Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 32

September 19, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Would A Subsidy To Encourage Young Men and Women To Marry Be Constitutional?

[The government would offer a graduated subsidy, based on the age of the mother, to marry under the age of 30, with the goal of promoting natural child conception.]

One of Charlie Kirk's primary platforms was to encourage young men and women to get married early and have babies. The New York Times recounted one of his final messages:

At a young women's leadership conference this summer, Mr. Kirk warned women about waiting too long to get married. He argued that their chances of finding a life partner dropped if they were still single by the time they turned 30 — a message he reiterated on Fox News just days before his death.

"I would also tell young ladies: You can always go back to your career later," he said early last week, adding "that there is a window where you primarily should pursue marriage and having children. And that is a beautiful thing."

This proposal ginned up an idea. What if the government tried to subsidize men and women to get married young, with the goal of promoting natural child conception? The subsidy would not be available to older opposite-sex couples. The subsidy would also not be available to same-sex couples, regardless of their age, who could not naturally conceive a child within that marriage. Call it the Charlie Kirk Family Bonus.

If a woman under the age of 21 gets married to a man, there is a subsidy of $100; at the age of 22, a subsidy of $90; at the age of 23, $80; and so on. Once the wife reaches the age of 30, the subsidy drops to $0. The exact dollar amounts can be adjusted. The important point is that state is using subsidies to expressing its preference for natural child conception within a marriage.

Would such a regime be constitutional? Let's walk through the analysis.

First, this law would impose an age-based classification, which is generally reviewed with rational basis scrutiny (see Skrmetti). The fact that women over the age of thirty are ineligible for the subsidy would pass muster. The state can rationally conclude that older women are less likely to be able to conceive naturally. The law would easily satisfy this deferential standard. But that is not the end of the analysis.

Second, does this law impose a classification on the basis of sex? (I'll get to sexual orientation later.) Well in a sense, no. Married couples with one man and one woman are eligible. This law does not treat men different from women. Indeed, the couple would jointly receive the subsidy. It's true that people who do not get married would never receive the benefit. But there are many benefits--tax and otherwise--that are afforded to married couples. I think a law that favors married couples over unmarried people would be reviewed with rational basis scrutiny.

Still, for the sake of argument, I will presume this law imposes a sex classification. This sort of law is reviewed with intermediate scrutiny standard. Under VMI, would the state have an "exceedingly persuasive" justification to offer these graduated subsidies? I think it is fairly well established that as a woman gets older, her ability to reproduce decreases. Don't take my word for it. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists explains "A woman's peak reproductive years are between the late teens and late 20s. By age 30, fertility (the ability to get pregnant) starts to decline." (Men, by contrast, have higher fertility rates at older ages.)

A likely response is that women above the age of thirty can be aided in conception through various forms of IVF or fertility treatment. But here, the state is encouraging natural child conception, not the more expensive and less effective artificial means. The state may also conclude that IVF creates a false sense of security, whereby women can postpone conception till much later, only to find the process is difficult or unsuccessful. I think the state could also reject IVF from a moral perspective, in that it necessarily entails the destruction of many fertilized embryos. Certainly under Dobbs, the state can make that judgment. Couples can also adopt, but the state may determine that the primary interest is in promoting new lives.

Is this law promoting an important interest? The state could cite the crisis of underpopulation, and argue that it needs to promote conception to sustain the social fabric and economy of the polity.

What about the substantial relationship? Here, there is a very close relationship between the means (young couples marrying) and the ends (natural conception). Not all young couples will be able to have children, for a host of reasons. But encouraging opposite-sex marriage is the traditional means of encouraging responsible procreation. I think this graduated subsidy regime would pass muster under intermediate scrutiny.

Third, does this law impose a classification on the basis of sexual orientation? On its face, the answer is no. The law doesn't purport to define what marriage is or say anything at all about homosexuality. Rather, the law applies to a man and a woman who chose to get married by a certain age. Nothing stops a gay man from marrying a woman, and nothing stops a lesbian from marrying a man. This sort of arrangement happened throughout much of history. But I'll resume for the sake of argument that this law imposes a classification on the basis of sexual orientation. Would such a classification be reviewed under a rational basis or an intermediate scrutiny standard? Neither Obergefell nor Lawrence settled this issue. And I'm not sure it matters. I think this law survives scrutiny under the VMI test as described above.

Fourth, what about the substantive due process analysis from Obergefell? This law would not violate the square holding from Obergefell. Same-sex couples would still receive marriage licenses. But Obergefell seems to have gone further:

There is no difference between same- and opposite-sex couples with respect to this principle. Yet by virtue of their exclusion from that institution, same-sex couples are denied the constellation of benefits that the States have linked to marriage.

Pavan v. Smith (2017) ruled that the state must issue a birth certificate with the name of the mother's wife, just as the state would list the name of the mother's husband. People forget that Pavan was decided on (gasp!) the shadow docket through a summary reversal. Justice Gorsuch, Thomas, and Alito dissented here. I suspect this case might come out differently today.

Would the baby bonus be within the "constellation of benefits" of marriage? Yes and no. Only some married couples can receive it. The subsidy is only available to opposite-sex couples, but more precisely, the subsidy is only available to young opposite-sex couples. And the state has a fairly weighty interest to limit the availability of the subsidy. Women in opposite-sex marriages above the age of thirty are categorically ineligible for the subsidy. In this regard, gay couples are not singled out for disfavored treatment. By contrast, in Pavan, listing a name on a birth certificate has no consequences, beyond the recognition of a same-sex marriage. And in Windsor, all gay couples were denied the tax benefits. Windsor rejected "moral disapproval" as a justification for DOMA, but that decision did not address the state's interest in promoting natural child conception.

Wouldn't the baby bonus "demean" or deny the "dignity" of same-sex couples who are not eligible? Again, the law also does not apply to women over the age of thirty, writ large. This law is not premised on "moral disapproval" of gay couples, but instead, is designed as a way to promote natural conception within marriage.

Chief Justice Roberts stated the issue plainly in his Obergefell dissent:

The premises supporting this concept of marriage are so fundamental that they rarely require articulation. The human race must procreate to survive. Procreation occurs through sexual relations between a man and a woman. When sexual relations result in the conception of a child, that child's prospects are generally better if the mother and father stay together rather than going their separate ways. Therefore, for the good of children and society, sexual relations that can lead to procreation should occur only between a man and a woman committed to a lasting bond.

Wait a minute, you might ask. Didn't the Obergefell majority reject the "procreation" justification for traditional marriage laws?

People often ask me whether Obergefell would be overruled. I think the answer is no, for the stare decisis reasons that Justice Alito identified in Dobbs. But I am skeptical the Court would extend Obergefell to new contexts. This sort of conception-subsidy would be such a new context.

This post is mostly a thought experiment. I'm curious to see what others think.

The post Would A Subsidy To Encourage Young Men and Women To Marry Be Constitutional? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Video of Education Law and Policy Panel on "Federal Efforts to Combat Antisemitism: Restoring Campus Civil Rights or Infringing Academic Freedom?"

[I was one of the participants.]

NA

NA Below is a video of the panel on "Federal Efforts to Combat Antisemitism: Restoring Campus Civil Rights or Infringing Academic Freedom?" from the recent Education Law and Policy Conference, co-sponsored by the Federalist Society and the Defense of Freedom Institute. I was one of the participants. The others were Tyler Coward (Lead Counsel, Government Affairs, Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)), Ken Marcus (Chairman & Founder, Brandeis Center), and Sarah Perry (Vice President & Legal Fellow, Defending Education). Carlos Muniz, Chief Justice of the Florida Supreme Court, moderated.

Not surprisingly, Tyler Coward and I were much more critical of the the Trump Administration's policies than Perry and Marcus. In my view, much of what is being done under the pretext of combatting campus anti-Semitism is actually undermining freedom of speech and academic freedom, and also illegally seeking federal control over state and private universities. But there were more areas of agreement. For example, we all agreed that the federal government cannot properly seek control over university curricula (Perry even said the Trump Administration's efforts to do so at Harvard gave her "apoplexy") and that campus protests that devolve into violence and disruption must be banned, and are subject to punishment. Though in my view, not all of the latter qualify as anti-Semitic, and some are properly addressed by state and local law, rather than federal enforcement.

We also all agree that Jews are among the groups protected by Title VI (the federal law banning racial and "national origin" discrimination in educational institutions receiving federal funding). This position was once controversial, but has gained widespread cross-ideological acceptance more recently. On the other hand, Marcus and I differed over whether the very broad IHRA definition of anti-Semitism is the right one to apply in this context. In my view- as applied to anti-discrimination law, that definition creates dangers similar to those of overbroad definitions of racism and sexism, traditionally decried by conservatives and libertarians.

I have previously written about campus anti-Israel protests here and about far-left versions of anti-Semitism here (discussing, among other things, how they differ from right-wing/nationalist anti-Semitism).

The post Video of Education Law and Policy Panel on "Federal Efforts to Combat Antisemitism: Restoring Campus Civil Rights or Infringing Academic Freedom?" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Judge Strikes Trump's Complaint in Libel Lawsuit Against N.Y. Times

["The complaint continues ... with much more, persistently alleged in abundant, florid, and enervating detail." "[A] complaint is not a public forum for vituperation and invective—not a protected platform to rage against an adversary. A complaint is not a megaphone for public relations or a podium for a passionate oration at a political rally or the functional equivalent of the Hyde Park Speakers' Corner."]

From today's order by Judge Steven Merryday (M.D. Fla.) in Trump v. N.Y. Times Co.:

As every member of the bar of every federal court knows (or is presumed to know), Rule 8(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, requires that a complaint include "a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief." Rule 8(e)(1) helpfully adds that "[e]ach averment of a pleading shall be simple, concise, and direct." Some pleadings are necessarily longer than others. The difference likely depends on the number of parties and claims, the complexity of the governing facts, and the duration and scope of pertinent events. But both a shorter pleading and a longer pleading must comprise "simple, concise, and direct" allegations that offer a "short and plain statement of the claim." Rule 8 governs every pleading in a federal court, regardless of the amount in controversy, the identity of the parties, the skill or reputation of the counsel, the urgency or importance (real or imagined) of the dispute, or any public interest at issue in the dispute.

In this action, a prominent American citizen (perhaps the most prominent American citizen) alleges defamation by a prominent American newspaper publisher (perhaps the most prominent American newspaper publisher) and by several other corporate and natural persons. Alleging only two simple counts of defamation, the complaint consumes eighty-five pages. Count I appears on page eighty, and Count II appears on page eighty-three. Pages one through seventy-nine, plus part of page eighty, present allegations common to both counts and to all defendants. Each count alleges a claim against each defendant and, apparently, each claim seeks the same remedy against each defendant.

Even under the most generous and lenient application of Rule 8, the complaint is decidedly improper and impermissible. The pleader initially alleges an electoral victory by President Trump "in historic fashion"—by "trouncing" the opponent—and alludes to "persistent election interference from the legacy media, led most notoriously by the New York Times." The pleader alludes to "the halcyon days" of the newspaper but complains that the newspaper has become a "fullthroated mouthpiece of the Democrat party," which allegedly resulted in the "deranged endorsement" of President Trump's principal opponent in the most recent presidential election. The reader of the complaint must labor through allegations, such as "a new journalistic low for the hopelessly compromised and tarnished 'Gray Lady.'" The reader must endure an allegation of "the desperate need to defame with a partisan spear rather than report with an authentic looking glass" and an allegation that "the false narrative about 'The Apprentice' was just the tip of Defendants' melting iceberg of falsehoods." Similarly, in one of many, often repetitive, and laudatory (toward President Trump) but superfluous allegations, the pleader states, "'The Apprentice' represented the cultural magnitude of President Trump's singular brilliance, which captured the [Z]eitgeist of our time."

The complaint continues with allegations in defense of President Trump's father and the acquisition of the Trumps' wealth; with a protracted list of the many properties owned, developed, or managed by The Trump Organization and a list of President Trump's many books; with a long account of the history of "The Apprentice"; with an extensive list of President Trump's "media appearances"; with a detailed account of other legal actions both by and against President Trump, including an account of the "Russia Collusion Hoax" and incidents of alleged "lawfare" against President Trump; and with much more, persistently alleged in abundant, florid, and enervating detail.

Even assuming that each allegation in the complaint is true (of course, that is for a jury to decide and is not pertinent here; this order suggests nothing about the truth of the allegations or the validity of the claims but addresses only the manner of the presentation of the allegations in the complaint); even assuming that at trial the plaintiff offers evidence supporting every allegation in the complaint and that the evidence is accepted by the jury as fact; and even assuming that after finally "melting" the defendants' alleged "iceberg of falsehoods" the plaintiff prevails for each reason alleged in the complaint—even assuming all of that—a complaint remains an improper and impermissible place for the tedious and burdensome aggregation of prospective evidence, for the rehearsal of tendentious arguments, or for the protracted recitation and explanation of legal authority putatively supporting the pleader's claim for relief. As every lawyer knows (or is presumed to know), a complaint is not a public forum for vituperation and invective—not a protected platform to rage against an adversary. A complaint is not a megaphone for public relations or a podium for a passionate oration at a political rally or the functional equivalent of the Hyde Park Speakers' Corner.

A complaint is a mechanism to fairly, precisely, directly, soberly, and economically inform the defendants—in a professionally constrained manner consistent with the dignity of the adversarial process in an Article III court of the United States—of the nature and content of the claims. A complaint is a short, plain, direct statement of allegations of fact sufficient to create a facially plausible claim for relief and sufficient to permit the formulation of an informed response. Although lawyers receive a modicum of expressive latitude in pleading the claim of a client, the complaint in this action extends far beyond the outer bound of that latitude.

This complaint stands unmistakably and inexcusably athwart the requirements of Rule 8. This action will begin, will continue, and will end in accord with the rules of procedure and in a professional and dignified manner. The complaint is STRUCK with leave to amend within twenty-eight days. The amended complaint must not exceed forty pages, excluding only the caption, the signature, and any attachment.

You can read the now-struck Complaint here. To be fair, the Complaint is a specimen of a broader phenomenon I've seen in other cases—but it is indeed an unusually aggravated specimen. These sorts of complaints, in criminal and civil cases, are sometimes called "speaking complaints," and have both defenders and opponents; this one, though, speaks a lot, and about many things that don't seem quite relevant to the matter.

The post Judge Strikes Trump's Complaint in Libel Lawsuit Against N.Y. Times appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Sealing and Malawi

(Map from the CIA Factbook.)

(Map from the CIA Factbook.)

From Republic of Malawi v. Columbia Gem House, decided Wednesday by Judge David Estudillo (W.D. Wash.):

On April 11, 2025, Plaintiff filed an application to conduct discovery for use in contemplated foreign criminal and civil proceedings pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1782. Shortly thereafter, the Clerk's Office sealed this case, based upon guidance provided to Clerk's office employees that cases of this nature should generally be opened under seal. On May 23, 2025, the Court granted Plaintiff's application….

Plaintiff argues the Court should unseal this case in its entirety because there is no compelling reason to maintain the seal. Plaintiff contends there is no confidential information in any of the Court filings and argues the presumption of access to judicial records should therefore prevail….

In general, "compelling reasons" sufficient to outweigh the public's interest in disclosure and justify sealing court records exist when such "court files might have become a vehicle for improper purposes," such as the use of records to gratify private spite, promote public scandal, circulate libelous statements, or release trade secrets. However, "[t]he mere fact that the production of records may lead to a litigant's embarrassment, incrimination, or exposure to further litigation will not, without more, compel the court to seal its records."

Here, Defendants argue Plaintiff will "use and misconstrue the Court's records and orders to perpetuate an ongoing false scandal" to advance the re-election prospects of politicians in Malawi. Defendants contend the scandal allegedly perpetuated by the Malawian government threatens the future of their business and the livelihood of their employees. Defendants argue the government of Malawi has been using false accusations against them "to whip up public scandal" for years, and have recently resurrected these allegations in the run up to Malawi's 2025 presidential election. Defendants argue Plaintiff has already used and misconstrued the Court's rulings for political purposes, citing an article published on a Malawian news website that quotes from the Court's sealed order granting Plaintiff's application to conduct discovery pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1782. {Plaintiff and Plaintiff's counsel both deny sharing the Court's order with any third parties.}

The Court finds Defendants have not met their burden with respect to maintaining the case under seal. The Court notes this case was sealed pursuant to general guidance issued to the Clerk's Office, not because of any specific, compelling reasons that would justify sealing. In addition, while parties in Malawi may attempt to misconstrue aspects of the Court's rulings, those parties are capable of publishing derogatory information about Defendants with or without access to Court documents. As Defendants assert, they have been subject to a long running "shakedown" by parties in Malawi that began in 2011 and led to the publication of a report in 2014 alleging Defendants plundered hundreds of billions of dollars of Malawi's mineral wealth. Moreover, by having access to the positions taken by each party and the Court's ultimate rulings, the public will have accurate information about findings and conclusions made in this case.

Some backstory from the now-unsealed order granting discovery (though recall that these are all just allegations by the Malawi government):

This matter arises out of an investigation initiated by Thabo Chakaka-Nyirenda, the Attorney General of Malawi, into an alleged scheme to defraud Malawi out of billions of dollars in royalties and taxes related to the mining of rare rubies and sapphires at the Chimwadzulu mine, which is located on Chimwadzulu Hill in the Ntcheu District of Malawi. Malawi alleges Nyala Mines Limited ("Nyala Mines"), which held a license from Malawi's government granting it the exclusive right to mine rubies and sapphires from the Chimwadzulu mine, engaged in a long-running criminal conspiracy to underreport its gemstone exports and wholesale earnings to reduce the amount owed to Malawi under the relevant license and royalty agreements.

Malawi seeks discovery from Columbia Gem House, Inc. …, a supplier and wholesaler of exotic gemstones with offices in Vancouver, Washington, which Malawi claims will aid its investigation. Malawi contends Columbia Gem has an exclusive agreement with Nyala Mines to sort, cut, and market sapphires and rubies from the Chimwadzulu mine. Malawi also seeks to ascertain whether Columbia Gem is, or was, the parent company of Nyala Mines. Malawi alleges Columbia Gem has knowledge and documents in its possession, custody, or control that are relevant to the investigation….

You can also read the motion to unseal, Columbia Gem House's opposition, and the reply; the latter two documents also have the parties' perspectives on the various allegations behind the Malawi AG's actions.

Back in 2002, I ran a contest to find the countries least referenced in U.S. news sources, and Malawi won the prize in the over 1 million population category, and in the hits per million category (86 hits in 5 years, for a population of 10.7 million at the time). I'm happy to do my part to change that.

Amiad Moshe Kushner and MarcAnthony Bonanno (Seiden Law LLP) and Keith David Petrak (Byrnes Keller Cromwell LLP) represent Malawi.

The post Sealing and Malawi appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The First Liberty Institute Is A Defender Of The Jewish People

[Unfortunately, FLI is being lumped in with another group that made an unfair and uninformed attack on Rebecca Taibleson's rabbi. ]

The fallout from Rebecca Taibleson's nomination continues. I was very critical of an attack from a particular conservative group which focused on the rabbi that married Taibleson. That attack was distinct from a letter signed by about fifty other conservative groups, including the First Liberty Institute (FLI). Unfortunately, FLI is being lumped in with the organization that focused on Rebecca's rabbi, and it has been suggested that FLI favors a religious test, and is hostile to Jewish people.

I can speak from experience that such a charge is absolutely unfounded. I have worked with FLI for more than a decade. In 2016, a group of poultry activists sued a Chabad Rabbi in California on the eve of the Jewish New Year. The Rabbi, preoccupied with other tasks, did not respond to the suit. A federal judge issued an Ex Parte TRO that prohibited the Rabbi from performing an important ritual that involves chickens. I found out about the case, and stayed up all night preparing an amicus brief, arguing that the poultry group could not establish diversity jurisdiction because the amount in controversy was less than $75,000. At the same time, First Liberty Institute swooped in and prepared a representation for the Rabbi in about twenty-four hours. With little notice, they presented oral arguments over the phone. When no one else was willing to defend this Rabbi, FLI stepped up to the plate. I wrote about the case in the Los Angeles Times.

More recently, a group of Jewish people in a Houston neighborhood began holding services in a home. Over time, more and more people started to attend this small, friendly minyan. It was called Heimish, which means homey. Some neighbors began to complain about the noise, and the City of Houston threatened to take a zoning enforcement action. FLI once again stepped up to the plate, and the City of Houston backed down.

Just last month, FLI secured a victory for a Jewish student at (of all places) the University of Wisconsin. The student requested on campus housing in walking distance to a synagogue, so she could walk to Shabbat services. After receiving a letter from FLI, the University acquiesced. There are many more cases: a property dispute for a Chabad in Long Island, harassment of a Rabbi in Boca Raton, a Jewish prayer group in Hawaii, a Rabbi in Beverly Hills, and many more.

Every year I speak at First Liberty's annual conference, which usually runs over the weekend. For the past few years, I have brought shabbat candles, challah, and grape juice so my family can celebrate Shabbat. This past year, the FLI staff volunteered to coordinate everything, and brought all of the things needed to celebrate. It was such a thoughtful gesture, for which I was grateful. Indeed, my kids led a mini shabbat service for many people in attendance, who had never had that experience. It was beautiful.

I could go on.

Whenever conservatives oppose a Republican-appointed judge, we have the equivalent of a family feud. It's not ideal, but sometimes these issues need to be ventilated publicly, as Senator Cruz explained. But I think we need to be careful about unfairly assigning blame to those groups that speak out.

The post The First Liberty Institute Is A Defender Of The Jewish People appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Court Upholds Florida School District's June 2020 Decision to Cancel Food Supply Contract with Farm Whose Owner Viewed as Covid as Hoax

["[T]he evidence shows that the school system's interests in food safety were the reasons for its decision to break ties with Oakes Farms—not its bare disagreement with [owner's] political views."]

From Wednesday's decision in Oakes Farms Food & Distribution Servs., LLC v. Adkins, decided by Eleventh Circuit Judge Britt Grant, joined by Judges Jill Pryor and Stanley Marcus:

In spring 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic turned the world upside down. Alfie Oakes, the owner of a Florida farm and agriculture business, disagreed with the government's response—strongly—and he was not afraid to say so. He took to Facebook, where he described the virus as a "hoax" perpetrated by "corrupt world powers and their brainwashing arms of the media" to dupe "lemmings" with "COVID programming." Oakes also shared his opinions on other topics—the Black Lives Matter movement and George Floyd, to name a few.

Oakes Farms had been selling fruits and vegetables to a local school district for years, and the school board grew worried that Oakes's views about the pandemic betrayed a lax approach to food safety during a time when not much was known about Covid-19's transmissibility. Worries deepened after requests for the farm's pandemic protocols turned up nearly nothing, so the superintendent terminated the produce contract. Both Oakes and his farm sued, saying that the contract termination violated Oakes's First Amendment rights.

The district court saw things differently, and granted summary judgment to the school district. We agree. Although the owner was speaking as a citizen on important matters of public concern, the evidence shows that the school system's interests in food safety were the reasons for its decision to break ties with Oakes Farms—not its bare disagreement with his political views. Had there been evidence that the real motivation was punishing Oakes for these views, whether about Covid-19 or racial topics, it would be a different matter. But here, the evidence is not reasonably in dispute….

The First Amendment's prohibition on any law "abridging the freedom of speech" leaves room for the government's interests when it acts as an employer or marketplace consumer, rather than as a sovereign. In those contexts, to protect workplace efficiency and related interests, the government retains the ability to restrict its employees' speech well beyond the limitations it could place on private citizens. Otherwise, even backtalk about the most trivial internal matters could open a constitutional debate, potentially grinding essential government services to a halt.

Of course, that does not mean government employees have no free speech rights at all. Our cases have built a framework for vindicating public employees' First Amendment rights while still respecting the government's legitimate workplace interests. Under the employee-speech doctrine, we work through three questions to assess whether the government has unconstitutionally retaliated against an employee's speech. First, did the employee speak "as a citizen on a matter of public concern"? Second, did the employee's right to speak outweigh the government's interest "in effective and efficient fulfillment of its responsibilities"? Third, did the speech play "a substantial part in the adverse employment action"? …

Here, the speaker was not a government employee. He was the owner of a business that contracted with the government. But the Supreme Court has already confirmed that … the public employee speech cases … apply to independent contractors. "Independent government contractors are similar in most relevant respects to government employees, although both the speaker's and the government's interests are typically—though not always—somewhat less strong in the independent contractor case." …

Oakes clears the first step of the … test. When posting about controversial political topics on his personal Facebook page, on a Saturday no less, he was speaking as a citizen on matters of public concern. We turn, then, to the heart of the government-contractor speech analysis: balancing the school district's legitimate interests against Oakes's right to free speech….

Because courts are not human resources departments, we engage in a "deferential weighing of the government's legitimate interests" to avoid constitutionalizing every workplace grievance. Under that standard, we cannot say that the school district's interests here were insignificant. After all, the owner and namesake of Oakes Farms not only believed, but also felt compelled to publicly declare, that the Covid-19 pandemic was a conspiracy by "corrupt world powers" to bring down disfavored political figures, that only "lemmings" who were "controlled by deceit and fear" could be concerned about it, and that safety precautions taken in response were bringing the nation's economy "to ruins."

Superintendent Adkins had more than a thin basis for alarm. The combination of all those statements is highly probative of, as Adkins himself put it, "not taking this seriously." Add to that the less-than-reassuring responses following the school district's efforts to verify the adequacy of Covid safety protocols at Oakes Farms, and we cannot discount the weight of the district's interest in ensuring food safety for its students.

Adkins always—both publicly and privately—grounded his decision to cancel the contract on his concern for food safety. He testified that "[s]taff brought to [him] a concern about the lack of protocols that Oakes Farms had in terms of how it handled its food." That those worries blossomed into an investigation of Oakes Farms' antivirus protocols underscores their grounding in food safety. As Adkins explained, "Oakes Farms' perceived lack of concern regarding the easy transmission of COVID-19 and Mr. Oakes' belief that COVID-19 is not real" threatened "the health, safety, and welfare of the children" at Lee County schools. And he said that knowing the decisions he made "impact[ed] the lives of our students" and "their families," he needed "to err on the side of safety, particularly during a health crisis pandemic." We should be clear that this testimony supports the argument that Adkins's concern was food safety—not disagreement with Oakes's views about Covid.

To be sure, it appears obvious that Adkins did disagree with Oakes about Covid-19. But that difference in viewpoint was not the basis for his actions—a concrete concern about food safety was. That Oakes's speech alerted Adkins to the concern does not mean that he was being punished for his viewpoint, just like firing an employee after he confesses to embezzlement is not the same as punishing him for his different perspective on personal use of company funds.

There are fair questions about the strength of the district's interests because of what we know today about how Covid-19 spreads and its relationship to food safety. And Oakes Farms points to an FDA statement printed on the Marjon Specialty Foods protocols it handed over to school officials: "Currently there is no evidence of food or food packaging being associated with transmission of COVID-19." But the uncertainty and fear that were almost omnipresent during June 2020 make a demand for perfect scientific precision unfair to the school district. And poking holes in its choices with the benefit of hindsight is far from the deferential posture we assume when reviewing the government's interests.

That is not to say that any government fear justifies terminating a contract based on a contractor's speech. If Oakes owned a company that provided the school district with software, his views on Covid-19 would likely have been irrelevant. It would have been much harder for the district to show that it canceled the contract for any reason besides disagreeing with his viewpoint on Covid (or any of the other issues). But here, the tight connection between produce and physical health gave the government's interests significant heft.

No doubt, Alfie Oakes's interests were also substantial. He was speaking on matters of great public concern and widespread discussion. He posted on his personal Facebook page on a Saturday, and the speech drew no direct connection to his contract with the district. But ultimately, when viewed with the required deference, the school board's interests in ensuring the safety of food served to its students outweighed Oakes's right to free expression….

For more, including the court's explanation why there wasn't enough evidence to support Oakes' theory that "[t]he talk of food safety was a pretext for the district's real concerns, he says—Oakes's statements disparaging Black Lives Matter and George Floyd," see the full opinion. The court, however, added:

But let us be clear—if there were evidence of retaliation against Oakes because of his views on Black Lives Matter or George Floyd, that would be completely out of bounds. And the district court was incorrect to suggest the contrary. For example, it concluded that "Mr. Oakes's speech contradicted the messages of inclusion and anti-racism that the School District was promoting to its students," a concern that is plainly irrelevant to his company's food-services role. And the court also mused that "[p]rotests, and even the threat of protests, weigh in favor of the government's legitimate interest in avoiding disruption."

This kind of heckler's veto concern is not enough to survive First Amendment scrutiny. "Speech cannot be … punished or banned[ ] simply because it might offend a hostile mob." But the school district never advanced these interests and Oakes Farms has not shown that the decisionmakers were motivated by them, so we need not consider them here….

For more on how the heckler's veto plays out in at least some other government-as-employer cases, see this post.

Christopher Dale Donovan (Donovan Appellate Law, PLLC), James Donald Fox (Roetzel & Andress, LPA), Philip Fairman and Steven Sundook (Vernis & Bowling of Southwest Florida, PA), and William Talley (Cruser Mitchell Novitz Sanchez Gaston & Zimet, LLP) represent defendants.

The post Court Upholds Florida School District's June 2020 Decision to Cancel Food Supply Contract with Farm Whose Owner Viewed as Covid as Hoax appeared first on Reason.com.

[Barry Strauss] A Night in Jerusalem

[History and a city at war.]

On a late summer night Jerusalem casts a magic spell. The first day of autumn is less than a week away but the daytime temperature is close to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and the sun is relentless. Then the cool breeze of evening comes and it's like the soft touch of a cat's whiskers.

Jerusalem is a city that needs to be seen on three levels. The street is a cacophony of cars of course but also the thrust and parry of conversation in the cafes on Bethlehem Road. Viewed from above, from the YMCA tower, say, an elegant art deco structure designed by the same architect who built New York's Empire State Building, the city looks like a forest of stone. The walls of the Old City, the domes and spires of church, mosque, and synagogue, the graves of the Mount of Olives, the ubiquitous construction cranes ("Israel's national bird," as the joke goes) and the slabs of limestone that line the buildings they help to erect, the separation wall between Israel and the Palestinian territories.

But as a historian, I am drawn to what lies underneath Jerusalem. It is not difficult to find mementoes of the Great Revolt of 66-70 in which the Romans laid siege to the city, captured it and destroyed the whole town, including the Second Temple. I write about that revolt, and two other Jewish revolts against Rome, in my new book, Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World's Mightiest Empire (Simon & Schuster, 2025). The death throes of Jerusalem come alive under the streets of the Old City.

You can visit, for example, the ruins of the mansions of the wealthy, which in their heyday looked across a valley at the Temple Mount. The splendor of these dwellings still survives in the fragments of mosaics, frescoes, and stucco. The owners were pious Jews, as shown by the presence of ritual baths and stone vessels. They were probably priests, maybe including the High Priest. You can also see traces of the fire that brought the buildings down.

Not far away is the so-called Pilgrim's Road, which led from the Pool of Siloam through the City of David to the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. It's a path that was followed by people coming to Jerusalem for one of the three annual pilgrimage festivals. Jesus might have trod this road.

Among many striking finds, the excavators discovered "blackened seeds" and "rich botanical evidence" that can be dated to the time of the revolt. These may be precious material evidence of what the historian Josephus, a contemporary, describes in his classic book, The Jewish War. That is, as Josephus reports, the rebels themselves burned the city's grain supply, perhaps in a series of inter-factional disputes—a counter-productive and even suicidal gesture to be sure.

How, I wonder, did the people of Jerusalem go about their business during the four years of the revolt? Some panicked, some fled, but most of them stayed as if nothing was happening, as if the Roman army wasn't prowling the country. Why? Maybe the answer lies in what I saw in Jerusalem one recent evening.

I saw the streets full of shoppers. Arabs and Jews crowded the upscale boutiques of the Mamilla Mall. Left in ruins by the fighting in Jerusalem in Israel's War of Independence, between 1949 and 1967, the area was No-Man's-Land between Israel and Jordan. Now it is Jerusalem's toniest emporium.

I saw two groups of street musicians. One group was boisterous and joyful. A crowd of people followed it clapping and dancing through the mall toward the Jaffa Gate of the Old City. The other group, seated in a circle outside the Gate, sang softly in the night air.

That evening, the war in Gaza City was about to heat up, and everyone knew it. Even readers of goodwill might wonder how people at war—and the mall included soldiers in uniform—might go out for a night on the town. Yet there is nothing new about wartime societies enjoying precious moments of peace. As far back as the Trojan War, soldiers partied before going out to battle.

Not that Israelis aren't hurting after nearly two years of war. Most people are tired, some are traumatized, some fear for the future in an ever-more hostile region and world, and many are angry at their government (what else is new?). Yellow ribbons for the hostages are tied to the door handles of many cars, and posters along the streets recall those still in captivity or whose bodies have not been returned. Other posters show the youthful faces of soldiers who have died in battle. Political divisions in Israel continue as usual; I can't count the number of protests that I saw.

And yet, for all the pain and division, the indefatigable Jewish spirit, stubborn, resilient, and optimistic, prevails.

The morning after I visited Mamilla, the valleys of Jerusalem were full of fog. You could feel that the seasons changing. Both the start of autumn and the Jewish New Year are now just days away. May it be a happy and healthy year, one of a new beginning for Gaza, the safe return of the hostages and, above all, a year of peace for Israel and the whole region.

The post A Night in Jerusalem appeared first on Reason.com.

September 18, 2025

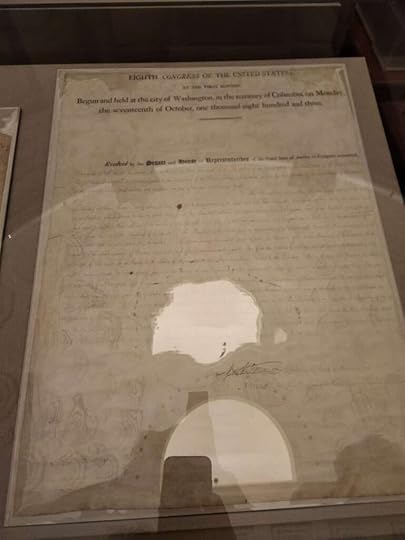

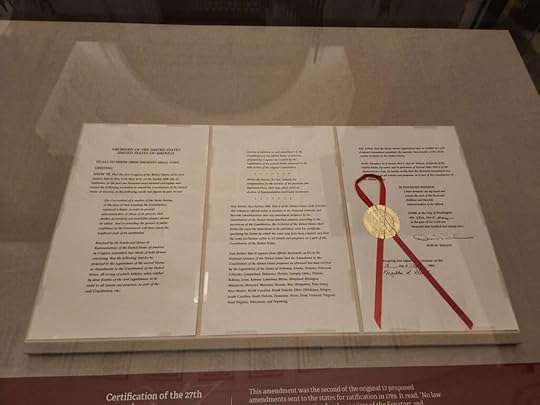

[Josh Blackman] See The Entire Constitution At The National Archives

[The Constitution, the "Fifth Page," and all 27 Amendments are on display.]

I have visited the Rotunda at the National Archives many times. On permanent display are the Declaration of Independence, the four pages of the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. At this point, the Declaration is so faded, it is nearly impossible to read. Same for the Bill of Rights. Thankfully, the Constitution was better preserved. Every time I walk into the room, I am overcome by a sense of awe and wonder. I devote my life to teaching these documents, but it is a very different sensation to see them in person.

For the next month, the National Archives has put together a very special presentation: the "fifth page" of the Constitution is on display, along with all twenty-seven amendments. Today, I visited the Archives, and thoroughly enjoyed the new exhibit. The photographs, alas, are not good. The lighting creates a glare on the glass cases, which made them even more difficult to see.

The "fifth page" provided instructions to the states of how to ratify the Constitution. I labored about whether to include this text in the Heritage Guide to the Constitution. I ultimately decided not to, as it was not part of the ratified document, even though it was signed by George Washington, the President of the Convention.

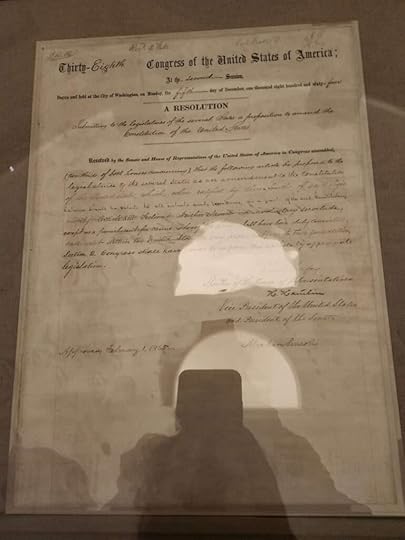

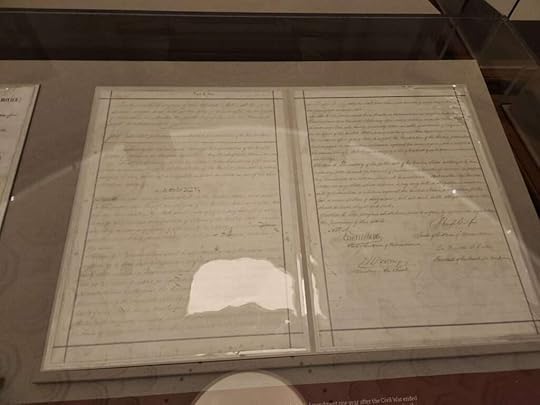

I was struck by how large the proposed Eleventh Amendment was. The piece of parchment was nearly the size of the Bill of Rights.

The Twelfth Amendment had a formatted, printed header at the top. It was also a large piece of parchment.

The Thirteenth Amendment was written in very tight cursive, and took up barely half the page. It is noteworthy that President Lincoln signed the Thirteenth Amendment, even though Article V does not provide a role for the President in the amendment process.

The Fourteenth Amendment was not written on any sort of form, but was written in script on lined-paper.

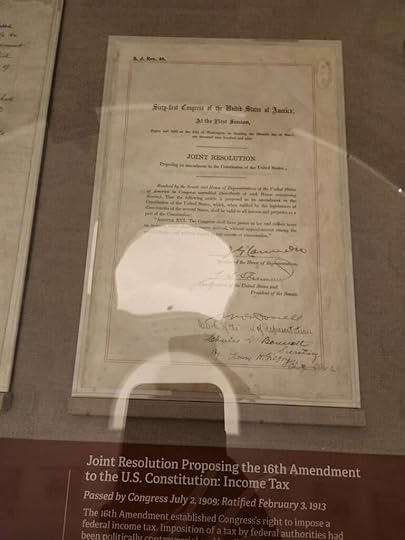

The Sixteenth Amendment was the first amendment that was typeset. Much less dramatic.

I don't think I had ever seen the Twenty-Seventh Amendment before. It includes a fascinating narrative of how the amendment was originally introduced in 1789, but not ratified until 1992.

Visit the Archives soon!

The post See The Entire Constitution At The National Archives appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Some Things We Learn From Justice Barrett's New Book

[Chapter 4 on "Deciding a case" offers some insights that we didn't know, or at least didn't know for certain.]

I am making my way through Justice Barrett's new book, Listening to the Law. I'll put the praise up front. This is a very well-written book. It is tight, well-organized, and enjoyable. I think a non-lawyer could pick up this book and learn a lot about the Supreme Court. It is also clear to me that Justice Barrett wrote this book herself, and enjoyed writing it. She has a very distinct writing style that comes through on every page. There was no ghost-writer used here.

In due course, I will offer some more in-depth comments, but here, I'd like to highlight some of the new things we learn from the book. In particular, I'll focus on Chapter 4, where she walks through her process of deciding cases.

First, Barrett explains her process before oral arguments. Barrett will read the brief from the Petitioner, Respondent, and when available, the Solicitor General. Barrett is very clear that she does not read amicus briefs "at the outset of [her] preparation." At a recent confirmation hearing, a Senator worried about the dark money that funds amicus briefs. I think this concern is misplaced. Barrett said she will "read some amicus briefs, like those filed by state governments." But she finds less helpful briefs that "dwell on policy arguments." I would know nothing about such briefs!

Second, after reading the briefs, she will read the clerk's bench memo. By contrast, when she served on the Seventh Circuit, she would read the bench memo before the briefs. Why the change? Barrett writes, "At the Supreme Court, by contrast, the question presented is crystallized, and the quality of briefing is almost always superb." Barrett wants to form her own "preliminary views" before reading the recommendation.

Third, Barrett explains that the clerk authoring the memo chats with her co-clerks, as well as the clerks in the other eight chambers:

Though the memo is the clerk's own work product, she doesn't prepare it in a vacuum. In the course of working through the arguments, she has conversations with her co-clerks, as well as with the clerks working on the same case in the other eight chambers.

I don't think this practice has ever been publicly confirmed by a Justice. I find it fascinating that all of the clerks will chat about the case. I suspected this type of shuttle diplomacy happens after a case is happened, but it apparently happens before as well.

Fourth, after reviewing the clerk's memo, Barrett will write up her own analysis. In some cases, Barrett has a strong sense of where she will lean. in other cases, she does not.

After some back-and-forth with the assigned clerk, I sit down at a computer, do additional research if necessary, and write up my own analysis. In some cases, I'm practically certain of my view, particularly if it's an issue that I've dealt with before. In others, I have a preliminary sense, stronger in some cases than others. And there is a small subset of cases in which a first reading of the briefs leaves me evenly divided. Oral argument is most likely to move me in the latter two situations, but I'm always open to hearing what the lawyers say in the courtroom.

Fifth, Barrett offers a detailed analysis of oral argument. Barrett uses two different terms for the phases of OA: "open floor" and "cleanup round." I usually refer to the latter as "seriatim" but I can see why "cleanup" makes sense. Barrett will always re-listen to an argument if she is assigned the opinion. Why does Barrett not read the transcript? "The answer is that audio allows me to multitask, so it is background while I cook or run errands."

Barrett also relates how her parents listened to oral argument in Trump v. Anderson. Of all the cases they attended, it is curious Barrett mentioned this case.

Sixth, Barrett discusses her process after oral argument. She hashes the case out with all four of her clerks. Then, she decides how she will vote:

After all of this input—the briefs, the research, oral argument, conversations with clerks—it's time to decide how I'll vote and what I'll say at conference. I return to the notes that I wrote before argument and edit them as needed based on subsequent developments.

Barrett offers a useful test case to check for potential biases:

To counteract my biases, I substitute a different policy into the legal frame. For example, if the question is whether a statute allows an administrative agency to adopt a regulation that I dislike, I imagine the agency using a statute with the same language to adopt a regulation that I like. If a free speech claim involves a message with which I sympathize, I plug in a message I disfavor. Not every case is susceptible to this exercise, but every case is susceptible to this question: Can I look the losing party and any dissenting colleagues in the eye and honestly defend my conclusion as my best understanding of what the law requires?

I think this analysis usually winds up with "no one has standing."

Barrett relays that Justice Scalia said it took him longer to decide cases earlier in his career. Barrett writes, "I have years to go before I'm at that stage, so at this point, preparing for my conference vote consumes a considerable amount of time." I can sense that Barrett's lengthy deliberations may stand in contrast with how her other colleagues decide cases, even those with shorter tenures.

Seventh, we get a peak inside voting at conference. Barrett relates the dynamics where the Chief Justice votes first:

The justices speak and vote in order of seniority, with the chief justice starting the process. This is different from the practice at the Seventh Circuit, where the most junior judge talked and voted first. I generally like the system at the Court, because it gives me the opportunity to consider and respond to what others have said. The flip side is that it can be frustrating to speak toward the end, because it limits my opportunity to persuade the seven justices who have already voted. (As a junior justice, Justice John Paul Stevens disliked the system for this very reason and advocated for a change of order.) Still, colleagues do listen to those later in line and sometimes adjust their positions after the first round of voting is complete. Conference discussions are respectful and calm, and we do not interrupt one another.

One of my most egregious errors came in my first book, Unprecedented. I was trying to imagine what the conference was like after NFIB v. Sebelius. I didn't know if Roberts would have voted first or last. I asked a friend who knew a lot about the Court, and he said Roberts voted last. And that is how I set up the conference. That error still eats at me twelve year later. Now Barrett has publicly confirmed the voting process.

Eight, Barrett discusses the process of opinion assignments. Here, she relates things that I do not think have ever been confirmed. The assignments are not actually made at the conference. Rather, they come later in an assignment list. The Justices do not know who will write what until the list is circulated on Friday afternoons. Barrett also alludes to how the Chief Justice assigns opinions. Keep in mind that Roberts is in the majority about 95% of the time. It is very rare for anyone else to assign a majority opinion. So when Barrett writes that Roberts "works with other assigning Justices," she is basically saying Roberts works by himself.

A memo containing opinion assignments circulates at the end of the two-week argument session. At that point, based on the justices' votes across the cases, it is clear how many majority and dissenting opinions will be written, so the chief justice, working with other assigning justices, attempts to equitably distribute the work. My clerks wait eagerly for the assignment list to come around on Friday afternoons, to see both what I get and whether their predictions panned out.

I think the emphasis is on "attempts." And later Barrett reveals what we all know--the Chief Justice keeps the most important cases for himself.

Assignments in the most complex and high-profile cases typically go to the more senior justices, and it is the norm for the assigning justice to keep the highest-profile assignment for herself. For example, in the 2022 Term, cases involving affirmative action and voting rights were among the biggest; Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinions in all of them. [FN34]

[FN34] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 600 U.S. 181 (2023); Moore v. Harper, 600 U.S. 1 (2023); Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S. 1 (2023).

Preach, ACB. We all know this to be true. The opinions are not actually split equitably.

I would favor a reform: the Chief Justice position rotates each month. The Court is in session nine months out of the year, and there are nine Justices. The Justices could draw a number from a hat, and each month there would be a new Chief. That Chief would president over oral argument, preside at the conference, assign opinions, and chair any administrative committees. May and June, which lack oral arguments, would be less desirable, but each term brings a new luck of the draw. I think the Chief Justice exercises far too much power. That much power goes to a man's head. That position needs to be weakened.

I think this reform could be achieved by internal Court rule. I'm not sure Congress could legislate on this matter. Moreover, this plan goes against my interests. On average, I would prefer an assignment from Chief Justice Roberts than from Justice Jackson. But for one month of the year, Justice Jackson, the most junior Justice, would be able to preside, and assign majority opinions. This sort of dynamic, I think, would actually improve the functioning of the Court. Let each member take ownership in the Court. Then again, there is a much easier way for John Roberts to stop assigning opinions, but I repeat myself.

Ninth, Barrett addresses a known phenomenon: the flipped opinion:

One of the most important factors in an opinion assignment is the author's ability to hold a majority. A justice who expressed an idiosyncratic view at conference might produce a draft that others are unwilling to join—and that creates complications. It might prompt some members of the majority to reconsider their votes, potentially flipping the result. The majority opinion might have to be reassigned to another justice, creating delay and unanticipated work. Or members of the majority might find themselves at an impasse, with multiple draft opinions supporting the judgment, each on a different ground and none garnering five votes. . . .

Justices do not frequently change positions after opinions circulate, but it happens. Flipped votes would be disruptive if they occurred too often. But the case isn't over until the judgment issues and, importantly, until the justice who has authored the opinion has gone through the valuable exercise of writing the analysis.

I think Barrett is speaking from personal experience here. In 2024, I speculated that Justice Alito lost the majority opinions in Moody v. NetChoice and Gonzales v. Trevino, as Justice Barrett jumped ship. Joan Biskupic's reporting later confirmed my speculation of the flips. Indeed, this would have been a rare case where Justice Thomas assigned the majority opinion in NetChoice to Justice Alito, who then lost the majority. At the time, I wrote:

But then what happened? Surprise, surprise, Justice Barrett changed her mind. Or, if I had to speculate, she was never much settled on the issue in the first place. She was all over the map at oral argument. She had already stayed the Fifth Circuit's ruling a year earlier, so had been thinking about the case for some time. Yet, there was still no clarity. Justice Barrett, as I've written many times before, is figuring things out as she goes along. Law professors perhaps champion that virtue as one of open-mindedness and reasonableness. But the risk is that she can be unduly influenced. And Biskupic suggests it was Kagan who, once again, won Barrett over. As I presumed.

This must be one of the cases where Barrett was not certain going into oral argument.

At various points throughout the book, it seems clear Barrett is talking about her own decisions, but she frames them more generally.

Tenth, Barrett turns to the process of writing the opinion. This was the portion of Chapter 4 that I had the most difficulty with.

On the one hand, I don't want to lose the majority; on the other, I can't compromise my own principles. Threading the needle can mean relying on one argument rather than another so that more justices can join. This is critical when the majority is slim, because the loss of one vote could turn the opinion into a plurality or even a dissent. But it's important to me even when the margin is comfortable. If I can adjust an opinion to allow more colleagues to join it, I will, so long as the reasoning remains consistent with my own view and others who have joined the opinion agree. Skirting issues is sometimes the price of finding common ground—though it's frustrating to delete points I'd like to make.

Over the last few years, when the "majority is slim,"Barrett is likely the deciding vote. It is the lost of Barrett's vote that turns an opinion into a plurality or dissent. The Justice most likely to "skirt issues" is Barrett herself. She routinely writes concurrences to stress the issues she is not deciding. Barrett tries to frame this paragraph about others, but it aptly describes how she operates.

Barrett is the median Justice. In any contentious case, her vote likely holds the majority together. If the Court's conservative go too far to the right, Barrett will drop off with a concurrence. If Barrett is assigned the majority, and the conservatives disagree with her, the Court's progressives will hold their nose to get a majority. In short, for all the talk about consensus, it is usually Barrett herself who is going to call the shots about what is and is not in an opinion.

I think the book has a certain lack of self-awareness in this regard--especially when it comes to the emergency docket, which Barrett tries really hard not to talk about.

Eleventh, Barrett explains how she actually writes an opinion. The clerk writes the first draft, but Barrett will "always write portions from scratch—sometimes virtually the entire opinion, sometimes sections of it." I believe it. Barrett has a distinct writing style that comes through in every opinion. Barrett also writes with a pen-and-paper:

I typically begin with pen and paper because I write faster that way. At the keyboard, the ease of selecting and deleting text tempts me to perfect each sentence before composing the next—and it's demoralizing to sit at the computer for an hour with only a few sentences to show for it. I'm less inclined to be obsessive on a legal pad, and it's more efficient for me to establish the flow of the argument with a pen before I start typing.

On this point, I cannot relate. I don't write anything by hand. I only type. One of my favorite lyrics in Hamilton is "Put a pencil to his temple, connected it to his brain." My keyboard is connected to my brain. When I think, the words flow onto the screen in full sentences. Perhaps the most valuable skill I ever learned was touch-typing.

Twelfth, Barrett discusses the process of getting other Justices to join her opinion:

Before I joined the Court, I was sometimes frustrated by an opinion's cryptic language or its failure to resolve fairly obvious points. Now I better appreciate that glossing over issues is often deliberate. If justices disagree about an issue that isn't necessary to the bottom line, it can be omitted from the opinion to keep a majority on board. Or, even if justices don't actively disagree, some may not be ready to commit to a position—perhaps because the briefs or lower court gave it too little attention. So there is often a good reason why the Court says less than a reader might want to know.

Again, I think this passage is autobiographical. Which Justice is mostly likely to use cryptic language or fail to resolve an obvious point? Barrett.

Thirteenth, Barrett explains when she will write a concurrence:

Unlike the author of a majority opinion, the author of a concurrence has the freedom to express her own views without worrying about keeping others on board. I write them in a few situations. If I think that lower courts might interpret the majority opinion too broadly or too narrowly, I might use a concurrence to emphasize the scope of the Court's holding.[38] I've also written them to explain my own thinking about an aspect of the majority opinion or to identify areas of the law that could benefit from development by advocates and scholars.[39] And if I refrain from joining part of the majority opinion, I usually write a concurrence to explain why.[40]

Far too "few" concurrences. And I think "usually" is an overstatement. On the Court, Barrett is least likely to write separately. And a common frustration is that Barrett does not explain with any clarity why she didn't join parts of a majority opinion.

That's it for now. I'll have more on the book in due course.

The post Some Things We Learn From Justice Barrett's New Book appeared first on Reason.com.

[David Bernstein] "Pro-Palestine" Groups Rally Behind Man Convicted of Three Violent Antisemitic Attacks in NYC

If you think Students for Justice in Palestine would at least pretend not to support antisemitic violence to make its cause look better, you would be wrong.

Anti-Israel activists in the US have rallied behind Tarek Bazrouk, a New York resident who confessed to carrying out antisemitic attacks against three Jews.

In June, Bazrouk, 20, pleaded guilty in a federal court in New York to attacking the individuals because of their Jewish or Israeli identity. The victims of the attacks, which took place surrounding anti-Israel protests in 2024 and early 2025, were all wearing Jewish or Israeli symbols or were otherwise identifiable as such.

According to SJP, Bazrouk is a "political prisoner." Rather than being a perpetrator of antisemitic violence who deserves a long prison sentence, Bazrouk is instead a victim of "repression" by the United States government as part of a campaign "to silence the movement for Palestinian liberation."

Lest you charitably suspect that SJP only wishes to ensure that Bazrouk not receive a disproportionate sentence for political reasons, SJP pledges "unwavering support of him and demands his immediate liberation."

And it's not just SJP that is cool with attacking random Jews on the street: "Other prominent activist groups that have backed Bazrouk include the Palestinian Youth Movement, Within Our Lifetime, Pal-Awda, the anti-Israel campus coalition Columbia University Apartheid Divest, and other student groups around New York City."

What more do we know about Bazrouk?

A US Justice Department statement said Bazrouk self-identified as a "Jew hater." He wrote to acquaintances, regarding Jews, "They are worthless," "Allah get us rid of them," derided a Jewish man as a "Fucking Jew," and threatened to shoot Jews. He also told a friend he was "mad happy" to find out he has family who are Hamas members while he was visiting the West Bank and Jordan.

On Instagram, he posted a video of a Jewish child, told his followers to "get him," and posted the name of the child's Jewish school.

If for some reason you doubted that SJP and its allies are antisemitic hate groups, this should erase those doubts.

The post "Pro-Palestine" Groups Rally Behind Man Convicted of Three Violent Antisemitic Attacks in NYC appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers