Adam Thierer's Blog, page 17

September 26, 2019

Occupational Licensing Reform is Not a Partisan Issue

by Adam Thierer and Trace Mitchell

This essay originally appeared on The Washington Examiner on September 12, 2019.

You won’t find President Trump agreeing with Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama on many issues, but the need for occupational licensing reform is one major exception. They, along with many other politicians and academics both Left and Right, have identified how state and local “licenses to work” restrict workers’ opportunities and mobility while driving up prices for consumers.

Of course, not everybody has to agree with high-profile Democrats and Republicans, but let’s at least welcome the chance to discuss something important without defaulting to our partisan bunkers.

This past week, for example, ThinkProgress published an article titled “Koch Brothers’ anti-government group promotes allowing unlicensed, untrained cosmetologists.” Centered around an Americans for Prosperity video highlighting the ways in which occupational licensing reform could lower some of the barriers that prevent people from bettering their lives, the article painted a picture of an ideologically driven, right-wing movement.

In reality, it’s anything but that.

Occupational licensing has expanded significantly in the past several decades. It began as a relatively uncommon regulatory approach aimed at ensuring public safety and reserved for only those occupations that pose the greatest risk of harm or abuse. Now, it’s a fairly standard means of regulating all kinds of industries.

In the 1950s, around 5% of workers needed a license to perform their jobs. Today, it’s over 30%. This drastic change has raised concerns from people at virtually every point along the political spectrum.

In fact, one of the most crucial reports on occupational licensing was created by the Obama administration. It found that while occupational licensing can lead to higher quality services for consumers, “by making it harder to enter a profession, licensing can also reduce employment opportunities and lower wages for excluded workers, and increase costs for consumers.”

Last year, the independent Federal Trade Commission followed suit, releasing a report highlighting the negative effects of occupational licensing and proposing ways to combat them by making worker licenses more portable across state lines.

Hillary Clinton has also expressed support for targeted occupational licensing reform. In 2016, she released a set of policy proposals aimed at helping small businesses which included a goal to “streamline unnecessary licensing to make it less costly to start a small business.”

Fellow Democrat Joe Biden has talked about overly burdensome occupational licensing. In his words, “They’re making it harder and harder in a whole range of professions, all to keep competition down.”

In addition, groups across the ideological spectrum, including the Brookings Institution and the American Civil Liberties Union, have expressed concern over the costs of burdensome work requirements.

President Trump, a critic of the Koch brothers, has also shown support for occupational licensing reform. He recently praised Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey for his state’s new approach, saying, “We hope that other states are going to follow Arizona’s lead.”

Why are all of these people and organizations, with fairly distinct perspectives and goals, concerned about the same issue? Because occupational licensing is really costly, and those costs often fall upon the most vulnerable and disadvantaged Americans.

The report issued by the Obama administration found that occupational licensing serves as a hidden tax on consumer goods and services, increasing prices by anywhere between 3 and 16%. The report went on to assert that these costs fall disproportionately on certain segments of the population: immigrants, military spouses, and reformed convicts. Other research supports these findings.

Economist Morris Kleiner found that “restrictions from occupational licensing can result in up to 2.85 million fewer jobs nationwide, with an annual cost to consumers of $203 billion.” Once again, these costs are not evenly distributed: Our colleague Matt Mitchell looked at the effect of occupational licensing on the poor and disadvantaged, finding that it can “disparately affect ethnic minorities and other specific populations.” Forcing barbers to obtain a license “reduces the probability of a black individual working as a barber by 17.3%.”

Propelled by the weight of the evidence, policymakers are starting to work together. It isn’t ideological; it’s just good policy. Isn’t that what we want?

September 23, 2019

How Do You Value Data? A Reply To Jaron Lanier’s Op-Ed In The NYT

Jaron Lanier was featured in a recent New York Times op-ed explaining why people should get paid for their data. Under this scheme, he estimates the total value of data for a four person household could fetch around $20,000.

Let’s do the math on that.

Data from eMarketer finds that users spend about an hour and fifteen minutes per day on social media for a total of 456.25 hours per year. Thus, by Lanier’s estimates, the income from data would be about $10.95 per hour. That’s not too bad!

By any measure, however, the estimate is high. Since I have written extensively on this subject (see this, this, and this), I thought it might be helpful to explain the four general methods used to value an intangibles like data. They include income methods, market rates, cost methods, and finally, shadow prices.

Most data valuations are accomplished through income derivations, often by simply dividing the total market capitalization or revenue of a firm by the total number of users. For those in finance, this method seems most logical since it is akin to an estimate of future cash flows. In its 2018 annual report, Facebook calculated that the average revenue per user was around $112 in the United States and Canada. Antonio Garcia-Martinez recently used this data point in Wired magazine to place an upper limit to the digital dividend idea from California Governor Gavin Newsom. Similarly, when Microsoft bought LinkedIn, reports suggested that they were buying monthly active users at a rate of $260. A. Douglas Melamed argued in a recent Senate hearing that the upper-bound value on data should at least be cognizant of the acquisition cost for advertisements—putting the total user value at around $16.

Income-based valuations, however, are crude estimates because they are not capturing a user’s ability to marginally earn revenue for the platform. The way to understand this problem is by first recognizing how the three classes of data interact online. Volunteered data is data that is both innate to an individual’s profile, such as age and gender, and information they share, such as pictures, videos, news articles, and commentary. Observed data comes as a result of user interactions with the volunteered data; it is this class of data that platforms tend to collect in data centers. Last, inferred data is the information that comes from analysis of the first two classes, which explains how groups of individuals are interacting with different sets of digital objects.

Inferential data is the key, as it both drives advertising decisions, and it helps determine what content is presented to users. Thus, the value of a user’s data would combine

The value of that user’s data to increase all their friend’s demand for content; and

The value of that user’s data to contribute to increases in advertising demand.

I’ve seen work suggesting that Shapley values might be used to figure out these numbers. Needless to say, income based valuations are difficult.

Market prices are another method of valuing data, and they tend to place the lowest premium on data. For example:

Vice recently reported that DMVs across the US have been selling records for as little as $0.01 each.

Wired editor Gregory Barber sold his location data, Apple Health data, and Facebook data, and all he got was a paltry 0.3 cents.

After a breach at Facebook, Facebook logins were selling on the dark web for $2.60.

Advertisers typically pay a few cents for profiles.

In contrast, Dutch student Shawn Buckles auctioned all his personal data and earned a grand total of €350, which is around $385 in 2014.

As with any market, it is important to pay attention to the clearing price because not all markets clear. The bankruptcy proceedings for Caesars Entertainment, a subsidiary of the larger casino company, offers a unique example of this problem. As the assets were being priced in the selloff, the Total Rewards customer loyalty program got valued at nearly $1 billion, making it “the most valuable asset in the bitter bankruptcy feud at Caesars Entertainment Corp.” But the ombudsman’s report understood that it would be a tough sell because of the difficulties in incorporating it into another company’s loyalty program. Although it was Caesar’s’ most pricey asset, its value to an outside party was an open question.

As I detailed earlier this year, data is often valued within a relationship, but practically valueless outside of it. There is a term of art for this phenomenon, as economist Benjamin Klein explained: “Specific assets are assets that have a significantly higher value within a particular transacting relationship than outside the relationship.” Asset specificity goes a long way to explain why there isn’t a thick market for data as Lanier would like.

Third, data might be valued using cost-based methods. But, Chloe Mawer cautioned against using cost-based routes: “This method is highly imprecise for data, because data is often created as an intermediate product of other business processes.” In practice, I assume cost-based methods would probably look like Shapley values anyway.

Lastly, data can be valued through shadow prices. For those items that are rarely exchanged in a market, prices are often difficult to calculate and so other methods are used to appraise what is known as the shadow price. For example, a lake’s value might be determined by the total amount of time in lost wages and money spent by recreational users to get there. For each person, there is a shadow price for that lake.

Similarly, the value of social media can be calculated by tallying all of the forgone wages in using the site. A conservative estimate from a couple years back suggests that users spend about 20 hours a month on Facebook. Since the current average wage is about $28, this calculation indicates that people roughly value the site by about $6700 over the entire year. A study using data from 2016 using similar methods found that American adults consumed 437 billion hours of content on ad-supported media, worth at least $7.1 trillion in terms of foregone wages.

Shadow prices can also be calculated through surveys, which is where they get controversial. Depending on how the question is worded, users willingness to pay for privacy can be wildly variable. Trade association NetChoice worked with Zogby Analytics to find that only 16 percent of people are willing to pay for online platform service. Strahilevitz and Kugler found that 65 percent of email users, even though they knew their email service scans emails to serve ads, wouldn’t pay for alternative. As one seminal study noted, “most subjects happily accepted to sell their personal information even for just 25 cents.” Using differentiated smartphone apps, economists were able to estimate that consumers were willing to pay a one-time fee of $2.28 to conceal their browser history, $4.05 to conceal their list of contacts, $1.19 to conceal their location, $1.75 to conceal their phone’s identification number, and $3.58 to conceal the contents of their text messages. The average consumer was also willing to pay $2.12 to eliminate advertising.

All of this is to say that there is no one single way to estimate the value of data.

As for the Lanier piece, here are some other things to consider:

A market for data already exists. It just doesn’t include a set of participants that Jaron wants to include, which are platform users.

Will users want to be data entrepreneurs, looking for the best value for their data? Probably not. At best, they will hire an intermediary to do this, which is basically the job of the platforms already.

An underlying assumption is that the value of data is greater than the value advertisers are willing to pay for a slice of your attention. I’m not sure I agree with that.

Finally, how exactly do you write these kinds of laws?

September 10, 2019

Sen. Warren’s rural broadband plan and the 2% problem

Last month, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren released a campaign document, Plan for Rural America. The lion’s share of the plan proposed government-funded and -operated health care and broadband. The broadband section of the plan proposes raising $85 billion (from taxes?) to fund rural broadband grants to governments and nonprofits. The Senator then placed a Washington Post op-ed to decrying the state of rural telecommunications in America.

While addressing a worthy subject and it’s commendable she has a plan, more scrutiny of existing programs is needed. The Plan suffers from an unwarranted faith in the efficacy of government telecom subsidies. The op-ed misdiagnoses rural broadband problems and somehow lays decades of real and perceived failure of government policy at the feet of the current Trump FCC, and Chairman Pai in particular.

As a result, the proposed treatment–more public money, more government telecom programs–are the wrong treatment. The Senator’s plan to wire every household is undermined by “the 2% problem”–the cost to build infrastructure to the most remote homes is massive.

How dire is the problem?

Somewhere around 6% of Americans don’t have a 25 Mbps landline connection. But that means around 94% of Americans have access to 25 Mbps landline broadband. (Millions more have access if you include broadband from cellular and WISP providers.)

Further, rural buildout has been improving for years, despite the high costs. From 2013 to 2017, under Obama and Trump FCCs, landline broadband providers covered around 3 or 4 million new rural customers annually. This growth in coverage seems to be driven by unsubsidized carriers because, as I found in Montana, FCC-subsidized telecom companies in rural areas appear to be losing subscribers, even as universal service subsidies increased.

This rural buildout is more impressive when you consider that most people who don’t subscribe today simply don’t want Internet access. Somewhere between 55% to 80% of nonadopters don’t want it, according to Department of Commerce and Pew surveys. The fact is, millions of rural homes are connected annually despite the fact that most nonadopters today don’t want the service.

These are the core problems for rural telecom: (1) poorly-designed, overlapping, and expensive programs and (2) millions of consumers who are uninterested in subscribing to broadband. Other candidates (and perhaps President Trump) will come out with rural broadband plans so it’s worth diving into the issue. Doubling down on a 20 year old government policy–more subsidies to more providers–will mostly just entrench the current costly system.

Tens of billions for government-operated networks

The Senator’s $85 billion rural broadband plan is getting headlines. The grants would be restricted to nonprofits and government operators of networks. Senator Warren promises in her Plan for Rural America that, as President, she will “make sure every home in America has a fiber broadband connection.”

Every home?

This fiber-to-the-farm idea had advocates 10 years ago. The idea has failed to gain traction because it runs into the punishing economics of building networks. The real-world politics and government inefficiency also degrade lofty government broadband plans. For example, Australia’s construction of a nationwide publicly-owned fiber network–the nation’s largest-ever infrastructure project–is billions over budget and years behind schedule. The RUS broadband grant debacle in the US only supports the case that $85 billion simply doesn’t go that far. As Will Rinehart says, profit motive is not the cause of rural broadband problems. Government funding doesn’t fix the economics and the reality of government efficacy.

Costs rise non-linearly for the last few percent of households and $85 billion would bring fiber only to a small sliver of US households. According to estimates from the Obama FCC, it would cost $40 billion to build fiber to the final 2% of households alone. Further, those 2% of households would require an annual subsidy of $2 billion simply to maintain those networks since revenues are never expected to cover ongoing costs.

Recent history suggests rapidly diminishing returns and that $85 billion of taxpayer money will be misspent. Studies will probably be come out saying it can be done more cheaply but America has been running a similar experiment for 20 years. Since 1998, as economists Scott Wallsten and Lucía Gamboa point out, the US government has spent around $100 billion on rural telecommunications. It sure doesn’t feel like it. What does that $100 billion get? Mostly maintenance of existing rural networks and about a 2% increase of phone adoption.

The op-ed complains that:

the federal government has shoveled more than a billion in taxpayer dollars per year to private ISPs to expand broadband to remote areas, but these providers have done the bare minimum with these resources.

This understates the problem. The federal government “shovels” not $1 billion, but about $5 billion, annually to providers in rural areas, mostly from the Universal Service Fund Congress established in 1996.

As for the “public option for broadband”–extensive construction of publicly-run broadband networks–I’m skeptical. Broadband is not like a traditional utility. Unlike electricity, water, or sewer, a city or utility network doesn’t have a captive customer base. There are private operators out there.

As a result, public operation of networks is a risky way to spend public funds. Public and public-private operation of networks often leads to financial distress and bankruptcy, as Provo, Lake County, Kentucky, and Australia can attest.

Rural Telecom Reform

I’m glad Sen. Warren raised the issue of rural broadband, but the Plan’s drafters seem uninterested in digging into the extent of the problem and in solutions aside from throwing good money after bad. Lawmakers should focus on fixing the multi-billion dollar programs already in existence at the FCC and Ag Department, which are inexplicably complex, expensive to administer, and unequal towards ostensible beneficiaries.

Why, for instance, did rural telecom subsidies break down to about $11 per rural household in Sen. Warren’s Massachusetts in 2016 when it was about $2000 per rural household in Alaska?

Alabama and Mississippi have similar geographies and rural populations. So why did rural households in Alabama receive only about 20% of what rural Mississippi households receive?

Why have administrative costs as a percentage of the Universal Service Fund more than doubled since 1998? It costs $200 million annually to administer the USF programs today. (Compare to the FCC’s $333 million total budget request to Congress in FY 2019 for everything else the FCC does.)

I’ve written about reforms under existing law, like OTARD rule reform–letting consumers freely install small, outdoor antennas to bring broadband to rural areas–and transforming the current program funds into rural broadband vouchers. There’s also a role for cities and counties to help buildout by constructing long-lasting infrastructure like poles, towers, and fiber conduit. These assets could be leased out a low cost to providers.

Conclusion

After years of planning, the FCC reformed the rural telecom program in 2017, and it’s too early to evaluate the results. But the foundational problem is with the structure of existing programs. Fixing that structure should be a priority for any Senator or President concerned about rural broadband. Broadband vouchers for rural households would fix many of the problems, but lawmakers first need to question the universal service framework established over 20 years ago. It’s not fit for purpose.

September 9, 2019

Socialize Journalism in Order to Save It?

—–

by Adam Thierer & Andrea O’Sullivan

Anytime someone proposes a top-down, government-directed “plan for journalism,” we should be a little wary. Journalism should not be treated like it’s a New Deal-era public works program or a struggling business sector requiring bailouts or an industrial policy plan.

Such ideas are both dangerous and unnecessary. Journalism is still thriving in America, and people have more access to more news content than ever before. The news business faces serious challenges and upheaval, but that does not mean central planning for journalism makes sense.

Unfortunately, some politicians and academics are once again insisting we need government action to “save journalism.” Senator and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders (D-VT) recently penned an op-ed for the Columbia Journalism Review that adds media consolidation and lack of union representation to the parade of horrors that is apparently destroying journalism. And a recent University of Chicago report warns that “digital platforms” like Facebook and Google “present formidable new threats to the news media that market forces, left to their own devices, will not be sufficient” to continue providing high-quality journalism.

Critics of the current media landscape are quick to offer policy interventions. “The Sanders scheme would add layers of regulatory supervision to the news business,” notes media critic Jack Shafer. Sanders promises to prevent or rollback media mergers, increase regulations on who can own what kinds of platforms, flex antitrust muscles against online distributors, and extend privileges to those employed by media outlets. The academics who penned the University of Chicago report recommend public funding for journalism, regulations that “ensure necessary transparency regarding information flows and algorithms,” and rolling back liability protections for platforms afforded through Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

Both plans feature government subsidies, too. Sen. Sanders proposes “taxing targeted ads and using the revenue to fund nonprofit civic-minded media” as part of a broader effort “to substantially increase funding for programs that support public media’s news-gathering operations at the local level.” The Chicago plan proposed a taxpayer-funded $50 media voucher that each citizen will then be able to spend on an eligible media operation of their choice. Such ideas have been floated before and the problems are still numerous. Apparently, “saving journalism” requires that media be placed on the public dole and become a ward of the state. Socializing media in order to save it seems like a bad plan in a country that cherishes the First Amendment.

Forcing taxpayers to fund media outlets will lead to endless political fights. Those fights will grow worse once government officials are forced to decide which outlets qualify as “high-quality news” that can receive the money. Finally, and most problematic, is the fact that government money often comes with strings attached, and that means political meddling with the free speech rights or editorial discretion of journalists and news organizations.

Internet: Friend or Foe?

Grand plans to “save journalism” are peculiar because they come at a time when citizens enjoy unprecedented access to a veritable cornucopia of media platforms and inputs. A generation ago, critics lamented life in a world of media scarcity; today they complain about “information overload.” But if you asked Americans whether the internet gives them more or less access to media, most would probably quickly respond that it is a no-brainer: The internet provides us with access to content than ever before.

Whether it’s accessing traditional platforms like newspapers on their websites or broadcast media on YouTube or browsing new forms of internet-native content like social media reporting and podcasts, we suffer from no shortage of cheap and abundant data sources. The proliferation of smart devices means we can almost always plug in; so long as we have an internet connection, we can learn what’s going on in the world.

Given the choice between the abundance of information we have today—messy as it can be—and an era when a handful of anchors delivered just a half-hour of news each evening on one of the Big Three (ABC, CBS, NBC) television networks, and when many communities lacked access to other major news sources, how many of us would actually roll back the clock? Nobody in small town America ever got to read the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, or other national or global news sources before the internet came along.

Despite this virtual ocean of news content for consumers, many in politics, academia, and the media fret that journalism’s best days are behind us. Many of their concerns are actually quite old, however. People were fretting about the “death of news” long before the internet came along. The corresponding policy suggestions were also proposed in the past.

Now, as then, these “problems” may be misdiagnosed and the subsequent “solutions” are unlikely to be beneficial.

The Long Death of Media

Today, many are worried about the effect that Facebook and Google are having on the media landscape. It is true that the social media platforms currently earn around 60 percent of advertising revenues—income that traditional media outlets had traditionally relied upon to shore up subscription revenues.

But as many media scholars point out, journalism has always been something of a fraught economic endeavor. Although it is tempting to reminisce over a “golden age” of well-funded journalism, where handsomely paid dirt-diggers held power to account and brought truth to the public, in reality, journalist platforms have long had to adapt and rely on innovative funding sources and business models to stay afloat.

Market changes may make some outlets more profitable or sustainable in the short term, but the tendency is generally that journalism struggles to keep the press rolling. We should not, therefore, expect that policies can “fix” a journalism market that was never “fixable” to begin with. The economics of news production and dissemination remain challenging as ever and outlets will constantly need to reinvent themselves and their business models.

Similar concerns about the viability of journalism accompanied the rise of yesterday’s technologies: radio, television, and even at-home printing were all at one point thought to be the death knell of traditional print journalism. Yet print has remained, in one form or the other, and outlets learned to use disruptive new technologies to augment their reporting and better serve their audiences. Consumers have more options than ever despite lawmakers’ failure to act on the policy solutions that were offered during previous predictions of the same “death of journalism.”

Government Involvement Risks Dependence and Control

Proposals to subsidize media, even through a seemingly “decentralized” channel of taxpayer-directed (and funded) vouchers, is tempting for many of those worried about the future of a free press. Ironically, introducing government funding into the provision of media actually increases the risk that the media will be compromised.

Journalism subsidy proposals have been suggested for many years. Such plans inevitably invite greater government meddling with a free press. Consider the simple issue of determining which outlets should qualify for a government subsidy. After all, you can’t just allow people to hand out money to anyone. But if you allow a regulator to define eligible “journalists” or “news” you grant government greater power over the press. Controversies will ensue.

Should, say, Alex Jones be allowed to receive journalism vouchers? His supporters would think so, and they would have a strong First Amendment argument on their side. What about outfits associated with foreign governments or terrorist-designated groups? Each iteration grants more opportunity for ideological conflict.

And what if someone does not want their tax dollars to go to any platform at all? Should they be allowed to just get a tax rebate? Would this not defeat the entire purpose of the program? The political and legal complexities of this seemingly straightforward proposal quickly become clear.

Nor are the dangers with government control of media strictly hypothetical. We have several decades of case studies in the form of old Federal Communications Commission (FCC) policies. Whether its merger reviews, media ownership rules, or the fairness doctrine, history shows that when political appointees are granted the power to dictate content control—no matter how roundabout—they will often succumb. Nor or this a partisan phenomenon; authorities in both political parties have taken advantage when they could.

A “Solution” Should Not Exacerbate the Problem It Seeks to Overcome

Although the internet has increased the content options for consumers, it has also generated new challenges for news providers. This is not a new phenomenon, nor is it insurmountable. It will take time and ingenuity, but innovative news outlets will learn to survive and thrive in this new environment.

Patience is difficult, but it is a virtue. We should not allow our anxieties about the current state of a changing market to dictate policies that will ultimately cement government control of media content decisions. Soon enough, innovators will discover a new model that brings new sustainability for journalism for the next little while. And then, when that starts to wane, we’ll hear more calls for the government to get involved once again. It’s tempting, but ultimately self-defeating, and we should reject it now just as we have in the past.

On Robot Taxes and Workplace Automation Permission Slips

Originally published on the AIER blog on 9/8/19 as “The Worst Regulation Ever Proposed.”

———-

Imagine a competition to design the most onerous and destructive economic regulation ever conceived. A mandate that would make all other mandates blush with embarrassment for not being burdensome or costly enough. What would that Worst Regulation Ever look like?

Unfortunately, Bill de Blasio has just floated a few proposals that could take first and second place prize in that hypothetical contest. In a new Wired essay, the New York City mayor and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate explains, “Why American Workers Need to Be Protected From Automation,” and aims to accomplish that through a new agency with vast enforcement powers, and a new tax.

Unfortunately, Bill de Blasio has just floated a few proposals that could take first and second place prize in that hypothetical contest. In a new Wired essay, the New York City mayor and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate explains, “Why American Workers Need to Be Protected From Automation,” and aims to accomplish that through a new agency with vast enforcement powers, and a new tax.

Taken together, these ideas represent one of the most radical regulatory plans any America politician has yet concocted.

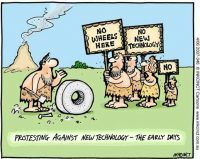

Politicians, academics, and many others have been panicking over automation at least since the days when the Luddites were smashing machines in protest over growing factory mechanization. With the growth of more sophisticated forms of robotics, artificial intelligence, and workplace automation today, there has been a resurgence of these fears and a renewed push for sweeping regulations to throw a wrench in the gears of progress. Mayor de Blasio is looking to outflank his fellow Democratic candidates for president with an anti-automation plan that may be the most extreme proposal of its kind.

First, de Blasio proposes a new federal agency, the Federal Automation and Worker Protection Agency (FAWPA), to “oversee automation and safeguard jobs and communities.” He continues:

FAWPA would create a permitting process for any company seeking to increase automation that would displace workers. Approval of those plans would be conditioned on protecting workers; if their jobs are eliminated through automation, the company would be required to offer their workers new jobs with equal pay, or a severance package in line with their tenure at the company.

Second, de Blasio proposed a “robot tax” that would be imposed on large companies “that eliminate jobs through increased automation and fail to provide adequate replacement jobs.” Those firms would “be required to pay five years of payroll taxes up front for each employee eliminated” and that revenue would be used to fund new infrastructure projects or jobs in new areas, including health care and green energy. “Displaced workers would be guaranteed new jobs created in these fields at comparable salaries,” he says.

Mayor de Blasio’s first idea would be one of the most far-reaching and destructive regulations in American history. A federal agency with “a permitting process for any company seeking to increase automation that would displace workers,” is essentially a political veto over workplace innovations at nearly every business in America. The result would be a de facto ban on productivity improvements across all professions.

After all, there aren’t too many sectors in the modern economy where automation isn’t playing at least a limited role. Even the oldest agricultural and industrial sectors and professions have undergone a certain amount of automation over time, and continue to do so today. These automation improvements have been essential to growing businesses and the economy more generally.

These automation advancements also create new and better jobs. It isn’t always clear initially how automation will affect workers, but the evolution of markets and innovations always provides interesting, and usually beneficial, surprises.

For example, in the early 1980s, many feared ATMs would make all bank tellers irrelevant. Instead, we got more bank workers, but they are now doing different jobs. How would de Blasio’s plan have worked back then? Would his regulatory permitting process have vetoed banking innovations such as ATMs or online banking in the name of protecting workers from automation and potential job losses, which never even materialized?

Now magnify this challenge across the entire American economy and ask how these decisions will be made for every business that is considering some form of workplace automation that could theoretically affect workers, but in ways that are difficult to foresee.

This is one reason why de Blasio’s proposal would quality for the Worst Regulation prize. It would let bureaucrats at the new Federal Automation and Worker Protection Agency sit in judgment of what constitutes beneficial forms of innovation and ask them to predict or plan our technological future.

This is a recipe for economic stagnation because these new FAWPA regulators would, like most other regulators, be incentivized to play it safe and disallow more automations than they approve. The precautionary principle would triumph over permissionless innovation; innovators would be treated as guilty until proven innocent in the resulting political circus.

Mayor de Blasio’s proposed robot tax is equally misguided. Robert D. Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, and Robert Seamans, associate professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, have both written about the dangers of the idea.

“The last thing policymakers should do is reduce the incentive for companies to invest in new machinery and equipment, as that would slow down needed productivity growth,” argues Atkinson in his study on, “The Case against Taxing Robots.” Likewise, Seamans notes that, in many cases, “robots are complements to labor, not substitutes for labor.” Therefore, “a robot tax would make it harder to achieve productivity growth,” and, he says, “may perversely lead to fewer rather than more jobs.”

Both scholars also point out the definitional difficulty associated with efforts to define what constitutes a “robot,” or “automation.” That problem will only be compounded once regulatory proceedings begin and various special interests begin lobbying lawmakers and regulators for favorable classifications and exemptions to avoid new rules and taxes—or get them imposed on potential competitors. Rather than helping consumers and workers, this will limit choices and drive up prices.

Importantly, regulating robots also means regulating their underlying software algorithms, which means Washington will need to send in teams of code cops to control programmers. At some point that could raise serious free speech issues since computer code can be a form of protected speech under the First Amendment. Practically speaking, however, we may not have to worry about that result because de Blasio’s command-and-control scheme would discourage many people from becoming programmers or roboticists in the first place. All those jobs and businesses would move offshore pretty quickly and America’s competitive standing would suffer globally.

It is tempting to dismiss Mayor de Blasio’s extreme proposals as a desperate move to appeal to the far-left wing of the Democratic Party base and win some more possible votes for the nomination. He likely won’t get the nomination, but his call for radical regulation of robotics in the name of protecting workers may move the party further toward the fringe by encouraging other candidates to concoct similar plans. Of course, it would be nearly impossible for any other candidate to outdo de Blasio’s plan without essentially just calling for an outright ban on robotics and all forms of automation altogether. Let’s hope that’s not next up in the competition for Worst Regulation Ever.

August 15, 2019

15 Years of the Tech Liberation Front: The Greatest Hits

The Technology Liberation Front just marked its 15th year in existence. That’s a long time in the blogosphere. (I’ve only been writing at TLF since 2012 so I’m still the new guy.)

Everything from Bitcoin to net neutrality to long-form pieces about technology and society were featured and debated here years before these topics hit the political mainstream.

Thank you to our contributors and our regular readers. Here are the most-read tech policy posts from TLF in the past 15 years (I’ve omitted some popular but non-tech policy posts).

No. 15: Bitcoin is going mainstream. Here is why cypherpunks shouldn’t worry. by Jerry Brito, October 2013

Today is a bit of a banner day for Bitcoin. It was five years ago today that Bitcoin was first described in a paper by Satoshi Nakamoto. And today the New York Times has finally run a profile of the cryptocurrency in its “paper of record” pages. In addition, TIME’s cover story this week is about the “deep web” and how Tor and Bitcoin facilitate it.

The fact is that Bitcoin is inching its way into the mainstream.

No. 14: Is fiber to the home (FTTH) the network of the future, or are there competing technologies? by Roslyn Layton, August 2013

There is no doubt that FTTH is a cool technology, but the love of a particular technology should not blind one to look at the economics. After some brief background, this blog post will investigate fiber from three perspectives (1) the bandwidth requirements of web applications (2) cost of deployment and (3) substitutes and alternatives. Finally it discusses the notion of fiber as future proof.

No. 13: So You Want to Be an Internet Policy Analyst? by Adam Thierer, December 2012

Each year I am contacted by dozens of people who are looking to break into the field of information technology policy as a think tank analyst, a research fellow at an academic institution, or even as an activist. Some of the people who contact me I already know; most of them I don’t. Some are free-marketeers, but a surprising number of them are independent analysts or even activist-minded Lefties. Some of them are students; others are current professionals looking to change fields (usually because they are stuck in boring job that doesn’t let them channel their intellectual energies in a positive way). Some are lawyers; others are economists, and a growing number are computer science or engineering grads. In sum, it’s a crazy assortment of inquiries I get from people, unified only by their shared desire to move into this exciting field of public policy.

. . . Unfortunately, there’s only so much time in the day and I am sometimes not able to get back to all of them. I always feel bad about that, so, this essay is an effort to gather my thoughts and advice and put it all one place . . . .

No. 12: Violent Video Games & Youth Violence: What Does Real-World Evidence Suggest? by Adam Thierer, February 2010

So, how can we determine whether watching depictions of violence will turn us all into killing machines, rapists, robbers, or just plain ol’ desensitized thugs? Well, how about looking at the real world! Whatever lab experiments might suggest, the evidence of a link between depictions of violence in media and the real-world equivalent just does not show up in the data. The FBI produces ongoing Crime in the United States reports that document violent crimes trends. Here’s what the data tells us about overall violent crime, forcible rape, and juvenile violent crime rates over the past two decades: They have all fallen. Perhaps most impressively, the juvenile crime rate has fallen an astonishing 36% since 1995 (and the juvenile murder rate has plummeted by 62%).

No. 11: Wedding Phtography and Copyright Release by Tim Lee, September 2008

I’m getting married next Spring, and I’m currently negotiating the contract with our photographer. The photography business is weird because even though customers typically pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars up front to have photos taken at their weddings, the copyright in the photographs is typically retained by the photographer, and customers have to go hat in hand to the photographer and pay still more money for the privilege of getting copies of their photographs.

This seems absurd to us . . . .

No. 10: Why would anyone use Bitcoin when PayPal or Visa work perfectly well? by Jerry Brito, December 2013

A common question among smart Bitcoin skeptics is, “Why would one use Bitcoin when you can use dollars or euros, which are more common and more widely accepted?” It’s a fair question, and one I’ve tried to answer by pointing out that if Bitcoin were just a currency (except new and untested), then yes, there would be little reason why one should prefer it to dollars. The fact, however, is that Bitcoin is more than money, as I recently explained in Reason. Bitcoin is better thought of as a payments system, or as a distributed ledger, that (for technical reasons) happens to use a new currency called the bitcoin as the unit of account. As Tim Lee has pointed out, Bitcoin is therefore a platform for innovation, and it is this potential that makes it so valuable.

No. 9: The Hidden Benefactor: How Advertising Informs, Educates & Benefits Consumers by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka, February 2010

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. . . . This regulatory tsunami could not come at a worse time, of course, since an attack on advertising is tantamount to an attack on media itself, and media is at a critical point of technological change. As we have pointed out repeatedly, the vast majority of media and content in this country is supported by commercial advertising in one way or another-particularly in the era of “free” content and services.

No. 8: Reverse Engineering and Innovation: Some Examples by Tim Lee, June 2006

Reverse engineering the CSS encryption scheme, by itself, isn’t an especially innovative activity. However, what I think Prof. Picker is missing is how important such reverse engineering can be as a pre-condition for subsequent innovation. To illustrate the point, I’d like to offer three examples of companies or open source projects that have forcibly opened a company’s closed architecture, and trace how these have enabled subsequent innovation . . . .

No. 7: Are You An Internet Optimist or Pessimist? The Great Debate over Technology’s Impact on Society by Adam Thierer, January 2010

The cycle goes something like this. A new technology appears. Those who fear the sweeping changes brought about by this technology see a sky that is about to fall. These “techno-pessimists” predict the death of the old order (which, ironically, is often a previous generation’s hotly-debated technology that others wanted slowed or stopped). Embracing this new technology, they fear, will result in the overthrow of traditions, beliefs, values, institutions, business models, and much else they hold sacred.

The pollyannas, by contrast, look out at the unfolding landscape and see mostly rainbows in the air. Theirs is a rose-colored world in which the technological revolution du jour is seen as improving the general lot of mankind and bringing about a better order. If something has to give, then the old ways be damned! For such “techno-optimists,” progress means some norms and institutions must adapt—perhaps even disappear—for society to continue its march forward.

No. 6: Copyright Duration and the Mickey Mouse Curve by Tom Bell, August 2009

Given the rough-and-tumble of real world lawmaking, does the rhetoric of “delicate balancing” merit any place in copyright jurisprudence? The Copyright Act does reflect compromises struck between the various parties that lobby congress and the administration for changes to federal law. A truce among special interests does not and cannot delicately balance all the interests affected by copyright law, however. Not even poetry can license the metaphor, which aggravates copyright’s public choice affliction by endowing the legislative process with more legitimacy than it deserves. To claim that copyright policy strikes a “delicate balance” commits not only legal fiction; it aids and abets a statutory tragedy.

No. 5: Cyber-Libertarianism: The Case for Real Internet Freedom by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka, August 2009

Generally speaking, the cyber-libertarian’s motto is “Live & Let Live” and “Hands Off the Internet!” The cyber-libertarian aims to minimize the scope of state coercion in solving social and economic problems and looks instead to voluntary solutions and mutual consent-based arrangements.

Cyber-libertarians believe true “Internet freedom” is freedom from state action; not freedom for the State to reorder our affairs to supposedly make certain people or groups better off or to improve some amorphous “public interest”—an all-to convenient facade behind which unaccountable elites can impose their will on the rest of us.

No. 4: Here’s why the Obama FCC Internet regulations don’t protect net neutrality by Brent Skorup, July 2017

It’s becoming clearer why, for six years out of eight, Obama’s appointed FCC chairmen resisted regulating the Internet with Title II of the 1934 Communications Act. Chairman Wheeler famously did not want to go that legal route. It was only after President Obama and the White House called on the FCC in late 2014 to use Title II that Chairman Wheeler relented. If anything, the hastily-drafted 2015 Open Internet rules provide a new incentive to ISPs to curate the Internet in ways they didn’t want to before.

No. 3: 10 Years Ago Today… (Thinking About Technological Progress) by Adam Thierer, February 2009

As I am getting ready to watch the Super Bowl tonight on my amazing 100-inch screen via a Sanyo high-def projector that only cost me $1,600 bucks on eBay, I started thinking back about how much things have evolved (technologically-speaking) over just the past decade. I thought to myself, what sort of technology did I have at my disposal exactly 10 years ago today, on February 1st, 1999? Here’s the miserable snapshot I came up with . . . .

No. 2: Regulatory Capture: What the Experts Have Found by Adam Thierer, December 2010

While capture theory cannot explain all regulatory policies or developments, it does provide an explanation for the actions of political actors with dismaying regularity. Because regulatory capture theory conflicts mightily with romanticized notions of “independent” regulatory agencies or “scientific” bureaucracy, it often evokes a visceral reaction and a fair bit of denialism. . . . Yet, countless studies have shown that regulatory capture has been at work in various arenas: transportation and telecommunications; energy and environmental policy; farming and financial services; and many others.

No. 1: Defining “Technology” by Adam Thierer, April 2014

I spend a lot of time reading books and essays about technology; more specifically, books and essays about technology history and criticism. Yet, I am often struck by how few of the authors of these works even bother defining what they mean by “technology.” . . . Anyway, for what it’s worth, I figured I would create this post to list some of the more interesting definitions of “technology” that I have uncovered in my own research.

August 14, 2019

TLF at 15: Let the Great Adventure Continue

Today marks the 15th anniversary of the launch of the Technology Liberation Front. This blog has evolved through the years and served as a home for more than 50 writers who have shared their thoughts about the intersection of technological innovation and public policy.

Many TLF contributors have moved on to start other blogs or

write for other publications. Others have gone into other professions where

they simply can’t blog anymore. Still others now just publish their daily

musings on Twitter, which has had a massive substitution effect on long-form blogging

more generally. In any event, I’m pleased that so many of them had a home here

at some point over the past 15 years.

What has unified everyone who has written for the TLF is (1)

a strong belief in technological innovation as a method of improving the human

condition and (2) a corresponding concern about impediments to technological

change. Our contributors might best be labeled “rational

optimists,” to borrow Matt Ridley’s phrase, or “dynamists,” to use Virginia

Postrel’s term. In a

recent essay, I sketched out the core tenets of a dynamist, rational optimist

worldview, arguing that we:

believe there is a symbiotic relationship

between innovation, economic growth, pluralism, and human betterment, but also

acknowledge the various challenges sometimes associated with technological

change;look forward to a better future and reject

overly nostalgic accounts of some supposed “good ‘ol days” or bygone better

eras;base our optimism on facts and historical

analysis, not on blind faith in any particular viewpoint, ideology, or gut

feeling;support practical, bottom-up solutions to hard

problems through ongoing trial-and-error experimentation, but are not wedded to

any one process to get the job done;appreciate entrepreneurs for their willingness

to take risks and try new things, but do not engage in hero worship of any

particular individual, organization, or particular technology.

Applying that vision, the contributors here through the

years have unabashedly defended a pro-growth, pro-progress, pro-freedom vision,

but they have also rejected techno-utopianism or gadget-worship of any sort. Rational

optimists are anti-utopians, in fact, because they understand that hard

problems can only be solved through ongoing trial and error, not wishful

thinking or top-down central planning.

Wisdom and progress are directly correlated with society’s

willingness to experiment with new ideas, tolerate change, and learn from

failures. Writing in 1960, Nobel Prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek wisely

observed that many intellectuals, “ignore the importance of the freedom of

doing things” and that “[f]reedom of action, even in humble things, is as important

as freedom of thought.” The two are

inextricably linked, in fact. Technology is simply a means to an end and that

end is material progress and human flourishing. The goal is to expand the range

of life-enriching innovations available to people while also empowering them pursue

lives of their own choosing. But experimentation and freedom of action are

absolutely crucial if we hope to achieve that end.

When thinking about public policy, “freedom of doing things”

can be reconceptualized as “permissionless

innovation.” Generally speaking, innovation and innovators should be

treated as innocent until proven guilty. When forces—governmental or otherwise—conspire

to constrain the general freedom to innovate, they are, in reality, constraining

human creativity and learning, thus limiting our efforts to improve the world

around us.

There can be no greater revolution than the revolution to liberate

the human mind. It is peaceful, collaborative revolution aimed at breaking the

chains that bind our ingenuity and which curtail our ability to pursue

happiness however each of us define it. Accordingly, removing barriers to people

building more and better tools to improve their lot in life has been a priority

of much of the writing here on the TLF.

When searching for a quote to end my next book, I settled on

one from Samuel C. Florman, an

engineer who throughout his life rose to the challenge of defending

technological innovation with remarkable gusto. Commenting on the swelling

ranks of “antitechnologists” he saw around him a generation ago, Florman

perfectly identified the profound danger of giving up on finding new and better

ways of doing things. “By turning our backs on technological change, we would

be expressing our satisfaction with current world levels of hunger, disease,

and privation,” he argued. “Further, we must press ahead in the name of the

human adventure. Without experimentation and change our existence would be a

dull business.”

Defending that “human adventure” has been the goal of all

those contributing to the Tech Liberation Front over the past 15 years because experimentation

and change are the key to our very survival as a species. I’m looking forward to seeing what the next

15 years of this adventure brings and hope to work with others here and

elsewhere to make sure that all citizens of the world get to enjoy the fruits

of human ingenuity and technological creativity.

August 13, 2019

What is Progress Studies?

This essay was originally published on the AIER blog on August 8, 2019.

In a new Atlantic essay, Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen suggest that, “We Need a New Science of Progress,” which, “would study the successful people, organizations, institutions, policies, and cultures that have arisen to date, and it would attempt to concoct policies and prescriptions that would help improve our ability to generate useful progress in the future.” Collison and Cowen refer to this project as Progress Studies.

Is such a field of study possible, and would it really be a “science”? I think the answer is yes, but with some caveats. Even if it proves to be an inexact science, however, the effort is worth undertaking.

Thinking about Progress

Progress Studies is a topic I have spent much of my life thinking and writing about, most recently in my book, Permissionless Innovation as well as a new paper on “Technological Innovation and Economic Growth,” co-authored with James Broughel. My work has argued that nations that are open to risk-taking, trial-and-error experimentation, and technological dynamism (i.e., “permissionless innovation”) are more likely to enjoy sustained economic growth and prosperity than those rooted in precautionary principle thinking and policies (i.e., prior restraints on innovative activities). A forthcoming book of mine on the future of entrepreneurialism and innovation will delve even deeper into these topics and address criticisms of technological advancement.

Of course, many other people have been thinking about Progress Studies for centuries now. Political scientists, historians, and economists have long studied what makes some countries and civilizations prosper while others falter or fade away. Business school scholars have also spent time thinking about what drives global competitive advantage and national prosperity. There also exists an entire field called Science and Technology Studies (STS) that incorporates a wide variety of “soft science” academic disciplines, including law, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, and others that analyze the relationship between technology, society, culture, and politics.

Taken together, these academic disciplines might already constitute the Progress Studies initiative that Collison and Cowen desire. The problem is that these different camps do not talk to each other as much as they should because existing scholarship often “takes place in a highly fragmented fashion and fails to directly confront some of the most important practical questions,” Collison and Cowen argue. That limits our understanding of what drives progress and prosperity.

Economists mostly talk about progress with other economists, and historians mostly hang out with other historians. What they might have to tell us about Progress Studies, therefore, will not be as rich had it been cross-saturated with lessons from each other’s disciplines. The same holds for many other academic fields.

In theory, Science and Technology Studies is supposed to remedy this problem by encouraging cross-disciplinary thinking and research integration. To the extent it accomplishes that objective, however, it is only because STS scholars tend to be hostile to technological innovation and traditional definitions of prosperity. For many of them, the benefits of innovation are dubious, and the metrics traditionally used to measure progress (like Gross Domestic Product and Total Factor Productivity) are considered bogus or secondary to other considerations.

When thinking about of technology, STS scholars commonly employ words like “anxiety,” “alienation,” “degradation,” and “discrimination.” Consequently, most of them suggest that the burden of proof lies squarely on scientists, engineers, and innovators to prove that their ideas and inventions will bring worth to society before they are deployed. In other words, STS scholars generally fall in the precautionary principle camp, and their policy prescriptions have grown increasingly radical over time.

Differing Conceptions of Progress

No one better analyzed the anti-technological radicalism of modern STS scholars than Samuel C. Florman. Chances are you never heard of him, but had Progress Studies been an official field of academic study over that past century, Florman would be considered one of its leading exemplars. Alas, Florman was an engineer writing about these issues in yet another very different fashion, and his work has not gained much currency among scholars in other fields.

In books like The Existential Pleasures of Engineering (1976) and Blaming Technology: The Irrational Search for Scapegoats (1981), Florman meticulously dissected the arguments made by STS scholars and other “antitechnologists,” as he called them. While STS critics are fond of labelling themselves “humanists” and suggesting that innovation-boosters are naïve, uncaring oafs, Florman pushed back with zeal and argued it was they who were betraying humanity by denying the fundamental link between innovative dynamism and human flourishing.

“Anyone who has attempted to defend technology against the reproaches of an avowed humanist,” Florman noted, “soon discovers that beneath all the layers of reasoning—political, environmental, aesthetic, or moral—lies a deep-seated disdain for ‘the scientific view.’” This makes conversations between STS scholars and other disciplines (especially economists and business theorists) quite challenging.

Florman’s critiques of STS scholars were trenchant, and lest you think he was exaggerating about the growing radicalism of that camp, one need only scroll halfway through Collison and Cowen’s essay to find the Atlantic recommending an earlier article the site ran by a historian with the title, “Is ‘Progress’ Good for Humanity?” The author blasted the “unstoppable way toward more growth and more technology,” and, “the assumption [] that these things are ultimately beneficial for humanity.” It is hard to imagine that author being comfortable being part of Collison and Cowen’s Progress Studies program, but his perspective is widely shared throughout STS today.

Innovation Culture

So, getting scholars from different disciplines to talk to each other—even when they agree about the importance of innovation or what we mean by progress—will be a challenge. However, that also represents the greatest opportunity for Progress Studies to do some good. Progress Studies can also help us itemize some of the factors that mainstream scholars have long considered essential to growth and prosperity.

Collison and Cowen suggest that “there can be ecosystems that are better at generating progress than others, perhaps by orders of magnitude. But what do they have in common? Just how productive can a cultural ecosystem be?” Beyond gaining a better understanding of how innovation ecosystems work, they also want to nurture them. “Can we deliberately engineer the conditions most hospitable to this kind of advancement or effectively tweak the systems that surround us today?” they ask.

In my last book and in essays like “Embracing a Culture of Permissionless Innovation,” I argue that, to some extent, leaders and institutions can help create conditions more hospitable to progress by understanding the importance of getting “innovation culture” right. No two modern scholars have written more eloquently and voluminously on this point than Joel Mokyr and Deirdre McCloskey.

Mokyr has argued that technological innovation and economic progress can be viewed as “a fragile and vulnerable plant, whose flourishing is not only dependent on the appropriate surroundings and climate, but whose life is almost always short. It is highly sensitive to the social and economic environment and can easily be arrested by relatively small external changes.” McCloskey’s work has shown that cultural attitudes, social norms, and political pronouncements have had a profound and underappreciated influence on opportunities for entrepreneurialism, innovation, and long-term economic growth.

We can be more concrete about the various attitudes, ideas, institutions, and policies that create the building blocks of a vibrant innovation ecosystem. Many scholars have surveyed the elements that contribute to a successful innovation culture and their lists typically include:

trust in the individual / openness to individual achievements;positive attitudes towards competition and wealth-creation (especially religious openness toward commercial activity and profit-making);support for hard work, timeliness, and efficiency;willingness to take risks and accept change (including failure);a long-term outlook;openness to new information / tolerance of alternative viewpoints;freedom of movement and travel for individuals and organizations (including flexible immigration and worker mobility policies);positive attitudes towards science and development;advanced education systems;support for property rights and contracts; reasonable regulations and taxes;impartial administration of justice and the respect for the rule of law; and,stable government institutions and transfers of power.

Each of these factors has been studied and refined to identify the necessary ingredients of a vibrant innovation ecosystem. There really isn’t any great mystery to what belongs on this list anymore. Instead, the two hard questions that remain are which factors are most important and how do we foster and sustain social and political support for those ideas and institutions?

What’s the Goldilocks Formula?

The first question leads to heated debates, even among scholars who generally agree on most other matters. Everyone seems to have their own favored idea or institution which they believe is most vital to unlocking opportunities for growth and progress. But how do we dial-in those ingredients, and in what measure? Are advanced education systems more important than strong property rights or R&D funding? Does the rule of law matter more than societal willingness to take risks? And so on.

It is tempting to respond that all these things are important, but that is not a very satisfying answer. We should be able to better determine which factors are most important. On the other hand, imagining that there is Goldilocks formula for getting things just right and “engineering progress” seems a bit hubristic. While Collison and Cowen’s Progress Studies initiative should make unlocking that formula a priority, it is important to acknowledge the limits of our knowledge and understand that this will continue to be a highly inexact science. Only through ongoing experimentation (and plenty of failures) with different systems and policies can we gain greater wisdom.

The second question is even harder to address. How do we shift cultural and political attitudes about innovation and progress in a more positive direction? Collison and Cowen explicitly state that the goal of Progress Studies transcends “mere comprehension” in that it should also look to “identify effective progress-increasing interventions and the extent to which they are adopted by universities, funding agencies, philanthropists, entrepreneurs, policy makers, and other institutions.”

But fostering social and political attitudes conducive to innovation is really more art than science. Specifically, it is the art of persuasion. Science can help us amass the facts proving the importance of innovation and progress to human improvement. Communicating those facts and ensuring that they infuse culture, institutions, and public policy is more challenging.

To solve that conundrum, Collison and Cowen’s Progress Studies initiative should devote more energy to gleaning insights from fields like communications studies, rhetoric and argumentation theory, as well as marketing, advertising, and even psychology. What Progress Studies needs is a better plan for communicating what we already know to be effective in advancing the progress and prosperity of peoples, cultures, institutions, and nations. That is no easy task, but when the future of humanity depends upon it, it seems like a challenge worth undertaking.

In the meantime, perhaps we can at least start developing a curriculum of important books on these topics. Here are 20 books that I think can help us develop a more holistic understanding of what we mean by Progress Studies and the values and policies than can drive it.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty (New York: Crown Business. 2012).Amar Bhidé, The Venturesome Economy: How Innovation Sustains Prosperity in a More Connected World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).Tyler Cowen, Stubborn Attachments: A Vision for a Society of Free, Prosperous, and Responsible Individuals (San Francisco, CA: Stripe Press, 2018).Arthur M. Diamond Jr., Openness to Creative Destruction: Sustaining Innovative Dynamism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).Samuel C. Florman, The Existential Pleasures of Engineering (New York, St. Martins Griffin, 2nd Edition, 1994).Robert D. Friedel, A Culture of Improvement: Technology and the Western Millennium (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2007).Lawrence Harrison and Samuel Huntington (eds.), Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress (New York: Perseus Books Group, 2000).Calestous Juma, Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies(New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).David Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some are So Poor (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1998).Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).Joel Mokyr, A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017).Joel Mokyr, Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).Richard R. Nelson and Sidney G. Winter, An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1982).Robert Nisbet, History of the Idea of Progress (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1994).Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge University Press, 1990).Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York: Viking, 2018).Michael Porter, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (New York: Free Press, 1990).Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies (New York: The Free Press, 1998).Matt Ridley, The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves (New York: Harper Collins, 2010).Nathan Rosenberg and L. E.. Birdzell, How the West Grew Rich: The Economic Transformation of the Industrial World (New York: Basic Books, 1986).

August 1, 2019

Sen. Hawley’s Radical, Paternalistic Plan to Remake the Internet

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) recently delivered remarks at the National Conservatism Conference and a Young America’s Foundation conference in which he railed against political and academic elites, arguing that, “the old era is ending and the old ways will not do.” “It’s time that we stood up to big government, to the people in government who think they know better,” Hawley noted at the YAF event. “[W]e are for free competition… we are for the free market.”

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) recently delivered remarks at the National Conservatism Conference and a Young America’s Foundation conference in which he railed against political and academic elites, arguing that, “the old era is ending and the old ways will not do.” “It’s time that we stood up to big government, to the people in government who think they know better,” Hawley noted at the YAF event. “[W]e are for free competition… we are for the free market.”

That’s all nice-sounding rhetoric but it sure doesn’t seem to match up with Hawley’s recent essays and policy proposals, which are straight out of the old era’s elitist and highly paternalistic Washington-Knows-Best playbook. Specifically, Hawley has called for a top-down, technocratic regulatory regime for the Internet and the digital economy more generally. Hawley has repeatedly made claims that digital technology companies have gotten a sweetheart deal from government and they they have censored conservative voices. That’s utter nonsense, but those arguments have driven his increasingly fanatic rhetoric and command-and-control policy proposals. If he succeeds in his plan to empower unelected bureaucrats inside the Beltway to reshape the Internet, it will destroy one of the greatest American success stories in recent memory. It’s hard to understand how that could be labelled “conservative” in any sense of the word.

I’ve been tracking Sen. Hawley’s increasingly radical plans for the digital economy in a series of essays, including:

“Sen. Hawley’s Moral Panic Over Social Media“

“How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality“

“The White House Social Media Summit and the Return of ‘Regulation by Raised Eyebrow’“

“The Not-So-SMART Act“

In these articles, I have documented how Sen. Hawley has been whipping up a panic about digital technology companies and social media platforms to soften to ground for massive intervention by DC elites. Consider his hotly-worded USA Today op-ed from May in which he argued that, “social media wastes our time and resources,” and is “a field of little productive value” that have only “given us an addiction economy.” Sen. Hawley refers to sites like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter as “parasites” and blames them for a litany of social problems (including an unproven link to increased suicide). He has even suggested that, “we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared” and seems to hope the same for other sites.

More insultingly, he has argued that the entire digital economy was basically one giant mistake. He says that America’s recent focus on growing the Internet and information technology sectors has “encouraged a generation of our brightest engineers to enter a field of little productive value,” which he regards as “an opportunity missed for the nation.” “What marvels might these bright minds have produced,” Hawley asks, “had they been oriented toward the common good?”

Again, this isn’t the sort of rhetoric that conservatives are usually known for. This is elitist, paternalistic tripe that we usually hear from market-hating neo-Marxists. It takes a lot of hubris for Sen. Hawley to suggest that he knows best which professions or sectors are in “the common good.” As I responded in one of my essays:

Had some benevolent philosopher kings in Washington stopped the digital economy from developing over the past quarter century, would all those tech workers really have chosen more noble-minded and worthwhile professions? Could he or others in Congress really have had the foresight to steer us in a better direction?

Why would Sen. Hawley think DC elites could do a better job centrally planning the economy? He doesn’t really tell us, instead preferring to fall back on conspiratorial rhetoric about evil “Big Tech” companies “censoring” conservatives voices. That’s the same card he played when he joined President Trump at the White House for the surreal, rambling “Social Media Summit” that took place last month. Trump used the same approach that Sen. Hawley and Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) have been using during recently Senate Judiciary Committee hearings: brow-beat witnesses and make wild claims about the whole digital world being out to muzzle conservative voices. As Andrea O’Sullivan and I noted in about the Social Media Summit:

The President and other conservatives are tapping another approach: indirect censorship through both subtle and direct threats. This is an old playbook that goes by many different names: “jawboning,” “administrative arm-twisting,” “agency threats,” and “regulation by raised eyebrow.” These were the names given to broadcast-era efforts to pressure old radio and TV outlets to bring their programming choices in line with the desires of politicians and bureaucrats.

This is an old DC playbook that elites have used for decades to “work the refs” and try to extract promises from various parties under threat of more far-reaching regulation if they fail to comply with the demands of politicians. Again, there’s nothing remotely “conservative” about it.

Brushing aside such concerns, Sen. Hawley has started sketching out what a comprehensive regulatory regime for the Internet and social media might look like. He does so in two new bills, the “Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act” (co-sponsored by Sen. Cruz) and the “Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology (SMART) Act.” These two measures, if implemented, would radically remake the digital economy and lead to a remarkably intrusive regulatory regime for online speech and commerce.

The ridiculously named “Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act” would actually encourage the exact opposite result than its title suggests. The proposal would mandate that regulators at the Federal Trade Commission evaluate whether platforms have engaged in “politically biased moderation,” which is defined as moderation practices that are supposedly, “designed to negatively affect” or those that “disproportionately [restrict] or promote access to … a political party, political candidate, or political viewpoint.” Social media providers would need to petition the FTC for “immunity certifications” to then get regular audits to ensure they are moderating content in a government-approved manner. If they didn’t, they would lose their platform liability protections, which could effectively run them out of business.

This is permission slip-based regulation and it makes the old Federal Communications Commission licensing regime for broadcast radio and television look like child’s play by comparison. Hawley’s “Mother, May I?” licensing scheme for the Net would have unelected FTC bureaucrats make speech decisions for the entire Internet. It’s a massive First Amendment violation, and it would almost certainly face constitutional challenge if implemented.

What makes this all the more shocking, as I noted in response, this measure combines core elements of the old Fairness Doctrine as well as “net neutrality” mandates that conservatives have traditionally decried. The bill would also empower insider-the-Beltway lawyers, lobbyists, and consultants, who would be needed to navigate the maze of red tape this measure would give rise to. Worst of all, the measure is a massive gift to the trial lawyers Republicans love to hate because Hawley’s new regulatory regime would empower them to file an endless string of frivolous suits aimed at simply shaking down companies through early settlements. Again, how is this “conservative”?

Then there’s Hawley’s new “SMART Act,” which as Andrea O’Sullivan and I argue in our latest essay is really quite stupid. The highly technocratic measure lists a variety of business practices that would be automatically verboten. As Andrea and I summarize: