Adam Thierer's Blog, page 13

May 6, 2020

“Human Needs Are Breaking Down Yesterday’s Precautionary Approaches”

I really liked this new essay, “Innovation is thriving in the fight against Covid-19,” by Norman Lewis over at Spiked, a UK-based publication. In it, he makes several important points similar to themes discussed in my book launch essay last week (“Evasive Entrepreneurialism and Technological Civil Disobedience in the Midst of a Pandemic.”) Lewis begins by noting that:

There is nothing like a crisis to concentrate the mind. And the Covid-19 catastrophe has certainly done this. It has speeded up latent trends and posed new questions. The issue of our technologically informed capacity to solve problems is just one example.

He continues on to argue:

a crisis like Covid-19 will necessarily pose new urgent questions that could not have been anticipated. New initiatives will rise to meet these. Pre-existing skills, knowledge, technologies and attitudes will always be the starting point of new problem-solving quests. Where and how we focus attention will, in part, be based on prior cultural assumptions and existing technologies, and also on the novelty of the problem to be solved.

Lewis discusses how innovative minds are pushing back against archaic regulatory barriers, business models and government regulations. As he nicely summarizes:

Unimagined solutions are being pushed while a more open attitude towards experimentation, risk-taking and side-stepping onerous and costly regulation is starting to emerge. Human needs are breaking down yesterday’s precautionary approaches.

That last line really resonated with me because it’s a major theme that runs throughout my new book, “Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance: How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments.” As I summarized in my book launch essay:

Eventually, people take notice of how regulators and their rules encumber entrepreneurial activities, and they act to evade them when public welfare is undermined. Working around the system becomes inevitable when the permission society becomes so completely dysfunctional and counterproductive.

This was happening before the coronavirus outbreak, but the crisis has supercharged this phenomenon. Evasive entrepreneurs are taking advantage of the growth of new devices and platforms that let citizens circumvent (or perhaps just ignore) public policies that limit innovative efforts. These can include common tools like smartphones, computers, and various new interactive platforms, as well as more specialized technologies like cryptocurrencies, private drones, immersive technologies (like virtual reality), 3D printers, the “Internet of Things,” and sharing economy platforms and services. But that list just scratches the surface and the public is increasingly using these new technological capabilities to assert themselves and push back against laws and regulations that defy common sense and hold back progress.

Lawmakers and regulators need to consider a balanced response to evasive entrepreneurialism that is rooted in the realization that technology creators and users are less likely to seek to evade laws and regulations when public policies are more in line with common sense. Yesterday’s heavy-handed approaches that are rooted in the Precautionary Principle will need to be reformed to make sure progress can happen.

Read my book to find out more!

Biased AI is More Than a Technical Problem: Building a Process-oriented Policy Approach to AI Governance

[Co-authored with Walter Stover]

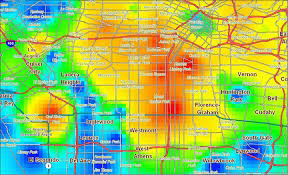

Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems have grown more prominent in both their use and their unintended effects. Just last month, LAPD announced that they would end their use of a predicting policing system known as PredPol, which had sustained criticism for reinforcing policing practices that disproportionately affect minorities. Such incidents of machine learning algorithms producing unintentionally biased outcomes have prompted calls for ‘ethical AI’. However, this approach focuses on technical fixes to AI, and ignores two crucial components of undesired outcomes: the subjectivity of data fed into and out of AI systems, and the interaction between actors who must interpret that data. When considering regulation on artificial intelligence, policymakers, companies, and other organizations using AI should therefore focus less on the algorithms and more on data and how it flows between actors to reduce risk of misdiagnosing AI systems. To be sure, applying an ethical AI framework is better than discounting ethics all together, but an approach that focuses on the interaction between human and data processes is a better foundation for AI policy.

The fundamental mistake underlying the ethical AI framework is that it treats biased outcomes as a purely technical problem. If this was true, then fixing the algorithm is an effective solution, because the outcome is purely defined by the tools applied. In the case of landing a man on the moon, for instance, we can tweak the telemetry of the rocket with well-defined physical principles until the man is on the moon. In the case of biased social outcomes, the problem is not well-defined. Who decides what an appropriate level of policing is for minorities? What sentence lengths are appropriate for which groups of individuals? What is an acceptable level of bias? An AI is simply a tool that transforms input data into output data, but it’s people that give meaning to data at both steps in context of their understanding of these questions and what appropriate measures of such outcomes are.

The Austrian school of economics is well-suited to helping us grapple with these kinds of less well-defined problems. Austrian economists levied a similar critique against mainstream economics, which treated economic outcomes as a technical problem to be solved with specific technical decisions. The Austrians stressed a principle of methodological individualism, which holds that socioeconomic outcomes are ultimately the products of individual decisions, and cannot be acted on directly by technocratic policymakers. Methodological individualism involves the recognition that individuals drive outcomes in two primary aspects: subjective interpretation of their environment, and through interaction with each other and that same environment. We can sum up application of these two aspects to AI systems in two questions: who gets the data, and where does the data go?

It matters who gets the data because the necessity of subjective interpretation will lead different people to reach separate conclusions about the same data. As an example, a set of data on financial variables such as defaults and debt repayment frequency combined with personal characteristics such as race and geographic locations may lead one person to label African-Americans as larger credit risks. Other individuals reading the same data, however, may arrive at a different conclusion: the patterns in this data stem from structural racism that has suppressed income of African American households compared to other households, and do not indicate that they are inherently riskier. The first interpretation would result in biased outcomes from an AI system used to generate predictions of credit risk based on that data, whereas the second interpretation might actually result in beneficial outcomes; for instance, an agency might offer with more lenient terms to these individuals.

The second question of where data goes depends on the interaction of individuals with each other and their environment, which drives the flow of data and also determines how that data is acted upon. In her book Weapons of Math Destruction, Cathy O’Neil offers a perfect example of this when analyzing what went wrong with the LAPD’s use of PredPol, which took in data on past crimes and used it to predict the geographic location of new crimes. Police forces took this data and increased their presence in hot spots of predicted crime, which resulted in a positive feedback loop of more crime data originating in that area (because of increased interaction between police officers and residents of that neighborhood in the form of increased arrests) generating more predictions of crime, leading to over-policing of minority groups. Ultimately, the data went to a police department that unintentionally increased arrests of minority groups.

Together, the subjectivity of data and the importance of interaction get at a core insight of Austrian economics that directly follows the principle of methodological individualism: context matters. If how data is interpreted and used differs from person to person, then the flows of data matter in who gets the data first and how they use it, potentially transforming the data before sending it on. Thinking along these lines shifts us away from focusing on building better, more ethical AI, and more towards trying to better understand the dynamics of data within a system: who is selecting which data to feed into an AI, what data the AI then generates, and most importantly, how that data is then acted upon and by whom. If we don’t take these matters into consideration, we risk myopically focusing on fixes to the AI that will not change outcomes. In the case of PredPol, for example, the AI could have been completely transparent, but the outcome would have been the same because of how police officers were acting on the output data according to their institutional context.

Some experts are already calling for more process-oriented AI governance approaches, including the EU’s High-Level Expert Group on AI and professional services network KPMG. Carolyn Herzog, general counsel and chair of an ethics working group, comes close to the approach we are advocating in stressing that “…data is the lifeblood of AI,” and that we must pay attention to “…issues of how that data is being collected, how it is being used, and how it is being safeguarded.” However, at present, this data-oriented approach is not represented clearly in U.S. policy. Recent AI policy movements, including ethical principles released by the Department of Defense and the Office of Management and Budget’s AI Guidelines, are a good first step but still emphasize the technology more than the data flows, and are limited to the government’s use of AI. Principle 9 of the guidelines, for instance, notes the importance of having controls to ensure “…confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the information stored, processed, and transmitted by AI systems,” but does not extend this to explicitly consider how the data is used after being transmitted.

Moreover, these proposals do not coherently lay out the relationship between data and AI outcomes because they do not give enough emphasis on where data goes and how it is used in context after being transmitted from the AI system. Returning to our earlier point, interactions matter. Take PredPol as an example. Even if we know how data was being collected, stored, and used by PredPol, and by the police department, these two pieces in isolation are not enough to understand the emergent outcome that results from the interaction between these two organizations. The critical driver is the feedback loop that emerges because of the data flows back and forth between PredPol and the police department. Current policy proposals risk overlooking this class of emergent AI outcomes by narrowly focusing on the AI and data practices of just one organization, rather than explicitly drawing our attention to how data circulates in the wider data ecosystem.

What’s needed is a process-oriented, systemic policy approach focused not just on AI, but how data is interpreted and used in context by individuals and organizations on the ground, and how these parties interact with each other. The NTIA would be a good convener for drafting this framework given their success in leading a multi-stakeholder process to build a framework for enhancing cybersecurity. NTIA can use the AI Now Institute’s algorithmic impact assessment as a blueprint. By building a voluntary framework for AI outcomes, the NTIA can serve a dual purpose. First, it can help ease worries over how to stay compliant with best practices; Second, it can help organizations safeguard against unwanted outcomes of AI systems, and more effectively identify and correct problems that do arise instead of depending on outside forensic data analysis after the fact. NTIA can help establish a common language of AI systems between public and private entities that gives concrete steps organizations can take to avoid these outcomes.

April 29, 2020

Video: Launch Event for “Evasive Entrepreneurs” Book

Here’s yesterday’s full launch event video for the release of my new book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance: How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments. My thanks to Matthew Feeney, Director of the Project on Emerging Technologies at the Cato Institute, for hosting the discussion and sorting through audience questions. The video is below and some of the topics we discussed are listed down below:

* innovation culture

* charter cities, innovation hubs & competitive federalism

* the pacing problem

* technological determinism

* innovation arbitrage

* existential risk

* the Precautionary Principle vs. Permissionless Innovation

* responsible innovation

* drones, facial recognition & surveillance tech

* why privacy & cybersecurity bills never pass

* regulatory accumulation

* applying Moore’s Law to government

* technological civil disobedience

* 3D printing

* biohacking & the “Right to Try” movement

* technologies of resistance

* “born free” technologies vs. “born in captivity” tech

* regulatory capture

* agency threats & “regulation by raised eyebrow”

* soft law vs. hard law

* autonomous systems & “killer robots”!

April 28, 2020

Evasive Entrepreneurialism and Technological Civil Disobedience in the Midst of a Pandemic

[Originally published on the Cato Institute blog.]

A pandemic is no time for bad governance. As the COVID-19 crisis intensified, bureaucrats and elected officials slumbered. Government regulations prevented many in the private sector from helping with response efforts. The result was a sudden surge of evasive entrepreneurialism and technological civil disobedience. With institutions and policies collapsing around them, many people took advantage of cutting‐edge technological capabilities to evade public policies that were preventing practical solutions from emerging.

A pandemic is no time for bad governance. As the COVID-19 crisis intensified, bureaucrats and elected officials slumbered. Government regulations prevented many in the private sector from helping with response efforts. The result was a sudden surge of evasive entrepreneurialism and technological civil disobedience. With institutions and policies collapsing around them, many people took advantage of cutting‐edge technological capabilities to evade public policies that were preventing practical solutions from emerging.

Examples were everywhere. Distilleries started producing hand sanitizers to address shortages while average folks began sharing do‐it‐yourself sanitizer recipes online. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) looked to modify hand sanitizer guidelines quickly to allow for it, but few really cared because those rules weren’t going to stop them. Gray markets in face masks, medical face shields, and respirators developed. Some people and organizations worked together to make medical devices using off‐the‐shelf hardware and open source software. More simply, others just fired up sewing machines to make masks—and then, faced with an emerging public health consensus, the guidance from the federal government shifted dramatically: where formerly ordinary people were instructed not to buy or use masks, within a matter of days, the policy reversed, and all were encouraged to make and use cloth protective masks.

Meanwhile, doctors and nurses started “writing the playbook for treating coronavirus patients on the fly” by improvising treatments and then sharing them on social media. A few doctors even converted breathing machines to ventilators themselves using 3-D printed parts to address shortages for their patients even though the FDA had not yet authorized it.

Social media sites were also suddenly filled with discussions about how average people might come together to build tools or share information to assist with virus testing or treatments. A 17‐year‐old used his coding skills to build one of the most popular coronavirus‐tracking websites in the world (ncov2019.live) after noticing how hard it was to use government sites. And two high school science teachers in Tennessee set up testing operations in their school lab to help reduce testing time in their area.

Meanwhile, journalists and columnists like the Wall Street Journal’s Andy Kessler cheered on such activity, encouraging the public to “innovate from your couch.” Modern digital technologies and platforms that had been pariahs and the target of a regulatory‐minded “techlash” just a few months earlier suddenly became essential public services that were showered with praise for helping people cope with social distancing and the solitude associated with shelter‐in‐place requirements. Headlines in major media outlets explained how “Facebook Is More Trustworthy than the President” and “Twitter Is Making the Coronavirus World a Better Place.”

Philanthropists like Bill Gates were also funding their own solutions. The former Microsoft founder and CEO pointed out that, in an effort to find testing solutions and vaccines, private groups like his Gates Foundation could likely mobilize faster than governments. Gates likely had grown frustrated with government responses after a Seattle‐based lab that the Gates Foundation funded figured out an effective way to test for coronavirus, only to be blocked from expanding it by over‐cautious federal bureaucrats. Frustrated by federal intransigence, that Seattle lab started testing for COVID-19 anyway to prove they indeed had an effective test. Commenting on the case study, the New York Times expressed exasperation about “how existing regulations and red tape—sometimes designed to protect privacy and health—have impeded the rapid rollout of testing nationally.”

Wait, Isn’t All This Illegal?

What is interesting about all these examples of bottom‐up innovation and evasive entrepreneurialism is that they are remarkably inspiring, but also mostly illegal. Almost all these activities butted up against longstanding regulations governing medical devices, practices, or therapies. Some of those rules are enforced by large and powerful federal bureaucracies like the FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Others take the form of state‐based occupational licensing limitations or certificate‐of‐need laws, which require healthcare providers to first obtain permission before they open or expand their facilities or services. This crazy quilt of medical laws and regulations accumulated steadily over time, creating what constitutional scholar Timothy Sandefur calls a “permission society,” which values proceduralism and conformity over practicality and common sense.

Eventually, however, the mountains of red tape that the permission society is built upon start to collapse under their own weight. Laws and agencies that previously commanded obedience are now viewed as an opaque, ossified, and confusing morass of one‐size‐fits‐all mandates, prohibitions, and penalties that actually undermine the very health goals they were put in place to achieve. Suddenly, headlines in every major newspaper screamed of how, as it pertained to virus testing procedures, “The Government Failed” (Wall Street Journal) because of “Flawed Tests, Red Tape and Resistance” (Washington Post) and this resulted in “The Lost Month” (New York Times) in the United States.

Eventually, people take notice of how regulators and their rules encumber entrepreneurial activities, and they act to evade them when public welfare is undermined. Working around the system becomes inevitable when the permission society becomes so completely dysfunctional and counterproductive.

Technological Empowerment vs. the Status Quo

What’s going on here, and what lessons can we derive from it?

In a new Cato Institute book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance, I document how the sort of behavior we have recently witnessed was growing rapidly even before the COVID-19 crisis. In many different contexts, evasive entrepreneurs—innovators who don’t always conform to social or legal norms—are using new technological capabilities to circumvent traditional regulatory systems. They at least want to put pressure on public policymakers to reform or selectively enforce laws and regulations that are outmoded, inefficient, or counterproductive.

Evasive entrepreneurs rely on a strategy of permissionless innovation in both the business world and the political arena. They push back against the permission society by creating exciting new products and services without always receiving the blessing of public officials before doing so. While evasive entrepreneurialism has always been with us to some extent, many of the responses to the pandemic would not have been possible even just a few decades ago. Recent advancements have supercharged in a more technologically empowered world of information abundance and decentralized, inexpensive tools.

As I show in the book, evasive entrepreneurs are taking advantage of the growth of what we might think of as technologies of freedom or resistance. These are devices and platforms that let citizens circumvent (or perhaps just ignore) public policies that limit their liberty or freedom to innovate or to enjoy the fruits of innovation. These can include common tools like smartphones, computers, and various new interactive platforms, as well as more specialized technologies like cryptocurrencies, private drones, immersive technologies (like virtual reality), 3D printers, the “Internet of Things,” and sharing economy platforms and services. But that list just scratches the surface. When the public uses tools such as these to explicitly evade public policies on moral grounds because they find then offensive, illogical, or perhaps just annoying, we can think of that as technological civil disobedience.

Common Sense Prevails

Evasive entrepreneurialism and technological civil disobedience accelerated during the pandemic because both the practicality and morality of government policies came into question in stark fashion. The first month of the crisis witnessed “a torrent of governmental incompetence that is breathtaking in scale,” my Mercatus colleague Scott Sumner argues. “There are regulations so bizarre that if put in a novel no one would believe them,” he notes. “In contrast, the private sector has reacted fairly well, and has been far ahead of the government in most areas.”

Indeed, the pandemic has been a stress test for our institutions, and many of them have failed it. Confusing rules and inflexible agencies that should have been reformed years ago were suddenly exposed and judged harshly. Philip K. Howard, founder of Common Good, says that “Covid‐19 is the canary in the bureaucratic mine.” Bloated bureaucracies and overbearing regulatory systems, he argues, have created a “toxic atmosphere that silenced common sense” and managed to “institutionalize failure.” Cato’s Paul Matzko has documented how the FDA has been particularly guilty of blocking sensible forms of progress on simple things like face mask production or distribution.

While countless others lambasted the practical failures of our institutions, the morality of government policies was also coming into focus. Why should citizens have their innovative efforts to help others stifled at seemingly every juncture? Must we really follow the law when it undercuts the basic human need to care for others and ourselves?

These are the issues addressed in my new book, which explains the practical reasons why evasive entrepreneurialism is on the rise and then provides a moral defense of it. When innovators and average citizens use tools and technological capabilities to pursue a living, enjoy new experiences, or improve the human condition, they often disrupt legal or social norms in the process. That is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, evasive entrepreneurialism can transform our society for the better because it can help expand the range of life‐enriching (and often life‐saving) innovations. Evasive entrepreneurialism can help citizens pursue lives of their own choosing—both as creators looking for the freedom to earn a living and as individuals looking to discover and enjoy important new goods and services.

Defending evasive entrepreneurialism is easy after it occurs, but few defend it before or as it is happening. I argue in the book that the freedom to innovate is essential to human betterment—for each of us individually and for civilization as a whole—and that freedom deserves to be taken more seriously today. The COVID-19 pandemic has made this more apparent than ever before.

There are few things more human than acts of invention. At its root, innovation involves efforts to discover new and better ways of solving practical human needs and wants. People have a right to innovate and create technologies because they possess a more general right to take steps to improve their lot in life and the lives of others around them. When misguided or archaic government programs and policies blocked that potential during the pandemic, people began ignoring or evading them. That was both practically sensible and morally justifiable.

Innovation as the New Checks and Balances

By extension, the response to the pandemic has proven the second thesis set forth in my book: Evasive entrepreneurialism and technologically enabled civil disobedience can actually help us improve government by keeping public policies fresh, sensible, and in line with common sense and the consent of the governed. Evasiveness and technological disruption can act as a sort of relief valve or circuit breaker to counteract negative pressures in the system before things break down completely. By challenging legislators and regulators to reevaluate the wisdom of their policies, evasive entrepreneurs can help us break political logjams and force governments to become more adaptive and accountable.

The proof is in the pudding. As the crisis unfolded, agencies at the federal, state, and local levels were forced to suspend hundreds of regulations that were clearly undermining helpful responses. These “rule departures” would not have been necessary if governments had engaged in periodic spring cleanings earlier. When COVID-19 hit, it became essential to suspend or repeal hundreds of misguided old rules that clearly undermined public health. The only question now is whether those inefficient, counterproductive policies will be put back on the books to do harm again in the next crisis.

But even before the current crisis, rule departures by government actors were becoming more common because even government officials could no longer understand their own rules. Just as private citizens have increasingly resorted to evasive techniques to get things done, many regulatory agencies have given up trying to “go by the book” themselves because endless regulatory accumulation has made it impossible to understand what the law means.

My book documents many cases of public officials essentially ignoring their own policies and making up governance solutions as they go along. This is another sign of profound institutional failure, yet it should also give us some hope that even policymakers themselves now realize that government cannot just grow forever without breaking down at some point. The need for comprehensive reform is now abundantly clear, and the pandemic has moved the so‐called “Overton Window” (i.e., the acceptable range of possible policy reforms) on many fronts.

A New Approach to Governance

Policymakers need a new approach for technological governance that is more in line with modern realities. Flexibility and humility will be essential. Regulators do not need to throw out the old rulebooks altogether, though. Some precautionary rules still make sense, particularly in cases involving extreme risk. But why not embrace the entrepreneurial spirit of the citizenry and allow more experimental trials, flexible testing procedures, and perhaps even prizes for particularly innovative ideas?

When enforcing the rules that remain on the books, policymakers should also consider targeted waivers and ex post regulatory reviews as opposed to ex ante regulatory prohibitions on any and all evasive innovations. Liability rules can also be tweaked so innovators do not have to live in constant fear of getting sued for trying to make the world a better place. Finally, post‐market monitoring and recall notices can also be used to ensure flexible experiments have some regulatory guardrails.

But shutting down creative solutions and unique thinking simply because they run counter to some crusty old rulebook is never the right response. We should view evasive entrepreneurialism as an important part of a broader discovery process that incorporates the profound importance of ongoing, decentralized, trial‐and‐error experimentation to the process of societal learning and improvement. Lawmakers should find a way to accommodate a little more outside‐the‐box thinking and innovating—and not just when our lives are on the line.

Additional Reading

read the opening chapter of the book

watch the event launch video

10 Highlights from the Book

13 Key Terms from the Book

5 innovation policy scholars who inspired this book

“Innovation & the Precautionary Principle” (AIER essay)

“Congress as a Non-Actor in Tech Policy” (Medium essay)

“Evasive Entrepreneurs” – 13 Key Terms from the Book

My latest book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments, is now live. Here’s the launch essay and online launch event. Also, here’s a summary of 10 major arguments advanced in the book. I will have more to say about the book in coming weeks, but here is a list of 13 key terms discussed in the text. This list appears at the end of the introduction to the book:

Compliance paradox: The situation in which heightened legal or regulatory efforts fail to reverse unwanted behavior and instead lead to increased legal evasion and additional enforcement problems.

Demosclerosis: Growing government dysfunction brought on by the inability of public institutions to adapt to change, especially technological change.

Evasive entrepreneurs: Innovators who do not always conform to social or legal norms.

Free innovation: Bottom-up, noncommercial forms of innovation that often take on an evasive character. Free innovation is sometimes called “grassroots” or “household” innovation or “social entrepreneurialism.” Even though it is typically noncommercial in character, free innovation often involves regulatory entrepreneurialism and technological civil disobedience.

Innovation arbitrage: The movement of ideas, innovations, or operations to jurisdictions that provide legal and regulatory environments most hospitable to entrepreneurial activity. It can also be thought of as a form of jurisdictional shopping and can be facilitated by competitive federalism.

Innovation culture: The various social and political attitudes and pronouncements toward innovation, technology, and entrepreneurial activities that, taken together, influence the innovative capacity of a culture or nation.

Pacing problem: A term that generally refers to the inability of legal or regulatory regimes to keep up with the intensifying pace of technological change.

Permissionless innovation: The general notion that “it’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.” As a policy vision, it refers to the idea that experimentation with new technologies and innovations should generally be permitted by default.

Precautionary principle: The practice of crafting public policies to control or limit innovations until their creators can prove that they will not cause any harm or disruptions.

Regulatory entrepreneurs: Evasive entrepreneurs who set out to intentionally challenge and change the law through their innovative activities. In essence, policy change is part of their business model.

Soft law: Informal, collaborative, and constantly evolving governance mechanisms that differ from hard law in that they lack the same degree of enforceability.

Technological civil disobedience: The technologically enabled refusal of individuals, groups, or businesses to obey certain laws or regulations because they find them offensive, confusing, time-consuming, expensive, or perhaps just annoying and irrelevant.

Technologies of freedom: Devices and platforms that let citizens openly defy (or perhaps just ignore) public policies that limit their liberty or freedom to innovate. Another term with the same meaning is “technologies of resistance.”

“Evasive Entrepreneurs” – 10 Highlights from the Book

I’m pleased to announce that the Cato Institute has just published my latest book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments. Here’s my introductory launch essay about the book as well as the online launch event. And here’s a list of 13 key terms used throughout the book.

I’m pleased to announce that the Cato Institute has just published my latest book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance How Innovation Improves Economies and Governments. Here’s my introductory launch essay about the book as well as the online launch event. And here’s a list of 13 key terms used throughout the book.

In coming days and weeks I will be occasionally blogging about different arguments made in the 368-page book, but here’s a quick summary of some of the key points I make in the book. These ten passages are pulled directly from the text:

“the freedom to innovate is essential to human betterment for each of us individually and for civilization as a whole. That freedom deserves to be taken more seriously today.”

“Entrepreneurialism and technological innovation are the fundamental drivers of economic growth and of the incredible advances in the everyday quality of life we have enjoyed over time. They are the key to expanding economic opportunities, choice, and mobility.”

“Unfortunately, many barriers exist to expanding innovation opportunities and our entrepreneurial efforts to help ourselves, our loved ones, and others. Those barriers include occupational licensing rules, cronyism-based industrial protectionist schemes, inefficient tax schemes, and many other layers of regulatory red tape at the federal, state, and local levels. We should not be surprised, therefore, when citizens take advantage of new technological capabilities to evade some of those barriers in pursuit of their right to earn a living, to tinker with or try doing new things, or just to learn about the world and serve it better.”

“Evasive entrepreneurs rely on a strategy of permissionless innovation in both the business world and the political arena. They push back against ‘the Permission Society,’ or the convoluted labyrinth of permits and red tape that often encumber entrepreneurial activities.”

“We should be willing to tolerate a certain amount of such outside-the-box thinking because entrepreneurialism expands opportunities for human betterment by constantly replenishing the well of important, life-enhancing ideas and applications.”

“we should better appreciate how creative acts and the innovations they give rise to can help us improve government by keeping public policies fresh, sensible, and in line with common sense and the consent of the governed.”

“Evasive entrepreneurialism is not so much about evading law altogether as it is about trying to get interesting things done, demonstrating a social or an economic need for new innovations in the process, and then creating positive leverage for better results when politics inevitably becomes part of the story. By acting as entrepreneurs in the political arena, innovators expand opportunities for themselves and for the public more generally, which would not have been likely if they had done things by the book.”

“Dissenting through innovation can help make public officials more responsive to the people by reining in the excesses of the administrative state, making government more transparent and accountable, and ensuring that our civil rights and economic liberties are respected.”

“In an age when many of the constitutional limitations on government power are being ignored or unenforced, innovation itself can act as a powerful check on the power of the state and can help serve as a protector of important human liberties.”

“Lawmakers and regulators need to consider a balanced response to evasive entrepreneurialism that is rooted in the realization that technology creators and users are less likely to seek to evade laws and regulations when public policies are more in line with common sense.”

In a nutshell, the core arguments made in the book boil down to this: “evasive entrepreneurialism can transform our society for the better because it can do the following

Help expand the range of life-enriching innovations available to society.

Help citizens pursue lives of their own choosing—both as creators looking for the freedom to earn a living and as consumers looking to discover and enjoy important new goods and services.

Help provide a meaningful, ongoing check on government policies and programs that all too often have outlived their usefulness or simply defy common sense.”

I hope you will consider reading the book.

April 21, 2020

Barriers to a Builder’s Movement: Thoughts on Andreessen’s Manifesto

[First published by AIER on April 20, 2020 as “Innovation and the Trouble with the Precautionary Principle.”]

In a much-circulated new essay (“It’s Time to Build”), Marc Andreessen has penned a powerful paean to the importance of building. He says the COVID crisis has awakened us to the reality that America is no longer the bastion of entrepreneurial creativity it once was. “Part of the problem is clearlyforesight, a failure of imagination,” he argues. “But the other part of the problem is what we didn’t do in advance, and what we’re failing to do now. And that is a failure of action, and specifically our widespread inability to build.”

Andreessen suggests that, somewhere along the line, something changed in the DNA of the American people and they essentially stopped having the desire to build as they once did. “You don’t just see this smug complacency, this satisfaction with the status quo and the unwillingness to build, in the pandemic, or in healthcare generally,” he says. “You see it throughout Western life, and specifically throughout American life.” He continues:

“The problem is desire. We need to want these things. The problem is inertia. We need to want these things more than we want to prevent these things. The problem is regulatory capture. We need to want new companies to build these things, even if incumbents don’t like it, even if only to force the incumbents to build these things.”

Accordingly, Andreessen continues on to make the case to both the political right and left to change their thinking about building more generally. “It’s time for full-throated, unapologetic, uncompromised political support from the right for aggressive investment in new products, in new industries, in new factories, in new science, in big leaps forward.”

What’s missing in Andreessen’s manifesto is a concrete connection between America’s apparent dwindling desire to build these things and the political realities on the ground that contribute to that problem. Put simply, policy influences attitudes. More specifically, policies that frown upon entrepreneurial risk-taking actively disincentivize the building of new and better things. Thus, to correct the problem Andreessen identifies, it is essential that we must first remove political barriers to productive entrepreneurialism or else we will never get back to being the builders we once were.

Attitudes about Progress Matter

The economic historian Joel Mokyr has noted how, “technological progress requires above all tolerance toward the unfamiliar and the eccentric” and that the innovation that undergirds economic growth is best viewed as “a fragile and vulnerable plant” that “is highly sensitive to the social and economic environment and can easily be arrested by relatively small external changes.” Specifically, societal and political attitudes toward growth, risk-taking, and entrepreneurial activities (and failures) are important to the competitive standing of nations and the possibility of long-term prosperity. “How the citizens of any country think about economic growth, and what actions they take in consequence, are,” Benjamin Friedman observes, “a matter of far broader importance than we conventionally assume.”

Former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and co-author Adrian Wooldridge have observed that “[t]he key to America’s success lies in its unique toleration for ‘creative destruction,’” and an “enduring preference for change over stability.” This is consistent with the findings of Deirdre McCloskey’s recent 3-volume trilogy about the history of modern economic growth. McCloskey meticulously documents how an embrace of “bourgeois virtues” (i.e., positive attitudes about markets and innovation) was the crucial factor propelling the invention and economic growth that resulted in the Industrial Revolution.The importance of positive attitudes toward innovation and risk-taking were equally important for the Information Revolution more recently. In turn, that also helps explain why so many US-based tech innovators became global powerhouses, while firms from other countries tend to flounder because their innovation culture was more precautionary in orientation.

There are limits to how much policymakers can do to influence the attitudes among citizens toward innovation, entrepreneurialism, and economic growth. When policymakers set the right tone with a positive attitude toward innovation, however, it inevitably infuses various institutions and creates powerful incentives for entrepreneurial efforts to be undertaken. This, in turn, influences broader societal attitudes and institutions toward innovation and creates a positive feedback loop. “If we learn anything from the history of economic development,” argued David Landes in his magisterial The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some Are So Poor, “it is that culture makes all the difference.” Research by other scholars finds that, “existing cultural conditions determine whether, when, how and in what form a new innovation will be adopted.”

Economists like Mancur Olson speak of the importance of a “structure of incentives” that helps explain why “the great differences in the wealth of nations are mainly due to differences in the quality of their institutions and economic policies.”In this sense, “institutions” include what Elhanan Helpman defines as “systems of rules, beliefs, and organizations,”including the rule of law and court systems,property rights,contracts, free trade policies and institutions, light-touch regulations and regulatory regimes, freedom to travel, and various other incentives to invest.

It is the freedom to invest, the freedom to work, and the freedom to build that particularly concerns Marc Andreessen. But he needs to draw the connection with the specific public policies that hold back our ability to exercise those freedoms.

Policy Defaults toward Innovation Matter Even More

Unfortunately, a great many barriers exist to entrepreneurial efforts. Those barriers to building include inflexible health and safety regulation, occupational licensing rules, cronyist industrial protectionist schemes, inefficient (industry-rigged) tax schemes, rigid zoning ordinances, and many other layers of regulatory red tape at the federal, state, and local level.

What unifies all these policies is risk aversion and the precautionary principle. As I argued in my last book, we have a choice when it comes to setting defaults for innovation policy. We can choose to set innovation defaults closer to the green light of “permissionless innovation,” generally allowing entrepreneurial acts unless a compelling case can be made not to. Alternatively, we can set our default closer to the red light of the precautionary principle, which disallows risk-taking or entrepreneurialism until some authority gives us permission to proceed.

My book made the case for permissionless innovation as the superior default regime. My argument for rejecting the precautionary principle as the default came down to belief that, “living in constant fear of worst-case scenarios—and premising public policy on them—means that best-case scenarios will never come about. When public policy is shaped by precautionary principle reasoning,” I argued, “it poses a serious threat to technological progress, economic entrepreneurialism, social adaptation, and long-run prosperity.”

Heavy-handed preemptive restraints on innovative acts have such deleterious effects because they raise barriers to entry, increase compliance costs, and create more risk and uncertainty for entrepreneurs and investors. Progress is impossible without constant trial-and-error experimentation and entrepreneurial risk-taking. Thus, it is the unseen costs of forgone innovation opportunities that make the precautionary principle so troubling as a policy default. Without risk, there can be no reward. Scientist Martin Rees refers to this truism about the precautionary principle as “the hidden cost of saying no.”

More generally, risk analysts have noted that the precautionary principle “lacks a firm logical foundation” and is “literally incoherent” because it fails to specify a clear standard by which to judge which risks are most serious and worthy of preemptive control. Moreover, regulatory policy experts have criticized the fact that the precautionary principle, “may be misused for protectionist ends; it tends to undermine international regulatory cooperation; and it may have highly undesirable distributive consequences.” Specifically, large incumbent firms are almost always more likely able to deal with rigid, expensive regulatory regimes or, worse yet, can game those systems by “capturing” policymakers and using regulatory regimes to exclude new rivals.

Precaution Suffocates Productive Entrepreneurialism

The problem today is that a massive volume of precautionary policies exist that discourage “productive entrepreneurship” (i.e., building) and instead actively encourage “unproductive entrepreneurship” (i.e., preservation of the status quo). Andreessen identifies this problem when he speaks of “smug complacency, this satisfaction with the status quo and the unwillingness to build.” But he doesn’t fully connect the dots between how the attitudes came about and the public policy incentives that actively encourage such thinking.

Why try to build when all the incentives are aligned against you? Andreessen wants to know “Where are the supersonic aircraft? Where are the millions of delivery drones? Where are the high speed trains, the soaring monorails, the hyperloops, and yes, the flying cars?” Well, I’ll tell you where they are at. They are trapped in the minds of inventive people who cannot bring them to fruition so long as an endless string of barriers makes it costly or impossible for them to realize those dreams.

Read Eli Dourado’s important essay on “How Do We Move the Needle on Progress?” to get a more concrete feel for the specific barriers to building in the fields where productive entrepreneurialism is most needed: health, housing, energy, and transportation.

The bottom line, as Dustin Chambers and Jonathan Munemo noted in a 2017 Mercatus Center report on the impact of regulation on entrepreneurial activity, is that “If a nation wishes to promote higher levels of domestic entrepreneurship in both the short and long run, top priority should be given to reducing barriers to entry for new firms and to improving overall institutional quality (especially political stability, regulatory quality, and voice and accountability).”

This doesn’t mean there is no role for government in helping to promote “building” and entrepreneurialism. A healthy debate continues to rage about “state capacity” as it pertains to government investments in research and development, for example. While I am skeptical, there may very well be some steps governments can take to encourage more and better investments in the sectors and technologies we desperately need. But all the “state capacity” in the world isn’t going to help until we first clear away the barriers that hold back the productive spirit of the people.

Oiling the Wheels of Novelty

My new book, which is due out next week, discusses how innovation improves economies and government institutions. It builds on the fundamental insight of Calestous Juma, who concluded his masterwork Innovation and Its Enemies by reminding us of the continued importance of “oiling the wheels of novelty,” to constantly replenish the well of important ideas and innovations. “The biggest risk that society faces by adopting approaches that suppress innovation,” Juma said, “is that they amplify the activities of those who want to preserve the status quo by silencing those arguing for a more open future.”

The openness Juma had in mind represents a tolerance of new ideas, inventions, and unknown futures. It can and should also represent an openness to new, more flexible methods of governance. For, if it doesn’t, the builder movement that Andreessen and others long for will remain just a distant dream, incapable of ever being realized so long as the wheels of novelty are gummed up by decades of inefficient, archaic, counterproductive public policies.

The use of technology in COVID-19 public health surveillance

The recently-passed CARES Act included $500 million for the CDC to develop a new “surveillance and data-collection system” to monitor the spread of COVID-19.

There’s a fierce debate about how to use technology for health surveillance for the COVID-19 crisis. Unfortunately this debate is happening in realtime as governments and tech companies try to reduce infection and death while complying with national laws and norms related to privacy.

Technology has helped during the crisis and saved lives. Social media, chat apps, and online forums allow doctors, public health officials, manufacturers, entrepreneurs, and regulators around the world to compare notes and share best practices. Broadband networks, Zoom, streaming media, and gaming make stay-at-home order much more pleasant and keeps millions of Americans at work, remotely. Telehealth apps allow doctors to safely view patients with symptoms. Finally, grocery and parcel delivery from Amazon, Grubhub, and other app companies keep pantries full and serve as a lifeline to many restaurants.

The great tech successes here, however, will be harder to replicate for contact tracing and public health surveillance. Even the countries that had the tech infrastructure somewhat in place for contact tracing and public health surveillance are finding it hard to scale. Privacy issues are also significant obstacles. (On the Truth on the Market blog, FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson provides a great survey of how other countries are using technology for public health and analysis of privacy considerations. Bronwyn Howell also has a good post on the topic.) Let’s examine some of the strengths and weaknesses of the technologies.

Cell tower location information

Personal smartphones typically connect to the nearest cell tower, so a cell networks record (roughly) where a smartphone is at a particular time. Mobile carriers are sharing aggregated cell tower data with public health officials in Austria, Germany, and Italy for mobility information.

This data is better than nothing for estimating district- or region-wide stay-at-home compliance but the geolocation is imprecise (to the half-mile or so).

Cell tower data could be used to enforce a virtual geofence on quarantined people. This data is, for instance, used in Taiwan to enforce quarantines. If you leave a geofenced area, public health officials receive an automated notification of your leaving home.

Assessment: Ubiquitous, scalable. But: rarely useful and virtually useless for contact tracing.

GPS-based apps and bracelets

Many smartphone apps passively transmit precise GPS location to app companies at all hours of the day. Google and Apple have anonymized and aggregated this kind of information in order to assess stay-at-home order effects on mobility. Facebook reportedly is also sharing similar location data with public health officials.

As Trace Mitchell and I pointed out in Mercatus and National Review publications, this information is imperfect but could be combined with infection data to categorize neighborhoods or counties as high-risk or low-risk.

GPS data, before it’s aggregated by the app companies for public view, reveals precisely where people are (within meters). Individual data is a goldmine for governments, but public health officials will have a hard time convincing Americans, tech companies, and judges they can be trusted with the data.

It’s an easier lift in other countries where trust in government is higher and central governments are more powerful. Precise geolocation could be used to enforce quarantines.

Hong Kong, for instance, has used GPS wristbands to enforce some quarantines. Tens of thousands of Polish residents in quarantines must download a geolocation-based app and check in, which allows authorities to enforce quarantine restrictions. It appears the most people support the initiative.

Finally, in Iceland, one third of citizens have voluntarily downloaded a geolocation app to assist public officials in contact tracing. Public health officials call or message people when geolocation records indicate previous proximity with an infected person. WSJ journalists reported on April 9 that:

If there is no response, they send a police squad car to the person’s house. The potentially infected person must remain in quarantine for 14 days and risk a fine of up to 250,000 Icelandic kronur ($1,750) if they break it.

That said, there are probably scattered examples of US officials using GPS for quarantines. Local officials in Louisville, Kentucky, for example, are requiring some COVID-19-positive or exposed people to wear GPS ankle monitors to enforce quarantine.

Assessment: Aggregated geolocation information is possibly useful for assessing regional stay-at-home norms. Individual geolocation information is not precise enough for effective contact tracing. It’s probably precise and effective for quarantine enforcement. But: individual geolocation is invasive and, if not volunteered by app companies or users, raises significant constitutional issues in the US.

Bluetooth apps

Many researchers and nations are working on or have released some type of Bluetooth app for contact tracing. This includes Singapore, the Czech Republic, Britain, Germany, Italy and New Zealand.

For people who use these apps, Bluetooth runs in the background, recording other Bluetooth users nearby. Since Bluetooth is a low-power wireless technology, it really only can “see” other users within a few meters. If you use the app for awhile and later test positive for infection, you can register your diagnosis. The app will then notify (anonymously) everyone else using the app, and public health officials in some countries, who you came in contact with in the past several days. My colleague Andrea O’Sullivan wrote a great piece in Reason about contact tracing using Bluetooth.

These apps have benefits over other forms of public health tech surveillance: they are more precise than geolocation information and they are voluntary.

The problem is that, unlike geolocation apps, which have nearly 100% penetration with smartphone users, Bluetooth contact tracing apps have about 0% penetration in the US today. Further, these app creators, even governments, don’t seem to have the PR machine to gain meaningful public adoption. In Singapore, for instance, adoption is reportedly only 12% of the population, which is way too low to be very helpful.

A handful of institutions in the world could get appreciable use of Bluetooth contact tracing: telecom and tech companies have big ad budgets and they own the digital real estate on our smartphones.

Which is why the news that Google and Apple are working on a contact tracing app is noteworthy. They have the budget and ability to make their hundreds of millions of Android and iOS users aware of the contact tracing app. They could even go so far as push a notification to the home screen to all users encouraging them to use it.

However, I suspect they won’t push it hard. It would raise alarm bells with many users. Further, as Dan Grover stated a few weeks ago about why US tech companies haven’t been as active as Chinese tech companies in using apps to improve public education and norms related to COVID-19:

Since the post-2016 “techlash”, tech companies in Silicon Valley have acted with a sometimes suffocating sense of caution and unease about their power in the world. They are extremely careful to not do anything that would set off either party or anyone with ideas about regulation. And they seldom use their pixel real estate towards affecting political change.

[Ed.: their puzzling advocacy of Title II “net neutrality” regulation a big exception].

Techlash aside, presumably US companies also aren’t receiving the government pressure Chinese companies are receiving to push public health surveillance apps and information. [Ed.: Bloomberg reports that France and EU officials want the Google-Apple app to relay contact tracing notices to public health officials, not merely to affected users. HT Eli Dourado]

Like most people, I have mixed feelings about how coercive the state and how pushy tech companies should be during this pandemic. A big problem is that we still have only an inkling about how deadly COVID-19 is, how quickly it spreads, and how damaging stay-at-home rules and norms are for the economy. Further, contact-tracing apps still need extensive, laborious home visits and follow-up from public health officials to be effective–something the US has shown little ability to do.

There are other social costs to widespread tech-enabled tracing. Tyler Cowen points out in Bloomberg that contact tracing tech is likely inevitable, but that would leave behind those without smartphones. That’s true, and a major problem for the over-70 crowd, who lack smartphones as a group and are most vulnerable to COVID-19.

Because I predict that Apple and Google won’t push the app hard and I doubt there will be mandates from federal or state officials, I think there’s only a small chance (less than 15%) a contact tracing wireless technology will gain ubiquitous adoption this year (60% penetration, more than 200 million US smartphone users).

Assessment: A Bluetooth app could protect privacy while, if volunteered, giving public health officials useful information for contact tracing. However, absent aggressive pushes from governments or tech companies, it’s unlikely there will be enough users to significantly help.

Health Passport

The chances of mass Bluetooth app use would increase if the underlying tech or API is used to create a “health passport” or “immunity passport”–a near-realtime medical certification that someone will not infect others. Politico reported on April 10 that Dr. Anthony Fauci, the White House point man on the pandemic, said the immunity passport idea “has merit.”

It’s not clear what limits Apple and Google will put on their API but most APIs can be customized by other businesses and users. The Bluetooth app and API could feed into a health passport app, showing at a glance whether you are infected or you’d been near someone infected recently.

For the venues like churches and gyms and operators like airlines and cruise ships that need high trust from participants and customers, on the spot testing via blood test or temperature taking or Bluetooth app will likely gain traction.

There are the beginnings of a health passport in China with QR codes and individual risk classifications from public health officials. Particularly for airlines, which is a favored industry in most nations, there could be public pressure and widespread adoption of a digital health passport. Emirates Airlines and the Dubai Health Authority, for instance, last week required all passengers on a flight to Tunisia to take a COVID-19 blood test before boarding. Results came in 10 minutes.

Assessment: A health passport integrates several types of data into a single interface. The complexity makes widespread use unlikely but it could gain voluntary adoption by certain industries and populations (business travelers, tourists, nursing home residents).

Conclusion

In short, tech could help with quarantine enforcement and contact tracing, but there are thorny questions of privacy norms and it’s not clear US health officials have the ability to do the home visits and phone calls to detect spread and enforce quarantines. All of these technologies have issues (privacy or penetration or testing) and there are many unknowns about transmission and risk. The question is how far tech companies, federal and state law officials, the American public, and judges are prepared to go.

Hand Sanitizers, Face Masks and Common Sense Regulation

[Co-authored with Trace Mitchell and first published on The Bridge on April 21, 2020.]

Which seems like a more pressing concern at the moment: Ensuring that we get hand sanitizer onto shelves or making sure that children don’t drink it once we do? Getting face masks out to the public quickly, or waiting until they can be manufactured to precise federal regulatory specifications?

These questions are currently being raised by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The agency’s rules have been making it hard for distilleries to address the hand sanitizer shortage. Companies looking to supply more face masks to the nation as quickly as possible have been similarly stymied.

Sometimes government regulation is so out of touch with reality and common sense that it should force us to rethink the way business is done in Washington. As our Mercatus Center colleague Scott Sumner concludes, the past month has witnessed “a torrent of governmental incompetence that is breathtaking in scale” and “regulations so bizarre that if put in a novel no one would believe them.” Sadly, he’s right, and the strange world of FDA hand sanitizer and face mask regulation provides us with two teachable moments.

As we write, the FDA has repealed or at least examined many of the immediate barriers to the production of face masks and hand sanitizers. Still, precious time was lost waiting for the agency to clear out unneeded regulations. Going forward, regulators should be sure to review and prune their cache of rules before calamity strikes, perhaps in the form of an independent regulatory review commission or a regulatory budget.

Distilling the meaning of regulation: no innovation without permission

Hard sanitizers have been hard to find for weeks now. Who better to respond to the need for alcohol-based hand sanitizers than the nation’s many distilleries? After all, they have the equipment and means to easily churn out oceans of the stuff. Hearing news of the shortages, hundreds of entrepreneurial distillers rose to the challenge and began cranking out homemade sanitizers, only to learn that their noble efforts were of questionable legality.

That’s because distilleries must navigate a confusing maze of federal, state, and local taxes and regulations. Nominally, these rules are supposed to protect public health. In practice, however, governments often use these rules to extract as much tax revenue as possible.

Setting aside the questions of whether distilleries and their customers should bear these hefty taxes during regular times, these tax rules limited distillers’ efforts to respond to the sanitizer shortage.

The problem is in how these tax rules interact with other rules about how hand sanitizer can be made. The FDA’s rules required that hand sanitizers be made with a bitter-tasting denaturing agent to prevent people from drinking it. But denatured alcohol has become scarce during the pandemic. Yet if distilleries did not use denatured alcohol in their homebrew hand sanitizer, their concoctions would be taxed as an alcoholic beverage!

In theory, taxing undenatured alcohol at a much higher rate also helps the government diminish alcohol use, or keep it out of the hands of minors. That logic is questionable, but it should not even be an issue when we are talking about how to make hand sanitizer. Again, what is the fear here? Are children really going to consume hand sanitizer with drinkable alcohol in it? Seems like there are probably many easier ways to skirt drinking laws than chugging small vials of hand sanitizer.

Moreover, there is an easy fix to all this. The FDA recently issued two guidance documents that temporarily cease actions against pharmacists and firms that produce hand sanitizers with certain non-traditional compositions, so long as they do not intentionally make the mixture more pleasant tasting.

That’s a good start. But the FDA has not updated its guidance to permit distillers to use undenatured alcohol, which is what most of them have on hand. Undenatured alcohol-based hand sanitizers are just as effective as those that are natured alcohol-based. The FDA should explicitly allow this kind of hand sanitizer to be produced so that more people have access to this needed supply.

Face masks: covered in red tape

And it’s not just hand sanitizer.

Face masks have become essential during this pandemic. Doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals are in desperate need of these important, potentially life-saving, items to limit their risk of infection. In addition, the CDC announced last week that everyone should begin wearing cloth face coverings “fashioned from household items or made at home from common materials” when going out in public or interacting with others to help lower the risk of transmission and slow the spread of the coronavirus.

However, the CDC does not recommend that people use surgical masks or N95 respirators, as these are “critical supplies” that need to be reserved for “healthcare workers and other medical first responders.” So why would the CDC want people to create their own homemade cloth masks? Because there is a massive shortage of the higher quality variety used by medical personnel.

Department of Health and Human Services officials have estimated that the United States will need roughly 3.5 billion medical-grade masks to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. How many did the United States actually have on hand at the beginning of this crisis? About 35 million. That is just one percent of the overall need. This has led some hospitals to begin reusing disposable masks or creating their own out of everyday office supplies. With such a significant mismatch between the overall demand and the current supply, it is completely understandable that the CDC would want people to make their own masks and refrain from tapping into the limited supply of medical-grade masks.

But the question remains, why is there such a massive shortage to begin with? Why haven’t businesses and entrepreneurs noticed the incredible demand for face masks and flooded the market with new devices? Why haven’t healthcare facilities started importing face masks from trading partners like China to meet their current needs? The answer is fairly simple. Up until recently, they weren’t allowed.

The FDA considers face masks to be medical devices and subjects them to cumbersome red tape and hyper-formalistic procedures. If a business wants to begin producing face masks and distributing them to the public, it must first go through the FDA’s approval process. This process often takes months and requires numerous tests, extensive records, and a detailed application subject to approval.

In addition, until recently, the FDA made it illegal to import certain devices—like China’s KN95 face mask—irrespective of how well they may work. While these burdensome restrictions are often justified based on a desire to promote public safety, it is clear they do the exact opposite during a pandemic. Instead of protecting the public, these controls actively prevent people from getting the life-saving items they need. In fact, the mismatch created by these regulations is so large that a gray market has emerged for imported face masks.

Luckily, policymakers are beginning to recognize the harm these policies cause. On March 26, the FDA announced that it will not enforce these cumbersome manufacturing requirements for the duration of this crisis. Earlier this month, the agency decided to allow the importation of China’s KN95 face masks.

While these decisions are steps in the right direction, quite a bit of harm has resulted from the delay caused by these overly restrictive regulations. It shouldn’t take a crisis of this magnitude for decision-makers to question policies that raise barriers to supplying people with the resources they need.

The death of common sense

What is going on here? As our colleague Martin Gurri notes, agencies like the FDA and the CDC seem to be “mesmerized by proceduralism” and “tied up in bureaucratic knots.” This is by design, however. These agencies tend to be highly risk-averse and rely on strict, centralized, top-down modes of organization and decision-making. Precaution and preservation of the status quo triumph over experimentation and chance. Their rules are heavy-handed, inflexible, and slow to adapt to new circumstances. Rules quickly become ossified, and agencies eventually fall into a “build-and-freeze” model of regulation that sets rules in stone. These rules may address relevant issues at the time but the agencies either fail to eliminate them when they become obsolete or to bring them in line with new social, economic, and technical realities.

What is left is a series of one-size-fits-all mandates, prohibitions, and penalties that are ill-equipped to deal with a crisis and that can actually undermine the very goals they were put in place to achieve. Practical efforts to protect public health get rejected because proceduralism is valued more highly. “Going by the book” becomes a greater virtue than being innovative.

That is how we get to the point that something as simple as hand sanitizers and face masks can become trapped in a surreal regulatory maze that can only be escaped by petitioning bureaucrats for the freedom to innovate.

Cleaning up this mess

How do we clean up this mess? First, we begin by acknowledging that we face a serious problem. The COVID-19 crisis has revealed just how dysfunctional America’s “permission society” has become, which has profound consequences for public welfare. “Society can’t function when stuck in a heap of accumulated mandates of past generations,” notes Philip K. Howard, author of The Death of Common Sense: How Law Is Suffocating America.

While many government rules are put on the books with the best of intentions, regulatory flexibility and humility should guide enforcement efforts. Rote compliance shouldn’t trump common sense. At some point, periodic house-cleaning becomes essential.

Alas, policymakers seem incapable of regularly pruning regulations, and this year’s spring cleaning for the regulatory state only came about because the COVID-19 crisis forced their hand. Governments at the federal, state, and local levels are now temporarily suspending many regulations that have clearly limited innovative responses to the crisis. A better approach is to get ahead of the problem and begin rolling back outdated, overly cumbersome regulations before a situation like this one arises.

One way of doing this would be to establish a BRAC-style commission to periodically review the regulatory code and clear outdated, unnecessary, or overly burdensome restrictions. Independent regulatory reform committees allow legislatures and agencies to focus on their current needs while still ensuring that some entity is assessing the efficacy of previously enacted laws and regulations. In addition, because this would be an independent commission outside of any particular agency or governmental body, it may be more objective in gauging whether past restrictions really are serving a significant interest and more willing to strike down those that are not. The practice of regulatory budgeting could similarly help to beat back our out-of-control regulatory state.

Whatever the path chosen, it is imperative that governments get their regulatory houses in order. COVID-19 has shown some of the social fault lines that rigid regulation has created in healthcare and technology. We should not wait for the next crisis to show us where vulnerabilities lie in other domains.

April 16, 2020

Needed: A ‘Fresh Start Initiative’ to Address Rules Suspended during the Crisis

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University has just released a new paper by Patrick A. McLaughlin, Matthew D. Mitchell, and me entitled, “A Fresh Start: How to Address Regulations Suspended during the Coronavirus Crisis.” Here’s a quick summary.

As the COVID-19 crisis intensified, policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels started suspending or rescinding laws and regulations that hindered sensible, speedy responses to the pandemic. These “rule departures” raised many questions. Were the paused rules undermining public health and welfare even before the crisis? Even if the rules were well intentioned or once possibly served a compelling interest, had they grown unnecessary or counterproductive? If so, why did they persist? How will the suspended rules be dealt with after the crisis? Are there other rules on the books that might transform from merely unnecessary to actively harmful in future crises?

Once the COVID-19 crisis subsides, there is likely to be considerable momentum to review the rules that have slowed down the response. If policymakers felt the need to abandon these rules during the current crisis, those same rules should probably be permanently repealed or at least comprehensively reformed to allow for more flexible responses in the future.

Accordingly, when the pandemic subsides, policymakers at the federal and state levels should create “Fresh Start Initiatives” that would comprehensively review all suspended rules and then outline sunsetting or reform options for them. To this end, we propose an approach based on the successful experience of the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission.

Read the entire paper here to see how it would work. This is our chance to finally do some much-needed spring cleaning for the regulatory state.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower