Adam Thierer's Blog, page 18

July 18, 2019

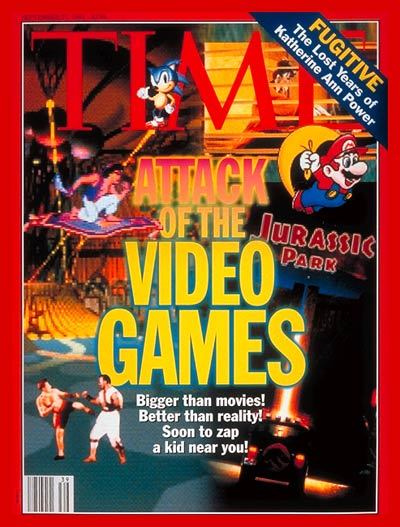

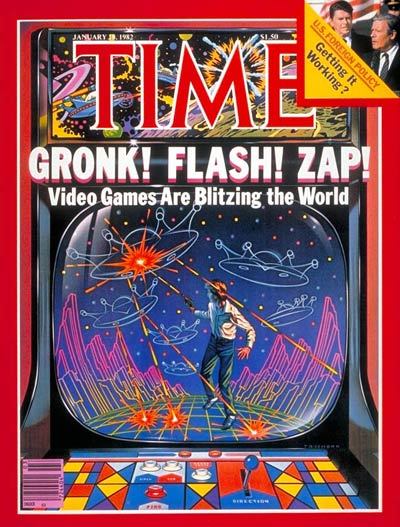

50 Years of Video Games & Moral Panics

This essay originally appeared on The Bridge under the title “Confessions of a Vidiot” on July 16, 2019.

_________________

I have a confession: I’m 50 years old and still completely in love with video games.

I feel silly saying that, even though I really shouldn’t. Video games are now fully intertwined with the fabric of modern life and, by this point, there have been a couple of generations of adults who, like me, have played them actively over the past few decades. Somehow, despite the seemingly endless moral panics about video games, we came out alright. But that likely will not stop some critics from finding new things to panic over.

I feel silly saying that, even though I really shouldn’t. Video games are now fully intertwined with the fabric of modern life and, by this point, there have been a couple of generations of adults who, like me, have played them actively over the past few decades. Somehow, despite the seemingly endless moral panics about video games, we came out alright. But that likely will not stop some critics from finding new things to panic over.

As a child of the 1970s, I straddled the divide between the old and new worlds of gaming. I was (and remain) obsessed with board and card games, which my family played avidly. But then Atari’s home version of “Pong” landed in 1976. The console had rudimentary graphics and controls, and just one game to play, but it was a revelation. After my uncle bought Pong for my cousins, our families and neighbors would gather round his tiny 20-inch television to watch two electronic paddles and a little dot move around the screen.

Every kid in the world immediately began lobbying their parents for a Pong game of their own, but then a year later something even more magical hit the market: Atari’s 2600 gaming platform. It was followed by Mattel’s “Intellivision” and Coleco’s “ColecoVision.” The platform wars had begun, and home video games had gone mainstream.

My grandmother, who lived with us at the time, started calling my brother and me “vidiots,” which was short for “video game idiots.” My grandmother raised me and was an absolute treasure to my existence, but when it came to video games (as well as rock music), the generational tensions between us were omnipresent. She was constantly haranguing my brother and me about how we were never going to amount to much in life if we didn’t get away from those damn video games!

I used to ask her why she never gave us as much grief about playing board or card games. She thought those were mostly fine. There was just something about the electronic or more interactive nature of video games that set her and the older generation off.

And, of course, there was the violence. There is no doubt that video games contained violent themes and images that were new to the gaming experience. In the analog gaming era, violent action was left mostly to the imagination. With electronic games, it was right there for us to see in all its (very bloody) glory.

As depictions of violence in video games became more intense, parental anxiety boiled over into political activism. By the early 1990s, complaints by parent groups and politicians escalated and congressional hearings commenced. This was the Nintendo and Sega era, when games like “Mortal Kombat” and “Night Trap” were capturing attention for their violent themes.

By this time, I had moved to Washington, DC and taken a job with a think tank. I was a young researcher covering media and telecommunications policy issues, so I had both a personal and professional interest in covering video game hearings. What ensued was a media spectacle in which an endless parade of politicians and self-anointed “parent advocates” expressed their concerns about various games and the supposed lost generation of kids playing them.

The first major congressional hearing on video game violence that I attended in 1993 included then-Sen. Joe Lieberman and other lawmakers speaking with disgust and furrowed brows as they watched clips from those games. But most of us twenty-somethings in the hearing room were rolling our eyes through the entire spectacle. I distinctly remember hearing a Capitol Hill staffer that I was sitting next to whisper, “This is the greatest ad for getting a Sega Genesis ever!” Following the hearing, several friends and I went to my house and played Mortal Kombat together just for kicks.

As the decade went on and gamers began enjoying a third generation of consoles that included Playstation and XBox, the moral panic surrounding violent video gamesrapidly intensified. This was the era of “Doom,” “Resident Evil” and then “Grand Theft Auto.” The whole world went mad.

Critics were writing books with titles like Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill and referring to video games as “murder simulators.” Every TV news outlet was running some sort of hair-raising report about how America’s youth were doomed for a life of depravity due to video games. By 2006, Sen. Lieberman and then-Sen. Hillary Clinton were floating the “Family Entertainment Protection Act” to create a federal enforcement regime for video games ratings and sales. Court battles ensued over the constitutionality of restrictions on video game sales.

During this push for video game censorship, I wrote many essays, papers, and even contributed to court filings in which I poured over the evidence—or rather the lack thereof—for what we might think of as the “monkey see-monkey do” theory of human behavior. Put simply, there has never been any conclusive scientific evidence correlating video game exposure and real-world acts of violence. If this theory held any water, at some point it should have shown up in crime statistics either here or abroad. But it hasn’t.

In fact, over the past two decades, the US population has grown from 270 million in 1998 to 325 million today, and video games have grown in popularity over that same period. At the same time, according to FBI data, overall violent crime has fallen by almost 19 percent, and for adolescents ages 12 to 20, every class of crime plummeted over the same period.

To be sure, video games—violent or otherwise—can give rise to some problems worth worrying about. Addiction is a real concern, and not just for juveniles. Again, I’m an old man, but I still play far too many games on my phone when I could be doing other things. That’s not technically addiction, but it sure feels like it sometimes. When our kids, or even some adults, go overboard with game time, they need strategies to find a better balance. That has always been a legitimate issue deserving attention.

But the people and politicians who engaged in panics and proselytizing about the supposed evils of video games went much too far. What they failed to realize—as almost all cultural critics have mistakenly done throughout history—is that humans are more sensible and resilient than they assume. We can muddle through and find a reasonable balance.

Indeed, a great many first and second generation gamers are now raising kids and actively gaming with them. My teenage son and I play multiple games together and are part of many different leagues and teams. On our phones, we play “Boom Beach” and other games together, often with groups of other father and son gamers. At home, we love to play “Star Wars: Battlefront” and we are absolutely infatuated with the alien bug-killing “Earth Defense Force” games.

A few years back, my son and I got so good at the game “Toy Soldiers: Cold War” that we were briefly ranked in the top 15 globally. We also play a lot of board games together. I now include him in monthly poker nights at my house, where he has become quite the card shark, regularly depriving many of my adult friends of their money.

My strategy with my son and gaming activity has been simple: stay involved, be open-minded, and set reasonable limits. Oh sure, there are games he plays that I find silly and worthless. But I try to talk to him about all of them and get a better understanding of what they are about. And I encourage him—not always successfully—to get off the couch and go outside to get plenty of outdoor playtime in, too.

While heavy-handed regulatory efforts have been beaten back, we can expect moral panics to continue as video games become even more interactive and immersive. We aging gamers should be willing to hear out concerns about those new gaming themes and capabilities and consider reasonable responses.

If we have learned anything from the first half century of video game history, it is that over-reaction is never the right response. Whether you are a parent or a politician, try to be patient and willing to talk to kids in an open and understanding fashion about things you might not appreciate at first.

Now please excuse me while my son and I get back to killing some alien bugs and saving the Earth once more!

_________________

Additional Reading :

The Social Science Debate over Violent Video Games Will Never End

Video Games, Media Violence & the Cathartic Effect Hypothesis

More on Monkey See-Monkey Do Theories about Media Violence & Real-World Crime

Video Games, Free Speech & the Lunacy of “Ecogenerism”

Video Games and “Moral Panic”

Video Games, Violence, & Social “Science”: Another Day, Another Fight

July 15, 2019

Did You Need Another Reason to Hate Lobbyists & Cronyism?

My latest AIER column examines the impact increased lobbying and regulatory accumulation have on entrepreneurialism and innovation more generally. Unsurprisingly, it’s not a healthy relationship. A growing body of economic evidence concludes that increases in the former lead to much less of the latter.

This is a topic that my Mercatus Center colleagues and I have done a lot of work on through the years. But what got me thinking about the topic again was a new NBER working paper by economists Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon entitled, “The Failure of Free Entry.” Their new study finds that “regulations and lobbying explain rather well the decline in the allocation of entry” that we have seen in recent years.

Many economists have documented how business dynamism–new firm creation, entry, churn, etc–appears to have slowed in the US. Explanations for why vary but Gutiérrez and Philippon show that, “regulations have a negative impact on small firms, especially in industries with high lobbying expenditures.” Their results also document how regulations, “have a first order impact on incumbent profits and suggest that the regulatory capture may have increased in recent years.”

In other words, lobbying and cronyism breed a culture of rent-seeking, over-regulation, and rule accumulation that directly limit new startup activity and innovation more generally. This is a recipe for economic stagnation if left unchecked.

I cite almost a dozen sources in my essays which document this problem in far greater detail and which propose a variety of reforms. In a previous essay for AIER, I argued a periodic “spring cleaning for the regulatory state” was essential if we hope to address regulatory accumulation. In continued:

For starters, we need to get the problem of over-licensing and over-permitting under control at the federal, state, and local level. While sometimes justified, licenses are a direct restriction on entry and entrepreneurialism and should only be employed for the riskiest activities and professions. “Permissionless innovation” should be the default.

Other regulatory reforms will be needed, and I continue to be a big fan of “sunsets” as one way of cleaning out the stables. Sunsets are not silver-bullet solutions, but they can help create a periodic reset button of sorts for government programs or regulations that have outlived their usefulness, or did not make sense to begin with.

Some people will push back against such regulatory reforms, suggesting they will undermine public health or welfare. But that’s nonsense. Getting regulatory accumulation under control isn’t just about improving opportunities for innovation, entrepreneurialism, and worker opportunities. It’s also about ensuring that government functions in more efficient and effective fashion.

When regulations accumulate without any rhyme or reason, it makes it more difficult for public officials to do their jobs effectively. Streamlining rules and cleaning up old, outdated regs will help public officials better serve the public interest and give economic dynamism a boost at the same time.

We need to get serious about getting this problem under control. Again, read my latest and previous AIER columns for more detail about how we can start that process.

July 8, 2019

There are good reasons to be skeptical that automation will unravel the labor market

When it comes to the threat of automation, I agree with Ryan Khurana: “From self-driving car crashes to failed workplace algorithms, many AI tools fail to perform simple tasks humans excel at, let alone far surpass us in every way.” Like myself, he is skeptical that automation will unravel the labor market, pointing out that “[The] conflation of what AI ‘may one day do’ with the much more mundane ‘what software can do today’ creates a powerful narrative around automation that accepts no refutation.”

Khurana marshals a number of examples to make this point:

Google needs to use human callers to impersonate its Duplex system on up to a quarter of calls, and Uber needs crowd-sourced labor to ensure its automated identification system remains fast, but admitting this makes them look less automated…

London-based investment firm MMC Ventures found that out of the 2,830 startups they identified as being “AI-focused” in Europe, 40% used no machine learning tools, whatsoever.

I’ve been collecting examples of the AI hype machine as well. Here are some of my favorites.

From Rodney Brooks comes this corrective:

Chris Urmson, the former leader of Google’s self-driving car project, once hoped that his son wouldn’t need a driver’s license because driverless cars would be so plentiful by 2020. Now the CEO of the self-driving startup Aurora, Urmson says that driverless cars will be slowly integrated onto our roads “over the next 30 to 50 years.”

Judea Pearl, a pioneer in statistics, said last year that “All the impressive achievements of deep learning amount to just curve fitting,” a technique that was developed decades ago.

Earlier this year, IBM shut down its Watson AI tool for drug discovery.

Mike Mallazzo said it this way: “The investors know it’s bullshit. When venture capitalists say they are looking to add ‘A.I. companies’ to their portfolio, what they really want is a technological moat built around access to uniquely valuable data. If it’s beneficial for companies to sprinkle in a little sex appeal and brand this as ‘A.I.,’ there’s no incentive to stop them from doing so.”

And there is the problem of cost:

Google’s DeepMind lost roughly $162 million in 2016.

Facebook might have access to vast engineering resources and data about language, but still their chatbot project, M, fell short. According to one source familiar with the program, M never surpassed 30 percent automation.

Ocado, the UK-based online supermarket, explained in late 2017 that the company would need to spend “an extra couple of million pounds” to hire software engineers to work on automating its warehouses.

Facebook tried to largely automate their content moderation process, but had to pull back on the project and has instead upped the number of content moderators.

After years of development, T-Mobile got rid of its robotic customer service lines.

BMW and Daimler, long time competitors, have been to create autonomous vehicles because of the astronomical costs involved.

Uber recently raised a $1 billion for its autonomous vehicles unit.

McDonald’s purchased Silicon Valley VC-backed AI company Dynamic Yield, which was reportedly for over $300 million, making it the fast-food giant’s largest acquisition since it bought Boston Market in 1999.

Ford invested nearly a $1 billion in Argo for its work in autonomous vehicles.

Johnson & Johnson paid $3.4 billion to pick up surgical robotics pioneer Auris Health, and its FDA-cleared Monarch platform in March.

Total private investment into AI businesses in the United Kingdom exceeded £3.8 billion in 2018.

SAS intends to spend $1 billion on AI research in the coming three years.

According to data from CB Insights, a record $9.3 billion went to U.S.-based AI startups in 2018, an $8.2 billion increase from the $1.1 billion raised in 2013.

As I explained before, the large pecuniary costs in big data technologies don’t speak to the equally expensive task of overhauling management techniques to make the new systems work. New technologies can’t be seamlessly adopted within firms, they need management and process innovations to make the new data-driven methods profitable. And to be honest, we just aren’t there yet.

July 2, 2019

Black Mirror Episodes from Medieval Times

CollegeHumor has created this amazing video, “Black Mirror Episodes from Medieval Times,” which is a fun parody of the relentless dystopianism of the Netflix show “Black Mirror.” If you haven’t watched Black Mirror, I encourage you to do so. It’s both great fun and ridiculously bleak and over-the-top in how it depicts modern or future technology destroying all that is good on God’s green earth.

The CollegeHumor team picks up on that and rewinds the clock about a 1,000 years to imagine how Black Mirror might have played out on a stage during the medieval period. The actors do quick skits showing how books become sentient, plows dig holes to Hell and unleash the devil, crossbows destroy the dexterity of archers, and labor-saving yokes divert people from godly pursuits. As one of the audience members says after watching all the episodes, “technology will truly be the ruin of us all!” That’s generally the message of not only Black Mirror, but the vast majority of modern science fiction writing about technology (and also a huge chunk of popular non-fiction writing, too.)

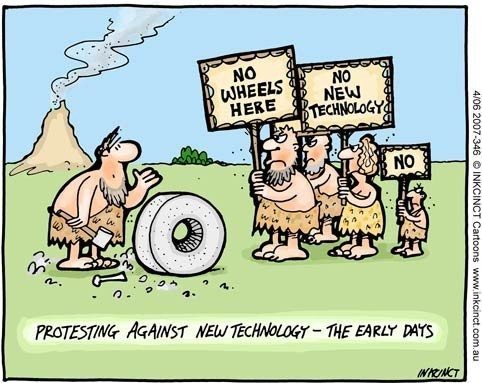

If you go far enough back in the history of technology and technological criticism, you actually can find plenty of people insisting that the latest and greatest tech of the day would be the ruin of us all. As I noted here before, you can trace tech criticism at least back to Plato’s Phaedrus, which warned about the dangers of the written word. My colleague Tyler Cowen argues you can trace it even further back to the Bible and the Book of Genesis, especially the story of the Tower of Babel.

One can almost imagine how scorn was heaped on the first person to fashion a blade or a wheel out of stone. Before his untimely passing a few years ago, the great Calestous Juma used to occasionally tweet this hilarious cartoon that depicted just that moment in time. The people that carry those “NO” signs are still all around us today. Technopanics and fear cycles just repeat endlessly, as I have noted in dozens of essays and papers through the years.

June 26, 2019

Urban air mobility news

The urban air mobility stories keep stacking up in 2019. A few highlights and a few thoughts.

Commercial developments

There have been tons of urban air mobility announcements, partnerships, and demos in 2019. EHang, the Chinese drone maker, seems to be farthest along in eVTOL development, though many companies are working with regulators to bring about eVTOL services in the next five years.

In April, representatives said EHang will start selling its two-passenger, autonomous eVTOL next year for about $350,000 to commercial operators. Ehang’s co-founder says its 2-passenger autonomous eVTOL is already completing routine flights in China for tourists between a hotel and local attractions.

Uber recently announced they’ll offer shared-ride helicopter service between Manhattan and JFK airport, starting in July. This week, Voom (Airbus) announced they will expand their helicopter ridesharing service to San Francisco. They’ve been operating in Sao Paulo and Mexico City already.

These helicopter rides are targeting popular urban routes (airport-to-airport, CBD-to-airport, etc.) for customers who are willing to pay to shorten a one-hour car ride to a ten-minute helicopter ride. Fees are typically $150 to $250 one-way. Both companies want to get a sense of demand, price, and frequency for eVTOL services.

What’s the Plan?

This makes the development of airspace markets and unmanned traffic management (UTM) systems all the more urgent. What regulators must guard against is first-movers squatting on high-revenue aerial routes.

Airspace is nominally a common-pool resource, rationed via regulation and custom. That worked tolerably well for the Wright brother era and the jet age. Still, there are massive distortions and competitive problems because an oligopoly of first movers attained popular routes and airport terminals. The common-pool resource model for airspace also leaves regulators with few tools to ration access sensibly.

From my airspace policy paper:

For example, in 1968, nearly one-third of peak-time New York City air traffic—the busiest region in the United States—was general aviation (that is, small, personal) aircraft. To combat severe congestion, local authorities raised minimum landing fees by a mere $20 (1968 dollars) on sub 25-seat aircraft. General aviation traffic at peak times immediately fell by more than 30 percent, suggesting that a massive amount of pre-July 1968 air traffic in the region was low value. The share of aircraft delayed by 30 or more minutes fell from 17 percent to about 8 percent. Similarly, Logan Airport raised fees on small aircraft in the 1980s in order to lessen congestion. The scheme worked, and general aviation traffic fell by about one-third, though the fee hike was later overturned.

There’s a revolution in aviation policy occurring. The arrival of drones, eVTOL, and urban air mobility requires a totally different framework. It seems inevitable that a layer-cake or corridor approach to airspace management will develop, even though the FAA currently resists that. As with American frontier or radio spectrum: a demand shock to Ostromian common pool resource leads to enclosure and property rights.

Already, first movers and the government are collaborating on UTM and airspace policy. But regulators must resist letting collaboration today degrade into oligopoly tomorrow. This early collaboration on technology and norms is necessary but the regulators will be under immense pressure, inside and outside the agency, to have a single UTM provider, or a few hand-picked vendors.

A single UTM system or a tightly-integrated system with a few private system operators would reproduce many of the problems with today’s air traffic management. It is very hard to update information-rich systems, especially air traffic control systems, the delayed, over-budget NextGen modernization shows. Today there are 16,000 FAA workers working on the NextGen project, which has been ongoing since 1983. UTM will be an even more information-rich system. An system-wide upgrade to UTM would make NextGen modernization look simple by comparison.

Further, once the urban air mobility market develops, the first movers (UTM and eVTOL operators) will resist newcomers and new UTM technologies in the future. Exclusive aerial corridors, as opposed to shared corridors planned for today by regulators, would allow competitive UTM systems with only basic interoperability requirements.

Quick Hits

NETT Council: In March, USDOT Secretary Chao announced the formation of the Non-Traditional and Emerging Transportation Technology Council. It sounds great, and one of the likely topics the Council will take up is urban air mobility.

ASI Aviation Report, “Taking Off”: The Adam Smith Institute (UK) this week published an excellent report from Matthew Lesh about improving competition and service in aviation. The UK often leads the world in deregulation and market-based management of government property (like AIP in spectrum policy), and ASI has been influential in aviation policy in particular. Report highlights:

Analysis of terminal competition policies for Heathrow (which is in the midst of a major expansion project)Proposes additional slot auctions for takeoff and landing slots at UK airportsEndorses aerial corridor auctions for air taxis and eVTOL

Government study of airspace auctions: My proposal that the FAA auction aerial corridors for eVTOL caught the attention of the FAA’s Drone Advisory Committee and was included in a working group’s 2018 report about ways to finance drone and eVTOL regulation. Section 360 of the FAA Reauthorization Act, passed a few months after the working group report came out, then instructed the GAO to study ways of financing drone and eVTOL regulation. The law specifies that the GAO must study the six proposals in that working group report, including the auction of aerial corridors.

Lincoln Network Conference: I recently had the privilege of speaking at the Lincoln Network’s Reboot American Innovation conference. Jamie Boone (CTA) and I gave a fireside chat about the fast-moving urban air mobility sector. Matt Parlmer, founder of Ohlogen, was a great moderator. Video here.

eVTOL in North Carolina: The North Carolina state appropriations bill, which is nearing passage, allocates some funds to the Lt. Governor’s office to study eVTOLs, consult with experts, and convene an eVTOL summit in the next year. The Lt. Governor might also form a state advisory committee on eVTOL, a good, forward-looking policy for states given the rapid pace of progress in urban air mobility. To my knowledge, North Carolina is the first state to dedicate funding for study of this industry.

June 19, 2019

How Conservatives Came to Favor the Fairness Doctrine & Net Neutrality

I have been covering telecom and Internet policy for almost 30 years now. During much of that time – which included a nine year stint at the Heritage Foundation — I have interacted with conservatives on various policy issues and often worked very closely with them to advance certain reforms.

If I divided my time in Tech Policy Land into two big chunks of time, I’d say the biggest tech-related policy issue for conservatives during the first 15 years I was in the business (roughly 1990 – 2005) was preventing the resurrection of the so-called Fairness Doctrine. And the biggest issue during the second 15-year period (roughly 2005 – present) was stopping the imposition of “Net neutrality” mandates on the Internet. In both cases, conservatives vociferously blasted the notion that unelected government bureaucrats should sit in judgment of what constituted “fairness” in media or “neutrality” online.

Many conservatives are suddenly changing their tune, however. President Trump and Sen. Ted Cruz, for example, have been increasingly critical of both traditional media and new tech companies in various public statements and suggested an openness to increased regulation. The President has gone after old and new media outlets alike, while Sen. Cruz (along with others like Sen. Lindsay Graham) has suggested during congressional hearings that increased oversight of social media platforms is needed, including potential antitrust action.

Meanwhile, during his short time in office, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) has become one of the most vocal Internet critics on the Right. In a shockingly-worded USA Today editorial in late May, Hawley said, “social media wastes our time and resources” and is “a field of little productive value” that have only “given us an addiction economy.” He even referred to these sites as “parasites” and blamed them for a long list of social problems, leading him to suggest that, “we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared” along with various other sites and services.

Hawley’s moral panic over social media has now bubbled over into a regulatory crusade that would unleash federal bureaucrats on the Internet in an attempt to dictate “fair” speech on the Internet. He has introduced an astonishing piece of legislation aimed at undoing the liability protections that Internet providers rely upon to provide open platforms for speech and commerce. If Hawley’s absurdly misnamed new “Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act” is implemented, it would essentially combine the core elements of the Fairness Doctrine and Net Neutrality to create a massive new regulatory regime for the Internet.

The bill would gut the immunities Internet companies enjoy under 47 USC 230 (“Section 230”) of the Communications Decency Act. Eric Goldman of the Santa Clara University School of Law has described Section 230 as the “best Internet law” and “a big part of the reason why the Internet has been such a massive success.” Indeed, as I pointed out in a Forbes column on the occasion of its 15th anniversary, Section 230 is “the foundation of our Internet freedoms” because it gives online intermediaries generous leeway to determine what content and commerce travels over their systems without the fear that they will be overwhelmed by lawsuits if other parties object to some of that content.

The Hawley bill would overturn this important legal framework for Internet freedom and instead replace it with a new “permissioned” approach. In true “Mother-May-I” style, Internet companies would need to apply for an “immunity certification” from the FTC, which would undertake investigations to determine if the petitioning platform satisfied a “requirement of politically unbiased content moderation.”

The vague language of the measure is an open invitation to massive political abuse. The entirety of the bill hinges upon the ability of Federal Trade Commission officials to define and enforce “political neutrality” online. Let’s consider what this will mean in practice.

Under the bill, the FTC must evaluate whether platforms have engaged in “politically biased moderation,” which is defined as moderation practices that are supposedly, “designed to negatively affect” or “disproportionately restricts or promote access to … a political party, political candidate, or political viewpoint.” As Blake Reid of the University of Colorado Law School rightly asks, “How, exactly, is the FTC supposed to figure out what the baseline is for ‘disproportionately restricting or promoting’? How much access or availability to information about political parties, candidates, or viewpoints is enough, or not enough, or too much?”

There is no Goldilocks formula for getting things just right when it comes to content moderation. It’s a trial-and-error process that is nightmarishly difficult because of the endless eye-of-the-beholder problems associated with constructing acceptable use policies for large speech platforms. We struggled with the same issues in the broadcast and cable era, but they have been magnified a million-fold in the era of the global Internet with the endless tsunami of new content that hits our screens and devices every day. “Do we want less moderation?” asks Sec, 230 guru Jeff Kosseff. “I think we need to look at that question hard. Because we’re seeing two competing criticisms of Section 230,” he notes. “Some argue that there is too much moderation, others argue that there is not enough.”

The Hawley bill seems to imagine that a handful of FTC officials will magically be able to strike the right balance through regulatory investigations. That’s a pipe dream, of course, but let’s imagine for a moment that regulators could somehow sort through all the content on message boards, tweets, video clips, live streams, gaming sites, and whatever else, and then somehow figure out what constituted a violation of “political neutrality” in any given context. That would actually be a horrible result because let’s be perfectly clear about what that would really be: It would be a censorship board. By empowering unelected bureaucrats to make decisions about what constitutes “neutral” or “fair” speech, the Hawley measure would, as Elizabeth Nolan Brown of Reason summarizes, “put Washington in charge of Internet speech.” Or, as Sen. Ron Wyden argues more bluntls, the bill “will turn the federal government into Speech Police.”

The measure is creating other strange bedfellows. You won’t see Berin Szoka of TechFreedom and Harold Feld of Public Knowledge ever agreeing on much, but they both quickly and correctly labelled Hawley’s bill a “Fairness Doctrine for the Internet.” That is quite right, and much like the old Fairness Doctrine, Hawley’s new Internet speech control regime would be open to endless political shenanigans as parties, policymakers, companies, and the various complainants line up to have their various political beefs heard and acted upon. “That’s the kind of thing Republicans said was unconstitutional (and subject to FCC agency capture and political manipulation) for decades,” says Daphne Keller of the Stanford Center for Internet & Society. Moreover, during the Net Neutrality holy wars, GOP conservatives endlessly blasted the notion that bureaucrats should be determining what constitute “neutrality” online because it, too, would result in abuses of the regulatory process. Yet, Sen. Hawley’s bill would now mandate that exact same thing.

What is even worse is that, as law professor Josh Blackman observes, “the bill also makes it exceedingly difficult to obtain a certification” because applicants need a supermajority of 4 of the 5 FTC Commissioners. This is public choice fiasco waiting to happen. Anyone who has studied the long, sordid history of broadcast radio and television licensing understands the danger associated with politicizing certification processes. The lawyers and lobbyists in the DC “swamp” will benefit from all the petitioning and paperwork, but it is not clear how creating a regulatory certification regime for Internet speech really benefits the general public (or even conservatives, for that matter).

Former FTC Commissioner Josh Wright identifies another obvious problem with the Hawley Bill: it “offers the choice of death by bureaucratic board or the plaintiffs’ bar.” That’s because by weakening Sec. 230’s protections, Hawley’s bill could open the floodgates to waves of frivolous legal claims in the courts if companies can’t get (or lose) certification. The irony of that result, of course, is that this bill could become a massive gift to the tort bar that Republicans love to hate!

Of course, if the law ever gets to court, it might be ruled unconstitutional. “The terms ‘politically biased’ and ‘moderation’ would have vagueness and overbreadth problems, as they can chill protected speech,” Josh Blackman argues. So it could, perhaps, be thrown out like earlier online censorship efforts. But a lot of harm could be done—both to online speech and competition—in the years leading up to a final determination about the law’s constitutionality by higher courts.

What is most outrageous about all this is that the core rationale behind Hawley’s effort—the idea that conservatives are somehow uniquely disadvantaged by large social media platforms—is utterly preposterous. In May, the Trump Administration launched a “tech bias” portal which “asked Americans to share their stories of suspected political bias.” The portal is already closed and it is unclear what, if anything, will come out of this effort. But this move and Hawley’s proposal point the broader trend of conservatives getting more comfortable asking Big Government to redress imaginary grievances about supposed “bias” or “exclusion.”

In reality, today’s social media tools and platforms have been the greatest thing that ever happened to conservatives. Trump owes his presidency to his unparalleled ability to directly reach his audience through Twitter and other platforms. As recently as June 12, Trump tweeted, “The Fake News has never been more dishonest than it is today. Thank goodness we can fight back on Social Media.” Well, there you have it!

Beyond the President, one need only peruse any social media site for a few minutes to find an endless stream of conservative perspectives on display. This isn’t exclusion; it’s amplification on steroids. Conservatives today have more soapboxes to stand on and preach today than ever before in the history of this nation.

Finally, if they were true to their philosophical priors, then conservatives also would not be insisting that they have any sort of “right” to be on any platform. These are private platforms, after all, and it is outrageous to suggest that conservatives (or any other person or group) are entitled to have a spot on any other them.

Some conservatives are fond of ridiculing liberals for being “snowflakes” when it comes to other free speech matters, such as free speech on college campuses. Many times they are right. But one has to ask who the real snowflakes are when conservative lawmakers are calling on regulatory bureaucracies to reorder speech on private platform based on the mythical fear of not getting “fair” treatment. One also cannot help but wonder if those conservatives have thought through how this new Internet regulatory regime will play out once a more liberal administration takes back the reins of power. Conservatives will only have themselves to blame when the Speech Police come for them.

_____________

Additional thoughts on the Hawley bill:

June 15, 2019

Reviving the Office of Technology Assessment would require a set of specific conditions in Congress. We have simply not arrived at that time.

Cato Unbound is taking on the issue of tech expertise this month and the lead essay came from Kevin Kosar, who argues for the revival of the Office of Technology Assessment. As he explains,

[N]o one wants Congress enacting policies that make us worse off, or that delay or stifle technologies that improve our lives. And yet this kind of bad policy happens with lamentable frequency. Pluralistic politics inevitably features some self-serving interests that are more powerful and politically persuasive than others. This is why government often undertakes bailouts and other actions that are odious to the public writ large.

He continues, “Congress’s ineptitude in [science and technology policy] has been richly displayed.” To help embed expertise in science and technology policy, Kosar argues for the revival of the Office of Technology Assessment, which was established in 1972 and defunded in 1995.

I have been on the OTA beat for a little while now, and so I offered some criticism of Kosar’s proposal, which you can find here. I’ll lay out my cards: I’ve been skeptical of reving the OTA in the past and I remain so. Here is my key graf on that:

Elsewhere, I have argued that the OTA should be seen as a last resort; there are other ways of embedding expertise in Congress, like boosting staff and reforming hiring practices. The following essay makes a slightly different argument, namely, that the history of the OTA shows the razor wire on which a revived version of agency will have to balance. In its early years, the OTA was dogged by accusations of partiality. Having established itself as a neutral party throughout the 1980s, the OTA was abolished because it failed to distinguish itself among competing agencies. There is an underlying political economy to expertise that makes the revival of the OTA difficult, undercutting it as an option for expanding tech expertise. In a modern political environment where scientific knowledge is politicized and budgets are tight, the OTA would likely face the hatchet once again.

The OTA wasn’t supposed to be just a tech assessment office, but also an outside government agency that could check the Executive. The legislative history underpins that goal:

While members wanted the OTA to help understand an increasingly complex world, congressional architects also thought it would redress an imbalance of federal power that favored the White House. Speaking in favor of the creation of the OTA in May 1970, Missouri Democrat James Symington emphasized that, “We have tended simply to accede to administration initiatives, which themselves from time to time may have been hastily or inaccurately promoted.” When the bill came to the floor in 1972, Republican Representative Charles Mosher noted, “Let us face it, Mr. Chairman, we in the Congress are constantly outmanned and outgunned by the expertise of the executive agencies.” Writing on the eve of its demise, a historian of the agency explained that, “the most important factor in establishing the OTA was a desire on the part of Congress for technical advice independent of the executive branch.”

The demand for the OTA at its genesis was twofold, for knowledge as Kosar explains, but also for power. I doubt Democrats or the Republicans today would “simply to accede to administration initiatives,” as both had a tendency to do in the 1960s. The agency was created at a time when both sides of Congress wanted to check the president. It was a solution to an intertwined set of problems. While the tenor in Congress could swiftly change, a groundswell of bipartisan support for an OTA would be needed before any efforts to revive it could be effective. A revival would need to be a compromise that both parties and both chambers of Congress could agree to. We have simply not arrived at that time.

But there are solutions to sidestep the reinvigoration of a standalone agency. In line with my suggestions from last year, the General Accounting Office is expanding their tech assessment program. Congress also needs to reform their staffing processes to encourage stability and reduce turnover. None of these proposals, however, will make headway in changing congressional offices back toward their orientation in the early 1990s. In a follow up post over at Cato, I will explore the challenges that any reform will face when trying to solve the problem of tech expertise.

June 7, 2019

There Was No “Golden Age” of Broadcast Regulation

Slate recently published an astonishing piece of revisionist history under the title, “Bring Back the Golden Age of Broadcast Regulation,” which suggested that the old media regulatory model of the past would be appropriate for modern digital media providers and platforms. In the essay, April Glaser suggests that policymakers should resurrect the Fairness Doctrine and a host of old Analog Era content controls to let regulatory bureaucrats address Digital Age content moderation concerns.

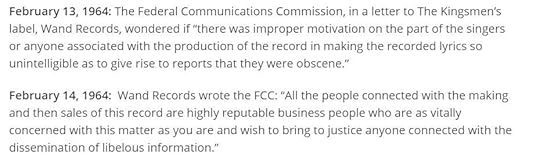

In a tweetstorm, I highlighted a few examples of why the so-called Golden Era wasn’t so golden in practice. I began by noting that the piece ignores the troubling history of FCC speech controls and unintended consequences of regulation. That regime gave us limited, bland choices–and a whole host of First Amendment violations. We moved away from that regulatory model for very good reasons.

For those glorifying the Fairness Doctrine, I encourage them to read the great Nat Hentoff’s excellent essay, “The History & Possible Revival of the Fairness Doctrine,” about the real-world experience of life under the FCC’s threatening eye. Hentoff notes:

Others were harassed in ways that were both humorous and horrifying. For example, go back and review the amazing FCC (and FBI!) investigation of The Kingsmen’s song “Louie Louie,” due to fears about its unintelligible lyrics:

Or go back and read former CBS president Fred Friendly’s 1975 book (The Good Guys, the Bad Guys & the First Amendment) about abuses of the Fairness Doctrine during both Republican and Democratic administrations. This stuff from Kennedy years, which I summarized in old book, is quite shocking:

And then there was the “golden era” of broadcast regulation under Nixon, where regulatory harassment intensified to counter what had happened during Democratic administrations. Here’s Jesse Walker summarizing those dark days:

Also read Tom Hazlett on the Nixon years and all the broadcast meddling that happened on a ongoing basis. “License harassment of stations considered unfriendly to the Administration became a regular item on the agenda at White House policy meetings,” he notes. And then even the Smothers Brothers became victims!

This is how Tom Hazlett perfectly summarized the choice before us regarding whether to let regulatory bureaucracies decide what is “fair” in media. This is exactly the same question we should be asking today when people suggest reviving the old “golden era” media control regime.

Keep in mind, the examples of content meddling cited here most involve the Fairness Doctrine. Indecency rules, the Financial Interest and Syndication Rules, and other FCC policies gave politicians others levers of exerting influence and control over speech. The meddling was endless.

This was no “Golden Era” or broadcast regulation–unless, that is, you prefer bland, boring, limited choices and endless bureaucratic harassment of media. No amount of wishful thinking or revisionist history can counter the hard realities of that dismal era in our nation’s history. We should wholeheartedly and vociferously reject calls to resurrect it.

June 3, 2019

The net neutrality fight continues, this time in Colorado

Two weeks ago, Gov. Polis signed a bill that generally cuts off Colorado state funds from ISPs that commit “net neutrality violations” in the state. Oddly, I’ve seen no coverage from national outlets and barely a mention from local outlets. Perhaps journalists and readers have tired from what Larry Downes has dubbed the net neutrality farce, a debate about Internet regulation that has distracted the FCC and lawmakers for over a decade.

There’s not much new in the net neutrality debate, but Colorado did tread new ground: a House amendment to allow ISPs to filter adult content barely failed, on a tied vote 32-32. Net neutrality in the US runs into First Amendment and Section 230 problems, and that amendment is the first time I’ve seen the issue raised by a state legislature.

A few thoughts on the law because in March I was invited to testify before a Colorado House committee about net neutrality, broadband, and the policy implications of the then-pending bill. I commended the bill drafters for scrupulously attempting to narrow their bill to intra-state consumer protection issues. Nevertheless, it was my view that the Colorado law, as written, wouldn’t survive judicial review if litigated.

States can have agreements with vendors and contractors and can require them to abide by certain contractual terms. However, courts have held that states cannot, as Seth Cooper has pointed out, use their contractual relationships with firms to extract concessions that are “tantamount to regulation.” State agencies cannot attempt an end-around federal laws that prevent state regulation of Internet services generally, and net neutrality regulation in particular.

My testimony:

Good afternoon. My name is Brent Skorup and I am a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. I also serve on the Broadband Deployment Advisory Committee of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

It is commendable that state legislatures, governors, and cities around the country, including in Colorado, are prioritizing broadband deployment. The focus should remain on the pressing broadband issues of competition and deployment. The political battles in Washington, DC, about net neutrality, which I have observed over the past decade, have alarmingly spread to statehouses in recent months, and they will distract from far more important issues.

Lawmakers should enter the debate with their eyes wide open about the stakes and the unintended effects of internet regulation. By imposing network management rules on certain providers, SB 19-078 conflicts with federal policy, codified in the Telecommunications Act, that internet access should be “unfettered by Federal or State regulation.”

First, net neutrality laws and regulations do not accomplish what they purportedly accomplish. As the FCC revealed when it defended its net neutrality regulations in federal court in 2016, any no-blocking rule is mostly unenforceable. As a tech journalist put it, internet service providers (ISPs) can “exempt [themselves] from the net neutrality rules”—the rules are “essentially voluntary.” The same problem arises with state net neutrality laws.

Second, state internet regulations are unlikely to survive judicial review. Internet access is inherently interstate: simply streaming a YouTube video or sending an email often transmits data across state lines. State attempts to regulate treatment of internet access therefore likely violate federal law, which vests authority to regulate interstate communications with the FCC.

Third, the bill penalizes small, rural carriers. There’s a saying in politics: “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” It appears that Colorado’s rural broadband providers are “on the menu.” The bill applies internet regulations only to companies receiving state support (13 companies, each one serving rural areas). With the exception of CenturyLink, these are very small telecommunications companies, and the smallest had 64 customers. It is a puzzle why the state would add regulations and compliance costs to rural ISPs at a time when the FCC and most states are doing everything possible to help deploy broadband in rural areas.

This is not a plea to “do nothing” in Colorado regarding broadband. The FCC’s Broadband Deployment Advisory Committee has several recommendations for states and localities to improve broadband deployment.

Further, the FCC and some states are considering making it easier for private property owners to install wireless antennas without local regulation and fees, much like how satellite dishes are installed.

Finally, the legislature could also urge flexibility from the FCC regarding the federal high-cost fund, which disburses about $60 million annually to carriers in Colorado. My preliminary estimates using FCC data suggest that, under a new voucher program, every rural household in Colorado could receive $15 to $20 per month to reduce their monthly broadband bill.

Testimony on the Mercatus website here.

May 30, 2019

An Epic Moral Panic Over Social Media

[This essay originally appeared on the AIER blog on May 28, 2019.]

In a hotly-worded USA Today op-ed last week, Senator Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) railed against social media sites Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. He argued that, “social media wastes our time and resources,” and is “a field of little productive value” that have only “given us an addiction economy.” Sen. Hawley refers to these sites as “parasites” and blames them for a litany of social problems (including an unproven link to increased suicide), leading him to declare that, “we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared.”

As far as moral panics go, Sen. Hawley’s will go down as one for the ages. Politicians have always castigated new technologies, media platforms, and content for supposedly corrupting the youth of their generation. But Sen. Hawley’s inflammatory rhetoric and proposals are something we haven’t seen in quite some time.

He sounds like those fire-breathing politicians and pundits of the past century who vociferously protested everything from comic books to cable television, the waltz to the Walkman, and rock-and-roll to rap music. In order to save the youth of America, many past critics said, we must destroy the media or media platforms they are supposedly addicted to. That is exactly what Sen. Hawley would have us do to today’s leading media platforms because, in his opinion, they “do our country more harm than good.”

We have to hope that Sen. Hawley is no more successful than past critics and politicians who wanted to take these choices away from the public. Paternalistic politicians should not be dictating content choices for the rest of us or destroying technologies and platforms that millions of people benefit from.

Addiction Panics: We’ve Been Here Before

Ironically, Sen. Hawley isn’t even right about what the youth of America are apparently obsessed with. Most kids view Facebook and Twitter as places where old people hang out. My teenage kids laugh when I ask them about those sites. Pew Research polling finds that many younger users are increasingly deleting Facebook (if they used it at all) or flocking to other platforms, such as Snapchat or YouTube.

But shouldn’t we be concerned with kids overusing social media more generally? Yes, of course we should—but that’s no reason to call for their outright elimination, as Sen. Hawley recommends. Such rhetoric is particularly concerning at a time when critics are proposing a “break up” of tech companies. Sen. Hawley sits on the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights. It is likely he and others will employ these arguments to fan the flames of regulatory intervention or antitrust action against at least Facebook.

Forcing social media sites to “disappear” or be broken up is one of the worst ways to deal with these concerns. It is always wise to mentor our youth and teach them how to achieve a balanced media diet. Many youths—and many adults—are probably overusing certain technologies (smartphones, in particular) and over-consuming some types of media. For those truly suffering from addiction, it is worth considering targeted strategies to address that problem. However, that is not what antitrust law is meant to address.

Moreover, concerns about addiction and distraction have popped up repeatedly during past moral panics and we should take such claims with a big grain of salt. Sociologist Frank Furedi has documented how, “inattention has served as a sublimated focus for apprehensions about moral authority” going back to at least the early 1700s. With each new form of media or means of communication, the older generation taps into the same “kids-these-days!” fears about how the younger generation has apparently lost the ability to concentrate or reason effectively.

For example, in the past century, critics said the same thing about radio and television broadcasting, comparing them to tobacco in terms of addiction and suggesting that media companies were “manipulating” us into listening or watching. Rock-and-roll and rap music got the same treatment, and similar panics about video games are still with us today.

Strangely, many elites, politicians, and parents forget that they, too, were once kids and that their generation was probably also considered hopelessly lost in the “vast wasteland” of whatever the popular technology or content of the day was. The Pessimists Archive podcast has documented dozens of examples of this reoccurring phenomenon. Each generation makes it through the panic du jour, only to turn around and start lambasting newer media or technologies that they worry might be rotting their kids to the core. While these panics come and go, the real danger is that they sometimes result in concrete policy actions that censor content or eliminate choices that the public enjoys. Such regulatory actions can also discourage the emergence of new choices.

Missed Opportunity, or Marvelous Achievement?

Sen. Hawley makes another audacious assertion in his essay when he suggests that social media has not provided any real benefit to American workers or consumers. He says the rise of the Digital Economy has “encouraged a generation of our brightest engineers to enter a field of little productive value,” which he regards as “an opportunity missed for the nation.”

This is an astonishing statement, made more troubling by Hawley’s claim that all these digital innovators could have done far more good by choosing other professions. “What marvels might these bright minds have produced,” Hawley asks, “had they been oriented toward the common good?”

Why is it that Sen. Hawley gets to decide which professions are in “the common good”? This logic is insulting to all those who make a living in these sectors, but there is a deeper hubris in Sen. Hawley’s argument that social media does not serve “the common good.” Had some benevolent philosopher kings in Washington stopped the digital economy from developing over the past quarter century, would all those tech workers really have chosen more noble-minded and worthwhile professions? Could he or others in Congress really have had the foresight to steer us in a better direction?

In reality, U.S. tech companies produce high-quality jobs and affordable, collaborative communications platforms that are popular across the globe. In response to Sen. Hawley’s screed, the Internet Association, which represents America’s leading digital technology companies, noted that, in Sen. Hawley’s home state of Missouri alone, the Internet supports 63,000 jobs at 3,400 companies and contributed $17 billion in GDP to the state’s economy. Presumably, Sen. Hawley would not want to see those benefits “disappear” along with the social media sites that helped give rise to them.

But the Internet and social media have an equally profound impact on the entire U.S. economy, adding over 9,000 jobs and nearly 570 businesses to each metropolitan statistical area. The Digital Economy is a great American success story that is the envy of the world, not something to be lamented and disparaged as Sen. Hawley has.

For someone who believes that Facebook is a “drug” and a “parasite,” it is curious how active Sen. Hawley is on Facebook, as well as on Twitter. If he really believes that “we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared,” then he should lead by example and get off the sites. But that is a decision he will have to make for himself. He should not, however, make it for the rest of us.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower