Eugene Volokh's Blog, page 30

September 23, 2025

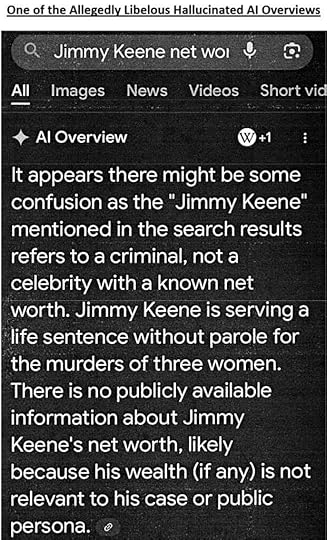

[Eugene Volokh] From Prison to Helping the FBI to an Apple TV Miniseries … to Google-Hallucinated Libel?

[Jimmy Keene, on whom the Apple TV miniseries Black Bird was based, sues Google alleging its AI hallucinated accusations that he's a convicted murderer serving a life sentence.]

From the Complaint in Keene v. Google LLC, just removed yesterday to federal court (N.D. Ill.); Keene's discloses that his work with the FBI happened while "he ended up on the wrong side of the law and was sentenced to ten years" in prison for drug conspiracy:

Plaintiff has written and published several novels and is best known for his memoir about his life and experiences, titled In with the Devil: A Fallen Hero, a Serial Killer; and a Dangerous Bargain for Redemption (2010). Plaintiff is well known for working with the FBI to uncover the crimes of the serial killer Larry Hall who was suspected of murdering many women. By helping the FBI secure evidence and proof against Hall, Plaintiff, working as an operative for the FBI, absolved himself of any wrongdoings and assisted in convicting Hall for multiple murders….

Plaintiff is an executive movie producer and consultant on various film projects and has deals with Paramount Pictures. Plaintiff owns a real estate development company and several other businesses….

On or about May 24, 2025, through May 26, 2025 …, Plaintiff was made aware, though friends and acquaintances of his, of statements that Google had posted and that Google had stated as fact on its own platform Google.com…. [Google] stated that Plaintiff "is serving a life sentence without parole for multiple convictions, according to Wikipedia." … The Wikipedia article regarding Plaintiff … did not state that Plaintiff is serving a life sentence without parole for multiple convictions.

Google LLC also stated through its platform, between May 26, 2025, and May 30, 2025, that "Plaintiff is serving a life sentence without parole for the murders of 3 women." Additionally, between May 26, 2025, and May 30, 2025, when asking about Plaintiffs' net worth Google stated through its platform that the Plaintiff "in the search results refers to a criminal, not a celebrity with a known net worth."

Plaintiff made a complaint to Google on May 27, 2025 informing Google about the false statements made by its platform. Google privately apologized to Plaintiff, stating that the statements were an unknown error made by their Artificial Intelligence Platform.

Google proceeded to edit their Platform and AI which resulted in more false statements…. Plaintiff contacted Google again and informed them about their defamatory statements; Google proceeded to apologize to Plaintiff again.

By repeatedly acknowledging and then apologizing for the false statements made on their platform Google acknowledged their existence, yet allowed such untruthful statements to continue to be published through their platform over a period of at least two months; Google demonstrably failed to take reasonable steps to correct misinformation which continued to be published with Google's actual knowledge as to the falsity of the statements….

For more on how libel law would apply to such cases, see Large Libel Models: Liability for AI Output? For more on the four earlier such cases in U.S. courts, see Battle, Walters, Starbuck, and LTL.

The post From Prison to Helping the FBI to an Apple TV Miniseries … to Google-Hallucinated Libel? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] What Apparently Didn't Happen in Lisbon Didn't Stay in Lisbon. Result: Libel Takedown Injunction

From Wednesday's decision by Judge K. Michael Moore in Signorello v. Murphy (S.D. Fla.):

{The following facts are taken from the Complaint, and a "party in default has admitted all well-pleaded allegations of fact" therein.} Underlying this action is an altercation between Plaintiffs and Defendant in Lisbon, Portugal.

Defendant accompanied Plaintiffs, who were both college students, on a night out after meeting by chance earlier that day, which according to Plaintiffs was initially welcome but became increasingly uncomfortable throughout the evening, culminating in an "almost manic" outburst from Defendant after which he started following Plaintiffs' group and accusing one of Plaintiffs' classmates, Harry, of stealing money. As Defendant continued to harass and follow Plaintiffs' group, Harry took out his wallet to offer Defendant the allegedly stolen cash to end the confrontation, but Defendant grabbed his wallet, tore up the bills, and yelled: "You think this money means anything to me?!"

After further attempts to retrieve the wallet, at the suggestion of nearby club bouncers the group went to the police, who located Defendant and forced him to return the wallet. Defendant again started yelling obscenities and otherwise harassing Plaintiffs' group, which led to a physical altercation where Defendant was attacking Harry and Plaintiffs were jumping on Defendant and pulling him to the ground to end his attack, after which they got away.

Immediately Defendant sought to make himself a victim of the attack, both in the moment and on social media in the following days, prompting the police to investigate Plaintiffs. Defendant spoke menacingly to Neubauer by mentioning his address in Tennessee, which he had apparently researched since the fight, and after Plaintiffs left Portugal, Defendant and his associates continued to send harassing messages to Plaintiffs' group over email, text, X, as well as sending defamatory and harmful information about Plaintiffs to their school, Washington & Lee University. Both Washington & Lee University and their study-abroad affiliate school in the United Kingdom required Plaintiffs to explain the altercation and Defendant's accusations.

Aside from the group, Plaintiffs' parents and Signorello's sister have also received harassing text messages with pictures of Defendant's injuries and demands for payments, among other texts characterizing Plaintiffs as having committed a crime, which caused them academic and professional issues and embarrassment.

Plaintiffs sued for, among other things, defamation; the defendant failed to adequately respond, and was thus found in default, which meant that plaintiffs' factual allegations were accepted. Here is the court's analysis:

[1.] Plaintiffs ask the Court to enjoin Defendant from publishing defamatory statements, "including but not limited to Internet, emails, text, and social media posts, including but not limited to any allegation stating, or implying, that Plaintiffs harmed the Defendant," to enjoin him from contacting Plaintiffs' "employers, universities, friends and family regarding the Plaintiffs" as well as with Plaintiffs and their affiliates, and to order him "to remove any existing social media or other internet posts making statements regarding the Plaintiffs." …

It is well-settled Florida law that "absen[t] some other independent ground for invoking equitable jurisdiction, equity will not enjoin either an actual or threatened defamation" as that would constitute an unconstitutional prior restraint. There is disagreement among courts as to whether this rule continues to apply when there has been an actual finding of particular speech being false and defamatory, either by judge or jury, which has sometimes been called the "modern rule." See Basulto v. Netflix, Inc. (S.D. Fla. 2023) (collecting cases as to this split). While most cases recognizing the modern rule have been outside of this District, and there are no decisions binding on this Court that have adopted it, at least one court in this District has granted injunctive relief for defamation on the "independent ground" that "an action at law would not be a complete, prompt and efficient remedy."

Plaintiffs have satisfied the three prongs of the test for a permanent injunction based on the Court's finding that they adequately stated their claim for defamation, mere damages will not stop Defendant from continuing his ongoing digital harassment campaign against Plaintiffs and their affiliates, and that as Defendant's campaign continues so does the harm to Plaintiffs as they are forced to defend themselves against false accusations to friends, family, schools, and employers. The remaining question, therefore, is whether such an injunction may be granted in this defamation context.

The courts in Lustig v. Stone (S.D. Fla. 2015) and Saadi v. Maroun (M.D. Fla. 2009) granted permanent injunctions narrowly tailored to only postings that the defendants had already made online and had already been found to be defamatory. Lustig ("[Defendant] has shown through her conduct a single-minded intent to destroy [Plaintiff] professionally and personally …. In particular, the Undersigned notes that none of [Defendant's] defamatory internet postings about [Plaintiff] have been taken down and they continue to damage his reputation."); Saadi ("[T]he Court finds that [Defendant] should be enjoined from continued or repeated publishing of the statements that were found by the jury to be defamatory. However, the scope of the injunction must be limited to those statements.").

The Court will similarly constrain itself here. Accordingly, Plaintiffs will be granted a limited permanent injunction covering only statements regarding Defendant's false and defamatory assertions that Plaintiffs attacked, assaulted, robbed, or otherwise committed criminal acts against or harmed Defendant, which allegations Defendant has admitted by default.

This injunction requires Defendant to both take down the existing internet posts of any kind that reflect these defamatory assertions and cease and desist from making any outreach to Plaintiffs and their affiliates, including any institutions and actual or prospective employers, to convey the same including but not limited to internet, emails, texts, and social media posts. The injunction will not extend to a broad category of unspecified "derogatory statements" or "any statements about either or both of the Plaintiffs," and instead will be limited to any statements that reflect the information properly presented to the Court and that has been specifically adjudicated as defamatory….

Marty Steinberg and Hans H. Hertell (Hogan Lovells) represent plaintiff.

The post What Apparently Didn't Happen in Lisbon Didn't Stay in Lisbon. Result: Libel Takedown Injunction appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] No Preliminary Injunction Against Publishing Billionaire's Cryptocurrency Asset Details

From Judge Colm Connolly's opinion yesterday in Sun v. Bloomberg, L.P. (D. Del.):

On August 11, 2025, after months of working to verify Sun's assets, Bloomberg published Sun's profile in its Billionaires Index, "a ranked list of the world's richest people." Two sentences of the profile are at issue here:

Sun owns more than 60 billion Tronix (also referred to as TRON or TRX), the cryptocurrency native to Tron, according to an analysis of financial information provided by representatives of Sun in February 2025…. Sun also owns about 17,000 Bitcoin, 224,000 Ether, and 700 million Tether, according to the same analysis.

According to Sun, (1) Bloomberg's publication of "the alleged specific amounts of cryptocurrencies" he owns constitutes a public disclosure of private facts, and (2) Bloomberg is estopped from publishing "financial information regarding the value of specific assets and details related to [his] ownership of those assets" because it promised him that it would not publicize "the amounts of specific cryptocurrency" he owns and that it "would take measures to protect [his] Confidential Financial Information from disclosure."

Within hours of Bloomberg's publication of the profile, Sun filed in this Court his initial Complaint and a motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction. He withdrew the motion three days later because, according to Sun, the parties were "engaged in discussions" that may have mooted the motion. Those discussions apparently did not go well, however, because on September 11, Sun filed the instant motion, seeking a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction requiring Bloomberg (1) "to remove the amounts of any specific cryptocurrency owned by Mr. Sun from any of its online publication," (2) "to retract its claim that Mr. Sun owns 60 billion Tronix and controls the majority of its supply," and (3) to refrain from "publishing the amounts of any specific cryptocurrency owned by Mr. Sun in any future publication." …

Sun has not made a clear showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits of his promissory estoppel claim. To prevail on this claim, Sun would have to "demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence" that (1) Bloomberg made a promise; (2) it was the reasonable expectation of Bloomberg to induce action or forbearance on the part of Sun; (3) Sun reasonably relied on the promise and took action to his detriment; and (4) such promise is binding because injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise.

Sun makes several attempts to establish the first element of his promissory estoppel claim-that Bloomberg made a promise. Each fails. He first asserts that in the conversations that "predated his decision to participate in the Billionaires Index, Bloomberg made express promises that any information provided to Bloomberg would only be used to verify his personal assets." In support of this proposition, Sun cites his own declaration in which he states that Muyao Shen, a Bloomberg reporter, "told [him] that any information [he] provided to Bloomberg for the purpose of verifying [his] personal wealth would be kept strictly confidential and would only be used to verify [his] personal assets for the Billionaires Index profile."

Bloomberg counters with declarations of its own. Muyao Shen, the reporter who Sun asserts made express promises regarding confidentiality, attests in a declaration that she did not "make any promises of confidentiality regarding any aspects of Bloomberg's coverage of Mr. Sun." Two members of Bloomberg's Billionaires Index team, Dylan Sloan and Tom Maloney, also attest that they never "promised confidentiality in connection with the information Mr. Sun and his team were sharing with Bloomberg for the Bloomberg Billionaires Index." On this record, I cannot say that Sun has made a clear showing that Bloomberg "made express promises that any information provided to Bloomberg would only be used to verify his personal assets." [Discussion of further claims that Bloomberg had promised confidentiality omitted. -EV] …

In short, on this record, Sun has not shown clearly that Bloomberg made a promise of confidentiality. He therefore has not shown clearly that he is likely to succeed on the merits of his promissory estoppel claim.

Next up is Sun's claim for public disclosure of private facts. To prevail on this claim, Sun would need to prove: (1) public disclosure, (2) of a private fact, which would be offensive and objectionable to the reasonable person, and which is not of legitimate public concern. Regarding the third element, Sun asserts that Bloomberg's publication of his cryptocurrency assets "to millions of online readers and [threats] to further publicize it in an additional article" would be highly offensive to a reasonable person because "the knowledge of what cryptocurrency [he] owns makes him an increased target for hacking, phishing, social engineering, kidnapping, or bodily injury." But before Bloomberg published Sun's profile, other entities, including Nansen, provided similar (if not more detailed) estimates of Sun's assets. And Sun himself has disclosed far more specific information about his Bitcoin holdings than what Bloomberg published:

Accordingly, at this stage, I cannot say that Bloomberg's publication of estimates of Sun's cryptocurrency holdings—information that is arguably less specific than what other entities and Sun himself have made public—would be objectively offensive to a reasonable person. Thus, Sun has failed to show clearly that he is likely to succeed on the merits of his public disclosure of private facts claims….

Jeffrey J. Lyons, Isabelle Corbett Sterling, Teresa Goody Guillen, and Katherine L. McKnight (Baker & Hostetler LLP) and James M. Yoch, Jr. and Robert M. Vrana (Young Conaway Stargatt & Taylor, LLP) represent Bloomberg.

UPDATE: I originally titled this post "no liability for publishing billionaire's cryptocurrency asset details," because the court's reasoning suggests that there's likely no basis for liability under either of the plaintiff's theories. But technically the decision was just that there was no likelihood of success on the merits (since the court was asked to issue a preliminary injunction), so I decided to update the title accordingly.

The post No Preliminary Injunction Against Publishing Billionaire's Cryptocurrency Asset Details appeared first on Reason.com.

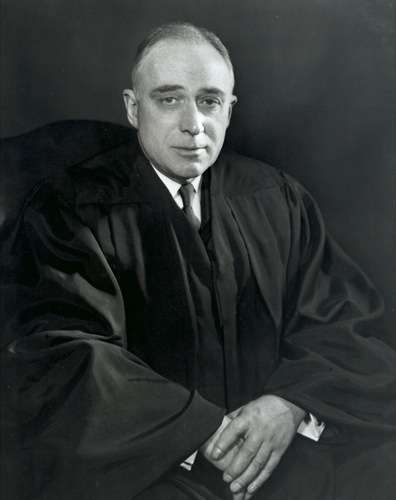

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: September 23, 1971

9/23/1971: Justice John Marshall Harlan II resigns.

Justice John Marshall Harlan II

Justice John Marshall Harlan II

The post Today in Supreme Court History: September 23, 1971 appeared first on Reason.com.

September 22, 2025

[David Kopel] The Dean of Gun Lobbyists

[John Snyder’s Oral History]

In November 2015, I recorded an oral history with John Snyder, who was then-retired as "the dean of Washington gun lobbyists." A pivotal figure in the gun rights movement, he passed away in 2017 at age 79. He started in 1966 with the National Rifle Association (NRA), then in 1975 co-founded and became the lobbyist for the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms (CCRKBA), serving in that capacity until he retired in 2011.

The full 31-page oral history interview was recently published as a Working Paper by the University of Wyoming College of Law's Firearms Research Center: John Snyder: An Oral History of the Dean of Washington Gun Lobbyists. Below, I summarize some of our conversation at his home in Bethesda, Maryland, starting with the emergence of the gun control debate in the 1960s.

From Georgetown to the NRA

John Snyder entered the gun rights arena almost by accident. In 1966, at age 26, he was a Georgetown University graduate student in political science, preparing for his master's comprehensive exam and seeking part-time work so that he could focus on his studies. A classmate's tip led him to a "Boy Friday" job at The American Rifleman, the NRA's flagship magazine.

At the time, the NRA was a sleepy organization of 800,000 members, primarily target shooters, hunters, and collectors, with little appetite for political engagement. Snyder explained, "there was no pro-gun movement or pro-gun lobby" in 1966. Gun ownership was simply assumed to be a right of law-abiding Americans.

The landscape shifted after the 1966 University of Texas shooting and the 1963 assassination of President Kennedy. Senator Thomas Dodd (D-Conn.) was Chairman of Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency and had been criticizing violence on television and cinema. Franklin Orth, the NRA's Executive Vice President, told Snyder that "pressure was put on Dodd by Hollywood and a lot of the advertisers on Hollywood to get off the film kick. And somebody pointed him in the direction of the firearms kick."

Snyder's work at The American Rifleman under editor Ashley Halsey, Jr., placed him at the forefront of the NRA's nascent response. Halsey, a former Saturday Evening Post features editor, saw the need to counter anti-gun propaganda. He tasked Snyder with research, and Snyder began digging through Library of Congress archives for quotes from dictators on disarmament. He recalled:

These were English translations of all their writings and for like Stalin, there'd be 40 volumes. . . I went through those volumes piecemeal and found out things that these various dictators have had to say about disarming the people and so on. All of which has become common knowledge now but at that time it wasn't, because the research hadn't been done. I did the research which involved me sitting in the Library of Congress for hours going through all these filthy old books.

These findings informed editorials, some reprinted in the Congressional Record by pro-gun Democrats like Rep. Bob Sikes of Florida.

Yet the NRA remained divided. Many members and leaders, including Executive Director Louis Lucas, resisted lobbying, viewing it as unseemly. However, as Snyder repeatedly affirmed:

They were very patriotic, good, good people, but just totally unprepared for the political onslaught that was building at that time. . . The people who didn't want to get too involved in the public defense of the Second Amendment thought . . . the war would peter out. . . Because they had grown up in the old America, they couldn't conceive of anybody wanting to take guns take away. I mean, they just couldn't believe it!

As a reporter for The American Rifleman, Snyder investigated the Kenyon Ballew case and exposed law enforcement misconduct. On June 7, 1971, in Silver Spring, Maryland, the Montgomery County Police and the new federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (BATF) broke down the door of the wrong apartment, shot first, and severely injured Kenyon Ballew. Next, they fabricated a case, ultimately unsuccessful, purporting that Ballew had violated the National Firearms Act.

George Gordon Liddy

One day in June 1972, Snyder and a friend were heading out to lunch in Washington, D.C., near the then-headquarters of the NRA, at 1600 Rhode Island Avenue, N.W. They ran into G. Gordon Liddy, whom Snyder knew from upstate New York, and as a White House aide who often came to the NRA building to shoot at the handgun range. They invited Liddy to "come to lunch." To which he replied, "'Guys I'd love to," but 'We've got to re-elect the president."

"THAT night was Watergate!" said Snyder.

Snyder recalled that he and the friend "both thought that was kind of strange" at the time for Liddy to say what he did, even in the context of Liddy's typical "hardcore" demeanor.

The Rise of a Movement and Birth of the CCRKBA

While still employed at NRA, Snyder made contacts with Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), and became their gun policy expert, mentoring YAF's National Students Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms. Collaborating with another YAF figure, Alan Gottlieb, Snyder created the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms. On January 1, 1975, he started with a single desk in a shared office.

In those early days, two congressmen were particularly helpful:

John Ashbrook was a member of Congress from Ohio, and he was a Republican. One of the last real, solid anti-communist types in the House. He at that time was a minority leader of the Subcommittee on Crime of the House Judiciary Committee. He and I talked a lot. He just said he told the other Republicans that he thought I could be trusted, and I'd never let them down, and I'd always give 'em the straight scoop. He made sure I got invited to testify and so on.

There was a guy on the Democrat side who was the same way, Larry McDonald. . . Larry Patton McDonald. He was the nephew of General George Patton. His mother was George Patton's sister. So I developed the ability to deal with people in both parties, mainly through the efforts of these two congressmen.

Snyder provided legislators with data and talking points, which they shared with colleagues, and he gave lectures for congressional staff.

He also began a long-running holiday tradition of mailing pro-gun Christmas cards. The first one "just had Santa Claus getting ready to put a firearm in a box under the Christmas tree." Because the printer hand printed thousands, Snyder kept the cards, and mailed them widely the next Christmas, this time to every congressperson. It did not go over well with some. Rep. Jonathan Bingham (D-N.Y.) delivered a speech on the House floor expressing his outrage. CBS Evening News anchorman Walter Cronkite denounced the card. Snyder laughed in recollection of the free publicity.

Perspective over Half a Century

Snyder reflected on the transformations of lobbying over the previous half-century. In the 1960s, lobbying was not a recognized profession. By 2015, Washington hosted tens of thousands of lobbyists, with universities offering master's degrees in legislative affairs. Large firms now dominate, contracting with interest groups.

Corporate lobbying, Snyder observed, offered high salaries but lacked the heart of cause-driven work. His own efforts were fueled by a belief in the Second Amendment as a God-given right, not a government-granted privilege.

In 2015, Snyder described the Second Amendment as "tenuous" because many people felt "that no right, in and of itself, exists other than as something granted or conceived of by the government. . . [T]he right of individuals is always tenuous. Not only now. That always has been the case. You can go way back into ancient history," starting with Plato, the philosophical founder of dictatorship.

It should be noted that Snyder in February 2016 became the first national figure in the gun rights movement to endorse Donald Trump for President. Some considered the endorsement shocking, including because of Trump's erratic record on gun issues from interviews in previous years.

Fighting the Good Fight

John Snyder and I became friends starting in 1988, when he interviewed me for a newsletter article naming me "Gun Rights Defender of the Month." He was a good man, with a passion for human rights. It was a blessing to have known him.

The above post was previously published on the website of the University of Wyoming College of Law, Firearms Research Center.

The post The Dean of Gun Lobbyists appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] S. Ct. Agrees to Hear Merits Case on Whether President Has Power to Remove "Independent" Agency Heads (the Humphrey's Executor Overruling Question)

From today's order in Trump v. Slaughter:

The application is also treated as a petition for a writ of certiorari before judgment, and the petition is granted. The parties are directed to brief and argue the following questions: (1) Whether the statutory removal protections for members of the Federal Trade Commission violate the separation of powers and, if so, whether Humphrey's Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935), should be overruled. (2) Whether a federal court may prevent a person's removal from public office, either through relief at equity or at law.

Justice Kagan, joined by Justices Sotomayor and Jackson, dissented from the Court's staying the lower court decision, which had temporarily ordered FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter reinstated.

The post S. Ct. Agrees to Hear Merits Case on Whether President Has Power to Remove "Independent" Agency Heads (the Humphrey's Executor Overruling Question) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Ilya Somin] Courts are Checking Trump More Effectively than Many Think

[Legal scholar Steve Vladeck explains how and why. ]

AI-generated image.

AI-generated image. There is a widespread perception - reinforced by a number of high-profile Supreme Court decisions - that the judiciary has been largely ineffective in curbing the second Trump Administration's many illegal actions. In an insightful recent post, Georgetown law Professor Steve Vladeck (one of the nation's leading experts on the Supreme Court and the federal judiciary), explains that courts have actually had more impact than many think:

There is, alas, plenty of Supreme Court-related news…. But I wanted to use this week's "Long Read" to tell a slightly different story—about cases that aren't making headlines, for instance, the ongoing litigation challenging President Trump's executive order purporting to limit birthright citizenship. That order remains on hold—thanks to a series of rulings by lower courts after the Supreme Court's 6-3 ruling on June 27. These lower-court rulings have flown under the radar—at least largely because the government has not sought emergency relief from the courts of appeals or the Supreme Court, nor has it refused to comply with them. For now, it is "taking the L."

That's an important story unto itself—not just in the birthright citizenship cases, but more generally. For all of the attention that is (understandably) being paid to the unprecedented number of cases the Trump administration is rushing to the Supreme Court (we're up to 28), and to the Court's (troubling) behavior in those cases, they represent only a small subset of the broader universe of legal challenges to Trump administration behavior. In the majority of cases in which the government is losing in the lower courts, it is (1) not seeking emergency or expedited intervention from above; and (2) otherwise complying with the adverse rulings while the cases move (very slowly) ahead.

Because this reality doesn't make for quite as attractive headlines, it's one to which too many folks are largely oblivious. That's a problem worth fixing—not only because it's important to tell both sides of the litigation story, but because including these cases paints a more complicated (and, in my view, far less nihilistic) picture of the role of the courts—and of the law, more generally—as a check on the Trump administration.

Vladeck goes on to explain that the birthright citizenship order - like a number of other Trump policies - remains blocked by lower courts, and that the administration often chooses not to appeal, or to do so only slowly. He also notes that this record shows that the Court's ruling in Trump v. CASA, Inc., barring most universal injunctions, has so far not had the devastating effect some predicted, because lower courts have found other ways to impose broad injunctions constraining illegal policies:

[F]olks might recall the loud and sharp debate following on the heels of the Supreme Court's ruling in CASA over just how much (or how little) of an impact that decision would have on the ability to challenge lawless (and allegedly lawless) behavior by the Trump administration. As I wrote at the time, the answer was always going to depend upon what happened both on remand in those three cases and elsewhere—and on how viable other means of seeking nationwide relief would be in challenges to Trump administration policies. It's still early, but at least so far, the returns have largely borne out the views of those who did not think that CASA would be a cataclysm. To be clear, that doesn't mean CASA was rightly decided (or even rightly framed, as Professor Jack Goldsmith has explained). And the Court may yet impose tighter limits on (1) nationwide class actions; (2) state standing; (3) what plaintiffs must show to demonstrate that a universal injunction is necessary to obtain "complete relief"; or (4) nationwide vacatur of rules under the Administrative Procedure Act—any of which will necessarily affect the ability of plaintiffs to bring nationwide challenges to federal policies. But at least for now, CASA's effects have been decidedly modest—and felt most perhaps by lawyers, who have had to reconfigure many of the lawsuits against the Trump administration.

Vladeck opposes the ruling in CASA (as do I). But he's right that its impact will depend on the scope and availability of alternative modes of relief. I made a similar point in my post criticizing CASA at the time it came down.

I think Vladeck's other points here are mostly well-taken, as well. In assessing the impact of the judiciary we should look to the full range of cases, not just those that reach the Supreme Court on the "shadow" docket, as the latter are in some ways unrepresentative (Vladeck is a well-known longtime critic of the shadow docket). His analysis undercuts some left-wing narratives about the seeming ineffectiveness of the judiciary. And, as he notes, it also undercuts right-wing narratives to the effect that lower-court rulings against the administration are all indefensible "Lawfare" that will surely be overturned by the Supreme Court. If the latter were true, we would expect to see the Administration taking many more of these cases to the Supreme Court, at an accelerated pace.

That said, we should not assume that the judiciary has been completely effective, or even close to it. Some of the Supreme Court's rulings blocking lower court decisions against Trump have been badly flawed and are likely to have harmful effects. The recent ruling on racial profiling in immigration enforcement is a notable example. And some illegal actions are hard to stop completely or swiftly enough through judicial rulings alone.

More generally, as I argued in an UnPopulist article published in June, the challenge posed by Trump should be met by a combination of litigation and political action. The two should be mutually reinforcing, and it is unlikely either can work completely alone. Vladeck's piece shows the situation isn't as bad as some think. But there is no cause for complacency.

The post Courts are Checking Trump More Effectively than Many Think appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] May a Guardian Get a Divorce on Behalf of a Mentally Incapacitated Adult?

["Marriage pre-dates and transcends our law (and will post-date our law, I expect)."]

A short excerpt from the long majority in In the Matter of Benavides, by Justice Jeffrey Boyd:

A woman appointed as guardian for her elderly father moved him out of the house he shared with his fourth wife and later filed for divorce on his behalf on the ground that the couple had lived apart for more than three years. The trial court granted the divorce, and the wife appealed…. The wife [appeals], arguing [that] … Texas law does not permit a guardian to sue for divorce on her ward's behalf ….

We need not definitively decide [this] issue …. To whatever extent the Texas Estates Code may allow a guardian to seek a divorce on her ward's behalf, it at least requires the guardianship and divorce courts to find that permitting the divorce would promote the ward's well-being and protect his best interests. Because neither court made that finding in this case and—because of the ward's death—neither can do so now, we reverse the court of appeals' judgment, vacate the divorce decree, and dismiss….

Carlos "C.Y." Benavides, Jr. was the [wealthy] patriarch of "one of Laredo's oldest and most powerful clans." … Carlos married his fourth wife, Leticia Russo, on September 11, 2004. They each signed a pre-marital agreement and a post-marital agreement in which they stipulated that no community property would ever be created during the marriage and that each spouse's separate property and any income it produced would belong solely to that spouse, or to his or her estate, unless one transferred the property to the other "by will or other written instrument."

About seven months after Carlos and Leticia married, Carlos filed for divorce (the First Divorce Proceeding). About five months later (a year after they married, and while the divorce proceeding was pending), a physician diagnosed Carlos with dementia. Carlos did not pursue the divorce, and the trial court dismissed the First Divorce Proceeding for want of prosecution in February 2007. Leticia asserts that Carlos changed his mind about wanting a divorce. Carlos's adult daughter from a prior marriage—Linda Cristina Benavides Alexander—contends that Carlos wanted the divorce but was unable to pursue it because of his quickly worsening dementia.

By the end of 2007, Carlos had signed documents adding Leticia's name to his bank accounts, designating the accounts as joint accounts with a right of survivorship, conveying an office building to Leticia, and identifying both spouses as borrowers on a loan to refinance their residence. Leticia asserts that Carlos gave her "full authority" over his accounts and repeatedly told her that "todo lo mio es tuyo"—"all that I have is yours." Linda contends that, to the extent Carlos in fact did or said any of these things, he did so only because Leticia took advantage of his mental incapacity. The ensuing disputes between Linda and Leticia have led to numerous lawsuits and appeals ….

And an interesting concurrence by Chief Justice Jimmy Blacklock, joined by Justices John Phillip Devine and James Sullivan:

"The [marriage] relation itself is natural; the prescribed impediments and the forms of laws for its legal consummation are artificial, being the work of government." The nature of marriage is such that it:

cannot be created except by the consent of the parties. It cannot be dissolved except by the consent and the intelligent exercise of the will of one of the parties. That is to say, that no matter what or how many valid grounds for divorce exist, it is only by the decision and will of the party aggrieved that an action for divorce may be brought.

The parties disagree on whether a guardian may obtain a divorce on behalf of a ward who lacks the capacity to intelligently seek an end to his marriage. The Court prudently declines to definitively answer that question because answering it turns out to be unnecessary to the disposition of this case. I do not object to the Court's silence, and I join the Court's opinion and judgment in full. I write separately with the following observations for consideration in future cases.

The traditional view … is that an "exercise of the will" is an essential element of both marriage and divorce. It follows from this traditional view that a guardian cannot obtain a divorce on behalf of a ward who cannot intelligently exercise his will to divorce. As the Court observes, some jurisdictions continue to hold the traditional view, while others have abandoned or modified it by authorizing guardians to obtain divorces on behalf of incompetent wards to varying degrees. The Court does not articulate Texas law's answer to the question. Neither does the Family Code. That does not mean there is no answer, although I agree that this Court's articulation of the answer should await a case in which the answer is necessary to the judgment.

The question is whether the law should—or even can—separate marriage and divorce from their essentially volitional nature by authorizing divorces even when neither party has personally, willfully sought a divorce. The traditional common-law view—the near-universal view until recent decades—says no. The basic moral and legal judgment from which the traditional view proceeds is that marriage and divorce are, in their nature, expressions of the will of the husband and wife and therefore cannot come about, either naturally or legally, absent a manifestation of that will. The judges who developed and preserved this view over the centuries were not merely making a legal judgment about the legal construct of marriage. They were making a moral judgment about the nature of an ancient and enduring fact about our civilization, a fact the law did not create and upon which the law merely purports to act around the edges. That fact is marriage.

Marriage pre-dates and transcends our law (and will post-date our law, I expect). Marriage is a unique, natural relationship reflected in the law and recognized by the law, but it was not created by the law. If marriage is a natural fact upon which the law acts, then judges and lawmakers must make judgments about the nature of marriage in the course of determining how the law will act upon it. Just as a judge must know what property is in order to say how a person's ownership of it can be ended, a judge must know what marriage is in order to say how a person's participation in it can be ended.

This kind of thinking inevitably entails a degree of moral judgment. We should not hide from that or try to conceal it. When the law delves into intimate moral questions like marriage, divorce, and family life, moral judgments are being made, whether we acknowledge it or not—both by judges and by legislators. A judge who thinks of marriage as a civil legal status created by and governed by the Family Code may not bat an eye at the notion that a guardian can seek divorce for an incompetent ward, just as a guardian may do many other important things for a ward. But a judge who thinks of marriage as a natural expression of the will of a man and a woman, which exists apart from and transcends our law's codification of it, is far more likely to gravitate toward the traditional view, as did an unbroken line of judges of generations past.

Judges of previous generations did not hesitate to adopt the traditional view, the truth of which seems to have been obvious to them. They developed, over the years, a longstanding rule that continues to prevail in many American jurisdictions. That traditional rule converts a moral judgment into a legal judgment, as judges so often do, whether or not we admit it. "Under the traditional rule, courts do not read statutes granting guardians general powers to act on behalf of the ward as authorizing divorce actions because the decision to divorce is too personal and volitional to be pursued at the pleasure or discretion of a guardian." The legal judgment is that courts will not read statutes granting general powers to a guardian to authorize the divorce of a ward. The moral judgment, which is the justification for the legal judgment, is that divorce is "too personal and volitional to be pursued at the pleasure or discretion of a guardian."

When modern courts abandon the traditional rule, they do not abandon the realm of moral judgment. Confronted with their predecessors' moral judgment that marriage and divorce are "too personal and volitional" to be pursued by proxy, they have responded with their own moral judgment—that marriage and divorce are not "too personal and volitional" to be pursued by proxy. There is no escaping the moral content of the judgment. What changed in the second half of the twentieth century as many courts moved away from the traditional rule was not that judges moved away from making moral judgments about marriage and divorce. The change was in the content of the judges' moral judgments. { Of course, if a legislature specifically codifies the power of guardians to obtain divorces for incompetent wards, then the legislators, not the judges, have made the relevant moral judgment, and the judges are likely bound to follow it. Yet in most of the states that have trended in the direction of allowing guardians and judges to decide whether a ward should divorce, it is the judges, not the legislators, who have driven the change.}

* * *

For many people, marriage is primarily a spiritual matter, not merely a legal one. {See Genesis 2:24 ("Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh.").} Quite obviously, courts are not well suited to judge the spiritual benefits of marriage or divorce on behalf of an incompetent person. And for everyone, regardless of religion, marriage is a uniquely personal matter. This is why the traditional rule holds that the decision to begin or end a marriage must be made by the individual people involved in this most intimate of human relationships, not by third parties like guardians and judges.

Texas appears largely to have followed the traditional rule for most of our history. Then, in 1988, this Court in Wahlenmaier v. Wahlenmaier stated—without elaboration or analysis—"that a guardian ad litem or next friend can exercise the right of a mentally ill person to obtain a divorce." Wahlenmaier does not grapple at all with the deep moral and jurisprudential foundations of the traditional rule with which it is in tension. The Court does not engage with those questions again today, nor need it have done so.

As the Court recognizes, if the answer ends up being that a divorce may be obtained by a guardian on a ward's behalf, then the fate of the ward's marriage turns ultimately on a best-interest determination by a judge, not on an expression of the ward's desire to end the marriage. But it seems to me that whether a person will become married or will remain married are questions that are, in their very nature, impervious to a third-party's best-interest analysis.

In other words, whether I want to be married and whether somebody thinks I should be married are two completely different questions, and only the former has any bearing on the question of whether I am or will remain married. If an essential element of both marriage and divorce is the freely given expression of the human will, then when nature renders it impossible for that will to be expressed, neither a judicial best-interest analysis nor anything else can replace it. The thing can no longer be done. If we pretend otherwise, we are changing the nature of the thing.

I am inclined to think that only the individual person can answer, for himself, whether he should be married. If he becomes incapable of answering the question, there is nobody else to ask. The question can no longer be answered.

The courts, when properly called upon, can do our best to help manage the affairs of all involved in such a difficult circumstance with prudence and compassion. But we should not presume to answer a question that is not ours to answer. That has been the traditional, majority view of these matters throughout American legal history. I find it to be a compelling view, one which the Court may have occasion to adopt in a future case.

* * *

As the Court observes, the "recent and growing trend among American courts" is against the traditional view. On this and other matters, if I must choose between the accumulated wisdom of the ages and the "recent and growing trend among American courts," I expect the choice will be easy.

The post May a Guardian Get a Divorce on Behalf of a Mentally Incapacitated Adult? appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The Heritage Guide to the Constitution: Essay Nos. 1–25

To continue my preview of The Heritage Guide to the Constitution, which will ship on October 14, here are the authors of the first twenty-five essays.

Essay No. 1: Preface —Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. U.S. Supreme CourtEssay No. 2: Foreword —Edwin Meese Iii Chairman Emeritus, Advisory BoardEssay No. 3: Editors' Note —Josh Blackman Senior Editor, John G. Malcolm Executive EditorEssay No. 4: The Preamble —John W. Welch & James A. HeilpernEssay No. 5: The Legislative Vesting Clause —Gary S. LawsonEssay No. 6: The House Of Representatives Clause —Bradley SmithEssay No. 7: The Elector Qualifications Clause —Derek T. MullerEssay No. 8: The Qualifications For Representatives Clause —Derek T. MullerEssay No. 9: The Three-Fifths Clause —Rebecca E. ZietlowEssay No. 10: The Enumeration Clause —Andrew C. SpiropoulosEssay No. 11: The Congressional Apportionment Clause —Michael R. DiminoEssay No. 12: The Executive Writs Of Election Clause —Paul TaylorEssay No. 13: The Speaker Of The House Clause —C. Towner FrenchEssay No. 14: House Impeachment Clause —Michael J. GerhardtEssay No. 15: The Senate Clause —Martin GoldEssay No. 16: The Senatorial Classes And Vacancies Clause —Martin GoldEssay No. 17: The Qualifications For Senators Clause —Martin GoldEssay No. 18: The Vice President As Presiding Officer Clause —Roy E. Brownell IiEssay No. 19: The President Pro Tempore Clause —Roy E. Brownell IiEssay No. 20: The Senate Impeachment Trial Clause —Michael J. GerhardtEssay No. 21: The Impeachment Judgment Clause —Michael J. GerhardtEssay No. 22: The Elections Clause —Derek T. MullerEssay No. 23: The Congressional Assembly Clause —Michael SternEssay No. 24: The Judge Of Elections Clause —Derek T. MullerEssay No. 25: The Quorum Clause —Seth Barrett TillmanThe post The Heritage Guide to the Constitution: Essay Nos. 1–25 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Indiana Court Sets Aside $250K Default Judgment in Lawyer's Libel Case Related to "Scathing Google Review"

From Thursday's decision in Gillikin v. Mattingly, decided by Indiana Court of Appeals Chief Judge Robert Altice, joined by Judges Rudolph Pyle and Mary DeBoer:

Amy Gillikin appeals the trial court's denial of her motion to set aside a $250,000 default judgment entered against her for defamation, which was based on a scathing Google review that she posted online about Janice Mandla Mattingly and Mattingly's law firm, Janice Mandla Mattingly, P.C., D/B/A Carmel Family Law (collectively, Mattingly)….

In June 2024, Mattingly and Gillikin did not personally know each other, but Mattingly represented the former spouse of Gillikin's fiancé in a pending legal matter involving child custody and parenting time. Around the middle of that month, Gillikin posted a review on Mattingly's Google review page.

In the post, Gillikin described Mattingly as a corrupt attorney and a monster, who exploits abused children for her own monetary gain, and who would soon be disbarred. Gillikin suggested that Mattingly colludes with the Hamilton County magistrates, among others, and that Mattingly knows that her clients continue to abuse their children. She concluded her post: "We pray that the Attorney General can stop this racket before anymore children are affected by her unethical conduct." …

Mattingly got a default judgment against Gillikin, because Gillikin didn't timely respond to the lawsuit. But the appellate court concluded that the trial court should have set aside the judgment:

We first address whether Gillikin alleged a meritorious defense to the defamation action. Her defense was that the statements she made in the post were true, and she testified as such and that she looked forward to proving it all true at a trial on the merits. When she attempted to provide the basis for her belief that the statements were true, she was cut off by Mattingly with an improper hearsay objection and then the court redirected the parties to Gillikin's procedural failure to respond to the complaint.

In any case, Gillikin asserted a meritorious defense, as "[t]ruth is an absolute defense to a claim of defamation." And her testimony, despite its self-serving nature, was sufficient to clear the low bar of making a prima facie showing of a meritorious defense. Contrary to Mattingly's claim on appeal, Gillikin was not required at this stage to provide evidence that proved the truth of the defamatory statements.

We now turn to Gillikin's claim that the trial court abused its discretion by refusing to set aside the default judgment based on T.R. [Rule of Trial Procedure] 60(B)(8)…. Our Supreme Court has cautioned:

[T]he important and even essential policies necessitating the use of default judgments—maintaining an orderly and efficient judicial system, facilitating the speedy determination of justice, and enforcing compliance with procedural rules—should not come at the expense of professionalism, civility, and common courtesy. An extreme remedy, a default judgment is not a trap to be set by counsel to catch unsuspecting litigants and should not be used as a gotcha devi[c]e when an email or even a phone call to the opposing party inquiring about the receipt of service would prevent a windfall recovery and enable fulfillment of our strong preference to resolve cases on their merits….

Here, just over a month after Gillikin posted the allegedly defamatory Google review and only twenty-five days after service of the complaint and summons, Mattingly sought a default judgment against Gillikin and damages of $250,000. This was the quintessential gotcha maneuver, which worked when the very next day the trial court granted Mattingly's motion and awarded $250,000 without holding a hearing.

Gillikin quickly sought to set aside the judgment, filing her motion twelve days after the default judgment was entered. At the hearing on Gillikin's motion, Gillikin testified that everything she stated in the review was a fact, thus asserting the meritorious defense of truth. Gillikin also challenged the amount of damages and the fact that a hearing was not held to determine the reasonableness of the $250,000 requested by Mattingly in the motion for default judgment. Gillikin argued that because the damages sought by Mattingly were not liquidated or for a sum certain, the trial court should have held a hearing on damages. See Allstate Ins. Co. v. Love (Ind. Ct. App. 2011) (holding that because damages were unliquidated—not a sum certain or able to be reduced to fixed rules and mathematical precision—trial court erroneously entered the $225,000 damages award along with the default judgment without holding a damages hearing); Stewart v. Hicks (Ind. Ct. App. 1979) (affirming, on the basis of T.R. 60(B)(8), trial court's setting aside of $50,000 award entered in a default judgment without a hearing where damages were unliquidated).

Given the meritorious defense, the magnitude of the damages award issued without a hearing, the promptness in which Gillikin sought to set aside the default judgment, and the lack of any demonstrated prejudice to Mattingly, we hold that the trial court abused its discretion by refusing to set aside the default judgment on equitable grounds under T.R. 60(B)(8). Accordingly, we reverse the trial court's order denying the motion to set aside the default judgment, instruct the trial court to vacate the default judgment, and remand for further proceedings before a different judicial officer, as requested by Gillikin.

{While we do not agree with Gillikin that Magistrate [Erin] Weaver was constitutionally required to sua sponte recuse herself, we observe that some of Magistrate Weaver's actions during the very brief hearing were problematic. She abruptly stopped Gillikin from presenting evidence related to excusable neglect, prevented inquiry into the reasonableness of the damages award, and conducted a sua sponte Google search of the alleged defamatory statement during the hearing.}

Nathan Vining represents Gillikin.

The post Indiana Court Sets Aside $250K Default Judgment in Lawyer's Libel Case Related to "Scathing Google Review" appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers