Adam Thierer's Blog, page 22

November 6, 2018

Some data on wireless networks and cancer rates

By Brent Skorup and Trace Mitchell

An important benefit of 5G cellular technology is more bandwidth and more reliable wireless services. This means carriers can offer more niche services, like smart glasses for the blind and remote assistance for autonomous vehicles. A Vox article last week explored an issue familiar to technology experts: will millions of new 5G transmitters and devices increase cancer risk? It’s an important question but, in short, we’re not losing sleep over it.

5G differs from previous generations of cellular technology in that “densification” is important–putting smaller transmitters throughout neighborhoods. This densification process means that cities must regularly approve operators’ plans to upgrade infrastructure and install devices on public rights-of-way. However, some homeowners and activists are resisting 5G deployment because they fear more transmitters will lead to more radiation and cancer. (Under federal law, the FCC has safety requirements for emitters like cell towers and 5G. Therefore, state and local regulators are not allowed to make permitting decisions based on what they or their constituents believe are the effects of wireless emissions.)

We aren’t public health experts; however, we are technology researchers and decided to explore the telecom data to see if there is a relationship. If radio transmissions increase cancer, we should expect to see a correlation between the number of cellular transmitters and cancer rates. Presumably there is a cumulative effect: the more cellular radiation people are exposed to, the higher the cancer rates.

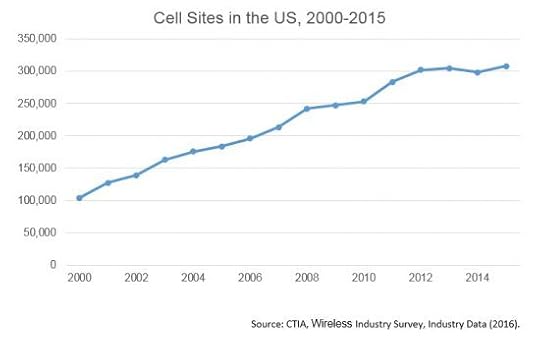

From what we can tell, there is no link between cellular systems and cancer. Despite a huge increase in the number of transmitters in the US since 2000, the nervous system cancer rate hasn’t budged. In the US the number of wireless transmitters have increased massively–300%–in 15 years. (This is on the conservative side–there are tens of millions of WiFi devices that are also transmitting but are not counted here.)

But the US cancer rate is the dog that didn’t bark. In that same span of time, the type of cancers you would expect if cellphones pose a cancer risk–brain and nervous systems–have remained flat. If anything, as the NIH has said, these cancer rates have fallen slightly.

It’s a seeming paradox: In the US there was an introduction of 300,000 fairly powerful cell transmitters and hundreds of millions of (lower-power) devices that transmit signals through the air twenty four hours per day, seven days per week, every day of the year, yet these transmissions have no apparent effect on cancer rates.

The fear of 4G and 5G transmitters is due to a common misunderstanding about radiation. Significant exposure to ionizing radiation, the kind put off by X-rays and ultraviolet light, does have the potential to cause cancer. However, as the Vox article and other experts point out, cellular systems and devices don’t put off ionizing radiation. Tech devices emit a form of non-ionizing radiation, the type of radiation you receive from the visible light that bounces off, say, a book you hold in your hand. Unlike ionizing radiation, this non-ionizing radiation is too weak to alter DNA.

More research would be welcomed. The Vox article notes that much of the wireless system-cancer research is low-quality. Further, while wireless systems don’t seem to cause DNA damage there may be other effects on cells. A very focused wireless transmission from inches away can excite molecules and raise the temperature–this is how a microwave oven works–so it might be a good idea to keep your cellphone on your desk, not in your pocket, when possible. In the end, however, resist the technopanic–we don’t see much to be concerned about.

November 1, 2018

Don’t game EPA regulations to help DSRC car technology

By Brent Skorup and Michael Kotrous

In 1999, the FCC completed one of its last spectrum “beauty contests.” A sizable segment of spectrum was set aside for free for the US Department of Transportation (DOT) and DOT-selected device companies to develop DSRC, a communications standard for wireless automotive communications, like vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I). The government’s grand plans for DSRC never materialized and in the intervening 20 years, new tech—like lidar, radar, and cellular systems—advanced and now does most of what regulators planned for DSRC.

Too often, however, government technology plans linger, kept alive by interest groups that rely on the new regulatory privilege, even when the market moves on. At the eleventh hour of the Obama administration, NHTSA proposed mandating DSRC devices in all new vehicles, an unprecedented move that Brent and other free-market groups opposed in public interest comment filings. As Brent wrote last year,

In the fast-moving connected car marketplace, there is no reason to force products with reliability problems [like DSRC] on consumers. Any government-designed technology that is “so good it must be mandated” warrants extreme skepticism….

Further,

Rather than compel automakers to add costly DSRC systems to cars, NHTSA should consider a certification or emblem system for vehicle-to-vehicle safety technologies, similar to its five-star crash safety ratings. Light-touch regulatory treatment would empower consumer choice and allow time for connected car innovations to develop.

Fortunately, the Trump administration put the brakes on the mandate, which would have added cost and complexity to cars for uncertain and unlikely benefits.

However, some regulators and companies are trying to revive the DSRC device industry while NHTSA’s proposed DSRC mandate is on life support. Marc Scribner at CEI uncovered a sneaky attempt to create DSRC technology sales via an EPA proceeding. The stalking horse DSRC boosters have chosen is the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations—specifically the EPA’s off-cycle program. EPA and NHTSA jointly manage these regulations. That program rewards manufacturers who adopt new technologies that reduce a vehicle’s emissions in ways not captured by conventional measures like highway fuel economy.

Under the proposed rules, auto makers that install V2V or V2I capabilities can receive credit for having reduced emissions. The EPA proposal doesn’t say “DSRC” but it singles out only one technology standard that would be favored in this scheme: a standard underlying DSRC.

This proposal comes as a bit of surprise for those who have followed auto technology; we’re aware of no studies showing DSRC improves emissions. (DSRC’s primary use-case today is collision warnings to the driver.) But the EPA proposes a helpful end-around that problem: simply waiving the requirement that manufacturers provide data showing a reduction in harmful emissions. Instead of requiring emissions data, the EPA proposes a much lower bar, that auto makers show that these devices merely “have some connection to overall environmental benefits.” Unless the agency applies credits in a tech-neutral way and requires more rigor in the final rules, which is highly unlikely, this looks like a backdoor subsidy to DSRC via gaming of emission reduction regulations.

Hopefully EPA regulators will discover the ruse and drop the proposal. It was a pleasant surprise last week when a DOT spokesman committed that the agency favored a tech-neutral approach for this “talking car” band. But after 20 years, this 75 MHz of spectrum gifted to DSRC device makers should be repurposed by the FCC for flexible-use. Fortunately, the FCC has started thinking about alternative uses for the DSRC spectrum. In 2015 Commissioners O’Rielly and Rosenworcel said the agency should consider flexible-use alternatives to this DSRC-only band.

The FCC would be wise to follow through and push even farther. Until the gifted spectrum that powers DSRC is reallocated to flexible use, interest groups will continue to pull any regulatory lever it has to subsidize or mandate adoption of talking-car technology. If DSRC is the best V2V technology available, device makers should win market share by convincing auto companies, not by convincing regulators.

October 25, 2018

Event Video: My Talk at Reboot 2018 about “Innovation Under Threat”

Last month, it was my great honor to be invited to be a keynote speaker at Lincoln Network’s Reboot 2018 “Innovation Under Threat” conference. Zach Graves interviewed me for 30 minutes about a wide range of topics, including: innovation arbitrage, evasive entrepreneurialism, technopanics, the pacing problem, permissionless innovation, technological civil disobedience, existential risk, soft law and more. They’ve now posted the full event video and you can watch it down below.

October 17, 2018

Should The New NPR Poll On Rural America Make You Reconsider Your View of Rural Broadband Development?

National Public Radio, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health just published a new report on “Life in Rural America.” This survey of 1,300 adults living in the rural United States has a lot to say about health issues, population change, the strengths and challenges for rural communities, as well as discrimination and drug use. But I wanted to highlight two questions related to rural broadband development that might make you update your beliefs about massive rural investment.

To begin with, it should be noted that this survey didn’t feature rural broadband development that much, but the topic did arise in the context of improving rural economies. Specifically, question 44 asked, “Recently, a number of leadership groups have recommended different approaches for improving the economy of communities like yours. For each of the following, please tell me how helpful you think this approach would be for improving the economy of your local community…[insert item]. Do you think this would be very helpful, somewhat helpful, not too helpful, or not at all helpful?”

Here is a breakdown of how people responded, saying that these changes would be very helpful:

Creating better long-term job opportunities 64%

Improving the quality of local public schools 61%

Improving access to health care 55%

Improving access to advanced job training or skills development 51%

Improving local infrastructure like roads, bridges, and public buildings 48%

Improving the use of advanced technology in local industry and farming 44%

Improving access to small business loans and investments 44%

Improving access to high-speed internet 43%

Notice where improving access to Internet ranks. It is at the bottom. And improving the use of advanced technology in local industry and farming doesn’t do much better. What ranks higher than both of these, however, is improving access to advanced job training or skills development. As I have been saying for some time, digital literacy efforts are seriously underrated.

The poll also asked an open ended question in Question 2, what is the biggest problem facing your community, and again, access to high speed Internet was near the bottom of the list. In fact, racism, access to good doctors and hospitals, access to public transportation, law enforcement, and access to grocery stores all ranked as more pressing concerns. What topped the list were opioid addiction and jobs.

Rural broadband development should be pursued. But this polling suggests that some might want to revise their estimates about a big economic bump from rural broadband.

October 10, 2018

In Defense of Techno-optimism

Many are understandably pessimistic about platforms and technology. This year has been a tough one, from Cambridge Analytica and Russian trolls to the implementation of GDPR and data breaches galore.

Those who think about the world, about the problems that we see every day, and about their own place in it, will quickly realize the immense frailty of humankind. Fear and worry makes sense. We are flawed, each one of us. And technology only seems to exacerbate those problems.

But life is getting better. Poverty continues nose-diving; adult literacy is at an all-time high; people around the world are living longer, living in democracies, and are better educated than at any other time in history. Meanwhile, the digital revolution has resulted in a glut of informational abundance, helping to correct the informational asymmetries that have long plagued humankind. The problem we now face is not how to address informational constraints, but how to provide the means for people to sort through and make sense of this abundant trove of data. These macro trends don’t make headlines. Psychologists know that people love to read negative articles. Our brains are wired for pessimism.

In the shadow of a year of bad news, it helpful to remember that Facebook and Google and Reddit and Twitter also support humane conversations. Most people aren’t going online to talk about politics and if you are, then you are rare. These sites are places where families and friends can connect. They offer a space of solace – like when chronic pain sufferers find others on Facebook, or when widows vent, rage, laugh and cry without judgement through the Hot Young Widows Club. Let’s also not forget that Reddit, while sometimes a place of rage and spite, is also where a weight lifter with cerebral palsy can become a hero and where those with addiction can find healing. And in the hardest to reach places in Canada, in Iqaluit, people say that “Amazon Prime has done more toward elevating the standard of living of my family than any territorial or federal program. Full stop. Period”

Three-fourths of Americans say major technology companies’ products and services have been more good than bad for them personally. But when it comes to the whole of society, they are more skeptical about technology bringing benefits. Here is how I read that disparity: Most of us think that we have benefited from technology, but we worry about where it is taking the human collective. That is an understandable worry, but one that shouldn’t hobble us to inaction.

Nor is technology making us stupid. Indeed, quite the opposite is happening. Technology use in those aged 50 and above seems to have caused them to be cognitively younger than their parents to the tune of 4 to 8 years. While the use of Google does seem to reduce our ability to recall information, studies find that it has boosted other kinds of memory, like retrieving information. Why remember a fact when you can remember where it is located? Concerned how audiobooks might be affecting people, Beth Rogowsky, an associate professor of education, compared them to physical reading and was surprised to find “no significant differences in comprehension between reading, listening, or reading and listening simultaneously.” Cyberbullying and excessive use might make parents worry, but NIH supported work found that “Heavy use of the Internet and video gaming may be more a symptom of mental health problems than a cause. Moderate use of the Internet, especially for acquiring information, is most supportive of healthy development.” Don’t worry. The kids are going to be alright.

And yes, there is a lot we still need to fix. There is cruelty, racism, sexism, and poverty of all kinds embedded in our technological systems. But the best way to handle these issues is through the application of human ingenuity. Human ingenuity begets technology in all of its varieties.

When Scott Alexander over at Star Slate Codex recently looked at 52 startups being groomed by startup incubator Y Combinator, he rightly pointed out that many of them were working for the betterment of all:

Thirteen of them had an altruistic or international development focus, including Neema, an app to help poor people without access to banks gain financial services; Kangpe, online health services for people in Africa without access to doctors; Credy, a peer-to-peer lending service in India; Clear Genetics, an automated genetic counseling tool for at-risk parents; and Dost Education, helping to teach literacy skills in India via a $1/month course.

Twelve of them seemed like really exciting cutting-edge technology, including CBAS, which describes itself as “human bionics plug-and-play”; Solugen, which has a way to manufacture hydrogen peroxide from plant sugars; AON3D, which makes 3D printers for industrial uses; Indee, a new genetic engineering system; Alem Health, applying AI to radiology, and of course the obligatory drone delivery startup.

Eighteen of them seemed like boring meat-and-potatoes companies aimed at businesses that need enterprise data solution software application package analytics targeting management something something something “the cloud”.

As for the other companies, they were the kind of niche products that Silicon Valley has come to be criticized for supporting. Perhaps the Valley deserves some criticism, but perhaps it deserves more credit than it’s been receiving as-of-late.

Contemporary tech criticism displays a kind of anti-nostalgia. Instead of being reverent for the past, anxiety for the future abounds. In these visions, the future is imagined as a strange, foreign land, beset with problems. And yet, to quote that old adage, tomorrow is the visitor that is always coming but never arrives. The future never arrives because we are assembling it today. We need to work diligently together to piece together a better world. But if we constantly live in fear of what comes next, that future won’t be built. Optimism needn’t be pollyannaish. It only needs to be hopeful of a better world.

October 1, 2018

Should the US Adopt the GDPR?

Last week, I had the honor of being a panelist at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation’s event on the future of privacy regulation. The debate question was simple enough: Should the US copy the EU’s new privacy law?

When we started planning the event, California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) wasn’t a done deal. But now that it has passed and presents a deadline of 2020 for implementation, the terms of the privacy conversation have changed. Next year, 2019, Congress will have the opportunity to pass a law that could supersede the CCPA and some are looking to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) for guidance. Here are some reasons for not taking that path.

GDPR imposes three kinds of costs on firms. First, the regulation forces firms to retool data processes to realign with the new demands. This is generally one time fixed cost that raises the cost of all information using entities. Second, the regime adds risk compliance costs, causing companies to staff up to ensure compliance. Finally, the law will change the dynamics of the industry, as companies adapt to the new requirements.

Right now, the retooling costs and the risk compliance costs are going hand in hand, so it is difficult to suss out the costs of each. Still, they are substantial. A McDermott-Ponemon survey on GDPR preparedness found that almost two-thirds of all companies say the regulation will “significantly change” their informational workflows. For the just over 50 percent of companies expecting to be ready for the changes, the average budget for getting to compliance tops $13 million, by this estimate. Among all the new requirements, this survey found that companies were struggling with the data-breach notification the most. The inability to comply with the notification requirement was cited by 68 percent of companies as posing the greatest risk because of the size of levied fines.

The International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) estimated the regulation will cost Fortune 500 companies around $7.8 billion to get up to speed with the law. And these won’t be one time costs since, “Global 500 companies will be hiring on average five full-time privacy employees and filling five other roles with staff members handling compliance rules.” A PwC survey on the rule change found that 88% of companies surveyed spent more than $1 million on GDPR preparations, and 40% more than $10 million.

It might take some time to truly understand the impact of GDPR, but the law will surely change the dynamics of countless industries. For example, when the EU adopted the e-Privacy Directive in 2002, Goldfarb and Tucker found that advertising became far less effective. The impact seems to have reverberated throughout the ecosystem as venture capital investment in online news, online advertising, and cloud computing dropped by between 58 to 75 percent. Information restrictions shift consumer choices. In Chile, for example, credit bureaus were forced to stop reporting defaults in 2012, which was found to reduce the costs for most of the poorer defaulters, but raised the costs for non-defaulters. Overall the law lead to a 3.5 percent decrease in lending and reduced aggregate welfare.

As the Chilean example suggests, some might benefit from a GDPR-like privacy regime. But as Daniel Castro, my co-panelist pointed out, strong privacy laws haven’t done much to sway public opinion. As he wrote with Alan McQuinn,

The biannual Eurobarometer survey, which interviews 100 individuals from each EU country on a variety of topics, has been tracking European trust in the Internet since 2009. Interestingly, European trust in the Internet remained flat from 2009 through 2017, despite the European Union strengthening its ePrivacy regulations in 2009 (implementation of which occurred over the subsequent few years) and significantly changing its privacy rules, such as the court decision that established the right to be forgotten in 2014. Similarly, European trust in social networks, which the Eurobarometer started measuring in 2014, has also remained flat, albeit low

In other words, it doesn’t seem as though strong regulations have done anything to make people feel as though they are getting a better deal with Internet companies.

One of my top concerns with the GDPR that wasn’t really discussed relates to the consent requirement in the law. Now, people must affirmatively say that data processors can use their data. As I explained at the American Action Forum,

Affirmative consent is also known as an opt-in privacy regime. Opt-in is frequently described as giving consumers more privacy protection, but opt-out regimes give an individual the same option to exit data processing without the added burdens. Indeed, most of the large companies already provide a method of opting out of certain data processing and collection. Setting the default by regulation simply biases consumer choices in a particular direction.

Overall, I think I think there was general agreement among the panelists that the US should not adopt the GDPR. But, both Amie Stepanovich of Access Now and Justin Brookman of Consumer’s Union were generally in favor of implementing a couple of the fundamental elements of the GDPR, assuming they were adopted to the US legal system. Indeed, Access Now released a paper on exactly this topic.

The big question is whether the GDPR or something similar is a set of optimal rules. For countless reasons, I’m skeptical they will really improve consumer experience without imposing substantial costs.

For more on this topic, check out:

Explaining The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation by Will Rinehart & Allison Edwards

Why Stronger Privacy Regulations Do Not Spur Increased Internet Use by Alan McQuinn and Daniel Castro

September 28, 2018

Mercatus essays on innovation, entrepreneurialism & technological governance

In recent months, my colleagues and I at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University have published a flurry of essays about the importance of innovation, entrepreneurialism, and “moonshots,” as well as the future of technological governance more generally. A flood of additional material is coming, but I figured I’d pause for a moment to track our progress so far. Much of this work is leading up to my next on the freedom to innovate, which I am finishing up currently.

Adam Thierer, “Deep Technologies & Moonshots: Should We Dare to Dream?” Medium, September 7, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “The Right to Pursue Happiness, Earn a Living, and Innovate,” The Bridge, September 20, 2018.

Adam Thierer & Trace Mitchell, “A Non-Partisan Way to Help Workers and Consumers,” The Bridge, September 25, 2018.

Adam Thierer and Trace Mitchell, “The Many Forms of Entrepreneurialism,” The Bridge, August 30, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “Is It “Techno-Chauvinist” & “Anti-Humanist” to Believe in the Transformative Potential of Technology?” Medium, September 18, 2018.

“Evasive Entrepreneurs and Permissionless Innovation: An Interview with Adam Thierer,” The Bridge, September 11, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “Making the World Safe for More Moonshots,” The Bridge, February 5, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “Evasive Entrepreneurialism and Technological Civil Disobedience: Basic Definitions,” The Bridge, July 20, 2018,

Adam Thierer, “The Pacing Problem and the Future of Technology Regulation,” The Bridge, August 8, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “The Pacing Problem, the Collingridge Dilemma & Technological Determinism,” Technology Liberation Front, August 16, 2018.

Andrea O’Sullivan & Adam Thierer, “3D Printers, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Tech Regulation,” The Bridge, August 1, 2018.

Jennifer Huddleston Skees, “,” The Bridge, September 13, 2018.

Jennifer Skees, “Do You Need a License to Innovate?”, The Bridge, June 29, 2018.

Adam Thierer and Jennifer Skees, “Lemonade Stands and Permits,” The Bridge, August 20, 2018.

Jennifer Huddleston Skees and Adam Thierer, “Pennsylvania’s Innovative Approach to Regulating Innovation,” The Bridge, September 5, 2018.

Jennifer Huddleston Skees & Trace Mitchell, “Transportation 3.0”, The Bridge, August 29, 2018.

Jennifer Skees & Trace Mitchell, “Will The Electric Scooter Movement Lose Its Charge?” The Bridge, July 18, 2018.

Adam Thierer & Trace Mitchell, “The Many Flavors of Food Entrepreneurialism,” The Bridge, September 26, 2018.

Jennifer Skees, “Should You Be Able to Fix Your Own iPhone,” Plain Text, June 18, 2018, https://readplaintext.com/should-you-be-able-to-fix-your-own-iphone-b4157e6cd23

Some older essays on related topics

Adam Thierer, Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom , 2nd ed. (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2016).

Adam Thierer, “Wendell Wallach on the Challenge of Engineering Better Technology Ethics,” Technology Liberation Front, April 20, 2016.

Adam Thierer, “Are “Permissionless Innovation” and “Responsible Innovation” Compatible?” July 12, 2017.

Adam Thierer, “Does “Permissionless Innovation” Even Mean Anything?” Technology Liberation Front, May 18, 2017.

Adam Thierer, “What Does It Mean to “Have a Conversation” about a New Technology?,” Technology Liberation Front, May 23, 2013.

Adam Thierer, “On the Line between Technology Ethics vs. Technology Policy,” August 23, 2013.

Adam Thierer, “Muddling Through: How We Learn to Cope with Technological Change” Medium, June 30, 2014.

Adam Thierer, “Book Review: Calestous Juma’s “Innovation and Its Enemies” Technology Liberation Front, July 29, 2016.

Adam Thierer, “Embracing a Culture of Permissionless Innovation,” Cato Online Forum, November 17, 2014.

Adam Thierer, “Defining ‘Technology’” Technology Liberation Front, originally published April 29, 2014, last updated July 2017.

Ryan Hagemann, Jennifer Skees & Adam Thierer, “Soft Law for Hard Problems: The Governance of Emerging Technologies in an Uncertain Future,” February 5, 2018, (Forthcoming – Colorado Technology Law Journal).

September 25, 2018

Thoughts on FTC Economic Liberty Task Force Report & Occupational Licensing Reform

Over at the Mercatus Center Bridge blog, Trace Mitchell and I just posted an essay entitled, “A Non-Partisan Way to Help Workers and Consumers,” which discusses the new Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Economic Liberty Task Force report on occupational licensing.

We applaud the FTC’s calls for greater occupational licensing uniformity and portability, but regret the missed opportunity to address root problem of excessive licensing more generally. But while FTC is right to push for greater occupational licensing uniformity and portability, policymakers need to confront the sheer absurdity of licensing so many jobs that pose zero risk to public health & safety. Licensing has become completely detached from risk realities and actual public needs.

As the FTC notes, excessive licensing limits employment opportunities, worker mobility, and competition while also “resulting in higher prices, reduced quality, and less convenience for consumers.” These are unambiguous facts that are widely accepted by experts of all stripes. Both the Obama and Trump Administrations, for example, have been completely in league on the need for comprehensive licensing reforms.

Trace and I argue that we need serious occupational reforms built on the idea of the “right to earn a living” that must pass this test: “All occupational regulations shall be limited to those demonstrably necessary and carefully tailored to fulfill legitimate public health, safety, or welfare objectives.” Also, all licensing authorities should be put on the clock and be required, within one year, to reassess the wisdom of all existing licenses to ensure they meet that test. If not, they are repealed or reformed.

In recent testimony in Texas, our Mercatus Center colleague Matthew Mitchell has also discussed other reform options, including the “Occupational Board Reform Act,” which recently passed in Nebraska. The goal of the law is to “protect the fundamental right of an individual to pursue a lawful occupation;.” They key provision of the Act demands that state actors:

use the least restrictive regulation which is necessary to protect consumers from undue risk of present, significant, and substantiated harms that clearly threaten or endanger the health, safety, or welfare of the public when competition alone is not sufficient and which is consistent with the public interest;

That’s an excellent approach to reform and when combined with the Right to Earn a Living Act, policymakers can begin to reverse the protectionist, anti-competitive licensing schemes that encumber entrepreneurs and workers across the land.

In forthcoming work, I hope to more fully develop the connection between the right to earn a living, the need for comprehensive licensing reform, and the freedom to innovate more generally. In the meantime, hop over to The Bridge to read our new essay on how the FTC report helps advance this cause..

September 18, 2018

Is It “Techno-Chauvinist” & “Anti-Humanist” to Believe in the Transformative Potential of Technology?

I’ve always been perplexed by tech critiques who seek to pit “humanist” values against technology or technological processes, or that even suggest a bright demarcation exists between these things. Properly understood, “technology” and technological innovation are simply extensions of our humanity and represent efforts to continuously improve the human condition. In that sense, humanism and technology are compliments, not opposites.

I started thinking about this again after reading a recent article by Christopher Mims of The Wall Street Journal, which introduced me to the term “techno-chauvinism.” Techno-chauvinism is a new term that some social critics are using to identify when technologies or innovators are apparently not behaving in a “humanist” fashion. Mims attributes the term techno-chauvinism to Meredith Broussard of New York University, who defines it as “the idea that technology is always the highest and best solution, and is superior to the people-based solution.” [Italics added.] Later on Twitter, Mims defined and critiqued techno-chauvinism as “the belief that the best solution to any problem is technology, not changing our culture, habits or mindset.”

Everything Old is New Again

There are other terms critics have used to describe the same notion, including: “techno-fundamentalism” (Siva Vaidhyanathan), “cyber-utopianism,” and “technological solutionism” (Evgeny Morozov). In a sense, all these terms are really just variants of what scholars in the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS) have long referred to as “technological determinism.”

As I noted in a recent essay about determinism, the traditional “hard” variant of technological determinism refers to the notion that technology almost has a mind of its own and that it will plow forward without much resistance from society or governments. Critics argue that determinist thinking denies or ignores the importance of the human element in moving history forward, or what Broussard would refer to as “people-based solutions.”

The first problem with this thinking is there are no bright lines in these debates and many “softer” variants of determinism exist. The same problem is at work when we turn to discussions about both “humanism” and “technology.” Things get definitionally murky quite quickly, and everyone seemingly has a preferred conception of these terms to fit their own ideological dispositions. “Humanism is a rather vague and contested term with a convoluted history,” observes tech philosopher Michael Sacasas. And here’s an essay that I have updated many times over the years to catalog the dozens of different definitions of “technology” I have unearthed in my ongoing research.

Thus, when we hear “humanist” critiques of “technology,” I can’t help but think that many of them begin with an unclear explanation of what both those terms mean and how they are related. Here’s how I think about them.

“Technology” is not some magical force or shiny device that appeared out of thin air. All technology is the product of human design. The most straightforward definition of “technology” is simply the application of knowledge to a task. When critics claim that innovators or their defenders are “chauvinists” who think that technological solutions are “superior to the people-based solution,” they are creating a nonsensical dichotomy because technological solutions are the same thing as “people-based solution.” People create technologies to solve problems. We can imagine the first person who struck two stones together to make a spark and light a fire, or the first humans who fashioned knives or bows and arrows to hunt game. Were they not being “humanist” by pursuing a better way to feed themselves and others? Personally, I cannot think of anything more “humanist” than creating or using whatever tools one can to put the next meal on the table! Eventually, most tools and processes like these become so ordinary that we no longer even consider them “technology” at all. They just become part of the fabric of our lives and we come to take them for granted.

What some critics mean by “humanism” is also confusing for reasons that were nicely identified by Andrew McAfee in his 2015 Financial Times essay, “Who are the humanists, and why do they dislike technology so much?” McAfee pointed out that some “humanist” critiques of technological innovation are relatively banal to the extent they are simply reminding us that all people are important, or that all technological process involve trade-offs that we should be aware of.

Of course these things are true, McAfee noted. But it is also true that technological advancement solves far more problems than it creates by helping to reduce hunger and disease, travel further, communicate more widely, gain leisure time, and so on. Moreover, there are trade-offs associated with all human actions. Limiting ongoing innovations and improvements that could better the human condition gives rise to equally significant trade-offs. In any event, to the extent “humanism” can be reduced to UP WITH PEOPLE! and TRADE-OFFS MATTER!, I think all of us would consider ourselves to be “humanists.”

The Vision of the Anointed

But there’s a third conception of “humanism” McAfee identified that he regarded as far more problematic. I will label it the “Vision of the Anointed,” to borrow a phrase Thomas Sowell used in his book about the way some elites allow rhetorical flourishes and good intentions to trump actual real-world evidence and results. McAfee summarized this humanist version of the Vision of the Anointed as follows: “Because I am for the people I should be free from having to support my contentions with anything more than rhetoric.” Or, more simply: “You can trust what I say, because I am on the side of people instead of the cold, hard machines.”

That sort of vision is at work in a great deal of STS scholarship, and has been for a long, long time. Indeed, modern conceptions of “humanism” and critiques of “techno-chauvinism” or “solutionism” are just restatements of the lamentations of countless previous media critics or technology critics from the past, including Jacques Ellul, Lewis Mumford, Neil Postman, Langdon Winner, Christopher Lasch, and many others. Much criticism of this sort ends up suggesting — either directly or implicitly — that technological innovation is anti-human or “de-humanizing” in some fashion and should, therefore, be rejected, reversed, or at least slowed down considerably.

For example, in Lasch’s 1991 book, The True and Only Heaven, the social critic lambasted what he called “progressive optimism” for its supposed “denial of the natural limits on human power and freedom.” Lasch desired a “populism for the twenty-first century” that “would find much of its moral inspiration in the popular radicalism of the past and most generally in the wide-ranging critique of progress, enlightenment, and unlimited ambition.”

This gets to the real irony associated with the Humanistic Vision of the Anointed: It doesn’t place a lot of faith in humans! In this highly pessimistic and often quite elitist worldview, the masses seemingly do not understand what is in their own best interests, and the material gains of modern civilization are, at once, both a fiction to be scoffed at and a reality to be scorned as counterproductive or “anti-human.” What is the alternative arrangement for society that is set forth by those subscribing to the Vision of the Anointed? As Lasch suggests, it comes down to acceptance of limits. In closing his book, Lasch called for the return of a humanistic “state of heart and mind” that “asserts the goodness of life in the face of its limits.” In other words, we should be happy with what we’ve got because progress ain’t so great.

Pastoral Myths & the “Good ‘Ol Days”

This also explains the enduring power of “pastoral myths” in the work of such critics. If you spend enough time reading through works of technology and media criticism, you often find allusions made to some supposedly better time — the proverbial “good ‘ol days” — when life was supposed simplier or better in some way. Other times, it is just implied that life in the present isn’t as good as it was in the past.

The problem is that those good ‘ol days weren’t so great. “Demonizing innovation is often associated with campaigns to romanticize past products and practices,” Calestous Juma noted in his 2016 book, Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technologies. “Opponents of innovation hark back to traditions as if traditions themselves were not inventions at some point in the past.” That was especially the case in battles over new farming methods and technologies, when opponents of change were frequently “championing a moral cause to preserve a way of life,” as Juma discusses in several chapters of his book. New products or methods of production were repeatedly but wrongly characterized as dangerous or anti-human simply because they were not supposedly “natural” or “traditional” enough in character.

Of course, if all farming and other work was to remain frozen in some past “natural” state, we’d all still be hunters and gathers struggling to find the next meal to put in our bellies. Or, if we were all still on the farms of the “good ‘ol days,” then we’d still be stuck using an ox and plow in the name of preserving the “traditional” ways of doing things.

Humanity has made amazing strides—including being able to feed more people more easily and cheaply than ever before—precisely because we broke with those old, “natural” traditions. Alas, many vested interests, and even quite a few academics, still employ these same pastoral appeals and myths to oppose new forms of technological change. The case studies in Juma’s book powerfully illustrate why that dynamic continues to be a driving force in innovation policy debates and how it delays the diffusion of many important new life-enriching goods and services.

Trial and Error

When the opponents of change rest their case on pastoral myths and nostalgic arguments about the good ‘ol days, we should remind them that those days were, in reality, eras of abject misery. Widespread poverty, mass hunger, poor hygiene, short lifespans, and so on were the norm. What lifted humanity up and improved our lot as a species is that we learned how to apply knowledge to tasks in a better way through incessant trial and error experimentation. In other words, we flourished by innovating. And the results of our innovative activities were called technologies.

In this sense, humanism and technology have gone hand in hand throughout history. Steven Pinker put it best in his new book, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress: “Progress consists of deploying knowledge to allow all of humankind to flourish in the same way that each of us seeks to flourish. The goal of maximizing human flourishing–life, happiness, freedom, knowledge, love, richness of experiences–may be called humanism.”

Our technologies are simply extensions of our knowledge and represent profoundly humanist efforts to improve our lives and the lives of others around us. “We will never have a perfect world, and it would be dangerous to seek one,” Pinker notes. “But there is no limit to the betterments we can attain if we continue to apply knowledge to enhance human flourishing,” he rightly concludes.

The Right Balance

Of course, as Pinker hints, we can go too far sometimes or place too much faith in our tools. Pursuing perfection through technological betterment can end in folly, or worse. In my previous essay, “Deep Technologies & Moonshots: Should We Dare to Dream,” I noted that over-exuberant tech boosters are sometimes guilty of the same rhetorical excesses and inflated claims that some humanist critics practice. Some tech evangelists go too far in suggesting that technological innovation can solve all the problems of the world. Other times, they ignore or ridicule the importance of other human values, traditions, or institutions to long-term human flourishing and over value ease or efficiency.

When innovation advocates go overboard, they should be called out for it. But that doesn’t mean we should stop striving for a better future, and one in which technology is rightly viewed as the fundamental driver of human well-being. No matter what some critics say, technological solutions are people-based solutions. We craft tools to solve important problems and to better our lives and the lives of our loved ones. What could be more “humanist” than that?

Additional Reading:

Adam Thierer, “The Pacing Problem, the Collingridge Dilemma & Technological Determinism,” Technology Liberation Front, August 16, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “Defining ‘Technology’” Technology Liberation Front, originally published April 29, 2014, last updated July 2017.

“Evasive Entrepreneurs and Permissionless Innovation: An Interview with Adam Thierer,” The Bridge, September 11, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “Deep Technologies & Moonshots: Should We Dare to Dream?” Medium, September 7, 2018.

Adam Thierer, “Are “Permissionless Innovation” and “Responsible Innovation” Compatible?” July 12, 2017.

Adam Thierer, “What Does It Mean to “Have a Conversation” about a New Technology?,” Technology Liberation Front, May 23, 2013.

Adam Thierer, “On the Line between Technology Ethics vs. Technology Policy,” August 23, 2013.

September 13, 2018

Q&A about Evasive Entrepreneurialism & the Freedom to Innovate

Over at the Mercatus Center’s Bridge blog, Chad Reese interviewed me about my forthcoming book and continuing research on “evasive entrepreneurialism” and the freedom to innovate. I provide a quick summary of the issues and concepts that I am exploring with my colleagues currently. Those issues include:

free innovation

evasive entrepreneurialism & social entrepreneurialism

technological civil disobedience

the freedom to tinker / freedom to try / freedom to innovate

the right to earn a living

“moonshots” / deep technologies / disruptive innovation / transformative tech

innovation culture

global innovation arbitrage

the pacing problem & the Collingridge dilemma

“soft law” solutions for technological governance

You can read the entire Q&A over at The Bridge, or I have pasted it down below.

Your research and next book project are focused on “evasive entrepreneurialism” and the freedom to innovate. Tell us a bit more about this work.

Evasive entrepreneurs are innovators who don’t always conform to social or legal norms. Various scholars have documented how entrepreneurs are increasingly using new technological capabilities to circumvent traditional regulatory systems or put pressure on lawmakers or regulators to alter policy in some fashion. Evasive entrepreneurs rely on a strategy of “permissionless innovation” in both the business world and the political arena.

Some evasive behavior could even be considered “technological civil disobedience” in the sense that many innovators behave in this fashion because they find many rules to be offensive, confusing, time-consuming, expensive, or perhaps just annoying and irrelevant. In that sense, they could also be referred to as “regulatory entrepreneurs” who push back against what Tim Sandefur labels “The Permission Society.”

My book documents “evasive” behavior of this sort and explains why it is happening with increasing regularity. I also make the normative case for embracing the freedom to innovative more generally because of the many benefits society derives from technological innovations and especially “moonshots”—game-changing, transformative technologies.

You mentioned “permissionless innovation.” That was the topic of your last book. Could you explain what that means and how it relates to your new book?

The term “permissionless innovation” is of uncertain origin but generally refers to trying new things without asking for the prior blessing of various authorities. The phrase is sometimes attributed to Grace M. Hopper, a computer scientist who was a rear admiral in the United States Navy. “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission,” she once noted famously.

In my last book, I used the term more broadly to describe a governance philosophy for a variety of emerging technologies and contrasted it with its opposite—the “precautionary principle.” Permissionless innovation, I argued, refers to the notion that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted by default. Unless a compelling case can be made that a new invention will bring serious harm to society, innovation should be allowed to continue and problems, if any develop, can be addressed later.

By contrast, the precautionary principle generally recommends disallowing or slowing innovations until their creators can prove that new products and services are “safe,” however that is defined. The problem with making precaution the basis of all technology policy is that it means a great deal of life-enriching (and even life-saving) innovation will never come about if we base policy on hypothetical worst-case scenarios.

The tension between these visions is on display in every major technology field today—drones, driverless cars, crypocurrency, genetics, mobile medicine, 3D printing, virtual reality, the sharing economy, and many others. That’s why we have made these sectors the focus of ongoing Mercatus research.

Could you give us a few examples of how entrepreneurs behave in an “evasive” fashion or how innovators engage in technological civil disobedience?

Many scholars and tech analysts have highlighted the ways in which sharing economy innovators like Uber and Airbnb engaged in regulatory entrepreneurialism, but that’s hardly the only example. Using 3D printers and open source designs, for example, many creative people are pushing up against legal norms when they fabricate prosthetic hands for children with limb deficiencies or create their own firearms for self-defense.

One of my favorite examples is the open source, do-it-yourself Nightscout Project, a non-profit founded by parents of diabetic children. These parents came together and shared knowledge and code to create better insulin remote monitoring and delivery devices for their kids. Their motto is “WeAreNotWaiting.” Specifically, these parents got tired of waiting for the development of new “professional” devices to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which can take many years to get through the regulatory process. Through voluntary collaboration, these parents have created reliable devices that are much less expensive than those FDA-approved devices, which can cost many thousands of dollars.

When average citizens engage in this sort of “biohacking” to create better and cheaper insulin pumps or 3D-printed prosthetic limbs but do not charge anything for it, their actions are of ambiguous legality. But even if they are breaking some laws or bending some rules, it isn’t stopping them from working together to make the world a better place. That’s technological civil disobedience in a nutshell.

So evasive entrepreneurialism can be both commercial and non-commercial in character?

Yes. Abroad range of “evasive” actors exist with large commercial players on one end of the spectrum and purely non-commercial “grassroots” or “household” innovators on the other. MIT economist Eric von Hippel calls the latter activity “free innovation,” which includes things like the 3D-printed creations I already mentioned.

Social entrepreneurialism is a closely related concept. Several of my Mercatus colleagues have documented how social entrepreneurs were instrumental in helping community recovery efforts following hurricanes and other disasters. Entrepreneurs aim to create social value through innovative acts that can assist their communities, while also potentially helping them create new business opportunities later down the road.

What’s interesting about “free innovation” and social entrepreneurialism is that much of this activity happens at the boundaries of what it technically legal. These innovators just want to help others. When laws stand in the way of that, they sometimes creatively evade them to get things done. That’s clearly the case with the open source DIY insulin pumps or 3D-printed prosthetic limbs.

Another example involves drone enthusiasts who often help out in search-and-rescue missions for missing people and pets even though they could be running afoul of various aviation regulations in the process. Even something as routine as children setting up free lemonade stands without local permits serves as an example of how people can behave in an evasive fashion to serve others.

The so-called “pacing problem” figures prominently in your work. Could you explain what it is and why it is important to the future of innovation policy?

As I noted in a recent Bridge essay, the pacing problem refers to the notion that technological change increasingly outpaces the ability of laws and regulations to keep up. The power of “combinatorial innovation,” which is driven by “Moore’s Law,” fuels a constant expansion of technological capabilities. Meanwhile, citizens quickly assimilate new tools into their daily lives and then expect that even more and better tools will be delivered tomorrow.

This makes it difficult for government officials and organizations to keep policy in line with fast-moving marketplace and social developments. That is especially true because of how increasingly dysfunctional and unable to adapt many government bodies and processes have become. This is why I argue that the pacing problem is becoming the great equalizer in debates over technological governance; policymakers are being forced to rethink their approach to the regulation of many sectors and technologies. This is especially the case because the pacing problem can be exploited by evasive entrepreneurs who are looking to do an end-run around slower regulatory processes.

Will “evasive” tactics work for entrepreneurs in every context? It seems like this would be more challenging in some regulatory contexts than others, right?

Evasive techniques are obviously more likely to succeed for technologies and sectors that are “born free” as opposed to “born captive.” Technologies that are “born free” are not confronted with old laws and regulatory regimes that require permission before new products and services are offered. For example, there is no Federal Robotics Commission, 3D Printing Safety Act, or Virtual Reality Agency. It’s obviously easier to innovate as you wish in those fields, at least currently.

If, however, you want to put a driverless car on the road or a drone in the sky, preemptive approval is required, making evasive acts far riskier. Of course, it is exactly those sectors where evasive acts are potentially most needed! Too many old sectors are immune from new entry and consumer choice due to cronyism and industrial protectionism. As we saw with the ride-sharing services and now electric scooter sharing, sometimes evasive techniques can work for a time and then give innovators more leverage at the bargaining table.

In some cases, like space policy, supersonic transportation, or new FinTech offerings, evasive strategies are largely impossible because of the stifling morass of overlapping laws and regulations. Agencies will not tolerate much (if any) departure from regulatory norms in those instances. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and FDA are particularly notorious for stifling entrepreneurial efforts.

But I am sometimes surprised to find evasive efforts happening even in those sectors. While the FAA is quite heavy-handed about strictly regulating airspace, the agency isn’t doing much to enforce its current drone registration requirements. Countless Americans fly their drones every day without a care about what the feds say. And while 23andme got a cease-and-desist order from the FDA due to their evasive efforts with home genetic test kits, the creators of many mobile medical devices and 3D-printed medical objects are currently being allowed to push up against the boundaries of legality under traditional FDA rules. The agency has bent its rules to accommodate that activity. When agencies take a pass on enforcing their own regulations, that is called “rule departure,” and it seems to be happening with greater regularity, probably due to the combined influence of both the pacing problem and evasive entrepreneurialism.

What’s at stake if policymakers push back too aggressively against evasive innovators?

Technological innovation is the fundamental driver of human well-being. When we let people experiment with new and better ways of doing things, we not only allow for the constant expansion of new goods and services, but we grow opportunities, incomes, and knowledge. This is how countries raise their overall standard of living and achieve prosperity over the long haul.

Entrepreneurs are the key to this process because by taking risks and exploring new opportunities, they continuously replenish the well of important ideas and innovations. If, therefore, we punish creative people for seeking creative solutions to hard problems—even those sometimes behaving “evasively”—we will be denied the fruits of those creative efforts. We will also be denying them the right to earn a livingand enjoy the fruits of their labors. In this sense, the freedom to innovate is closely linked with individual autonomy and self-worth and deserves greater protection. It is about being free to pursue happiness however we each see fit.

Policymakers should, therefore, give innovators greater freedom to experiment, even when those efforts prove to be highly disruptive. Moonshots may not happen unless public policy supports a culture of experimentation and risk-taking. This is also crucial to the competitive advantage of nations. Scholars from many different fields have observed how a nation’s attitudes toward entrepreneurialism create a sort of “innovation culture,” which sends signals to individuals and investors about where they should spend their time and money. Unsurprisingly, where public policy frowns upon entrepreneurial effort, you get a lot less of it. Like a plant, innovation must be nurtured to help it and the economy grow.

In today’s highly integrated global economy, you either innovate or perish thanks to the increasing prevalence of “innovation arbitrage.” This refers to the fact that ideas and innovations will often flock to those jurisdictions that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity. We see it happening today with drones, driverless cars, and genetic testing to just name three prominent examples.

Don’t you think that policymakers will bring down the regulatory hammer on evasive entrepreneurs? Should they?

Humility, patience, and flexibility are the key virtues for policymakers in this regard. If policymakers can come to appreciate the ways in which evasive entrepreneurialism can help advance economic and social opportunities, then they should consider giving innovative acts a wide berth—even when entrepreneurs are not in strict compliance with all laws and regulations.

Evasive acts are not usually undertaken to completely defy the law. Instead, they often represent the beginning of a negotiation. Many innovators have grown frustrated with public policies that block new entry or just defy common sense. Evading anti-competitive or illogical restrictions is a way to gain some degree of leverage in political negotiations. Sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t. But traditional reform avenues are often foreclosed because incumbents and other defenders of the regulatory status quo don’t like change.

Policymakers should see evasive entrepreneurialism as a signal that politics sometimes fails to serve the public when change is needed most. And once they sit down with innovators to discuss a better way of crafting policy, they need to be willing to adapt and devise more flexible governance frameworks, most of a “soft law” variety. As my colleagues and I explain in a recent law review article, soft lawrefers to a hodge-podge of informal governance tools for emerging tech, such as multistakeholder processes, industry best practices, agency guidance and consultation, and so on. Such informal governance mechanisms will need to fill the governance gap left by the gradual erosion of hard law thanks to the growth of the pacing problem and the expansion of evasive entrepreneurialism.

But what about the worst-case scenarios some fear, like the proverbial mad scientist who concocts a horrific virus in their basement? Even if they are still just hypothetical, aren’t some serious risk worth addressing preemptively?

Indeed, there are some extremely serious harms that are worth addressing preemptively, but that’s all the better reason to not get obsessed with lesser concerns. Over-regulating entrepreneurial activity is foolish in a world where policymakers are both knowledge- and resource-constrained.

My Mercatus colleagues have documented the astonishing growth and cost of regulatory accumulation. But forget about the burden excessive regulation poses to entrepreneurs and the economy for a moment, and instead consider how all those enforcement activities divert the time and attention of regulators themselves away from bigger problems. When policymakers get lost in a convoluted compliance maze of their own making, they lose the ability to address big risks in a sensible, timely fashion. That’s why we need a new governance vision for the technological age that is more flexible and adaptive than the heavy-handed regulatory regimes of the Industrial Era.

Adam Thierer's Blog

- Adam Thierer's profile

- 1 follower