Adam Thierer's Blog, page 9

March 17, 2021

Video: Lessons from the “Hall of Fallen Giants”

Here’s a new animated explainer video that I narrated for the Federalist Society’s Regulatory Transparency Project. The 3-minute video discusses how earlier “tech giants” rose and fell as technological innovation and new competition sent them off to what the New York Times once appropriately called “The Hall of Fallen Giants.” It’s a continuing testament to the power of “creative destruction” to upend and reorder markets, even as many pundits insist that there’s no possibility change can happen.

This is an important lesson for us to remember today, as I noted in the recent editorial for The Hill about why, “Open-ended antitrust is an innovation killer“:

Those who worry about today’s largest tech giants becoming supposedly unassailable monopolies should consider how similar fears were expressed not so long ago about other tech titans, many of which we laugh about today. Just 14 years ago, headlines proclaimed that “MySpace Is a Natural Monopoly,” and asked, “Will MySpace Ever Lose Its Monopoly?” We all know how that “monopoly” ceased to exist.

At the same time, pundits insisted “Apple should pull the plug on the iPhone,” since “there is no likelihood that Apple can be successful in a business this competitive.” The smartphone market of that era was viewed as completely under the control of BlackBerry, Palm, Motorola and Nokia. A few years prior to that, critics lambasted the merger of AOL and TimeWarner as a new corporate “Big Brother” that would decimate digital diversity and online competition.

Accordingly, policymakers should be humble and recognize that, “it’s better to let rivalry and innovation emerge organically,” and only bring in the wrecking ball of heavy-handed antitrust regulation as a last resort, I argued. Technological change and entrepreneurialism has a way of upending and reordering markets when we least expect it. Just ask all those members of the Hall of Fallen Giants.

March 15, 2021

Skeptical Takes on Expansive Industrial Policy Efforts

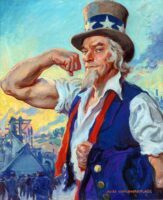

Industrial Policy is a red-hot topic once again with many policymakers and pundits of different ideological leanings lining up to support ambitious new state planning for various sectors — especially 5G, artificial intelligence, and semiconductors. A remarkably bipartisan array of people and organizations are advocating for government to flex its muscle and begin directing more spending and decision-making in various technological areas. They all suggest some sort of big plan is needed, and it is not uncommon for these industrial policy advocates to suggest that hundreds of billions will need to be spent in pursuit of those plans.

Industrial Policy is a red-hot topic once again with many policymakers and pundits of different ideological leanings lining up to support ambitious new state planning for various sectors — especially 5G, artificial intelligence, and semiconductors. A remarkably bipartisan array of people and organizations are advocating for government to flex its muscle and begin directing more spending and decision-making in various technological areas. They all suggest some sort of big plan is needed, and it is not uncommon for these industrial policy advocates to suggest that hundreds of billions will need to be spent in pursuit of those plans.

Others disagree, however, and I’ll be using this post to catalog some of their concerns on an ongoing basis. Some of the criticisms listed here are portions of longer essays, many of which highlight other types of steps that governments can take to spur innovative activities. Industrial policy is an amorphous term with many definitions of a broad spectrum of possible proposals. Almost everyone believes in some form of industrial policy if you define the term broadly enough. But, as I argued in a September 2020 essay “On Defining ‘Industrial Policy‘,” I believe it is important to narrow the focus of the term such that we can continue to use the term in a rational way. Toward that end, I believe a proper understanding of industrial policy refers to targeted and directed efforts to plan for specific future industrial outputs and outcomes.

The collection of essays below is merely an attempt to highlight some of the general concerns about the most ambitious calls for expansive industrial policy, many of which harken back to debates I was covering in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when I first started a career in policy analysis. During that time, Japan and South Korea were the primary countries of concern cited by industrial policy advocates. Today, it is China’s growing economic standing that is fueling calls for ambitious state-led targeted investments in “strategic” sectors and technologies. To a lesser extent, grandiose European industrial policy proposals are also prompting new US counter-proposals.

All this activity is what has given rise to many of the critiques listed below. If you have suggestions for other essays I might add to this list, please feel free to pass them along. FYI: There’s no particular order here.

Douglas Irwin, “Memo to the Biden administration on how to rethink industrial policy,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, October 2020.

The challenge for policymakers is to identify such industries without succumbing to the notion that every industry is vital to some public objective. For example, the goal of “economic security” is so broadly defined and open-ended that virtually every domestic producer could claim the need for government support on that basis. The risk is that ill-conceived government programs will encourage corrupt behavior in which industries benefit themselves without contributing to national welfare.

Jim Pethokoukis, “Will Biden’s embrace of industrial policy pay off?” AEI Blog, January 15, 2021.

The history of such efforts in advanced capitalist economies gives ample reason for skepticism about the effectiveness of such top-down government planning, from Japanese economic stagnation to the now-mothballed Concorde supersonic jet to France’s failed attempt to create a thriving tech sector. The Internet might seem like the exception that negates the rule, but what turned out to be a successful partnership of government and entrepreneurs didn’t arise out of some master plan from Washington. And what do even the smartest plans look like when filtered through the dodgy quality of American governance? Maybe as an excuse for cronyism and protectionism.

Adam Thierer & Connor Haaland, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” Discourse, March 11, 2021.

America needs to embrace its already vibrant venture capital market, the benefits of basic science and prize competitions, and a light-touch regulatory approach instead of gambling taxpayer dollars on grandiose industrial policy schemes that would likely become boondoggles.

Connor Haaland & Adam Thierer, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” Discourse, February 11, 2021.

Thus far, however, the Europeans don’t have much to show for their attempts to produce home-grown tech champions. Despite highly targeted and expensive efforts to foster a domestic tech base, the EU has instead generated a string of industrial policy failures that should serve as a cautionary tale for U.S. pundits and policymakers, who seem increasingly open to more government-steered innovation efforts.

Phil Levy & Christine McDaniel, “Does the U.S. Need a Vigorous Industrial Policy?” Discourse, February 16, 2021.

we are certainly hearing new enthusiasm these days about industrial policy. It seems to have proponents or converts on both sides of the aisle. This either means that a new consensus has emerged, or it means that the term is being used so loosely that it has lost its original meaning. I’ll go with the latter; it now means different things to different people.

Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip discussing why “The traditional skepticism toward industrial policy is well deserved.”

The traditional skepticism toward industrial policy is well deserved. Once Washington starts writing checks for semiconductors, other industries may get in line with the outcome determined more by political clout than economic merit. As in shipbuilding, the targeted companies may end up in perpetual need of federal protection and unable to compete internationally

David Ignatius, “The U.S. is quietly mobilizing its economy against China,” Washington Post, March 4, 2021.

The industrial policy the AI commission recommends could unlock talent and innovation. But if officials aren’t careful, government intervention could also afflict our best companies with the dead weight and dysfunction of our broken political system. We need government to spawn brainpower, not bureaucracy.

Veronique de Rugy, “Support for Industrial Policy is Growing,” AIER, January 18, 2020.

Looking at the federal government today tells me that the problems surrounding R&D programs in the past continue today, and will continue tomorrow, because they are simply a consequence of the normal functioning of government. It is hard to wish these problems away, even in the face of the private sector’s “imperfections.” Those arguing for more funding in R&D should proceed with caution.

Ben Reinhardt on concerns about The Endless Frontier Act

This bill is proposing to give money with risk-averse restrictions to a risk-averse organization (the NSF) to be dispersed among other risk-averse organizations (Universities) into a system with increasingly risk-averse incentives. Note that I’m not saying “it’s all fubar’d lets burn it to the ground!” but I am suggesting that instead of slamming on the accelerator, we should be asking “what would a tune-up and an oil change look like instead?”

Ryan Bourne, “Do Oren Cass’s Justifications for Industrial Policy Stack Up?” Cato Commentary, August 15, 2019.

Oren Cass asserts that markets cannot generally allocate resources efficiently by industry. Yet he provides no meaningful metrics to show this is the case, nor shows why his policies would deliver better outcomes. His two main claims about the benefits of a manufacturing sector — “stable employment” and “strong productivity growth” — are directly contradictory. A plethora of evidence suggests as countries’ get richer due to automation and technological improvements, they demand relatively more services, and so the industrial sector declines in employment terms.

Scott Lincicome, “Manufactured Crisis: ‘Deindustrialization, Free Markets, and National Security,” Cato Policy Analysis No. 907, January 27, 2021.

This skepticism—mostly absent from Washington—is indeed warranted: analyses of the U.S. manufacturing sector and the relationship between trade and national security, as well as the United States’ long and checkered history of security‐related protectionism, undermine the theoretical justifications for imposing protectionism and industrial policy in the name of national defense. Instead, open trade, freer markets, and global interdependence will in almost all cases produce better outcomes in terms of national security and, most importantly, preventing wars and other forms of armed conflict.

Don Boudreaux, “Suffixing Industrial Policy with ‘2.0’ Doesn’t Make It Credible,” AIER, Nov. 18, 2019.

Alberto Mingardi & Deirdre McCloskey, “Not the ‘Entrepreneurial State‘,” AIER, Nov. 2, 2020.

Should the US Follow China’s Lead on Industrial Policy?

In our latest feature for Discourse magazine, Connor Haaland and I explore the question, “Should the U.S. Copy China’s Industrial Policy?” We begin by noting that:

Calls for revitalizing American industrial policy have multiplied in recent years, with many pundits and policymakers suggesting that the U.S. should consider taking on Europe and China by emulating their approaches to technological development. The goal would be to have Washington formulate a set of strategic innovation goals and mobilize government planning and spending around them.

We continue on to argue that what most of these advocates miss is that:

China’s targeting efforts are often antithetical to both innovation and liberty, and involve plenty of red tape and bureaucracy. China has become a remarkably innovative country for many reasons, including its greater tolerance for risk-taking, even as the Chinese Communist Party continues to pump resources into strategic sectors. But most Chinese innovation is permissible only insomuch as it furthers the party’s objectives, a strategy the U.S. obviously wouldn’t want to copy.

We discuss the problems associated with some of those Chinese efforts as well as proposed US responses, like the recently released 756 page report from the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. The report takes an everything-and-the-kitchen-sink approach to state direction for new AI-related efforts and spending. While that report says the government now must “drive change through top-down leadership” in order to “win the AI competition that is intensifying strategic competition with China,” we argue that there could be some serious pitfalls with top-down, high price tag approaches.

Jump over to the Discourse site to read the full essay, as well as our previous essay, which asked, “Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?” These two essay build on the research Connor and I have been doing on global artificial intelligence policies in the US, China, and the EU. In a much longer forthcoming white paper, we explore both the regulatory and industrial policy approaches for AI being adopted in the US, China, and the EU. Stay tuned for more.

February 15, 2021

European Industrial Policy Follies

Over at Discourse magazine, Connor Haaland and I have an new essay (“Can European-Style Industrial Policies Create Tech Supremacy?”) examining Europe’s effort to develop national champion in a variety of tech sectors using highly targeted industrial policy efforts. The results have not been encouraging, we find.

Thus far, however, the Europeans don’t have much to show for their attempts to produce home-grown tech champions. Despite highly targeted and expensive efforts to foster a domestic tech base, the EU has instead generated a string of industrial policy failures that should serve as a cautionary tale for U.S. pundits and policymakers, who seem increasingly open to more government-steered innovation efforts.

We examine case studies in internet access, search, GPS, video services, and the sharing economy. We then explore newly-proposed industrial policy efforts aimed at developing their domestic AI market. We note how:

no amount of centralized state planning or spending will be able to overcome Europe’s aversion to technological risk-taking and disruption. The EU’s innovation culture generally values stability—of existing laws, institutions and businesses—over disruptive technological change. […]

There are no European versions of Microsoft, Google or Apple, even though Europeans obviously demand and consume the sort of products and services those U.S.-based companies provide. It’s simply not possible given the EU’s current regulatory regime.

It seems unlikely that Europe will have much better luck developing home-grown champions in AI and robotics using this same playbook. “American academics and policymakers with an affinity for industrial policy might want to consider a model other than Europe’s misguided combination of fruitless state planning and heavy-handed regulatory edicts,” we conclude.

Head over to Discourse to read the entire essay.

February 1, 2021

New Jurimetrics Article: “Soft Law in U.S. ICT Sectors: Four Case Studies”

After a slight delay, Jurimetrics has finally published my latest law review article, “Soft Law in U.S. ICT Sectors: Four Case Studies.” It is part of a major symposium that Arizona State University (ASU) Law School put together on “Governing Emerging Technologies Through Soft Law: Lessons For Artificial Intelligence” for the journal. I was 1 of 4 scholars invited to pen foundational essays for this symposium. Jurimetrics is a official publication of the American Bar Association’s Section of Science & Technology Law.

This report was a major undertaking that involved dozens of interviews, extensive historic research, several events and presentations, and then numerous revisions before the final product was released. The final PDF version of the journal article is attached.

Here is the abstract:

Traditional hard law tools and processes are struggling to keep up with the rapid pace of innovation in many emerging technologies sectors. As a result, policymakers in the United States rely increasingly on less formal “soft law” governance mechanisms to address concerns surrounding many newer technologies. This Article explores four case studies from different information technology areas where soft law mechanisms have already been utilized to address governance concerns. These four sectoral case studies include domain name management, content oversight, privacy policy, and cybersecurity matters. After considering the various soft law mechanisms used to address those issues, the Article concludes with some general thoughts about the effectiveness of those approaches and what lessons those case studies might hold for the use of soft law in other emerging technology sectors and contexts.

Thierer - Soft Law in ICT Sectors - Four Case Studies (2020)January 14, 2021

FCC rule makes it easier to self-provision home broadband

On January 7, with the Pai FCC winding down, the agency made an important rule change that gives US households more broadband options. Small, outdoor broadband antennas installed on private property will be shielded from “unreasonable” state and local restrictions and fees, much like satellite TV dishes are protected today. The practical effect is most consumers can install small broadband devices on their rooftops, on their balconies, or on short poles in their yards in order to bring broadband to their home and their neighbors’. The FCC decision was bipartisan and unanimous and will open up tens of millions of new installation sites for certain 5G small cells, WISP systems, outdoor WiFi, mesh network nodes, and other wireless devices.

Previously, satellite dish installation was protected from most fees and restrictions but most small broadband antennas were not.

Disparate treatment.

Disparate treatment.The rule change involved the FCC’s 20 year-old over-the-air-reception-device (OTARD) rules, which protect consumers from unreasonable local fees and restrictions when installing satellite TV dishes. The rules came about because in the 1990s states and cities often restricted or imposed fees on homeowners installing satellite TV dishes. Congress got involved and, circa 1998, the FCC created the OTARD rules, aka the “pizza box rules,” to protect the installation of TV dishes less than 1 meter diameter.

In recent years, homeowners and tenants increasingly want to install small, outdoor broadband antennas on their property to bring new services and competition to their neighborhood. However, they face many of the same problems satellite dish installers faced in the 1990s. From my comments (pdf) to the FCC in the proceeding:

For instance, a few years ago a woman in the Charlottesville, Virginia, area switched from cable to less expensive satellite TV service in order to save money after being laid off. She had a satellite dish installed in her front yard—the only place the dish could receive an adequate signal. A city zoning official sent her and about 30 neighbors letters informing them that their (OTARD rules-covered) satellite dishes were, per local ordinance, unpermitted accessory structures. Any homeowners who did not remove their dish faced fines of $250 per day.

Fortunately for the homeowners, the woman was familiar with the OTARD rules and informed the local officials of the FCC’s authority.38 After being informed of the FCC’s OTARD regulations, the city officials declined to enforce the local ordinance and agreed to revisit the ordinance for compliance with FCC rules.

Today, WISPs and other broadband providers face similar issues when trying to install antennas on private property. It’s hard to know how much the OTARD rules helped expand satellite TV penetration but it helped. The FCC rules coincided with the installation of 20-30 million small dishes on private property.

With the rules extended to broadband antennas, operators will have millions more low-cost siting options. One provider, Starry, wrote to the FCC that today “it takes on average 100 days to complete the permitting process for a single base station, which accounts for about 80% of the time that it spends in activating a site.” Starry says that with the January 2021 rule change, they’ll likely activate 25-30% more antenna sites in the next year, bringing a broadband option to 1 million additional households. Take projections with a grain of salt, but it’s clear the new rules will improve coverage and competition.

There are some exceptions. States and cities are able to restrict antenna installation if they can show a safety hazard or a historic preservation issue. Generally, however, the rules are protective of homeowners and tenants. The changes faced some opposition from cities, counties, and homeowners associations but it’s great to see a bipartisan and unanimous decision in the final days of Chairman Pai’s broadband expansion-focused tenure to give consumers more protection for installing and self-provisioning small broadband antennas.

January 11, 2021

Podcast: Tech Policy in the Biden Admin & 117th Congress

I wanted to bring to your attention this Federalist Society podcast discussion I hosted a few weeks ago on, “Tech Policy Under the Biden Administration and 117th Congress.” I was joined by Jennifer Huddleston, Director of Technology & Innovation Policy at the American Action Forum, and Blake Reid, Clinical Professor at the University of Colorado Law School.

We discussed key policy debates – such as antitrust and “Big Tech,” online speech and Section 230, and the race to 5G – and considered how the new presidential administration and Congress might approach innovation and the tech industry in 2021 and beyond. Note: You might also want to check out this earlier essay by Jennifer on, “5 Tech Policy Topics to Follow in the Biden Administration and 117th Congress.”

January 10, 2021

The End of Permissionless Innovation?

[This article originally appeared at Discourse on January 6, 2021.]

Time magazine recently declared 2020 “The Worst Year Ever.” By historical standards that may be a bit of hyperbole. For America’s digital technology sector, however, that headline rings true. After a remarkable 25-year run that saw an explosion of innovation and the rapid ascent of a group of U.S. companies that became household names across the globe, politicians and pundits in 2020 declared the party over.

“We now are on the cusp of a new era of tech policy, one in which the policy catches up with the technology,” says Darrell M. West of the Brookings Institution in a recent essay, “The End of Permissionless Innovation.” West cites the House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee’s October report on competition in digital markets—where it equates large tech firms with the “oil barons and railroad tycoons” of the Gilded Age—as the clearest sign that politicization of the internet and digital technology is accelerating.

It is hardly the only indication that America is set to abandon permissionless innovation and revisit the era of heavy-handed regulation for information and communication technology (ICT) markets. Equally significant is the growing bipartisan crusade against Section 230, the provision of the 1996 Telecommunications Act that shields “interactive computer services” from liability for information posted or published on their systems by users. No single policy has been more important to the flourishing of online speech or commerce than Sec. 230 because, without it, online platforms would be overwhelmed by regulation and lawsuits.

But now, long knives are coming out for the law, with plenty of politicians and academics calling for it to be gutted. Calls to reform or repeal Sec. 230 were once exclusively the province of left-leaning academics or policymakers, but this year it was conservatives in the White House, on Capitol Hill and at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) who became the leading cheerleaders for scaling back or eliminating the law. President Trump railed against Sec. 230 repeatedly on Twitter, and most recently vetoed the annual National Defense Authorization Act in part because Congress did not include a repeal of the law in the measure.

Meanwhile, conservative lawmakers in Congress such as Sens. Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz have used subpoenas, angry letters and heated hearings to hammer digital tech executives about their content moderation practices. Allegations of anti-conservative bias have motivated many of these efforts. Even Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas questioned the law in a recent opinion.

Other proposed regulatory interventions include calls for new national privacy laws, an “Algorithmic Accountability Act” to regulate artificial intelligence technologies, and a growing variety of industrial policy measures that would open the door to widespread meddling with various tech sectors. Some officials in the Trump administration even pushed for a nationalized 5G communications network in the name of competing with China.

This growing “techlash” signals a bipartisan “Back to the Future” moment, with the possibility of the U.S. reviving a regulatory playbook that many believed had been discarded in history’s dustbin. Although plenty of politicians and pundits are taking victory laps and giving each other high-fives over the impending end of the permissionless innovation era, it is worth considering what America will be losing if we once again apply old top-down, permission slip-oriented policies to the technology sector.

Permissionless Innovation: The Basics

As an engineering principle, permissionless innovation represents the general freedom to tinker and develop new ideas and products in a relatively unconstrained fashion. As I noted in a recent book on the topic, permissionless innovation can also describe a governance disposition or regulatory default toward entrepreneurial activities. In this sense, permissionless innovation refers to the idea that experimentation with new technologies and innovations should generally be permitted by default and that prior restraints on creative activities should be avoided except in those cases where clear and immediate harm is evident.

There is an obvious relationship between the narrow and broad definitions of permissionless innovation. When governments lean toward permissionless innovation as a policy default, it is likely to encourage freewheeling experimentation more generally. But permissionless innovation can sometimes occur in the wild, even when public policy instead tends toward its antithesis—the precautionary principle. As I noted in my latest book, tinkerers and innovators sometimes behave evasively and act to make permissionless innovation a reality even when public policy discourages it through precautionary restraints.

To be clear, permissionless innovation as a policy default has not meant anarchy. Quite the opposite, in fact. In the United States, over the past 25 years, no major federal agencies that regulate technology or laws that do so were eliminated. Indeed, most agencies grew bigger. But in spite of this, entrepreneurs during this period got more green lights than red ones, and innovation was treated as innocent until proven guilty. This is how and why social media and the sharing economy developed and prospered here and not in other countries, where layers of permission slips prevented such innovations from ever getting off the drawing board.

The question now is, how will the shift to end permissionless innovation as a policy default in the U.S. affect innovative activity here more generally? Economic historians Deirdre McCloskey and Joel Mokyr teach us that societal and political attitudes toward growth, risk-taking and entrepreneurialism have a powerful connection with the competitive standing of nations and the possibility of long-term prosperity. If America’s innovation culture sours on the idea of permissionless-ness and moves toward a precautionary principle-based model, creative minds will find it harder to experiment with bold new ideas that could help enrich the nation and improve the well-being of the citizenry—which is exactly why America discarded its old top-down regulatory model in the first place.

Why America Junked the Old Model

Perhaps the easiest way to put some rough bookends on the beginning and end of America’s permissionless innovation era is to date it to the birth and impending death of Sec. 230 itself. The enactment in 1996 of the Telecommunications Act was important, not only because it included Sec. 230, but also because the law created a sort of policy firewall between the old and new worlds of ICT regulation. The old ICT regime was rooted in a complex maze of federal, state and local regulatory permission slips. If you wanted to do anything truly innovative in the old days, you typically needed to get some regulator’s blessing first—sometimes multiple blessings.

The exception was the print sector, which enjoyed robust First Amendment protection from the time of the nation’s founding. Newspapers, magazines and book publishers were left largely free of prior restraints regarding what they published or how they innovated. The electronic media of the 20th century were not so lucky. Telephony, radio, television, cable, satellite and other technologies were quickly encumbered with a crazy quilt of federal and state regulations. Those restraints include price controls, entry restrictions, speech restrictions and endless agency threats.

ICT policy started turning the corner in the late 1980s after the old regulatory model failed to achieve its mission of more choice, higher quality and lower prices for media and communications. Almost everyone accepted that change was needed, and it came fast. The 1990s became a whirlwind of policy and technological change.

In the mid-1990s, the Clinton administration decided to allow open commercialization of the internet, which, until then, had mostly been a plaything for government agencies and university researchers. But it was the enactment of the 1996 telecommunications law that sealed the deal. Not only did the new law largely avoid regulating the internet like analog-era ICT, but, more importantly, it included Sec. 230, which helped ensure that future regulators or overzealous tort lawyers would not undermine this wonderful new resource.

A year later, the Clinton administration put a cherry on top with the release of its Framework for Global Electronic Commerce. This bold policy statement announced a clean break from the past, arguing that “the private sector should lead [and] the internet should develop as a market-driven arena, not a regulated industry.” Permissionless innovation had become the foundation of American tech policy.

The Results

Ideas have consequences, as they say, and that includes ramifications for domestic business formation and global competitiveness. While the U.S. was allowing the private sector to largely determine the shape of the internet, Europe was embarking on a very different policy path, one that would hobble its tech sector.

America’s more flexible policy ecosystem proved to be fertile ground for digital startups. Consider the rise of “unicorns,” shorthand for companies valued at $1+ billion. “In terms of the global distribution of startup success,” notes the State of the Venture Capital Industry in 2019, “the number of private unicorns has grown from an initial list of 82 in 2015 to 356 in Q2 2019,” and fully half of them are U.S.-based.

The United States is also home to the most innovative tech firms. Over the past decade, Strategy& (PricewaterhouseCooper’s strategy consulting business) has compiled a list of the world’s most innovative companies, based on R&D efforts and revenue. Each year that list is dominated by American tech companies. In 2013, 9 of the top 10 most innovative companies were based in the U.S., and most of them were involved in computing, software and digital technology. Global competition is intensifying, but in the most recent 2018 list, 15 of the top 25 companies are still U.S.-based giants, with Amazon, Google, Intel, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, Oracle and Cisco leading the way.

Meanwhile, European digital tech companies cannot be found on any such list. While America’s tech companies are household names across the European continent, most people struggle to name a single digital innovator headquartered in the EU. Permissionless innovation crushed the precautionary principle in the trans-Atlantic policy wars.

European policymakers have responded to the continent’s digital stagnation by doubling down on their aggressive regulatory efforts. The EU closed out 2020 with two comprehensive new measures (the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act), while the U.K. simultaneously pursued a new “online harms” law. Taken together, these proposals represent “the biggest potential expansion of global tech regulation in years,” according to The Wall Street Journal. The measures will greatly expand extraterritorial control over American tech companies.

Having decimated their domestic technology base and driven away innovators and investors, EU officials are now resorting to plugging budget shortfalls with future antitrust fines on U.S.-based tech companies. It has essentially been a lost quarter century for Europe on the information technology front, and now American companies are expected to pay for it.

Republicans Revive ‘Regulation-By-Raised-Eyebrow’

In light of the failure of Europe’s precautionary principle-based policy paradigm, and considering the threat now posed by the growing importance of various Chinese tech companies, one might think U.S. policymakers would be celebrating the competitive advantages created by a quarter century of American tech dominance and contemplating how to apply this winning vision to other sectors of the economy.

Alas, despite its amazing run, business and political leaders are now turning against permissionless innovation as America’s policy lodestar. What is most surprising is how this reversal is now being championed by conservative Republicans, who traditionally support deregulation.

President Trump also called for tightening the screws on Big Tech. For example, in a May 2020 Executive Order on “Preventing Online Censorship,” he accused online platforms of “selective censorship that is harming our national discourse” and suggested that “these platforms function in many ways as a 21st century equivalent of the public square.” Trump and his supporters put Google, Facebook, Twitter and Amazon in their crosshairs, accusing them of discriminating against conservative viewpoints or values.

The irony here is that no politician owes more to modern social media platforms than Donald Trump, who effectively used them to communicate his ideas directly to the American people. Moreover, conservative pundits now enjoy unparalleled opportunity to get their views out to the wider world thanks to all the digital soapboxes they now can stand on. YouTube and Twitter are chock-full of conservative punditry, and the daily list of top 10 search terms on Facebook is dominated consistently by conservative voices, where “the right wing has a massive advantage,” according to Politico.

Nonetheless, conservatives insist they still don’t get a fair shake from the cornucopia of new communications platforms that earlier generations of conservatives could have only dreamed about having at their disposal. They think the deck is stacked against them by Silicon Valley liberals.

This growing backlash culminated in a remarkable Senate Commerce Committee hearing on Oct. 28 in which congressional Republicans hounded tech CEOs and called for more favorable treatment of conservatives, and threatened social media companies with regulation if conservative content was taken down. Liberal lawmakers, by contrast, uniformly demanded the companies do more to remove content they felt was harmful or deceptive in some fashion. In many cases, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle were talking about the exact same content, putting the companies in the impossible position of having to devise a Goldilocks formula to get the content balance just right, even though it would be impossible to make both sides happy.

In the broadcast era, this sort of political harassment was known as the “regulation-by-raised-eyebrow” approach, which allowed officials to get around First Amendment limitations on government content control. Congressional lawmakers and regulators at the FCC would set up show trial hearings and use political intimidation to gain programming concessions from licensed radio and television operators. These shakedown tactics didn’t always work, but they often resulted in forms of soft censorship, with media outlets editing content to make politicians happy.

The same dynamic is at work today. Thus, when a firebrand politician like Sen. Josh Hawley suggests “we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared,” or when Sohrab Ahmari, the conservative op-ed editor at the New York Post, calls for the nationalization of Twitter, they likely understand these extreme proposals won’t happen. But such jawboning represents an easy way to whip up your base while also indirectly putting intense pressure on companies to tweak their policies. Make us happy, or else! It is not always clear what that “or else” entails, but the accumulated threats probably have some effect on content decisions made by these firms.

Whether all this means that Sec. 230 gets scrapped or not shouldn’t distract from the more pertinent fact: few on the political right are preaching the gospel of permissionless innovation anymore. Even tech companies and Silicon Valley-backed organizations now actively distance themselves from the term. Zachary Graves, head of policy at Lincoln Network, a tech advocacy organization, worries that permissionless innovation is little more than a “legitimizing facade for anarcho-capitalists, tech bros, and cynical corporate flacks.” He lines up with the growing cast of commentators on both the left and right who endorse a “Tech New Deal” without getting concrete about what that means in practice. What it likely means is a return to a well-worn regulatory playbook of the past that resulted in innovation stagnation and crony capitalism.

A More Political Future

Indeed, as was the case during past eras of permission slip-based policy, our new regulatory era will be a great boon to the largest tech companies. Many people advocate greater regulation in the name of promoting competition, choice, quality and lower prices. But merely because someone proclaims that they are looking to serve the public interest doesn’t mean the regulatory policies they implement will achieve those well-intentioned goals. The means to the end—new rules, regulations and bureaucracies—are messy, imprecise and often counterproductive.

Fifty years ago, the Nobel prize-winning economist George Stigler taught us that, “as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefits.” In other words, new regulations often help to entrench existing players rather than fostering greater competition. Countless experts since then have documented the problem of regulatory capture in various contexts. If the past is prologue, we can expect many large tech firms to openly embrace regulation as they come to see it as a useful way of preserving market share and fending off pesky new rivals, most of whom will not be able to shoulder the compliance burdens and liability threats associated with permission slip-based regulatory regimes.

True to form, in recent congressional hearings, Facebook head Mark Zuckerberg called on lawmakers to begin regulating social media markets. The company then rolled out a slick new website and advertising campaign inviting new rules on various matters. It is always easy for the king of the hill to call for more regulation when that hill is a mound of red tape of their own making—and which few others can ascend. It is a lesson we should have learned in the AT&T era, when a decidedly unnatural monopoly was formed through a partnership between company officials and the government.

Image Credit: Infrogmation/Wikimedia Commons

Many independent telephone companies existed across America before AT&T’s leaders cut sweetheart deals with policymakers that tilted the playing field in its favor and undermined competition. With rivals hobbled by entry restrictions and other rules, Ma Bell went on to enjoy more than a half century of stable market share and guaranteed rates of return. Consumers, by contrast, were expected to be content with plain-vanilla telephone services that barely changed. Some of us are old enough to remember when the biggest “innovation” in telephony involved the move from rotary-dial phones to the push-button Princess phone, which, we were thrilled to discover, came in multiple colors and had a longer cord.

In a similar way, the impending close of the permissionless innovation era signals the twilight of technological creative destruction and its replacement by a new regime of political favor-seeking and logrolling, which could lead to innovation stagnation. The CEOs of the remaining large tech companies will be expected to make regular visits to the halls of Congress and regulatory agencies (and to all those fundraising parties, too) to get their marching orders, just as large telecom and broadcaster players did in the past. We will revert to the old historical trajectory, which saw communications and media companies securing marketplace advantages more through political machinations than marketplace merit.

Will Politics Really Catch Up?

While permissionless innovation may be falling out of favor with elites, America’s entrepreneurial spirit will be hard to snuff out, even when layers of red tape make it riskier to be creative. If for no other reason, permissionless innovation still has a fighting chance so long as Congress struggles to enact comprehensive technology measures. General legislative dysfunction and profound technological ignorance are two reasons that Congress has largely become a non-actor on tech policy in recent years.

But the primary limitation on legislative meddling is the so-called pacing problem, which refers to the way technological innovation often outpaces the ability of laws and regulations to keep up. “I have said more than once that innovation moves at the speed of imagination and that government has traditionally moved at, well, the speed of government,” observed former Federal Aviation Administration head Michael Huerta in a 2016 speech.

DNA sequencing machine. Image Credit: Assembly/Getty Images

The same factors that drove the rise of the internet revolution—digitization, miniaturization, ubiquitous mobile connectivity and constantly increasing processing power—are spreading to many other sectors and challenging precautionary policies in the process. For example, just as “Moore’s Law” relentlessly powers the pace of change in ICT sectors, the “Carlson curve” now fuels genetic innovation. The curve refers to the fact that, over the past two decades, the cost of sequencing a human genome has plummeted from over $100 million to under $1,000, a rate nearly three times faster than Moore’s Law.

Speed isn’t the only factor driving the pacing problem. Policymakers also struggle with metaphysical considerations about how to define the things they seek to regulate. It used to be easy to agree what a phone, television or medical tracking device was for regulatory purposes. But what do those terms really mean in the age of the smartphone, which incorporates all of them and much more? “‘Tech’ is a very diverse, widely-spread industry that touches on all sorts of different issues,” notes tech analyst Benedict Evans. “These issues generally need detailed analysis to understand, and they tend to change in months, not decades.”

This makes regulating the industry significantly more challenging than it was in the past. It doesn’t mean the end of regulation—especially for sectors already encumbered by many layers of preexisting rules. But these new realities lead to a more interesting game of regulatory whack-a-mole: pushing down technological innovation in one way often means it simply pops up somewhere else. The continued rapid growth of what some call “the new technologies of freedom”—artificial intelligence, blockchain, the Internet of Things, etc.—should give us some reasons for optimism. It’s hard to put these genies back in their bottles now that they’re out.

This is even more true thanks to the growth of innovation arbitrage—both globally and domestically. Creators and capital now move fluidly across borders in pursuit of more hospitable innovation and investment climates. Recently, some high-profile tech CEOs like Elon Musk and Joe Lonsdale have relocated from California to Texas, citing tax and regulatory burdens as key factors in their decisions. Oracle, America’s second-largest software company, also just announced it is moving its corporate headquarters from Silicon Valley to Austin, just over a week after Hewlett Packard Enterprise said it too is moving its headquarters from California to Texas—in this case, Houston. “Voting with your feet” might actually still mean something, especially when it is major tech companies and venture capitalists abandoning high-tax, over-regulated jurisdictions.

Advocacy Remains Essential

But we shouldn’t imagine that technological change is inevitable or fall into the trap of thinking of it as a sort of liberation theology that will magically free us from repressive government controls. Policy advocacy still matters. Innovation defenders will need to continue to push back against the most burdensome precautionary policies, while also promoting reforms that protect entrepreneurial endeavors.

The courts offer us great hope. Groups like the Institute for Justice, the Goldwater Institute, the Pacific Legal Foundation and others continue to litigate successfully in defense of the freedom to innovate. While the best we can hope for in the legislative arena may be perpetual stalemate, these and other public interest law firms are netting major victories in courtrooms across America.

Sometimes court victories force positive legislative changes, too. For example, in 2015, the Supreme Court handed down North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission, which held that local government cannot claim broad immunity from federal antitrust laws when it delegates power to nongovernmental bodies, such as licensing boards. This decision made much-needed occupational licensing reform an agenda item across America. Many states introduced or adopted bipartisan legislation aimed at reforming or sunsetting occupational licensing rules that undermine entrepreneurship.

Even more exciting are proposals that would protect citizens’ “right to earn a living.” This right would allow individuals to bring suit if they believe a regulatory scheme or decision has unnecessarily infringed upon their ability to earn a living within a legally permissible line of work. Meanwhile, there have been ongoing state efforts to advance “right to try” legislation that would expand medical treatment options for Americans tired of overly paternalistic health regulations.

Perhaps, then, it is too early to close the book on the permissionless innovation era. While dark political clouds loom over America’s technological landscape, there are still reasons to believe the entrepreneurial spirit can prevail.

November 12, 2020

5 Tech Policy Topics to Follow in the Biden Administration and 117th Congress

In a five-part series at the American Action Forum, I presented prior to the 2020 presidential election the candidates’ positions on a range of tech policy topics including: the race to 5G, Section 230, antitrust, and the sharing economy. Now that the election is over, it is time to examine what topics in tech policy will gain more attention and how the debate around various tech policy issues may change. In no particular order, here are five key tech policy issues to be aware of heading into a new administration and a new Congress.

The Use of Soft Law for Tech Policy

In 2021, it is likely America will still have a divided government with Democrats controlling the White House and House of Representatives and Republicans expected to narrowly control the Senate. The result of a divided government, particularly between the two houses of Congress, will likely be that many tech policy proposals face logjams. The result will likely be that many of the questions of tech policy lack the legislation or hard law framework that might be desired. As a result, we are likely to continue to see “soft law”—regulation by various sub-regulatory means such as guidance documents, workshops, and industry consultations—rather than formal action. While it appears we will see more formal regulatory action from the administrative state as well in a Biden Administration, these actions require quite a process through comments and formal or informal rulemaking. As technology continues to accelerate, many agencies turn to soft law to avoid “pacing problems” where policy cannot react as quickly as technology and rules may be outdated by the time they go into effect.

A soft law approach can be preferable to a hard law approach as it is often able to better adapt to rapidly changing technologies. Policymakers in this new administration, however, should work to ensure that they are using this tool in a way that enables innovation and that appropriate safeguards ensure that these actions do not become a crushing regulatory burden.

Return of the Net Neutrality Debate

One key difference between President Trump and President-elect Biden’s stances on tech policy concerns whether the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) should categorize internet service providers (ISPs) as Title II “common carrier services,” thereby enabling regulations such as “net neutrality” that places additional requirements on how these service providers can prioritize data. President-elect Biden has been clear in the past that he favors reinstating net neutrality.

The imposition of this classification and regulations occurred during the Obama Administration and the FCC removed both the classification under Title II and the additional regulations for “net neutrality” during the Trump Administration. Critics of these changes made many hyperbolic claims at the time such as that Netflix would be interrupted or that ISPs would use the freedom in a world without net neutrality to block abortion resources or pro-feminist groups. These concerns have proven to be misguided. If anything, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown the benefits to building a robust internet infrastructure and expanded investment that a light-touch approach has yielded.

It is likely that net neutrality will once again be debated. Beyond just the imposition of these restrictions, a repeated change in such a key classification could create additional regulatory uncertainty and deter or delay investment and innovation in this valuable infrastructure. To overcome such concerns, congressional action could help fashion certainty in a bipartisan and balanced way to avoid a back-and-forth of such a dramatic nature.

Debates Regarding Sharing Economy Providers’ Classification as Independent Contractors

California voters passed Proposition 22 undoing the misguided reclassification of app-based service drivers as employees rather than independent contractors under AB5; during the campaign, however, President-elect Biden stated that he supports AB5 and called for a similar approach nationwide. Such an approach would make it more difficult on new sharing economy platforms and a wide range of independent workers (such as freelance journalists) at a time when the country is trying to recover economically.

Changing classifications to make it more difficult to consider service providers as independent contractors makes it less likely that platforms such as Fiverr or TaskRabbit could provide platforms for individuals to offer their skills. This reclassification as employees also misunderstands the ways in which many people choose to engage in gig economy work and the advantages that flexibility has. As my AAF colleague Isabel Soto notes, the national costs of a similar approach found in the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act “could see between $3.6 billion and $12.1 billion in additional costs to businesses” at a time when many are seeking to recover during the recession. Instead, both parties should look for solutions that continue to allow the benefits of the flexible arrangements that many seek in such work, while allowing for creative solutions and opportunities for businesses that wish to provide additional benefits to workers without risking reclassification.

Shifting Conversations and Debates Around Section 230

Section 230 has recently faced most of its criticism from Republicans regarding allegations of anti-conservative bias. President-elect Biden, however, has also called to revoke Section 230 and to set up a taskforce regarding “Online Harassment and Abuse.” While this may seem like a positive step to resolving concerns about online content, it could also open the door to government intervention in speech that is not widely agreed upon and chip away at the liability protection for content moderation.

For example, even though the Stop Enabling Sex Trafficking Act was targeting the heinous crime of sex trafficking (which was already not subject to Section 230 protection) was aimed at companies such as Backpage where it was known such illegal activity was being conducted, it has resulted in legitimate speech such as Craigslist personal ads being removed and companies such as Salesforce being subjected to lawsuits for what third parties used their product for. A carveout for hate speech or misinformation would only pose more difficulties for many businesses. These terms to do not have clearly agreed-upon meanings and often require far more nuanced understanding for content moderation decisions. To enforce changes that limit online speech even on distasteful and hateful language in the United States would dramatically change the interpretation of the First Amendment that has ruled such speech is still protected and would result in significant intrusion by the government for it to be truly enforced. For example, in the UK, an average of nine people a day were questioned or arrested over offensive or harassing “trolling” in online posts, messages, or forums under a law targeting online harassment and abuse such as what the taskforce would be expected to consider.

Online speech has provided new ways to connect, and Section 230 keeps the barriers to entry low. It is fair to be concerned about the impact of negative behavior, but policymakers should also recognize the impact that online spaces have had on allowing marginalized communities to connect and be concerned about the unintended consequences changes to Section 230 could have.

Continued Antitrust Scrutiny of “Big Tech”

One part of the “techlash” that shows no sign of diminishing in the new administration or new Congress is using antitrust to go after “Big Tech.” While it remains to be seen if the Biden Department of Justice will continue the current case against Google, there are indications that they and congressional Democrats will continue to go after these successful companies with creative theories of harm that do not reflect the current standards in antitrust.

Instead of assuming a large and popular company automatically merits competition scrutiny or attempting to utilize antitrust to achieve policy changes for which it is an ill-fitted tool, the next administration should return to the principled approach of the consumer welfare standard. Under such an approach, antitrust is focused on consumers and not competitors. In this regard, companies would need to be shown to be dominant in their market, abusing that dominance in some ways, and harming consumers. This approach also provides an objective standard that lets companies and consumers know how actions will be considered under competition law. With what is publicly known, the proposed cases against the large tech companies fail at least one element of this test.

There will likely be a shift in some of the claimed harms, but unfortunately scrutiny of large tech companies and calls to change antitrust laws to go after these companies are likely to continue.

Conclusion

There are many other technology and innovation issues the next administration and Congress will see. These include not only the issues mentioned above, but emerging technologies like 5G, the Internet of Things, and autonomous vehicles. Other issues such as the digital divide provide an opportunity for policymakers on both sides of the aisle to come together and have a beneficial impact and think of creative and adaptable solutions. Hopefully, the Biden Administration and the new Congress will continue a light-touch approach that allows entrepreneurs to engage with innovative ideas and continues American leadership in the technology sector.

October 17, 2020

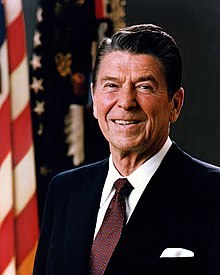

A Good Time to Re-Read Reagan’s Fairness Doctrine Veto

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation. Here’s the key line:

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation. Here’s the key line:

History has shown that the dangers of an overly timid or biased press cannot be averted through bureaucratic regulation, but only through the freedom and competition that the First Amendment sought to guarantee.

That wisdom is just as applicable today when some conservatives suggest that government intervention is needed to address what they regardless as “bias” or “unfair” treatment on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or whatever else. Ignoring the fact that such meddling would likely violate property rights and freedom of contract — principles that most conservatives say they hold dear — efforts to empower the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, or other regulators would be hugely misguided on First Amendment grounds.

President Reagan understood that there was a better way to approach these issues that was rooted in innovation and First Amendment protections. Here’s hoping that conservatives remember his sage advice. Read his entire veto message here.

Additional Reading:

“FCC’s O’Rielly on First Amendment & Fairness Doctrine Dangers“

“Sen. Hawley’s Radical, Paternalistic Plan to Remake the Internet“

“How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality“

“Sen. Hawley’s Moral Panic Over Social Media“

“The White House Social Media Summit and the Return of ‘Regulation by Raised Eyebrow’“

“The Not-So-SMART Act“

“The Surprising Ideological Origins of Trump’s Communications Collectivism“

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower