religious beliefs and resentment towards Roman rule. Judea, a province on Rome's eastern fringe, became a focal point of tension and rebellion. Jews vs. Rome recounts the three major uprisings: the Great Revolt of 66–70 CE, which led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, culminating in the Siege of Masada, where defenders chose mass suicide over surrender; the Diaspora Revolt, ignited by heavy taxes across the Empire; and the Bar Kokhba Revolt. We meet pivotal figures such as Simon Bar Kokhba but also some of those lesser-known women of the era like Berenice, a Jewish princess who played a major role in the politics of the Great Revolt and was improbably the love of Titus—Rome's future emperor and the man who destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple.

Today, echoes of those battles resonate as the Jewish nation faces new challenges and conflicts. Jews vs. Rome offers a captivating narrative that connects the past with the present, appealing to anyone interested in Rome, Jewish history, or the compelling true tales of resilience and resistance.

And the blurbs:

"Judaism as we know it today is not the Judaism of the Bible—it is the Judaism that emerged from the destruction of the Second Jewish Commonwealth at the hands of the Romans. As Barry Strauss illustrates in this riveting account, this pivotal period was defined by conflicting values and visions among Jews, corruption of their religious institutions, infighting when they could least afford it and much more that our own time eerily echoes. This stunning account leaves us with a much deeper understanding of not only the Jews' past, but their present as well, and perhaps even their future." — Daniel Gordis, author of Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn

"Historian Strauss hits another home run with this thorough account of the tumultuous relations between Rome and its most contentious subjects, the Jews, in ancient times…. There is no better history of this important but little-known subject." — Library Journal (starred review)

"Incisive, timely, and thought-provoking, Jews vs. Rome is an insightful history of the way implacable faith and resistance fueled two centuries of Judea's doomed blows against the Empire. Barry Strauss is a master at illuminating the strong personalities, complex motives, and turbulence during Rome's struggle to control the Middle East." — Adrienne Mayor, Research scholar, Department of Classics and History and Philosophy of Science, Stanford University, and author of Flying Snakes and Griffin Claws, and Other Classical Myths, Historical Oddities, and Scientific Curiosities

"For two hundred years, the Jews fought the world's greatest power–Imperial Rome–and by doing so, won their rightful place as one of history's most consequential people. Told by the master historian of the ancient world, this is a wonderful and important read." — Karl Rove, former White House Senior Advisor and Deputy Chief of Staff and author of The Triumph of William McKinley

"Jews vs. Rome retells, with passion and immediacy, the Jews' continuous confrontations with the great power of Rome and their own unceasing, often violent internal disputes, and ultimately indicates an enduring spiritual strength to explain their survival as a people. Behind the story of survival is a dire warning against disunity in perilous times." — Jonathan J. Price, the Fred and Helen Lessing Professor of Ancient History, Departments of Classics and General History, Tel Aviv University

The post Barry Strauss Guest-Blogging About "Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World's Mightiest Empire" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Jonathan H. Adler] Looking for Partisan Patterns in the Shadow Docket

[The New York Times examines the "sharp partisan divides" on the Supreme Court's interim docket.]

In today's New York Times, Adam Liptak takes a look at the "sharp partisan divides" on the Supreme Court's "emergency docket" (aka the "shadow docket" or "interim docket").

The story notes that the Trump Administration has sought emergency or interim relief more often than did the Biden Administration, and has had more success--prevailing in 84 percent of such cases compared to 53 percent during the Biden Administration. "That is perhaps unsurprising, given that the court is dominated by six Republican appointees," Liptak writes.

The story notes that there appears to be an ideological or partisan pattern in the justices votes on such orders.

The emergency docket presents a different portrait of the court, one in which partisan affiliations map onto voting patterns quite closely, reinforcing the declining public confidence in the court reflected in opinion polls.

On the far right side of the court, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. voted with the Trump administration 95 percent of the time and the Biden administration just 18, for a gap of 77 percentage points.

On the far left, the size of the gap was identical, but in the other direction. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson favored the Biden administration by 77 percentage points.

These are striking numbers, but there are reasons for caution: "The cases the two administrations pursued were different, of course, making comparison inexact, and the concentrated volume and sheer ambition of President's Trump's applications dwarfed those of his predecessor."

The article has this to say about the Biden Administration's record seeking interim relief from the Court:

Despite the court's conservative supermajority, the Biden administration did obtain relief in a slight majority of its emergency applications, including ones involving a commonly used abortion pill and "ghost guns," which are kits that can be bought online and assembled into untraceable homemade firearms.

But victories like those were influenced by two factors.

Solicitor General Elizabeth B. Prelogar, like her predecessor in the first Trump administration and her successor in the current one, made strategic choices about which cases to bring to the court, generally choosing only ones with at least a fair prospect of success.

Second, more than two-thirds of the Biden administration's emergency applications took on rulings from the U.S. Court of Appeals from the Fifth Circuit. Opponents of the administration's policies and programs often filed challenges in that circuit, correctly anticipating that they would meet a favorable reception with its especially conservative judges. Still, those rulings often proved too conservative even for a generally conservative Supreme Court.

Moreover, in three cases in which the justices initially turned down the Biden administration's requests for emergency interim relief from Fifth Circuit rulings, the administration ultimately prevailed when the cases were set down on the merits docket for full briefing and argument.

For whatever reason, the article does not include a similar analysis of the second Trump Administration's record of success seeking interim relief.

It seems to me rather clear that the primary reason the Trump Administration has seen such success on the interim docket is because it has been very selective in deciding which cases to bring to the justices. The Trump Administration has aggressively pursued Supreme Court relief in cases where district courts lacked jurisdiction or provided overbroad or improper relief, but has acquiesced to the normal pace of litigation and appeals where the Administration's legal position is weak. It is no accident no case involving the Administration's attacks on law firms or universities has yet to reach the Court.

One can see how the Trump Administration has been selective and strategic just by looking at the numbers. According to Just Security there have been approximately 400 suits filed against he Trump Administration, over 125 of which have resulted in injunctions or other judicial orders blocking or staying the Administration action. So while the Trump Administration may have prevailed in 84 percent (16 of 19) applications, it remains the case that it has obtained Supreme Court relief in less than 15 percent of the cases in which its actions have been blocked or stalled by lower courts.

It is also fair to note that, as a general matter, the circuit courts of appeal were more likely to corral wayward district court orders during the Biden Administration than they have been in 2025. (See, for instance, how they handled suits against the "Social Cost of Carbon" EO.)

The story also notes that the Court refused to consider the propriety of universal injunctions when asked by the Biden Administration, but agreed to consider that question in Trump v. CASA. This is a fair point, but the story glosses over some important distinctions, such as that the brief at issue sought consideration of the scope of relief available under the APA, a more difficult question than that resolved in CASA that the Court has yet to address. More importantly, the Biden Administration combined its request for consideration of universal relief with review of the merits and, the latter of which was granted. As has been the Court's fairly consistent practice, a majority of justices saw no need to consider the scope of relief in that posture, perhaps because any judgment of the Court would, by its nature, apply nationwide.

My own view is that the Court's treatment of the second Trump Administration, to date, presents a very incomplete picture. More telling will be how the Court handles cases involving the Administration's more aggressive and more legally questionable actions, particularly those the Trump Administration has kept out of the shadows of the interim docket thus far.

The post Looking for Partisan Patterns in the Shadow Docket appeared first on Reason.com.

[Stephen E. Sachs] My Remarks at the Harvard Vigil

[On Charlie Kirk, violence, and speech.]

There's been some press coverage—The Harvard Crimson, Boston Globe—of the Charlie Kirk vigil last night at Harvard, where I spoke alongside several students as well as my colleagues Randy Kennedy and Adrian Vermeule. I thought I'd recount my remarks here to give them full context, as well as to give credit where credit's due. Below is the prepared text, adjusted to match its delivery, as best I can remember it:

Thank you.

I want to confess that I was a little apprehensive in accepting your invitation to speak.

First, I was worried that it would be presumptuous, as I feel that I know so much less of Charlie Kirk's life and work than so many of you do. I deeply appreciate the students who have spoken today.

Second, I was apprehensive that in a place like Harvard, mourning Charlie Kirk would make one a target of opprobrium or disgust. There are some who believe those deeply moved by Kirk's murder, the widowing of his wife, and the fatherlessness of his children, shouldn't be so moved unless they're willing to take as their own every statement Kirk made and every position Kirk held. Charlie Kirk helped to put on the table on college campuses a wide range of conservative views; that's why so many people are here, who don't all agree about everything. I feel that no one here should feel it their burden to defend everything that other people might believe in order to mourn his unjust death. In that, I'd agree with Jonathan Adler, who noted that one can be a martyr without having to be a saint.

Third, I was apprehensive that it could make one a more literal target, that there could be some wacko out there. As to that, Kirk's example is one of very real courage—not just physical courage, knowing the sort of threats he faced, but intellectual courage, the kind that's necessary to stand under a sign that reads "prove me wrong" and take the very real risk that the next person to step up to the microphone might do just that.

Kirk was, certainly, a gifted communicator. And some think that it's by the gifts of such communicators that a political or intellectual movement thrives or fails. That may be true—in the short run. But in the long run, what makes more difference is the courage to pursue the truth, the courage that leads you to seek out the chance to be proven wrong.

Scott Alexander once wrote that a short-term "focus on transmission" may be

part of the problem. Everyone … knows that they are right. The only remaining problem is how to convince others. Go on Facebook and you will find a million people with a million different opinions, each confident in her own judgment, each zealously devoted to informing everyone else.

Instead, he writes,

… Debate is difficult and annoying. It doesn't scale. It only works on the subset of people who are willing to talk to you in good faith and smart enough to understand the issues involved. And even then, it only works glacially slowly, and you win only partial victories. What's the point?

Logical debate has one advantage over narrative, rhetoric, and violence: it's an asymmetric weapon. That is, it's a weapon which is stronger in the hands of the good guys than in the hands of the bad guys. In ideal conditions (which may or may not ever happen in real life) … the good guys will be able to present stronger evidence, cite more experts, and invoke more compelling moral principles. The whole point of logic is that, when done right, it can only prove things that are true.

Violence, by contrast,

is a symmetric weapon; the bad guys' punches hit just as hard as the good guys' do. … [H]opefully the good guys will be more popular than the bad guys, and so able to gather more soldiers. But … the good guys will only be more popular … insofar as their ideas have previously spread through some means other than violence. …

Unless you use asymmetric weapons, the best you can hope for is to win by coincidence…. Overall you should average out to a 50% success rate. When you win, it'll be because you got lucky.

Remember, he writes,

You are not completely immune to facts and logic. But you have been wrong about things before. You may be a bit smarter than the people on the other side. You may even be a lot smarter. But fundamentally their problems are your problems, and the same kind of logic that convinced you can convince them. It's just going to be a long slog. You didn't develop your opinions after a five-minute shouting match. You developed them after years of education and acculturation and engaging with hundreds of books and hundreds of people. Why should they be any different? …

All of this is too slow and uncertain for a world that needs more wisdom now. It would be nice to force the matter, to pelt people with speeches and documentaries until they come around. This will work in the short term. In the long term, it will leave you back where you started.

If you want people to be right more often than chance, you have to teach them ways to distinguish truth from falsehood. If this is in the face of enemy action, you will have to teach them so well that they cannot be fooled. You will have to do it person by person until the signal is strong and clear. You will have to raise the sanity waterline. There is no shortcut.

I hope that Kirk's example will help remind us of this—of the need for the courage to pursue the truth, person by person—and that, zichrono livracha, his memory will be a blessing.

Thank you.

(updated 12:42 p.m. to add the names of other speakers)

The post My Remarks at the Harvard Vigil appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: September 14, 1901

9/14/1901: President Theodore Roosevelt is inaugurated. He appointed three members to the Supreme Court: Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Rufus Day, and William Henry Moody.

President Roosevelt's Appointees to the Supreme Court

President Roosevelt's Appointees to the Supreme CourtThe post Today in Supreme Court History: September 14, 1901 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Sunday Open Thread

[What's on your mind?]

The post Sunday Open Thread appeared first on Reason.com.

September 13, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: September 13, 1810

9/13/1810: Justice William Cushing died.

Justice William Cushing

Justice William CushingThe post Today in Supreme Court History: September 13, 1810 appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers